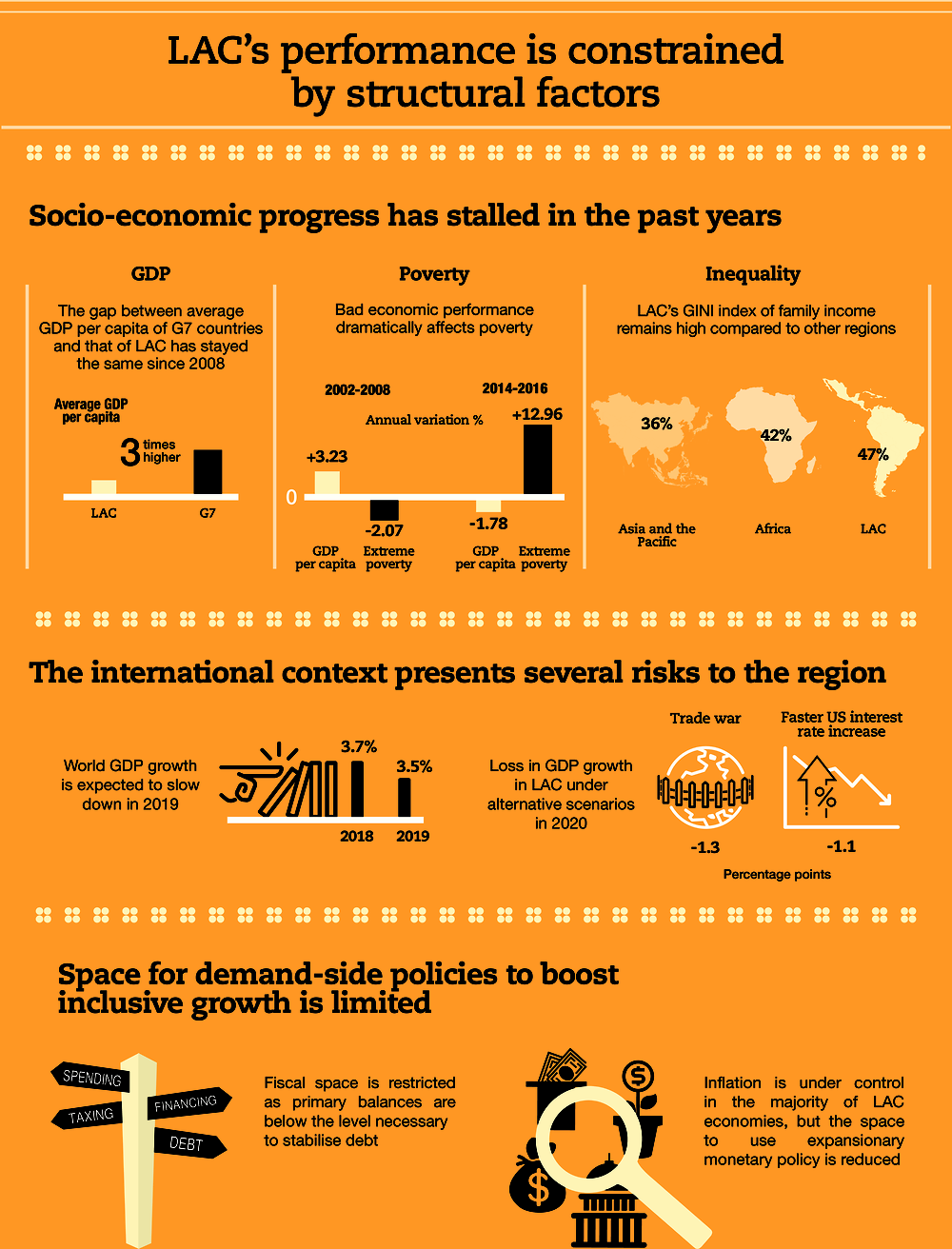

Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is experiencing a subdued recovery. Current growth rates are below the previous decade and will be insufficient to close the income gap with advanced economies. The general macroeconomic outlook still points to significant heterogeneity across countries. This highlights differences in exposure to external shocks, main trade partners, policy space and frameworks, and idiosyncratic supply shocks. The international context presents several risks for the region and current economic growth is insufficient to defend the socio-economic achievements of the last decade, with poverty and inequality reductions on hold. This socio-economic performance highlights both new and persistent structural challenges in the region. Low potential economic growth, persistent high inequality rates and increasing poverty levels are all symptoms of key development traps.

Latin American Economic Outlook 2019

Chapter 1. Socio-economic risks and challenges: A macro-perspective

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Introduction

The macroeconomic outlook in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) is expected to improve, but remains weak compared to the mid-2000s. Recovery stalled in 2018, as global and idiosyncratic shocks affected output in major economies in the region. Activity is expected to regain some momentum in 2019 and 2020, but growth performance would be subdued compared to the previous decade. The region is still characterised by an uneven performance, so it is still about “Americas Latinas” in terms of cyclical positions, exposure to external shocks and policy options.

The region will navigate under a complicated global context. In 2018, LAC economies benefited from a backdrop of improved commodity prices and solid global activity. However, for 2019 and 2020, a soft landing is expected in world gross domestic product (GDP) and trade growth. Furthermore, the risks of a more disruptive financial tightening and escalating trade tensions between key partners of the region – the United States and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) – may cloud the LAC regional outlook that continues its external adjustment.

As a result of low economic growth, prospects for socio-economic progress are dimmer, with the reduction of poverty and inequality on hold, with possible reversals. Since 2014, poor economic performance has been accompanied by poverty and extreme poverty increases in some countries. Projections for 2017 suggest no appreciable changes in this trend. Similarly, after strong decreases in inequality during the commodity boom, inequality has been stagnated since 2014 in the most unequal region in the world.

Sluggish progress in various socio-economic dimensions in LAC, coupled with a complicated external context, highlights ongoing and new structural challenges. Symptoms such as low economic growth, persistent inequality rates and rising citizen discontent suggest key development traps. These must be addressed by increasing domestic capabilities and rethinking development strategies and international co-operation.

This chapter is organised as follows. First, it presents the economic outlook for LAC, highlighting the heterogeneity in the region and the low space for demand policies. Second, it examines the global context, with a focus on key partners of the region, and the global financial and commodity markets. This section identifies the main external risks for Latin America, and their possible impact on regional GDP growth and balance of payments vulnerability. Third, it analyses recent trends on inequality and poverty reduction and their relationship with the economic cycle. The final section presents the main conclusions.

An insufficient economic recovery with limited policy space and low potential growth

Since the turn of the century, LAC has made socio-economic progress that includes a narrower income gap relative to most advanced economies, lower poverty and inequality, and a more stable macroeconomic environment. Nevertheless, the region has experienced low economic growth due to structural factors and a challenging external context in the past five years. This has led to stagnation in socio-economic improvements and some reversals.

Latin America is experiencing a modest economic recovery with low potential growth

Recovery in LAC will likely be subdued. Activity in LAC rebounded in 2017 following a substantial deceleration since 2011 that ended with a two-year contraction. However, negative surprises from two major economies, Argentina and Brazil, dragged regional output down. This, in turn, stalled recovery in 2018. The macroeconomic outlook in LAC is expected to improve, but remains weak compared to the mid-2000s. Activity is expected to regain some momentum in 2019 and 2020, but growth performance is likely to be subdued compared to the previous decade.

