New models are needed to connect public challenges on one side to decisions of appropriate interventions on the ground that leverage innovation, on the other. This chapter describes the underpinnings of the OECD’s Public Sector Innovation Facets model, its theoretical foundations and connection to public sector values. Directionality and certainty are the dimensions that influence the taxonomy of public sector innovation when it is described in a strategic, action-oriented way. Public value theory is used to connect the purpose of innovation to substantive value that governments aim to achieve. Through theoretical and empirical work undertaken by the OECD, a model for public sector innovation is introduced, encompassing mission-oriented, enhancement-oriented, adaptive and anticipatory approaches.

Tackling Policy Challenges Through Public Sector Innovation

1. Connecting purpose with solutions - Introduction to the Public Sector Innovation Facet model

Abstract

Background

A growing need for public sector innovation

The social, economic and ecological challenges that confront societies today require novel solutions from the public sector. As governments explore how to adapt the foundations of governance and democracy for the 21st century, innovation is becoming an imperative for staying ahead of the curve. In a context of high volatility and complexity, mastering innovation becomes critical to continually developing and delivering solutions that meet the fast-changing needs of the public (OECD, 2017[1]).

As governments become aware of the need to mitigate and leverage the high rate of societal and technological change, they remain ill-equipped to innovate and anticipate signals from the external environment before possible challenges become realities (Tõnurist and Hanson, 2020[2]). Many approaches to public sector innovation attempt to retrofit business innovation models to the public sector, leading to misapplied methods and incompatible measurement, especially in comparative studies between governments, public organisations and sectors (OECD, 2019[3]).

While the OECD finds governments doing exciting things that demonstrate the ever-present potential for innovation (OECD, 2020[4]), innovation practice remains inconsistent and unreliable. It is neither supported nor occurs systematically. The OECD’s and other international databases record increasing evidence of innovative approaches in the public sector.1 However, codification of this “craft” knowledge into practical guidance for making public sector innovation happen is limited. Public servants across OECD countries demand more in-depth knowledge about the approaches, techniques and tools to identify, generate, implement, evaluate and diffuse public sector innovation.

Responding to this need, this report offers insights on a new action-oriented model supporting decision making based on the Public Sector Innovation Facets model.

The objective of a model for public sector innovation

The Public Sector Innovation Facets model systematises the approaches and instruments that governments use to drive public sector innovation. The goal is to connect these to strategic aims in the public sector (e.g., solving problems, making the public sector more efficient and effective, adapting to needs and preparing for future risks). It investigates questions such as: What types of public sector innovation exist? How are innovative ideas generated in the public sector? Which methods are used to support investment in innovative projects? What capacity and resources are required for public sector innovation? Which tools do public sector organisations use to identify threats and/or opportunities in their external and internal environments?

The model emerges from the need to provide decision-makers with underpinnings and evidence for public sector innovation, and to show that systemic support for innovation is possible. However, to make it work, the varied aims and functions of innovation must be recognised. The model supports governments’ innovation efforts by building and refining conceptual frameworks, and developing innovation capacities to accelerate learning, navigate uncertainty and manage high level of risks. Consequently, the main objectives of the Public Sector Innovation Facets model are to:

Create a knowledge base on conceptual frameworks and approaches to innovation in the public sector that acknowledge the varied strategic aims of innovation.

Build an action-oriented innovation theory anchored in empirics, evidence, and based on peer-to-peer exchange, international practice and knowledge-sharing.

Collect an empirical evidence base using case studies (at national and local government level) on different approaches to innovation.

Develop “How-to” guidance, toolkits and training material for designing, supporting and implementing innovative solutions in government.

Structure a portfolio approach to support innovation strategy, decision-making and management of multiple types of innovation.

The Public Sector Innovation Facets model was developed by the OECD Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI), and synthetised in different formats in 2018.2 The model covers four types of innovation – mission-oriented, anticipatory, adaptive, and enhancement-oriented – based on the directionality or the level of certainty connected to the innovation process (the conceptual origins of the model are described in 1.2 outlined below). The theory behind the Public Sector Innovation Facets model was tested with member countries and based on empirical evidence derived specifically from the public sector together with government partners (OECD, 2018[5]; 2019[6]).

