Assessing the accuracy and completeness of taxpayer reported information is a core function of tax administrations and this chapter takes a closer look at tax administrations’ work in this area, including how they manage compliance.

Tax Administration 2023

6. Verification and compliance management

Abstract

Introduction

The audit, verification and investigation function assesses the accuracy and completeness of taxpayer reported information. This function employs on average thirty percent of tax administration staff to verify that tax obligations have been met. While this often happens through conducting desk or field based “tax audits”, there is an increased use of automated electronic checks, validations and matching of taxpayer information. The undertaking and visibility of these and other compliance actions is critical in supporting voluntary compliance, including through their impacts on perceptions of fairness in the tax system, as well as creating a ‘deterrent effect’. This chapter therefore looks at:

How tax administrations manage compliance risks, including the use of large and integrated data sets;

The delivery of compliance actions undertaken by tax administrations including moving field audit work into a virtual environment; and

The work on tax and crime.

Compliance risk management

The OECD report The Changing Tax Compliance Environment and the Role of Audit (OECD, 2017[1]) looked at the range of incremental changes occurring across tax administrations which, taken together, were changing the nature of the tax compliance environment, allowing for more targeted and managed compliance.

A significant part of this change is driven by the increased availability of data. As digital transformation continues, even more tax related data from taxpayers and third parties is becoming available (for example, data from e‑invoicing, online cash registers and financial account information), which is contributing to a clearer understanding of tax gaps. Most tax administrations now apply data sciences techniques and use analytical tools as part of compliance processes (see Table 6.1.), and this is explored in more detail later in this chapter. Box 6.1. also contains some examples of the range of data exploration techniques being used by tax administrations, including the analysis of unstructured data.

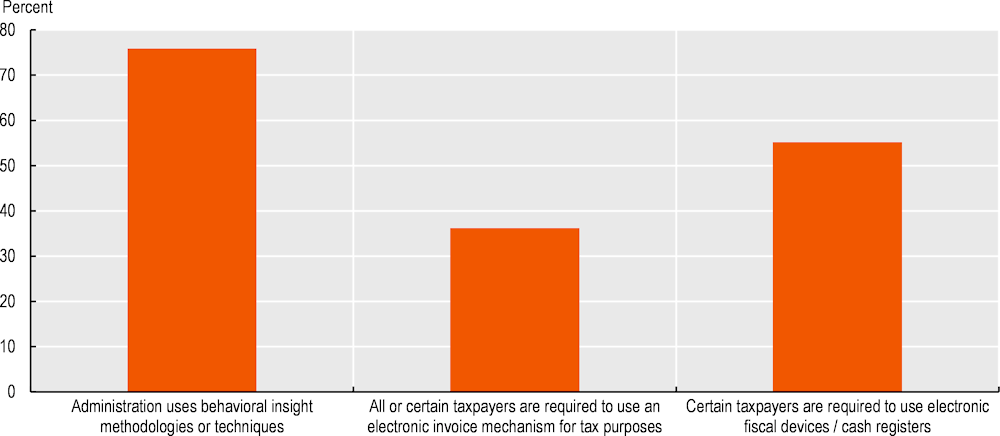

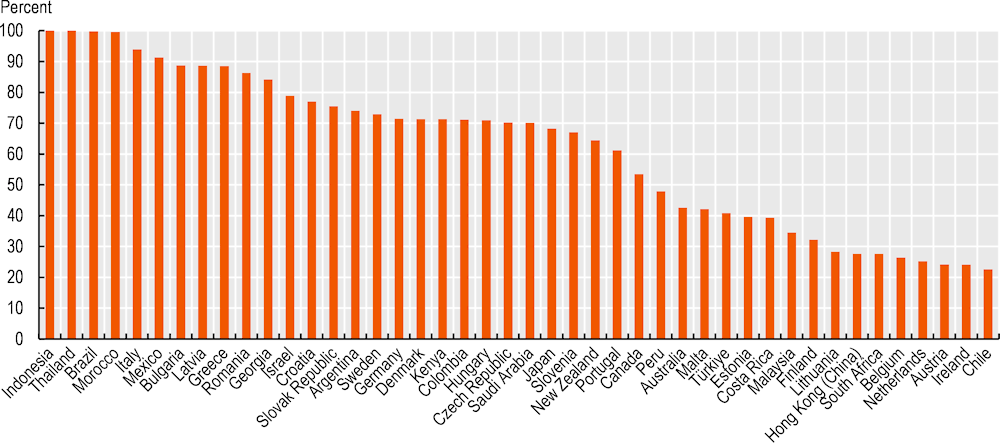

Another growing trend is the combination of analytics with behavioural analysis to build a more holistic understanding of compliance risks, behavioural patterns and appropriate compliance interventions. Figure 6.1., shows the percent of tax administrations who are using behavioural insights in their work. This percentage has grown from 62 percent of administrations in 2018 to 76 percent in 2021 (see also Table A.89.).

Figure 6.1. Use of techniques and methodologies to improve compliance, 2021

Box 6.1. Examples – Data exploration

Canada – Predictive models

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) continuously explores new and innovative ways to better target reporting non-compliance. Advanced analytics, including machine learning and deep learning, are being tested for identifying potential high-risk small and medium businesses for audit.

Graph database management systems and algorithms are used to automatically link all taxpayers by common ownerships and identify economic entities for population analysis, risk assessment, and workload selection.

Social network analysis is incorporated to identify influential legal entities in the organisational structures and discover different patterns and characteristics of economic entities to enhance risk assessment.

Ensemble anomaly detection (isolation forest, local outlier factor, mean shift clustering) and unsupervised learning (K-means, Gaussian mixture model, agglomerative clustering) methods are used to identify high-risk and anomalous segments in the small and medium enterprises population.

Advanced techniques are used to generate powerful predictors, including incorporating artificial intelligence auto-encoder techniques to compress high dimensional data and a short-term memory neural network to extract information from longitudinal (sequence) financial and economic entity data, as well as economic entities’ structure, which are used as predictors to enhance non-compliance prediction.

Advanced analytics, including deep learning and graph neural networks, are used to identify high-risk small and medium enterprises taxpayers and their associated economic entities.

These predictive models will supplement existing CRA tools that are used for workload development, and risk assessment, including incorporating factors arising from the impacts of the pandemic.

Sweden – Analysing unstructured data

In Sweden, private individuals and businesses can file their income tax returns digitally or using a paper form. Although the Swedish Tax Agency (STA) aims to promote digital tax returns, paper forms will still be needed for years to come. Every year, the STA receives about 150 000 paper forms containing handwritten free-text information. This service analyses and classifies free-text information in income tax return forms which improves the STA’s ability to process unstructured data for different types of analyses (risk evaluation, audits, etc.).

The service uses artificial intelligence in two ways. Firstly, to interpret and convert the handwritten text into digital text, and, secondly, to classify the text into one of about 60 subject categories. The text is interpreted using a deep-learning model that has been developed and trained by the STA. AI models are available on the market, but there are few models for the Swedish language, or with the capacity to interpret millions of unique handwriting samples.

The ability to interpret handwritten text can also be useful for a variety of other applications for the STA, as well as for other public authorities, municipalities, etc.

Key benefits of automated interpretation and classification of handwritten text:

The information reaches the right competence much faster than before

Increased ability to quantify and analyse the content of free-text information

Automation of specific cases

Sources: Canada (2023) and Sweden (2023).

Increasing availability of data

As more and more data is stored electronically, and the transfer, storage and integration of data has become easier through the application of new techniques and processes, there has been a huge increase in the amount of data available to tax administrations for compliance purposes. Frequently used data sources include:

Data from devices: Data can be collected from devices that register transactions such as online cash registers and trip computers for taxis and trucks, and also gate registrations from barriers and weigh bridges.

Data from banks, merchants or payment intermediaries and service providers: This allows direct verification of income or assets reported by the taxpayer. Some jurisdictions already receive transaction details or transaction totals for taxpayers on a regular basis.

Data from suppliers: Collecting data from suppliers, either directly or through the taxpayer, allows a more complete picture to be drawn about the activities and income of the taxpayer. This is seen in the increasing use of e-invoicing systems which, as noted in Chapter 4, allows some tax administrations to prefill tax returns.

Data from the customer: This is easiest in cases where the number of customers is limited and known, but increasingly mechanisms to leverage customers in compliance are being used, for example in the verification of cash receipts.

Unstructured data concerning the taxpayer: Increasingly electronic traces relevant to business activities and transactions can be found on the internet and in social media.

Data from other government agencies: Data held by other government agencies for example for licencing, regulatory or social security purposes can be relevant in verifying tax returns or in risk assessments.

Data from international partners: New international exchanges of data commencing under the Common Reporting Standard and Country-by-Country Reporting is massively increasing the quantity of data available on international activity and providing useful information for audit and case selection processes and in some cases for prefilling of tax returns.

