As of October 2022, Central Asian countries had predominantly taken monetary policy action to counteract currency depreciation and inflation, and measures to ensure food security. Little policy action was observed from Turkmenistan, though it is arguably the least affected country of the region. More noticeably, all countries of the region have shown an interest in developing new trade routes circumventing Russia westwards through the Middle Corridor, eastwards through China, and southwards through Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

Weathering Economic Storms in Central Asia

Policy responses in Central Asia

Monetary policy across Central Asia has proved effective in stabilising exchanges rates, but high inflation remains an issue

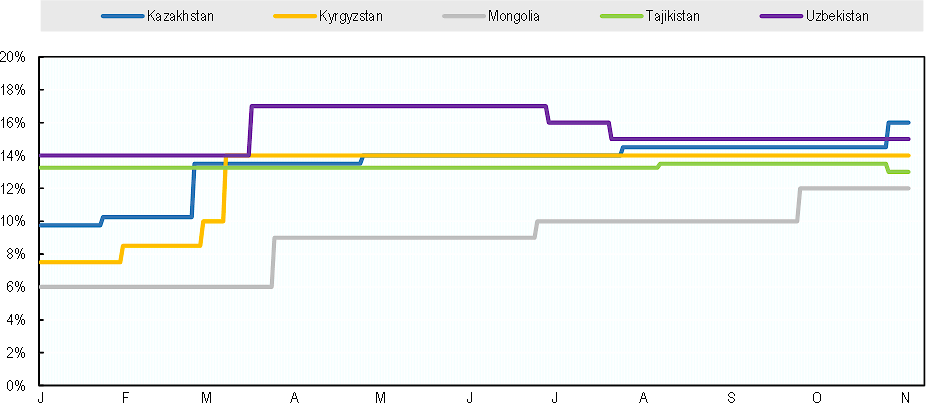

So far, the war’s most important negative impact across Central Asia has mainly been in terms of inflation. In the first half of 2022, central banks in the region accelerated the monetary tightening initiated in 2021 to stabilise exchange rates and contain rising prices. Since February all national banks of the region, except for Turkmenistan incrementally increased their base rates (Figure 17). Uzbekistan has decreased its rate twice in June and July to a level still slightly above the pre-war one. Tajikistan also decreased its base rate early November, below its pre-war level. Since imported inflation accounts for a large part of the price dynamic, this monetary tightening has not yet had an impact on inflation, but it has affected financial conditions, which might have a negative impact in the longer-run especially on SMEs’ access to finance and debt servicing costs (EBRD, 2022[45]).

Figure 17. Evolution of policy rates in Central Asia countries (2022)

Source: National Bank of Kyrgyzstan, National Bank of Kazakhstan, Central Bank of Uzbekistan, Bank of Mongolia, National Bank of Tajikistan, 2022.

During the first quarter of the year, as Central Asian economies were experiencing large exchange rate fluctuations, some central banks intervened to stabilise their currencies. For instance, the National Bank of Kazakhstan sold close to USD 1bn in March, while the National Bank of Kyrgyzstan imposed a temporary ban on financial enterprises to transfer cash US dollars outside of the country (Reuters, 2022[104]). By contrast, the National Bank of Tajikistan did not intervene to counteract the strong depreciation of the somoni in March, and the Central Bank of Turkmenistan kept the fixed exchange rate unchanged.

Windfall revenues have provided support to individuals and businesses

Higher than expected remittances, as well as relocation of Russian migrants with relatively high purchasing power, have sustained consumption across the region, especially in the services sector. The increase in the salaries of civil servants throughout 2022 decided by the Kyrgyz government also helped to support consumption in the country (Mir 24, 2022[105]). In addition, higher than expected revenues from energy and mineral commodity exports, have given governments some margins to support businesses in sectors affected by supply disruptions and rising costs, as well as to shield households from rising food and energy prices. However, constrained fiscal space might remain a lingering issue, as suggested by the Spring announcements of a halt in non-priority public spending for infrastructure and equipment made by the Tajik and Uzbek governments (Asia Plus, 2022[106]; Lex-UZ, 2022[107]).

Across the region, governments predominantly implemented measures in the agricultural sector to secure food and energy supplies, ensure price stability and increase agricultural output. The Kazakh government, for instance, enacted a new food security plan that aims to increase and diversify agricultural production, imposed temporary grain and flour export restrictions to its Central Asian neighbours, and introduced sales requirements on the domestic market (Kazinform, 2022[108]). The Kyrgyz government allocated an additional USD 85m to the Ministry for Emergency Situations to procure essential foodstuffs and energy commodities (24 KG, 2022[109]). In addition, the Uzbek, Kyrgyz and Tajik authorities introduced or extended several temporary exemptions to fiscal rules such as VAT waivers, transport tariff reductions, and customs, tax and excise breaks, to the benefit of food importers. They warned sellers of legal liability for unjustified price increases. The Turkmen authorities instructed farmers to increase planting and production of some foodstuffs to boost agricultural exports to Russia (Ozodi, 2022[110]). Governments in the region also announced measures to provide additional financial support to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and reduce administrative burdens. Announcements were made in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan to extend additional funding in the form of subsidies or loan guarantees to SMEs, and Tajikistan has enacted a moratorium on business inspections until 2023 and declared its intent to review more than 420 regulatory acts (Asia Plus, 2022[111]).

Central Asian countries have sought to diversify trade routes

Central Asian governments have been exploring new trade route options to offset the de facto closure of the “Northern Route” via Russia. As a result of sanctions against Russia, Central Asia has faced significant supply chain disruptions: forthcoming OECD surveys assessing the business climate in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan found that an overwhelming 97% and 85% of respondents respectively have faced logistical challenges due to the disruption of supply chains.

