This chapter examines the institutional framework for regulatory policy in the Slovak Republic. Regulatory management needs to find its place in a country’s institutional architecture, and capacities for promoting and implementing Better Regulation need to be build up. Mechanisms and institutions need to be established to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals, support and implement regulatory policy and thereby foster regulatory quality.

Regulatory Policy in the Slovak Republic

3. Institutional framework and capacities for regulatory policy

Abstract

Key institutions and regulatory policy oversight of the regulatory process in the Slovak Republic

The institutional set-up of regulatory policy matters. Regulatory management needs to find its place in a country’s institutional architecture and have support from all the relevant institutions. The institutional framework extends well beyond the executive centre of government, although this is the main starting point. The legislature and the judiciary, regulatory agencies and the sub-national levels of government also play critical roles in the development, implementation and enforcement of policies and regulations.

(OECD, 2012[1]) advises governments to “establish mechanisms and institutions to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals, support and implement regulatory policy, and thereby foster regulatory quality.”

Regulatory oversight is a critical aspect of regulatory policy. Without proper oversight, undue political influence or a lack of evidence-based reasoning can undermine the ultimate objectives of policy. Careful, thoughtful analysis of policy and an external check of policy development are required to ensure that governments meet their objectives and provide the greatest benefits at the lowest costs to citizens. Allocating roles and responsibilities and defining tasks throughout the regulatory process, especially ensuring that regulatory management tools are used effectively, are key success factors in any regulatory policy system. Accordingly, the OECD have stated that bodies tasked with regulatory oversight should be tasked with five functions (see Box 3.1):

Box 3.1. Main features of regulatory oversight bodies to promote regulatory quality

Principle 3 of the 2012 OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance calls for countries to “establish mechanisms and institutions to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals, support and implement regulatory policy and thereby foster regulatory quality” (OECD, 2012[1]). The Recommendation highlights the importance of “a standing body charged with regulatory oversight (…) established close to the centre of government, to ensure that regulation serves whole-of-government policy” and outlines a wide range of institutional oversight functions and tasks to promote high quality evidence-based decision making and enhance the impact of regulatory policy.

In line with the Recommendation, a working definition of “regulatory oversight” has been employed in the 2018 Regulatory Policy Outlook (OECD, 2018[2]), which adopts a mix between a functional and an institutional approach. “Regulatory oversight” is defined as the variety of functions and tasks carried out by bodies/entities in the executive or at arm's length from the government in order to promote high-quality evidence-based regulatory decision making. These functions can be categorised in five areas, which however do not need to be carried out by a single institution/body:

Table 3.1. Regulatory oversight functions and key tasks

|

Areas of regulatory oversight |

Key tasks |

|---|---|

|

Quality control (scrutiny of process) |

|

|

Identifying areas of policy where regulation can be made more effective(scrutiny of substance) |

|

|

Systematic improvement of regulatory policy (scrutiny of the system) |

|

|

Co-ordination (coherence of the approach in the administration) |

|

|

Guidance, advice and support(capacity building in the administration) |

|

Source: (OECD, 2018[2]), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en; (OECD, 2012[1]), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

As is the case in many OECD countries, Slovakia has a fragmented institutional landscape for regulatory policy, and responsibilities for regulatory oversight are split among several authorities. The RIA Commission is responsible for overseeing the quality of regulatory impact assessments and is part of the Legislative Council of the Government, which reviews the legal quality of government regulations and the compliance of legislation with EU-law. The Ministry of Economy co-ordinates better regulation efforts across the administration and ensures the RIA process is carried out in line with the Unified Methodology. Lastly, the Ministry of Justice is responsible for co-ordinating the inter-ministerial commenting procedure.

The key institutions tasked with regulatory oversight functions and/or involved in regulatory policy in the Slovak Republic are described in the following:

Legislative Council of the Government

Established by Art. 2 III Act. No 575/2001 Coll., the Legislative Council of the Government is a permanent advisory and co-ordinating body of the Government. The Chairman is the Minister of Justice.

The Council is responsible for reviewing the legal quality of government regulations and the compliance of legislation with EU-law. The Council also establishes permanent advisory bodies of the Government of the Slovak Republic. After the comments proceedings the legislative draft is discussed with the Council where an agreement must be reached. If no agreement with the sponsoring ministry is reached, the Council issues an opinion to the Government.

