This chapter takes stock of current and planned climate policies in Lithuania, situating these within the current policy context at the EU level. It describes policies included in the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP) adopted in 2019 and further policies reforms made since, with a focus on the transport, energy, industry and agriculture and forestry sectors. It assesses the adequacy of these policies for meeting Lithuania’s revised climate targets, offering good practice insights from other OECD countries on possible policy reform options.

Reform Options for Lithuanian Climate Neutrality by 2050

2. Lithuania’s current and planned policy mix

Abstract

The EU’s Climate and Energy Framework, adopted in 2014, set the goal of reducing EU-wide GHG emissions by 40% by 2030 (compared with 1990 levels) (European Commission, 2014[1]). Under this framework, all EU member states were required to submit National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs) to the EU Commission in 2019, establishing a ten-year plan that details member states’ contributions to the EU’s 2030 climate targets. The EU has since updated its climate policy ambitions, targeting a reduction of GHG emissions of at least 55% by 2030 in the European Climate Law, adopted in 2021 as part of the European Green Deal. To meet these updated targets, the European Commission has also proposed a number of legislative reforms known as the Fit for 55 package.

A review by the European Commission of current NECPs found that, if fully implemented, they would amount to a 41% reduction of GHG emissions, narrowly surpassing the EU’s 2014 target but falling short of the new and increased target under the 2021 European Climate Law (for an overview of current and previous EU climate targets see Table 2.1) (European Commission, 2022[2]). Member states are therefore required to submit updated NECPs reflecting the EU’s increased ambition by 2023.

Lithuania’s NECP constitutes the primary document detailing Lithuania’s intended climate policies for the period from 2021-2030. Adopted in 2019, it integrates a number of previous policy documents including the National Energy Independence Strategy (adopted in 2018), the National Strategy for Climate Change Policy (adopted in 2012 and updated in 2019), and the National Air Pollution Plan (adopted in 2019). It was further developed in parallel to the National Progress Plan, which sets overarching economic, social, environmental and security priorities, also for the period from 2021-2030.

The NECP aims to reach an overarching GHG emissions reduction target of 9% in sectors not covered by the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), meeting the EU’s Effort Sharing Regulation (ESR) target for Lithuania as set in the 2030 Climate and Energy Framework (European Commission, 2014[1]). ETS sectors are subject to an EU-wide emissions reduction target of 43% (European Commission, 2014[1]).

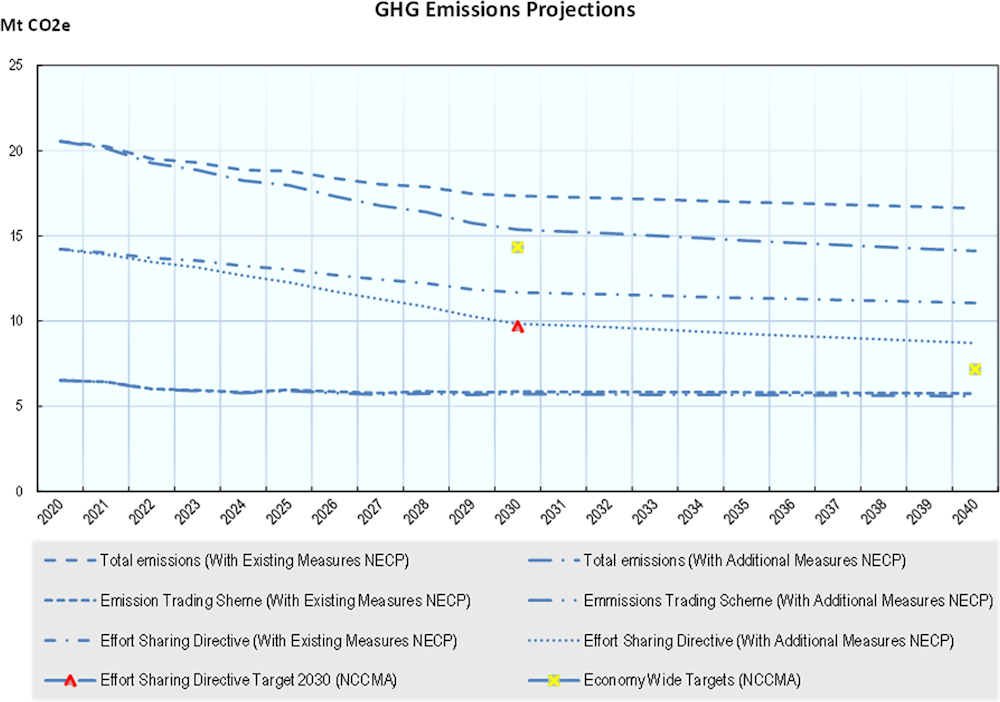

To meet the increased ambition of the European Climate Law and Green Deal, targets set in the NECP have since been updated in the Lithuanian National Climate Change Management Agenda (NCCMA), adopted in July 2021. Although the NCCMA sets overarching climate targets and defines sectoral objectives in meeting them, it does not detail the climate policies and measures to be implemented to meet these objectives. As such, in order to meet the updated targets set in the NCCMA, Lithuania will need to update its NECP. As seen in Figure 2.1, existing and additional policy measures planned in the current NECP fall short of the necessary ambition to reach the NCCMA’s targets. This report thus provides policy recommendations to be included in the updated NECP, focusing on the transport, industry, energy, and agriculture and forestry sectors.

For an overview of targets set in the NECP, the NCCMA and the associated EU target levels, see Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. GHG emissions reduction targets in Lithuania and the EU under the NECP/2030 Climate and Energy Framework and NCCMA/European Green Deal

|

Region

|

Sectors |

Previous Climate Targets (EU Climate and Energy Framework and NECP) |

Updated Climate Targets (European Green Deal and NCCMA) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2030 |

2040 |

2050 |

Source |

2030 |

2040 |

2050 |

Source |

||

|

EU-Wide Targets |

Economy Wide |

40% reduction (compared with 1990) |

80% reduction (compared to 1990) |

EU 2030 climate and energy framework |

55% reduction (compared with 1990) |

100% reduction (compared with 1990) |

European Climate Law |

||

|

EU ETS |

43% reduction (compared with 2005) |

EU 2030 climate and energy framework |

61% reduction (compared with 2005) |

Fit for 55 Package (proposed) |

|||||

|

Non-ETS Sectors |

30% reduction (compared with 2005) |

EU 2030 climate and energy framework |

43% reduction (compared with 2005) |

Fit for 55 Package (proposed) |

|||||

|

Lithuania Targets |

Economy-Wide |

40% reduction (compared with 1990) |

70% reduction (compared with 1990) |

80% reduction (compared with 1990) |

NECP |

70% reduction (compared with 1990. 30% compared with 2005) |

85% reduction (compared with 1990) |

100% reduction (compared with 1990) |

NCCMA |

|

EU ETS |

43% reduction (compared with 2005) |

NECP |

50% reduction (compared with 2005) |

NCCMA |

|||||

|

Non-ETS Sectors |

9% reduction (compared with 2005) |

NECP |

25% reduction (compared with 2005) |

NCCMA |

|||||

Note: The ETS and Non-ETS targets proposed by the European Commission in the Fit for 55 Package have not yet been officially adopted and may be subject to change.

Lithuania’s NECP details policies for five primary sectors: transport, industry, energy, agriculture, land-use, land-use change and forestry (AFOLU/LULUCF), and waste. It sets targets for each of these sectors in line with the overarching target of reducing emissions in non-ETS sectors by 9% by 2030. This amounts to targeted reductions of 9% each in the transport, industry and agricultural sectors, 40% in the waste sector, and 15% in the energy sector. Lithuania further plans to offset 6.5 million tonnes of CO2e through the LULUCF sector. For an overview of these sectoral targets, see Table 2.2.

Table 2.2. Non-ETS Sectoral Emissions Reduction Targets for Lithuania set in the NECP and NCCMA

|

Sector |

NECP 2030 Target |

NCCMA 2030 Target |

|---|---|---|

|

Transport |

-9% |

-14% |

|

Industry |

-9% |

-19% |

|

Energy |

-15% |

-26% |

|

Agriculture |

-9% |

-11% |

|

Waste |

-40% |

-65% |

|

Total Non-ETS |

-9% |

-25% |

Note: All targets compared to 2005 levels.

