This chapter provides an overview of the tax reforms adopted by 71 member jurisdictions of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, including all OECD countries. It looks at the reforms that were announced and implemented in 2021, examining trends in each category of tax including personal income taxes and social security contributions, corporate income taxes and other corporate taxes, taxes on goods and services (including value added taxes, sales taxes, and excise duties), environmentally related taxes and property taxes.

Tax Policy Reforms 2022

3. Tax Policy Reforms

Abstract

This chapter provides an overview of the tax reforms adopted in the 71 Inclusive Framework jurisdictions that responded to the OECD’s annual tax policy reform questionnaire.1 It looks at the reforms that were introduced or announced in 2021. It examines trends in each category of tax including personal income taxes and social security contributions(Section 3.1), corporate income taxes and other corporate taxes (Section 3.2), taxes on goods and services, including value added taxes, sales taxes and excise duties (Section 3.3), environmentally related taxes (Section 3.4) and property taxes (Section 3.5).

The discussion in this chapter is primarily based on countries’ responses to the 2022 Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire, which was completed by countries between January and February 2022. This annual questionnaire asks responding countries to describe their tax reforms as well as to provide details on their expected revenue effects and other relevant information; including the rationale for the tax measures (see Box 3.1).

Country coverage varies across this Chapter. Differences in country coverage may be the result of variances between the categories of the reforms that countries reported on as well as the different data sources used.

Each Section of Chapter 3 starts with a short discussion of tax revenue trends within the five aforementioned tax categories, followed by descriptions of the tax reforms introduced or announced by countries. As in previous editions of the Tax Policy Reforms report, tax revenue data covers 43 countries – all 38 OECD countries as well as the five non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions of Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia and South Africa.2 As with Chapter 2, preliminary 2020 data were not available for these five non-OECD countries nor for some OECD countries (Australia and New Zealand for the most part, but also Greece and Japan for some tax categories) at the time of writing the report.

The tax policy trends sub-sections that follow cover the 71 member jurisdictions of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting that responded to the OECD questionnaire. Furthermore, the description of these tax reforms is often complemented by more detailed policy analysis using data from existing OECD publications. This may include effective tax rates on labour (Section 3.1), corporations (Section 3.2) or carbon (Section 3.4), for example, whose country coverage varies from the tax revenue and tax policy trends sub-Sections described above. All differences in country coverage are explained in the body of the report or in accompanying endnotes.

Box 3.1. The OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire

At the Working Party No.2 on Tax Policy Analysis and Tax Statistics (WP2) meeting in November 2009, delegates from OECD countries agreed to start collecting information on the main tax measures adopted in each country in a more systematic fashion. The motivation for this proposal was to provide consistent and comparative information on tax reforms to inform policy discussions in OECD and non-OECD countries.

At the November 2010 WP2 meeting, the following criteria were agreed for deciding whether a tax policy measure was sufficiently substantial to be reported in the questionnaire:

A significant change in a tax rate;

A change in the tax base that is expected to change revenue from that base by more than 5% of total tax revenue or 0.1% of GDP; and

A politically important systemic reform.

Any central or sub-central tax policy measure that was implemented, legislated, or announced in the previous calendar year that meets at least one of the criteria listed above must be reported in the questionnaire.

For each reform, the questionnaire requests information on the type of tax; the dates of entry into force, legislation, or announcement; the direction of the rate and/or base change; and a detailed description of the reform. The questionnaire also asks for the rationale behind the reform and estimates of the revenue effects of the tax measures.

3.1. Personal income tax and social security contributions

Countries continued to lower the tax burden of personal income taxes (PIT) and social security contributions (SSCs) in 2021 to support low-income households amid the COVID-19 pandemic and promote economic recovery. Most of the countries that responded to the OECD tax policy reforms questionnaire introduced PIT and SSC reforms in the tax year 2021, mostly through lowering tax rates and reducing the size of tax bases. The most common rationale behind these reforms was to boost economic growth, while, at the same time, promoting equity in personal income taxation, particularly for those on low and middle incomes. While the latter rationale represents a broad continuation of PIT reforms in recent years, the focus on economic growth has gained renewed importance in response to the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 crisis. PIT rate changes have been less common than in previous years, and mostly involved rate reductions for low- and middle-income households. PIT base narrowing measures have been frequent and often sought to promote employment and provide in work-benefits, as well as supporting families with children and particularly those on lower incomes. More limited changes in the taxation of household capital income were introduced. Finally, reforms to SSCs largely came in the form of SSC reductions in 2021, several of which involved temporary rate cuts and base narrowing measures in response to the adverse economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

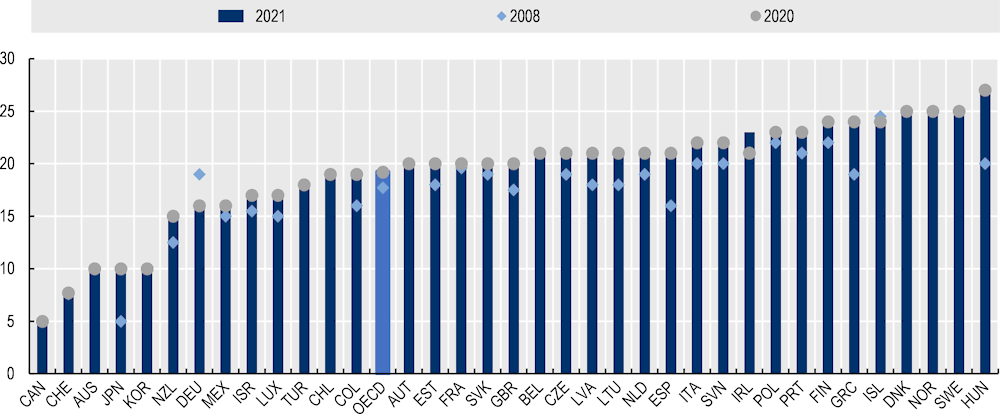

3.1.1. PIT and SSCs are major sources of tax revenue

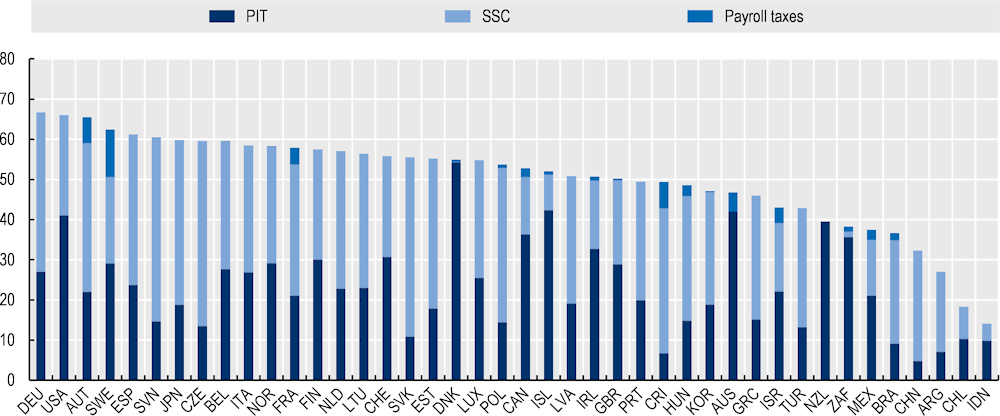

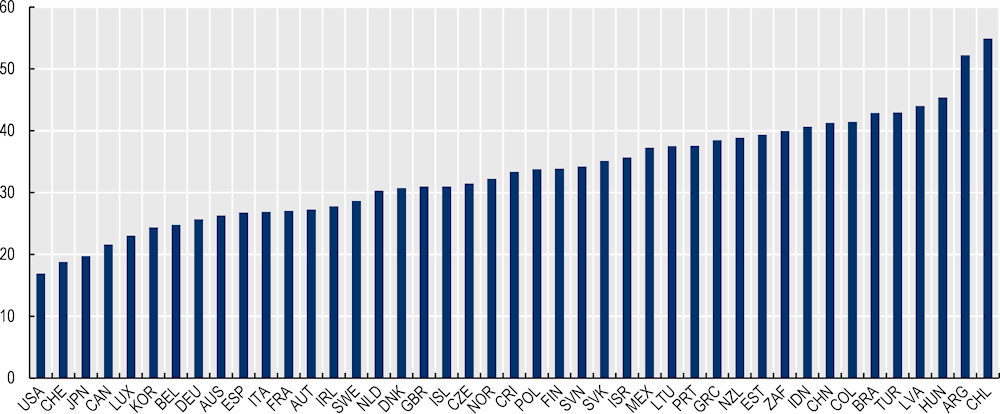

PIT and SSCs are significant sources of tax revenues in most countries. Together, they account for around half of total tax revenues, with PIT making up 23% and SSCs 26%, of total tax revenue on average across OECD countries and the five selected non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions (Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Africa). As shown in Figure 3.1, PIT, SSCs and payroll taxes accounted for over 60% of total tax revenue in Austria, Germany, Spain, Slovenia, Sweden, and the United States. In the Czech Republic, Japan, the Slovak Republic, and Slovenia, SSCs alone accounted for at least 40% of total tax revenues while PIT accounted for 40% or more of total tax revenues in Australia, Denmark, Iceland, and the United States. PIT, SSCs and payroll taxes represent a much smaller share of tax revenues in Argentina (27%), Chile (18%) and Indonesia (14%).

Figure 3.1. Tax revenue share of PIT, SSCs and payroll taxes by country, 2020

Note: 2019 data for Argentina, Australia, Brazil, China, Greece, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Africa. The OECD average includes the latest data available for OECD. The five additional Inclusive Framework jurisdictions included are Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia and South Africa.

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database, OECD Revenue Statistics Database.