It builds on OPSI’s previous work on the key determinants of system change in national public services (the innovation determinants framework) and the typology of innovative responses to public service challenges (resulting in the innovation facets model) (Kaur et al., 2022[7]; OECD, 2018[5]). The research conducted combines action research and co-design (learning from public sector innovation reviews and ongoing innovation cases while participating in their development) and user-specific, change-oriented approaches (meaning that the usefulness to public managers and action-oriented approach was central to theory development). To develop, iterate and test this model in practice, OPSI worked with internationally recognised centres of expertise on public sector innovation. OPSI facilitated practice-led reflections on specific innovation types across a broad range of EU and non-EU countries between 2018-2021 including Sweden, Brazil, Norway, Finland, Israel, Denmark and Latvia (OECD, 2019[6]; 2021[8]; 2021[9]; 2020[10]). Collaborations with public sector organisations served to prepare case studies and learning material from their direct experiments and experiences with innovation practices. Core research partners co-designed work and co-authored outputs, while project partners experimented with the theoretical model and mechanisms to provide peer feedback and empirical validation. Expert observers and peers provided critical analysis and feedback, advised on integrating research and lessons from experimental practice, contributed case study content, and participated in events.

Public Sector Innovation Facets: A conceptual model

Innovation in the public sector can take many forms. Over years of research at the system level of public sector organisations, the OECD’s Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI) developed a multi-faceted innovation model.3 This section will cover the theoretical underpinnings of the model and its linkages to innovation theory.

OPSI defines public sector innovation as “the process of implementing novel approaches to achieve impact” (OECD, 2017[11]). In the broadest terms, public sector innovation comprises three components: novelty, implementation and impact. This definition takes Schumpeter (1934[12]) as its starting point: new combinations of new or existing knowledge, resources, equipment (“novelty”), and other factors with the aim of commercialisation or application (“implementation”). While private sector innovation usually aims to gain competitive advantage, the same metric cannot be applied in the public sector. Thus, “impact” usually means a shift in public value (OECD, 2019[13]). In general, public value represents a normative consensus of prerogatives, principles, benefits and rights that can be attributed to both governments and citizens (Jørgensen and Bozeman, 2007[14]), and linked to a variety of values like effectiveness, transparency, participation, integrity and lawfulness. Not all public value has a clearly distinguishable cost/monetary benefit dimension (Tangen, 2005[15]). Hence, not all public sector innovation projects are developed with efficiency or productivity as a goal (Kattel et al., 2018[16]).

This definition of innovation in the public sector distinguishes it from everyday changes in organisations. For example, prototypes, pilots and experiments are often framed as innovation in the public sector, but they cannot be considered as such de facto. This also sheds light on the limits of labs in the public sector that do not factor implementation into their work (Tõnurist, Kattel and Lember, 2017[17]; McGann, Blomkamp and Lewis, 2018[18]). This issue becomes bigger as the work and funding of innovation become more project based and impacts are not scaled up, diffused or even evaluated (OECD, 2018[19]) (Chapter 2 discusses this in more detail, in the context of innovation portfolios). Thus, it is difficult to know which public value shifts beyond the obvious – positive and negative – innovation brings about. Often this is a matter of perception, rather than fact (Thøgersen, Waldorff and Steffensen, 2021[20]).

Beyond general issues with conceptualising innovation in the public sector, there are ways to classify innovation below the broad Schumpeterian definition. For example, innovation can be defined by its explorative or exploitative nature (e.g., transformative or sustaining innovation (Christensen, 1997[21])), extent of change (e.g., radical or incremental innovation (Freeman and Perez, 1988[22])), object (e.g., product, service, process, business model innovations etc. (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018[23])), or input costs (e.g., frugal innovation or reverse innovation (Hossain, 2018[24]; Govindarajan and Euchner, 2012[25])). Radical innovation can be subdivided into path-breaking, first-mover, pioneering or lead innovations (Klarin, 2019[26]) and so on. These innovation types have different approaches, support system, tools and methods.