RIA Commission

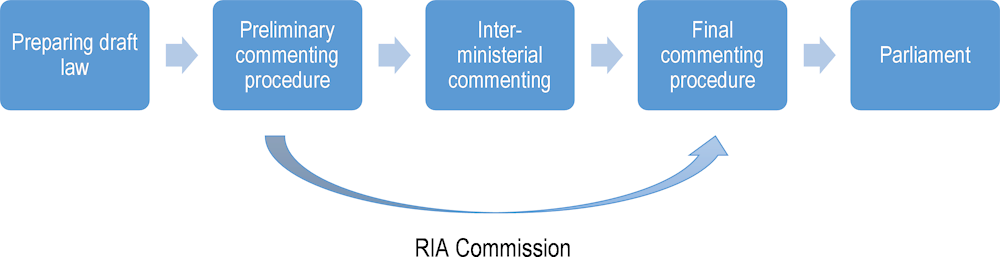

The Commission is chaired by the State Secretary of the MoE. Several ministries (Ministry of Economy as a co-ordinator, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of the Interior and Deputy Prime Minister’s Office for Investments and Informatisation) are represented in the Commission as well as the Government Office and the Slovak Business Agency. They share competencies for checking the quality of RIAs with each one focusing on their area of competences (OECD, 2018[2]): The Ministry of Economy reviews impacts on the business environment, the Ministry of Finance focuses on budget impacts, the Ministry of Labour on social impacts and the Ministry of Environment on environmental impacts, the Ministry of Interior scrutinises the impact on public services provided for citizens, the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office for Investment and Informatisation reviews impacts on the “informatisation” of society (see Figure 3.1). A new impact area on marriage, parenthood and family was introduced in 2018 by Act No. 217/2018, but is not yet reflected in the Unified Methodology and has not been assigned to a concrete ministry.

Figure 3.1. The RIA Commission

Source: Information received from the Government of the Slovak Republic.

According to Art.3 of the Unified Methodology, the RIA Commission is responsible for

Providing methodological support to civil servants tasked with drafting legal texts and impact statements;

Assessing the quality of the RIA process and the impact assessment statements at the draft and final stage;

Informing the submitter of the Commission’s opinion on the impact assessment statement;

Granting permission to conduct a shortened RIA following Art. 2.6.

The Commission does not comment on the substance of the legislative draft. Instead, it reviews the regulation’s impacts on the general government budget, business environment (including SME test), social impacts, environmental impacts, impacts on the informatisation of society and impacts on public administration services for the citizen as presented in the RIA statement.

Most of these key oversight functions outlined in Box 3.1 are covered by the RIA Commission (quality control of RIA; providing guidance and support and systematic improvement of regulatory policy) and the Legislative Council (reviewing legal quality). However, some key functions are currently not fulfilled. Notably, there is no body in charge of reviewing the quality of stakeholder engagement processes or identifying areas of policy where regulation can be made more effective. The co-ordination function is currently carried out by the Ministry of Economy.

The quality review process of RIA is conducted in three phases. In phase 1, the preliminary commenting, ministries are required to send the legislative draft with the accompanying RIA to the RIA commission for review. According to the Rules of Procedure of the RIA Commission, the Commission then has 10 days to issue a first opinion. Once the RIA has been adjusted (if necessary), the draft and RIA are published on the consultation portal Slov-Lex.sk for phase 2, the inter-ministerial commenting procedure, where both public and other ministries can provide comments. The ministry sponsoring the legislation then addresses the comments provided and the commission, if necessary, reviews the RIA again in phase 3 before sending the documents to Parliament. Phase 3 only takes place if the impacts have been changed following the inter-ministerial commenting phase, or if one of the ministries explicitly demands to send the legislation into phase 3. All final statements issued by the Commission can be found in its annual report and on the MoE’s website, a helpful practice ensuring transparency of the quality review process.

Figure 3.2. The process of quality review of RIA by the RIA Commission

Source: Information received from the Government of the Slovak Republic.

The Commission’s opinions can be positive (without any comments), positive with recommendations for revision (minor comments), negative (substantial comments). It cannot stop the legislation from going forward should the RIA quality be insufficient. OECD interviews showed that there is an issue with ministries not revising the RIA statement after a negative opinion issued by the Commission, pointing to a potential lack of authority of the oversight body. According to the RIA Commission’s 2018 annual report, two-thirds of regulations are submitted to Parliament even though the Commission had voiced quality concerns about the RIA statement.

The Commission only reviews the quality of individual impacts in the portfolio of individual institutions represented in the Commission in isolation and not the overall quality of the RIA and total impacts on the welfare of the society, including whether the overall benefits justify the potential costs stemming from regulatory drafts. It also does not review the quality of stakeholder engagement processes with the general public.

