This chapter reviews the Commissioner’s proposals to introduce a lobbying framework in Malta. While the proposals are in line with international best practices, this chapter provides tailored recommendations to improve the proposed framework and close potential loopholes. It also proposes measures for strengthening integrity standards on lobbying and identifies avenues to establish sanctions for breaches of lobbying framework.

Public Integrity in Malta

5. Establishing a framework for transparency and integrity in lobbying and influence in Malta

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

Public policies determine to a large extent the prosperity and well-being of citizens and societies. They are also the main 'product' people receive, observe, and evaluate from their governments. While these policies should reflect the public interest, governments also need to acknowledge the existence of diverse interest groups, and consider the costs and benefits of the policies for these groups. In practice, a variety of private interests aim to influence public policies in their favour. This variety of interests allows policy makers to learn about options and trade-offs and ultimately decide on the best course of action on any given policy issue. Such an inclusive policy-making process leads to more informed and ultimately better policies.

In Malta, one of the primary avenues through which business associations, trade unions and civil society organisations provide input to draft laws and policy proposals is through the social dialogue mechanism. Input pertaining to domestic laws and policies can be made through the Council for Economic and Social Developments, which is an advisory body providing a forum for consultation and social dialogue between social partners and civil society organisations. The Council’s main task is to advise the government on issues relating to sustainable economic and social development in Malta, and its functions are regulated under the Malta Council for Economic and Social Development Act (No. 15 of 2001). Input related to laws and policies at the EU level is facilitated via European Service of Malta (Servizzi Ewropej f’Malta or SEM).

Social dialogue mechanisms play a critical role in the policy‑making process, and require an effective legislative framework, a commitment to implementation, and appropriate accountability measures to ensure governments comply with the principles of engaging stakeholders effectively. Stakeholders in Malta indicated that these mechanisms operate effectively, and enable interest groups to access government in a transparent manner.

However, social dialogue mechanisms are not the only way in which policies are influenced. While “professional” lobbying – that is, individuals whose formal occupation is to approach government on behalf of specific interests to influence a policy – is not a common occurrence in Malta, different interest groups have access to policy makers outside the social dialogue mechanisms that are currently unregulated and opaque. While the act of lobbying itself is beneficial for society as a whole, because it enables different groups to provide input and expertise to the policy‑making process, it has a profound impact on the outcome of public policies. If non-transparent, lobbying poses a risk to inclusiveness in decision making and trust in government, possibly resulting in the dissatisfaction of the public as a whole. Missing or ineffective lobbying regulation may also negatively affect the appetite of (foreign) investors and lower the country's trustworthiness at the international level.

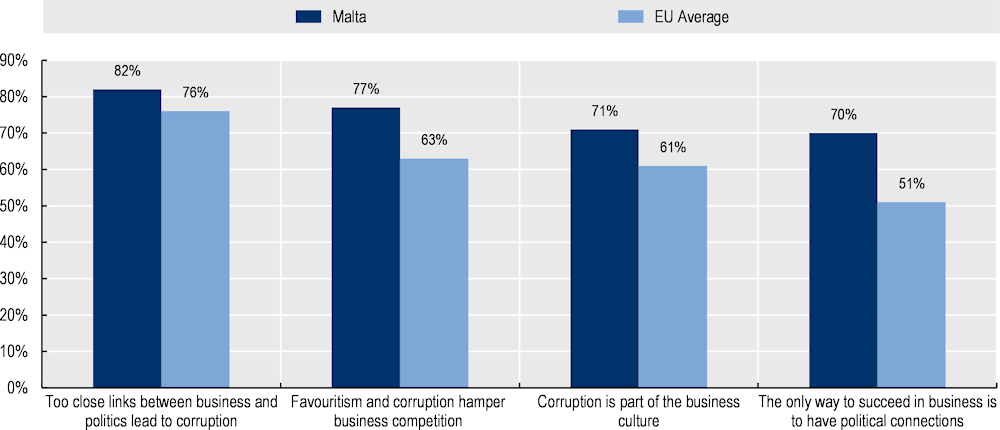

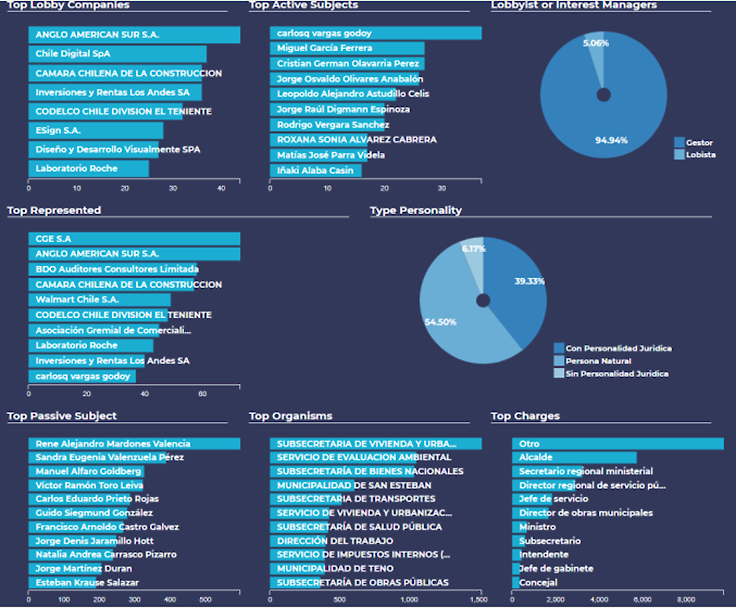

In Malta, non-transparent lobbying is a serious issue. Perception indices show that the perception of undue influence and an opaque relationship between the public and private sectors is significant in Malta. Recent Eurobarometer surveys found that 71% of respondents considered corruption to be a part of the business culture in government, with 70% responding that the only way to succeed in business was through political connections (see Figure 5.1) (European Commission, 2019[1]). In all these categories, Maltese respondents are above the EU average, showing that there are higher levels of perceived corruption when doing business in Malta.

Figure 5.1. Maltese perceive that close ties between business and politics lead to corruption

“Total Agree”

Similarly, in the most recent Corruption Barometer for the European Union, less than half (48%) of Maltese respondents think that the government takes their views into account when making decisions, and almost half (49%) think that the government is controlled by private interests.

Other institutions in Malta have highlighted the impact of non-transparent lobbying on policy making. For example, a 2018 report by the National Audit Office (NAO) found that undue influence was a factor in awarding high-value energy-supply contracts (National Audit Office, 2018[2]). In particular, the NAO found that a 2013 proposal for the construction of a new power station “raised serious concerns regarding the technical specifications for the construction of the power station set by Enemalta, which were influenced, if not dictated, by parties who had a direct interest in this contract” (National Audit Office, 2018[2]). The report further stated that the companies involved in putting forward the proposal were later awarded the contract (National Audit Office, 2018[2]).

Additionally, the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life has indicated several specific concerns related to lobbying in Malta. These include the concerns about the secrecy in which lobbying takes place – e.g. people do not know who is influencing a decision, and those who take a different view do not have the opportunity to rebut arguments and present alternative views; that some individuals and organisations have greater access to policy makers because of their contacts, because they are significant donors to a political party, or simply because they may have more resources; and that lobbying may be accompanied by entertainment or other inducements, or that there is lack of clarity about who is financing particular activities (Office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2020[3]).

Recognising the challenges to integrity in decision making posed by the lack of transparency in lobbying, the Government of Malta is taking steps towards introducing regulation. The Standards in Public Life Act empowers the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life “to identify activities that are to be considered as lobbying activities, to issue guidelines for those activities, and to make such recommendations as it deems appropriate in respect of the regulation of such activities”.

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life (“the Commissioner”) presented in February 2020 a document “Towards the Regulation of Lobbying in Malta: A Consultation Paper” (“Consultation Paper”). The Commissioner outlined a proposal for regulating lobbying activities in Malta, informed by international good practice. This proposal has been welcomed at the international level, including most recently in the compliance report by the Group of States against Corruption (GRECO).

This chapter reviews the Commissioner’s proposals to introduce a lobbying framework to Malta and provides recommendations to help the Government of Malta develop the most feasible lobbying regulation. The recommendations are tailored for the specific influence landscape in Malta and aim to improve the proposed framework and close potential loopholes.

5.2. Setting the legal and institutional framework for transparency and integrity in lobbying

When determining how to address governance concerns related to lobbying, countries need to weigh the available regulatory and policy options to select the appropriate solution. The specific context, constitutional principles, and established democratic practices (such as public hearings or institutionalised consultation practices) need to be factored in.

The OECD Recommendation on Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying (herein “OECD Lobbying Principles”) emphasise that Adherents should provide a level playing field by granting all stakeholders fair and equitable access to the development and implementation of public policies (Principle 1). Likewise, the OECD Lobbying Principles state that countries should consider the governance concerns related to lobbying practices (Principle 2), as well as how existing public governance frameworks can support this objective (Principle 3) (OECD, 2021[4]).

5.2.1. Establishing the legal framework

Currently in Malta, measures are in place to address some of the broader risks that could lead to undue influence, including conflict-of-interest and post-public employment. For example, the Standards in Public Life Act, which covers MPs, ministers, parliamentary secretaries and persons of trust, contains measures on conflicts of interest and acceptance of gifts and benefits in the Codes of Ethics for Members of the House of Representatives and Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, which are found in the first and second Schedule, respectively. Similarly, Article 4 of the Public Administration Act, which covers public officials, provides for rules on post-public employment, whereas the Code of Ethics contains measures on preventing and managing conflict of interest.

