This chapter looks at the interface between the national and both the sub-national and European level in the Slovak Republic. It explains the organisation of regulatory attributions and the oversight mechanisms in place for regulation at the subnational level and points to challenges and opportunities for regulatory policy in Slovakia’s municipalities, counties and cities. The chapter also describes and evaluates the processes in place for negotiating the national position, transposing EU directives into national law and ensuring consistency with national legislation in the Slovak Republic. Finally, it gives recommendations for improvement of the multilevel regulatory governance set-up.

Regulatory Policy in the Slovak Republic

8. Multilevel governance

Abstract

The importance of sub-national regulatory policy

In many OECD countries, subnational governments (states, provinces, or even municipal governments) have strong regulatory powers. Many subnational governments make regulations in areas critical to the safety and well-being of citizens, often including health, road safety, and the environment. For example, seventy-six percent of energy-related greenhouse gas emissions come from cities and permits for clean energy facilities often involve compliance with local permitting ordinances. Also, local and governments are often responsible for providing regulatory services, such as handling the administration for starting a new business as well as compliance and enforcement (e.g. policing, work safety inspections).

This multi-level nature of regulation can cause severe economic friction. According to a report from the Conseil d’État in France (Marcou and Musa, 2017[1]), the decentralisation of regulatory powers makes citizens and businesses have to navigate multiple levels of red tape. Worse yet, uncoordinated regulation can create overlap or even conflicts that make it impossible for companies or citizens to comply with regulations. A growing set of procedures at local and regional levels can undo bureaucracy reduction efforts at the national level. Multi-level governance directly alters the relationships of public administration with citizens and businesses and, if poorly managed, will negatively impact economic growth, productivity, and competitiveness.

Box 8.1. The eleventh recommendation of the 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance

11. Foster the development of regulatory management capacity and performance at sub-national levels of government.

11.1 Governments should support the implementation of regulatory policy and programmes at the sub-national level to reduce regulatory costs and barriers at the local or regional level, which limit competition and impede investment, business growth and job creation.

11.2 Promote the implementation of programmes to assess and reduce the cost of compliance with regulation at the sub-national level.

11.3 Promote procedures at the sub-national level to assess areas for which regulatory reform and simplification is most urgent to avoid a legal vacuum, inconsistencies, duplication and overlap.

11.4 Promote efficient administration, regulatory charges should be set according to cost recovery principles, not to yield additional revenue (Hoornweg, Sugar and Trejos Gómez, 2011[2]).

11.5 Support capacity-building for regulatory management at sub-national level through the promotion of e-government and administrative simplification when appropriate, and relevant human resources management policies.

11.6 Use appropriate incentives to foster the use by sub-national governments of Regulatory Impact Assessments to consider the impacts of new and amending regulations, including identifying and avoiding barriers to the seamless operation of new and emerging national markets;

11.7 Develop incentives to foster horizontal co-ordination across jurisdictions to eliminate barriers to the seamless operation of internal markets and limit the risk of race-to-the-bottom practices, develop adequate mechanisms for resolving disputes across local jurisdictions.

Source: (OECD, 2012[3]), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

Recognising the role of subnational levels of government in regulatory policy, in 2009, the OECD developed a framework for multi-level regulatory governance. The framework focuses on three priority areas for multi-level regulation (Rodrigo, Allio and Andres-Amo, 2009[4]): harmonising policies and strategies, institutions and the regulatory management tools (RIA, consultation and ex post evaluation).

Figure 8.1. Multi-level regulatory governance: Framework for analysis

Regulatory policies should encourage co-operation and co-ordination among different levels of government so ensure that laws are implemented effectively (e.g. ensuring that subnational governments have the resources to enforce regulation under their purview effectively).

The national government should also have the necessary institutions and oversight of the subnational government to make sure that subnational governments’ laws do not overlap or conflict with national laws. The national government should also create institutions to support effective regulation at subnational levels.

Finally, national governments should support the growth of the capacities of lower levels of government to manage their own rules, including support for consultation, evaluation, reducing administrative burdens and compliance and enforcement.

The organisation of regulatory attributions in the Slovak Republic

Like much of Europe, the Slovak Republic is a unitary state, where regions and municipalities powers are devolved or centralised by the national government. In the Slovak Republic, the national government has granted regions and local governments more powers since the end of the socialist era – a trend common throughout central and eastern European countries. Reforms implemented through the early 2000s gave regions more authority in areas of education,1 health care and road transportation (see for example (Csachová and Nestorová-Dická, 2011[5]). At the same time, the reform of 2002 introduced a minimum of 3 000 inhabitants to reduce the further fragmentation of municipalities in the Slovak Republic.

Despite the devolution of powers, the local and regional governments in the Slovak Republic have some of the lowest revenues in the OECD. Nearly 70% of their budgets come from national transfers or grants. The Slovak Republic also has the second smallest municipalities in the OECD, with an average of just 1 850 inhabitants per local government area.2 To support the efficient use of public resources, the Slovak Republic has encouraged joint municipal offices and has set up territorial districts to provide some services.

