This chapter discusses recent policy developments to enhance both quality and equity in education for all students in the country. It presents and discusses general and targeted policies, such as those providing universal access to education, or more targeted measures to support disadvantaged students and population groups, as well as investments in school infrastructure. It assesses the extent to which these align to international good practice and have contributed to greater equity in education. After reviewing remaining challenges, it provides policy insights that can help Mexico to continue on its path to close the equity gap in education and raise its overall quality.

Strong Foundations for Quality and Equity in Mexican Schools

Chapter 2. Providing equity with quality in Mexican education

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

Among the key objectives of education systems across the world is attaining quality learning for all their students. This entails ensuring that all children have the opportunity to learn and reach their potential, that they have high-quality content and are prepared for their future. Ensuring equity while aiming for high-quality education has been a concern of many education stakeholders in Mexico.

To mark its commitment to enhancing its education services for all, Mexico enshrined the right of all students to an education of quality in its General Law of Education (see Box 2.1). The state must therefore ensure the conditions that allow all students to achieve their learning potential. Efforts encompass a wide range of programmes focused on responding to students’ different needs, especially helping the most disadvantaged (such as PROSPERA, Consejo Nacional de Fomento Educativo (CONAFE) or others for indigenous populations) as well as investing in school infrastructure (such as the programme Escuelas al CIEN [ECIEN] and the Education Reform Programme (Programa de la Reforma Educativa, PRE). The recent strategy for equity and inclusion in education (Estrategia para la Equidad y la Inclusion en la Educación, formalised in the New Educational Model, 2017) made some efforts to build some coherence among these programmes. Overall, the country has laid some of the necessary bases for all students to learn in safe, sanitary and learning-friendly environments.

This chapter analyses recent policies in line with Mexico’s constitutional mandate of enhancing both quality and equity in education for all students to succeed in the country. More concretely, this chapter:

Offers an overview of equity issues in Mexico, considering equity in terms of fairness and inclusion.

Discusses the importance of offering universal access to an education of quality.

Explains the importance of guaranteeing both equitable resources in education and a basic capacity for schools to respond to the needs of their learners.

Analyses the importance of reinforcing coherence among a range of targeted programmes for disadvantaged populations.

Emphasises the relevance of providing for all student safe environments that are adequate to learning.

To do so, this chapter is divided into three sections. Following this introduction, the first section discusses to what extent the reform aims to improve equity in education. A second section discusses progress in this area analysing multiple programmes and resources Mexico has devoted to ensuring equity in the provision of public services, including education. The chapter concludes with a section that reflects on remaining challenges in terms of equity and proposes recommendations to address them.

Policy issue: Provide equity with quality in education in Mexico

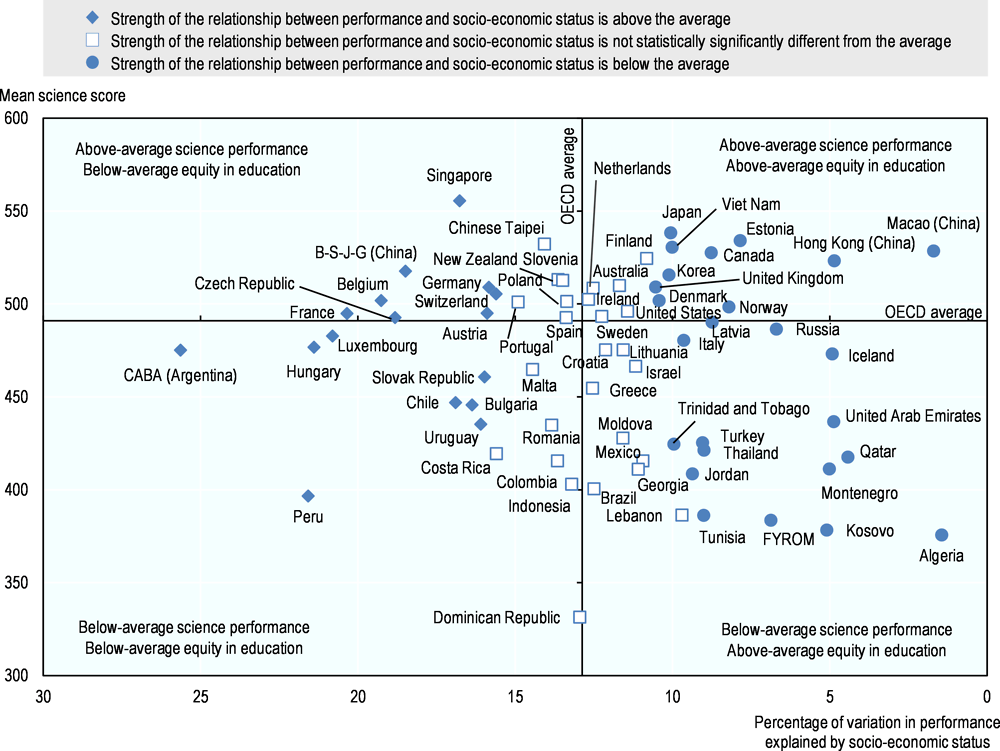

High-performing education systems have recognised that quality in education requires combining quality with equity, meaning that there is no quality without equity (Figure 2.1). Providing equity in education means taking into account the fact that all students do not have the same opportunities to complete or do well in school, and then organising educational services to address this issue. It means that personal or social circumstances such as gender, ethnic origin or family background, are not obstacles to achieving educational potential (fairness) and that all individuals reach at least a basic minimum level of skills (inclusion) (OECD, 2012[1]). This requires the recognition that not all students are the same, and therefore in addition to having equity as a system-level priority, carefully targeting resources can ensure more support economically, socially or geographically to the more disadvantaged. In addition, setting high expectations for all students is a policy that can also contribute to the objective of inclusion. Mexico is targeting equity with quality in education through the policies reviewed in this chapter and through the curriculum reform covered in Chapter 3.

Figure 2.1. Science performance and equity, PISA 2015

Notes: B-S-J-G (China) refers to the four PISA-participating China provinces: Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Guangdong.

FYROM refers to the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Argentina.

Only data for the adjudicated region of Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires (CABA) are reported.

Source: OECD (2016[2]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en.

Improving equity in a challenging context

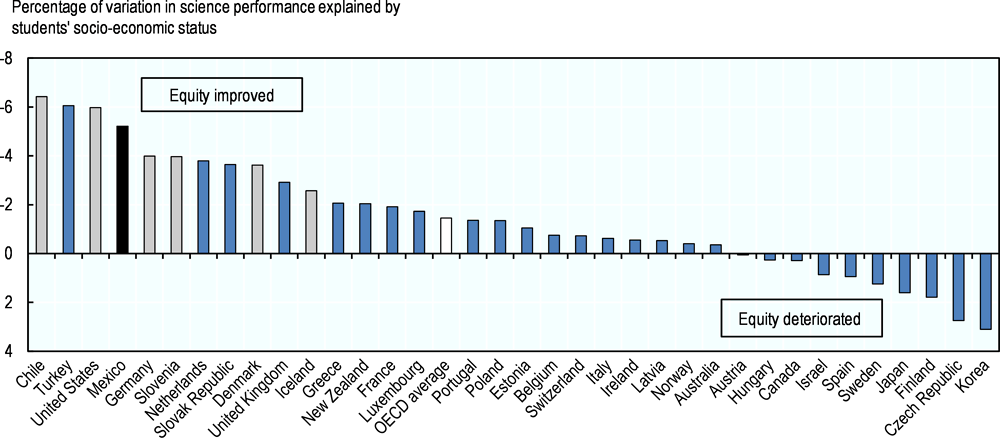

Overall, equity in education has been improving in Mexico, even if there is room for improvement (as in most countries). In terms of learning outcomes, the impact of students’ economic, social and cultural status on their performance in science decreased from 2006 to 2015 for 15-year-olds, according to PISA (OECD, 2016[2]). The country is among those where equity has improved the most between 2006 and 2015. Figure 2.2 displays the change in the impact of socio-economic status on students’ science performance in PISA, in which Mexico comes 6th among countries where equity improved.

Figure 2.2. Change in the percentage of the variation in science performance explained by socio-economic status, PISA 2006‑15

Note: Values that are statistically significant are indicated in light grey and in black (for Mexico).