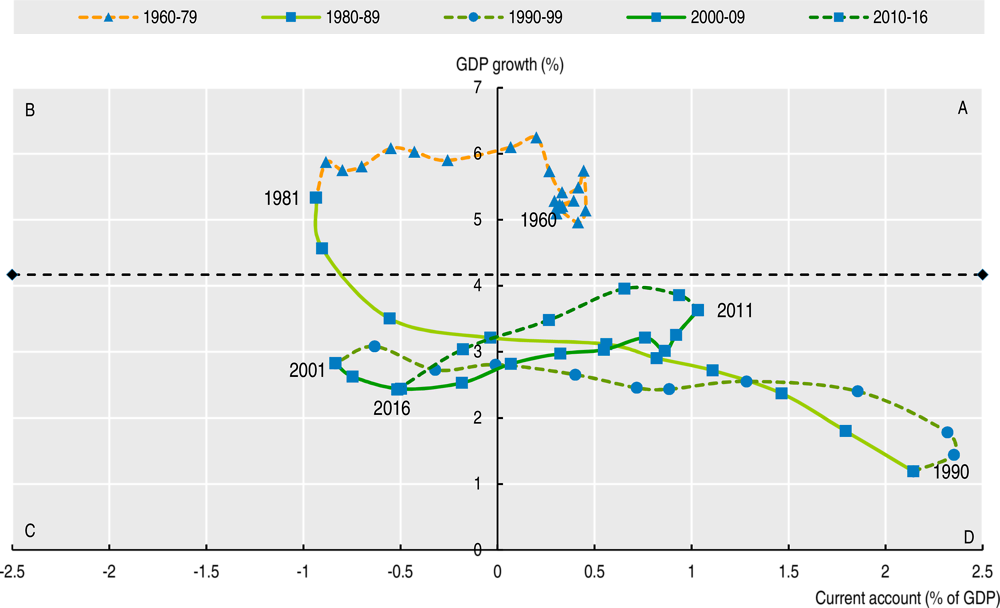

Since 2011, GDP growth in LAC has been below the high rates of the mid-2000s. High growth took place in a favourable global context and booming commodity prices during the mid-2000s. LAC´s average annual GDP growth rate reached 5.1% in 2004-07 (Figure 1.1, Panel A). South American economies experienced higher growth rates during the commodity boom. Those countries grew at an average annual rate of 6.3% between 2004-07. None of them grew less than 2.1% in any year of that period. The Caribbean and Central American economies and Mexico also grew at a fast pace, boosted by the United States. Over 2004-07, on average annual growth in the Caribbean countries was 4.1%, while in Central America and Mexico it was 5.3%.1 Countries such as Antigua and Barbuda, Dominican Republic, Panama, and Trinidad and Tobago stood out owing to their high growth rates.

Figure 1.1. Latin America and the Caribbean: Growth and income gap

Note: Simple averages.

Source: ECLAC (2017a), CEPALSTAT (database), IMF (2018) and World Bank (2018a).

Current growth is insufficient to close the income gap relative to the most advanced economies. In 2000, average GDP per capita2 of the G7 countries was 3.5 times larger than the average of the region. In 2008, the gap had decreased to 3.1. Over the same period, GDP per capita of G7 countries relative to that of Central America and Mexico fell from 5.1 to 4.6 and from 3.6 to 3.2 in the case of South America. Since 2011 the gap has declined in Central America and Mexico and, in the case of South America and the Caribbean, has recorded a slight increase (Figure 1.1, Panel B).

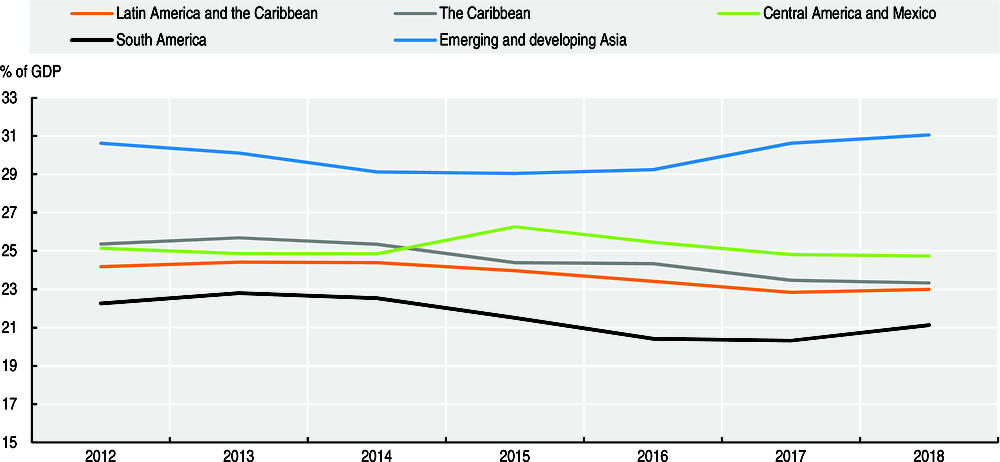

Potential output has slowed since 2011 across the board and is lower than expected. Medium-term growth projections suggest that potential output in Latin America is less robust than previously thought. Evidence indicates that potential growth is 3% – lower than expected. This stands in sharp contrast to the 5% average annual growth rate that characterised the mid-2000s, as highlighted in previous editions of the Latin American Economic Outlook. Low potential growth is a matter of concern for the region’s macroeconomic and social effects, which are related to slow job creation and lingering unemployment. Investment rates tend to fall in tandem with growth as has been the case in the three sub-regions since the 2011 slowdown. This, in turn, complicates structural change and thus export performance. On average in LAC, investment fell to 23.0% of GDP in 2018, a drop of 1.2 percentage points from 2012. This represented almost 10 percentage points difference with emerging and developing Asia (IMF, 2018), although with strong variation among sub-regions (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Total investment

(Percentage of GDP)

Heterogeneity persists across the region

The macroeconomic outlook still points to different “Americas Latinas”, with significant heterogeneity across countries. This highlights differences in exposure to external shocks, main trade partners, differences in policy frameworks and idiosyncratic supply shocks.

Argentina, Nicaragua and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (hereafter “Venezuela”) are estimated to contract in 2018. Argentina was hit by a currency crisis in the second quarter of 2018 and the combination of massive fiscal and monetary tightening will keep the economy in recession during 2018 and 2019 (OECD, 2018). The widening of the current account deficit, the real exchange rate misalignment and the gradual approach to fiscal consolidation rapidly increased external debt accumulation in the previous years. This growing debt played against the economy in the midst of global financial turmoil. Peso depreciation weighed on activity by deteriorating expectation, holding investment and consumption back, and by pushing inflation up and reducing real incomes. Given the negative impact of the drought on agriculture, the economy contracted in 2018. Growth is expected to resume in 2020, but below previous expectations as fiscal consolidations and tight monetary policy weigh on spending. In the case of Nicaragua, output is projected to contract in 2018 and 2019 owing mainly to social and political unrest. Finally, Venezuela is expected to remain in recession in both 2018 and 2019, afflicted by hyperinflation, high fiscal deficit and increasing public debt.

Growth has remained resilient in a group of economies, but still below 3.0%. In Brazil, external vulnerabilities are modest – a low current account deficit (1.3% of GDP), ample reserves (18% of GDP) and a low fraction of external public debt (5%). However, the Brazilian real tumbled against the US dollar during the market turmoil, as the large fiscal imbalance and incomplete fiscal consolidation process catalysed market concerns. With inflation well below the target, the central bank did not tighten monetary policy in the midst of the turmoil. The truck drivers’ strike further dented activity, marking the weaker than expected performance in 2018. Activity is expected to recover in 2019 and 2020 supported by improvements in the labour market, but the new administration must design a pension reform to recover sustainability (OECD, 2018). Activity in Mexico remained resilient, despite uncertainty surrounding presidential elections and the North American Free Trade Agreement; it strengthened among Central American economies. Growth is expected to remain relatively stable in 2019 and 2020. As an uptick in growth in 2017 was hard to sustain, economic growth in Ecuador will soften as fiscal consolidation progresses over the next years.

In economies such as Chile, Colombia, Peru and to some extent the Plurinational State of Bolivia (hereafter “Bolivia”), GDP growth gathered momentum compared to 2017. On the back of solid consumption, stronger investment and the recovery of commodity prices, output growth is expected to remain relatively solid in 2019 and 2020.

