This chapter analyses current school, teacher and school leadership practices and provides recommendations focused on school improvement. With the proposal from the Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs for schools to have more pedagogical autonomy, a strong policy focus on school improvement will be needed to ensure that schools are able to benefit from new opportunities. It will be important to rethink the professional competencies school principals and teachers will need and to invest in building their capacity as they take on new responsibilities and new ways of working. Effective school improvement will also require regular evaluation of school performance. The Ministry’s plans to require school self-evaluation and principal appraisal are a first step to effective monitoring of school performance. A long-term plan to create an overall evaluation and assessment framework will ensure that decision makers at policy level and in schools have the information they need to ensure high performance.

Education for a Bright Future in Greece

Chapter 4. School improvement: Teacher professionalism and evaluation and assessment frameworks

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

In the Greek education system, schools have traditionally had little autonomy. As described in 0, “school units” are at the bottom of the Greek administrative pyramid; their main role is to deliver education and implement national education policies. Research points to the benefits of school autonomy in selected areas, including improved student learning outcomes. Autonomy in and of itself, however, does not guarantee high outcomes, as it depends on the capacity of schools to deliver. A strong focus on school improvement is needed. It will be important to rethink the professional competencies of school principals and teachers will need and to invest in building capacity as they take on new responsibilities and new ways of working.

The Greek Ministry of Education, Research and Religious Affairs (MofERRA) has made a number of proposals which aim to increase schools’ pedagogical autonomy, including the introduction of school self-evaluation (SSE) and school principal appraisal. To ensure the long-term success of these proposals, a clear strategy will be needed. Within this context, this chapter addresses the following two broad areas:

Teacher professionalism:

teachers’ material working conditions

effective management of the teacher workforce

the definition of professional competencies for school principals and teachers

support for teacher collaboration: schools as learning organisations, teacher networks

opportunities for teacher career growth and leadership.

Evaluation and assessment frameworks to support improvement:

school principal appraisal

school self-evaluation

a long-term strategy to introduce an overall framework balancing internal and external evaluation and assessment.

This chapter first summarises recent international data on school autonomy, policies impacting teachers’ working conditions, and policies shaping the overall efficiency and effectiveness of the workforce. Teachers’ initial training and opportunities for ongoing professional development are also discussed. Current approaches to evaluation and assessment are then presented (Section 4.1). Section 4.2 of the chapter reports on policy issues related to school improvement, based on the OECD review team’s visits and interviews, and evidence from the research literature. This includes a focus on school principals’ roles as pedagogical leaders, and on teacher professional development and schools as learning organisations. The final section presents policy options to support long-term, sustainable reforms, drawn from the analysis of the challenges and from the practices of other OECD countries (Section 4.3).

4.1. Greek schools, teachers and principals

4.1.1. School autonomy is lower than in other OECD countries

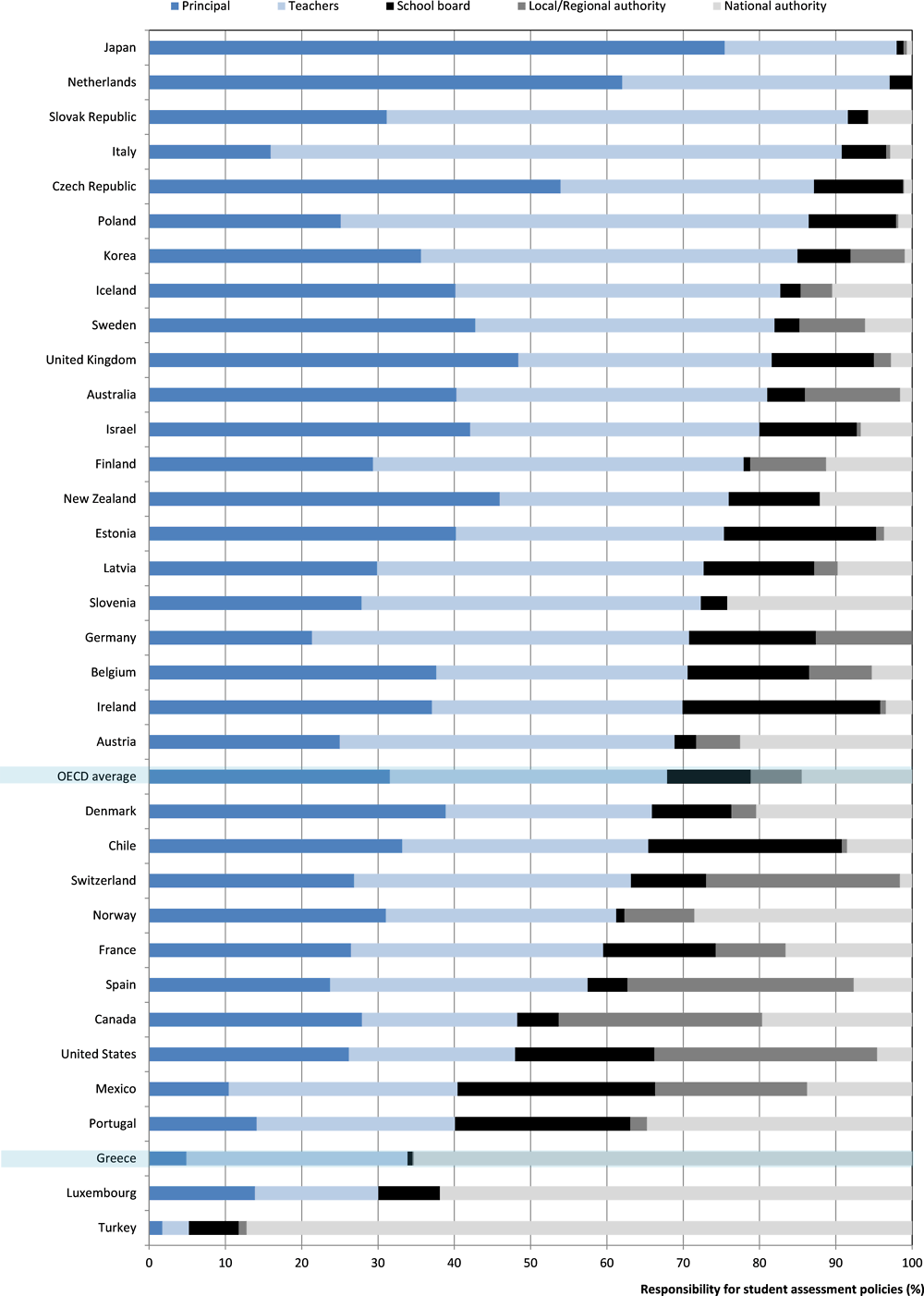

International data show that Greek schools have limited autonomy in relation to other OECD countries and economies. Indeed, of countries participating in the 2015 OECD PISA survey, Greece was ranked 69th out of 69 countries in school level responsibility for the curriculum (based on school principal survey responses). Teachers also have limited responsibility for establishing student assessment policies as compared to other countries and economies, with Greece ranked as number 60 of 69 countries included in the analysis (see Figure 4.1). These aspects are crucial to teachers’ ability to identify individual student needs and to adapt teaching and learning strategies appropriately.

Figure 4.1. Responsibility for establishing student assessment policies, 2015

Note: Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the responsibility held by school principals and teachers.

Source: OECD (2016[1]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

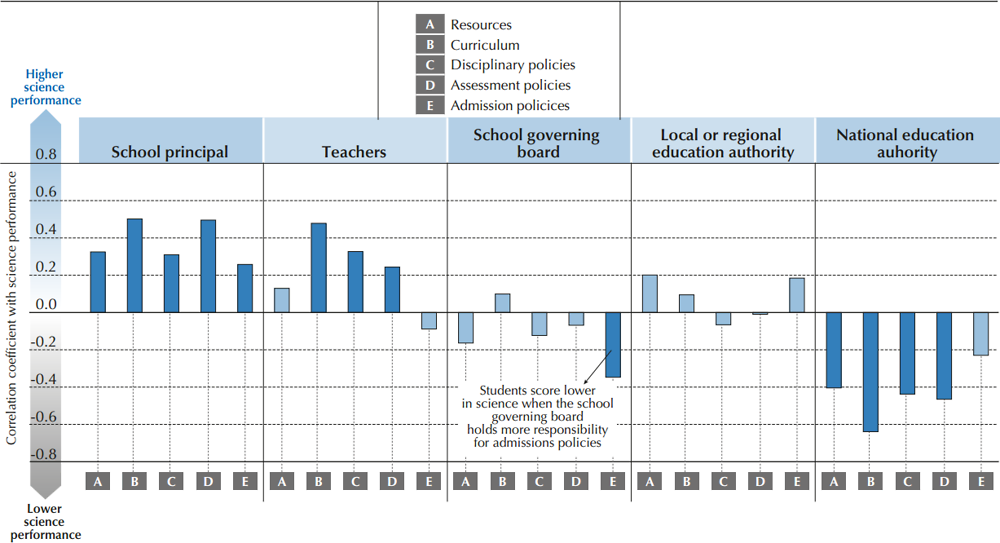

The OECD PISA 2015 results demonstrate a significant relationship between different aspects of school level responsibilities and science performance (Figure 4.2), in terms of school principal and teachers' responsibilities in resources, curriculum, establishing disciplinary policies, or establishing student assessment policies.

Figure 4.2. School governance responsibilities and science performance, 2015

Notes: The responsibilities for school governance are measured by the share of distribution of responsibilities for school governance. Results based on 70 education systems. Statistically significant correlation coefficients are shown in a darker tone.

