This chapter introduces the concept of enhancement-oriented innovation as part of the Public Sector Innovation Facets model. It presents evidence about this innovation facet drawing on three areas that engage with the facet most: incremental innovation, digitalisation and public sector productivity. Enhancement-oriented innovation is driven by public sector constraints on resources and costs, principles of New Public Management (a market-driven public administration paradigm), and digitalisation and adoption of new technologies. Numerous structures support enhancement-oriented innovation, including evaluation, auditing and performance measurement systems. Developing digital skills within public sector organisations, and adoption of new digital or funding infrastructures can sustain enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector.

Tackling Policy Challenges Through Public Sector Innovation

5. Enhancement-oriented innovation

Abstract

General description

Enhancement-oriented innovation is public sector innovation to improve and upgrade existing practices and structures without significantly altering current systems. This is generally done by working within existing knowledge, processes and functions to answer “How might we do X better?”

There is neither a concept of enhancement-oriented innovation in public administration literature, nor a single criterium or exhaustive list for identifying this type of innovation. As defined in the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation's (OPSI) facets model, the following qualify innovation as enhancement-oriented:

It engages with change connected to current services, processes and systems in the public sector.

It results in innovation (rather than mere change), meaning it must be new to the context, implemented, and have an impact (whether positive or negative) on public value (OECD, 2018[1]).

It seeks to achieve greater efficiency, effectiveness and value for money.

It is important to emphasise the distinction between business improvement and enhancement-oriented innovation. Since enhancement-oriented innovation results in innovation rather than mere change, it does not always equate to improvement. Improvement carries normative value and implies positive effects. While innovation can enhance current systems, it might not necessarily result in overall improved conditions or outcomes. For example, digitising a service might increase cost efficiency but come at the cost of decreased privacy or other values.

Based on this definition, enhancement-oriented innovation includes established concepts in the literature, such as incremental innovation and improvement innovation (Table 5.1) but remains broader than these. These types of innovations may not be radical or disruptive but are widespread in the public sector and can have a significant impact on government operations and delivery of public services.

Enhancement-oriented innovation often includes structured planning and learning processes to consolidate insights and build on them (Table 5.3). Some common methods are lean management, process improvement, quality control and behavioural insights approaches. These vary in scope but can cut across domains of public sector activity and be implemented at almost all levels of government.

The challenge

Faced with the growing complexities of the digital age (Benay, 2018[2]) and with decreasing levels of public trust (OECD, 2021[3]), governments seek to find new and better ways to optimise public sector organisations, processes and services (De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[4]). Rapid technological change, austerity policies and rising expectations of government services increase pressure on the public sector to serve citizens better, faster and more efficiently while minimising costs (Mulgan and Albury, 2003[5]). Governments are expected to extend choice in services, tailor these to user needs, and be evidence-informed in service allocation and decision-making (McGann, Wells and Blomkamp, 2021, p. 299[6]). The wave of behavioural insights in policy calls the public sector to address challenges from within: tweaking services to incentivise positive behaviour (OECD, 2017[7]). This aligns with the call for “smart” services using technology to optimise provision and accessibility (Velsberg, Westergren and Jonsson, 2020[8]). In many countries, these factors lead to a high volume of incremental public sector innovations or bricolage (Bugge and Bloch, 2016[9]; De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[4]).

Under these pressures, governments are expected to deliver more with fewer resources (Andersen and Jakobsen, 2018[10]). Public sector organisations must continuously enhance their operating systems while demonstrating efficiency, user-centricity and value for money.

The approach

To understand the nature of enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector, OPSI researched academic and policy literature, and collated experiences from public sector practitioners. This section of the report shows the main themes of enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector. It is structured as follows: (1) General description of the facet; (2) Main drivers of enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector; (3) Enabling factors; (4) Tools and methods; (5) Skills and capacities needed; (6) Policy and implementation challenges; and (7) Unanswered questions. The rest of this introduction covers how enhancement-oriented innovation relates to the current public sector literature, in particular established concepts such as incremental innovation, digital government, and public sector productivity.

Research findings

This report introduces enhancement-oriented innovation as a concept in the Public Sector Innovation Facets model. The concept does not exist as a distinct term in literature discussing public sector innovation, but it relates to several research streams. Enhancement-oriented innovation engages with current structures, is new to the context, and has an impact on public value. Search terms based on the definition of enhancement-oriented innovation were used to identify relevant research streams in public sector literature. These included: efficiency, productivity, exploitation and effectiveness. The research finds that literature on public sector ambidexterity, incremental innovation, improvement innovation, digitalisation and productivity provides discussions relevant to this innovation facet (for definitions see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Definitions of concepts relevant to enhancement-oriented innovation

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Ambidexterity |

"The ability to balance and reconcile the interdependent processes of innovation and optimisation” (Gieske et al., 2020, p. 343[11]). |

|

Improvement innovation |

“Reflecting an increase in the prominence (or quality) of certain characteristics without changing the structure of the system of competences” (Djellal, Gallouj and Miles, 2013[12]). |

|

Incremental innovation |

“Involves discontinuous change to products and services ... [and] takes place within the existing production paradigm“ (Osborne and Brown, 2013, p. 5[13]). |

|

Productivity |

"Calculated as the ratio of all the outputs produced by a given organisation divided by all the inputs or the resources used in producing those outputs" (Dunleavy and Carrera, 2013, p. vii[14]). |

Based on data from the OECD OPSI case study library, enhancement-oriented innovation is one of the most widespread innovation types in the public sector. It shares many outcome measures and objectives with private sector innovations (Bugge and Bloch, 2016[9]), including cost reduction objectives, quality improvement, and the need to meet citizen demands while dealing with limited human or financial resources (Arundel, Bloch and Ferguson, 2019, p. 795[15]). There are connections between enhancement-oriented innovation and the New Public Management paradigm

Incremental innovation and ambidexterity

Scholars working on incremental innovation and ambidexterity discuss the optimisation of existing processes, services and structures in the public sector (Barrutia and Echebarria, 2019[16]; Boukamel, Emery and Gieske, 2019[17]; Osborne and Brown, 2013[13]). This research illuminates the distinction and balance between enhancement-oriented innovation and business improvement.

Enhancement-oriented innovation is wider than incremental innovation, but some practices can be characterised through it. According to Osborne and Brown (2013, p. 5[13]), incremental innovation “involves discontinuous change to products and services” and “takes place within the existing production paradigm”. Enhancement-oriented innovation includes innovation that changes current products and services but with the strategic aim of bettering the current system. One of the main challenges discussed in the literature on incremental innovation is the distinction between innovation and regular business development. Within the public sector literature, this distinction is reflected in the concept of incremental versus radical innovation. Thus, practices connected to enhancement-oriented innovation can be characterised by their focus on the optimisation of existing structures within organisations’ conventional way of doing things.

Research on ambidexterity reveals how organisations balance their operations between the improvement of current activities (exploitation) and the pursuit of new, more radical approaches (exploration) (Barrutia and Echebarria, 2019[16]; Boukamel, Emery and Gieske, 2019[17]; Cannaerts, Segers and Warsen, 2020[18]; Choi and Chandler, 2015[19]; Matheus and Janssen, 2016[20]; Palm and Lilja, 2017[21]). Gieske et al. (2020[11]) show that while exploitation initially has a greater impact than exploration on public sector performance, it has diminishing returns when organisations over-optimise. Yet, “efficiency creep” bias in organisations favours efficiency-oriented investments over innovation investments (Magnusson, Koutsikouri and Paivarinta, 2020[22]). While organisations should balance exploitative and explorative activities, evidence suggests that exploration is a more significant force for stimulating innovation (e.g., Boukamel et al. (2019[17]); Cannaerts, Segers and Warsen (2020[18]); Gieske et al. (2020[11]); (Magnusson, Koutsikouri and Paivarinta (2020[22]); Matheus and Janssen (2016[20]); Palmi et al. (2020[23])). For example, the Swedish Social Insurance Agency (SIA) was able to favour exploration activity and structural ambidexterity thanks to the creation of an innovation hub in its IT department, which provides employees with a “safe space” to generate innovative ideas (Magnusson, Koutsikouri and Paivarinta, 2020[22]).