With the myriad of innovation approaches, which classification should public sector organisations rely on to support innovation in government? The answer depends on whether the purpose is descriptive (to explain why things happen) or directive (to produce an innovative outcome and guide, govern or influence it). A lot of literature on private sector innovation addresses why innovation happens (how innovation systems emerge and operate, which patents set new technology pathways etc.). Innovation knowledge here is generally defined as the study of how innovation takes place, the important explanatory factors, and social and economic consequences (Fagerberg, Fosaas and Sapprasert, 2012[27]). The OECD has several public sector models with a descriptive purpose, for example the public sector determinants model (OECD, 2018[5]) and the anticipatory innovation governance model (Tõnurist and Hanson, 2020[2]). While many academics aim to explain if and why innovation in the public sector happens (De Vries, Bekkers and Tummers, 2016[28]), the literature on public sector innovation concentrates on practical issues and policy advice, such as whether innovation labs should be set up, how to utilise innovation in policymaking, and what barriers need to be tackled (Cinar, Trott and Simms, 2019[29]; Lewis, McGann and Blomkamp, 2020[30]; Bason, 2018[31]; Pólvora and Nascimento, 2021[32]). This is partially connected to the background of the researchers involved; often situated in public policy, public administration or policy design etc. aiming to improve governance (van Buuren et al., 2020[33]; Demircioglu, 2017[34]). While practical, innovation is still treated in these analyses in a fairly uniform manner, at most emphasising the importance of service innovation over product innovation or the internal-external nature of innovation in the public sector (Chen, Walker and Sawhney, 2020[35]). Recent systematic review by Buchheim, Krieger and Arndt (2020[36]) shows that there has not been enough attention on different innovation types in public sector organisations and public sector managers have not been heedful of different innovation characteristics. Hence, both academic research and practical application of innovation in the public sector has some rather large blind spots that make it difficult to steer innovations especially on the organisational level. This is invariably because innovation in the public sector is a much newer topic compared to private sector and is not as advanced domain in terms of both research and practical application. Furthermore, for a long time doing things ’innovatively’ was not seen core tasks for the public sector; while competitive advantage in the private sector has always legitimised innovative action. This report tries to take a step further and compile an evidence base around public sector innovation that heeds to the different purposes of innovation.

As a policy advisor, the OECD is interested in the strategic outcomes of innovation and the ability to steer it toward governments’ goals. Hence, the proposed classification is clearly more directive than descriptive, although a lot of practical work in countries has been already done (see previous section) to understand how and why innovation happens in the public sector context. There are also practical needs as to why directive models that help strategically steer innovation efforts in the public sector are needed.

Dimensions of innovation

Because the outcomes of public sector innovation cannot be as clearly defined as in the private sector (Kattel et al., 2018[16]), there is a need to make a practical case that legitimises the process. This is amplified by the belief that public sector employees are risk-averse and less innovative due to individual characteristics and selection effects – though little empirical evidence exists to back this claim (Lewis, Ricard and Klijn, 2018[37]). Risk and uncertainty connected to innovation in the public sector often become a central issue in addition to other environmental barriers that influence the types of innovation attempted (Cinar, Trott and Simms, 2019[29]; Cinar, Trott and Simms, 2021[38]). When the starting point for public sector innovation is more directive, and strategic action becomes the principal concern, two dimensions of innovation come into focus:

1. Directionality: how much top-down steering of innovation is desirable

2. Certainty: how much uncertainty the organisation can tolerate and how much emphasis to place on stability versus more radical change

These dimensions create a two-by-two matrix in which to classify public sector innovation (Figure 1.1). Though a simplification, it helps see innovation taxonomies from a strategic action perspective of how much direction is set and how high is the risk tolerance or need to engage with uncertainty.

Figure 1.1. Axes of classification for public sector innovation

Note: The axis points to increased certainty (to the left) and directionality (vertically).

Directionality has been a topic of debate for the past decade in the field of innovation policy, usually aimed at simulating innovation outside the public sector (Edler and Boon, 2018[39]). With focus on sociotechnical transitions, responsible innovation and the need for innovation to contribute to societal goals, new terms such as “mission-oriented”, “policy-induced” and “challenge-led” innovation, and dedicated innovation systems have entered the discussion (Hekkert et al., 2020[40]; Thapa, Iakovleva and Foss, 2019[41]). Setting a direction requires governments to pay more attention to policy coordination, and ensure consistency, coherence and comprehensiveness across policy mixes.