Source: OECD (2016[1]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

These data demonstrate that student performance is strongly correlated with school autonomy, including strong roles for school principals and teachers, and for school governing boards and local or regional authorities. At the same time while research evidence shows that autonomy can contribute to make a difference in student learning, it depends greatly on the capacity of the staff working in schools to be able to use such autonomy, on the responsibilities assigned and also on school accountability for students’ results (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2014[2]; Hanushek, Link and Woessmann, 2013[3]; OECD, 2016[1])

4.1.2. Teachers work in difficult conditions

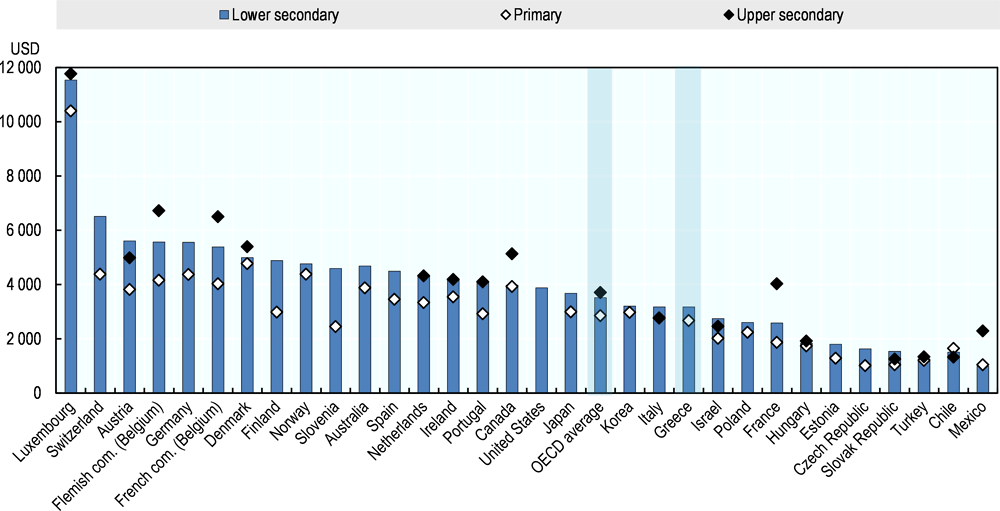

As teachers are asked to take on responsibilities associated with greater pedagogical autonomy and for school self-evaluation, it is important to take into account the impact the economic crisis has had on their material working conditions, job stability and morale. Teacher salaries have been reduced since the crisis, and seasonal bonuses eliminated. In 2012, teacher salaries were approximately 70% of the 2009 salary levels, with a slight increase to 75% of the 2009 level by 2016 (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2016[4]). The crisis has also led to a freeze in the hiring of teachers with civil servant status. As detailed in Chapter 2, all teachers hired since 2009 are working as “substitute” teachers, with annual contracts and frequent relocation to new schools. This lack of stability undermines opportunities for teachers to participate in school self-evaluation or school-level learning, to develop professional relationships (including relationships with mentors and peers) or strong teacher-student relationships. Figure 4.3 shows salary costs of teachers per student across a range of countries, estimated in relation to actual teachers’ salaries, instruction time of students, teaching time of teachers and estimated class size1. Greece’s salary costs of teacher per student in 2015 are slightly lower than the OECD average.

Figure 4.3. Annual salary cost of teachers per student in public institutions, 2015

Note: Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the salary cost of teachers per student in lower secondary education.

Source: OECD (2017[5]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

Although teacher morale is low, teachers remain motivated to support students

Challenging working conditions have an impact on teacher morale. A European study on the attractiveness of the teaching profession showed low teacher morale of the teacher workforce in Greece. The 2013 study, found that there had been a negative picture of teachers in the media, and that more than 60% of teachers who were asked if they might envisage looking for another job answered affirmatively (European Commission, 2013[6]). Officials from the Ministry who were interviewed by the OECD review team recognised the importance of teacher morale and the need to rebuild trust if they are to promote teacher professionalism and to build evaluation and assessment frameworks.

It is also important to note that during the OECD visits to Greece, the OECD review team met many committed and creative teachers in primary schools, lower and upper secondary schools. Teachers interviewed by the OECD review team were clearly dedicated to their students and enjoyed working with their peers. While several noted the stress of being asked to do more even though salaries had been cut, these teachers support students to the best of their ability. This dedication and willingness was also apparent in the OECD review team’s interviews with teachers working with refugee learners during the height of the refugee crisis. These teachers described how they had found ways to work with young learners who may have had limited or no schooling and with whom they did not share a common language. They brought games from home, found online language learning programmes, and other ways to overcome barriers. They thus accomplished their work within limited resources (see also Chapters 1 and 2).

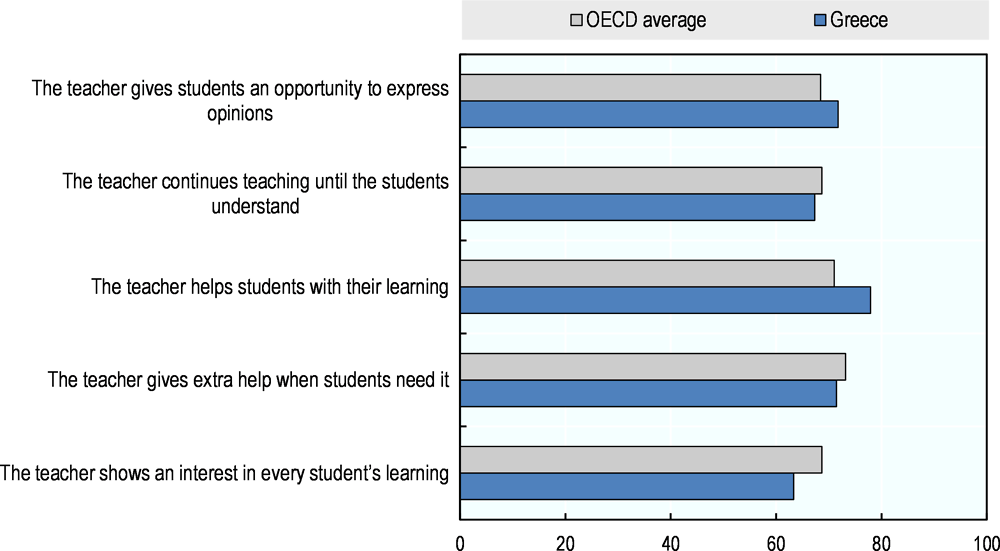

Greek students give generally positive feedback on their teachers, which is another indicator of teacher motivation to help students learn. According to the 2015 PISA survey, students in Greece report at a higher than OECD average level that they feel teachers support their learning (see Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4. Students’ views of teachers, 2015

Source: Adapted from OECD (2016[1]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en, Table II.3.22.

4.1.3. Challenges in the management of the teacher workforce

Decisions related to the teaching profession, in terms of the system of allocating teachers to schools (including teacher specialists), teachers’ working hours and the balance of teaching and administrative tasks, and teacher-student ratios appear to be less efficient than in other OECD countries. Inefficiencies in use of human and financial resources may also have a negative impact on teacher effectiveness.

However, it is important to note that school management decisions are not based on efficiency alone, as there are other contextual factors at play. For example, the decision to maintain small schools in remote areas reflects a desire to ensure that these communities will continue to thrive in spite of extra costs and staffing difficulties such a decision will bring. Nevertheless, the major educational and social advantages of maintaining small schools in isolated villages needs to be carefully weighed against the educational and economic advantages of concentrating schools in the towns and bigger villages.

Teacher allocation

The current system for allocating the teacher workforce presents challenges to both efficiency and effectiveness. As described in Chapter 2, recruitment, which is competitive, is centrally administered. This approach is considered as fair and objective: appointments are based on the number of points earned and therefore are not subject to favouritism. This approach is also considered necessary given the difficulty of attracting teachers to remote schools. Nevertheless, concerns regarding the impact of this system on teachers’ relationships with their students and with their peers, and on teachers’ personal lives need to be addressed. In addition, this centralised allocation system means that the teacher’s fit to the school approach and philosophy, and the ability of schools to build a team with the array of competencies needed to support schools as learning organisations are not part of the placement decision. These aspects are likely to become more important as pedagogical autonomy and teacher collaboration in schools develops.

Teaching time

Working hours for teachers and principals are specified by law. Every primary and secondary teacher is obliged to stay in school for not more than six hours a day for a maximum of thirty hours a week. This is the case for teachers with administrative duties (e.g. heads and deputy heads, heads of sectors, etc.) and, until recently, for other teachers only if they have been requested to do so by a member of the administrative staff and if they have been given concrete tasks to do (according to Article 9 par. 3 of N. 2517/1997, and Article 13 par. 8 and Article 14 par. 20 of N. 1566/1985).

Table 4.1 shows the statutory teaching hours for Greek teachers in a comparative perspective. According to Ministry sources, the statutory teaching hours per week for primary school teachers decrease as the size of the school increases. Teachers with more years of service in larger schools teach fewer hours as their length of service increases. While this is intended to prevent teacher “burn-out” (Roussakis, 2017[7]), having less experienced teachers assume more of the teaching load also means that the value of more experienced teachers is lost.

