This chapter assesses the extent to which Småland-Blekinge has met the recommendations of the 2012 OECD Territorial Review of Småland-Blekinge across the 12 thematic areas. It focuses on where the region has seen the greatest accomplishments since 2012; where there is need for further progress; and where there has been a change in regional priorities.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge 2019

Chapter 2. Assessing the implementation of the recommendations

Abstract

The 2012 OECD Territorial Review of Småland-Blekinge provided a diagnosis and analysis of key social and economic trends in the region and assessed both the enabling factors for growth and well-being and the bottlenecks to development across a range of policy areas and domains – e.g. governance, transportation, education and skills. On the basis of this analysis, the territorial review forwarded 31 recommendations across 12 main thematic areas (see Table 2.1). This monitoring review assesses the progress that has been made in meeting these recommendations either in whole or in part across the four counties. This assessment is summarised in Annex Table 2.A.2.

Overall, it is found that the counties in Småland-Blekinge have made either notable progress or have met the recommendations in 12 of the 32 recommendations (around 38% out of total). This demonstrates great progress and commitment in a relatively short amount of time. Promisingly, the majority of these recommendations relate to key actors in Småland-Blekinge developing improved co‑ordination mechanisms and a more cohesive identity and common priorities. These improved governance frameworks and networks set the region on course for more effective co‑ordination in the future.

Of the remaining recommendations, it is assessed that the region's future direction has been well defined but that implementation has not yet started or that results are mixed in counties in the case of 10 of the recommendations (around 30% out of total). This monitoring review identifies a need for the region to improve its efforts to connect skills and education with labour market demand and for employers to be better linked with education providers. Furthermore, transportation connectivity remains a major challenge for the region. However, it is noted that the four counties have promisingly developed a cohesive strategy and common voice with which to lobby the national government. This growing cohesion bodes well for the region's future development.

Across 7 recommendations, it is assessed that no progress has been made (22% out of total). In some instances, this lack of progress is reflective of changing priorities. For example, the large wave of migration to the region starting in 2011 shifted a number of priorities such as youth engagement in regional development efforts. While youth engagement efforts continued to some extent in the interim, the need to rapidly mobilise resources to address migration made this a focused priority. Beyond this, it is noted that significant transportation challenges remain in such areas as air and freight transport. Some recommendations contained in the 2012 territorial review, such as the recommendation to strengthen the legal framework for public-private partnerships (PPPs), lay in part outside of the purview of the region's responsibilities. Finally, there are three recommendations that no longer remain relevant because conditions have changed (for example in the case of regionalisation reforms).

The following chapter presents an assessment of how Småland-Blekinge has met the recommendations across the 12 thematic areas. The chapter is organised in four parts. It first describes the areas where the region has seen the greatest accomplishments since 2012 and following this, areas of further progress. Next, the chapter discusses where the region has seen shifting priorities and finally, it examines the progress that has been made to date on the need for regional planning.

Table 2.1. Summary of recommendations: Territorial Review of Småland-Blekinge, 2012

|

# |

Theme |

Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Developing a knowledge-based economy |

● Develop knowledge-intensive businesses |

|

2 |

Addressing labour market mismatches |

● Strengthen the links between the regional education system and regional business ● Educate local communities about the importance of young entrepreneurs and provide support for their initiatives ● Increase the involvement of young people in regional development efforts ● Work with local industry to open up employment opportunities for foreign students ● Improve co‑ordination and collaboration in supporting migrant integration (including the labour market, training, social assistance and housing) and addressing the limited capacities of smaller municipalities ● Strengthen support and incentives for migrant entrepreneurship ● Improve the social recognition of female entrepreneurs and facilitate networking opportunities for them |

|

3 |

Quality of life |

● Better promote the regions natural and cultural assets to local people and potential migrants |

|

4 |

Tourism |

● Place tourism at the forefront of development efforts |

|

5 |

Small and medium-sized enterprises |

● Further promoting knowledge-intensive service activity firms, particularly those which are attracted to amenity-rich areas ● Design and implement strategies for business retention ● Better facilitate business succession amongst small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) through local business facilitators who can support business owners and broker solutions between sellers and buyers |

|

6 |

Improving accessibility to the region |

● Remove the main bottlenecks and improving road and railway connections to Malmö and Gothenburg ● Improve connectivity between larger towns/nodes and more sparsely populated rural areas ● Improve air transport from each of the four county capitals by improving scheduling that enables same-day travel to and from other European capitals via Stockholm and Copenhagen ● Improve freight transport infrastructure to take advantage of opportunities for trade with the Baltic States, the Russian Federation and China ● Improve co‑ordination between counties and the private sector in prioritising transport and communicating a single voice to the national government about them |

|

7 |

Better co‑ordination of business development efforts |

● Engage in more cross-border interaction and co-operation to avoid the territorial fragmentation |

|

8 |

Regionalisation reform |

● Undertake a cost-benefit analysis to determine the potential advantages and disadvantages of reform ● Clarify roles and competencies of agencies involved in regional development and how they interact ● Transition toward a model whereby a directly elected regional council is responsible for regional development ● Strengthen the bridging role of County Administrative Boards between central government and the regions, and simplifying the territorial boundaries of national agencies |

|

9 |

Regional Development Programmes (RDPs) |

● Develop more concrete and institutionally reinforced programmes with clear targets and measurable outcomes ● Establish an enforcement framework to link investment priorities with the objectives of RDPs ● Integrate rural and general development programmes into a single comprehensive regional development strategy |

|

10 |

Strengthen inter-county planning |

● Strengthen inter-county planning arrangements by including clear initiatives with funding and accountability and monitoring arrangements |

|

11 |

Further develop public-private interactions |

● Build institutional frameworks for public-private co‑operation like public-private partnerships or industry advisory groups ● Enable the legal framework for public-private partnerships |

|

12 |

Municipal co‑operation and reform |

● Initiatives and mechanisms that show co‑ordination across municipalities around common projects ● Establish place incentives and support to encourage inter-municipal co‑operation ● Conduct an in-depth assessment of municipal competencies identify opportunities for regional or national institutions to take on responsibilities, and/or develop an asymmetric approach (larger municipalities have responsibilities that smaller ones do not) |

Accomplishments since 2012

Co‑ordination between governmental institutions and regional actors has significantly progressed – this is central to meeting all other recommendations

Cross-institutional and county-wide co‑operation has improved…

The most consequential progress of the past five years lies in the increased cross-institutional and county-wide co‑operation and co‑ordination on all issues related to business and territorial development. Improvement in this area is the highlight of the monitoring exercise: it is a positive achievement that carries the potential to enable some of the changes further suggested in the 2012 OECD Territorial Review of Småland-Blekinge.

Five years ago, regional development and business promotion efforts were hindered by the fragmented actions of the different actors involved in regional and local development (i.e. the Regional Council, County Councils, Community Administrative Boards, municipalities, private, civic and business organisations). In 2017, all counties have reported greater alignment between those actors in seeking to build complementarities and work together toward a comprehensive vision for regional development. Substantive progress has been achieved through:

1. The establishment of an Innovation Council in Kalmar County.

2. Monthly consultations in Kronoberg County (networks for different managers).

3. Multi-stakeholder platforms in Blekinge County.

4. A corporate incubator in Kronoberg (företagsfabriken), which supports start-up companies to be developed with the support of senior business developers. The incubator also runs the Bravo entrepreneurial hub – a business development hub for entrepreneurs in start-up companies.

5. Jönköping County has established quarterly meetings with 2017 with all the actors involved in the business support system in order to increase co‑operation. New project ideas are also raised in the council. In addition, in spring 2018, the council has initiated a network on co‑operation on digitalisation of the business sector.

6. A cross-county agreement on infrastructure priorities for southern Sweden which feeds into Sweden's national infrastructure development strategy.