The broader legal framework, as noted above, also includes measures to facilitate public access to decision making. For example, rules pertaining to stakeholder engagement are set out in Malta Council for Economic and Social Development Act (No. 15 of 2001), and measures regulating access to information can be found in the Freedom of Information Act (Chapter 496 of the Laws of Malta).

Despite this existing framework, regulatory gaps remain when it comes to influencing policy makers. As noted above, there is a lack of transparency regarding which interest groups have access to which policy makers, and on what issues. Moreover, there is limited guidance for both public officials and those seeking to influence the policy‑making process on how to engage with one another in a way that upholds the public interest.

Recognising this challenge, the Standards in Public Life Act made provisions for further guidance to be issued to regulate lobbying. This entry point is set out in Article 13(1) of the Standards in Public Life Act, which empowers the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life to “issue guidelines” and “make such recommendations as he deems appropriate” with respect to the regulation of lobbying.

The Government of Malta could regulate lobbying through a dedicated law

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life has proposed to regulate lobbying through a dedicated law, rather than by issuing lobbying guidelines or amending the Standards in Public Life Act. Given the context in Malta, the proposal to regulate lobbying through a dedicated law has merit on several grounds.

First, the Standards in Public Life Act does not include any provisions that would make rules on lobbying included in it binding. Therefore, issuing guidance through the Standards Act would make the provisions voluntary, thereby undermining their effectiveness. Indeed, experience from OECD members has shown that voluntary methods are insufficient to deal with the challenges posed by lobbying (OECD, 2014[5]). For example, a select committee of the United Kingdom House of Commons produced a study in 2009 strongly recommending the adoption of a mandatory lobbying regulation. The report found that efforts at self-regulation fell short of expectations, and that a mandatory regulation was needed to achieve transparency on the extent to which interest groups are able to access and influence decision makers in Government (Box 5.1). The report later led to the adoption of a mandatory lobbying disclosure scheme in 2014.

Box 5.1. The United Kingdom: from self-regulation to mandatory regulation

In 2008 and 2009, a select committee of the United Kingdom House of Commons produced a study strongly recommending the adoption of a mandatory lobbying regulation. The report found that the conditions were not in place for effective self-regulation of lobbying activities by those who carry out these activities. At the time, many umbrella bodies, such as the Association of Professional Political Consultants (APPC), the Public Relations Consultants Association (PRCA) and the Chartered Institute of Public Relations (CIPR), had codes of conduct for their members and made several commitments to transparency of lobbying activities. These schemes however had inherent flaws:

First, there was no consistent approach across the sector. Umbrella organisations had diverse views on what constitutes appropriate conduct and some codes of conduct could be seen as the lowest common denominator. In addition, the codes and registration requirements only applied to those who were members of these umbrella organisations. Many law firms and think tanks who were heavily involved in influencing public policies did not participate in these association-run voluntary schemes. Lastly, the situation allowed consultancies to pick and choose the rules that applied to them. In sum, voluntary schemes applied unequally.

Second, the schemes did not provide an adequate level of transparency because a commitment to voluntary transparency in lobbying is always a relative concept. The report considered that how private interests achieve access and influence are among the trade secrets lobbyists are not willing to disclose voluntarily, and that a degree of external coercion was required to achieve sufficient transparency across the board.

Third, the complaints and disciplinary processes of the lobbying umbrella bodies were under-used and ineffective. Umbrella organisations had varying enforcement capacities, disciplinary process were scarcely ever used and reprimands were usually the only outcomes for disciplinary breaches.

Lastly, the three umbrella groups had an in-built conflict-of-interest, in that they attempted to act both as trade associations for the lobbyists themselves and as the regulators of their members’ behaviour.

Evidence has also shown that businesses may make high-profile voluntary commitments to address major global challenges such as environmental sustainability, and then contradict these commitments through their less-visible lobbying (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. Voluntary initiatives and self-regulatory pledges have shown limited impact in the climate policy area and may even be used to lobby against binding climate policy

Evidence shows that self-regulatory pledges and voluntary corporate programmes by companies may fall short of the impact they claim, and may even be used to mask lobbying efforts to block or delay binding climate policies (Lyon et al., 2018[7]). A study found that industry stakeholders in the United States primarily mobilised to maintain the status quo regarding cap and trade systems in 2009 and 2010, but simultaneously joined the cap and trade coalition in order to favourably shape potentially inevitable climate legislation (Grumbach, 2015[8]).

Another study showed that participants to the chemical industry’s “Responsible Care” programme actually made less progress in reducing their emissions of toxic chemicals than did nonparticipants (King and Lenox, 2000[9]). Chemical industry documents have shown that one of the programme’s main goals was pre-empting tighter regulations (Givel, 2007[10]). Lastly, an analysis of the Climate Challenge Program, a former partnership between business and the US Government to encourage electric utilities to voluntarily reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, found that there were no difference in emission reductions overall between participants and non-participants of the programme (Delmas and Montes-Sancho, 2009[11]). Similarly, public statements the electric utility industry made indicated that it formed Climate Challenge to avoid new regulations.

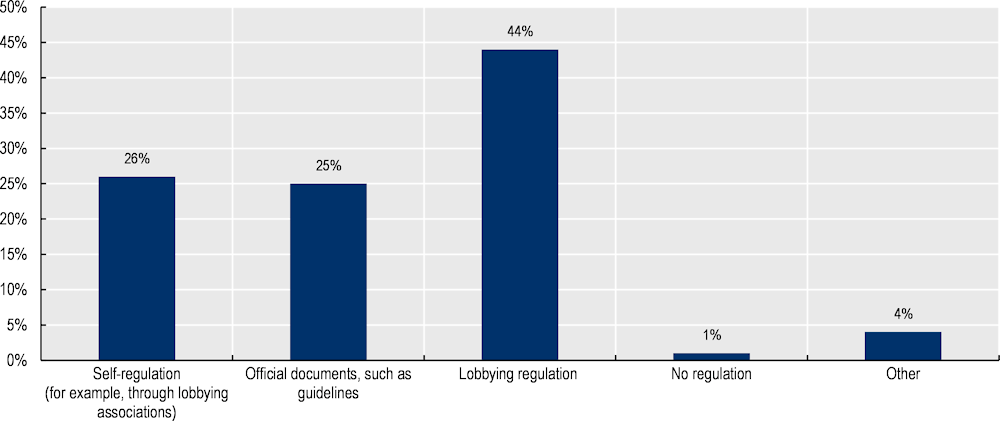

Lastly, surveys show that lobbyists themselves are generally supportive of mandatory regulations and public disclosure of lobbying activities. A recent OECD survey of professional lobbyists conducted in 2020 found that lobbyists favoured a mandatory lobbying regulation.

Figure 5.2. Best means for regulating lobbying activities, according to lobbyists

Source: OECD 2020 Survey on Lobbying.

Second, those who are lobbied are subject to various integrity standards and transparency requirements, but these regulations are insufficient in their coverage and do not have a specific focus on lobbying. For example, the scope of the current Standards in Public Life Act is limited to select officials, in particular those who are elected or appointed. While there is a case to be made for expanding the scope of the Act (see Chapter 2) the envisioned expansion would still miss key actors, including policy makers in the civil service. Good practice has found that making the provisions applicable across all branches of government is critical, as policy making takes place across a variety of public entities in all branches and levels of government. Moreover, as pointed out by the Commissioner, while the scope of the Act could be expanded through a sub-section to other entities, this would create legal confusion as well as potential gaps with other key legislation (e.g. the Act on Public Administration), in turn undermining implementation of and compliance with the law.

Finally, by setting out a separate law, the provisions of the law would be debated article by article in the House of Representatives. This would ensure that the Act itself, when passed, had undergone proper scrutiny and benefitted from public debate (Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2020[12]). However, in moving forward with the proposal to regulate lobbying through a separate law, the Commissioner could co-ordinate with the Ministry of Justice, in particular on the proposed reforms to the integrity provisions under the Public Administration Act. As indicated several times throughout the stakeholder interviews, the various regulatory instruments that govern integrity, including integrity in decision making, must be coherent and co‑ordinated to ensure there are no overlaps or gaps.

5.2.2. Assigning responsibilities for implementation

Setting clear and enforceable rules and guidelines for transparency and integrity in lobbying is necessary, but this alone is insufficient for success. Transparency and integrity requirements cannot achieve their objective unless the regulated actors comply with them and oversight entities effectively enforce them (OECD, 2021[4]).