Fast-paced growth is likely to continue in the Dominican Republic and Panama, the two countries in the region growing the most. Growth is based on services (trade and financial) in Panama and on infrastructure development in the Dominican Republic.

The Caribbean countries could face some challenges as interest rates increase and the US dollar appreciates. Barbados’ new government is undergoing a fiscal adjustment programme to avert a twin crisis, which should weigh on activity. Most countries maintain negative output gaps, which are expected to continue closing in the years ahead. Despite some heterogeneity across countries, the Caribbean is among the world’s most indebted sub-regions. As a result, the high cost of its debt service has greatly reduced countries’ fiscal space (see Chapter 6).

There is low or non-existent policy space across countries to boost inclusive growth

Under the current slowdown, there is reduced space for demand-side policies in Latin America. In many cases, the space for both fiscal policy and monetary policy is either relatively low or non-existent. Nevertheless, different growth performance and distinct policy frameworks also imply significant differences across the region in terms of policy space.

The little space for monetary easing is ending in countries where output gaps are closing and inflation bottoming. Central banks are likely to start increasing rates in 2019, particularly in the face of further currency depreciation affecting expectations and second-round effects on the price-setting process. This is the case in Brazil and other South American economies. In Mexico, where inflation is still above target, monetary policy is still tight. However, inflation expectations and core inflation remain stable and within the central bank’s band (OECD, 2018). Currency depreciation may delay the move towards a neutral stance. In Argentina, adjustments in regulated prices, supply shocks and, most importantly, the sharp currency depreciation in the second and third quarters of 2018 derailed expectations. These factors fuelled inflation levels well beyond the already adjusted target of the central bank. This highlights that the pass-through is probably still large in Argentina; expectations are not yet solidly anchored to targets.

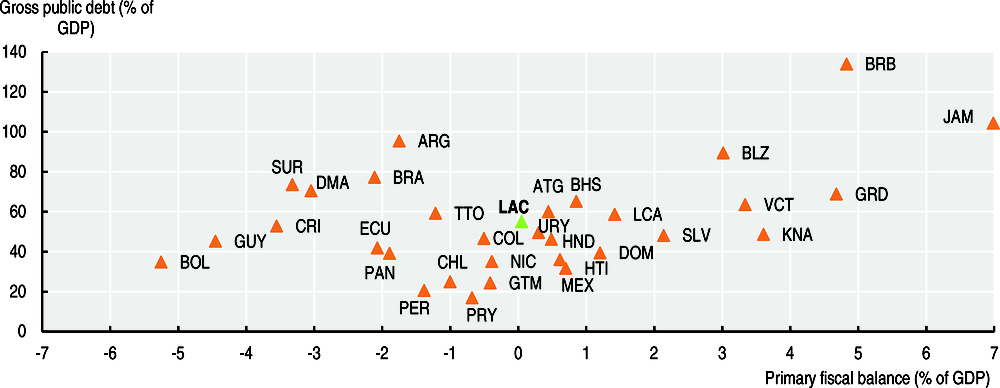

Fiscal space remains restricted as primary balances remain below the level necessary to stabilise debt. The average deficit diminished in 2017, but debt levels continued to increase as imbalances remained quite substantial in some major economies. Performance was uneven across countries, highlighting different cyclical positions and advances in fiscal consolidation reforms (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. Gross public debt and primary fiscal balance in selected Latin American and Caribbean countries

(Central government, percentage of GDP in 2016)

Note: LAC is a simple average for the 17 economies used. For Mexico, primary balance refers to non-financial public sector, for Peru to general government. For Ecuador, this is net debt (with the private sector), while in Argentina it is gross debt. For Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados, both figures refer to general government.

Source: ECLAC (2018a), Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2017: Public Policy Challenges in the Framework of the 2030 Agenda; and IMF (2018), World Economic Outlook (database).

There was some progress regarding fiscal consolidation in the region. A part of the consolidation resulted from cyclical improvement in revenues and higher commodity prices. Another part is related to spending cuts (e.g. in Chile, Ecuador and Mexico). Highly indebted countries with elevated tax pressures (Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay) are trying to stabilise debt mainly through spending cuts, as indicated in previous editions of the Latin American Economic Outlook (OECD/ECLAC/CAF, 2018). Pension reform in Brazil will be crucial to regain fiscal sustainability. Countries must also focus on efficiency of spending to guarantee and improve public goods. The path towards debt stabilisation and deficit reduction should continue in Chile, Colombia and Peru. Chile and Peru have more space to deviate from the path without derailing sustainability. With its more limited fiscal scope, Colombia passed a financing law at the end of 2018, but further efforts are needed to stabilise debt and finance its ambitious national development plan.

The international context presents several risks to the region

Main external conditions affecting the region

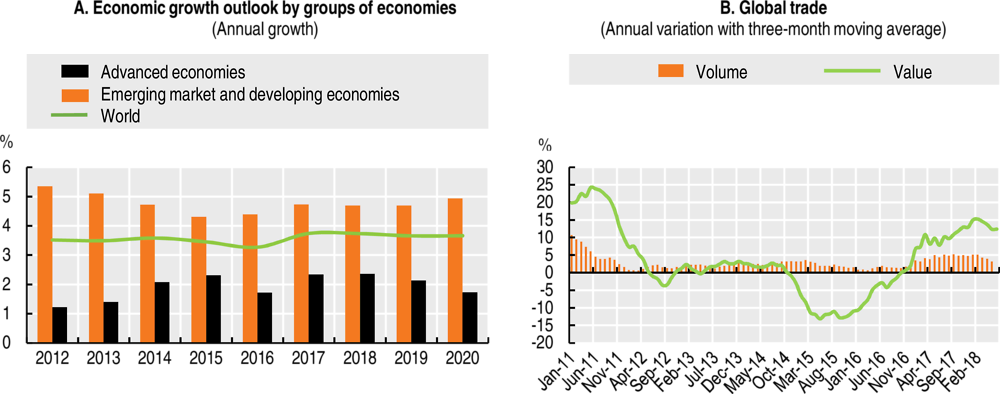

In 2018, LAC economies benefited from a still solid global activity, but for 2019 and 2020 a soft landing is expected. World GDP growth is expected to remain around 3.7% in 2018, before decreasing to around 3.5% in 2019 and 2020 (Figure 1.4, Panel A). This is broadly in line with underlying global potential output growth (IMF, 2018; OECD, 2018). The strong rebound in global trade, still favourable financial conditions and the recovery of commodity prices that supported growth in 2017 began slowing early in 2018. Mounting trade tensions, geopolitical conflicts and rising borrowing costs curbed the appetite for risk. This, in turn, sparked financial volatility and hit growth prospects, particularly in emerging economies with weaker fundamentals.

Figure 1.4. Economic growth outlook and global trade

Source: IMF (2018), World Economic Outlook, July www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/update/01/pdf/0118.pdf; and CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Analysis (2018), World Trade Monitor (database), www.cpb.nl/en/worldtrademonitor.

Among LAC’s main partners, activity is becoming less synchronised. Economic growth in the United States accelerated in 2018 owing to fiscal stimulus and the strength of the labour market, with the unemployment rate below 4% (OECD, 2018). Activity is expected to slow down in 2019 and 2020, as the fiscal stimulus wanes. Conversely, activity in the Euro Area softened in 2018. For 2019 and 2020, the growth pace will still be moderate (OECD, 2018). Domestic demand will be supported by an accommodative monetary policy and fiscal easing, and strong investment that reflects favourable financing conditions. In the case of China, as exports and investment ease, the ongoing structural deceleration continues (OECD, 2018). For the Asian economy, headwinds started to cloud the outlook in 2018. Trade tensions dampened expectations about the economy, promoting capital outflows and weakening the currency.