Table 4.1. Organisation of teachers’ working time, 2015

|

Number of statutory teaching weeks, teaching days net teaching hours and teachers’ working time in public institutions over the school year |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of weeks of teaching |

Number of days of teaching |

Net teaching time, in hours |

Working time required at school, in hours |

Total statutory working time, in hours |

||||||||||||||||

|

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower sec. |

Upper sec. |

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower sec. |

Upper sec. |

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower sec. |

Upper sec. |

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower sec. |

Upper sec. |

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower sec. |

Upper sec. |

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

(12) |

(13) |

(14) |

(15) |

(16) |

(17) |

(18) |

(19) |

(20) |

|

|

Greece |

36 |

36 |

35 |

35 |

175 |

175 |

172 |

174 |

788 |

630 |

592 |

600 |

1 140 |

1 140 |

1 170 |

1 170 |

A |

A |

A |

A |

|

OECD average |

40 |

38 |

37 |

37 |

191 |

183 |

181 |

180 |

1 001 |

794 |

714 |

664 |

1 230 |

1 156 |

1 135 |

1 095 |

1 608 |

1 611 |

1 634 |

1 620 |

|

EU-22 average |

40 |

37 |

37 |

37 |

191 |

180 |

177 |

177 |

1 034 |

767 |

666 |

632 |

1 194 |

1 067 |

1 033 |

1 028 |

1 564 |

1 557 |

1 593 |

1 580 |

Source: OECD (2017[5]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

Class size

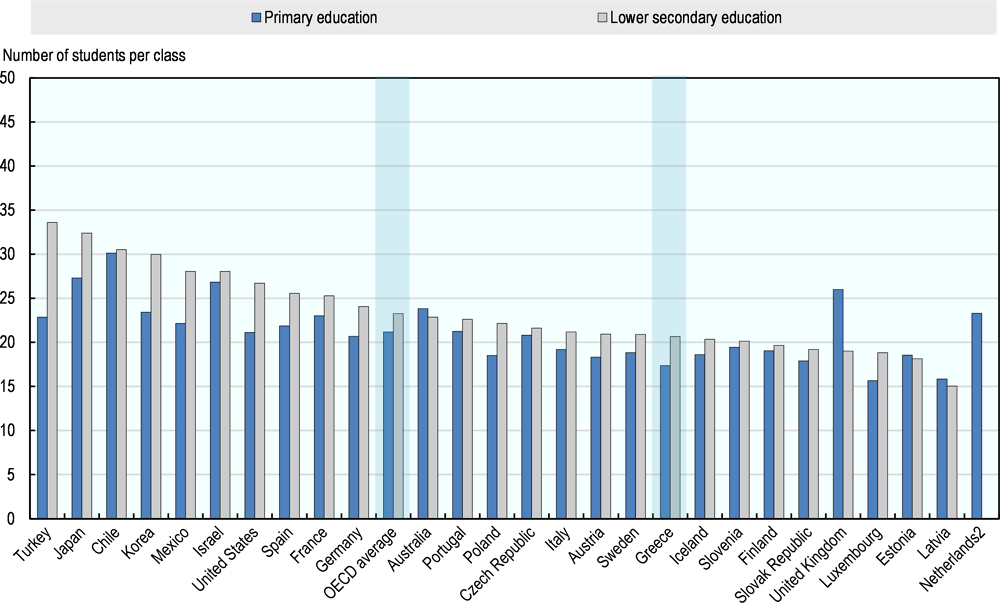

Class size is also considered as having an important impact on working conditions. The maximum class size is defined by law to be 25 students per class in primary schools and 30 students per class in secondary schools. In practice, average student-teacher ratios and class sizes in Greece are significantly lower than in most European countries (Figure 4.5 and Figure 4.6). To some extent, however, this average ratio is skewed by the number of small schools in isolated mountain communities and on small islands. More than half (54%) of Greek primary school students are in two regions: 34% in Attica, concentrated in the city of Athens, and 20% in Central Macedonia, concentrated in the city of Thessaloniki. The remainder of the primary school population is dispersed across thousands of communities (now organised into 325 prefectures).

Figure 4.5. Average class size in educational institutions, 2015

Notes:

1. Year of reference 2014.

2. Public institutions only.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the average class size in lower secondary education.

Source: OECD (2017[5]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

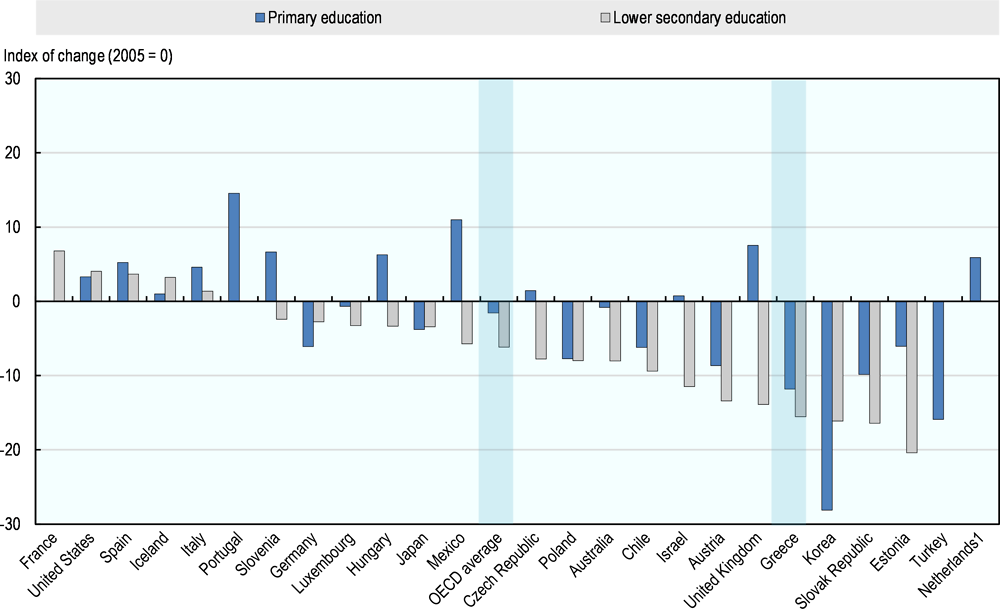

Figure 4.6. Change in average class size, 2005, 2015

Notes:

1. Public institutions only.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the index of change in average class size in lower secondary education between 2005 and 2015.

Source: OECD (2017[5]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

Other reasons for the low student to teacher ratio in Greece, as reported by the Ministry, include:

the small size of some classrooms

the obligation to create an additional class if the number of students exceeds 30

a maximum class size of 22 (3 fewer than regular maximum class size) if the group includes students with significant special needs.

Data on class sizes in remote areas, by level are summarised in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1. Average class size in Greece, by level, in remote areas

In remote areas, secondary schools include both the lower and upper secondary levels (respectively, gymnasiums (gymnasio) and lyceums (lykeio)).

For lower secondary schools in remote areas, the data are as follows:

number of students enrolled in 2016/17: 6 308

number of schools: 119

number of classes: 481

average students per class: 13.1.

For upper secondary schools in remote areas, the data are as follows:

students enrolled in 2016/17: 3 935

number of schools: 119

number of classes: 344

average students per class: 11.4.

Schools combining upper and lower secondary levels have fewer teachers, and may be more flexible in finding ways to meet the needs of students in remote areas.

Professional schools (Vocial lykeio, - Epaggelmatiko Lykeiok or EPALs) are also found in isolated and underpopulated areas. For example, on the island of Symi, there is a professional school with 28 students, and another professional school on the island of Ios with 25 students. Students participating in general education may choose between two academic tracks, beginning in their second year. Students in their second year of professional education may choose one of 36 areas of specialisation in nine different sectors.

Source: MofERRA (2017[8]), Communication to the OECD review team (September 2017).

While the average class size is small in comparison with international standards, some teachers interviewed by the OECD review team noted that in each class a few students require additional attention. Rather than signalling a need to further decrease class size as a general policy, however, this may indicate a need to improve teacher training and professional development to support diverse student needs. In addition, collaboration with a range of professional service providers within the community may also support teachers’ work with diverse students.

Salary costs per student are also relevant to decisions on class size. In 2011, these costs were above the OECD average, but in 2015 they were below the average (USD 2 671 per student in Greece versus the OECD average of USD 2 848 per student) (Figure 4.3). The level of teachers’ salary costs per student depends on a country’s relative wealth; in Greece, due to budget cutbacks, salary costs per student in Greece are a higher percentage of country GDP than the OECD average (10.2% in primary and 12.1% in Greece in lower secondary versus an OECD average of 7% in primary and 8.6% in lower secondary education) (OECD, 2017[5]).

Optimisation of teaching time

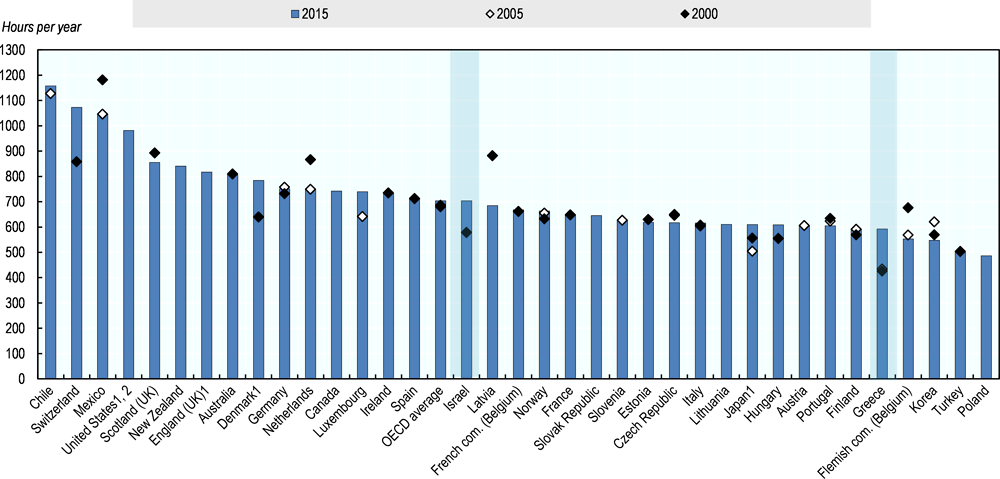

Teachers in Greece spend less time teaching than the OECD and EU-22 averages in general lower secondary education, but their overall working time at school (including for administrative work for some teachers), is near or above the OECD and EU-22 averages. This means that teachers spend less time with students as well as in collaborative work with peers than do teachers in other OECD and EU countries. The OECD review team was told that teachers in small remote schools take on a higher share of the administrative burden for their schools, including routine tasks. The introduction of school self-evaluation may increase some administrative tasks, but this in the interest of gathering data on school performance. Figure 4.7 shows how much time teachers spend teaching across a range of OECD countries.