More precisely, the county of Kronoberg has progressed vis-a-vis strategic planning and administrative co‑ordination efforts. The county now holds monthly exchanges with municipalities and representatives from different sectors (e.g. school network), as well as bi-annual strategy meetings with politicians. Blekinge is showing important cohesion around migrant integration measures and business development projects such as the collaboration platform Blekinge Council. This platform involves the Blekinge Region, its five mayors, the County Administrative Board (CAB), Blekinge University of Technology, the Employment Service and business support agency (Almi) working together to strengthen the co‑ordination and implementation of Blekinge's regional development strategy. Similarly, Kalmar County which in 2012 exhibited divisions between the northern and southern parts of its county, has made significant progress in “unifying” the different municipalities around a county-wide vision. The recent process with the new Regional Development Strategy (adopted by the board in January 2018) is a confirmation of this; it has been a much smoother process anchoring the discussion with the municipalities and achieving consensus. There has also been more strategic co‑ordination through the creation of new platforms. The Kalmar Innovation Council – a network of innovation promoters – is one such platform: it meets once a month and involves representatives from different sectors who define action plans in order to boost and support the business environment. In Jönköping County, there are monthly meeting with all the directors from the municipalities, region, university and the CAB. The leading politicians from the region and municipalities meet to discuss these issues every second month.

With respect to infrastructure development since 2012, the counties of southern Sweden have strengthened the manner in which they communicate their priorities and concerns to the national government. They have adopted a unified voice in a number of areas including infrastructure, public transport, culture and regional development. The integration of 20 priorities of South Sweden into the recent national infrastructure development plan is a clear illustration of how greater levels of cross-county co‑operation can help the region carry forward objectives to the national level.

In all counties, the progress achieved in cross-institutional and county-wide co‑operation has been dependent on soft instruments for co‑operation. This co‑operation is based on personal relationships and the goodwill and interest of different actors to work on common issues through dialogue, networking and information exchange. Such collaboration is in line with Sweden’s notable consensus-building culture (Bergström, Magnusson and Ramberg, 2008[1]). While such mechanisms can translate into stronger co‑operation as observed in this case, there remains a risk that co‑operation will deteriorate when opinions diverge and conflicts of interest arise. In a context such as Sweden's, where municipalities are granted a large degree of autonomy, moving towards a greater institutionalisation of such meetings and designing incentive mechanisms could help to counter the potential negative scenarios driven by (poor) personal relationships between a small number of individuals. Furthermore, it may incentivise the organisation of meetings in which different sectoral representatives are gathered to discuss the interconnectedness of certain challenges – allowing for greater synergies to emerge in regional actions and initiatives. At present, in several counties, sectoral representatives do regularly meet with municipalities and cross-sectoral participation is not promoted. This is a missed opportunity.

…and so, has municipal co‑operation and reform

Inter-municipal co‑ordination has also improved. In 2012, it was found that municipalities – particularly larger ones – did not generally share a county-wide vision and saw few benefits in collaborating with their respective Regional Councils on the regional development strategy. Similarly, with the exception of infrastructure issues, the benefits resulting from building policy complementarities through inter-municipal collaboration were unclear. There continues to be no legal incentive for municipal co‑operation in the region of Småland-Blekinge, but the dynamics for collaboration have shifted in recent years. This has been driven in part out of the necessity to mobilise greater cross-municipal capacity to address the challenges linked to migrant integration, and partly because the regionalisation project was dropped.

Inter-municipal planning co‑operation in the different counties has most commonly been reported in the areas of infrastructure and housing (e.g. residual water and waste). Such an approach has been adopted in Jönköping, where four municipalities (Gislaved, Gnosjö, Vaggeryd and Värnamo) have voluntarily co‑operated in order to achieve economies of scale. Business development is another area in which shared municipal functions in some counties are evident. The four municipalities of Gislaved, Gnosjö, Vaggeryd and Värnamo co‑operate in business development in the form of Business Gnosjö Region. Kalmar County has manifested much greater inter-municipal co‑ordination – the two former sub-county municipal groups in the north and south of the county have merged into one unique county-wide co‑ordinated group. Now, since large regions are off the table, the unity among these actors has improved. In the upcoming merger forming Region Kalmar County, the 12 municipalities will form a formal federation for common interests and collaboration on issues like social welfare, education and environmental monitoring. In Kronoberg, the three municipalities of Kalmar, Karlskrona and Växjö have adopted a leadership stance in the drive for county-wide inter-municipal actions primarily related to infrastructure in the three municipalities.

While gains have been made in recent years, increasing capacity at the municipal level remains an essential concern across the four counties of Småland-Blekinge. The direct benefits of inter-municipal co‑operation tend to be more greatly felt by the smaller municipalities who share the same obligations as the larger ones but who may lack the competencies and capacity required to effectively meet their responsibilities. For instance, while central to any regional development strategy, spatial planning is an area of municipal responsibility that demands varying competencies and cross-sectoral considerations (e.g. housing, transportation, environment), often prompting the smaller municipalities to devolve this task to a third party. By doing so, municipalities risk losing an opportunity to build policy consistency with neighbouring municipalities and the county regional development strategy. Potential conflicts of interest could also arise that may guide the intentions of the external agents that the responsibility is devolved to. As such, while there is a long tradition of consultation with municipalities to work toward common priorities in the case of infrastructure investments, a similar formalised co‑operation is needed for skills capacity-building. As recommended by the OECD in 2012, conducting an in-depth assessment of municipal competencies in the four counties remains relevant but it is recognised that the options to rebalance responsibilities across levels of government or adopting asymmetrical solutions remains sensitive.

Business development and tourism branding: Where the dynamics of improved collaboration are most visible

Tourism branding among the three counties in Småland has increased

The three counties in Småland have made significant steps towards a cohesive tourism branding with the establishment of a common digital platform (visitsmaland.se) and have through this effort have developed consensus on which brand values should be promoted; a discussion which continues to evolve. The brand tagline is “Småland – Sweden for real”. This collaboration, if not friction-free, with its triumphs but also setbacks, is a major improvement compared to ten years ago, especially when Kronoberg and Jönköping Counties claimed the brand Småland. However, the collaboration only relates to branding and e-marketing/sales. The regions and destination do not co‑operate on development issues or combined offers. Blekinge is not included in this co‑operation as the county has its own tourism branding which is quite strong and with good public recognition. It operates its own digital platform (visitblekinge.se). Kalmar County has a separate challenge since a large part of its tourism is in fact not in Småland but in the landscape of Öland (Sweden’s second largest island), which has a unique brand with comparatively good public recognition in many parts of Sweden and key markets like Germany. The brand value of Öland is arguably the highest in all Småland‑Blekinge but the possibilities of collaborating with other destinations are limited since the brand values are quite diverse. There is however a strong link in target groups since both Öland and Astrid Lindgren's interpretation of Småland (most clearly manifested in Vimmerby) are both very strong amongst families with young children, in Scandinavia as well as in Germany.

Public support for value-added creation in firms has increased but developing a knowledge-based economy remains a slow process

The four countries have enhanced the levels of assistance that they provide in order for local industries to generate greater value in their products and services. Cost efficiency in traditional industrial processes has improved over the past five years. There has been a concerted effort to improve products, service quality and business processes. Examples of such practices are evident in the local processing of dairy products in Jönköping County; Kalmar County's integrated food strategy which benefits from research and development investments from companies; product internationalisation; and the business incubation centres in Kronoberg County.1

A number of local actors lie behind those efforts, including counties (e.g. Kalmar Innovation Council), municipalities, business support organisations (e.g. Almi) and higher education institutions (HEIs). For instance, Linnaeus University has recently adopted new university postgraduate programmes focusing on innovation in such areas as design, business and engineering. It has also enhanced its relationships with large employers such as the global furniture retailer IKEA (based in Älmhult, Kronoberg County), with whom it is creating a “life at home” niche. There is also co‑operation in forestry with the company “Södra”. The HEIs of the region have a central role to play in supporting this innovation promotion dynamic across a wider range of economic activities and in supporting the development of knowledge-intensive businesses. In 2018, Jönköping University launch its first MSc course in the field of industrial product design.