Global trade is expected to slow down mildly in 2018 and 2019. Following a rebound in 2017, global trade slowed in 2018. It will continue to soften in 2019, but no major collapse is expected (Figure 1.4, Panel B) (IMF, 2018; OECD, 2018). The effects of the first tariffs introduced by the United States and some of its key partners on global trade have been modest, since measures involved a small fraction of global trade. The United States imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium, washing machines and solar panels, and on imports from China. China retaliated with similar tariffs. However, these actions account merely for 0.89% of global trade and 0.20% of global GDP (Capital Economics, 2018). Even including proposed tariffs – the additional USD 200 billion worth of imports from China – the trade actions would total less than 5% of global trade and about 1% of world GDP (Capital Economics, 2018). In this scenario, GDP growth could register cumulative drops of 0.3% and 0.4% by 2020 in the United States and in China, respectively (Oxford Economics, 2018). Nevertheless, the chances of a larger escalation of tensions increased as negotiations between the two parties broke down. This could cost China up to 1% of GDP growth by 2020 (Oxford Economics, 2018).

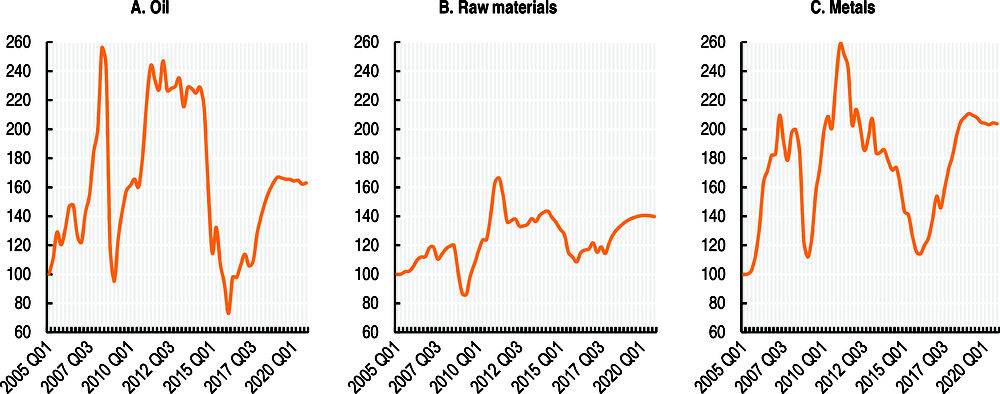

Commodity prices are expected to ease. Leaving behind the slump between 2014 and 2016, commodity prices continued to recover in 2018. Geopolitical tensions boosted oil prices in the first half of 2018. However, fears that a trade war and tighter credit conditions would hit the Chinese economy curbed the uptrend. The baseline scenario for commodity markets is of a slight moderation in prices as the cycle matures and global demand loses some steam (Figure 1.5). There are upside risks for oil prices due to possible supply shortages (IEA, 2018). These shocks, however, should be relatively transitory, particularly as global demand moderates. Metal prices also gained ground in 2018 on the back of strong demand, but are expected to ease over the next two years. The sharper slowdown in investment in China and mounting trade tensions with the United States pose downside risks to this outlook, as China is a key player in this market (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2015; World Bank, 2018a). In the case of agricultural commodities, prices are expected to remain relatively stable in the next two years.

Figure 1.5. Commodity prices outlook (2005 = 100)

Financial markets go back to risk-off mode and capital flows to emerging economies recede. Global liquidity tightened in 2018. Rising interest rates in the United States and its comparatively stronger growth performance increased the attractiveness of US assets. The combination of monetary tightening (rising interest rates) and fiscal expansion pressed bond yields up (particularly five- and ten-year bonds), contributing to dollar appreciation. Risks are tilted towards a sharper rate increase if core inflation further accelerates. Against this backdrop, uncertainty stemming from increased trade and geopolitical tensions catalysed a comeback of risk aversion. The unwinding of risky positions translated into asset price oscillations not seen since the Taper Tantrum in mid-2013, marking the return of volatility to financial markets. Capital flows to emerging markets receded, widening sovereign bond spreads, depreciating currencies against the US dollar and sinking stock market values.

Following a recovery in 2017, emerging markets reported net portfolio outflows from non-residents in the first two quarters of 2018. In the first six months of 2018, total portfolio inflows to emerging markets plunged from USD 110 billion to merely USD 46 billion during the same period in 2017 (Figure 1.6, Panel A). Reversals in capital inflows affected emerging markets across the board as an asset class, but countries with larger imbalances or more exposed to US trade policy were hit harder (IIF, 2018). Moreover, reversal episodes of portfolio inflows have become more frequent and intense since late 2017 (Figure 1.6, Panel B). Debt accumulation by non-financial corporates is a key source of vulnerability in emerging economies (Box 1.1).

Figure 1.6. Financial volatility and capital flows to emerging markets

Note: Panel A USD billion. Panel B Daily USD billion.

Source: IIF (2018) and World Bank (2018b).

Box 1.1. Debt accumulation by non-financial corporates, a potential risk

A potential vulnerability in emerging economies is debt accumulation by non-financial corporates. Over the extended period of ample liquidity and low interest rates in global markets between 2009 and 2019, total debt in emerging markets increased by 55% of GDP (IIF, 2018). Nearly half of that change (23.3% of GDP) corresponded to non-financial corporate issuance. The rest is split between the financial sector, households and governments. While governments and financials largely resorted to domestic currency debt, corporates issued more foreign exchange (FX) liabilities. This made corporates more vulnerable to increases in borrowing costs and US dollar appreciation. On average, about a third of total corporate debt is denominated in foreign currency. There is, of course, ample heterogeneity across countries (Figure 1.7, Panel A). China and Turkey recorded the largest increases in debt, followed by Singapore and Chile. In China and Turkey, new issuances were mostly domestic, while corporates in Singapore, Indonesia and Chile increased issuance in foreign currency, mostly in US dollars. In Latin America, Colombian, Brazilian and Mexican corporates also expanded FX debt, but to a lesser extent than Chile. Moreover, emerging markets continued to issue international bonds at a strong pace in 2018, in spite of market jitters (Figure 1.7, Panel B).

Figure 1.7. Non-financial corporate debt in emerging economies

In the case of Latin American countries, there is limited information regarding the coverage or nature of the corporate FX issuance (Powell, 2017). Corporates possibly have some form of coverage (natural for exporters and FX derivatives). This reduces currency- related balance sheet risks, but not the exposure to higher borrowing costs and tighter liquidity. Swings in capital inflows to developing countries are not atypical in the face of interest rate hikes in developed economies, as has been extensively documented in the literature (Calvo, Leiderman and Reinhart, 1996; Reinhart, 2005). As advanced economies continue to normalise monetary policy, such episodes are likely to continue.

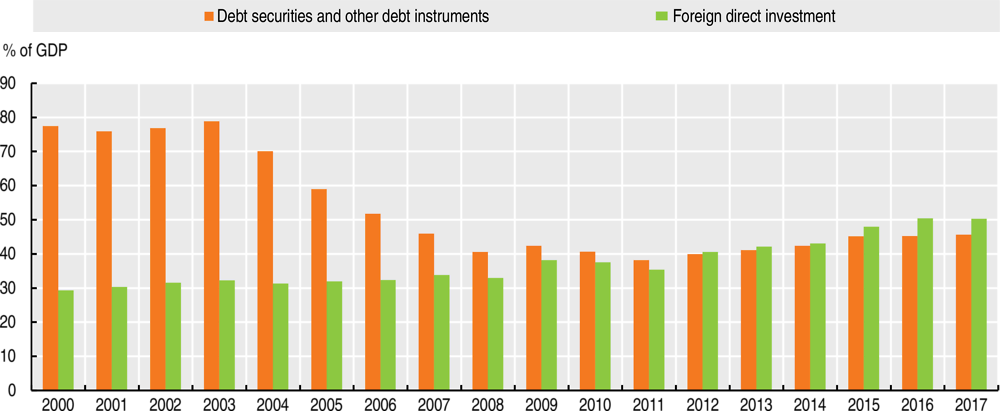

Since 2011, foreign liabilities in Latin America have increased, although they are still below foreign direct investment (FDI) (Figure 1.8). The increase in foreign indebtedness in the region has, as a result, expanded the size of interest outflows as recorded in the current account of the balance of payments. Interest outflows increased from 0.6% of GDP to 1.2% over 2008-17. By contrast, profit remittances have decreased on average since 2012 in a context of slowdown in growth and a fall in terms of trade. This trend was clearer in South American countries, which are more dependent on primary goods exports. On the other hand, some Central American countries recorded an increase in direct investment income outflows in the last years.