Does that mean all innovation should be directed from the top? Arguably not. Room should remain for bottom-up novelty, creation and deployment, illustrated by the increased interest in adaptive innovation theory (Kirton, 1976[42]) and complex adaptive systems (Dooley, 1997[43]). Simply put, however clear the socio-economic goals, robust the targets or well-framed the challenges, complex systems can change these and raise barriers not captured or identified before. Hence, supporting creativity, problem-solving and adaptability is as important to innovation as is setting concrete goals.

However, the importance of both ends (directed and undirected) of the directionality spectrum is poorly understood in government contexts. The public sector, dependent on dominant administrative, ideological trends and paradigms, often views and values directionality differently at different times. Negative experiences and policy lock-in spurred decades of mostly undirected policies where the best-articulated ideas win support and investment from the public sector (Lindner et al., 2016[44]; Kattel and Mazzucato, 2018[45]). A recent normative turn emerging through the influence of international organisations such as the European Commission is again putting directionality at the forefront of the agenda (Mazzucato and Kattel, 2020[46]). Nevertheless, it is important to stress that both goal-oriented and bottom-up activity – responsive innovation that is not directed but adaptive – should be supported in the public sector.

Certainty is the other dimension of innovation to examine. Innovation can be defined by its explorative (e.g., transforming) or exploitative (e.g., sustaining) nature (Christensen, 1997[21]). Certainty concentrates around these roles, which can be also viewed through Schumpeter’s Mark I and Mark II patterns of innovation (Breschi, Malerba and Orsenigo, 2000[47]). Mark I innovation is characterised by “creative destruction” based on challenging incumbents and disrupting current modes of production, organisation, and distribution. Mark I connects to exploration: i.e., things emerging on the horizon rather than making the current system more effective or more efficient. Mark II innovation is described as “creative accumulation” characterised by widening and deepening of innovations, models and approaches already adopted, and is often associated with larger organisations. Mark II can be seen as an exploitative activity: i.e., building on established, more radical prior innovations.

In terms of short-term gains, exploitative innovation is a more certain activity while exploration requires a higher tolerance for risk. However, in the long-term, organisations need both to be sustainable. As such, governments and public sector organisations are not immune to socio-economic paradigms and business models that impact innovation practices (Dosi, Fagiolo and Roventini, 2010[48]; Perez, 2003[49]). Exploration and creative destruction happen regardless of public sector organisations’ engagement of it. Governments are challenged by change in various ways, requiring various types of innovation and have different innovation needs depending on the systems, for instance the welfare or labour regimes, they work in (Spasova et al., 2019[50]). Thus, there is a role in public sector innovation for both exploration (higher uncertainty) and exploitation (lower risk) activities. This is not to say that improving existing services and systems comes without risk. On the contrary, the biggest failures in government often relate to projects becoming too big to fail and unable to take technological and social development into account (Tõnurist and Hanson, 2020[2]).

Purpose of innovation

Having established the dimensions of directionality and certainty, one must link them to why the public sector innovates. The OECD’s starting point here is the public value theory (Moore, 1995[51]), connecting the dimensions to values the public sector might aspire to when undertaking innovation. Public value can be defined by both the value the public sector seeks to attain and the value added to the public sphere (Moore, 2013[52]; Benington and Moore, 2011[53]). The public value framework is complex4 because values can be influenced positively and negatively at the same time. In the interest of simplicity, it helps to concentrate on “prime” or “substantive” values of the public sector, which can be pursued for their own right, and leave aside those instrumental in achieving other values. According to Beck, Jorgensen and Bozeman (2007, p. 373[14]), “The central feature of a prime value is that it is a thing valued for itself, fully contained, whereas an instrumental value is valued for its ability to achieve other values (which may or may not themselves be prime values).” Similarly, substantive values differ from transitory values as they hold true even if day-to-day missions and goals shift (Rosenbloom, 2014[54]).