At the heart of those initiatives lay the opportunity for Småland-Blekinge to build on the competitive advantages of its counties to create market specialisation across the region. The relocation of the eHealth national agency in Kalmar County and the development of the bioeconomy sector in Jönköping County can foster productive gains, possibly facilitated through local smart specialisation strategies. Smart specialisation favours an integrated approach to economic development. In the case of Jönköping, it may help better integrate its forestry, climate and food strategies for the development of the bioeconomy sector, while in the case of Kalmar it may help better co‑ordinate IT sector innovation with public service delivery capacity. Likewise, in Kronoberg County where the IT sector has been steadily growing since the late 1990s and which today has one of the highest growth rates in Sweden, the adoption of local smart specialisation strategies could more effectively promote knowledge spill-overs from Växjö to the rest of the local economy. At present, many activities continue to be concentrated in one or two urban poles. The region should consider how smart specialisation strategies may have application in rural areas as well (see Box 2.1 for a discussion).

One recent positive development is that in April 2017 Jönköping University opened a research and education environment for knowledge-intensive product realisation (known as SPARK). The initiative aims to help manufacturing companies adopt more knowledge-intensive products and processes. SPARK is being developed in co‑operation with the Swedish Knowledge Foundation during the period 2017-26. The ten-year collaboration aims to create a nationally leading and internationally competitive research and education environment within knowledge-intensive product realisation, based on continuous co‑production between the university and partner companies.

Another significant and rather unique example of ambitious co‑operation is Småland China Support which was established in 2012. Kalmar and Kronoberg Counties together with the Linnaeus University then established their own permanent support office in Shanghai (China). The office has three full-time employees (one based in Småland and two in China) who work on two objectives: i) to support SMEs in the early stages of business in China: and ii) to recruit East/Southeast Asian students to the Linnaeus University (LNU). The business side of the operation currently focuses on four regionally strategic areas (wood industry, tourism, food industry and digital business). The office has been operative for almost 6 years with more than 200 clients and has proven itself to be highly efficient, contributing not only a considerable amount of actual business but also a greater knowledge and awareness of the opportunities in China amongst SMEs. The work mainly involves developing networks and personal relationships in China and connecting individual or groups of companies to these networks. The office also co‑operates with other Swedish public and private business promoting agents. Permanent representation in China with staff who know the conditions in both markets and who speak both Swedish and Chinese has been critical to the success of this initiative. The office has also recruited more than 1 000 tuition-paying students from China and other countries in East Asia, increasing the brand value of LNU in China and deepening the network of partner universities in Asia. Blekinge and Jönköping Counties have at different stages considered engaging in this initiative but have eventually chosen other priorities. Despite Småland China Support’s successes, its main weakness is the number and limited diversity of SMEs in the regional target group. There are many opportunities in China and a broader and larger base of companies in Sweden would increase the offers on the Chinese market.

Box 2.1. Smart specialisation for rural areas

It is not about technologies but about knowledge and its application

A smart specialisation strategy in rural regions is conceptually different than that of urban ones. In urban regions, smart specialisation approaches focus on expanding formal research in high-technology industries in order to increase the role of these fast-growth sectors in the local economy. Rural regions, in general, are not ideal candidates for this approach. Most lack a university or any other formal research centre. Very little of their economic base could be characterised as high-tech, advanced manufacturing or information and communications technology (ICT)-related. Furthermore, a relatively small share of the local workforce has an advanced degree or even a tertiary education. Low population density, small and dispersed settlement over a large geographic area limit interaction among people and firms. Similarly, small local markets and a small labour force make diversification and the opportunity for “related variety” innovations limited.

However, in a rural context smart specialisation can become a way to facilitate a stronger exogenous growth process. In a broad sense, smart specialisation is really a process that searches for evolving comparative advantage – as such it is useful in all regions. It is fundamentally a “bottom-up” development approach where the region determines its strategy on the basis of local capabilities. If the scope of the opportunities for support is expanded beyond the usual format of export-oriented high-technology products and formal research, then the concept becomes more generally applicable.

As noted by Charles, Gross and Bachtler, “Smart specialization should not be seen as being about technologies as such, but about knowledge and its application, and this applies to all sectors, even agriculture and craft-based industries” (2012, p. 6[2]). A large share of the firms in rural regional economies are small and medium-sized enterprises with no formal research and development activity, but in some cases considerable ability to innovate, although in ways that are not easily detected, since no patent is filed. Process innovations or innovations protected by trade secrets, or innovations that remain hidden because the firm is far from competitors, can be locally significant but do not neatly fit into a smart specialisation strategy. Innovations in the delivery of services or in goods that are not export-oriented are also not captured but can lead to increased productivity and an improved quality of life.

Strategies for rural smart specialisation

Charles, Gross and Bachtler provide five important reminders when developing regional smart specialisation strategies that are particularly relevant for rural regions (2012, pp. 45-46[2]):

1. The selection should reflect an existing competency, not simply an aspiration. It is also important that the projected demand for a particular good or service be large enough that providing it will have a noticeable impact on regional output and employment. There need not be an immediate increase, but there should be clear potential for significant growth over time.

2. It is important not to focus on the level of technology when identifying target sectors but on sectors that have future growth potential in the region. This could be in primary industries, such as forestry, fishing, mining or agriculture; in manufacturing, whether it is traditional heavy industry, boat building or specialised components; or in services including tourism, healthcare delivery or job training.

3. Regions should look for synergies that build on existing capabilities. By extending the local demand for an input, or by using a by-product from the production of a current output, the local economy can grow organically without having to establish a completely new production process.

4. Fostering innovation is a key function of smart specialisation strategy, but support for innovation should be applied where the potential benefits occur broadly and are not restricted to one or two specific firms. If an innovation is valuable to multiple firms in an important sector of the regional economy, then there will be stronger contributions to regional growth than is the case if the innovation only benefits a few firms with a narrow and small niche market.

5. In choosing sectors or activities to support, regions must be aware not only of their capability but also the potential of other regions. The underlying logic of smart specialisation is to support activities that result in tradable goods or services and while each region focuses on its opportunity to export, it must also assess the possibility that other regions may be better positioned, and are more likely to capture market opportunities.

These points reinforce the idea that smart specialisation has to do with expanding the competitiveness of regions through investments that increase productivity in those sectors that are ongoing regional strengths.

Source: Charles, D., F. Gross and J. Bachtler (2012[2]), “Smart specialisation and cohesion policy: A strategy for all regions?”, www.eprc‑strath.eu/public/dam/jcr:ca04731c‑2d7b‑490f‑a51e‑3e368b7ecfb6/ThematicPaper30%25282%2529Final.pdf.

In comparison to 2012, the local innovation ecosystem in Småland-Blekinge has become increasingly organised. New science parks and business incubators have opened in most of Småland-Blekinge’s counties (e.g. Blue Science Park in Blekinge and the Techtank technology cluster) and complementary institutional structures such as Kalmar’s Innovation Council have emerged to develop and implement local development strategies in business and innovation and there is collaboration between municipalities, the region, county councils, and Blekinge Institute of Technology (BTH) and science parks through the Tillväxtforum. After talks with many actors in the regional innovation system, Jönköping has developed a draft regional innovation strategy.

The common instruments used to support technology and knowledge diffusion indeed include physical infrastructure such as science or technology parks, incubators, although the quality and impact of these instruments depend on their design and implementation. The proximity factor is important for the latter. Physical proximity is an advantage which Småland-Blekinge can make use of for building and maintaining relationships given the generally small size of counties. Kronoberg is one of the most successful Swedish examples of how to leverage this advantage to promote an innovation system; horizontal co‑ordination has been achieved across economic areas and the ten organisations involved. The value generated in the innovation process by geographic proximity and face-to-face interaction also continues to be supported by evidence from OECD research, despite the widespread use of ICT to connect individuals (OECD, 2016[3]).

