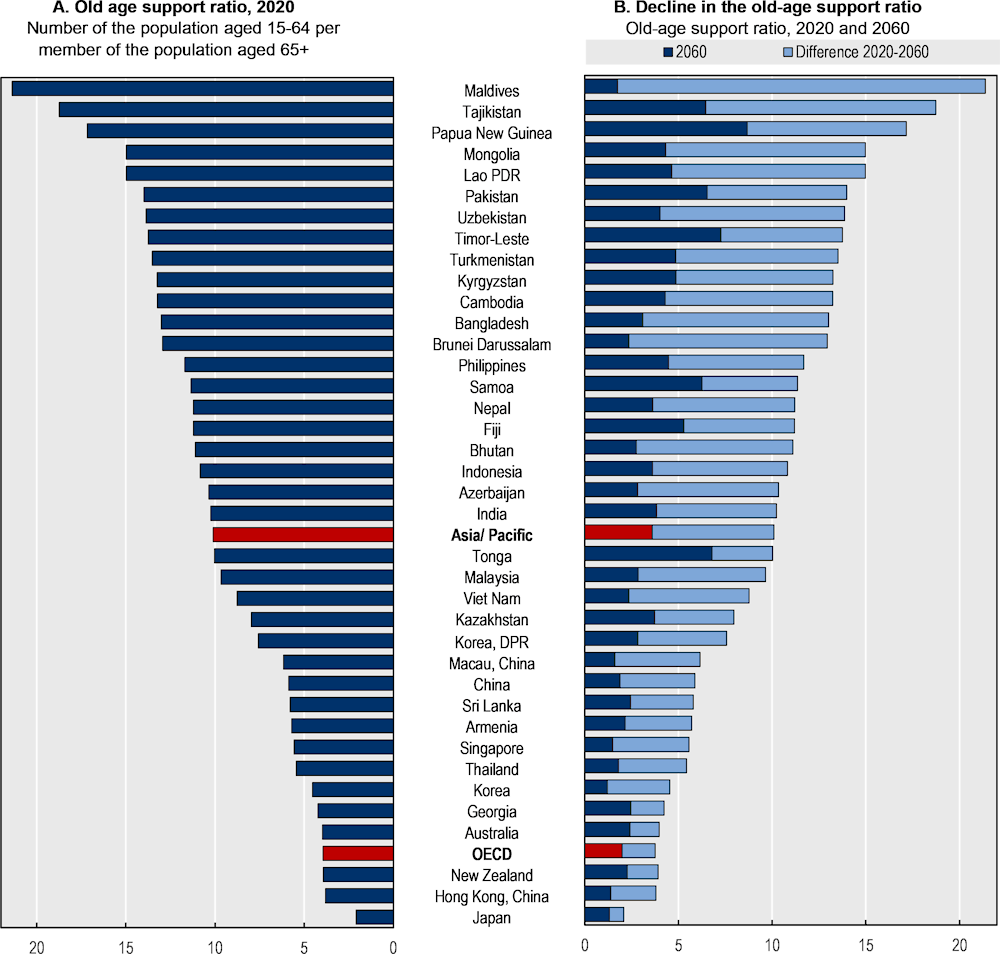

In 2020, countries in the Asia/Pacific region on average had ten people of working age for every person over 65 (Figure 2.13 Panel A). This is more than twice as high as the OECD average. The Maldives, Tajikistan and Papua New Guinea top the list with at least 17 working-age persons per one person over 65: a stark contrast to Japan’s 1:2 ratio. Within the Asia/Pacific region, OECD countries such as Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand have the lowest old-age support ratios: in these countries life expectancy is high (Figure 5.1), while fertility rates are low, particularly in Japan and Korea (Figure 2.4).

Old-age support ratios are projected to more than halve by 2060 (Figure 2.13 Panel B), and the Maldives, Mongolia and Tajikistan are expected to see the biggest declines. Four OECD countries in the region already have low old-age support ratios and these will decline further, in particular in Korea, from 4.5 in 2020 to 1.2 persons of working age to 1 senior citizen in 2060. Other economies in the region will also experience rapidly ageing societies. For example, the old-age support ratio in Brunei Darussalam will decrease from 12.9 in 2020 to 2.4 in 2060, and in Hong Kong, China (China) and Singapore, the old-age support ratios are projected to fall to 1.4 and 1.5 respectively by 2060, well below the OECD average of 2.0.

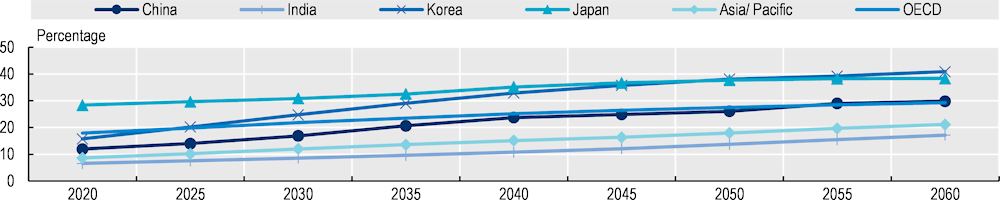

The upward trend in elderly population stems from a rise in life expectancy due to improved health and declining birth rates. Underlying projected demographic trends do differ across countries (Figure 2.14), but the proportion of people aged 65 and over is estimated to at least double in most economies between 2020 and 2060. By 2060 it is estimated that at least 20% of the population in Asia/Pacific economies will be aged 65 or older. By 2060 over 40% of the population in Korea is estimated to 65 or older, the highest proportion of all countries in the region.

There are economic and social implications of demographic change. A low old-age support ratio provides some indication of the “dependency burden on the working population, as it is assumed that the economically active proportion of the population will need to provide health, education, pension, and social security benefits for the inactive population, either directly through family support mechanisms or indirectly through taxation.