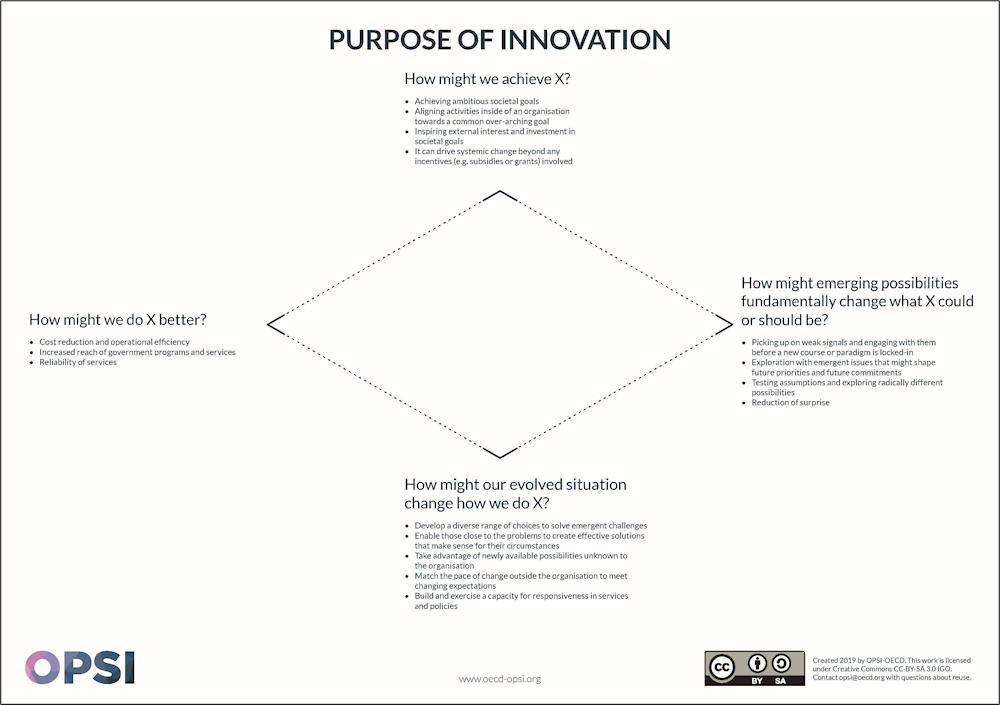

Various authors have proposed categories for prime values – e.g., ethical, democratic, professional and people (Kernaghan, 2003[55]) – and there is no consensus on the topic (Fukumoto and Bozeman, 2019[56]). Furthermore, prime values can be more moral-ethical, utilitarian, political-social, and so on. In the absence of consensus, this part of the model relies on empirical tests in countries to determine the types of prime values government organisations placed on directive/un-directive and certain/uncertain innovative activities (OECD, 2019[6]; 2021[8]; 2021[9]; 2020[10]). In workshops and validation sessions, the OECD asked public servants to describe the value their organisations and government were called to demonstrate and then classified these into broader categories. Through this approach four categories of questions emerged that connect to prime/substantive values of government (Figure 1.2), and can correspond to the innovation axes outlined in Figure 1.3 (below):

1. Political-social value: How can government achieve the ambitious societal goals that it is called upon to tackle?

2. Moral/ethical value: How can government continuously improve and do things better with the public funds entrusted to it?

3. Citizen-centric values: How can government account for and respond to evolving citizen needs and environmental changes?

4. Transformational values: How can government explore future risks and uncertainties, so that it and its citizens are future-ready?

Figure 1.2. Purpose of innovation in the public sector

Source: OECD.