Despite improvements in Småland-Blekinge’s local innovation ecosystem, knowledge-transfer from HEIs to businesses remains weak and technology upgrading in local industries has been lagging behind as a result. In all counties, HEIs experience difficulties in liaising with local businesses due to a widespread lack of understanding of the value generated by the integration of postgraduate students and researchers in firms. This reluctance from firms, of small and medium-size most often, limits their capacity to successfully manage technology upgrading. In turn, a poor understanding of the pertinence of university-led research and innovation for private sector development continues to be shared by firms from, for example, the rural sector. In this context, innovation vouchers are instruments that can be used to promote further the use of academic expertise for business development in this era of technological change.

More systemic initiatives such as clusters, networks or competency centres are effective to support specific types of firms (start-ups or existing SMEs), while innovation vouchers or brokerage systems help firms access consulting services and knowledge (OECD, 2016[3]). Innovation vouchers are presently used in Blekinge, Jönköping and Kalmar Counties. For example, Kalmar County has developed a system with innovation vouchers which is not limited to finding support in universities but can also be used for acquiring innovation support from commercial actors or, preferably, one of the national industrial research institutes. The voucher covers 50% of the costs and contra-financing can, if the project meets certain conditions, include the innovators own time (as a defined hourly rate) for prototyping, etc. The terms are quite generous and the process time is normally around a week; despite this, the utilisation of these instruments is surprisingly low. This could be due to a lack of time on behalf of firms to undertake this work or perhaps a lack of knowledge.

Box 2.2. Supporting innovation in SMEs: The use of innovation vouchers

Innovation vouchers are small lines of credit provided by governments to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to purchase services from public knowledge providers with a view to introducing innovations (new products, processes or services) in their business operations. Innovation vouchers normally target SMEs in light of the contribution (normally below EUR 10 000) they provide for the introduction of small-scale innovations at the firm level. SMEs tend to have limited exposure to public knowledge providers such as universities and research organisations as they may see such institutions as irrelevant to their business activities or be unwilling to invest in the search costs necessary to identify relevant providers. On the other hand, staff in public knowledge providers may see little incentives in working with small firms when the latter have lower absorptive capacity and guarantee lower returns as compared to large companies and other public agencies.

The main purpose of an innovation voucher is to build new relationships between SMEs and public research institutions which will: i) stimulate knowledge transfer directly; ii) act as a catalyst for the formation of longer-term more in-depth relationships. In a snapshot, innovation vouchers are intended as pump-priming funding through which initial industry-university relationships can be established.

The issuing of the voucher has two main impacts, both of which overcome major incentive barriers to the usual engagement between SMEs and knowledge providers:

1. The voucher empowers the SME to approach knowledge providers with their innovation-related problems, something that they might not have done in the absence of such an incentive.

2. The voucher provides an incentive for the public knowledge provider to work with SMEs when their tendency might either have been to work with larger firms or to have no industry engagement at all.

Success factors for the use of innovation vouchers

The wide recourse to innovation vouchers (e.g. Ireland, the Netherlands, the West Midlands in the United Kingdom, etc.) demonstrates that, thanks to its simplicity, the measure can be easily adopted by countries and regions worldwide, provided that small firms have a minimum “absorptive capacity” towards university research and that universities and public research institutions are willing to co-operate with industry. Innovation vouchers are traditionally used to solve minor technological problems or scope out larger technological issues. As such, they are useful instruments but need to be integrated into a wider innovation strategy in which voucher recipients can refer to other policies for further stages of business innovation. Examples include collaborative research programmes, incentives for internal research and development, clusters and networks for innovation, etc.

Limited evaluation evidence suggests that output additionality for this measure is high, i.e. a large share of firms that are granted vouchers would not have undertaken the project without public support. However, the impact on longer-term SME-university collaboration is more limited and questionable. On their own, innovation vouchers appear too small a tool to change the embedded attitude of SMEs towards research organisations.

A few conditions make this tool more feasible and likely to succeed. First of all, the voucher should be directly administrated by a public agency, whereas there are some cases in which it was also managed directly by a university. Whilst this causes more costs for the public sector, it presents three main advantages: i) it avoids any potential conflict of interest between the university as a scheme operator and knowledge provider; ii) it may allow a more dedicated approach to the operation of the scheme than the wider mission of a university may permit; iii) there may be greater scope for follow through with other supports for innovation if the scheme is administered by a development agency.

Second, brokering is crucial to the feasibility of the programme. There is a need both to minimise the application burden on firms and to provide cost-effective matching to appropriate academic expertise. For instance, too much an arm’s length approach by the delivery agency may lead to difficulties for firms in finding appropriate academic partners and for knowledge providers in responding to a relatively high volume of unco‑ordinated enquiries. Developing an enhanced brokerage service is crucial to the effectiveness and popularity of the programme by enabling firms to more quickly identify possible partners and reducing the load on knowledge providers.

Source: OECD (2018[4]), Innovation Vouchers, OECD International Migration Statistics (database), http://www.oecd.org/innovation/policyplatform (accessed on 15 February 2018).

Småland-Blekinge’s current favourable economic climate may explain the disincentive for companies to engage in more technology-intensive activities (see Chapter 1) and the lower prioritisation by local actors of the OECD recommendation on supporting the development of a knowledge-based economy. Yet, continuous efforts should be mobilised in this direction. Such actions remain critical because the industrial base of most counties in Småland-Blekinge remain dominated by manufacturing and characterised by low-value creation within the regional economy. The local business community should seize upon these strong local conditions to engage in the strategic changes that will contribute to increasing their knowledge intensity, their value added and competitiveness, making them and the local economy more resilient to any future economic slowdown.

Lastly, it is noted that certain actors in the local economy may have interpreted the OECD’s recommendation in this area as a call for the development of new industries rather than support for the existing business fabric to transition toward higher-knowledge intensive activities. With the growing organisation of the region’s innovation system, it is important to take a broad view of innovation. As Wintjes and Hollanders note (see 2.3), innovation is fundamentally about the ability to adopt and adapt new knowledge (Wintjes and Hollanders, 2010[5]). This pertains as much to existing industries and processes as it does to newly emerging ones and should encompass a broad range of activities, including public service provision, government organisations and administration.

Building diversity in the economy and exploring new avenues in knowledge-intensive activities can only strengthen the economic profile of the region, but such an endeavour should not be pursued at the detriment of the local industrial business community which may be left behind. A deviation of the attention and prioritisation to support existing industries in their growth development is not advisable. Efforts should continue to be oriented toward improving the competitiveness and processes of the prevailing local economic capacity.

Box 2.3. Beyond technology-driven innovation

Focusing on “demand-driven” innovation

While national governments largely continue to emphasise technology-driven innovation as the core of smart specialisation strategies, academic research is increasingly arguing for a more nuanced approach that includes “demand-driven” innovation in the form of applications, entrepreneurship, user-driven innovation, and innovation in services and organisations (Wintjes and Hollanders, 2010[5]). The shift includes a recognition that while the production of inventions may continue to be concentrated in a small number of metropolitan regions, all regions can benefit from adopting these inventions in the form of regional innovations. It is the ability to adopt and adapt new knowledge that separates higher growth regions from slower growth ones (Wintjes and Hollanders, 2010, pp. 17-19[5]).

In a survey of experts on the most important sectors for future regional economic development and the most important technologies, Wintjes and Hollanders find hotels and restaurants; health and social work; and agriculture, forestry and fisheries were the 5th, 6th and 7th highest ranked, ahead of computer and data services, pharmaceuticals, software, and aircraft and spacecraft (2010, p. 29[5]). The high rank of traditional industries suggests that the experts believe that innovation in these sectors can have a much larger impact across regions than is the case for the more advanced industries because they are so pervasive in many countries (Wintjes and Hollanders, 2010, p. 28[5]). Similarly, when the experts were asked to pick the most important technologies for the future, the most mentioned was ICT, but alternative energy was second and process control and agricultural and food technologies were in the top 20 (Wintjes and Hollanders, 2010, p. 30[5]).

