This chapter analyses education reforms adopted by Mexico from 2012 focused on strengthening the quality of the teaching profession and schools to enhance quality and equity in education provision. The chapter describes and reviews the teacher professional service (Servicio Profesional Docente) and the School at the Centre strategy (La Escuela al Centro) as the two main pillars to support better learning for all students in Mexican schools. It concludes with a set of insights on how these policies can best reach schools and have a positive impact on student learning.

Strong Foundations for Quality and Equity in Mexican Schools

Chapter 4. Supporting teachers and schools

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

Education policy and school systems need to adapt to the social and economic changes of a world continuously evolving. They need to make sure that all students are equipped with the skills, knowledge, and values to succeed in life and work regardless of their background. Recent technological changes, like digitalisation, represent both opportunities and challenges in preparing students in school and to be lifelong learners (Schleicher, 2016[1]).

Equipping students with these skills requires innovation and change in the traditional approaches towards teaching and learning. Mexico’s New Educational Model and curricular approach aim to focus on developing these new skills for all students (see Chapter 3). As teachers are among the main actors that shape the context for student learning, educational policy and practice needs that recognise the essential role that teachers play in transforming classrooms and support them in their endeavour (Schleicher, 2018[2]).

Effective leadership at the school and system levels and school support must be in place for teachers to be able to implement this vital shift in pedagogical approaches and encourage them to build a collective professional approach to improving student learning. Improving teaching practices in the classroom (and in general, of the teaching profession) also requires developing the school as a learning community that provides the right environment for teachers in their challenging tasks.

Recognising their importance, one of the main areas of focus of the recent education reforms in Mexico is improving the quality of the teaching profession. This chapter analyses how these reforms contribute to improving quality and equity in education through better teaching in schools across Mexico.

The chapter is divided into three sections. Following this introduction, the chapter describes the main elements of the School at the Centre strategy (La Escuela al Centro) and those related to the Teacher Professional Service (Servicio Profesional Docente). The second section discusses progress made in these areas, and analyses it in relation to research and international relevant practices. The chapter concludes with insights on how these reform strategies can be enhanced in terms of policy design and implementation to promote effective education quality and equity at the school level and in the classroom.

Policies targeting schools and teachers

This section describes recent changes to improve schools and the teaching profession in Mexico: the School at the Centre strategy (La Escuela al Centro) and the Teacher Professional Service (Servicio Profesional Docente, SPD).

Schools as learning communities: Placing schools at the centre

School organisation and leadership are key to support the development of a high-quality teaching profession. For school systems to flourish, they require focusing not only on individuals but on professional capital which encompasses three kinds of capital: “human capital (the talent of individuals); social capital (the collaborative power of the group); and decisional capital (the wisdom and expertise to make sound judgments about learners that are cultivated over many years)” (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2013[3]). This includes recognising teachers’ individual pedagogical skills and practice, and their continuous learning throughout their career as well as the articulated surroundings that promote collaboration and decision making, towards improving student learning in their schools and beyond.

As in most OECD countries, Mexico’s schools have a staff structure with different figures who share pedagogical and administrative responsibilities. Each school usually has:

One school leader, sometimes helped by a deputy director in lower secondary schools.

A number of teachers that vary depending on the number of students.

Additional staff in larger primary and lower secondary schools. This staff does not have a regular teaching load and used to be in charge of any type of support functions before the creation of the Teacher Professional Service (SPD) (Santiago et al., 2012[4]).

Mexico has taken on the challenge to transform its education system, recognising the important role of the school as an enabling institution for systemic change. The School at the Centre strategy (La Escuela al Centro) was created by the Secretariat of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP) to give coherence to Mexico’s 2013 reform priorities at the school level, and reorganise existing school support programmes accordingly. Its objective is to reduce the bureaucratic load for schools and to guarantee that they have the skills and resources to foster active participation and collaboration within the school community, always with the purpose to enhance educational outcomes (SEP, 2018[5]). The strategy covers six lines of intervention.

First, it aims to turn schools into learning communities with a less bureaucratic load for both school principals and supervisors. In this regard, the programme aims to:

Guarantee that each school has the basic staff required (one teacher for each group and one school leader) and provide larger primary and early childhood institutions with additional staff1 to reduce the administrative load of school leaders so they can focus more on their pedagogical leadership role.

Support the activities undertaken by supervisors. To make them more effective in their responsibility for co‑ordinating technical assistance for their schools, the programme seeks to develop their skills for pedagogical accompaniment and reduce the number of schools under each supervisor responsibility. It also assigns to them two Technical Pedagogical Advisors (Asesores Técnico Pedagógicos, ATPs) and one administrative assistant (apoyo de gestión), or three new posts in total.

Second, the programme aims to improve the provision of direct resources for the schools:

Schools will directly receive a budget according to the number of students it has and to their level of educational lag.

Resources are allocated through two programmes: the Education Reform Programme (Programa de la Reforma Educativa, PRE) and the Full-Time Schools programme (Escuelas de Tiempo Completo, ETC).

Schools can decide their expenditure based on their own priorities, with the community’s participation.

Third, the programme aims to reinforce support for the teaching staff in schools with the following initiatives:

Strengthening the School Technical Councils (Consejos Técnicos Escolares, CTE) by introducing monthly meetings focused on improving all students learning (with a special focus on students at risk) and enhancing teaching quality through peer learning and schools exchange sessions. Teachers and their principal collaborate to establish and monitor the school’s improvement route (Ruta de Mejora). The CTE follows up on academic and pedagogical issues, using monitoring indicators. For instance, the Early Alert System (Sistema de Alerta Temprana, SisAT) uses indicators such as attendance and reading comprehension (among others) to identify students at risk of lagging behind and dropping out. Each school can decide the day of the month and time for its CTE meeting, for more flexibility.

Strengthening supervisors´ pedagogical function and skills by giving them training based on peer exchange and learning, and specific tools for technical accompaniment as class observation and monitoring of student learning (more than 18 000 supervisors have participated in certification programmes designed specifically for the function). The strategy also aims to reinforce the Zone Technical Councils (Consejos Técnicos de Zona), where supervisors and school principals have regular meetings, into a place of collective learning.

Reengineering the pedagogical team that accompanies and supervises the school: the Technical Support Service to Schools (Servicio de Asistencia Técnica a la Escuela, SATE).

Providing physical and virtual spaces where teachers can share pedagogical resources and experiences.

Fourth, harmonic school environments are encouraged to:

Foster equity. Summer schools will be provided to offer cultural and sports activities as well as courses for strengthening academic skills.

Work on developing students’ socioemotional skills at school and home to build a harmonic environment.

Fifth, the School at the Centre suggests initiatives to increase the time allocated to learning activities, including:

The school community, exercising its own autonomy, will make its own decisions about the organisation of time in the school (following the official calendar produced by the SEP) to offer the maximum learning time to students according to the context of school and student needs (more information in Chapter 3).

The Full-Time Schooling programme (Programa Escuela de Tiempo Completo, PETC) will be expanded to more schools (more information on the programme in Chapter 2).

Sixth, it is essential to promote community engagement. Thus, the programme promotes:

A more prominent role for the School Social Participatory Councils (Consejos Escolares de Participación Social en la Educación) which aim to facilitate co‑operation among all those who are part of the school community.

The representation and participation of parents, teachers, principal and other school stakeholders in the councils, to secure accountability and transparency (SEP, 2018[5]).

Box 4.1. The Technical Support Service to Schools (SATE)

The Technical Support Service to Schools (Servicio de Asistencia Técnica a la Escuela, SATE) has been designed to support teachers and schools in Mexico. The main goals are to:

1. Improve teaching practices, based both on individual and collective experiences and knowledge, as well as on the learning needs of the students, to encourage thoughtful decision making in the work undertaken in the classroom and the school, within a framework of equity, inclusion and recognition of diversity.

2. Support the identification of the needs of continuous training of the teaching and management staff to be addressed by the educational authorities.

3. Strengthen the functioning and organisation of schools, through the use and promotion of the school improvement plan, school leadership, CTE and the collaborative work in the school community, within a framework of management autonomy.

