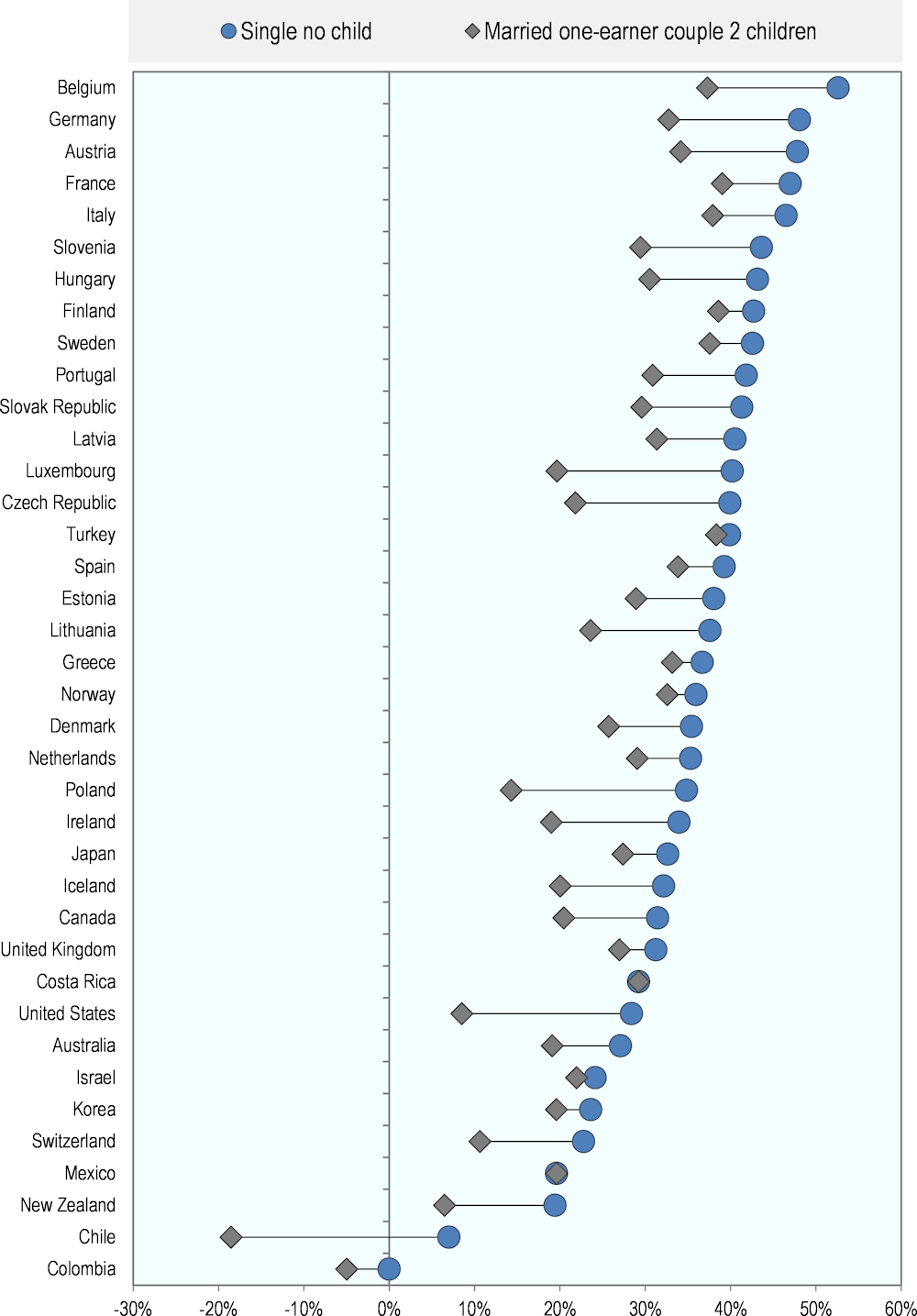

Table 3.11 and Figure 3.1 show the average tax wedge for 2021, calculated as the combined burden of income tax, employee and employer social security contributions (SSCs) taking into account the amount of cash benefits to which each specific household type was entitled. Total taxes due minus transfers received are expressed as a percentage of labour costs, defined as gross wage plus employers’ SSCs (including payroll taxes). In the case of a single person on the average wage (AW), the tax wedge ranged from zero (Colombia) and 7.0% (Chile) to 48.1% (Germany) and 52.6% (Belgium). For a one-earner married couple with two children, at the average wage level, the tax wedge was lowest in Chile (-18.5%) and Colombia (-5.0%) and highest in Finland (38.6%) and France (39.0%). As stated in Chapter 1, the tax wedge tends to be lower for a married couple with two children at this wage level than for a single individual without children due to receipt of cash benefits and/or more advantageous tax treatment. It is also interesting to note that the tax wedge for a single parent with two children, earning 67% of the AW, was negative in Chile (-24.4%), New Zealand (-16.3%), Colombia (-7.4%), Australia (-1.0%) and the United States (-0.1%). Negative tax wedges are due to the cash benefits received by families, plus any applicable non-wastable tax credits, exceeding the sum of the total tax and social security contributions that are due.