The larger point made in the study is that there is considerable opportunity in traditional industries for future economic growth and that regions, where there is a strong comparative advantage in these industries, should carefully assess how they can invest in increasing the competitiveness of local firms as a central element of their smart specialisation strategy. While these sectors may not benefit from the push effect of formal research and development investments, they can benefit from the demand for product or process improvement, and there are opportunities for small-scale innovations by entrepreneurs and existing SMEs based on local knowledge. Finally, the importance of regions importing inventions and knowledge developed elsewhere and using it for local innovations cannot be overemphasised as a way to increase the competitiveness of local firms.

A broader understanding of innovation (beyond new technologies alone) is needed in order to apply smart specialisation policy in low-density areas. Almost by definition, low-density areas lack vital parts of the usual way that smart specialisation processes are described. They are too small and open to trade effects to have an endogenous growth process. They lack formal research capability in the form of large universities, government research facilities and corporate research centres. They lack the dense networks of firms, organisations and other institutions that are thought to be central to innovation. However, when innovation is extended to include a broader range of activities, including public service provision, government organisations and administration, tourism and the creation of “third-sector” solutions to social concerns, there are obvious examples of these forms of innovation occurring in large metropolitan regions and in small remote rural regions.

Sources: Wintjes, R. and H. Hollanders (2010[5]), “The regional impact of technological change in 2020”, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/studies/2010/the-regional-impact-of-technological-change-in-2020; Wintjes, R. and H. Hollanders (2011[6]), “Innovation pathways and policy challenges at the regional level: Smart specialization”, United Nations University, Working paper series 2011-027.

Box 2.4. Rural innovation: The case of Nordland, Norway

Nordland is a region located in northern Norway and has 240 000 inhabitants, and the largest city, Bodo, has a population of close to 50 000. The land and topography of the region are diverse with fjords, high mountains, narrow peninsulas and islands. Nature-based attractions such as the Lofoten Islands are critical for the region’s tourism industry. Forestry and agriculture have also developed in the valleys and coastal areas. As a result of this physical environment production is dispersed across the region – some in locations which are remote and difficult to access.

Nordland has a rich endowment in terms of water resources, landscapes, productive land and mineral resources. These resources provide the foundation for mining, agriculture, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture, and tourism. These industries are performing strongly and are integrated into global markets. They make an important contribution to the economic prosperity of Norway. However, these highly productive and export-oriented industries are not generating significant new jobs for the region (with the exception of tourism). How the region overcomes this “growth paradox” to capture greater value added and jobs in the region will be critical to the future of the region.

In terms of skills and innovation, the region has a number of key strengths and challenges. The region has one university, two university colleges and three research institutions. These institutions are increasingly engaged with local businesses and research and development investment is rising. The county has recognised the importance of innovation and was the first region in Norway to have its own research and development strategy, which has provided a platform to forge closer links with local businesses. However, the region has an ageing population and lower educational attainment than the rest of the country. Although research and development activity is increasing, it still lacks scale and there is not a strong culture of innovation amongst smaller businesses in traditional industries.

Enhancing the competitiveness of tradable sectors outside of oil and gas is challenging in Norway, which has a high-cost base.

The region has adopted smart specialisation as a framework to promote innovation within the region’s tradable sectors. The county’s smart specialisation strategy – Innovative Nordland – has identified the process industry, seafood and tourism as key opportunities for future growth. The county has three key strategies to shape innovation outcomes:

supporting co-operative projects between business and research and development institutions

brokering education projects within clusters

supporting competency building in universities and research and development institutes that aligns with cluster development in the region.

The development of this strategy involved close collaboration between the public sector, business, and research, education and training organisations in the region. Priorities were identified using techniques such as Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) analysis and foresight planning to reveal the region’s comparative advantages. The design and delivery of this strategy also involve co‑operation and peer review with the region of Österbotten, Finland. Collaboration, consistent and transparent methodologies to identify strengths and peer-review have all been identified as success factors within smart specialisation strategies in a European context (OECD, 2013[7]).

Sources: OECD (2017[8]), OECD Territorial Reviews: Northern Sparsely Populated Areas, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264268234-en.; OECD (2013[7]), Innovation-driven Growth in Regions: The Role of Smart Specialisation, https://www.oecd.org/innovation/inno/smart-specialisation.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2018).

Formal public-private partnerships have not materialised but public-private co‑operation is more widespread than before

Public-private co‑operation has grown over the past five years, in the counties of Blekinge and Kronoberg particularly. The improved public-private co‑operation is reflected by the increased involvement of Almi, Sweden’s business support agency, in public initiatives in the four counties and the stronger collaboration between HEIs, local science parks and incubators. Unlike in 2012, the obstacles in the legal framework for the formation of public-private initiatives for regional development therefore no longer seem to be prevailing.2 However, public-private co‑operation does not go beyond business development initiatives. Encouraging greater participation and contribution of the private sector may yet benefit other areas of strategic regional development in Småland-Blekinge. In Jönköping County, the Science Park has local representatives in all 13 municipalities, which may promote public-private co‑operation.

Three of the counties co‑operate in tourism with a common brand (Visit Småland) and all four have their own more operational strategies as well