The RIA commission usually only meets once a year, depending on current needs, and does not meet with the ministries sponsoring legislative drafts. This is a missed opportunity as meeting with ministries and providing continuous advice throughout the drafting process could significantly improve the RIA. The Commission does however provide some guidance on FAQs online1 and answers questions via email and telephone, following its responsibility to provide methodological support to ministries according to the Unified Methodology.

RIA Commission Secretariat

The Commission’s secretariat is the first point of contact for ministries and central government bodies, it reviews the material submitted to the Commission for completeness and the most serious shortcomings, is in charge of communication and supporting law drafters with procedural issues and prepares the Commission’s annual report. It does not however conduct a preliminary review of the RIA statements submitted in terms of burdens presented. This practice could help ease the Commissions workload by targeting its efforts to the RIA statements for the most burdensome pieces of legislation.

Ministry of Economy

According to Art. 3 of the Unified Methodology, the Ministry of Economy is responsible for promoting regulatory quality across the administration and the MoE’s Department for Business Environment was appointed national co-ordinator of better regulation efforts.

The ministry is responsible for:

Managing the RIA process and ensuring it is carried out in line with the Unified Methodology;

Deciding which legislative drafts will be subject to consultations with businesses prior to the preliminary commenting procedure (PKK) following Art. 5.4;

Co-ordinating the RIA Commission;

Issuing regular opinions on the conformity of the RIA process with the requirements set out in the Unified Methodology in its annual reports2;

Implementing the national project Improvement of the Business Environment in Slovakia and evaluating policies in the competence of the ministry with the goal to reform the Better Regulation processes in the Slovak Republic.

In its function as member of the RIA Commission the Ministry of Economy reviews impacts on the business environment.

Government Office

The Slovak Republic refers to the Government Office as its centre-of-government institution (OECD, 2019[3]). As laid out in the Statute of the Government Office of the Slovak Republic,3 its main responsibilities include: reviewing the performance and implementation of tasks within the state administration as well as of tasks resulting from government resolutions, ensuring action is taken on petitions and complaints, co-ordinating the performance of tasks for the development of the information society, and co-ordinating the implementation of policies of the European Communities and the European Union. The Government Office currently has a rather limited role in co-ordinating government policies, however in March 2020 a new Deputy Prime Minister for legislation and strategic planning has been appointed that likely will take on a co-ordination function for RIA. The Deputy PM will act as chair of the Legislative Council of the Government.

The Implementation Unit within the Government Office is responsible for the review and evaluation of spending goals defined by the Ministry of Finance, mostly VfM spending reviews but IU has recently also been tasked with reviewing the implementation of the 2030 strategy at the Ministry of the Environment. It co-operates closely with the ministries in this regard, preparing the implementation plan for them and continuously reviewing implementation for three years. The IU currently employs five staff members funded from EU and another three from the state budget.

The Institute for Strategy and Analysis (ISA) provides analytical support for economic and social policies of the Prime Minister and Government Office in line with economic policy objectives and strategic priorities of the Government programme, including the European Union’s cohesion policy. The Institute co-operates closely with other analytical units of central state administration bodies for the development of strategy documents. ISA conducts research on topics like regional policy, innovation, health policy, education, and the impacts of EU funds allocation. Recently, ISA has become the Secretariat for the National Productivity Board and has been charged with preparing the annual report on productivity and competitiveness of the Slovak economy. There are 10 analysts currently employed at the Institute.

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister for Investment and Informatisation

The Deputy Prime Minister’s office reviews impacts on the informatisation of society in its function as member of the RIA Commission. It also co-ordinates large investment projects and the use of EU resources in the programming period 2014-20. Since 2019, there is a Behavioural Unit at the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic for Investments and Informatisation called Behavioral Research and Innovations Slovakia. The Office also oversees the Slovak Republic’s digital governance agenda.

Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Government for the Development of Civil Society

The Office of the Plenipotentiary of the Government for the Development of the Civil Society, located within the Ministry of Interior, organises the Government Council for NGOs which is chaired by the Ministry of Justice. One of its tasks is ensuring ministries’ compliance with the preparation of the Report on Public Participation on the outcomes of the public consultation process for a legislative proposal. The report on public participation in the drafting of legislation is prepared by the proposer before submitting it to the inter-ministerial commenting procedure. Once a year, the Plenipotentiary's Office controls the compliance with this obligation within the fulfilment of the AP OGP 2017-2019 task. The Office is also tasked with promoting e-services and e-government in the Slovak Republic.

Government Council for NGOs

The council consists of representatives of ministries and more than 30 NGOs. It aims to “contribute to the development of participative democracy in Slovakia” to ensure that government policies and regulations are “not only efficient, fair and democratic, but also adopted based on a wide consensus of the government and the non-governmental sector and its implementation was controlled by the civil society”. This platform is, however, more used to discuss general policies, strategies or projects on co-operation with NGOs than to find NGOs’ views on particular specific policies or regulations (OECD, 2015[4]).