The local public administration system has undergone further changes since 2013. The most significant ones include the ESO Programme,3 electronic public administration, and changes in the way how self‑government works. In 2013, the district offices of integrated local state administration were re-established.

Legal structure and powers

Title 4 of the Constitution on Territorial Self-Administration sets forth the legal structure and powers of local and regional governments in the Slovak Republic (Constitute Project, 1992[6]). Municipalities and regions may generally issue binding regulations in matters of territorial self-administration, and for securing the requirements of self-administration required by law (Article 68).

The national government may allocate certain activities and powers to local governments, and the state shall cover any costs of the delegated exercise of state administration.

When exercising the powers of state administration, a municipality or region may also issue generally binding regulations within their territory. The scope of action of a territorial unit is defined in Act No. 302/2001 on the self-government of higher territorial units.

In case of conflict between regulation of a sub-national government and a national law, a court can decide on the validity of such rule or its respective parts (Act No 302/2001 on Self-government of higher territorial units, § 8a.).

Generally, the essential powers of municipalities are on delivering services. The regions have more responsibility to develop the rules and regulations that create the conditions for providing services. Municipalities and regions in the Slovak Republic are responsible for areas of education, healthcare, urban planning, and the environment. Regions are concerned with developing programs and plans to deliver social services, and the municipalities are tasked with actually carrying out the services. A full explanation of the powers granted by the Constitution is found in the chapter appendix.

Each region must have a Chief Inspector (Hlavný kontrolór) to enforce applicable regulations (Act No. 302/2001 on the self-government of higher territorial units, § 19c). The Chief Inspector has many duties. He or she controls:

the legality, efficiency and economy in the management of the property and property rights of the self-governing region, as well as the property used by the self-governing region under special regulations,

checking compliance with generally binding legal regulations, including regulations of the self-governing region,

checking the fulfilment of the council's resolutions,

checking compliance with the internal regulations of the self-governing region,

checking the fulfilment of other tasks stipulated by special regulations.

The use of regulatory management tools at the sub-national level

The national government of the Slovak Republic is unaware of any efforts to use regulatory management tools or Better Regulation at the regional or local level. However, in a few cases, cities like Bratislava have used participatory budgets (Džinić, Svidroňová and Markowska-Bzducha, 2016[7]) Many municipalities have created Joint Municipal Offices to take advantage of the economies of scale in providing certain administrative services.

The Slovak Republic does have an open government partnership and national action plan to improve consultation at the local level. As part of this plan, the government will promote the principles of open governance at regional and local levels. The Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Government for the Development of the Civil Society in co-operation with NGOs has prepared a national project to promote the participation of citizens in national and sub-national consultations (Government of the Slovak Republic, 2017[8])

However, it is near impossible for the government to compel municipalities to participate and none of the regional or local authorities has expressed explicit interest to be a part of the project so far. Given the small size of many municipalities in the Slovak Republic, it is quite likely that they may simply lack the resources and time.

As part of the RIA 2020 Strategy, the Ministry of Economy will develop a methodology for assessing the impact of regulatory proposals at the local and regional level as a first step in introducing regulatory policy at the regional and local levels.

Multilevel co-ordination and oversight

In the Slovak Republic, state administration and self-government are separate. Co-ordination between state administration and self-government bodies exists, especially in the transferred performance of state administration, the execution of which is controlled by the government. However, in recent years, the complete separation of state administration and self-government has been weakened by the fact that the district office at the seat of the region, as a local state administration body, decides at second instance on matters where municipalities or self-governing regions have decided at first instance. The district office at the seat of the region is the appellate body, regardless of whether it is original or transferred competence.

Co-operation between municipalities or self-governing regions in the Slovak Republic is solely voluntary. The government usually discuss any regulations in development with a representative Association of Towns and Communities of Slovakia (Združenie miest a obcí Slovenska or ZMOS).

Municipalities have the possibility under Act No. 369/1990 on Municipality Government to co-operate based on a contract concluded to carry out a specific task or activity. This co-operation is in practice at the 230 Joint Municipal Offices, which serve as administrative offices for municipalities to ensure transferred competencies.

The relationship between a region and a state or municipality is defined by Act No 302/2001 on the self‑government of higher territorial units. The relationship between a municipality and a state is defined by Act No. 369/1990 Coll. about the municipal constitution. The court decides any disputes arising from a public contract between the state and the municipality or region.

If several bodies at the same level believe that they are competent to act on the same matter, this conflict will be decided by their joint superior. In the case of transferred state administration, the district office at the seat of the region decides in the case of a conflict of competencies of municipalities and, in the case of self-governing regions, the Ministry, which is responsible for specific competence. Act No. 162/2015 Coll. Administrative Court Code establishes an institute of action about the question of jurisdiction in which the plaintiff may seek a decision of a conflict of jurisdiction linked to an administrative procedure.

If a municipality or a self-governing region would issue a generally binding regulation governing matters that do not fall within their competence, the Constitutional Court will decide on the discrepancy of this regulation with other legal regulations.

District offices

The district office is a local state administration body of the Ministry of the Interior of the Slovak Republic. It plays a significant role in the co-ordination and oversight of sub-national governments.