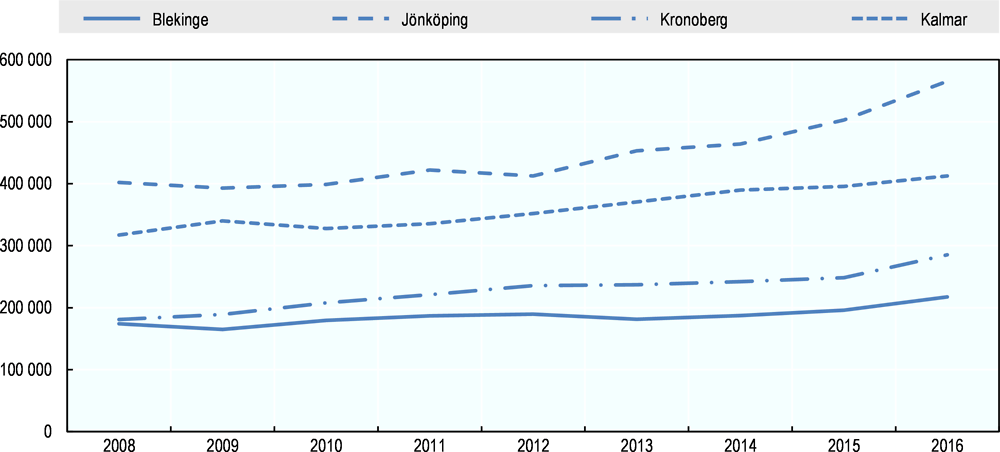

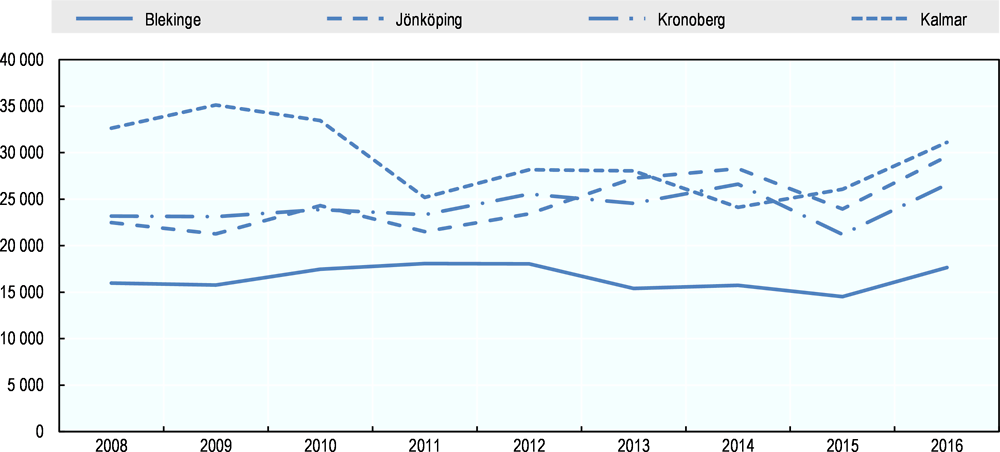

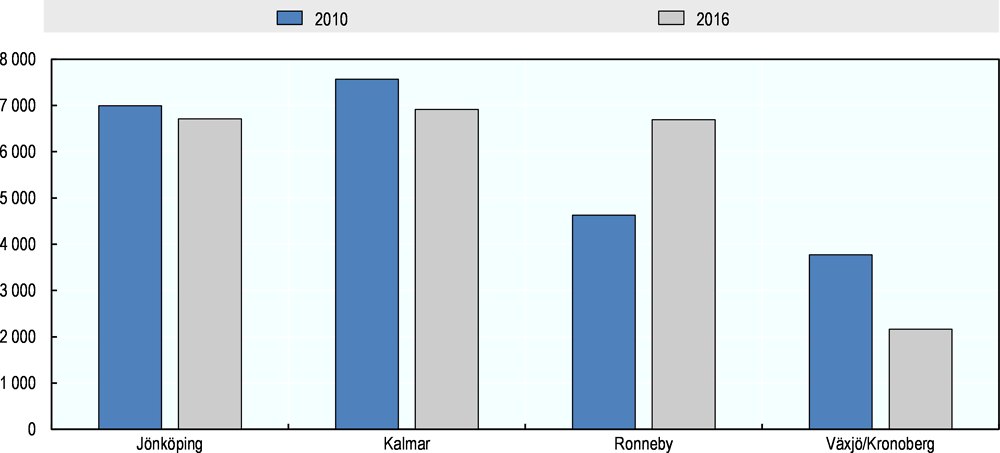

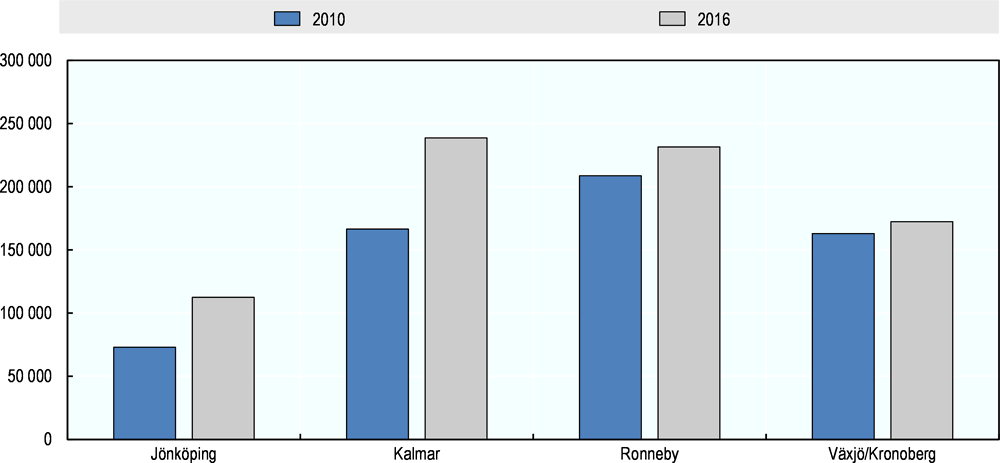

Over those past five years, tourism has expanded in Småland-Blekinge. Hotel revenues went up in all counties between 2008 and 2016 (Figure 2.1). Jönköping remains the most popular county of the region and is the county in which revenues have increased the most. Private cottage and apartment rentals also picked up in recent years, although not reaching pre-crisis levels yet (Figure 2.2). In the same period, there has also been an overall increase in the creation of establishments (i.e. hotels, holiday villages, youth hostels) to serve the tourism sector in Småland-Blekinge (Tillväxtverket, 2018[9]). Kalmar, followed by Jönköping, is the county that registers the highest number of establishments and it is also one of the two counties, with Kronoberg, in which the increase has been most visible; thereby showing the commitment of those counties to strengthening infrastructure quality and the tourism industry in the region more generally (Tillväxtverket, 2018[9]).

An additional development since the 2012 Territorial Review is that each of the four counties now possesses its own county brand for the international tourism market.3 With “Blekinge Wonderful Water”, the county of Blekinge recently defined its tourism identity in relation to the element of water, which links directly to the promotion of its coastline assets. The strategy in Blekinge led to the formalisation of the organisation Visit Blekinge with the mission to market Blekinge outside of the county´s borders. Kronoberg County has been the main instigator of the “Småland” brand which encompasses a larger inter-county geographical scope. Similarly, Jönköping County chose to follow the strategy it had prior to 2012 with a county-wide promotional focus essentially targeted at the “nature-loving” foreign Dutch tourists. Kronoberg's approach is similar to Jönköping's while Kalmar – the most tourism-intensive region of the four – to a large extent uses a fragmented approach where the five major destinations (private/public) take full responsibility for their own development and domestic marketing. Kalmar is, for instance, developing a niche tourism market attracting Chinese visitors which likely results from the increase in foreign direct investment projects with China in recent years (involving Småland China Support). The regional level is responsible for international marketing and certain competencies and development projects. Since 2018, the regional level has been better-resourced to develop the regional competitiveness in the tourism industry.

Figure 2.1. Hotel revenue in Småland-Blekinge

Source: Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (2018[10]) (2018), Tourism Statistics, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/turism.html.

Figure 2.2. Commercially arranged private cottage and apartment rentals in Småland-Blekinge counties

Source: Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (2018[10]) (2018), Tourism Statistics, https://tillvaxtverket.se/statistik/turism.html.

While tourism in Småland-Blekinge has been gaining traction, the international outreach of the region needs to be further developed. Significant steps have been taken in Småland since 2012 to create joint branding under the brand name “Sweden for real” and a common marketing and sales platform (visitsmaland.se). Synergies should be built across the different counties’ tourism strategies to enhance the regional brand. With the exception of Kalmar County, investments in the tourism industry are seen as carrying a lighter weight for local development than investments in ICT or industrial projects. Yet, the importance and contribution of the tourism sector to the local economy of the region is not negligible and can be boosted through a strategic territorial branding campaign as developed by French and German regions (Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Territorial branding strategies: Experiences from Brittany (France) and Nuremberg (Germany)

Territorial branding can be an effective strategy for regional development, if well-articulated and well-promoted. One lesson from place-branding is that a clearly identifiable brand is more beneficial than many different segmented ones. Investing in several different brands for the same place can limit the impact of the marketing strategy and create market confusion.

Produit en Bretagne

The case of the brand Produit en Bretagne (Made in Brittany) in France shows how shared values and collective efforts to expand and solidify the brand can yield positive results. The oldest regional food brand in Europe, Produit en Bretagne was created in 1986 to strengthen the solidarity and employment of the region. Since then, an association of producers was created, which includes today members of the service sector such as hotel, restaurants and cultural and creative sectors. The association facilitates the engagement of an array of stakeholders, who exercise quality controls over products and agree on the marketing strategy. The association successfully created a business incubator to support innovative projects, too.

This example also signals the importance of participatory territorial branding, i.e. of involving local stakeholders in brand development and consolidation. Promoting synergies and consensus among regional stakeholders has been identified as one of the key elements in keeping a brand alive and well in the long run.

Nuremberg Metropolitan Region

In the Nuremberg Metropolitan Region, creating a common identity was instrumental to develop the territorial brand of the region (OECD, 2013[7]). Building territorial identity can involve a process of identifying local strengths and weakness, creating trust and defining directions for future change. This process further enables common action and strategies to take place.

One step in this process was to promote internal tourism, by encouraging residents to “rediscover” their own territory, with the Discovery Pass. The metropolitan authority also invested in the accessibility of the regional transport system, with broader coverage and an integrated fare system. Increased daily commuter traffic contributes to regional economic cohesiveness.