Source: OECD (2016[2]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education,

The improvement in equity shown for Mexico in Figure 2.1 and Figure 2.2 should be considered cautiously, however. Indeed, PISA can only capture the results of the youth who are in school at age 15 and does not consider the more than 40% of the 15‑17 year‑old age group who were not enrolled in school in Mexico in 2015. Also, systematic differences associated with students’ and schools’ characteristics remain, which prevent granting access to quality education, providing the means to learn and ensuring equal learning opportunities for all.

Disadvantaged students in Mexico are overrepresented among low performers, a similar trend to other OECD countries. In PISA, Mexico’s disadvantaged students are more than twice as likely to be low performers in science as compared to non-disadvantaged students, and more than three times as likely in mathematics, which is around the OECD average. In reading, the difference is starker since disadvantaged students are more than four times as likely to be low performers than non-disadvantaged students. Like in other Latin American countries (except Chile), the socio-economic status reduces the chances for Mexican disadvantaged students to achieve at high levels, to a greater extent than it protects advantaged students from relatively low levels of performance (OECD, 2016[2]). Data from the national standardised tests PLANEA show systematic and large differences in students’ performance: for instance, at the end of lower secondary education, students with an indigenous background score consistently lower than their non-indigenous classmates in mathematics. The number of students who score “insufficient” on PLANEA (Level I) is much higher in smaller and more marginalised localities: these very low achievers represent 61.8% of students in highly marginalised areas, compared with only 34.2% of the students in non-marginalised areas (SEP, 2018[3]).

The education system in Mexico is one of the largest across OECD and extremely diverse: in 2016‑17, 225 757 schools of basic education attended to the needs of 25.8 million students (data provided by the Secretariat of Public Education [Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP] to the OECD). As outlined in the constitution (Article 3) and in the country’s education vision embodied in the document Los Fines de la Educación en el Siglo XXI (see Box 3.2 in Chapter 3 of this report), the system must provide high-quality education to all young Mexicans (SEP, 2017[4]). Yet the diversity in students’ and in schools’ contexts and conditions mean students may have different learning needs in order to achieve their potential. This can lead to unequal educational outcomes if this diversity in needs is left unattended. Among factors that contribute to inequality in education in Mexico, the following can be emphasised:

Socio‑economic deprivations: overall, socio-economic inequalities are high in Mexico. The country’s Gini index of 43.4 places it among the most unequal countries in the OECD in 2016 (The World Bank, 2016[5]). Inequalities are even starker between the top and the bottom deciles, for the richest 10% earn 21 times more than the poorest 10% (OECD, 2016[6]). Despite the decrease in the impact of students’ socio-economic status on their PISA results, the socio-economic gradient is still strong on educational outcomes as well. For instance, it is estimated that students from wealthier backgrounds are close to three times more likely to finish upper secondary education than their less privileged peers. This is an encouraging decrease from the factor of 5.5 in 2000 (OECD, 2016[6]). The overall attainment rate of 37% for upper secondary education among adults aged 25-64 is still much lower than the OECD average of 74%, however (OECD, 2017[7]).

Ethnicity and languages: the indigenous population makes up 12% of the Mexican population in 2018 and 6.5% speak one of the 68 indigenous languages. 9 out of 10 indigenous people live in high or very high marginalisation,1 and 8 out of 10 live in poverty (INEE, 2018[8]). Non-indigenous students hold a steady advantage, as they have been almost twice as likely to complete upper secondary education as indigenous students between 2010 and 2014 (El Colegio de México, 2018[9]). Results on PLANEA also show that students of indigenous background often score lower than those from non-indigenous backgrounds (SEP, 2017[10]).

Accumulation of risk factors in marginalised areas: in Mexico like in other Latin American countries, inequalities tend to accumulate, a vicious cycle that both affects and is worsened itself by education inequalities (OECD, 2017[11]). The latest PISA results showed that the variation in performance between Mexican schools is strongly associated with their students’ socio-economic background (OECD, 2018[12]). The states of Chiapas, Guerrero, Michoacán, Oaxaca and Veracruz, which all lag behind in educational outcomes, also share high levels of poverty (INEGI, 2016[13]; CONEVAL, 2016[14]). Living in a rural area has made a student at least twice less likely to complete upper secondary education than an urban student since 2005 (El Colegio de México, 2018[9]). It is acknowledged that students in marginalised areas – including rural, remote, poorer regions – usually attend schools that accumulate deficiencies (SEP, 2017[10]). For instance, the states of Chiapas, Durango and Zacatecas had a high proportion of multigrade schools (multigrado) compared with the national average of 44% (SEP, 2017[10]; Vásquez et al., 2015[15]).

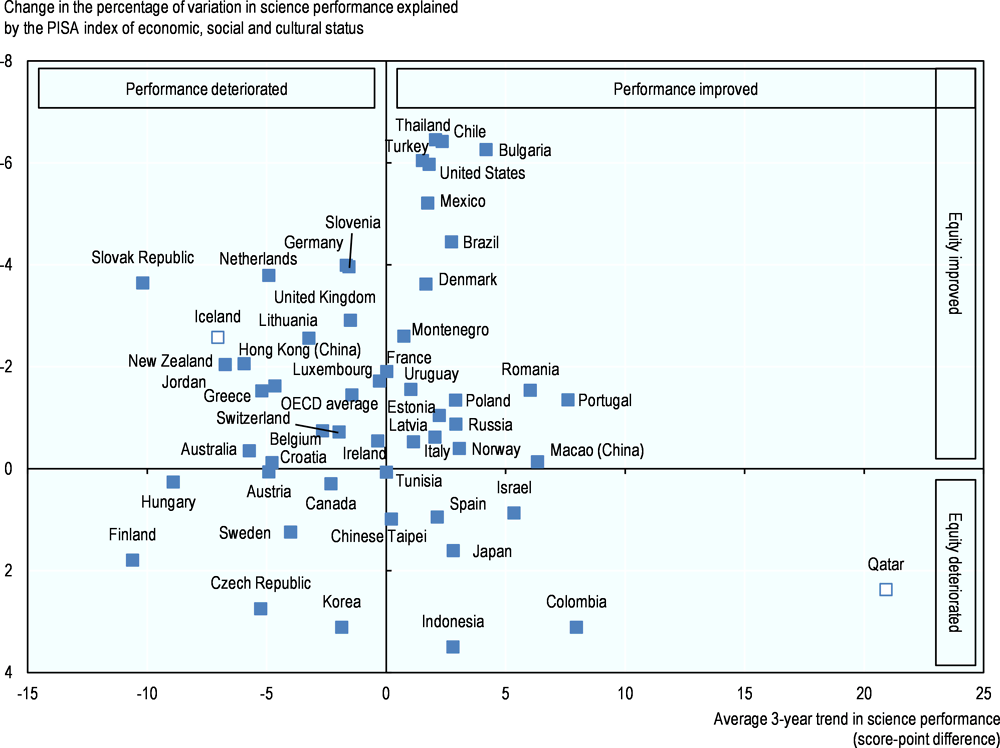

Mexico has been undertaking and reinforcing measures to support equity with quality for all students, shown in progress in enrolment, completion and achievement, and further policy investments can be made over the longer term. International evidence points out that equity in education does not need come at the expense of student performance. PISA results show that, between 2006 and 2015, the strength of the socio-economic gradient weakened in a number of countries that also managed to maintain their average performance in science, including in Mexico (OECD, 2016[2]). These countries are displayed in the top right corner in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3. Enhancing equity in education while maintaining average performance in science, PISA 2006‑15

Note: Changes in both equity and performance between 2006 and 2015 that are statistically significant are indicated in white.

Source: OECD (2016[2]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education,

Investing in early, primary and secondary education for all and with particular attention to children from disadvantaged backgrounds is both fair and economically efficient (OECD, 2012[1]). According to one estimate, if all 15-year-olds in the OECD area attained at least Level 2 in the PISA mathematics assessment, they would contribute over USD 200 trillion in addition to economic output over their working life (OECD, 2010[16]).

Countries invest in equity through general interventions that aim to benefit all students with a strong equity perspective or by investing directly in specific subgroups or schools where disadvantage prevails (OECD, 2015[17]). Similarly, Mexico has adopted key policy measures directed towards enhancing equity in education, including system-wide policies and targeted programmes to sustain equity, which it has been trying to approach through a coherent strategy for equity and inclusion. These different measures show the importance Mexico has given to policies that target equity for all students across the country.