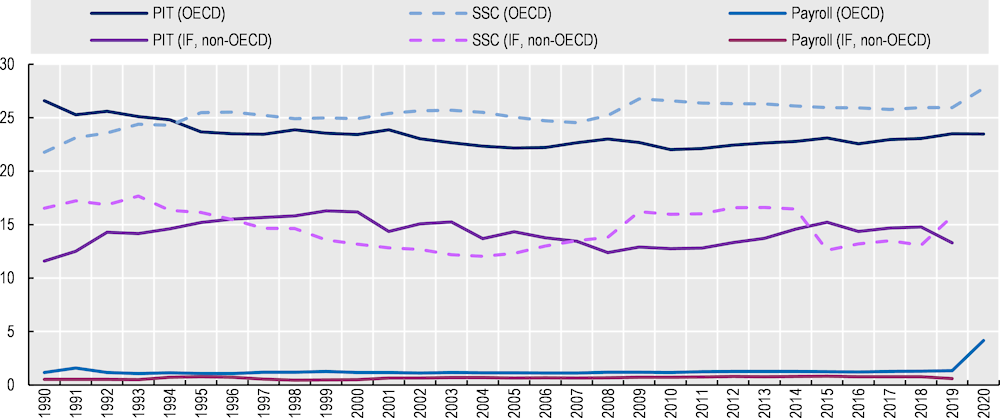

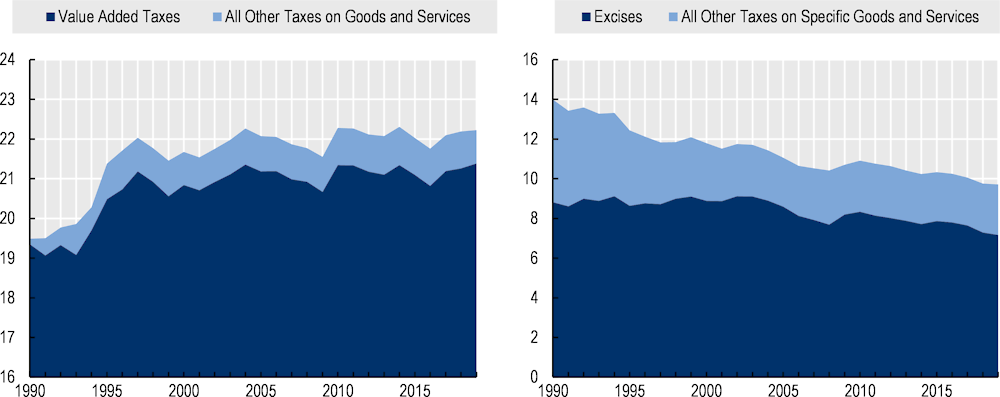

Over the past five decades, SSCs have gradually overtaken PIT as the most important source of tax revenue in OECD countries, while PIT and SSCs are more volatile and less significant as a share of total tax revenue in the selected non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions. In both OECD countries and non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions, the sum of PIT and SSCs has slightly increased over time, however, considerable differences remain in their respective tax mix (Figure 3.2). Across OECD countries, PIT has gradually declined as a share of total revenue while SSCs have increased. In 1965, SSCs comprised 17.6% of tax revenues on average while PIT accounted for 26.2% of total taxation. By 1995, they were about equal at approximately 25%. In 2020, SSCs represented 27.7% of total tax revenues on average, surpassing the PIT share of 23.5%. In the five non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions, PIT and SSCs accounted for a much smaller share of total tax revenues in 2019 (the latest year for which data is available for all countries covered), with 13.3% and 15.8%, respectively while their share in total tax revenues is also more volatile. The proportion of SSCs in the total tax mix increased significantly both in OECD countries and the non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, with a similar increase observed in OECD countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 3.2. Average tax revenue share of PIT, SSCs and payroll taxes in OECD and partner countries, 1990-2020

Note: The five additional Inclusive Framework jurisdictions included are Argentina, Brazil, China (People’s Republic of), Indonesia and South Africa. For Indonesia, data are included from 2002-2019; for China, data are included for 2019; for other Inclusive Framework jurisdictions, 2019 data are the latest available.

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database, OECD Revenue Statistics Database.

PIT and SSCs were increased in most OECD countries in 2020 following the COVID-19 pandemic, both in absolute terms and as a share of total tax revenue.3 In the 34 OECD countries for which provisional data were available for 2020, 19 countries recorded an increase and 15 countries a decrease in both nominal PIT and SSC revenues. As a share of total tax revenue, 27 countries saw their PIT revenue increase while seven countries recorded a fall. The share of SSCs in total tax revenues increased in 28 countries while it fell in six countries. In several countries, the relative PIT and SSC tax revenue decline was therefore smaller compared to the decrease in total tax revenues. On average across the 34 OECD countries for which data are available, the share of SSCs in total tax revenues increased by 1.8 p.p. in 2020 (from 25.9%) while the PIT revenue share remained stable at 23.5% compared to the previous year. These trends highlight the efforts of governments to promote job and income security in the face of the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 crisis.

3.1.2. Taxes on labour income continued to decline on average in 2020

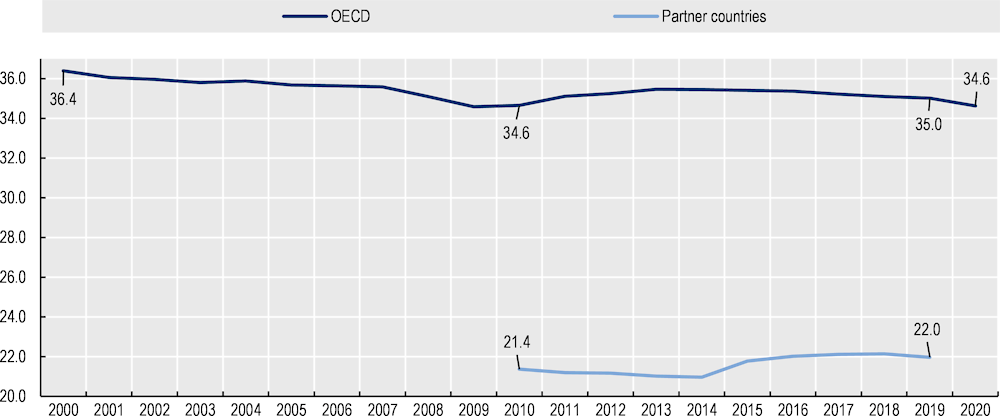

The average tax burden on labour income has declined in recent years in OECD countries while it has increased in the five selected non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions over the same time period (Figure 3.3). The average tax wedge – the total tax payments on labour income as a percentage of total labour costs – for single workers earning the average wage was 13 p.p. higher in OECD countries compared to partner countries in 2019, however, with considerable cross-country variation among the five non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions. In Brazil and China, the average tax wedge in 2019 was 32.5% and 30.7% respectively, close to the OECD average of 35.0%, while it was estimated at 16.9% in South Africa and 7.8% in Indonesia. Over time, the average tax wedge has declined from 36.4% in 2000 to 34.6% in 2020 in OECD countries while it increased marginally from 21.4% in 2010 to 22.0% in 2019 in the five non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions. The increase in the tax wedge between 2009 and 2013 in OECD economies largely reflects fiscal consolidation measures taken in response to the global financial crisis. Since then, the average tax wedge has declined consistently, with a particularly marked reduction of 0.39 p.p. between 2019 and 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between 2010 and 2019, the average tax wedge in the non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions increased consistently in Indonesia and South Africa, and remained relatively stable in Brazil, while it decreased continuously in China over the same observation period.

Figure 3.3. Evolution of the average tax wedge on labour income in OECD and selected non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions, 2000-2020

Note: Comparable data were not available for Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Africa. The non-OECD IF jurisdiction average includes data for Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Africa from 2010-2019; for China, the model assumes that the worker is based in Shanghai.

Source: OECD Taxing Wages Database, OECD (2021[1]).

The decrease in the tax burden for single earners without children earning the average wage has mainly been driven by lower income taxes. Between 2019 and 2020, the tax wedge fell in 29 out of 37 OECD member countries.4 For 21 out of the 29 OECD countries, the decrease in the average tax burden was predominantly driven by lower income taxes, linked to policy changes, including measures related to the COVID-19 pandemic, but also partially due to lower nominal average wages. In five OECD countries, the decrease in the average labour tax burden was mainly linked to lower SSCs (Finland, Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) while increases in Canada and the United States reflected the temporary cash transfers paid to single-worker households during the COVID-19 crisis who would not typically receive these types of benefits. In Iceland, the decline was driven equally by a reduction in income taxes and employer SSCs as a share of labour costs. In seven countries, the increase in the average tax burden has mainly been associated with growth in wages, which has seen workers on the average wage move into higher tax brackets (OECD, 2021[2]).

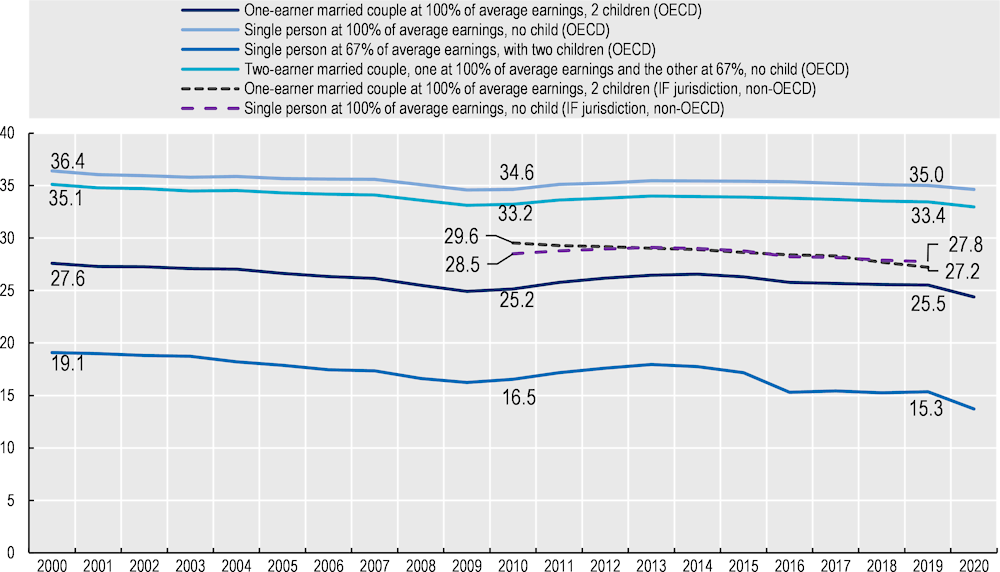

There are significant differences between the taxation of workers and families with and without children across Inclusive Framework jurisdictions (Figure 3.4). In OECD countries, the average tax wedge for a one-earner married couple with two children was 9.5 p.p. lower compared to a single person with no children in 2019. Across different family types, policy-related factors were the predominant driver of lower average tax burdens. Governments across the OECD relied mainly on enhanced or one-off cash benefits instead of support programmes granted within the labour tax system. A particular focus has been on families with children, which is reflected in the notable decline in their average tax burden.

Figure 3.4. Evolution of the average tax wedge in OECD and selected non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions, by family type, 2000-2020

Note: Comparable data were not available for Argentina, Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Africa. The partner country average includes data for Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Africa from 2010-2019; for China, the model assumes that the worker is based in Shanghai.

Source: OECD Taxing Wages Database; OECD (2021[1]).

3.1.3. Top PIT rate increases and PIT rate reductions for low- and middle-income households have raised the progressivity of tax systems

PIT reforms are important tools for governments to achieve different policy objectives, including raising tax revenues, stimulating economic growth, and enhancing the redistributive impact of the tax system. These reforms can involve the upward or downward adjustment of PIT rates and the broadening or narrowing of PIT bases but may require a trade-off between equity and efficiency. For instance, while PIT rate increases on those in the upper income brackets strengthen progressivity and fairness, in some cases they may also reduce economic incentives to work, save and invest. This section looks at the PIT reforms that were recently introduced in the 71 member jurisdictions of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting that responded to the OECD questionnaire, beginning with PIT rate reforms followed by PIT base changes.