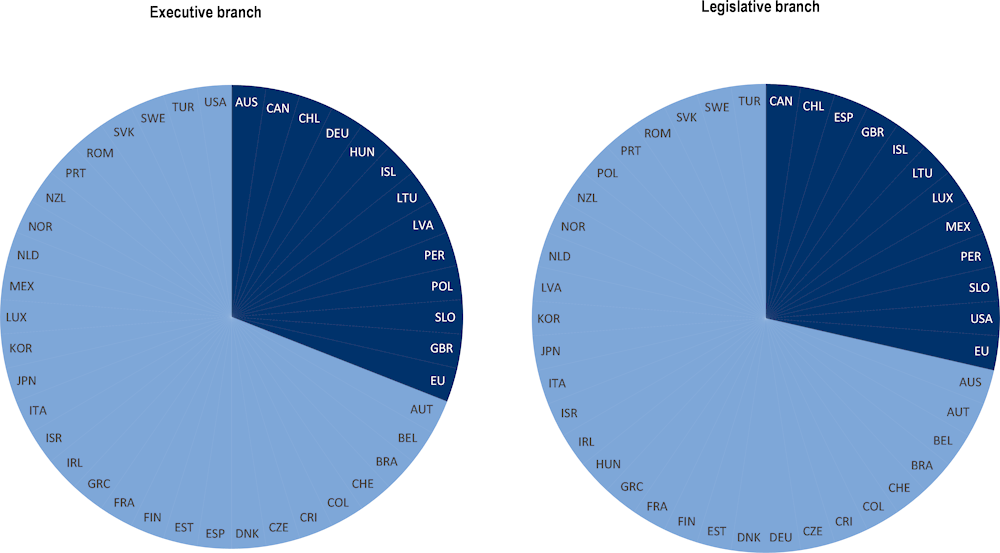

To that end, oversight mechanisms are an essential feature to ensure an effective lobbying regulation. All the countries that require transparency in lobbying activities have an oversight entity (OECD, 2021[4]). At the same time, all countries with a register on lobbying activities have an institution or function responsible for monitoring compliance. While the responsibilities of such bodies vary widely among OECD member and partner countries, three broad functions exist: 1) enforcement; 2) monitoring; and 3) promotion of the law.

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life could be entrusted with responsibilities for overseeing and enforcing the Regulation of Lobbying Act

The Commissioner has proposed that the operation of key aspects of the Regulation of Lobbying Act and its enforcement should be entrusted to the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. The Commissioner has also proposed that his office should host and maintain the register of lobbyists and enforce the requirement for lobbyists to register and submit regular returns, as well as enforce the requirement for designated public officials to list communications with lobbyists on relevant matters.

Some stakeholders noted reticence in assigning the Commissioner authority for overseeing the implementation of the Regulation of Lobbying Act. In particular, stakeholders noted that the Commissioner does not have the mandate to oversee conduct of public officials covered under the Act on Public Administration. To these stakeholders, the current set-up would limit the scope of the Regulation of Lobbying Act to only those falling under the Act on Standards in Public Life.

To address this limitation, the Commissioner has, as noted above, recommended to set out the rules on lobbying in a separate regulation in order to enable broader coverage and include those covered by the Standards in Public Life Act and the Public Administration Act. This legislative underpinning would therefore give the Commissioner the necessary authority. In addition, the Office’s existing institutional arrangements make it well-placed to administer the law: it enjoys functional independence and garners broad respect both from the government and society more broadly.

The proposal for the Commissioner’s office to be delegated responsibilities for enforcing and overseeing the lobbying regulation aligns with good practice from OECD members. It is not uncommon to assign the oversight body responsible for integrity standards of elected and appointed officials with responsibilities for policies pertaining to those in the civil service as well (such as lobbying). For example, in Ireland, the Standards in Public Office Commission oversees the administration of legislation in four distinct areas, including the Ethics in Public Office Act, which sets out standards for elected and appointed public officials, and the Regulation of Lobbying Act, which regulates lobbying for elected and appointed public officials, as well as officials in the civil service (see Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. The Irish Standards in Public Office Commission

The Irish Standards in Public Office Commission has supervisory roles under four Acts:

The Ethics in Public Office Act 1995, as amended by the Standards in Public Office Act 2001, (the Ethics Acts), which sets out standards for elected and appointed public officials. Under these Acts, the Commission processes complaints and examines possible wrongdoing, oversees tax compliance by people appointed to ‘senior office’ and candidates elected to Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann, amongst others.

The Electoral Act 1997, which regulates political financing, including political donations and election expenses. Under this Act, the Commission provides guidance and advice to stakeholders (e.g. on disclosure of political donations, limits on the value of donations which may be accepted, prohibited donations, limits on election spending), oversees compliance, amongst others.

The Oireachtas (Ministerial and Parliamentary Activities) (Amendment) Act 2014, which regulates expenditure of public funds to political parties and independents. Under this Act, the Commission reviews the disclosures by party leaders and Independents on how they spend their annual allowance, issues guidelines (e.g. on the parliamentary activities allowance and the Exchequer funding under the Electoral Acts), oversees the Act, amongst others.

The Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015, which makes transparent the lobbying of public officials. Under this Act, the Commission manages the register of lobbying, ensures compliance with the Act, provides guidance and assistance, and investigates and prosecutes offences under the Act.

In order for the Commissioner to effectively carry out an oversight and enforcement role of the lobbying regulation, it will require sufficient financial and human resources. Indeed, the Office of the Commissioner is currently small in number, with only 9 people assisting the Commissioner: six officers/employers and three people on a contract-for-service basis. Although having a small office has been a strength in terms of management, engagement and co‑ordination of the staff, it has also been a challenge in terms of ensuring that functions are fulfilled in a timely and efficient manner. In this sense, adding new functions on lobbying would substantially increase the workload of the Office, threatening further its capacity to deliver on its different responsibilities.

Considering this, if the Commissioner is assigned the mandate to oversee lobbying, it is fundamental to ensure that the Commissioner has the appropriate financial and human resources to carry out the new functions effectively. To that end, the Commissioner could undertake a workforce planning exercise, and request the House Business Committee of the House of Representatives for additional financial resources for the coming years (see the Organisational Review of the Office of the Commissioner for more details).

5.3. Ensuring transparency in lobbying

Transparency is the disclosure and subsequent accessibility of relevant government data and information (OECD, 2017[15]), and when applied to lobbying, is a tool that allows for public scrutiny of the public decision-making process (OECD, 2021[4]). Policies and measures on lobbying therefore should “provide an adequate degree of transparency to ensure that public officials, citizens and businesses can obtain sufficient information on lobbying activities” (OECD, 2010[16]). There are several ways in which transparency can be achieved: first, through clearly defining the terms ‘lobbying’ and ‘lobbyist’ (OECD, 2010[16]), and second, by implementing a “coherent spectrum of strategies and mechanisms” to ensure compliance with transparency measures (OECD, 2010[16]).

5.3.1. Clarifying definitions

In line with this good practice, the Commissioner has proposed clear definitions of “lobbying” and “lobbyist”. Moreover, the Commissioner has proposed that two key registers be set up: a Lobbying Register and a Transparency Register. The following reviews these proposals in turn and provides tailored recommendations to strengthen where necessary.

Clearly defining the terms ‘lobbying’ and ‘lobbyist’ is critical for ensuring effective lobbying regulation. While definitions should be tailored to the specific context, both 'lobbying' and 'lobbyists' should be defined robust, comprehensive and sufficiently explicit to avoid misinterpretation and to prevent loopholes (OECD, 2010[16]). Experience from other countries has found that providing effective definitions remains a challenge, in particular because those who seek to influence the policy-making process are not necessarily 'de facto' lobbyists. Indeed, avenues by which interest groups influence governments extend beyond the classical definition of lobbying and moreover, have evolved in recent years, not only in terms of the actors and practices involved but also in terms of the context in which they operate (OECD, 2021[4]).

To address this challenge, when setting up lobbying regulation, it is critical to ensure that the definition of lobbying activities is broadly considered, and focuses on inclusivity; in other words, aims to provide a level playing field for interest groups, whether business or not-for-profit entities, which aim to influence public decisions (OECD, 2010[16]). Box 5.4 provides an overview of OECD member experience in setting out clear, comprehensive and broad definitions on lobbying.

Box 5.4. Examples of broad definitions of ‘lobbying’ amongst OECD members

Australia

“Lobbying activities” means communications with a Government representative in an effort to influence Government decision making. “Communications with a Government representative” includes oral, written and electronic communications.

Belgium

Lobbying activities are activities carried out with the aim of directly or indirectly influencing the development or implementation of policies or the Chamber's decision-making processes.

Canada

Communications considered as lobbying include direct communications with a federal public office holder (i.e. either in writing or orally) and grass‑roots communications. The Lobbying Act defines grassroots communications as any appeals to members of the public through the mass media or by direct communication that seek to persuade those members of the public to communicate directly with a public office holder in an attempt to place pressure on the public office holder to endorse a particular opinion. For consultant lobbyists (lobbying on behalf of clients), arranging a meeting between a public office holder and any other person is considered as a lobbying activity.

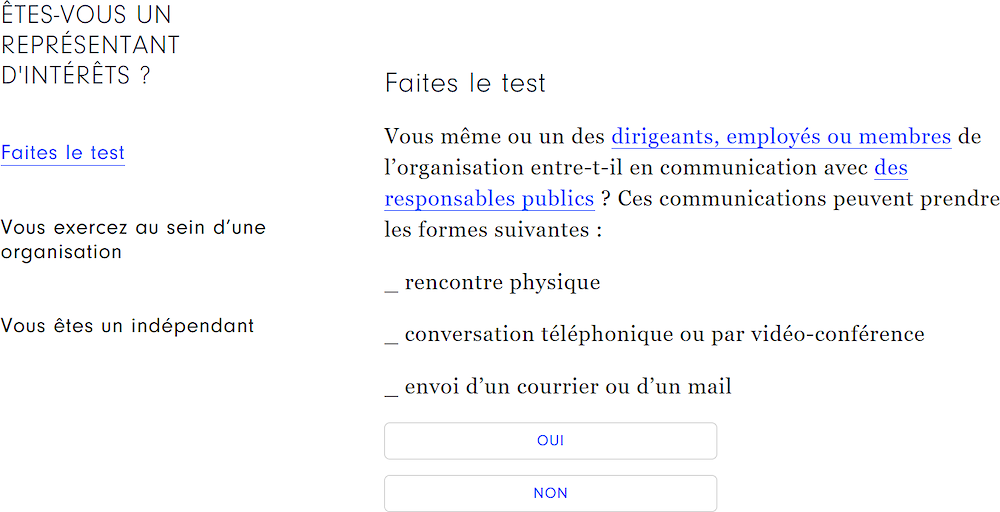

France

Three types of activities are considered as communications that may constitute lobbying activities: 1. A physical meeting, regardless of the context in which it takes place; 2. A telephone or video conference call; 3. Sending a letter, an email or a private message via an electronic communication service.

