This chapter examines the current context of infrastructure development in Egypt. It reviews connectivity challenges and recent reforms to boost infrastructure investment, including private participation in infrastructure through public-private partnerships. It also proposes recommendations to overcome the remaining obstacles to improving the enabling environment for private investment in infrastructure.

OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Egypt 2020

Chapter 8. Infrastructure connectivity

Abstract

Summary and policy recommendations

Infrastructure is critical for Egypt’s productivity and sustained long-term economic growth. Its essential function is to enhance connectivity, which can allow firms to integrate into regional and global value chains (RGVCs). Under the right conditions, it can reduce trade and logistics costs, foster export product diversification and increase competitiveness by fostering the development of large and efficient markets. Such benefits cannot materialise without adequate infrastructure networks linking markets efficiently, predictably and sustainably. When transport costs are high, and procedures are unclear and uncertain, only large firms can avail themselves of the opportunities brought about by RGVCs. Bringing new actors into RGVCs, including Egyptian small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), requires connectivity that is more readily accessible to all. Connectivity is not just important for firms in Egypt, but for households as well. It plays a critical role in enabling access to new jobs, skills development, and higher wages, as well as greater access to a diversity of goods and services. As Egypt continues to experience rapid population growth and economic and industrial transformation, the need for effective and high-value infrastructure connectivity remains crucial.

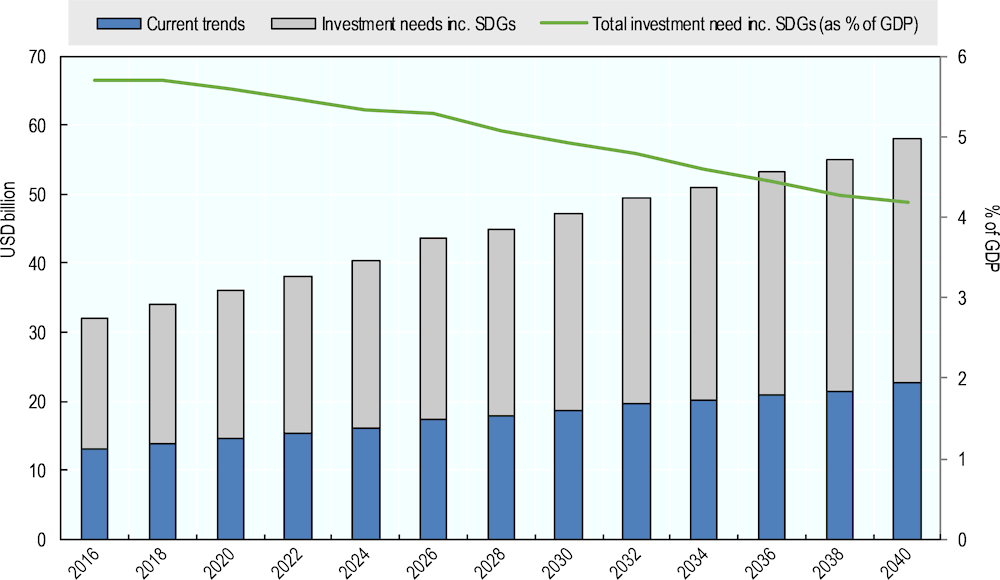

The low levels of investment in infrastructure have raised concerns that Egypt may not be able to sustain the current stock of infrastructure given its natural depreciation and aging, let alone expand it to meet growing demand. According to the Ministry of Investment and International Cooperation, in the past five years, Egypt has invested around USD 61.4 billion in infrastructure to connect governorates, enhance accessibility and mobility of goods. The Global Infrastructure Hub estimates that Egypt needs an average of USD 675 billion of investment, or 5% of GDP, between now and 2040. At current levels of spending, this translates to an investment gap of USD 230 billion per annum, or 1.7% of GDP. The infrastructure gap is especially high for critical infrastructure such as energy, telecommunications and transport. Bridging this financing gap requires a more cross-cutting approach to mobilise quality investment for connectivity infrastructure. Such endeavours are a challenge, but the payoffs from successfully improving infrastructure connectivity can be large.

While in recent years Egypt has significantly improved the quality of its trade and transport infrastructure, it still faces important infrastructure shortcomings. These include the lack of multi-modal transport, an over-reliance on roads, a rail sector in need of reform, and a fragmented port system. This leads to high transport costs and poor logistics performance compared to other countries in the region. Logistics costs in Egypt account for around 20% of GDP compared with a global average of 10-12%, and the operating costs for trucks are approximately 30-50% higher than in Lebanon and Jordan (IFC, 2013; World Bank, 2015a). Overall, such bottlenecks in infrastructure constrain economic growth by around two percentage points per year, hindering the distribution of resources and contributing to a disproportionate concentration of economic activity in metropolitan areas (EBRD, 2017).

The need to improve connectivity is acknowledged in Egypt’s “Vision 2030” and its transport and infrastructure plans, which aim to increase the capacity of the transport sector and boost its share in international and regional transport volumes. To achieve these objectives, the government has embarked on a number of ambitious mega-infrastructure plans, including the new Suez Canal Zone (SCZone). Currently, the Canal handles close to 10% of global seaborne trade connecting Africa, Asia and Europe, representing an effective logistics and strategic base for ships and trade transiting the Suez Canal; it can also have significant development benefits for Egypt. Close co-ordination of logistics sector development with business operations and activity in the industrial and free zones will be crucial to meet these objectives.