Very few countries increased their top PIT rates in 2021 to raise the progressivity of their tax systems

Three countries undertook top PIT rate reforms, which involved rate increases (Table 3.1). Canada, New Zealand and Norway raised their top PIT rate through the introduction of new income tax brackets at the top of the PIT rate schedule. Norway introduced a fifth band for income over NOK 2 million (USD 232 829)5 effective from January 2022, which is taxed at a rate of 17.4%, and is paid in addition to the 22% general income tax rate (and the 8% SSC for employees). This reform represents a 1 p.p. net increase in the top PIT rate from 2020 and 2021 (employee SSCs were reduced by 0.2 p.p.). A tax rate of 16.4% will be applicable to the fourth income tax band from the beginning of 2022.6 The New Zealand government introduced a new top tax rate of 39% from April 2021 for individuals earning over NZD 180 000 (USD 128 570) per year. The previous top tax rate of 33%, which was applied to all income earned over NZD 70 000 (USD 50 000) up to March 2021, was subsequently applicable to earnings between NZD 70 000 and up to NZD 180 000. The Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador added three new income tax brackets on top of its existing five band structure. Effective from January 2022, income between CAD 250 000 (USD 199 380) and CAD 500 000 (USD 398 760) will be taxed at 20.8%, while earnings between CAD 500 000 and CAD 1 000 000 (USD 797 520) will be subject to a 21.3% tax rate. A tax rate of 21.8% will apply to income above CAD 1 000 000, representing a notable increase from the previous top PIT rate of 18.3% in 2021.7

Table 3.1. Changes to personal income tax rates

|

Rate increase |

Rate decrease |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

||

|

Top PIT rate |

CAN 1, NOR, NZL |

|

|

Non-top PIT rate |

ARM, AUT, ITA, LUX 2, MLT 2, POL |

|

Note : 1. Signifies that tax reform was implemented at the sub-central level (Province of Newfoundland and Labrador). 2. Signifies that PIT tax rate changes apply to income from temporary work.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

Countries continue to cut PIT rates for low and middle-income earners

More countries introduced non-top PIT rate reforms compared to top rate measures, many of which were comprised of rate cuts to support low and middle-income earners. Italy introduced a significant PIT reform (see Box 3.2), which included a reduction in the number of tax brackets from five to four as well as a reduction in PIT rates for the second- and third-income band. The rate for the second income band was cut from 27% to 25% while the rate for the third band was reduced from 38% to 35%. The fourth tax bracket was eliminated, which was previously composed of a tax rate of 41% applicable to taxable income between EUR 55 000 (USD 65 051) and EUR 75 000 (USD 88 706). The top PIT rate remained unchanged at 43% but applies now to taxable income above EUR 50 000 (USD 59 137) (IBFD, 2022[3]). Armenia reduced its flat PIT rate from 23% to 22% in January 2021. Austria will reduce the PIT rates that apply to the second and third tax bracket from 35% to 30% and 42% to 40%, respectively, with effect from July 2023.

Several countries introduced PIT rate reforms for part-time employment and other professional groups. Poland reformed the lump-sum tax rates for certain businesses on the registered revenues that apply to specific business activities. A flat rate of 14% is applied to income earned, for instance, by doctors and engineers, while the revenue of IT specialists will be taxed at a rate of 12% from 2022 onwards. Malta reduced the tax rate it applies for the first EUR 10 000 (USD 11 827) of income earned from part-time work from 15% to 10% – by decreasing the labour tax burden, the government hopes to partially address labour shortages in certain sectors. Luxembourg also introduced a reform to the taxation of income received by temporary workers. From 2022, income paid by temporary work agencies is taxed at a flat rate of 10% (tax applies on the gross wage after the deduction of social security contributions) if the hourly gross wage does not exceed EUR 25 (USD 30).

Box 3.2. Personal income tax reform in Italy

Italy announced several significant tax reforms in 2021, which aim at simplifying the tax system and promoting economic growth. These reforms are expected to reduce tax revenues by EUR 4.8 billion (USD 5.68 billion) in 2022 and around EUR 7 billion (USD 8.28 billion) in 2023 and 2024. The child benefit tax credit (ANF) and other benefits supporting children have been replaced by a universal child benefit (AUF). The main beneficiaries of the PIT reform are expected to be middle-income households.

Reform of the income tax schedule

The reforms included a reduction in income tax brackets from five to four as well as a reduction in the marginal tax rates for the second and third bracket (Table 3.2). The reform also redefined the third income tax band, lowering its upper threshold to EUR 50 000 (USD 59 137). The fourth income band was eliminated while the top income rate applies to all taxable income above EUR 50 000.

Table 3.2. Changes in tax bands and marginal PIT rates

|

2021 |

2022 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

Tax rate |

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

Tax rate |

|

0 |

15 000 |

23% |

0 |

15 000 |

23% |

|

15 001 |

28 000 |

27% |

15 001 |

28 000 |

25% |

|

28 001 |

55 000 |

38% |

28 001 |

50 000 |

35% |

|

55 001 |

75 000 |

41% |

50 001 |

43% |

|

|

>75 000 |

43% |

||||

Note: Amounts in EUR.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

Changes to allowances and tax credits

Italy also revised the structure of its tax credit system for employment, self-employment, and pension income. Tax credits were generally increased for lower- and middle-income earners while tax credits for higher income earners were reduced. The upper income threshold (i.e., income for which tax credits are reduced to zero) was lowered from EUR 55 000 (USD 65 050) to EUR 50 000.

Reform of the child tax credit

The PIT reform also replaced the child benefit tax credit and other benefits (e.g., child allowance) with a single, universal allowance (“assegno unico e universale”), which will become effective as of March 2022. The allowance includes a monthly cash-transfer, the amount of which is based on the economic situation of the household and calculated with the help of the Equivalent Economic Situation Indicator (“Indicatore della Situazione Economica Equivalente”). Parents with children under the age of 21 are eligible to receive the benefit. The universal allowance is generally more generous compared to previous arrangements, though it depends on the individual economic situation of the household. Notably, it also benefits households on low incomes who are not liable to PIT (which were previously excluded).

3.1.4. Reforms narrowing PIT bases have continued in 2021

Many countries have continued to narrow their PIT bases. Overall, these measures are expected to reduce tax revenues. Of the countries undertaking PIT base reforms, 57 were base narrowing and nine were base broadening measures (Table 3.3), which generally follows trends observed in recent years. Most PIT base reforms introduced in 2021 or later were aimed at supporting individuals and families on low incomes who were often particularly hard hit by the economic impact of the pandemic. Several reforms also sought to reduce the tax burden on middle-income households with the intention of increasing household consumption and promoting economic recovery. Thirteen reforms involved increases in personal tax allowances, tax credits and tax brackets to support low-income earners and employment, while nine reforms were aimed at supporting children and other dependents. PIT base reforms also aimed at supporting the elderly, particularly those on low incomes. Five countries expanded the scope of their earned income tax credit (EITC) and other in-work benefits. Promoting economic recovery while alleviating the tax burden on low-and medium-income households was the predominant rationale behind many base narrowing tax provisions.

Table 3.3. Changes to personal income tax bases

|

Base broadening |

Base narrowing |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

||

|

Personal allowances, credits, tax brackets |

ITA, NOR, GBR 2, URY 1,2 |

ALB, BRA, CAN, CZE, FIN, IRL, ITA, LTU, LVA, NOR, POL, SWE, ZAF |

|

Provisions targeted at low-income earners, EITCs and other in-work benefits |

CAN, FIN, ITA, SWE 1, USA |

|

|

Self-employed and unincorporated business |

AUT, DEU, POL, MEX, TUR |

|

|

Children and other dependents |

||

|

Elderly & disabled |

CAN, MLT, POL, SWE |

|

|

Employment |

BEL, NLD, SWE |

AUS, AUT, BEL, CAN, DEU, HUN, IRL, NLD, NOR |

|

Environmental sustainability |

||

|

Miscellaneous expenses, deductions, and credits |

ESP, NOR |

AUS, CAN, DEU, HUN, KOR LVA, SWE |

Note: Temporary COVID-19 response measures are not included in the table.

1. Denotes a temporary PIT reform.

2. Denotes a new tax.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

Many countries increased the generosity of their general PIT allowances and credits

In nine countries the basic tax allowance was increased to reduce the PIT burden and support the progressivity of the tax system. Increases were introduced in seven OECD and two non-OECD Inclusive Framework jurisdictions. In Poland, the basic allowance will be raised almost four-fold from PLN 8 000 (USD 2 072) to PLN 30 000 (USD 7 768), from 2022 onwards. Lithuania has indicated that it will increase its basic allowance from EUR 4 800 (USD 5677) to EUR 5 520 (USD 6529) from 2022 for people earning below the national average wage. For taxpayers whose income exceeds the national average wage the tax-free threshold of EUR 4 800 (USD 5677) continues to apply (IBFD, 2021[5]). Latvia increased its monthly basic allowance from EUR 300 (USD 355) to EUR 350 (USD 414) as from January 2022 onwards, while a further increase to EUR 500 (USD 591) will apply from July 2022 onwards. Norway increased its basic allowance from NOK 52 450 (USD 6 106) to NOK 58 250 (USD 6 781), ensuring that the allowance increased more than average growth in wages (KPMG, 2021[6]). In Finland, the basic allowance for municipal tax purposes was raised to EUR 3 740 (USD 4 423) from EUR 3 630 (USD 4 293). Brazil raised its monthly income tax-exempt threshold from BRL 1 904 (USD 35) to BRL 2 500 (USD 463) (IBFD, 2021[7]). In Albania, the basic allowance was increased from ALL 30 000 (USD 290) to ALL 40 000 (USD 386) as from 2022 onwards. In Prince Edward Island, Canada, the personal income tax exemption level was raised from CAD 10 500 (USD 8 374) to CAD 11 250 (USD 8 972) with effect in 2022.

In Canada, the Czech Republic and Ireland, general tax credits were expanded. Ireland announced that it will increase its Personal Tax Credit from EUR 1 650 (USD 1 952) to EUR 1 700 (USD 2 011) from 2022. The Canadian province of Prince Edward Island increased its low-income tax credit threshold from CAD 19 000 (USD 15 153) to CAD 20 000 (USD 15 951), for a tax credit of up to CAD 350 (USD 279) per person (with additional claims possible for those with a spouse and children), effective from 2022.

Tax brackets were shifted upwards in several countries in 2021. Ireland increased standard rate bands for all earners by EUR 1 500 (USD 1 774) from 35 300 (USD 41 750) to EUR 36 800 (USD 43 525) for single individuals and from EUR 44 300 (USD 52 395) to EUR 45 800 (USD 54 170) for married couples and civil partners with one earner. A tax rate of 20% applies below the threshold while a rate of 40% is levied above the threshold. Iceland introduced an annual adjustment factor applied to the tax-free threshold and tax brackets, which is determined by the yearly change in the Consumer Price Index plus a one percentage point increase to account for annual rises in productivity. Poland revised its band threshold upwards from PLN 85 528 (USD 22 147) to PLN 120 000 (USD 31 073) and from January 2022, income above PLN 120 000 will be taxed at a rate of 32% while income below is taxed at a rate of 12%. Albania increased the base of its second tax bracket, with the top PIT rate applying from ALL 200 000 (USD 1 930), up from ALL 150 000 (USD 1 450). Finland raised the thresholds for all its income tax brackets by EUR 1 100 (USD 1 300). The adjustments account for the general increase in the earnings level and is aimed at supporting sustained household purchasing power. Tax bands in South Africa were also adjusted upwards to account for inflation.