In most cases, enhancement-oriented innovation can be connected to exploitative innovation that aims to improve existing processes and services without fundamentally challenging established ways of thinking. In the literature, Halvorsen and Hauknes (2005, p. 5[24]) coined the term “efficiency-led innovations” to describe product innovations in the public sector that are “initiated [...] in order to make already existing products, services or procedures more efficient”. The desired results from optimisation using enhancement-oriented innovation are thus typically related to increasing efficiency.

Digitalisation and e-government

The search terms returned several articles on digitalisation in the public sector, which show that digitalisation projects motivated by optimisation and efficiency can be connected to enhancement-oriented innovation. Digitalisation in the public sector is characterised by different maturity phases. At initial stages, digitalisation involves moving paper-based processes and procedures online (e-government). When organisations advance further, towards digital government, technology is used to design, operate, and deliver services for increased trust and wellbeing (OECD, 2014[25]). Therefore, the initial stages of digitalisation are arguably more linked to enhancement-oriented innovation while later stages can be considered more closely linked to adaptive (Chapter 6) or anticipatory (Chapter 8) innovation.

Research finds that e-government initiatives can serve as “carriers for innovation”, central in the creation of new products and services, contributing to the “improvement of the quality and efficiency of internal and external business processes” (Bekkers, 2013, p. 260[26]). The consensus is that most digitalisation efforts in the public sector are focussed on driving incremental rather than transformative efficiencies and innovations (e.g., Chen, Feng and Chou (2013[27]); Madzova, Sajnoski and Davcev (2013[28])). This appears to be the case especially at the local level, where government agencies mainly adopt and exploit technological innovations to achieve improvements in existing processes (Luna-Reyes et al., 2020[29]). Examples include the digitalisation and online availability of forms and documents, online communication with citizens, and online payments of utility bills, fines and taxes (Norris and Reddick, 2013[30]).

Box 5.1. Pro-active family benefits in Estonia

The government of Estonia developed an IT system that aggregates information from various national registries and databases, continuously and proactively offering social benefits to qualifying families and individuals after key life events. The system ensures that all families are automatically and seamlessly offered benefits if eligible – without having to apply for them.

Before the platform was developed, it took on average two hours for a government official to process an application. Now, eligible users simply log-in to the platform and receive the benefits immediately. Given the platform’s success, it is being replicated in other areas of social security in the country.

Source: OECD (2019[31]), Pro-active Family Benefits - Estonia, https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/proactive-family-benefits/.

However, some scholars caution that excessive and often exclusive focus on the exploitative, efficiency-led dimension of digitalisation projects risks limiting their true, transformative potential. A more balanced approach embracing exploration can better serve public organisations in achieving broader goals (Magnusson, Koutsikouri and Paivarinta, 2020[22]; Magnusson et al., 2020[32]; Magnusson, Paivarinta and Koutsikouri, 2020[33]; Matheus and Janssen, 2016[34]; 2016[20]). Successful digital transformations are the foundation for greater simplicity, efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of public services (Greenway and Terrett, 2018[35]).

The paradigmatic shift from e-government to digital government results in an approach to public sector digitalisation with more holistic objectives. The concept of digital government more broadly encompasses “the use of digital technologies, as an integrated part of governments’ modernisation strategies, to create public value” (OECD, 2014[25]). In this view, the optimisation of public services, internal processes and operations through digitalisation in the public sector serve to improve the user experience and strengthen trust in government (Downe, 2020[36]). An example of this broader concept of digital government is the OECD Digital Government Policy Framework (OECD, 2020[37]) (see below).

The example of e-government provides evidence of how enhancement-oriented innovation evolves and how it relates to other innovation facets. While the pursuit of efficiency and effectiveness can drive the spread and implementation of digitisation projects in an initial phase, these can evolve to serve broader objectives and reach more complex goals. Throughout this process, enhancement-oriented innovation and its guiding principles can be a path to other innovation facets by stimulating greater risk taking, openness to new technologies and anticipatory innovation. However, the opposite can also be true: excessive focus on efficiency gains might end up making obsolete processes more efficient. As a result, enhancement-orientation could limit the potential of innovation and prevent more radical change.

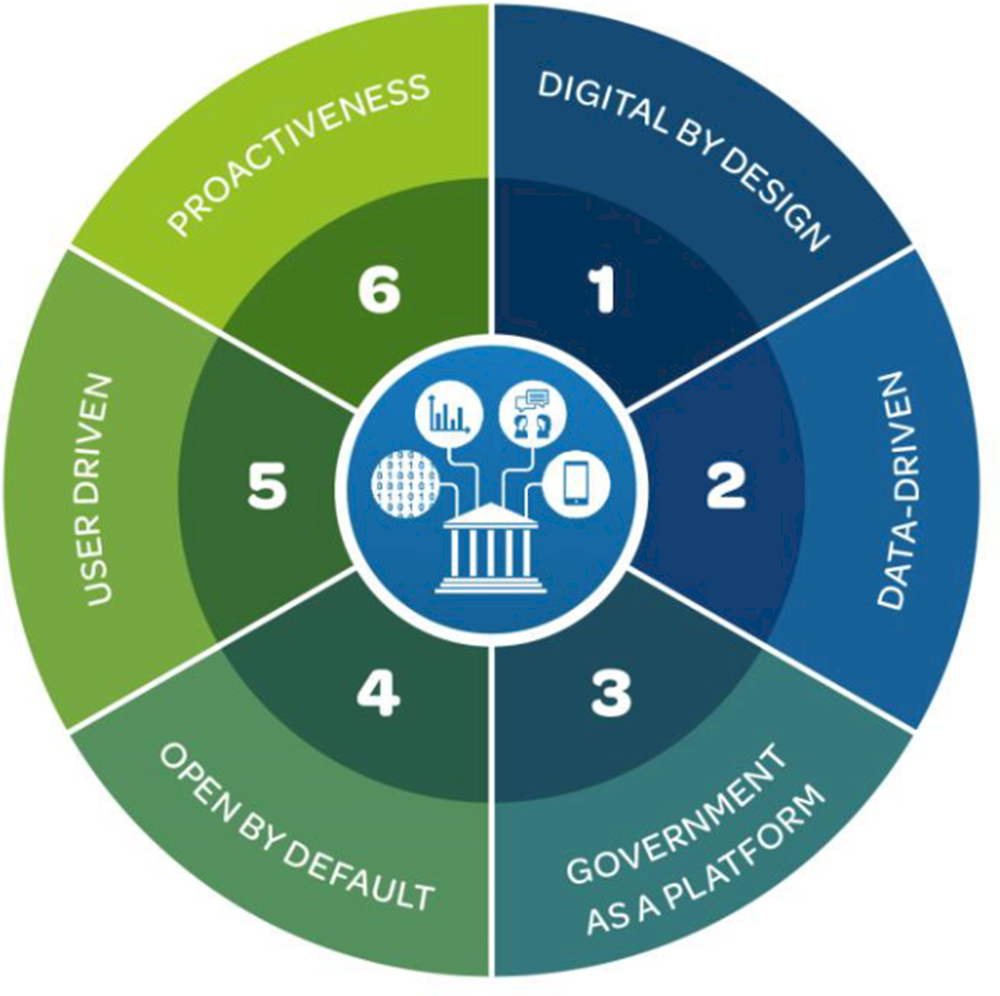

Box 5.2. The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a digital government

The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework (DGPF) was developed based on analysis of peer learning and describes the essential characteristics of a digital government. The six dimensions are: (1) digital by design; (2) data-driven public sector; (3) government as a platform; (4) open by default; (5) user-driven; and (6) proactiveness. The DGPF states that while successful digital transformations are crucial for driving enhancement and efficiency in public sector organisations, they also encompass values such as user-centricity and transparency.

Figure 5.1. Digital government principles

Source: Based on OECD (2014[25]), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406#dates; OECD (2020[37]), “The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a Digital Government”, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

Productivity

The relationship between enhancement-oriented innovation and productivity in the public sector is less clear. Discussion of public sector productivity raises questions around the impact of enhancement-oriented innovation: Do efficiency gains from enhancement-oriented innovation equate to increased productivity? If so, where are the productivity gains realised and how can they be measured?

Distinguishing productivity from efficiency

The discussion of efficiency and productivity gains from enhancement-oriented innovation are hindered by blurred lines in the theoretical and practical distinction between the two concepts. Productivity is "a ratio between the volume of output and the volume of inputs. In other words, it measures how efficiently production inputs, such as labour and capital, are being used in an economy to produce a given level of output" (OECD, 2021[38]). In practice, Dunleavy (2021[39]) defines efficiency as incremental innovation that manifests in cost and service reductions, while productivity relates to more substantive and long-term service improvements (Table 5.2).