4. Support teachers (as a group) in the practice of internal evaluation, making it a permanent and formative practice that strengthens and contributes to a well-informed decision-making process that improves student learning.

5. Support teachers (as a group) in the interpretation and use of external evaluations, taking into account their results as inputs for the analysis of the educational work that is carried out with students in the schools and the definition of actions to improve processes and learning outcomes.

6. Deliver counselling and technical pedagogical support for schools in Basic Education aiming at the improvement of student learning, teaching and school leadership practices, and school organisation and operation.

The SEP draws up guidelines to organise the SATE, and state education authorities operate the service, which is co‑ordinated by zone supervisors and implemented by ATPs. The number of schools that each SATE covers varies according to the size of the supervision zone. Each SATE is composed of:

One school supervisor.

Two technical pedagogic advisors (ATPs) appointed by promotion.

One ATP appointed by recognition (reconocimiento), in the case of pre-school and primary education. Three ATPs in the case of secondary education.

One ATP with technical operations functions supporting other schools.

Following the General Law of the Teacher Professional Service (Ley General del Servicio Profesional Docente, LGSPD), supervisors and ATPs are selected through the promotion mechanism (promoción). They must comply with the professional standards (perfil) and pass the examination for promotion (concurso de oposición para la promoción).

Source: SEP (2018[5]), La Escuela al Centro, https://basica.sep.gob.mx/escuela_al_centro/ (accessed on 22 August 2018).

The model of La Escuela al Centro reflects Mexico’s intention of building change and innovation capacity within schools and local governments as a key enabler to transform schools, supporting the development of a stronger teaching workforce and improving the education system (SEP, 2018[5]). Principals, teachers and other pedagogical support staff such as Mexico’s new SATE (Servicio de Asistencia Técnica a la Escuela) are considered active agents of this transformation with the schools (Box 4.1).

The Teacher Professional Service

Developing quality teachers is essential for improving the quality of learning in any country. In order to support its teachers, student learning, and quality and equity in education, Mexico has been working on strengthening teaching and school leadership through comprehensive reforms in recent years (OECD, 2015[6]). OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) data shows that before 2013, almost a quarter (24%) of teachers in Mexico reported not feeling prepared to perform their work (the third largest share of teachers across countries), compared with the TALIS 2013 average of 7%. Previous to the reform, the educational professions lacked transparency in career advancement opportunities; professional profiles were not established and professional performance was seldom appraised other than in voluntary career advancement schemes; and teachers were in need of more support in their career. An OECD report concluded the following about the teaching profession (OECD, 2012[7]):

Selection process: Before 2008, only 13 states used licensing mechanisms when selecting teachers; the remaining 19 states allocated posts mainly upon the acquisition of a teacher’s diploma. The mechanisms for the selection of teachers were not transparent and sometimes perceived as unequal, corrupt or highly politicised. A National Teaching Post Contest (Concurso Nacional para el Otorgamiento de Plazas Docentes) started in 2008 as the first step in a process to enhance teacher quality by making teacher selection more competitive, merit-based and transparent. By 2012, the OECD report already pointed out some clear pending issues. First, all teaching posts were still not open to competition and the system for allocating teachers was only based on teacher choice, with no opportunity for schools either to express their needs or to get staff that responded to them. Particularly, becoming a school leader did not require any specific skills and leadership positions were not subject to any selection process other than being an experienced teacher. It was also of concern to observe that in 2008 and 2009 successively, a large number of candidates scored low on the National Teaching Post Contest and that without improving their knowledge and skills, newly qualified teachers who scored repeatedly lower than the minimum score were still potentially eligible for a permanent post.

Professional development: The programme of professional development (National Training Catalogue) was dispersed across a range of different providers and organisations. What is more, options for developing professional skills and knowledge were not diversified enough to respond to schools’ or teachers’ needs. School-based training opportunities existed but were still scarce.

Career advancement and appraisal mechanisms: Before 2013, some teacher career guidelines (Carrera Magisterial, 1993) determined the conditions under which outstanding teachers, school leaders and pedagogical support staff could be acknowledged without having to change position. This promotion mechanism was voluntary and offered career and salary advancement opportunities based on individual teacher performance. However, there was no compulsory, standard-based appraisal mechanism in place to guarantee the quality of pedagogical practices in schools: once in position, teachers and other education professionals could stay with no further appraisal. Furthermore, there were no clear standards on what it is to be a “good” teacher or an effective school leader.

In 2013, the General Law of the Teacher Professional Service (Ley General del Servicio Profesional Docente, LGSPD, 2013) established a framework for education professionals: teachers, school leaders (or principals) and vice-principals, co‑ordinators, supervisors, inspectors and technical pedagogical advisors (asesores técnico-pedagógicos, ATP). The Teacher Professional Service (SPD), which enacts the LGSPD, sets out the bases for selection, induction, promotion, incentives and tenure possibilities, as well as for stimulating continuous professional training for educational staff.2 Its main purpose is to guarantee the adequacy of the knowledge and capacities of teaching staff, school leaders and supervisors in basic and upper secondary education (LGSPD, 2013). Two processes are at the core of the SPD: professional development and appraisal, both formative and summative.

Specifically, the objectives of the SPD are to:

Regulate the teaching activity in pre-school, primary and secondary education.

Establish the profiles, parameters and indicators for the teacher professional service.

Regulate the rights and obligations derived from the professional development service.

Ensure transparency and accountability in the professional development service.

The Teacher Professional Service aims to bring into a coherent whole several elements of the teaching profession, also rewarding good performance and improvement and providing incentives for both schools and individuals (OECD, 2018[8]). In this sense, the SPD:

1. Defines the profiles, parameters and indicators for teachers (Perfil, Parámetros e Indicadores para Docentes y Técnicos Docentes), for the leadership roles (principals, vice-principals, co‑ordinators) and for supervisors, and pedagogical profiles for ATPs (Perfil, Parámetros e Indicadores para Personal con Funciones de Dirección, de Supervisión y de Asesoría Técnica Pedagógica).

2. Establishes the framework for a career perspective for the teaching profession with clear criteria for entry, permanence, promotion and recognition in transparent conditions:

Entry and selection process: the entry new process aims to incorporate suitable candidates to the educational workforce through a clear selection process. It consists in passing the three steps of the entrance examination (Concurso de Oposición para el Ingreso); going through probation phases that include training and support, then mentoring for two years; being initially appointed for six months (nombramiento) and then reaching final appointment (nombramiento definitivo). After the first year, a diagnostic appraisal (evaluación diagnóstica) takes place, and mentoring and support are aligned to help new teachers improve their practice. A second appraisal focused on performance (evaluación del desempeño docente) is compulsory during the second year, which determines whether the candidate can continue his or her career as a teacher. As of 2016, candidates can come from higher education institutions other than the teachers’ colleges (normales) which may help to diversify and improve the offer of possible future teachers, although care should be taken to ensure that candidates from all qualifying institutions acquire the necessary set of skills and knowledge required to enter the profession.

Permanence in the profession: teacher performance appraisal for in-service teachers (evaluación de desempeño de los docentes en servicio) defines the conditions under which in-service teachers can retain their position in front of the classroom. The performance appraisal model has evolved towards three components: a report on the fulfilment of professional responsibilities; a teaching project3 that includes pedagogical planning, intervention and reflection on practice (60%); and a sit-in exam on pedagogical knowledge, curriculum and disciplines, and legal and administrative knowledge related to the profession (40%).

Promotion and trajectory in the profession (promoción en el servico y trayectoria profesional): it establishes the trajectory to become a school leader, ATP or supervisor in basic education, and to become a school leader or supervisor in secondary education (educación media superior, EMS). These trajectories include two years of induction. Promotion is undertaken following annual concursos. As part of the promotion mechanisms, there is also a system of rewards within the same position (programa de promoción en la función, LGSDP, Art. 4, Fraction 8) or voluntary lateral moves (to develop other competencies) aiming to reward those education staff who stood out in both their performance appraisal (evaluación del desempeño) and in an additional appraisal for the promotion process (evaluación adicional).

3. Re-designs mentoring (tutoría) for new teachers during their first two years of service. There are three types of mentoring in order to ensure that it reaches all educational contexts: mentoring in situ, online mentoring and rural mentoring. Mentoring aims to:

Strengthen the competencies of the teaching and technical teaching staff entering the profession, and support their insertion in the educational workforce and their permanence in the professional teaching service.

