While leniency programmes can be a powerful instrument to detect cartels and support competition enforcement, jurisdictions must provide the adequate incentives for companies to apply for leniency, including a high risk of detection and dissuasive sanctions. The Tunisian competition law follows international standards regarding leniency programmes, but no application has ever been submitted to date. Adopting leniency guidelines can help Tunisia to make its leniency programme more effective. This section presents an overview of leniency programme guidelines in selected jurisdictions, aiming to help Tunisian authorities to implement their own guidelines.

The Role of Guidelines in Fostering Competition Policy in Tunisia

6. Leniency programme

Abstract

6.1. Overview of leniency regime in Tunisia

A leniency programme was established in Tunisia in 2003. Act 2015-36, particularly Article 26, updated the legal framework and currently governs the topic, which covers cartels and any type of anti-competitive agreement. In addition, Government Decree No. 2017-252 of 8 February 2017 was issued to detail the procedures for leniency applications. However, the Tunisian competition authorities have not received any leniency application to date.

Firms’ incentives to apply for leniency rely on their perception of the threat of being caught and heavily sanctioned (OECD, 2023, p. 14[31]). For leniency programme to work, there must be a high risk of detection and significant sanctions, which does not seem the case in Tunisia. As indicated in the Peer Review, anti-cartel enforcement activities in Tunisia are still low, and some cartel decisions were handed without a fine being imposed, significantly reducing their deterrent effect (OECD, 2022[1]).

Therefore, changes in the regulatory framework alone will not ensure that leniency programme will be effective. Improving the leniency programme should be carried out in parallel with more enforcement decisions and higher sanctions. Thus, it is necessary that Tunisian authorities also engage further in pro-active detection methods, including the use of economics (e.g. collusion factors, industry studies and market screening), use of information from past cases (also from other jurisdictions), industry monitoring (e.g. press and internet, career tracking of industry managers and regular contact with industry representatives), co-operation between agencies (national or foreign competition authorities or other agencies) and technology-led screens (e.g. structural screens and behavioural screens) (OECD, 2023[31]).

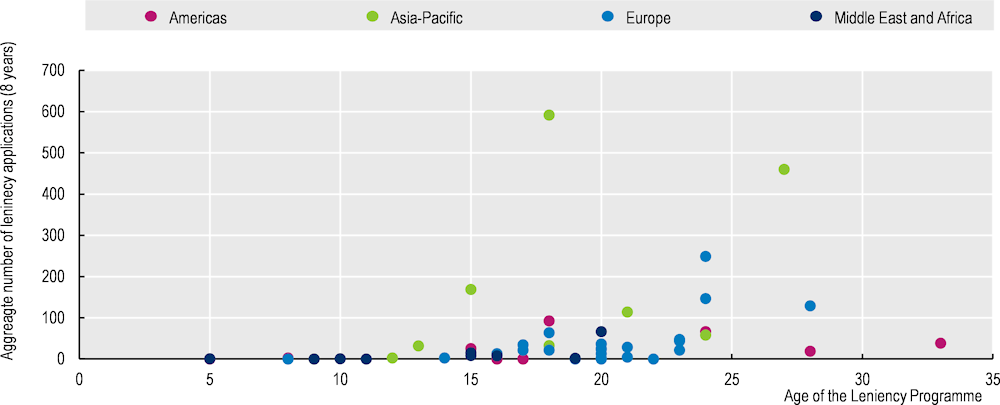

Figure 6.1. Total Leniency applications for the period 2015-2022 against the age of the leniency programme, by region

Note: Data based on the 54 jurisdictions in the OECD CompStats database that provided comparable data for all eight years and have a leniency programme.

Source: OECD CompStats database

Leniency programmes may take some time to become effective and established. Evidence from the OECD CompStats database show that there is a positive correlation between the number of leniency applications and the age of the leniency programme. Figure 6.1 illustrates this correlation suggesting the rather unusual situation of the Tunisian leniency programme that has 20 years of existence. Despite having the oldest programme in the Middle East and Africa region, Tunisia – with no application so far – performs well below the regional average of twelve leniency applications per year recorded over the 2015-2022 period (OECD, 2023[32]).