Box 6.2. Examples – Increased availability of data to support innovation

Chile – Income Tax Dashboard

The large volume of available tax data constitutes a big challenge for tax administrations especially in the development of relevant indicators and monitoring mechanisms. The monitoring of relevant indicators and their evolution is important as it allows a better use of the available resources, that can be focussed on the compliance control actions with the most revenue-relevant risk.

The Servicio de Impuestos Internos (SII) has developed interactive reports enabling the analysis of taxpayer behaviour using SII held information, inconsistencies detected on tax returns and third party sworn statements received during the income tax filing process. These reports allow tax officials to monitor and understand multiple issues from different perspectives, for example, most frequent inconsistencies, the amounts involved, geographical location, taxpayer classification and their evolution in the last three fiscal years.

The visualisation of income tax returns and the identified inconsistencies allows the design of corrective actions to be taken according to the level of non-compliance. These actions can include preventive measures for ensuring an accurate tax filing process in the future.

The platform adopted to implement this interactive reporting tool ensures an institutional-wide availability, where information can be shared amongst officials and accessed by multiple users simultaneously, reinforcing the decision-making process.

See Annex 6.A for supporting information.

Finland – The ‘Incomes Register’

The ‘Incomes Register’ is a centralised national database for income information at an individual level. It contains comprehensive data on earned income, pensions and benefits, and implements the principle of one-time reporting.

After each payment, the ‘Incomes Register’ receives information about wages paid from employers, pensions, benefit payers, etc. The information reported to the ‘Incomes Register’ is then available in real time both when the wage earner applies for a new tax card and when the National Pension Institute and other operators grant benefits and pensions. The data creates the basis for the processing of insurance claims, and it is also used in occupational health and safety, statistics and the determination of various customer fees.

For those reporting the information, this means that they only need to report once, and they can be sure the data has gone to all relevant parties. For data users, this means that they have access to more accurate information in real-time.

In 2021, some 50 million earnings-payment reports containing payroll amounts, 2 million employer declarations and 65 million benefit information declarations were reported to the ‘Incomes Register’. A total of 250 000 different payers reported salary information. Benefits were reported by nearly 400 different payers. Income information was shared more than 800 million times with the 380 information users entitled to access the information. Payroll information is stored in the ‘Incomes Register’ from 2019 and pension and benefit information from 2021. Payroll and benefit information for a total of 4.7 million people has been reported to the ‘Incomes Register’.

See Annex 6.A for supporting information.

Poland – The National e-Invoice System

From 1 January 2022, Polish entrepreneurs can use the National e-Invoice System (KSeF). KSeF is a widely available invoice exchange platform that allows taxpayers to issue, send, receive and store electronic documents (e-invoices) in a structured form. Currently, the use of an e-invoice is optional with mandatory electronic invoicing being introduced in Poland from 1 January 2024.

KSeF will increase the speed of data exchange in contacts between contractors and mutual settlements. Accounting for invoices will become much easier, with the invoice made available to the recipient practically in real time, which allows for automation of accounting processes. At the same time, it will allow taxpayers to reduce errors with manual data entry and save time. This will reduce the business costs associated with handling the invoicing process. KSeF will also strengthen the analytical processes of the tax administration in the fight against tax fraud.

Sweden – Property taxes

The Swedish Tax Agency (STA) is continuously working to improve and simplify the methods for calculating assessment values. Evaluations of previous agricultural property assessments indicate that timber stocks have been one of the valuation factors that have deviated furthest from reality.

To address this, data is now derived from maps that provide a variety of information, including timber stocks. The maps are produced by combining data from the Swedish Mapping, Cadastral and Land Registration Authority (“Lantmäteriet”) and field data from the Swedish National Forest Inventory (“Riksskogstaxeringen”).

This new method will help to ensure more fair and equal assessment of forest properties, while improving the quality of the STA’s registers. The analysis is carried out on an ongoing basis, as it takes about seven years to scan all of Sweden’s forests. The STA believes this new method will help to ensure a better service to property owners through higher data quality.

In the process of developing the method, the STA has identified further areas where the use external data could help make the assessment process both more effective and simpler for property owners. One such example is the land types associated with a property.

Sources: Chile (2023), Finland (2023), Poland (2023) and Sweden (2023).

There are, though, some emerging risks to the availability of large data sets. In particular, it is increasingly possible for data relevant to the tax administration in one jurisdiction to be held within the territory of another jurisdiction. In these circumstances, it can be difficult to obtain the data on an automatic basis from the data holder located in another jurisdiction. This could make it more difficult to risk assess in some circumstances, as well as making it more difficult to prefill tax returns and to further develop compliance-by-design processes.

An example of this comes from the growth of the sharing and gig economy facilitated through online platforms which can operate across border. This may become an increasing risk as the online economy grows, particularly if it is accompanied by a shift from salaried employment (and the reporting of incomes by employers) to self-employment. This issue was considered in the OECD report The Sharing and Gig Economy: Effective Taxation of Platform Sellers (OECD, 2019[2]). That report looked at a number of strategies currently being adopted by tax administrations as well as their limitations and recommended the development of standardised reporting requirements to facilitate possible future automatic exchange of information between tax administrations. It also led to the development of:

A set of Model Rules that when used in legislation require digital platforms to collect information on the income realised by those offering accommodation, transport and personal services through platforms and to report the information to tax authorities (OECD, 2020[3]).

A Code of Conduct to facilitate a possible standard approach to co-operation between administrations and platforms on providing information and support to platform sellers on their tax obligations while minimising compliance burdens (OECD, 2020[4]).

A report that explored the practical issues raised by real-time connections between tax administrations and sharing and gig economy platforms (OECD, 2022[5]).

Another risk that has been identified is that posed by digital financial assets (DFAs), such as cryptocurrencies. The owners of DFAs can be very difficult to trace even though they may be linked to the creation of a specific digital wallet (which is somewhat similar to a bank account). Tracking down the individuals or entities behind particular wallet addresses is at best very difficult and resource intensive. In August 2022, the OECD approved the Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework which provides for the reporting of tax information on transactions in Crypto-Assets in a standardised manner, with a view to automatically exchanging such information. (OECD, 2022[6])

While not a risk as such, it should also be noted that data protection requirements could limit the circumstances in which data can be kept, processed or shared. This is a key consideration for administrations in designing systems which rely on large data sets and the retention of data.

Sharpened targeting of risks

Data science

Over recent years, the application of advanced analytics to risk management and risk targeting is becoming increasingly common:

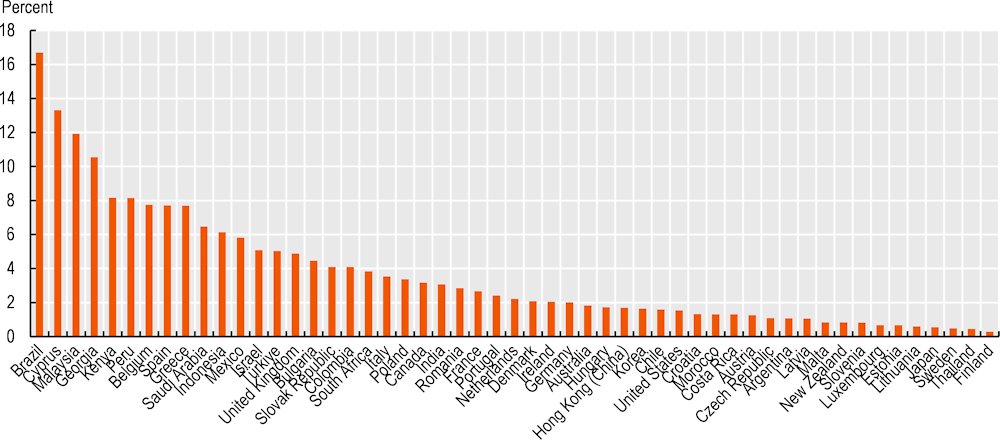

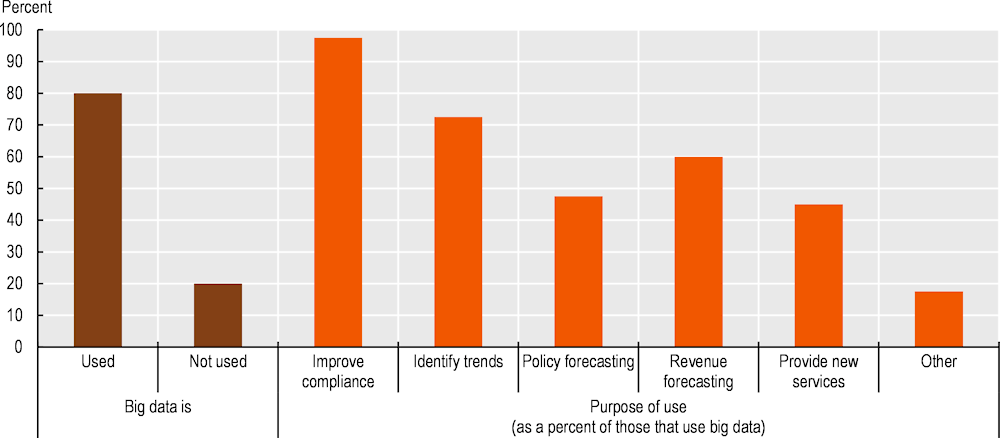

Figure 6.3. shows 80% of tax administrations reporting using big data in their work, and of those that use big data nearly all are using it to improve their compliance work.