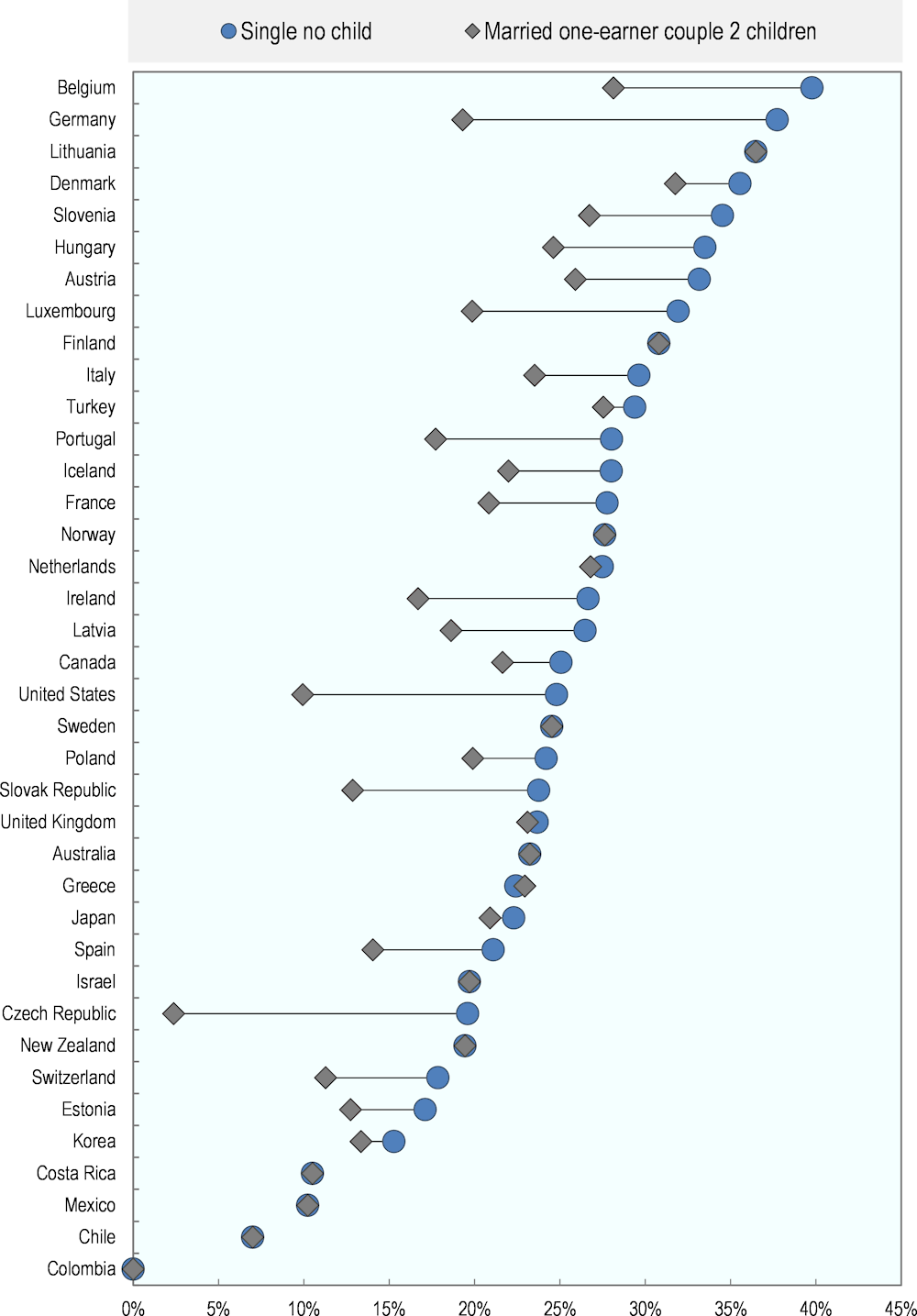

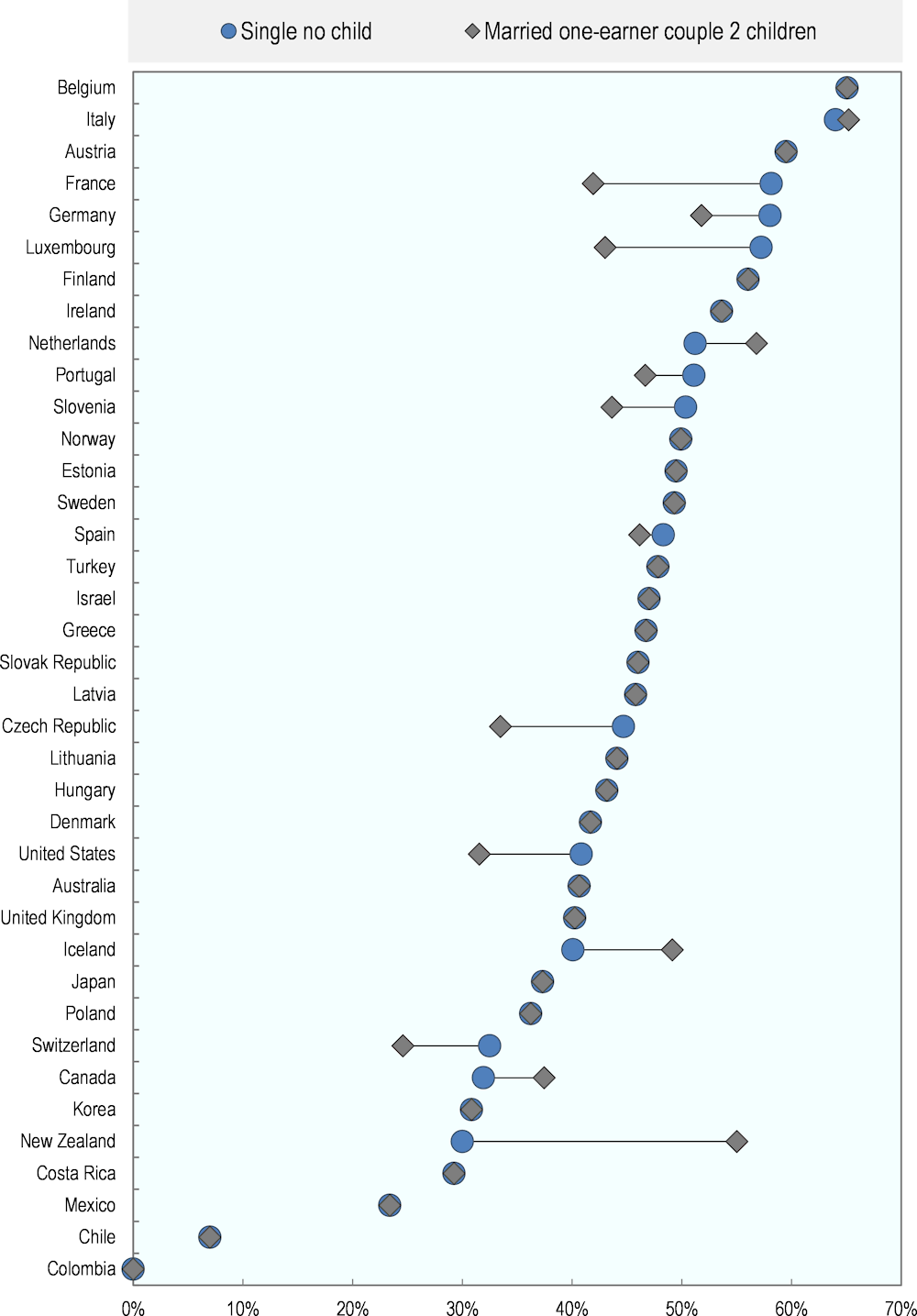

Table 3.2 and Figure 3.2 present the combined burden of the personal income tax and employee SSCs in 2021, expressed as a percentage of gross wage earnings (the corresponding measures for income tax and employee contributions separately are shown in Tables 3.4 and 3.5). For single workers at the average wage level without children, the highest average tax plus contributions burdens were seen in Germany (37.7%) and Belgium (39.8%). The lowest average rates were in Colombia (0.0%), Chile (7.0%), Mexico (10.2%), Costa Rica (10.5%), Korea (15.3%), Estonia (17.1%), Switzerland (17.9%), New Zealand (19.4%), the Czech Republic (19.6%) and Israel (19.7%).

