This chapter presents three dimensions for rethinking international co-operation as a facilitator to support LAC countries in their transition paths to sustainable development. The first dimension looks at redefining governance based on inclusiveness. It calls for countries at all income levels to build multi-stakeholder partnerships as equal partners. The second dimension looks at strengthening institutional capacities. It places national strategies front and centre and strengthens domestic capacities by prioritising, implementing and evaluating development plans, aligning domestic and international priorities, and supporting countries in maintaining a role on the global agenda. The third dimension looks at broadening the tools of engagement to include knowledge sharing, multilateral policy dialogues, capacity building, and co-operation on science, technology and innovation. Expanding international co-operation modalities welcomes a range of actors, including public actors from different ministries in a “whole-of-government” approach. The chapter calls for ongoing analyses with LAC countries on concrete options for implementing these dimensions.

Latin American Economic Outlook 2019

Chapter 5. International co-operation as a facilitator to address new domestic and global challenges

Abstract

Introduction

While LAC countries have observed development improvements in the 21st century, sustainability is at the heart of their development agendas. The region has experienced significant socio-economic and institutional achievements. Despite heterogeneity, most countries have improved access to education and health; the emergence of the middle class has been accompanied by poverty reduction; and some countries have strengthened their macroeconomic frameworks (Chapter 1, Chapter 2 Chapter 3). In addition, countries have enhanced their institutional capacities. For instance, National Development Plans (NDPs) are aligned to the 2030 Agenda and respond to new development challenges. Regulatory and institutional frameworks have been improved to involve the private sector and the region has more domestic resources to finance development (Chapter 4). Yet, obstacles to sustain higher levels of development, exacerbated by the growing interconnectedness of the rapidly evolving global context, create new and increasingly complex development conditions.

The “new” development traps of LAC countries described in Chapter 3 represent self-reinforcing dynamics that can be transformed into development opportunities if adequate policy responses are put in place. Overcoming these development traps to turn these vicious circles into virtuous dynamics is critical to reach national development objectives and pursue the broader objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Yet, traditional recipes are not enough to overcome these development traps. The increasingly multidimensional nature of development in LAC demands sophisticated policy responses, and these require stronger domestic institutional capacities (Chapter 4). Furthermore, many of these domestic challenges either have a global scope or are strongly connected to the changing global context. Countries in the region have already shown important advancements in their domestic institutional capacities over the past decades. They have also been active in the global development agenda and therefore expressed a commitment to addressing global shared challenges. Political will and increased capacities are key for successfully converting current development challenges into opportunities. This more complex landscape calls for rethinking international co-operation for development to make it more pertinent, more participative and stronger to support LAC countries transitioning towards sustainable development.

This chapter is organised as follows. First, it presents the LAC region as a fertile ground for rethinking how international co-operation can better support the region in its transition to sustainable development. Then, it presents the role of a redefined international co-operation for development that acts as a facilitator for the region’s development efforts. The chapter goes on to suggest three concrete approaches or principles that could underpin international co-operation’s role as a facilitator, while ensuring a continued engagement with countries in the region at all levels of development. These approaches or principles embrace working inclusively, building stronger domestic capacities and operating with different and a broader set of knowledge tools. The chapter concludes with a call to continue a robust dialogue and further analysis with LAC countries to determine how best to implement concretely this vision and proposed approaches.

Is LAC ready for the new development opportunities offered by changing global and domestic contexts?

Tapping the opportunities of a shifting global development landscape

The global context is experiencing extraordinary economic, social and political changes. Several notable megatrends are shaping today’s world as well as LAC’s prospects for development. These include climate change, an ageing population, rapid technological progress, increased migration flows, the heterogeneous impact of globalisation across different socio-economic groups and the rise of social discontent across the globe.

The digital revolution, for instance, is transforming the nature of work, with the potential to both destroy and create jobs in the LAC region. Thriving in the midst of this transformation will demand ambitious policies to improve education and skills systems, to better match the demand and supply of skills, and to develop innovative social protection systems. Likewise, the digital revolution offers opportunities for LAC countries to leapfrog certain phases of their respective development paths through innovative technological solutions. Climate change also imposes significant economic losses, particularly for the most vulnerable countries, while the transition to a green economy demands large investments. However, if the right policies are put in place, then a green transition can drive job creation, competitiveness and more inclusiveness in the region.

The process of shifting wealth, by which the centre of gravity of the world economy has been moving towards Southeast Asia, has important implications for LAC’s development. As one major element of this process, China, for example, is transforming its model of growth from investment to consumption, and its middle class has been growing steadily. This, amongst other effects, will transform Chinese demand for goods and services, with direct implications on trade dynamics between many LAC countries and China. This, together with other key trends, including the growth of India, the emergence of new low-cost labour manufacturing hubs and stronger links between developing countries, can open up new opportunities for the region (OECD, 2018a).

Tapping the right policies to convert new development traps into virtuous dynamics for ongoing change

The region has made notable socio-economic progress since the beginning of the century. For instance, it has significantly reduced poverty (from 45.9% in 2002 to 27.8% in 2014; see Chapter 1) and to some extent inequality. It has enjoyed a remarkable expansion of the middle class, which now represents more than one-third (35.4%) of the population.

Yet, LAC’s critical domestic transformations require new policy responses. Productivity has been declining and remains at only around 40% of the labour productivity of the European Union (75% in 1950). Following poverty reduction, around 40% of the population is vulnerable, meaning that most work in informal jobs, with little or no social protection. Hence, they could easily fall back into poverty if they are hit by unemployment, sickness or problems associated with ageing. Additionally, linked to higher aspirations of the increasing middle class, 64% of the population have no confidence in their national governments, with 74.5% believing their institutions are corrupt. All these trends occur in a region that is home to 40% of the world’s biological diversity and where the impact of environmental challenges, mainly climate change, is already visible.

In short, LAC is facing new dynamics between past improvements in socio-economic conditions, longstanding weaknesses, the new challenges that are emerging as the region progresses towards higher income levels, and the impact of the changing global context. The combination of these factors has thus created increasingly complex development conditions – what LEO 2019 calls the “new” development traps (Chapter 3). These productivity, social vulnerability, institutional and environmental traps (Table 5.1) act as circular, self-reinforcing dynamics that limit sustainable development in LAC. Innovative structural reforms are needed to turn these vicious circles into virtuous dynamics, requiring more sophisticated policy mixes and further policy co-ordination and coherence.

Table 5.1. LAC’s Traps

|

Trap |

Description of the trap |

|---|---|

|

Productivity trap |

The export profile of some LAC countries has concentrated on primary and extractive sectors. Following openness to international markets and new international trade conditions, this concentration undermines the participation of LAC in global value chains (GVCs), and therefore leaves a large share of the productive system disconnected from trade, technology diffusion and competition. |

|

Social vulnerability trap |

It affects most informal workers, or almost half of the active population, who escaped poverty and represent the vulnerable middle class. Low levels of social protection and a low capacity to invest in improving their productivity through education and skills limits the ability of these workers to access better quality jobs. |

|

Institutional trap |

It has emerged alongside the expansion of the middle class and the associated rise of aspirations. Levels of trust and citizen satisfaction have declined, eroding the willingness of citizens to pay taxes (tax morale). This, in turn, is limiting available resources for public institutions to respond to increasing demands. |

|

Environmental trap |

Concentration in material and resource-intensive sectors may be leading towards an environmentally and economically unsustainable dynamic. The reversal to a low-carbon economy is costly and difficult, and it will become harder as the global stance against the impact of climate change may impose further costs on high-carbon models. Likewise, a high-carbon model is unsustainable since it depletes natural resources on which it is based. |

Source: Own elaboration.

