This chapter provides recommendations for improving the collection and verification of asset and interest declarations for Members of the House of Representatives, Ministers, and Parliamentary Secretaries in Malta. In particular, this chapter identifies strategies to strengthen the current system, including by expanding the scope of officials covered by the requirements and the items to be disclosed. This chapter also proposes measures to streamline the submission process, for example through an electronic system and adoption of a risk-based methodology for the review of submissions.

Public Integrity in Malta

4. Improving the collection and verification of asset and interest declarations for elected and appointed officials in Malta

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

Asset and interest declarations are used globally to identify unjustified variations in the assets of public officials, prevent conflicts of interest, improve integrity, and promote accountability. Many countries have introduced systems of asset declarations for public officials to prevent corruption (OECD, 2011[1]).

Financial disclosures of assets or interests play an important role in national anti-corruption systems. Asset declarations cover the disclosure of pecuniary interests, they are usually verified with specific and pre-determined frequency, as their role is mainly to reveal inconsistencies and significant variances when comparing declarations for successive years. Asset declarations are not intended as a preventive tool, but rather as a post factum verification of unjustified wealth and illicit enrichment. Interest disclosures on the other hand may include both pecuniary and non-pecuniary interests, and are used to report, manage, and therefore prevent a conflict of interest from arising. By indicating whether the public official has an economic interest that may influence the decision making process, a conflict-of-interest system may help prevent unlawful situations from arising in the first place. Interest declarations may be reviewed in an ad hoc manner, when the conflict or interest arises, providing flexibility as a preventive tool.

Asset declarations are a useful tool to enhance transparency, and accountability and fight against corruption. In particular, managing and analysing asset declarations’ data enables investigators and law enforcement agencies to detect and prove irregularities. By enabling transparency regarding public officials’ assets, declarations can also serve as a deterrent. In some countries the idea is accepted that declarations of public officials should serve as a special tool of wealth monitoring. The rationale is that public officials should be subject to stronger scrutiny than the rest of the population (OECD, 2011[1]).

According to World Bank research, more than 160 countries have introduced a system of asset, interest disclosure, or both, for public officials (World Bank, 2021[2]). Yet, many of them struggle to make use of its full potential. Cumbersome filing procedures, gaps in disclosure forms, and lack of enforcement limit their role. Similarly, ineffective verification of declarations undermines their utility as an anti-corruption tool. When seeking to strengthen their integrity and anti-corruption systems, countries should have a clear vision of why they are introducing these reporting obligations, what goals they are pursuing in this process, and what outcomes they expect to achieve (World Bank/UNODC, 2023[3]).

This chapter provides recommendations to improve the collection and verification of assets and interest declarations for Malta’s elected and appointed officials, including Members of the House of Representatives (MPs), Ministers, and Parliamentary Secretaries, as set forth under the Standards in Public Life Act in its First and Second schedules (Parliament of Malta, 2018[4]). These recommendations focus on broadening the scope of asset declarations, streamlining their submission process, setting in place a risk-based review process, and strengthening the sanctions for non-compliance.

4.2. Towards an effective system of asset and interest declarations for elected officials in Malta

4.2.1. Institutional and legal framework of asset and interest declarations in Malta

Several types of regulations can provide the legal basis for public officials’ declarations. Usually, asset declarations are regulated by a special law or section setting out the purpose, scope and design of the system. These will vary depending on whether declarations are a major part of an overarching anti-corruption legislation, or just one of many procedures in the legal framework. The type of legal basis is also likely to depend on whether declarations are viewed as a general tool for promoting public accountability among the political class or as a more comprehensive anti-corruption tool for the state as a whole (OECD, 2011[1]).

In Malta, Article 5(1) of the First Schedule of the Standards in Public Life Act (Code of Ethics of Members of the House of Representatives) calls for every member of the House of Representatives to annually indicate in a register, kept by the Speaker and opened to inspection by the public, the following information (Parliament of Malta, 2018[4]):

The MPs’ work or professions, and if employed, the identity of their employers.

Own immovable property, that of spouses if the community of assets applies, that of minor children as well as, if the MP so wishes, the manner of its acquisition and of its use.

Shares in commercial companies, investments including money deposited in banks and any other form of pecuniary interest.

Directorships or other official positions in commercial companies, associations, boards, co-operatives, or other groups, even if voluntary associations.

Moreover, Article 5(2)(a) of the First Schedule requires MPs who have a professional interest with persons, groups or companies which themselves have a direct interest in legislation before the House, to declare their interests, at the first opportunity, before a vote is taken on the Second Reading of a Bill. Annual declarations by MPs are filled by hand and submitted to the Speaker of the House by 30 April of each year.

Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries must comply with the standards set forth in the Second Schedule of the Standards in Public Life Act (Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries) (Parliament of Malta, 2018[4]). Article 7(3) requires them to annually submit a declaration of assets and interests to the Cabinet Secretary, including any interest that may give rise to a perception of conflict of interest or an actual conflict of interest (“Register of Interests”). To support implementation of this requirement, the Manual of Cabinet Procedures provides a declaration form, which can be filled by hand, containing the items to be declared, including:

Real estate/immovable property belonging to the Minister or over which the Minister holds any title (including any held by the spouse if it forms part of a community of assets, and minor children).

Shares, bonds, other participations in commercial companies or partnerships, whether public or private (including from spouse if it forms part of a community of assets, and minor children).

Total amount of deposits in banks and any other financial interests (including from spouse if it forms part of a community of assets, and underage children).

Positions as directors and other positions in commercial companies, associations, boards, public and private co-ops.

Income for the reference year.

Total amount of outstanding loans.

The Manual provides for the form to be submitted by Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to the Secretary of the Cabinet Office within 2 months of their appointment and no later than 31 March of each year thereafter. The form does contain some additional indications on the way it should be filled in.

Additionally, each year asset declarations by Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries are tabled in the House of Representatives, as a result of which they become freely downloadable. The declarations kept by the Cabinet Secretary are, in principle, public. The Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries (Article 8.1) also requires Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to ensure that “there is no conflict between their public duties and private interests, financial or otherwise” (Government of Malta, 2018[5]), and to immediately inform the Prime Minister if there is a change in their personal circumstances which may give rise to a conflict.

MPs who act as Ministers or Parliamentary Secretaries are subject to dual requirements and expected to declare their assets and interests both as members of the House of Representatives – as provided by the Code of Ethics for Members of the House of Representatives – and as Ministers – as provided by the Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries.

Discussions with key stakeholders as well as other reports by international bodies have pointed to several shortcoming in the legal framework for asset declarations. Although both codes of ethics require MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to complete and submit their asset declarations on a regular basis, the current provisions included in such codes are narrow in scope and pose limitations.

For instance, the categories of persons whose data is to be disclosed is not broad enough, and the scope of the information reported is limited. Certain intangible assets such as patents, brand, trademark, or copyrights, as well as outside sources and amounts of income, are not included. Overall, the asset and interest declaration system focuses on financial assets, which is key for detecting unjustified wealth and illicit enrichment but limits reporting, managing and preventing conflict-of-interest situations. Assessed against international good practice (Box 4.1), Malta could consider implementing several measures to improve its current system, including broadening the scope of officials covered by the requirements, the items to be disclosed and the way the information is collected and reviewed.