The district office at the seat of the region:

manages, supervises and co-ordinates the execution of state administration carried out by district offices based in its territorial district;

acts as the representative of the national government in matters in which the administrative proceedings at first instance are decided by the district office unless a special law provides otherwise.

is an appeal body in cases in which a higher territorial unit having its registered office in its territorial district decides in administrative proceedings at the initial stage,

is an appeal body in cases where the administrative proceedings are decided by a municipality located in its territorial district unless a special regulation provides otherwise.

The district office is managed and accounted for by the head of the district office appointed and recalled by the Government of the Slovak Republic on the proposal of the Minister of the Interior of the Slovak Republic.

District authorities carry out activities in the areas of civil protection, economic mobilisation, real estate, state defense, regional development and the environment. The responsible ministries or government authorities manage and control the tasks performed by district authorities.

Challenges and opportunities for regulatory policy in the Slovak Republic's municipalities, counties, and cities

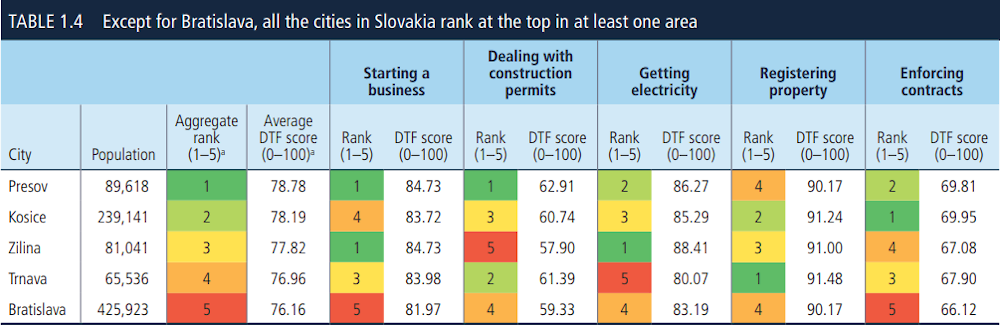

Like other countries in the region, the high level of decentralisation for providing administrative services such as construction permits and the small size of municipalities has created extremely different operating environments for businesses across the country. Intriguingly, Bratislava – the economic centre and capital of the Slovak Republic – scored the worst compared to five other municipalities in the World Bank Doing Business Index (see Figure 8.2). The World Bank estimates that if cities in the Slovak Republic adopted the best approach in each of the Index’s subcategories, the country as a whole would rise nine spots in the Doing Business Index ranking (The World Bank, 2011[9]).

Figure 8.2. Doing Business in Slovakia 2018

Notes: The distance to frontier (DTF) score shows how far a location is from the best performance achieved by any economy on each Doing Business indicator. The score is normalised to range from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the frontier of best practices (the higher the score, the better). For more details, see the chapter “About Doing Business and Doing Business in the European Union 2018: Croatia, the Czech Republic, Portugal and Slovakia.” The data for Bratislava have been revised since the publication of Doing Business 2018. The complete data set can be found on the Doing Business website at http://www.doingbusiness.org.

a. Based on the DTF scores for the five regulatory areas included in the table.

Source: (World Bank, 2018[10]).

In the United Kingdom, the Better Regulation Executive of the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy has specific programs to reduce administrative burdens at the local level in the United Kingdom.

Box 8.2. Local Regulation Programmes of the Better Regulation Executive in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is a unitary state of four countries that includes 389 large municipalities, with an average of 166 060 inhabitants. Each local government provides several local services, including housing, policing, planning and transport. The Better Regulation Executive of the United Kingdom has two main initiatives to improve regulation and service delivery at the local level (OECD, 2016[11]).

Primary Authority

The Primary Authority scheme is one of the key ways in which the U.K. Government simplifies how municipalities deliver regulation. The system enables businesses or co-ordinators, such as trade associations, to form a legal partnership with one local authority. In 2016, the scheme was simplified and expanded by the Enterprise Act 2016 and the Co-ordination of Regulatory Sanctions and Enforcement Regulations 2017. These changes have made the benefits of the programme accessible to any business, including start-ups. The number of firms participating has increased from under 18 000 in September 2017 to 57 000 in March 2018.

Better Business for All programme

The Better Business for All programme is another simplification, which brings together businesses, regulators and Growth Hubs to improve the delivery of local regulation. The U.K. Government has been supporting Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) to produce support services that understand and respond to local business needs. These partnerships help businesses access the regulatory support they need, making it easier for them to “get it right the first time,” benefitting both businesses and communities. Eighty-two percent of LEPs have Better Business for All programmes.

The Programme is still growing. As of March 2018, over 200 Local Authorities were involved in 23 LEPs areas across the country.

Source: Abbreviated from (Department for Business Energy and Industrial Affairs, n.d.[12])

Construction permits are one of the most challenging areas for cities of the Slovak Republic, suggesting that the administrative burden reduction efforts at the national level have not trickled down to cities. As a regional and municipal issue, the rules, the permitting and enforcement of municipal planning laws fall entirely on local and regional governments. Constructions and permits could be a target area for any burden reduction efforts.

