This introductory chapter describes the conceptual framework used in this report to assess factors influencing FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs and to identify opportunities for policies and institutional arrangements enhancing such spillovers. The chapter concludes by outlining how this conceptual framework is applied to the case of the Slovak Republic.

Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in the Slovak Republic

1. Scope of FDI spillovers on SMEs: Conceptual framework

Abstract

1.1. Context and motivation

Foreign direct investment (FDI) is an important source of finance for developed and developing countries and can play an important role in supporting a resilient and sustainable recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis. Harnessing FDI for sustainable development, and particularly productivity and innovation, requires strong linkages with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in host countries. Foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) do not just choose countries but locations in specific sub-national regions, and hence, FDI-SME linkages need to be considered and strengthened through place-based approaches.

SMEs contribute significantly to economic growth and social inclusion, and they can also play a key role in building resilience and more sustainable growth during the post COVID-19 recovery. In the OECD area, SMEs account for almost all enterprises, about two-thirds of total employment and 50-60% of value added (OECD, 2021[1]). To achieve their full potential, SMEs need to increase productivity and scale up innovation capacity. They are often less productive and innovative than larger firms where size is often identified as a major barrier to higher performance. Yet, some SMEs can be more productive and innovative than large firms, signalling that size is no fatality. In digital-intensive sectors, for example, smaller firms can show higher productivity levels (OECD, 2019[2]). SMEs play a key role in shifting innovation models by adapting supply to different contexts or user needs and responding to new or niche demand (OECD, 2018[3]).

Changes in the global trading and investment environment offer new opportunities for SME upgrading. Participation in global value chains (GVCs) enables SMEs to enhance productivity by absorbing technology and knowledge spillovers, upgrading workforce and managerial skills and raising innovation capacity (OECD, 2018[3]). This can be achieved by linking their business activities with foreign affiliates of MNEs (and domestic owned companies) and/or by directly integrating in GVCs as exporters, i.e. by supplying companies located abroad.

In this context, beyond the contribution to capital investment and employment generation, FDI can play an important role for knowledge and technology spillovers in host economies, resulting in increased productivity of local firms, especially SMEs. While productivity and innovation capacity of SMEs are influenced by a variety of market, policy and other factors (OECD, 2019[2]; OECD, 2021[1]), this report focuses on the specific role of FDI and related policies in the Slovak Republic. This introductory chapter introduces the conceptual framework to assess FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs and outlines how this framework is implemented for the case of the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2022, forthcoming[4]).1

1.2. Conceptual framework to assess FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs

Spillovers from FDI on domestic SMEs depend on a set of main enabling factors:

Potential for FDI spillovers: FDI spillovers are possible as foreign firms are often more productive than domestic ones. Foreign MNEs are often larger than domestic firms, where size is found to be associated with higher productivity and a key determinant to overcome fixed costs for investment abroad (Helpman, Melitz and Yeaple, 2004[5]). Affiliates of foreign firms – through their links with parent companies – have typically greater access to technology, better managerial skills and more adequate resources for capital investment than domestic firms (Alfaro and Chen, 2012[6]). These capacity differences between foreign and domestic firms make it possible for SMEs to benefit from knowledge and technology transfers. The potential for FDI spillovers is further influenced by the volume of FDI inflows (i.e. the economy’s relative dependence on FDI) and a number of FDI characteristics that illustrate to what extent FDI is effectively embedded in the local economy. These characteristics include (a) the sector in which the investment occurs and the activities that the foreign company undertakes, (b) the main motivations behind the FDI decision (e.g. market‑seeking, resource-seeking, asset-seeking, efficiency-seeking), (c) the type of FDI (e.g. greenfield versus mergers and acquisitions), (d) the country of origin of the foreign investor, including the geographical and cultural proximity to the receiving country and the degree of foreign ownership.2

Absorptive capacities of local SMEs: Absorptive capacity refers to the ability of a firm to recognise valuable new knowledge and integrate it productively in its processes, i.e. to innovate (OECD, 2021[1]; 2019[2]). The stronger its absorptive and innovative capacity, the higher its chances to benefit from FDI. SME absorptive capacity depends on the firm’s prior capital endowment and level of productivity, i.e. its level of financial, human and knowledge-based capital and its efficiency in creating value from it. Beyond existing endowments of these resources, absorptive capacity also depends on SMEs’ ability to access strategic assets related to finance, skills and innovation as well as on the broader business environment. Not all SMEs are the same and their heterogeneity greatly contributes to explain their performance. SMEs vary in terms of age, size, business model, market orientation, sector and geographical area of operation. This means that different types of SMEs have different growth trajectories and therefore different chances to enter into knowledge sharing relationships with foreign multinational enterprises (MNEs) and to benefit from FDI spillovers.