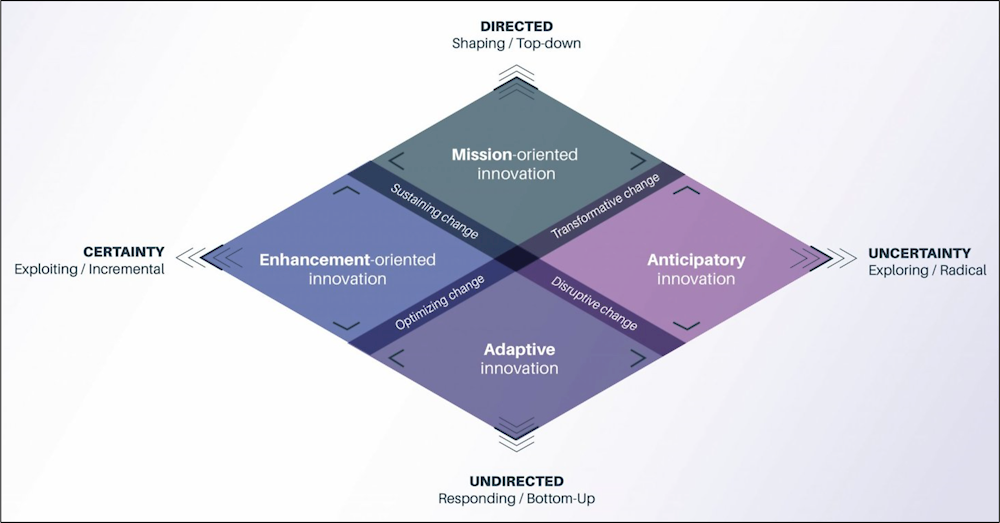

This empirical identification can connect substantive values to the purpose of innovation – that is to say, the core values and key issues that call the public sector to innovate – and demonstrate how the dimensions of directionality and certainty interact with these. The resulting Public Sector Innovation Facets model (Figure 1.3) shows that the more top-down an organisation’s directive process, the more it addresses the governments’ ability to achieve agreed societal values (mission-orientation). The less directive that process, the more adaptive government is to citizens evolving needs and environmental shifts (adaptation). Similarly, the more certain and exploitative the innovation, the more it corresponds to government’s value of being an effective and ethical manager of public goods (enhancement-orientation), and the more uncertain the process, the more government innovates for the purpose of transformative change that cannot be avoided and needs preparation (anticipatory innovation).

Figure 1.3. Public Sector Innovation Facets model

Source: OPSI.

Together, these approaches form the Public Sector Innovation Facets model, so called because there are no clear boundaries between the resulting perspectives, or “facets”. This means that all organisations should aim to support all facets of innovation in some way. The model should not be used to categorise activity but to explore its purpose and intent, as well as how innovation works in reality:

1. Enhancement-oriented innovation upgrades practices, achieves efficiencies and better results, and builds on existing structures without challenging the current system.

2. Adaptive innovation tests and tries new approaches to respond to a changing operating environment and citizen needs without a pre-determined direction.

3. Mission-oriented innovation sets a clear outcome and overarching objective for addressing a specific, time-bound and concrete challenge.

4. Anticipatory innovation explores and engages emergent issues that could shape future priorities and commitments and may be highly uncertain in nature.

The Public Sector Innovation Facets model describes the intent of different innovation activities in the public sector. Consequently, organisations should aim to support all four facets in some way as part of an innovation portfolio approach (Chapter 2).

References

[31] Bason, C. (2018), Leading Public Sector Innovation 2E: Co-creating for a Better Society, Bristol University Press.

[53] Benington, J. and M. Moore (2011), Public Value: Theory and Practice, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

[47] Breschi, S., F. Malerba and L. Orsenigo (2000), “Technological regimes and Schumpeterian patterns of innovation”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 110/463, pp. 388-410.

[36] Buchheim, L., A. Krieger and S. Arndt (2020), “Innovation types in public sector organizations: A systematic review of the literature”, Management Review Quarterly, Vol. 70/4, pp. 509-533.

[35] Chen, J., R. Walker and M. Sawhney (2020), “Public service innovation: A typology”, Public Management Review, Vol. 22/11, pp. 1674-1695.

[21] Christensen, C. (1997), The Innovator’s Dilemma, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

[38] Cinar, E., P. Trott and C. Simms (2021), “An international exploration of barriers and tactics in the public sector innovation process”, Public Management Review, Vol. 23/3, pp. 326-353.

[29] Cinar, E., T. Trott and C. Simms (2019), “A systematic review of barriers to public sector innovation process”, Public Management Review, Vol. 21/2, pp. 264-290, https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2018.1473477.