Figure 1.8. Foreign liabilities in LAC, debt versus FDI

(Percentage of GDP)

Note: Simple average that includes Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Uruguay.

Source: IMF (2018).

Current external risks could derail the recovery in LAC

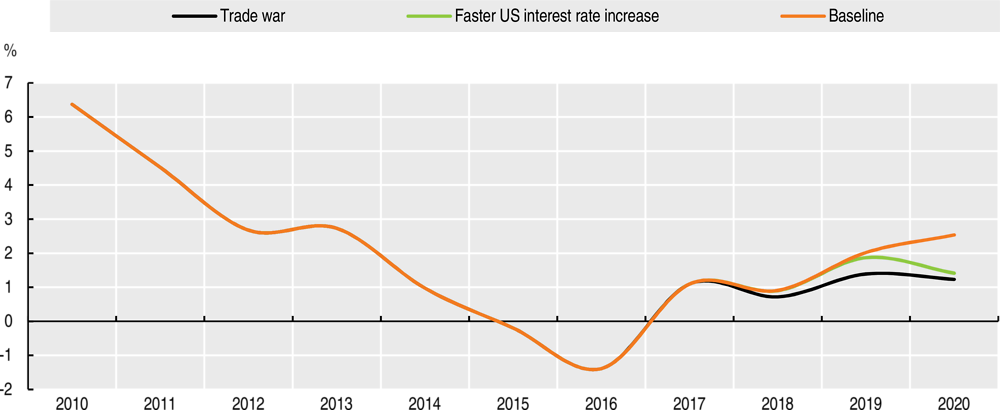

LAC is expected to overcome its lacklustre performance in 2018 over the next two years, converging to growth rates between 2% and 3%. There are several main risks to this outlook. First, global financial tightening could be faster and more disruptive than expected. Second, the escalation of trade tensions between the United States and China could affect global growth.

A faster and deeper tightening in monetary policy in the United States and the end of quantitative easing in the euro area could intensify the reversal of capital inflows to LAC countries. This is especially relevant for countries that partially rely on portfolio flows to finance large current account deficits, such as Argentina and some Central American and Caribbean countries. It could also have implications for fiscal sustainability in some highly indebted countries in the Caribbean with a large fraction of foreign currency debt. Market jitters in 2018 are indicative of what may happen as financial conditions continue to tighten.

The risk of a fully-fledged trade war between China and the United States is no longer negligible. A decline in activity in China and the United States resulting from trade disruptions would affect LAC economies in several ways. These include sizable spillovers on global demand, lower commodity prices, a decline in FDI, and efficiency losses due to output reallocation (Kose et al., 2017). However, exposure to demand from the two parties is uneven in the region. Cycles in Mexico and Central American countries exhibit larger co-movements with the US cycle than South American countries, which have become more exposed to China (Izquierdo and Talvi, 2011).

Two scenarios are modelled to illustrate the possible impact of these risks. Under the first scenario, a surge in US inflation prompts the Federal Reserve System to accelerate interest rate adjustment. This would induce a retrenchment of global liquidity, higher borrowing costs and volatility. Growth is hit in all countries, but impacts are more significant in those with larger external borrowing needs. A second scenario of trade tensions between China and the United States, where USD 250 billion of goods are affected, would have negative implications for growth in both nations. This would affect the region via a weakening of global demand and lower commodity prices. This is the most deleterious scenario for the region, deducting around 2.0 percentage points of GDP growth accumulated between 2018 and 2020 (Figure 1.9).3

Figure 1.9. GDP growth in Latin American economies with alternative scenarios

(Annual percentage rate)

Notes: Weighted average for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. Interest rate increase scenario contemplates an additional and cumulative 0.25 basis points (bp) rise on short-term interest rates in the United States compared to the baseline (interest rates plateaued after 2019). This implies a cumulative rise of 200 bp by 2020, compared to the baseline scenario. Trade war scenario is modelled on Oxford Economics projections for the impact on US GDP and China GDP of tariffs on USD 250 billion (25% for 50 billion and 10% for 200 billion) of Chinese exports to the US with a similar response from China. Between 2018 and 2020, GDP would decline 0.37 bp in China and 0.26 bp in the United States with respect to the baseline.

Source: Own calculations based on a Global Bayesian Vector Autoregression model.

External adjustment is still ongoing in LAC

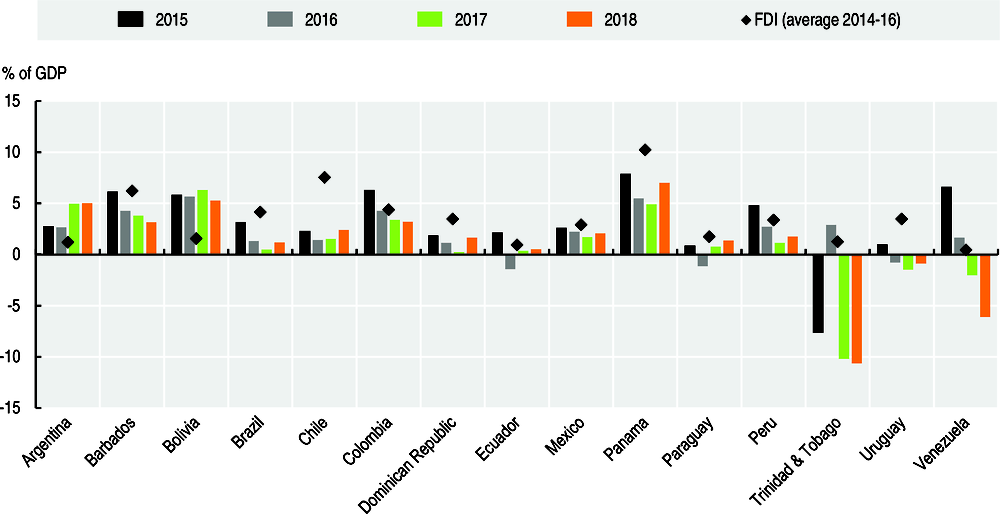

Current account deficits keep narrowing and are still mainly financed by FDI in most countries (Figure 1.10). Stronger domestic demand in some countries and commodity price stabilisation may slightly increase current account deficits in 2019 and 2020, without necessarily undermining external sustainability. FDI inflows to LAC have subsided since 2014. They will likely continue to recede over the next two years and remain uneven at a country level (ECLAC, 2018b). However, levels of FDI inflows will be enough to finance external deficits in most countries, except for Argentina, Bolivia and some Caribbean countries. Flexible exchange rates contributed to the adjustment of external accounts (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.10. Current account deficits and foreign direct investment

(Percentage of GDP)

Box 1.2. Flexible exchange rates and balance of payments adjustments

Flexible exchange rates contributed to the adjustment of external accounts. These acted as a cushion against negative external shocks, particularly following the decline of commodity prices after 2014. Real depreciation led to a compression in imports, expenditure switching towards local goods and, more recently, to a moderate expansion in exports. Initial lacklustre export dynamics reflected a weaker currency depreciation in real effective terms than the one depicted by depreciation against the US dollar, in a context of subdued global trade growth (Powell, 2017). Since 2017, however, exports contributed to the narrowing of current account deficits, additionally supported by stronger global trade and higher commodity prices.