The NCCMA sets a long-term objective of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050, in line with EU targets. It sets interim targets of -85% by 2040 and -70% by 2030 (compared to 1990s levels, -30% by 2030 compared to 2005). The NCCMA further defines sector-specific targets for 2030, with emissions reductions of 50% in ETS sectors and 25% in non-ETS sectors (compared to 2005 levels) (Table 2.1). The NCCMA further differentiates sector-specific targets for non-ETS sectors (Table 2.2) and provides details of near-, medium-, and long-term targets within each sector, for example setting renewable energy and energy efficiency targets for 2030, 2040 and 2050 in each sector.

Figure 2.1. Measures set out in the current climate plans are not sufficient to meet recently updated climate targets

Note: The total emissions trajectories (with additional measures NECP) assume current EU legislative packages. The proposed Fit for 55 Package would significantly steepen the reduction path of this scenario by increasing the reduction target for EU ETS sectors from 43-63% by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels). If the proposed EU updates were also to be considered in the total emissions (with additional measure NECP) scenario, the economy-wide targets set in the NCCMA would potentially be surpassed.

To inform these policy recommendations, this chapter takes stock of Lithuania’s existing and planned policies and targets, assessing their adequacy to meet the updated targets set in the NCCMA and EU Climate Law. This assessment is based on a) a general equilibrium model providing an estimate of the effectiveness of policies laid out in the current NECP; b) a qualitative review of good practices in other OECD countries; and c) a review of existing assessments of Lithuania’s climate policies, including those assessed in the OECD Environmental Performance Review: Lithuania 2021 and related recommendations, the IEA’s Lithuania 2021 Energy Policy Review and the European Commission’s Review of the Lithuanian NECP.

The chapter is organised into six sections. The first considers recent developments at the EU level, summarising the proposed measures under the Fit for 55 package and European Green Deal. The following five sections detail current and planned policies and measures in Lithuania, each focusing on a particular sector. The first takes an economy-wide lens, with the subsequent sections focusing on the transport, industry, energy and agriculture sectors. The sector specific measures depicted are grouped by the type of measure, using categories from the OECD’s decarbonisation framework (D’Arcangelo et al., 2022[8]), including economic measures (subsidies, lump-sum payments, etc.), fiscal measures (taxes or tax-exemptions), regulatory measures, or complementary measures such as education or research and development EU climate policies.

Regional context: EU climate policy trends

The EU’s climate policies have changed significantly in the past two years. The 2030 climate and energy framework has been replaced by the European Green Deal, and as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU has put in place important funding mechanisms, with the aim of financing a “green recovery”. While many of the policy processes are ongoing, with particularly the European Green Deal still awaiting adoption of many legislative proposals, the proposed changes would have significant bearing on Lithuania’s climate policies in the future. This section briefly describes the current EU climate policy landscape and, where possible, provides insights into the (likely) effects of EU climate policies on Lithuania.

Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)

As the central part of the NextGenerationEU plan for recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the Recovery and Resilience Facility provides member states funding for recovery projects. Each member state is required to submit a plan for approval to the European Commission detailing how they would use their allotted amount. Of the funding provided, 37% should be spent on climate relevant initiatives (European Commission, 2022[9]). Lithuania’s EUR 2.2 billion plan was endorsed by the European Commission in July 2021. It aims to spend more than EUR 800 million, or 37.8%, on climate projects including supporting investments in solar and wind projects, promoting electric vehicles, renovating buildings and restoring peatlands (European Commission, 2022[10]).

EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities

In 2020, the EU established a taxonomy for sustainable activities, a classification system that aims to provide clarity to investors on which activities and technologies are in line with EU climate targets and can be considered as sustainable investments. The taxonomy has gradually been updated and expanded through delegated acts. For example, in 2022, a delegated act detailed conditions under which nuclear energy and natural gas can be considered sustainable under the taxonomy (European Commission, 2022[11]).

Fit for 55 package

The European Green Deal, approved in 2020, is a set of policy initiatives with the overarching goal of a climate-neutral EU by 2050. In light of this ambition, the 2021 European Climate Law sets an interim emissions reduction target of 55% by 2030 (compared with 1990 levels). In order to meet this target, the European Commission has developed a set of proposals, also known as the Fit for 55 package, to review and update EU legislation, putting in place new climate policy initiatives in line with the increased ambition of the Green Deal. The Fit for 55 package was submitted to the European Council in 2021 and is currently being discussed across several policy areas, such as environment, energy, transport, and economic and financial affairs (European Council, 2022[12]). The package includes the following legislative proposals and climate policy initiatives:

EU-Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS)

The Fit for 55 package proposes to update the EU ETS, increasing its emissions reduction target from 40% to 61% by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels) (European Council, 2022[12]). This would entail increasing the annual reduction factor from 2.2% to 4.2%. The proposal also suggests that maritime transport be included in the ETS and that free allowances for aviation and sectors covered by the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) be phased out. It also includes an offsetting scheme for global aviation emissions through Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). The proposal further calls for an increase in funding availability for the modernisation and innovation funds, to be sourced from the increased ETS revenues. Finally, the market stability reserve (MSR) is to be updated.

In addition to the proposed amendments to the current ETS, the Fit for 55 package also proposes the establishment of a parallel ETS II for the transport and buildings sector. The ETS II would target an emissions reduction in these sectors by 43% (compared to 2005 levels) (European Council, 2022[12]). It would be implemented at the fuel distributer level, encompassing both sectors, with the price determined by the carbon intensity of fuels (Erbach and Foukalova, 2022[13]). The ETS II is proposed for 2025, with mandatory reporting by fuel distributers to start in 2024.

Accompanying the ETS II, the Fit for 55 package proposes establishing a Social Climate Fund to help mitigate potential adverse socio-economic impacts of the new ETS on vulnerable households and micro‑enterprises. The fund would receive EUR 75.2 billion from 2025-2032 and fund projects such as, direct income support, energy efficiency renovations in buildings, decarbonisation of heating and cooling and improved access to low-emissions transportation. The financial envelope of the Social Climate Fund should eventually comprise 25% of the revenues generated by the ETS II, with proposed maximum amounts to be received by each member state. Under the proposal, Lithuania would receive 1.02% of the funds (Wilson, 2021[14]). Lithuania currently emits 0.55% of EU GHGs and generates 0.4% of EU GDP (Jensen, 2021[15]; Eurostat, 2021[16]).

Effort sharing regulation (ESR)

The Fit for 55 package proposes to update domestic GHG emissions reduction targets for non‑ETS sectors set in the ESR, increasing the EU-wide target for non-ETS sectors from 29%-40% by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels) (European Council, 2022[12]). The distribution of domestic targets would remain determined by each country’s GDP per capita, with some flexibility depending on the cost efficiency of targeted reductions. Under the proposal, Lithuania’s 2030 reduction target would increase from 9% to 21% (European Commission, 2021[17]).

Regulation on land-use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF)

The Fit for 55 package proposes to set a binding EU-level target for net removals of CO2 (European Council, 2022[12]). The proposal sets an overarching target of climate-neutral LULUCF and agriculture sectors by 2035, meaning that all emissions from LULUCF and agriculture are offset by removals. In order to achieve this, the proposal targets removal of 310 million tonnes of CO2 by 2030 at the EU level. This is to be distributed amongst member states as binding domestic targets based on the area of managed land. A number of options are proposed for how to organise this (Vikolainen, 2022[18]). The proposal further suggests simplifying current accounting and monitoring, verification, and reporting rules. Finally, the proposal suggests expanding the scope of the regulation to include non-CO2 agricultural emissions from 2031, pending a report on this to be provided by the European Commission in 2025 (European Council, 2022[12]).