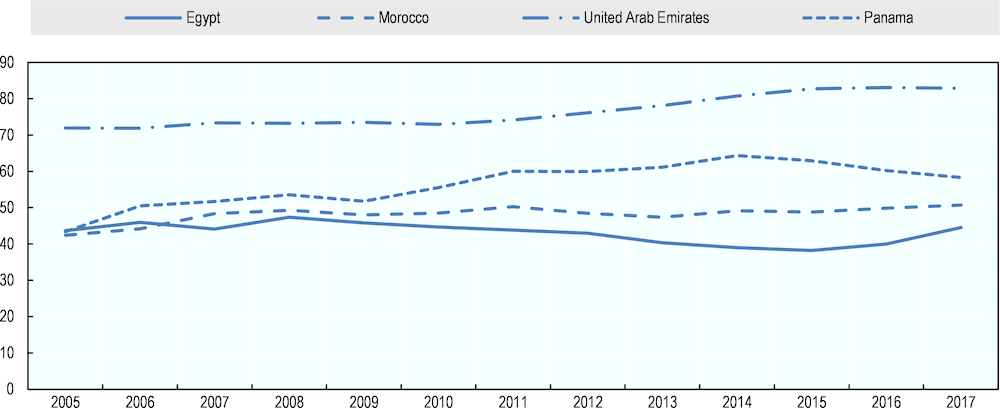

Egypt’s connectivity depends on how well it is positioned in global logistics networks, infrastructure and services. While the economy moved up four places (from 56th to 52nd) in the infrastructure pillar of the Global Competitiveness Index 2019 (WEF, 2019), and made considerable strides in areas such as maritime connectivity, it has much to do to improve connectivity with the rest of the world in other areas that are relevant to today’s globalised world. The DHL Global Connectedness Index, which measures cross-border flows of trade, investments, information and people, reveals a low connectivity for Egypt, placing it below similar peers such as Morocco, the United Arab Emirates and Panama. While most other countries have experienced a rising trajectory since 2008, Egypt experienced the opposite in part due to the very low intra-regional integration across all four pillars (Figure 8.1) (Steven et. al, 2019). According to the Index, improving the operating environment and developing infrastructure links could have a significant positive impact on the depth of Egypt’s connectivity and would further connect the economy to world markets.

Figure 8.1. Global Connectedness Index (0-100) (2005-17)

Note: Global Connectedness is measured in this report based on the depth and breadth of countries’ integration with the rest of the world as manifested by their participation in international flows of products and services (trade), capital, information, and people (the four pillars of the DHL Global Connectedness Index).

Source: Steven A. Altman, Pankaj Ghemawat, and Phillip Bastian, "DHL Global Connectedness Index 2018," Deutsche Post DHL, February 2019

Egypt has adopted major economic liberalisation policies since the 1970s leading to sector-specific laws to allow private sector provision of public services, and opened the door for more private investments in infrastructure, although it only introduced a regulatory framework for public-private partnerships (PPPs) in 2010. PPPs bring some important regulatory and institutional mechanisms to improve Egypt’s infrastructure delivery capacity. Yet, there is a lack of a track record, capacity and experience to develop PPPs by the PPP Central Unit, and public support for PPPs is low. While the framework is considered to be in line with international best practices, it does not replace the old sector-specific laws that regulate the procurement of infrastructure projects. This old system may still be used by the government in the future, especially in the power sector (EBRD, 2011).

Notwithstanding the recent efforts to provide a framework for public procurement, the government also needs to strengthen its planning capacity and coordination for infrastructure projects. Currently, numerous infrastructure priorities in Egypt are laid out in different strategies. Often, the allocation of budget for the national plans is an annual exercise, despite the fact that various ministries have to prepare their investment planning estimates over various time horizons such as the 5-year plans. The government plans to strengthen its fiscal planning by introducing the medium-term expenditure framework, which will set multi-year expenditure ceilings by major spending categories, including infrastructure (IMF, 2018). Such planning of current and capital expenditure within a medium-term budget framework could also ensure that infrastructure investments are sustainable and that maintenance spending is fully taken into account (IMF, 2014).

Policy recommendations

Clarify the regulatory frameworks for infrastructure investments to provide potential investors with clear, predictable and consistent policies. Currently, the PPP Law coexists with other channels of procuring infrastructure projects such as the public utilities legislation and a number of sector-specific or project-specific laws. The government should build a clearer and more transparent regulatory framework governing infrastructure activities.

Provide more opportunities for private participation in infrastructure, including through PPPs. Despite Egypt’s robust PPP regulatory framework, private sector participation in the infrastructure and energy sectors has been limited.

Engage with stakeholders in local communities to ensure support for PPP projects. Currently, there is low public support for PPP projects, partly due to a lack of adequate community consultation to guide project selection and secure public support for projects. In order to gain more public support for infrastructure projects, the government needs to involve more systematically all the relevant stakeholders from the earliest stages of infrastructure planning to ensure support and that their needs – as well as social, economic, environmental and governance risks – are correctly assessed, addressed and adequately reflected in the contractual structures.

Strengthen the capacity and co-ordination across the government for planning and assessing infrastructure priorities to ensure that infrastructure strategies are well integrated with other types of planning such as industrial development strategies and land use plans. For example, infrastructure plans in special economic zones such as the SCZone should be well connected with the hinterland. Achieving this also requires better co-ordination between different branches of government.

Prioritise the completion and upgrade of the rail lines as well as other projects that will facilitate multi-modal freight and passenger traffic. Despite ambitious modernisation projects currently undertaken, the rail network is still not competitive enough. Further strengthening the legal framework and actively promoting private investments in railway projects could make the railway system a reliable alternative to congested roads.

Improve coordination of port and multimodal transport planning to facilitate more river-based transport. Currently, ports contribute less than 1% of inland transport, which is mainly due to the poor integration of river transport to the country’s transport networks.

Further strengthen the legal framework for public procurement to increase tender participation, supplier diversity and a more competitive procurement environment. While the 2016 Law on Public Procurement introduces procedures to enhance transparency and reduce discretion in public procurement, the consistent application and enforcement of the law by the involved procurement entities is weak.

Ensure that infrastructure projects are grounded in efficiency rather than fiscal motivations. Building capacity among government entities to assess value for money over the lifecycle of an infrastructure asset is crucial to make sure that investments benefits users and society at large.