Assessment and recommendations

Regulatory policy and regulatory management tools are not currently present at the local and regional level in the Slovak Republic. However, the subnational government in the Slovak Republic has significant responsibility for providing services to citizens and in crucial policy areas like transportation and urban planning.

The national government does plan to support open government and consultation at the local level through an Open Government Partnership. The Ministry of the Economy also plans to support the introduction of RIA to the local level by developing a methodology for analysis at the local and regional level.

The high-level of decentralisation has led to significant differences in how permits and licences are issued, depending on the municipality or region.

The OECD Secretariat makes the following policy recommendations:

The national government could offer to support a pilot project on RIA and evaluation with a region or city in the Slovak Republic. At this time, there are no known case studies of applying regulatory policy tools like RIA at the local level. The first stage would be to introduce the concepts for the local level and demonstrate their benefits. The current RIA 2020 Strategy foresees developing a methodology for RIA at the local level, but it should also be applied in practice.

The national government should encourage greater co-operation for providing licencing and permitting services at the subnational level. Although some joint offices exist, more efficiencies could likely be found. The national government could set up a forum to share best practices and support finding ways to reduce regulatory burdens at the local and regional level. Based on the powers of the subnational government and the concerns from the World Bank DB Index report, construction permits could be a suitable target area for finding administrative burden reductions at the local and regional level.

As a critical provider of administrative services and enforcement, regions and municipalities should be involved regularly during the development of regulation. Although many municipalities may already be represented through the Association of Towns and Communities, ZMOS, regulators could still reach out during consultations to smaller municipalities that may be unlikely to participate in an open consultation process.

The national government could support the creation of a national portal for online consultations at the local and regional level. Other countries in the region have set up single portals that make all consultations on regulations or permitting issues at the local and regional levels available online.

The interface between the national level and the European Union

The 2019 Better Regulation Practices across the EU report (OECD, 2019[13]) highlights that the complexity of today’s environment means that governments cannot address regulatory challenges at the domestic level alone. The quality of laws and regulations in the EU also depends on the quality of the regulatory management systems, both in member states and in EU institutions. The benefits of European legislation can significantly be reduced if countries’ practices of negotiating and transposing EU directives into national law are not well designed and implemented. The regulatory management systems of the EU institutions and the EU Member States therefore need to be mutually reinforcing in order to be effective.

National co-ordination of EU affairs

The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (MFEA) has been appointed national co-ordinating body of the implementation process of EU policies on 1 November 2010 with the amendment to Act No. 403/2010 Coll. 575/2001 Coll. on the Organisation of Government Activities and the Organisation of Central State Administration (Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, 2019[14]).

In this role, the MFEA is responsible for organising the co-ordination process between government and parliament and for managing issues arising from the Slovak Republic’s membership in the European Union. It also provides information on EU matters, incl. planned legislative proposals, on the MFEA website.

Responsibility for the co-ordination of key strategic EU initiatives is shared across a number of ministries and roles. For example:

The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs is responsible for the co-ordination of positions in negotiating on the EU legislation.

The Ministry of Justice, the Government Office, the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs are responsible for co-ordinating the Slovak Republic’s transposition of EU legislation.

The Ministry of Finance is responsible for co-ordinating the preparation of the National Reform Programme, including its evaluation as well as for the preparation of the Stability Programme in relation to the Europe 2020 Strategy.

The function of the Deputy Prime Minister for Investment has been established for the co-ordination of large investment projects and use of EU resources in the programming period 2014-20 (OECD, 2015[15]).

Negotiation of the national position

The process of negotiation is described in the Constitutional Law No. 397/2004 Coll., Act No. 350/1996 Coll. on Rules of Procedure of the National Council (i.e. National Parliament) and in detail in the Document to the Government Decree No. 627/2013 amended by Decree No. 485/2015. This document (Systém tvorby stanovísk k návrhom aktov EÚ a Stav koordinácie realizácie politík EÚ) contains a description of the mechanism and role of the Slovak Republic in the negotiation of an EC regulation or any other legislative or non-legislative Act (e.g. an EC draft directive). The National Commission for European Affairs may be consulted for guidance.

The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs plays a key role in the negotiation phase, overseeing the process and issuing the underlying legislation. The MFEA also creates the National Commission for European Affairs, which consists of employees of all Slovak central authorities (mainly ministries but also other bodies).