The Trans-Caspian International Transport Route – often called the “Middle Corridor” – could provide an alternative, but its capacity is at present only a fraction of that of the northern route via Russia. The Middle Corridor has considerable – as yet unrealised – potential, but it will still involve both longer shipment times and higher costs than the northern route (Eurasianet, 2022[112]) (ADB, 2021[113]). Changing that will require substantial investment to address infrastructure bottlenecks not only in Central Asia and the South Caucasus but also in Türkiye and the Balkans. Even then, this route is longer and it will involve more modal switches, which implies more loading and unloading, as well as more international frontiers, which means more border formalities, documents and tariffs.

Attention has also focused on developing southward routes to India, Pakistan or even – as and when sanctions are relaxed – Iran and Afghanistan, and eastward links to China. Following two decades of discussions, the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project was signed during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit on 14 September, and will be used as an alternative to the Russian route for transit to Europe: once completed, the new line could become part of a shorter route from China to Europe through Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran and Turkey. In the same vein, the region has been developing trade links with Pakistan: Uzbekistan entered into a preferential trade agreement with its southern neighbour, which Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan intend to replicate (The News, 2022[114]). Despite the sanctions imposed on its southern neighbour, Uzbekistan is also looking to develop the Trans-Afghan railway, which would link Tashkent to Pakistani ports of Karachi, Gwadar and Qasim through Mazar-e-Sharif and Kabul in Afghanistan (The Diplomat, 2022[115]).

This makes it imperative that participating countries move rapidly and effectively to streamline customs and other border formalities and to reduce to a minimum the costs associated with crossing frontiers along the Corridor. Developing such routes, wherever they run, will require more attention to the “soft infrastructure” of trade. Improvements to customs and border management, unification of documents and the harmonisation of regulations will matter as much as developing and debottlenecking the physical infrastructures along the new routes. Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Georgia have this spring taken some important steps to make the Middle Corridor easier but much more must be done. A co-ordinated, region-wide approach to trade facilitation reforms could do much to stimulate trade both within and across Central Asia. Indeed, governments could move beyond trade facilitation and liberalise trade within the region and across the corridor. A regional trade zone with co-ordinated trade policy, practices, and standards, technical and legal developments would open up new opportunities for Central Asia and would also strengthen its position vis-à-vis Europe and China. Progress down this path would require both stronger intergovernmental dialogue mechanisms and deeper, more meaningful public-private dialogue within and across countries.

Table 5. Overview of the main announced measures in Central Asia as of October 2022

|

|

Monetary policy |

Support to firms |

Support to households |

Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

KAZAKHSTAN |

Policy rate increase from 11.25% to 13.5% in February, to 14% in April, and 14.5% in July 600 M USD interventions of National Bank to stabilise the tenge |

Reduction of administrative checks and procedures, expansion of preferential leasing programme for agricultural equipment, subsidies for fertiliser, pesticides and insurance premia in the agricultural sector |

Temporary export restrictions on food products Deposit insurance guarantee on 10% of savings held on bank accounts as of February 23 Introduced price caps for basic food and energy products |

Discussions with third countries (e.g. Azerbaijan)on alternatives to Russian ports for oil delivery |

|

KYRGYZSTAN |

Policy rate increase from 8.5% to 10% in February, to 14% in March, and to 16% in August |

Tax breaks and reductions for food-importing companies, increase of concessional lending to firms in agricultural and energy sectors Launched a digital nomad program, allowing foreign citizens to enter and stay in the country without residence registration, and delivering them work permits |

Temporary export restrictions on food products Increased wages for government officials Additional budget allocated to Ministry of Emergency Situations to increase food stock purchases Flour handouts and 50% capped discount on electricity bills to low-income households |

Ban on USD transfers in cash outside of the country to prevent USD outflow China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway project for 2023 |

|

MONGOLIA |

Policy rate increase from 6.5% to 9% in March, 10% in June, and 12% in September |

Expenditure cuts of about of about 100 million USD in Spring amendment to the government budget Subsidized loans provided by the government to the agricultural sector 80% discount for vegetable and greenhouse seeds, which were purchased by the government |

Austerity Law was implemented for improving food security and coping with inflation Taxes were cut on selected food items (e.g. sugar and vegetable oil) 50% discount on social insurance payment for low-income employees until the end of 2022 |

Resumed trade cooperation with China (re-opening of border-crossing points, launch of new customs clearance systems, strengthened border cooperation) |

|

TAJIKISTAN |

Policy rate kept unchanged |

Moratorium on business inspections till January 2023 |

Increase social spending with assistance of development partners |

Halt in non-priority public spending for infrastructure and equipment purchases |

|

TURKMENISTAN |

No change |

No information available |

No information available |

Farmers have been instructed to increase agricultural output to boost exports to Russia |

|

UZBEKISTAN |

Policy rate increase from 14% to 17% in March, decrease to 16% in June, and to 15% in July |

Additional concessional financing to SMEs Work and visa programmes to attract foreign IT specialists Support to the agricultural sector (public purchase to supply seeds and seedlings to farmers; allocation of additional land for agriculture, fiscal exemptions for food imports) IT Visa for investors and IT professionals |

Expansion of support programmes to labour migrants and their families |

Halt in non-priority public spending for infrastructure and equipment purchases Hire of international consultants to review course of action for transactions with sanctioned Russian banks China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway project for 2023 |

Source: OECD (2022).