Aiming for excellence in education translates into achieving both equity and quality for all students. This dual goal requires general and specific policy focus. Students vary in terms of their economic and social background, their ethnic and cultural origins, or in the place they live, and often the more deprived have poorer educational outcomes. Their specific situation needs to be taken into account when providing education, as these students are at greater risk of not completing their education than students who are more privileged (OECD, 2012[1]). As Mexico progresses toward better quality with more equity in education, the country faces two challenges: providing equitable opportunities (i.e. granting more support to the most disadvantaged) and establishing equity as a guiding principle and effectively putting it into action in current and upcoming policies.

Mexico’s recent system-wide policies to sustain equity in education include:

The inscription in the law of the right of all to an education of quality and the emphasis on the role of equity as a key component of education quality (Article 3 of the Political Constitution of the United States of Mexico, Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2013; and Articles 2, 3 and 8 of the General Law of Education, Ley General de la Educación, 2013‑17).

The obligation to observe the superior right of the child is enshrined in the Constitution (Article 4) and reiterated with an explicit mention to equity in the General Law on the Rights of Girls, Boys and Teenagers (Ley General de los Derechos de Niñas, Niños y Adolescentes, 2014).

The extension of compulsory education to upper secondary level (Educación Media Superior Obligatoria, 2012) and the Movement against School Dropout (Movimiento Contra el Abandono Escolar, 2013).

The establishment of minimum standards for school operations (Normalidad Mínima de Operación Escolar, 2014).

The expansion of the Full-day Schooling model (Escuelas de Tiempo Completo, ETC, 2006).

The country has also developed a considerable number of targeted programmes to cope with inequalities in education. Recently, Mexico has been searching to enhance the coherence between system-wide policies as well as targeted programmes thanks to the new Strategy for Equity and Inclusion in the New Educational Model (Estrategia para la Equidad y la Inclusion en la Educación, 2017). The main programmes include:

Federal scholarship programmes for low-income populations.

The conditional cash transfer programme PROSPERA, 2014.

An educational model adapted to marginalised areas’ challenges (CONAFE’s ABCD model, Aprendizaje Basado en la Colaboración y el Diálogo, 2016).

With these policies, the country seeks to guarantee that schools provide all students with a school environment that is conducive to learning. In its context of great disparities between schools, a key issue is to make sure that the school infrastructure (i.e. the buildings) exists, that it is safe and sanitary, and that schools have at least the basic means to function as educational institutions. The recent efforts made in this area are analysed in specific sections including:

The CEMABE (Censo de Escuelas, Maestros y Alumnos de Educación Básica y Especial, 2013).

The Education Reform Programme of Investment (Programa de la Reforma Educativa, PRE 2014-18).

The School at CIEN investment programme (Escuelas al CIEN, Certificados de Infrastructura Educativa Nacional, 2015-18).

Offering universal access to an education of quality

Mexico has bound its state with the obligation to provide an education of quality, understood as an education that enables all its students to reach their full learning potential. Key abstracts from the Mexican legislation on equity in education are summarised in Box 2.1. Strengthening this statement of purpose, Article 8 of the General Law of Education (Ley General de la Educación, LGE) defines the quality of education in terms of effectiveness, efficiency, relevance and equity, all of which the education system’s objectives, results and processes must comply with. Equity has thus become a core component of the Mexican definition of quality in education, which means that progress in each education outcome should be assessed not only in terms of performance but also through the lens of equity. Equity is considered in terms of access (all children should have an equal access to education), of resources and quality of educational processes (once in schools, all children should benefit from the means necessary for them to learn), and in terms of learning results (once in schools, all children should have the same opportunities to attain high standards of learning and complete their education).

In order to respond to its mandate, the Mexican education system must ensure that students are in schools where they can receive an education of quality. The first issue is to make sure that students are enrolled in schools to get the education they need. Across OECD countries, an average of 77.8% of 3-year-olds are enrolled in either early childhood or pre-primary education, 100% of 5‑14 year-olds are enrolled in primary and lower secondary education and 85% of 15-19 year-olds are enrolled in upper secondary education. In Mexico, these proportions have improved between 2010 and 2015 but remain below the OECD average, with enrolment for 3-year-olds moving from 44% in 2010 to almost 46% in 2015, and that of the 15-19 year-old age group from 54% to 57% (OECD, 2017[7]).

First, early childhood education and care (ECEC) has been demonstrated to be effective to improve educational outcomes over the long run, as well as to be an efficient approach to prevent later dropout. ECEC usually encompasses both the programmes aimed at children aged 0 to 3 and the programmes for children aged 3 to the official primary school entrance age (OECD, 2017[18]). In Mexico, ECEC refers only to initial education (educación inicial, ages 0 to 3), while pre-school or pre-primary school (educación preescolar, ages 3 to 5) is considered as part of basic education (educación básica). For comparative purposes, this report will use “ECEC” to refer to all educational services for children aged 0 to 5 (thus including educación inicial and preescolar). Mexico has expanded access from ECEC to upper secondary education in recent years. Pre-primary education (educación preescolar), which was made mandatory in 2008-09, begins at age 3 and lasts for 3 years. Enrolment rates have improved in pre-primary education to reach 47.5% of 3-year-olds enrolled in 2017, while remaining lower than the OECD average of 77.8% (data for 2017 provided by the SEP to the OECD). Various early childhood education and care programmes exist nationally. Mexico also introduced a new pedagogical programme for education of 0-3 year-olds in 2017 Programme for Initial Education: A Good Start (Programa de Educación Inicial: Un Buen Comienzo, 2017), which aims to help young children develop and slowly get ready for pre-school (SEP, 2017[19]).

Box 2.1. Delivering equity with quality in education: Main abstracts from the Mexican law

Article 3, Constitution of Mexico

Article 3 of the Constitution of Mexico establishes that each individual has the right to receive an education. The state is expected to provide an education of quality from pre‑primary to upper secondary levels, with the goal to improve education constantly and to pursue the maximum academic achievement of students. The quality of education concretely refers to the materials and methods, the organisation of education, the infrastructure and the adequacy of education professionals that guarantee the maximum learning achievement of students.

Article 2, General Law of Education

Article 2 of the General Law of Education establishes that all individuals have the right to receive an education of quality in equitable conditions, and to this extent, all people living in the country have the same opportunities to access, evolve and remain in the national education system.

Article 3, General Law of Education

Article 3 of the General Law of Education establishes that the state has the obligation to provide quality education services that guarantee the maximum learning achievement of students so all the population can complete pre‑primary, primary, lower and upper secondary education.

Article 8, General Law of Education

Education will be of quality, understood as the coherence between the objectives, the results and the processes of the education system, and in agreement with the dimensions of effectiveness, efficiency, relevance and equity.

Sources: Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación (2018[20]), Political Constitution of the United States of Mexico, https://www.scjn.gob.mx/constitucion-politica-de-los-estados-unidos-mexicanos (accessed on 6 October 2018); SEP (2018[21]), General Law of Education, https://www.sep.gob.mx/work/models/sep1/Resource/558c2c24-0b12-4676-ad90-8ab78086b184/ley_general_educacion.pdf (accessed on 6 October 2018).

To increase enrolment in upper secondary education, in 2012, compulsory education was extended to upper secondary education (Educación Media Superior Obligatoria, 2012). Indeed this is related with equity. High dropout rates affect more disadvantaged students: in 2013, from 14.5% of the students between 15 and 17 years old who dropped out, 36.4% said they did so because they did not have the money to pay for materials or tuition (SEP, 2014[22]). Year repetition also shows stark inequalities: as many as 26.7% of students in indigenous schools and 27.5% in community schools repeat an academic year, while they are only 4.1% in private schools (INEE, 2016[23]). Even after accounting for students’ academic performance, behaviour and motivation, students from a disadvantaged socio-economic background are significantly more likely than more advantaged students to have repeated a year in Mexico. This trend is similar in other Ibero-American countries such as Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Peru, Portugal, Spain and Uruguay (OECD, 2018[12]).