Generally speaking, Tunisia follows international standards regarding leniency programmes. For instance, leniency can ensure total or partial immunity from sanctions, depending on the applicant’s position in relation to other applicants and on whether the competition authority is already aware of the infringement. Government Decree No. 2017-252 also introduced some procedural elements, in line with the practices of other jurisdictions. These include how the application can be submitted (in writing or orally), the information that must be presented and the possibility to request a marker.

In addition to provide the right incentives (e.g. pro-active detection tools and dissuasive fines), the success of a leniency programme relies on transparency and predictability. Indeed, transparency enables firms to anticipate the benefits of coming forward. Likewise, companies must be aware of the existence and the features of the leniency programme, particularly on what they may expect in return for their co-operation (OECD, 2023, p. 23[31]). In this regard, the OECD Recommendation concerning Effective Action against Hard Core Cartels assert that, to ensure effective leniency programmes, jurisdictions must provide clarity on the rules and procedures governing leniency programmes and the related benefits, as well as establish clear standards for the type and quality of information that qualifies for leniency (OECD, 2019[33]).

Article 1 of Government Decree No. 2017-252 provides that leniency applications can be submitted to either to the competition department within the Ministry of Trade or to the general rapporteur of the Competition Council. This raises significant concerns on whether confidentiality can be ensured, which is a key element of successful leniency programmes, as mentioned above. For instance, jurisdictions usually indicate specific point of contact that interested parties should approach to submit a leniency application. The uncertainty on confidentiality is even worse since neither Act 2015-36 nor Government Decree No. 2017-252 have provisions in this regard.

Moreover, Article 26 of Act 2015-36 states that before granting leniency, the Competition Council must consult the government Commissioner. This calls into question the independence of the Competition Council to enforce its leniency programme.

The procedures introduced by Government Decree No. 2017-252 are also limited and do not cover all the main aspects of leniency applications, as highlighted below. Once again, clarity on benefits, requirements and procedures are crucial for well-functioning leniency programmes.

6.2. Leniency programme guidelines

Leniency programmes guidelines can be an effective instrument for providing transparency and predictability, increasing incentives for businesses to apply for a leniency programme. For instance, such guidelines may outline the benefits, the requirements and the procedure for a leniency application.

This section considers the elements commonly covered in leniency programme guidelines by comparing guidelines published in the selected jurisdictions, which can be used by Tunisian competition authorities when developing their own leniency guidelines.

6.2.1. Overview of guidelines reviewed

The project team has assessed the leniency programme guidelines of the selected jurisdictions, listed in Table A A.3 and summarised in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1. Overview of guidelines reviewed

|

Jurisdiction |

Guidelines |

Date of guidelines |

|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

||

|

Belgium |

✓ |

2022 |

|

Canada |

✓ |

2019 |

|

European Union |

✓ |

2022 |

|

France |

✓ |

2015 |

|

Non-OECD countries |

||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

2017 |

|

Philippines |

✓ |

2019 |

|

South Africa |

✓ |

2008 |

6.2.2. Common features of guidelines reviewed

The following elements have been included in the guidelines of the selected jurisdictions, as summarised in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2. Summary of common features in leniency programme guidelines in selected jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction |

Introductory statements |

Violations covered |

Eligibility criteria |

Conditions |

Benefits |

Procedure |

Confidentiality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

|||||||

|

Belgium |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Canada* |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

European Union |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

France |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Non-OECD countries |

|||||||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Philippines |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

South Africa |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

Note: * Canada differentiates between immunity and leniency, the latter referring to full immunity and the former to partial immunity (i.e. reduction in sanctions).

Introductory statements

Most guidelines start by introductory remarks, usually explaining the objectives of the guidelines, how they have been developed and/or the importance of leniency programmes.