Figure 4.7. Number of teaching hours per year in general lower secondary education, 2015

1. Actual teaching time.

2. Year of reference 2013 instead of 2015.

Notes: Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the number of teaching hours per year in general lower secondary.

Source: OECD (2017[5]), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en.

In Greece, more experienced teachers are rewarded with fewer teaching hours, representing a significant underuse of human resources.

4.1.4. Limited opportunities for teacher professional development and career growth

Teachers develop their professionalism throughout their careers. Beginning with initial teacher education and induction (pedagogical training and/or subject matter expertise), and continuing with participation in ongoing professional development, and collaboration with peers within schools and in teacher networks. Teacher professionalism also includes opportunities for career growth, including roles for more experienced teachers as mentors or researchers.

Initial teacher education and induction

In Greece, the teaching profession is a career-based public service with competitive entry and lifetime employment. The quality of the teaching profession is thus highly dependent on the quality of initial teacher education, induction and recruitment. Indeed, initial teacher education is the foundation for teachers’ lifelong learning – that is, their professional growth over the course of their careers.

Teacher education follows a sequential learning model in Greece, with teaching practice following tertiary study (studies in pedagogy for primary school teachers, and studies in different disciplines for secondary school teachers). New teachers must participate in an induction programme, which lasts less than a year. All prospective teachers in primary education and secondary education must complete a first cycle degree (UNESCO, 2015[9]). School teachers who study in teacher faculties are expected to follow a pre-service teacher training programme of four years, being trained and qualified in the undergraduate programmes of study offered by the relevant university departments and have a mandatory teaching practicum (OECD, 2016[10]). Prospective teachers can also follow more general tertiary courses and add a Certificate of Educational Attainment in order to qualify as a teacher. (The OECD review team was told that many teachers have higher than the required levels of education – master and doctoral level – although there are no available data on this).

Teacher certification

As noted above, all teacher candidates for permanent or substitute positions must have taken the Supreme Council for Civil Personnel Selection (ASEP) examination. It has been observed that this examination this state-administered examination assesses the acquisition of subject content and prospective teacher performance (as measured, for example, through preparation of a lesson plan). This includes general knowledge of pedagogy, psychology and sociology of education (Liakopoulou, 2011[11]). However, these examinations do not measure teachers’ pedagogical competencies – that is, their ability to use that knowledge in practice. Nor do the examinations include questions on contemporary concerns, such as intercultural or special needs education, or how they might adapt curriculum or textbooks to respond to students’ learning needs (Liakopoulou, 2011[11]). A lack of alignment between the ASEP examination and classroom practice represents a missed opportunity to identify candidates who are unable to translate theory into their classroom practices.

Teachers have few opportunities for long-term career growth

Currently, teachers’ career trajectories in Greece are relatively flat (European Commission/EACEA/EurydiceEurydice, 2018[12]). As noted above, more experienced teachers are rewarded with fewer teaching hours, rather than opportunities for career growth. In the context of content-intensive central curriculum and textbooks, and at the upper secondary level, a strong focus on helping learners to pass the Panhellenic university admissions examinations, teachers in Greek schools also have limited autonomy as compared to other OECD countries. The OECD review team was told that parents of upper secondary school students also exert pressure on teachers to adhere strictly to the curriculum and official textbooks, which are seen as being aligned with the Panhellenic. However, teachers interviewed by the OECD review team noted that more experienced and confident teachers do find ways to adapt lessons to meet individual student needs. In schools with strong principals, support from the regional school advisor, and stable staff, these opportunities are more likely to occur.

During the OECD review team visits, teachers interviewed expressed their desire for more professional development opportunities, which they see as an important incentive (particularly as monetary incentives are currently restricted). Professional development was also seen as necessary to support the implementation of special initiatives at the school level. For example, some teachers interviewed commented that they would have liked to have more training and support to implement the thematic week piloted in early 2017 (an initiative to allow teachers to depart from the curriculum to teach life skills, such as health). Teachers also stated that any curricular reforms would require greater investments in teacher professional development.

4.1.5. School principals are administrative managers rather than pedagogical leaders

School principals have an important role to play in guiding school improvement and supporting teacher professionalism. Yet, as described in Chapter 2, school principals in Greece are primarily administrative managers. Greek legislation prevents school principals from entering teacher classrooms, so there are few if any opportunities for professional interaction centred on teaching quality. As schools are granted greater pedagogical autonomy, school principals will need to take on more responsibility for leading their schools as learning organisations.

Recent legislation has aimed to address this concern, in part, by inviting each school’s board of teachers to provide input on potential candidates for the position of school principal. The intention is to ensure a good fit between the school staff and its principal. As required in previous legislation, candidates must also fulfil basic criteria: a minimum of eight years teaching experience; an advanced degree (doctoral or master level) or additional studies at the bachelor level; and administrative experience.

In addition, in 2012, the Ministry introduced a number of new training opportunities and seminars for school principals. In 2016, the National Centre for Public Administration and Local Government (EKDDA)/ Institute of Training (INEP)-Greece introduced additional training to support school principals’ organisational skills, crisis management, working in a multicultural environment, and other areas.

4.1.6. Weak evaluation and assessment

Greece’s approach to education accountability has been designed to prevent abuses of the system. There is a deep-rooted suspicion that evaluation (of schools and of individual school principals and teachers) may be used as a political tool, as was the case during the 1967–74 military dictatorship (see also Chapter 1). The OECD review team was repeatedly informed of the lingering impact of this period on the profession and society throughout the fact-finding mission – even from those too young to have experienced it directly (Kribas, 1999[13]) There are also concerns that evaluation and assessment may be vulnerable to “rent-seeking behaviour” (i.e. the exchange of goods or services for favourable evaluations). More recently, teachers have expressed concerns that in conditions of austerity, school and teacher evaluations may be used to justify workforce reductions.

Teacher and school principal appraisal

Teacher mistrust of evaluation was highly apparent with the introduction of a teacher appraisal system in 2013 which stipulated that school advisors should find at least 15% of the teacher workforce inadequate – which created risks for their employment prospects. The majority of schools refused to take part in the appraisal system, so it was quickly abandoned (OECD, 2017a[14]). Teachers and their representatives have subsequently refused to accept any kind of performance appraisal. They also argue that they are in any case held accountable for covering curricular content, and they are monitored through daily logs they must complete. However, it is also the case that they have few opportunities for feedback on their teaching practice. As described in Chapter 2, school principals do not have the right to enter teachers’ classrooms to observe lessons, and regional school advisors, who provide pedagogical support to teachers, can only enter classrooms if invited, which makes it challenging to provide feedback based on observation.

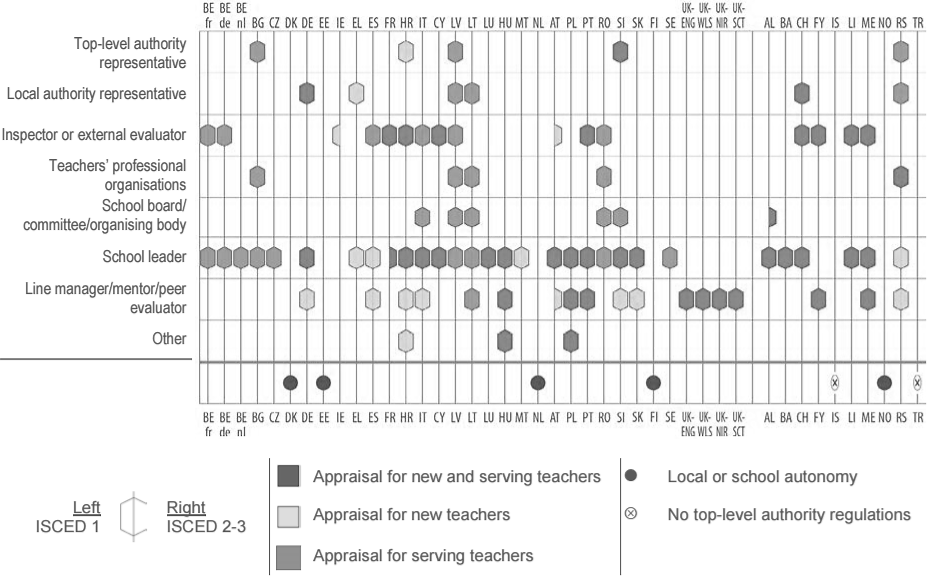

Figure 4.8 shows that in most European countries, school principals have a role in teacher appraisal, which is an essential aspect in providing feedback on teaching practice (European Commission/EACEA/EurydiceEurydice, 2018[12]).

Figure 4.8. Responsibilities for teacher appraisal, 2016/2017

Source: European Commission/EACEA/EurydiceEurydice (2018[12]), Teaching Careers in Europe: Access, Progression and Support. Eurydice Report, Publications Office of the European Union.