Contribute to the improvement of teachers’ professional practice.

4. Establishes the SATE as the core support for in-service teachers and educational staff at the school level (see Box 4.1).

5. Re-designs the framework for the professionalisation of the teaching career (Marco de la Profesionalizacion de la Docencia) within an annual National Continuous Training Strategy (Sistema Nacional de Formación Continua). The strategy considers three main lines:

Training to elaborate the educational projects required for the evaluation of promotion and permanence of the professional teaching service.

Training on the service provided for education staff who participate in the mechanisms of evaluation, tutoring and the SATE.

Continuous training in the priority themes of the new educational model and transversal themes that are relevant for basic education.

The LGSPD establishes that the SEP is responsible for producing the general guidelines of the SPD. The SEP also collaborates with the state education authorities and with the National Institute for Education Evaluation (Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, INEE) to elaborate on and supervise the professional appraisal processes. The new National Co‑ordination of the Teacher Professional Service (Coordinación Nacional del Servicio Profesional Docente, CNSPD) generates the policies, programmes and actions necessary to guarantee continuous development, training and capacity building to education professionals. The CNSPD has a deconcentrated organisation, with subnational branches at the state level. It is in charge of defining the SPD’s profiles, parameters and indicators (perfiles, parámetros e indicadores, PPI) and the steps, aspects, methods and instruments of professional appraisal (etapas, aspectos, métodos y instrumentos, EAMI). The CNSPD also designs and carries out the appraisals; qualifies and publishes their results; and operates the SATE and the mentorship mechanisms.

State education authorities (Autoridades Educativas Locales, AEL) are mainly in charge of providing professional development programmes that are “free, adequate, relevant and congruent” (LGSPD, Article 8), and of participating in the design and implementation of professional appraisal processes. The INEE produces guidelines with quality criteria for the professional development offered by education authorities; it validates the appraisal mechanisms and oversees the processes when appraising teachers.

Assessment

Teachers are key for improving student learning, and therefore essential to achieving the goals of quality and equity in education expressed in Mexico’s constitution. Teachers do not work in a vacuum, however: building a quality teaching workforce requires efforts on numerous levels. This section offers insights from international evidence and practice on three types of policies for ensuring a high‑quality teaching profession: school mechanisms that can support and foster a quality teaching profession, effective leadership that can create an environment in which quality teaching can take place and teacher policies aimed at improving the quality of the workforce (OECD, 2014[9]).

Supporting schools as learning communities

Ensuring a full occupational structure in each school

The first requirement that must be complied with if schools are to provide high-quality education is to ensure that they have adequate staff for the different pedagogical and administrative tasks. The SEP is co‑ordinating with other education authorities to revise and enhance the occupational structures (estructuras ocupacionales) of schools in basic education. The initiative consists in identifying an occupational structure of reference, which defines the basic number of teaching and administrative staff necessary for each type of educational service. This basic structure could then be adapted by education authorities depending on the context in which they provide the various forms of education they are responsible for. As of September 2018, the state education authorities were in the process of presenting their suggestions for the structure of reference to the national authorities. Once all information is collected, the plan is for relevant authorities to formalise the structure of reference and to determine the occupational structures for each state based on this referential, taking into account each entity’s particular needs and resources.

Promoting collaborative professional practice among teachers and across schools

Mexico is in the process of strengthening professional collaboration in its schools. In order to place students at the centre and help improve the teaching profession, schools need to collaborate more systematically; schools’ members need to be open to change, open to the community and to the world around them, capable of introducing innovations with agility; and authorities need to support schools to create places where everyone is continuously learning. Perhaps most importantly, teachers need to be open and willing to engage with their colleagues, their administration and their students (Schleicher, 2018[2]).

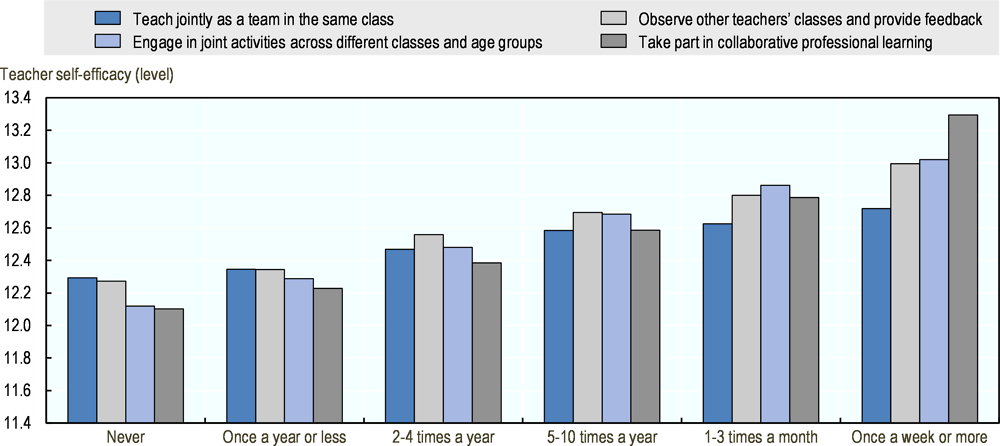

International evidence suggests that although both human capital and social capital in schools are important, social capital can be more influential as a lead school improvement strategy (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2013[3]). This points to the importance of focusing on facilitating collaborative working and learning environments to promote teacher professionalisation and school improvement. Fostering collaborative practices in schools, whether through collaborative professional development, systems of peer feedback or collaborative teaching, are highly beneficial to teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Analyses show that teachers who report engaging more in collaborative activities also tend to show higher levels of job satisfaction as well as self-efficacy (Figure 4.1). Professional teaching collaboration include teaching jointly in the same class, observing and providing feedback on other teachers’ classes, engaging in joint activities across different classes and age groups and taking part in collaborative professional learning. Further, TALIS analysis shows that collaborative learning is highly associated with effective practice in the classroom (Opfer, 2016[10]; Barrera-Pedemonte, 2016[11]). Formal collaborative learning flourishes in schools with suitable school mechanisms and supportive leadership. It generally entails teachers meeting regularly to share responsibility for their students’ success at school (Chong and Kong, 2012[12]).

Mexico has undertaken its own strategy to build the model of schools as learning communities at the centre of the education system, known as La Escuela al Centro. The strategy can form the basis on which to build more robust and frequent teacher collaboration and to establish a learning culture that includes professional learning communities, peer feedback and professional learning plans. La Escuela al Centro strategy and the structure of the SPD signal a shift for Mexico towards more systematic and formal professional collaboration. The School Technical Councils (Consejo Técnico Escolar, CTE) provide a valuable space for exchanges on professional practice among the pedagogical team (i.e. the school leader, the teachers and, potentially, support agents such as the ATPs).

Figure 4.1. Teachers’ self-efficacy and professional collaboration, 2013

Note: To assess teachers’ self-efficacy, TALIS 2013 asked teachers to indicate to what extent they can do certain activities (on a four-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “a lot”), by responding to a number of statements about three indices: their efficacy in classroom management, in instruction and in student engagement. The index of teacher self-efficacy is summarised across these three indices. A higher index value indicates a higher level of self-efficacy.

Source: OECD (2014[9]), TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en.

Within the new framework, schools are strongly encouraged to hold at least one session per month with their CTE. Furthermore, a new strategy entitled Learning between Schools (aprendizaje entre escuelas) was suggested for the CTEs: since 2016, teachers across 3 or 4 schools have met twice during the school year to exchange on their practices, experiences, materials and pedagogical strategies. In 2017, teachers shared a class (live or recorded) to be commented by their peers. The SEP reports that close to 90% of schools took part in this strategy (information communicated by the SEP directly to the OECD team). The establishment of mentorship programmes also aims to stir collaboration between experienced teachers and teachers initiating their careers. The SATE, to be carried out by supervisors and technical pedagogical advisors (Asesores Técnico-pedagógicos, ATP) aims to stimulate exchanges about pedagogical practice between schools’ teaching staff and the supervision level.