Connectivity matters for Egypt’s economy

In recent years, the setting up of highly connected locations such as Dubai, Singapore and Panama highlights how countries with regional transhipment ports have leveraged global connectivity to deepen their role in the global economy by using hubs, gateways or ports as drivers of regional economic growth (OECD, 2013). A common trend is the development of logistics zones to capture opportunities from global outsourcing and offshoring (Rodrigue, 2017). Egypt’s recent expansion of the Suez Canal, coupled with reforms to attract foreign investment to establish export-oriented industries, aim to transform the country into a global logistics hub and increase its participation in regional and global value chains (RGVCS).

More broadly, connectivity can be understood as infrastructure supporting cross-border trade and investment flows. The connectivity of individual economies, or how they are positioned in global trade networks, matters for the cost of trade, competitiveness, and integration in RGVCs. The performance of these networks sustaining trade such as shipping, logistics and data, is influenced by private investments in physical infrastructure, such as roads, railroads, and airports.

Key infrastructure challenges

Egypt’s economic infrastructure, including transport, energy, ICT and water resources and the associated services is vital for industrial development. It is not only used as an input in production sectors, but also contributes to making Egyptian industrial output competitive in domestic, regional and international markets. Yet, numerous deficiencies across all sectors of infrastructure currently limit the contribution made by infrastructure to the country’s industrial development.

Egypt has made progress in terms of infrastructure networks but transport costs are very high

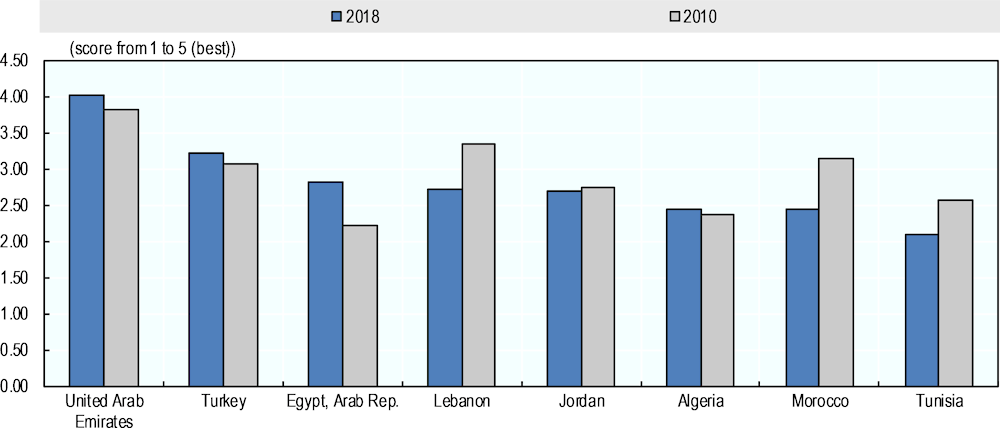

In recent years, Egypt has significantly improved its performance under the indicator of “quality of trade and infrastructure” (e.g. ports, roads, airports, information technology) of the World Bank’s Logistic Performance Index between 2010 and 2018 (Figure 8.2). According to this Index, Egypt advanced its score from 2.22 in 2010 to 2.82 in 2018 on a scale from 1 (worst) to 5 (best), ranking from 106th (out of 155) in 2010 to 58th (out of 160) in 2018. Yet, despite significant progress achieved since 2010, Egypt still faces some important infrastructure shortcomings as reflected in a number of infrastructure stock indicators and perception assessments (Table 8.1). Currently, there is no large logistics provider with a consistent distribution of services around road-based transport in Egypt. More than one third of the road fleet is owned by small fragmented firms, with cooperatives or public firms owning the rest. This poses challenges for big consignments and leads to a high cost of domestic transport.

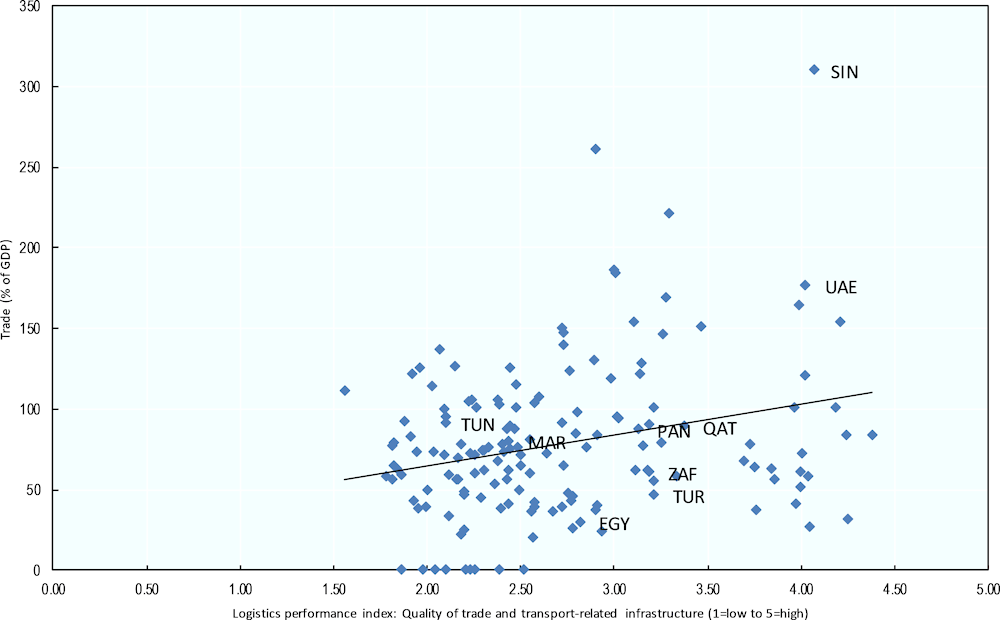

These high transport costs make Egypt a relative outlier in terms of its logistics performance compared to its regional peers (Figure 8.3). Because of Egypt’s high logistics costs, which account for around 20% of GDP compared with a global average of 10-12%, and inadequate infrastructure, operating costs for trucks are approximately 30-50% higher in Egypt compared to countries such as Lebanon and Jordan (IFC, 2013; World Bank, 2015). Furthermore, transport costs can vary by a factor of 2.5 across Egypt, with more distant regions experiencing worse delays. Inefficient logistics also adds significant cost and time to trade operations, especially for agribusiness exporters. This hinders the distribution of resources and contributes to a disproportionate concentration of economic activity in metropolitan areas (EBRD, 2017).