While the Ministry has made the choice not to introduce teacher appraisal, it has recently introduced a new system for appraisal of school principals (described further in this Chapter). Greece reports that from 2018, there will be yearly appraisal for 20 000 education executives in primary and secondary schools (MofERRA, 2018[15]). However, so long as school principals have limited roles in pedagogical leadership, the focus of the appraisals will be more on school management (see Chapter 2). The Ministry has also informed the OECD review team that under the new reform to introduce school self-evaluation, every school’s teacher board will be required to evaluate its planning, scheduling, and implementation of education programmes. These school self-evaluations are both formative (focused on improvement) and summative (focused on school performance).

Student assessment

The reliance on the Panhellenic university entrance examination as the “gold standard” for student assessment is another example of how the system has been designed to prevent corruption. As discussed in Chapters 2 and 3, the Panhellenic, which is centrally developed and administered, is currently the only measure used for university admissions decisions. A consequence of this is that the stakes of the Panhellenic for students’ chances to enter a good university are extremely high. Moreover, this focus on a single examination has meant that university admissions are based on a very narrow view of what students know and are able to do. Teaching is significantly narrowed and teachers’ limited role in assessing the students they teach and can undermine their sense of professionalism. (See Chapters 2 and 3 for additional discussion on the student assessment approaches.)

School evaluation

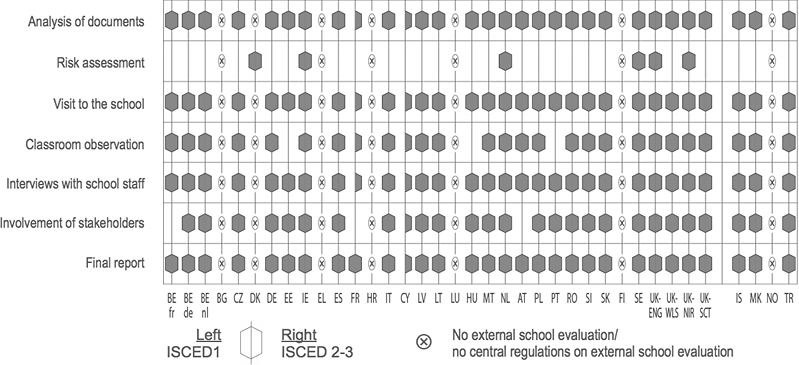

Until very recently, Greece was the only EU country that did not require either external or internal school evaluation (the new system of school self-evaluation is discussed further), although there are reports that from 2018, there will be yearly evaluation for 20 000 education executives in primary and secondary (MofERRA, 2018[15]). The absence of external and internal school evaluation has meant that schools do not have the data they need to identify strengths and opportunities for improvement. This lack of transparency of school and student performance has also likely contributed to low levels of public satisfaction with and trust in the system (see Chapter 2). Figure 4.9 shows countries that currently have external school evaluation systems in place.

Figure 4.9. External evaluation of schools, 2013/14

Source: Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015[16]), Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe.

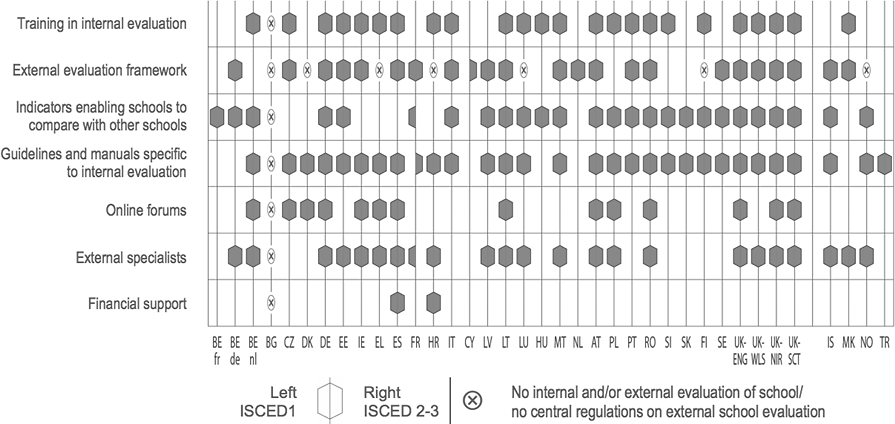

European Commission sources report that most EU countries have external school evaluation. Schools in the majority of EU countries conduct internal evaluation (SSE) based on different measures that support school self-evaluation. Figure 4.10 highlights a number of supports that are made available for school’s internal evaluation. In Greece in 2016-17, a new system of SSE was successfully piloted. Based on this pilot, compulsory SSE is being introduced across the school system.

Figure 4.10. Supporting measures available to internal evaluators of schools

Source: Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2015[16]), Assuring Quality in Education: Policies and Approaches to School Evaluation in Europe.

4.2. Policy issues

As has been noted in the previous sections, the Ministry has developed a range of proposals and strategies to address some of the challenges outlined above. In this section, evidence underpinning the importance of teacher professionalism, school leadership and autonomy for school improvement is presented, and challenges in long-term policy development are identified.

4.2.1. A need to extend and support school and teacher autonomy

The Ministry and its advisory agencies have proposed to extend greater pedagogical autonomy for schools. These plans include:

continuing with thematic weeks in schools

more options for students to study a range of subjects

strengthening of classroom-based formative assessment

a stronger role for teachers in summative assessment, as part of the university admissions score

school principal appraisal

school self-evaluation (which is also intended to improve opportunities for teacher collaboration).

These actions and proposals represent important steps toward greater school and teacher autonomy. Teachers will potentially have more control over content and teaching methods during the newly introduced thematic weeks, and there are to be new subject offerings in upper secondary schools in areas that are not featured in the Panhellenic. A greater focus on classroom-based formative assessment of student learning highlights the importance of timely, targeted assessment to identify and respond to diverse student needs. The inclusion of teachers’ summative assessments in university admissions, decisions would recognise the value of teacher professional judgement, and relieve, to some degree, the stakes of the Panhellenic (current plans are that university admissions decisions be based on the student’s results on the Panhellenic examination, as well as assessments of their teachers, respectively counting for 80% and 20% of the student’s overall score).

Further steps to strengthen teacher professionalism need also to be considered. The OECD conceptualises teacher professionalism as a composite of teachers’ knowledge (pedagogical and content knowledge); the degree of autonomy they have to make decisions over aspects related to their work; and, their participation in peer networks, which provide opportunities for knowledge sharing and support needed to maintain high standards of learning (OECD, 2016c[17]). These aspects also support “solidary incentives” – that is, teachers’ status as part of a professional community (Finnigan and Gross, 2007[18]).

Newly introduced requirements for school principal appraisals and school self-evaluation are important first steps in developing an overall evaluation and assessment framework. These evaluations need to be tied to the overall aims for education and student learning. It will also be important over the long term to extend evaluation and assessment to ensure that data reflect a well-rounded picture of school performance. Directions for further development are explored in more detail below.

4.2.2. Reviewing the efficiency of teacher workforce management

A need to improve teachers’ material working conditions

Discussions of teacher professionalism touch on issues related to teachers’ working conditions (teaching time, deployment, stability of employment, opportunities for career growth). These incentives may have an important impact on teachers’ decisions to stay in the profession (Münich and Rivkin, 2015[19]). In the context of austerity, however, there has been little attention to salary-related issues. Indeed, the introduction of substitute teachers to the workforce, discussed in Chapter 2, has created new challenges. Recent graduates of initial teacher education interviewed by the OECD review team recognised that they may need to wait years before they are able to obtain a permanent placement.

Researchers note the importance of finding an appropriate balance between monetary and non-monetary incentives for teachers. Some researchers argue that salary levels need to be competitive with those offered in other professions that require tertiary education. But they also recognise that other non-monetary incentives are important – including teachers’ intrinsic incentives related to the satisfaction of helping students to learn, working conditions within schools, including the school ethos and management, or opportunities to be part of a professional community (Münich and Rivkin, 2015[19]). As discussed in Chapter 2, in other countries where austerity measures have had an important impact on public sector employees’ working conditions, opportunities to participate in social dialogue or surveys inviting input in making difficult decisions have been important for supporting morale (see Chapter 2).

Teachers interviewed by the OECD review team suggested other measures that would go some way to improving their working conditions. These include greater stability in job placements. Teachers noted that, particularly for those just beginning their careers, annual relocation is particularly challenging. It is difficult to develop relationships with their colleagues and students. In some areas, the cost of living is higher, so appropriate salary adjustments are needed (see also Chapter 2).

These teachers also recognised the challenge of staffing remote schools. Some suggested that placement criteria might also take into account proximity to the teachers’ home town, avoiding a situation where teachers who are already from a remote area (and therefore more familiar with the living and working conditions) are placed in a remote location that is far from their family.

Hanushek, Kain and Rivkin propose that improvements in working conditions for teachers in remote schools are important to ensuring stability, including the quality of school leadership, as well as support teachers receive to address challenges (Hanushek, Kain and Rivkin, 2002[20]). Broader reforms to improve these aspects may thus contribute to improving the challenge of staffing remote schools.

The OECD review team also asked teachers for their views on the introduction of opportunities for career growth, with options for more experienced teachers to deepen and fully utilise their professional skills (e.g. options in Estonia and Singapore). For example, teachers who opt to become mentors may support new teachers in developing their skills. Teachers who opt to develop skills as research-practitioners may take a leading role in collaborative action research. The teachers interviewed by the OECD review team had positive reactions to the idea of new opportunities for long-term career growth.

Some teachers interviewed during the OECD review team visits noted that sabbaticals to enable them to further their professional education would not only enhance their competencies, but would also contribute to job satisfaction (an important intrinsic incentive). Interestingly, teachers had different reactions to the introduction of the thematic week, which allows teachers some autonomy in deciding how they will use this time. In one school, teachers were quite enthusiastic about the thematic week. They enjoyed the opportunity to work collaboratively; they also highlighted that their school principal was particularly effective at identifying additional resources and working with community members to ensure the success of special initiatives, in general. In another school, teachers expressed some concern about finding ways to best use the time, and indicated that they felt the need for much more support and guidance.