In sum, socio-economic progress in LAC has come with new development challenges, which are also related to the changing international context. This context of growing interconnectedness across countries accentuates the global nature of various challenges and hence the need to adopt internationally co-ordinated responses. This is the case for global and regional public goods, including security, financial and trade stability, environmental sustainability, access to energy, and public health. These represent issues with cross-border externalities and whose preservation will very much depend on the capacity to act together. While the governance of the multilateral system is not equipped to effectively support these global and regional public goods, LAC countries can contribute to its improvement through greater involvement in it, which international co-operation can facilitate.

Tapping international co-operation opportunities to address LAC’s development traps

Turning LAC development traps into broad development opportunities will demand therefore a shift in international co-operation approaches with the region. Examples abound in a number of policy areas for international co-operation to back up further, support, strengthen, deepen and reinforce LAC’s domestic reform agenda for sustainable development (Table 5.2). In rethinking international co-operation with the region, it is important to better understand and map out what efforts exist, what impact has been achieved, what is missing, and what could be the shift of scale and focus for international co-operation to fully acknowledge the increased complexity and global interdependence of challenges.

Table 5.2. Addressing LAC’s Traps: Beyond traditional co-operation

|

Modality |

Partners |

Objective |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Productivity trap |

Triangular co-operation |

European Union and Colombia co-operating with Central American countries (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Panama) |

Entrepreneurship and Business Development in Mesoamérica: Learning about successful entrepreneurial strategies developed in Colombia, such as the experience of the Regional Network of Entrepreneurship of the Cauca Valley, to inform their own national entrepreneurship policies. This project involves both financial and technical support. So long as it can support dynamic entrepreneurship, it deals directly with some of the issues at the core of the productivity trap. |

|

Productivity and social vulnerability traps |

Multilateral co-operation |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Brazilian Co-operation Agency in seven LAC countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, Haiti, Paraguay and Peru) |

Project + Cotton (Proyecto + Algodon) Developing the cotton sector. Based on the technical expertise of Brazil, the project aims to fight rural poverty and improve the living conditions of rural farmer households by assuring their food and economic security through the productive and sustainable development of the cotton sector. |

|

Environmental trap |

Triangular co-operation |

Germany with Morocco and Costa Rica |

Improvement of sustainable management and use of forests, protected areas and watersheds in the context of climate change Exchanging experiences on the prevention of forest fires, the protection of biodiversity, ecotourism and the development of value chains. |

|

Institutional trap |

South-South co-operation |

Panama and Mexico |

Memorandum of Understanding of the High-Level Group on Security Deterring and preventing violence through the sharing of intelligence, judicial co-operation and joint action on border affairs. |

|

Environmental trap |

Multi-stakeholder partnerships |

European Union and Bill Gates-led Breakthrough Energy |

Clean Energy Fund Helping European companies that would like to develop and bring to the market new clean energy technologies. |

Source: Own elaboration.

For instance, sharing international experiences through policy dialogue helps boost productivity in LAC and promote structural transformation. Such international policy dialogue can support the integration of local firms into international markets and global value chains (GVCs) and the integration of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) into the formal productive structure. Moreover, international investment supports increases in research and development (R&D) in specific innovative sectors and helps define innovative clusters in partnership with public R&D institutions, businesses and other national and sub-national stakeholders. Capacity building can also aid the design and implementation of a national strategy.

To reinforce the social contract and eliminate social vulnerabilities, capacity building can strengthen human capital, improving vocational education and training programmes to support the vulnerable middle class. International evidence and experiences in labour regulations or the promotion of selected education programmes in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) helps vulnerable young women participate in the formal labour market. Lessons learned from other countries can be critical to support the design and sustainability of social protection systems. International fora are also key for discussing and designing policy responses related to digital transformation, turning it into an opportunity to create better jobs in the formal labour market.

To strengthen local institutions, capacity building and technological transfers greatly support the delivery of public services, such as the management of public schools and hospitals. Sharing international experiences, including on regulatory and institutional frameworks for public procurement and public-private partnerships, can help involve the private sector in public services delivery. Capacity building and new technologies in tax administration also support LAC countries’ tax capacity, along with better enforcement and communications to increase tax morale. Moreover, international co-operation, including through tax agreements and anti-corruption conventions, support anti-corruption actions as well as co-ordinated measures against domestic tax evasion and avoidance.

To promote an environmentally sustainable economic model, R&D co-operation, for instance, as well as training and technology transfers to local researchers can support diversification of exports based on countries’ biodiversity. Stronger design and implementation of regulations for legal mining and environmental licences can mitigate environmental damages. Technological transfers and targeted support in waste management can reduce adverse effects on human health and the environment. Building and enhancing international co-operation through the Paris Agreement or other international fora is an essential part of the fight against the consequences of climate change.

Strong linkages exist across all these policy issues. Policy responses, included at the international level, must be designed within the framework of shared development objectives and priorities and a common long-term vision, usually contained in individual National Development Plans of LAC countries. Adopting a “whole-of-government” approach will be critical to ensure co-ordination across ministries and across levels of government, to favour policy coherence, promote synergies and account for potential trade-offs.

Ultimately, embracing the ambition to rethink international co-operation with the region to turn LAC traps into broad opportunities for sustainable development will very much depend on whether the LAC region is ready for such a change. The next section provides some insights on how the ground is indeed fertile for changing international co-operation with the region.

Institutional capacities, social aspirations and political will: Are these enough for LAC to embrace a new international co-operation?

Several factors seems to indicate that LAC is indeed prepared – and ripe – to transition to a new international co-operation for development

First, institutional capacities have become stronger in the past decades (Chapter 4). While large room for improvement remains, LAC today has more capable and open institutions, and efforts are being made to improve trust and spur innovation in the delivery of public services (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018). For instance, National Development Plans in LAC consider the multidimensionality of development and are aligned with the 2030 Agenda. Also, the regulatory and institutional frameworks to include the private sector have improved, particularly regarding public procurement and public-private partnerships. Additionally, anti-corruption measures have been strengthened and transparency and open government policies are being implemented (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018). To finance development, most countries have increased the level of taxes relative to GDP and are actively attempting to decrease tax avoidance and evasion at the local and international levels (OECD/ECLAC/CIAT/IDB, 2018).

Second, social aspirations have increased in the region, mainly as a result of the expansion of the middle class, which now represents more than a third (35.4%) of the population (Chapter 2 Chapter 3). Equally, 25% of the population in LAC is aged 15-29, representing a group of people born and raised in democracy, as another key driver of increased social aspirations. Growing dissatisfaction with national governments and with the quality of public services confirm this direction. As many as 64% of Latin Americans have no confidence in their national governments, and 44% are not satisfied with public education (Chapter 3). Increased social demands generate the momentum for ambitious policy reforms and for co-ordinated and comprehensive efforts to build a new state-citizens-market nexus that can address existing and forthcoming challenges, reconnect with society, and foster well-being for all (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018).