Ireland

Relevant communications means communications (whether oral or written and however made), other than excepted communications, made personally (directly or indirectly) to a designated public official in relation to a relevant matter.

European Union

Activities carried out with the objective of directly or indirectly influencing the formulation or implementation of policy and the decision-making processes of the EU institutions, irrespective of where they are undertaken and of the channel or medium of communication used, for example via outsourcing, media, contracts with professional intermediaries, think tanks, platforms, forums, campaigns and grassroots initiatives.

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

The current proposals set out by the Commissioner clearly and comprehensively defines the terms lobbying and lobbyist (see Table 5.1). These definitions are well adapted to the specific context in Malta. Broad in scope and covering a wide range of actors, the definitions make it possible to implement regulation on lobbying within a context where lobbying as a professional activity is not well-known, decision makers in government are easily accessible, and constituency politics are a key attribute of political life. Indeed, by separately defining “who” (i.e. “designated public officials” targeted by lobbying activities), “what” (i.e. what is “relevant matter”) and “how” (i.e. how the relevant matter turns into influencing – “relevant communication to a designated public official”), the definition enables any activity that fits both the “what” and “how” criteria to be subject to lobbying regulation.

Table 5.1. Proposed definitions on “lobbying” and “lobbyist” by the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life

|

Lobbying |

Any relevant communication on a relevant matter to a designated public official, with further delineation of the three core concepts as follows:

|

|

Lobbyist |

Any person (natural or legal) who makes a relevant communication on a relevant matter to a designated public official. |

The current definition of lobbyist, as defined by the Commissioner, is well-suited to the context in Malta. It enables coverage of a broad range of actors, including those that have not traditionally been viewed as “lobbyists” (e.g. think tanks, research institutions, foundations, non-governmental organisations, etc.).

However, while the proposed definitions regarding “lobbying” are broad in scope, several potential loopholes remain that could, if exploited, weaken the overarching legislation. The following addresses each of the potential loopholes in turn, and provides recommendations to strengthen them.

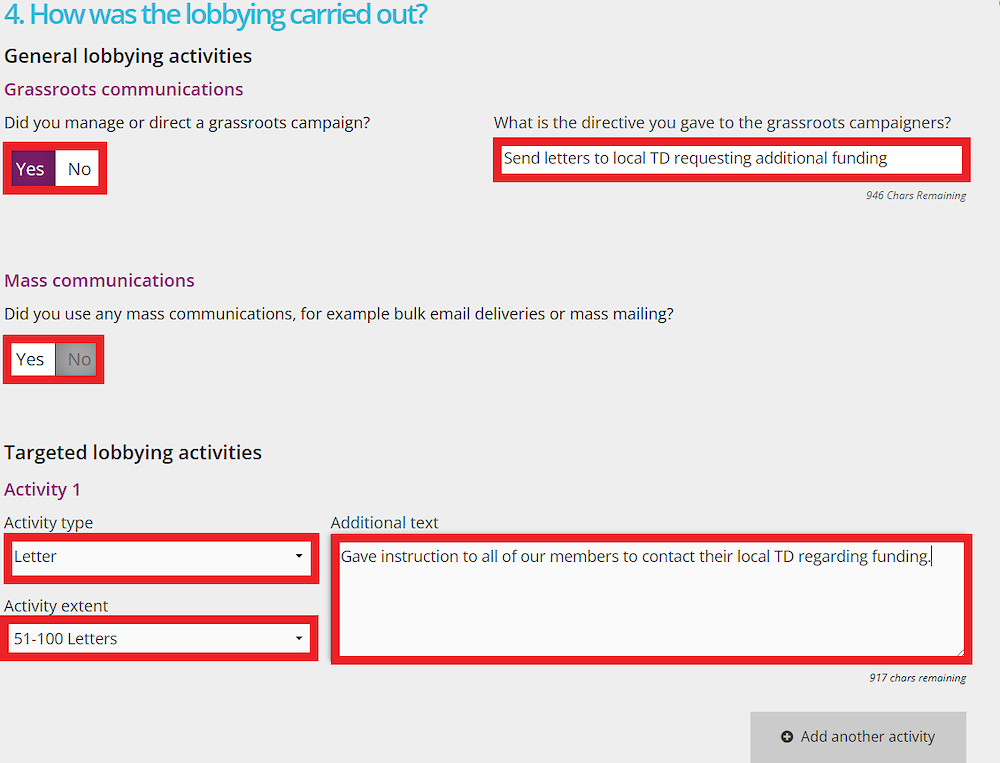

The Commissioner could strengthen the definition of “lobbying”

The advent of digital technologies and social media has made lobbying and influence more complex than the way it has been traditionally defined in regulations, usually as a direct oral or written communication with a public official to influence legislation, policy or administrative decisions. The avenues by which interest groups influence governments extend beyond this definition, however, and have evolved in recent years. With regards to the definition of relevant communications, the current proposal suggests that the communication may be either written or oral. This however leaves out other forms of communication, like sign language or the use of social media as a lobbying tool. The Commissioner could include in the definition of a relevant communication indirect forms of lobbying, going beyond direct written or oral communications. Within the OECD, Canada and the European Union cover such types of lobbying communications. In Canada, lobbyists are required to disclose any communication techniques used, which includes any appeals to members of the public through mass media, or by direct communication, aiming to persuade the public to communicate directly with public office holders, in order to pressure them to endorse a particular opinion. The Lobbying Act categorises this type of lobbying as “grassroots communication.” Similarly, the EU Transparency Register covers activities aimed at “indirectly influencing” EU institutions, including through the use of intermediate vectors such as media, public opinion, conferences or social events (Box 5.5). Moreover, the wording “is made personally (directly or indirectly) to a designated public official” may pose a loophole due to the term “personally”. In the age of the internet and social media, a lobbyist could deliver their message via, for example, targeted advertising. The wording may be simplified to “is made (directly or indirectly) to a designated public official”.

Box 5.5. Indirect forms of lobbying covered in Canada and the European Union

Canada

In Canada, paid lobbying through grass-roots communication can require registration under the Lobbying Act, even if there is no related direct lobbying. “Grass-roots communication”, also referred to as grass-roots lobbying, is defined in paragraph 5(2) (j) of the Lobbying Act as any appeals to members of the public through the mass media or by direct communication that seek to persuade those members of the public to communicate directly with a public office holder in an attempt to place pressure on the public office holder to endorse a particular opinion.

The Lobbying Commissioner considers that appeals to the public may include letters and electronic messaging campaigns, advertisements, websites, social media and platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Snapchat, YouTube, etc.

European Union

In the European Union, the Inter-institutional agreement between the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission on a mandatory transparency register defines “covered activities” as: (a) organising or participating in meetings, conferences or events, as well as engaging in any similar contacts with Union institutions; (b) contributing to or participating in consultations, hearings or other similar initiatives; (c) organising communication campaigns, platforms, networks and grassroots initiatives; (d) preparing or commissioning policy and position papers, amendments, opinion polls and surveys, open letters and other communication or information material, and commissioning and carrying out research.

Source: Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying Canada, Applicability of the Lobbying Act to Grass-roots Communications, Bulletin current to 2017-08-02 and last amended on 2017-08-02, https://lobbycanada.gc.ca/en/rules/the-lobbying-act/advice-and-interpretation-lobbying-act/applicability-of-the-lobbying-act-to-grass-roots-communications/; Transparency Register Guidelines, https://ec.europa.eu/transparencyregister/public/staticPage/displayStaticPage.do?locale=en&reference=GUIDELINES.

With regards to the definition of designated public officials, the proposed list aligns with good practice, however as the influence landscape has advanced, the range of those who can be on the receiving end of lobbying activities has also increased. To ensure that the definitions remain fit-for-purpose, the list of designated officials could build, to the maximum extent possible, on the lists laid out in Schedules of the Public Administration Act. In particular, it is recommended that all those from the “List of those posts within the public administration that, due to the nature of their role and responsibilities, are considered to be high-risk positions” (Sixth Schedule of the Public Administration Act) fall under the lobbying regulation. Moreover, it is recommended that in addition to state-owned companies, all companies funded by the state (even partially and in any form) be included. It is recommended that exceptions like state‑owned health insurance providers are not introduced in the lobbying regulation.

In order to promote transparency and accountability, it is recommended the list of “designated public officials” be publicly available and kept up-to-date. In Ireland, each public body must publish and keep up-to-date a list of designated public officials under the law; the Standards in Public Office Commission also publishes a list of public bodies with designated public officials (Box 5.6).