Renewable energy directive (RED)

The Fit for 55 package proposes an increase in the targeted share of renewable energy in the energy mix from 32% to 40% by 2030 (European Council, 2022[12]). The proposal also includes a phase‑out of biomass from electricity production by 2026, further suggesting new sustainability criteria for bioenergy. These include prohibiting the use of primary forests for bioenergy as well as the application of minimum GHG savings thresholds (Wilson, 2021[19]). It also suggests sustainability criteria for renewable fuels of non‑biological origin (RFNBOs). Finally, sector-specific targets and measures are suggested. In the buildings sector, renewable energy is proposed to make up 49% of energy consumption for heating and cooling by 2030, driven by a binding annual increase factor of 1.1%, 2.1% for district heating systems (Wilson, 2021[19]). In the industry sector, the proposal targets an annual increase in renewable energy use of 1.1%, with 50% of feedstock or energy carriers to come from non-biological renewable fuels by 2030 (Wilson, 2021[19]). The proposal further targets a 13% reduction in the GHG intensity of the transport sector by 2030, with a 2.2% use of advanced biofuels and 2.6% of non-biological renewable fuels. Further, a credit mechanism is proposed to promote electric vehicle deployment (Wilson, 2021[19]).

In addition to the Fit for 55 package, in May 2022, the European Commission proposed the REPowerEU package, looking to increase the EU’s 2030 target for renewable energy from the 40% envisaged in the Fit for 55 package to 45%. REPowerEU would bring the total renewable energy generation capacity to 1 236 GW by 2030, compared to 1 067 GW in the Fit for 55 package. (European Commission, 2022[20])

Energy efficiency directive (EED)

The Fit for 55 package proposes to implement an “energy efficiency first” principle, ensuring that the benefits of fuel switching are not dampened by sub-standard energy efficiency in buildings (European Council, 2022[12]). The proposal targets an overall reduction in energy consumption of 9% by 2030. This would constitute energy savings of 32.5% in final energy consumption and 39% in primary energy consumption (Wilson, 2021[21]). The proposal sets binding upper limits for energy consumption, suggesting non-binding shares for member-states. The proposal also sets new obligations and rules for public sector buildings, targeting a 1.7% annual reduction of energy consumption and an annual renovation target (to near-zero standards) of 3% (Wilson, 2021[21]). Finally, the proposal includes provisions on targeted measures to support vulnerable consumers.

Alternative fuels infrastructure and CO2 emissions standards for cars and vans

The Fit for 55 package includes proposals for new initiatives for deploying electric vehicle and hydrogen charging points, as well as other alternative fuel infrastructure, including CNG and LNG infrastructure and the supply of natural gas in ports. The proposal suggests a minimum coverage for recharging points for light and heavy vehicles (Soone, 2021[22]). The Fit for 55 package also suggests minimum CO2 emissions standards for new cars and vans. This includes a 100% emissions reductions target by 2035, effectively banning the sale of internal combustion engines after this date (European Council, 2022[12]). The proposal sets intermediate emissions reduction targets for 2030, 50% for cars and 55% for vans (Erbach, 2022[23]).

Energy tax directive (ETD)

The Fit for 55 package also proposes new minimum tax rates for fuels and rules on exemptions under the ETD. The proposal aims to align energy product and electricity taxes with the updated EU climate targets, suggesting to tax fuels according to their carbon content and environmental performance, in order to preserve and improve the internal EU fuel market and ensure that member states’ capacity to generate revenues is maintained (European Council, 2022[12]). It further proposes a simpler categorisation of fuels and a phase-out of all fuel exemptions, including those for aviation, shipping and fishing fuels. It also suggests recognising new fuels such as hydrogen (Kostova Karaboytcheva, 2022[24]).

Carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM)

The Fit for 55 package proposes the establishment of a carbon border adjustment mechanism, ensuring that the increased ambition of EU climate policy does not result in carbon leakage, i.e. production migrating to countries and regions with less stringent climate rules (European Council, 2022[12]). In effect, the mechanism would introduce some form of import tax based on a product/material’s carbon content, using the ETS price as a reference. The proposal includes multiple options for how to structure such a mechanism, including which materials would be covered, and the scope for ETS credit allocations (Kramer, 2022[25]).

Sustainable aviation and greener shipping fuels

The Fit for 55 package proposes two initiatives to reduce emissions from aviation and shipping. The ReFuel Aviation initiative proposes implementing fuel obligations for sustainable aviation fuels. It provides multiple options for how to structure such an obligation, including whether it should fall on fuel suppliers or airlines, whether the approach should be based on fuel volume or carbon intensity, and whether and how to structure possible transition periods (Tuominen, 2021[26]). For shipping, the Fit for 55 package proposes targeting a 75% reduction in the GHG intensity of shipping fuels by 2050, based on increasing annual intensity reductions, starting at 2% in 2025 and rising to 6% in 2030. The FuelEU Maritime initiative further proposes obligations for shore-side electricity use (Pape, 2021[27]).

Economy-wide climate policies

The EU Green Deal significantly increases the region’s climate policy ambitions, updating the targets set in the 2014 Climate and Energy Framework. As part of the Green Deal, the 2021 European Climate Law defines new overarching target levels and the Fit for 55 package proposes a comprehensive mix of initiatives with which to achieve these targets. Nonetheless, implementing climate policies remains primarily a task for member states. As such, the EU requires all member states to submit NECPs detailing their national climate policy mixes.

Lithuania’s original NECP, submitted to the EU in 2019, draws on a number of domestic policy initiatives such as the National Energy Independence Strategy (adopted in 2018), the National Strategy for Climate Change Policy (adopted in 2012 and updated in 2019) and the National Air Pollution Plan (adopted in 2019). It was developed in parallel to the National Progress Plan (NPP), which sets overarching priorities for social, economic, environmental and security policy. In 2021, Lithuania updated its overarching climate policy targets in the NCCMA.

The policies detailed in Lithuania’s NECP are differentiated by economic sector, covering transport, energy, industry, waste, and agriculture and forestry. The NECP also details a number of economy-wide policies, which are detailed below.

Existing policies

Lithuania’s NECP sets out a number of horizontal policies targeting economy-wide emissions reductions. Rather than setting economic incentives or introducing new regulations, these are primarily complementary policies, for example integrating GHG emissions reduction evaluations into the legislative process, mainstreaming climate change within educational programmes, extending the scope for green procurement, increasing public awareness, and funding research on climate mitigation (Government of Lithuania, 2019[3]).

Planned policies

Recently, the Lithuanian government also proposed amending current excise duty legislation. The proposed policy would increase excise duties annually from 2023-2030. It further proposes to phase-in a tax based on the carbon intensity of fuels from 2025. The tax would start at EUR 10 per tonne of CO2 and rise by EUR 10 each year, rising to EUR 60 per tonne of CO2 in 2030. ETS installations would be exempt from the CO2 element, with no price floor envisioned. Natural gas would also be exempt from the proposed legislation. Agricultural exemptions from paying excise duties would also remain, although here a quota limit would be phased-in, limiting the amount of fuel that could be consumed free of the excise duty, starting at 100 000 litres in 2024, and further decreasing to 50 000 litres in 2025 and beyond. The proposal does not include measures to recycle the generated revenue. However, due to the current energy price crisis, the Lithuanian Parliament has postponed the consideration of the proposed amendments to the excise duty legislation.

Assessment and recommendations

Lithuania’s NECP focusses on detailing sectoral policy measures. Existing economy-wide policies remain primarily complementary, aiming to mainstream climate concerns throughout government decision‑making and society more generally. However, as highlighted in Lithuania’s EPR, interlinkages between climate policy and other policy domains could be strengthened. Drawing on a number of domestic policy initiatives, the NECP co-ordinates climate action across areas such as energy security and air pollution. However, the NECP is not closely linked to the NPP, as seen by a lack of interlinkages between chapters on the Lithuanian Green Deal and economic development in the NPP (OECD, 2021[7]). This is despite the two plans having been developed in parallel.