[28] De Vries, H., V. Bekkers and L. Tummers (2016), “Innovation in the public sector: A systematic review and future research agenda”, Public Administration, Vol. 94/1, pp. 146-166.

[34] Demircioglu, M. (2017), “Reinventing the wheel? Public sector innovation in the age of governance”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 77/5, pp. 800-805.

[43] Dooley, K. (1997), “A complex adaptive systems model of organization change”, Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology and Life Sciences, Vol. 1/1, pp. 69-97.

[48] Dosi, G., G. Fagiolo and A. Roventini (2010), “Schumpeter meeting Keynes: A policy-friendly model of endogenous growth and business cycles”, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, Vol. 34/9, pp. 1748-176.

[39] Edler, K. and W. Boon (2018), “The next generation of innovation policy: Directionality and the role of demand-oriented instruments - Introduction to the special section”, Science and Public Policy, Vol. 45/4, pp. 433-434.

[27] Fagerberg, J., M. Fosaas and K. Sapprasert (2012), “Innovation: Exploring the knowledge base”, Research Policy, Vol. 41/7, pp. 1132-1153, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.03.008.

[22] Freeman, C. and C. Perez (1988), “Structural crises of adjustment, business cycles and investment behaviour”, in Dosi, G. et al. (eds.), Technology, Organizations and Innovation: Theories, Concepts and Paradigms.

[56] Fukumoto, E. and B. Bozeman (2019), “Public values theory: What is missing?”, The American Review of Public Administration, Vol. 49/6, pp. 635-648.

[23] Geissdoerfer, M. et al. (2018), “Product, service, and business model innovation: A discussion”, Procedia Manufacturing, Vol. 21, pp. 165-172.

[25] Govindarajan, V. and J. Euchner (2012), “Reverse innovation”, Research-Technology Management, Vol. 55/6, pp. 13-17.

[40] Hekkert, M. et al. (2020), “Mission-oriented innovation systems”, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol. 34, pp. 76-79.

[24] Hossain, M. (2018), “Frugal innovation: A review and research agenda”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 182, pp. 926-936.

[14] Jørgensen, T. and B. Bozeman (2007), “Public values: An inventory”, Administration & Society, Vol. 39/3, pp. 354-381, https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399707300703.

[16] Kattel, R. et al. (2018), “Indicators for public sector innovations: Theoretical frameworks and practical applications”, Halduskultuur (Administrative Culture), Vol. 19/1, pp. 77-104.

[45] Kattel, R. and M. Mazzucato (2018), “Mission-oriented innovation policy and dynamic capabilities in the public sector”, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 27/5, pp. 787-801.

[7] Kaur, M. et al. (2022), “Innovative capacity of governments: A systemic framework”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 51, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/52389006-en.

[55] Kernaghan, K. (2003), “Integrating values into public service: Thevalues statement as centerpiece”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 63, pp. 711-719.

[42] Kirton, M. (1976), “Adaptors and innovators: A description and measure”, Journal of Applied Psychology, pp. 622–62.

[26] Klarin, A. (2019), “Mapping product and service innovation: A bibliometric analysis and a typology”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 149, p. 119776, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119776.

[30] Lewis, J., M. McGann and E. Blomkamp (2020), “When design meets power: Design thinking, public sector innovation and the politics of policymaking”, Policy & Politics, Vol. 48/1, pp. 111-130.

[37] Lewis, J., L. Ricard and E. Klijn (2018), “How innovation drivers, networking and leadership shape public sector innovation capacity”, International Review of Administrative Sciences, Vol. 84/2, pp. 288-307.

[44] Lindner, R. et al. (2016), “Addressing directionality: Orientation failure and the systems of innovation heuristic. Towards reflexive governance”, Fraunhofer ISI Discussion Papers, Innovation Systems and Policy Analysis.

[46] Mazzucato, M. and R. Kattel (2020), “Grand challenges, industrial policy, and public value”, in Oqubay, A. et al. (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Industrial Policy, Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198862420.013.12.

[18] McGann, M., E. Blomkamp and J. Lewis (2018), “The rise of public sector innovation labs: Experiments in design thinking for policy”, Policy Sciences, Vol. 51/3, pp. 249-267.