Ministry of Finance

The Ministry of Finance is responsible for managing the national fiscal framework, including: the national budget, taxes and fees, customs, financial control, internal audit and government audit. It launched the Value for Money Initiative, which aims to promote evidence-based policy making and efficiency within the public sector by conducting spending reviews. By preparing and overseeing the fiscal framework and state budget, the Ministry of Finance fulfils a key centre-of-government function. (OECD, 2015[4]) The Ministry of Finance also reviews budget impacts in its function as member of the RIA Commission.

Ministry of Justice

The Ministry of Justice is responsible for managing the national consultation portal Slov-Lex.sk. The Ministry chairs the Legislative Council of the Government, which is responsible for scrutinising legal quality before submitting the legislative proposal to the Government, and it reviews the compliance of the legislation with the EU acquis.

Ministry of the Interior

The Ministry of the Interior is the managing authority for the EU Operational Programme Effective Public Administration (OP EPA), which funds the Ministry of Economy’s national project on Better Regulation. The OP EPA aims to support the government-wide public administration reform by supporting investment into the institutional capacities and into the effectiveness of public administration and public services at national, regional and local level, thus contributing to the implementation of reforms, better legal regulation and good governance.

The Ministry of Interior reviews impacts on public administration services for the citizen in its function as member of the RIA Commission.

Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs

The Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs co-ordinates the Slovak Republic’s position on EU matters, for which it has 90 staff stationed at the Permanent Delegation to the European Union in Brussels. The MFEA operates a government-wide commission that meets weekly to discuss proposals currently being discussed in COREPER I (Comité des représentants permanents) and COREPER II.

Other institutions

Parliament

The Rules of Procedure of the Parliament 4 serve as a legal framework for activities carried out by the National Council of the Slovak Republic. §2 spells out its powers, which include i.e. discussing legislative proposals and deciding on the Constitution, constitutional amendments, constitutional laws and laws and controlling their compliance,

The requirement to conduct an impact assessment as stated in the Unified Methodology does not apply to legislation initiated by the National Council. As in most OECD countries, the results of RIA are not sufficiently used in parliamentary discussions and there is no impact assessment conducted on changes made to legislation in parliament.

The Parliamentary Institute, which is the parliament’s analytical unit, provides data and research upon request from MPs. The institute co-operates with institutes in other countries to prepare information on international practices. It currently employs 9 staff members.

The Slovak Business Agency

The Slovak Business Agency is a non-profit organisation for the support of small and medium-sized enterprises. It was founded in 1993 through a common initiative of the EU and the government of the Slovak Republic. It is a unique platform of public and private sectors. The founding members include the Ministry of Economy of the Slovak Republic, the Entrepreneurs Association of Slovakia and the Slovak Association of Crafts.

The Better Regulation Centre is the Business Agency’s analytical unit. It is represented in the RIA Commission, issuing partial statements on the assessment of impacts on SMEs and carrying out the ex ante and ex post SME-tests. The Centre consults with businesses on the impacts identified in the SME‑test and advocates for their interests with regulators. It currently counts four employees.

Council for Budget Responsibility (Fiscal council)

The Council for Budget Responsibility is an independent body for monitoring and evaluating the fiscal performance of the Slovak Republic. Its main tasks are defined in Constitutional Act No. 493/2011 on Fiscal Responsibility:

Preparing an annual report on the long-term sustainability of public finances;

Submitting a report to parliament on the government’s compliance with fiscal responsibility and fiscal transparency rules;

Review and publish opinions on budget impacts of legislative proposals submitted to parliament;

Providing information on alternative regulatory scenarios and provide suggestions how to improve the methodology for calculating indicators in the area of public finances.

Judiciary

The Constitutional Court rules on the compatibility of laws, decrees (either by government or local administration bodies) and legal regulations (issued by local state administration or resulting from international treaties) with the Constitution. It also decides on disputes between state administration bodies and complaints against decisions issued by a state body.

Matters of administrative law mainly fall under the authority of regional courts (krajský súd) and the Supreme Court (Najvyšší súd Slovenskej republiky). The Slovak Republic does not have separate administrative courts; rather, there are separate chambers of administrative judges.

In 2015, a comprehensive legal reform of Slovak procedural law was undertaken to speed up the process of judicial proceedings, introduced by Act No. 160⁄2015 Coll. Civil Proceedings Code for Adversarial Proceedings (Civilný sporový poriadok), Act No. 161⁄2015 Coll. Civil Proceedings Code for Non-adversarial Proceedings (Civilný mimosporový poriadok), and Act. No. 162⁄2015 Coll. Administrative Proceedings Code (Správny súdny poriadok).