The planned excise duty amendment is a welcome initiative that will considerably bolster progress towards meeting Lithuania’s climate targets (see also Chapter 4 on effective carbon rates). However, the policy could be expanded on. First, the exemption of natural gas from the CO2 tax element should be reconsidered, as this will incentivise investments into gas infrastructure that could lock-in fossil fuel technologies for a number of decades beyond 2030. Moreover, introducing a price floor for ETS installations would send a strong signal to businesses and investors that Lithuania is committed to reaching its climate goals, regardless of developments elsewhere in the EU. Revenues generated through the proposed tax on the carbon content of fuels should be recycled, and at least in part given back directly to consumers, as is the case in Ireland and Denmark (Box 2.1). Assessment of the planned excise duty amendment is expanded on in Chapters 3 and 4 of this report.

Box 2.1. Good practices for economy-wide climate policies

A number of OECD countries have implemented broad, economy-wide policies to reduce GHG emissions.

UK carbon price floor

The UK introduced a carbon price floor for electricity sector fossil fuel emissions covered by the EU ETS in 2013. The price floor consists of the EU ETS permit price, and a carbon price support mechanism charged on top of ETS permit prices if these fall below a pre-determined price floor. The carbon price support (CPS) mechanism began at GBP 9 per tonne of CO2 emissions in 2013 and increased annually to GBP 15 in 2015, targeting EUR 30/tCO2 by 2020. In 2018, the effective carbon rate reached GBP 36/tCO2 and the additional cost from the support mechanism was capped at GBP 18/tCO2 until 2021.

Emissions in the electricity sector fell by 58% from 2012 (before the CPS was introduced) to 2016 (the first full year for which total effective carbon rates were about EUR 30). In 2018, they had fallen by 73% as compared to 2012 levels. The UK Treasury further recouped GBP 1 trillion in CPF tax receipts in 2017, although this is likely to fall as the ETS price increases and the UK decarbonises. Tax receipts go the general budget.

Irish non-ETS sector carbon tax

Ireland introduced a carbon tax on liquid and non-gaseous fuels in non-ETS sectors in 2010 and extended it to solid fuels in 2013. The tax rate increases over time, reaching EUR 26/tCO2 in 2020 and targeting EUR 100/tCO2 by 2030. The increase of the nominal carbon tax rate between 2018 and 2020 resulted in a nearly 5% rise in the effective carbon tax rate in the transport sector and a 35% increase in the non-transport sector. Moreover, due to the carbon tax, Ireland is among ten OECD countries to price at least half of their energy-related CO2 emissions at EUR 60/tCO2 (a low to midpoint estimate for the social cost of carbon in 2020 (High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices, 2017[28])).

The Irish carbon tax includes a commitment to using the generated revenues to prevent fuel poverty, ensure a just-transition, and finance climate projects. According to the National Development Plan, the tax is expected to yield EUR 9.5 billion over the coming decade. The plan aims to invest half of this in energy efficiency renovations, with a further EUR 1.5 billion to be invested in climate mitigation activities and EUR 3 million on initiatives to limit fuel poverty and ensure a just transition. These include enhancing social welfare schemes, providing support to vulnerable households and retraining workers. As such, the tax contributes to reducing poverty, as average weekly disposable income of households would increase as a result of the budget package.

Danish policy mix approach

Denmark takes a particularly comprehensive approach to climate policy. A climate law adopted in 2020 sets a long-term target of net-zero emissions by 2050, with an intermediate target of a 70% reduction by 2030. To reach these targets, it implements a three-pronged policy mix. First it sets ambitious emissions prices consisting of a CO2 tax on transport and heating fuels, excise taxes, and the EU ETS. It backs up these pricing mechanisms with regulatory measures such as a ban on new fossil fuel explorations and aiming to cease fossil fuel production from 2050, and banning fossil fuel powered cars from 2035. Finally, these policies are supported by investments into infrastructure and research and development through the Danish Green Investment Fund. The policy process further includes strong stakeholder involvement, targeted policies to attract private investment, and a framework for labour reallocation in order to mitigate possible adverse transitional effects.

Note: The examples presented were not assessed as to their comparability with the Lithuanian case. However, as these are broad economy-wide policies they are applicable in all cases, though their design should consider specific local contexts.

Transport

The NCCMA sets an overarching emissions reduction target for the transport sector of 14% by 2030 (compared to 2005 levels). This amounts to a 42% reduction from 2019 levels, when the NECP was formally adopted. As such, decarbonising the transport sector is amongst the most challenging areas of Lithuania’s climate policies.

To meet this overarching target, the NCCMA’s objectives for the transport sector are:

to achieve, by 2030, a 50% share of electric and other low-emissions vehicles in annual vehicle purchases, and to reduce the number of cars powered by conventional fuels in cities by 50%;

to reduce, by 2030, the use of fossil fuels in passenger cars by 40%;

to increase the share of renewable energy used in the transport sector to 15% in 2030, and 100% in 2050;

to increase the share of second-generation biofuels in total fuel consumption in the transport sector to 3.5% by 2030.

As the primary document detailing Lithuania’s climate policies, the NECP presents a broad policy mix for transport. This includes measures to renew the public transit fleet, electrify railways, promote sustainable mobility behaviour, reduce the number of polluting vehicles, and incentivise the use of zero‑emissions alternatives. It also includes measures promoting the use of renewable energy sources in transport, reducing congestion, and reducing emissions from freight transport and shipping.

The following subsections take stock of these policies, detailing measures currently being implemented as well as planned additional measures, with a view to assessing their adequacy to meet the NCCMA’s updated targets. Good-practice examples from other OECD countries for further policy reforms in the transport sector are also provided.

Existing policies

Economic measures

Existing economic measures implemented in the transport sector encompass a wide range of activities. For example, since 2017, urban centres and municipalities have been eligible for funding to purchase buses or similar public transport vehicles powered by electricity or alternative fuels. Further measures to promote fleet renewal are planned. Economic measures also include funding for the electrification of rail transport, with 391.6 km of railway lines to be electrified by 2023, primarily from Kaišiadorys to Klaipėda and including the Vilnius junction and Kena-N. Vilnia line. Further electrification of railways is also planned.

Key economic measures making up the bulk of available funds focus on the transition from polluting to low-emissions vehicles, for example policies aiming to reduce the number of polluting vehicles, and to incentivise the purchase and/or deployment of low-emissions alternatives.

To reduce the number of polluting vehicles, a “cash for clunkers” policy grants lump-sum payments to private vehicle owners willing to replace their polluting car with a new low-emissions vehicle. Under this scheme, vehicle owners can receive up to EUR 1 000 for their old car, with poorer households receiving up to EUR 2 000. Payments are also available for those willing to switch mobility types, for example to public transport, bicycles or electric scooters, or ride-sharing services.

Policies to incentivise the use of low- or zero-emissions vehicles include purchase subsidies for various types of electric vehicles (starting at EUR 4 000 for a new private electric vehicle and EUR 2 000 for a used one).1 They also include subsidies for the installation of private charging stations, financing for the installation of public charging stations, and obligations to install charging stations in new buildings or parking lots and petrol stations. The aim is to install 54 000 private and 6 000 public charging stations by 2030. Lithuania also provides investment support for the installation of biomethane production plants with the intent of reaching a capacity of 950 GWh of biomethane produced per year by 2030.

Finally, municipalities have prepared sustainable urban mobility plans (SUMPs) detailing how they intend to promote walking, cycling, public transport and the use of alternative fuels. Municipalities can apply for funding from different sources including a national sustainable mobility fund (currently being established) and EU Structural and Investment Funds (available for SUMPs since 2016).

Fiscal measures

A number of fiscal measures have been implemented in the transport sector. These include differentiating the private vehicle registration tax by pollution level, with the aim of reducing emissions from private vehicles by 3.5% annually, and phasing out tax exemptions for self-employed persons.

Beyond private vehicles, freight transport is also being targeted through the introduction of e‑tolling and shifting to a higher Euro emissions standard. These measures were introduced between 2019 and 2021 following the adoption of the NECP.

Finally, to promote the use of renewable energy sources in the transport sector, biofuels are exempt from excise duties, with the exemption for blended fuel proportional to the fuel mixture.

