Merger review helps avoid anti-competitive economic concentrations and is a key component of competition regimes. Merger guidelines play a crucial role in ensuring an effective merger control regime and can be particularly useful in younger competition regimes, where the competition culture is still emerging. The Tunisian competition law framework regarding merger review has a series of limitations, including a very high turnover-based notification threshold and the absence of two-phase and simplified merger control regime, as well as the lack of merger notification forms. Tunisia is currently seeking to implement merger guidelines and a draft was submitted to the OECD. This section presents an overview of merger guidelines in selected jurisdictions and reviews Tunisia’s draft guidelines on merger control.

The Role of Guidelines in Fostering Competition Policy in Tunisia

4. Merger control

Abstract

4.1. Overview of merger control in Tunisia

According to Article 7 of Act No. 2015-36 of 15 September 2015, a prior authorisation from the Minister of Trade is required for any proposed merger likely to create or strengthen a dominant position in the domestic market or a substantial part of thereof. The Tunisian merger control regime provides two alternative overall notification thresholds (i.e., referring to the merging firms together): a turnover-based test (turnovers exceeding TND 100 million in the domestic market) and a market share test (combined market share of 30% in the domestic market).

As pointed out by the Peer Review, the number of merger notifications in Tunisia is substantially lower than in other jurisdictions, for instance over 22 times lower than the MEA average in 2022 (OECD, 2024[8]). This is partially explained by the turnover-based threshold, which is too high vis-à-vis Tunisia’s current economic situation (OECD, 2022, pp. 105-106[1]).

The turnover-based threshold in force in Tunisia represented 0.0771% of the GDP in 2021. The table below summarises the selected jurisdictions examined in this report, including their GDP’s, their turnover notification thresholds, as well as the turnover notification thresholds as a percentage of GDP. These figures present how they can compare to the size of their economies, considered by using the GDP of such jurisdictions. They confirm that turnover-based threshold in Tunisia is indeed too high.

Table 4.1. Turnover notification thresholds in selected jurisdictions and their % of GDP in 2021

|

Jurisdiction |

GDP 2021 (current USD in millions) |

Threshold Level (USD) |

% of GDP |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tunisia |

46 687 |

36 010 000 |

0.0771 |

|

Selected OECD members |

|||

|

Belgium* |

594 104 |

118 300 000 47 320 000 |

0.0199 0.0079 |

|

Canada** |

1 988 336 |

319 120 000 74 195 400 |

0.0160 0.0037 |

|

European Union*** |

17 177 419 |

5 915 000 000 295 750 000 |

0.0344 0.0017 |

|

France**** |

2 957 880 |

177 450 000 59 150 000 |

0.0059 0.0019 |

|

Selected non-OECD members |

|||

|

Kenya***** |

110 347 |

9 100 000 910 000 |

0.0082 0.0008 |

|

Philippines****** |

394 086 |

101 500 000 40 600 000 |

0.0257 0.0103 |

|

South Africa******* |

419 015 |

40 620 000 6 770 000 |

0.0097 0.0016 |

Note: Some of the threshold levels above consider both individual and combined assets for all the parties involved in the transaction while others only require one of the parties to meet the threshold.

* Belgium has one threshold for the local size of all the merging parties and one for each of at least two of the parties concerned (in addition, the transaction must not fall within the jurisdiction of the European Commission).

** Canada has one threshold for the local size of all the merging parties and one for the size of the transaction.

*** The EU has one threshold for the worldwide size of all the merging parties and one for EU size for each of at least two of the parties concerned. There is also a second alternative involving lower thresholds.

**** France has one threshold for the worldwide size of all the merging parties and one for the local size for each of at least two of the parties concerned (in addition, the transaction must not fall within the jurisdiction of the European Commission). There are also specific lower thresholds applicable to mergers in the retail sector and to mergers in certain French overseas territories.

***** Kenya has one threshold for the local size of all the merging parties and one for the local size of the target undertaking. There are also specific thresholds for mergers in the healthcare, carbon based mineral and oil sectors. Transactions meeting the COMESA merger notification threshold are excluded from notification if at least two-thirds of the turnover or assets (whichever in higher) is not generated or located in Kenya.