[52] Moore, M. (2013), Recognising Public Value, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[51] Moore, M. (1995), Creating Public Value: Strategic Management in Government, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[8] OECD (2021), Public Sector Innovation Scan of Denmark, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Public-Sector-Innovation-Scan-of-Denmark.pdf.

[9] OECD (2021), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Latvia: Country Scan, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Country-Scan-of-Latvia.pdf.

[4] OECD (2020), Embracing Innovation in Government Global Trends 2020, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, Paris, https://trends.oecd-opsi.org/.

[10] OECD (2020), Initial Scan of the Israeli Public Sector Innovation System, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Initial-Scan-of-the-Israeli-public-sector-innovation-system-FINAL.pdf.

[3] OECD (2019), Measuring Public Sector Innovation Why, When, How, For Whom and Where To?, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, OECD, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Measuring-Public-Sector-Innovation-Part-5b-of-Lifecycle.pdf.

[13] OECD (2019), Public Value in Public Service Transformation: Working with Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/47c17892-en.

[6] OECD (2019), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Brazil: An Exploration of its Past, Present and Future Journey, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a1b203de-en.

[19] OECD (2018), Evaluating Public Sector Innovation: Support or Hindrance to Innovation?, Observatory of Public Sector Innovation, Paris, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Evaluating-Public-Sector-Innovation-Part-5a-of-Lifecycle-Report.pdf.

[5] OECD (2018), The Innovation System of the Public Service of Canada, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307735-en.

[11] OECD (2017), Fostering Innovation in the Public Sector, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270879-en.

[1] OECD (2017), Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges: Working with Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279865-en.

[49] Perez, C. (2003), Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital, Edward Elgar Publishing.

[32] Pólvora, A. and S. Nascimento (2021), “Foresight and design fictions meet at a policy lab: An experimentation approach in public sector innovation”, Futures, Vol. 128, p. 102709.

[54] Rosenbloom, D. (2014), “Attending to mission-extrinsic public values in performance-oriented administrative management: A view from the United States”, in Bohne, E. et al. (eds.), Public Administration and the Modern State: Assessing Trends and Impact, Palgrave Macmillan.

[12] Schumpeter, J. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

[50] Spasova, S. et al. (2019), “Self-employment and social protection: Understanding variations between welfare regimes”, Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, Vol. 27/2, pp. 157-175, https://doi.org/10.1332/175982719X15538492348045.

[15] Tangen, S. (2005), “Demystifying productivity and performance”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Measurement, Vol. 54/1, pp. 34-46, https://doi.org/10.1108/17410400510571437.

[41] Thapa, R., T. Iakovleva and L. Foss (2019), “Responsible research and innovation: A systematic review of the literature and its applications to regional studies”, European Planning Studies, Vol. 27/12, pp. 2470-2490.

[20] Thøgersen, D., S. Waldorff and T. Steffensen (2021), “Public value through innovation: Danish public managers’ views on barriers and boosters”, International Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 44/14, pp. 1264-1273.

[2] Tõnurist, P. and A. Hanson (2020), “Anticipatory innovation governance: Shaping the future through proactive policy making”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 44, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cce14d80-en.

[17] Tõnurist, P., R. Kattel and V. Lember (2017), “Innovation labs in the public sector: What they are and what they do?”, Public Management Review, Vol. 19/10, pp. 1455-1479.

[33] van Buuren, A. et al. (2020), “Improving public policy and administration: Exploring the potential of design”, Policy & Politics, Vol. 48/1, pp. 3-19.

Notes

← 1. For more information, see https://oecd-opsi.org/case_type/opsi/.

← 2. For more information, see https://oecd-opsi.org/blog/innovation-is-a-many-splendoured-thing/.

← 3. For more information, see https://oecd-opsi.org/projects/innovation-facets/.

← 4. Beck Jørgensen and Bozeman (2007[14]) outline 72 values across several categories, including: public sector contribution to society; transformation of interests to decisions; relations between public administration and politicians; relations between public administration and its environment; intra‑organisational aspects of public administration; behaviour of public sector employees; and relationship between public administration and citizens.