A need to make better use of teacher time

A number of inefficiencies in the use of teacher time were noted above, including the number of hours dedicated to administrative duties versus teaching. The OECD review team was informed that schools often do not have administrative staff, and that many of these tasks have to be undertaken by teachers or principals. A thorough examination of administrative processes throughout the school system can help to identify how teachers are now spending their time, whether administrative tasks might be streamlined, whether better use might be made of ICT, and if non-teaching staff in schools or in authorities can take on some administrative tasks. In some schools or networks of schools, alternative models for staffing structures may be considered (Accounts Commission for Scotland, 1999[21]).

Perhaps the greatest inefficiency is that more experienced teachers are rewarded with fewer teaching hours, in lieu of other types of recognition. As suggested above, a better way to reward more experienced teachers would be to offer opportunities for career growth. While, for example, experienced teachers who work as mentors may have less direct teaching time, they may spend more time supporting new teachers.

A need to address inefficiencies in teacher allocation

Greece maintains a number of small schools in remote areas. This is a political choice to ensure that these small communities continue to thrive (see also Chapter 3). Greece’s geographical diversity and its small communities are important part of the country’s character. Data on Greece’s relatively low teacher-student ratio nevertheless indicate that there are still some opportunities to identify efficiencies in the system. These decisions need to also be balanced with appropriate support for teachers, including training for teachers to work with larger classes and diverse student needs, and availability of up-to-date ICT facilities to support teachers in tracking student learning or for independent student work. Opportunities for team teaching with combined classes may also be explored.

4.2.3. Supporting teacher effectiveness

A need to define professional competencies

Increasingly, OECD countries define teacher effectiveness through professional competency frameworks and/or standards that set out the knowledge, skills and attitudes teachers need to support student learning. Darling-Hammond and colleagues (2017[22]) observe that competency standards serve as the linchpin for teacher policy in high-performing education systems, supporting a shared understanding of teacher professionalism and providing a coherent approach to recruitment, training, and professional growth. Competency frameworks may also be useful for developing a more strategic approach to human resource management at the school level, allowing school principals to ensure they have a full complement of high-quality staff to meet needs. Hondeghem, Horton and Scheepers (2005[23]) emphasise that competency approaches may be used as a vehicle to bring about more change and flexibility within an organisation.

This development of professional competency frameworks is also in line with development of National Qualifications Frameworks (NQFs), which define competencies across sectors, including for education, and are typically based on analysis of specific job requirements and developed in consultation with stakeholders. The NQFs may set levels to reflect career progression (CEDEFOP, 2016[24]).

There are growing expectations that teachers can operate in new organisational structures, in collaboration with colleagues and through networks, and be able to support individual student learning and well-being. These call for demanding concepts of professionalism: the teacher as facilitator and knowledgeable expert, individual and networked team participant, oriented to individual needs and to the broader environment (OECD, 2001[25]). These concepts of professionalism imply that teachers not only transmit knowledge to students, but also support students’ ability to access and structure that knowledge as they develop their skills for critical thinking, creativity and problem solving (Collard and Looney, 2014[26]).

Teacher professional competency frameworks are aligned with broader aims of education, but also recognise that there is no “one best way” to teach. Rather, teaching is adapted according to the context of teaching and diverse student needs, and support equity of student outcomes. Professional competency frameworks are broad enough to accommodate these differences. Competency frameworks may also be adapted for teachers working in different schools, contexts and for different subject areas. For example, teachers working in remote regions with learners of different ages may need specific competencies that are not required in urban settings. Subject-specific competency frameworks may also be developed (e.g. related to digital competencies, arts education, mathematics education, and so on).

Teacher professional competency frameworks set out the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that are important for teachers to develop. Competency frameworks thus inform the design of teacher learning in universities, ongoing professional development seminars and courses, and in schools themselves. A few countries have introduced competencies to be developed at different stages in teachers’ careers – e.g. Estonia, Latvia or Scotland (United Kingdom) and Singapore (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017[27]) – beginning for example, with initial teacher education and induction and continuing with professional development as teachers deepen their experience. At advanced career stages, teachers may seek opportunities to take on roles as mentors or practitioner researchers (European Commission/EACEA/EurydiceEurydice, 2018[12]).

Initial teacher education

Initial teacher education is a key element of the continuum of teachers’ professional growth and development. It sets the conditions for high-quality teaching and learning. In Greece, with current plans for curricular reform, and the need to update teacher competencies, it is important to review the current provision of initial teacher education to understand whether it is effectively delivering for this new reality.

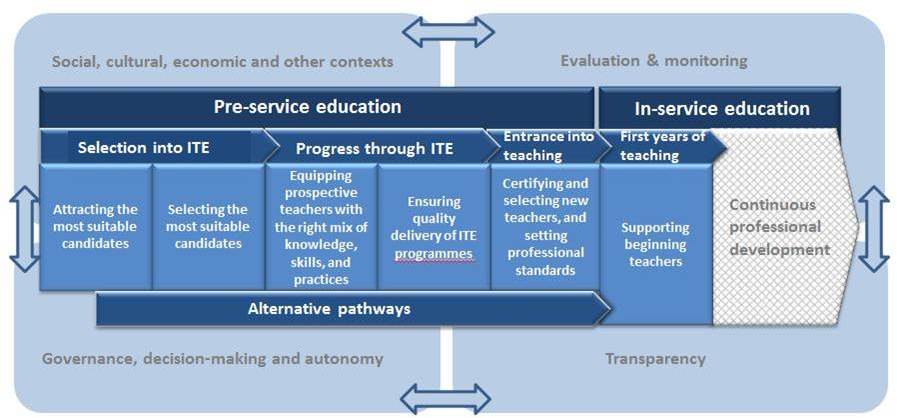

An ongoing OECD study on initial teacher preparation (ITP) analyses common challenges, strengths and innovations in initial teacher preparation systems in a range of education systems. It defines ITP as a composite of two components:

pre-service education: education and training provided to prospective teachers before they are qualified to teach

induction: activities designed to support new teachers.

A conceptual framework – known as the OECD Teacher Education Pathway Model (adapted from Roberts-Hull, Jensen and Cooper (2015[28])) – defines the scope of four consecutive pathways for teachers, including “alternative” routes into the profession – from the point at which candidates are selected into ITE programmes, complete the ITE programme, enter teaching and spend their first years in the profession – with six themes and contextual issues:

attracting candidates into ITE programmes

selecting the most suitable candidates into ITE programmes

equipping prospective teachers with the necessary knowledge, skills and practices

delivering ITE programmes effectively

certifying and selecting new teachers

supporting new teachers.

Figure 4.11. OECD Teacher Education Pathway model

Source: Adapted from Roberts-Hull, Jensen and Cooper (2015[28]), A New Approach: Reforming Teacher Education.

Schools’ and teachers’ ongoing development: A need to support schools as learning organisations and teacher networks

The large of majority teachers responding to the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) indicate that they want more opportunities for professional development. Many teachers have difficulty in finding the time to participate (47%), or are unable to find suitable courses or seminars (42%) (OECD, 2013[29]). In Greece, professional development opportunities have diminished as budget cutbacks have been made. The current supply of professional development appears to be limited and dispersed and the OECD review team was not made aware of the range of professional development opportunities available for teachers. It appears that many teachers attend public universities and take up master or doctoral level studies. Professional development options could be made clearer and more directly related to identified school needs.

The OECD review team was told that regional directorates and school advisors continue to work with schools to provide opportunities that support teacher development needs within their budgetary means, and that there will be a renewed effort as school advisors take up a new role as in-service trainers. Providing effective professional development opportunities for teachers that is aligned to the needs of the schools and to the local context can contribute to improve teacher performance. This can be fostered through teacher training, through engagement with teacher networks, or by providing support for schools to develop their own training. School advisors and networks may support school-based training opportunities. It will be important to ensure that their roles are appropriately aligned, and that they build their capacities to take on these tasks. These options, along with the concept of schools as learning organisations, are discussed further below.

The OECD review team was informed of the Ministry’s intention to provide further support for teacher collaboration in schools and in teacher networks. If these are effectively developed, they may potentially play an important role in supporting teacher professionalism. Indeed, a growing body of research supports teacher collaboration as an effective approach to professional development and school improvement (Louis et al., 2010[30]; O'Day, 2002[31]; Scheerens, 2010[32]).

Teacher collaboration within schools, however, depends on effective school-level leadership, including whether and how: school principals adopt a pedagogical leadership role, stimulate team work and collaboration, focus on the use of school evaluation to support improvement, develop the capacity to find resources. A cohesive staff, which includes individuals with complementary competencies, also supports effective team working within a school.

Teacher collaboration may involve peer observation, mentoring and coaching, lesson planning, action research, and visiting and observing teaching in other schools. It may also involve collaboration with other professionals (community representatives, artists, employers). Collaborative professional learning helps to build trust among peers, and trust supports effective organisational learning.

Box 4.2. International research on observed factors that support effective networks in education

In the United States, DuFour (2012[35]) found that the school districts were able to create effective professional learning communities (PLC) by building shared knowledge about the PLC process and its rationale; creating guiding coalitions and sharing leadership responsibility for implementation and; setting clear expectations for schools and their engagement.

Williams (2013[36]) found that effective networks of teachers in urban school districts involved within-school collaboration (comparing and contrasting teaching approaches), use of data to identify areas for improvement, for individual schools within the network, and effective face-to-face collaboration to augment work in the wider network

Holmes (2013[37]) noted that online interactions through social networks that are free of bureaucracy allow teachers to talk more freely. Over time, teachers may build communities of trust, shared values and reciprocity. When teachers combined online learning with application in their own classrooms, and were able to see benefits, they were more willing to invest additional time in the network.