****** The Philippines has one threshold for the local size of all the merging parties and one for the size of the transaction.

******* South Africa has one threshold for the local size of all the merging parties and one for the size of the transferred/target firm. These numbers refer to so-called “intermediate mergers”. There are also higher thresholds for so-called “larger mergers”.

Source: World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?name_desc=false and competition authorities’ website. Exchange rates (2021 average): TND 1 = USD 0.3601; CAD 1 = 0.7978; EUR 1 = USD 1.183; KES 1 = USD 0.0091; PHP 1 = USD 0.0203; ZAR 1 = USD 0.0677.

The turnover-based threshold is also too high when considering the size of companies operating in Tunisia. According to the OECD Economic Surveys: Tunisia 2018, once they are created, Tunisian firms tend to stay small, vis-à-vis the major constraints on market access, restrictive regulations, heavy taxation and problems in accessing financing (OECD, 2018, p. 66[9]). In fact, Tunisia had 828 821 firms in 2021, of which only 0.2% had more than 100 employees and less than 0.1% had more than 200 employees (Statistiques Tunisie, 2022, p. 17[10]).

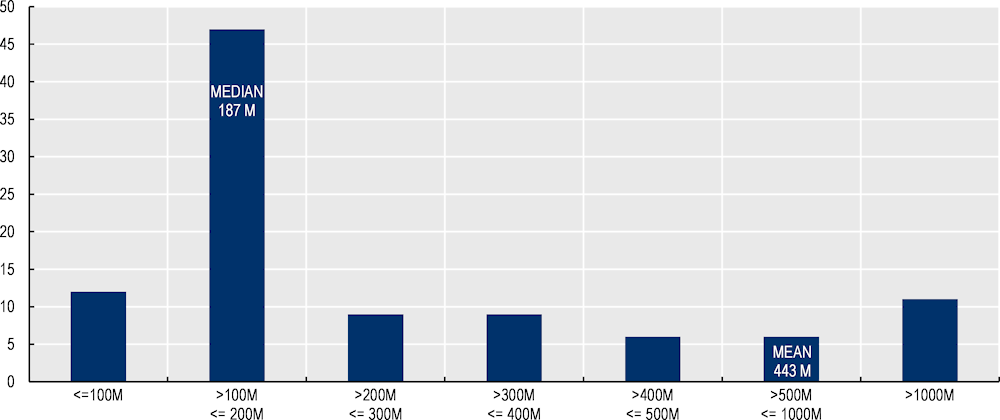

Figure 4.1 displays the turnover distribution of the 100 biggest companies in Tunisia, indicating that only 88 companies have a turnover of more than TND 100 million, the current turnover notification threshold. This implies that only 88 out of more than 800 thousand companies in Tunisia would have to notify a transaction, confirming that the current turnover notification threshold is indeed set too high.

Figure 4.1. Distribution of the turnover (TND) of Tunisia’s top 100 companies, 2019

Source: OECD based on data from L’Économiste Maghrébin ranking of Tunisian businesses.

Although the market share-based threshold could cover transactions that are not captured by the high turnover-based threshold, determining market shares at the notification stage may be challenging and is likely to lead to legal uncertainty and high costs for companies, as highlighted in the Peer Review (OECD, 2022, p. 104[1]). Moreover, in practice the market share-based threshold has not been effective in capturing anti-competitive transactions that do not meet the turnover-based threshold in Tunisia.

In addition, while the Minister of Trade is the competent authority to approve mergers, the Competition Council shall issue a non-binding opinion, advising the Minister, who can then (i) authorise the transaction; (ii) authorise the transaction subject to remedies; or (iii) block the transaction.

The competitive assessment focuses on whether a transaction will create or strengthen a dominant position, coupled with public interest considerations (in particular, the benefits of the transaction in terms of technical or economic progress and industrial policy objectives).

From 2015 to 2021, 34 mergers were notified to the Ministry of Trade, of which 30 were cleared without conditions, three were authorised subject to remedies, and one was blocked.