Historically, Mexico’s school educators have engaged in more informal collaboration (OECD, 2010[13]). According to the exchanges of the OECD team visiting Mexico, one of the unexpected effects of the teachers’ appraisal was the emerging of informal collaboration practices among teachers, mainly with the purpose of helping each other to prepare for their evaluations. The team also observed that teachers exchanged practices on individual blogs following the publication of the new curriculum.

Other efforts to systematise professional collaboration exist in Mexico but remain sparse. Some states such as Puebla promoted supervisor councils and teacher councils which can be found working closely with the SEP, giving advice on how to better implement educational initiatives. The cases of learning communities (comunidades de aprendizaje) encouraged by the National Council for Educational Development (Consejo Nacional de Fomento Educativo, CONAFE), could be further studied and fostered beyond rural schools as a model of collaboration.

However, peer collaboration, time scheduled for collaboration in schools and learning communities are not yet extensively present, partly for lack of time and resources and partly due to the individualistic view of the teaching profession that still prevails. It is not only a matter of establishing collaborative spaces by norm. A culture of collaboration and a vision of the teaching profession as intrinsically tied to the school and learning communities has to be effectively supported and developed.

Collaborative learning tends to be active and interactive and often involves participation in a professional learning community (PLC) or other practices. This enables to engage teachers socially, giving them opportunities to share ideas and seek solutions to problems together, to learn with and from one another (Guskey, 1995[14]; Lieberman and Pointer Mace, 2008[15]). Many countries have incorporated PLCs or networks as part of their professional learning programmes, which can be implemented at a school, district, regional, national or even at an international level. PLCs tend to be most successful when they are guided by a shared vision and implemented in a context of trust, accountability and willingness/ability to take risks (Hunzicker, 2011[16]). This last point is a key factor in the success of peer feedback, as an important part of collaborative professional development relies on teachers sharing their practice openly with colleagues and on their willingness to provide and receive critical and constructive feedback (Hatch et al., 2005[17]).

A number of Asian countries incorporate this as everyday practice in their school, with more experienced teachers sharing their knowledge and skills with less experienced peers (see Box 4.2). For instance, in Japan, there has been a long tradition of collaborative peer learning through “lesson study” throughout teachers’ careers. Because they do not want to let the group down, teachers work hard to develop high-quality lesson plans, to teach them well and to provide sound and useful critiques when it is their colleagues’ turn to demonstrate their lesson plans to them.

Successful education systems like Finland, Japan, Korea and Singapore devote considerable time to school level activities related to instructional improvement, including for collaborative learning. There should be a time in a teacher’s day designated for collaboration with peers, discussing instructional practice, group preparation and professional development (Darling-Hammond and Rothman, 2011[18]; Darling-Hammond, 2010[19]). In Japan, 40% of teachers’ working time is devoted to these kinds of activities. Developing professional development at the school level is particularly important in Mexico because many schools in rural areas are quite isolated and national capacity to help meet their teachers’ needs is quite limited.

Effective leadership and management

Another important aspect of the reform in Mexico has been the development and consolidation of leadership capacity at the school level. Many countries have seen a shift from bureaucratic school systems to school systems in which schools themselves have more control over resource uses, instruction, curriculum and work planning. This encourages school leaders and teachers to work together to identify good practices, adapt or create them according to their students’ needs and build a learning community to support each other in improving the quality of their work.

Box 4.2. Collaboration and peer learning in Asian systems

Lesson study in Japan

Throughout their career, Japanese teachers are required to perfect their teaching methods through interaction with other teachers. Experienced teachers assume responsibility for advising and guiding their young colleagues. Headteachers (school leaders) organise meetings to discuss teaching techniques. Meetings at each school are supplemented by informal district-wide study groups. Teachers work together to design lesson plans. After they finish a plan, one teacher from the group teaches the lesson to her students while the other teachers look on. Afterwards, the group meets again to evaluate the teachers’ performance and to make suggestions for improvement. Teachers from other schools are invited to visit the school and observe the lessons being taught. The visitors rate the lessons and the teacher with the best one is declared the winner.

Demonstrating lessons and masterclasses in Shanghai (China) and Singapore

The concept of “masterclasses” or “demonstration lessons” has become more widely used in Asian contexts, including in Shanghai and Singapore. In this model, an accomplished or very experienced teacher gives lessons for multiple teachers (either within the same school or across multiple schools within the system) to observe. In Shanghai, master teachers are drawn from the top 1% of teachers in their subject field. They typically provide masterclasses at the district level three times per term.

A variation of this model, the “cascading model of teacher mentoring”, is also used in these systems to develop teacher capacity in a subject field across the system. Master teachers essentially mentor the next level of senior teachers using the process above, who in turn mentor other teachers in their own school.

Finally, in Singapore, the Outstanding Educator in Residence (OEIR) programme, organised by the Academy of Singapore Teachers, takes the masterclasses one step further (and more global) by inviting outstanding overseas teachers to conduct masterclasses.

Sources: Jensen, B. et al. (2016[20]), Beyond PD: Teacher Professional Learning in High-Performing Systems, http://www.ncee.org/cieb (accessed on 17 September 2018); Stevenson and Stigler, 1992, as cited in OECD (2010[13]), Improving Schools: Strategies for Action in Mexico, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264087040-en.

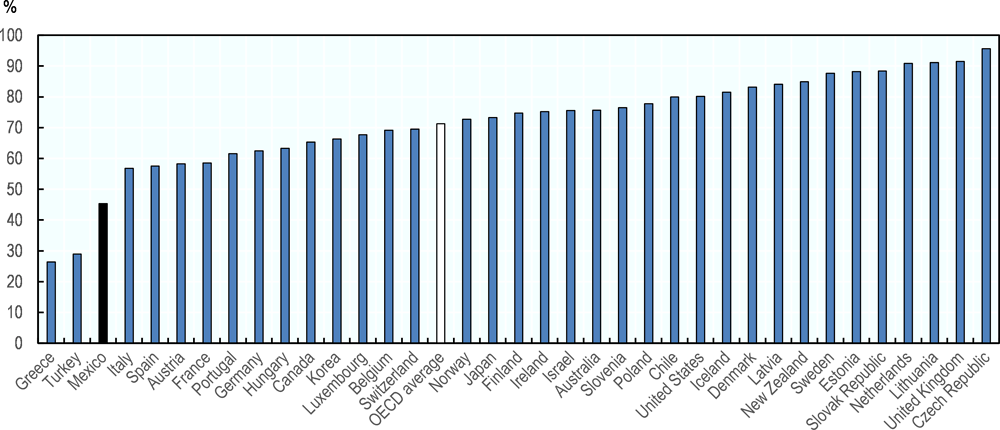

Developing capacity at the school level

Historically, schools have had very little autonomy in Mexico: in 2015, Mexico scored the third lowest index of school autonomy among OECD countries, which means that school personnel had responsibilities for less than half the tasks related to resource allocation and decisions about curriculum and instructional assessment (OECD, 2016[21]). Figure 4.2 shows the index of school autonomy across OECD countries in 2015. As noted in an OECD review carried out in 2010, the organisation and structure of education in Mexico makes it difficult for the system to promote large-scale school autonomy (OECD, 2010[13]). These challenges must be acknowledged and this report does not suggest schools in Mexico should be left to operate by themselves. By school autonomy we refer to the capacity for schools to assume a considerable share of responsibility in specific areas of decision making, by comparison with a situation where authorities at higher levels make all decisions. This engagement of school staff and local stakeholders in decision making in areas that are related to local and school needs is increasingly necessary to the success of education in 21st century education systems (Viennet and Pont, 2017[22]). There is evidence that some autonomy in curricular matters has a positive impact on students’ performance according to PISA results (see the chapter on the curriculum in this report). However, benefits are usually conditional on having effective accountability systems in place and high levels of capacity of school leaders and teachers (Hanushek, Link and Woessmann, 2013[23]). It is therefore crucial that education authorities help school communities build their capacity to make decisions to enhance student learning and improve education, including school leaders.

Figure 4.2. Index of school autonomy across OECD countries, PISA 2015

Note: The index of school autonomy is the percentage of tasks for which the principal, teachers or school governing board have considerable responsibility, including allocating resources to schools and responsibility for the curriculum and instructional assessment within the school. Results are based on school principals' reports.