Of the 58 tax administrations covered by this report, 55 report using data science / analytical tools with the remaining administrations in the process of preparing the use of such tools going forward (see Table 6.1.).

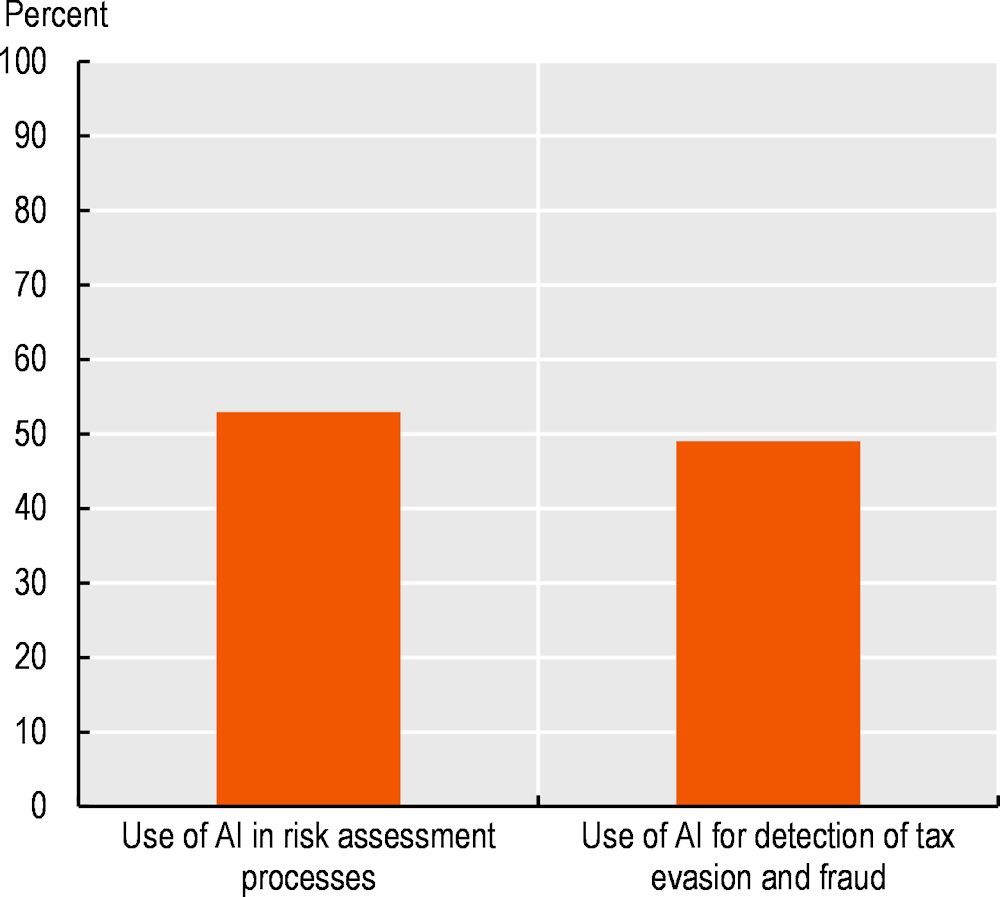

Similarly, the use of artificial intelligence, including machine learning, for risk assessments and detecting fraud is already undertaken or in the process of being implemented by the majority of administrations covered in this publication (see Table 6.1. and Figure 6.4.).

This increasingly sophisticated use of analytics on expanded data sets is leading to a sharpening of risk management and the development of a range of intervention actions, including through automated processes. A selection of examples is included in Box 6.3. Additionally, the OECD report Advanced Analytics for Tax Administration: Putting data to work (OECD, 2016[7]) provides practical guidance on how tax administrations can use analytics to support compliance and service delivery.

Table 6.1. Evolution of the application of data science tools, artificial intelligence and robotic process automation between 2018 and 2021

Percent of administrations

|

Status of implementation and use |

Data science / analytical tools |

Artificial intelligence, including machine learning |

Robotic process automation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

2021 |

Difference in percentage points (p.p.) |

2018 |

2021 |

Difference in p.p. |

2018 |

2021 |

Difference in p.p. |

|

|

Technology implemented and used |

71.9 |

94.8 |

+22.9 |

31.6 |

54.4 |

+22.8 |

22.8 |

50.0 |

+27.2 |

|

Technology in the implementation phase for future use |

19.3 |

5.2 |

-14.1 |

15.8 |

28.1 |

+12.3 |

14.0 |

8.6 |

-5.4 |

|

Technology not used, incl. situations where implementation has not started |

8.8 |

0.0 |

-8.8 |

52.6 |

17.5 |

-35.1 |

63.2 |

41.4 |

-21.8 |

Sources: Tables A.91. and A.92.

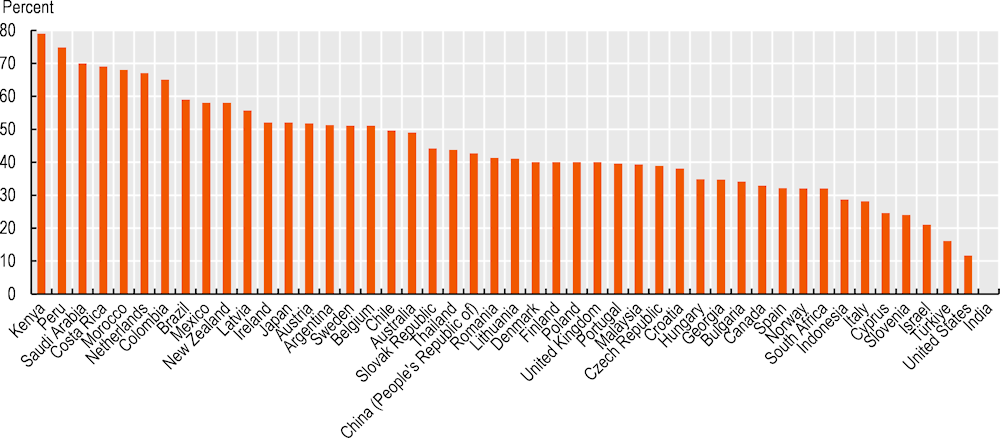

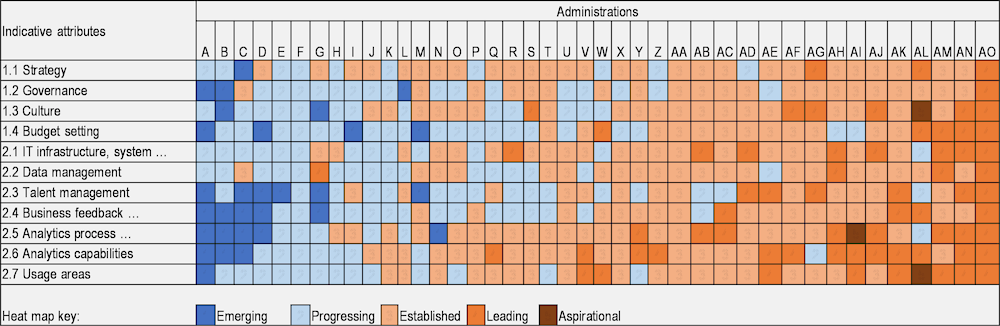

With the use of analytics increasingly becoming a common and integrated part of tax administrations across the world, in developed and developing countries alike, being used in strategic as well as operative usage areas, the OECD’s Forum on Tax Administration developed the Analytics Maturity Model (OECD, 2022[8]). The model allows tax administrations to self-assess their current level of maturity in their analytics usage and capability, providing insight into current status and identifying areas of weaknesses as well as strengths. As Figure 6.2. shows, it has been completed by over 40 tax administrations, and the results of this are guiding and supporting administrations in their analytics strategies.

Figure 6.2. Results of the Analytics Maturity Model self-assessments

Source: OECD (2022), Analytics Maturity Model, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/analytics-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

Figure 6.3. Use of big data for analytical purposes, 2022

Note: The figure is based on ITTI data from 52 jurisdictions that are covered in this report and that have completed the global survey on digitalisation.