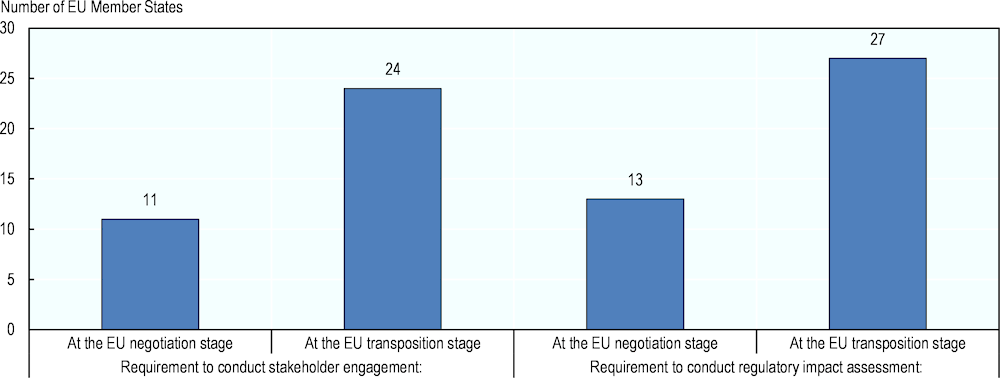

Figure 8.3. EU Member States’ requirements to conduct stakeholder engagement and RIA on EU-made laws

Note: Data is based on 28 EU Member States.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

The Slovak Republic is one of few OECD countries that require an impact assessment and the consultation of stakeholders for EC legislative proposals at the EU negotiation stage (see Figure 8.3). This is considered good practice, as the negotiation phase presents a strong opportunity for countries to directly amend the EU legislative proposal.

The process starts with the EC draft directive being distributed to the Permanent Mission of the Slovak Republic to the EU, to all Slovak central authorities and to the Parliament Office. The MFEA together with the Government Office decides the competent ministry responsible for the draft directive. The National Commission for European Affairs decides in cases of dispute. The departmental co-ordination groups (RKS) in line ministries co-ordinate in case of matters of an inter-ministerial nature and manages the co-operation between ministries.

The responsible ministry’s legal department then reviews the draft and suggests a responsible department to the minister. The minister decides on the responsible department, which is then given four weeks to prepare a preliminary opinion on the draft directive. The opinion usually includes information on the directive, its content and goals, type and time frame of the approval process as well as a subsidiarity and proportionality assessment and a regular impact assessment as required for domestic legislation.

The competent ministry then submits the preliminary opinion to the inter-ministerial commenting process, which allows other ministries and the general public to submit comments. It also submits the preliminary opinion to parliament. The opinion is also discussed in the National Commission for European Affairs. Stakeholders can participate in this discussion but are not actively invited, except for economic and social partners. Disagreements with other ministries are either solved by regular means in the consultation process (in a disagreement procedure called rozporové konanie) or by the Commission. In case a solution cannot be found, the draft is then submitted to the Government with an explanation of the issue in question.

A preliminary opinion approved of by the Government is generally binding and serves as the basis of negotiation positions of the Slovak Republic. The draft then proceeds through the approval process on EU level (Council working group, COREPER and Council meeting). The responsible ministry prepares documents on the position of the Slovak Republic for all these negotiation stages. These documents are approved by the responsible minister. The ministry then prepares a concluding report on the content of the new EU act and practical information regarding the transposition process, incl. time-frame, affected national legislation and possibly also a draft correlation table with legislative solutions.

OECD interviews shows that the practical implementation very much differs from the legally prescribed process. Ministries report regulatory management tools like RIA or stakeholder engagement are not used systematically to inform the national position.

This is a missed opportunity as Member States can use the negotiation phase to directly amend European Commission proposals before they become EU legislative acts. It is therefore important that the relevant stakeholders get an opportunity to express their views on the EU legislative proposal and that its impacts for Slovakia are adequately assessed at this stage.

Transposition into national law

The process of transposition of EU directives in the Slovak Republic is standard and similar to many OECD countries that are members of the EU.

Just as in the negotiation phase, the MFEA together with the Government Office decides the competent ministry responsible for the draft directive and the National Commission for European Affairs decides in cases of dispute. The Government office oversees the transposition process. The ministry responsible for drafting the legislation is required to conduct a regulatory impact assessment at the transposition stage and to publish the draft for public consultation on the national consultation portal Slov-Lex. The same requirements and processes apply as for regulations originating domestically. This is the case in most OECD countries (see Figure 8.3).

In OECD interviews, civil servants pointed out that RIAs conducted for EU legislation do not undergo the same rigorous quality control processes by the RIA Commission as legislation originating domestically. This is due to the limited leeway the administration has to change the EU legislation.

The transposition of EU directives into national law can be challenging and it can be useful to look to other EU countries for best practices in this regard. Some countries conduct cross-jurisdictional reviews to identify opportunities for improvement in specific areas, address inconsistencies between jurisdictions and identify gold plating in the implementation of EU-law (see Box 8.3).

Box 8.3. Comparing regulatory processes and outcomes across EU Member States

In Denmark, the EU Implementation Council can initiate so-called “neighbour checks”, i.e. reviews of methods used to implement EU legislation in other Member States with the aim to identify best practices. In 2016, the Danish Ministry of Energy, Utilities and Climate compared the transposition of the Energy Efficiency Directive in Denmark with the implementation in Sweden, Finland, Germany and the United Kingdom. The report identified, inter alia, inconsistencies with regards to the definition of large enterprises subject to mandatory energy audits, which have been subsequently clarified by the European Commission.