Public sector innovations such as introducing common procurement standards or shifting services to digital channels are examples of an efficiency focus that result in short-term, one-time improvements in productivity. According to Tõnurist and Hanson (2020[40]), "These ‘transactional’ improvements can be considered as playing with the quantity of the particular variables in the productivity formula (less input, more output, better outcome), whereas transformational improvements are able to change the variables and/or the underlying formula of how inputs lead to outputs and outcomes.” Innovations that change the input-output equation lead to longer-term productivity improvements, for instance, by reducing the input needed to produce an output (e.g., using shared services to reduce the number of staff required to complete a task) or improving the quality of the outputs (creating electronic tax forms that are easier for citizens to complete) (Dunleavy and Carrera, 2013, p. 12[14]).

Table 5.2. Distinction between productivity and efficiency outcomes from public sector innovation

|

Criterion |

Productivity |

Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

|

Frequency of analysis |

Every year (or more often, e.g. quarterly, episodically in big and ad hoc if data allow), but needs a run of five years (or efficiency reviews say 15 quarters) to show a consistent trend |

Episodically and ad hoc; and incrementally via internal audit |

|

Focus |

Improving substantive service outputs in terms of volume and/or quantity |

Cutting costs or ceasing activities |

|

‘Production frontier’ |

Constantly expanding |

Fixed |

|

Results |

New services, new customers, increase in capital intensity, innovation, stable staff numbers |

Harder/faster work for staff; cutting jobs, worsened working conditions |

|

Mantra |

Focus on finding production system, technology, organisational or service-character changes that meet three goals at once:

|

Do only what we (legally) must, at the lowest possible cost |

Source: Dunleavy, P. (2021[39]), “What public sector productivity is and why it matters”.

Consequently, the impact of enhancement-oriented innovation should distinguish between "discussions about efficiency or value for money" and public sector productivity measured via "systematic accumulation of data on organisational performance" (Dunleavy and Carrera, 2013, p. 12[14]). The Tietokiri project launched by the government of Finland illustrates this distinction (Siltanen and Passinen, 2020[41]). The project uses data to detect the impact of operational practices on productivity increases across government. First, shared services providers (such as the Treasury) collect operational data common to all government departments (e.g., IT spending or procurement) and combine it into a government-wide dashboard. Analysis of the data seeks to understand whether isolated investments lead to broader productivity gains, such as how new office space concepts impact staff sickness and absence. Tietokiri shows that while tracking individual investments shows efficiency gains (e.g., cost saved on real estate), only the analysis of aggregate data can track productivity gains across governments (e.g. higher presence in the government workforce). The outcomes of enhancement-oriented innovation can thus be short-term or longer-term, more or less substantive, and depend on the type of innovation introduced.

Realising and measuring productivity gains

Most OECD research on productivity looks at the private sector, and productivity in the public sector remains under-researched (Lau, Lonti and Schultz, 2017[42]). Yet improving public sector productivity is a political priority for many countries. As public finances remain fragile and the dependency ratio in public services soars (e.g., due to ageing populations), governments must either add resources or maximise productivity (ibid). However, productivity outputs are difficult to define and track (Lau, Lonti and Schultz, 2017[42]), and the relationship between inputs (such as enhancement-oriented innovation) and outputs is not well measured. An increase in input does not necessarily result in increased output (Dunleavy, 2017[43]).

This research finds that, while the links of enhancement-oriented innovation to efficiency can be established, links to increased productivity are tenuous and not guaranteed. Some governments introduced enhancement-oriented innovations systematically to achieve whole-of-government productivity gains (see case study on the Malaysia Productivity Corporation).

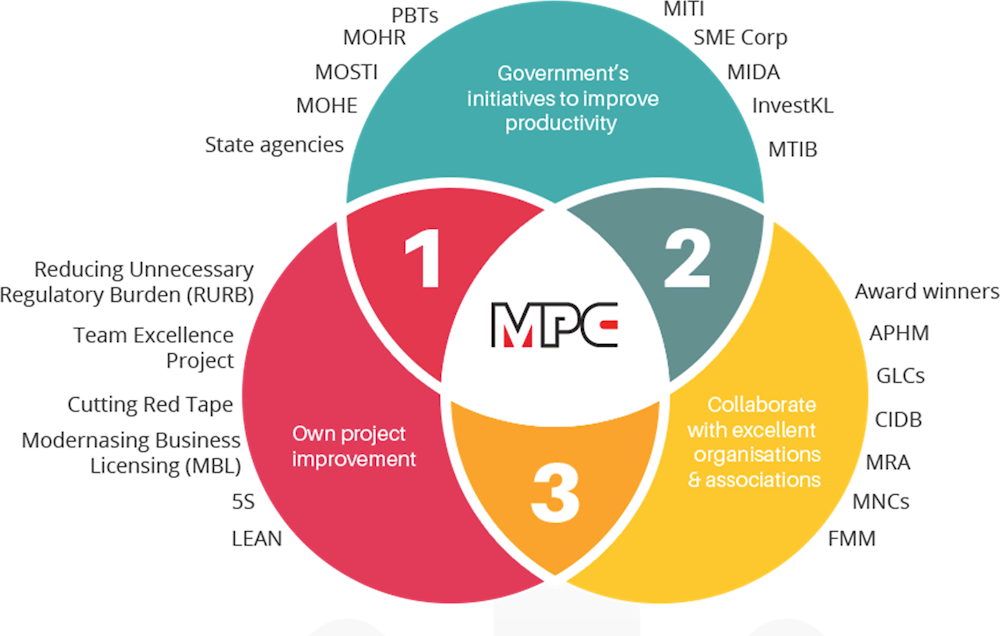

Box 5.3. Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC)

The Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC) is a government organisation set up under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry with the aim of "unlocking potentials of productivity". Through case studies, the MPC introduces public and private organisations to best practices in regulatory reform and the digitalisation of public services to improve productivity. The case studies are available online in the Benchmarking Online Networking Database (BOND) and contain success stories of project improvements that resulted in greater productivity.

Figure 5.2. MPC’s tasks

Source: Malaysia Productivity Corporation (n.d.[44]), About Us, http://bond.mpc.gov.my/bond2/pages/about-us.html.

Applications of enhancement-oriented innovation

Analysis of the literature finds that examples of enhancement-oriented innovation cluster in three categories: (1) process innovations; (2) product or service innovations; and (3) structural innovations (Table 5.3). These derive from previous attempts to categorise public sector innovation types (Bugge, Bloch and Mortensen, 2011[45]; De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[4]; Halvorsen and Hauknes, 2005[24]) and, although they effectively frame enhancement-oriented innovation, they are often observed in more radical and transformative innovation as well. These examples of enhancement-oriented innovation stand out from other innovation types in their focus and compatibility with organisations’ existing processes, products, services or structures. They seek to improve the context in which they are applied rather than aiming to disrupt or question existing systems.

Process innovations

Enhancement-oriented process innovation aims to improve the quality and efficiency of internal and external processes (Bekkers, 2013[26]; De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[4]). Often, process innovations use digital infrastructures “to construct new and more flexible relations and distributed autonomy” within organisations (Øvrelid and Kempton, 2020[46]). Examples are process digitalisation, open innovation and adoption of technologies such as blockchain.

Product and service innovations

Enhancement-oriented product and service innovation improves customers’ use and access to public services (Bugge, Bloch and Mortensen, 2011[45]). This can take the form of one-stop-shops or full-service digitalisation (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Telemedicine in OECD countries: An example of efficiency-led innovation

Telemedicine promises cost reductions, knowledge sharing and patient empowerment, but it entails significant uncertainties and potential for inefficiencies and regional inequalities. Experience from OECD countries shows that most barriers are institutional and cultural rather than technological, and a supportive policy environment for telemedicine must address digital and geographical divides, scale-up through sustained financing, and promote clarity through guidelines. The use of digital tools and platforms, design thinking, and experimentation to deliver medical services can increase inclusivity and user involvement, and the usability and accessibility of medical services.

Source: Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. (2020[47]), “Bringing health care to the patient: An overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries”, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e56ede7-en.