Box 4.1. Recommendations on the disclosure and registration of assets and interests provided in the Technical Guide to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC)

Disclosure covers all substantial types of incomes and assets of officials (all or from a certain level of appointment or sector and/or their relatives).

Disclosure forms allow for year-on-year comparisons of officials’ financial position.

Disclosure procedures preclude possibilities to conceal officials’ assets through other means or, to the extent possible, assets held by those against whom a state party may have no access (e.g. held overseas or by a non-resident).

A reliable system for income and asset control exists for all physical and legal persons – such as within tax administration – to access in relation to persons or legal entities associated with public officials.

Officials have a strong duty to substantiate/prove the sources of their income.

To the extent possible, officials are precluded from declaring non-existent assets, which can later be used as justification for otherwise unexplained wealth

Oversight agencies have sufficient manpower, expertise, technical capacity and legal authority for meaningful controls.

Appropriate deterrent penalties exist for violations of these requirements.

Source: (UNODC, 2009[6])

4.2.2. Broadening the scope of asset declarations

The Ministry of Justice could consider amending the Codes of Ethics for members of the House of Representatives, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to expand the type of information to be declared and the existing categories of declarants

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life (hereafter “the Commissioner”) has made proposals to improve the asset declaration regime, including through amendments to the Codes of Ethics for Members of the House of Representatives and for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries and the “Register of Interests”. These proposals include additional guidelines that go into more detail and present both the type of financial and non-financial interests that should be registered and the different moments in which interests should be registered:

New MPs would be required to register all their current financial interests with the Commissioner within 28 days of taking their Oath of Allegiance.

MPs would be required to record their financial and non-financial interests in the Register of Interests, by 31st March of every calendar year. Information shall be recorded as of 31st December of the previous year and cover the following: (a) work or profession, and if they are employed, the identity of their employer; (b) immovable property; (c) shares in companies/business interests; (d) quoted investments, government stocks, treasury bills, deposit certificates and bank balances; (e) bank or other debt; and (f) directorships or other official positions in commercial companies, associations, boards, co-operatives or other groups, even if voluntary associations.

MPs would be required to register in the Register of Interests within 28 days, any change in the registrable interests (b), (c) and (f) of the previous paragraph (OECD, 2022[7]).

However, these proposed amendments could be further strengthened to provide for an increasingly robust asset declarations’ system, in particular by expanding the range of officials subject to reporting obligations and the type of information that elected and appointed officials are required to disclose.

Categories of declarants

In Malta, persons of trust, one of the categories of public officials covered by the Standards Act, are not required to disclose their assets and/or interests. This is problematic as a high number of public officials are appointed via the “persons of trust” mechanism. Furthermore, some occupy central roles in decision making and further transparency mechanisms would strengthen public trust in their functions (see Chapter 2). Other international organisations (IO) have been of the view that Malta could apply current regulations to a broader number of categories of such persons (GRECO, 2018[8]). Malta could consider broadening the category of declarants, by including persons of trust as a category of declarants, when their role involves management or administration of public funds or decision-making.

Similarly, under current regulations the situation of the spouse and other family members is captured within a very limited scope, for the declarations of both MPs and Ministries. In particular, information concerning a spouse’s assets is only included if the property is part of a community of assets. In case of another matrimonial property regimes, the level of transparency decreases (GRECO, 2018[8]). Mechanisms to track the financial assets and interests of not only public officials but also their close relatives and household members can help prevent concealment of assets under the names of family members, spouses or other individuals (OECD, 2011[1]). The primary rationale of this requirement is to manage potential conflicts of interest by providing more transparency on the individuals vis-à-vis whom the official may have interests. For example, in Lithuania, officials are required to identify any “close persons or other persons he/she knows who may be the cause of a conflict of interest” in the opinion of the person concerned.

The Ministry of Justice could consider including and expanding the categories of public officials who submit an asset declaration in the proposed amendments to the Code of Ethics for Members of the House of Representatives, and in the proposed Code of Ethics for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to include the mentioned categories. The inclusion of persons of trust could be made by amending the Public Administration Act or by including an ad hoc clause in the Standards in Public Life Act. The Ministry of Justice could also consider proposing an enhanced due diligence for related persons, for example, when notice of a possible violation is received or a probe is initiated. During the consultations on the asset and interest declarations system, authorities in Malta were of the view that, in any case, all efforts should be made to ensure that any improvements to the system do not translate in a dissuasive barrier, perceived or otherwise, to serve in public life. For example, in Slovenia, if the comparison of the data submitted with the actual situation provides reasonable grounds for an assumption that an official is transferring property or income to family members for the purpose of evading supervision, the Commission of the National Assembly may, at the proposal of the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption, also request the official to submit data for his/her family members (OECD, 2011[1]).

Scope and categories of assets to be declared

The categories of assets, amount of information and level of detail that an official may be required to disclose, vary from country to country depending on the objectives of the disclosure system and the laws, regulations, and administrative guidelines governing the conduct of public officials. However, most declaration forms require a combination of the following information: movable and non-movable assets, liabilities, financial and business interests, positions outside of office, and information on the sources and values of income.

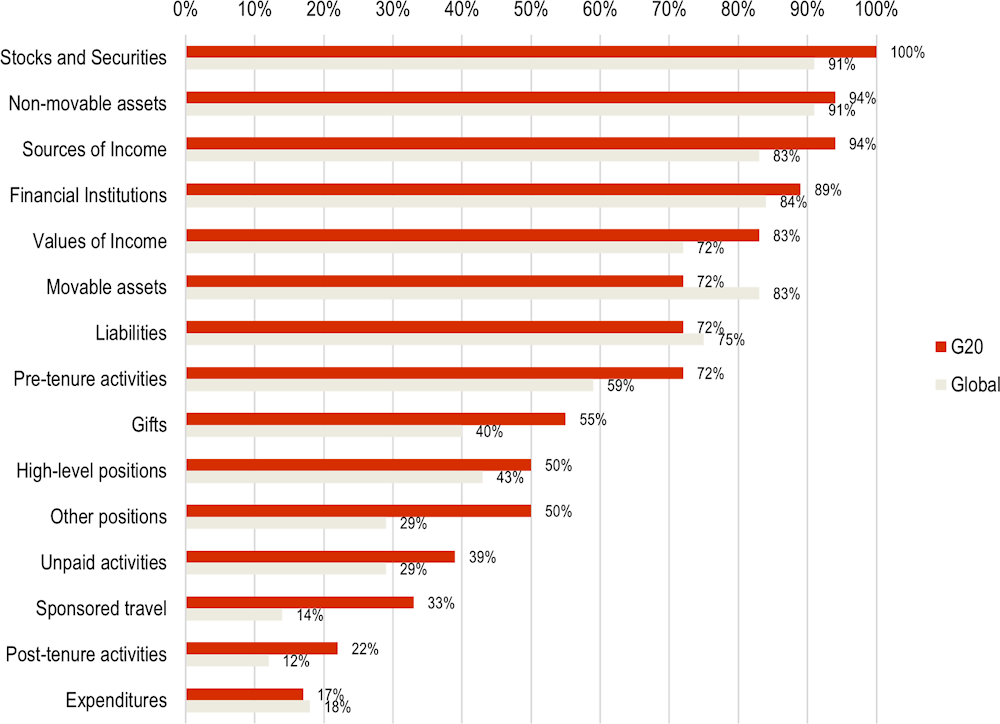

G20 countries follow the global trend of having greater coverage of financial aspects such as non-movable assets rather than outside activities or business relationships that may create conflicts of interest (Figure 4.1) (OECD/World Bank, 2014[9]).