In order to improve the logistics system and address the high logistical costs, the Ministry of Transportation is currently planning to establish a network of logistical areas and villages. A law was drafted to organise the establishment and management of logistical areas and villages to establish seven logistical cities in Damietta, Sohag, 10th of Ramadan, Borg El Arab, Sadat and Beni Suef, and 6th of October. The establishment of the logistical areas and villages is expected to contribute to industrial and trade promotion, but also to increase investments and further reduce logistical costs.

Figure 8.2. The World Bank's Logistic Performance Index, Infrastructure Indicator

Source: World Bank Logistics Performance Index database

Table 8.1. Selected infrastructure indicators across selected peer countries

|

|

Egypt |

Morocco |

Panama |

Saudi Arabia |

Singapore |

South Africa |

Tunisia |

Turkey |

United Arab Emirates |

Middle East and North Africa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Electricity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Access to electricity (% of population) 2016 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

93.4 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

84.2 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

98.0 |

|

Electric power transmission and distribution losses (% of output) 2014 |

11 |

15 |

14 |

7 |

2 |

8 |

15 |

15 |

7 |

14 |

|

Quality of electricity supply (1-7 (best), WEF 2017-2018 |

5.0 |

5.6 |

5.2 |

6.2 |

6.9 |

3.9 |

5.1 |

4.4 |

6.5 |

5.1 |

|

ICT |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Mobile telephone subscriptions (per 100 people) 2017-2018 |

114 |

121 |

172 |

158 |

147 |

142 |

126 |

97 |

204 |

140 |

|

Individuals using the internet (% of population) 2016 |

41 |

58 |

54 |

74 |

81 |

54 |

50 |

58 |

91 |

43 |

|

Fixed broadband internet subscriptions (per 100 people) 2017-2018 |

5.2 |

3.7 |

9.5 |

10.8 |

25.4 |

2.8 |

5.6 |

13.6 |

13.3 |

10.3 |

|

Transport |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Quality of roads, 1-7 (best), WEF¹ 2017-2018 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

4.4 |

4.8 |

6.3 |

4.4 |

3.7 |

5.0 |

6.4 |

4.4 |

|

Quality of railroad infrastructure, 1-7 (best), WEF¹ 2017-2018 |

3.3 |

3.9 |

4.5 |

3.3 |

5.9 |

3.5 |

2.8 |

n/a |

3.3 |

4.4 |

|

Liner shipping connectivity index (maximum value in 2004 = 100)³ 2016 |

62.5 |

64.7 |

53.4 |

61.8 |

122.7 |

37.1 |

6.3 |

49.6 |

70.6 |

- |

|

Quality of port infrastructure, 1-7 (best), WEF¹ 2017-2018 |

4.7 |

5.0 |

6.2 |

4.7 |

6.7 |

4.8 |

3.3 |

4.5 |

6.2 |

4.4 |

|

Growth of Container port traffic (TEU: 20 foot equival. unit, CAGR, %) 2007-16 |

24 |

761 |

36 |

45 |

9 |

14 |

14 |

47 |

35 |

38 |

|

Quality of air transport infrastructure, 1-7 (best), WEF¹ 2017-2018 |

5.1 |

4.8 |

6.0 |

4.9 |

6.9 |

5.6 |

3.9 |

5.4 |

6.6 |

4.6 |

1. data for Morocco is 2008 instead of 2007

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators database, World Economic Forum Competitiveness Index (2018).

Figure 8.3. Egypt is an outlier relative to its peers in terms of logistics costs and trade openness

Source: World Bank Development Indicators

Transport connectivity

Transport infrastructure has improved recently, but multimodal connectivity is still lacking

Current transport infrastructure bottlenecks and lack of multimodality act as key constraints to trade, mobility, job creation and service delivery across Egypt (World Bank, 2015). The transport sector in Egypt serves an area of around 1 million km2 and a population of close to 100 million. While road infrastructure is relatively dense and of good quality, with 95% of its roads paved, all alternative transport systems remain inadequate. For freight, there is not yet an integrated scheme that would encourage intermodal rail-road-river transport. More than 99% of Egypt’s international freight relies on maritime transport, both in terms of volume and external logistics costs (EIB, 2013), while roads, followed by railways (4%) and the Nile River (1%), move more than 95% of domestic freight. Trucks move 90% of the country’s domestic freight, but given that the biggest trucking companies have at most a 10-truck fleet, this leads to an inefficient system where quality is not considered and creates a missing link in Egyptian export chains. While most OECD and MENA countries also rely heavily on road transport for domestic logistics, they tend to use rail services in a higher percentage than Egypt does. Because of road congestion in Egypt, railways could be an alternative for freight transport, but the rail network does not offer a viable alternative to the road network at present.