Box 5.6. Requirement to publish designated public officials’ details in Ireland

In Ireland, Section 6(4) of the Lobbying Act of 2015 requires each public body to publish a list showing the name, grade and brief details of the role and responsibilities of each “designated public official” of the body. The list must be kept up to date. The purpose of the list is twofold:

To allow members of the public to identify those persons who are designated public officials; and

As a resource for lobbyists filing a return to the Register who may need to source a designated public official’s details.

The list of designated public officials must be prominently displayed and easily found on the homepage of each organisation’s website. The page should also contain a link to the Register of Lobbying http://www.lobbying.ie.

Source: Standards in Public Office Commission, Requirements for public bodies, https://www.lobbying.ie/help-resources/information-for-public-bodies/requirements-for-public-bodies/.

With regards to the definition of relevant matter, the current scope covers communication that concerns (i) the initiation, development or modification of any public policy or of any public programme; (ii) the preparation or amendment of any law; or (iii) the award of any grant, loan or contract, or any licence or other authorisation involving public funds.

For the first category of activities, it is not clear whether the entire policy cycle is covered. In particular, three key phases (policy adoption, policy implementation, and policy evaluation) are not clearly identified. Within each of these stages, there are specific risks of influence, and a number of actors that could be targeted by those intending to sway decisions towards their private interests (see Table 5.2). While the intention could be that the existing term “modification” covers these three phases, the Commissioner could consider revising the definition to clarify these specific phases.

Table 5.2. Risks of undue influence along the policy cycle

|

Agenda-setting |

Policy development |

Policy adoption |

Policy implementation |

Policy evaluation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Risk of undue influence on |

Priorities |

Draft laws and regulations, policy documents (e.g. project feasibility studies, project specifications) |

Votes (laws) or administrative decisions (regulations), changes to draft laws or project specifications |

Implementation rules and procedures |

Evaluation results |

|

|

Main actors targeted |

Legislative level |

Legislators, ministerial staff, political parties |

Legislators, ministerial Staff, political parties |

Legislators, parliamentary commissions and committees, invited experts |

- |

Parliamentary commissions and committees, invited experts |

|

Administrative level |

Civil servants, technical experts, consultants |

Civil servants, technical experts, consultants |

Heads of administrative bodies or units |

Civil servants |

Civil servants, consultants (experts) |

|

Source: (OECD, 2017[17]).

The current proposals list a number of exemptions from what would be considered “relevant matters”. In general, an exemption from a definition should be only used in the last resort. Often, an alternative solution can be found for addressing the underlying concern. To that end, the Commissioner could consider revising the exemptions from relevant matters as follows:

Communications by an individual concerning his or her own private affairs: This exemption is in line with best practices in OECD countries, but could be further clarified to specify that it covers individual opinions expressed by a natural person on a relevant matter in a strictly personal capacity, but does not exempt activities of individuals associating with others to represent interests together (Box 5.7).

Box 5.7. Exemptions on communications by natural persons in OECD countries

European Union

In the European Union, the purpose of the Register is to show organised and/or collective interests, not personal interests of individuals acting in a strictly personal capacity and not in association with others. As such, activities carried out by natural persons acting in a strictly personal capacity and not in association with others, are not considered as lobbying activities. However, activities of individuals associating with others to represent interests together (e.g. through grassroots and other civil society movements engaging in covered activities) do qualify as interest representation activities and are covered by the Register.

Germany

In Germany, the Act Introducing a Lobbying Register for the Representation of Special Interests vis-à vis the German Bundestag and the Federal Government (Lobbying Register Act – Lobbyregistergesetz), excludes the activities of natural persons who, in their submissions, formulate exclusively personal interests, regardless of whether these coincide with business or other interests.

Ireland

In Ireland, the Regulation of Lobbying Act exempts “private affairs”, which refer to communications by or on behalf of an individual relating to his or her private affairs, unless they relate to the development or zoning of land. For example, communications in relation to a person’s eligibility for, or entitlement to, a social welfare payment, a local authority house, or a medical card are not relevant communications.

Lithuania

In Lithuania, Law No. VIII-1749 on Lobbying Activities exempts individual opinions expressed by a natural person with regards to legislation.

United States

In the United States, communications made on behalf of an individual with regard to that individual's benefits, employment, or other personal matters involving only that individual with respect to the formulation, modification, or adoption of private legislation for the relief of that individual are not considered as lobbying activities under the Lobbying Disclosure Act.

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

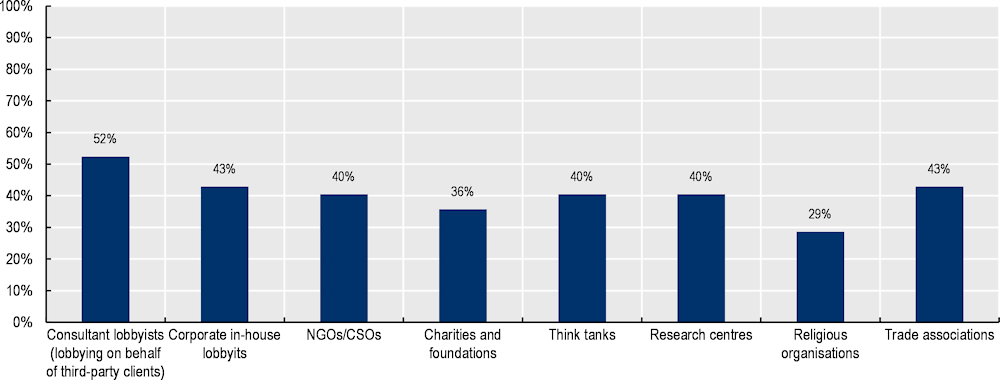

Communications by or on behalf of religious entities and organisations, and political parties: third-party communications on behalf of religious entities and organisations and political parties should not be exempt, and these subjects must communicate for themselves to have the communication automatically exempt from lobbying regulation. In 29% of OECD countries, religious organisations are bound by transparency requirements on their religious activities (Figure 5.3). Among the 22 countries that have lobbying transparency requirements, 12 consider the influence communications of religious organisations as lobbying activities, while 10 explicitly exempt them. In order to take into account the specific cultural and social context of Malta, a balance could be found by exempting religious denominations while including the activities of other religious organisations or groups representing religious interests in the scope of the law. In Canada for example, corporations without share capital incorporated to pursue, without financial gain to its members, objects of a religious character are considered as lobbying activities.

Figure 5.3. Percentage of countries covering different actors through their lobbying transparency requirements

Requests for factual information: exempting “requests for factual information” seems to be perfectly logical and innocent. However, it is not specified whether the exempted communications are requests for factual information by public officials or lobbyists. Such a blanket exemption may open the window for flooding a designated public official with “requests for factual information”, which may amount to massive lobbying campaigns. Based on the suggested exemption, such a campaign would remain undetected and unreported. The exemption could further be clarified in order to avoid any misinterpretations. First, the exception could cover communications by lobbyists made in response to a request from a public official concerning factual information or for the sole purpose of answering technical questions from a public office holder, and provided that the response does not otherwise seek to influence such a decision or cannot be considered as seeking to influence such a decision. In the United Kingdom for example, if a designated public official initiates communication with an organisation and in the subsequent course of the exchange, the criteria for lobbying are met, then the organisation is required to register the activity. It should also be clarified that such an exemption does not apply to appointed experts. The Commissioner had previously highlighted that “attention must be given to the possibility that persons will be engaged as consultants in order to avoid registration as lobbyists and the promotion of certain interests” and that “the consultative process with any such individuals should be adequately registered, minuted and reported”. As such, to address the mentioned concern, the exemption may include on appointed experts. Second, the law could further clarify which requests for information by lobbyists are covered by the exemption, for example when they consist of enquiring about the status of an administrative procedure, about the interpretation of a law, or that are intended to inform a client on a general legal situation or on his specific legal situation. Several examples are provided in Box 5.8.

Box 5.8. Exemptions on requests for factual information by lobbyists in OECD countries

In Belgium, activities relating to the provision of legal and other professional advice are not covered to the extent that they:

Consist of advisory activities and contacts with public authorities, intended to inform a client on a general legal situation or on his specific legal situation or to advise him/her on the opportunity or admissibility of a specific legal or administrative procedure in the existing legal and regulatory environment.

Are advice provided to a client to help ensure that its activities comply with applicable law.

Consist of analyses and studies prepared for clients on the potential impact of any changes in legislation or regulations with regard to their legal situation or field of activity.

Consist of representation in conciliation or mediation proceedings aimed at preventing a dispute from arising, brought before a judicial or administrative authority.

Affect the exercise of a client's fundamental right to a fair trial, including the right of defence in administrative proceedings, such as the activities carried out by lawyers or any other professionals concerned.

In Canada, the following activities are not considered as lobbying activities:

Any oral or written communication made to a public office holder by an individual on behalf of any person or organisation with respect to the enforcement, interpretation or application of any Act of Parliament or regulation by that public office holder with respect to that person or organisation; or

Any oral or written communication made to a public office holder by an individual on behalf of any person or organisation if the communication is restricted to a request for information.

In Chile, any request, verbal or written, made to enquire about the status of an administrative procedure is not considered as a lobbying activity.

In France, communications that are limited to factual exchanges that are not likely to have the purpose of influencing a public decision are not considered as lobbying activities:

When an organisation requests factual information, accessible to any person, to a public official.

When an organisation asks a public official how to interpret a public decision in force.

When an organisation sends information to a public official on its functioning or activities, without any direct connection with a public decision.

In Ireland, communications requesting factual information or providing factual information in response to a request for the information (for example, a company asking a public servant how to qualify for an enterprise grant and getting an answer) are not considered as lobbying activities.