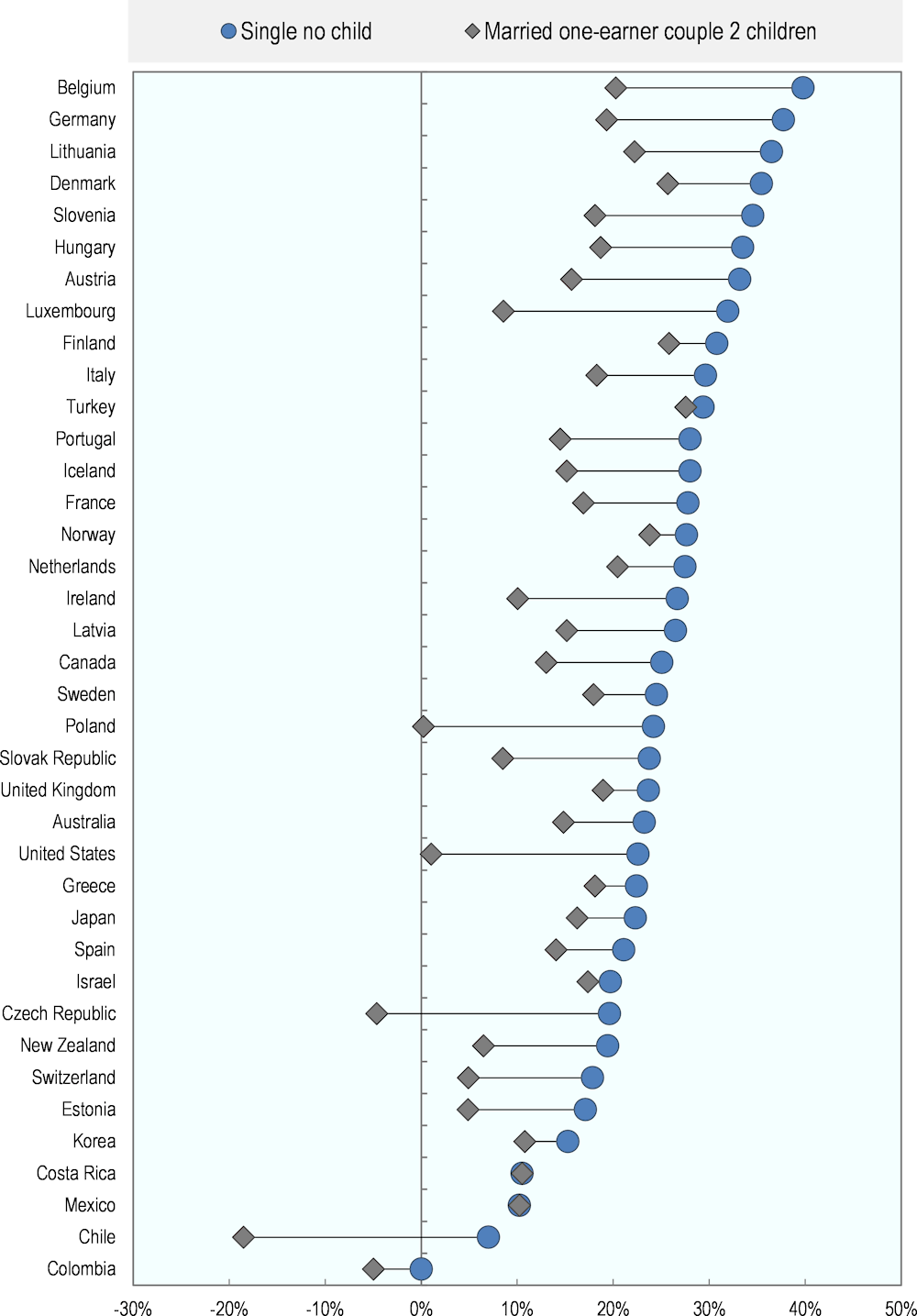

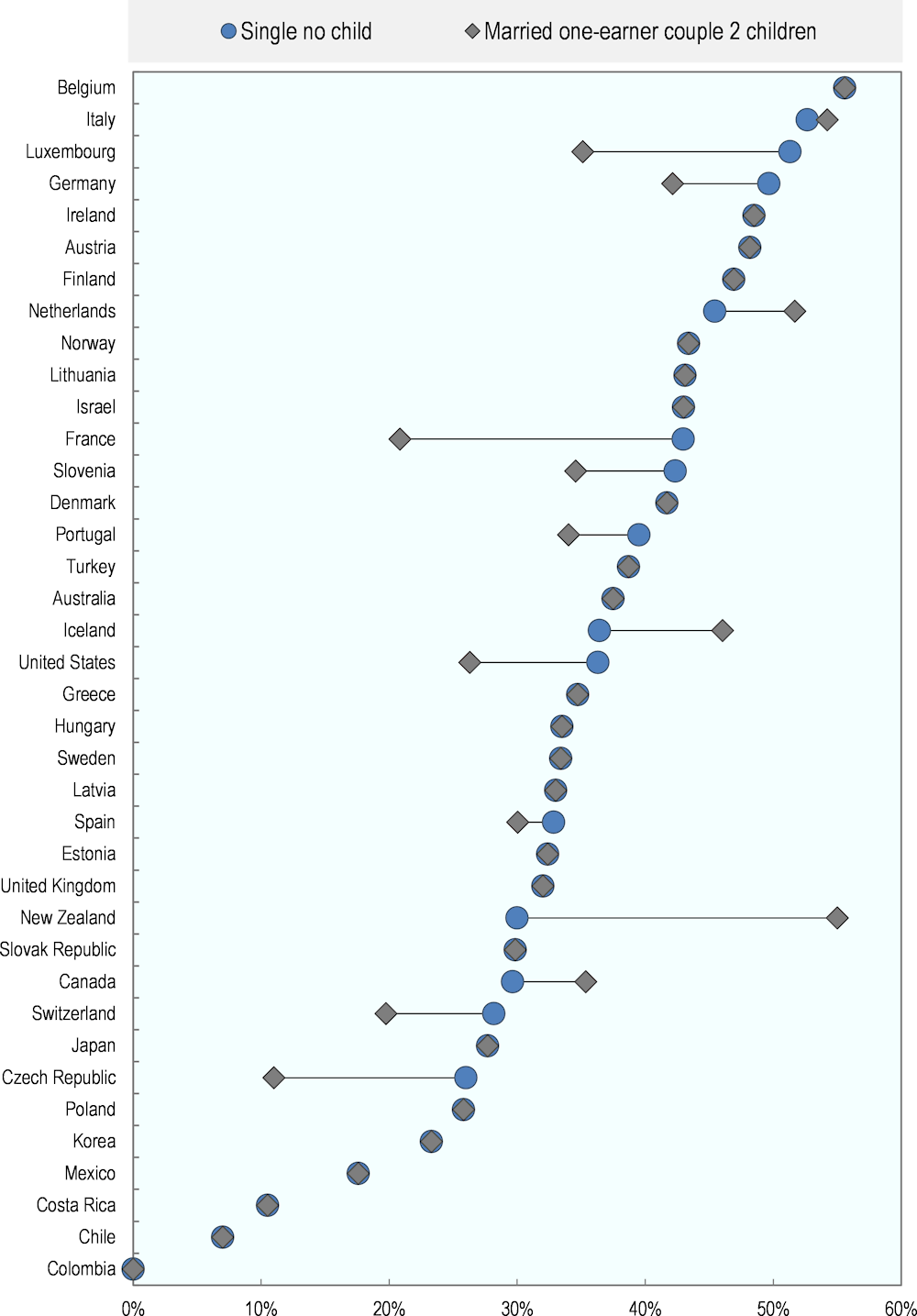

Table 3.3 shows the combined burden of income tax and employee SSCs, reduced by the entitlement to cash benefits, for each household type in 2021. Figure 3.3 illustrates this burden for single individuals without children and one-earner married couples with two children, with both household types on average earnings. Comparing Table 3.2 and Table 3.3, the average tax rates for families with children (columns 4 -7) are lower in Table 3.3 because most OECD countries support families with children through cash benefits.