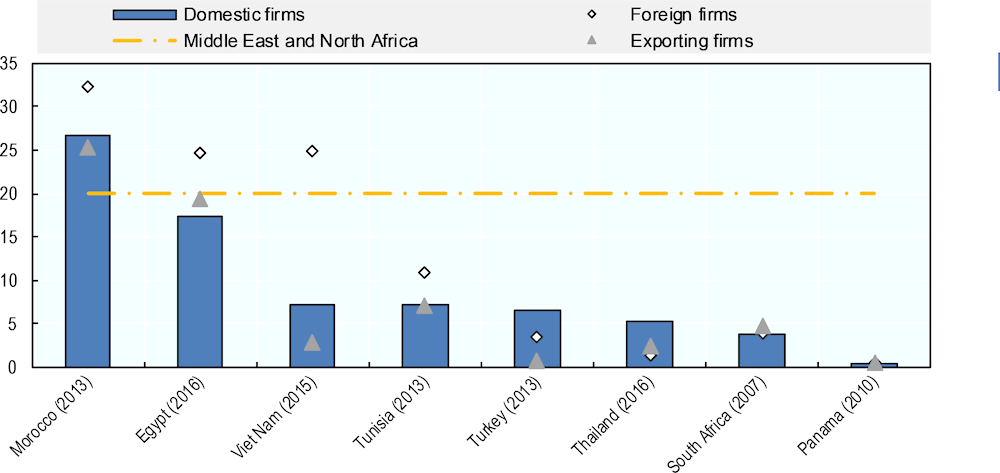

According to the World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt (2016), over 17.4% of domestic firms reveal that transport is a major constraint to their current operations (Figure 8.4). While this is lower than Morocco’s 27% and slightly below the MENA average of 20%, it is significantly higher than in peer economies in the region (Tunisia 7%, Turkey 6.5%). Compared to their domestic peers, foreign manufacturing firms face higher constraints to their operations in Egypt. Around 25% identified infrastructure in Egypt as a major constraint, as compared to 11% in Tunisia, 4.1% in South Africa, 3.6% in Turkey, or only 0.6% in Panama. While these obstacles apply to firms across the whole of Egypt, they are less important for those in special economic zones such as the Suez Canal region (9.4% compared to 32.4% in Southern Upper Egypt).

Figure 8.4. In general, foreign firms have higher transport constraints than domestic firms

Note: Foreign ownership refers to 10% or more foreign ownership

Source: World Bank Enterprise Survey

Despite government efforts to address traffic congestion, this remains a serious problem especially in urban areas, in part due to gasoline price subsidies and low road maintenance. In Greater Cairo, where the density of the most heavily inhabited areas is 1500 inhabitants/km², which is almost triple the global average (World Bank, 2015), commuting times amount to 90 minutes. Past attempts to address congestion and road safety at the city level have resulted in modest increases in road construction, but the results have been mixed.

The dependence of the Egyptian logistics chain on road services makes it even more vital for these problems to be corrected to decrease export time and increase product quality, thereby opening up new markets for Egyptian exports. Recognising the importance of facilitating cross-border movement of goods, in 2016 Egypt started preparations to join the International Road Transports Convention system, which is the only universal customs transit system in existence for road transport (IRU, 2016). Such a system would further increase the transit volumes in Egypt and would strengthen its strategic position as a logistics and transport hub between Europe, Asia and Africa.

Infrastructure accessibility varies greatly across regions

The road network is mostly concentrated in and around Cairo and the Nile Delta area. A substantial part of the road network outside those areas remains substandard and needs upgrading, despite major improvements in connecting the major cities of Upper Egypt to the Greater Cairo Area. For Egyptian firms, the lack of road connection to rural areas leads to up to 40% of losses in the value of products transported from Upper Egypt to wholesaler. This may also explain why only a small share of Egyptian firms export to global markets (EBRD, 2017). Significant improvements in transport and logistics infrastructure will help to spread economic activity outside metropolitan Egypt and help increase market access and agricultural income for farmers especially in rural Upper Egypt, where they experience long shipping times. The government has focused on further improving infrastructure accessibility across the country. For instance, the Ministry of Transportation developed horizontal roads1 connecting locked governorates in Upper Egypt and Oasis to other governorates near the Red Sea and helping to spread economic activity outside of metropolitan areas while increasing market access and exports from Red Sea ports.

Limited upgrading has left the rail network sector of poor quality and uncompetitive

A public monopoly on the existing railway network in Egypt has led to under-investments and the need to update services and improve safety. The railway system is the oldest in the world, after the United Kingdom. The network composed of around 9 800 kilometres of railways is currently being used for freight and passenger services, providing relevant supply chain links between the key seaports and the main cities. Due to under-investment and reliance on low fare passenger traffic, the system is operated inefficiently with low environmental performances. The lack of ICT also makes rail transport risky. An estimated 85% of the signals in the system are mechanical and in need of maintenance or replacement, while only 15% are electrical signals (Egyptian National Railways, 2018). Discussions on the need to reform the state-owned Egyptian National Railway have led to the recently approved Law No. 20 of 2018, which ended state monopoly over the national rail system projects and gave the private sector the legal framework to be able to participate in such projects (Amereller, 2018).

Egypt suffers from a fragmented port system with considerable excess capacity

In contrast to roads and railways, port infrastructure has been the main recipient of investments by the Egyptian government over the past decade. Yet, the lack of a co-ordinated port and multimodal transport planning and development strategy has resulted in a fragmented port and maritime terminal system with considerable excess capacity even in some key economic regions, such as the Southern region. Egypt’s ports are geographically fragmented (World Bank, 2015a). Main challenges facing the Egyptian ports include: (i) limited multimodal connectivity regarding rail access and high speed road connection to ports; (ii) lack of logistical platforms; (iii) IT infrastructure not fully compliant with international standards on safety and security (EIB, 2013).

Egypt has 1 850 km of navigable waterways with more than 40 ports, of which 12 are commercial ports, but they currently account for less than 1% of inland transport in the country. This low level is mainly due to the poor integration of river transport in the country’s transport networks (EBRD, 2013). Instead, Egypt’s ports handle the majority of its international trade. Among the most important ports in terms of capacity are Alexandria, the biggest port in Egypt, and the Port of Dekheila, which is a natural extension to the Port of Alexandria, followed by Damietta and Port Said (Table 8.2) jointly handling 85% of Egypt’s cargo tonnage and 92% of its containerised trade. Alexandria Port is by far the most important, handling about 60% of Egypt’s foreign trade. There is also a relatively elevated concentration of container traffic in ports with a high trans-shipment activity, of which Damietta and Port Said handle the majority.