Source: OECD (2016[21]), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

The School at the Centre strategy aims both to reinforce schools’ capacity for autonomy and to reduce the administrative load on system leaders (school leaders and supervisors) to allow them to exert more pedagogical leadership. This effort toward greater autonomy at the school level in some areas is in line with policies adopted or practices in some countries. Examples include Ireland, Norway, the Netherlands, Chile or the United States to different degrees (OECD, 2016[21]).

The School at the Centre implies an effort by education authorities to provide resources and develop capacities and to help grow a culture of autonomy, which can help schools and their leaders to fulfil their tasks. Two main programmes allocate additional resources to strengthen schools: the Education Reform Programme (Programa de la Reforma Educativa, PRE) and the Full-Time Schooling programme (Escuelas de Tiempo Completo). After financing infrastructure investment, the PRE shifted in 2017 to focus resources on increasing schools’ resource autonomy (see Chapter 2 for more details). These two programmes aim to provide 75 000 schools with a specific budget calculated according to the schools’ attendance. This first step is encouraging and will require close monitoring and follow-up with schools in order to make sure school communities manage and spend these extra resources in ways that enhance the quality of school processes: in the end, the ultimate goal of these investments is to improve student learning.

In addition, granting direct funds to schools requires key stakeholders to develop their skills and responsibilities in financial management of school investments. These stakeholders include: school leaders, teachers and CTEs; the supervision team (supervision escolar); participants in the Social Participation Councils (Consejos Escolares de Participación Social en la Educación, CEPSE) such as parent representatives and community spokespersons; and state education authorities (OECD, 2017[24]). To this effect, the School at the Centre initiative is closely linked with the strategies for continuous professional development of education staff (see the section on system leaders and support actors) and with programmes such as the SATE to strengthen advice and support at the school level.

School and system leaders

School leaders, supervisors and ATPs are essential for improving the quality of teaching and learning environments in schools. School leaders are the glue, enhancers and champions of each learning community: they play a key role in improving school outcomes by influencing the motivations and capacities of teachers, as well as the environment and climate within which they work. Effective school leadership is essential to improve the efficiency, quality and equity in schooling (Pont, Nusche and Moorman, 2008[25]).

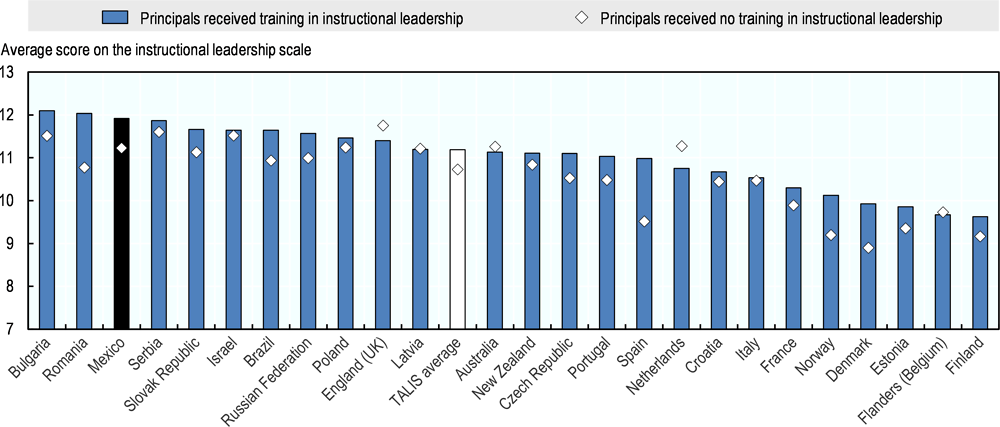

The Professional Teacher Service (2013) (Servicio Profesional Docente) aims to professionalise school leaders by introducing a selection and recruitment process, as well as an induction process during the first two years of practice (INEE, 2015[26]). Public selection processes (concursos) are now organised, with candidates expected to have a minimum of two years’ experience before being definitively appointed. These processes are based on specific profiles determined jointly by the INEE and national and state authorities. School leaders will be confirmed in their post only after positive appraisal. Upper secondary principals have the option to renew their appointment or to return to the status of teacher if they are not reconfirmed in their post. Before the SPD, over half of school leaders were in fact teachers acting as school principals, without any formalised role (OECD, 2018[8]). The School at the Centre strategy has brought together several efforts to develop principals’ skills and to give them tools to provide pedagogical advice to their teachers. Since 2014‑15, the SEP started a controlled experiment with the World Bank. In the treatment schools, principals receive special training in leadership, class observation and student learning monitoring tools, as well as certification on school management; the intervention also considers family training in parenting skills. Principal management skills and student achievement are the outcome variables. Final results of the impact evaluation will be presented in the end of 2018. As TALIS data have shown (see Figure 4.2), school leaders who have received training in pedagogical leadership (practices school leaders use in relation to the improvement of teaching and learning) are more likely to engage in these practices in their school (OECD, 2016[27]). In turn, pedagogical leadership is a strong predictor of how teachers collaborate and engage in a reflective dialogue about their practice.

Figure 4.3. Principals’ training in instructional leadership, lower secondary education, 2013

Source: OECD (2016[27]), School Leadership for Learning: Insights from TALIS 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264258341-en.

The School at the Centre strategy also aims to lighten the administrative load that falls onto school leaders, so they can devote more time to exercise pedagogical leadership in their schools and offer guidance to their teachers. In a previous review, the OECD noted that school leaders still tended to see themselves as administrators rather than pedagogical leaders (OECD, 2010[13]).

The new policies aim to clarify the responsibilities of key school figures (especially the teacher, school leader, supervisor and technical pedagogical advisor) and to strengthen the role of school supervision as a primary source of advice and support to school leaders. In this regard, the SATE (see Box 4.1) is a vital support for school leaders and their schools, since the service is expected to bring both administrative and pedagogical advice. A school improvement service like the SATE holds great potential, given its central role in the support to teachers and system leaders (i.e. principals and supervisors).

School leaders, through the work they do and the relationships they establish with teachers, staff and students, help to create a positive, supportive climate for learning. In Chile, got example, the main task of school principals has evolved from administrator to the implementation and management of the school educational project. This implies that all school principals should: develop, monitor and evaluate the goals and objectives of the school, the study plans and curricula and strategies for their implementation; organise and guide the technical pedagogical work and professional development of teachers; and ensure that parents and guardians receive regular information on the operation of the school and the progress of their children. (Box 4.3).

In Ontario, Canada, a leadership organisation has been supporting school leaders in part by providing a research-based leadership framework for pedagogical leadership (see Box 4.4) and this is an example Mexico can look at to reflect on and enrich its own school leadership policies.

Box 4.3. Strengthening the role of the principal by developing school leadership standards in Chile

In a shift from the traditionally administrative and managerial role of school leaders, Chile developed standards to emphasise school leaders’ pedagogical role. Different sets of school leadership standards provide guidance for school leaders about the role they should fulfil. The original Good School Leadership Framework (Marco para la Buena Dirección), published by the Ministry of Education in 2005, was updated with a new set of standards in 2015 (Marco para la Buena Dirección y el Liderazgo Escolar).

These school leadership standards have been designed to support school leaders in their self-reflection, self-evaluation and professional development; to establish a common language around school leadership that facilitates reflection of school leadership within the school community; to guide the initial preparation and professional development of school leaders; to provide a reference for the recruitment and evaluation of school leaders; to facilitate the identification of effective school leaders and to spread good practices; and to promote shared expectations about school leadership and provide a reference for professional learning.

Overall, school leadership standards are not prescriptive and represent a common reference that is adapted to local contexts. To reflect the contextual nature of school leadership, the standards distinguish conceptually between “practices” and “competencies” that form the basis of successful school leadership. On one hand, practices entail five dimensions: i) constructing and implementing a shared strategic vision; ii) developing professional competencies; iii) leading processes of teaching and learning; iv) managing the school climate and the participation of the school community; and v) developing and managing the school. On the other hand, personal resources comprise three areas: i) ethical values; ii) behavioural and technical competencies; and iii) professional knowledge.