Regulatory measures

Existing regulatory measures primarily comprise renewable energy obligations. For example, biofuel blending obligations in accordance with EU standards have been in place since 2011 and were updated in 2021. Advanced biofuels are also being promoted, targeting a 1.75% share of total fuel consumption by 2030. Additionally, natural gas operators are obliged to meet targeted shares of renewable energy of 4.2% by 2025 and 16.8% by 2030.

Complementary measures

To promote sustainable mobility in Lithuania, a study is currently underway to assess options for optimising public transport in the Vilnius area. In order to reduce congestion, traffic management measures were introduced in 2021. These include, for example, planning traffic distribution and restrictions during peak hours and introducing intelligent management technologies such as traffic lights or road crossings. Educational measures are also being implemented, for example informing persons on the climate benefits of teleworking (reducing congestion and fuel consumption).

Planned measures

Economic measures

In addition to the already existing purchase subsidies for transport fleet renewal, further economic measures are planned. These include purchase of electric and hydrogen buses, and the installation of hydrogen and electricity recharging infrastructure using European Regional Development Funds (ERDF). Plans for the purchase of electric buses and the installation of charging stations already exist at the municipal level, with 2030 targets, but are pending approval of funds from the ERDF. With hydrogen technologies at a more nascent stage, plans for procuring hydrogen buses and installing hydrogen refuelling stations remain preliminary. The NECP provides for the possibility of investments into this technology in the future.

Purchase subsidies are further planned for the business and public sector, targeting over 20 000 passenger vehicles, 500 heavy-duty vehicles (of which 200 should be electric or hydrogen and 300 powered by biofuels), 450 electric/hydrogen buses and 50 biofuel buses, as well as support for the production of electric vehicles. Further financial support is planned for the purchase of public, utility, or other commercial vehicles powered by compressed natural and/or biomethane gas, and for the production of second-generation biofuels.

In addition to the rail lines currently being electrified (see previous section), a further 814 km are to be electrified by 2030, with over 70% of goods to be transported by train. This includes the regional Rail Baltica plans that will enable electrified train transport throughout the Baltic states. Freight transport is further targeted through economic measures promoting emissions reductions through shipping. These include financial incentives for the use of combined freight and financial support for the construction of new ships and barges.

Fiscal measures

A key fiscal measure planned for the transport sector was the introduction of an annual vehicle tax based on vehicles emissions standards. This tax was to be implemented from 2023 but has recently been rejected by parliament. Although it has been recommended for resubmission, this is subject to reforms, and the current administration has shifted its focus to passing economy-wide excise tax amendments instead. Planned fiscal measures for the transport sector also include creating a favourable tax environment for the development of inland waterway transport.

Regulatory measures

Accompanying plans for new economic and fiscal measures, the NECP’s planned policies also include new regulations requiring the labelling of vehicles according to their pollution standard. New legislation is also planned on green procurement, setting minimum procurement targets with the goal of reaching 100% clean passenger cars by 2030. The NECP further outlines plans to introduce low-emissions zones restricting access for polluting vehicles within urban centres throughout Lithuania, and periodically expanding them over time.

Complementary measures

Educational programmes include trainings, advertisements, and promotion of sustainable mobility throughout society, from kindergarten to private companies.

Assessment and recommendations

The NECP sets policies for the period 2021-2030. Many of these policies are now being implemented, including for example generous economic incentives for fleet renewal and the purchase of low-emissions vehicles. What is more, planned amendments to excise duties will, if implemented, have a significant impact on emissions reductions in the transport sector, marking important steps towards increasing taxes on polluting behaviours that have been identified as key obstacles to climate action in Lithuania (OECD, 2021[7]). For a more detailed analysis of the effect of this amendment see Chapter 4.

The planned vehicle tax is a further measure that, if implemented, would have a significant impact on emissions in the transport sector. The Danish example shows that vehicle taxes can be an effective climate policy tool for the transport sector, as they reduce overall demand for private passenger vehicles and incentivise a shift to low-emissions vehicles through a CO2 component (Box 2.3). Regrettably, the vehicle tax proposal was recently rejected by parliament. Although subject to a resubmission, it is unlikely that the excise duty amendment and vehicle tax will be implemented simultaneously, particularly in light of the current energy crisis.

Establishing a domestic ETS for transport (and heating), as was done in Germany, would further strengthen the climate policy response for transport (Box 2.3). Such an ETS could also serve as a transition policy should an EU-wide ETS II be adopted, helping to ease possible price shocks and develop domestic capacity (see Chapters 3 and 4 for more detail).

The existing and planned policies detailed in the Lithuania’s NECP focus primarily on fleet renewal. These policies are expensive to uphold, however, and may not be enough to reduce emissions. More systematic approaches are needed, for example addressing urban sprawl and overall time spent in transit (Box 2.2). Here, urban planning regulations and road pricing could be ratcheted up, for example through the introduction of area charges (Box 2.3).

Finally, tax base erosion will become a significant issue, with ample support provided to EVs becoming increasingly difficult to finance as fuel tax revenue decreases during the transition (see Norwegian example in Box 2.3). Overcoming this requires a longer-term perspective, for example through the gradual introduction of a distance tax as electric vehicles become more widely deployed.

Box 2.2. Redesigning transport systems for well-being

To design comprehensive decarbonisation strategies for urban transport it is key to consider urban transportation as a socio-economic system. A 2021 OECD report, Transport Strategies for Net‑Zero Systems by Design, highlights the limitation of addressing only individual components of existing urban transport systems, systems that by design are unsustainable. Current transportation systems are focused on private passenger vehicles, aiming to maximise individuals’ mobility. This has come at the expense of proximity, driving urban sprawl, demand for private vehicles, and reduced use of shared and active modes of transport. The report suggests that focusing on individual components within this system, i.e. replacing internal combustion engines with electric vehicles, does little to address the unsustainable design of the system itself. As a result, urban sprawl and reduced shared or active modes of transportation will further increase demand for private vehicles, obstructing mitigation efforts.

Overcoming such design problems requires taking a systemic approach. The report suggests that the aim of transportation is to provide individuals access to places; rather than maximising individual mobility, transportation systems should focus on accessibility, which combines mobility with proximity. With this in mind, transportation policy should focus not on replacing individual components within the existing system (i.e. polluting vehicles), but on street redesign, spatial planning, and increasing shared modes of transportation. This in turn will reduce demand for private passenger vehicles, reducing emissions and making it easier to renew and replace the remaining vehicle fleet.

Source: (OECD, 2021[32]).

Box 2.3. Good climate policy practice in the transport sector

German ETS for transport

The German Climate Action Act agreed upon in 2019 includes the introduction of a carbon pricing mechanism for transport and heating. The emissions trading scheme at first follows a fixed price trajectory, starting at 25 EUR/tCO2 in 2021, and increases annually to 55 EUR/tCO2 in 2025. Following this initial phase, a price corridor will be implemented for a year (2026) keeping the price between 55 and 65 EUR/tCO2. Whether this corridor should then be shut (moving to an entirely market-driven price) will be decided in 2025.

The revenue generated by the scheme is to be used to reduce the current renewable energy surcharge on electricity prices and provide additional income relief for commuters disproportionately affected by the ETS.

Emission-intensive industries will be compensated in order to safeguard competition and avoid carbon leakage, but under the condition that compensation payments are invested in energy efficiency. Biofuels are exempt so long as they comply with EU sustainability criteria.

Danish vehicle tax

The Danish vehicle tax has played an important role in reducing emissions in the transport sector. Under the tax, all cars pay a registration fee based on the value of the car. EVs and low-emissions vehicles receive a deduction based on their battery capacity plus a basic deduction. In addition to this, a CO2 surcharge based on emissions per kilometre applies to all vehicles.

EV support in Norway

Norway has been very successful in incentivising the uptake of electric vehicles. Extensive tax exemptions, exemptions from congestion charges and the ability of electric vehicles to use bus lanes, as well as support for charging infrastructure, have resulted in the electric vehicle fleet rising to 340 000 vehicles by 2020, representing 16% of total global sales.