Several countries introduced PIT measures aimed at supporting particularly lower income households with children as well as promoting the compatibility of work and family life.

Several countries introduced PIT measures aimed at supporting families and children. In Austria, the child tax credit will be raised from EUR 1 500 (USD 1 774) to EUR 2 000 (USD 2 365) per child under the age of 18 from July 2022. Moreover, the child tax refund for single-earner and single-parent households was raised to EUR 350 (USD 414) (EUR 450 (532 USD) from 2023 onwards) and extended to people in partnerships. The Czech Republic increased the child tax credit from CZK 19 404 (USD 895) to CZK 22 320 (USD 1 030) for the second child and from CZK 24 204 (USD 1 117) to CZK 27 840 (USD 1 284) from the third child, taking effect retrospectively from January 2021. Poland introduced an additional tax relief for families with four or more children, which exempts income from certain sources (i.e., labour) from personal income tax up to PLN 85 528 (USD 22 146). In Canada, several measures were introduced throughout 2021 to support families and children. The province of Quebec enhanced the refundable tax credit for childcare expenses to align the costs of non-subsidised childcare services with the cost of subsidised services. The province of Newfoundland and Labrador introduced a Physical Activity Tax Credit, which provides a tax credit of up to CAD 2 000 (USD 1 595) per family for expenses related to physical activities, including for instance sport club registration or membership fees.

Several PIT measures were also aimed at reducing disincentives for second earners to participate in the labour market and at reconciling work and family life. Tax policies can play an important role in promoting gender equity and reducing income and wealth inequalities more broadly (Box 3.3). Italy introduced a major reform unifying its former child benefit tax credit and other minor benefits into one single, universal allowance (Box 3.2), with the explicit aim to strengthen second earner labour market participation. In Switzerland, deductions for external childcare for federal income tax purposes were increased from CHF 10 100 (USD 11 052) to CHF 25 000 (USD 27 357) in 2022. Finland raised the maximum tax credit for household expenses on domestic and care work in a two-year trial to assess the potential employment effects.

Box 3.3. Gender and taxation

Promoting gender equality, as reflected in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals, is a human rights objective for many governments, including in G20 and OECD countries (OECD, 2022[8]). Improving gender equality is not only an issue of fairness but can also produce a significant economic dividend. Working towards more inclusive economies in which women participate fully is important for economic growth and, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, will be crucial in ensuring an inclusive and robust recovery. Research shows that improving gender equality and reducing gender-based discrimination can generate substantial economic benefits, by increasing the stock of human capital, making labour and product markets more competitive, and increasing productivity.

Tax policy can contribute to gender equality and to governments’ efforts to reduce inequalities. A growing body of research shows that even in tax systems that do not include explicit gender biases, other implicit biases exist due to the interaction of the tax system with differences in the nature and level of income earned by men and women, consumption decisions, the ownership of property and wealth, and the impact of different social expectations on male and female taxpayers.

Against this background, governments can act to improve the gender outcomes of taxation; removing overt biases and reconsidering tax settings that currently result in implicit gender biases; and evaluating avenues within the tax system to design and implement tax policy that promotes gender equality.

The first analysis of its kind

The report Tax Policy and Gender Equality: A Stocktake of Country Approaches (OECD, 2022[8]) is the first cross-country report to analyse national approaches to tax policy and gender outcomes, including assessments of explicit and implicit biases, tax policy reforms to improve gender equity, and policy processes and priorities. Covering 43 countries from the G20, the OECD and beyond, the report was prepared as part of the OECD’s efforts to mainstream gender equality under the Indonesian G20 Presidency.

The report focuses on various aspects of tax policy design and implementation, on a cross-country basis. It explores the extent to which countries consider gender equality in tax policy development and tax administration, how they address explicit and implicit gender biases in their tax systems, and the availability and use of gender-disaggregated data. It analyses country perspectives on how and to what extent gender should be considered in the tax policy development process (including via gender budgeting). It also takes stock of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality in the tax system and highlights how countries consider gender outcomes in their tax responses to the pandemic.

Key findings and country priorities

The report finds that gender equality is an important consideration in tax policy design for most countries, and that about half of them have already implemented specific tax reforms to improve gender equity, most commonly in the taxation of personal income.

Although few countries noted examples of explicit bias in their tax system, more than half of the countries indicated that there was a risk of implicit bias. As with explicit biases, these implicit biases can either exacerbate or reduce gender inequalities already present in society and the examples noted by countries suggest a more nuanced policy response to gender bias in taxation is needed.

Most countries have access to gender-differentiated data for policy analysis, but access to data is concentrated on male and female incomes and labour market participation. Detailed data on consumption and on property and wealth ownership is less commonly available and was identified by several countries as a key data gap.

Finally, countries indicated that aspects of labour taxation were the key priority for future work to improve tax systems to increase gender equality. Identified policy areas include the impact of tax credits and allowances on gender equality, the taxation of second earners, the relationship between the progressivity of the tax system and gender equality, and the impact of social security contributions. A secondary priority is work on identifying the policy rationales and an assessment framework for considering the use of explicit biases to reduce gender inequality. Another common priority is exploring gender bias in the taxation of capital income and capital gains, notably in wealth and inheritance taxes.

Source: OECD (2022[8]).

Several countries significantly increased the generosity of their Earned Income Tax Credits and other in-work tax benefits

More countries introduced reforms to Earned Income Tax Credits (EITCs) and other in-work benefits compared to previous years. In-work benefit programmes typically involve tax reductions or cash transfers, which are conditional on labour market participation. The value of EITCs commonly depends on the recipient’s earned income. Typically, the value of the credit increases gradually with income (phase-in) until it reaches the maximum credit amount (plateau). Beyond a certain earned income threshold (the phase-out threshold), the value of the credit is gradually reduced to zero. Programmes are typically means-tested and may be targeted at specific groups. When designed correctly, such measures have the potential to improve labour market participation and reduce poverty.

Canada, Finland, Italy, and the United States increased in-work tax credits to promote work incentives and provide financial support for low-income households. The United States raised the maximum credit amount for workers without qualifying children from USD 538 to USD 1 502. Moreover, certain eligibility criteria have been relaxed, including for instance limits on investment income, the allowance that applies to separated spouses claiming EITCs and for taxpayers with qualifying children who fail to meet certain identification requirements (IRS, 2022[9]). In Canada, the federal government increased its in-work tax credit by raising phase-in rates and phase-out thresholds, while also increasing phase-out rates. Finland increased its maximum earned income tax credit to EUR 1 930 (USD 2 283) from EUR 1 840 (USD 2 176) and raised its phase-in and phase-out rates. Italy reformed the structure of its earned income tax credit, generally increasing tax credits for low-income and medium-income taxpayers (Box 3.2).

A few countries introduced PIT base reforms for the self-employed and unincorporated businesses.

Austria, Poland and Türkiye reported PIT base reforms for the self-employed and unincorporated businesses, which generally reduced their tax burdens. In Austria, the percentage of profits that partnerships and the self-employed can claim as tax exempt was raised from 13% to 15% with effect from 2023 – this basic tax-free allowance can be claimed only on profits up to a value of EUR 30 000 (USD 35 482), i.e., a maximum EUR 3 900 (USD 4 615). Austria also introduced several new tax credits for investments. Poland enhanced PIT reliefs to support research and development (in parallel with changes to its CIT), including for instance an increase (of up to 200%) in the deduction of qualified costs for R&D centres and an increase (of up to 200%) in the deduction of qualified costs related to employing staff conducting R&D for all taxpayers. Poland also introduced a robotisation relief that allows for an additional deduction of up to 50% of eligible costs related to robotisation. Türkiye introduced a provision whereby social content creators (e.g. influencers) and app developers are subject to a 15% withholding tax (and not the personal income tax) if their earnings do not exceed the amount specified in the fourth income segment of the personal income tax return (IBFD, 2021[10]). Taxpayers previously liable to small business taxation were also exempt from income tax.

Several countries provided support for the elderly through their PIT regime

Malta, Poland, and Sweden introduced PIT measures to support the elderly, some of which also incentivise pensioners to stay active in the labour market. Supporting low-income older people continues to be an important policy rationale for age-related tax concessions. Latvia increased the monthly basic allowance for pensioners from EUR 300 (USD 355) to EUR 330 (USD 390) in January 2021, with a further raise to EUR 500 (USD 591) taking effect from July 2022 onwards. Similarly, Sweden increased the basic allowance for elderly people in 2022. In Estonia, the basic allowance for pensioners will be raised to the same level as the average-old age pension in 2023, making average old age pensions tax exempt. In Malta, pension income will no longer be counted as part of the PIT base between 2022 and 2026. This measure is intended to encourage pensioners to remain active in the labour market after reaching the age at which they can receive their pension. Poland also introduced a personal income tax exemption (up to PLN 85 528 (USD 22 146)) for people who continue working after reaching the statutory retirement age and do not take their retirement pension.

In Canada, PIT measures introduced for the elderly involved tax credits for care services and home improvements. The Canadian province of Quebec enhanced the refundable senior assistance tax credit targeting low-income seniors starting in 2021 and increased the generosity of the refundable tax credit for home-support services for seniors, effective from 2022. Ontario extended the temporary seniors’ Home Safety Tax Credit for the tax year 2022, for renovations that improve safety and accessibility or help elderly people to be more functional or mobile at home.

Several countries have sought to facilitate employment in a changing work environment through employment-related tax provisions

Countries are supporting employers and employees to manage changing work environments and the transition to increased working-from-home. Ireland started allowing for the deduction of heat, electricity, and broadband expenses for home office days from 2022 onwards. In the Netherlands, employers may pay a tax-free “working from home” allowance of EUR 2 per day (USD 2.37). To simplify the regulation of temporary employment, Sweden reformed its rules governing the place of employment and temporary work, with expenses for temporary work and assignments in a different location now being tax deductible if the assignment lasts less than one month and the distance between the workplace and home is more than 50 kilometres. Germany allows taxpayers to fully depreciate computer hardware and standard business software in the year of acquisition instead of over a three-year period, taking effect from January 2021, retroactively. Austria introduced a non-taxable expense compensation for working from home of up to EUR 3 (USD 4) per day for a maximum of 100 days within a tax year, which will be in place until December 2023. Similarly, Canada simplified the rules for deducting home office expenses and increased the temporary flat rate to CAD 500 (USD 399) for the tax years 2021 and 2022 tax year.