The territorial branding process in Nuremberg was further backed up by a strong cluster policy. It includes comprehensive projects of renewable energy production, innovation and entrepreneurship in healthcare, regional trade fairs and a knowledge-sharing and network-building platform called Original Regional (OECD, 2013[7]). The branding policy can showcase the Nuremberg region as having “original” products and assets whilst also being able to develop research and generate innovation.

Sources: OECD (forthcoming[12]), Productivity and Jobs in a Globalised World: (How) Can All Regions Benefit?, OECD Publishing, Paris; OECD (2013[7]), Innovation-driven Growth in Regions: The Role of Smart Specialisation, https://www.oecd.org/innovation/inno/smart-specialisation.pdf.

The multi-functionality of tourism for rural areas, if well managed, can create positive externalities by opening up access to local amenities that will not only make sites attractive to foreign visitors but also improve the quality of life of local residents. Service-based businesses and entrepreneurial ventures linked to tourism can create social and economic opportunities. The OECD Rural Policy 3.0 framework emphasises the importance of a diversified rural economy (Box 2.6). Rural policies should consider the specific features of diverse territories and should promote new economic opportunities for rural communities (i.e. in non-farm employment, alternative products and services) (OECD, 2016[11]). In this vein, the Rural 3.0 framework encourages a bottom-up approach that mobilises the diverse set of actors contributing to the development of rural areas. The tourism sector can be a central pillar to any country or region’s rural development strategy but tends to be more strategically developed when integrated into a framework that considers important the alignment with other policy areas (e.g. road, rail, supply of accommodation facilities, public services, etc.).

Box 2.6. The OECD rural policy framework: Rural Policy 3.0

In 2006, OECD member countries adopted the New Rural Paradigm as a core approach to developing better rural policy. The main principle of this approach was that rural territories can be places of opportunity but, for these places to achieve their potential, a spatially sensitive development approach is required. The key elements of the approach are:

Recognition that rural areas are now much more than only agriculture.

A shift in philosophy from supporting rural areas through subsidies or entitlements to focusing support on investments to increase competitiveness.

Belief that rural people have a better sense for their local development opportunities than national governments, which leads to a “bottom-up” approach.

Recognition that there are multiple actors that must be engaged in the rural development process, not just national governments and farmers (OECD, 2006[13]).

Since 2006, the OECD has engaged with a number of member countries to conduct rural policy reviews in order to gauge how existing rural policies in each country conforms with the principles of the New Rural Paradigm and to offer advice on how to reform those policies to make them more effective (Freshwater, 2014[14]). Policy advice is based on evolving academic and practitioner research and on the identification of effective rural policies in member countries. In addition, the OECD has investigated some key thematic topics in co-operation with member countries, including rural service delivery, the role of renewable energy in rural development and the nature of the linkages between urban and rural areas.

In 2016, the New Rural Paradigm was updated with the Rural Policy 3.0, which reflects the new knowledge acquired in the intervening decade (OECD, 2016[15]). This approach builds upon the New Rural Paradigm with the intention of moving from a “paradigm” towards more specific policy recommendations that can help countries with policy implementation (Garcilazo, 2017[16]). The core idea in Rural Policy 3.0 is that economic growth occurs in different ways in rural areas than it does in urban ones. The rural growth process takes place in a “low-density economy” where agglomeration effects do not occur and distance plays an important role in production costs and the lives of the people. Moreover, because the opportunities and constraints in different types of rural places vary, so does their economic function. Rural economies tend to have niche markets because they are small and specialised, except for those places producing natural resources, such as agricultural commodities, minerals or forest products.

Table 2.2 illustrates the evolution of OECD thought on rural policy. The advice for policy implementation is fairly abstract, reflecting the fact that, for any country, variability in regional conditions and in national objectives makes it impossible to provide specific policy advice. Even for specific rural policy reviews, it is difficult for the OECD to develop policy advice that goes much beyond basic principles. To do so would require more information and analysis than is available and a far better understanding of how rural policy fits into the larger set of policy concerns for that national government.

The value of the OECD approach remains its potential to apply a coherent analytical framework to thinking about rural policy. A country that engages in the process receives some basic advice on how to think about policy but must still develop specific policies on its own. Because the OECD policy framework emphasises the importance of a bottom-up approach and the inherent diversity of rural areas, national governments have to be willing to engage in joint development strategies with local counterparts. It is in only through this process that specific policies are developed.

Table 2.2. Rural Policy 3.0

|

Old paradigm |

New Rural Paradigm (2006) |

Rural Policy 3.0: Implementing the New Rural Paradigm |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Objectives |

Equalisation |

Competitiveness |

Well-being considering multiple dimensions of: i) the economy; ii) society; and iii) the environment |

|

Policy focus |

Support for a single dominant resource sector |

Support for multiple sectors based on their competitiveness |

Low-density economies differentiated by type of rural area |

|

Tools |

Subsidies for firms |

Investments in qualified firms and communities |

Integrated rural development approach – spectrum of support to the public sector, firms and third sector |

|

Key actors and stakeholders |

Farm organisations and national governments |

All levels of government and all relevant departments plus local stakeholders |

Involvement of: i) public sector – multi-level governance; ii) private sector – for-profit firms and social enterprise; iii) third sector – non-governmental organisations and civil society |

|

Policy approach |

Uniformly applied top‑down policy |

Bottom-up policy, local strategies |

Integrated approach with multiple policy domains |

|

Rural definition |

Not urban |

Rural as a variety of distinct types of place |

Three types of rural: i) within a functional urban area; ii) close to a functional urban area; iii) far from a functional urban area |

Sources: OECD (2016[15]), “Rural Policy 3.0”, in OECD Regional Outlook 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264260245-7-en; Freshwater, D. and R. Trapasso (2014[14]), “The disconnect between principles and practice: Rural policy reviews of OECD countries”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/grow.12059; Garcilazo, E. (2017[16]), “Rural Policy 3.0 productive regions for inclusive societies: Low density economies: Places of opportunity”, https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/s4_rural‑businesses_rural‑policy_garcilazo.pdf; OECD (2006[13]), The New Rural Paradigm: Policies and Governance, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264023918-en.

Internal mobility and broadband connectivity improvements will benefit regional well-being and attractiveness

A strong emphasis is placed on expanding public transport

Within the realm of infrastructure and connectivity works, internal mobility is the domain in which most progress has been made across the region. In the counties of Småland-Blekinge, the focus has been put on increasing the efficiency of the public bus system. This new infrastructure not only improved accessibility within the county but it also changed commuter behaviour. In Kalmar and Kronoberg Counties, a new corridor system was created which increased the frequency of public buses; all buses being 100% climate neutral, functioning on biogas or HVO biodiesel.4 Fossil CO2 is virtually eliminated from all public transport operated by the regional public transport company KLT. This includes also all minibuses, public transport taxis, etc. (almost all private buses and taxis are also biofueled or electric/hybrid since this is a common customer demand). Blekinge also has a large share of renewable fuels in its public transport system and has emphasised a corridor system for public transport; the modal share of public transport has increased in the county in recent years.

The counties of Småland-Blekinge are taking a strong environmental stand which is also emphasised through the development of new bike lanes in all counties. The importance of internal mobility and the prioritisation of more sustainable modes of transportation has thus increased since 2012 and marks a shift from the mostly rail and road (i.e. private cars) focus in infrastructure planning that predominated five years ago. Measures such as those can both contribute to positively raising the well-being levels of residents, mainly through greater proximity to services from remote areas and by increasing the attractiveness of counties and the overall region. It is noted that there remains a strong focus on improving rail infrastructure in the region since little progress has been made on making road transport more sustainable. The need for better, more efficient and safer road infrastructure remains. However, better road infrastructure will inevitably increase demand and correspondingly CO2 emissions. Since the possibilities to regionally influence the share of CO2-neutral road vehicles are very limited, the only possibility that remains is to increase bio-fuelled and electric public transport.

Nonetheless, data collection on travel inflows by road, bike ownership and bike use for going to work journeys, as well as data capturing the shift toward more electrified modes of transportation which are currently unavailable would be welcome so as to develop a better understanding of the economic and social returns from adopting more sustainable and efficient internal transport systems. Some data collection on these topics is initiated and done regionally but some gaps remain.