Area charges in Stockholm

Stockholm was the second city in Europe (after London) to introduce an area charge with the aim of reducing congestion. The charge changes based on the time of day vehicles enter the area. It had a strong immediate effect on traffic levels and has retained this effect over the long term. It also generates important revenues that can be reinvested into public transportation.

Biofuel support/performance standards in Brazil

Brazil’s RenovaBio programme is a good example of how tradable performance standards can be used to reduce GHG emissions through biofuels. The programme sets a GHG emission reduction target for the transport sector of 10% by 2028, and breaks this down into mandatory annual reduction targets for fuel distributors. It then certifies biofuel production relative to the carbon intensity of the biofuel produced. The certificates (equivalent to 1 tonne of CO2 avoided and linked to sustainability criteria) can then be traded, with fuel distributors required to meet their emissions reduction targets through purchase of certificates.

Energy

The NCCMA sets overarching targets for emissions reductions in the energy sector. It differentiates between installations covered by EU ETS and non-ETS sectors, targeting a 50% emissions reduction in ETS sectors and a 25% reduction in non-ETS sectors by 2030 (compared to 2005 levels). It provides more detail on sectoral objectives for energy and industry sector installations covered by the EU ETS. Specifically it targets:

45% renewable energy in total final energy consumption and 50% renewable energy in electricity consumption by 2030, increasing to 75% and 95% respectively by 2040, and 90% and 100% respectively by 2050;

district heating (90% renewable energy by 2030), energy savings (27 TWh final energy savings, including in the industry sector, by 2030) and energy efficiency (reduce primary and final energy consumption by half by 2040 compared to 2017, and by a factor of 2.5 by 2050).

The NCCMA further provides subsectoral objectives for non-ETS sectors, primarily in the buildings sector. Here it targets an increase in energy efficiency, and a switch to non-polluting heat and cooling technologies by prioritising the use of renewable energy sources by 2030. Specifically it aims to:

save at least 6 TWh of energy consumption through comprehensive renovation efforts in individual houses and public buildings by 2030;

enable 30% of households to become active electricity-generating consumers (prosumers) by promoting decentralised electricity generation and storage;

advise end users on energy saving measures and solutions, targeting behavioural or demand-side measures;

increase the number of households connected to district heating by promoting efficient use of thermal energy.

Together these goals serve to transform the current buildings subsector so that by 2050 it is independent from fossil fuels and energy efficient, striving for nearly zero-emissions buildings2 and reducing annual energy consumption by 60% compared with 2020 levels, with the share of renovated buildings to reach 74%. The use of primary energy from fossil fuels and GHG emissions will be entirely phased out.

For the energy sector, the NECP details policies in three primary sub-categories: energy efficiency, heat and electricity. The following subsections take stock of these policies, detailing measures currently being implemented as well as planned additional measures, with a view to assessing their adequacy in meeting the NCCMA’s updated targets.

Existing policies

Economic measures

Existing economic measures for energy efficiency include various financial incentives and support mechanisms. Financial incentives are in place for individual homeowners to carry out energy efficiency renovations with the aim of renovating 1 000 homes annually, saving 13.5 GWh. The measure also includes support for the modernisation of heating and hot water supply in multi-apartment blocks. Support also exists for energy efficiency renovations of multi-apartment blocks, with the intent to upgrade them to class C buildings, enabling up to 40% energy savings. The measure targets the renovation of 5 000 blocks by 2030. In addition to state finance for renovations, apartment building owners will receive monthly credits or interest payments differentiated between the heating and cooling seasons. A financial mechanism further encourages building owners to upgrade old elevator-type heating points to new single-circuit units. The measure compensates up to 30% of the cost for this retrofit and aims to renew 250 heating points annually, saving 10 GWh a year.

Beyond buildings, financial support also exists for the modernisation of street lighting with the goal of replacing 25% of all lights by 2030, saving 250 KWh annually. Private enterprises can also receive financial support for implementing energy efficiency measures identified in mandated energy audits, projected to save almost 5.5 TWh by 2030.

In the electricity subsector, multiple policies support the deployment of renewable energy sources. These include a feed-in tariff that supplements the price of electricity generated by renewable energy sources. The measure also prioritises transmission of electricity from renewable sources, and exempts electricity generators from being liable for balancing the electricity produced and from reserving capacity during the promotion period.

Offshore wind generation in the Baltic Sea is supported through a tender-based auction process. The winner of the tender process must obtain a construction permit within three years and begin producing electricity six years from receipt of the permit. An offshore substation will be built to connect the planned wind farm to the transmission network. Electricity production is planned to begin in 2028, adding a renewable energy capacity of 350 to 1 400 MW.

Beyond supporting larger-scale renewable energy production, financial support through EU funds and the national Climate Change Programme is available for the deployment of renewable energy in public sector and residential buildings. The measures aim to install a further 50 MW of renewable energy capacity and by 2030 enable 30% of all energy consumers to generate their own electricity through renewable installations (prosumption). Support is also provided for the installation of small renewable energy plants in communities. This support will be provided through a tender process, using revenues generated by agreements on statistical energy transfer between Lithuania and other European countries.

Supporting the deployment of renewable energy sources, new substations are being built and new technologies deployed to enable the integration of renewable energy into the transmission network. The total expected increase in renewable energy generation from 2021-2030 is 1 944.5 MW.

Finally, there are measures in place to support co-generation plants, targeting an additional capacity of 0.4 TWh annually from 2023. For example, a co-generation plant in Vilnius was granted EUR 190 million in 2016. The plant uses municipal waste unsuitable for recycling as well as biofuels and will generate 0.3 TWh annually. Similar projects are also being supported in other areas.

Financial support is also being provided for heat generation measures, for example installation of low‑capacity biofuel co-generation plants. Old coal and gas heating supply will be converted to renewable sources, with biofuels providing 70 MW of additional capacity by 2030, and solar, heat pumps and geothermal 200 MW. Support is also being provided for the conversion of boilers to more efficient alternatives, with 50 000 boilers to be replaced by 2030. The measure compensates up to 50% of the costs of conversion for households not connected to district heating.

In order to support these efforts to reduce emissions in the heat sector, the heat transmission network is being modernised, with 42% of pipelines replaced by 2020. Finally, measures exist to promote the use of waste heat generated by industry in district heating networks.

Regulatory measures

Existing regulatory measures for energy efficiency include the Energy Efficiency Act, which legislates that energy suppliers must enter into agreements with the Ministry of Energy, mandating energy savings. The agreements should include the energy savings level or GHG emissions reductions as well as information on energy efficiency improvements. This measure is expected to save around 100 GWh annually by 2030.

In the heat subsector, new regulation enables heat suppliers to raise funds for modernisation. New regulations also exempt natural gas suppliers that already pay for the security component from the requirement to build up reserve fuel stock. Finally, regulations are in place dictating that, by 2027, all heat meters must be replaced by remote scanning, thereby modernising the heat accounting system.

Complementary measures

To promote behavioural changes in energy efficiency and savings, energy suppliers must enter into agreements with the Ministry of Environment, detailing education measures to promote energy efficiency and saving. The measure is expected to enable 3 TWh of savings.

Several studies are also being carried out to assess the potential for further decarbonisation in the heat sector. These include assessments of the legislation necessary for a favourable regulatory environment for sustainable district heating, a review of the reserve requirements for heat production capacity and fuel reserves, and an assessment of the potential for renewable energy sources for cooling. Finally, an inventory of the energy efficiency of household appliances has been collected to inform climate policy measures.

Planned policies

All of the planned policies detailed in the NECP for the energy sector are currently being implemented.

Assessment and recommendations

The extensive economic support provided for energy efficiency, renewable electricity production and heat are important measures enabling considerable emissions reductions in the energy sector. In particular, the generous support programmes available for renewable energy sources and accompanying measures on systems integration and investments into grid connections will greatly increase the supply of renewable energy in Lithuania. This will further increase energy independence, a key priority. Coupled with the planned economy-wide excise duty amendment, these measures will put considerable pressure on energy suppliers to switch to sustainable alternatives, incentivising decarbonisation efforts.