OECD stakeholder interviews still showed that judiciary proceedings typically progress slowly, effectively making judicial appeals unattractive for businesses.

Local governments

Title 4 of the Constitution on Territorial Self-Administration sets forth the legal structure and powers of local and regional governments in the Slovak Republic (Constitution of the Slovak Republic). Municipalities and regions may generally issue binding regulations in matters of territorial self-administration, and for securing the requirements of self-administration required by law (Article 68). The interface between the national and sub-national level is further discussed in Chapter 8.

Co-ordination of the Better Regulation policy across government

According to art. 3 of the Unified Methodology, the Ministry of Economy is the national co-ordination body for better regulation in the Slovak Republic. It promotes a whole-of-government, co-ordinated approach to regulatory quality. The MoE was in charge of the development of the Unified Methodology and ensures the conformity of the RIA process with its requirements. The MoE’s role in the RIA system is well respected, but as a line ministry it finds itself in a difficult position to drive a cross-government horizontal objective such as regulatory quality. Also, with its department for business environment, the Ministry of Economy is a strong advocate for businesses in the Slovak Republic. Also, with its Department for Business Environment, the Ministry of Economy is a strong advocate for businesses in the Slovak Republic. In its role as national co-ordination body for better regulation the MoE has been steering the better regulation agenda towards a pro-business approach – to the disadvantage of other stakeholder groups.

The Ministry of Justice is in charge of the inter-ministerial co-ordination process and manages the inter-ministerial commenting procedure via the government’s consultation portal Slov-Lex.sk.

In March 2020, a new Deputy Prime Minister for legislation and strategic planning has been appointed in the Government Office. The new Deputy PM will act as chair of the Legislative Council of the Government, and as such will likely take on a co-ordination function for RIA. If realised, this new institutional set-up would be in line with the OECD’s 2012 Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, which suggests regulatory management tools like RIA should be supported at the centre of government.

Inter-ministerial co-ordination during the development of regulations

According to Art. 13 of the Legislative Rules of the Government of the Slovak Republic and § 10 of the Act on Lawmaking and on the Collection of Laws No. 400/2015, a legislative proposal has to be shared with ministries and the public in what is called the “inter-ministerial commenting procedure”.

Figure 3.3. Inter-ministerial commenting procedure

The Ministry of Justice runs Slov-Lex.sk, the website where all legislative drafts are published for consultation (see Figure 3.3). Legislative drafts are shared with ministries and the general public and all comments on the drafts are publicly available. Users can see what stage of the consultation process the draft legislation is in (e.g. “inter-ministerial commenting procedure”) and when the consultation process has started. The inter-ministerial commenting procedure is repeated if there were very important changes in changes made within the draft. After the second stage, the proposer prepares a report on the outcomes of the consultation process. Once a year, the Plenipotentiary's Office analyses compliance with this obligation.

Comments from relevant authorities have the statute either of “suggestions” (not binding), or “objections” (substantial comments, binding). The ministry sponsoring the legislation is obliged to react to comments provided. It has to declare whether a) the comment was accepted and legislative proposal was changed; b) the comment was partially accepted – this must be followed by an explanation why it was not fully accepted; c) the comment was not accepted at all, followed by an explanation why it was not accepted at all. A list of all comments made in this procedure with their status (accepted/partially accepted/not accepted at all), including explanations and proposers’ statements, has to be uploaded on the Slov-Lex website.

If the ministry sponsoring the legislation does not accept any objection (substantial comment), a dispute meeting (rozporová komisia) has to be organised to solve the issue. If the matter remains unsolved, the document is submitted to the meeting of the Legislative council with objections (s rozporom). The dispute may even be brought to the meeting of the Government Office to be decided upon. Resources, training and guidance.

Resources

The culture of using evidence and analytical support in the decision-making process is not yet firmly embedded in the functioning of the Slovak government. There is both a lack of demand for evidence and analysis from decision makers when discussing government policies, programmes and/or regulations, and a lack of analytical capacities in line ministries to be able to produce said evidence.

A unique resource: analytical institutes in line ministries

This lack of analytical capacities comes as a surprise, given the competitive advantage the Slovak Republic enjoys in terms of analytical capacities compared to other countries in the region: the analytical institutes that have been established in most Slovak ministries. The institutes are specialised units operating within the portfolio of their ministry and serve to provide analytical background for the ministry’s decisions. Their structures, competences and position in the organisation of the ministry vary. Some institutes have only been established very recently and compared to other institutes still lack resources and overall capacities.