In 2013, the Netherlands carried out a comparative study comparing regulatory burden to SME’s in the bakery sector across selected EU Member States. The evaluation compared the impact of the regulatory frameworks in the Netherlands, Lithuania, Spain and Ireland. The assessment included the effects of EU directives, EU regulations and national laws and regulations. The purpose of the comparison was to assess whether significant differences exist in the implementation of national and EU legislation resulting in regulatory burden and to provide recommendations how to achieve significant reductions for the particular sector. The review identified opportunities for improvement in national as well as EU legislation. For instance, the report concluded that the use of exemptions and lighter regimes for SME bakeries in EU legislation can reduce regulatory burdens and improve the economic viability of these businesses.

Italy compared in 2016 its notification requirements for food business operators with those in France, Spain and the United Kingdom. The review revealed cases of gold plating: in particular, some information required to be provided to the public administration in notification forms for the registration of food businesses was identified as redundant or not required by legislation. As a result of the review, Italy revised and standardised the notification requirements in line with practices in other European countries.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2017; SIRA Consulting (2013), The CAR Methodology applied to SME bakeries and a Scoping Comparison of Regulatory Burden in four EU Member States: Final report, study commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs, Netherlands; Implementeringsrådet (2018), “Oversigt anbefalinger nabotjek”, https://star.dk/media/6417/oversigtimplementeringsraadets-anbefalinger-og-iu-svar-nabotjek.pdf. in (OECD, 2019[13]).

The issue of gold-plating

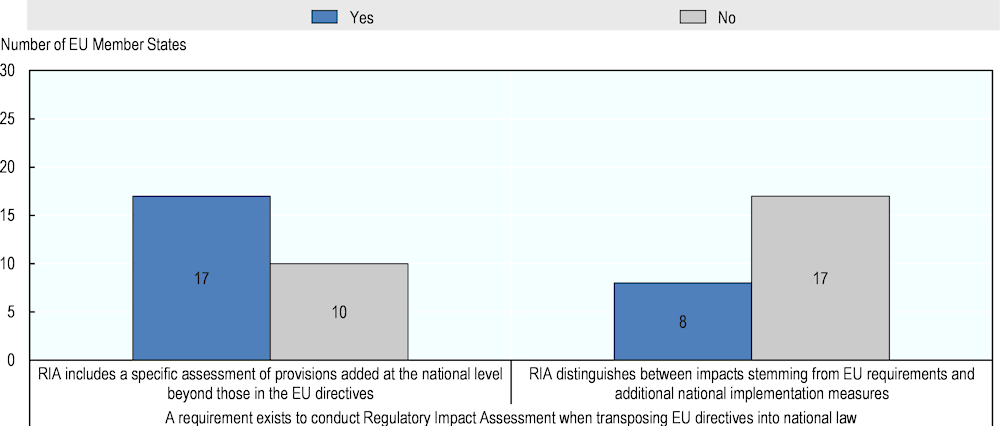

In 2018, a ministry-wide ad hoc assessment of gold-plating of existing legislation was conducted in the Slovak Republic. The assessment is considered an among EU countries unique exercise to identify burdens stemming from provisions added at the national level which go beyond those established in the EU directive.

Resolution no. 50/2019 then introduced the requirement to assess gold-plating when assessing impacts of EC directives in the Slovak Republic. This requirement is considered good practice and is in place in a majority of OECD countries, which conduct a specific assessment of provisions added at the national level (Figure 8.4, left pane), so called “gold-plating”. By doing so, countries assess the total regulatory impacts of the legislation imposed by both the EU and the member state (at national level).

Figure 8.4. Requirements to assess gold plating and national additional implementation measures

Note: Data is based on 28 EU Member States.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, and the extension to all EU Member States, http://oe.cd/ireg.

Should the analysis find that gold-plating is conducted, this should be justified in a report (dôvodová správa) accompanying the draft legislation. Ministries are required to submit their analyses and the report to the Ministry of Economy. The government resolution also requires quality control of the gold-plating assessment by expert bodies external to government, to ensure impartial quality review. In case the analysis and quality review find that provisions are added to the EC directive that pose unjustified administrative or regulatory burdens to regulated subjects, the ministry will have to revise the draft legislation.

However, ministries reported that they do not conduct the assessment systematically in practice and that the oversight body did not control whether an assessment of gold-plating was included in the impact assessment statement. There is no methodology available yet for the assessment of gold-plating but is planned to be developed according to the RIA 2020 Strategy. Some ministries, like the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, reported assessing gold-plating when legislation was transposed in their area of competence without finding any evidence of gold-plating.

In OECD interviews, business representatives in the Slovak Republic reported disproportionate administrative and regulatory burdens due to the over-implementation of EC directives. The introduction of the requirement to assess gold-plating as part of the regular RIA procedure was an important step to tackle this issue.

Assessment and recommendations

The Slovak Republic has successfully put in place a government structure for co-ordinating the interface between national- and EU-level. Responsibilities for the co-ordination of key strategic EU initiatives are shared across a number of ministries and roles with the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs as the national co-ordinating body for EU initiatives. The Ministry of Finance is responsible for co-ordinating the preparation of the National Reform Programme, including its evaluation as well as for the preparation of the Stability Programme in relation to the Europe 2020 Strategy. The function of the Deputy Prime Minister for Investment has been established for the co-ordination of large investment projects and use of EU resources in the programming period 2014-20.