The progress made to shift heat-supply from natural gas to bioenergy is already a significant step towards decarbonising the heat subsector. Reliance on bioenergy, however, needs to be coupled with strict sustainability criteria. Less-expensive Belarusian imports have undermined the sustainability of supply in the Baltpool platform. Co-generation capacity will be key to ensuring the stability of power supply, and current plans emphasise the further expansion of bioenergy to enable this. Here, EU regulations on bioenergy sustainability must be upheld. Moreover, reforms to the EU’s renewable energy directive proposed in the Fit for 55 package would see a phase-out of bioenergy from electricity production by 2026. Considering this, and given sustainability concerns, Lithuania’s economy-wide plan to phase out biofuel tax exemptions is a highly important policy that will ensure sustainable energy supply in the long term (for a more detailed analysis of emissions pricing for biofuels see Chapter 4).

Finally, renovation targets in Lithuania have not been met in the past. Inefficient heat consumption remains a serious problem, despite the high share of renewable energy sources in heat supply. To tackle energy efficiency deficits, a “fabric first” policy, as suggested at the EU level and implemented in Ireland, would ensure that the gains from fuel switching are not lost due to insufficient building standards.

Box 2.4. Good climate policy practices in the energy sector

Germany: ETS for heat

The German Climate Action Plan agreed upon in 2019 includes the introduction of a carbon pricing mechanism for transport and heating. The emissions trading scheme at first follows a fixed price trajectory, starting at 25 EUR/tCO2 in 2021, and increasing annually to 55 EUR/tCO2 in 2025. Following this initial phase, a price corridor will be implemented for a year (2026) keeping the price between 55 and 65 EUR/tCO2. Whether this corridor should then be shut (moving to an entirely market driven price) will be decided in 2025.

The revenue generated by the scheme is to be used to reduce the current renewable energy surcharge on electricity prices and also to provide additional income relief for commuters disproportionately affected by the ETS.

Emissions-intensive industries will be compensated to safeguard competition and avoid carbon leakage, but under the condition that compensation payments are invested into energy efficiency. Biofuels are exempt so long as they comply with EU sustainability criteria.

For a more detailed analysis of the impact of an ETS for heat on the Lithuanian buildings sector see Chapters 3 and 4.

Denmark: offshore wind tenders

Denmark has very successfully scaled up its renewable energy generation. An electricity tax provides funding for extensive feed-in tariffs for renewable energy sources except for offshore wind which is supported through a tender process. The offshore wind tenders guarantee electricity offtake and grid connections and provide a one-stop shop for permitting and licensing, minimising administrative costs. The plummeting price of offshore wind generation has recently resulted in a contract for differences scheme providing “negative subsidies”. The scheme guarantees the winners of each tender a minimum price. If the wholesale price rises above this, the operator pays back the difference to the government.

Ireland: fabric first principle

Ireland has implemented a fabric first guiding principle. Under this principle, renovation plans or policies must consider energy efficiency first, ensuring that the benefits of a subsequent switch to sustainable energy sources are not compromised by insufficient building standards. Regulation mandates that all new buildings meet near-zero energy standards, increasing their energy performance by 25%, with help also provided for phasing out gas and oil boilers in new housing construction. Major renovations (more than 25% of the floor space) are also required to meet minimum efficiency standards. Finally, as part of the “better energy communities” programme, the fabric first principle requires that energy efficiency investments be made before other grants can be approved.

Industry

The NCCMA sets overarching emissions reduction targets for the industry sector, differentiating between installations covered by the EU ETS and those that are not. EU ETS installations are to reduce emissions by 50% by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels) and by 100% by 2050. For non-ETS installations, the NCCMA sets an emissions reduction target of 19% by 2030 (compared with 2005 levels).

The NCCMA further defines sectoral objectives such as a focus on the circular-/bioeconomy, reducing fluorinated greenhouse gases by 79% by 2030, enabling energy savings of 5.45 TWh in industries by 2030, and to generally deploy renewable energy sources wherever possible.

Multiple policies are detailed in the NECP addressing the industry sector concerning both the non-ETS sectors and ETS sectors. The measures detailed cover a number of issue areas, from the introduction of new technologies to the promotion of non-technological eco-innovation. The following subsections will take stock of these policies, detailing measures currently being implemented as well as planned additional measures with a view to assessing their adequacy in meeting the NCCMA’s updated targets, and providing good-practice examples from other OECD countries for further policy reforms in the industry sector. The measures depicted are grouped by the type of measure, namely whether they are economic measures (subsidies, lump-sum payments, etc.), fiscal measures (taxes or tax-exemptions), regulatory measures, or complementary measures such as education or research and development (D’Arcangelo et al., 2022[8]). The NECP only details economic and complementary measures for the industry sector.

Existing measures

Economic measures

Existing economic measures for the industry sector promote the use of modern technologies, non‑technological solutions, digitalisation, and energy efficiency. Economic support is provided to industrial companies for implementing energy efficiency measures following an energy efficiency audit, with the aim of saving 100 GW of energy a year from 2030.3 Financial support is also provided for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups or innovative businesses for applying new technologies for sustainability. The measure aims to modernise Lithuanian industry as well as incentivising innovation.

In addition to financial support for the energy efficiency measures and the use of modern technologies, targeted support for the deployment of renewable energy is also available. This includes both support for installing renewable energy production capacities, and for carrying out energy audits in industrial enterprises. For example, a measure provides financial assistance for ETS installations to switch from conventional fossil fuels to alternative fuels. The measure targets a 90% reduction in the use of conventional fuels. Support is also provided to the implementation and promotion of technological eco‑innovation, with specific funds available for micro-, small- and medium-enterprises for measures such preventing pollution through technological modernisation, or reducing resource use through recycling, and further support offered to all companies for introducing environmentally friendly innovations.

Support is also provided for the application of non-technological solutions. This measure supports companies in finding innovative means to increase the attractiveness of products and services. The measure also aims to share knowledge on non-technological solutions such as resource efficiency, conservation of natural resources, eco-innovation and the like, financing expert advice in particular for SMEs.

A further measure promotes digitalisation in the industry sector, in particular micro-enterprises and SMEs. The measure offers financial instruments for technological audits, the results of which allow these enterprises to better assess the possibilities and prospects for digitalisation. The measure aims to accelerate the digitalisation process and increase productivity. Finally, companies can receive compensation for the implementation of energy efficiency measures, targeting annual savings of 100 GWh annually by 2030.

Fiscal measures

Existing fiscal measure for the industry sector comprise of tax incentives, provided to small enterprises and start-ups in order to promote innovation. These include a one year “tax-holiday”, the ability to deduct research and development costs from corporate income tax, and a preferential tax rate for the commercialisation of new technologies.

Regulatory measures

Existing regulatory measures in the industry sector focus specifically on the reduction of emission of fluorinated gases such as HFCs under the EU F-gases regulation (EU) No 517/2014. This comprises implementing the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol as well as further measures aiming to reduce the fluorinated gas emissions by two-thirds by 2030 (compared to 2014 levels), for example through banning the use of new equipment with high HFCs content.

Planned measures

Economic measures

There are a number of planned measures for the industry sector, both for installations covered by the ETS and those not. These measures provide financial support for replacing polluting technologies or fuels with more sustainable alternatives. Further planned measures support investments in tangible assets such as equipment with a lower environmental impact, investments in the innovation of cleaner production processes, the use of excess heat for energy production/heating, investments in materials and installation work with a lower environmental impact, and the improvement of products and services. This also includes support for the development and deployment of innovative digital and environmentally friendly technologies by SMEs, with priority given to circular products and production. Financial support is also available for companies to invest in product and service design solutions, for example for projects developing innovative packaging designs.

A number of planned measures aim to promote further digitalisation. Investment support will be provided to companies in the deployment of automated production processes. This includes support for technological audits. EU funding is also available for the establishment of European Innovation Hubs to encourage the development of digital competencies in areas such as high-performance computing and artificial intelligence.