Comparing Table 3.2 and Table 3.3 for single parents with two children earning 67% of the average wage shows that 33 countries provided cash benefits in 2021. In Poland, New Zealand and Chile, these represented respectively 31.7%, 31.6% and 31.4% of income and they exceeded 25% of income in Denmark (25.7%). Thirty-three countries provided cash benefits for a one-earner married couple, with two children, earning the average wage level, although these were less generous relative to income, ranging up to 19.7% in Poland and 25.5% in Chile. The lower level of cash benefits for the married couple can be attributed to three reasons: single parents may be eligible for more generous treatment; the benefits themselves may be fixed in absolute amount; or the benefits may be subject to income testing.

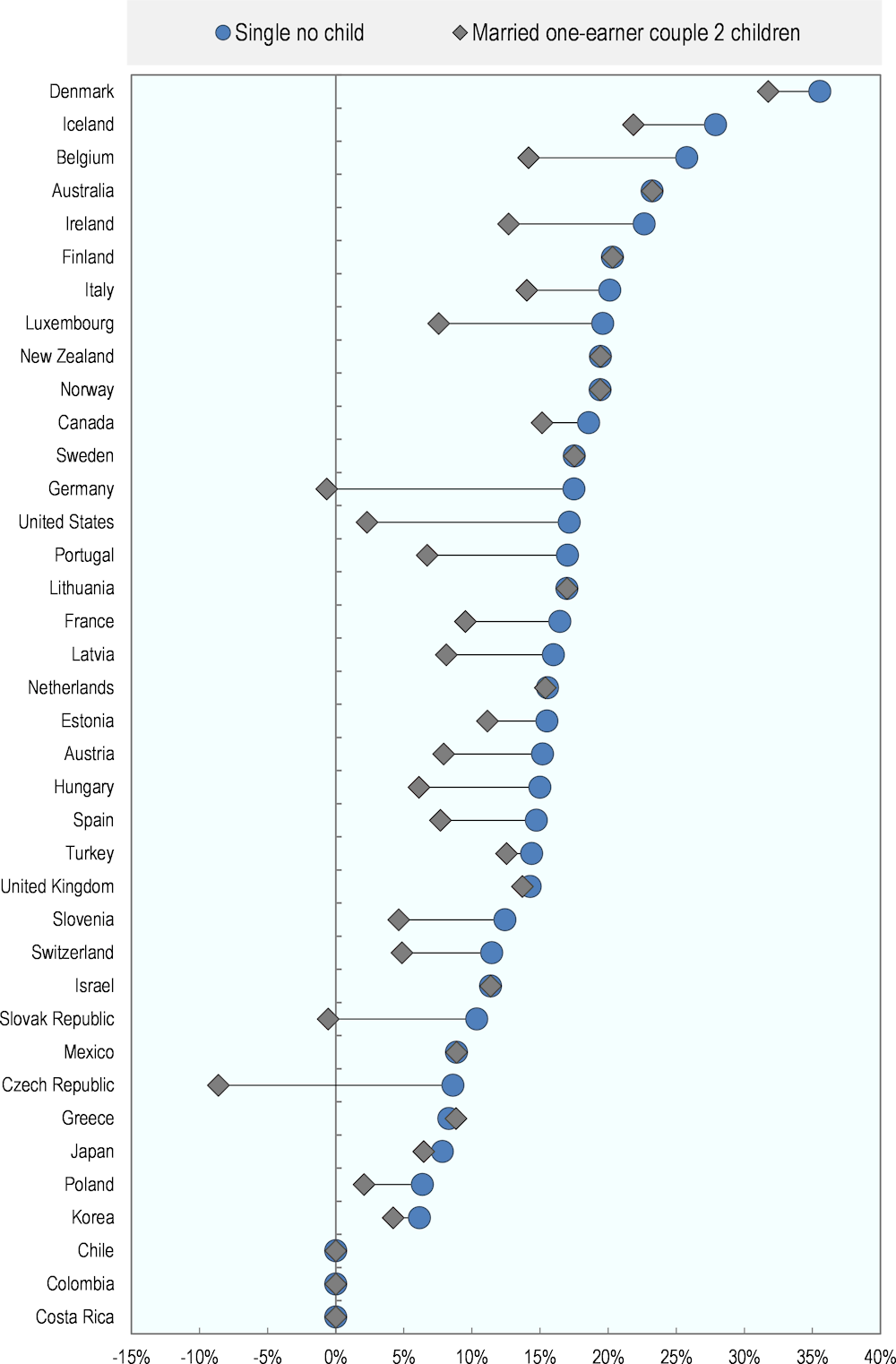

Table 3.4 shows personal income tax due as a percentage of gross wage earnings in 2021. For single persons without children at the average wage (column 2), the income tax burden ranged from 0.0% (Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica) to 35.5% (Denmark). In most OECD member countries, at the average wage level, the income tax burden for one-earner married couples with two children is lower than that for single persons (compare columns 2 and 5). These differences are illustrated in Figure 3.4. In twelve OECD countries, the income tax burden faced by a one-earner married couple with two children is less than half that faced by a single individual (the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Switzerland and the United States). In contrast, there was no difference in eleven countries: Australia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Finland, Israel, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden. In Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica, neither the single worker on the average wage nor the one-earner married couple at the average wage paid personal income taxes.