Third, political will is also a pre-condition to make reform happen in the region to boost inclusive and sustainable development. Political will is fundamental to overcoming a complex set of bargains and exchanges amongst several actors with their own interests, incentives and constraints during the policy-making process of reform (Chapter 4). The possibility of alternating political power in government should give individuals the power to punish corruption, diminish the capture of states and to advance in the development agenda. Between 2018 and 2019, more than ten new governments have been elected in the region, opening new opportunities for implementing necessary reforms in those countries. Since democracy is based upon the existence of checks and balances between state powers, strengthening the tools and institutions to enforce these principles effectively is fundamental (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018).

The Latin American region’s evolving relationship with official development assistance: From aid dependence to aid as a catalyser

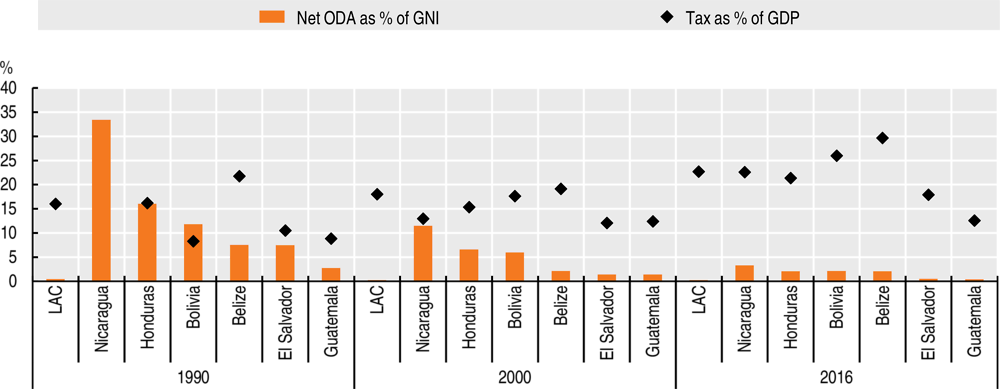

Another factor fuelling the evolution of international co-operation with Latin America is the changing nature of official development assistance (ODA) (Box 5.1). Latin American countries are not aid dependent. When compared to other flows, such as taxes, the relative importance of ODA has decreased over the past few decades (Figure 5.1). In the 1990s, most aid-dependent countries received ODA flows higher than or similar to the local level of taxation; since then, the level of public revenues has become more important than ODA. Therefore, when looking at different sources of financing for development, relative ODA flows have decreased gradually compared to domestic public sources of financing. This has occurred even though tax levels remain low compared to OECD member countries.

Box 5.1. Development assistance in Latin America and the Caribbean

ODA flows to the LAC region have decreased given the composition of countries by level of income. Only one country in LAC is a member of the least developed countries (LDCs) and other low-income countries (LICs) category (Haiti). Only four are members of the lower middle-income countries (LMIC) grouping (Plurinational State of Bolivia, El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua). The upper middle-income country (UMIC) grouping has seen substantial falls in ODA from the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC). All other countries in the region are either in UMIC or the high-income country (HIC) grouping (including Argentina, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, and 13 other Caribbean economies). Chile and Uruguay are now formally HICs and are graduating from ODA.1

The data are somewhat ambiguous regarding official development assistance provided to the LAC region. While some declines are clear relative to other regions, LAC has maintained a certain amount of real-term spending. Nevertheless, the need is clear to engage with the changing context and prepare for a future with potentially reduced levels of ODA. In the case of LAC, several economies have improved their income status in recent years. For instance, from 2010 to 2019, Belize, Ecuador, Guatemala, Guyana and Paraguay moved from the lower middle-income to upper middle-income category. Other economies also upgraded to high-income status during the same period, including Antigua and Barbuda, Chile, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Uruguay. In 2019, Argentina and Panama joined this group as well. Some upper middle-income countries (such as Costa Rica and Mexico amongst others) are expected to become high-income in coming years if they maintain levels of per capita income growth.2

As in other regions, most ODA to LAC is directed at social sectors (USD 4.4 billion in 2016). About USD 2.2 million is spent on economic infrastructure and services and about USD 936 million on production sectors. While social sectors receive twice as much ODA as economic infrastructure, the latter has seen a sevenfold increase in recent years. Specifically, funding for economic infrastructure has increased from just over USD 300 million (in constant 2016 USD) to over USD 2.1 billion between 2002 (when figures begin) to 2016. In contrast, spending on social sectors dropped from a high of USD 5.2 billion to just under USD 4.4 billion between 2011 and 2016. This implies that a gradual shift from social to economic spending has been underway for at least a decade.

1. See World Bank income classification at https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

2. Based on International Monetary Fund projections for GDP per capita applied to World Bank GNI per capita figures (Atlas method, current USD) for countries on the DAC list of ODA recipients. To consider inflation, an annual increase in the income threshold is applied equivalent to the average increase offer over the five years from 2010-16 in the deflator for Special Drawing Rights (SDR); this is used for annual revisions of all income categories. For the period beyond IMF projections, the dataset is extrapolated based on the average projected growth rate of the five years from 2018-23. The extrapolated growth figures are capped at a maximum of 10% per year.

Figure 5.1. Taxes and ODA in the six most aid-dependent Latin American countries in 1990

(1990, 2000 and 2016)

Note: Net ODA received as a percentage of GNI and tax revenues as a percentage of GDP. Net ODA consists of disbursements of loans made on concessional terms (net of repayments of principal) and grants by official agencies of the members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), by multilateral institutions, and by non-DAC countries. It includes loans with a grant element of at least 25%.

Source: OECD, www.oecd.org/dac/stats/idsonline and Global Revenue Statistics database (2018) and World Bank (2018).

As international co-operation evolves to better respond to today’s realities, ODA, even in decreasing amounts, can still play a role in catalysing change in middle-income countries. This is particularly true for LAC, which is mostly a middle- and upper middle-income region. Rather than graduating from aid itself, countries emerge from dependence on aid, which is a crucial distinction. Dependence on ODA can undermine the development of institutions and domestic capacities over the long term. Overall, dependence on aid is generally agreed to be harmful (Glennie, 2008).

However, low aid dependency levels, compared to GDP and government expenditures as LAC shows, can support progress. Country-specific studies demonstrate this particular point. For instance, the evaluation of aid to Colombia found that in certain fields – such as the environment, institutions and productive system as well as problems related to the struggle against inequality, internal displacement and human rights violations – the selective use of aid financing, expertise and shared experiences was a determining factor in achieving better development results (Wood et al., 2011).

LAC’s particularities, including the region’s evident non-dependence on ODA, increased capacities, will for progress and increasingly active global role, represent an opportunity to test how different frameworks and modalities of co-operation can help leverage domestic efforts. It is also an opportunity to show how ODA can act as a catalyser of other sources of funding and how both financial and non-financial resources can be combined and directed to advance nationally owned and driven development processes.