Source: OECD et al. (2023), Inventory of Tax Technology Initiatives, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/tax-technology-tools-and-digital-solutions/, Table DM3 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

Figure 6.4. Use of artificial intelligence, 2022

Note: The figure is based on ITTI data from 52 jurisdictions that are covered in this report and that have completed the global survey on digitalisation.

Source: OECD et al. (2023), Inventory of Tax Technology Initiatives, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/tax-technology-tools-and-digital-solutions/, Table TRM3 (accessed on 22 May 2023).

Box 6.3. Examples – Using analytics

Australia – Application of data science and analytical modelling

The COVID-19 pandemic created challenging economic conditions that affected many businesses and communities in Australia. Between 2019 and 2022, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) experienced a 16% growth in debt accounts and a substantial 70% increase in collectable debt. After pausing many actions during the pandemic, in 2022 the ATO resumed collection activities.

Analytic modelling and data driven insights are integral to delivering on ATO’s differentiated strategies and treatments. In 2022, the ATO:

Made improvements to their Financial Resilience Insights (FRI) suite of analytic models to better cluster similar clients and recognise their assets and income streams.

Deployed Enterprise Client Profile (ECP) gadgets which surface these FRI analytic insights to staff, enabling them to understand the financial health of taxpayers. Financially healthy taxpayers who have a greater capacity to reduce their debt are encouraged to pay in full or enter in to optimal (shorter) payment plans, while taxpayers who are less financially healthy can be supported with longer repayment terms which analytics indicates are more sustainable.

Re-configured the analytic model combination which supports delivery of taxpayers to staff for potential firmer actions, pivoting away from some models which had deteriorated in performance (accuracy of predictions) due to limited training data due to the pause on firmer actions.

Assessed the collection prospects for several populations of special interest, such as Superannuation Guarantee debtors, Small Business debtor and fraudulent credit claims.

Chile – Fraud risk: Taxpayers with tax records or documents to prove

A "taxpayer with aggressive tax behaviour" is defined as any taxpayer who, after having notified the start of trading to the SII and subsequently being authorised to issue VAT documents, goes on to raise doubts as to whether the linked business operations have actually been carried out. To address this, the SII set-up an initiative to identify, based on a predictive model, those taxpayers who might engage in such activity, and to design preventive, corrective or structural treatment actions.

These types of models are used as part of the SII strategy against non-compliant behaviour within the first 3 months of taxpayer registration, and different types of algorithms are used to detect anomalies. The data used is extracted from tax returns, purchase and sales tax documents, and relationships with other relevant actors associated with the taxpayer’s commercial operations.

Israel – Analytics Centre

The Analytics Centre is a platform for maximising the yield per hour of any tax administration process by providing diverse supporting analytics products. It consists of two innovative core components:

An analytics workshop for rapid production of a variety of analytics models such as AI models, graph analytics models, rule-based engines, statistical report generators, etc.; and

A model cloud for scalable implementation of these models.

Once a model is manufactured in the workshop and registered in the cloud, it is ready to simultaneously serve multiple users through dedicated applications regardless of the model's initiator. This holistic platform drives the continuous growth of analytics usage up to an enterprise-wide level which increases organisational overall productivity. This system has for example produced models for the selection of cases for company, individual or VAT tax audit.

At the beginning of 2022, the company selection model provided a list of 131 companies recommended for audit. By the end of the year, the tax audit process of 43 companies has been completed. This overt process yielded in average an increase in the tax generated from each company.

An AI model for detecting real-estate property owners who do not report rental income was also developed. The model provided a set of 425 suspects with a 50% accuracy rate as 227 suspects responded in less than two months and generated additional annual tax.

Sweden – Improving identification and matching

The STA has developed a service that identifies private individuals and businesses in the Swedish tax registry and matches them to incomplete data received through automatic exchange of information initiatives. The service aims to:

Increase the ability to identify potential matches;

Increase the level of certainty that a match is correct; and

Improve the ability to manage changes in data, technological developments, so that data quality is maintained over time.

To achieve this the STA built a tool based on search engine technology which allows:

Increased search efficiency through indexing of source data, with the ability to index individual words or variants of words;

The use of complex queries without time-consuming manual index creation; and

Advanced scoring for ranking search results.

This approach has been very effective with the percentage of identifications increased from 75% to 90%, while the accuracy of identifications increased from 95.2% to 99.9%.

Sources: Australia (2023), Chile (2023), Israel (2023) and Sweden (2023).

Taxpayer programmes

Another approach for targeted risk management is the creation of units looking into the tax affairs of specific taxpayer segments. Two specific areas where tax administrations have found it advantageous to manage specific groups of taxpayers on a segmented basis are business taxpayers, and high net wealth individuals (HNWIs). The rationale for focusing administration resources on managing these groups revolves around the:

Significance of tax compliance risks: due to the nature and type of transactions, offshore activities, opportunity and strategies to minimise tax liabilities; and in the case of large business, the differences between financial accounting profits and the profits computed for tax purposes.

Complexity of business and tax dealings: particularly the breadth of their business interests and in the case of HNWI, the mix of private and tax affairs.

Integrity of the tax system: the importance of being able to assure stakeholders about the work undertaken with these high-profile groups of taxpayers.

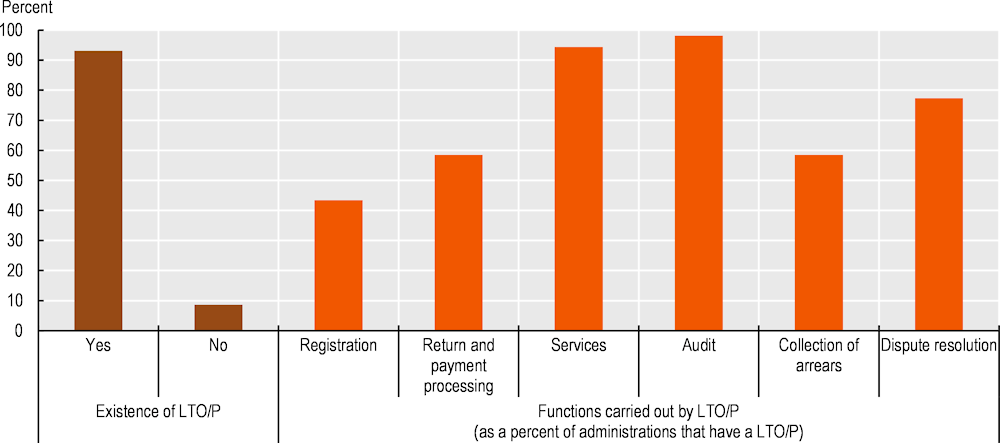

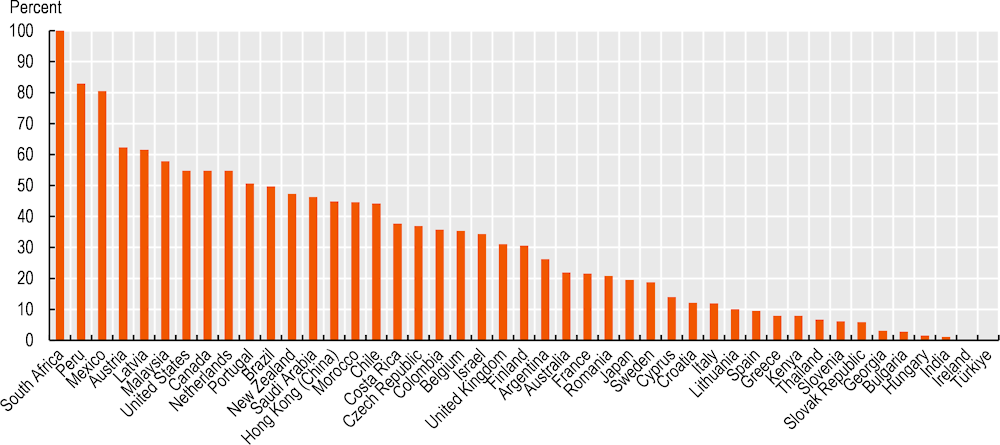

Additionally, in the case of large taxpayers, while being a small number of taxpayers they are typically responsible for a disproportionate share of tax revenue collected. The data indicates that for most jurisdictions between 30% and 60% of their total net revenue, including withholding payments on behalf of employees, was received from taxpayers covered by their large taxpayer programmes (see Figure 6.5.). On average, 2.4% of corporate taxpayers covered by those programmes account for 44% of all revenue collected (see Table 6.2.).