The insurance, microfinance, banking and audio-visual sectors are derogated from the general merger control regime by specific legislations, which establish special regimes for such sectors. In the insurance, microfinance and banking sectors, specific regulations give another authority the competence to review and approve mergers: the Minister of Finance (insurance and microfinance sectors) and the Licensing Commission, following an opinion prepared by the Central Bank of Tunisia (banking sector). In the case of mergers in the banking sector, the Competition Council is not even consulted, while there have been no mergers in the insurance and microfinance sectors. Moreover, there is an almost absolute prohibition of consolidation in the audio-visual sector (OECD, 2022, pp. 126-131[1]).

As the Peer Review indicated, Tunisia does not have two-phase or simplified merger control regime, which contributes to the long duration of merger review.

Moreover, there are no official merger notification forms in Tunisia, which could reduce discretion of what competition authorities may request merging parties during the merger review procedures. Merger notification forms are commonly implemented by competition authorities, spelling out the required information and documents that merging parties must submit within the merger notification. While they do not prevent competition authorities from requesting additional documents at a later stage, notification forms increase predictability to merging parties and tend to reduce the length of merger reviews. This is because the basic information will always be provided at the start of the process, and merging parties can collect the required information in advance of the administrative procedure. Notification forms usually vary according to whether they refer to a simplified or complex transaction. Many jurisdictions have introduced merger notification forms, including the jurisdictions selected for comparison in this report (i.e. Belgium, Canada, European Union, France, Kenya, the Philippines, and South Africa).

According to Article 43(2) of Act No. 2015-36, if companies implement the transaction prior to notification and approval when it fulfils the conditions listed in Article 7(3) of Act No. 2015-36 (so-called gun jumping), they may be fined up to 10% of their turnover in Tunisia, regardless of whether the failure to notify a notifiable transaction was unintentional or due to negligence. While Tunisian rules related to gun jumping seem to be in line with international best practices, the absence of enforcement deviates from the international practices. Indeed, while gun-jumping enforcement has been increased worldwide, Tunisian competition authorities have never sanctioned companies for such an infringement, even though non-notified transactions that fulfilled notification thresholds were identified (OECD, 2022, p. 106[1]).

Finally, notification of a merger is not subject to a notification fee in Tunisia, which could be one alternative that could increase the competition authorities’ budget (which in turn could be used to improve human resources) (OECD, 2022, p. 108[1]).

4.2. Merger control guidelines

Merger guidelines play a crucial role in ensuring an effective merger control regime and can be particularly useful in younger competition regimes, where the competition culture is still emerging. Merger guidelines outline the processes and considerations that competition authorities should take into account when reviewing proposed mergers and acquisitions. They also provide guidance on how to evaluate the potential effects of a merger on competition, including on market structure, pricing, and innovation.

Merger guidelines help competition authorities by providing a framework for evaluating the potential competitive effects of a proposed merger or acquisition. The content of merger guidelines can vary across competition authorities, often depending on the experience of the competition authority and the business community with merger control. They typically explain the most relevant concepts, elaborate on the general procedural steps and explore the criteria used to evaluate proposed mergers. Merger guidelines usually specify the types of information or analysis that authorities will typically consider when assessing a merger, including market definition, market concentration, barriers to entry, and the potential for co-ordinated or unilateral effects. This helps authorities to identify and investigate potentially problematic mergers, and to make informed decisions about whether to approve or challenge a proposed transaction. Additionally, as described in chapter 3, merger guidelines can also help provide transparency and predictability for merging or acquiring businesses, as they can better understand the types of factors that will be considered in a merger review. This is in line with the OECD Recommendation on Merger Review, which states that jurisdictions should ensure that the rules, policies and procedures involved in the merger review process are transparent and publicly available (OECD, 2005[11]).

This section considers the elements commonly covered in merger guidelines by comparing guidelines published in the selected jurisdictions.1 It also considers the draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines submitted by the Tunisian competition authorities to the OECD in September and October 2023.

In 2004, the International Competition Network (ICN) published a report following a review of the merger guidelines in operation at that time (ICN, 2004[12]), later complemented in 2006 (ICN, 2006[13]). The key elements of the guidelines identified in those reports have been used as an inspiration for the comparative table of merger guidelines in selected jurisdictions (Table A A.2). A list of the merger guidelines in the selected jurisdictions is set out in Table A A.1.