Mexico has developed a number of programmes to prevent dropout and incentivise students to remain in school. Among these, the Movement against School Dropout (Movimiento Contra el Abandono Escolar, 2013) focuses on information dissemination, participatory planning and community outreach. It aims to encourage students to stay in upper secondary education and reduce the risk of social exclusion. The programme Constructing Yourself (Construye T, 2008) aims to complement the measures to reduce dropout and help students catch up by fostering the development of social and emotional skills in upper secondary public schools. It includes teacher training, support to prepare a diagnosis of strengths and weaknesses, a school project to respond to their challenges, and guidance for students.

Issues remain in guaranteeing that the students who need it the most are enrolled, stay and do well in schools. The correlation between students’ socio-economic background and enrolment is noticeable, especially at pre-school and secondary levels. Whereas the difference in enrolment to primary school between the poorest and the richest families is only 2.2 points, it rises to 26.4 points in pre-school. The difference is also of 15 points between the 12-to-14-year-olds in the poorest income decile and those in the top income decile (SEP, 2017[10]). Completion rates (eficiencia terminal) in lower secondary education have been increasing, up to 85.5% in 2017. The completion rate for upper secondary stood increased from 61.3% in 2012 to 66.7% in 2017 (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD).

Providing resources for equity in education

Issues in equity are often linked to the way education resources are allocated in OECD countries. PISA 2015 data consistently show that learning environments in Ibero-America differ in several respects between the most advantaged and the most disadvantaged schools, to the detriment of socio-economically disadvantaged students. To break the circle of disadvantage and underperformance, countries in the region can better align resources with needs and ensure that measures to compensate schools for socio-economic disadvantage effectively create opportunities for all (OECD, 2018[12]).

In Mexico, evidence shows that disadvantaged schools receive fewer resources than they need to provide an education of quality to their students (INEE, 2016[24]; Luschei and Chudgar, 2015[25]). Mexico (with Peru) had the largest socio-economic gap in access to educational materials in PISA 2015, compared to all participating countries and economies (OECD, 2016[2]). Students who attend advantaged schools are less exposed to shortages in educational material than the average student in OECD countries, while those in disadvantaged schools are more exposed to shortages than the average student in all PISA-participating countries and economies (OECD, 2018[12]). When looking at the role of system-level policies to enhance equity in education, it is therefore essential to understand how resources are allocated in education and how much the allocation mechanisms can contribute to equity.

Federal spending in compulsory education (Gasto Federal ejercido en Educación Obligatoria, GFEO) makes up the most part of overall education spending (INEE, 2018[8]). It is allocated to the states through two main channels: the Federalised Spending Programmes (Programas de Gasto Federalizado, or aportaciones), which are earmarked to education; and budgetary contributions (participaciones), which are transferred as part of the states’ sovereign budget and can be used partly for education, depending on each state’s decision. Federal funds complete the overall budget for education through federal programmes (programas federales), which are directly administered by the central government.

Both the Federal and the Federalized Spending Programmes finance current as well as capital expenditures. In basic education, the federal programmes come mostly in the form of compensatory and pro-equity measures, subsidies and provision of various goods and services to schools. The Federalized Spending Programmes support daily operations of education services with 90% of them allocated to financing the payroll of educational staff (servicios personales) in basic education (INEE, 2018[8]). In upper secondary education, the federal government finances some schools directly and entirely (including COLBACHs – Colegio de Bachilleres - in Mexico City, and various baccalaureate and study centres). It also provides indirect funding through subsidies for federalised schools (including the Centre for Scientific and Technological Studies, Centro de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos, CECYTE), which fall under states’ responsibility.

A major initiative taken in 2013 by the Mexican government regarding education funding was to better control the largest category of the Federalized Spending Programme which covers the states’ payments for teachers and administrative personnel (Fondo de Aportaciones para la Nómina Educativa y Gasto Operativo, FONE). The states continue to determine who is paid and what the payment is, but in compliance to general rules which are enforced centrally. The federal government makes the final personnel payments and funds such payments with the resources it provides the states through the FONE. This does not, however, replace the mechanisms that would be necessary for schools to receive the public funds they need to attend to their learners’ needs (Mancera Corcuera, 2015[26]).

As part of a larger initiative to strengthen the role of schools (School at the Centre or La Escuela al Centro), Mexico also innovated by allocating some budgets directly to schools, which the school community (school leaders, teachers along with parent and community representatives) decides how to allocate. The goal was to allocate these direct budgets to approximately 75 000 schools by the end of 2018 (information provided by the SEP to the OECD team).

From the schools’ perspective, federal and state funds blend in with other financial resources to make up the year's budget, which is mainly composed of:

Payment to teachers and administrative personnel administered centrally through the FONE.2

Funds granted within the scope of targeted programmes (either federal or state specific), including for occasional investments in facilities and equipment, which school leaders must apply for to be considered for additional funding.

Parental contributions and money raised by the school and parents’ associations.

It is the responsibility of the school leader and parent representatives to ensure that the funds are kept and managed in a bank account opened to this effect. The school governing body prepares a provisional budget for each financial year and presents it at an annual meeting with parents for consideration and approval (OECD, 2010[27]; INEE, 2015[28]).

Balancing standards and introducing flexibility to guarantee quality for all

Mexico initiated some significant changes in both the standard requirements for basic school operations and in their flexibility, to allow schools to adapt their offer to their students’ needs while guaranteeing a basic education service of quality.

In general, there are some basic conditions that schools must fulfil to facilitate learning improvement, such as being open a certain number of days per year or having teachers in front of the classes. A previous OECD review showed that these basic conditions were not met by all schools in Mexico (OECD, 2010[27]). In 2013, the SEP drew up eight Minimum Standards for School Operation (Normalidad Mínima de Operación Escolar) to raise and ensure quality in all schools. These standards aim to guide school leaders, supervisors and teachers, gathered in School Technical Councils (Consejo Técnico Escolar), in measuring whether their school meets the minimum standards to be able to provide quality education, determined as follows:

1. All schools must provide education services on each day scheduled as a school day in the calendar. For this to be possible, the state education authorities (Autoridades Educativas Locales, AEL) must make sure that schools are fully staffed throughout the year.

2. All class groups must have teachers on each school day, which requires AELs to guarantee that teachers on leave get replaced quickly and adequately.

3. All teachers must start class on time.

4. All students must be on time at all classes.

5. All educational materials must be at the students’ disposal and must be used systematically.

6. All school time must mainly be used for learning activities.

7. The learning activities proposed by the teachers must engage students in the classwork.

8. All students must strengthen their learning in reading, writing and maths according to their academic year and own learning pace (SEGOB, 2014[29]).

Mexico has also made it possible for some schools to adapt their instructional time. An example is the Full-day Schooling programme (Escuelas de Tiempo Completo).

Mexico has reduced its instructional time from 200 compulsory school days per year to 195 days (though some schools have the option to reduce it to 185). This puts the country closer to the OECD average of 185 days per year (OECD, 2016[30]). The context, however, can vary across its 136 195 primary and lower secondary schools (the SEP estimate for the 2017/18 school year). For instance, schooling modalities vary according to features such as the time of the day when students attend class. In 2013, the Census of Schools, Teachers and Students of Basic and Special Education (Censo de Escuelas, Maestros y Alumnos de Educación Básica y Especial, CEMABE) showed that the majority of students went to school for about 4.5 hours in primary schools, either in the morning (matutino) or in the afternoon (vespertino), while students in lower secondary had around 7 hours of classes daily (communication by the SEP to the OECD). Only 2.1% of all public, private and special education schools offered full‑day schooling in 2014 (INEGI/SEP, 2014[31]). Studies and reports from onsite interviews point that learning quality and opportunities are better for students attending morning classes than for those going to afternoon classes (Cárdenas Denham, 2011[32]). Between 2007 and 2013, the number of full-day schools grew steadily from 500 to 6 708, benefitting a total of 1.3 million students (SEP, 2017[33]).