The role of international co-operation for development as a facilitator

What does a facilitating role in international co-operation mean?

The role of international co-operation as a facilitator needs to draw on ODA as a catalyser of additional resources. Yet, using aid as a catalyser of further financial resources is not new. A similar concept of “aid as a catalyst” emerged in the late 1960s, claiming that financial assistance should be allocated where it is expected to have the maximum catalytic effect on mobilising additional national efforts (Rosenstein-Rodan, 1969; Pronk, 2001, Kharas et al., 2011). Similarly, scholars have emphasised the idea of co-operation based on incentives, specially when it comes to co-operating with middle-income countries (Alonso, 2014).

But, the catalytic role of ODA at present is not enough. Mobilising sufficient resources beyond ODA, leveraging the synergies between them and ensuring that investments of all types are contributing to the SDGs are overarching challenges for governments in financing sustainable development. Domestic resource mobilisation is central to this agenda. In fact, while the level of taxes in relation to GDP has been increasing in the past years (by close to two percentage points in the last decade), this ratio is still low. In 2016, the average tax-to-GDP ratio at 22.7% for LAC countries was low compared to 34.3% for OECD countries (OECD et al., 2018).

Still, international co-operation’s facilitating role needs to draw on other key tools for supporting countries in implementing their national development priorities and aligning them with the SDGs. These tools include capacity building, policy dialogue and technical assistance. Governments need to strengthen their policy and institutional frameworks to manage national challenges.

International co-operation as a facilitator of countries’ development efforts promotes nationally driven development processes, aligns countries on an equal footing as peers for exchanging knowledge and learning, builds on existing capacities of countries and creates new ones to spur national and global reforms, and supports aid as a catalyser for additional and varied sources of funding. As the international community responds to the more comprehensive and universal 2030 Agenda, as countries converge towards similar levels of development and therefore share an increasing number of domestic and global challenges, and as dependence on ODA diminishes, the role of international co-operation as a facilitator of a country’s own development seems to be rising as a viable response to current realities.

LAC has a fertile ground for testing international co-operation as a facilitator for development. International co-operation can play a facilitating role in supporting governments in the region turn current development traps and vicious circles into virtuous ones that reinforce positive dynamics at the institutional, social, productive and environmental levels. It can also ensure that LAC governments have sufficient capacity at national and sub-national levels to shape and deliver the global public goods agenda. This may be particularly relevant with respect to global public goods related to the environment. Compared to other ministries, environmental entities tend to be politically weaker and with fewer resources (Nunan et al., 2012).

What can also offer some good practices for exploring how the region can embrace international co-operation as a facilitator is LAC’s existing regional co-operation. Such regional co-operation takes many forms. Heads of Government in a geographical region, for example, can agree to work together on a range of issues at political fora. For their part, academics, scientists or public servants can build regional platforms to share insights. For instance, the Pacific Alliance, an initiative by Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru, promises to drive further growth, development and competitiveness in the region. At the same time, it is a platform for political, economic and commercial integration (Pacific Alliance, 2019). Regional co-operation can very well be a first attempt at international co-operation as a facilitator.

Adapting approaches to current realities: The context is ripe for a facilitating role for international co-operation

Changes in the developing world’s specific reality, including the LAC region’s particularities, have been accompanied by an ongoing macro-evolution of international co-operation as a development tool. Technical assistance was followed by community support in the 1950s. Trade and investment were the key tools in the 1960s, fulfilment of basic human needs in the 1970s, assistance for structural adjustment and debt relief in the 1980s, humanitarian assistance in the 1990s, and, at the turn of the century, human development was at the top of the priorities (Pronk, 2001). These different approaches created many lessons for how to deal with different phases of development, since achieving socio-economic successes has also given rise to new bottlenecks requiring alternative policy responses.

With the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the focus was primarily on achieving national development goals in developing countries, such as ending poverty and hunger, achieving universal primary education, reducing child mortality, or improving maternal health. The decision reflected a preoccupation with the realities of poverty and economic and social differences amongst countries. In 1981, poverty and extreme poverty rates were globally high: 44% of the world’s population lived in absolute poverty. Since then, the share of poor people has declined faster than ever before. In 32 years, the share of people living in extreme poverty was divided by four, reaching levels below 11% in 2013 (Roser and Ortiz-Ospina, 2017). In LAC specifically, poverty decreased from 11.5% to 3.7% between 2000 and 2016 (World Bank, 2019).

As the MDGs ended in 2015, international co-operation needed a much wider focus. The different agreements reached in 2015, along with the 2030 Agenda, reflect a world that is converging. Since the 2000s, 26 countries moved from low-income to middle-income status, and 14 from middle-income to high-income status (World Development Indicators, 2017). LAC economies are converging as well, transforming the region into middle-income status. In 2018, Chile and Uruguay joined a growing list of high-income countries in LAC that includes Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Saint Kitts and Nevis, and Trinidad and Tobago. In 2019, Argentina and Panama also joined this list.

Unlike the MDGs, the 2030 Agenda sets out a wide range of economic, social and environmental objectives and calls for a new approach to face these objectives effectively, including integrated solutions given their interrelated character. In this sense, the 2030 Agenda gives special attention to global public goods with a holistic approach. This international agenda reflects a world with new development dynamics and sustainable goals that put global public goods at the centre of international policy. Amongst the 17 SDGs are those pertaining to, clean energy, responsible consumption and production, climate action, and biodiversity that clearly require the provision of global public goods. Furthermore, the universal nature of the SDGs means that all countries – advanced, emerging and developing economies alike – have committed to delivering this agenda.

Adapting international co-operation approaches to the current global context is ongoing and still requires further efforts from the international community, particularly for shaping the most suitable tools, actors and frameworks for implementation. While reaffirming the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, the 2030 Agenda’s broader scope suggests a call, for instance, for more inclusive governance settings. Such settings allow diverse actors to interact on an equal footing to tap into existing efforts and capacities of countries who have the will to continue pursuing their path to development and to tap into a wider range of tools, including those, in many cases, deployed by non-traditional actors in development co-operation (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. What is international co-operation?

International co-operation is a broad concept covering all aspects of co-operation between nations. Co-operation can be defined as “the co-ordinated behaviour of independent and possibly selfish actors that benefits them all”, as opposed to working in isolation, conflict or competition (Dai et al., 2010). And, global governance can be understood as the institutionalisation of this co-operation (Lengfelder, drawing on Keohane, 1984).

International co-operation can include a variety of instruments for co-operation between countries; international co-operation for development is defined as international action intended to support development in developing countries. It includes different sources of financing, sometimes blended in various ways, and involves a range of different actors, beyond the usual development co-operation actors. It includes technology facilitation and capacity development as well as multi-stakeholder partnerships clustered around sectoral or thematic issues. It also includes normative guidance and policy advice to support implementing agreed goals (ECOSOC, 2015).

The context is therefore ripe for starting a reflection process for how best to stress international co-operation as a facilitator. Time is short, and the need for transformation is enormous. The next section suggests some options or principles for speeding up this transformation when it comes to LAC.

How to speed up the transformation of international co-operation as a facilitator for sustainable development?