Structural innovations

Enhancement-oriented structural innovation primarily re-thinks how public entities and agencies can be organised better (Bekkers, 2013[26]), including “improvements to management systems or workplace organisation” (Bugge, Bloch and Mortensen, 2011, p. 3[45]). Shared service centres, optimised regulation and adoption of lean management practices are manifestations of this. An example can be found in Denmark, where, in 2008, the government established administrative shared service centres to (1) manage payroll, finance and travel administration for all public employees, and (2) host, administer and maintain IT services for several state organisations (OECD, 2010[48]).The literature includes several examples of process, product and service, or structural innovations, which typically occur where the approach to the optimisation of a system is integrated. For example, Ortiz-Barrios and Alfaro-Saiz (2020[49]) describe the creation of Emergency Care Networks in local healthcare systems in Spain in response to rising demand for emergency services and long wait times for patients. The networks combine the optimisation of technology, workflows and collaboration (Ortiz-Barrios and Alfaro-Saiz, 2020[49]).

Table 5.3. Types of enhancement-oriented innovation

|

Category |

Sub-topic |

Papers |

|---|---|---|

|

Process innovation – improves the quality and efficiency of internal and external processes, especially via the use of digital infrastructures |

Process digitalisation |

Øvrelid and Kempton (2020[46]); Tansley et al. (2014[50]) |

|

Citizen involvement and crowdsourcing |

Carstensen and Langergaard (Carstensen and Langergaard, 2014[51]); Loukis et al. (2015[52]) |

|

|

Open innovation |

Mergel (2015[53]); Niehaves (2011[54]); Pedersen (2018[55]) |

|

|

Innovative technology adoption (e.g., blockchain, artificial intelligence, mobile technology) |

Cagigas et al. (2021[56]); Kuziemski and Misuraca, (2020[57]); Liu and Li (2011[58]); Malhotra and Anand (2020[59]) |

|

|

Product / service innovation – enriches a public sector organisation’s services and/or improves customer experience |

Service digitalisation |

Arfeen, Khan and Ullah (2012[60]); Maphumula and Njenga, (2019[61]); Mittal (2020[62]); Roy (2017[63]) |

|

One-stop-shops |

Poddighe, Lombrano and Ianniello (2011[64]) |

|

|

Innovative technology adoption, e.g., artificial intelligence, Internet of Things |

Kuziemski and Misuraca (2020[57]); Velsberg, Westergren and Jonsson (2020[8]) |

|

|

Structural/organisational innovation – restructures and reorganises management systems in public organisations |

Shared services and management |

Aalto and Kallio (2019[65]) |

|

Quality improvement |

Mättö (2019[66]) |

|

|

Management innovation |

Bello et al. (2018[67]); Fabic, Kutnjak and Skender (2016[68]); Fabic, Kutnjak and Fabic (2017[69]); Moreira Neto et al. (2019[70]) |

|

|

Lean management |

Alosani (2020[71]); Janssen and Estevez (2013[72]); Poddighe, Lombrano and Ianniello (2011[64]) |

|

|

Optimised regulation |

Arriola Peñalosa et al. (2017[73]) |

|

|

Mixed innovations – involves two or more of process, product and service, or structural innovations |

Process and service |

Juell-Skielse and Wohed (2010[74]); Maluleka and Ruxwana (2016[75]); Mittal (2020[62]); Petersone and Ketners (2017[76]) |

|

Process and structural |

Mouzakitis et al. (2017[77]) |

|

|

Process, service and structural |

Ortiz-Barrios and Alfaro-Saiz (2020[49]) |

Main drivers in the public sector

The literature reveals that enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector is motivated by several factors. It can stem from the need to operate on a reduced budget and “do more with less” (Olejarski, Potter and Morrison, 2019[78]). It can be caused by digitalisation and the adoption of new technologies and infrastructures (De Vries, Tummers and Bekkers, 2018[79]). In high-income countries, it can be motivated by the New Public Management (NPM) paradigm pushing public sector organisations to run operations and services more efficiently and at lower cost, provide incentives for performance and increase user-centricity (Damanpour, Walker and Avellaneda, 2009[80]).

Reduction of resources and costs

The role of cost and resource reductions in spurring innovation is a subject of debate. Some authors agree that reduced fiscal capacity is an important variable in explaining public sector innovation (e.g., Bello et al. (2018[67]); Overmans (2018[81])). Others are less optimistic about the role of budget cuts in organisations’ innovative capacity or the positive impact of innovation. Demircioglu and Audretsch's (2017[82]) analysis of the Australian public service finds that lower budgets do not contribute to the likelihood of innovative activity, better explained by factors such as experimentation, a desire to address low performers and the existence of feedback loops. Nevertheless, several authors provide evidence of cost-motivation (e.g., austerity measures) that accompanies enhancement-oriented innovation (De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2015[4]).

Box 5.5. Translation service for migrants in Portugal

Portugal’s High Commission for Migration (ACM) implemented a Telephone Translation Service (STT) that works with a database of 95 translators and interpreters to offer migrants free, immediate or scheduled translation in 68 languages. The service is integrated across public agencies and provides citizens with information on various services, including social security, healthcare, police, and immigration and border services. The challenges identified with implementing such a service include mindset issues (e.g., not knowing where to start when one wants to change a process or a service); structural problems (e.g., dealing with limited staff or budget to bring about change); and user-involvement issues, mostly concerning difficulties faced when trying to involve citizens or civil servants to make sure that innovations match their demands and needs.

Source: High Commission for Migration of Portugal (n.d.[83]), Telephone Translation Service (STT), https://www.acm.gov.pt/-/servico-de-traducao-telefonica.

In describing the implementation of shared management teams in English district councils, Bello et al. (2018[67]) find that budget pressures are an important part of the rationale guiding these types of structural innovations. Similarly, Overmans (2018[81]) explores the response of Dutch municipalities to the growing climate of austerity resulting from the 2007-08 global financial crisis. Overmans finds that, when faced with budget cuts and rising costs, innovation is the main response of local public managers to run their organisations in an efficient and cost-effective way. These conclusions are shared by Sorensen and Torfing (2017[84]), who maintain that the cost savings derived from the public innovation agenda make it an attractive option for governments under fiscal stress. However, not all innovations spurred by budget cuts are structural or strategic. Elliott (2020[85]) reaches this conclusion in exploring organisational change in the UK public sector. Elliott’s analysis based on interviews with public sector managers from Wales and Scotland reveals how austerity and budget cuts only lead to piecemeal change, which is not strategic and does not bring about structural improvements in public sector operations.

New Public Management

Organisations strongly influenced by New Public Management (NPM) adopt enhancement-oriented innovation in the expectation of greater efficiencies, cost reduction and higher performance levels (Diefenbach, 2009[86]; Hood and Dixon, 2013[87]). NPM reforms are often driven by the objective of increasing innovative capacity, saving on costs, and a desire to achieve higher levels of organisational performance and effectiveness in the public sector (Calogero (2010[88]); Damanpour, Walker and Avellaneda (2009[80]); Demircioglu and Audretsch (2017[82]); Wallis and Goldfinch, (2013[89]). The literature reveals how enhancement-oriented innovations resulting from NPM reforms take the form of process and managerial innovations (De Vries, Tummers and Bekkers, 2018[79]; Walker, 2014[90]). NPM leads to the adoption of performance management, cost-efficiency measurement and business case logic tools (see section on tools and methods). Especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, NPM is characterised by frequent outsourcing and contracting of service provision to the private sector (Wallis and Goldfinch, 2013[89]) (see section on enabling factors).

However, the mechanism for increasing internal innovation capacity is usually the creation of market-based incentives, which mostly lead to cost cutting via service or personnel cuts and rarely contribute to increased service quality or internal capacity (Dunleavy et al., 2006[91]). Dunleavy et al. (2006, p. 484[91]) maintain that the “perverse incentives” and short-term managerial savings objectives associated with NPM reforms in the last decades limit rather than stimulate effective administrative change and innovation. For example, NPM favours short-term changes and does not support the development of innovation capabilities.

Some authors are more cautious in evaluating the effect of NPM on public sector innovation. In their analysis of the drivers of innovative behaviour in the Flemish Employment Agency and other Dutch public agencies, Verhoest, Verschuere and Bouckaert (2007[92]) conclude that the pressures brought about by NPM alone are not sufficient to understand the observed public sector innovations. Rather, innovation in these organisations is guided by political pressures and legitimacy threats, and NPM is just one of many factors that drive enhancement-oriented innovation.