In 2013, the objective for all students to eventually be able to attend full-day schools was introduced (OECD, 2018[34]). The constitutional and legislative reforms established the obligation of the Mexican State to expand the number of full-day schools, offering a full lunch to all students in most disadvantaged areas. The Full-day Schooling programme (Escuelas de Tiempo Completo, ETC) appeared as a crucial tool to help more schools shift to full school days, some with support to offer lunch programmes. The idea behind ETC is to enhance learning opportunities by extending the school days to 6 or 8 hours, thus allocating more hours to academic support for students, expanding the curriculum with an intercultural focus, offering better usage of the schools’ facilities by students – such as the library – and freeing up some time for teachers and their school leaders to work together on pedagogical and other school priorities (SEP, 2017[33]). To this end, ETC disposed of a budget of MXN 2 509 million for the year 2012/13. The budget served to fund training courses for school staff; pay for pedagogical material and equipment; finance onsite lunches for students and staff; and provide general support, advice and monitoring to the schools (CONEVAL, 2013[35]).

Reinforcing coherence among targeted equity programmes

Following the extended right of all Mexicans to a quality education and as part of the New Educational Model (Nuevo Modelo Educativo, NME), Mexico introduced in 2017 a Strategy for Equity and Inclusion in Education (Estrategia para la Equidad y la Inclusion en la Educación, 2017). It aims to build a coherent approach to delivering quality with equity in Mexico. Box 2.2 summarises how the different initiatives come together in the NME.

A common approach to enhance equity is to incentivise schooling via scholarships for the more disadvantaged. Federal scholarship programmes aim to decrease families’ opportunity costs to keep their children in school. A well-known example is the PROSPERA programme, headed by Mexico’s Secretariat for Social Development (SEDESOL), which benefits from significant funding from the SEP. The conditional cash transfer programme targets families living in poverty and focuses on health, nutrition and education. The cash transfers aim to encourage parents to keep their children in school for longer, as the money reduces the opportunity cost of staying in school rather than working. PROSPERA has maintained the main components of Opportunities (Oportunidades), its predecessor, while also expanding its scope. For instance, PROSPERA puts greater emphasis on early childhood development and co-ordinates scholarship programmes for students in upper secondary and higher education, alongside other education institutions. The federal state also spearheads the National Scholarship Programme (Programa Nacional de Becas, PNB), which acts as an umbrella for smaller-scale scholarship programmes in primary, secondary and higher education (OECD, 2018[34]).

Box 2.2. The strategy for equity and inclusion in the New Educational Model

The New Educational Model (Nuevo Modelo Educativo, NME) comprises several lines of action to make inclusion a reality in education, including:

Intergenerational education mobility: Strengthening early childhood and initial education; enhancing access to educational opportunities for disadvantaged groups and widening these opportunities; retaining students in the school system and reducing dropout.

Quality of the learning content: Guide study plans and programmes (Planes y Programas de Estudio, PyPE) to spread an inclusive perspective across learning; design and implement a linguistic educational plan for diversity (Plan lingüístico educativo para la atención de la diversidad) to help educational staff face the specific challenges of diversity-rich learning environments.

Quality of the learning environment: Extending school days; implementing minimum standards for school operations; enable teachers to adapt learning contents and methods to enhance student outcomes in indigenous and migrant schools, in schools with multiple-year classrooms or in tele-secondary education (telesecundarias); provide adequate integral training and professional development to teachers to develop inclusive learning environments in a context of diversity; widen academic support to public schools and other services that attend to indigenous and migrants populations, by increasing the scale of the Programme for Inclusion and Equity in Education (Programa de Inclusión y Equidad Educativa, PIEE) for instance.

A comprehensive description of the initiatives and how the strategy complements and strengthens them can be found in Equidad e Inclusion.

Source: OECD elaboration based on SEP (2017[10]), Equidad e Inclusión, Secretaría de Educación Pública, Mexico City.

Parts of the federal support funds and programmes are specifically devoted to the most marginalised schools in the country. For instance, the SEP’s General Direction of Indigenous Education (Dirección General de Educación Indígena, DGEI) collaborates with state education authorities to promote academic success in rural and indigenous schools (more than 21 000 according to SEP estimates). These schools cater to a large number of indigenous and migrant students (1.2 million students according to SEP estimates) thus providing environments where cultural diversity is extremely rich and teaching and learning can be challenging. DGEI and state authorities take various actions to enable these students to access an education of quality that respects the diversity of their communities. Among other initiatives (SEP, 2018[36]):

Authorities promote the elaboration and distribution of educational materials in indigenous languages.

DGEI and state authorities help to professionalise teachers of indigenous languages and in culturally diverse context (almost 60 000 teachers), including by creating professional standards and offering specific continuous professional development.

The National Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas, CDI) supports indigenous children so they can stay within the education system, providing food and accommodation to children who have to travel away from home to go to school (Casa del Niño Indígena, indigenous child´s home) and offering lunches.

The National Council for Education Development (Consejo Nacional de Fomento Educativo, CONAFE) – a public agency linked with the Secretariat for Education – designs, implements, operates and evaluates educational programmes to guarantee that children and young people receive an education of quality even in the most remote areas. The council guarantees education in community schools, for instance (SEP, 2017[10]). The CONAFE’s mandate was strengthened as part of the Strategy for Equity and Inclusion in Education, to enhance governmental support to students in remote and marginalised areas. The modifications include a stronger co‑ordination with PROSPERA’s actions as well as the improvement of the CONAFE’s educational model for basic education.

Strengthening conducive learning environments for all

Schools’ infrastructure and equipment determine the baseline conditions in which learning develops (OECD, 2014[37]). Studies of the impact of physical environments on student learning are scarce, but even if the precise impact on learning is unclear, students have the right to go to schools where the basic sanitary and safety conditions are met (including safe constructions, electricity, water supply and ventilation). In the case of Mexico, where many schools are in dire conditions, ensuring they all dispose at least of some minimum facilities such as safe buildings, restrooms and electricity are thus crucial to improving learning opportunities for all students.

The existing empirical literature finds that school facilities and, more generally, the physical learning environment affect educational quality at least through its interaction with other factors (Cheng, English and Filardo, 2011[38]). Another study shows that infrastructure influences learning outcomes in Mexico (ASF, 2018[39]). Such studies on Latin American countries observe various effects of school facilities and physical investment on learning and academic results. Enhancing the physical environment is more likely to improve learning in areas where the quality of school facilities is low. The most significant physical factors explaining countries’ results on the SERCE (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] Second Regional Comparative and Explanatory Study on education policy in Latin America and the Caribbean) tests were: the presence of pedagogical spaces such as a library or a computer room, whether the schools were connected to public electricity and telephone networks, and whether fresh water and bathrooms were available (Duarte, Jaureguiberry and Racimo, 2017[40]).

In an education system the size of Mexico’s, ensuring that more than 225 757 schools in basic education (estimation by the SEP for primary and lower secondary education for the 2016/17 academic year) are equipped with the basics is a challenge in itself. In 2014, 9 federal entities had at least 100 schools without physical constructions at all or that were made with precarious materials. Among the physical public schools, 31% had no access to the public water distribution system, 11.2% had no electricity and 12.8% no sanitary facilities, while 31.1% and 26.5% had access to the Internet and to a landline respectively.

Basic infrastructure can be a source of large discrepancies between schools and between states. For instance, close to 100% of private schools had access to electricity and 92% had an Internet connection, compared to 88.8% and 31.1% of public schools respectively. Inequalities are also to be found between states, for example in terms of water distribution: 41.7% of schools overall did not have access to the public water distribution system in the state of Guerrero, while it was true for only 3.5% schools in Mexico City (INEGI/SEP, 2014[31]). Although a good teacher and motivated students probably do not need elaborate installations to succeed, a basic minimum may be necessary to facilitate learning conditions, whether in terms of safety, health or pedagogical equipment.

In Mexico in general, disadvantaged schools have access to fewer resources than what they need (INEE, 2016[24]): principals of disadvantaged schools report receiving fewer educational materials and staff than advantaged schools. Mexico is among the PISA countries for which this difference is the largest (OECD, 2016[2]). The education services available in disadvantaged areas are often precarious. In 2013, for instance, 42.7% of primary and 37.1% of lower secondary community schools were not made of proper construction materials, as was the case for 18.1% of indigenous primary schools (SEP, 2017[10]).

To tackle the quality of school infrastructure in Mexico, which has been an issue for years, the state has undertaken a range of measures. School infrastructure quality, mainly measured in terms of safety, functionality, inclusiveness and adequateness (LGE Article 7) refers to “decent and functional spaces that incorporate new technologies to facilitate and inspire pedagogy, requiring the necessary physical infrastructure that is kept up to date” (SEGOB, 2014[41]). By law, the state must provide school environments with safe buildings, provide basic services such as hydro-sanitary systems and electricity, and incorporate the technologies necessary for schools to prepare all students for the 21st century.