Economic geography factors: This refers to geographical and cultural proximity factors, where the latter is defined by factors such as the differences between home and host countries in terms of language, culture, political systems, level of education, and level of industrial development (Johanson and Vahlne, 1977[7]). The localised nature of FDI means that geographical and cultural proximity between foreign and domestic firms affects the likelihood of knowledge spillovers, which often involve tacit knowledge, and whose strength decays with distance. Thus, productivity spillovers from FDI on local firms are often concentrated in the same region of the investment. Agglomeration effects, notably through the presence of local industrial clusters, have also been reported to affect FDI attraction and FDI spillovers. Clusters embed characteristics such as industrial specialisation (through specialised skilled workers and suppliers) and geographical proximity that make knowledge spillovers more likely to happen, including from MNE operations.

Other economic and structural characteristics of the host country: The degree to which FDI-SME spillovers materialise also depends on other economic and structural characteristics of the host country and its sub-national regions. These factors relate to the regional/national endowment as well as the macro-economic context, structure of the economy, sectoral drivers of growth, productivity and innovation as well as to the level of integration in the global economy, beyond FDI. These factors are often necessary conditions for FDI spillover potential, SME absorptive capacity and economic geography factors to turn into actual productivity gains for domestic SMEs.

While adequate enabling conditions are necessary, FDI spillovers only occur if domestic SMEs are exposed to MNE activities. Such exposure may occur through a set of diffusion channels:

Value chain linkages involve knowledge spillover from foreign MNEs to suppliers (upstream) and customers (downstream). Linkages help domestic companies extend their market for selling and raise the quality and competitiveness of their outputs. They can also generate knowledge spillovers when MNEs require better-quality inputs from local suppliers, particularly SMEs, and are therefore willing to share knowledge and technology with domestic companies to encourage their adoption of better practices.

Strategic partnerships involve knowledge and capacity transfer in formal collaborations, for example in the area of R&D or workforce/managerial skills upgrading. These partnerships can take many forms, including joint ventures, licensing agreements, research collaborations, globalised business networks (i.e. membership-based business organisations, trade associations, stakeholder networks), and R&D and technology alliances.

Labour mobility can be an important source of knowledge spillovers in the context of FDI, notably through the move of MNE workers to local SMEs – either through temporary arrangements such as detachments or long-term arrangements such as open-ended contracts – or through the creation of start-ups (i.e. corporate spin-offs) by (former) MNE workers. Firms established by MNE managers are often more productive than other local firms. Similarly, workers who moved from foreign-owned to domestic firms retain skills and competences, including management skills, acquired in the foreign firms and thus contribute more to the productivity of their firm than workers without foreign firm experience.

Competition effects occur with the entry of foreign firms, which heightens the level of competition on domestic companies and puts pressure on them to become more innovative and productive – not least to retain skilled workers. The new standards set by foreign firms – in terms of product design, quality control or speed of delivery – can stimulate technical change, the introduction of new products, and the adoption of new management practices in local companies, all of which are possible sources of productivity growth. This rising competitive pressure due to foreign firm entry and related productivity spillovers may also be associated with new incentives for workers to improve skills and SMEs to engage in skills upgrading.

Imitation effects occur when foreign firms can also become a source of emulation for local companies, for example by showing better management practices. Imitation, reverse engineering and tacit learning can therefore become a channel to strengthen enterprise productivity at the local level. Foreign firms may also participate in innovation clusters and collaborative innovation activities where cross-fertilisation of ideas can increase productivity, both of domestic and foreign firms.