Table 8.2. Commercial Port Capacity in Egypt

|

|

Maximum capacity |

Area |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Cargo (million TEUs) |

Containers (Million TEUs) |

Land (km2) |

Total (km2) |

|

Alexandria |

37.9 |

1.0 |

1.60 |

8.40 |

|

El Dekheila |

27.1 |

1.0 |

3.50 |

6.20 |

|

Damietta |

19.75 |

1.2 |

7.9 |

11.80 |

|

Port Said |

12.78 |

0.8 |

1.30 |

3.00 |

|

El Arish |

1.2 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.23 |

|

East Port Said |

12.0 |

2.7 |

70.60 |

72.10 |

|

Suez |

6.6 |

0 |

2.30 |

162.40 |

|

Petroleum Dock |

4.14 |

0 |

1.16 |

|

|

Adabiya |

7.93 |

0 |

0.85 |

|

|

Sokhna Port |

8.5 |

0.4 |

22.30 |

87.80 |

|

Hurghada |

0 |

0 |

0.04 |

9.94 |

|

Safaga |

6..37 |

0 |

0.62 |

57.11 |

|

El Tour |

0.38 |

0 |

0.43 |

1.65 |

|

Nuweiba |

1.9 |

0 |

0.4 |

9.9 |

|

Sharm El Sheikh |

0 |

0 |

0.2 |

88.31 |

|

Total |

146.55 |

7.1 |

113.25 |

518.84 |

Source: Ministry of Transport. Maritime Transport Sector (MTS). The Egyptian Port’s Capacity

http://www.mts.gov.eg/en/content/275/1-83-The-Egyptian-Ports-Capacity

Despite improved maritime transport in Egypt, the ports transhipment function is still limited

The Suez Canal, which plays such a strategic role in international trade, mainly benefits Egypt through the tariffs collected from ships and vessels that cross it (UNECA, 2015). But the potential opportunities offered by the Canal to attract foreign manufacturers that are looking for locations close to markets in Europe, the Middle East and Africa are still to be seized. In contrast to other canals and straits, the port transhipment function related to the Suez Canal traffic is partly captured by other ports in the region such as Djibouti in the South of the Canal, and Piraeus in the North, as well as a range of other transhipment ports in the Mediterranean. In comparison, the three main ports along the Malacca/Singapore Straits (Singapore, Port Klang and Tanjung Pelepas) capture almost all of the transhipment cargo in the region, whereas the main ports at both sides of the Panama Canal also capture a dominant share of the regional transhipment cargo, even if there are various large transhipment hubs in the Caribbean. Maersk is now using East Port Said as one of its main hub locations, moving activities from some Mediterranean hubs to Suez, but almost all shipping companies use several options, so there is a need for transhipment ports to continuously improve the attractiveness and competitiveness of the Egyptian ports. In order to achieve more transhipment, ports along the Suez Canal need to attract more calls from shipping lines.

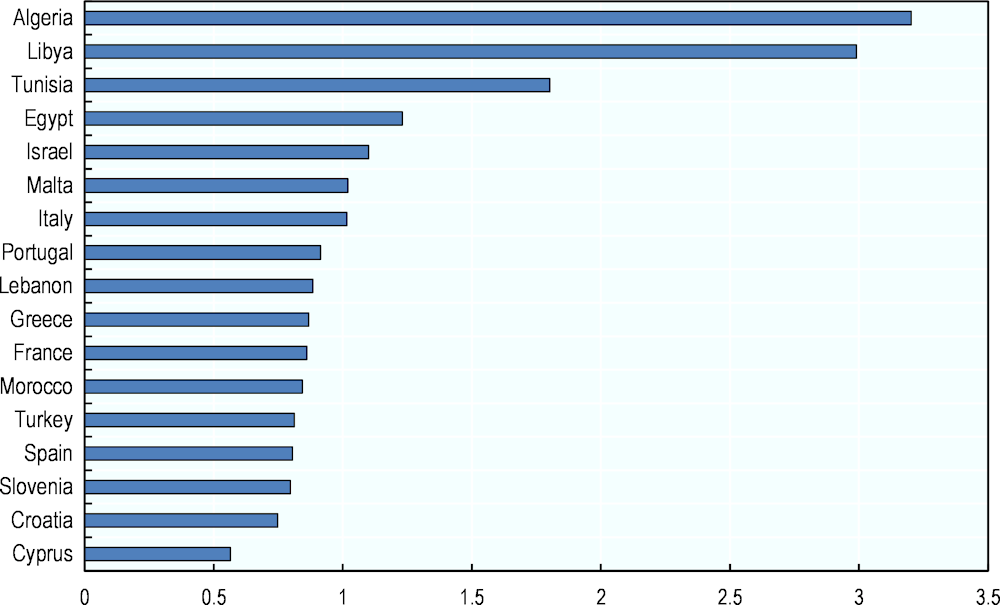

A preliminary assessment of Suez Canal ports seems to indicate that main bottlenecks could consist of relatively high ship-turnaround times and the low level of value-added services for shipping firms compared to its regional competitors such as Turkey and Morocco (OECD, 2017a) (Figure 8.5). The great majority of world ports manage to achieve average ship turn around in under two days, most ports in Asia even less than one day. Another bottleneck for Suez Canal ports is the fairly low level of value added services for shipping firms. Other transshipment ports are developing services such as ship repair, value added logistics and well-developed feedering and short-sea services. Average ship turn-around time is a very relevant performance indicator, since longer than expected port times present additional costs to shipping lines, which might offset any cost advantage that the Suez Canal ports might be able to offer due to lower port labour costs.

Figure 8.5. Med container ship turnaround times per country in 2014

Note: The calculations of ship turn-around times are based on vessel movement data over May 2014 and from Lloyds Intelligence Unit. The estimated coverage of this database is > 95% of all vessel movements. For the purpose of this analysis only fully cellular container ships with GT >100 were taken into account. The database has per vessel call an arrival time at berth and a departure time from berth, allowing for calculation of duration of port stays. For our analysis all port stays were excluded that were smaller than 0.20 days and longer than 7 days. In this way, bunkering calls and extreme values were excluded. The database that resulted included 38,843 port calls in May.