Hopkins (2003[38]) found that networks for innovation in policy and practice are most effective when values and focus are consistent; the structure of the network is clear; the network supports knowledge creation, utilisation and transfer; the impact on learning is clear; leadership is clear, participants are empowered, and there are adequate resources. Involvement of a wide range of stakeholders is also important, including teachers, school principals, network initiators and managers, consultants, researchers and evaluators, and policy makers.

Harris (2008[39]) argues that the following principles should be at the core of an effective online development and research network: participation beyond the boundaries of a traditional local authority; a clear purpose, mission and community values; bringing in new members and changing external contributors and facilitators over time; a clear plan of action to catalyse change; infrastructure to enable individuals to assess their capacity to contribute; feedback; and, perceived return on investment.

Teachers interviewed by the OECD review team said that they currently have opportunities to collaborate with their peers. For example, primary school teachers interviewed noted that the curriculum allows two to three hours each week to develop project-oriented lessons (referring to this as the “flexible zone”) and that the school principal and teachers work together to decide on the themes and how they will be addressed. The introduction of school self-evaluation in Greece may potentially serve the dual purpose of supporting evaluation of school performance as well as helping to build schools as learning organisations. Effective school self-evaluation will ensure that schools have data to identify strengths and areas where improvement is needed. The process of gathering and analysing data also supports schools as learning organisations.

Potentially, teacher networks may also support teacher peer learning across schools,. School-school partnerships and clusters may be effective for schools in closer geographic proximity. Indeed, the idea of the school as a learning organisation (Kools and Stoll, 2016[33]) views individual schools as part of a larger network with other schools. Other network members may include higher education institutions, parents, and community members. Currently educational networks in Greece are not well-developed, and teacher collaboration appears to be ad hoc, rather than as a regular occurrence, (European Commission, 2013[34]). Researchers have identified a number of features of effective networks (Box 4.2) that could be relevant for Greece.

Few data on school and student performance, but an emerging focus on the quality of performance and outcomes

A well-designed framework for evaluation and assessment is key to school improvement, and to ensuring transparency of school performance. There is broad consensus among researchers and practitioners that an evaluation framework needs to be underpinned by a shared understanding of effectiveness – whether it is defined in frameworks or standards. Expectations for performance of students, schools, principals and teachers should be aligned (OECD, 2013[40]).

Several education systems have developed a common definition of a “good school” in order to provide a common basis for evaluation (linked with the national vision for education; see Chapter 2). A robust, research-based foundation can support the development of clear standards and criteria for school quality (OECD, 2013[40]). Given the prevalence of regional disparities in Greece and declining educational outcomes as measured by PISA, addressing this has to be a priority for the country.

Factors generally associated with the quality and standards of schools include: the quality of teaching and learning; the way teachers are developed and helped to become more effective throughout their careers; the quality of instructional leadership in schools (Louis et al., 2010[30]; Robinson, Rowe and Lloyd, 2009[41]). Factors concerning the curriculum, vision and expectations, assessment for learning, and the rate of progress of students, including learning and well-being are also important. Research suggests a broad range of indicators for student learning and well-being be included, such as student progress and outcomes, and the extent to which every student in a school: is making better than expected progress given their earlier attainment; is pleased with the education at the school; feels safe and happy at school; gains the knowledge, skills, understanding and attitudes necessary for lifelong fulfilment (MacBeath, 2004[42]).

Often criteria for school evaluation are presented in an analytical framework comprising: context; input; and process and outcomes (OECD, 2013[40]). The national framework may then establish clear standards, criteria and quality indicators for key school areas, such as teaching and learning, student well-being, school leadership, educational administration, school environment, and the management of human resources.

Transparency of information, high-quality data, and the accountability of school agents are essential for a well-functioning evaluation and assessment system. Transparency extends to processes (e.g. how school principals and teachers are appointed, implementation of reforms) as well as evaluation and assessment and report of outcomes (e.g. student achievement and well-being).

Transparency extends to every level, including the overall performance of the school system, the performance of individual schools, school principal appraisal, and the quality of teaching and learning. It is important to ensure that the existing data and information are relevant and usable, and that they are actually used for development and improvement. This requires reflection on designing mechanisms to ensure that the results of evaluation and assessment activities feed back into teaching and learning practices, school improvement, and education policy development (OECD, 2013[40]).

Greece has initiated some promising efforts to move toward a more holistic approach to quality assurance in Greek education. In 2016, the Ministry developed a three-year education plan, with its main axes focused on reforms to the upper secondary school, vocational education and training, and tertiary education. The three-year plan suggests, inter alia, introducing school evaluation and school leadership appraisal. These plans may be further strengthened through strong links to an overall vision for education focused on student learning and well-being. Initiatives included in the plans will also require benchmarks to be established and school-level capacity to be supported.

These next steps will be vital for setting a clear roadmap for implementation as well as a realistic set of measures by which to gauge progress toward goals (Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs, 2017[43]). It will also be important to address teacher concerns that results might be used punitively.

Following the Ministry’s three-year plan for education, two advisory institutions were invited to develop proposals for school self-evaluation. Subsequently, the two complementary reports by the Authority for Quality Assurance in Primary and Secondary Education (ADIPPDE) and the Institute for Educational Policy (IEP) were submitted. The proposals provided to the OECD review team following the fact-finding visit in May 2017 reflect lessons learned from the 2013 teacher evaluation reform which quickly foundered, as described above.

The ADIPPDE report notes the necessary elements of school self-evaluation as including:

the detailed mapping of the existing situation at school, where all aspects are registered, needs and problems are identified

the annual planning in each school unit, to include the design and implementation of improvement actions, and enabling schools to use evidence within their own context, to identify specific problems and decide upon corrective actions

the monitoring and evaluation of integrating improvement actions and the overall annual progress of the school unit

the final evaluation of all activities and processes implemented during the academic year in the form of an annual self-evaluation report, which is to include:

explicit indicators and criteria in order to highlight progress and good practices as well as needs, problems and points that require targeted support

a synthesis of the views of all teachers

annual school planning synthesising the directions put in place by the state, integrating the teachers’ vision for the school (ADIPPDE, 2017[44]).

The ADIPPDE proposal anticipates that teachers would work on SSE and planning prior to the start of the school year – typically teachers report for work ten days before school opening – and again at the end of the year. The SSE is to cover school infrastructure, resources, teaching and learning, school culture and climate, and student achievement. Teachers, parents and representatives of the local community would contribute to the development of plans and specific actions for improvement.

The ADIPPDE notes that SSE will also offer an opportunity to identify and disseminate good practices as well as trends at local, regional and national levels. They also emphasise that the “conclusions from the self-evaluation be used exclusively for feedback and formative purposes, and in no case will they be auditing or punitive”. The proposal suggests that this planning process will help to improve teacher collaboration and support professional learning. A “critical friend” (the regional school advisor), it is suggested, can provide additional objective feedback and mediate any internal disagreements. The resulting annual school reports would then be posted on a public web-based platform. Regional school advisors are to develop a joint report on the schools within their jurisdiction for the Head of the Scientific and Pedagogical Guidance of the Regional Directorate of Education. Reports with feedback are then to be generated (ADIPPDE, 2017[44]).

The IEP proposal builds on a school self-evaluation pilot about which the OECD review team was informed during its fact-finding visit. The pilot, in contrast with previous top-down attempts to introduce school self-evaluation in parallel with other evaluation approaches, was conducted on a small scale during 2011-13. The IEP, the pilot was based on a model developed by MacBeath (1999[45]), comprised of four key elements that prioritise school empowerment and self-determination:1

an overarching philosophy

a set of criteria or ‘indicators’

a toolkit.

The IEP researchers engaged with the project reported that the pilot went well, primarily because teachers understood that it was not linked to any kind of external control. The October 2017 proposal on Education Support Structures confirms this report and proposes greater pedagogical autonomy for schools and additional support for schools and teachers, including new regional centres of educational planning to support teachers at local level, and a stronger pedagogical and guidance role for school principals. Support for networking and collaboration among school “groups” and with supporting structures are also emphasised (Ministry of Education Research and Religious Affairs, 2017[43]). The proposal also suggests greater support for teacher collaboration to strengthen school improvement and as professional development, and to increase public recognition of educators’ work as part of the evaluation process.

It is apparent that Ministry officials have taken into account lessons learned from past efforts. The ADIPPDE and IEP proposals both suggested a scaffolded approach to building trust among teachers before introducing a more elaborated system of evaluation for improvement. The Ministry informed the OECD review team during its fact-finding visit that it also intends to hold itself more openly accountable to schools, communities and families. This is a strategic approach. However, to ensure that they can have long-term success both proposals require careful development of the details of the design and implementation, including the need to strengthen teacher buy-in and trust in this new system.

4.2.4. Enhancing the role of school principals

School principals have an important role to play in guiding school improvement and teacher development. Indeed, there is evidence that effective school leadership is key to student outcomes, second only to the quality of the teachers (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012[46]; Leithwood and Louis, 2011[47]; Robinson, Rowe and Lloyd, 2009[41]). Principals establish the school environment for great learning to take place, and sets expectations for students and teachers to succeed. Pont, Nusche and Moorman (2008[48]) highlight four core responsibilities of school leadership that are important: 1.) supporting, evaluating and developing teacher quality; 2.) goal-setting, assessment and accountability; 3.) strategic financial and human resource management: and 4.) collaborating with other schools. These roles however, also depend on the context, and their level of autonomy.