4.2.1. Overview of guidelines reviewed

The project team has assessed the merger guidelines the selected jurisdictions, listed in Table A A.1 and summarised in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2. Overview of guidelines reviewed

|

Jurisdiction |

Number of guidelines |

Substantive |

Procedural |

Combined |

Date of first guideline |

Date of commencement of merger regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

||||||

|

Belgium* |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1991 |

|

Canada |

5 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

1991 |

1910 |

|

European Union |

6 |

4 |

2 |

- |

2003 |

1989 |

|

France |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

2004 |

1977 |

|

Non-OECD countries |

||||||

|

Kenya |

2 |

1 |

- |

1 |

2021 |

2010 |

|

Philippines |

4 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2016 |

2015 |

|

South Africa** |

3 |

1 |

2 |

- |

2016 |

1979 |

Note: * In Belgium, the European Commission’s Best Practices Guidelines on merger control are applied by analogy until the Belgium Competition Authority adopts specific guidelines (Belgian Competition Authority, 2023[14]).

** South Africa’s substantive guidelines refer only to the evaluation of public interest grounds in merger review.

4.2.2. Horizontal versus non-horizontal mergers

There was a mixed approach to the treatment of horizontal and non-horizontal mergers in the guidelines. Most jurisdictions (Canada, France and Kenya) combine both horizontal and non-horizontal issues in their guidelines, while the European Union has issued separate guidelines. The Philippine guidelines focus on horizontal mergers. However, it is stated that the “underlying principles can also be applied to non-horizontal mergers” and that the PCC intends to release guidance on non-horizontal mergers in the future (Philippine Competition Commission, 2018, p. 6[15]). The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines expressly indicates that they apply to horizontal and non-horizontal mergers, although it is not explained how the competition assessment varies in each type of transaction.

Table 4.3. Horizontal and non-horizontal mergers

|

Jurisdiction |

Horizontal |

Non-Horizontal |

Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

|||

|

Canada |

✓ |

||

|

European Union |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

France |

✓ |

||

|

Non-OECD countries |

|||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

||

|

Philippines |

✓ |

||

4.2.3. Common features of guidelines reviewed

More specifically, the following elements have been included in the guidelines of the selected jurisdictions, as summarised in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4. Summary of common features in merger guidelines in selected jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction |

Introductory statements |

Definition of merger |

Notification thresholds |

Market definition |

Merger test and factors |

Competition effects |

Remedies |

Use of examples |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unilateral |

Co-ordinated |

||||||||

|

OECD countries |

|||||||||

|

Canada |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓ |

|

European Union |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓ |

|

France |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Non-OECD countries |

|||||||||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Philippines |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Note: * Refer to separate guidelines.

Introductory statements

Most guidelines include introductory words that set the scene for the application of merger law in the particular jurisdiction. Such introductory statements include the objective of the guidelines, as well as the way in which they have been developed.

For example, the Canadian Merger Enforcement Guidelines state that they aim at providing “general direction on its [the Competition Bureau] analytical approach to merger review” (Competition Bureau, 2011, p. 1[16]). The Merger Control Guidelines of the Autorité de la concurrence affirm that they intend to provide “guidance on the merger control procedures and practice” of the authority (Autorité de la concurrence, 2020, p. 1[17]). The Kenyan Merger Guidelines highlights that they intend to “improve the business regulatory framework and enhance business environment” (Competition Authority of Kenya, n.d., p. 2[18])

In younger regimes, the introductory part usually also includes an emphasis on the rationale for merger review. For instance, the Philippines explains the rationale for merger review at the beginning of its substantive guidelines (Philippine Competition Commission, 2018, p. 2[15]).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines include an introduction outlining their objectives, which include clarify merger control rules, providing greater transparency and fairness to businesses, as well as improve merger control process. The draft guidelines also highlight the importance of merger control in general.

Definition of merger

Most guidelines explain what is considered a merger for the purpose of merger control, spelling out the more general definitions provided for in the legislation, for instance the difference between a merger, acquisition and consolidation and the types of share acquisitions, asset sales and participating interests. The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines also include a section explaining the concept of mergers, in line with Act No. 2015-36 of 15 September 2015.