The impact of innovations nested in the NPM paradigm is therefore a subject of debate. The authors above did not qualify innovation – radical, incremental or facet-based – in their analysis, meaning that effects related to specific innovation facets are difficult to bring out. Nevertheless, there is a strong argument that NPM favours enhancement-oriented innovation over other types of innovation in the public sector. This is not to say that the conditions for the latter have been ideal, as many opportunities for timely improvements have been missed (e.g., in adopting telemedicine). Although the efficiency-focused nature of these reforms would appear to inevitably lead to enhancement-oriented innovation, the effect of NPM on enhancement-oriented innovation is speculative.

Digitalisation, and new technologies and infrastructures

The literature emphasises the role of ICT and digitalisation in stimulating and driving innovation in the public sector (e.g., Bubou, Japheth and Gumus (2018[93]); Madzova, Sajnoski and Davcev (2013[28])). Many technology-driven innovations fall under the enhancement-oriented innovation facet, with objectives and impacts that include increased effectiveness in service delivery, greater efficiency, and improved transparency within the parameters of existing services and products. Examples include digital tools used in tax administration processes (De Vries, Tummers and Bekkers, 2018[79]; Maphumula and Njenga, 2019[61]), the creation of municipal web portals and mobile applications, the personalisation of citizen services, and the more general use of ICT to enhance strategic planning processes and improve inter-agency partnerships and collaborations (Luna-Reyes et al., 2020[29]). Similar objectives are outlined by Christodoulou et al. (2018[94]), who examine data-driven innovation in the public sector, and highlight how living labs, smart cities and e-participation can increase the quality and efficiency of services, and overall levels of trust in government.

Box 5.6. Singapore’s APEX platform

Singapore developed a whole-of-government platform that establishes common application programming interfaces (APIs) and allows government agencies to share data and services among themselves and with external entities. The initiative aims to increase adoption of API technology within government by simplifying secure data-sharing, making API management user-friendly and increasing the visibility of available APIs.

The platform was developed with the Agile methodology to iteratively and incrementally design, build and validate features. Its success enables public agencies to rapidly deploy APIs, propagating data for consumption for other organisations, and stimulating innovative projects both within and outside the public sector. APEX ultimately enables the interoperability of government systems, enhancing uniform governance, and strengthening consistency and reliable performance.

Source: OECD (2017[95]), APEX – Singapore, https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/9587/.

E-government includes many of these concepts and cases, and is often associated with technological, process, service and organisational innovations typical of enhancement-oriented innovation (Bekkers, 2013[26]; De Vries, Tummers and Bekkers, 2018[79]). However, not all technology adoption and digitalisation projects lead to enhancement-oriented innovation. Organisational structures and existing capabilities can impact the design of technological structures (Bailey and Barley, 2020[96]; Kattel, Lember and Tõnurist, 2020[97]). For example, a heavily centralised organisation might be more likely to implement a command-and-control design in its IT architecture, while an organisation with flat hierarchies might replicate these in their digitalised processes (Kattel, Lember and Tõnurist, 2020[97]). This implies that the drive for enhancement-oriented innovation provided by digitalisation will depend on the context and organisational setting were the projects are implemented.

Box 5.7. Transformational government

Transformational government (t-government) focuses on the “ICT-driven business process reengineering and design” of government operations to achieve e-government objectives (Janssen and Estevez, 2013, p. S2[72]; Weerakkody, Janssen and Dwivedi, 2011[98]). Parisopoulos, Tambouris and Tarabanis (2014[99]) find that t-government is characterised by nine elements: (1) user-centric services; (2) joined-up government; (3) one-stop government; (4) multi-channel service delivery; (5) flexibility; (6) efficiency; (7) increased human skills; (8) organisational change and change of attitude of public servants; and (9) value innovation. Their analysis of European countries reveals that few t-government initiatives exploit the paradigm’s full potential – with an over-emphasis on efficiency, silos and joined-up government (ibid.) typical of enhancement-oriented innovation. T-government faces several impediments to implementation in public sector organisations, including insufficient IT governance and skills, lack of coordination and organisational readiness to business process engineering, excessive fragmentation and technical complexity (van Veenstra, Klievink and Janssen, 2011[100]).

Source: Janssen, M. and E. Estevez (2013[72]), “Lean government and platform-based governance - Doing more with less”, Government Information Quarterly, Vol. 30/Suppl. 1, pp. S1-S8.

Therefore, the literature highlights how enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector is driven by three main factors: budget considerations, digitalisation processes, and NPM logic and reforms. It finds that reactive enhancement-oriented innovation resulting from budget cuts and NPM pressures can be fragmented and lack directionality. In contrast, where digitalisation with strategic intent is the impetus for innovation, the results appear more frequently to be part of long-term, structured change.

Enabling factors

Support structures are the mechanisms established within organisations to sustain enhancement-oriented innovation in the public sector. They are broader than the drivers for enhancement-oriented innovation discussed in the previous section and different from external factors and conditions that support or hinder innovation. The literature shows that support structures which create favourable conditions for enhancement-oriented innovation are: (1) evaluation and auditing; (2) performance measurement systems; (3) capacity building; (4) digital infrastructure and IT governance; and (5) funding and budget structures.

Evaluation and auditing

Auditing and evaluation processes can stimulate enhancement-oriented innovation by prompting improvement in public organisations’ processes and procedures (Kells and Hodge, 2011[101]). This can occur in all three phases of the auditing process. Initially, the prospect of an audit can prompt the need to innovate to improve administrative processes. Later, participation in the auditing process can help staff learn about performance and think about which enhancement-oriented innovations to adopt. Lastly, the findings and recommendations of an audit can provide insights into underperformance and, under certain conditions, lead to performance-enhancing innovations (Kells and Hodge, 2011[101]).

At the same time, performance audits run the risk of prompting an excessive focus on standards, measurement and compliance, which could lead to overly cautious, anti-innovative behaviour and ultimately hinder public service delivery (Bawole and Ibrahim, 2016[102]). Auditing mechanisms alone do not encourage enhancement-oriented innovation by default. Whether auditing stimulates or limits innovation can depend on contextual factors such as the nature of the auditing process (Kells, 2011[103]; Kells and Hodge, 2011[101]; CAF, 2020[104]) (Box 5.8).

Box 5.8. The Common Assessment Framework as a driver of innovation in Vienna

“The CAF is an easy-to-use, free tool to assist public-sector organisations across Europe in using quality management techniques to improve their performance [...] based on the premise that excellent results in organisational performance, citizens/customers, people and society are achieved through leadership driving strategy and planning, people, partnerships, resources and processes.” (EUPAN Secretariat, 2021[105])

The Common Assessment Framework (CAF) provides guidance for modernising public administration, especially through cultural change. Its foundations include ‘Principles of Excellence’ and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. The CAF enables organisations to manage their organisational and cultural change to ensure quality management focused on generating impacts based on values of sustainability and partnership. An example of the CAF in action is the Smart City Vienna project, a process of continuous development that demonstrates the impact of the CAF in the Vienna Public Administration. It is the city’s sustainability strategy, built on the interest of citizens, maximising quality of life through social and technological innovations, and grounded in sustainability and the SDGs.

Source: Sejrek-Tunke, E. (2021[106]), “Vienna city administration: Towards total quality management”; EUPAN Secretariat (2021[105]), “CAF - Common Assessment Frameworkhttps://www.eupan.eu/caf/.

Performance measurement and management

Performance measurement in the public sector usually happens across pre-defined tasks, which can influence public servants' incentives to engage with novel value-added activities (Heinrich and Marschke, 2010[107]). Due to lack of good-quality indicators, performance measurement tends to be output-centric and have difficulty grappling with non-routine situations (Kattel et al., 2014[108]). The inherent bias in performance measurement and management systems thus tends to be efficiency and effectiveness of current systems, rather than trying to quantify something new or uncertain.

Consequently, enhancement-oriented innovation can be facilitated through rigorous performance management evaluation. Fabic, Kutnjak and Skender (2016[68]) find that new systems for measuring and evaluating employees’ performance are a common management innovation in Croatian local government agencies that seek to improve operational performance. Indeed, such activities can contribute to managers’ efforts to respond to low performance by establishing constructive feedback mechanisms to motivate both low- and high-performing employees, and increase the overall likelihood that innovative activity will increase efficiency (Demircioglu and Audretsch, 2017[82]). Importantly, Jacobsen and Andersen (2014[109]) find that the perception of performance management tools can explain their effectiveness in terms of organisational performance. The role of managers and their ability to create incentive structures can therefore influence how employees perceive, react and perform when confronted with performance management programmes and structures (Jacobsen and Andersen, 2014[109]).