Table 6.2. Importance of large taxpayer offices / programmes (LTO/P), 2021

|

FTEs in LTO/P as percentage of total FTEs |

Corporate taxpayers managed through LTO/P as percentage of active corporate taxpayers |

Percentage of net revenue administered under LTO/P in relation to total net revenue collected by the tax administration |

FTEs on audit, investigation and other verification function in the LTO/P as percentage of total FTEs in LTO/P |

Total value of additional assessments raised through LTO/P as percentage of total value of additional assessments raised from audits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4.0 |

2.4 |

43.6 |

62.8 |

31.3 |

Note: The table shows the average percentages across the jurisdictions that were able to provide the information.

Sources: Tables D.16. and D.17.

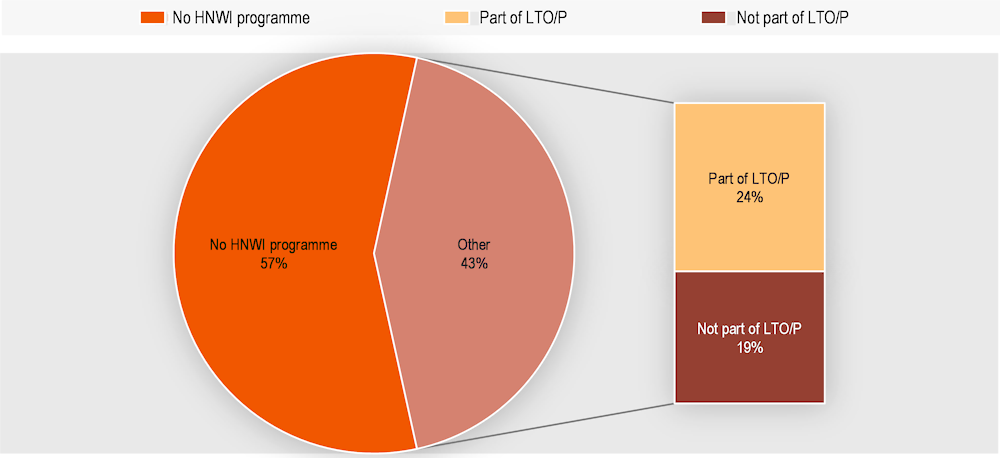

While the management of these groups of taxpayers is often undertaken as a programme, in a large number of jurisdictions these programmes are also structural involving a Large Taxpayer Office or HNWI unit. The scope of the work of these units varies considerably, ranging from undertaking traditional audit activity, through to “full service” approaches (see Figure 6.6.). However, on average close to two-thirds of tax administration staff in large taxpayer offices or programmes are working on audit, investigation and other verification related issues (see Table 6.2.).

Box 6.4. Examples – Supporting business taxpayers

China (People’s Republic of) – Integrated information system for large business

Previously, provincial and municipal offices of the State Taxation Administration (STA) of the People’s Republic of China only had access to the information on business within their jurisdiction, meaning they did not have the whole picture of a business operating across multiple provinces or municipalities. Now the STA is building an integrated information system for large business, to monitor taxable income sources, better control risks, provide more tailored services, and improve economic analysis.

This means tax offices at central, provincial and municipal levels can have appropriate access to information on a business and the information is grouped into 11 categories, including tax payments, social security payments, financial statements and so on. With just a few clicks, the system can automatically generate 7 themed reports including an overview, geographic distribution, tax and fee payment, business activities, compliance record, tax source status and customised enquiries. Using a different combination of data sets and administration logic, the STA can also design 24 scenarios for a business, covering the major risk possibilities. The system can also use a special set of risk indicators to identify a group of large businesses for further scrutiny.

The system offers a powerful tool for economic analysis. With data and information at different levels of granularity available, analysts can look at economic pictures of different areas, sectors and industries, supporting policy design and adjustment.

Georgia – Administration of large taxpayers

Large taxpayers make a significant contribution to the Georgia state budget, but the tax risks associated with them are much larger and more complex than the tax risks of other categories of taxpayers, which means they can pose a risk to tax revenues. Therefore, their activities require close monitoring.

To address this, the Office of Large Taxpayers was established in the Georgia Revenue Service, which, by offering highly qualified services and timely response to tax risks, ensures the maximum promotion of voluntary tax compliance of the taxpayers.

To improve the administration of large taxpayers, the updated Strategy for the Administration of Large Taxpayers for 2022-2024 was developed. This is supported by a standard reporting system through which various types of information are monitored on a daily basis. The strategy aims to improve the tax administration of large taxpayers through centralised, fair and transparent approaches. To achieve this goal, the following tasks were planned:

Develop services tailored to the needs of large taxpayers;

Strengthen risk management process related to tax compliance; and

Improve human resource capabilities.

Sources: China (People’s Republic of) (2023) and Georgia (2023).

Figure 6.5. Percentage of revenue administered through large taxpayer offices/programmes, 2021

Figure 6.6. Large taxpayer offices / programmes: Existence and functions carried out, 2021

Figure 6.7. HNWI programmes, 2021

Planning for future risks

While it is key for tax administrations to understand current compliance risks and prepare appropriate response strategies, it is equally important to understand and prevent risks which may arise in the future. The increasing availability of data along with the enhanced capacity of tax administrations to handle and analyse that data allows tax administrations to more robustly assess future tax risks. Figure 6.3. highlights the large number of tax administrations who engage in forecasting, which is putting them in a position to assess where new compliance risks may arise and develop in time the necessary mitigation strategies as the ability to identify, understand and manage risks in a rapidly changing environment is a critical element of successful and resilient tax administration.

This is leading to the creation of sophisticated risk management programmes, that can embed risk management across the organisation rather than leaving it in silos across the organisation. It also helps building a risk culture within tax administrations, as Box 6.5. illustrates.

Box 6.5. Examples – Emerging risks

Brazil – Integrated risk management programme

Historically, the Brazilian Revenue Authority (Receita Federal do Brasil – RFB) managed institutional risks based on its organisational structure and operational framework, while tax compliance risks were handled in a fragmented manner by various business units according to their own criteria and understanding of the risks.

Since 2021, and with the technical support of international organisations, a strategic programme was established to restructure the organisation's risk management model supported by a multi-faceted, integrated approach. Programme milestones included a new risk management policy, the design of a National Risk Management Office with regional focal points and revised roles, responsibilities, delegations of authority and governance structures.

The new model is to be applied across all business areas and levels of the organisation and intends to provide better coordination of RFB's risk treatment initiatives, which are identified using an integrated risk assessment system using advanced technology tools. Outcomes generated by the framework are fully integrated into real-time business performance reporting.

Advanced data analytics is leveraged to collect, convert, and process large volumes of data in RFB’s databases into clear and readily understandable risk management information to inform proactive decision-making. The goal is to make this information increasingly available in real time and to staff across the organisation. Ultimately, RFB’s goal is to have its risk management model embedded into core administration values and reflected in day-to-day behaviours and its organisational culture.

New Zealand – Enterprise risk

New Zealand Inland Revenue (IR) has simplified the language and approach used to manage risks across the organisation, starting with a consolidation of controls for the strategic risks, and ensuring clear ownership – this is aligned to functional accountabilities.

The controls used to manage strategic risks were simplified to align to the functional accountabilities and organisational structure, so there are clear lines of responsibility and action. Assurance of the effectiveness and completion of remediation actions are then linked to existing work programmes and tracked. Additional layers of definition can be added by the control owners to define the controls, or to define specific elements that are effective or being improved. When remediation is underway this often links to initiatives that are approved as part of the enterprise portfolio.

Reporting on risks and controls is managed through a centralised toolset, so there is one source of truth about the effectiveness of a control or the level of risk. The actions and owner of the work are visible and managed through the same toolset, with links to portfolio management, project management and enterprise planning activities. IR’s business groups can add their own risks and controls to the toolset and link them to the strategic risks and controls. This is starting to provide a more comprehensive view of the risks being managed by the organisation, and the operational activities this impacts.

The change in approach to a centralised and transparent control framework has allowed IR to start managing the strategic risks in a co-ordinated way that links to operational activities and control improvements.

Sources: Brazil (2023) and New Zealand (2023).

Planning for future risks is particularly important as jurisdictions consider the ongoing impacts of global challenges and how they influence taxpayer’s compliance behaviour. This is likely to be challenging as jurisdictions emerge from the pandemic when most administrations reduced or suspended compliance activities, impacting the data available to accurately assess risk. The sophisticated modelling analytics and modelling skills that tax administrations built up before the pandemic have been used to respond to these challenges, and to take account of any changes in taxpayer behaviour.

An interesting development within tax administrations is the recognition that the power of data analysis needs to be decentralised and spread more widely across the organisation. Through this, tax administrations can be ready to identify emerging risks more quickly and identify possible early interventions. As a result, tax administrations are now also exploring how artificial intelligence can be incorporated into compliance processes across the organisation, and it is likely that this will be central to the digital transformation of compliance management, and risk management in the future. Examples of this can be seen in Box 6.6.