For instance, the European Commission Guidelines state that they aim at clarifying “certain concepts and current practices when the Commission applies the Leniency Notice in order to ensure a high degree of transparency and predictability”, as well as to “increase awareness of the additional protections and benefits enjoyed by leniency applicants, beyond the ones described in the Leniency Notice” (European Commission, 2022[34]).

In its introduction, the Belgian Guidelines describe what the leniency programme is and its legal framework, also highlighting that the Guidelines seek to provide legal certainty to the individuals and companies concerned (Autorité belge de la Concurrence, 2020[35]). The French Guidelines starts by presenting the legal framework of the leniency programme and the previous guidelines adopted in this regard, as well as describing the process of the most recent review that led to the current Guidelines (Autorité de la concurrence, 2015[36]).

The Kenyan Guidelines indicate that they were elaborated to “inform parties (…), legal practitioners, and the general public on how the Authority will handle application for leniency” (Competition Authority of Kenya, 2017[37]). Likewise, the Philippine Guidelines provides that they “serve to aid the public in understanding the concept of leniency, and to provide a transparent process in applying for the benefits offered under the program” (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019[38]).

The introductory part may also include an explanation of the rationale for the leniency programme. For instance, the Canadian Guidelines recognise the importance of leniency to uncover and stop anti-competitive activity and to deter others from engaging in similar behaviour (Competition Bureau, 2019[39]).

Violations covered by the leniency programme

All guidelines assessed expressly indicate to which competition infringements the leniency programme applies. While most leniency programme applies only to hard-core cartels, some guidelines also cover other infringements.

For instance, the Canadian Guidelines assert that immunity also applies to deceptive marketing offences (Competition Bureau, 2019, p. 7[39]). According to the European Commission Guidelines, leniency can also involve less traditional cartels, including practices such as discussion of price-setting factors on weekly reference prices, exchanges of precise information on trading positions and attempts to influence benchmark interest rates, buyer cartels and co-ordination to restrict competition on technical development (European Commission, 2022, pp. 1-2[34]). The French Guidelines state that besides hard-core cartels the leniency programme also applies to any other similar anti-competitive behaviour among competitors, particularly co-ordinated practices established through actors in a vertical relationship (hub and spoke arrangements) (Autorité de la concurrence, 2015, p. 2[36]).

Who can benefit from the leniency programme (eligibility criteria)

Most guidelines indicate who can apply for leniency, which usually is the undertakings or associations of undertakings involved in a cartel (as long as they fulfil certain conditions, as mentioned below). Some guidelines provide that individuals involved in a cartel can also apply for leniency, such as in Belgium, Canada and the Philippines. The Kenyan Guidelines establish that leniency may also cover the applicant’s directors and employees, but they are not clear whether individuals themselves can apply for leniency (Competition Authority of Kenya, 2017, p. 3[37]). The South African and European Commission guidelines indicate that individuals cannot apply for leniency, but they can be qualified as whistle blowers. However, the European Commission Guidelines clarify that EU Member States have to ensure that employees of immunity applicants of national competition authorities and the Commission are protected from sanctions at Member State level, provided that they co-operate with the relevant authorities (European Commission, 2022, p. 12[34]).

The European Commission guidelines also state that facilitators (i.e. “an undertaking that was not active on the cartelised market but which otherwise actively aided the objectives of the infringement”) can apply for leniency (European Commission, 2022, p. 3[34]).

Moreover, most guidelines indicate that market players that have coerced other undertakings to join or remain in the cartel are not eligible for full immunity (Belgium, Canada, EC, France and the Philippines), although they can still benefit of reduction of fines. The Philippine Guidelines further point out that the leader in or the originator of the anti-competitive practice is also not eligible for applying for full immunity (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019, p. 21[38]). The Kenyan Guidelines provide that the leniency applicant must not have coerced others or instigated others to operationalise the agreement, suggesting that this also include partial leniency (Competition Authority of Kenya, 2017, p. 4[37]).