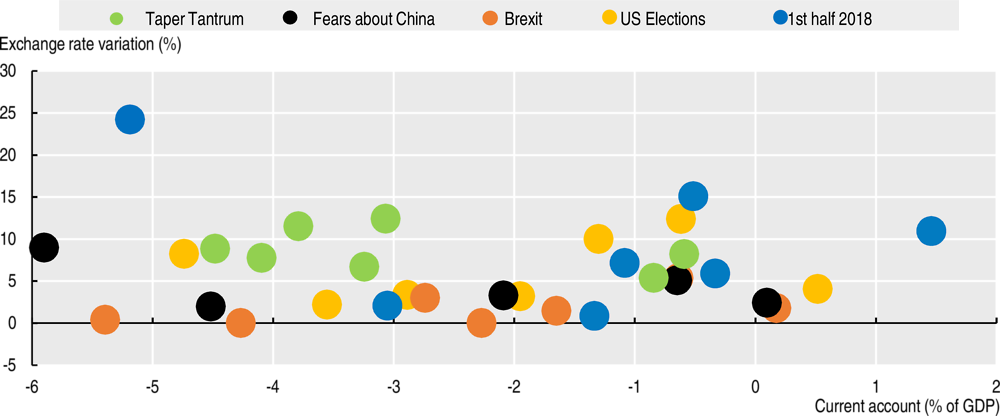

Exchange rates slid once more in 2018 as higher borrowing costs and the retrenchment of the appetite for risk reduced the attractiveness of Latin American assets across the board (Figure 1.11). In previous volatility episodes, there was no apparent discrimination among markets. In this case, however, currency losses were more severe in countries with weaker fundamentals and higher exposures to certain external developments. Argentina, for example, suffered a currency crisis as markets lost confidence in the face of ample twin deficits; a significant dependence on debt portfolio flows to finance them; currency misalignment; and low FX reserves. Even after the IMF agreements, investors remained nervous and the peso took another blow in mid-August, followed by another agreement. Depreciation of the Brazilian real largely stemmed from political risk, but also from the non-abating fiscal imbalance, in spite of no relevant external vulnerability.

Figure 1.11. Current account balance, exchange rate variations and financial volatility episodes

Balance of payments vulnerability has intensified in recent years. The growing exposure to international markets helps explain both higher volatility and lower growth. On the real side, low diversification of exports, especially in South American countries, has increased exposure to changes in international commodity prices. Similarly, in the face of a challenging global trading context, LAC regional integration remains an underexploited opportunity. Only 16% of total LAC exports were destined for the regional market in 2015. This is well below the intra-regional trade coefficients of the world’s three major “factories”: European Union (63.2%), NAFTA (49.3%), ASEAN+54 (47%) (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018). On the financial side, mounting external leverage, in particular from non-financial corporate firms, has increased. exposure to the international liquidity cycle.

Income elasticity of exports varied across sub-regions in Latin America. Given the pace of growth of trade partners, economic growth consistent with long-term external equilibrium depends on the ratio between a country’s export and import elasticities. Except for Paraguay, the ratio between those elasticities fell significantly in South American countries in recent years, largely because of decreases in the income elasticity of exports (ECLAC, 2017). South America’s export volume rose by a mere 1.9% between 2014 and 2018, compared with a growth of 6.4% between 2004 and 2008. The slowdown of exports was therefore caused not only by the stagnation in international trade, but also by a structural decline. By contrast, income elasticity of exports tended to increase in Central America and Mexico (ECLAC, 2017). Those countries’ exports grew at an annual rate of 3.5% between 2014 and 2018. This rate was slightly better than in South American and Caribbean countries and higher than the GDP growth of 2.4% in the United States, the main trading partner of Central America and Mexico. The dynamics of foreign trade reveal the persistence of structural problems – pervasive technology gaps, undiversified specialisation patterns, low productivity growth – which affect systemic competitiveness and undermine growth (Box 1.3). In particular, since the beginning of the 21st century, the trend has been towards less diversification in LAC’s exports.

Box 1.3. Latin America: Capabilities, productive structure and external constraint

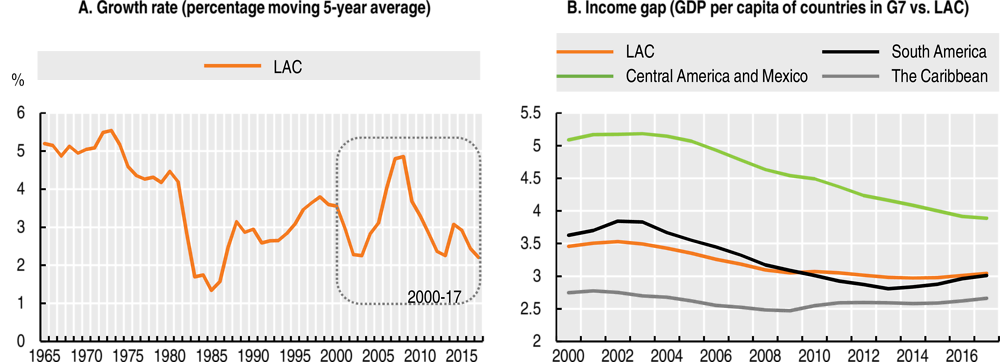

The coevolution between capacities, productive structure and external constraint requires viewing growth through the lens of trade, and thus moving beyond analysis of short-term fluctuations. Figure 1.12 shows the growth rate of Latin America on the ordinate axis and its trade balance on the abscissa axis, from 1960 to 2016. The identified subperiods are associated with different phases in trade and international finance.

Figure 1.12. Latin America: Phases of external constraint and economic growth, 1960-2016

Quadrants A and C correspond to results in the trade balance that are unsustainable in the medium term, while quadrants B and D indicate sustainable positions (i.e. a positive trade balance). The countries moving through quadrants A and C are adjusting or should adjust soon to avoid over-indebtedness. These countries have been financed from abroad for some time. However, as in Argentina, they show great vulnerability to changes in expectations or in the liquidity of financial markets.

The 1960s were a period of high and sustainable growth. Expanding world trade helped the peripheral economies to overcome the external constraint, in association with import substitution policies. In the second half of the 1970s, most countries in the region borrowed significantly. Despite the global recession during this period, Latin America’s economy grew at high rates at the cost of accumulating high trade deficits. After the remarkable increase in interest rates in the United States in 1979, the debt became unpayable, which generated a strong adjustment process between 1981 and 1990. In these adjustment years, positive trade balances serviced the debt, while investment and growth rates plummeted. The Brady Plan and the return of capital in the 1990s implied relief from the external restriction and opened space for a new phase of growth. Low interest rates in the developed world led to a phase of liquidity and capital flow to emerging countries. In the peripheral economies, this phase combined with exchange rate appreciation policies, often as part of stabilisation programmes that responded to the high inflation that prevailed in the 1980s. The consequent loss of competitiveness alongside the stimulus to indebtedness led to new crises by the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s in some countries. This closed the second cycle of appreciation, indebtedness, crisis and adjustment.

By 2003, the pattern of boom (and bust) in natural resources observed between the 1970s and the 2000s had ended. The dynamism of demand for commodity premiums allowed increases in the volumes and prices of shipments. This, in turn, led to compatibility between higher growth rates and external surpluses. The 2008 crisis provoked a temporary decline in this positive trend, but exports continued to expand until 2012. Since then, international trade has slowed, and the region’s export performance suffers, especially for exporters of raw materials. The outlook is more favourable for Mexico and the countries of Central America, which export manufactures to the United States. They have recovered from the crisis more rapidly than other advanced economies.