Box 6.6. Examples – Use of artificial intelligence

Ireland – Artificial intelligence proof of concepts

To simplify the customer experience and to remove the need for the taxpayer to self-categorise their enquiry, artificial intelligence (AI) was used to automate the process of categorising and routing of enquiries to the appropriate subject matter experts for action.

To deliver this, proof of concept pilots were developed and deployed to determine the best fit for various scenarios. Business and ICT teams worked collaboratively to identify a range of taxpayer enquiries and used these to train the technology models to automate the task. Through a suite of iterative reviews of the data, a model was established using the best-fit technology. As a result, radical simplification of the online user interface was implemented to remove complicated drop-down menus. The original AI technology and models are now being copied and finessed to incorporate other taxpayer cohorts and query types.

Through this work, there was an uplift from 70% accuracy levels of self-categorisation by taxpayers to 97% accuracy in top-level categorisation of enquiries. On average, auto classification has reduced overall routing time to subject matter experts by over 24 hours. The simplified taxpayer user interface means that a taxpayer can now submit an enquiry in ‘free text’ format without having to consider tax categories and sub-categories. This has encouraged taxpayers to use digital first channels when contacting Revenue by making the submission of an enquiry much simpler, and the more accurate classification of enquiries gives more business insight into customer requirements allowing more targeted responses.

Israel – Automated logical assessment project

In Israel, the tax authority is using advanced digital tools to promote and streamline their work. For example, an automated real estate tax assessment project combines AI components that simulate the work of the tax inspector who conducts the real estate tax assessment with the computing capabilities of online systems. This reduces the duration of assessment and allows officials to focus on the more complex cases with the potential for high tax return.

The project was driven by a change which made the filing of the sale and purchase of real estate online instead of manual reporting. The automated real estate tax assessment project started gradually in 2022 while examining the programming at each stage and improving the logical mechanism as needed. During 2022, computerised logical assessments were used in 30 500 real estate transactions (approximately 34% of all similar transactions).

The standard time for an assessment, by a tax inspector, in a real estate transaction is one hour. Consequently, in 2022, the automatic system saved 30 500 working hours. In addition, 30 500 sellers and buyers completed the interaction with the tax authority immediately upon submitting the online statement by themselves or through a representative. The parties to the transaction also immediately received tax approvals and relevant necessary documents.

The automatic assessments carried out in 2022 handled transactions exempt from capital gains tax. Transactions that have been logically checked and found to be defective are forwarded to the tax inspector, including an explanation of the deficiency. In 2022, the average tax return per hour of work in the department handling property tax exemption assessments increased by 48% compared to 2021.

Singapore – The ‘One Payout Platform’

In 2022, the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) developed the One Payout Platform, a smart analysis solution, to enhance its capability in detecting attempts to game the system and also in identifying risky payouts. This platform aims to provide a “one-stop” solution to streamline payout risk assessments and assist IRAS officers in identifying potential abusers of various payout schemes.

Incorporated with data analytics and machine learning capabilities, the platform has the following key components:

A variety of data and anti-gaming models are consolidated and integrated into the platform to assist fast and effective analysis. Officers can directly interact with the models for timely case selection and where required, tweak the model parameters to perform risk simulation in real-time.

The rule-based risk scoring engine applies business logic for risk assessment, while the predictive models (machine learning) assess the risk severity for the new cases. With the combination of the 2 risk scoring engines, more efficient and robust risk assessment can be achieved for better case prioritisation.

Intuitive user interfaces allow officers to self-help, perform the analysis and select cases easily. The compilation of relevant information and visual representations into a one-stop portal allows officers to review details of the case at one glance and make fast decisions during case audits.

Through this, the One Payout Platform enables fast and effective detection of potential fraud in new payout schemes, resulting in productivity savings and allowing a much shorter turnaround time to onboard new schemes.

Sweden – Risk evaluation

By using AI to distinguish high-risk and low-risk cases, the STA was able to identify and disallow incorrect tax deduction claims amounting to SEK 300 million (representing SEK 42 million in taxes). By combining AI with other techniques, it was possible to achieve this without significant additional resources.

The STA introduced an automated system, and an AI model is used to recognise patterns in order to identify deduction claims where there is a high likelihood that the individual will not respond to a request for proof to substantiate the claim.

The AI model is trained on data from previously conducted investigations, enabling it to detect characteristics common to those who do not respond to requests for substantiation. A typical example is the presence of conflicting information, such as when an individual claims a deduction for travel expenses to work but lacks income from employment.

The STA’s automated system generated 19 000 requests for substantiation that would not otherwise have been issued. The system sends automated requests based on the results generated by the AI model. Failure to respond results in an automatic refusal of the claimed deduction. If the STA receives a reply, the case is processed manually in the usual way.

Sources: Ireland (2023), Israel (2023), Singapore (2023) and Sweden (2023).

Delivery of compliance actions

“Compliance actions” undertaken by tax administrations to determine whether taxpayers have properly reported their tax liability are changing. As set out earlier, the increasing availability of data and the introduction of sophisticated analytical models are allowing administrations to better identify returns and claims or transactions which might require further review or be fraudulent. Furthermore, these models, many of which can operate in real-time, are allowing administrations to conduct automated electronic checks on all returns or on transactions of a particular type.

Electronic compliance checks

While traditional audits (including comprehensive, issue or desk audits) are often the primary verification activities, the use of automated electronic checks or using rules-based approaches to treat some defined risks (for example, automatically denying a claim, issuing a letter or matching a transaction) is providing administrations with more effective and efficient ways to undertake some of this work. Box 6.6. sets out examples of this.

These approaches do, however, raise the question of how to reflect those automated electronic checks in the performance information that administrations report in ISORA data. To include all checking may distort coverage, adjustment and yield rates. However, where it replaces previously undertaken manual actions it would seem appropriate to reflect what administrations are now doing in this area.

In this respect, administrations completing the ISORA survey were invited to break down the total value of additional assessments raised from audit and verification actions into (i) audits and (ii) electronic compliance checks (defined as electronic checks, validation and matching of taxpayer information). Only a few administrations were able to provide information on electronic compliance checks. However, for some of those administrations, electronic compliance checks make-up an important part of the additional assessments raised through all audits and verification actions. (See Table D.39.)

Thanks to the growth in data and more powerful technology resources there is an increasing trend being the development of ‘real-time’ compliance checks, helping catch errors earlier in the process as Box 6.7. illustrates.

Box 6.7. Examples – Electronic compliance checks

India – eVerification checks

The eVerification Scheme launched by the Income-Tax Department in India, gives taxpayers all the electronic financial information pertaining to them, collected from various sources by the tax administration. Taxpayers can then verify the information for the purpose of accurate and comprehensive determination of the income of a taxpayer.

Three outcomes are possible. Firstly, they may accept the information and include it in their filing. Alternatively, if they may not accept the information as correct and consider there to be a mismatch, then the information is re-verified. Finally, if there is no response from the taxpayer, the reported data is classified as income.

In case of a mismatch, there is electronic communication with the sources of information, such as banks and offices which deal with immovable property transactions, etc. These third-party sources may correct the information or revalidate the existing information as correct. In case the mismatch still persists, a risk assessment of such cases is undertaken. If the data is of no or low risk, the case is closed. However, in case the risk is considered to be high, preliminary verification is undertaken by the tax authorities and the preliminary verification report is matched with the return of income to prepare the final verification report.

If as part of the production of the final verification report it is assessed that the risk involved is low or there is no risk involved, the case is closed. However, in case of high risk, the information is either passed to the tax audit team (in case there is already an ongoing audit) or appropriate action will be taken by the tax department.

Ireland – Real-Time Risk Dashboard

Revenue previously used a rules-based engine to run a risk analysis against PAYE customers when a refund request was triggered. This risk analysis was a nightly batch process which ran a set of predefined rules against PAYE customer data to determine whether the customer is deemed risky. If the customer is high risk the refund is blocked and a risk work item is generated for further investigation.

The newly implemented real-time risk framework contains three different modules: Real-Time Risk (RTR) Dashboard, Rules Manager and Rules Simulator. The RTR Dashboard provides real time statistics and export functionalities to present information to be used in management information and potentially AI processes. The Rules Manager allows the business owners to manage the risk rules allowing the team complete ownership of the application The Rules Simulator provides the business owners the ability to test and simulate new or existing rules before enabling the rules in live.

The new application examines refund/repayment submissions from customers in real-time and blocks risky payments using rules created by the compliance team. Revenue can now respond immediately to new trends by simulating and then enabling new rules. This application is dynamic and the compliance team can turn rules on and off in the live environment. There is the option to analyse previous and current data using the RTR Simulator. A further development is currently underway to enable the frontline compliance team the ability to manage and create rules themselves and independently have a real time solution to risky behaviour.

Lithuania – Controlling risk in real-time

The smart tax administration subsystem (i.KON), which was implemented in 2020, allows for the identification of discrepancies in real-time, ensuring faster and more efficient processing of incoming data, and can assess tax risks more quickly. i.KON automatically selects payers based on various risk criteria.

The efficiency of the i.KON subsystem and the ability of the State Tax Inspectorate of Lithuania to properly exploit and manage the automated processes realised in the subsystem are reflected in high and improving performance. On the basis of the i.KON risk analysis, taxpayers declared an additional EUR 21 million in 2021 and EUR 59 million in 2022. It is noteworthy that these significant and growing results were achieved through relatively small investments - the development of the i.KON subsystem cost only EUR 1.5 million. Since the start of i.KON, the results of the actions carried out on the basis of i.KON risk analysis represent the majority of the results of the monitoring actions.

For a more detailed explanation see Annex 6.A.

Sources: India (2023), Ireland (2023) and Lithuania (2023).

Audits

On average, audit adjustment rates have remained stable over the period 2018 to 2021 (see Table 6.3). However, as shown in Figure 6.8., the rates vary significantly across the administrations covered by this report. The high adjustment rates can of course result from highly targeted audits, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic where some administrations focused audit activities on high-risk cases such as fraudulent activities (OECD, 2021[9]).

The importance of audits can also be seen when looking at the additional assessments raised. On average, the additional assessments raised from audits correspond to around 4% of total revenue collections. This has been relatively flat over the years 2018 to 2021 (see Table 6.3). Looking at the jurisdiction level data, it can be seen that there are significant differences across the 52 administrations that were able to provide data (see Figure 6.9.).

Table 6.3. Audit adjustment rates and additional assessments raised, 2018-2021

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Audit adjustment rates – in percent (39 jurisdictions) |

57.4 |

58.3 |

58.6 |

61.7 |

|

Additional assessments raised through audits as a percentage of tax collections (48 jurisdictions) |

4.1 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

3.9 |

Note: The table shows the average audit adjustment rates and additional assessments raised through audits (excluding electronic compliance checks) for those jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021. The number of jurisdictions for which data was available is shown in parenthesis.

Sources: Tables D.38. and D.39.

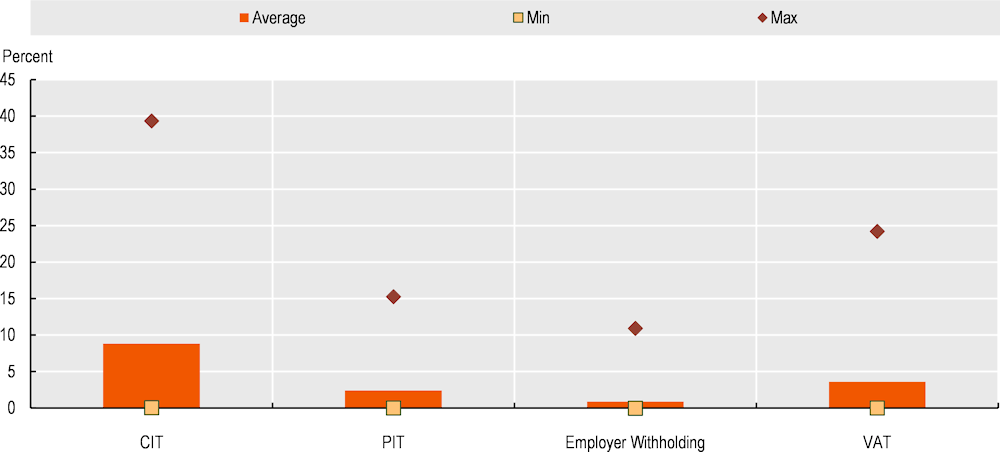

Breaking this down by tax type, it shows that the ratio of additional assessments raised to tax collected is the greatest for corporate income tax (CIT). On average, CIT additional assessment raised as a percentage of CIT collected is 8.8%, more than double the percentage for value added tax (3.6%) and more than three times the percentage for personal income tax (2.4%). (See Figure 6.10.)

In many jurisdictions, the additional assessments raised through large taxpayer offices or programmes (LTO/P) make-up a significant share of the total additional assessments raised from audits (see Figure 6.11.). On average, LTO/Ps contribute around 30% of the total additional assessments raised from audits (see Table 6.2.).

Figure 6.8. Audit adjustment rates, 2021

Figure 6.9. Additional assessments raised through audit as percentage of tax collections, 2021

Figure 6.10. Additional assessments raised through audit as percentage of tax collected by tax type, 2021

Note: CIT data for Norway has been excluded from the calculations as it would distort the average ratios.

Sources: Tables D.40. and D.41.

Figure 6.11. Additional assessments raised from audits undertaken by LTO/P as a percentage of additional assessments raised from all audits, 2021

Moving audit work to a virtual environment

Traditionally, administrations apply a variety of different audit types including comprehensive audits, issue-oriented audits, inspections of books and records, and in-depth investigations of suspected tax fraud. Often those audits require the administration to visit the taxpayer’s premises (so called field audits).

Advances in technology have led administrations to consider new ways of engaging with taxpayers during the audit process including the electronic submission of audit related documentation. This trend was accelerated as a result of the COVID-19 crisis as the closure of tax offices and the move to remote working for large numbers of tax officials changed how they approached audits.

The 2021 OECD report Tax Administration: Digital Resilience in the COVID-19 Environment (OECD, 2021[9]) observed this as well and noted that of the 32 administrations covered by that report, close to ninety percent shifted parts of their field audit work to a virtual / digital environment. Moreover, 76% of those administrations plan to continue moving field audit work to a virtual/digital environment going forward. This is supported by an increased use of technology in audits which is helping drive efficiency. Box 6.8. highlights some leading practices in that space.

Box 6.8. Examples – Technology in audits

Australia – Using automation to influence high risk tax agents

There are approximately 46 000 registered tax agents in Australia who lodge annual tax returns for nearly 6 million individual taxpayers. The ATO’s Tax Agent Strategy identifies agents who display high risk behaviour. Using automatic processes, a pilot project identified high risk lodgements and then issued a notice to the tax agent and taxpayer to substantiate work related expense claims within 28 days. Non-response results in the claims being auto-adjusted, with no need for an audit. This resulted in an effective doubling of the number of adjustments that could be completed.

See Annex 6.A for supporting material.

China (People’s Republic of) – The internal control of Smart Tax Inspection

Smart Tax Inspection is an integrated platform covering both administrative management and law enforcement aspects of tax inspection. The system can detect common operational problems at the tax official's end, and actively block the process if it does not conform to the prescribed working procedure. It is also equipped with 37 post-event automatic scanning and monitoring indicators, covering important risk nodes with regards to case selection, inspection, review and enforcement. When a risk is identified, one task to be processed will be generated and assigned to the relevant person in charge to handle and provide feedback.

It also has automatic and effective internal control over the closed cycle of tax inspection. For instance, if law enforcement risks occur to the same local inspection agency frequently in 3 consecutive months without any sign of improvement, the system will automatically remind the head of that inspection agency. Another example is, when the risk task is overdue at any link, the system will automatically generate and send reminders up to the Tax Inspection Bureau of STA headquarters, to accelerate the process.

Furthermore, multi-dimensional and smart analytics based on the internal control indicators can be generated automatically, which can help STA to identify and respond to management risks. Significant risks which frequently occur in a certain period of time can also be highlighted and circulated for action in a timely manner.

Mexico – Virtual/digital audits and data rooms

The Mexican Tax Administration Service (SAT) uses remote audit (e-audit), which permits electronic communication between auditee and auditor. The electronic signatures of the representatives of the legal entities being audited are verified by procedures such as identity validation and the Biometric Accreditation Service. The SAT IT department authorises the identity of the audit team members as their own staff or authorised personal; and all of them also use the Biometric Accreditation Service for their electronic signatures. The legal and regulatory restrictions for access to information are observed during the audits and specific information security controls and protocols are implemented for the e-audit. Different procedures are used, such as checklists, questionnaires, and interviews to review evidence, which can be provided in distinct formats (documents, video, and audio recordings).

Slovak Republic – Expert support for tax audits

A new system was developed that enables the central management of tax audits and onsite investigations and thanks to the central registration of all requests for tax audits, the complete life cycle of information is captured from its inclusion in the audit activity plan to the feedback from the actions carried out by the tax auditor.

The system also provides automated support to tax auditors for the purpose of fast and procedurally correct execution of tax audits (including support for new or less experienced tax auditors) and detailed information about the tax entity from all available databases.

It can provide a precisely defined recommended course of action for the tax auditor in the tax audit process (expert decision tree), including applicable legal norms, applicable case law in the form of sub-recommended tasks that the tax auditor is obliged to answer, and provide alerts to changes in the audited entities or related audits, helping preserve deadlines.