Source: ITF/OECD elaborations based on data from Lloyds Intelligence Uni

Energy and ICT connectivity

Access to electricity has greatly improved, but its reliability remains a concern for investors

Access to reliable and affordable electricity is a key decision factor for investors in higher-value added industries where electricity is a major component of their cost structures. According to the World Bank Doing Business Report 2020, Egypt has improved the reliability of electricity supply by implementing automated systems to monitor and report power outages (World Bank, 2020). This performance is relatively better than the average of the MENA region, but it is still lower than some of its regional peers (Table 8.3). Egypt also performs well compared with its peers in terms of obtaining a permanent electricity connection for a newly constructed warehouse. Until recently, the economy was facing significant electricity supply problems, causing repeated power outages around the country, which led to a low quality of electricity supply (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2014).

For years, energy subsidies have created significant distortions in the economy. They are partly responsible for bottlenecks in supply chains and declining investments across the supply chain, including oil and gas exploration and production. Although Egypt is currently a relatively low carbon economy, its carbon emissions per GDP and energy consumption per GDP, are among the highest in the region and almost double the global average (World Bank, 2015b). As a consequence, there are limited commercial incentives for efficiency in the provision of energy supply.

Table 8.3. Getting electricity in selected MENA countries

|

Getting Electricity Rank |

Procedures (number) |

Time (days) |

Cost (% of income per capita) |

Reliability of supply and transparency of tariff index (0-8) |

Price of electricity (US cents per kWh) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Algeria |

102 |

5 |

84 |

967 |

5 |

2.1 |

|||

|

Egypt |

77 |

5 |

53 |

180.2 |

5 |

9.7 |

|||

|

Jordan |

69 |

5 |

55 |

285.3 |

6 |

24.6 |

|||

|

Morocco |

34 |

4 |

31 |

1308.8 |

6 |

12.4 |

|||

|

Oman |

35 |

5 |

30 |

50.0 |

7 |

6.0 |

|||

|

Saudi Arabia |

18 |

2 |

35 |

27.9 |

6 |

7.4 |

|||

|

Tunisia |

63 |

4 |

65 |

719.1 |

6 |

7.7 |

|||

|

Turkey |

41 |

4 |

34 |

62.3 |

5 |

8.9 |

|||

|

United Arab Emirates |

1 |

2 |

7 |

0.0 |

8 |

10.9 |

|||

|

Middle East and North Africa |

86 |

4.4 |

63.5 |

419.6 |

4.4 |

||||

|

OECD |

43 |

4.4 |

74.8 |

61.0 |

7.4 |

||||

Source: World Bank Doing Business 2020.

The government has recently implemented a reform programme targeting gradual removal of energy subsidies, which is critical to enhance its power generation capacity and the industry’s ability to support industrial development. According to the authorities, energy subsidies were reduced by over three percentage points of GDP in the FY20 budget compared to FY17. In the electricity sector, prices were already raised by an average of 30% in July 2016, and by another 40% in July 2017.

Reforming other subsidies such as fuel will also help reduce traffic on the roads (World Bank, 2015b). This will facilitate the elimination of existing distortions to the costs of production factors that have disproportionately benefited energy-intensive industries (IMF, 2018).

Egypt has not yet managed to diversify its power supply for sustainable industrial development

Wind and solar energy represent two good alternatives for producing new and renewable energy in Egypt. The country is endowed with among the best solar resources in the world, as the number of sun rising hours in the remote areas can vary between 2300 to 4000 hours per year (Ministry of Petroleum, 2018). But despite this, it has not yet managed to diversify its power supply and is still relying on fuel consuming power plants for over 60% of its power supply. While all citizens have access to electricity, which has resulted in improved education and health outcomes, companies requiring significant energy supply still face numerous challenges.

The government has shown commitment to deepen the use of renewables both at the policy and strategic level. In 2014, it adopted the Sustainable Energy Strategy 2035 to deepen the use of renewables with a target of meeting 20% of its electricity needs from renewable sources by 2022 from just 3% today with wind providing 12%, hydro power 5.8%, and solar 2.2% (UNECA, 2015). This was followed by the Feed-in-Tariff Act to encourage private investments in the renewable energy sector (EIU, 2018). Importantly, the Act allocates state-owned lands to renewable power projects, for purchasing electricity from solar and wind renewable sources, makes it mandatory for electricity companies to source and trade the energy produced via these projects, and provides attractive tax incentives for private investments in renewable projects (UNECA, 2015). Another major power sector policy reform is the new Electricity Law (Law No. 87 of 2015), which was approved in 2015 to gradually liberalise the electricity transmission market towards a competitive model where private sector producers can sell electricity directly to consumers at market prices. Such policies have already led to a number of projects, particularly in the Zaafarana area of the Gulf of Suez, where the wind speed reaches 10m/second and the capacity for renewables is higher.

ICT infrastructure has been expanding fast in recent years. Further investments can catalyse industrial growth and promote high-tech industries

ICT infrastructure in Egypt has expanded significantly in recent years, driven by government initiatives as well as by the private sector. This expansion was facilitated by a partial deregulation and liberalisation of the ICT sector, especially in wireless and data services areas (UNCTAD, 2011). ICT also contributed to improving the way in which services are delivered to industry and indirectly to the industrial development of the country, which in turn provides skilled and productive human resources for the manufacturing sector (MCIT, 2016). The sector currently represents 3.9% of GDP, and the government aims to achieve 8.4% of GDP by 2020, creating 250 000 direct job opportunities. The government recently introduced 4G data connectivity and issued four 4G LTE licences in 2016, accelerating further the growth of the sector. Currently, there are four mobile telecom providers namely Vodafone Egypt, Etisalat Misr, Orange Egypt and WE, some of which are investing heavily in network expansion, quality of service improvements and new technologies ((Egypt Independent, 2017). According to the Mobile Connectivity Index2 2018, which measures the performance of countries against the key enablers of mobile internet adoption – infrastructure, affordability, consumer readiness, and content and services – Egypt is a “transitioner” in the MENA region (54.2), similar to Jordan (54.2) and above Algeria (51.6), but below its regional peers such as Morocco (57.7), Tunisia (60.3) (GSMA, 2019).