Figure 4.1. Categories of information covered in disclosure requirements

Notes: World Bank analysis of 138 countries with disclosures systems. For G20, percentages are calculated only considering those countries that have a disclosure system.

Source: (OECD/World Bank, 2014[9])

In Malta, even though declarations for both MPs as well as Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries cover a reasonably broad range of assets and interests, discussions with key stakeholders underscored that further details could be included to strengthen the usefulness of the declarations. The category in the declaration form referring to “any other types of financial interests” would in principle cover all sorts of assets and movable property of a certain value (cash held in a safety deposit box or outside a financial institution, precious metals and stones, an art collection etc). However, according to several stakeholders, the current template falls short of allowing a proper analysis of unjustified assets, laundering of criminal proceeds and violations of conflict-of-interest rules. As real control of assets regardless of the nominal owner, and the use of assets, may show hidden ownership or lifestyle not commensurate with the official’s position or income, disclosure of beneficial ownership of assets should therefore extend to all types of tangible or intangible property and income (World Bank, 2021[2]).

Considering some of these limitations, a new asset declaration template was put in place in 2019 by the Commissioner to provide a better understanding of MPs’ source of wealth and source of funds. The template requested information on:

Details of income.

Immovable property.

Purchases of movable property exceeding EUR 5 000 during the year of reference.

Investments, bank deposits, debt.

Gifts and benefits received during the year of reference.

For each of these categories, MPs were required to list information pertaining both to them and to their spouse or partner.

However, there was limited uptake of the new template by appointed and elected officials, in part because it expanded the reporting requirements prescribed by the legal framework. Therefore, the Ministry of Justice could consider amending the Codes of Ethics for members of the House of Representatives, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries to formally expand the scope of information to be reported in asset declarations in Malta, and possibly include:

Income as a category in MPs declarations, as is the case for Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries.

Luxury and tangible assets (e.g. movable assets such as antiques, luxury cars, etc.) considered valuable assets. These are regularly used to hide profits from money laundering or corruption.

Clear dates, for example on when a property was bought, as this would help in contrasting information on a later stage and understanding patrimonial increases over time.

Disclosure of all types of income as well as gifts and sponsored travel, including disclosure of the identification details of the legal entity or individual who was the source of the income, gift, or sponsored travel.

Use of virtual assets (e.g. cryptocurrencies). The reporting of such assets in the form is an important step towards bringing transparency to this new mode of wealth accumulation.

Disclosure of national and foreign bank accounts and safe deposits boxes (vaults) to which the declarant or family members have access, even if formally opened by another person.

Blind trusts, as these are often channels used to evade tax as well as launder proceeds of corruption.

Loans given or received, including to/from private individuals.

Deferred corporate rights (e.g. options to purchase shares) and investments regardless of their form.

Disclosure of expenditure above a certain threshold. This is essential to track significant changes in wealth by comparing income, savings and expenditures over time. Expenditures should cover not only acquisition of assets but also payment for services and works.

Disclosure of expenditure above a certain threshold (it should consider individual or aggregate expenditures that surpass the determined threshold). This is essential to track significant changes in wealth by comparing income, savings and expenditures over time. Expenditures should cover not only acquisition of assets but also payment for services and works.

Disclosure of interests not related to income or assets, notably contracts with state entities of the declarant and family members or companies in their control, prior employment, and any link with legal entities and associations (e.g. membership in governing bodies). (World Bank, 2021[2])

To ensure compliance, Malta could consider introducing new asset declaration requirements through explicit legal provisions within the relevant Codes. Legislation could also consider empowering the Commissioner to amend the template as necessary, including new categories that may potentially help it fulfil his role in the review of declarations.

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life could develop tailored guidance to support Ministers, Parliamentary Secretaries and Members of the House of Representatives in completing the interest declaration forms

Asset declarations do not only depend solely on the legal obligation to report, but also the quality of the information provided by public officials. Therefore, ensuring forms are understood and filled in correctly, and having access to guidance when needed, is a key part of the success of any system. Indeed, the act itself of completing a declaration can strengthen the integrity of public officials as they need to first self-evaluate which assets they have, and the extent to which these could lead to a potential conflict of interest or undermine their ability to serve the public interest. Through access to impartial guidance, officials also benefit from opportunities to discuss potential doubts and dilemmas concerning their assets and interests. This can have the dual benefit of preventing potential conflict-of-interest situations before they arise, as well as strengthening the awareness and capacity of officials to apply integrity standards in their day-to-day activities.

Discussions with MPs underscored the need of standardised rules and guidance on completing their asset declarations. In particular, stakeholders noted that many of the criteria included in the current forms were unclear, which made it difficult to complete the form to a satisfactory standard. For example, in many cases, categories of the current form are not clear, including the level of detail required by these provisions. Similarly, stakeholders were of the view that more needs to be done to increase awareness amongst declarants of the importance of asset declarations and the proper reporting of this information. A compilation of asset declarations submitted by MPs and Ministers in 2022 provides a clear overview of the challenges with some declarants providing very detailed information, whereas others were scarcer or simply reproduced information from previous years (Government of Malta, 2022[10]). An example of this difficulty has been evidenced by the Commissioner who has reported that incidents of incorrect declarations are a consequence of this, rather than the hiding of income.

Similarly, consultations demonstrated the need of improving the resources available to MPs for the fulfilling of their functions. As things stand, MPs in Malta serve on a part-time basis, with no support or assistance. All MPs, both backbenchers on the Government side and Opposition MPs, should be given proper research and communications assistance for the proper fulfilling of their role. MPs interviewed for this report were of the view that in any case, Malta could start discussions to consider MPs fulfil their role on a full-time basis with a salary commensurate with the level of responsibility that comes with their Constitutional and legislative role.

The Commissioner has taken several steps to address this situation, including providing MPs who were making incorrect declarations an opportunity to amend the information. However, given that most of these declarations were not scrutinised before and given that there was no misrepresentation and no hidden income, the Commissioner did not consider it necessary to open any formal investigations emerging from the verification of declarations. Advice is given on a case-by-case basis, but no additional training or systematisation of these experiences for future reference is done by the Commissioner.

In other countries. much of this information has been systematised and clear channels established for consultation (Box 4.2). The Commissioner could consider preparing guidelines on completing asset declarations for MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, including a syllabus with lessons learned from previous cases on incorrect declarations. This guidance could also include a range of examples on financial and economic interests, debts and assets. More focused examples of unacceptable conduct and relationships could be provided for those groups that have a secondary employment, such as the public/private sector interface (OECD, 2003[11]). Furthermore, the Commissioner could consider creating institutionalised channels of communication with MPs to provide advice as may be necessary. This could be done, for example, when MPs and Ministers are first appointed and a few weeks before filing their declarations.