Source: Santiago, P. et al. (2017[28]), OECD Reviews of School Resources: Chile 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264285637-en.

Another key leadership figure at school and subnational levels is the school supervisor. Each state organises its system of supervision of schools, structured according to geographical areas at two levels: sectors (sectores) and zones (zonas). Sectors consist of a number of zones and each zone comprises a number of schools. Supervisors take responsibility for each zone (and the respective schools). Supervisors function as the direct link between schools and education authorities (Santiago et al., 2012[4]). There are 14 197 school supervisors (supervisores escolares, which can also be translated as “school inspectors”) in Mexico, who are responsible for attending and supervising between 6 and 50 schools each (as of 2018, data provided by the SEP).

Supervisors are in charge of guaranteeing that their schools provide quality education to all the students. Supervisors’ main function is to provide advice and support according to the needs expressed by the school leaders and teachers in their school zone. They function as the institutional link between the various levels of educational governance. The figure of the supervisor is expected both to provide advice and support, and to promote participative management in schools. Supervisors are also expected to support bottom-up initiatives from teacher and school leader groups, especially when these initiatives are aimed at making sure that all students can reach at least the expected learning outcomes. A previous OECD study found that supervisors tended to focus on their role as administrative inspectors while providing rudimentary pedagogical advice (Santiago et al., 2012[4]).

Because of supervisors’ strategic position, they are in a unique place to help schools improve their practice. Efforts have been made to strengthen their role, especially in pedagogical matters. In 2014, the SEP committed to:

Significantly reduce the administrative load on school supervisors and strengthen their functions of pedagogical advice and orientation.

Establish support teams for school supervision to continuously develop and improve schools.

Since then, the SEP has implemented a series of actions to strengthen supervisors’ professional skill set and to facilitate their access to schools and classrooms so they can contribute more directly to improving learning. One flagship initiative is the creation of a certification programme specifically designed for supervisors. Examples of training courses for supervisors include class observation methods and basic elements of student assessment, which is expected to strengthen supervisors’ expertise in pedagogical practices and issues in the classroom. As of September 2018, 12 414 supervisors had been accredited, a completion rate of 78% (data provided by the SEP). When interviewed, SEP officials acknowledged that there was still room for progress to strengthen school supervision.

Box 4.4. Developing education leadership in Ontario, Canada

The Institute for Educational Leadership (IEL) in Ontario is a virtual organisation made up of a partnership of representatives from Ontario’s principals’ and district officers’ associations, councils of school district directors and the Ministry of Education. Its purpose is “to further develop educational leadership so as to improve the level of student achievement in Ontario’s publicly funded education system. One of IEL’s five practices and competencies within its research-based leadership framework for school principals and deputy principals is “leading the instructional program”, described as: “The principal sets high expectations for learning outcomes and monitors and evaluates the effectiveness of instruction. The principal manages the school organisation effectively so that everyone can focus on teaching and learning”. Among a number of practices outlined to achieve this are: ensuring a consistent and continuous school-wide focus on student achievement; using data to monitor progress; and developing professional learning communities in collaborative cultures. Associated skills include that the school principal is able to access, analyse and interpret data, and initiate and support an enquiry-based approach to improvement in teaching and learning. Related knowledge includes knowledge of tools for data collection and analysis, school self-evaluation, strategies for developing effective teachers and project management for planning and implementing change.

Source: Ontario Institute for Educational Leadership (2018[29]), Ontario Leadership Framework, http://www.education‑leadership‑ontario.ca/en/resources/ontario‑leadership‑framework‑olf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

Efforts were made as well to reform and formalise the role of the support figures for school supervisors. Historically, school supervision units (supervisiones escolares) had a small number of staff aimed to provide administrative and pedagogical expertise (technical administrative advisors – asesores técnico-administrativo, ATA; and technical pedagogical advisors – asesores técnico-pedagógico, ATP).

The technical pedagogical advisor (asesor técnico pedagógico, ATP) became a central figure to guarantee that the reforms contribute to school and teacher improvement in Mexico. “ATP” was used to refer to any individual with teacher status who was not in front of a class, did not have a legal status and was given no specific professional guidelines (OECD, 2010[13]). Within the new SPD framework, the ATP role has been defined as an education professional whose main function is to provide expert pedagogical advice to teachers, school leaders and supervisors. It is thus a figure of support, central to the School at the Centre programme and, more generally, to the initiatives to improve the quality of teaching and learning. ATPs will also be subject to selection and recruitment processes and can participate in the different promotion mechanisms (OECD, 2018[8]).

ATPs play a key role in the SATE and are partners of school supervisors. ATPs participate in planning, developing and following up on SATE activities in their zone; designing the service’s support strategy, giving priority to the schools most in need; visiting schools periodically to bring advice and support to teachers and school leaders; observing the work done with students in the classes; and creating networks and learning communities between education professionals and between schools in their zone (SEP, 2017[30]). The SATE also counts on administrative support, provided by an experienced school leader to his/her peers in the supervision’s zone.

Implementing a service like the SATE can take time, especially because education authorities needed to fill 33 000 ATP positions for the SATE to be operational in every supervision area. At the time this report was written, however, only a third of these were allocated (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team).

Other countries have set up similar advice services to support schools and their leaders with qualified professionals in both pedagogical and administrative matters. For instance, challenge advisors have been introduced in regional improvement consortia in Wales to provide practical guidance and support to schools (OECD, 2018[31]).

Developing the teaching profession

Efforts to strengthen teacher professionalism

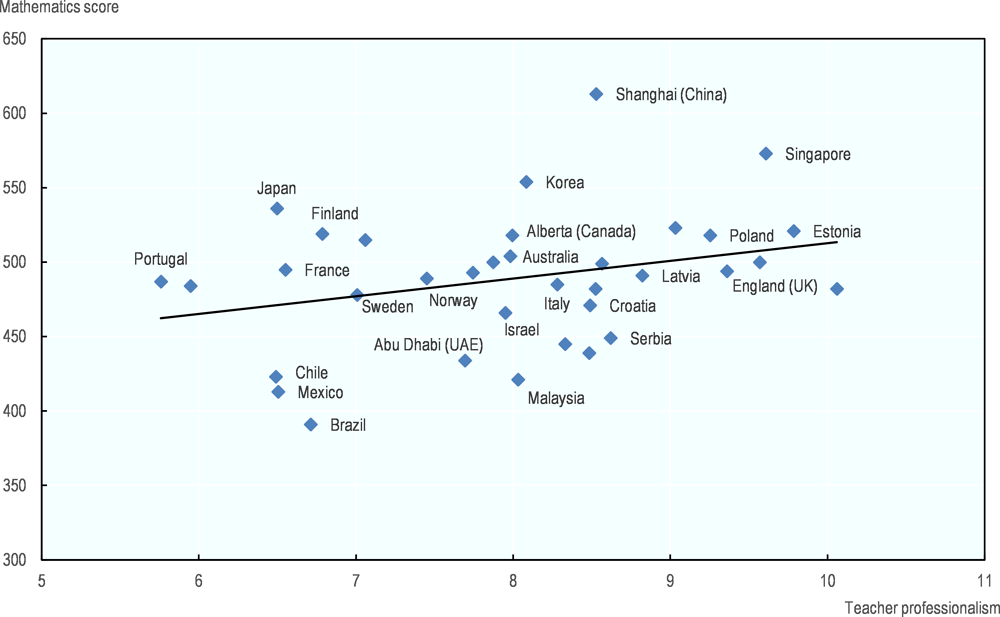

Teachers should have a deep understanding of what they teach and of their students. This requires specific curricular knowledge as well as knowledge about pedagogy and practice that enables teachers to create effective learning environments and foster adequate learning outcomes. By seeking to professionalise the educational workforce with a career perspective in Mexico, the SPD aligns with evidence that highlights how career progression opportunities can enhance teacher quality. This includes the preparation, selection, recruitment, evaluation, professional training, support and incentives for teachers to develop as professionals (OECD, 2005[32]). The SPD formalises the progression paths for the various professions available to the education workforce, signalling educational careers as coherent professional careers. TALIS analyses have shown a positive relationship between teacher professionalism and student achievement as measured by PISA results (see Figure 4.4 below), suggesting the importance of investing in policies to promote teacher professionalism (OECD, 2016[33]).