There are no systemic, formalised procedures on how to involve the analytical institutes in the decision-making process in their ministry. While the IFP produces a significant number of policy briefs and working papers, including economic forecasts and inputs for medium-term budgets, it is at the discretion of the Minister of Finance or the government whether to use these analyses to support their decisions. The IFP is regularly asked to provide the Minister of Finance with advice and supporting analysis; however, this only occurs in an ad hoc manner without any formal rules, and may change with every new minister (OECD, 2015[4]).

Box 3.2. Institute for Financial Policy of the Slovak Ministry of Finance

The Institute for Financial Policy (IFP) is a special unit of the Slovak Ministry of Finance with the status of a section. Operating within the Ministry of Finance’ portfolio, the institute’s mission is to provide reliable macroeconomic and fiscal analyses and forecasts for the Slovak government, especially the Minister of Finance, as well as for the general public. The Head of the institute reports directly to the State Secretary of the Ministry of Finance. The IFP’s main goals are to contribute to the transparency of the budgeting process in the Slovak Republic, the sustainability of public finances and the effectiveness of public finances, including taxation and public expenditure. The IFP’s main activities are:

macroeconomic analyses and forecasts

tax analyses and forecasts

fiscal analyses and forecasts

expenditure analysis

structural reforms

analytical service for the management of the Ministry of Finance.

The IFP provides inputs to the government for its strategic documents such as the Stability Programme or the National Reform Programme and for its medium-term budgets. In addition, the institute is also known for publishing its own economic analyses, working papers and commenting on recent developments and economic indicators.

Source: (OECD, 2015[4]).

In the case of other ministries, the practices of involving analytical centres in the decision-making process is less common. Some ministries like the Ministry of Health closely involve the analytical units in the legislative process, the institute helps with RIA and can even prepare its own laws. The Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic involves its analytical unit in the legislative process from the very beginning, giving them certain tasks like the assessment of certain impacts and the unit would provide the necessary data. However, there are no formal communication channels in place and some ministries barely co-operate with their analytical unit, for example in the case of the Ministry of Environment. The impulse for change to more closely involve the institutes in ministry work usually comes from public scandals, creating the need to support policy decisions with analytical evidence in the public eye. In cases where the analytical units are closely co-operating with the ministry’s legal unit and are involved in the RIA process, the RIA tends to be of better quality and the ministries consider the support helpful.

Co-ordination between the different institutes varies. The Institute of Financial Policy has the central co‑ordinating role between ministries, but co-ordination is not systematically ensured. The Institute of Health helps other units with impact assessments relating to public health and has substantial data available in this regard. The institute also reviews impact assessments accompanying legislative drafts sent from other ministries. The Ministry of Education’s analytical unit works closely with the IFP and the Institute for Labour. However, there were also cases where information between different analytical units could not be shared because of legal issues. Generally, analytical institutes pointed out that co-ordination between units was still in its infancy and could be improved.

Size and resources of the analytical institutes also vary. The IFP is the institute with the highest status, enjoying sufficient resources available to them, but other institutes are facing some difficulties in this regard. Especially some of the more recent analytical units seem to be struggling for resources and have difficulties attracting and keeping highly skilled staff. The Institute of Health counts 15 people in two departments, the Institute of Education employs 10 people all funded from EU-funds, but other institutes reported they have 1-5 staff available on average.

The lack of involvement of the institutes in ministry work is not only a problem of supply (i.e. the institutes’ resources), but also of demand for analytical information and evidence. It seems that many senior decision makers in ministries are not fully aware of the analytical capacities available in institutes and there is a lack of interest in demanding analysis and evidence. MPs can ask the analytical institutes for information for example on international best practices in a certain field. The Parliamentary Institute reports that in particular analysis from the financial, health and environment institutes is of high quality.

Training and guidance

Beyond the technical need for training in certain processes such as impact assessment or plain language drafting, training communicates the message to administrators that this is an important issue, recognised as such by the administrative and political hierarchy. It can be seen as a measure of the political commitment to Better Regulation. It also fosters a sense of ownership for reform initiatives, and enhances co-ordination and regulatory coherence.

Continuous training and capacity building within government, supported by adequate financial resources, contributes to the effective application of better regulation. In the Slovak Republic, targeted trainings on the application of regulatory management tools and guidance material pose challenges to an effective implementation of the better regulation agenda.