International co-operation as a facilitator for sustainable development should be strengthened gradually. To feed this gradual transformation, the following sections present some ideas on next steps for international co-operation to continue evolving towards an inclusive model that fully involves all countries on an equal footing, despite their level of development, along with a wider range of actors and a wider range of tools.

At the core of this inclusive model, multilateral and multi-stakeholder partnerships should be mutually beneficial and focused on shared domestic and global issues. Co-operation efforts should be integrated and nationally shaped and driven, putting LAC development priorities and plans front and centre. Emphasis should be placed on strengthening countries’ domestic capacities, including contributing to the alignment between domestic and international priorities, but also supporting countries in the region as they continue playing an active role in the global agenda. Additionally, international co-operation needs to expand its set of modalities or instruments to fully embrace the expertise from a wider range of actors. This requires paying special attention to bringing in public actors from different ministries in a “whole-of-government” approach. A greater focus should be given to technical co-operation, such as knowledge sharing, multilateral policy dialogues, capacity building, access to technology, and co-operation on science, technology and innovation.

Speeding up the transformation of international co-operation requires therefore rethinking systems structurally and building a fit-for-purpose machinery that will be better adapted to current realities. Three key dimensions (Table 5.3) are at the core of the proposed evolution that international co-operation should pursue for a more inclusive, integrated and balanced approach that better responds to current domestic and global realities. Subsequent sections will expand and describe more in detail each one of these three dimensions.

Table 5.3. Key dimensions for rethinking international co-operation as a facilitator for sustainable development in LAC

|

Dimensions |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Working inclusively |

Engaging countries at all development levels on equal footing as peers, to build and participate in multilateral and multi-stakeholders partnerships to tackle shared multidimensional development challenges with multidimensional responses. |

|

Building domestic capacities |

Strengthening countries’ capacities to design, implement and evaluate their own development policy priorities and plans, encouraging the alignment between domestic and international priorities and ensuring integrated approaches to more complex and interlinked challenges. |

|

Operating with more tools and actors |

Expanding instruments for greater international co-operation, such as knowledge sharing, policy dialogues, capacity building, technology transfers, and including more actors, including public actors in a “whole-of-government” approach. |

Source: Own elaboration.

The governance model: Working inclusively on shared issues

New actors, but an outdated governance structure

The last globalisation wave revealed a new level of multi-polarity and complexity associated with the growing economic and political relevance of emerging actors. National and location-specific perspectives are not enough to harness change in a borderless world. New and more comprehensive perspectives for co-operation are needed as development challenges spread across regional and national borders.

For instance, the intergovernmental association of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) had already become a significant weight in the global economy by 2006. BRICS represent 42% of the world’s population, 26% of land territory and nearly 30% of world GDP (RIS, 2016). These new agents of development have transformed the dynamics of development co-operation, bringing a vast range of co-operation modalities to the agenda.

Equally, the international public finance system is increasingly a significant actor in international co-operation. The creation of both the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank and the New Development Bank increased the amount of capital available for infrastructure development. These could provide global public goods, for example, by financing clean energy and mitigating the consequences of climate change.

Consequently, the governance structure has to adapt to reflect this new context, emerging issues and rising actors. New governance schemes, including partnerships, are needed for the world to face increasing development challenges. The governance of financing co-operation should go beyond ODA and increasingly promote and encourage countries at all income levels to collaborate, as equal partners, to discuss and exchange on shared policy issues, including how to address global trends and global public goods.

Policy partnerships: Countries exchange as peers on shared domestic and global issues

Successfully adapting global efforts or governance frameworks to the new set of shared goals, as stated in the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda, requires building collective and co-operative action at the international level. This entails more horizontal relationships amongst all countries, moving away from traditional bilateral relations and from existing country categorisations sometimes based on income. More concretely, such action needs to take on board policy dialogues on shared issues amongst countries as equal partners or peers.

Existing country categorisations might have already limited collective and co-operative action on shared challenges. While dominant analytical country categories used to classify developing countries by income levels are useful for worldwide comparisons, they fall short for a policy analysis of development. These categories have been contested for not allowing aid agencies in particular – and international co-operation actors overall – to understand the development challenges facing the diverse developing world (Vazquez and Sumner, 2013).

Equally, country groupings – such as those defined by income, conflict and fragility, indebtedness, or landlocked status – often signal certain policy priorities for aid donors. Yet, the proliferation of these categories has shown very limited scope for coherently tracking the developing world’s increasing heterogeneity and the international community’s growing diversity. Adapting international co-operation to the current needs of development may very well make it necessary to evolve towards other types of country classifications. Identifying critical development issues and then defining corresponding ad hoc groups to discuss co-operative responses to those particular issues is one concrete way of changing the focus of policy partnerships (Alonso et al., 2014).

Effectively tackling domestic and global shared issues requires policy dialogues amongst countries as equal peers. Development dialogues and ensuing strategies need to be multilateral to allow developing countries to be heard, transforming the formation of individual country agendas into the proactive shaping of global policies (OECD, 2018a). Discussions should be on shared issues, rather than sectors. This allows integrated approaches, where countries better understand and tackle potential transboundary or spill-over effects of policies from other countries, ultimately promoting policy coherence at the international level.

Multi-stakeholder partnerships: Development actors unleash the fuller potential of co-operation

Partnerships including actors other than governments, such as the private sector or civil society, have great potential too. In fact, the adoption of multi-stakeholder partnerships has gained political terrain in recent years as a good, inclusive alternative for responding to increasingly interconnected global challenges (Box 5.3). For instance, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) brings together government reformers and civil society leaders in LAC to create action plans that make governments more inclusive, responsive and accountable. Already, 16 LAC countries have signed the OGP’s Open Government Declaration, a multilateral initiative for promoting transparency, fighting corruption and empowering citizens. Of the 16 signatories, 11 have already presented second or third-generation action plans, highlighting their commitment to the initiative (OECD/ECLAC/CAF, 2018).

Box 5.3. Multi-stakeholder partnerships: Still unmet potential?

The multi-stakeholder partnership governance model has long been a key tool for facing globally interconnected issues. In the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002, “Type II partnerships” were defined as collaborations between national or sub-national governments, private sector actors and civil society actors, who form voluntary transnational agreements to meet specific sustainable development goals (Dodds, 2015). Since then, these types of partnerships have been an integral part of most of the multilateral agreements on development. Guidelines and recommendations are constantly updated and implemented for how to build more inclusive and effective partnerships (for instance, the Bali Guiding Principles).

One of the keys to the success of multi-stakeholder partnerships is that they are based on shared challenges or policy issues. Goal-based public-private partnerships have delivered results in the health sector through, for example, the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation, bringing immunisation to developing countries in conflict. Other examples are the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, the Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership, the Forest Stewardship Council and the UN Global Compact (Biermann et al., 2007). Results are achieved precisely because of the issue-specific clusters of expertise around which diverse actors gather.

Today, multi-stakeholder partnerships are a fundamental tool for progressing towards the SDGs. These types of partnerships offer a new way of doing business: having genuine debates about policy, clear commitments from every side, good procedures for independent review and the possibility of redress if things go wrong (Maxwell, 2004). For the future implementation of the 2030 Agenda, such an approach offers the opportunity to assess progress and implement changes for more impactful results in the long term.