Box 4.2. Guidance on Asset and Interest Declarations in Brazil, Canada and the United States

Countries may provide support mechanisms to asset declarations filers through for example websites, media, designated staff, telephone-hotlines, detailed guidelines and frequently asked questions attached to blank forms.

In Brazil, the Comptroller General Office manages the disclosure system for federal public officials and its website provides information on who, what, when and how to disclose as well as the legal framework on the disclosure process. The Brazilian tax authorities also publish guidelines and information online for public officials completing the declarations. For the Chamber of Deputies, there are three websites that provide guidance: the first covers who, when and how to declare; the second provides a list of documents deputies must complete before assuming public office; and the third is a guidance note on how to fill in the tax form used as the financial disclosure.

In Canada, the Office of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner advises MPs and public office holders on conflict of interest and disclosures. The Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner also works with sub-national governments on training and filing declarations.

In the United States, the Office of Government Ethics carries out a range of activities, from providing second level reviews of the disclosures, to educating and training ethics officials and public officials.

Source: (OECD/World Bank, 2014[9])

Malta could consider separating its “asset” and “interest” declarations, to allow better comprehension amongst elected officials of the purpose of each

Disclosure forms help create and maintain a sound integrity system. However, the content of these declarations as well as their objective can vary. Therefore, it is important to have clarity with respect to the objectives, the information requested and its subsequent use. When filling out a form as part of a conflict-of-interest management regime, an official must take stock of his or her interests and the interests of his or her family members, evaluate these interests in light of the duties performed and decide whether any additional steps need to be taken to manage any conflicts of interest. This initial self-identification and evaluation process can and should generate requests for assistance to those who provide advice and guidance on managing conflicts of interest and help supplement the advice and guidance provided based simply on a subsequent official review (OECD, 2005[12]). On the other hand, financial disclosures are a tool used to identify illicit enrichment by contrasting financial information and would rarely be used to prevent a conflict of interest in a decision-making process.

Similarly, “interests” may come into conflict in an “ad-hoc” manner, whereas assets change less often. Furthermore, separating declarations may keep the focus of the asset declaration on illicit wealth monitoring, while simultaneously building a better understanding amongst elected officials about the “natural” occurrence of conflicts of interest. Even while asset declarations can serve to identify some potential conflicts of interest, they cannot replace the management of conflicts of interest, which needs to be done differently.

Malta has chosen a single declaration for the reporting of both assets and interests of elected officials. This is done by way of a single unified and centralised form. However, the information is being used for the sole purpose of identifying mistakes in asset reporting rather than a system that allows identifying relevant interests, contrasting these against votes in parliamentary debates or to establish a preventive and management system that provides advice on the management of these interests. Furthermore, reporting ad-hoc interests is not a possibility within the current system and the management of conflicts of interest is solely focused on recusals when taking a vote.

Malta could consider the use of a single declaration vis a vis separating into a system of multiple declarations. The experience of OECD countries such as Portugal and Lithuania, who use separate declaration forms or separate procedures for submission and processing, may provide relevant examples. Similarly, consideration could be given to running a single declaration for all categories of elected and appointed officials, with some differences, for example, for information requested for the first time and the information that is requested to be submitted annually (Box 4.3).

In any case, having separate declarations for interests and assets recognises the different nature of such diverse goals as wealth monitoring and preventing and managing conflicts of interest (OECD, 2011[1]). Separate processes may also provide a more tailor-made approach to the needs of the verification agency considering that verification of assets requires yearly declarations and a contrast method against other relevant financial information whilst an interest declaration and verification may be made on an ad-hoc basis or when an emerging conflict of interests arises.

Box 4.3. Categories of Asset and Interest Declaration Forms

The specific types and scope of declaration forms can vary depending on the purpose for which they are used or the types of officials that are required to comply with them:

Separate declarations for interests and assets

This approach recognises the different nature of such diverse goals as wealth monitoring and control of conflicts of interest. For example, in Portugal political office holders and some other categories of public officials submit both declarations of assets and declarations of interests where the latter are directed at the control of incompatibilities.

Tax declarations and declarations of interests

Subject to the obligation to submit assets and/or income declarations to tax authorities. In addition, officials have the duty to submit separate declarations of interests to an ethics commission or anti-corruption agency. The principal rationale here is that public officials’ assets and income are to be monitored in the same way and within the same system that covers other residents.

Different declarations for different categories of public officials

Declarations are varied on the levels of seniority of officials. The rationale is that officials of higher rank must be subject to stricter requirements. An example of this approach is Ukraine, where declaration forms consist of six parts. All officials fill in Parts 1-3 where income and financial liabilities are declared. Only higher categories of officials fill in Parts 4-6 where data about assets are required.

Different declarations for public officials and for related persons

This option is relevant in systems that not only oblige public officials to state data in their declarations about their spouses and other related persons, but also request separate declarations from these related persons.

Source: (OECD, 2011[1])

4.2.3. Streamlining the submission process of asset declarations

The Standards in Public Life Act provides for the submission and review mechanism of asset declarations in Malta. For Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries, the Cabinet Secretary is responsible for receiving and checking the information contained in the declarations, who then tables them in the House of Representatives. Similarly, MPs’ declarations are submitted to the Speaker of the House of Representatives. The Speaker then forwards only declarations by MPs as Ministerial declarations become public when tabled.

The review of asset declarations for MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries falls under the Commissioner’s remit, who is responsible for examining and verifying these declarations. The Commissioner may also provide recommendations in the form of guidelines with regard to any person who fails to make any declaration or who makes an incorrect declaration in a manner which materially distorts its purpose, in accordance with Article 13(1).

The Ministry of Justice could consider a legal reform to amend the Standards in Public Act to allow declarations to be submitted directly to the Commissioner

The compilation process of asset declarations entails several particularities. First, the process must be made through the Speaker, which only adds a layer to an already complex process. Second, the Commissioner does not have direct and expedite access to the summary of income tax and as a result, to access this information, the Speaker must ask for the consent of each MP every year to pass this information to the Commissioner. This procedure relies on the submission of the following information per elected or appointed official:

The corresponding declaration (after his/her appointment and on an annual basis)

A summary of the income tax return

The declaration of annual income (only in the case of ministers)

Similarly, the compilation procedure includes an excel sheet for each official, that is drawn up by the Commissioner’s office to facilitate comparisons of the data on a yearly basis. The excel sheet also enables the Commissioner to identify and request further clarifications if inconsistencies arise. Depending on the outcome of the analysis, the official may need to re-submit the annual declaration.

Asset declarations by MPs, as established in Article 5(1) of the Code of Ethics specifies that they should be received and kept by the Speaker. Stakeholders expressed a need for a more streamlined process on compiling and verifying assets declarations. As explained, the current process requires the intervention of the Speaker, Cabinet Secretary and compilation of the information by other institutions such as the Commissioner for Tax Revenue. These delays may mean that by the time the Commissioner gets the information, much of the data might be irrelevant.

The Ministry of Justice could consider amending the Standards Act to allow the Commissioner to receive all the submissions, for example via an electronic system, rather than the declarations going to two different individuals in writing. Similarly, an amendment to Article 4(5)(a) of Chapter 372 would enable the Commissioner for Revenue to share tax declarations submitted by Members of Parliament directly with the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life (in the same manner as such information is currently shared with the Speaker of the House). Online access by the Commissioner may also be a possibility, by way of having a shared folder, in which the Commissioner for Revenue uploads relevant information. According to Maltese authorities, these options may require further internal discussions between relevant authorities to help the fine-tuning and materialisation of these options.