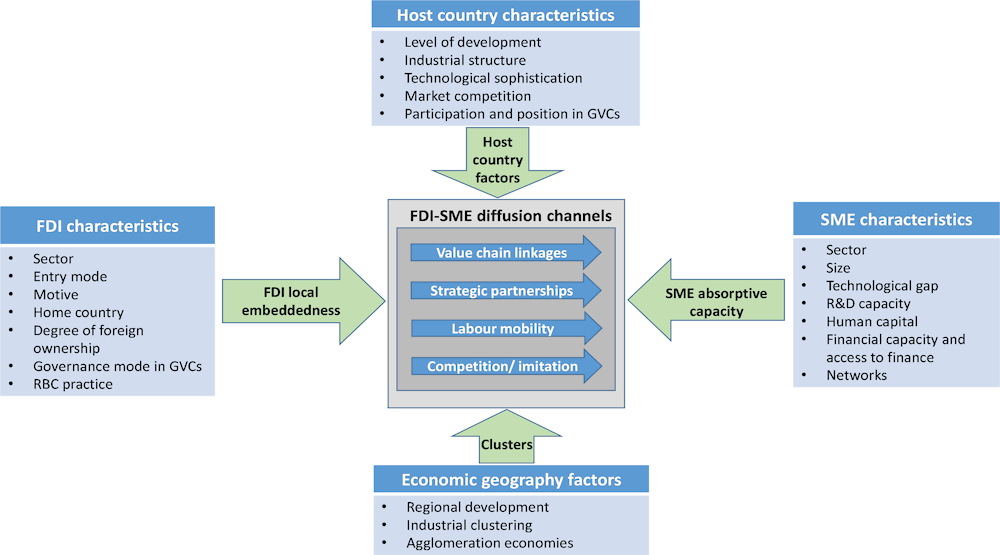

The scope for productivity and innovation spillovers on domestic SMEs is ultimately determined by the interaction of enabling factors and diffusion channels (Figure 1.1). Public policies aiming to enhance these spillovers address these different aspects and cut across a range of policy domains, including investment policy and promotion, SME development, innovation and regional development.

Figure 1.1. Understanding FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs: Conceptual framework

Source: OECD (2022, forthcoming[4]), Enabling FDI diffusion channels to boost SME productivity and innovation in EU countries and regions: Towards a Policy Toolkit. Revised Concept Paper.

1.3. Implementing the conceptual framework in this report

The next chapter assesses enabling conditions for FDI-SME diffusion in the Slovak Republic. It first looks at the Slovak Republic’s economic context and integration in the global economy and then focuses on the potential for FDI spillovers, SME absorptive capacities and economic geography factors related to FDI and SME development. Whether or not FDI-SME diffusion channels are at play in the Slovak Republic is at the centre of discussion in this report and examined in Chapter 3.

Building on the diagnostic assessment of enabling conditions and channels of FDI-SME diffusion, the next two chapters focus on the institutional and governance framework (Chapter 4) and policy mix (Chapter 5) for FDI diffusion on SME productivity and innovation in the Slovak Republic. Chapter 4 provides an overview of the institutions that are currently in place to design and implement FDI, SME and entrepreneurship, innovation and regional development policies, and explores the multilevel policy coordination mechanisms to ensure coherence across policy domains, institutions and tiers of government. The chapter also looks at the monitoring and evaluation framework for policies related to FDI-SME diffusion in the Slovak Republic, and efforts to enhance stakeholder engagement. Chapter 5 reviews the mix of policies in place for fostering FDI spillovers on the productivity and innovation of Slovak SMEs. Closely following the conceptual framework, it identifies the FDI-SME diffusion channels and enabling factors that are supported by the Slovak Republic’s policy framework, and the policy instruments used to promote FDI‑SME linkages, noting areas for further policy development or a shift in the policy mix.

The last chapter examines the geographic and regional dimension relevant for FDI investments and its spillovers with the local and regional economy. The chapter also explores the role of subnational policies to complement national FDI and SME policies by examining two Slovak regions, Banská Bystrica and Košice, as case studies.

References

[6] Alfaro, L. and M. Chen (2012), “Surviving the Global Financial Crisis: Foreign Ownership and Establishment Performance”, American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, Vol. 4(3): 30-55.

[8] Castro, F. (2000), Foreign direct investment in the European periphery: The competitiveness of Portugal, The University of Leeds, https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/2612/1/Castro_FB_LUBS_PhD_2000.pdf.

[5] Helpman, E., M. Melitz and S. Yeaple (2004), “Export Versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms”, American Economic Review, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/melitz/files/exportsvsfdi_aer.pdf.

[7] Johanson, J. and J. Vahlne (1977), “The internationalization process of the firm - A model of knowledge development and increasing market commitments”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. Vol. 8, No. 1.

[1] OECD (2021), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/97a5bbfe-en.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d2b72934-en.

[3] OECD (2018), Promoting innovation in established SMEs, OECD SME Ministerial Conference, Mexico City, Policy Note, 22-23 February 2018, http://www.oecd.org/cfe/smes/ministerial/documents/2018-SME-Ministerial-Conference-Parallel-Session-4.pdf.

[4] OECD (2022, forthcoming), Enabling FDI diffusion channels to boost SME productivity and innovation in EU countries and regions: Towards a Policy Toolkit. Revised Concept Paper, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Notes

← 1. This conceptual framework has been developed as part of OECD-European Commission’s cooperation on supporting EU Member States to harness FDI spillovers on SME productivity and innovation and its long version, including a review of literature, can be consulted at OECD (OECD, 2022, forthcoming[4]). Findings will contribute to OECD Investment Committee’s FDI Qualities Initiative and the work on “Global value chains (GVCs): Seizing the opportunities for SMEs” of the OECD Committee on SMEs and Entrepreneurship.

← 2. See (OECD, 2022, forthcoming[4]) and Castro (2000[8]) for a review of the literature.