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

Trade union negotiations: exempting trade union negotiations can be interpreted broadly and may include also, e.g. lobbying for the lowering of taxes for the employed – a matter where transparency is needed. It is recommended that only those trade union negotiations that directly relate to employment should be exempt from lobbying regulation. In the European Union for example, the activities of the social partners as participants in the social dialogue (trade unions, employers' associations, etc.) are not covered by the register where those social partners perform the role assigned to them in the Treaties. European social dialogue refers to the planned and/or institutionalised discussions, consultations, negotiations and joint actions involving social partners at EU level. However, employer or labour organisations that hold bilateral encounters with the EU institutions aimed at promoting their own interests or the interests of their members or carry out other activities not strictly related to European social dialogue, which are covered by the Register, do qualify as interest representatives and are eligible to (apply to) be entered in the Register. Similarly, in Ireland, communications forming part of, or directly related to, negotiations on terms and conditions of employment undertaken by representatives of a trade union on behalf of its members are not considered as lobbying activities.

Risky communication: while the reasoning behind exempting communications “which would pose a risk to the safety of any person” is sound, and a similar provision can be found in many lobbying regulations, such an exemption creates a potential loophole in the regulation. It is recommended that this exemption is omitted on the grounds that if a lobbyist feels a communication on a relevant matter towards a designated public official would pose any risk, he or she better not perform such communication.

Communications that are already in the public domain: the widespread use of the internet and the rise of social media, in particular, have blurred the line between what is and what is not in the public domain. Thus, exempting “communications that are already in the public domain” from a lobbying regulation seems to have the potential to create a loophole in the regulation. It is recommended to reconsider the need for such communication being exempt. If the need is confirmed, some other wording could be used to achieve the goal of excluding such communication. For example, the exemption could be limited to information provided to a Parliamentary committee and that are already in the public domain. In Canada, the Lobbying Act exempts “any oral or written submission made to a committee of the Senate or House of Commons or of both Houses of Parliament or to any body or person having jurisdiction or powers conferred by or under an Act of Parliament, in proceedings that are a matter of public record”.

Diplomatic relations (communications by or on behalf of other states and supranational organisations): while many countries also exempt these types of communications, it is recommended to limit this exemption to diplomatic activities. Foreign governments increasingly rely on lobbyists and other forms of influence to promote their policy objectives at national and multilateral levels. The risks involved in lobbying and influence activities of foreign interests are therefore high for all countries, and more transparency is needed on the influence of foreign governments. In Canada for example, consultant lobbyists representing the interests of foreign governments are bound by the same disclosure requirements as other actors specified in the Lobbying Act. Under the EU Inter-Institutional Agreement, activities by third countries are also covered, when they are carried out by entities without diplomatic status or through intermediaries.

The Commissioner could enhance the definition of relevant matters to include appointments of key government positions

A final area in which the definition of “relevant matters” could be strengthened refers to appointments of key government positions. Indeed, personnel decisions can be a key focus area for lobbyists, as it can be useful to further their policy agenda if a person responsive to their specific interests is placed in the relevant position. Thus, it would be beneficial to include personnel matters as a “relevant matter”. If left unregulated, it would pose a severe threat to any lobbying regulation. If lobbyists make it to have “their person” in the right position, they will roam free through decision-making processes, regulation or not. The risks associated with the possibility of forming a “lobbyist-official coalition” should not be underestimated when drafting a lobbying regulation. The design should be resilient: it should provide a basic level of protection of decision‑making from undue influence even under the scenario of such a coalition being in place.

In France and the United States, the appointment of certain public officials is also considered to be the kind of decision targeted by lobbying activities and thus covered by transparency requirements (Box 5.9).

Box 5.9. Individual appointment decisions are covered in France and the United States

France

The decisions targeted by lobbying activities were specified in Act No. 2016/1691 on transparency, the fight against corruption and the modernisation of the economy (Article 25). They include “individual appointment decisions”.

United States

The decisions targeted by lobbying activities are specified in the Lobbying Disclosure Act (Section 3 “Definitions”). They include nominations or confirmations of a person for a position subject to confirmation by the Senate.

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

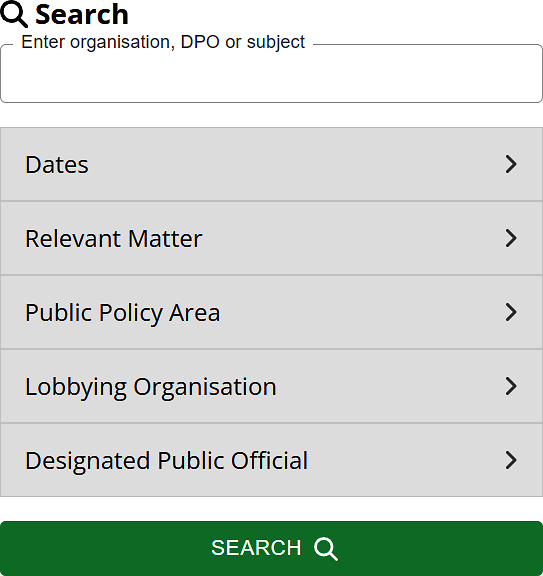

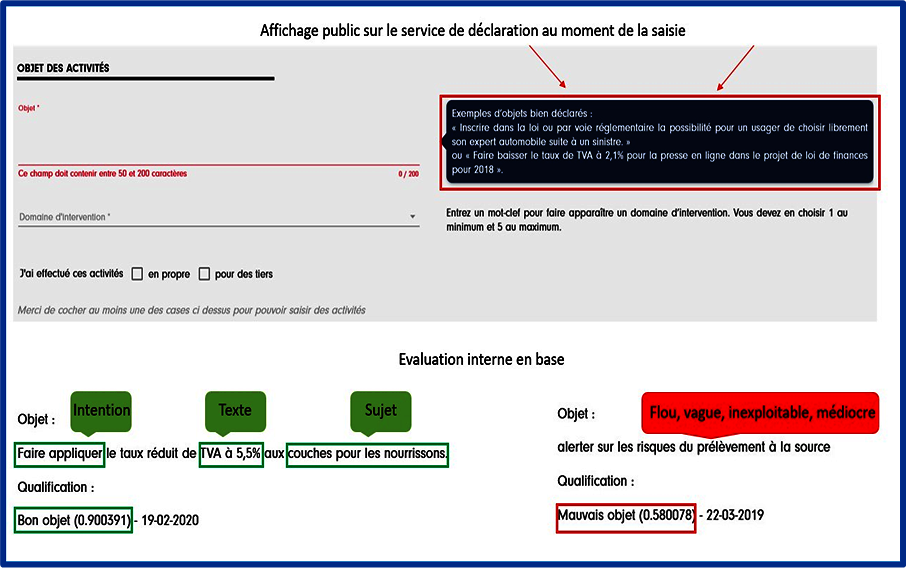

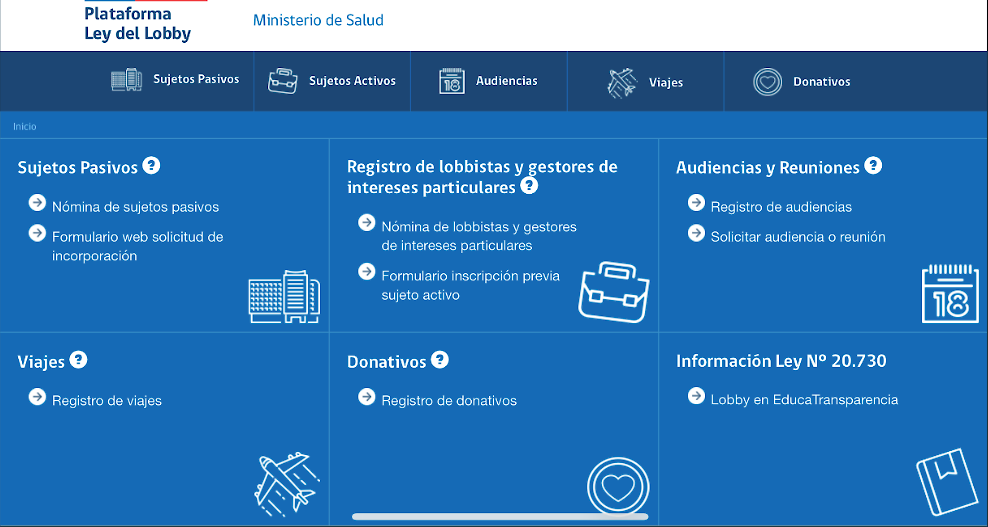

5.3.2. Establishing the Register for Lobbyists and the Transparency Register

A critical element for enhancing transparency and integrity in public decision making are mechanisms through which public officials, business and society can obtain sufficient information regarding who has access and on what issues (OECD, 2010[16]). Such mechanisms should ensure that sufficient, pertinent information on key aspects of lobbying activities is disclosed in a timely manner, with the ultimate aim of enabling public scrutiny (OECD, 2010[16]). In particular, disclosed information could include which policymakers, legislation, proposals, regulations or decisions were targeted by lobbyists. In establishing such mechanisms, countries should also ensure that legitimate exemptions, such as preserving confidential information in the public interest or protecting market-sensitive information, are carefully balanced with transparency needs (OECD, 2010[16]). Mechanisms can take the form of lobbying registers, open agendas, and/or legislative footprints.