Multi-stakeholder partnerships help address the lack of regulations and solve collective problems at the international level. By bringing together key actors from civil society, government and business, these partnerships face three main governance deficits of inter-state politics: the regulatory deficit (providing avenues for co-operation in areas were inter-governmental regulation is lacking), the implementation deficit (addressing the poor implementation of inter-governmental regulations that do-exist), and the participation deficit (giving voice to less privileged actors) (Biermann et al., 2007). In this scenario, multi-stakeholder partnerships represent an alternative for facing the most urgent needs of global sustainable development, and their potential has to be fully realised as more inclusive governance models are designed.

Financing “inclusiveness” in the era of global public goods: Lessons from ODA and development banks

Global public goods certainly need partnerships set on equal footing and inclusive governance mechanisms, but these alone may not be enough. The provision of many global public goods will require massive investment in and by developing countries. These governments, however, may be inclined to focus resources on national policy priorities (Kaul et al., 2015). If low- and middle-income countries are to participate fully in providing global public goods, then the international community must redesign the multilateral system. Ultimately, it must ensure these countries have access to appropriate international public finance (Kaul et al., 2015; Rogerson, 2017).

In this vein, some have argued for the conceptual and practical separation of ODA and finance for global public goods (Kaul, 2003; Kaul et al., 2015, 1999). While ODA can be considered as transfers to finance development in low- and lower middle-income countries, for example, finance for global public goods could be seen as a payment for a service. Applying this principle could transform the system of international public finance and unlock resources for LAC countries to participate more fully in the provision of global public goods.

Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) also have a role to play in delivering global public goods via global agreements (Battacharya et al., 2018). In addition to traditional country-lending programmes, MDBs could lead strategies to help middle-income countries address global challenges. While some countries may be unwilling to incur debt for projects whose benefits will have positive spillovers regionally or globally, such as climate change mitigation or disease control (Prizzon, 2017), MDBs could, for instance, provide incentives and act as multilateral co-ordinators to undertake these collective efforts.

Both MDBs and regional banks have proven highly effective at helping countries strengthen policy and institutional foundations and leverage finance. This is particularly evident for the Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). Loan disbursements reached around USD 51.7 billion and USD 38.1 billion from the IDB and CAF, respectively during the period 2013-17. In 2017 alone, both institutions disbursed more than USD 10 billion; more than half of their loans were allocated to infrastructure sectors (CAF, 2018; IDB, 2018). In this scenario, the ground is fertile for these banks to realise their full potential by supporting countries in the region as key players in a more inclusive co-operation for development that also supports global public goods.

Building capacities of countries in Latin America and the Caribbean

Building stronger institutional capacities at the domestic level in LAC countries is another pillar in rethinking the role of international co-operation as a facilitator to higher levels of development. Despite countries in the region having improved their capacities, developing even stronger and more innovative skills is still crucial for governments in the region to be able to face both changing and challenging global and domestic contexts as well as the increasing interrelation between the two.

A renewed international co-operation with the region should have at its core the national development strategies developed by LAC countries. It should focus on improving their planning exercises by strengthening individual country capacity to design, implement and evaluate their own development policy priorities and plans. The plans should be based on the principles of policy coherence, and should be accompanied with additional instruments that go beyond the political cycle (Chapter 4). Simultaneously, such co-operation encourages the alignment of national efforts with global shared challenges and global public goods to increase efficiency and facilitate an active and seamless participation of LAC countries in the global agenda.

Building capacities for better aligning planning with the global context

The nature of today’s regional and global challenges requires thinking beyond countries’ borders. National strategies should further internalise regional and global public goods, accounting for the interdependence between domestic policies and global dynamics. The new development context has new rules, new environmental constraints, new technologies and more competition. Domestic development strategies need to adapt to these changes and reflect a country’s context, endowments and institutions (OECD, 2018b).

LAC countries are already active in connecting their national development priorities to the SDGs. Most NDPs in the region are aligned with the 2030 Agenda and monitor the advances of several indicators within the 17 SDGs. Indeed, SDGs have been used as a tool for both policy priorities and also for monitoring achievements of such plans. All of the last development plans in 12 Latin American countries were aligned for each of the objectives or policy pillars for one or more of the SDGs.1

Yet, NDPs in LAC fall short when considering global mega trends, challenges and opportunities. Global public goods, such as safeguarding the environment, and global mega trends have traditionally played a small role in these plans. Most NDPs focus on modernising public services, citizen security, growth and formal employment, infrastructure development, investments in science and technology, quality of education, and access to basic services (Chapter 4). Many also include elements where the global agenda is crucial for achieving these priorities, such as the future of work, digitalisation and productivity, but they do not necessarily emphasise collective efforts to achieve these common goals.

For international co-operation’s facilitation role with the region towards higher levels of development, stronger efforts could build the capacities of government officials and planning ministries in LAC to better understand the links between global trends, global public goods and domestic policy choices, including the transboundary effects of national policies from other countries. Additionally, spaces could be created to exchange this knowledge amongst countries, share experiences and identify best policy solutions given the global context.

Building capacities for better connecting planning with co-operation efforts

The Addis Agenda reiterated that nationally owned sustainable development strategies supported by integrated national financing frameworks should guide how a country engages in development co-operation. The reason behind this is that, at the country level, implementing well-defined national development co-operation policies, linked to a country’s national sustainable development strategy, has been identified as a practical step for more accountable and effective development co-operation (UN, 2017).

Drawing from this lesson, connecting planning with international co-operation efforts is particularly relevant for LAC where most of the countries are often both donors and recipients. To strengthen policy design, implementation and learning, countries should ensure national development strategies inform how they engage in international co-operation. Such co-ordination is likely to increase the impact of both national strategies and international co-operation. This is especially challenging for countries where different institutions lead each of these strategies. Co-ordination between planning and co-operation efforts takes place in various ways in the LAC region, from the same ministry co-ordinating both planning and co-operation priorities to specific structures following co-ordination, to simple regular communication and co-ordination amongst different institutions (Table 5.4).

Table 5.4. Co-ordination institutions in selected Latin American and Caribbean countries

|

Type of co-ordination |

Example |

|

|---|---|---|

|

The same institution deals with planning and co-operation priorities |

Dominican Republic |

The Ministry of Economy, Planning and Development has a dual role in planning. It co-ordinates both the country’s development plan and its international co-operation strategy, creating synergies amongst both. |

|

The same institution in the country deals with planning and co-operation priorities |

Guatemala |

SEGEPLAN (Secretaría de Planificación y Programación de la Presidencia) oversees planning, capital public expenditure and international co-operation. These complementary roles help align international co-operation policies with national priorities, and in particular the NDP called “K’atun, nuestra Guatemala 2032”. |

|

Other structures could also allow co-ordination between co-operation and policy priorities |

Uruguay |

The international co-operation strategy is aligned with the country’s national development strategy through its five-year results-based budget. Priority areas are well detailed in the budget. Thus, international co-operation supports such priorities through both sectoral policies and transverse medium- and long-term policies (such as climate change and gender). |

|

Regular co-ordination amongst different institutions |

Colombia |

International co-operation efforts are aligned with the NDP, which is itself aligned with Agenda 2030 and the SDGs. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with support from the Colombian Agency for Co-operation and the National Planning Department, leads negotiation of co-operation with bilateral and multilateral donors. |

|

Regular co-ordination amongst different institutions |

Brazil |

The Brazilian Co-operation Agency of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has the legal mandate to ensure alignment of international co-operation with the country’s foreign policy and NDPs. |

|

Regular co-ordination amongst different institutions |

Argentina |

The General Directorate of International Co-operation of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Worship co-ordinates technical co-operation in line with the country’s national plan |

|

Regular co-ordination amongst different institutions |

Costa Rica |

International co-operation follows priority sectors defined in the NDP. |

Source: Own elaboration.