Greater capacity to aggregate performance data can also create incentives for enhancement-oriented innovation. According to Rogge, Agasisti and De Witte (2017[110]), increased uptake of big data analytics in government agencies will enhance the effectiveness of performance management systems and performance dashboards, boosting efficiency, increasing productivity and innovation, and optimising the measurement of these variables. Performance dashboards are a useful way to display and communicate such information. These visual display tools provide organisational elements, indicators and objectives in a clear, consolidated format (Maheshwari, Maheshwari and Janssen, 2014[111]). Potential benefits include increased connections between individual activities and overall outcomes, and reduced complexity in organisational practice (ibid.). However, their design and implementation in the public sector depends on local factors and must consider a variety of challenges which, if unaddressed, can have adverse effects on performance and lead to internal disagreements (ibid.).

Box 5.9. Personnel Management Innovation Diagnosis Indicator in Korea

In 2014, the new Korean Ministry of Personnel Management (MPM) was tasked with public management innovation. This increased demand for effective and responsive public personnel management. In 2015, Personnel Management Innovation Diagnosis Indicators were developed to assesses public management innovations in each government organisation and provide feedback to enhance innovation capability. The measurement consists of distinct fields (implementation capacity, balanced public management, human resource development and work environments for improvement), and sub-indicators. With participating government bodies and external experts, the Ministry sets indicators that are adjusted on a yearly basis, and organises workshop to spread best practices and set benchmarks.

Source: OECD (2019[112]), “Measuring public sector innovation: Why, when, how, for whom and where to?”, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Measuring-Public-Sector-Innovation-Part-5b-of-Lifecycle.pdf.

Innovation capacity-building and resource management

In the context of building innovation capacity, public servants can be empowered to take small risks that improve efficiency and effectiveness in their areas of responsibility. Fernandez and Moldogaziev (2011[113]) find that, when coupled with training and development, this discretion can contribute to the diffusion of innovation across and within public sector organisations. Similarly, Overmans (2018, p. 359[81]) finds that psychological slack – defined as public servants’ “ability to redirect brain capacity to new activities and their level of comfort to operate in uncertain environments” – can be crucial in identifying opportunities for efficiency-led innovation at the municipal level. This is important for enhancement-oriented innovation as employees tend to have the most experience with their organisations’ internal processes and services and might thus have the most innovative ideas for how to improve them and enhance their efficiency. These structures can be important for stimulating bottom-up adaptive innovation too (Chapter 5).

In addition, learning processes and knowledge management can impact the innovativeness, operational performance, quality and efficiency of public sector organisations (Al Ahbabi et al., 2018[114]; Balasubramanian, Al-Ahbabi and Sreejith, 2019[115]; Liu and Li, 2011[58]). If learning structures allow for information-sharing and acting on opportunities for innovation and greater efficiency, they can facilitate enhancement-oriented innovation. Learning capacity is the “collective capacity to accumulate tacit and explicit knowledge” and key to stimulating public organisations’ innovative capacity (Boukamel, Emery and Gieske, 2019[17]; Gieske, Van Buuren and Bekkers, 2016[116]). Hashim et al. (2020, p. 5[117]) find that greater learning capacity in (especially multidisciplinary) teams can “boost information sharing, team understanding, and dedication to develop new products or services”.

In this context, knowledge management systems – defined as “systematic approaches to find, understand, and use knowledge to achieve organisational objectives” (Cong and Pandya, 2003, p. 27[118]) – also provide important structures for enhancement-oriented innovation. This can occur via a focus on current processes, people and efficiency, which is typical of knowledge management processes in public sector organisations (Cong and Pandya, 2003[118]; Arora, 2011[119]; Riege and Lindsay, 2006[120]). Knowledge management systems contribute to the pursuit of improvements and a “trial-and-error” culture (Gaffoor and Cloete, 2010[121]) that, in turn, drive enhancement-oriented innovation. However, the private-sector nature of knowledge management methods requires public organisations to adapt them to their context and challenges (Massaro, Dumay and Garlatti, 2015[122]). Indeed, given the accountability and stakeholder relationships that characterise the public sector “blindly applying private sector knowledge management tools and models may be counterproductive” (Massaro, Dumay and Garlatti, 2015, p. 531[122]).

Innovation capacity can also be pooled in centralised governance structures or outsourced to increase efficiency. However, the outsourcing of innovation processes to labs or consultants can lead to lower internal acceptance and less sustainable innovation when compared to those resulting from internal capacity and employees (Boukamel, Emery and Gieske, 2019[17]). Evidence of the efficiency of shared services is found in Aalto and Kallio (2019[65]), who describe the implementation of corporatised shared services in Finnish municipalities as a means for cutting the costs of human resource and accounting functions, and as a gateway for more customer-oriented, efficient municipal support services.

Digital infrastructure and information-technology governance

Digitalisation can stimulate process innovations that make public sector organisations more efficient at an operational level (Øvrelid and Kempton, 2020[46]). Cordella and Paletti describe how the deployment of information and communication technology (ICT) can increase the efficiency of coordination within public organisations by making communication channels simpler and faster and “making internal production more efficient, enhancing standardisation and automation” (Cordella and Paletti, 2018, p. 7[123]). In studying the Internet of Things (IoT) implementation in Danish municipal road cleaning services, Velsberg, Westergren and Jonsson (2020[8]) find that new digital infrastructures can enhance overall efficiency and effectiveness of services by automating existing processes, even if the processes themselves do not change.

Concurrently, however, the lock-in effects of digital infrastructure can mean that governments limit their opportunities to innovate and switch to more effective, interoperable systems (Public Administration Select Committee, 2011[124]). Often there exist no other options on the market (Stuermer, Krancher and Myrach, 2017[125]), nor capability to manage contracts, (Lundell et al., 2021[126]). Large, long-term contracts with specific suppliers can make maintenance costs rise, leading to overall inefficiencies and obsolete systems.

That said, digital teams tend to have a mandate to innovate. The role of Chief Information/Digital Officer typically carries the expectation to reconcile efficiency and innovation to boost organisational performance (Magnusson, Paivarinta and Koutsikouri, 2020[33]). The governance of new digital infrastructure is therefore often geared towards generating the benefits expected of digitalisation (e.g., an increase in the number of cases handled), and proving that investment in digitalisation can lead to effective, enhancement-oriented outcomes and innovation (Magnusson, Paivarinta and Koutsikouri, 2020[33]) (Box 5.10).

Box 5.10. Digitalising tax services in Austria

The Austrian tax administration launched a digital tax administration and chatbot integration on the FinanzOnline platform. FinanzOnline showcases more than 20 years of incremental improvements and is the most used e-government portal in Austria. The customer service strategy of the tax administration is to present a single front-end to all target groups through the FinanzOnline platform. Most recently, through a new implementation approach that focuses on the user rather than working around legal changes, the team created applications for smartphones, and the platform started supporting video chats and was integrated in the broader ICT landscape of the Austrian government.

Source: CEF Digital (2019[127]), “Austria's FinanzOnline service”, https://ec.europa.eu/cefdigital/wiki/display/CEFDIGITAL/2019/07/25/Austria%27s+FinanzOnline+service.

Funding and budget structures

Increasingly constrained public finances have led governments around the world to focus budgetary evaluation on efficiency and effectiveness (Maroto, Gallego and Rubalcaba, 2016[128]), and develop funding programmes with cost-saving targets (Bhatia and Drew, 2006[129]). An analysis of Norwegian municipalities by Madsen, Risvik and Stenheim (2017[130]) found that performance-oriented budgets are among the most widely adopted tools to improve organisational performance. Although the success of efficiency- and performance-based evaluations in the public sector is limited (Maroto, Gallego and Rubalcaba, 2016[128]), they can create the conditions for implementing efficiency-led innovations, possibly leading to their prioritisation over other innovation facets.