The National Institute for Physical Educational Infrastructure is the main institution in charge of ensuring quality in school infrastructure in Mexico (Instituto Nacional de la Infraestructura Física Educativa, INIFED). The INIFED establishes the law and certifies the quality of school infrastructure; gives advice to schools on how best to prevent or deal with existing damages; and keeps an information system on the state of physical school infrastructure up to date. Each of the 32 entities has its own institution in charge of building, equipping, rehabilitating and maintaining the school infrastructure, except for the City of Mexico where the INIFED fulfils these responsibilities directly (Ley General de la Infraestructura Física Educativa, Article 19, 2014).

To update basic information on student and teacher populations, and on school infrastructure, the SEP and the National Institute for Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI) administered a large census (Censo de Escuelas, Maestros, y Alumnos de Educación Básica y Especial, CEMABE, 2013). Following the census findings on the state of school infrastructure, the INIFED undertook a large-scale diagnosis of school infrastructure needs in 2015. It found that of the 146 392 primary and lower secondary schools surveyed, 98.9% needed some investment to enhance their structure’s safety and general functioning, 98.5% needed funding for sanitary services, 96.4% were in need of furniture and equipment (ASF, 2018[39]). Based on the information gathered in the CEMABE census and INIFED survey, two new programmes were engineered to complement and replace previous measures to enhance school infrastructure: the Education Reform Programme (Programa de la Reforma Educativa, PRE) and the programme Escuelas al CIEN (ECIEN).

Furthermore, the CONAFE and the state of Campeche have been running pilot projects to give students the opportunity to attend schools with complete staff and better infrastructure, and to interact with children from different backgrounds. These projects target mostly multigrade schools (mainly CONAFE or one-teacher schools), in which one teacher is in charge of all students, all years included, and where the infrastructure is often of poor quality.

In summary, Mexico’s education system displays large disparities in school learning environments. This issue has been highlighted as a priority for education authorities, who harnessed promising existing initiatives, and enriched these with new programmes and resources to scale up investment and make school environments more conducive to learning.

Overall, Mexico has focused on equity as a key policy issue at both a general and more targeted level, with a range of policies and programmes aiming to reduce inequalities and respond to the needs of all its learners. It is important to review how these policies are adopted and effectively contribute to equity.

Assessment

Mexico has succeeded in developing its educational policies at a remarkable pace and a large scale. The capacity of the public education system to evaluate its own needs for improvement and act on them is commendable, as are its actors’ willingness to undertake assessments by both national and international actors. The latter is proof of Mexico’s readiness to take action in order to improve its education system, which is a considerable achievement in light of challenging environment for education reform. Introducing the right to an education of quality in the constitution sets Mexico among ambitious education systems that strive to achieve both excellence and equity for their students. To make this right a reality for all students, Mexico has been progressively shifting toward a more coherent approach to equity, using both system-wide education policies and targeted equity programmes.

System-level measures: Extending opportunities for learning to all

Improving enrolment in ECEC and upper secondary education

Mexico’s overall education level has significantly improved over the past four decades. For over ten years, Mexico has guaranteed that more than 95% of its youth between the ages of 5 and 14 get access to education. Recently, Mexico has expanded access from ECEC to upper secondary education. Overall enrolment rates by age 4 have been rising, from 87.3% in 2012 to 91.5% in 2017, beyond the OECD average (compiled annual education statistics provided by the SEP for the 2012‑18 period). The enrolment of 3-year-olds in pre-primary education (educación preescolar) has nearly doubled since 2005 but 47.5% were enrolled in 2017, lower than the OECD average of 77.8%. Nevertheless, the participation of children in ECEC varies widely among regions. According to national data, in 2016-17 net enrolment for children aged 3 to 5 ranged from 94.9% in Tabasco to 59.5% in Quintana Roo (SEP, 2017[42]).

Mexico has also faced a significant challenge of improving the quality of ECEC. According to PISA 2015 results, the average gap in science scores between students who attended at least more than 1 year of pre-primary school and those who had attended 1 year or less was 41 points across countries. This identified difference in performance provides some evidence on how important ECEC can be for the academic success of students (although this may be more difficult to take into account for education systems where children have more recently migrated into the system). In Mexico however, having attended ECEC does not yet have an effect on students’ results: after accounting for socio-economic differences, 15-year-old students who had benefitted with at least 2 years of pre-primary education during their childhood scored no higher than their peers who did not receive pre-primary education (OECD, 2017[18]). Early childhood education and care is one of the areas where there is the greatest social disparity in Mexico. First, disadvantaged populations are less likely to send their children to pre-primary education; and second, pre-primary education still receives a small portion of education spending. In order to improve the quality of learning from early childhood education, Mexico has intended to align the guidelines used in initial education and the new curriculum (2017). The pedagogical programme for education of 0-3 year-olds Programme for Initial Education: A Good Start (Programa de Educación Inicial: Un Buen Comienzo, 2017) aims to help young children develop and slowly get ready for pre-school, in respect of their own right to an education of quality (SEP, 2013[43]).

Enrolment for 15‑19 year-olds has been more challenging but has been improving following a number of initiatives. In 2012, Mexico made upper secondary education (educación media superior, EMS) compulsory until 17 for all young Mexicans, with the goal of attaining universal coverage at that level by 2022. This was accompanied by a number of programmes directed to the students most at risk of dropping out.

The Movement against School Dropout (Movimiento Contra el Abandono Escolar, 2013) includes the physical and digital distribution of handbooks and yearly workshops in schools on dropout prevention for teachers and school leaders. In 2014‑15, 70 training sessions were held in which 12 000 teachers and school leaders took part (data provided by the SEP, July 2018). Some evidence suggests that the policy has had a significant impact in reducing dropout, estimated at 952 769 students by the SEP (idem). It is, however, recommended to continue monitoring to ensure the efficacy of the programme (OECD, 2018[34]). The SEP and state education authorities also established in 2013 that one of schools’ improvement priorities (ruta de mejora) should be to identify low performers, give them special support and prevent them from dropping out. From 2016 to 2018, 81 000 schools installed an early alert system (Sistema de Alerta Temprana, SisAT) to systematise this goal (data communicated by the SEP based on reports by state education authorities).

The programme Constructing Yourself (Construye T, 2008) has been implemented in almost 33% of schools by the SEP, assisted by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and another 39 non‑governmental organisations. Over 20 000 teachers and principals have received capacity-building training since 2013 (OECD, 2018[34]). The National Programme of School Coexistence (Programa Nacional de Convivencia Escolar) started in 2016 with similar objectives to develop socioemotional skills and prevent bullying and discrimination.

Up until 2013, about half of 15‑19 year‑olds were not enrolled in school: the enrolment rate reached a peak at 56% in 2011, then lost 3 points the following year before rising up to 57.3% in 2015. Although it is not unusual for enrolment rates to vary, their level still remained low compared with the OECD average of 84.2% (OECD, 2017[7]). Yet the initiatives in 2012‑13 were followed by a substantial rise in the enrolment rates for the 15‑17 year-old age group, which corresponds to the people whose age makes it compulsory for them to attend school since the new age limits for compulsory education. This rate went from 65.9% in 2013 to an estimated 76.6% in 2017 (compiled annual education statistics provided by the SEP for the 2012‑18 period).

The graduation rates for upper secondary education have remained on the lower side, at 56% in 2015, compared to an OECD average of 86% (OECD, 2017[7]). This could be explained partly because the dropout rate remains high: 15% of the students enrolled in 2015 did not enrol again in upper secondary education (Educación Media Superior, EMS) in 2016 (INEE, 2018[8]).

Exploring equitable funding solutions for education

Expenditure on education in Mexico represents a higher share of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), at 5.4% in 2014 compared to the OECD average of 5.2% (OECD, 2018[34]). Expenditures have been increasing in compulsory education, especially since 2013, which coincides with the inclusion of upper secondary education in compulsory education (INEE, 2018[8]). These expenditures, however, remain low when looking at expenditure per student: in 2014, Mexico spent USD 2 896 annually and per student at primary level, below the OECD average of USD 8 733 (values in purchasing power parity). Similarly, the annual per-student spending at secondary level was USD 3 219, below the OECD averages of USD 10 106 (OECD, 2018[34]).

