Suicide is a significant cause of death in many OECD countries and accounted for over 154 000 deaths in 2020 (or the most recent year), which represents about 11 suicides per 100 000 people. The reasons for suicidal behaviour are complex, with multiple risk factors that can predispose people to attempt to take their own life. Mental ill-health can increase the risk of dying by suicide, as well as shocks such as pandemics, and financial crises.

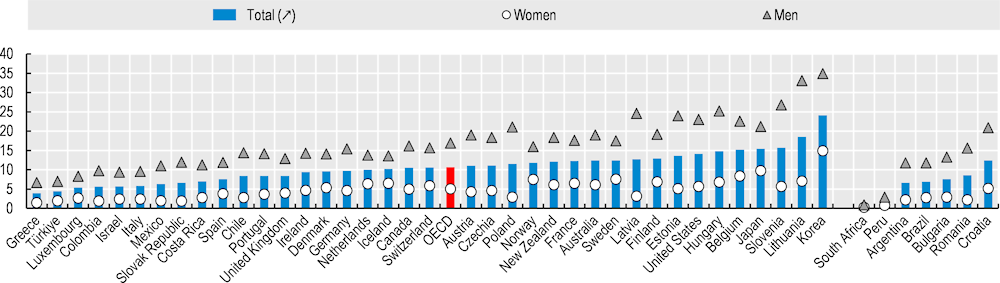

In 2021, among OECD countries, suicide rates were lowest in Greece and Türkiye, at 5 or fewer deaths per 100 000 population (Figure 7.4). In contrast, Belgium, Japan, Slovenia, Lithuania and Korea had more than 15 deaths per 100 000 people caused by suicide.

While average suicide rates vary widely across OECD countries, they are always higher for men than for women (Figure 7.4). In Latvia and Poland, men are at least seven times more likely to die by suicide than women. While the gender gap is smaller in Iceland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, suicide rates among men are still at least twice as high as among women.

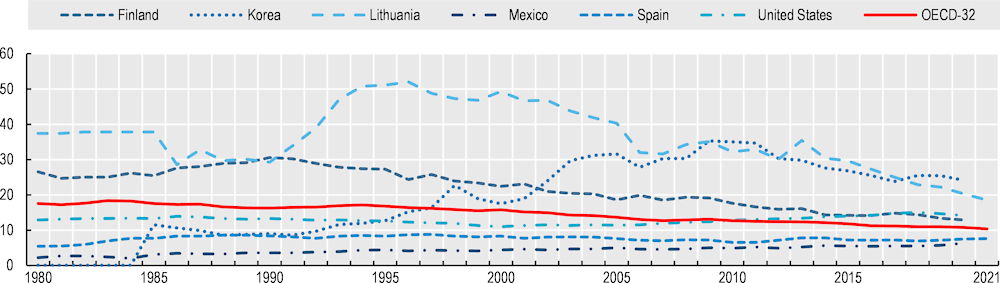

On average across OECD countries, suicide rates peaked during the early 1980s (Figure 7.5). Since the mid‑1980s, suicide rates decreased, with pronounced declines in Denmark, Luxembourg and Hungary. At the same time, suicide rates increased in Korea and Mexico. In Korea there was a sharp rise of average suicide rates in the mid- to late 1990s, coinciding with the Asian financial crisis, while rates have started to decline in more recent years. In Mexico, suicide rates have always been among the lowest across OECD countries and, although they remain low, they have increased since the 1980s.

In other countries, suicide rates have increased in the past decade. For instance, in Türkiye, suicide rates almost doubled from 2.4 per 100 000 in 2010 to 4.4 in 2019, in the United Kingdom they increased from 6.7 in 2010 to 8.4 in 2020; and similar trends can be observed in Chile, Greece and Spain. Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are good examples of countries that have achieved significant reductions in suicide rates over the past decades, although they remain high at over 10 deaths per 100 000 people.

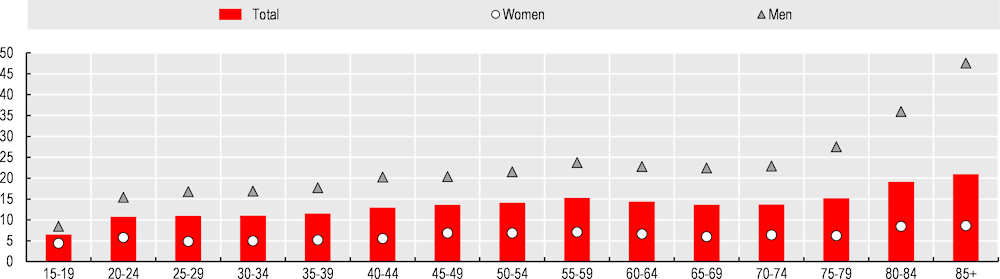

On average, older people are more likely to take their own lives, with 18 people per 100 000 aged 75 years or more, compared to 10 suicides per 100 000 for people aged between 15 and 29 (Figure 7.6). The largest age gap in suicides is found in France and Portugal, where the average suicide rates of people aged 75 or more are 9 times higher than for teenagers (aged 15‑19). In a minority of OECD countries like Costa Rica, Iceland, Ireland, Mexico and New Zealand, teenagers are more likely to take their own lives than older people. This is also the case in Peru and South Africa. Suicide rates among under 30s are the highest in Korea, New Zealand, Japan and Estonia with 17 or more suicides per 100 000 youth. The rates are lowest in Mediterranean European countries, Israel and Luxembourg.

Differences in suicide rates between men and women become particularly considerable at older ages, mainly after 75 years old, where suicide rates are almost 7 times greater for men than for women on average across OECD countries. This worldwide pattern may reflect relatively high social isolation of older men compared to older women.