In any case, it would be beneficial for the Commissioner to have access to relevant tax information which is pertinent to their functions. Furthermore, the system of electronic submission could be configured to allow access to as many institutions and individuals as it may be necessary. In this respect, access to information could be simultaneously shared with the Speaker, the Cabinet Secretary and the Commissioner, compiling all relevant information in one single system.

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life could consider establishing an electronic system for submission of asset declarations

Currently, in Malta, there is no electronic submission system to simplify and streamline the asset declaration process or ease comparison of different sources. This may result in cumbersome reporting obligations and act as a deterrent to reporting information quality. In particular, stakeholders noted that many institutions required the same information and that the lack of information sharing among them was contributed to inefficiencies in the system.

Indeed, setting clear and proportionate procedures to manage assets declarations is key for the success of the system. As is the case in other countries, an electronic system simplifies the submission process by making the declaration form more user-friendly, reduces the number of mistakes made in the forms, facilitates further analysis and verification of declarations, and improves data management and security (Box 4.4). Electronic filing (e-filing) may help raise the level of compliance with submission requirements (Kotlyar and Pop, 2019[13]).

In addition, electronic submission also allows for an effective automated risk analysis. This analysis would certainly depend on external factors, like access to external sources of information through automated data exchange. There are also challenges of data quality and availability. These issues create a complex process involving various legal, technological, financial, and institutional aspects. It requires inter-agency co-operation and high-level political commitment (World Bank, 2021[2]).

Box 4.4. Electronic submission of asset declarations in France

The current asset and interest disclosure system in France is regulated by the 2013 Law on Transparency in Public Life, which is administered by the High Authority for Transparency in Public Life (Haute Autorité pour la Transparence de la Vie Publique, HATVP). The initial scope of the Law covered approximately 10 000 public officials. It incrementally expanded to reach about 15 800 public officials as of 2018.

Public officials must submit to the High Authority, within two months of taking office or beginning of their mandate, two declarations: a declaration of assets and a declaration of interests. Public officials must also submit a declaration of assets no later than two months after termination of their functions or before the end of term for elected officials. In between, they must update their declaration of assets in case of substantive change (inheritance, acquisition of a property, etc.). If there is no substantial change in assets, the filers do not need to file a new declaration.

In 2014, all declarations were received in paper format only. Starting in March 2015, declarations submitted to the High Authority could either be sent by registered letter with a confirmation receipt or submitted in person at the High Authority, which issued a receipt confirming the submission or through the online service ADEL. Since October 2016, all declarations are filed online. Filers may contact a dedicated hotline (by phone or email) if they have questions, and guidelines are provided online for each step of the process. Beyond the declarations, the High Authority recommends online submission of all documents accompanying the declaration (e.g. blind trust, official notice of appointment etc.).

To register in the electronic filing system, filers need to use a mobile phone number and a valid email address. Registration is validated through text message. Text message validation is also used when a new declaration is filed or when public officials try to access their confidential personal information. The official can also choose to register using an official email address (gouv.fr, assemble-nationale.fr or senat.fr).

Electronic disclosure systems can also vary significantly in functionality, design, level of complexity, or authentication methods. In some systems, for example, declarations are collected with the aim to do a preliminary data validation, followed by a more in-depth analysis of emerging discrepancies (Box 4.5). There is also large variation in how to authenticate the data, as in some systems digital signatures are used, while in others, authentication relies on a two-step process using cell-phone numbers or email confirmations (Kotlyar and Pop, 2019[13]).

Box 4.5. Electronic disclosure systems in Argentina and Mexico

Argentina

Argentina transited to an online system for the submission and management of asset declarations when it became clear that the filing requirements would rapidly overwhelm the oversight entity’s ability to fulfil its mandate, as the number of public officials required to file an asset declaration currently stands at approximately 36 000.

As a result, the system became highly automated, including online declaration forms; online submission and submission compliance processes; and electronic data storage, records management and reporting. Software was developed in-house by a consultant which filers can download from the Anti-Corruption Office’s (OAC) website or access on a CD-ROM.

The software requires filers to complete all required fields before the form can be submitted, reducing the number of formal errors or incomplete or incorrectly filed declarations. It also automates the detection of discrepancies between a filer’s declared income and changes in income and assets over time. The system also enables the systematic verification of the top 5% of most senior officials as well as electronic verification and targeted audits of disclosures based on categories of risk of the remaining 95%. The Asset Declaration Unit is able to verify around 2 500 declarations a year.

Mexico

In Mexico, since 2002, all federal public servants are required to complete and present their declarations through the “Declaranet system”. The first step consists of establishing the public servant’s electronic identity, which is completed online in a few minutes, resulting in the generation of a pair of passwords and a digital certificate. Public servants can use these protected keys and certificate to electronically sign the declaration for a period of five years.

Once the Declaranet application has been downloaded, public servants enter the required information. All data is encrypted, and the information is kept confidential. Properly completed declarations are digitally signed and electronically filed with the Secretaria de Contraloria y Desarrollo Administrativo (SECODAM) which electronically acknowledges receipt of the declarations.

SECODAM is responsible for verifying the asset declarations and for initiating investigations when illicit enrichment is suspected. Information from reports is organised as a matrix of facts that can be analysed along vertical and horizontal dimensions, making it possible to track the history of assets through examination of the acquisitions, sales, donations and inheritances of the public servant. It also allows examination of bank records to ensure that savings and expenditures are consistent and in line with the public servants’ known sources of income. SECODAM then also cross-checks the reported information using information collected by other public institutions.

Source: (U4, 2015[15])

Overall, the benefits of an electronic system must be analysed in detail against its cost and existing technological barriers and conducting a preliminary assessment becomes of the outmost importance. This must also go hand in hand with a preliminary risk assessment exercise to determine the fields and information to be requested, verified and ultimately contrasted. In any case, systems of electronic submission will save, in the long term, financial and human resources by eliminating the need for physical storage space and allowing a proper and automatised preliminary review. Both of these help institutions save time and resources that could very well be invested in other stages of the review process (Kotlyar and Pop, 2019[13]).

Considering the difficulties of manual collection and the advantages of a system of electronic submission, Malta could consider a few issues when moving forward. First, it must conduct an initial assessment of probable amendments to its legal system that allow for electronic submission. The Ministry of Justice could conduct such an assessment, and cross-reference legislation pertaining to privacy, use of confidential information and data protection. In this respect, the Ministry of Justice could conduct a review of the Standards in Public Life Act, the Income Tax Management Act and the House of Representatives Privileges and Powers Ordinance. For Ministers, the Cabinet Manual should be amended to reflect any changes. A balanced approach and protecting confidential information are key parts of this assessment.

Second, the Commissioner could assess human resources and/or expertise to develop and maintain the system or even the needs of declarants in terms of training. This also includes assurances on how to maintain security and stability of the system. For example, like in other OECD countries, Malta could consider the web-based application ADEL used by the French government, which complies with the “Référentiel Général de Sécurité (The General Security Standard) in terms of data security and is based on an asymmetric encryption.