Several countries reformed the tax provisions of employee share schemes. For employee share schemes in Australia, the termination of employment is no longer considered a taxable point, which aims at increasing the attractiveness of employee share plans. Germany clarified the tax rules that apply to shares and options that workers receive as part of their remuneration as employees of start-ups and SMEs. Germany also increased the income tax exemption threshold for employee share plans from EUR 360 (USD 426) to EUR 1 440 (USD 1 703) from July 2021. Norway, on the other hand, abolished the tax-free benefit for employees buying shares at a discount in the company they work in. Thereby, the benefit from the purchase of the shares (at a discount) is included in the tax base. At the same time, Norway also introduced a more favourable scheme for the taxation of options in start-ups, which is aimed at attracting talent and promoting entrepreneurship. Sweden reformed the eligibility criteria for the beneficial tax treatment of employee stock options (qualified employee stock options), which includes for instance a deferral of personal income taxes for the employee and social security contributions for the employer until the point of sale of the shares. From January 2022, these rules also apply to larger companies and board members (Baker McKenzie, 2022[11]).

Hungary introduced favourable tax provisions for young workers. From January 2022, Hungary exempts taxpayers below the age of 25 from PIT if their income falls below the average gross wage for a full-time employee in July of the preceding year. The reform is intended to increase employment of younger people and promote their financial independence (European Social Policy Network, 2021[12]).

Sweden introduced tax relief measures related to pensions, unemployment insurance and other work-related benefits. From July 2022, Sweden will increase the tax reduction for pension and social insurance benefits, including, for instance, sickness compensation. The tax reduction is greater for low incomes and falls as income increases up to a maximum of SEK 1 500 (USD 175). Sweden also introduced tax relief for unemployment insurance contributions, aimed at increasing insurance coverage.

PIT provisions encouraging environmental sustainability have become more common

Several countries have granted or expanded tax incentives for home renovations to support the environmental transition towards net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Italy introduced and extended multiple tax credits for sustainable building renovations aimed at, for instance, increasing buildings’ energy efficiency and seismic resilience. Finland temporarily increased the tax credit for household expenses to a maximum of EUR 3 500 (USD 4 140) (from EUR 2 250 (USD 2 661) for households moving from oil heating to more sustainable energy sources between 2022 and 2027.

PIT measures related to environmental sustainability also involved tax incentives for carbon-efficient transportation. Between 2021 and 2025, Belgium will grant a tax deduction of up to EUR 675 (USD 798) (this amount is reduced over the five-year period) for taxpayers installing an electric charging station in their homes. Malaysia announced that it will introduce a relief for expenses related to the purchase, rental, and related installation costs of electric vehicles of up to MYR 2 500 (USD 604) per tax year in 2022 and 2023. Finland granted tax provisions for hybrid vehicles and Sweden for low-emission vehicles and bicycles provided as an in-kind benefit by employers.

Several temporary PIT measures were introduced or extended in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Some countries continued to provide temporary PIT tax relief to encourage employment. Sweden introduced a temporary in-work tax credit for 2021 and 2022, which intends to support middle-income households. For incomes between SEK 60 000 (USD 6 996) and SEK 240 000 (USD 27 983), the tax credit increases to a maximum amount of SEK 2 250 (USD 262). The credit is then phased out for incomes between SEK 300 000 (USD 34 979) and SEK 500 000 (USD 58 298) (Sveriges Riksdag, 2021[13]).

Countries also introduced a wide range of other measures aimed at supporting households and businesses. Germany introduced an exemption for bonuses of up to EUR 1 500 (USD 1 774) paid to employees during the COVID-19 pandemic (between March 2020 and March 2022). The government also prolonged tax deferrals and simplified procedures to reduce pre-payments for the self-employed. In Greece, private sector employees will be exempt from special solidarity surcharge for the tax year 2022. Latvia extended the deferral of personal income tax advance payments for the self-employed. Viet Nam exempted individuals and households located in areas affected by the COVID-19 pandemic from personal income tax and other taxes on income for the second and fourth quarter of 2021 (IBFD, 2021[14]). Australia exempted individual assistance support payments from the PIT base. Chile and Cabo Verde extended the deadlines for income tax return filing in 2022. Malaysia extended and increased several tax credits, including for instance for fees of self-study courses, medical expenses, and costs for childcare services. The province of Ontario, Canada, introduced a temporary Staycation Tax Credit for the 2022 tax year, for eligible accommodation expenses paid for by Ontario residents, which would also help the tourism and hospitality sectors. Quebec introduced a one-time cost of living allowance of CAD 200 (USD 160) per adult for eligible households. Korea introduced a temporary five percentage point rise in tax credits for donations made during 2021 to promote charitable giving.

Several countries continue to provide PIT relief to support families, particularly for those on low incomes. Hungary refunded PIT payments for families with children for the tax year 2021, capped at tax payments for income at the average annual wage. Ontario introduced a one-off 20% increase in the refundable income-tested tax credit that provides families with childcare support. Bulgaria introduced a temporary child tax relief granting a deduction of BGN 4 500 (USD 2 721) per child (up from BGN 200 (USD 121)) for the tax years 2021 and 2022 to support the income of families.

3.1.5. A few countries introduced measures which broadened PIT bases

Both Italy and Norway decreased their tax band thresholds for higher income earners while the Netherlands will abolish the possibility to average taxable income. Norway reduced the lower thresholds for its third and fourth bracket and adjusted the first and second tax brackets in line with average wage growth. A new top tax band was also added for income above NOK 2 000 000 (USD 232 828). Italy also reduced the tax band threshold for the fourth tax bracket from EUR 55 000 (USD 65 051) to EUR 50 000 (USD 59 137). With effect in 2023, the Netherlands will abolish the averaging scheme, which allowed taxpayers with significant income fluctuations to average their income over three consecutive years. The reform aims at simplifying the tax system and increasing tax compliance.

Spain and Norway amended the tax treatment of pension and welfare contributions while the Netherlands reformed PIT tax support for families. Spain lowered the maximum amount of annual contributions to qualifying pension plans that taxpayers can deduct from their net taxable income from EUR 2 000 (USD 2 365) to EUR 1 500 (USD 1 774), taking effect in 2022. Similarly, Norway amended the tax treatment of pension accounts, reducing the maximum tax-favoured amount of savings in individual pension accounts from NOK 40 000 (USD 4 657) to NOK 15 000 (USD 1 746). The reform will come into effect in January 2022 and is aimed at raising revenue and efficiency in the tax system. The Netherlands reduced the maximum income dependent combination tax credit by EUR 395 (USD 467), with the aim to partially fund free childcare. The tax credit, which is provided at a rate of 11.45% of taxable income, is aimed at supporting working single parents or the partner in a family with the lower income, conditional on children being below the age of 12 and the taxable income from employment exceeding EUR 4 993 (USD 6 240) (OECD, 2020[15]).

Other tax base broadening measures affected the highly skilled labour force in Belgium and the self-employed in the Netherlands. Belgium reformed its legal framework on the tax treatment of foreign (non-Belgian national or citizen) executives and researchers working for Belgian companies or entities with the intention of providing more legal certainty to expatriates and limiting the maximum duration of the special tax treatment regime to five years (this was previously indefinite). The regime allows taxpayers, subject to several eligibility criteria, to be considered as non-resident for income tax purposes and therefore to only be taxed on Belgian income sources, while living in Belgium and maintaining the centre of economic and personal activities (e.g., contribution to pension plans, real estate ownership) in another country. In the Netherlands, the tax deduction for the unincorporated self-employed will be gradually phased-out until 2030, by EUR 650 (USD 769) per year, from EUR 6 310 (USD 7 463) in 2022.

The United Kingdom and Uruguay introduced temporary PIT measures, which broadened the tax base and sought to address the increased funding needs following the COVID-19 pandemic. The United Kingdom has frozen the Income Tax Personal Allowance and the Basic Rate Limit (i.e., income tax band liable to a 20% tax rate) for a four-year period at 2021-22 levels. Uruguay introduced a temporary income tax to fund measures mitigating the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (IBFD, 2021[16]). Between May and June 2020, a temporary income tax was implemented, similar to a measure passed in 2020 to finance an emergency COVID-19 solidarity fund, which applied a progressive tax to income derived from employment in the public sector (exempting employees working in the healthcare sector), and from pension income. The applicable tax rate was determined by a five-band income tax rate schedule, with rates between 0% (for income below UYU 120 000 (USD 2 755)) and 20% (for income over UYU 180 000 (USD 4 133)).

3.1.6. Changes to personal capital income taxation have been limited

There were two countries reporting changes to their capital income tax rates, while eight countries introduced changes to their capital income tax bases. Changes in tax rates involved rate increases, both of which were aimed at strengthening the neutrality between different economic and investment activities. Tax base broadening measures were predominantly introduced in the area of capital gains taxes while some countries also introduced changes to the taxation of interest income, pensions, and other types of capital income.

The Netherlands announced a reform of the capital income tax system. Following a ruling by the Dutch Supreme Court (“Hoge Raad der Nederlanden”) in December 2021, which deemed the taxation of income from savings and investments based on presumptive returns incompatible with the European Convention on Human Rights, the government announced that it would revise the current tax method (IBFD, 2022[17]). In the Netherlands, income-producing assets are assigned an assumed yield, which increases with the size of the asset base, regardless of the actual gain or loss of the respective asset. The capital income is then taxed at a rate of 31%. With the implementation of the tax reform, capital income taxation will be based on actual returns from 2025, abolishing the current system. During the transition period, the exemption threshold (applied to the asset base) will be raised from EUR 50 650 (USD 59 906) in 2022 to EUR 80 000 (USD 94 619) in 2023. As part of the reform, the method to estimate the economic value of rental property will also be revised to broaden the tax base.

Brazil and Norway increased the tax rates on certain capital income, to promote neutrality in the tax system. As part of a comprehensive income tax reform, Brazil revised the taxation of income earned in financial markets – for example, gains from stock exchange transactions and income from investment funds – to simplify the tax system and strengthen the neutrality between different types of investments. A key component of the reform was the introduction of a 15% withholding tax on dividend distribution (which previously went untaxed) (IBFD, 2021[7]). Norway also increased the tax rate on dividends to reduce the difference in marginal tax rates between shareholder income and wages, and thereby reduce the incentives for income shifting. In Norway, the ordinary yield of dividends is taxed at the company level while gains above the ordinary yield are taxed at the shareholder level at a flat rate of 22% multiplied by the adjustment factor. The reform raised the adjustment factor from 1.44 to 1.6, increasing the effective dividend tax rate from 31.68% (100 x 22% x 1.44) to 35.2% (100 x 22% x 1.6) (IBFD, 2021[18]).