The Regulation of Lobbying Act could include provisions that require regular, timely updates to the information contained in both the Register for Lobbyists and the Transparency Register

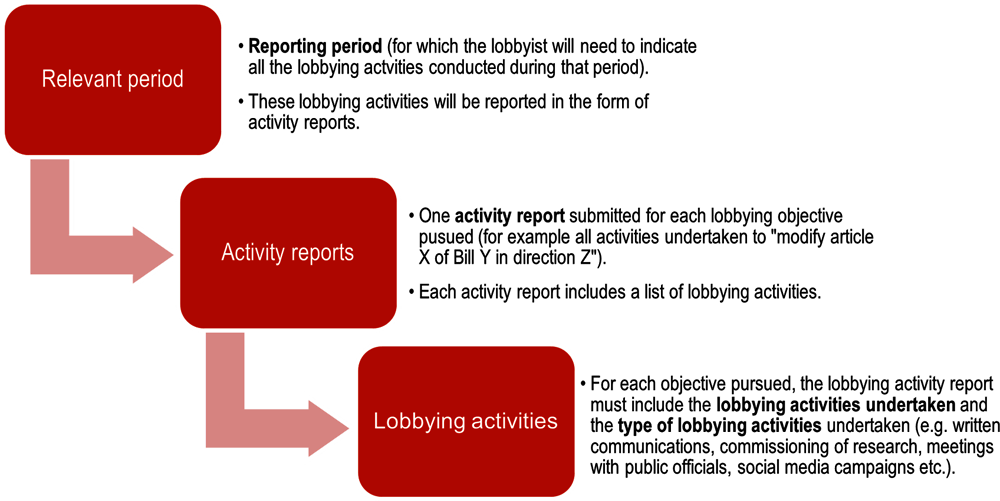

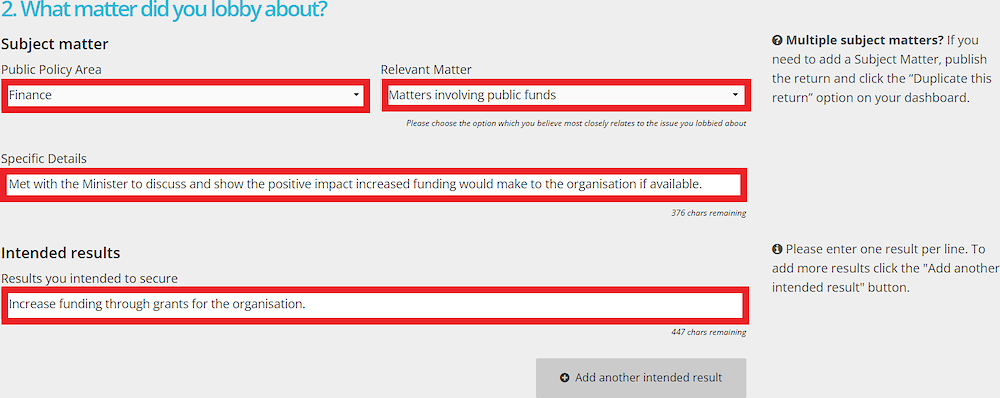

In Malta, the Commissioner has proposed two registries: the Register for Lobbyists and the Transparency Register. With regards to the Register for Lobbyists, the Commissioner proposes establishing an online, open register that is maintained by the Commissioner. Professional lobbyists, pressure groups (e.g. NGOs) and representative bodies (e.g. chambers and associations) will be required to register their name, contact details, business or main activities, and company registration number (where applicable). Registration will be a prerequisite for engaging in lobbying activities. Lobbyists will also be required to submit quarterly returns with information on respective lobbying activities (e.g. the clients on behalf of whom such activities were carried out; the designated public officials who were contacted; the subject matter of these communications; and the intended results).

The Register for Lobbyists meets two aims: (i) to formalise interactions between public officials and lobbyists; and (ii) to enable public scrutiny on who is accessing public officials, when and on what issues. Indeed, the information required in the returns does enable scrutiny, as information concerning what was influenced and the intended results is not only required, but also made public. To strengthen the Register for Lobbyists, the Commissioner could consider requiring that in-house lobbyists register, as they are currently overlooked in the proposals.

The current proposal suggests that lobbyists submit their returns on a quarterly basis. This aligns with good practice in several jurisdictions, including Ireland and the United States. Good practice from other countries has found that requiring more regular communication reports, such as on a monthly basis, can strengthen transparency (see for example the case of Canada in (Box 5.10) To that end, the Commissioner could consider requiring lobbyists to disclose on a quarterly or semestrial basis, as in Ireland or the United States (Table 5.3).

Box 5.10. Frequency of disclosures on lobbying activities in Canada

In Canada, lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. According to the Lobbying Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. 44 (4th Supp.)):

Consultant lobbyists must register within 10 days of entering an agreement to lobby.

In-house lobbyists must register when they meet a threshold (“significant part of duties”) and have 60 days to register.

Information must be updated every six months. Additionally, when registered lobbyists meet with a designated public office holder (i.e. senior federal officials), they must file a “monthly communication report”. The monthly communication report, filed no later than the 15th of the month after the communication took place, includes the names of those contacted, the date the communication took place, and the general subject matter of the communication (for example, “Health”, “Tourism”, etc.).

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

Table 5.3. Frequency of lobbying disclosures in the United States and Ireland

|

Initial registration |

Subsequent registrations |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Ireland |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Lobbyists can register after commencing lobbying, provided that they register and submit a return of lobbying activity within 21 days of the end of the first “relevant period” in which they begin lobbying (The relevant period is the four months ending on the last day of April, August and December each year). |

The 'returns' of lobbying activities are made at the end of each 'relevant period', every four months. They are published as soon as they are submitted. |

|

United States |

Lobbyists’ registration is mandatory to conduct lobbying activities. Registration is required within 45 days: (i) of the date lobbyist is employed or retained to make a lobbying contact on behalf of a client; (ii) of the date an in-house lobbyist makes a second lobbying contact. |

Lobbyists must file quarterly reports on lobbying activities and semi-annual reports on political contributions. |

Source: (OECD, 2021[4]).

The second transparency tool – the Transparency Register – complements the Register for Lobbyists and obliges ministers, parliamentary secretaries and others heads and deputy heads of their secretariats to list all relevant communications with lobbyists. The Transparency Register would also be freely accessible to the public, and would include details concerning (a) the name of the persons (natural and legal) with whom each relevant communication was held; (b) the subject matter of the communication; (c) in the case of a meeting, the date and location, the names of those present, and who they were representing; and (d) any decisions taken or commitments made through the communication.

This type of register is often referred to as an open agenda, as it contains a comprehensive public record of influence targeting specific public officials. By providing an additional avenue for transparency, the Transparency Register also addresses the inherent weakness of the Register of Lobbyists. Indeed, regardless of the requirements set out to register and submit information in a timely manner, some actors will avoid identifying and reporting their actions as “lobbying”. Thus, it is crucial that the lobbying regulation contains a separate mechanism for reporting all influence efforts, regardless of the lobbyist/non-lobbyist status of the influencer. To ensure that the Transparency Register enables the necessary public scrutiny, the Commissioner could require that the Transparency Register be regularly updated, either in real-time or on a weekly basis. Furthermore, as noted below, the proposed obligation to record all relevant communications with lobbyists in the Transparency Register could be expanded to Members of the House of Representatives.

As complying with reporting requirements can prove challenging, some countries use communication tools to remind lobbyists and public officials about mandatory reporting obligations. For example, in the United States, the Office of the Clerk of the House of Representatives provides an electronic notification service for all registered lobbyists (OECD, 2021[4]). The service gives email notice of future filing deadlines or relevant information on disclosure filing procedures. The Lobbying Disclosure website of the House of Representatives also displays reminders on filing deadlines. In Ireland, registered lobbyists receive automatic email alerts at the end of each relevant period, as well as deadline reminder emails. Return deadlines are also displayed on the main webpage of the Register of Lobbying (OECD, 2021[4]). This practice could be considered in the future to facilitate reporting.

It is also recommended that an effective enforcement mechanism be put in place to ensure compliance with this requirement (see section on sanctions below).

The Regulation on Lobbying Act could include provisions requiring the Commissioner to prepare a regulatory and legislative footprint for specific decision-making processes

The OECD Lobbying Principles states that governments should also consider facilitating public scrutiny by indicating who has sought to influence legislative or policy-making processes, for example by disclosing a legislative footprint that indicates the lobbyists consulted in the development of legislative initiatives (OECD, 2010[16]). Indeed, in addition to lobbying registers and open agendas, several countries provide transparency on lobbying activities based on ex post disclosure of information on how decisions were made (see Box 5.11).

Box 5.11. Thematic analyses on lobbying published by the High Authority for transparency in public life in France

In 2020, the High Authority for the Transparency of Public Life implemented a new platform on lobbying. This platform contains practical factsheets, answers to frequently asked questions, statistics as well as thematic analyses based on data from the register.

For example, the High Authority has published two reports on declared lobbying activities on specific bills, which shed light on the practical reality of lobbying.

Source: HATVP, https://www.hatvp.fr/lobbying.