States design their own approach to the distribution of resources across individual schools (INEE, 2018[8]). Little information is available on how such distribution takes place but part of it seems to be on a historical basis (adjusting previous amounts for inflation) (Santiago et al., 2012[44]). According to observers, monitoring effective use of federal funds is indeed dependent upon state education authorities’ capacity to gather, verify and report detailed information, which might turn out to be difficult for some of them (Mexicanos Primero, 2018[45]).

Exchanges with stakeholders in Mexico revealed that the level of resources schools actually receive from the government is low and unequal. To receive funds from targeted programmes, schools depend on bureaucratic procedures that capture a lot of school leaders’ time, away from pedagogical issues. They depend on parental contributions and other fundraisers to cover their operational expenses. For instance, a study by the INEE in 2010 reported that parental contributions were the main source of funding for pre‑schools, contributing over 56% to infrastructure, equipment and furniture (Martínez et al., 2010[46]).

There are two main ways of operationalising equity in education: horizontally and vertically. Horizontal equity is usually defined as the equal treatment of equals: horizontally equitable funding schemes are set such that there is a minimal dispersion in the access to resources within a given subpopulation of students or groups of schools. Vertical equity is typically defined as the unequal treatment of unequals. Vertically equitable funding schemes focus on providing differential funding for different student groups, reflecting the additional cost of providing similar educational experiences across students with different characteristics (OECD, 2017[47]).

In Mexico, the main mechanisms for education funding do not take into account the differences in schools’ needs and the different costs attached to those, which means that schools in disadvantaged contexts usually have less financial resources and require extra funding through programmes to operate (Cortés Macias, 2015[48]). Insufficient funding can only perpetuate inequalities, given that disadvantaged schools usually have infrastructure and equipment of relatively poorer quality (INEE, 2016[24]) and teachers who tend to be less trained, less experienced and less incentivised to stay for several years (Luschei and Chudgar, 2015[25]). Discussions have been ongoing between experts and political representatives about alternative funding formulas to distribute federal funds in a more equitable way. However, the distribution still fails to take into account key equity indicators, which limits the possibilities for regular funding mechanisms to contribute to equity (Cortés Macias, 2015[48]). Some experts have been advocating for a change in the education funding formula to make it more equitable (Caso Raphael, García Martínez and Decuir Viruez, 2016[49]). Schools attending poor communities, therefore, tend to continue the cycle of disadvantage. Subsequently, attention should be paid to how education resources in general – not only financial – are allocated, and which impact this has on equity.

Box 2.3. Chile’s formula-driven school grants

In Chile, the main mechanism of public financing is in the form of school grants from the state to school providers (municipalities, for instance), who directly manage the funds. The basic school grant (Subvención de Escolaridad) results from multiplying a basic amount updated yearly by the monthly average student attendance and an adjustment factor by level and type of education. The basic grant is complemented by a range of more specific allowances and grants to acknowledge that the cost of providing quality education varies depending on the characteristics and needs of students and schools. For instance, the Preferential School Subsidy aims to level the differential cost incurred by schools tending to vulnerable students. Complementary financial transfers include allowances directly given to education staff

Chile’s system of formula-driven school grants provides a transparent and predictable basis for school providers. Unlike many other countries around the world, school financing is based on objective criteria (number of students being the most important one but with adjustments for other factors affecting schools’ per-student costs) and not on the result of negotiations between the government and public and private school providers. The existence of a clearly defined and objectively measured formula as the basis for allocating resources imposes a hard budget constraint to providers and creates the conditions for basic spending discipline, an important feature in a system with many school providers. The formula also accommodates the needs of a diverse network of service providers. Finally, resource allocation is not inertial and responds to new policy priorities: when a new policy requires additional resources, the budget changes accordingly.

Source: OECD (2017[50]) “Funding of School education in Chile”, in OECD Reviews of School Resources: Chile 2017, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264285637-6-en.

Allocating resources equitably means that the schools attended by socio-economically disadvantaged students are at least as well-equipped as the schools attended by more privileged students, to compensate for inequalities in the home environment (OECD, 2016[2]). There are two broad approaches when designing mechanisms to allocate funding according to different needs across schools. First, including additional funding in the main allocation mechanisms for schools (e.g. including weights in the funding formula to allocate additional resources according to certain categories). The second one consists in providing targeted funding through grants external to the main allocation mechanism. Research in educational economics has provided evidence supporting well-designed and transparent funding formulas as the best way to combine horizontal and vertical equity while incentivising the efficient use of school resources at the different levels of the system. In other words, funding formulas promote horizontal equity by ensuring that similar funding levels are allocated to similar types of educational provision. Formulas enhance vertical equity by adding different amounts to the basic fund allocation according to the degree of needs of schools (OECD, 2017[47]). Countries such as Chile have developed effective school funding formulas, as detailed in Box 2.3.

Standardising basic operational conditions to improve schools’ capacity

The eight basic standards for school operations are not only for education authorities to put into law; they are meant to serve as guidelines for school communities to assess the quality of their own school against these references. As such, a first indicator of whether the standards could become a reality at school level is whether the school community, and especially its School Technical Council (Consejo Técnico Escolar, CTE), know about it.

CTE consists of a collegial body composed of the school leader and the entire professorship in schools with at least four of five teachers (OECD, 2010[27]). It is in charge of planning and implementing common decisions necessary for the school to fulfil its mission. In particular, CTE discusses the school’s needs in terms of pedagogy and plans the Improvement Route (Ruta de Mejora) focusing on four priorities: key learnings, minimum standards for school operations, living together (convivencia escolar) and preventing dropout (SEP, 2017[51]; SEP, 2017[10]).

In order to help CTEs use the standards, the SEP has been publishing a series of handbooks for CTE management, with guidelines about how to analyse a school’s conformity to the minimum standards (SEP, 2017[52]). The SEP has been monitoring 1 200 CTEs during the 2017/18 school year, which shows that most schools have regular CTE meetings where the council checks on school indicators, analyses them and uses the analysis as input to elaborate its Improvement Route (Ruta de mejora) and make decisions. The study also shows that it is necessary to improve CTEs’ capacity to set goals and monitor them, and to take strategic decisions (information provided by the SEP to the OECD team). These results are coherent with publicly available reports on the evaluation of the Education Reform Programme in each state and the school communities our team met during its visit. Evaluation reports on all the components of the Education Reform Programme (Programa de la Reforma Educativa) published for transparency purposes are available on the programme’s online platform, for the years 2014‑15 and 2015‑16 (SHCP, 2018[53]). Whether schools consistently meet the minimum standards for school operations, remains to be assessed, however.

Promoting full-day schooling for inclusive education

The issue of instructional time is complex, with many factors determining the quantity and the quality of the education it provides. Research on the effect of instructional time on student learning is scarce, although it is crucial for governments to make informed decisions about whether to invest in longer school days. Instruction time in formal classroom settings accounts indeed for a large portion of public investment in student learning (OECD, 2011[54]).

Large-scale studies find no strong relationship between instructional time in general and student performance on test scores (Van Damme, 2014[55]; Hattie, 2015[56]; Long, 2014[57]). At a smaller scale, studies tend to find that an increase in instructional time can lead to better student performance on tests, although the effects seem to vary according to the country’s context, the type of school and individual student characteristics (Cattaneo, Oggenfuss and Wolter, 2016[58]; Hincapie, 2016[59]; Anderson and Walker, 2015[60]). The effect of lengthening the school day on equity is also unclear (Orkin, 2013[61]). Few studies focus on the effects of going specifically from half-day to full-day schooling, but the existing point to beneficial results. The literature that looks at similar policies for pre‑school levels finds better academic and socioemotional outcomes for children who attended full school days compared to those who went to half-day kindergartens (Carnes and Albrecht, 2007[62]; Gullo, 2006[63]).