Table 3.4. Changes to tax rates on personal capital income

|

Rate increase |

Rate decrease |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

2021 or later |

|

|

Dividend or interest income/equity or bond investment |

BRA, NOR |

Note: No tax rate changes were implemented in the area of capital gains, rental income, employee share acquisition deductions and the tax treatment of pensions and savings account.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

Capital tax base broadening measures were introduced in Nigeria, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. New Zealand introduced several base broadening reforms with the aim of reducing investors’ demand for existing residential property and thereby improving housing market accessibility. The deductibility of mortgage interest on debt to purchase rental residential property will be phased out between October 2021 and March 2025. The government also extended the bright-line test, by which realised gains from the sale of residential property within ten years of its acquisition are subject to income tax. While New Zealand does not apply a tax on capital gains, the bright-line test effectively allows the taxation of gains on residential property (with certain exemptions for newly constructed buildings). Nigeria broadened its capital income tax base by removing certain tax exemptions on sales of shares. From January 2022, a 10% capital gains tax is applied to gains from the sale of shares above a threshold of NGN 100 million (USD 278 700)8 generated in any 12 consecutive months. The capital gains tax does not apply if the proceeds of the sale are reinvested in shares in the same or another Nigerian company within the same tax year. In the United Kingdom, the maximum lifetime allowance for pension contributions (the limit at which the tax benefits of pensions can be maintained) will be kept at its nominal level of GBP 1 073 100 (USD 1 475 934) (its 2021-22 level) until the tax year 2025-2026. Given inflation expectations, an unchanged nominal limit amounts to a decline in real terms and hence a broadening of the capital tax base of pension income.

Austria and Hungary also broadened their tax bases by introducing taxes on income from crypto currencies. The taxation of income derived from crypto has become a growing area of policy focus (see Box 3.12), with current capital income tax reforms aiming predominantly at promoting neutrality between crypto and other asset classes while also raising tax revenue. Hungary introduced a 15% flat tax on income generated from some crypto currency transactions (equivalent to the 15% capital gains tax). A taxable event is triggered if the asset leaves the digital space when realised or if crypto assets are exchanged in a standard currency or for any other good. The costs related to the crypto transaction and acquisition are deductible from the tax base, while income from crypto mining or exchanges of crypto assets are not included in the tax base (IBFD, 2021[19]). Austria also introduced a tax on income from crypto transactions by which income derived from crypto currency sales is subject to a flat rate of 27.5% (equivalent to the capital gains tax rates). Income from crypto currencies includes the current income generated from crypto currencies as well as income derived from increases in realised values (IBFD, 2021[20]).The tax applies from March 2022 onwards for all sales of crypto currency after February 2021. Given the growing importance of crypto currency taxation, the OECD is also developing a global tax transparency framework, to facilitate the automatic exchange of tax information on transactions in crypto-assets in a standardised manner (see OECD (2022[21])).

Belgium, Bulgaria, and Malta introduced measures in 2021 that have narrowed their capital tax bases. Bulgaria abolished the taxation of interest income on bank deposits (and their branches), where banks are established in an EU Member State or in another State that is party to the Agreement within the European Economic Area. The reform responded to the continuing decline in interest rates on bank deposits in recent years, with corresponding declines in tax revenue. In this context, the administrative burden on banks and taxpayers was deemed disproportionate to the revenue potential of the tax. To promote the growth of start-ups, Belgium doubled the share capital eligible to the tax shelter regulation from EUR 250 000 (USD 295 685) to EUR 500 000 (USD 591 370) and from EUR 500 000 to EUR 1 million (USD 1.25 million) for companies carrying out activities in markets with growth potential. The tax shelter regulation for start-ups provides a tax reduction for private investors on a share of their investment in a start-up (between 25% and 45% of the invested amount). Malta introduced a capital gains tax exemption for the first EUR 750 000 (USD 937 500) of the property transfer value for certain properties subject to eligibility criteria.

Table 3.5. Changes to personal capital income tax bases

|

Base broadening |

Base narrowing |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

2021 or later |

|

|

Dividend or interest income/equity or bond investment |

NZL |

BGR, BEL |

|

Capital gains |

AUT, HUN, NGA, NZL |

MLT |

|

Rental income |

||

|

Tax treatment of pensions and savings account |

GBR |

|

|

Employee share acquisition deductions |

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

3.1.7. SSC reforms introduced by countries continued to reduce contributions

Several countries have introduced SCC reforms, several of which involved temporary SCC reductions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. To provide financial relief to households and companies, and to promote the economic recovery, several countries have reduced the SSCs paid by workers and employers for a discrete period, both through SCC rate reductions and base narrowing measures. Several countries have increased SSCs permanently to respond to demographic and fiscal challenges.

Permanent changes to SSC rates have been limited while several countries introduced temporary cuts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

Three countries introduced permanent SSC rate reforms in 2021, including two rate increases and two rate reductions. Germany increased the additional contribution rate to statutory long-term care insurance by 0.1 p.p. to 0.35% for both employees and the self-employed without children, starting from January 2022. This increase reflects the continuation of a trend of rising contribution rates in response to an ageing population and a higher expected dependency ratio. Hungary’s SSC measures moved in the opposite direction, as employer SSCs were reduced from 15.5% to 13% in January 2022, having already been cut by 2 p.p. in July 2020. The 1.5% training fund contribution levied on employers was also phased out in 2022. In Norway, SSCs for employees were reduced from 8.2% to 8.0% and for the self-employed from 11.4% to 11.2%.

Italy and Sweden introduced temporary SSC rate cuts to alleviate financial pressure on companies and private households and promote economic recovery amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Italy has temporarily reduced SSCs for incomes below EUR 35 000 (USD 41 396) from 9.19% to 8.39% for the tax year 2022, with the aim of promoting economic recovery and supporting lower-income households. Sweden further decreased SSCs paid by employers for employees aged between 19 and 23 years old. The temporary reduction was first introduced in January 2021 and the augmented reductions will apply between June 2022 and August 2022. The reform intends to promote the employment of young workers as well as to support companies in the sectors that were significantly affected by the pandemic.

Table 3.6. Changes to social security contribution rates

|

Rate increase |

Rate decrease |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

2021 or later |

|

|

Employers SSCs |

JPN |

HUN, SWE1 |

|

Employees SSCs |

DEU, JPN |

ITA1, NOR |

|

Self-employed |

DEU |

|

|

Payroll taxes |

Note: 1. Denotes a temporary SSC reform.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

Most countries have continued to narrow their SSC bases, often in response to the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic

Bulgaria and Norway increased the minimum threshold for SSCs, reducing their countries’ SSC bases. Bulgaria increased its minimum income threshold for SSCs from BGN 7 800 (USD 4 716) to BGN 8 520 (USD 5 152). The new threshold also applies to self-employed workers and registered farmers and tobacco producers (previously minimum threshold of BGN 5 040 (USD 3 048)). Similarly, in Norway, the minimum income limit was raised from NOK 59 650 (USD 6 944) to NOK 64 650 (USD 7 526) for the tax year 2022.

Some countries introduced SSC measures to promote education and employment, which also narrowed SSC bases. Argentina introduced an employer SSC deduction for new hires participating in vocational training in knowledge-intensive sectors (IBFD, 2021[22]), to promote skills development in these areas. In Australia, to encourage employers to help workers transition to new employment opportunities, employers are exempted from the fringe benefits tax, if benefits are provided for retraining and reskilling to redundant, or soon to be redundant, employees. In Manitoba, Canada the exemption threshold for the Health and Post-Secondary Education Tax Levy on employers was raised from CAD 1.5 million (USD 1.2 million) to CAD 1.75 million (USD 1.4 million) of total annual remuneration paid to employees. The threshold below which employers pay a reduced rate was also increased from CAD 3 million (USD 2.4 million) to CAD 3.5 million (USD 2.8 million), effective from January 2022.

Several base narrowing measures were extended or introduced in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Sweden continued the tax-exempt status of certain benefits-in-kind offered by employers for their employees, such as free parking and certain gifts to encourage consumption. Argentina extended the 95% reduction in SCCs for employers providing health care services, first introduced in March 2020 until June 2022 (IBFD, 2022[23]). Uruguay introduced a temporary exemption from SSCs for employers in the catering and hospitality sector between July 2021 and October 2021.

Three countries broadened their SSC bases. In Bulgaria, the maximum social security income base was increased from BGN 36 000 (USD 21 768) to BGN 40 800 (USD 24 671), applicable to both employer and employee contributions from April 2022. Latvia raised its SSCs income ceiling from EUR 62 800 (USD 74 276) to EUR 78 100 (USD 92 372), effective from January 2022. Romania introduced a health contribution for pensioners with pension income above RON 04 000 (USD 961).

Table 3.7. Changes to social security contribution and payroll tax bases

|

Base broadening |

Base narrowing |

|

|---|---|---|

|

2021 or later |

2021 or later |

|

|

Employers SSCs |

BGR |

ARG, AUS, CAN |

|

Employees SSCs |

BGR, LVA |

BGR, NOR, SWE1, URY1 |

|

Self-employed |

BGR, BEL |

Note: 1. Denotes a temporary reform. The narrowing of the payroll tax base in the United States was the result of changes to the employee retention credit and the deferral of social security taxes originally introduced as part of the CARES Act.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

3.2. Corporate income taxes and other corporate taxes

The declining trend in statutory corporate income tax (CIT) rates is widespread and continuing, leading to further convergence in CIT rates across countries. In addition, many countries have continued to increase the generosity of their corporate tax incentives to stimulate investment and innovation, particularly in the field of environmental sustainability. Regarding international taxation, efforts to protect CIT bases against corporate tax avoidance have continued with the adoption of measures in line with the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. A major break-through has been reached with more than 135 jurisdictions worldwide having joined a new two-pillar plan to reform the international taxation rules and ensure that multinational enterprises (MNEs) pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate and generate their profits.