Conditions

All guidelines establish which are the conditions that an applicant must meet to qualify for leniency. The following elements are present in all selected guidelines: (i) the applicant must end its involvement in the cartel immediately following its application (unless otherwise requested by the competition authority, when necessary to ensure the integrity of the investigation); (ii) the applicant must ensure full and expeditious co-operation to the competition authority concerning the reported anti-competitive practices, which include providing all information and evidence of which it is aware or becomes aware and respond promptly to the competition authority requests; (iii) the applicant must not destroy, falsify or conceal information or evidence related to the reported infringement; (iv) the applicant must not disclose its application and its content (unless otherwise agreed with the competition authority).

In addition to these general conditions, specific requirements must be fulfilled for an applicant to obtain full or partial immunity (see below).

Benefits from the leniency programme

As mentioned above, according to the OECD Recommendation concerning Effective Action against Hard Core Cartels, an effective leniency programme relies on the establishment of clear benefits for applicants (OECD, 2019[33]). Accordingly, all guidelines specify what are the benefits that leniency applicants can obtain if they comply with all conditions.

Most guidelines provide for full immunity from any sanctions or reduction in sanctions, depending on the applicant’s position in relation to other applicants and on whether the competition authority is already aware of the infringement. Full immunity is usually granted to the first entity that discloses its participation in a cartel and provide the competition authority information and evidence when the authority is unaware of the anti-competitive practice or, when the authority is aware of the offence, it has insufficient evidence to prosecute the cartel.

Some of guidelines (e.g. from Canada, the European Commission, France, Kenya and the Philippines) state that full immunity protects employees of leniency companies in criminal prosecutions, while the Belgian Guidelines are silent in this regard. On the other hand, the South African guidelines expressly indicate that full immunity does not protect the leniency applicant from criminal liability resulting from its participation in a cartel infringement (Competition Commission of South Africa, 2008, p. 5[40]).1

Most of guidelines also provide for partial immunity (i.e. a reduction in penalty) when the leniency applicants are not qualified for full immunity but contribute with additional evidence. Leniency guidelines usually set “leniency bands” with different reduction ranges, taking into account the time of application and the added value represented by the additional evidence presented. For example, this is the case of the guidelines from Belgium, the European Commission, France, Kenya and the Philippines. The Canadian guidelines establish a single band, i.e. a maximum reduction of 50% (Competition Bureau, 2019, p. 30[39]).

According to the South African guidelines, the leniency programme only benefits the “first to the door”, although partial immunity can be granted to subsequent applicants through other tools (Competition Commission of South Africa, 2008, p. 5[40]).

Procedure

All guidelines provide information on the procedure to be followed during a leniency application. The steps of the leniency procedure are similar across all guidelines, including initial contact, the marker request, the submission of an application, the grant of conditional leniency and the final decision.

All guidelines highlight that applicants can informally contact the competition authority without disclosing their identity to obtain general information and clarity about the leniency programme (e.g. whether it applies to a specific behaviour).

Some guidelines (e.g. Belgium, Canada, the European Commission and the Philippines) also indicate the possibility of making a hypothetical application to establish whether leniency is available for the specific cartel the potential applicant is involved in. For this purpose, the potential applicant must provide the competition authority with the products concerned, the geographic scope and the duration of the infringement, but it is not required to disclose its identity.

In addition, all guidelines establish the possibility to request a marker, which protects the applicant’s place in the line of applications with respect to a specific infringement, allowing it to gather the necessary information and evidence to qualify for leniency during a period. While most guidelines state that the competition authority will determine the period to perfect the application on a case-by-case basis, others set a more or less precise period.2

All guidelines also mention that the leniency applicant must present to the competition authority the relevant information and evidence at its disposal, although some guidelines provide more details in this regard. For example, the Belgian Guidelines indicate that the application must submit a leniency statement with the following information: (i) the name and address of the applicant, as well as the names and positions of the individuals within the applicant who were involved in the cartel; (ii) the name and address of other undertakings, association of undertakings or individuals involved in the cartel; (iii) products or services involved; (iii) geographic scope; (iv) duration; (v) estimate of the market volume; (vi) locations and times at which exchanges related to the cartel took place, along with content of these exchanges and the participants; (vii) the nature of the cartel; (viii) any relevant explanations concerning the provided evidence; (ix) information about any leniency applications related to the cartel in other jurisdictions; and (x) the evidence supporting these elements (Autorité belge de la Concurrence, 2020, p. 7[35]). Moreover, the Philippine Guidelines exemplify evidence that may be relevant, such as emails, letters and minutes of meetings (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019, p. 12[38]).