There were only three OECD countries where a married average worker with two children had a negative personal income tax burden. This was due to the presence of non-wastable tax credits, whereby credits were paid in excess of the taxes otherwise due. This resulted in tax burdens of -0.5% in the Slovak Republic, -0.7% in Germany and -8.6% in the Czech Republic. Similarly, single parents with two children earning 67% of the average wage showed a negative tax burden in seven countries: Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Spain and the United States. In four other countries – Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica and Israel – this household type paid no income tax.

Comparison of columns 5 and 6 in Table 3.4 demonstrates that if the second spouse had a job that paid 67% of the average wage, the income tax burden of the household (now expressed as 167% of the average wage) was slightly higher in 22 countries, the largest differences being in the Czech Republic (9.1 percentage points) and Germany (9.8 percentage points). At the same time, the income tax burden was lower in thirteen countries, the largest differences being in the Netherlands (-4.9 percentage points) and Israel (-4.0 percentage points). There was no impact on the tax burden in Chile, Colombia and Costa Rica.

An important consideration in the design of an income tax is the degree of progressivity – the rate at which the income tax burden increases with income. A comparison of columns 1 to 3 in Table 3.4 provides an insight into the progressivity of income tax systems of OECD countries. Comparing the income tax burden of single individuals at the average wage level with their counterparts at 167% of the average wage (columns 2 and 3), the lower-paid worker faced a lower tax burden in all countries except in Colombia and Hungary in 2021. In Colombia, neither the average single worker nor their counterpart at 167% of the average wage paid income tax. In Hungary, a flat tax rate was applied on labour income and all households without children paid the same percentage of income tax. Comparing single individuals at 67% of the average wage level with their counterparts at the average wage level (columns 1 and 2), the lower-paid worker also faced a lower tax burden across all OECD countries, except Colombia and Hungary for the reasons previously mentioned. Finally, the burden faced by single individuals at 67% of the average wage level represented less than 25% of the burden faced by their counterparts at 167% in five OECD countries: Chile (0.0%), Costa Rica (0.0%), Greece (16.7%), the Netherlands (18.7%) and Korea (23.6%).

The addition of SSCs to the average tax rate reduces this progressivity as well as the proportional tax savings (i.e. tax savings of the low-income workers relative to higher-income workers). When comparing Table 3.2 with Table 3.4, the OECD personal average tax burden including SSCs for single individuals at 67% of the average wage level was only 31.7% lower than their counterparts at 167% compared to the OECD average tax savings of 48.0% for personal income taxes alone in 2020. The OECD average tax savings observed for one-earner married couples with two children at the average wage level relative to the average single worker fell from 33.6% for the personal income tax to 20.5% for the personal average tax burden including SSCs. These lower figures reflect that there is little variation in SSC rates across household types, as shown in Table 3.5.