Figure 4.4. PISA scores in mathematics and overall teacher professionalism (ISCED 2), 2013

Note: The index of overall teacher professionalism relies on three domains: knowledge, autonomy and peer networks. Each of the domains is scaled from 0 to 5.0, with 5.0 representing a theoretical maximum where all practices within the domain are observed for a given teacher. The overall index is the sum of the scales between the three domains.

Source: OECD (2016[33]), Supporting Teacher Professionalism: Insights from TALIS 2013, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264248601-en.

Teachers today are increasingly expected to perform tasks that fall beyond their traditional job description (Schleicher, 2018[2]). They are counted on to provide students with both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, such as self-confidence and collaborative skills. In addition, teachers are expected to be aware and respond to students’ individual needs; and to work with other teachers and parents to ensure the proper development of their students (Schleicher, 2018[2]). A key aspect of high-performing school systems worldwide is a clear focus on continuously supporting the professional learning of its teachers (Schleicher, 2016[1]). Improving teaching and learning remains the surest way of improving the educational system as a whole – and ensuring quality initial teacher education and continued professional learning is a key policy lever in this regard (Mourshed, Chijioke and Barber, 2010[34]). Improving the quality of the teaching profession is thus – with reason – at the centre of many education policy reforms (OECD, 2013[35]).

It should be noted that initial teacher education is not covered in this report, as the analysis focuses on entry mechanisms of the SPD and continuous professional development. Another OECD report to be published in 2019 covers higher education in Mexico and provides elements on initial teacher education (OECD, 2019[36]).

The entry mechanism instituted with the SPD aims to enhance the quality of the teachers and future educators entering the profession. Recent evidence highlights that the selection process (the concurso de oposición para el ingreso, entrance examination) has contributed to improving the quality of new teachers, as they appear to have higher levels of knowledge than the cohorts entered before the concurso was established. According to some experts, the entrance examination effectively identifies the candidates who display the best levels of knowledge in mathematics and reading comprehension (de Hoyos and Estrada, 2018[37]; SEP, 2018[38]).

By allowing candidates from other professions to take the entrance examination (concurso de oposición para el ingreso), Mexico has opened the door to attracting quality candidates from broader backgrounds. Offering flexible teacher education opportunities and opening new routes to enter the teaching profession to other professionals with relevant experience can help in ensuring a quality pool of candidates for the teaching workforce (Schleicher, 2018[2]). An issue is, therefore, to guarantee that these training opportunities exist and effectively allow new teachers to develop the skills necessary to guide student learning. As of 2018, Mexico is still in the process of reinforcing these mechanisms. The interviews led by the OECD suggested that these training mechanisms still needed further improvement. Mexico has started to invest in the professionalisation of its education workforce and needs to continue building on its efforts.

The obligation for new teachers to follow a mentoring programme (tutoría) during their induction period represents noticeable progress in the SPD. In 2013, 86.2% of primary education teachers and 72% of teachers in lower secondary education worked in schools that had no induction programmes for new teachers, while only 17.5% of teachers reported having a mentor against 24.8% on average across TALIS countries (OECD, 2014[9]). Mentoring promotes teachers’ professional growth by both expanding their knowledge base and supporting them emotionally (OECD, 2016[33]). It is well documented that teachers who participate in strong mentoring are more likely to impact their students’ achievement positively and to remain longer in post (Borman and Dowling, 2008[39]; OECD, 2016[33]).

The LGSPD does not only make mentoring compulsory during induction, it also grants teachers the right to receive this support. Since 2013, three mentoring modalities were developed: flexible and in person with one mentor for one or a group of mentees; in a group, once per month in rural areas; and on line. In-person mentoring is the only modality that allows for in-class observation, an activity highly valued by new teachers (INEE, 2017[40]; Mexicanos Primero, 2018[41]). The other two modalities consist more of an induction course with a personal project for teachers to carry out in their school, but have the advantage of adapting to the difficulties small, remote schools have in accessing mentors (Mexicanos Primero, 2018[41]).

The initial years of the SPD saw a mismatch between the need for mentors and the number of teachers, supervisors, school leaders or support staff available and willing to act as mentors, but progress had been made: the SEP reported that 78% of the teachers received mentoring in 2015/16 (SEP, 2018[42]) but with uneven coverage across states (Mexicanos Primero, 2018[41]). One of the reasons for the slow start was the low response rate among experienced professionals, for whom the incentives were unclear or intangible – some mentors report not having received their monetary incentive for two years (INEE, 2017[40]; Mexicanos Primero, 2018[41]). In 2017/18, access to mentoring reached 88.9% of teachers (SEP, 2018[42]), by developing the 3 modalities and guaranteeing payment of incentives to mentors. Analysts report that challenges remain, however, both in respecting teachers’ right to mentoring and in guaranteeing that this mentoring effectively helps them improve (INEE, 2017[40]; Mexicanos Primero, 2018[41]).

Continuous professional development (CPD) is slowly evolving under the impulse of the SPD. Providing CPD is the responsibility of the 32 states, across which training and development offers vary greatly. Mexico introduced the National Strategy for Continuous Training of Teachers (2016) in basic and upper secondary education. The programme is intended to improve the skills of teachers, in particular, those showing below average results in teacher appraisals. Under this strategy, staff will choose programmes – focused on content and/or pedagogical methodology – according to their needs and the results of their appraisal. Based on the tender (convocatoria) put out for continuous professional development, 26 training organisations (instancias formadoras) were accepted as official CPD providers by the SEP. Data provided by the SEP refers to a total of 1 196 different CPD and training programmes for teachers in basic education, in the form of courses, workshops and certification programmes (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team).

The central authority also provides professional development programmes. As of 2018, 120 online courses and 46 online certification programmes (diplomados) were made available by the SEP for education professionals in basic education, and 64 different programmes were offered specifically to upper secondary education teachers (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team). This is a major challenge in Mexico: in-person training and other face-to-face professional development with tutors demand a great amount of resources given the number of education professionals and the scale of the country. The SEP started using technologies and online platforms to cope with this challenge. This resulted in 626 000 teachers, school leaders and supervisors signing up in 2017 (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team, one teacher potentially being able to complete more than one course). These training modules included the three courses offered to the teachers, school leaders and supervisors who had gone through performance appraisal (línea 1); the courses proposed as part of the SPD processes of entry, promotion and permanency (línea 2); and all other courses available (línea 3). The SEP estimated that an additional 1.2 million teachers will be completing courses specifically about the new education model in 2018 (by 4 June, it reported progress on 74% of this figure). In upper secondary education, 110 000 teachers signed up for at least 1 course in 2016 and 2017; this number was 72 000 by mid-year in 2018 (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team). The National Union of Education Workers (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación, SNTE) also has developed a range of professional development courses for teachers through its foundation Fundación SINADEP (Sistema Nacional de Desarrollo Profesional, National System for Professional Development).

Overall, many of the components for the development of a comprehensive teacher career appear to be in place in terms of teacher selection and recruitment, mentoring, availability of professional development and appraisal, reviewed in the next section. However, many of these processes appear to be excessively focused on the appraisal processes themselves, which dilutes the career perspective of the SPD.

Appraisal for quality teaching: A career perspective

The new SPD framework considers appraisal and professional development as complementary tools to enhance the quality of the teaching profession. Authentic professional appraisal, which refers to the accurate assessment of the effectiveness, the strengths and areas for development of educational professional practices (including teaching, school management, advice and supervision) is central to the continuous improvement of schooling (Santiago et al., 2012[4]). Research highlights the importance of developing systematic approaches to teacher appraisal that support continuous learning for individual teachers throughout their career and for the profession as a whole (OECD, 2013[35]). The SPD framework comprises four types of appraisal:

the entrance appraisal (concurso de oposición para el ingreso), a teacher registration process for candidates to teaching positions in basic and upper secondary education

the diagnostic appraisal (evaluación diagnóstica), a process of completion of probation for newly appointed teachers

the promotion appraisal (concurso de oposición para la promoción), an appraisal mechanism for promotion of candidates to management, supervision and counselling positions

the teacher performance appraisal (evaluación del desempeño), a regular performance appraisal for in-service teachers.