There is a unanimous commitment towards enhancing digital connectivity

How to bring digital connectivity to rural areas and a country’s most remote places is debated across all OECD countries and regions. In a recent strategy document, the Swedish government set the national target of at least 95% of all households and companies having access to broadband with at least 100 Mbit/s by the year 2020. This national target has influenced each county in Sweden to set and meet similarly ambitious goals and the national government has assigned broadband co‑ordination to the counties. In Småland-Blekinge, county targets vary from 90% to 100% coverage. All counties of Småland-Blekinge show significant increases in broadband connectivity at 100 Mbits deployed both in the home and work environments (Chapter 1).

Digital connectivity was not a primary subject of recommendation in the 2012 territorial review, but it certainly was pointed out as an essential piece of infrastructure to improve service provision and business attraction in the region. In some aspects, access to broadband can help overcome physical distances, road and rail infrastructure challenges by giving people the possibility of having a full-time professional activity working from home and living close to the natural amenities that constitute the wealth of the region and a key point of attraction for those residents. Digital connectivity is an instrument that can significantly help strengthen labour markets, skills to jobs matching and the local entrepreneurial business environment.

As in the rest of Sweden, interest in telemedicine has gone up in the region over the past few years. One factor driving the increasing interest in telemedicine is the difficult access to health facilities, qualified physicians and specialists, particularly. As telemedicine relies on high-speed Internet services to connect patients with healthcare providers, pushing for its development may well be the secret to advancing broadband itself in underserved communities, both rural and urban. Telehealth is not a specific service but a variety of technologies and tactics to deliver virtual medical care, wellness, health awareness and education in a holistic manner. Broadband is a major part of that delivery mechanism.

There is a large potential for Småland-Blekinge to develop a “continuum of care”; that is, a system providing a comprehensive array of healthcare spanning all levels and intensity of care. The presence of a strong IT cluster concentrated in Blekinge and Kronoberg Counties and the relocation of the National Health Agency in Kalmar County are all factors that can support the creation of new technologies and services in Småland-Blekinge and help raise the profile of the region in the field of eHealth. Blekinge’s success with the e-healthcare project “Sicaht” is a case in point; it has led to a permanent focus area on eHealth within Blue Science Park. A “healthcare hub” that uses broadband to link a city’s or county’s hospitals, clinics, other healthcare providers and private practices can strengthen and expand the continuum of care. Healthcare institutions in Småland-Blekinge could align with schools and libraries that have telemedicine applications and services into a healthcare hub. By doing so, the infrastructure available to communities may not only be further strengthened but community funding may also be more easily mobilised.

The cost-benefit analyses driving decision-making on the question of whether to provide digital connectivity to sparsely populated areas most often underline the costly engagement that it will represent for any given local economy. In Småland-Blekinge, the speed by which each county will be able to meet its target will largely depend on the responsiveness of private providers to market incentives in a first stage and, in a second stage, on the capacity of public companies, community associations and municipalities to finance such a service to the areas that lack critical mass and remain underserved. In the counties that set a target of 100% successful county-wide coverage, considerations around the establishment of public-private partnerships or the mobilisation of county resources were also expressed as the potential solution to remedy remaining gaps in coverage. While counties’ perspective may differ on how to best finance digital connectivity, the economic and social value generated by the provision of such a service even to the most remote areas is recognised unanimously. There is a growing concern that the gap between the most and least connected areas will further increase in the roll-out of 5G networks. Accessibility to 5G is critical to the development of IoT (Internet of Things) for all kinds of purposes, autonomous vehicles, high-automation of industry, virtual reality, augmented reality and many services just waiting to be created.

Box 2.7. Deployment of fibre optical networks through collaborative approaches

As an increasing amount of economic and social activity is undertaken over communication networks, it becomes more challenging to be restricted to low-capacity broadband when living in some rural or remote areas. Given that most countries have regions that are sparsely populated, it raises the question of how to improve broadband access in these areas.

There is a growing “grassroots movement” in Sweden to extend optical network fibre coverage to rural villages. There are around 1 000 small village fibre networks in Sweden, in addition to the 190 municipal networks, which on average connect 150 households. These networks are primarily operated as co-operatives, in combination with public funding and connection fees paid by end users. People in these communities also participate through volunteering their labour or equipment as well as rights of way in the case of the landowners. The incumbent telecommunication operator, as well as other companies, provides various toolkits and services for the deployment of village fibre networks in order to safeguard that these networks meet industry requirements. As the deployment cost per access in rural areas can be as much as four times what it cost in urban areas, such development may not attract commercial players and rely on such collaborative approaches. Aside from any public funding, Sweden’s experience suggests that village networks require local initiatives and commitment as well as leadership through the development of local broadband plans and strategies. They also require co‑ordination with authorities to handle a variety of regulatory and legal issues, and demand competency on how to build and maintain broadband networks. The most decisive factor is that people in these areas of Sweden are prepared to use their resources and contribute with several thousand hours of work to make a village network a reality.

In the United Kingdom, Community Broadband Scotland is engaging with remote and rural communities in order to support residents to develop their own community-led broadband solutions. Examples of ongoing projects include those in Ewes Valley (Dumfries and Galloway), Tomintoul and Glenlivet (Moray), which are inland mountain communities located within the Moray area of the Cairngorm National Park. Another example of a larger project can be found in Canada and the small Alberta town of Olds with a population of 8 500, which has built its own fibre network through the town’s non‑profit economic development called O-net. The network is being deployed to all households in the town with a number of positive effects reported for the community.

Sources: Mölleryd, B. (2015[17]), “Development of high-speed networks and the role of municipal networks”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jrqdl7rvns3-en.; OECD (2016[11]), OECD Regional Outlook 2016: Productive Regions for Inclusive Societies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264260245-en.

Areas for further progress

Poor labour market skills matching continues to be a drag on the region’s economy

Strong linkages between the regional education system and the business community are a necessary condition for achieving a better match of skills supply with skills demand. Over the past five years, in Småland-Blekinge, those links have been strengthened. The better co‑ordination of HEIs and vocational education and training (VET) schools with the business community has resulted in the creation of new programmes, curriculum design and updating with, in some cases, local companies sitting on the board of educational institutions. In the different counties, educational institutions have thus made efforts to become more responsive to local labour market needs. In Blekinge, VET institutions have been co‑operating with the military to develop a new programme that would meet their long-term labour market need for airport technicians; whereas the Linnaeus University (LNU) of Kalmar and Kronoberg recently created an eHealth postgraduate programme, in response to the relocation of the National eHealth Agency from Stockholm to Kalmar County. Through its Information Engineering Centre, LNU is also working with ICT companies to develop more relevant education programmes. The concern of retaining existing businesses with a high-growth potential in the region is associated with the objective to achieve good employment outcomes.

The availability of skilled human capital is central to enabling the growth of any company’s products and operations. The lack thereof may prompt firms to relocate to neighbouring business hubs such as Stockholm or Malmö or even lead to their closure. It bears noting that there is also demand for skills in the public sector in several occupations, for example, qualified teachers, school managers, qualified social workers, city planners (architects, engineers), all kinds of nurses. The French CIFRE convention (Conventions Industrielles de Formation par la Recherche) is a best practice that may be replicable and adapted at the local level and which could effectively boost the hiring of young talent by local businesses. Fostering synergies between education and the labour market contributes not only to ensuring that businesses find individuals with the right skills to meet their need, but it should also be sought as part of a strategy to generate greater spillovers from university, research across a diverse set of economic activities in the region in order to support its knowledge-based transition. Knowledge spillovers, which are knowledge benefits that firms, researchers and other agents receive by being co-located, are typically measured by patent citations and the distance decay associated with citations in the same technology areas (i.e. after a particular distance, citations are significantly less likely, commonly found to be within a 150-200 km radius) (OECD, 2016[3]).