The Regulation on Lobbying Act could include a provision assigning responsibility to the Commissioner for compiling and disclosing a legislative and regulatory footprint on specific decision-making processes, including for example legislation, government policies or programmes, and high-risk or high-dollar value contracts or concessions. In determining what “relevant matters” should be accompanied by a legislative footprint, the Commissioner could consider a risk-based approach. The information disclosed can be in the form of a table or a document listing the identity of the stakeholders contacted, the public officials involved, the purpose and outcome of their meetings, and an assessment of how the inputs received from external stakeholders was taken into account in the final decision. Keeping the Transparency Register up-to-date before a decision-making process enters the next phase or is closed will be instrumental in helping achieve this legislative footprint. Ideally, no decision-making process should be closed before the public have had a reasonable amount of time to review the relevant information in the Transparency Register. For example, before a ministerial bill is submitted for governmental approval or before an Environmental Impact Statement is released for public comment within an EIA procedure.

The Regulation of Lobbying Act could include provisions that further clarify the administration and accessibility of the Register for Lobbyists and the Transparency Register

A key challenge in implementing transparency registers is ensuring that the collected information can be published in an open, re-usable format. This facilitates the reusability and cross-checking of data (OECD, 2021[4]). While it is too early in the process to comment on the actual modalities of the proposed registries, the Commissioner could consider making recommendations that the eventual law on lobbying clarify that the Commissioner will manage the registries, that the data will be accessible and free of charge, and that information will be published in open data format. Box 5.12 contains excerpts from various lobbying laws regarding these parameters.

Box 5.12. Ensuring open, accessible lobbying registries

Canada

Article 9 of the Lobbying Act:

(1) The Commissioner shall establish and maintain a registry in which shall be kept a record of all returns and other documents submitted to the Commissioner under this Act (…).

(2) The registry shall be organized in such manner and kept in such form as the Commissioner may determine.

(4) The registry shall be open to public inspection at such place and at such reasonable hours as the Commissioner may determine.

France

Law on transparency in public life (Article 18-1):

« Un répertoire numérique assure l'information des citoyens sur les relations entre les représentants d'intérêts et les pouvoirs publics. Ce répertoire est rendu public par la Haute Autorité pour la transparence de la vie publique. Cette publication s'effectue dans un format ouvert librement utilisable et exploitable par un système de traitement automatisé, dans les conditions prévues au titre II du livre III du code des relations entre le public et l'administration »

“A digital directory provides information to citizens on the relations between interest representatives and public authorities. This directory shall be made public by the High Authority for the transparency of public life. This publication is made in an open format that can be freely used and processed by an automated processing system, under the conditions set out in Title II of Book III of the Code on relations between the public and the administration.”

Ireland

Regulation of Lobbying Act of 2015:

9. The Commission shall establish and maintain a register to be known as the Register of Lobbying (referred to in this Act as the “Register”).

10.

(1) The Register shall contain—

(a) the information contained in applications made to the Commission under section 11, and

(b) the information contained in returns made to the Commission under section 12.

(2) The Register shall be kept in such form as the Commission considers appropriate.

(3) The Register shall be made available for inspection free of charge on a website maintained or used by the Commission.

Source: Additional research by the OECD Secretariat.

Regarding the operation of the registries, the current proposal is for the Regulation of the Lobbying Act to oblige ministers, parliamentary secretaries, and the heads and deputy heads of their secretariats to establish a Transparency Register in which they should list relevant information (Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2020[12]). However, this “distributed” form of the Transparency Register – e.g. every institution having its own register – would undermine interoperability and reliability, on top of being more costly. Instead, the Commissioner could be assigned responsibility in the Act on Lobbying for administering both the Register of Lobbyists as well as the Transparency Register.

The Regulation of Lobbying Act could contain clear criteria for withholding data contained in the Register for Lobbyists and Transparency Register

The current proposals enable the Commissioner the power to withhold from the public any information contained in the Register of Lobbyists and Transparency Register, if the Commissioner considers that it is necessary to do so to prevent it from being misused, or to protect the safety of any individual or the security of the State.

The term “personal data”, seems to be unnecessarily limiting, especially for protecting safety: non‑personal data may also put someone in danger, e.g. by providing clues for revealing their identity. It is therefore recommended to omit “personal” and use “data related to a person’s identity”. Further, it is recommended that the State's interests, not only the security of the State as is currently proposed, be considered, as this concept is broader and gives the Commissioner higher level of flexibility to prevent any sensitive data from being disclosed.

Moreover, the power to withhold any information from the Register for Lobbyists and the Transparency Register must rest solely with the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life. While lobbyists should comply with the required criteria for submitting information, there may be situations in which it is prudent to keep certain information confidential. To ensure transparency, the Regulation of Lobbying Act could provide clear criteria to guide the Commissioner’s determination for when to withhold certain information and on what grounds.

The Regulation of Lobbying Act could include: (i) binding rules for the selection process of advisory or expert groups, and (ii) transparency into what the outcomes are, how they have been dealt with and how they are incorporated in the resulting decision

Chairpersons and members of advisory or expert groups (including government boards and committees) play a critical role in government decision making as they can help strengthen evidence-based decision making. However, without sufficient transparency and safeguards against conflict of interest, these groups pose a possible avenue for exerting undue influence in the decision-making process by allowing individual representatives participating in these groups to favour private interests (e.g. by serving biased evidence to the decision makers on behalf of companies or industries or by allowing corporate executives or lobbyists to advise governments as members of an advisory group). Still, transparency over the composition and functioning of advisory and expert groups remains limited across OECD countries (OECD, 2021[4]).

In Malta, there are currently more than 170 government boards and 90 committees (Government of Malta, n.d.[18]), which provide advice and guidance on policies, plans and practices within and across sectors, having a key impact on laws, policies and government performance. Yet, there is no general rule on the establishment and functioning of government boards and committees, meaning that there is no general provision indicating the common purpose of such boards and committees, their functioning and optimal composition (e.g. who can be appointed as member of a government board and committee, appropriate qualification and conditions for appointment).

To that end, the Office of the Prime Minister could introduce general rules for the selection process of government boards and committees to ensure a balanced representation of interests in advisory groups (e.g. in terms of private sector and civil society representatives (when relevant) and/or in terms of backgrounds), guarantee that the selection process is inclusive, -so that every potential expert has a real chance to participate‑, and transparent -so that the public can effectively scrutinise the selection of members of advisory groups-. Moreover, to allow for public scrutiny, information on the structure, mandate, composition and criteria for selection for all Maltese government boards and committees should be made public. In addition, and provided that confidential information is protected and without delaying the work of these groups, the agendas, records of decisions and evidence gathered could also be published in order to enhance transparency and encourage better public scrutiny.

Along with the composition of advisory or expert groups, the problem of the opacity of their outcomes could be addressed in the Regulation of Lobbying Act. To that end, it is recommended that these outcomes be made public via the Transparency Register (for more on the Transparency Register, see relevant section “Enhancing the transparency of influence on public decision-making”).

Moreover, considering that members of advisory groups come from different backgrounds and may have different interests, it is fundamental to provide a common framework that allows all members to carry out their duties in the general interest. Indeed, in Malta, members of government boards and committees come from the public, private and voluntary sectors. Currently, the Code of Ethics for Public Employees and Board Members, as laid down in the first schedule of the Public Administration Act, provides some general integrity standards for chairpersons and members of standing boards and commissions within the public administration. However, such provisions could be strengthened with specific standards on how to handle conflicts of interest and interactions with third parties.

To that end, the Office of the Commissioner could consider strengthening the rules of procedures for government boards and committees, including terms of appointment, standards of conduct, and procedures for preventing and managing conflicts of interest, amongst others. The Transparency Code for working groups in Ireland may serve as an example for the Office of the Commissioner (Box 5.13).

Box 5.13. Transparency Code for working groups in Ireland

In Ireland, any working group set up by a minister or public service body that includes at least one designated public official and at least one person from outside the public service, and which reviews, assesses or analyses any issue of public policy with a view to reporting on it to the Minister of the Government or the public service body, must comply with a Transparency Code.

The Code prescribes various transparency measures: important information about the body's composition and functioning must be available online, including the body's meeting minutes.

Importantly, if the requirements of the Code are not adhered to, interactions within the group are considered to be a lobbying activity under the lobbying act.

Source: Department of Public Expenditure and Reform, Transparency Code prepared in accordance with Section 5 (7) of the Regulation of Lobbying Act 2015, https://www.lobbying.ie/media/5986/2015-08-06-transparency-code-eng.pdf.

5.4. Fostering integrity in lobbying

Apart from enhancing the transparency of the policy-making process, the strength and effectiveness of the process also rests on the integrity of both public officials and those who try to influence them (OECD, 2021[4]). Indeed, governments should foster a culture of integrity in public organisations and decision making by providing clear rules, principles and guidelines of conduct for public officials, while lobbyists should comply with standards of professionalism and transparency as they share responsibility for fostering a culture of transparency and integrity in lobbying (OECD, 2021[4]).

The 2021 OECD Report on Lobbying found that although all countries have established legislation, policies and guidelines on public integrity, they have usually not been tailored to the specific risks of lobbying and other influence practices. Additionally, considering that lobbyists and companies are under increasing scrutiny, they need a clearer integrity framework for engaging with the policy-making process in a way that does not raise concerns over integrity and inclusiveness (OECD, 2021[4]).

5.4.1. Strengthening integrity standards on lobbying

In Malta, there are different general guidelines on public integrity for public officials, which include some specific provisions aiming at strengthening the resilience of decision-making processes to undue influence. Such guidelines are i) the Code of Ethics for Public Employees and Board Members, ii) the Code of Ethics for Members of the House of Representatives and iii) the Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries.