This chapter looks at the resources devoted to tax administrations and provides information on their workforce. It sets out how administrations are responding to new challenges and maintain their capability while managing a workforce that in many cases is reducing in size despite added responsibilities and on average is getting older. It also explores how technology is helping tax administrations empower their workforce to deliver better solutions for taxpayers as well as provide more flexibility for the administration and its employees.

Tax Administration 2023

9. Budget and workforce

Abstract

Introduction

Central to a tax administration meeting its role in collecting revenue and providing services to citizens and businesses, is sufficient financial resources and a skilled workforce that can deliver quality outputs efficiently and effectively. This chapter examines the financial resources available to tax administrations, and how they are spent. It also provides information on tax administrations’ workforce, and how working practices are changing.

Budget and information and communication technology

Operating expenditures

The overall level of resources devoted to tax administration is an important and topical issue for most governments, external stakeholders, and of course tax administrations themselves. While the budgetary approaches differ, in most jurisdictions the budget allocated is tied to the delivery of performance outputs which are outlined in an annual business plan.

When looking at the budget figures, close to 80 percent of tax administrations report an increase in their operational expenditure between the years 2020 and 2021. This is slightly more administrations reporting an increasing budget than during the previous periods (see Table 9.1.).

However, this data should be treated with caution. While on paper a significant number of administrations saw increases in their budget, this does not take into the account the increases in responsibilities that many administrations are reporting, especially as a result of additional pandemic responsibilities, as well as any inflationary pressures.

Table 9.1. Changes in operating expenditures, 2018-2021

Percent of administrations

|

Change |

Between 2018 and 2019 |

Between 2019 and 2020 |

Between 2020 and 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Increase in operating expenditure |

75.5 |

71.7 |

77.4 |

|

Decrease in operating expenditure |

24.5 |

28.3 |

22.6 |

Note: The table is based on the data from 53 jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021.

Source: Table A.16.

This issue is compounded as a significant part of the budgets is needed for salary costs, accounting for on average 73% of operating budgets annually (see Table D.6.). Any increases in budgets can be rapidly consumed by salary increases, which may be a contractual obligation. This mix of greater responsibility, and pressured budgets, is driving tax administrations to find innovative approaches, often using technology, so they can meet budgetary constraints, continue to deliver efficient services to taxpayers, and focus on the relevant compliance risks.

As tax administrations reflect on the working practices established as part of the pandemic response, the impact of longer-term hybrid or remote working is also being considered. This was explored in more detail in the OECD report Tax Administration: Towards sustainable remote working in a post COVID-19 environment (OECD, 2021[1]), and the examples in Box 9.1. set out some of the new working practices being adopted after the pandemic.

Box 9.1. Examples – New working practices

Chile – Automatic messaging system of electronic receipts with taxpayers

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulty of on-site tax inspection, the Servicio de Impuestos Internos (SII) needed to find a solution to control the issuance of electronic receipts in near real-time. In this context, a system with the capability to create alerts from the processing electronic receipts, both near real-time and batch, was developed. This system continues to be used post-pandemic.

The model consists of four main components: clustering, definition of alerts, automatic messaging system and data visualisation.

The process starts with the definition of who are the taxpayers that are required to issue electronic receipts. Then, the system clusters some of those taxpayers by business type. Currently, there are ten clusters: liquor store, bakery, restaurant, greengrocers, butcher shop, drugstore, flower shop, jewellers, minimarket, and hardware store.

SII has created a set of alerts based on mathematical algorithms that monitor and detect anomalous patterns in electronic tax documents issuance from these clusters. After identifying the taxpayers obligated to issue electronic receipts, those who meet the conditions to be targeted for a message are identified. Finally, with all the data gathered by the system, a dashboard to visualise the information is created.

See Annex 9.A. for supporting material.

Mexico – Supporting the digital workplace

The Mexican Tax Administration Service (SAT) has invested in mobility services to promote remote work, resulting in increased staff productivity and substantial savings for the institution. A key component of this initiative has been the provision of Virtual Private Networks to enable secure remote access to the institutional network. This measure has not only saved staff time but also allowed the institution to reduce its office-related costs.

Romania – Webinar for meetings with taxpayers

During the pandemic the Romanian tax administration adopted restrictive measures regarding the access of taxpayers to the tax administration offices. In order to maintain service to taxpayers, the Romanian tax administration implemented a webinar service, which was launched in 2022. The webinars are conducted by regional offices representatives and the webinar details are publicised on the tax administration website, which also handles registration for the webinar.

The webinars are organised both to inform the taxpayers of their fiscal obligations and to answer their questions related to the topic, in order to improve voluntary compliance. The webinars last two hours and taxpayers can ask questions either in writing through the question-and-answer section or verbally using the "raise hand" function.

The webinars take place monthly and the platform permits statistical reporting regarding the number of registered people, the number of participants and the number of questions asked through the question-and-answer section.

Sources: Chile (2023), Mexico (2023) and Romania (2023).

Components of tax administration operating expenditure

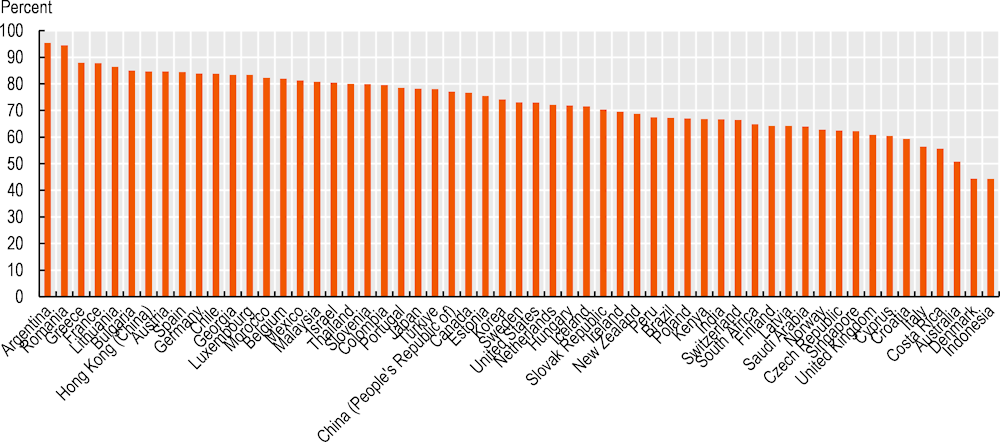

As stated earlier, the largest reported component of tax administration operating budgets is staff costs, with salary alone accounting for on average 73% of operating budgets annually, even though there are some differences among jurisdictions (see Figure 9.1.). Another important component is the operating cost for information and communication technology (ICT). On average this accounts for 11% of operating expenditure, with a few jurisdictions reporting ICT expenditure above 20% of their total operating expenditure (see Table D.6.). The averages for both items (salary and ICT) have remained stable over the past years.

Figure 9.1. Salary cost as a percent of total operating expenditure, 2021

Capital expenditure

Capital expenditure makes-up about 4.7% of total expenditure on average but varies significantly between administrations. A few administrations report figures below 1% while others report figures above 10% (see Table A.17).

Cost of collection

It has become a fairly common practice for tax administrations to compute and publish (for example, in their annual reports) a “cost of collection” ratio as a surrogate measure of their efficiency / effectiveness. The ratio is computed by comparing the annual expenditure of a tax administration, with the net revenue collected over the course of a fiscal year. Given the many similarities in the taxes administered by tax administrations, there has been a natural tendency by observers to make comparisons of “cost of collection” ratios across jurisdictions. Such comparison have to be treated with a high degree of caution, for reasons explained in Box 9.2.

In practice there are a number of factors that may influence the cost/revenue relationship, but which have nothing to do with relative efficiency or effectiveness. Examples of such factors and variables include macroeconomic changes as well as differences in revenue types administered. These factors are further elaborated in Box 9.2.

Despite those factors, the “cost of collection” ratio is included in this report for two reasons:

1. The “cost of collection” ratio is useful for administrations to track as a domestic measure as it allows them to see the trend over time of their work to collect revenue and, as pointed out in Box 9.2., they may be able to account for the main factors that can influence the ratio; and

2. The inclusion of the “cost of collection” ratio and the accompanying comments set out in Box 9.2. can serve as a prominent reminder to stakeholders of the difficulties and challenges in using the easily calculated “cost of collection” ratio for international comparison.

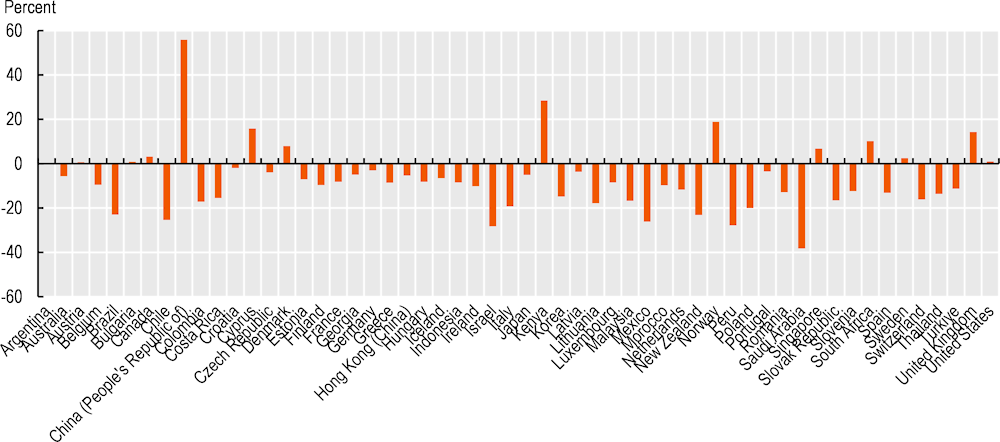

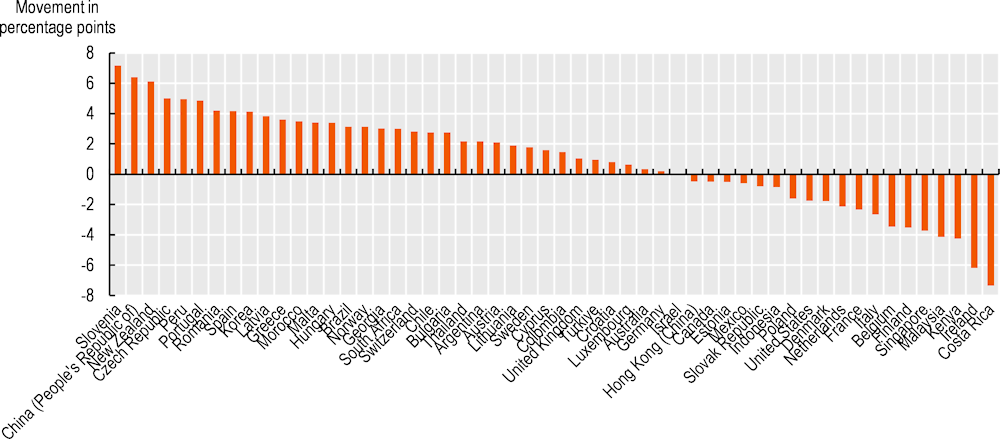

Table 9.2. illustrates the change in the “cost of collection” ratios between 2018 and 2021 for the administrations included in this report. It shows that close to eighty percent of the administrations had decreasing ratios between 2020 and 2021, in contrast to the around eighty percent of administrations which had increasing ratios over the period 2019 to 2020. Figure 9.2. looks at the movement in the “cost of collection” ratios between 2020 and 2021 from a jurisdiction-level perspective. However, as mentioned in Box 9.2., the chart and the underlying figures have to be interpreted with great care.

Table 9.2. Changes in “cost of collection” ratios, 2018-2021

Percent of administrations

|

Change |

Between 2018 and 2019 |

Between 2019 and 2020 |

Between 2020 and 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Increase in cost of collection |

45 |

82 |

22 |

|

Decrease in cost of collection |

55 |

18 |

78 |

Note: The table is based on the data from 55 jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021.

Source: Table D.6.

Figure 9.2. Movement in “cost of collection” ratios between 2020 and 2021

Note: When interpreting this chart the factors mentioned in Box 9.2. should be taken into account. Data for India has been excluded, see note in Table A.16.

Source: Table D.6.

Box 9.2. Difficulties and challenges in using the “cost of collection” ratio as an indicator of efficiency and/or effectiveness

Observed over time, a downward trend in the “cost of collection” ratio can appear to constitute evidence of a reduction in relative costs (i.e., improved efficiency) and/or improved tax compliance (i.e., improved effectiveness). However, experience has also shown that there are many factors that can influence the ratio which are not related to changes in a tax administrations’ efficiency and/or effectiveness and which render this statistic highly unreliable in the international context:

Changes in tax policy: Tax policy changes are an important factor in determining the cost/revenue relationship. In theory, a policy decision to increase the overall tax burden should, all other things being equal, improve the ratio by a corresponding amount, but this has nothing to do with improved operational efficiency or effectiveness.

Macroeconomic changes: Significant changes in rates of economic growth etc. or inflation over time are likely to impact on the overall revenue collected by the tax administration and the cost/revenue relationship.

Abnormal expenditure of the tax administration: From time to time, a tax administration may be required to undertake an abnormal level of investment (for example, the building of a new information technology infrastructure or the acquisition of more expensive new accommodation). Such investments are likely to increase overall operating costs over the medium term, and short of offsetting efficiencies which may take longer to realise, will impact on the cost/ revenue relationship.

Changes in the scope of revenues collected: From time to time, governments decide to shift responsibility for the collection of particular revenues from one agency to another which may impact the cost/revenue relationship.