Up to this date, no trainings on better regulation topics, incl. RIA, are available to civil servants in the Slovak Republic. The RIA 2020 Strategy foresees the following training activities in Activity 1: Education and awareness-raising of public servants and other relevant entities on the process and content of impact assessment of regulatory frameworks and non-legislative proposals:

intensive 2-day workshops on RIA for state officials who draft regulations and RIA analysts few times a year,

1-day seminars on RIA with international experts for all officials participating on RIA process once a year,

1-day workshops on tools of BR for state officials a few times a year,

2-day workshops on RIA for the officials of from the ministries responsible for selected impacts,

2-day workshop for the RIA Commission members on internal processes and sharing experience,

1-day seminars for the public (including entrepreneurs and NGOs) on RIA tools and possibilities to take part in the process,

1-day seminars for MPs and their assistants on benefits and opportunities to use BR tools in Parliament,

1-day seminars for representatives of regions and municipalities on benefits and possibilities to use BR tools in their administrations.

The Ministry of Economy plans to hold a first training on pilot projects for the members of the working committee on ex post evaluation in the end of March 2020.

Staff in analytical units mentioned that they would welcome RIA trainings. These trainings would not only allow them to deepen their analytical skills to provide guidance and advice to ministry staff, they would also represent an opportunity to interact and potentially co-operate with staff from other analytical units.

The Ministry of Economy as a national co-ordinator of Better Regulation and the Department for Business Environment is responsible for the Unified Methodology and thus responsible for providing guidance material. Guidance material has so far been developed for a number of topics, i.e. conducting RIA and assessing regulatory alternatives. There are also different guidance documents available for consultations with entrepreneurs according to the Unified Methodology5 and with the general public,6 issued by the Office of the Plenipotentiary. The RIA 2020 Strategy foresees the development of a joint methodology by June 2020. Pilot testing of the new methodology should be carried out by the end of March 2021.

Assessment and recommendations

Within the Slovak government, the competencies for supporting regulatory quality are distributed among several key ministries and institutions. As is the case in many OECD countries, Slovakia has a fragmented institutional landscape for regulatory policy, and responsibilities for one oversight function are split among several authorities. The RIA Commission is responsible for overseeing the quality of regulatory impact assessments. The Legislative Council of the Government is in charge of reviewing the legal quality of government regulations and the compliance of legislation with EU-law. The Ministry of Economy co‑ordinates better regulation efforts across the administration and ensures the RIA process is carried out in line with the Unified Methodology. Lastly, the Ministry of Justice is responsible for co-ordinating the inter-ministerial commenting procedure. The distribution of competencies for supporting regulatory quality among several key ministries and institutions means that the current institutional set-up bears a risk of overlapping and unclear functions.

The regulatory oversight system’s methods and performance have scope for improvement. The RIA Commission as the regulatory oversight body brings together several ministries and other bodies for a comprehensive approach to RIA quality control. The insufficient quality of some RIA statements and compliance issues with the Commission’s opinions suggest that the oversight body’s methods and performance should be improved. Currently, the Commission only reviews the quality of individual impacts in the portfolio of individual institutions represented in the Commission and not the overall quality of the RIA and total impacts on the welfare of the society, including whether the overall benefits justify the potential costs stemming from regulatory drafts. The lack of overall quality review means the informative value of the RIA statement is diminished. Furthermore, the RIA commission usually only meets once a year and does not meet with the ministries sponsoring legislative drafts. This is a missed opportunity as meeting with ministries and providing continuous advice throughout the drafting process could significantly improve the RIA. Lastly, there are some key oversight functions the Commission does not cover. There is no body in charge of identifying areas of policy where regulation can be made more effective. This includes gathering opinions from stakeholders on areas in which regulatory costs are excessive and/or regulations fail to achieve its objectives and advocating for particular areas of reform. There is currently also no quality control carried out on the stakeholder engagement processes employed by line ministries.

The Ministry of Economy is well respected as the national co-ordinating body for better regulation, but strong leadership from the centre of government is missing. A key regulatory oversight function is fostering a whole-of-government perspective towards regulation and performing essential co-ordination activities to ensure a homogenous approach to regulatory policy across the public administration. In the Slovak Republic, the Ministry of Economy as the national co-ordinating body puts in place important better regulation reform efforts like the RIA 2020 Strategy and brings ministries together in the Unified Methodology Working Group for this purpose. However, as a line ministry the MoE might not have the authority necessary to promote better regulation as a topic of high political priority across the administration. The delay of the implementation of the RIA 2020 Strategy might partly be due to the lack of strong leadership for better regulation from the centre of government or an independent body with the power to enact change around the government.

The analytical units in some line ministries present a competitive advantage for the Slovak Republic and reflect international good practice. The institutes are specialised units operating within the portfolio of their ministry and serve to provide analytical background for the ministry’s decisions. Some institutes, like the Institute for Financial Policy, enjoy sufficient resources and analytically trained staff to support ministry staff with the RIA process. Their structures, competences and position in the organisation of the ministry however vary. Some institutes have only been established very recently and compared to other institutes still lack resources and overall capacities.

The existing analytical capacities in ministries are not used to full potential. The analytical institutes are a unique source of analytical capacities only in few line ministries. Particularly institutes that have been established recently are not involved in the impact assessment process and co-operation between institute and ministry staff does not happen on a systematic basis. The level of involvement in the decision making process is at the minister’s discretion, there is no formalised process in place.

The OECD Secretariat makes the following policy recommendations:

The Slovak Government should strengthen analytical capacities and promote the use of existing capacities in key ministries. This includes creating conditions to attract and keep sufficiently trained staff. The government should follow up on trainings planned as part of RIA 2020. Putting in place trainings on key regulatory management tools would not only improve analytical performance, but could also promote co-operation within ministries and among analytical institutes, bringing together key actors in regulatory policy. To make full use of existing capacities in analytical institutes, there should be efforts undertaken to formalise co-operation among institutes and ministries. The institutes should systematically provide advice and support to staff drafting laws and preparing RIAs.

Stronger leadership driving a concerted better regulation effort across the administration should be put in place. There should be a body with the authority to enact change around the government and to promote a co-ordinated whole-of-government approach to regulatory policy. This body might take the form of a ministerial committee chaired by the Minister of Economy or the Prime Minister, with the MoE’s Business Environment Department acting as secretariat. It could also be considered placing this co-ordination function in the centre of government, where the body might have the authority necessary to promote and co-ordinate better regulation reform efforts across the administration. In this respect, the newly appointed Deputy Prime Minister for legislation and strategic planning could play an important role. Should an arm’s length body for regulatory oversight be considered (see recommendation below), this body naturally should take on such a leadership function.

The methods and performance of the RIA Commission should be improved. The RIA Commission should meet with ministries at least four times a year, to provide continuous advice and support during the RIA preparation phase. To ensure the overall impacts of a legislation are considered, the RIA Commission should review the total impacts on the welfare of the society, including whether the overall benefits justify the potential costs stemming from regulatory drafts. The RIA commission’s secretariat should conduct a preliminary review of the RIA statements submitted and screen out problematic or particularly burdensome RIA statements for the Commission’s review. This practice could help ease the Commissions workload by targeting its efforts to RIA statements for the most burdensome pieces of legislation. In addition, the secretariat should have more staff allocated and should meet regularly with ministries to discuss RIA statements. It could be considered to place the secretariat within the center of government to elevate the regulatory policy agenda to a higher political level.

The Slovak Government could consider centralising regulatory oversight functions into one body and giving this oversight body stronger powers. The location of the oversight bodies is an important consideration. Where the responsibility for regulatory oversight is placed, i.e. within government or located in a body operating at arm’s length, clearly depends on the oversight function carried out:

Functions supporting a whole-of-government approach to regulatory policy through co-ordination, the provision of guidance and training or the overall systematic improvement and advocacy for regulatory policy are usually located within government. A clear mandate consolidating Better Regulation and oversight responsibilities at the centre of government would help promoting and implementing regulatory management policies through effective monitoring. Consolidating at least some of these powers in one unit close to the centre of government specifically in charge of regulatory management could improve co-ordination among existing ministries and agencies and would help ensure that regulatory quality principles are successfully applied.

For the quality control of regulatory management tools however it could be considered to place them in independent bodies external to government. The insufficient quality of some RIA statements and compliance issues with the RIA Commission’s opinions suggest a lack of authority across the administration. For this reason, several ministries and business representatives have argued in favour of transforming the RIA Commission into an “independent watchdog”. Such an independent body should be given stronger powers to be able to ensure RIA quality, like being able to stop legislation from going forward if the RIA quality is deemed insufficient.

References

[3] OECD (2019), OECD Economic Surveys: Slovak Republic 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-svk-2019-en.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[4] OECD (2015), Slovak Republic: Better Co-ordination for Better Policies, Services and Results, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/governance/slovak-republic-better-co-ordination-for-better-policies-services-and-results-9789264247635-en.htm (accessed on 19 December 2019).

[1] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022-en.

Notes

← 1. Available at https://www.mhsr.sk/podnikatelske-prostredie/jednotna-metodika/vykladove-stanoviska.

← 3. Available at https://www.government.gov.sk/statute-of-the-government-office-of-the-slovak-republic/.

← 4. Available at https://www.slov-lex.sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/1996/350/#.