Applications can usually be made in writing or orally. Oral applications are commonly transcribed by the competition authority. Only the Philippine guidelines do not mention oral applications. The guidelines are also clear regarding the point of contact in the competition authority (usually a specific position), which is relevant to ensure confidentiality.

After receiving the leniency application, the competition authority assesses the request and grants interim or conditional leniency if all conditions are met. At the end of the process, if the applicant has complied with all required conditions, the conditional leniency is converted into final leniency. Conditional leniency can be revoked if the applicant violates its obligations.

Confidentiality

All guidelines contain provisions related to confidentiality, which is an important feature required to ensure the success of leniency programmes. Indeed, according to the OECD Recommendation concerning Effective Action against Hard Core Cartels, jurisdictions should provide appropriate confidentiality protection to leniency applicants (OECD, 2019[33]), in order to guarantee the right balance between public and private enforcement and preserve the incentives to apply for leniency (OECD, 2023, p. 15[31]).

Nevertheless, the scope of confidentiality varies substantially across guidelines. Some of them are more proscriptive, clearly referring that leniency documents are protected from the complainant and interested parties.

According to the Belgian Guidelines, for example, the complainant and interest third parties do not have access to leniency applications, annexes and decisions. Other investigated parties can only have access to leniency documents to exercise their rights of defence (Autorité belge de la Concurrence, 2020, p. 10[35]).

According to the European Commission Guidelines, leniency submissions (i.e. applications and corporate statements) are protected from disclosure in civil litigation, including discovery, through the use of e-Leniency (an online platform developed by the Commission). Moreover, the Guidelines also state that the Commission expects leniency applicants to provide a full waiver of confidentiality for allowing the Commission to share leniency documents with other competition authorities (European Commission, 2022[34]).

The Kenyan Guidelines affirm that the identity of the leniency applicant is kept confidential during the investigation and also after a decision is taken. They also indicate that any leniency applicant may request for confidentiality of the whole or any part of the material provided to the competition authority (Competition Authority of Kenya, 2017, pp. 6-7[37]).

On the other hand, other guidelines are broader and less detailed. For example, the French Guidelines are not very precise, only indicating that the Autorité de la concurrence preserves, within the limits of its national and EU obligations, the confidentiality of the leniency applicants’ identity during the procedure until the sending of the statement of objections (Autorité de la concurrence, 2015, p. 9[36]).

Furthermore, the South African Guidelines provide that the Competition Commission shall ensure confidentiality on all information, evidence and documents submitted by the lenient applicants throughout the process. Disclosure of any information provided by the leniency applicants prior to immunity being granted depends on the consent of the applicants (Competition Commission of South Africa, 2008[40]).

According to the Philippine Guidelines, the identity of the leniency applicants is confidential and is not disclosed unless the PCC decides that their testimony or sworn statement is required for the administrative or civil case filed by the competition authority (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019, p. 24[38]).

In Canada, the leniency Guidelines provides that the identity of immunity or leniency applicants or any information provided by them are treated as confidential by the Competition Bureau. However, the guidelines list some exceptions to the confidentiality, including when disclosure is required by law or is necessary to obtain or maintain the validity of a judicial authorisation for the exercise of investigative powers, as well as when the party has agreed to disclosure (Competition Bureau, 2019, pp. 41-42[39]).

6.2.3. Less common but helpful features of guidelines reviewed

The review revealed less common but helpful features in the guidelines in the selected jurisdictions which are worth mentioning. A summary of these features is set out in Table 6.3.