From a fully domestic perspective, an administration may be able to account for those factors by making corresponding adjustments to its cost or collected revenue. This can make tracking the “cost of collection” ratio a helpful measure to see the trend over time of the administration’s work to collect revenue. If it were gathered by tax type, it may also help inform policy choices around how particular taxes may be administered and collected.

However, its usefulness with respect to international comparison is very limited. While administrations may be able to account for the above factors from a domestic perspective, it will be difficult to do this at an international level as such analysis would have to consider:

Differences in tax rates and structure: Rates of tax and the actual structure of taxes will all have a bearing on aggregate revenue and, to a lesser extent, cost considerations. For example, comparisons of the ratio involving high-tax jurisdictions and low-tax jurisdictions are hardly realistic given their widely varying tax burdens.

Differences in the range and nature of revenues administered: There are a number of differences that can arise here. In some jurisdictions, more than one major tax authority may operate at the national level, or taxes at the federal level may be predominantly of a direct tax nature, while indirect taxes may be administered largely by separate regional/state authorities. In other jurisdictions, one national authority will collect taxes for all levels of government, i.e., federal, regional and local governments. Similar issues arise in relation to the collection of social insurance contributions.

Differences in the range of functions undertaken: The range of functions undertaken by tax administrations can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, in some jurisdictions the tax administration is also responsible for carrying out activities not directly related to tax administration (for example, the administration of certain welfare benefits or national population registers), while in others some tax-related functions are not carried out by the tax administration (for example, the enforcement of debt collections). Further, differences in societal views may influence what an administration does, how it can operate and what services is has to offer. The latter may have a particularly significant impact on the cost/revenue relationship.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the “cost of collection” ratio ignores the revenue potential of a tax system, i.e., the difference between the amount of tax actually collected and the maximum potential revenue. This is particularly relevant in the context of international comparisons – administrations with similar cost/revenue ratios can be some distance apart in terms of their relative effectiveness.

Information and communication technology

On average ICT expenditure accounts for about 11% of operating expenditure. However, reported levels of ICT expenditure vary enormously between administrations. For those administrations able to provide ICT-related cost, around 50% reported an annual operating ICT expenditure exceeding 10% of the administration’s total operating expenditure in 2021 and another 20% reported figures between 5% and 10% (see Table D.6). While some of this variation can be explained by the different sourcing and business approaches, some cannot and point, at least on the surface, to expenditure levels that maybe somewhat below the support needed to provide the rapidly changing electronic and digital services administrations are increasingly being called upon to deliver. In parallel to this, administrations report that they are investing more in their cybersecurity practices, which are needed to protect the integrity of their system and maintain taxpayer trust. Box 9.3. and Chapter 10 on digital transformation highlight some of the practices in this field.

Box 9.3. Examples – Investment in cyber security

Australia – System integrity measures against cybercrime

One of the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) innovations to fight cybercrime is the implementation of the new System Integrity Program and its Vulnerability Assessment Methodology. This contemporary methodology seeks to understand weaknesses in existing business processes and user pathways, and test the exposure to external fraud and cybercrime threats across the end-to-end tax and superannuation ecosystem. The method allows the ATO to consider where additional countermeasures may be needed to prevent cybercrime and external fraud occurring from a whole-of-system perspective.

See Annex 9.A. for supporting material.

Mexico – Innovations in the fight against tax cybercrime

Event correlation is using analytics to identify and understand patterns in historical and online data to better locate and mitigate potential security threats. Its main objective is to identify anomalous behaviours and support the establishment of responsibilities in registered actions, using the activity audit trails generated by network connections, browsing history, user accounts, among others.

SAT uses a specialized system for the collection and analysis of information systems records (SIEM) as well as specialised infrastructure for the analysis of the information contained in the SIEM. In addition, staff are trained in the use of analysis tools and the investigation of information systems records Current legislation must be constantly reviewed in terms of information retention periods. In addition, attention must be paid to preserving the integrity of the logs, developing event correlation rules to generate alerts to those responsible for them and monitoring, updating and retraining of analytical models.

Sources: Australia (2023) and Mexico (2023).

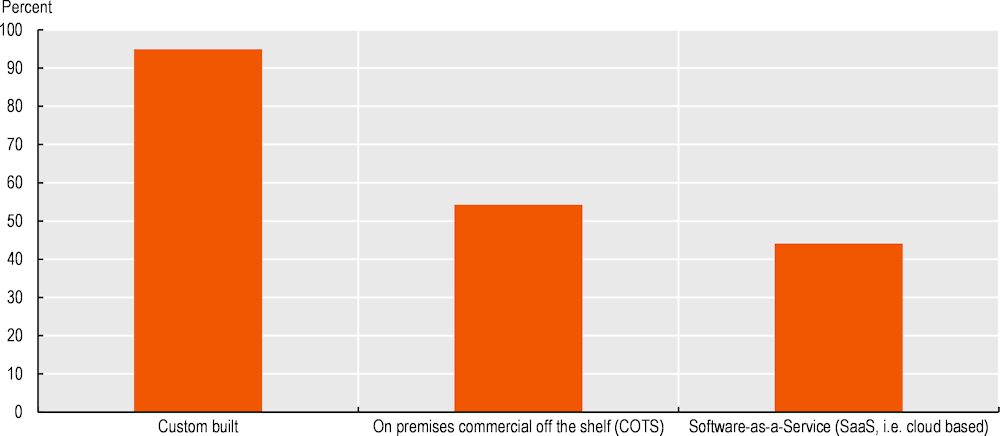

As regards the operational ICT solutions (i.e., solutions that are used to fulfil the tax administration's mandate and include systems for registration, return processing, payment processing and auditing), almost all tax administrations report using custom built ICT solutions, while 55% report also using commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) solutions (see Figure 9.3.).

Figure 9.3. Basis of ICT solutions of tax administrations, 2021

In addition, around 45% of the administrations report using software-as-a-service (SaaS) solutions. These are software licensing models where the tax administration pays for a subscription license and the cost depends on the usage. The software is installed on third party computers, not on tax administration computers, and is accessed by users via the internet. One of the main barriers to adopting SaaS more widely, is the storage of sensitive tax data on these third-party systems. As more legislative and technological solutions are identified, including regarding the encryption of data, it is possible the use of SaaS will increase.

Workforce

In 2021, the administrations included in this report employed approximately 1.7 million staff (see Table A.18.) making the effective and efficient management of the workforce critical to good tax administration. Having a competent, professional, productive and adaptable workforce is at the heart of most administrations’ human resource planning. With salary costs averaging more than 70% of operating expenditures, any significant budget change invariably impacts staff numbers.

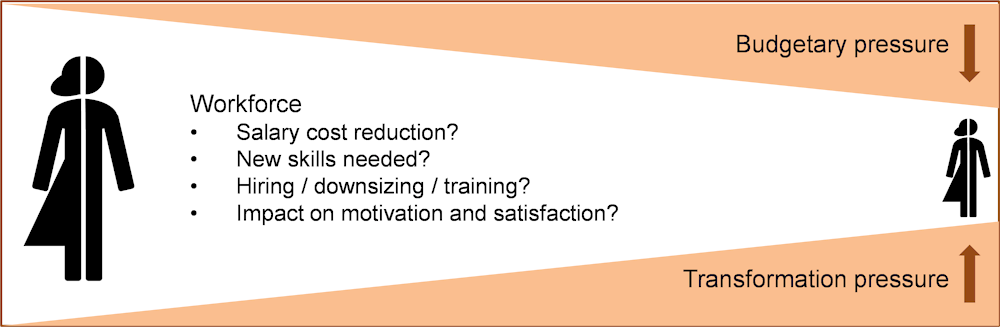

The “double pressure” created from reduced budgets and technology change, mentioned in the 2017 edition (OECD, 2017[2]) (see also Figure 9.4.), continues to be a significant management issue for most administrations. The challenge is compounded for some administrations which, due to contract restrictions or government mandates, may find it difficult to strategically down-size their operations other than through the non-replacement of staff who leave of their own accord.

Figure 9.4. Double pressure on the workforce

Staff usage by function

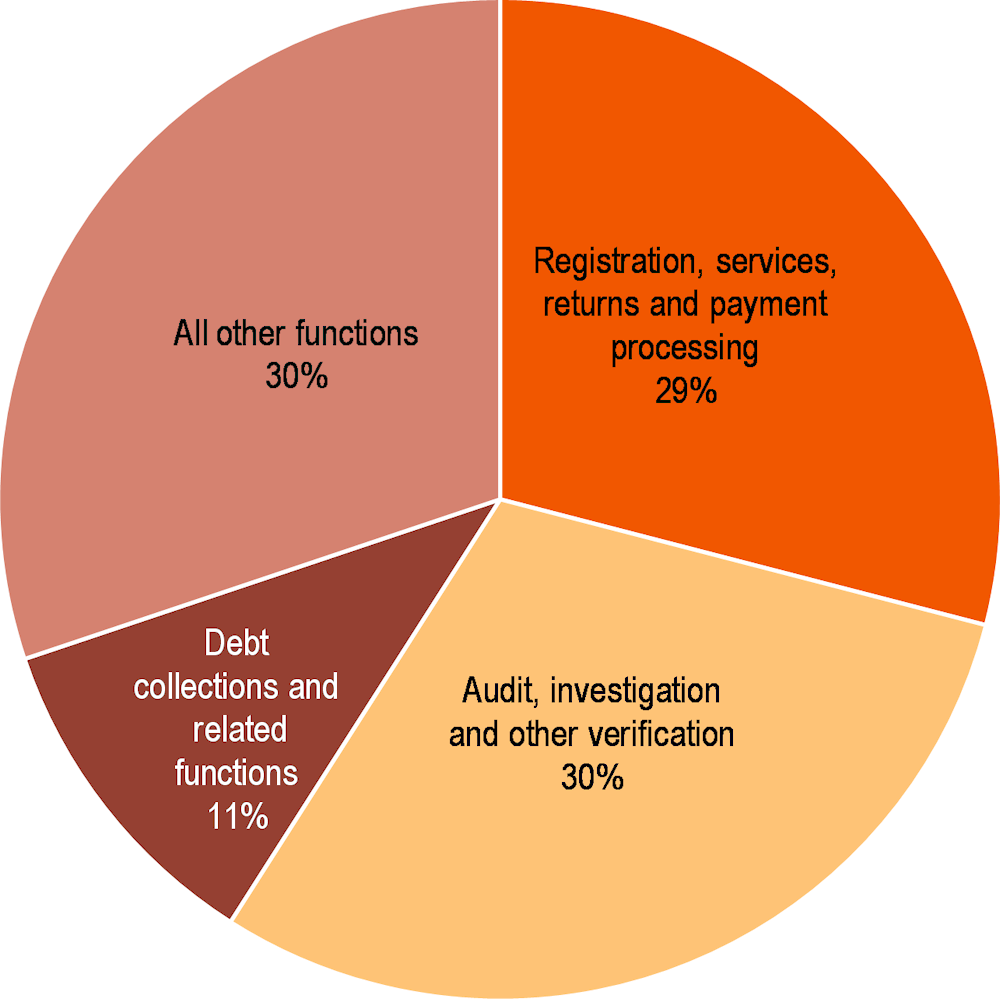

Figure 9.5. provides average allocation of staff resources (expressed in full-time equivalents) across four functional groupings used to categorise tax administration operations.1 While the detailed data for each administration in Table D.8. shows a significant spread of values and a number of outliers for each function, on average the “audit, investigation and other verification” function and the “registration, services, returns and payment processing” function are equally resource intensive, each employing on average thirty percent of staff. Both ratios have remained stable over recent years.

Figure 9.5. Staff usage by function, 2021

Note: Excluding administrations that were unable to provide the break-down for all functions.

Source: Table D.8.

Staff metrics

ISORA 2022 also gathered key data concerning the age profiles, length of service, gender distribution and educational qualifications of tax administration staff: see Tables D.10. to D.15. and A.24. to A.31. In interpreting this data there are two main considerations to bear in mind:

Combined tax and customs administrations were allowed to use their total workforce for answering the underlying survey questions as it may be difficult for them to separate the characteristics of the tax and customs workforce.

Since ISORA 2020, staff metrics information is collected for the total number of staff, whereas in previous ISORA rounds (i.e., ISORA 2016 and 2018) staff metrics information was collected for permanent staff only. Trend analysis comparing staff metrics across the different ISORA surveys should therefore be conducted with caution. In particular for administrations that employ a significant number of non-permanent staff, this change in methodology may cause a shift in staff-metric-percentages that is not based on regular staff fluctuations but rather a result of including a different group of staff.

Age profiles

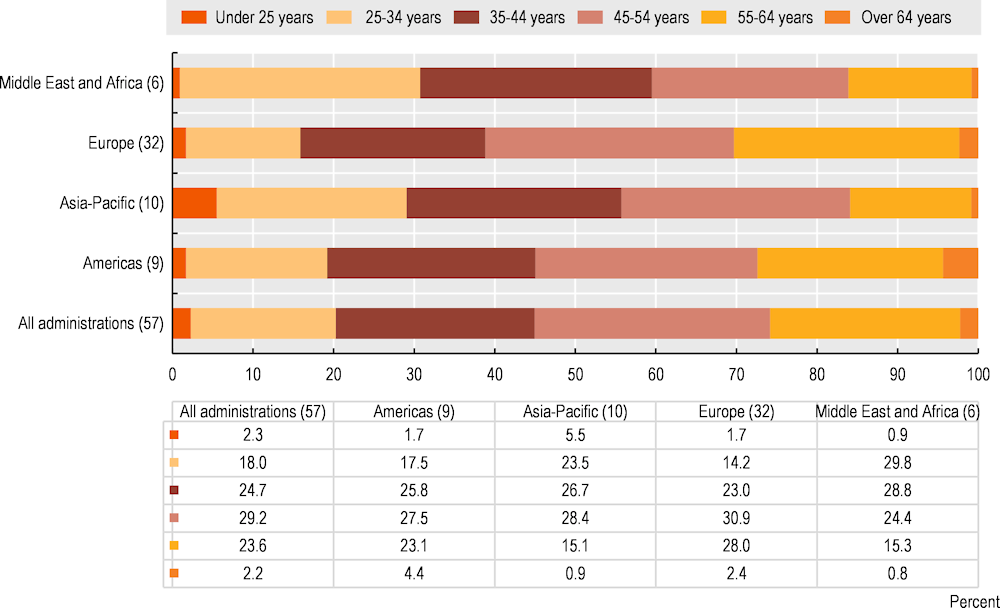

While there are significant variations between the age profiles of tax administration staff (see Tables D.11. and D.12.), it is interesting to see that there are also differences when viewed across different regional groupings. This may be the result of a complex mix of cultural, economic, and sociological factors (for example, economic maturity, recruitment, remuneration, and retirement policies).

Figure 9.6. illustrates that staff are generally younger in administrations in the regional groupings of “Asia-Pacific” and “Middle East and Africa” where, on average, around thirty percent of staff are below 35 years of age, whereas in the “Americas” and “Europe” this percentage drops to below twenty percent. At the same time, administrations in the “Americas” and “Europe” have a large percentage of staff older than 54 years.

Looking at the jurisdiction specific data, the percentage of staff older than 54 years grew in two-thirds of administrations over the period 2018 to 2021 (see Figure 9.7.).

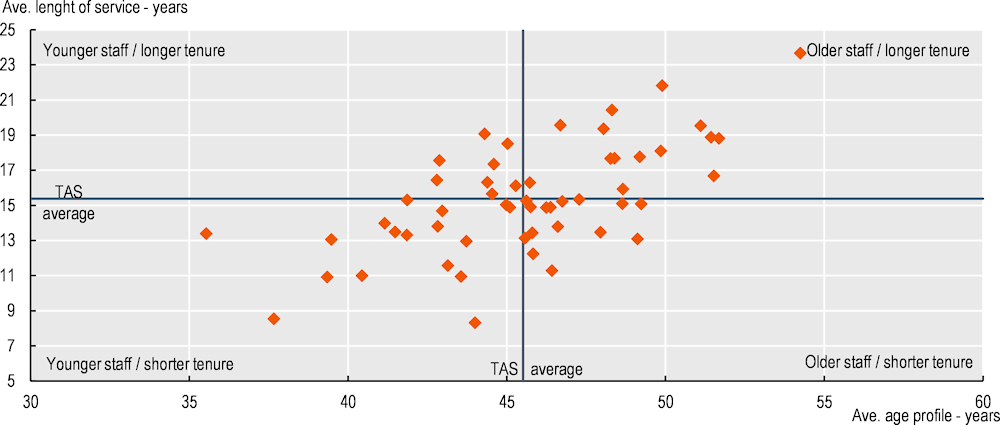

Length of service

The difference in age profiles is also largely reflected in the length of service of tax administration staff. Figure 9.8. indicates that a significant number of administrations will not only face a large number of staff retiring over the next years, but that many of these staff will be very experienced, thus raising further issues about retention of key knowledge and experience.

Figure 9.6. Age profiles of tax administration staff, 2021

Note: The following administrations are included in the regional groupings: Americas (9) – Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Peru and the United States; Asia-Pacific (9) – Australia, China (People’s Republic of), Hong Kong (China), Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Thailand; Europe (32) – Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom; Middle East and Africa (6): Israel, Kenya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Türkiye.

Source: Table D.12.

Figure 9.7. Staff older than 54 years: Movement between 2018 and 2021

Note: Only includes jurisdictions for which data was available for both years. Data for Iceland and Saudi Arabia has been excluded due to the mergers of the tax administration with the customs administration.

Source: Table D.12.

Figure 9.8. Average length of service vs. average age profile, 2021

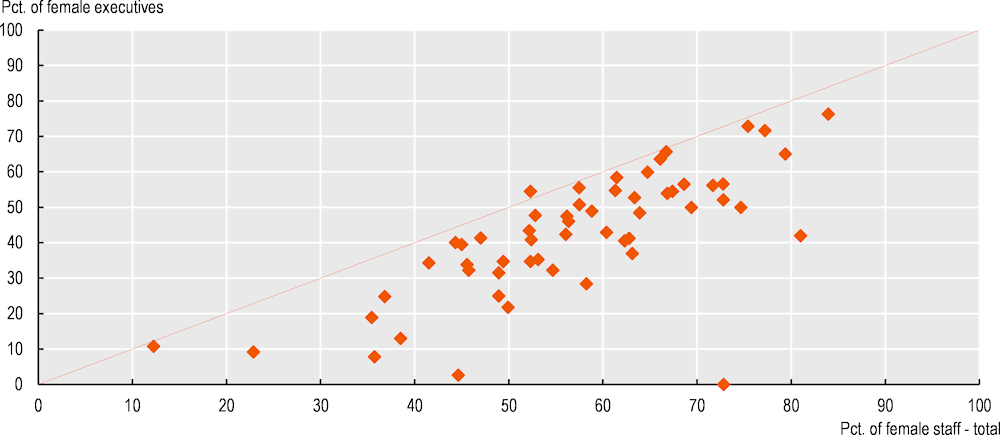

Gender distribution

In light of the strong public interest in gender equality, administrations were invited to report total staff and executive staff respectively by gender. As can be seen in Figure 9.9., while many administrations are close to the proportional line, typically female staff remains proportionally underrepresented in executive positions and significantly underrepresented in a number of administrations, something that has remained unchanged since the 2017 edition of this report (OECD, 2017[2]).

Figure 9.9. Percentage of female staff – total female staff vs. female executives, 2021

Looking at the overall averages, whilst there are variations between jurisdictions (see Table D.15.), on average the share of female employees of total staff and executive staff has remained largely unchanged since 2018, with a very small increase of around 4 percent of female executives (see Table 9.3.). The jurisdiction-level data shows that in about two-thirds of administrations the percentage of female executives has increased since 2018 (see Table D.15.).

Table 9.3. Evolution of share of female staff and female executives (in percent)

|

Staff category |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Change between 2018 and 2021 in percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Female staff (56 jurisdictions) |

56.9 |

57.6 |

57.5 |

57.6 |

+1.2 |

|

Female executives (55 jurisdictions) |

40.2 |

41.9 |

41.6 |

42.6 |

+4.2 |

Note: The table shows the share of female employees of total staff and executive staff for those jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021. The number of jurisdictions for which data was available is shown in parenthesis.

Source: Table D.15.

The ISORA survey also asked administrations to indicate whether staff has self-identified as neither female nor male (referred to as “other” gender for the purposes of the survey). Table A.31. shows that two administrations, Australia and New Zealand, reported having staff who self-identified as “other”.

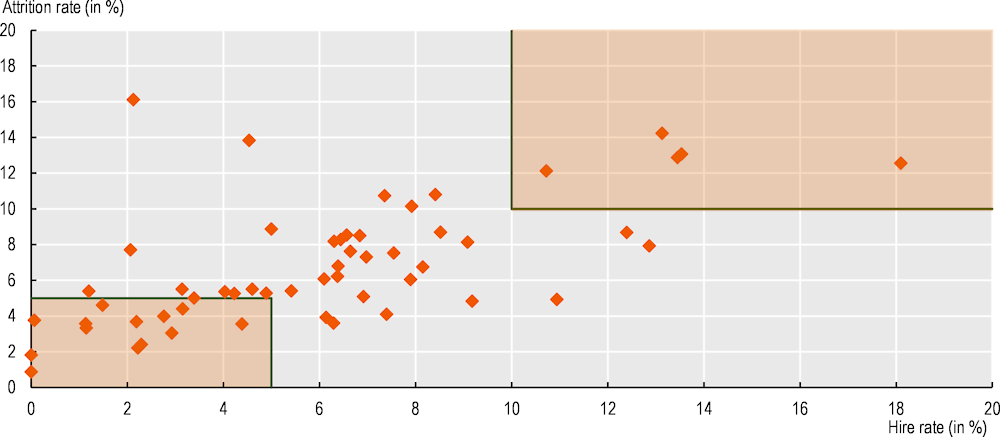

Staff attrition

Staff attrition, also called staff turnover, refers to the rate at which employees leave an organisation during a defined period (normally a year). High attrition rates may result from a variety of factors, such as downsizing policies, demographics or changing staff preferences. The attrition rate should be considered together with other measures, such as the hire rate, which looks at the number of staff recruited during a defined period, when evaluating the human resource trends of an administration.

While a high attrition rate combined with a low hire rate is usually associated with a general downsizing policy – and may therefore be accepted – administrations should be concerned where both rates are high. Recruitment is costly, not only the recruitment process itself but also the cost and time for training and supporting new staff members, and the significant down time before new staff are fully operational or able to perform at the highest level. Having high attrition rates are generally to be avoided.

Having attrition rates that are too low may also not be ideal. While an organisation is growing, a low attrition rate may be accepted. However, in situations where both the attrition rate and the hire rate are low, an organisation may not have the ability to recruit new skills as all positions are filled. This could be an issue particularly for administrations that are undergoing transformation and therefore are in need of staff with skills that are different from what is currently available within the administration.

While what is considered a “healthy” attrition rate differs between industry sectors or jurisdictions, the average attrition rate for administrations participating in this publication of 6.8% in 2021 and the average hire rate of 5.9% in 2021 would seem to present a reasonable range for tax administrations of between 5% and 10%. It is worth noting that the average hire rate for 2021 continues to be below those reported in 2018 and 2019, which may be a pandemic related impact. At the same time, the average attrition rate for 2021 is now back to pre-pandemic levels. (See Table 9.3.)

Table 9.4. Evolution of attrition and hire rates (in percent)

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

Change between 2018 and 2020 in percent |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Attrition rates (50 jurisdictions) |

6.6 |

7.1 |

6.0 |

6.8 |

+2.8 |

|

Hire rates (50 jurisdictions) |

6.8 |

7.0 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

-11.9 |

Note: The table shows the average attrition and hire rates for those jurisdictions that were able to provide the information for the years 2018 to 2021. The number of jurisdictions for which data was available is shown in parenthesis. Data for China (People’s Republic of), Iceland, Norway and Saudi Arabia were excluded from the calculation as the result of extraordinary staff transfers over the period 2018 to 2021 which were recorded as recruitments, thus distorting their averages for those years (see notes in Table A.23).

Source: Table D.9.

However, when looking at specific administration data, it becomes apparent that “attrition and hire” rates cover a very broad range. Figure 9.10. shows the relationship between tax administration attrition and hire rates. It illustrates that there are a number of administrations with attrition and hire rates well above 10% (upper-right box), while others show very low attrition and hire rates (lower-left box).

Figure 9.10. Attrition and hire rates, 2021

Note: Attrition rate = number of staff departures/average staffing level. Hire rate = number of staff recruitments/ average staffing level. The average staffing level equals opening staff numbers + end-of-year staff numbers/2.

Source: Table D.9.

Whilst recruitment rates may vary by year, the challenge of training and knowledge transfer are constant. The COVID-19 pandemic brought these issues into sharp focus as HR processes that previously relied on face-to-face contact, had to be conducted remotely. Tax administrations report that these practices brought significant benefits to the administration and candidates, and as a result they are now being adapted for the longer term. Box 9.4. illustrates some of the innovative approaches being used both to attract candidates to the tax administration and to also digitise those processes.

Box 9.4. Examples – Enhancing HR processes

France – Changing recruitment processes

The French tax administration (DGFiP) has significant recruitment needs to meet the demands of its various departments and to compensate for retirements. In 2022, it has recruited more than 3 700 new employees, two-thirds of whom were hired through competitive examinations and one-third through contractual arrangements.

Recruitment by contract is on the rise, which means that in a context of tension on the labour market, recruitment techniques must be optimised to increase the pool of candidates and the diversity of profiles. In this context, the DGFiP is experimenting with innovative tools such as sourcing and pre-recruitment:

Sourcing, based on criteria defined upstream, analyses the data present on the many professional platforms, job sites, CV libraries, and other social networks. This method makes it possible to detect the profiles that best meet expectations. The results produced by these algorithms combine both the quantity and quality of the selected profiles.

Once the pool has been constituted, the recruitment phase begins. In order to better assess the aptitudes, interpersonal skills and reasoning of candidates, new IT solutions make it possible to create an evaluation process centred on the candidates, inviting them to complete a circuit composed of a series of mini-games assessing different cognitive skills. This playful, innovative and original method also ensures a more attractive image for the DGFiP employer brand.

The use of these new tools will make it possible to transform the recruitment method by going beyond the classic analysis of the curriculum vitae. It will reveal the true potential of candidates while ensuring a fairer and more diversified recruitment.

Japan – Recruitment of digital talent and human capital support

In June 2021, the National Tax Agency (NTA) published its ‘Digital Transformation of Tax Administration - Future Vision of Tax Administration 2.0’ which sets out how to improve tax administration by exploiting the advantages of digital technology.

For this to be successful, it is crucial to recruit and retain people from science and engineering backgrounds who are considered to have a background in information and communication technology. Accordingly, from fiscal year 2023 onwards, the NTA has created a new entry examination category with subjects such as mathematics and computer science, which are more familiar to students in science and engineering fields.

The NTA has also focused on developing human resources through a training system based on data literacy with levels from Entry to Expert that allows staff to build their knowledge in this crucial field. At the Expert level staff have sophisticated expertise in statistical science and machine learning, and the development of a predictive models.

See Annex 9.A. for more information.

Latvia – Digitisation of recruitment processes

Job advertisements posted on the State Employment Agency portal automatically migrate to the State Revenue Service portal vacancies section, indicating the place of work (in person, partially remotely, or completely remotely).

After evaluation of applications, candidates are forwarded to the next round for a remote test. On the day of the test, a test task or a link to the platform is sent to the applicant's e-mail. Candidates are also invited to participate in a remote interview via video call.

Successful candidates are informed digitally, and the subsequent induction and training takes place both remotely and in person, depending on the specifics of the job.

Sources: France (2023), Japan (2023) and Latvia (2023).

Supporting staff

The changes tax administrations are managing, whether technology, policy or budget driven, are constant. In addition, the wider digital transformation of the economy is changing the service expectations of taxpayers, and staff need the right tools and support to adapt. As a result, tax administrations are considering the best way to support staff through these changes, as well as ensuring they have the right tools for the tasks.

Tax administrations are also reporting that they are investing in services that can help ‘frontline’ staff better understand taxpayer needs and provide better services to them. This can cover a range of channels from call centres through to social media. These investments are allowing tax administrations to provide improved services, and their staff feel better equipped to deliver those high-quality services. Tax administrations also report that sophisticated analytics are being used to match staff skills to taxpayer needs. Box 9.5. highlights how France is using the sizeable amount of data it has on staff to build management tools that give insight into the staff profiles and where development gaps exist.

Box 9.5. France – HR data lake

The DGFiP has more than 97 000 employees, spread across over a 100 local divisions and several hundreds of physical locations. It has set up a data lake into which all of its data will be stored. This will include all data concerning human resources (HR), in order to stimulate their use through data visualisation tools.

In the future, all the data stored in the various HR-related applications will be put into the data lake, whether the data concerns personal information about employees, their career path, including outside the DGFiP or their vocational training. Data related to DGFiP’s recruitment efforts will also be included. It will therefore become possible to run data analysis on all of this information, which until now is stored and processed separately, and to ensure, for instance, a better knowledge and understanding of the employees’ profile.

Already, thanks to the pooling of data and using the possibilities offered by data visualisation, the DGFiP is building a dashboard designed to facilitate the management of human resources. The dashboard presents a large number of indicators in a lively and interactive manner. Indicators belong to 6 categories: headcount, vocational training, working time, health and safety, recruitment, and equality and diversity. Offering up-to-date and easy-to-use information, the dashboard is a very useful management tool. Most of the indicators offer a national view with a depth of several years, which makes it possible to identify trends and even structural changes. In addition, the tool offers the possibility to quickly make comparisons between local directorates and reveal possible disparities between territories.

Source: France (2023).

Anecdotal evidence, gathered through numerous Forum on Tax Administration (FTA) meetings, shows that tax administrations put considerable efforts into supporting staff during periods of transition, considering issues such as:

Staff welfare, which includes looking into staff motivation and satisfaction, health and safety related issues, work-life balance, assistance programmes, and ergonomic office equipment; and

Staff training, which includes how to best support those that have been given new tasks, those that have to perform their tasks from home instead of the office, as well as those that are leading partially or wholly virtual teams for the first time.

Technology is also providing new opportunities to analyse existing processes to look for efficiencies, including through the use of artificial intelligence, machine learning and robotic process automation (RPA) to automate some of the core tasks within a tax administration. Box 9.6. illustrates the wide range of uses that automation is being put to.

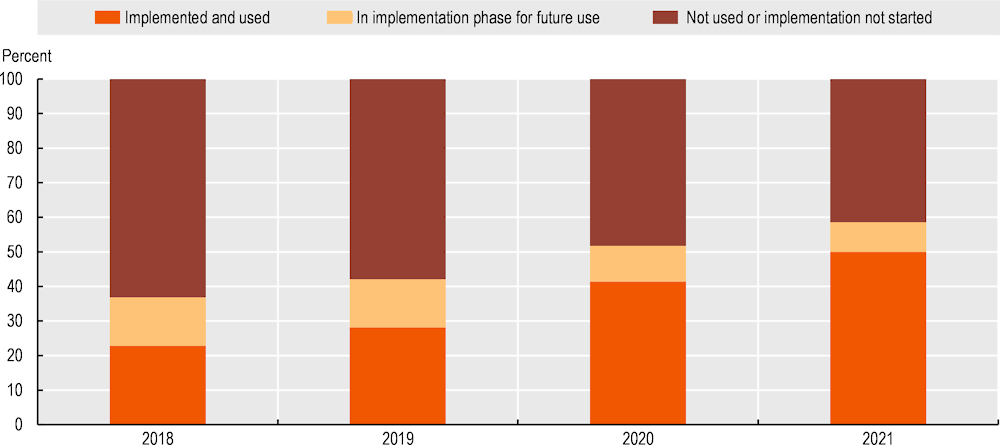

Table 6.1. in Chapter 6 highlights the rapid growth in the use of such services with for example, more than 50% of administrations reporting that they now using or planning to use RPA. (See also Figure 9.11. for the up-take of RPA by tax administrations over the years.) This is helping tax administrations respond to budgetary and workforce pressures as it is freeing up resource for staff to be focussed on more complex tasks.

Figure 9.11. Evolution of the implementation and use of Robotic Process Automation, 2018 to 2021

Box 9.6. Examples – Automation in tax administration

Argentina – Digital single file

Under this project the Argentinian tax administration (AFIP) will have a single digital file of all the documentation submitted by taxpayers, meaning that once submitted it can be used across a wide range of areas and procedures.

This means that if, for example, a taxpayer files a title deed digitally, the document will not have to be submitted again in the future and it can be used for other procedures such as for a tax audit, or an application for a fiscal benefit.

This saves the taxpayer time and money as the document will not have to be certified again and removes the need for AFIP to store the same document in multiple units.

Canada – Digital Document Management Program

In May 2022, the Digital Document Management Program (DDMP) was established to enable the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to transition from internal paper-based processes and to enhance its existing digital processes. Despite the shift towards digital services, there continues to be a high volume of paper mail received by the CRA. The intent of the DDMP is to reduce the overwhelming burden of incoming high volume paper mail by converting incoming documents from taxpayers into a digital format.

The DDMP offers five standardised capabilities to onboarded programmes. It operates in partnership with an external contracted Managed Service Provider (MSP) to which mail is re-directed and prepped for imaging. Images are digitised and uploaded into a digital document repository, where internal CRA users can virtually view documents and access workloads. These documents are well defined, catalogued and easily accessible so that users can view and share information within a timely fashion. Data from each in-scope document can also be extracted by the MSP and delivered to the CRA, ready to be incorporated into the CRA systems. The repository can also store digitised documents received through the CRA’s Submit Docs channel, which solicits and receives digital copies of records from taxpayers and can also receive eFax submissions from various sources.

France – Automation in VAT refunds

A digital assistant is software that allows the automation of certain actions (typing, clicks, etc.) and that interacts as an agent would through a screen and a mouse. This automation of processes by robotics reproduces the tasks that agents perform routinely. It is suited to repetitive tasks that do not require complex intellectual analysis and are particularly time consuming.

The French tax administration has developed several digital assistants, including one that compares daily lists of beneficiaries of VAT credit refunds about to be issued with lists of collection orders for which the deadline for a payment date has passed, in order to identify VAT credit refunds that may be subject to administrative attachment.

Currently, the digital assistant is used for so-called non-fiscal debts (for example, penalties issued by various administrative bodies that the tax administration is responsible for collecting) but its extension to fiscal debts is being considered.

On average, it takes about 6 months and costs approximately EUR 400 000 to develop a digital assistant, making it a cost effective tool. Operating a digital assistant also brings many benefits which makes it an even more attractive solution:

A lighter and smoother workload for staff, who can refocus on higher value-added activities.

Shorter processing times.

Increased traceability and reliability.

Lower material costs (toners, paper, storage, postage, etc.).

Harmonisation of practices and increased cross-services co-operation.

Optimised management of activity through the automated production of statistics and reports.

Ireland – Automation in software quality assurance and software deployment

As Revenue continues to enhance its IT services, it also enhances its software development and software quality assurance approaches. Traditional end of project testing is no longer suitable for the timely release cycles, especially in large and intricate systems. Building on the initial benefits from the use of electronic “record-and-playback” style repetition of manual tests, predominately for regression and end of cycle testing, Revenue has expanded its automation test capability to implement continuous API and functionality testing that would not otherwise be feasible.

Revenue has embedded test automation as a key enabler of its “shift left” approach which enables testing earlier in the cycle, improves the feedback loop to developers, reduces system delivery times, increases automated test coverage and improves software quality. By implementing the “shift left” ideology and agile approaches, Revenue is successfully using test automation to facilitate a broader range of concurrent and continuous testing to reduce delivery time and improve software quality assurance.

Mexico – Automation in the processing and management of incoming service requests

SAT has made investments in systems capable of processing complaints and emails, that utilise automated classification based on keywords. This technological advancement plays a crucial role in fulfilling the administration's core objectives of promoting voluntary, accurate and timely compliance. This system establishes mechanisms that facilitate voluntary compliance, providing taxpayers with tools that make the process easy while ensuring close monitoring.

By enhancing the complaint and investigation process, the system enables prompt follow-up on potential acts of corruption. This sends a strong message to taxpayers that their grievances are taken seriously, as they are quickly identified by the system. Moreover, it streamlines the efficient processing of service requests by swiftly directing them to the appropriate department within the institution. Consequently, this system significantly contributes to improving the public's perception of SAT.

Sources: Argentina (2023), Canada (2023), France (2023), Ireland (2023) and Mexico (2023).

Developing staff capability

While ISORA 2022 did not survey administrations as regards their strategy and approaches towards increasing staff capability, this remains a key topic for all administrations. This report highlights many areas of change that are taking place within administrations, and effective change relies on the capabilities of staff being developed. This is particularly important with digital transformation, as this frequently requires new skill sets. (See Chapter 10 for a more detailed discussion on this.)

In parallel, tax administrations report moving their training programmes into a virtual environment as shown in previous editions of this report, for example, using live online training sessions or pre-recorded videos/webinars (OECD, 2021[3]). While moving to a virtual training environment may have some up-front costs, it may save costs in the longer term as once produced, pre-recorded training material can be viewed at any time, from anywhere. Remote training can reduce travel expenses and can allow staff to learn at their own pace and convenience as well as increasing the number of staff members that can follow a course. New technologies are also helping facilitate the collaborative learning aspects, increasing the quality of the training experience. The latest approaches taken by the French tax administration are described in Box 9.7.

Box 9.7. France – E-learning solutions

In the DGFiP, improving staff skills increasingly relies on the development of e-learning solutions. The "mechanics" of e-learning obliges learners to be involved in their training journey and to measure how much the educational message has been understood. This has led to the four solutions outlined below:

A digital skills learning path is offered to all members of staff, which allows everyone to self-assess and progress over time in their mastery of digital tools.

A web app showcasing the DGFiP was created which offers an interactive and fun course lasting 10-15 minutes, designed to provide a uniform welcome message and a preliminary overview of the DGFiP to the roughly 5 000 new employees recruited every year. The web app is available to the general public (including on smartphones), which means it can also be used as a dynamic promotional tool in DGFiP’s recruitment efforts to bolster their attractiveness.

Another web app was developed to help staff members familiarise themselves with the main ethical and professional secrecy obligations of DGFiP employees. Staff follow the adventures of a "trouble agent" through five episodes before taking a final test. With this app, ethical obligations – a major subject that must be understood by all personnel in a tax administration – are approached in a clear and entertaining way.

Since October 2022, the initial training of DGFiP newcomers combines traditional physical classroom learning with remote sessions using a dedicated machine system learning platform during which the trainees learn independently.

See Annex 9.A for supporting material.

Source: France (2023).

References

[3] OECD (2021), Tax Administration 2021: Comparative Information on OECD and other Advanced and Emerging Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cef472b9-en.

[1] OECD (2021), Towards sustainable remote working in a post COVID-19 environment, https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/tax-administration-towards-sustainable-remote-working-in-a-post-covid-19-environment-fdc0844d/.

[2] OECD (2017), Tax Administration 2017: Comparative Information on OECD and Other Advanced and Emerging Economies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/tax_admin-2017-en.

Annex 9.A. Links to supporting material (accessed on 26 May 2023)

Box 9.1. – Chile: Link to a presentation on the automatic messaging system: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/database/b.9.1-chile-automatic-messaging-system.pdf

Box 9.3. – Australia: Link to an overview slide on the ATO’s System Integrity - Vulnerability Assessment Methodology: https://www.oecd.org/tax/forum-on-tax-administration/database/b.9.3-australia-system-integrity.pdf

Box 9.4. – Japan: Link to a website with more details on the new NTA’s job category “Science, Engineering, Digital”: https://www.nta.go.jp/about/recruitment/digital/index.htm

Box 9.7. – France: Link to the web app showcasing the DGFiP: https://bienvenuedgfip.veryup.pro/

Note

← 1. Previous editions reported the allocation of staff resources across seven functional groupings: (i) Registration and taxpayer services; (ii) Returns and payment processing; (iii) Audit, investigation and other verification; (iv) Debt collection; (v) Dispute and appeals; (vi) Information and communication technology; and (vii) Other functions. Starting with ISORA 2020 those seven groupings were reduced to the four groupings shown in Figure 9.5.