Further planned measures target energy efficiency. For example, providing financial support to SMEs wishing to carry out technological audits for energy efficiency. There are also plans to subsidise energy efficiency in the ETS sectors, encouraging investments into the digitalisation, modernisation, optimisation, and automation of production processes in large and medium-sized manufacturing operations. Subsidies are also planned for the uptake of renewable energy sources in ETS installations as well as for SMEs not covered by the EU ETS.

Complementary measures

Two studies are planned in order to support decarbonisation efforts in the industry sector. First, an industry 4.0 lab will enable joint research and innovation in the areas of smart specialisation. The lab will be funded by European Innovation Hubs. Second, a feasibility study is planned, assessing the potential for the application of nascent technologies such as carbon capture and storage or hydrogen in Lithuania.

Assessment and recommendations

Existing and planned measures in the industry sector provide important incentives for decarbonisation. Modernising technologies and processes, and providing support for non-technological solutions, particularly in SMEs not covered by the ETS are important means to promote sustainability. In addition, the planned amendment to economy-wide excise duties will significantly increase the pressure to shift away from polluting fuels. However, the exemption of natural gas from this planned policy will significantly compromise potential emissions reductions in the industry sector (for more information see Chapters 3 and 4). Industry accounts for most of the natural gas use in Lithuania, and without price increases, few incentives exist to reduce the use of natural gas in the non-ETS sectors.

The price signal from the EU ETS could also be further strengthened through the introduction of a price floor, providing a transparent signal to investors and enterprises. Coupling such a price-floor with innovation support, as is the case in the Netherlands, would encourage research and development into solutions in hard-to-abate sectors (Box 2.5). Innovation support could be increased in Lithuania, focusing on providing funding for pilot projects that enhance knowledge accumulation and have potentially large knock-on effects (for an example of a similar scheme in Norway see Box 2.4). For a more detailed analysis of carbon pricing in the industry sector see Chapter 4.

Box 2.5. Good climate policy practices in the industry sector

Carbon pricing and innovation support in the Netherlands

In 2021, the Netherlands introduced a carbon price floor for the industry sector that complements the EU ETS price. The price floor started at 30 EUR/tCO2, increasing annually to 125 EUR/tCO2 in 2030. Enterprises pay a floating contribution on top of the EU ETS price in order to meet the price floor. If EU ETS prices rise above the annual floor price this contribution is zero.

In addition to the carbon price floor, a generous subsidy scheme provides investment support for innovation through public tenders based on technologies abatement costs. Such a two-pronged approach, combining strong price signals with generous innovation subsidies, ensures that decarbonisation efforts are not compromised by a lack of technological solutions in hard-to-abate sectors. Nonetheless, basing innovation support on abatement costs risks disadvantaging more radical ideas that are not yet cost-effective (e.g. green hydrogen).

Innovation support through state-owned enterprises in Norway

ENOVA in Norway is a state-owned enterprise that supports research and development for sustainability, providing investment aid and conditional loans. For example, ENOVA provided around 1/3 of the funding for a pilot aluminium plant validating new technological elements and control systems for more energy and climate efficient aluminium production. Supporting such a pilot project may lead to further innovations, having potentially important knock-on effects.

Agriculture and forestry (LULUCF)

The NCCMA sets an overarching emissions reduction target for the agriculture sector of 11% by 2030. It further targets an increase in the absorption capacity through the LULUCF sector, amounting to 6.5 million tCO2e between 2021 and 2030. In order to achieve this, the NCCMA sets a number of sectoral objectives.

In the agriculture sector, the NCCMA targets a reduction in nitrogen-based fertiliser use by 15% compared with 2020 levels. It further proposes to, by 2030, increase sustainable management of manure and slurry to at least 70% of total stock, double the area of organic farming compared to 2020 levels, and to use 50% of pig and cattle manure for biofuels.

In the LULUCF sector, the NCCMA targets a 35% increase in forested area by 2024, increasing grassland areas by 8 000 ha and to use at least 10% of agricultural areas for biodiversity rich landscapes by 2030. It further proposes the restoration of 8 000 ha of wetlands by 2024, and to stop new wetland drainage and development. Finally, the NCCMA promotes sustainable resource management and consumption patterns, as well as other behavioural measures.

The NECP sets a number of climate policy measures, both for the agriculture and LULUCF sectors. The following subsections will take stock of these policies, detailing measures currently being implemented as well as planned additional measures with a view to assessing their adequacy in meeting the NCCMA’s updated targets and providing good-practice examples from other OECD countries for further policy reforms in the agriculture and forestry sectors. The measures depicted are grouped by the type of measure, namely whether they are economic measures (subsidies, lump-sum payments, etc.), fiscal measures (taxes or tax-exemptions), regulatory measures, or complementary measures such as education or research and development (D’Arcangelo et al., 2022[8]).

Existing policies4

Economic measures

The NECP details a number of economic measures supporting an increase in the absorptive capacity of the LULUCF sector. Financial support is provided for the restoration of forest areas, with the aim of introducing or preserving 8 000 ha of new or existing forests annually. Funding is also available, promoting the farming of catch crops, providing 139 EUR/ha and aiming to cover almost 75 000 ha by 2027. This funding is part of the rural development plan submitted to the EU. Funding is also available through the Recovery and Resilience Facility for the restoration of peatlands, targeting 8 000 ha restored by 2026. Finally, funding is available for the restoration of stands and shrubs, although this measure is to be discontinued due to low demand.

In the agriculture sector, one-off compensation is provided for the establishment of long-term climate commitments, such as reducing the area not using mineral nitrogen fertilisers. The measure is a priority area under the EU’s common agricultural policy (CAP). Investment support is also available for implementing climate friendly livestock farming methods such as the use of manure for biogas production, and slurry as fertiliser.

Support is also available through the EU Modernization Fund for the use of non-till technologies, for example for the purchase of direct and belt seed drills. A further measure promotes the farming of perennial crops, targeting the conversion of 8 000 ha of plows into meadows by 2030. Funding is also available for promoting the optimisation of meadows and pastures by extending livestock grazing, reducing manure production in barns. Finally one-off compensation schemes under the CAP provide funding for experimental short-term climate commitments, such as the cultivation of plans using non-destructive technologies.

Fiscal measures

In the agriculture sector, the air-pollution tax for the livestock and poultry subsectors was increased, and preferential excise taxes for agricultural fuels decreased.

Regulatory measures

No regulatory measures have been implemented in the agriculture and forestry sectors.

Complementary measures

A regional project implemented by partners in Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Finland and Germany, establishes national indicators for changes in GHG emissions/carbon stock. These indicators demonstrate the potential for integrated GHG reductions and carbon sequestration in soil management programmes. The project also establishes a network for monitoring and evaluation of climate policy measures and for science-based land-use policy making and climate policy planning.

In the agriculture sector, measures provide education for farmers on good agricultural practices, disseminating knowledge and advice on environmentally friendly activities, and technological and operational solutions for GHG reductions. CAP funded measures further promote sustainable farming practices, such as a reduction in the use of mineral fertilisers, or soil-saving techniques and technologies. Finally, there is a measure in place promoting sustainable livestock and fishing practices with a priority focus on the dairy sector.

Planned policies

Economic measures

A number of economic policies are planned in the LULUCF sector. These include promoting the use of deforestation residues as woody biofuel mass. Reimbursement is also available for the costs of entering overgrown areas as forests into the national forest database, although future changes in the conditions for registering forest areas are likely to change. Funding is also available for replacing eroded land with meadows, increasing green cover on agricultural lands and for planting landscape elements on the edge of cultivated fields.

Fiscal measures

As part of the economy-wide amendment to excise duties, excise duty exemptions for the agriculture sector are to be reduced with the introduction of stricter tariffs on fuel use, and the introduction of quotas for excise exemptions.

Regulatory measures

Planned regulatory measures in the agriculture and forestry sector include the establishment of additional environmental criteria for public procurements, particularly promoting the use of timber and timber products in the construction sector. Finally, regulations will limit the use of mineral fertilisers, with an obligation on farms to provide data on fertiliser use. Following the development of a national methodology on fertiliser use, farms will be required to submit periodic plans on how to implement this.

Complementary measures