Two structural factors explain the growth rates of the region, which have been low and volatile since 1980. First, low diversification of the productive structure and the increase in the technological gap have slowed the dynamism of exports and increased the external constraint in the long term. In fact, regional exports have increasingly focused on natural resources and manufactures with low local value-added. Second, the absence of macroprudential policies – including control measures on short-term capital inflows – increased vulnerability to liquidity cycles and lowered expectations in international markets.

Vulnerable economic performance affects social dimensions

Insufficient economic growth holds back poverty reduction

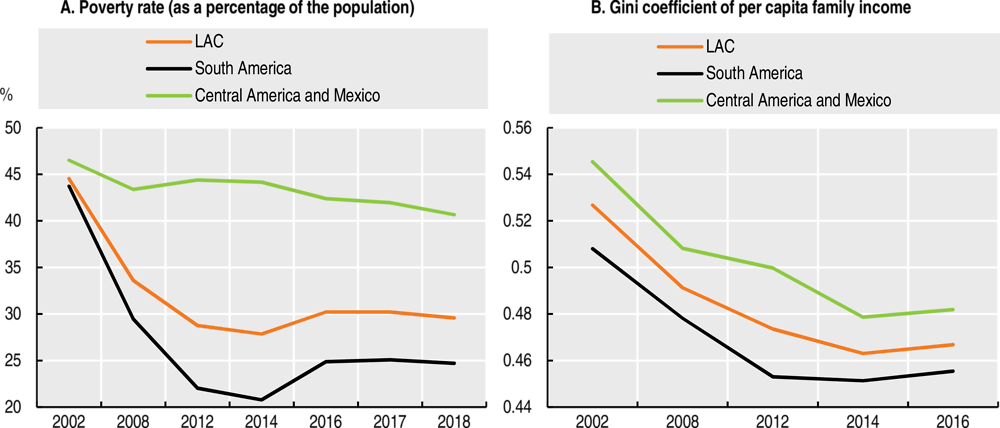

Since 2014, poor economic performance has been accompanied by poverty and extreme poverty increases, with wide heterogeneity across countries. Poverty reduction is strongly related to the economic cycle (Box 1.4). In light of the recent economic slowdown, the regional poverty rate climbed by 1.2 percentage points in 2015 and a further 1.1 points in 2016; it remained constant in 2017 and decreased by only 0.6 points in 2018. This meant a total increase of 18 million people living in poverty since 2015. Thus, 186 million people lived below the national poverty line in LAC in 2018, or 29.6% of the population. Extreme poverty also increased by 0.9 percentage points in 2015, 1.3 points in 2016 and 0.3 points in 2017, while it has remained constant in 2018. This represented an additional 17 million people in extreme poverty in those four years, adding up to 63 million people, or 10% of the population.

Figure 1.13. Poverty and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean

Note: Circa years for the Gini coefficient.

Source: ECLAC (2018c) and ECLAC (2017a), CEPALSTAT (database).

Box 1.4. Poverty and the business cycle

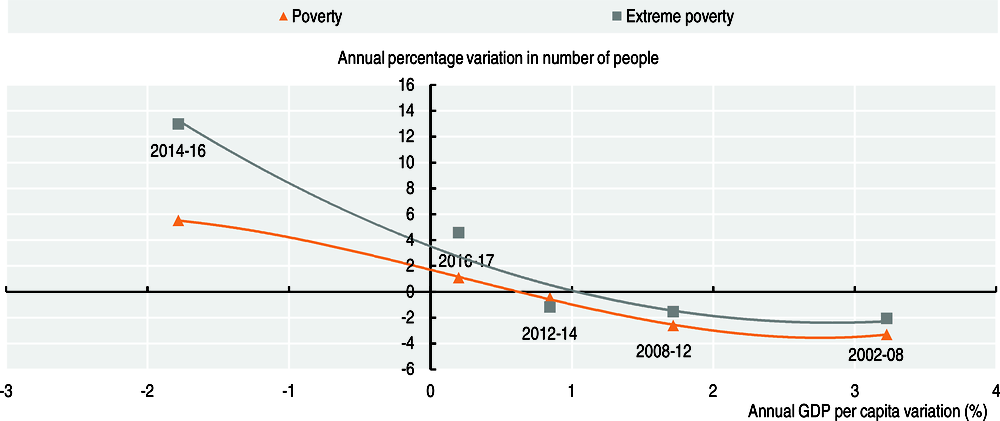

Poverty has been linked to the business cycle during the past 15 years. During 2002-08, as per capita GDP grew by 3.2% per year, the number of people in poverty fell at an average annual rate of 3.5%. At the same time, extreme poverty decreased by 2.9% per year. The 2008-14 business cycle downswing phase can be analysed in two sub-periods. In the first, up to 2012, per capita GDP grew at an average rate of 1.7% (half of the rate recorded between 2002 and 2008). In the second, between 2012 and 2014, growth was 0.8% per year (half of the rate corresponding to 2008-12). In the first sub-period, the number of people living in poverty decreased by 2.6% per year, while the number in extreme poverty declined by 2% annually. Between 2012 and 2014, the number of people living in poverty and extreme poverty decreased at annual rates of just 0.2% and 0.4%, respectively. Recently, in 2015 and 2016, the region’s per capita GDP contracted by 1.8% each year, while the proportion of people living in poverty and extreme poverty grew by 5% and 12%, respectively (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.14. Variation in the number of people living in poverty and extreme poverty, and variation in per capita GDP, 2002-17

(Annual equivalent percentage rates)

Note: Weighted average for the following countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Source: ECLAC (2018c), on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG) and CEPALSTAT database.

Other factors can also have an effect on poverty. Households obtain income from various sources, mainly paid work; ownership of assets and transfers from social protection systems; and transfers from other households. Thus, factors such as labour market structure and its policies, the provision of public services, social protection systems and poverty-reduction policies, the tax system and public expenditure policy, among many others, directly affect the level and distribution of household income. Consequently, these factors determine the extent to which economic growth can generate better living conditions for the population. In fact, levels or variations in GDP generate different levels and variations in household income. This effect is due to the various institutional and public policy conditions prevailing in each country of the region. In some countries, household income represents more than 60% of GDP, while in others it is equivalent to 40% or less. Moreover, the annual variations in per capita GDP (in constant dollars) and household income (expressed in real terms) is similarly heterogeneous (ECLAC, 2018c).

While the aggregate regional poverty level has risen, this is not the case for many countries in the region. The regional trends of poverty and extreme poverty are particularly influenced by the economic performance of three countries of considerable size for the region, Brazil, Mexico and Venezuela, as well as poverty increases in Ecuador, El Salvador and Paraguay. The rise in projected poverty in these countries outweighs the reduction in the rest of the region, especially in Argentina, Chile and Colombia where poverty fell the most between 2016 and 2018 (ECLAC, 2018c)

This stagnation in poverty reduction comes after a decade of sharp drops in poverty and extreme poverty. The incidence of poverty measured fell from 45.9% to 34.1% in 2002-08 and reached 27.8% in 2014 (ECLAC, 2018c). The decline in poverty was sharper in South American countries where the poverty rate halved between 2002-14 (Figure 1.12, Panel A). In Central America and Mexico, the reduction was not as significant as in South America and improvement occurred mostly in 2002-08, when the poverty rate declined from 46.5% to 43.4%.

The reduction in poverty rates was closely linked to labour market dynamics. In several LAC countries, improvements in labour income were the main factor behind the fall in poverty during the pre-crisis period (Beccaria et al., 2013). Although the results vary from one country to the next, between 30% and 70% of those who escaped poverty did so on the back of employment-related developments alone (new jobs or wage increases). The second reason for the decline in poverty was the combination of employment-related developments and non-work events (in the domain of social protection). Together, these developments and events accounted for between 60% and 80% of the total number who escaped poverty.