Third, Malta could consider from an early stage to whom to grant access to this system, as much of this information could be useful for other agencies with an anti-corruption remit. In particular, Malta could consider locating the system with the Commissioner and granting direct access to the Office of the Attorney General, the Financial Intelligence Analysis Unit and the Police, as much of this information could be useful in the investigation and prosecution of money laundering and corruption cases. Such access would also need to be explicitly catered for in an upcoming legal reform.

Finally, Malta could consider including within its electronic submission systems a few automatic filters to help streamline the process and lower the reporting burden (see for example Box 4.6).

Box 4.6. Pre-populated information in asset declarations in the United States

Under the Ethics in Government Act (EIGA), as amended, the U.S. Office of Government Ethics (OGE) is responsible for establishing and supervising a public financial disclosure program for the executive branch. This public financial disclosure system has existed since 1978. In 2012, the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act, as amended, directed the President, acting through the Director of OGE, to develop an electronic system for filing executive branch public financial disclosure reports. As a result, OGE developed a system named Integrity to collect, manage, process, and store financial disclosures.

Pre-Population Tool: Integrity allows a filer to “pre-populate” a financial disclosure report with data from a prior new entrant or annual report. Integrity can also import data from any number of previously filed periodic transaction reports (OGE Form 278-T), and the system specifically allows the filer to choose which periodic transaction reports to include or exclude.

Filer Wizards: Integrity improves accuracy by using wizards to prompt filers to provide information they might otherwise forget to report in an initial submission. Aiming to reduce the burden on the filer, however, OGE limited this targeted assistance to areas where filers make the most mistakes. In OGE’s experience, these areas involve financial interests related to the outside employment and retirement plans of the filer and the filer’s spouse. Integrity’s wizards pose only those questions that are relevant to an individual filer. For example, if the filer lists a position outside the government, Integrity will walk the filer through the wizard with questions focused on the types of income and assets associated with that position; if a filer has no outside positions, the system will skip the wizard. Example: filer selects “university/college”, position – “professor or dean”, then the system will choose a specific path through the wizard and ask only the most relevant questions. “Wizard” is a dynamic system that asks questions as needed; eliminates the risk that the filer will forget to supply some information later, as it happened with paper forms.

Auto Complete: OGE has programmed the names of over 13 000 financial interests into Integrity and plans to add additional names in the future. The asset name autocomplete feature suggests possible matches for entries as a filer is typing. Another auto-complete feature will help filers with more complex holdings. For filers with private investment funds that do not qualify as excepted investment funds, Integrity allows the filer to report the underlying holdings of the funds and associate them with the “parent” asset. The auto-complete feature will suggest a list of possible parent assets by drawing from the names of assets that the filer has already entered.

Source: (Kotlyar and Pop, 2019[13])

4.2.4. Amending the legal and institutional framework for the compilation and risk-based review process of asset declarations

As is currently the case, once the information has been received by the Commissioner, an internal review mechanism is triggered. This mechanism was developed by the first Commissioner and consists of a methodology for the review and verification of asset declarations (Box 4.7).

Box 4.7. Internal procedure for the review of asset declarations by MPs, Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries in Malta

The Commissioner maintains an excel sheet for each official (MP, Minister, and Parliamentary Secretary). To assess the information available on each official each year, data from different sources is inputted into the excel sheet allowing to compare how the amounts and assets have changed from one year to another. Each source of information is clearly identified.

A senior official within the Commissioner’s office reviews the information populated and lists any queries or clarifications that are necessary.

In cases where a public official has carried out a property transaction during the year, a copy of the public deed is requested. This, to understand the financing of property acquisitions as well as the possible movements in bank balances/investments and the possible sources of financing of future property acquisitions.

In cases where the movement of assets and/or liabilities do not make sense with i) the income illustrated on the return completed by public officials; ii) with the extracts of income derived from the Commission for Revenue in the case of MPs; and/or iii) with other facts known by the Commissioner, specific clarifications are requested.

The respective public official is given 14 days to reply. All communications are done in writing and a separate file is opened to maintain all correspondence.

The senior official within the Commissioner’s office reviews the documentation received. If deemed necessary, further information or clarification is requested.

Depending on the outcome of the analysis, the public official may need to re-submit the annual declaration. Depending on the error or omission, further actions may be taken, or the file could be concluded satisfactory. In all cases, a concluding memo is included in the respective file.

Source: Questionnaire on the office of the Commissioner for Standards in Public Life, 2021

While the Commissioner for Standards serves a critical role in reviewing asset declarations, the current set-up could be reinforced. First, the means allocated to the Commissioner to fulfill this role are insufficient, both in terms of the legal instruments and human resources. For example, the Commissioner has a very limited number of personnel for the review and verification of all declarations. Similarly, no expedite access has been granted to databases and registries in other parts of Government, such as tax returns. Bank accounts and assets from other jurisdictions are also out of his remit, as Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) requests can be accessed only through law enforcement agencies. Malta could consider amending Art 4 (5) (a) of the Income Tax Management Act to allow access of the Commissioner to this information. Without accessing this information, it is difficult for the Commissioner to identify significant issues in asset declarations, including illicit enrichment and hidden or unreported assets. In sum, without the capacity to contrast relevant financial information, asset declarations for elected and appointed officials in Malta have become an exercise of verification rather than a tool to detect and prevent corruption. The following recommendations aim at providing feasible solutions to these outstanding issues in the review process.

Malta would benefit from a more co-ordinated approach to its asset declaration system, including by providing the Commissioner with the necessary tools to access and verify relevant information

For an asset declaration system to be effective, an independent body with the necessary human and financial resources must verify the data. Most importantly, it is necessary to protect the institution responsible for asset declaration systems against undue influence (OECD, 2011[1]). Providing such institution with the necessary human and financial resources to comply with its task is vital for its success. Although the current legal set-up of the Commissioner fits well within these features, some concerns remain regarding the necessary breadth to carry out his functions.

The Commissioner should consider strengthening its asset declaration review team. This could be done by assigning a larger team for the review of declarations and providing the team with the necessary technological tools and trainings for assessing declarations. For example, by creating specific profiles in accordance with the needs of the Commissioner and merit-based processes for selection. Other issues that may affect the transition to an electronic system may be a weak digital culture across the administration, modest resources, as some initial technical difficulties. Therefore, at the inception of the system, and to overcome public officials’ resistance to new technologies, the Commissioner may develop an online instruction portal for its existing and future review team, on the usage and functionalities of electronic submission and how to better use this information in the identification of “red flags”.

As stated, a verification agency should have sufficient powers and resources to perform its duties. Such powers could include access to government registers and databases, including tax information, company register and registers of real estate and vehicles, right to obtain information and records from public and private entities, access to banking and other financial data, and the possibility to request or access information abroad. At the same time, the verification agencies are usually not law enforcement bodies and lack certain tools that a criminal investigation can employ, e.g. special investigative techniques. This highlights the need to understand the limitations of administrative bodies in charge of verification and the importance of co-operation with law enforcement bodies. It also affects the debate on the level of dissuasive sanctions, as shown below (World Bank/UNODC, 2023[3]).