To ensure alignment and increasing effectiveness in both planning and international co-operation efforts, capacities should be deepened in LAC governments to create appropriate co-ordination mechanisms. These can take the form of specific bodies or co-ordination systems amongst institutions. Exchanges of good practices between countries could also be put in place to facilitate learning amongst countries’ experiences on these issues.

Building capacities for successfully participating in the global agenda

LAC countries play a crucial role in the global agenda. Indeed, they have taken part in major global agreements. For example, 32 LAC countries have signed and ratified the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change. More recently, most countries in the region signed the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in December 2018.

Beyond signing agreements, LAC countries have actively shaped negotiations. During discussions for the 2030 Agenda, Brazil proposed the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”. This was in line with outcomes of the “Rio+20” United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012, and strongly pushed the technology transfer agenda (Lucci et al., 2015). Colombia also played a key role in formulating the SDG agenda and provided an influential first proposal for the SDGs (Lucci et al., 2015). In fact, several LAC countries were closely involved in defining the SDGs. These countries now actively report progress in aligning their development plans with the SDGs on the occasion of the High Level Political Forum, which plays a central role at the global level in the follow-up and review of the 2030 Agenda.

International co-operation as a facilitator in the region should ensure that LAC countries remain active and have the capacities they need to continue contributing to the global agenda. From environmental issues, to migration, to global social protection, or to health, ensuring this active role from LAC can bring positive spill-overs for other countries and help the global community better face global challenges.

Tapping into a broader set of instruments and actors

Shifting international co-operation as a facilitator to higher levels of development in LAC also needs a broader set of tools beyond traditional ones, including a more technical conversation amongst partners based on knowledge sharing, policy dialogues, capacity building exchanges, and technology transfers. It should also use the potential of South-South and triangular co-operation as stepping stones for using this broader box of tools. Equally, important will be to place these tools in the hands of a wider range of public actors, including those across various ministries in a “whole-of-government” approach. The use of these expanded toolbox can generate richer interactions from diverse sources of expertise to tackle complex social, economic and environmental sustainability issues. The 2030 Agenda already offers some ways for rethinking the set of modalities that would better suit the specificities of the LAC region.

Co-operation modalities in the post-2015 era

The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs come with a wider set of instruments or modalities. Supporting a new international development framework that goes beyond just poverty reduction and also includes social, environmental and economic sustainability entails using a much wider range of instruments. The array of options is wide and could expand in the years ahead given the increasing number of shared and interlinked challenges between countries. SDG 17 covers comprehensively many of these modalities (Table 5.5).

Table 5.5. Examples of co-operation modalities for development based on SDG 17

|

Finance |

|

|

Technology |

|

|

Capacity building |

|

|

Trade |

|

|

Policy and institutional coherence |

|

|

Multi-stakeholder partnerships |

|

|

Data, monitoring and accountability |

|

Source: Based on SDG 17 targets available at https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg17.

Opportunities abound to enhance international co-operation with alternative tools. As the number of shared global challenges is increasing and many countries are gradually rising up the income ladder to emerge, on the international scene, they become interested in sharing, learning and exploring complementary strengths with their peers that go beyond traditional roles. Latin America is already leading in this rebalancing of the mix of co-operation modalities. Countries in the region are key actors in knowledge sharing, an increasingly used modality of international co-operation for development. Brazil, for example, has made a concerted effort to step-up its international participation, increasing relations and South-South knowledge exchanges with African and other Latin American countries.

Rebalancing the set of modalities: Adapting to LAC’s specificities

Stronger institutional capacities, increasing social aspirations, deeper political will for reform and growing non-dependence on aid are just some of the reasons that confirm that the time is ripe to rethink how to rebalance the use of the various tools at hand when co-operating with LAC. Adding new tools is also necessary as LAC countries develop and face emerging challenges and development traps that require that they rely less on financial assistance,2 including budget support and project aid (or in-kind), and benefit increasingly from other co-operation modalities.

Rebalancing instruments: Towards greater technical co-operation

Rebalancing the instruments used in the region might be a natural step to better using and catalysing decreasing financial assistance and leveraging exchanges amongst peers on key shared issues. A good example of such rebalancing can be found in the OECD’s own history and evolution (Box 5.4). Some instruments that might be worth strengthening include capacity building and support, multilateral policy dialogue, technological transfers, efforts for policy exchanges, and more innovative blended financing.

Box 5.4. From the Marshall Plan to the OECD: Evolution from financial to policy co-operation

As countries evolve and development challenges and opportunities change, co-operation should also adapt. A clear example of this was the shift from the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OEEC) established in 1948 to run the Marshall Plan for Europe’s reconstruction to the birth of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). While co-operation led by the OEEC initially was based purely on financial aid, development dynamics transformed such co-operation into policy exchanges.

Sparked by the need to address Europe’s post-war welfare, the Marshall Plan helped governments recognise the interdependence of their economies and it paved the way for co-operation to promote Europe’s recovery (OECD, 2018a). It consisted mainly of a US initiative in 1948 to financially support most Western European countries with about USD 13 billion, an amount equivalent to around USD 135 billion in 2017.

Yet, once post-war Europe entered its new development path, the OEEC’s mission ended and the organisation faced the choice of dissolving or re-inventing itself. In 1960, the organisation decided to re-invent itself and was repurposed for policy discussions as a more global OECD (Leimgruber and Schmelzer, 2017). A year later, the OECD Development Centre was created as an independent platform for knowledge sharing and policy dialogue between OECD and non-OECD member countries. The Development Centre allows these countries to interact on an equal footing (OECD, 2018a).

OECD member countries co-operate by providing and sharing knowledge, organising policy dialogues, setting international standards, and designing and implementing public policies based on evidence. Policy areas, which represent common challenges and demand a whole-of-government approach across various ministries, include economic development, education and skills, environment, financial and non-financial markets, public governance, labour and social affairs, science and technology, statistics, taxes and territorial development.

Moreover, OECD standards level the playing field, increase technical co-operation, boost efficiencies and prospects for development, and contribute to domestic implementation of shared global policy objectives. For instance, the implementation of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) measures is underway, closing loopholes that cost governments between USD 100 billion to USD 240 billion per year. The Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) identified EUR 93 billion in additional tax revenues through voluntary compliance mechanisms and offshore investigations (OECD, 2018c). The Programme of International Student Assessment (PISA) and the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) measure the performance and returns on investments in skills and education. Finally, member governments and industry working through the OECD’s Environment, Health and Safety Programme generate more than EUR 309 million in savings per year (OECD, 2019).