Limited budgets can also push organisations to innovate within existing structures, optimising processes and adopting methods to improve outputs without increasing costs and resources, and avoiding structural change (Antony, Rodgers and Cudney, 2017[131]). Moreover, the enhancement-oriented focus of many public sector ICT and digitalisation projects entails that funding programmes in this field – which are increasingly widespread in the US (Vonortas, 2015[132]) and Europe (European Commission, 2020[133]) – favour enhancement-oriented innovations. A public sector innovation scan of Denmark conducted by the OECD OPSI revealed the benefits of making a business case for innovation to secure funding for enhancement-oriented innovation (OECD, 2021[134]). The country’s budgetary processes – based on private sector measures and project-oriented funding streams – were found to favour incremental and enhancement-oriented innovation at the expense of broader and more complex facets, such as mission-oriented innovation (OECD, 2021[134]).

Tools and methods

Enhancement-oriented innovation can be supported using tools and methods that enhance the public sector's ways of working, such as lean and Six Sigma methodologies, or project management and quality improvement methods. It can also be facilitated using tools that make ideation and delivery of enhancement-oriented innovation more efficient, such as open innovation or behavioural insights approaches. These tools, described below, represent trends in the literature, but they are not exhaustive of the methods that can support enhancement-oriented innovation.

Lean and Six Sigma methodologies

Originating from the car manufacturing sector in the 1980s, lean methodologies entail optimising costs and reducing waste via a focus on customer needs and value (Bhatia and Drew, 2006[129]). A subset of these, Six Sigma approaches entail a five-part DMAIC (Define-Measure-Analyse-Improve-Control) methodology, through which organisations identify issues and implement solutions (Antony, Rodgers and Cudney, 2017[131]). The rapid diffusion of lean methods in the public sector over the last decades prompted debate in public governance literature over their effectiveness and appropriateness (Madsen, Risvik and Stenheim, 2017[130]). According to Elias (2016[135]), lean approaches in non-competitive contexts require adaptation to be effective and incorporate a view of customer value compatible with the public sector and in line with citizens’ expectations. Other authors are less cautious, maintaining that lean approaches “can be embraced by all public sector organisations to create efficient and effective processes to provide enhanced customer experience and value at reduced operational costs” (Antony, Rodgers and Cudney, 2017, p. 1402[131]).

The cost reduction and optimisation focus of lean methods foster process innovations typical of enhancement-oriented innovation. Implementation of lean approaches by the Dubai Police was effective for stimulating process innovation, boosting organisational performance and improving overall quality of service (Alosani, 2020[71]). Lean principles were also found to improve the timeliness and effectiveness of public healthcare services (Ortiz-Barrios and Alfaro-Saiz, 2020[49]), with reductions in patient wait times at an Indian hospital of up to 57% (from 57 to 24.5 minutes) (Antony, Rodgers and Cudney, 2017[131]). Moreover, lean approaches in a Scottish local government council contributed to the creation of new data collection processes that cut costs and enhanced productivity, saving the council over £60,000 per year (ibid.).

Lean approaches can therefore be a response to budget pressures in local administrations, leading to the creation of one-stop-shops and other service innovations with potential to increase efficiency and improve identification of citizen needs (Poddighe, Lombrano and Ianniello, 2011[64]). Further, lean methods inspire the ‘lean government’ approach: a platform-based public governance paradigm of involving external actors in public policy processes to deliver services by “doing more with less” (Janssen and Estevez, 2013[72]). To deliver value to citizens with fewer resources, the approach enhances innovation by coordinating information flows, mobilising actors to stimulate coordination, and constantly monitoring operations (Janssen and Estevez, 2013, p. S1[72]).

Project management and quality improvement methods

An example of quality improvement and management methods in enhancement-oriented innovation is the Common Assessment Framework, a tool to help European public organisations improve performance using knowledge management and other ways to enhance effectiveness and customer orientation (EUPAN Secretariat (2019[136]); see also the Common Assessment Framework (CAF, 2020[104])). Although some authors express doubts about integrating quality management with innovation, a survey of Swedish public servants analysed by Palmi et al. (2020[23]) found that the two can concur. If well managed, Total Quality Management practices can strengthen the conditions for innovation in the public sector (Palmi et al., 2020[23]) and ultimately stimulate enhancement-oriented innovation. Further proof is found in Mättö's (2019[66]) analysis of quality improvement at a municipally owned real-estate management organisation in Norway. Implementation of the CAMP (collaborative approach for managing the project cost of poor quality) method helped identify shortcomings in organisational practices, and generate ideas and administrative and technological changes to boost their effectiveness (Mättö, 2019[66]).

There are, however, concerns about the approach to its implementation. In the private sector, excessive focus on customer-related practices, typical of total quality management, can lead to merely incremental innovations and ultimately hinder organisations’ creativity (Honarpour, Jusoh and Nor, 2018[137]). Similarly, in public organisations, excessive focus on costs and efficiency can limit the long-term, anticipatory innovation capacity of organisations, and limit their portfolio of innovations to enhancement-oriented innovation.

Organisational processes for quality management are another way public organisations optimise operations amid fiscal distress (Zokaei et al., 2010[138]). Among these, the PRINCE2 approach divides processes into packages and streams to focus on their interdependencies and their timely, on-budget completion (Bartlett, 2017[139]). Developed by the UK Central Computer and Telecommunications Agency (CCTA) as a standard for ICT project management in the UK government, the tool is hailed for contributing to project success and innovativeness in the private sector (Saad et al., 2013[140]; Yakovleva, 2014[141]). However, evidence of its effects on public sector innovation is inconclusive, with some dubbing it too focused on cost monitoring to bring about creative and innovative solutions (Bartlett, 2017[139]).

Box 5.11. Procurement pre-certification for innovative research in Korea

In 2020, South Korea redesigned its public procurement model in the ICT field, enabling the Ministry of Science and ICT to mobilise stakeholders to proactively shape innovation sourcing.

The platform fast-tracks implementation of public procurement for innovative products by pre-certifying them via expert panellists from other ministries, thereby breaking silos and increasing the process’ efficiency and timeliness. Over 3 000 expert panellists covering 24 technical sub-fields are involved in pre-certifying products for innovation procurement. This is in addition to assistance available from researchers and scientists participating in 60 000 public research and development projects annually.

The innovation improved the quality of services to citizens, adding credibility to the public procurement process and delivering more innovative ICT solutions with greater potential socio-economic impacts.

Source: OECD (2020[142]), Procurement Precertification for Innovative Research, https://oecd-opsi.org/innovations/procurement-precertification-for-innovative-research/.

Service blueprinting is another process-modelling approach related to quality improvement and enhancement-oriented innovation. It involves graphical representation of an organisation’s service delivery process, aiming to promote creativity in problem-solving and clarify the needs of both the service’s users and the staff behind it (Radnor et al., 2014[143]). The technique has potential for higher education, helping universities redesign their courses and administrative processes, and improving students’ overall satisfaction with their academic experience (Ostrom, Bitner and Burkhard, 2011[144]). Service blueprinting was used by the University of Derby to redesign student enrolment, improving administrative efficiency (via faster processing of student matriculations) and student satisfaction (which increased from 32% to 68%) (Radnor et al., 2014[143]). By highlighting these two dimensions of services’ delivery, the approach clarified the “central role of the student (service user) in co-producing the enrolment process and the impact that this role had upon the efficiency and effectiveness of this process” (Radnor et al., 2014, p. 419[143]).

Open innovation

Open innovation and citizen crowdsourcing entails opening public organisations’ innovation processes to external stakeholders, using knowledge from outside organisational boundaries to improve processes and services, increase legitimacy, and strengthen citizen participation in the public sphere (Niehaves, 2011[54]; Pedersen, 2018[55]). Although the absence of competitive market logics in the public sector offers a better context for opening innovation processes than in the private sector, public open innovation initiatives often result in less radical outcomes (Mergel, 2015[53]). The approach tends to produce innovations focused on increasing the effectiveness and efficiency of public service delivery, enabling public organisations to understand the needs of citizens and cutting the costs of innovation processes (Mergel, 2015[53]). Open innovation approaches tend to be most attractive for their ability to solve complex issues with limited personnel and constrained budgets (Seidel et al., 2013[145]).