As stated before, comparing data from different sources allows for the identification of manifest discrepancies and for the verification of inaccuracies and omissions in declarations. While some useful data sources – including property land and vehicle registries – are publicly available in many countries, others – such as company securities registry, where the identity of holders of company securities are registered, international and domestic banks or other financial institutions – may require enabling provision in the law as well as special collaboration arrangements. In this sense, an effective verification process – and potential further investigation process – depends on an effective collaboration between the controlling agency(ies) and other institutions. In certain cases, a verification process to cross check information involving criminal investigative bodies, equipped with the legal means to obtain information from various sources, could be potentially useful (OECD, 2011[1]).

In Malta, there are major challenges for effective co-ordination between stakeholders and for ensuring that relevant information is shared in a timely manner. As stated previously, the mere process of accessing assets declarations and income tax returns by the Commissioner requires several steps, considering that the Commissioner is not empowered to directly receive nor access any of these, despite being directly responsible for examining and verifying the declarations (Government of Malta, 2018[5]).

There are several avenues Malta could consider when addressing co-ordination challenges. First, Malta could conduct the necessary legal reforms in order to allow the Commissioner access to certain information necessary for the fulfilment of its duties. Such legislative reform would include giving the Commissioner the autonomy to enter into inter-agency agreements and Memorandums of Understanding (MoU). These could include a specific MoU with the office of the Attorney General and the Police to include the possibility of referring a matter for criminal investigation if suspicions of illegal activity arise (GRECO, 2018[8]). One possible avenue would be to introduce within the MoU a system whereby the Commissioner investigates and where the Commissioner is aware of suspected criminal wrongdoing, he/she is to report the same to the Police with the possibility of sharing the same report/information with the FIAU. Similarly, another MoU could be signed with the Financial Information Unit to allow the possibility to discuss specific cases on asset declarations being analysed by the Commissioner, as well as to share and discuss the results of the review of asset declarations on a policy level. In line with this, the FIAU can use that information received from the Commissioner as part of it processes which could also lead to further disseminations to the Police, if deemed necessary. During consultation meetings, Maltese authorities were of the view that co-operation and support may also extend to specific training support offered to officials of the Commissioner by the FIU (such as when it comes to transaction monitoring).

Moreover, as previously stated, legal provisions could be in place to allow access to other data that is not already publicly available, e.g. banking and financial data, when in the course of an investigation. Maltese authorities were also of the view that the Commissioner should be legally empowered to be able to ask for such information and obtain it directly from the source (e.g. credit institutions). This approach could help solve several existing difficulties in the institutional framework, including the lack of co-ordination and lack of relevant provisions on sharing relevant information.

Regardless, such agreements could aim at clarifying their relations, specifying the conditions of their co-operation, and formalising information sharing procedures. Regarding the latter, access to information can be subject to further conditions – for example, it can be granted in order to investigate specific violations only or when a criminal case has been opened, or it can simply require that requesters provide grounds for their request (OECD, 2011[1]). Examples from other jurisdictions could be used as inspiration by the Commissioner to define and set the inter-agency agreements and memorandums of understanding required to fulfil their duties (Box 4.8).

Second, the Commissioner lacks important powers such as the rights to access documents/records from other public authorities – tax, land/real estate, motor vehicle and other registers, and personal ID databases, etc. – and data from banks and other commercial entities. However, they can conduct property searches and obtained access to the central personal ID database.

Discussions with key stakeholders underscored the need to ensure the Commissioner’s access to information held by other agencies in order to identify discrepancies and verify inaccuracies and omissions. This cross-check would be key to ensure an effective verification and audit process of asset and interest declarations.

Box 4.8. Co-operation and databases cross-checking within the declaration system in France

To fulfil its mandate, the French High Authority for Transparency in Public Life (Haute Autorité pour la Transparence de la Vie Publique, HATVP) requires a high level of co-ordination and co-operation with institutions and individuals who detain information useful for the monitoring process of asset and interest declarations.

Considering this, the HATVP has signed several inter-agency agreements and protocols with public institutions aimed at ensuring better co-ordination and facilitating the exchange of relevant information:

In 2016, the HATVP and the tax administration signed a protocol to clarify their relations. Since January 2017, staff members of the HATVP are allowed to connect directly to some of the tax administration databases and applications to carry out routine checks, especially to value real estates, to access the list of registered bank accounts or to access cadastral information.

In September 2017, the HATVP and the National Anti-Money Laundering Service signed a protocol. This protocol, together with legislative developments conducted in December 2016, allows both institutions to share relevant information to their respective controls and investigation procedures.

Regarding co-operation with courts, the HATVP and the Directorate for Criminal Matters and Pardons and the HATVP and the Attorney General signed a memo and an instruction, respectively, to formalise information sharing procedures with prosecutors and audit courts.

In 2019, the HATVP signed a protocol with the French Anticorruption Agency to ensure better co-ordination of actions between the two institutions with complementary missions.

Finally, international co-operation is critical in fighting corruption (Burdescu et al., 2009[17]). Interaction and co-operation with relevant international institutions and counterparts may facilitate knowledge sharing as well as project supporting for the development of specific institutional and legal standards. Considering this, the Commissioner could develop a strategy to engage in both formal and informal agreements with authorities in other jurisdictions to facilitate technical assistance and co-operation activities for the verification of assets and interest declarations. Similarly, it could consider inviting some of them to participate as observers in the technical working group on asset and conflict-of-interest declarations to compare and measure the capabilities of its system against other examples.

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life could develop a risk-based methodology that considers inherent risks such as inconsistencies in the disclosure form, unjustified changes in wealth and external risk factors

Automated risk or “red/risk flag” analysis helps to filter declarations and prioritise verification by ranking declarations according to their risk level. It also increases the capacity of the agency tasked with verifying assets and interests of officials by focusing the agency’s limited resources on the verification of high-risk declarations. Moreover, automation can remove discretion, minimises manual processes, and improve the system’s impartiality and credibility (World Bank, 2021[2]). An automated revision would allow the verification process to be streamlined and prevent unnecessary impediments, such as short time limits for verification procedures or reduce the possibility to challenge each step of the proceedings by declarants.

There are different approaches that can be taken, depending on the specific needs of the country when defining “red flags”. In some cases, a mere review of declarants and their level of risk would suffice. This could very well include the usage of categories of officials as the basis of defining risk (e.g. politically exposed persons, decision-makers, directives or officials involved in public procurement processes, etc). In Malta, the review of declarations of elected and appointed officials has two characteristics. First, the sample of declarations is quite limited: currently the Commissioner for Standards reviews declarations from 89 MPs in Parliament, of whom 19 are Ministers and 6 are Parliamentary Secretaries. Since every Minister and Parliamentary Secretary submits a separate declaration in addition to his/her declaration as MP, this makes for a total of 114 declarations. Therefore assigning categories of officials as a risk factor would not be appropriate. Similarly, all elected and appointed official are always considered high risk and require the application of enhanced due diligence measures, considering their level of exposure and decision making capacity at a policy level. Therefore, in Malta, a risk-based methodology must be based solely on the kind of information reported and the content of other sources of “red-flags”.