Notification thresholds

Most guidelines explain the notification thresholds that are applicable in the relevant jurisdiction. The way in which such thresholds are treated in guidelines can differ considerably, mostly due to the different nature of the respective merger systems (compulsory or voluntary merger regime).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines refer to the two existing notification thresholds, as provided for by Act No. 2015-36 of 15 September 2015.

Market definition

Given the central role of market definition in most merger cases, many guidelines elaborate on the role of market definition, the way in which markets are defined and how they may change the outcome of a merger review. While many merger guidelines discuss market definition in detail (e.g., Canada and France), some refer to separate guidelines that deal with market definition (e.g., the EU and Kenya). All define markets by reference to product and geographic dimensions and refer to the hypothetical monopolist test to define markets.

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines include a short description of market definition, without detailing how the competition authorities assess this in practice. Providing further elements in this regard could be useful for increasing legal certainty and ensure that market players understand how competition law in interpreted and applied. This is particularly relevant considering that one of the notification thresholds is based on a market share test, which can be challenging for merging parties and lead to considerable uncertainty about whether the transaction is notifiable, as indicated in the Peer Review (OECD, 2022, p. 104[1]).

Applicable substantive merger test and relevant factors

Most merger guidelines contain an explanation of the relevant merger test and the factors that will be considered in determining the competitive effects of a merger. For instance, relevant factors include the market structure, the market position of market players, the availability of substitutes and their ability to access the market, switching costs, and other barriers to entry. Most jurisdictions use a “with and without” (or “counterfactual”) test to determine whether the relevant merger test is met. This means that an analysis is conducted of a situation with and without the merger.

As highlighted in the Peer Review, currently the competitive assessment of mergers in Tunisia is based mostly on a legal analysis rather than on an economic assessment of the effects of the merger, being essentially limited to defining market shares and the effects of the merger on the structure of the market. In this regard, the Peer Review recommended the introduction of a substantial lessening of competition (SLC) test for merger analysis, in addition to a test based on creating or increasing a dominant position (OECD, 2022[1]). The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines mention that the assessment carried out by the Competition Council considers the impact of the transaction on competition, while the DGCEE rests on whether the merger is likely to create or strengthen a dominant position in the relevant market or a substantial part of it.

Competition effects

Most jurisdictions identify the key competition concerns with mergers as unilateral (called “non-coordinated” in some jurisdictions) or co-ordinated effects. Unilateral effects arise where the merged entity can exercise unilateral market power with adverse effects on competition and co-ordinated effects arise where, as a result of the merger, co-ordination among firms is easier, more likely, more stable or more effective.

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines mention that the Competition Council considers competition effects, including unilateral and co-ordinated effects. However, as mentioned above, the competition assessment carried out by the DGCEE is based on structural considerations and therefore do not include competition effects.

Remedies

All guidelines analysed in this report deal with merger remedies, although the level of details can vary significantly. Some competition authorities have published separate guidelines to elaborate on merger remedies. For example, this is the case in Canada (Competition Bureau, 2006[19]) and the European Union (European Commission, 2008[20]). In other regimes (such as France and Kenya), the merger guidelines explain the concepts of structural and behavioural remedies, as well as how remedies can be procedurally implemented. In the Philippines, the possible structural and behavioural remedies are outlined relatively briefly in the guidelines.

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines mention that mergers can be authorised subject to conditions, which can be structural or behavioural. They also indicate the conditions remedies must fulfil (e.g. effective, clear, quickly implementable, capable of being monitored and proportionate to addressing the competitive harm). It is also stated that structural remedies are preferable to behavioural remedies. However, these elements are only briefly discussed and could be further described.

Use of examples

Including case and/or hypothetical examples in merger guidelines can be useful. Such examples can illustrate certain concepts or more concrete on how a merger would be assessed.

For instance, the Merger Control Guidelines of the Autorité de la concurrence present several examples, including administrative and judicial caselaw, to illustrate how the topics have been addressed in practice in previous cases (Autorité de la concurrence, 2020[17]).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines only include examples related to previous cases where the Competition Council has issued an opinion either to block the transaction or approve it subject to remedies. However, the document does not indicate the final decision of the DGCEE, nor provide details on the analysis carried out by the Competition Council. Additional and more detailed examples, either hypothetical or practical could be particularly relevant to illustrate how the competition authorities have interpreted and applied competition law.