The responsibilities for co-ordinating the EU legislative process are shared between different ministries. The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs is responsible for the co-ordination of positions in negotiating EU legislation. The Ministry of Justice, the Government Office, the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs are responsible for co-ordinating the Slovak Republic’s transposition of EU legislation. This means that the current institutional set-up bears a risk of overlapping and unclear functions.

Regulatory management tools are rarely used to inform the national position during the negotiation phase. The negotiation phase presents a strong opportunity for Member States to directly amend European Commission proposals (as introduced to Council and the European Parliament) before they become EU legislative acts. It is therefore important that the relevant stakeholders get an opportunity to express their views on the EU legislative proposal and that its impacts for the Slovak Republic are adequately assessed at this stage. There is a requirement in place in Slovakia to consult relevant stakeholders and assess impacts of the draft legislation when developing the national position on the EU draft legislation. This requirement is not yet systematically followed in practice and there is no regulatory oversight in place to ensure regulatory management tools are used to inform the national position.

The recently introduced requirement to assess gold-plating follows EU best practice, but is not yet conducted systematically in practice. Ministries reported that they do not conduct the assessment systematically and that the oversight body did not control whether an assessment of gold-plating was included in the impact assessment statement. There is no methodology available yet for the assessment of gold-plating but is planned to be developed according to the RIA 2020 Strategy.

The OECD Secretariat makes the following policy recommendations:

The roles of different institutions involved in co-ordinating the EU legislative process should be clarified. In particular the mandate boundaries between the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs and the Government Office with respect to managing relations with the EU should be clarified to eliminate the potential for overlap and duplication. The Government Office’s responsibility for managing the transposition of EU legislation into national law, and the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs’ mandate of advancing the Slovak Republic’s national interests in Brussels before, during and after the EU decision-making process implies that the institutions need to work closely together and co-ordinate their activities vis-à-vis line ministries effectively on an ongoing basis.

The Slovak Republic should ensure that a proportionate analysis of impacts is carried out and relevant stakeholders are involved in the process of preparing national positions to draft EU legislation. Criteria for when such assessment is necessary should be set by the Government decree describing the processes to be carried out during the negotiation phase. In addition to applying regulatory management tools on national level when negotiating the national position and transposing EU directives into national law, the Slovak Republic should use the results of regulatory management tools (e.g. RIA) conducted at EU level to inform the process. While the European Council and Parliament carry out impact assessments for substantial amendments to the Commission’s regulatory proposals, the impacts of these amendments may not adequately assessed by individual member states, which could cause unnecessary burdens for individual countries. The impact assessments conducted on both EU- and national level should therefore inform the development of the national position for the negotiation phase in EU council. This effort should be supported by a body tasked with regulatory oversight functions ensuring the use of RIA and stakeholder engagement at the negotiation stage.

The assessment of gold-plating as part of the impact assessment process should be reviewed more closely by the oversight body. The RIA Commission should review if an assessment of gold-plating has been included in the RIA statement and should prompt ministries to do so should this not be the case.

References

[6] Constitute Project (1992), Slovakia’s Constitution of 1992 with Amendements through 2014, http://www.worldbank.org (accessed on 6 February 2020).

[5] Csachová, S. and J. Nestorová-Dická (2011), Territorial Structure of Local Government in the Slovak Republic, the Czech Republic and the Hungarian Republic – A Comparative View, Geografický Časopis / Geographical Journal, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267824054_TERRITORIAL_STRUCTURE_OF_LOCAL_GOVERNMENT_IN_THE_SLOVAK_REPUBLIC_THE_CZECH_REPUBLIC_AND_THE_HUNGARIAN_REPUBLIC_-_A_COMPARATIVE_VIEW (accessed on 17 February 2020).

[12] Department for Business Energy and Industrial Affairs (n.d.), Better regulation: annual report 2018 to 2019 - GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/better-regulation-annual-report-2018-to-2019 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

[7] Džinić, J., M. Svidroňová and E. Markowska-Bzducha (2016), “Participatory Budgeting: A Comparative Study of Croatia, Poland and Slovakia”, NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, Vol. 9/1, pp. 31-56, http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/nispa-2016-0002.

[8] Government of the Slovak Republic (2017), Open Government Partnership and National Action Plan of the Slovak Republic.

[2] Hoornweg, D., L. Sugar and C. Trejos Gómez (2011), “Cities and greenhouse gas emissions: moving forward”, Environment and Urbanization, Vol. 23/1, pp. 207-227, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0956247810392270.

[1] Marcou, G. and A. Musa (2017), “Regulatory Impact Assessment and Sub-national Governments”, in Evaluating Reforms of Local Public and Social Services in Europe, Springer International Publishing, Cham, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61091-7_2.

[14] Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs (2019), National Coordination of European Affairs, https://www.mzv.sk/europske_zalezitosti/europske_zalezitosti_na_ministerstve-vnutrostatna_koordinacia_europskych_zalezitosti (accessed on 30 January 2020).