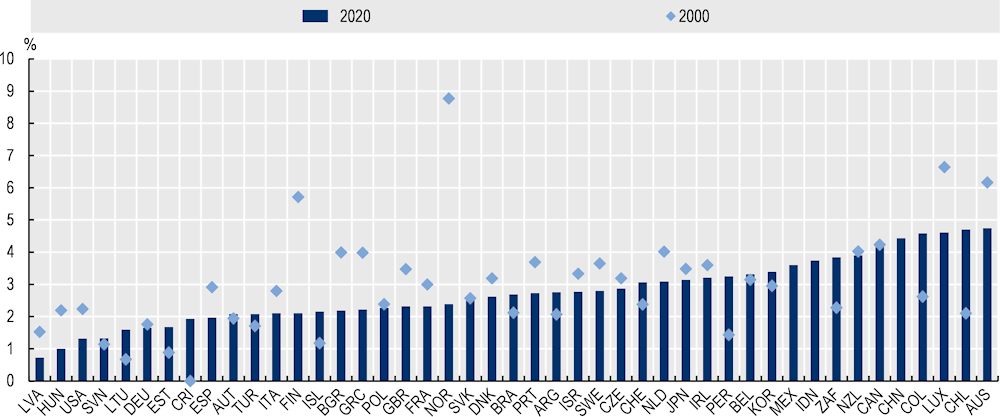

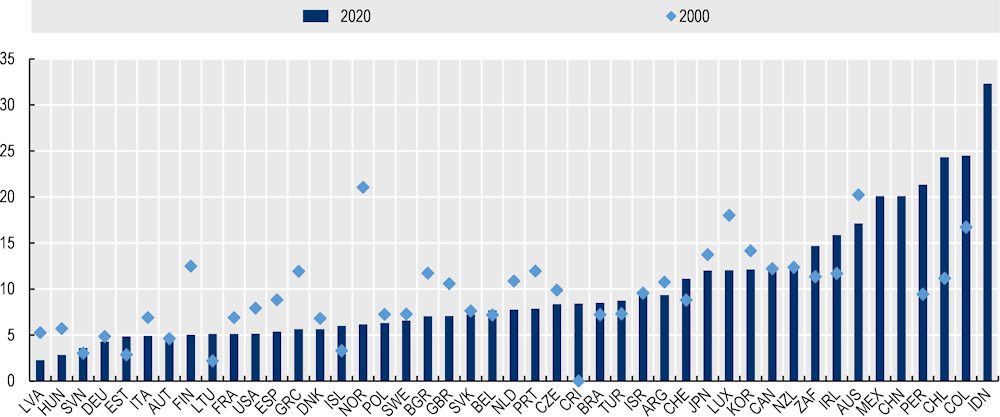

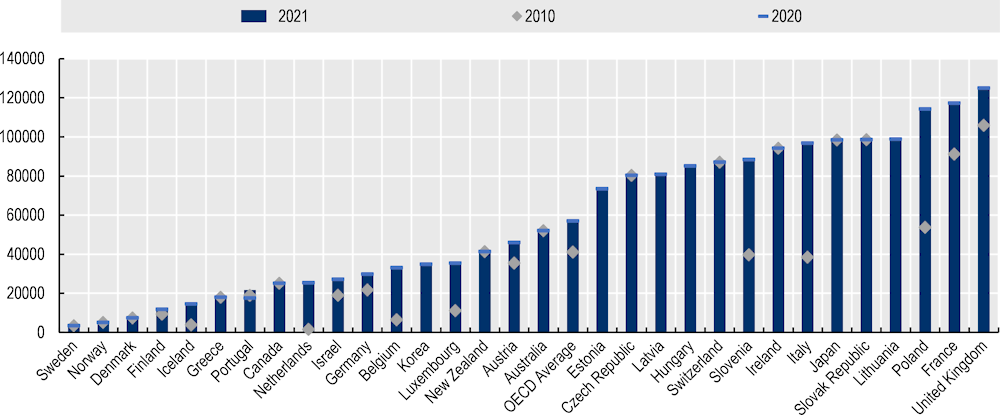

3.2.1. Trends in CIT revenues have varied across countries

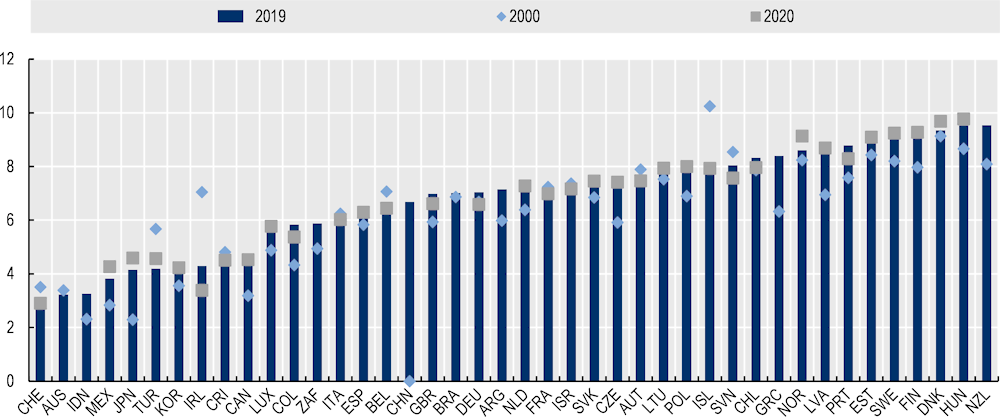

The ratios of CIT to GDP and CIT revenues as a share of total tax revenues continue to vary substantially across Inclusive Framework jurisdictions. CIT revenues ranged from 0.7% of GDP in Latvia to 4.7% of GDP in Australia in 2020 (Figure 3.5). As a share of total tax revenues, CIT ranged from 2.3% of total taxation in Latvia to 32.3% of total tax revenues in Indonesia (Figure 3.6). Multiple factors can explain differences in revenues from CIT including statutory CIT rates, the breadth of the CIT base, the degree to which firms are incorporated, the phase in the economic cycle and the degree of cyclicality of the corporate tax system, as well as countries’ reliance on other taxes. These factors likely contributed to the large variations in revenues observed between 2000 and 2020 in several countries, including Norway, Finland, and Luxembourg. Figure 3.6 shows that CIT tends to represent a larger share of revenue in countries with significant natural resources and in emerging economies. In the case of emerging economies, total tax revenues are generally lower as a percentage of GDP and personal income tax revenues tend to play a smaller role than the CIT.

Figure 3.5. Corporate income tax revenues as a share of GDP, 2000 and 2020

Note: Data for CIT revenues in 2000 were not available for China (People's Republic of), Indonesia and Mexico. 2019 data were used for Australia, China (People’s Republic of), Greece, Indonesia, New Zealand, and South Africa where 2020 were not yet available.

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database.

Figure 3.6. Corporate income tax revenues as a share of total tax revenues, 2000 and 2020

Note: Data for CIT revenues in 2000 were not available for China (People's Republic of), Indonesia and Mexico. 2019 data were used for Australia, China (People’s Republic of), Greece, Indonesia, New Zealand, and South Africa where 2020 were not yet available.

Source: OECD Global Revenue Statistics Database.

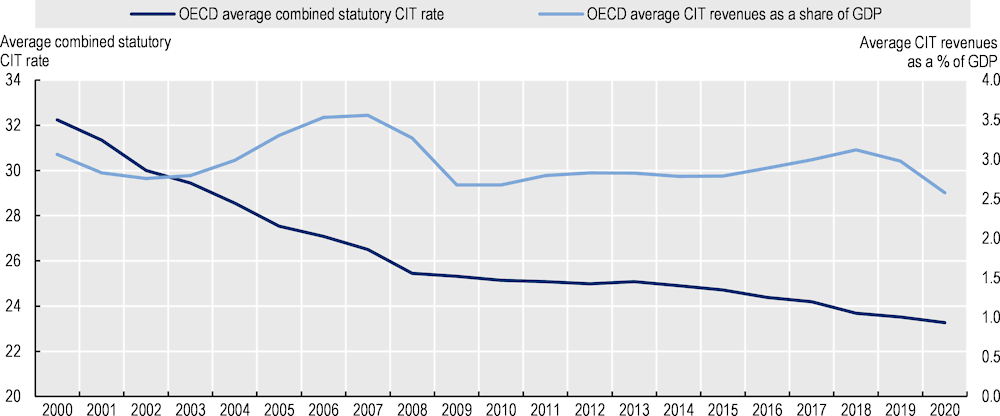

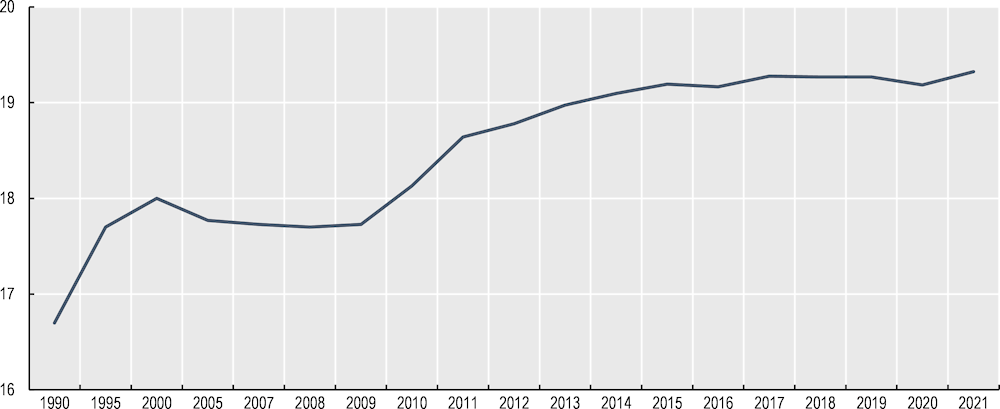

CIT revenues as a share of GDP and as a share of total tax revenues have fallen between 2019 and 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the 35 OECD countries for which 2020 data are available,9 the average value of corporate income tax revenues as a share of GDP fell from 3.0% in 2019 to 2.6% in 2020 (Figure 3.7). Similarly, the average value of corporate income tax revenues as a share of total tax revenues fell from 9.4% to 8.5%. This is the most significant reduction seen since the global financial crisis of 2008 and the average corporate income tax revenues as a share of GDP are now lower than the previous lows seen in 2009 and 2010 in the aftermath of that crisis.

Figure 3.7. Evolution of the average combined statutory CIT rate and average CIT revenues in OECD countries, 2000-2020

Note: Combined statutory CIT rates refer to central and sub-central statutory CIT rates.

Source: OECD Revenue Statistics Database and OECD Tax Database.

3.2.2. There has been a steady and widespread decline in corporate income tax rates

Standard corporate income tax rates

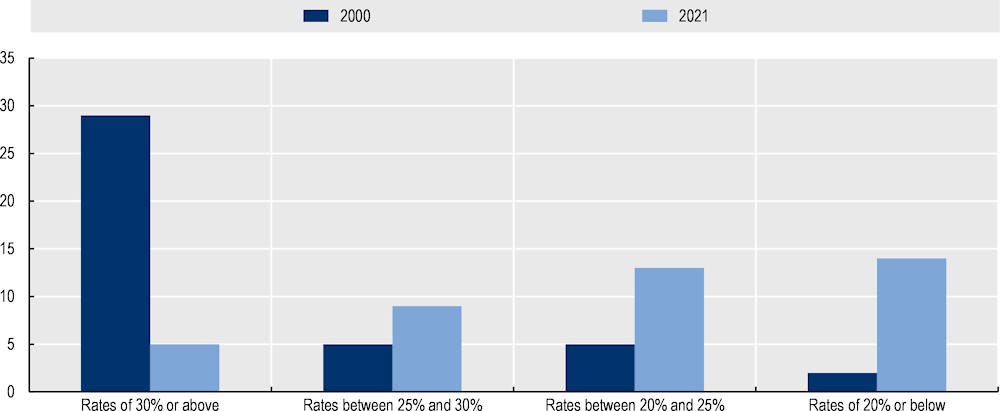

The decline in CIT rates has been a steady and widespread trend. Figure 3.8 shows the changes in the distribution of CIT rates between 2000 and 2021 across the 51 countries for which data are available10 and highlights major shifts in the CIT landscape. In 2021, there were only three countries with CIT rates above 30%, compared to 28 in 2000. Meanwhile, the number of countries with CIT rates below 20% increased from three in 2000 to 20 in 2021. Overall, in the OECD, the average combined (central and sub-central) CIT rate has declined from 32.2% in 2000 to 23.3% in 2021.

Figure 3.8. The distribution of combined statutory CIT rates, 2000 and 2021

Note: Countries covered include OECD member jurisdictions plus Argentina, China (People’s Republic of), Indonesia, and South Africa.