To develop a risk analysis process, the Commissioner must first consider developing a risk analysis framework. Several guides provide the basis for this preliminary analysis (Box 4.9). When determining risk factors, the Commissioner could consider, for example, the external sources such as media reports on assets declarations, the comparison of declarations over time to detect inconsistencies, and the cross checking with other government databases. Whether the selection of declarations to be verified is random, risk-based or made using another method, some balance appears useful between systematic verification according to rigid criteria and an ad-hoc approach acting on particular warning notifications or other signals (OECD, 2011[1]).

An electronic system would then allow the use of algorithms to detect risks in the submitted declarations according to these pre-set “red flags” or indicators. External sources also may point to at-risk individuals or at-risk situations and can be used to inform the risk analysis.

Box 4.9. Developing a Risk Analysis Framework: General Considerations

The automated risk analysis limits the number of declarations that undergo the more labour-intensive manual verification and focuses such verification on high-risk declarations. The automated risk analysis is both a prioritisation and detection tool. It helps prioritise the verification of numerous declarations. In addition, it can be used to better detect violations following the risk indicators identified by the analysis. The automated risk analysis helps to remove or limit the discretionary decision-making concerning the targets of verification. General considerations include:

Use of a risk-based approach to trigger and prioritise verification when inherent risks are found in the disclosure form, such as the position/duties of the declarant. Systems which automatically trigger the verification on formal grounds (e.g. late submission) are ineffective as they overburden the verification agency. This is especially relevant for systems where the number of disclosures is substantial and not matched with the resources to verify them.

When the number of mandatory verifications is substantial, the verification agency has to prioritise its work by focusing on high-risk declarations. Such prioritisation should be transparent and based on clear criteria limiting discretionary decision-making. The system may categorise declarations submitted by certain top officials as high-risk by default. This will give credibility to the system and avoid focus on low-level officials or petty inconsistencies.

External signals (e.g. media reports, complaints of citizens or watchdog NGOs, referrals from other authorities) should take priority. The agency should verify them if they give rise to a substantiated suspicion of irregularity. Anonymous reports about verifiable facts should also be included.

The verification should include IT solutions that automate certain operations. Such solutions can perform a risk analysis of each declaration, compare several declarations of the filer or compare with declarations of similar filers. Applying analytical software to the disclosure data can help to find patterns that can be then used to develop red flags for future verifications.

Cross-checking disclosures with other government held registers and databases is an important element of the verification that effectively uses government data. The system can also automate such cross-checks and perform them shortly after the declaration is filed or even at the time of the submission.

Source: (World Bank, 2021[2])

Considering this, the Commissioner could include as risk factors the following criteria and, based on those, assign thresholds for an automatic review in the system (OECD, 2017[18]). A key part of assigning these risk factors is analysing financial flows. In particular, the internal coherence of declaration should be the first review conducted by the Commissioner. In the review process, risk factors may be triggered when the financial relation between declared items does not add up. An example of this is determining as an alert any asset acquired above annual salary (or above XX % of annual salary) for the elected official or that of a family member. Other financial criteria to be considered is (OECD, 2017[18]):

Analysis of financial information against market value: Stocks that should be pricier or assets that are declared at a lower absolute numerical threshold. This review could be sequenced, to reflect the differing income and wealth levels.

Outstanding disparities between years: Do incoming and outgoing financial flows balance over the duration of several years (separately for the public official and for the entire family)?

Drop in wealth: total amount of savings drops by at least XX % and at least XX € while at the same time the value of all other assets and loans granted to third parties remains the same (or with only little deviation).

Logical relation between items: determine a threshold that detects combinations of fields that in reality can usually not work (e.g. reporting income from business, but not reporting ownership of business).

Analysis of patrimony, related to income and savings: any asset above “initial savings + income in office” (initial = beginning of period/year), current savings above “initial savings + income in office/as declarant”, current savings above “initial savings + salary received”.

Loans granted to third parties: establish as a red flag any loans that have been given to a Politically Exposed Person (PEPs) or people within international debarment lists.

Sub-annual expenses related to the purchase date of movable or real estate: enough accrued income (+ savings) available at the time of purchase, or only by the end of the year.

Similarly, as stated previously, asset declarations need to be compared against other databases over time, so that “red flags” can have a method of contrast. Normally, a filer will “pre-populate” the report with information from a previous report before adding, deleting, or revising entries. In that case, an official assigned to review the report can use an automated comparison tool to examine only items that have changed since the previous report (Kotlyar and Pop, 2019[13]). This tool significantly reduces the workload of the reviewing agency and makes their reviews more effective by highlighting items that have not previously been reviewed. Moreover, the financial baseline for the beginning of the period generally comes from a previous declaration and so changes in the declarations are one of the fastest ways to identify risks. Malta could consider establishing the following as risk factors in the contrast review (OECD, 2017[18]):

“Jump” in income: more than XX % increase in annual income.

Patterns of income: more than XX years in a row or within a total of XX years receipt of monetary gifts or similar “income for free” (casino/lottery winning, etc.).

Selling assets: An asset disappears without relevant income for selling it.

The risk analysis could also consider as “red flags” external sources of information. Although these sources are not part of the declaration nor its information in other government databases, it can be useful to analyse whether due diligence is required in any of the declarations being reviewed by the Commissioner. Such external sources of information are, for example:

Media review: journalist and civil society analyse publicly available asset declarations against other information provided to them by whistleblowers or journalists in other jurisdictions. When verifying declarations, the reviewing institutions could consider conducting a review of publicly available information and include this as a “red flag” in their review process.

Secondary employment: as MPs in Malta may have secondary employment, the Commissioner may consider compiling and updating a list of these secondary employments and rank them by level of risk. This would allow them to determine which officials are at higher risks and therefore which declarations to consider in further detail. Sources of second income and data on the employer are of key importance for this.

Information provided by partnering organisations (law enforcement agencies): Review together high-risk areas and share information when “red flags” are triggered. Similarly, law enforcement agencies may point to individual cases which are already triggering “red flags” in their own systems.

Another tool that may be useful when determining “red flags” is determining key words that flag patterns or empty fields, in particular: family members exist, but there is no information for family members’ income or assets or it is all set at zero, assets with value “unknown”, new movables without purchase price, savings/bank deposits empty or zero, income empty or zero.

Finally, a draft set of risk criteria should be tested and run on the electronic system to see how many declarations are flagged by the rules. If necessary, some of the thresholds can be lowered or raised manually to adapt the number of flagged declarations down/up to an appropriate, workable level (OECD, 2017[18]).

The Commissioner for Standards in Public Life could elaborate a process for the verification of asset declarations, and pilot its electronic submission tool against identified risks

Implementing an automated risk analysis entails additional and complex challenges. Verification agencies may lack in-house IT expertise or the funds to outsource the development of a system or assure its support. Standard processes ensure that institutional memory of what verification means in detail is documented in all steps, disregarding any staff changes. Documenting the standard steps can also facilitate awareness and co-ordination among the oversight bodies (OECD, 2017[18]). In fact, criteria can be expanded over time and adjusted within the process. Regardless, a few issues should be considered when drafting this process.

First, there must be non-ambiguity of the data being requested. When selecting the risk criteria or “red flags”, information requested must be clear and readable by a software in a non-ambiguous way. Pull-down menus are extremely helpful in this task, but it is up to the verifying authority to determine clear and simple fields, as well as the thresholds to be reviewed.