4.2.4. Less common but helpful features of guidelines reviewed

The review revealed less common but helpful features in the guidelines in the selected jurisdictions which are worth mentioning. A summary of these features is set out in Table 4.5.

Table 4.5. Less common but helpful features of merger guidelines

|

Jurisdiction |

Legally non-binding nature |

Terminology |

Safe harbours |

Joint ventures |

Ancillary restraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

|||||

|

Canada |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

European Union |

Implied |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

|

|

France |

Implied |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Non-OECD countries |

|||||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

✓ |

✓* |

||

|

Philippines |

Implied |

✓* |

✓ |

||

Note: * Refer to separate guidelines.

Legally non-binding nature of guidelines

Competition authorities may wish to consider making express statements about the legally non-binding nature of guidelines on courts, although it is implied in some jurisdictions.

For example, both the EU Guidelines on horizontal and non-horizontal mergers indicate that the Commission’s interpretation of the Merger Regulation “is without prejudice to the interpretation which may be given by the Court of Justice or the Court of First Instance of the European Communities” (European Commission, 2008[21]; European Commission, 2008[22]). That said, as mentioned in section 3.3.1, in some circumstances, guidelines can have legal effect and may be binding on the issuing competition authority – unless stated otherwise.

For instance, the Merger Control Guidelines of the Autorité de la concurrence recognise that “the Autorité commits to apply the guidelines whenever it examines a merger, provided that there are no circumstances specific to the merger or any considerations in the general interest that would justify an exemption from them” (Autorité de la concurrence, 2020, p. 1[17]).

The Kenyan Merger Guidelines stress that they “do not have the force of law and is not binding on the Tribunal or any court of law” (Competition Authority of Kenya, n.d.[18]).

The Philippines does not expressly affirm that the guidelines are non-binding but does state that the PCC will apply the guidelines “flexibly, or where appropriate, deviate therefrom” (Philippine Competition Commission, 2018, p. 1[15]).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines do not mention their non-binding nature, which could be relevant considering that the issuance of guidelines is not a common administrative practice.

Terminology

Some guidelines include explanations of relevant terminology, usually in the form of a glossary. This assists the business community and can be particularly useful in jurisdictions where merger review is new or less effective. For example, in Kenya, merger guidelines present a glossary of relevant terms (Competition Authority of Kenya, n.d., p. 60[18]).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines do not include a session with relevant terms. This could increase the understanding of merger control regime.

Safe harbours

Inclusion of any applicable “safe harbours” can be a particularly useful tool to assist businesses to understand when their mergers may not give rise to competition concerns. The OECD Recommendation on Merger Review recommends the adoption of procedures to ensure that merger that do not raise material competitive concerns are subject to expedited review and clearance (OECD, 2005[11]).

For example, the European Commission states that a horizontal merger where the market share of the undertakings concerned does not exceed 25% in the common market (or a substantial part of it) may be presumed to be compatible with the common market. Moreover, the Commission is unlikely to identify horizontal competition concerns in a market with a post-merger HHI below 1 000 (European Commission, 2008[21]).2 As regards non-horizontal mergers, the European Commission indicates that it is unlikely to find concern in non-horizontal mergers where the market share post-merger of the new entity in each of the markets concerned is below 30% and the post-merger HHI is below 2 000 (European Commission, 2008[22]).3

The Canadian Merger Enforcement Guidelines also establish particular thresholds to distinguish mergers that are unlikely to have anti-competitive effects from those that require an in-depth analysis. For instance, mergers leading to market share of the merged firm less than 35% generally will not be challenged based on a concern related to the unilateral exercise of market power. In addition, the competition authority generally will not challenge a merger based on a concern related to a co-ordinated exercise of market power when the post-merger market share of the four largest players in the market would be less than 65% or the post-merger market share of the merged entity would be less than 10% (Competition Bureau, 2011, pp. 18-19[16]).