Inequality remains a key challenge with a predominant vulnerable class

Income inequality recorded an unprecedented drop but remains high. Between 2002 and 2014, the average Gini coefficient fell from 0.53 to 0.47 (Figure 1.13, Panel B). Meanwhile, the income of the richest 20% in LAC was 19 times greater in 2002 than that of the poorest 20%; in 2014, it was 11 times higher. Like poverty reduction, income inequality has stagnated since then. The average Gini coefficient of the region was 0.46 in 2017, and the vulnerable middle class represents the largest socio-economic group in the region (see Chapter 3).

Most equality improvements are due to labour market conditions derived from economic growth and lower informality, and complemented by social protection policies. Improvements in distributive dynamics have been closely related to the strengthening of labour institutions and the introduction of new tools (e.g. conditional transfers). Economic buoyancy and the re-emergence of key labour institutions in several LAC economies such as minimum wages, collective bargaining and vocational training policies led to rapid job creation and improved employment quality. Social policy saw improvements in social protection systems, especially income transfers targeting the most disadvantaged sectors of the population (Martínez, 2017). Notwithstanding progress in social protection, improvements in labour market conditions were the strongest driver of reduced inequality during the years of strongest economic growth.

Even after improvements, inequality in LAC remains high. In most cases, the wage share in income remains below historic highs of the 1960s and 1970s and much lower than in developed countries: the wage share of most LAC countries lies below the lowest share recorded in the OECD. The same applies to the Gini coefficient. Inequality entails major costs in efficiency, which means it must be overcome to attain development (ECLAC, 2018d)

Conclusions

In the mid-2000s, Latin America achieved high growth rates and strong socio-economic performance. During this period, high growth took place in a favourable global context and booming commodity prices. LAC’s average annual GDP growth rate reached above 5% in 2004-07. High growth rates translated into substantial reductions in poverty, falling inequality and the rise of the Latin-America’s middle class.

Current economic growth in LAC is insufficient to continue the reduction in poverty and inequality. Recovery stalled in 2018, but activity is expected to regain some momentum in 2019 and 2020. Growth performance would be subdued compared to the previous decade and insufficient to close the income gap with advanced economies. The region is still characterised by an uneven performance: it is still about “Americas Latinas” in terms of cyclical positions, exposure to external shocks and policy options. The region’s low economic growth is vulnerable to external shocks hailing from several factors. These include commodity price fluctuations, a complicated global context, a more disruptive financial tightening and escalating trade tensions between key partners of the region – the United States and China. As a result of low economic growth, prospects for socio-economic progress are dimmer. The reduction of poverty and inequality are on hold, with possible reversals in some countries.

The socio-economic performance highlights both new and persistent structural challenges in the region. Some of these structural challenges go beyond income (Chapter 2). Low productivity, persistent high inequality rates, increasing poverty levels and rising citizen discontent are all symptoms of key development traps (Chapter 3). To address them, the region must strengthen domestic capabilities and rethink development strategies and international co-operation (Chapter 4 Chapter 5).

References

Beccaria, L. et al. (2013), “Urban poverty and labor market dynamics in five Latin American countries: 2003-2008”, Journal of Economic Inequality, Vol. 11/4, December, Springer.

Bloomberg L.P. (2018), Bloomberg Professional (database), Bloomberg Finance L.P., (subscription service).

CAF (2018), “RED 2018: Instituciones para la productividad: Hacia un mejor entorno empresarial”, Development Bank of Latin America, Caracas, http://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/1343.

Capital Economics (2018), “The damage from a global trade war”, Global Economics Focus, 9 July, Capital Economics, London.

Calvo, G., L. Leiderman and C. Reinhart (1996), “Inflows of capital to developing countries in the 1990s”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 10/2 (Spring, 1996), American Economic Association, Pittsburgh, US, pp. 123-139, https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/fs/jfrankel/ITF-220/readings/Calvo-et-al-Inflows-of-Capital-JEP1996.pdf.

CPB (2018), CPB World Trade Monitor (database), Netherlands Bureau for Economic Analysis, The Hague, www.cpb.nl/en/worldtrademonitor.

ECLAC (2018a), Fiscal Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2018: Public Policy Challenges in the Framework of the 2030 Agenda, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, www.cepal.org/en/publications/43406-fiscal-panorama-latin-america-and-caribbean-2018-public-policy-challenges.

ECLAC (2018b), Foreign Direct Investment in Latin America and the Caribbean 2018, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, www.cepal.org/en/publications/43690-foreign-direct-investment-latin-america-and-caribbean-2018.

ECLAC (2018c), Social Panorama of Latin America, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, www.cepal.org/en/publications/42717-social-panorama-latin-america-2017.

ECLAC (2018d), The Inefficiency of Inequality, LC/SES.37/3-P, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, www.cepal.org/en/publications/43443-inefficiency-inequality.

ECLAC (2017a), CEPALSTAT: Statistics and Indicators (database), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, http://estadisticas.cepal.org/cepalstat/portada.html?idioma=english.

ECLAC (2017b), Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2017: Dynamics of the Current Economic Cycle and Policy Challenges for Boosting Investment and Growth, LC/PUB.2017/17-P, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago, www.cepal.org/en/publications/42002-economic-survey-latin-america-and-caribbean-2017-dynamics-current-economic-cycle.

IEA (2018), Oil Market Report 13 December 2018, International Energy Agency, www.iea.org/oilmarketreport/omrpublic/.

IIF (2018), Capital Flows to Emerging Markets Report, Institute of International Finance, Washington, DC, www.iif.com/Research/Capital-Flows-and-Debt/Capital-Flows-to-Emerging-Markets-Report.

IMF (2018), World Economic Outlook, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/02/weodata/index.aspx.

Izquierdo, A. and E. Talvi (2011), One Region, Two Speeds? Challenges of the New Global Economic Order for Latin America and the Caribbean, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

Kose, A. et al. (2017), “The global role of the US economy: Linkages, policies and spillovers”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, No. 7962, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/649771486479478785/The-global-role-of-the-U-S-economy-linkages-policies-and-spillovers.

Martínez, R. (2017), Institucionalidad social en América Latina y el Caribe, ECLAC Books, No. 146 (LC/PUB.2017/14-P), Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Santiago.

OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018, Issue 2, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2018-2-en.

OECD/ECLAC/CAF (2018), Latin American Economic Outlook 2018: Rethinking Institutions for Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/leo-2018-en.

OECD/ECLAC/CAF (2015), Latin American Economic Outlook 2016: Towards a New Partnership with China, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264246218-en.

Oxford Economics (2018), Research Briefing, China: Moving Closer to Trade War, Oxford Economics, London.

Powell, A. (co-ordinator) (2017), 2017 Latin American and Caribbean Macroeconomic Report: Routes to Growth in a New Trade World, Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC, www.iadb.org/en/research-and-data/2017-latin-american-and-caribbean-macroeconomic-report,20812.html.

Reinhart, C. (2005), “Some perspective on capital flows to emerging market economies”, NBER Reporter, Summer, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, US.

World Bank (2018a), World Bank World Development Indicators (database), http://data.worldbank.org/ (accessed 1 May 2018).

World Bank (2018b), Global Economic Prospects: The Turning of the Tide?, World Bank, Washington, DC, www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects.

Notes

← 1. Simple averages. The average of Mexico and Central America includes Costa Rica, Cuba, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and the Dominican Republic. The Caribbean includes Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbardos, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Lucia, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago.

← 2. Gross domestic product per capita valuated in constant prices (purchasing power parity; 2011 international dollar). Source: IMF.

← 3. These results should not be seen as predictions, but more as illustrations of the potential impact of alternative scenarios over the region

← 4. ASEAN + 5 includes China; Japan; Chinese Taipei; Hong Kong, China and the ten members of ASEAN.