In Greece, the role of school principals, as reviewed in Chapters 1 and 2, is more administrative, as they do not have the responsibility for selecting or evaluating teachers or a high autonomy in resource allocation or curriculum. There have been recent changes in the selection of principals, moving towards greater school level inclusion in the selection process and input in the principal’s appraisal. However, it is important to consider not only the principal’s selection process, but also their specific roles and opportunities for career development, including the need for targeted initial training, their recruitment and selection, appraisal, and opportunities for ongoing professional development. The definition of the key role they are expected to play, which referred to as “school leadership standards”, can underpin efforts to develop principal professionalism.

The definition of standards is based on existing research identifying areas where school leadership appears to make the greatest difference: working with and supporting teachers in the school, setting directions, and developing the school. According to Pont, Nusche and Moorman (2008[48]), standards for principal performance are needed. It is particularly important to preserve principals’ roles in pedagogical management and support for teaching teams (principals’ key contribution to student learning) as their duties and responsibilities in other areas expand.

Standards for principals can define what they need to know and be able to do, thereby providing clear expectations for their performance. In fact, countries that have developed performance standards for school principals perceive them as a strategic tool in raising education quality (CEPPE, 2013[49]). These frameworks or standards may bring clarity, and guide the development of processes to strengthen principals’ roles, such as initial training, selection or continuous professional development. Frameworks and/or standards can also serve to signal the essential character of the principal’s role as leadership for learning.

It is important that leadership frameworks also include local and school level criteria. For example, in Australia five specific professional practices for principals have been set out:

leading teaching and learning

developing self and others

leading improvement, innovation and change

leading the management of the work of the school

engaging and working with the community (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2018[50]).

At a European level, a wider recognition of the need to enhance the role and support for school leadership has led to the development of the European Policy Network on School Leadership. This network has developed a set of policy kits for improving school leadership across Europe. In Ireland, school leadership draft standards were developed to support school principals’ self-evaluation (Irish Department of Education and Skills, 2015[51]). These draft standards also reflect expectations for school leadership in an education system that is characterised by a significant proportion of small and rural schools.

Recruitment processes have an impact on school leadership quality. There is a need to ensure that these processes are transparent and that criteria used can support selection of the most suitable candidates. At the system level, procedures and criteria need to be transparent, consistent and effective. School board members, often composed of individuals without an extensive education background, may need to be prepared for their role in selection of school principals. School-level involvement is critical to ensure the “fit” between the candidate and the school staff. In Greece, recruitment processes have recently been updated to include teacher votes in decisions related to hiring of their school’s principal. Rigorous selection procedures that go beyond traditional job interviews, that are based on clear standards and procedures, and that that include external professional stakeholders can contribute to selection of the best candidates (Pont, 2014[52]).

Additionally, an IEP proposal had recommended tri-annual evaluation of school principals, based on the Portuguese school self-evaluation model. In this model, the focus of each evaluation is on improvement; school principals receive feedback at the end of each year, and at the end of three years, they are to receive a summative assessment. All public school principals are evaluated without exception, as part of the required appraisal in their teaching career by members of the school governing board, whose views account for 60% of the evaluation, with the remaining 40% of evaluation given by an external school evaluation agency (OECD, 2015c[53]).

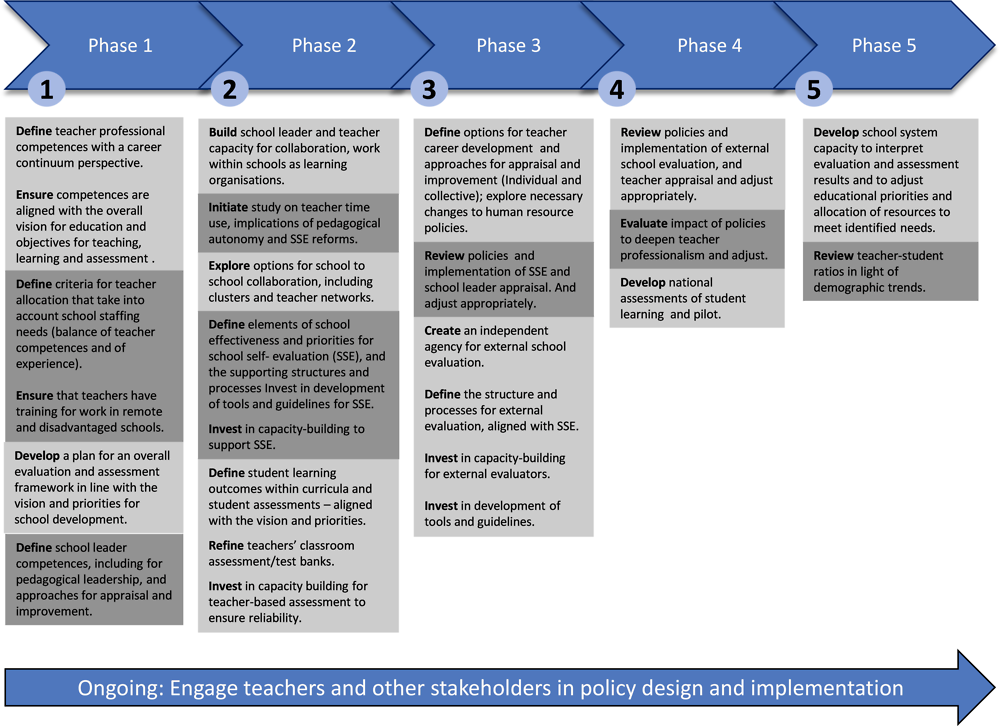

4.3. Policy recommendation: Support school improvement

Greece has a committed teaching body which is accomplishing average results. The policy options outlined in this section are intended to establish an environment where school improvement can take place: improving workforce management in terms of allocation and working hours, supporting individual and collective professional development of teachers and principals, and developing capacity and a strategy for evaluation and assessment for accountability and improvement. A particular focus on developing valid and reliable student assessments will be a necessary pre-condition for success.

4.3.1. Improve workforce management and efficiency for quality

More strategic approaches to teacher workforce management can help ensure resources are used more efficiently and effectively. As explored in this section, teacher allocation needs to be objective and fair, but to also consider the needs of schools and teachers. Teacher-student ratios need to be monitored to balance priorities to maintain small schools in remote locations and to support cost-effectiveness. Teacher time also needs to be used effectively, with more time devoted to core tasks of teaching and collaborative work with peers.

Teacher allocation

Teacher allocation needs to be objective and fair, but it should also make sense for schools and teachers. School principals need to have a greater say in the overall composition of their teaching staff in order to ensure that the overall team has complementary competencies. In addition, each school needs to have an effective mix of more experienced teachers (with some teachers having mentor status) and newer teachers. This is important for ensuring equity of provision – students in remote schools with inexperienced teachers may not have the same learning opportunities as those in more prestigious urban schools with experienced teachers.

Additional criteria may be considered within the placement decisions, as well. For example, for teachers who are from remote areas, proximity to their home town may also be considered. Training and experience in working with different types of students – for example with refugee learners – are also important. Currently, this type of experience is not taken into consideration, and valuable professional learning is lost with each new cohort of teachers. The burden of annual teacher relocation, which involves moving costs and in some cases, an increase in the cost of living, need to be taken into account, as well.

Teacher-student ratios

While teacher-student ratios are lower than the European average, the above analysis (Section 4.3) highlights the impact of Greece’s geography on the average teacher-student ratio in Greece. The choice to maintain small schools in remote communities represents a political decision to support those communities. Nevertheless, the Ministry should continue to monitor the data on teacher-student ratios in schools throughout Greece. Demographic trends in declining birth rates, new immigration, family relocation to urban areas, and so on, will have a corresponding impact on school and class size.

In addition, teachers should be provided with training to work with different types of classes. In remote areas, teachers may need targeted support to work with mixed-age classes. In larger classes, teachers may need training, including strategies for identifying and meeting diverse needs of students within the class. Training to manage student behavioural issues may also be needed.

Optimisation of teaching time

Teachers in Greece have fewer teaching hours, on average, as compared to teachers in other OECD countries and in the EU. This is in part because teachers have high administrative burdens, which may cut into teaching time. Another cause is that more experienced teachers are rewarded with fewer teaching hours. With growing numbers of teachers in the higher age bracket, this may have an important impact on overall teaching time.

Better use of teachers with more seniority time is needed. More experienced teachers may be provided with opportunities to mentor newer teachers. As schools are given greater pedagogical autonomy, more experienced teachers may also take leading roles in teacher collaborative work and in school self-evaluation and school planning. This may be part of a broader career strategy to prevent burn-out of older teachers and to capitalise on their experience. Streamlining of administrative procedures may also allow teachers to devote more time to working directly with students and colleagues.

A study of how teachers currently spend their working hours and the implications of new reforms granting greater school-level pedagogical autonomy and requiring school self-evaluation will be needed. This study should also identify opportunities to streamline routine procedures and to optimise time spent on substantive work. The focus needs to be on ways to increase efficiency as well as effectiveness.

4.3.2. Promote teacher professionalism with support for individual and collective development

A focus on teacher professionalism is central to any school improvement strategy. A professional competency framework can guide teacher policy. It can also take a career continuum perspective, with clear pathways for professional development and career growth. Teacher collaboration is also a key element in school improvement. Teachers need competencies to work in school-based teams and wider teacher networks. In turn, they may deepen their professional learning through this collective work. School improvement is supported as schools operate as learning organisations.

Develop professional competency frameworks for school principals and teachers

The IEP has recommended teachers be given greater pedagogical autonomy. As teacher opportunities to develop their own content and to innovate are currently fairly limited, this is a significant development. Teacher collaboration is also being encouraged through involvement in school self-evaluation and in teacher networks to support school improvement professional learning and development.