The amount of time spent in school is, in fact, less important than how the available time is spent and on which area of study, the quality of the teachers, how motivated students are to achieve and how strong the curriculum is. OECD countries set the amount and distribution of instruction time in very different ways, although recent trends show a reinforcement of core subjects. PISA reveals an increase in classroom instruction time in core subjects between 2003 and 2012, and a reduction in the time students spend doing homework outside the classroom: 15-year-olds spent an average of 13 more minutes per week in mathematics class in 2012, while they reported spending 1 hour less on homework than in 2003 (OECD, 2016[30]). Research insists on the impact that teachers have on student achievement through the type of assessments they use and feedback they give, the level of expectations they set for their students and the general quality of teaching (Hattie, 2009[64]).

As shown in international evidence, the relationship between learning time or teaching hours, and learning performance is unclear for high-performing countries (Haahr et al., 2005[65]). Although Mexico is already among OECD the countries with the longest instructional time, there can be equity issues between morning, afternoon and evening schools (Cárdenas Denham, 2011[32]). By turning some dual shift schools (escuelas de doble turno) into full-day schools, Mexico could enhance both quality and equity of its service provided the extra learning hours are used to teach high-quality content. Mexico succeeded in multiplying the number of full-day schools by almost 4, to reach an estimated 25 032 schools and benefit 3.6 million students in 2017 (SEP, 2017[33]). Out of the beneficiary schools, 60% were rural or indigenous schools.

A World Bank study on the impact of ten years (2007‑16) of the Full-day Schooling programme (PETC) finds that the full days contributed to improving student learning –increasing the number of high-performing students and decreasing the number of low performers – and to reducing the number of students who significantly lagged behind in primary school. Interestingly from an equity point of view, these positive effects were stronger for students in vulnerable schools. More specifically, results in disadvantaged schools show major decreases in the share of students who scored at the lowest level in mathematics and language (The World Bank, 2018[66]).

Mexico has been leading some system-wide policies which aim to contribute to inclusion in education. Increasing enrolment rates, raising resources allocated to education and adjusting schools’ obligations and possibilities to operate are measures that can enable all schools to guarantee basic standards of quality and to make sure students are in school to benefit from them. Especially, the goal to reach universal coverage between pre-primary and upper secondary education should be pursued. However, the effectiveness and adequacy of other initiatives should be studied while taking into account the actual capacity to implement at the local and school levels.

Targeted approaches: Extending support to the most disadvantaged

Support has considerably grown to the most disadvantaged students and schools between 2013 and 2017. According to SEP estimates, the number of indigenous schools who received support from federal programmes increased by 274% between the year 2012/13 and 2016/17 (SEP, 2017[33]). This represents close to half of the total number of indigenous schools estimated in early childhood and primary education year (N.B. the total of indigenous early childhood and primary schools was estimated at about 20 000 (compiled annual education statistics provided by the SEP, 2012‑18).

As part of its actions to enhance education in the most marginalised schools, the CONAFE (Consejo Nacional de Fomento Educativo) developed its own educational model for initial and basic education, and adapted it to the new curriculum of 2017. The ABCD model (Aprendizaje Basado en la Colaboración y el Diálogo) aims to adapt to the challenges faced by communities in remote or deprived areas. Its objective remains to get children up to speed with the basic learning they need to join the “regular” system – i.e. federal or state schools that use the regular curriculum. The “CONAFE system” is based on the use of 37 000 “young educational leaders” who teach for at least 1 year and receive 2 years’ worth of financial support for their own education. In 2018, the “CONAFE system” provided education to an estimated 665 000 students in basic education (data communicated to the OECD team during its visit in June 2018).

Through its Programme of Support to Indigenous Education (Programa de Apoyo a la Educación Indígena, PAEI), CDI (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas) provided food and/or accommodation to more than 60 000 children through the Indigenous Child’s Homes and Canteens (Casas y Comedores del Niño Indígena). The Community Homes and Canteens for the Indigenous Child provided food and hygiene services to almost 16 000 children and young people (SEP, 2018[36]).

The Mexican State’s scholarship and financial support programmes are also key in reducing inequalities between students. Overall, federal programmes provided various types of scholarships to around 7 million students in compulsory education in 2016/17 (SEP, 2017[33]). The vast majority of these scholarships were financed through PROSPERA’s programme for basic education (PROSPERA Programa de Inclusión Social) (SEP, 2017[33]). For the 2017/18 school year, the SEP distributed through PROSPERA close to MXN 18 120 million in scholarships for basic education and almost MXN 13 000 million in upper secondary education (data communicated by the SEP directly to the OECD team). The PROSPERA programme has helped increase enrolment rates in secondary education, diminish the incidence of anaemia among children and reduce poverty rates in rural areas. PROSPERA remains a model of success for other cash transfer programmes worldwide (OECD, 2018[34]).

The Strategy for Equity and Inclusion in Education (2017) tries to build coherence around the diverse programmes which Mexico has been carrying out to cope with inequalities of all sorts. Because the strategy is very recent, there has not been time to assess whether this coherence has been translated into changes in the operations of the various programmes. However, some earlier attempts by Mexico to make its approach to equity more coherent have been studied, including for instance the Programme for Inclusion and Equity in Education (Programa para la Inclusión y la Equidad Educativa, PIEE).

In an attempt to simplify the funding mechanisms for equity programmes, the PIEE started operating in 2014 as a result of the merge of seven previously existing budget programmes (N.I.K. Beta S.C., 2017[67]). The PIEE aims to strengthen the capacities of schools and educational services that serve indigenous children, migrants and students with special educational needs. The PIEE is active in basic, upper secondary and higher education and counts five components:

actions in indigenous schools

actions in education centres for migrants

special education services for students with disabilities and outstanding abilities

special centres for students with disabilities (Centros de Atención a Estudiantes con Discapacidad, CAED) at the upper secondary level

support for higher education institutions to promote equity and inclusion.

For each of the above, the PIEE provides financial and academic support, as well as funding for infrastructure improvement of disadvantaged schools. In 2017, 65% of the resources at its disposition were meant for actions in favour of the indigenous and migrant populations. This benefitted 5 445 indigenous and migrant schools that same year or around 27% of the total number of indigenous schools estimated for that year (SEP (2017[33]) and compiled annual education statistics provided by the SEP, 2012‑18).

An independent evaluation of the programme’s design, process and results was carried out for the CONEVAL (N.I.K. Beta S.C., 2017[67]). It emphasises the relevance of the PIEE, in that it responds to a well-defined need and acknowledges the fact that it met its targets although the latter were considered low given the programme’s budget. It should be noted that the programme catered to no fewer than 176 000 students in 2016 only (OECD, 2018[34]). The report raised attention on the need for deeper analysis of the programme’s design, however. Given its scope, the programme is supposed to cover the needs of a very large population, which requires separate lines of actions and separate entities to drive and run the programme (responsibilities are still shared across the three Undersecretaries of Basic, Upper Secondary and Higher Education). Therefore, the report suggests re-evaluating the programme’s design to align it better with its operational requirements (N.I.K. Beta S.C., 2017[67]).

Although Mexico has been fighting against inequalities for a long time, the new constitutional mandate to provide quality with equity in education raises the challenge one step higher. The need for more equitable provision mechanisms increases as the required levels in terms of quality rise. Some targeted programmes such as PROSPERA and the CONAFE model keep being very relevant and effective. However, the programme-based approach to equity does not suffice to guarantee education of quality to all students. Mexico has been building coherence in its approach, embedding its programmes into a broader strategy for equity and inclusion. More efforts could be made in this direction, to make sure that equity translates into effective improvements in all students’ learning.

Safer and more adequate learning environments

Enhancing the physical infrastructure of schools requires some referential that defines what quality and safety mean. Such referential was defined between 2013 and 2015, and have guided INIFED assessments of the educational infrastructure since then (SEGOB, 2013[68]; SEGOB, 2015[69]). These criteria include, for instance, whether the schools are ventilated, whether they dispose of their waste in a safe manner, whether they have green spaces, as well as if the building is in good shape, old or damaged (SEGOB, 2013[68]). Based on these criteria, the INIFED classifies school infrastructure in one of three categories: minimal (esencial), functional or sustainable. Between 2013 and 2018, more than 11 000 schools were certified by the INIFED because they complied with at least 3 of the criteria for infrastructure safety and quality. Certifications were granted either through its National Certification Programme (Programa Nacional de Certificación, 124 schools) or through Escuelas Dignas (4 482 schools) or Escuelas al CIEN (6 775 schools) (INIFED, 2018[70]).