This is permitting reports and statistics down to the level of individual findings from the recommended actions as the manager staff gets a better overview of the activities and results of his audit department, each tax auditor’s workload, their success rate in relation to commodities, types of fraud, etc. Through this the financial administration as a whole gains more detailed insights into the audit activity, including a real-time view of the performance of the monitored indicators.

Sources: Australia (2023), China (People’s Republic of) (2023), Mexico (2023) and Slovak Republic (2023).

Tax crime investigations

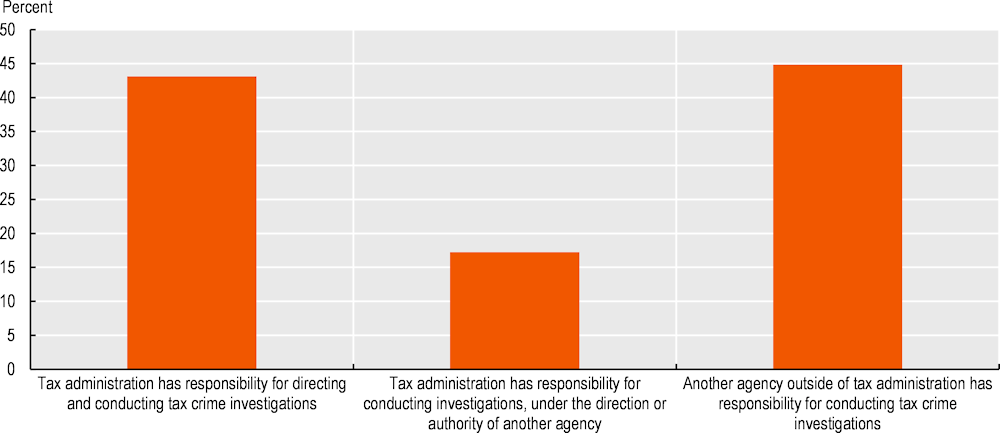

Tax crime refers to a conduct that violates a tax law and can be investigated, prosecuted and sentenced under criminal procedures within the criminal justice system. There is a range of organisational approaches for conducting tax crime investigations and the ISORA 2022 survey looked at the responsibility for directing and conducting those investigations.

The information gathered through the survey shows that 55% of the tax administrations covered in this publication are involved in conducting tax crime investigations (Table A.69.). The majority of those administrations have responsibility for both conducting and directing tax crime investigations, while the others have responsibility for solely conducting investigations, under the direction or authority of another agency, such as the police or public prosecutor (see Figure 6.12.).

In the cases of administrations that do not have any responsibility for conducting tax crime investigations, this work is done by another agency, such as the police or public prosecutor. This could also be a specialist tax agency, established outside the tax administration.

Figure 6.12. Role of administrations in tax crime investigations, 2021

Note: In some jurisdictions, the organisational approach for tax crime investigations may depend on the tax offence or tax-related criminal proceedings. In those cases, an administration may have selected multiple answer options. This is why the percentages add up to more than 100%.

Source: Table A.69.

Table 6.4. shows the total number of cases referred for prosecution during the fiscal year for the 32 administrations that have responsibility for conducting tax crime investigations. While the number of cases referred for prosecution was similar in 2018 and 2019, there was a significant reduction in the number of cases referred for prosecution during 2020 and 2021.

This is also reflected in the jurisdiction level data, which shows that around 70% of administrations that have responsibility for conducting tax crime investigations referred fewer cases for prosecution in 2021 (see Table A.69.).

Table 6.4. Evolution of tax crime investigation cases referred for prosecution between 2018 and 2021

|

Year |

No. of cases referred for prosecution during the fiscal year |

Change in percent (compared to previous year) |

|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

41 631 |

|

|

2019 |

40 426 |

-2.9 |

|

2020 |

33 874 |

-16.2 |

|

2021 |

30 490 |

-10.0 |

Note: Only includes administrations that have responsibility.

Source: Table A.69.

There could be many reasons for this reduction. This could include a genuine decline in cases, administrations reducing staff in this area as part of a wider reallocation of resources due to the pandemic, or the pandemic may have imposed constraints on the ability to refer cases for prosecution. Future editions of this series will be able to identify if the reduction this year was a ‘blip’ caused by the pandemic or the start of a long-term trend.

Finding better ways to fight tax crime is a high priority as money laundering, corruption, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes can threaten the strategic, political and economic interests of jurisdictions. Tax administrations, as gatekeepers to a sound financial system, play a critical role in countering these activities and are in possession of information that could be crucial for a successful criminal tax investigation.

Box 6.9. Tax Inspectors Without Borders for Criminal Investigation

Tax Inspectors Without Borders for Criminal Investigation (TIWB-CI) is a joint OECD/UNDP initiative which provides bilateral capacity building assistance in the area of tax crime investigation to developing countries, using the OECD Council Recommendation on the Ten Global Principles for Fighting Tax Crime (OECD, 2022[10]) as building blocks. A bespoke bilateral programme, TIWB-CI combines the technical experience of the OECD Task Force on Tax Crimes and Other Crimes (TFTC) and the ground level of presence of the UNDP, complementing other OECD tax crime multilateral initiatives such as the Academy for Tax and Financial Crime Investigation.

The TIWB-CI programme is a three-stage process starting with a country self-assessment exercise through the OECD Tax Crime Investigation Maturity Model (OECD, 2020[11]) to assess capacity gaps. During the second phase, the actual implementation process starts with the development of a work plan that defines the scope of the programme based on the self-assessment exercise, to be delivered within 18 to 24 either with the help of experts from a partner administration or a UNDP roster expert. A monitoring and evaluation framework, with success indicators, guides the implementation process.

Given the strong linkages between tax crime and other financial crimes, the TIWB-CI programme focuses on inculcating a culture of the ‘Whole of Government Approach’ by bringing all enforcement agencies together. Further, the TFTC is currently developing a new Trust Maturity Model, to ascertain the current level of trust between different stakeholders involved in financial crime investigation, with the help of a trust barometer and to identify barriers to trust, so that a proactive trust policy can be developed for operationalising the ‘Whole of Government Approach’. This online tool would assist enforcement agencies in a jurisdiction develop a common understanding of the challenges posed by illicit financial flows and a joint strategy for countering them, by pooling of resources available to various agencies.

TIWB-CI programmes are currently being implemented in eight developing countries.

Note: For more information on the OECD Academy for Tax and Financial Crime Investigation see https://www.oecd.org/tax/crime/tax-crime-academy/ (accessed on 22 May 2023).

References

[8] OECD (2022), Analytics Maturity Model, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/analytics-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[6] OECD (2022), Crypto-Asset Reporting Framework and Amendments to the Common Reporting Standard, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/crypto-asset-reporting-framework-and-amendments-to-the-common-reporting-standard.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[10] OECD (2022), Recommendation of the Council on the Ten Global Principles for Fighting Tax Crime, OECD/LEGAL/0469.

[5] OECD (2022), Tax Administration 3.0 and Connecting with Natural Systems: Initial Findings, OECD Forum on Tax Administration, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/53b8dade-en.

[9] OECD (2021), “Tax Administration: Digital Resilience in the COVID-19 Environment”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2f3cf2fb-en.

[4] OECD (2020), Code of Conduct: Co-operation between tax administrations and sharing and gig economy platforms, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/publications-and-products/code-of-conduct-co-operation-between-tax-administrations-and-sharing-and-gig-economy-platforms.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[3] OECD (2020), Model Rules for Reporting by Platform Operators with respect to Sellers in the Sharing and Gig Economy, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/tax/exchange-of-tax-information/model-rules-for-reporting-by-platform-operators-with-respect-to-sellers-in-the-sharing-and-gig-economy.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[11] OECD (2020), Tax Crime Investigation Maturity Model, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/tax/crime/tax-crime-investigation-maturity-model.htm (accessed on 22 May 2023).

[2] OECD (2019), The Sharing and Gig Economy: Effective Taxation of Platform Sellers : Forum on Tax Administration, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/574b61f8-en.

[1] OECD (2017), The Changing Tax Compliance Environment and the Role of Audit, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264282186-en.

[7] OECD (2016), Advanced Analytics for Better Tax Administration: Putting Data to Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264256453-en.

Annex 6.A. Links to supporting material (accessed on 26 May 2023)

Box 6.2. – Chile: Link to more information on the income tax dashboard: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/database/b.6.2-chile-income-tax-dashboard.pdf

Box 6.2. – Finland: Link to more information on the Income Register: https://www.vero.fi/en/incomes-register/about-us/

Box 6.7. – Lithuania: Link to a detailed description of the i.KON system: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/database/b.6.7-lithuania-controlling-risk-in-real-time.pdf

Box 6.8. – Australia: Link to more information on the ATO’s tax agent ‘active verification’ pilot: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/database/b.6.8-australia-tax-agent-pilot.pdf