Some components build upon existing policies. For instance, the selection process to enter the teaching profession was initially made through the National Teaching Post Contest (2008-13), which aimed to improve the transparency and quality of the selection process (OECD, 2018[8]). The new registration process for teachers is open to all graduates with a bachelor’s degree (licenciados) from public or private higher education. According to SEP data, between 2014 and July 2018, more than 806 000 candidates took part in the entrance appraisal (concurso de oposición para el ingreso) in basic or upper secondary education, of which close to 400 000 received sufficient results to be considered for teaching positions. Over the same period, more than 171 000 new positions were allocated through the entrance appraisal. Studies report that with time, the quality of new entrants appears to have improved, as suggested by a comparison of the academic results of new teachers before and after 2014 (de Hoyos and Estrada, 2018[37]; SEP, 2018[38]).

The promotion appraisal (concurso de oposición para la promoción) has also had a number of candidates from 2014 to 2018. The SEP reports that during the period, more than 158 000 candidates took the assessment in basic education, of which 54.1% were estimated to be apt for new leadership positions, including school leaders or supervisors. For basic and upper secondary education, more than 175 000 teachers took the test and 53.3% passed.

However, a larger part of the debate around Mexico’s education reform package has revolved around the performance appraisal component (evaluación del desempeño) and around the discussion of whether teachers should be appraised while in-service, how and with what consequences. According to SEP data, from 2014 until 2018, more than 1.6 million educators have gone through the evaluation process. This appraisal mechanism requires some precisions.

The items used to appraise teacher performance are elaborated by CENEVAL (Centro Nacional de Evaluación para la Educación Superior, the National Centre for Higher Education Evaluation) with the participation of teachers themselves: 50 000 teachers participated since the beginning of the teacher performance appraisal (information communicated by the SEP to the OECD team). The LGSPD assigns to the INEE the responsibility for approving the elements, methods and tools to carry out the appraisal. The law determines that teachers must undergo performance appraisal at least once every four years.

The results from the professional performance appraisal are communicated by the CNSPD to the participants through an individual result report form (informe individual de resultados). As the integrated information and management system is being developed (Sistema de Información y Gestión Educativa, SIGED), these results are also being compiled in the system's database and made available for consultation to each education professional, through their personal identification (Chapter 5 provides a detailed description of the SIGED). Reports collected during the interviews with the OECD team show that, in some schools, teachers at least discuss their results with their school leaders and some use them to investigate the available offer for continuous professional training and to choose modules.

The interviews performed by the OECD team revealed two main findings. First, the teachers who had already been appraised or who knew fellow teachers who had been appraised saw the professional performance appraisal as constructive in principle. Second, numerous teachers and education professionals however, manifestly feared losing their position because of the appraisal, in spite of the low likelihood to fail repeatedly on the appraisal. SEP data show that after 5 years of teacher performance appraisal, only 0.6% of the more than 200 000 teachers appraised failed 3 consecutive times (data communicated by the SEP to the OECD team).

The reforms’ focus on student learning and school improvement implies that appraisal has consequences for educational staff. It is important to recall that, by law, the performance appraisal mechanisms include the obligation for teachers receiving unsatisfactory results to follow professional development courses in order to improve their knowledge and practice. In the case of teachers who were already in post when the law came into effect, the only risk if they receive unsatisfactory results on three consecutive performance appraisals is for them to lose their position in front of a class. This removal does not mean that the teachers lose their job in public education, but that they must fulfil other tasks than teaching in front of a class, as determined by the relevant local authority or decentralised organisation (LGSPD Article 53 and Transitory Article 8). On the other hand, three consecutive unsatisfactory results will lead to destitution for the teachers entering the profession after the law came into effect. Most importantly, people in this situation can opt for re-entry into the teaching profession through the regular entry exam now in place.

Other elements were pointed out that fuelled discontent with the performance appraisal processes. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) elaborated a detailed report assessing the implementation of the first evaluation round for teachers (UNESCO, 2015[43]). Echoing the report’s conclusion regarding the challenges of the appraisal process, the following concerns were signalled to the OECD team. First, the initial design of the appraisal itself required teachers to take a long test (up to 8 hours) on a computer (some teachers may not have the skills to properly use it), sometimes in dire conditions because the testing centres were far or did not offer the proper conditions for a test. The items on the first iteration of the test were sometimes considered inappropriate to assess teachers’ pedagogical and professional knowledge (for instance, some actors considered that too much importance was granted to administrative questions as compared to pedagogical items).

Overall, education professionals complained about the lack of information and support offered for them to prepare for the appraisal. The professionals that the OECD team met while on visit appreciated the help they could get from the school leaders and colleagues to prepare for the appraisal, yet most acknowledged that the appraisal would be hard to take if a candidate could not count on the same support. Finally, actors both in favour and opposing appraisal emphasised to the OECD the mismatch between the obligation for teachers with unsatisfactory results to improve their knowledge and practice through professional development and the mentoring and development options actually available.

In response to the criticisms, the INEE made the 2016 iteration of the appraisal voluntary, except for those education professionals who did not previously obtain favourable results. Almost 87% of education professionals still followed an appraisal process that year. This gave the institute the time to re-design the test for 2017, based on reports such as that of UNESCO, internal reflection and consultation with relevant actors in the system. With this new model, the INEE reintroduced the mandatory nature of the professional performance appraisal (OECD, 2018[8]). The new performance appraisal model consists of:

A report on the fulfilment of the professional’s (teacher, school leader or supervisor) responsibilities. In the case of teacher appraisal, both the teacher and his/her school leader fill a questionnaire which they can upload to a website.

A teaching project (or of school management, or advice and support) including pedagogical planning (or school/zone work plan), intervention and reflection on practice. The project lasts for eight weeks and is elaborated and realised by the professionals themselves in their school. Each professional receives training and has access to academic and technical guides according to his/her function.

A sit-in exam on pedagogical knowledge, curriculum and disciplines, and legal and administrative knowledge related to the profession. The test takes about four hours to complete and teachers can choose the testing centre. Support for preparation includes the offer of continuous professional development in pedagogical and disciplinary knowledge; informal support from the school leader and other teachers, depending on the schools (as reported during the OECD visit). In addition, participants had access to the guidelines that would be used by evaluators to mark their projects as well as simulating exercises. The test has between 100 and 120 items.

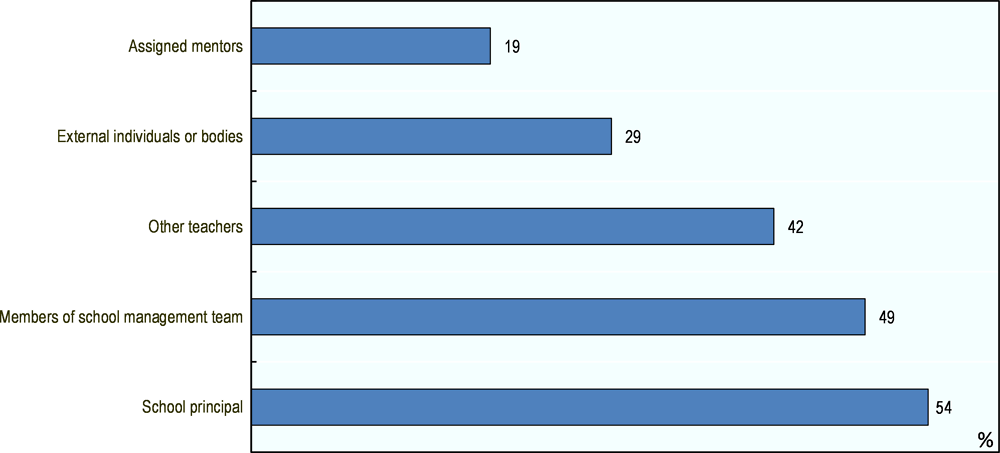

The first two components (the report and the teaching project) allow for appraising teachers in their context. These context-sensitive items make up 60% of the total appraisal, while the sit-in exam aims to evaluate the basic knowledge that all teachers are expected to master, no matter where they teach (40% of the appraisal).