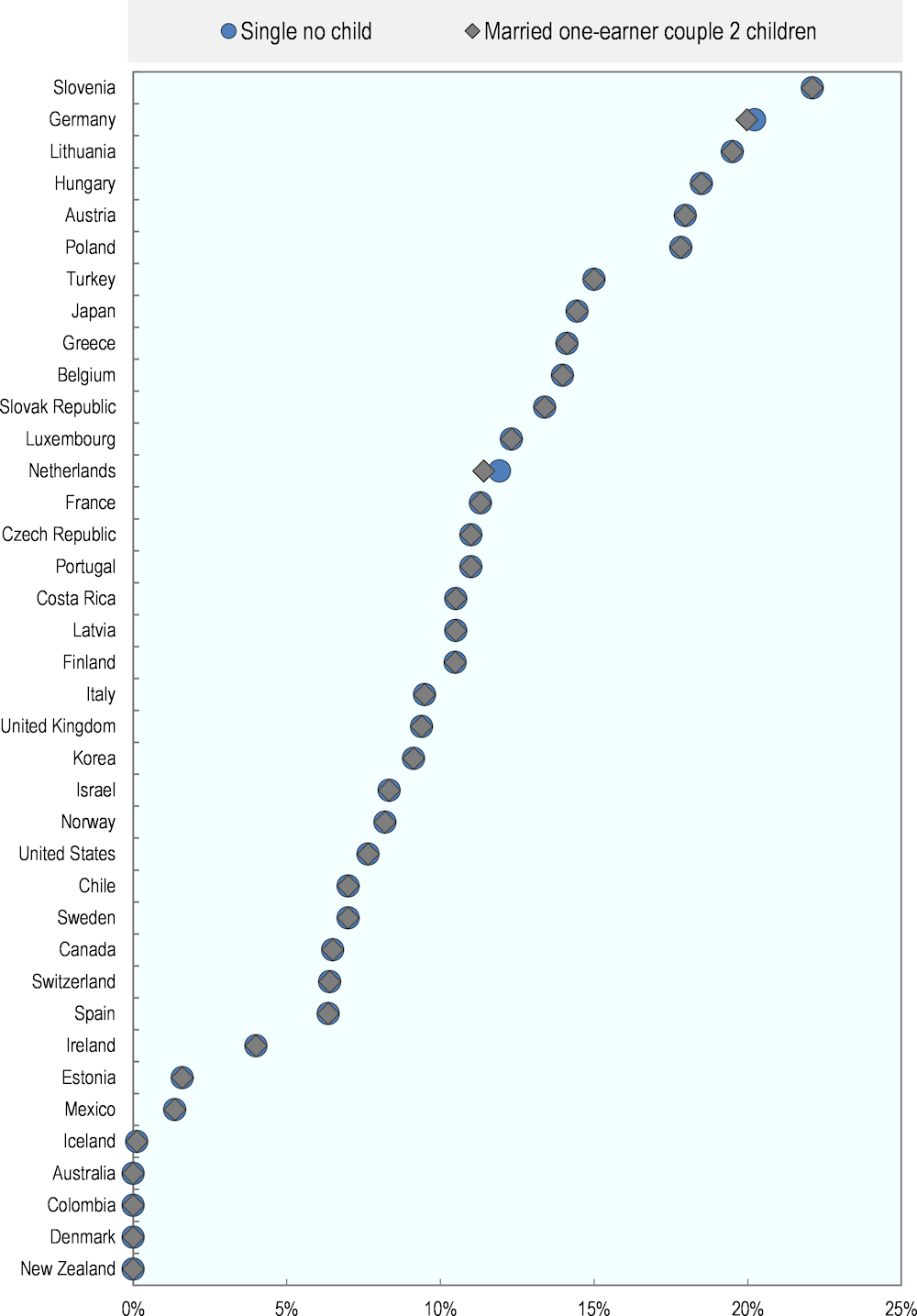

Table 3.5 shows employee SSCs as a percentage of gross wage earnings in 2021. For a single worker without children at the average wage (column 2), the contribution rate varied between zero (Australia, Colombia, Denmark and New Zealand) and 22.1% (Slovenia). Australia, Denmark and New Zealand did not levy any employee SSCs paid to general government. In Colombia, most of the SSCs are paid to funds outside the general government and are considered to be non-tax compulsory payments. Therefore, they are not counted as SSCs in the Taxing Wages calculations. There were three other countries with very low rates: Iceland (0.1%), Mexico (1.4%) and Estonia (1.6%).

SSCs are usually levied at a flat rate on all earnings, i.e. without any exempt threshold. In a number of OECD member countries, a ceiling applies. However, this ceiling usually applies to wage levels higher than 167% of the AW. The flat rates result in a constant average burden of SSCs for most countries between 67% and 167% of average wage earnings. A constant proportional burden for employee SSCs for the eight model household types was observed in Slovenia (22.1%), Lithuania (19.5%), Hungary (18.5%), Poland (17.8%), Turkey (15.0%), Greece (14.1%), the Slovak Republic (13.4%), the Czech Republic and Portugal (both 11.0%), Latvia and Costa Rica (both 10.5%), Norway (8.2%), the United States (7.7%), Chile (7.0%), Spain and Switzerland (both 6.4%), Ireland (4.0%) and Estonia (1.6%).

In addition, at the average wage level, Germany and the Netherlands imposed different levels of SSCs on employees according to their family status (see Figure 3.5).