Source: OECD Corporate Tax Statistics Database, OECD Tax Database and OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

CIT rates were cut in four countries in 2021. Notably, only one of these reductions was in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, suggesting that countries have in general identified other approaches to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Reductions in combined CIT rates were introduced in Colombia, France, Sweden, and Switzerland. In Colombia, the standard CIT rate was lowered to 31% as part of the government’s 2019 legislation to progressively reduce CIT rates (from 33% in 2019 to 30% by 2022). France also lowered its standard CIT rate, to 27.5% for companies with an annual turnover exceeding EUR 250 million (USD 296 million) and to 26.5% for companies with an annual turnover lower than EUR 250 million. These cuts were part of a previously legislated CIT rate reduction, which is expected to progressively bring the CIT rate down to 25% by 2022. Sweden implemented a permanent cut in its standard CIT rate from 21.4% to 20.6% as a part of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In Switzerland, 11 of 26 cantons made small reductions to their corporate tax rates. The largest were made by those cantons with the highest rates, namely the Cantons of Valais (-1.6%), Zurich (-1.5%) and Bern (-0.6%). These cuts reduced the combined corporate income tax rate in Switzerland from 21.15% in 2020 to 19.7% in 2021.11

However, three countries – Colombia, Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates – announced increases in their headline CIT rates. At the end of Q3 of 2021, Colombia enacted a Law under its Social Investment Act to increase the corporate income tax rate to 35% from 1 January 2022 – a notable change of direction from the planned decreases described above. In addition, this Law imposed a 3% surtax on the taxable income of financial institutions earning more than 120 000 tax units (approximately USD 1.1 million) from 2022 to 2025 (their total income tax rate will therefore rise to 38% for these institutions). Following an increase to 22% for the fiscal years 2018-2020, Türkiye further raised its corporate tax rate to 25% in 2021.12, 13

The United Arab Emirates announced an historic change to their tax system, with the introduction of a generalised Corporate Income Tax from mid-2023. The tax will operate as a federal corporate tax on business profits and will enter into force from Q3 2023. The proposed CIT rate of 9% on taxable income above AED 375 000 (USD 100 000) is expected to apply to all business activities in the UAE, while a different rate (yet to be confirmed) is envisaged to apply to large multinationals that generate consolidated global revenues above EUR 750 million (USD 887 million). Exceptions to this new CIT are planned for the extraction of natural resources, which is already subject to taxation at an Emirate-level.

Table 3.8. Changes in corporate income tax rates

Note: Countries in brackets have only announced reforms.

1. The CIT rate decrease in Canada for 2021 applies to zero-emission technology manufacturing profits. The CIT rate decrease will reduce the general corporate income tax rate and small business income tax rate on eligible profits to 7.5% (from 15%) and to 4.5% (from 9%), respectively, for taxation years beginning after 2021 and before 2029.

Source: OECD Annual Tax Policy Reform Questionnaire.

CIT rates for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

Reduced CIT rates for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are common across the Inclusive Framework jurisdictions that responded to the Tax Policy Reforms questionnaire. Several countries provide reduced CIT rates for SMEs, although the design of these reduced tax rates varies significantly. Some countries apply lower tax rates on the first tranche(s) of profits, regardless of total income levels; some have reduced CIT rates for corporations with income below a certain level; and others determine eligibility for small business tax rates based on non-income criteria (e.g., turnover or assets) instead of, or in addition to, income criteria.

Several countries changed the CIT rates for SMEs between 2020 and 2021 (and beyond). To reduce the tax burden for SMEs, Hungary decreased its small business tax from 12% to 11% in 2021 and by another percentage point to 10% in January 2022. In addition, the maximum local business tax for SMEs with income of less than HUF 4 billion (USD 12.99 million) has been set to 1% for 2021 and 2022. Canada introduced a 50% reduction to business income taxes for companies that manufacture zero-emission technologies from the start of 2022. This reduction in the general corporate income tax rate and small business income tax rate on eligible profits to 7.5% (from 15%) and to 4.5% (from 9%), respectively, will be gradually phased out from 2029 with elimination envisaged by 2032. Moreover, reductions to SME CIT rates at the provincial and territorial level (Northwest Territories, Prince Edward Island, Quebec, Yukon) took effect in early 2021.

A small number of developing countries also temporarily reduced the effective SME CIT rate that businesses need to pay due to the COVID-19 impact on economic activity. Brunei Darussalam, for instance, will provide a 50% CIT discount for the tax year 2022, targeting sectors that were particularly affected by the pandemic such as tourism, hospitality (including hotels and lodging houses), restaurants and cafes, and air and water transportation. In Cabo Verde, SMEs whose sales were particularly impacted by the pandemic were exempt from paying the islands’ Unified Special Tax of 4% in 2021.

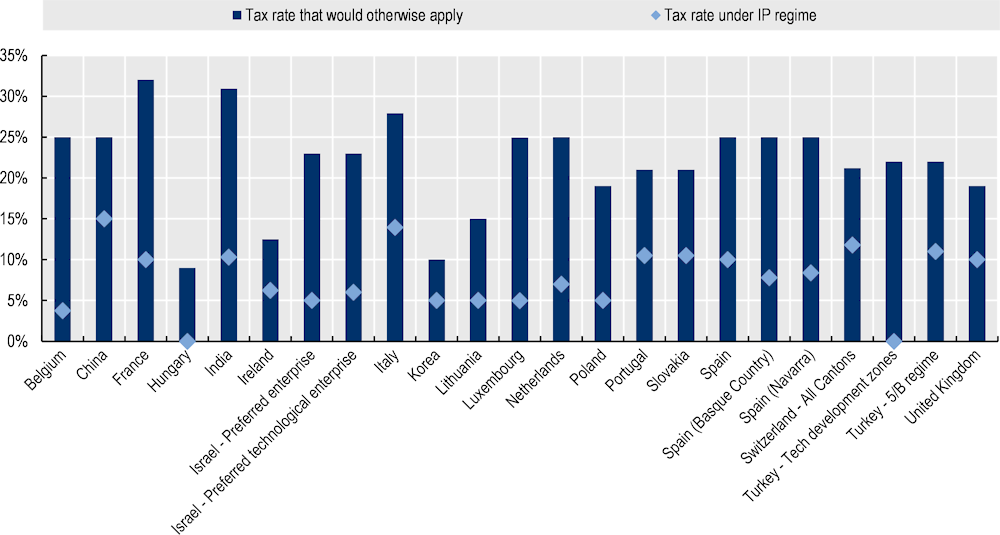

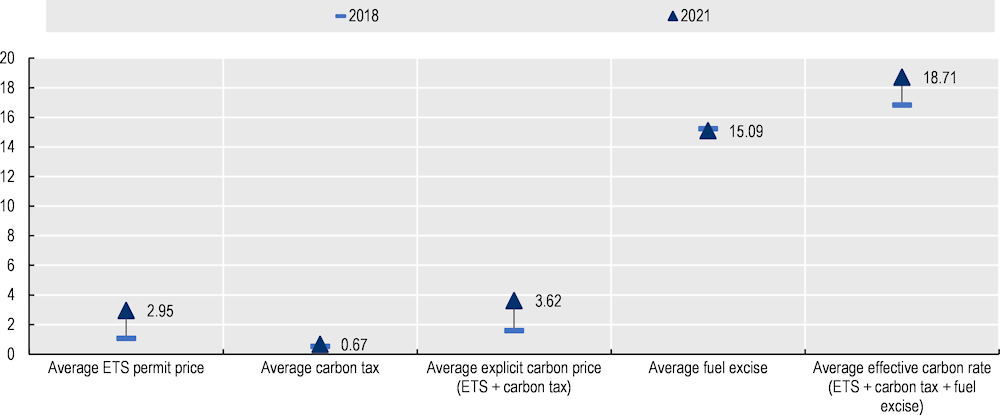

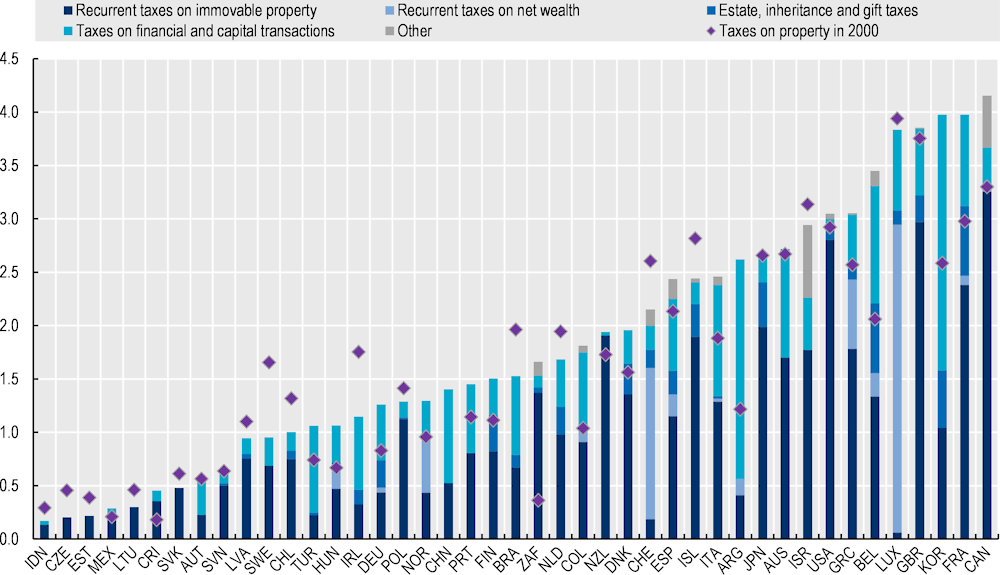

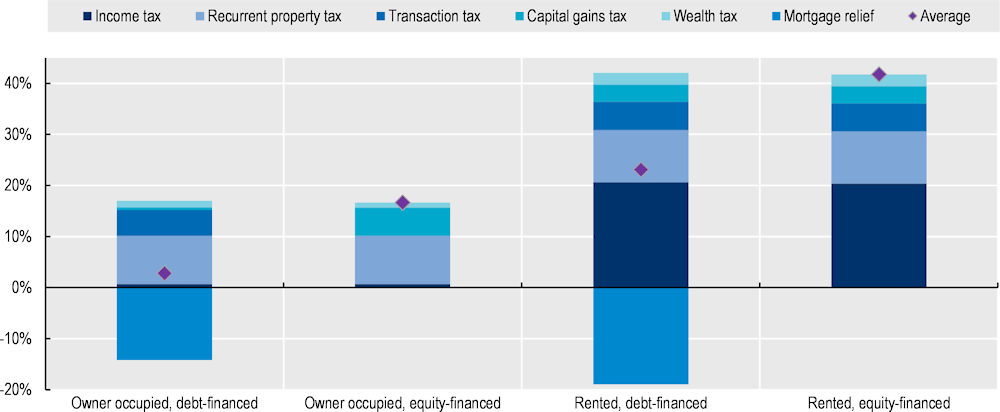

Other business taxes