Pedersen (2018[55]) finds that a substantial number of initiatives in public open innovation tend to focus on optimising existing resources and using citizen knowledge to improve the effectiveness of public services. Examples include “apps that help parents track school buses”, “apps that help citizens locate bicycles provided by local government for sharing” or “apps that through nudging focus on getting drivers to drive safely” (Pedersen, 2018, p. 5[55]). Other examples of open innovation are civic hackathons: events that bring together computer programmers to collaborate on software or ideas that address a specific public challenge (Almirall, Lee and Majchrzak, 2014[146]; Mu and Wang, 2020[147]). Hackathons can help governments achieve greater performance efficiency and public accountability, and lower the costs of contracts with large ICT companies (Yuan and Gasco-Hernandez, 2021[148]).

Behavioural insights

The Behavioural Insights (BI) approach can help public organisations be more efficient and increase the cost-effectiveness of their operations. Notably, work by the UK Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) helped the British tax agency (HMRC) collect an additional £200m via the mere insertion of the sentence “Nine out of ten people pay their tax on time” in solicitation letters to taxpayers (Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team, 2012[149]).

Box 5.12. Behavioural sciences in healthcare in Australia

In the health sector, BI-informed letters were applied in a trial involving Australian general practitioners (GPs) to diminish the number of antibiotic prescriptions and reduce the risk of antimicrobial resistance and medicine ineffectiveness. Consisting of letters sent to GPs with information on the dangers of antimicrobial resistance, the intervention led to an estimated reduction of 126 352 prescriptions after six months, equivalent to a reduction of 9.3% to 12.3% based on the different letter types.

Source: Australian Government (2018[150]), “Nudge vs Superbugs: A behavioural economics trial to reduce the overprescribing of antibiotics”, Behavioural Economics Team.

BI were applied in several experiments in Australian hospitals, in which behaviourally informed reminder letters and text messages ahead of patients’ appointments showed potential to generate significant cost savings (NSW Government, 2019[151]). Behavioural 'nudges’, or "behavioural science techniques for changing individual behaviour in pursuit of policy objectives”, have been useful to incentivise citizens towards desired outcomes in both more effective and cost-efficient ways compared to traditional economic incentive tools (Benartzi et al., 2017, p. 1041[152]).

An important element of the BI approach to public policy is the concept of ‘sludge’, defined as “excessive or unjustified frictions that make it difficult for consumers, employees, employers, students, patients, clients, small businesses and many others to get what they want or to do as they wish” (Sunstein, 2020, p. 3[153]). Although conceptually underdeveloped, Sludge Audits can be effective in enhancement-oriented innovation to understand an organisation’s transaction costs, identify the type of sludge embedded in its operations and evaluate the cost of these frictions (Sunstein, 2020[153]; Shahab and Lades, 2021[154]).

Skills and capacities

Knowledge and skills can promote better understanding of public organisations’ problems, foster public servants’ capacity to devise solutions to them (Fernandez and Moldogaziev, 2011[113]) and thus contribute to enhancement-oriented innovation. The absence of market feedback mechanisms in most public sector dynamics leads to greater reliance on internal capabilities to create value and remain relevant (Clausen, Demircioglu and Alsos, 2020[155]), heightening the importance of building capacity and skills. The literature reviewed revealed two distinct, yet interconnected categories of skills: employee skills, and leadership and managerial skills.

Employees

Enhancement-oriented innovation processes can benefit from the digital skills and learning capacities of public sector employees.

Digital and ICT skills

As digital technologies spread throughout the public and private sectors, the digital and ICT skills of public employees become ever more important to guarantee that services are delivered effectively and in line with citizens’ expectations (OECD, 2020[37]). Importantly, public servants’ digital skills contribute to more effective knowledge transfers, which help limit organisational inefficiency and break silos (OECD, 2021[156]) that may hamper innovation. Governments’ investment in the skills and data capabilities of its employees can maximise the benefits of innovative technologies for the efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery (Mittal, 2020[62]).

Investing in ICT capacity and ensuring that all staff – not just technology experts – possess sufficient knowledge about the role of technology in enhancing government services and processes can lead to better design and delivery of public policies (UK House of Commons, 2011[157]). Public officials’ user skills can also “spread a digital mindset throughout the public sector workforce” (OECD, 2020, p. 10[37]) and ensure that the productivity and efficiency potential of innovative technologies are fully exploited. This is relevant to public employees’ knowledge skills in the field of data (OECD, 2021[156]): fostering an understanding of the sourcing and use of data in public servants’ everyday work can improve operational effectiveness and increase public value (OECD, 2021[156]).

Box 5.13. Escola Virtual: Online training in digital tools for engaging the public in Brazil

Investment in training public servants can develop the skills and tools for a responsive, proactive digital government that gathers insights into user needs, and facilitates citizens’ engagement and access to real-time information. The Brazilian National Public School of Administration (Escola Nacional de Administração Pública or ENAP) developed Escola Virtual, a platform with free online courses open to public servants and citizens seeking training in public services.

Escola Virtual offers courses covering areas such as management, innovation, commissioning, information technology, web design, open government, and data mining and analysis. The platform can ensure that public servants respond quickly and effectively to public requests, and that innovative technologies are employed to satisfy citizens’ evolving needs and contribute to public value.

Source: OECD (2020[37]), “The OECD Digital Government Policy Framework: Six dimensions of a Digital Government”, https://doi.org/10.1787/f64fed2a-en.

Learning capacities

Gieske, Van Buuren and Bekkers (2016, p. 11[116]) distinguish between first-order learning, taking place “within existing mind sets, assumptions, and norms” and second-order learning, focused on “changing underlying assumptions” of how the organisation operates. In the context of enhancement-oriented innovation, first-order learning is particularly relevant as it can optimise current processes and improve them via existing knowledge resources. At the individual level, learning capacity can be characterised by “tolerance of ambiguity and change, openness to experience, unconventionality, and self-reflectiveness” (Gieske, Van Buuren and Bekkers, 2016, pp. 11-12[116]), which contribute to the innovative capacity of civil servants. At the organisational level, learning capabilities can be stimulated by knowledge management and learning processes that improve organisational performance, reconfigure existing resources (Luna-Reyes et al., 2020[29]) and enable enhancement-oriented innovation.

Leadership and management

Leadership skills are another important capacity for the spread of enhancement-oriented innovations in public sector organisations. Standardisation in the innovation profession is led by the International Organization for Standardisation (ISO), which developed the ISO 560000 series to support the development of organisations’ and their leaders’ innovation capabilities (Hanson et al., forthcoming[158]). This later inspired Vinnova, Sweden’s innovation agency, to develop its Innovation Management Support Programme, offering professional training and certification for public organisations and innovation professionals (Hanson et al., forthcoming[158]) (Box 5.14).

Box 5.14. Innovation management support in Sweden

Vinnova, Sweden’s Innovation Agency, supports public sector entities, companies, non-government and civil service organisations to undertake innovation. This support spans several domains, including financial (EUR 310M annually) and capability-building, and is a core part of the agency’s role. Through the support provided, Vinnova aims to secure and strengthen the effectiveness and longevity of innovation. In one way, this is operationalised through the Innovation Management Support Programme (IMSP) focused on realising and improving outcomes for Vinnova-funded innovation projects.

A growing practice is forming around innovation management and becoming more formalised. It looks at the systematic management of and support for innovation, and how they can be operationalised. Efforts at the international level aim to standardise the practice of innovation management, but it is not yet widespread in public sector administrations.

IMSP was initiated in 2018 as a pilot programme. Its aims included: strengthening the capacity and processes of organisations and Vinnova-funded projects to innovate effectively; encouraging cross-sector collaboration between organisations to overcome silos and lock-ins; creating the conditions for creativity and innovation to flourish; and providing expertise and coaching to innovation partners. Supports were packaged and delivered in modules based on a needs assessment. At first, support focused on several diverse yet specific projects and initiatives.

In 2021, the IMSP began focusing more broadly on Vinnova’s strategic priority areas (missions) to address long-term, complex and horizontal societal challenges. Recognising this, Vinnova now experiments with structures to support multi-actor action and research, and encourages its funded organisations to engage both in projects and their underlying policy, governance and systems.

Source: Hanson, A. et al. (forthcoming[158]), “Innovation management in the public sector: The case of Vinnova Sweden’s Innovation Management Support Programme”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Public sector managers are central to coordinating and initiating process innovations (Walker, 2014[90]), and to creating conditions that stimulate the creativity of employees to encourage change (Damanpour and Schneider, 2009[159]). In line with the characteristics of enhancement-oriented innovations, management support is a strong driver of organisational performance, enhancing effectiveness, efficiency and accountability in e-government systems (Chen et al., 2019[160]).