[13] OECD (2019), Better Regulation Practices across the European Union, OECD, http://dx.doi.org/GOV/RPC(2018)15/REV1.

[11] OECD (2016), OECD Regions at a Glance 2013 – United Kingdom Profile.

[16] OECD (2016), Regional Policy Profile: Slovak Republic.

[15] OECD (2015), Slovak Republic: Better Co-ordination for Better Policies, Services and Results, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/governance/slovak-republic-better-co-ordination-for-better-policies-services-and-results-9789264247635-en.htm (accessed on 19 December 2019).

[3] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

[4] Rodrigo, D., L. Allio and P. Andres-Amo (2009), “Multi-Level Regulatory Governance: Policies, Institutions and Tools for Regulatory Quality and Policy Coherence”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 13, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/224074617147.

[9] The World Bank (2011), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/570761468032937505/Doing-business-in-the-Croatia-2012-comparing-business-regulation-in-25-cities-and-183-economies.

[10] World Bank (2018), Doin Business in the European Union in 2018: Croatia, the Czech Republic, Portugal and Slovakia, https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/media/Subnational-Reports/DB18-EU2-Report-ENG.PDF (accessed on 5 March 2020).

Annex 8.A. Powers in the two local government acts in the Slovak Republic

This annex describes the powers laid out explicitly in the two local government acts in the Slovak Republic.

Powers of municipalities (Act No. 369/1990 on municipal government):

a. performs operations related to the proper management of the movable and immovable property of the municipality and property owned by the state, which the municipality has left for use,

b. draws up and approves the municipal budget and the municipality's final account; declares a voluntary collection,

c. make decisions on local taxes and local fees 5a) and administer them,

d. directs economic activity in the municipality, and if so stipulated by a special regulation, 5b) issues a consent, binding opinion, opinion or statement on business and other activities of legal persons and natural persons and on the location of operations in the municipality;

e. creates an effective control system and creates appropriate organisational, financial, personnel and material conditions for its independent performance,

f. ensures construction and maintenance and administers local roads, public spaces, municipal cemetery, cultural, sports and other municipal facilities, cultural monuments, heritage sites and landmarks of the municipality,

g. maintaining cleanliness in the municipality, management and maintenance of public greenery and public lighting, water supply, wastewater disposal, wastewater management and local public transport,

h. establishes and protects healthy conditions and a healthy way of life and work of the inhabitants of the municipality, protects the environment as well as creates conditions for providing health care, education, culture, enlightenment activities, interest artistic activity, physical culture and sport,

i. performs tasks in the field of consumer protection and creates conditions for supplying the municipality; Manages marketplaces

j. procures and approves zoning and planning documentation of municipalities and zones, the concept of development of individual areas of community life, procures and approves housing development programs and co-operates in creating suitable conditions for housing in the municipality,

k. carries out its own investment and business activities in order to ensure the needs of the inhabitants of the municipality and the development of the municipality,

l. establishes, abolishes and controls its budgetary and contributory organisations, other legal entities and facilities according to special regulations,

m. organises local referendum on important issues of community life and development,

n. ensures public order in the municipality,

o. ensures the protection of cultural monuments in the scope pursuant to special regulations and ensures the preservation of natural values,

p. performs tasks in the field of social assistance to the extent pursuant to a special regulation,

q. performs certification of documents and signatures on documents, leads the general chronicle in the state language or in the language of a national minority

Powers of regions (Act No 302/2001 on the self-government of higher territorial units):

a. ensures the creation and implementation of the program of social, economic and cultural development of the territory of the self-governing region,

b. carries out planning activities concerning the territory of the self-governing region,

c. procures, discusses and approves territorial planning documents of the self-governing region and territorial plans of regions,

d. make efficient use of local human, natural and other resources,

e. carries out its own investment and business activities in order to ensure the needs of the inhabitants of the self-governing region and the development of the self-governing region,

f. establishes, abolishes and controls its budgetary and contributory organisations and other legal entities according to special regulations,

g. participates in the creation and protection of the environment,

h. creates preconditions for the optimal arrangement of mutual relations of settlement units and other elements of its territory,

i. procures and approves a development program for the provision of social services and co-operates with municipalities and other legal entities and natural persons in the construction of facilities and flats intended for the provision of social services,

j. creates conditions for the development of health care,

k. creates conditions for the development of education, particularly in secondary schools, and for the development of further education,

l. creates conditions for the creation, presentation and development of cultural values and cultural activities and takes care of the protection of the heritage fund,

m. creates conditions for the development of tourism and co-ordinates this development,

n. co-ordinates the development of physical culture and sports and the care of children and youth

o. co-operates with municipalities in creating programs of social and economic development of municipalities,

p. participates in solving problems concerning several municipalities in the territory of the self-governing region, develops co-operation with local authorities and authorities of other countries, performs other powers laid down by special laws

Notes

← 1. Education is the largest spending area for regions and municipalities in the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2016[16]).

← 2. France has the third smallest and the Czech Republic the smallest municipalities.

← 3. The ESO programme (Efficient, Reliable and Open state administration) was approved in 2012 to support the efficient delivery of services for citizens.