The Peer Review recommended that Tunisia should create a simplified procedure for notification of simpler mergers that do not raise competition concerns (OECD, 2022, p. 170[1]). The merger guidelines could thus address this issue by establishing “safe harbours” to indicate which cases would not be likely to raise competition concerns, possibly be subject to a simplified procedure. Nevertheless, this is not the case of the draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines.

Joint ventures

The approach to assessing joint ventures may be an area of great diversity among competition authorities. This diversity stems from differences in what relevant legal frameworks consider constitutes a transaction. Considering the differences in legal definitions of a transaction, including a joint venture, it may be helpful for a competition authority to state clearly its position on how to assess joint ventures under the merger regime in its guidelines. For instance, Kenya and the Philippines have developed separate guidelines on notification of joint ventures (Competition Authority of Kenya, 2021[23]; Philippine Competition Commission, 2018[24]).

As indicated in the Peer Review, Tunisian Competition Act does not explicitly define whether the creation of a joint venture is considered a merger, although the competition authorities indicate that this is the case if they perform on a lasting basis an autonomous economic entity (OECD, 2022[1]). The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines clarify that the creation of a joint venture performing on a lasting basis all the functions of an autonomous economic entity is considered a merger, which might provide business with greater certainty whether their transactions are subject to a notification requirement.

Ancillary restraints

Some of the merger guidelines reviewed also focus on ancillary restraints (i.e., the restrictions directly related and necessary to the implementation of the transaction).

The European Commission has separate guidelines on ancillary restraints (European Commission, 2005[25]), while the Autorité de la concurrence has included the topic in the same document (Autorité de la concurrence, 2020, pp. 224-226[17]). In the Philippines, ancillary restraints are briefly mentioned in the merger guidelines and appear to be covered by the merger review (Philippine Competition Commission, 2018, p. 7[15]).

The draft Tunisian Merger Guidelines have no reference to ancillary restraints.

Key takeaways – Merger control

Merger review helps avoid anti-competitive economic concentrations and is a key component of competition regimes. Merger guidelines play a crucial role in ensuring an effective merger control regime and can be particularly useful in younger competition regimes, where the competition culture is still emerging.

The Tunisian competition law framework regarding merger review has a series of limitations, including a very high turnover-based notification threshold and the absence of two-phase and simplified merger control regime, as well as the lack of merger notification forms.

While Tunisia is currently seeking to implement merger guidelines, the draft submitted to the OECD has some shortcomings, in particular:

There is no substantial guidance as regards market definition and the setting of remedies.

While it applies to horizontal and non-horizontal mergers, there are not elements on how the competition assessment varies in each type of transaction.

The competition assessment carried out by the Competition Council considers the impact of the transaction on competition, while the DGCEE focuses on whether the merger is likely to create or strengthen a dominant position in the relevant market or a substantial part of it.

There are only few and brief examples and reference to previous cases.

It does not state the legally non-binding nature of the guidelines on courts.

There are no “safe harbours” to indicate which cases are unlikely to raise competition concerns.

Notes

← 1. This is supported by the comparative Table A A.2.

← 2. The Commission is also unlikely to identify horizontal competition concerns in a merger with a post-merger HHI between 1 000 and 2 000 and a delta below 250, or a merger with a post-merger HHI above 2 000 and a delta below 150, except where special circumstances such as, for instance, one or more of the following factors are present: (a) a merger involves a potential entrant or a recent entrant with a small market share; (b) one of more merging parties are important innovators in ways not reflected in market shares; (c) there are significant cross-shareholdings among the market participants; (d) one of the merging firms is a maverick firm with a high likelihood of disrupting coordinated conduct; (e) indications of past or ongoing coordination, or facilitating practices, are present; (f) one of the merging parties has a pre-merger market share of 50 % of more (European Commission, 2008[21]).

← 3. The Commission will not extensively investigate such mergers, except where special circumstances such as, for instance, one or more of the following factors are present: (a) a merger involves a company that is likely to expand significantly in the near future, e.g. because of a recent innovation; (b) there are significant cross-shareholdings or cross-directorships among the market participants; (c) one of the merging firms is a firm with a high likelihood of disrupting coordinated conduct; (d) indications of past or ongoing coordination, or facilitating practices, are present (European Commission, 2008[22]).