If the region is to achieve the SDGs, then capacity support and mutual learning are key. Capacity building has long been an integral part of aid, but the changes in the international agenda suggest it will grow in importance in the years ahead. Mutual learning or policy dialogue remains a key component for development, particularly as countries experiment with new development strategies. Careful experimentation with different development strategies and improvisation guided by the knowledge of what has, and has not, worked around the world have been key in today’s emerging economies and will continue to be crucial (OECD, 2018b).

Meanwhile, policy changes3 will also be necessary for almost all of the SDGs in LAC. A crucial part of co-operation goes beyond transferring resources and sharing and building capacity. It also demands working together to build rules and implement agreements to further joint goals. This is the essence of international co-operation. At the national level, this implies reviewing public policies in light of their effects on the region’s development agenda. At the international level, it implies building more enabling rules for regional governance.

Adopting a “whole-of-government” approach: Broadening actions, tools and actors

Effectively tackling the complexity of domestic and global shared challenges requires integrated approaches that involve different types of actors. Following a structure of isolated policy silos does not work. Adopting a “whole-of-government” approach will be critical to overcome the complex current development traps in LAC countries.

A clear example is the fight against informality in the LAC region, an issue of multiple causes and consequences. A comprehensive strategy to promote formal jobs must bring together policies that: improve productivity through more and better education and skills, adapt the institutional framework to provide incentives for firms and workers to become formal, create enabling conditions for the creation of formal jobs, and strengthen inspection and supervision capacities. Such a comprehensive strategy must involve different tools and ministries, including education, labour, finance and production ministries, as well as national, regional and local representatives. The Consejo Nacional de Competitividad y Formalizacion in Peru, for instance, includes formalisation as a key item within the broader national development strategy and has the mandate to co-ordinate action across line ministries and agencies. Another relevant example is Colombia, where the 2012 tax reform involved not only the Ministry of Finance, but also the Ministry of Labour as one of the main objectives was to boost job formalisation by reducing non-wage labour costs for employers.

Another example is addressing international migration by aligning national strategies with international co-operation. In fact, the way national migration policies are designed and implemented can have transnational effects. Migration’s potential can only be fully realised when policy makers avoid operating in silos (Box 5.5) (ECLAC/OECD, 2018).

Box 5.5. International co-operation and coherent policies can enhance migration’s contribution to the development of Latin America and Caribbean countries

International migration has been an integral part of the LAC region’s social and economic development. The number of international migrants who were born in LAC countries increased from 15.4 million in 1990 to 24.8 million in 2000 to 37.7 million in 2017 (UNDESA, 2017). The main destinations, namely the United States and the European Union, remain outside of the region. However, intra-regional migration has also been increasing and diversifying in recent years. In 2017, 64% of the 9.5 million immigrants living in the LAC region were born in another country in the region. This is a sharp increase from 58% in 2000.

These significant migration flows entail important development potential in LAC. The 2015 Addis Ababa Action Agenda (UN, 2015a) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (UN, 2015b) acknowledge the positive contribution of migrants, both in their countries of origin and destination. Notwithstanding the challenges of migration, emigration relieves pressures on the labour market. Furthermore, remittances and return migration spur investment in financial and human capital in the countries of origin. In destination countries, immigration can help relieve labour shortages, create businesses, spur aggregate demand and trade, and finance social protection and pension systems.

A recent study finds that labour migration has a positive, but limited, impact in the economies of developing countries (OECD/ILO, 2018). Immigrants’ contributions to the value added of production were estimated to be around 4% in Argentina, 11% in Costa Rica and 4% in Dominican Republic. These rates are above their population shares in the three countries. This implies that perceptions of possible negative effects of immigrants are unjustified. At the same time, it also means that most countries of destination do not sufficiently leverage the skills and expertise that immigrants bring. To maximise the positive impact of immigrants, policy makers should adapt migration policies to labour market needs and invest in immigrants’ integration.

The multidimensional nature of development challenges, and hence the need to adopt a “whole-of-government” approach when dealing with them, must also be reflected in the way international co-operation for development operates. Often, donor countries designate responsibility for international co-operation solely to development co-operation or foreign affairs ministries. Instead, national line ministries could oversee both domestic affairs in their area of responsibility as well as the international dimension to better reflect the inter-connection between the domestic and global agendas (Jenks, 2015). Under this logic, for example, ministries of environment would work together as peers on climate change mitigation or ministries of health would engage internationally on disease control and prevention issues.

South-South co-operation and Triangular Co-operation: One of the keys to support the rebalancing of modalities

Achieving the 2030 Agenda requires engaging in multiple forms of co-operation, whether multilateral, bilateral, South-South co-operation (SSC) or triangular co-operation (TrC). Triangular co-operation in particular is quickly increasing, given its potential to complement more traditional forms of co-operation. TrC has traditionally been an arrangement under which donors and international organisations support and complement specific SSC programmes or projects by providing technical, financial and material assistance. It usually involves a traditional donor from the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, an emerging donor from the South, and a beneficiary country in the South (Ashoff, 2010).

LAC is recognised as a leading region in the evolution of SSC4 since hosting the Buenos Aires Plan of Action (BAPA) conference 40 years ago, with a particular focus on intra-regional SCC. Of the 1 475 SSC exchanges involving Latin American countries in 2015, 976 were bilateral projects or actions between countries within that grouping, and a further 101 were regional SSC programmes or projects. There were 168 triangular exchanges in the region in that year. The number of initiatives has been broadly steady over the past few years, although the last year with data (2015) shows a significant rise in the number of long-term projects and a significant decline in the number of SSC actions (SEGIB, 2017).

Triangular co-operation has the potential of helping to rebalance the instruments and tools used in international co-operation. It can serve to increase the efficiency of traditional aid by creating synergies, increasing the value for money of development assistance and leveraging local knowledge (by, for example, experts from emerging donors instead of experts from traditional donors). It can also support improving the quality of SSC by involving traditional donors and sharing successful experiences. More importantly, if scaled up in terms of acquiring a more strategic and integrated policy focus, and in terms of increasing the number of modalities used in more regular and streamlined methods, then TrC can respond to domestic and global challenges by building stronger partnerships that promote win-win-win situations, in which all partners learn, contribute – in financial and non-financial ways – and share responsibilities.

Conclusions and proposed next steps

A call to action: Building the machinery of international co-operation as facilitator

The LAC region is fertile ground for rethinking how international co-operation can – and should – facilitate pathways to sustainable and inclusive development. Even in the face of certain development traps associated with productivity, social vulnerabilities, institutional capacity and environmental challenges, the LAC region simultaneously demonstrates a firm and mature resolve to address these roadblocks to its greater prosperity. The region is acting on this resolve in three interconnected ways. It is harnessing existing domestic strengths and development plans. It is engaging globally on mutually relevant development issues, including the achievement of the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals. It is also increasingly linking the domestic and international spheres to sustain development that will make a lasting difference in the lives of its citizens.