Table 6.3. Less common but helpful features of leniency programme guidelines

|

Jurisdiction |

Legally non-binding nature |

Terminology |

Consequences for civil liability |

Checklist and template documents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OECD countries |

||||

|

Belgium |

✓ |

|||

|

Canada |

✓ |

✓* |

Implied |

✓ |

|

European Union |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

France |

✓ |

|||

|

Non-OECD countries |

||||

|

Kenya |

✓ |

|||

|

Philippines |

Implied |

✓ |

||

|

South Africa |

✓ |

|||

Note: * The Canadian Guidelines do not include a glossary, but clarify some terms in the introduction.

Legally non-binding nature of guidelines

Like merger guidelines, competition authorities may also wish to expressly indicate that the leniency guidelines are legally not binding on courts, even if this is implied in some jurisdictions.

For instance, Canadian Guidelines indicate that they “do not provide legal advice” (Competition Bureau, 2019, p. 7[39]). Likewise, the European Commission Guidelines specify that they “are not intended to constitute a statement of the law and they are without prejudice to the interpretation of Article 101 and the Leniency Notice by the European Courts” (European Commission, 2022, p. 1[34]).

The Philippine Guidelines state that the Guidelines are “not a substitute for the PCA [Philippine Competition Act] and the Leniency Rules” (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019, p. 3[38]).

Terminology

Certain guidelines, such as in Belgium and Kenya, include a glossary with the definition of key technical terms, which can help enhance understanding of the leniency programme. A glossary can be particularly useful in jurisdictions where leniency is new or less effective.

While not having a formal glossary, the Canadian Guidelines explain the meaning of some terms, such as “party”, “immunity applicant” and “lenient applicant” (Competition Bureau, 2019, p. 7[39]).

Consequences for civil liability

Some guidelines mention the consequences of leniency for civil liability. A few guidelines (e.g. France and South Africa) specify that immunity granted through leniency does not protect the applicant from civil liability resulting from its participation in a cartel.

The European Guidelines explain that the leniency programme protects applicants against exposure to civil damages. In particular, immunity recipients are only jointly and severally liable to their direct and indirect customers and to other cartel victims if full compensation cannot be obtained from the other cartelists (European Commission, 2022, p. 12[34]).

On the other hand, the Philippine Guidelines indicate that civil actions initiated by the PCC on behalf of affected parties and third parties may be avoided or reduced through the leniency programme (Philippine Competition Commission, 2019, p. 8[38]).

The Canadian Guidelines do not expressly mention that applicants are not protected from civil damages actions, but they state that the Competition Bureau has no interest in penalising applicants for early disclosure or co-operation in a civil action (Competition Bureau, 2019, p. 43[39]).

Checklist and template documents

The Canadian Guidelines provide for a checklist to guide applicants as regards the information that they must provide to the competition authority. For instance, this refers to the parties, the product, the industry, the market, the conduct and its impact. The Canadian guidelines also include some template documents, which may be useful for helping leniency applications and providing further transparency to potential leniency applicants.

Key takeaways – Leniency programme

While leniency programmes can be a powerful instrument to detect cartels and support competition enforcement, jurisdictions must provide the adequate incentives for companies to apply for leniency, including a high risk of detection and dissuasive sanctions.

Transparency and predictability are crucial for a successful leniency programme.

The Tunisian competition law follows international standards regarding leniency programmes, but no application has ever been submitted to date.

Adopting leniency guidelines can help Tunisia to make its leniency programme more effective.

When developing leniency guidelines, several elements should be taken into account, including who is the point of contact in the competition authority that interested parties should approach to submit an application, the possibility to request a marker and the information and evidence that should be presented.

Notes

← 1. It should be noted that only bid rigging is criminalised in Belgium, while the other selected jurisdictions criminalise hard core cartels in general (OECD, 2020[47]).

← 2. For instance, the Canadian and Kenyan guidelines indicate 30 days, while the Philippine guidelines set 28 days (Competition Bureau, 2019[39]; Competition Authority of Kenya, 2017, p. 7[37]). The European Commission Guidelines mention that in recent cases it has granted a one-month period, although this may be longer in certain cases (European Commission, 2022, p. 6[34]).