To keep up with increases in demand, the fixed and mobile broadband transmission capacity overall will need to grow at double-digit rates for the near future. Significant investments are still necessary to expand broadband access and to alleviate overloaded networks that affect the quality of services. While the coverage of mobile phones surpasses the population (114 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants), this is lower than the MENA regional average of 140 or other comparator countries such as Morocco (121) or Tunisia (126). Egypt also faces medium to high barriers in internet accessibility (McKinsey, 2016). By 2017, the internet penetration rate reached 47% (although Egypt has the largest population of internet users in the MENA region), compared to Tunisia (64), Morocco (65) and Turkey (71) (World Bank, 2020). The government’s strategy includes structural measures to accelerate private sector participation in ICT to expand basic infrastructure including the broadband optic fibre networks, cloud computing infrastructure, in addition to submarine cables. Better ICT infrastructure is also expected to increase the volume of e-commerce given that Egypt has the largest population of prospective online shoppers in the Arab world (MCIT, 2016).

Taking stock of public and private investments in infrastructure

Estimated investment gap in infrastructure amounts to USD 675 billion or 5% of GDP until 2040

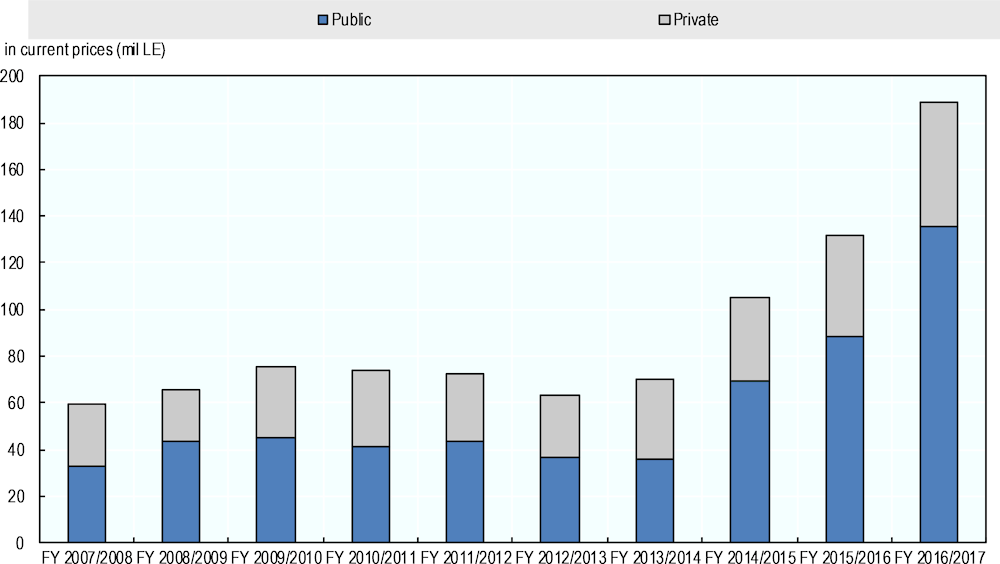

Infrastructure investments rebounded in 2013 when the idea that infrastructure would revive growth was the main driving principle of an economic revival programme that was introduced in August 2013. The government then allocated USD 3.2 billion in additional infrastructure spending (1.2% of 2012 GDP) to help raise GDP growth from 2.3% to 3.5%, reduce unemployment from 13% to 9% and reduce the government’s budget deficit from 14% to 9% of GDP (ibid). Data by the Central Bank of Egypt suggests that the government is still the main provider of infrastructure, investing over 56% of total public investments in economic infrastructure in FY 2016-17, up from 47% in FY 2007-08 (Figure 8.6). Private sector investments in infrastructure have been only 17-20% of total investments.

Figure 8.6. Public and private investments in economic infrastructure assets

Note: Economic infrastructure covers investments in “Electricity”, “Water”, “Drainage”, “Construction and Building”, “Transportation and Storage”, “Communications”, “Information”, and “Suez Canal”.

Source: Central Bank of Egypt

According to recent estimates by the Global Infrastructure Hub, under a 4% GDP growth assumption each year3, Egypt’s investment needs are USD 675 billion or 5% of GDP on average until 2040 (Figure 8.7). At current levels of spending, the investment gap in Egypt amounts to around USD 230 billion (or 1.7% of GDP) across all sectors, but it is more prevalent in cross-border infrastructure and in energy and transport. With such a high gap, there are concerns that the economy has reached a level of infrastructure investment that is unlikely to sustain the current stock of infrastructure given its natural depreciation and aging (UNIDO, 2017). Such concerns are also valid across the African continent, where the infrastructure deficiency alone is estimated to lower companies’ productivity by 40%, which leads to increased production and distribution costs, lowers competitiveness and deters the adoption of new innovation technologies (ibid).

Closing such a high infrastructure gap is expected to have a significant impact on jobs in Egypt, especially given that it is only one of the two countries in the region together with Saudi Arabia to employ more workers in the infrastructure sector than in construction. Similarly, across the MENA region, meeting annual investment needs would lead to around 2 million direct jobs and 2.5 million direct, indirect and induced infrastructure related jobs throughout the region.

Figure 8.7. Infrastructure investments in Egypt needs to be scaled up significantly

Source: Global Infrastructure Hub, Global Infrastructure Outlook 2016

Private sector participation in infrastructure has been limited, leading to irregular or low quality of service provision.

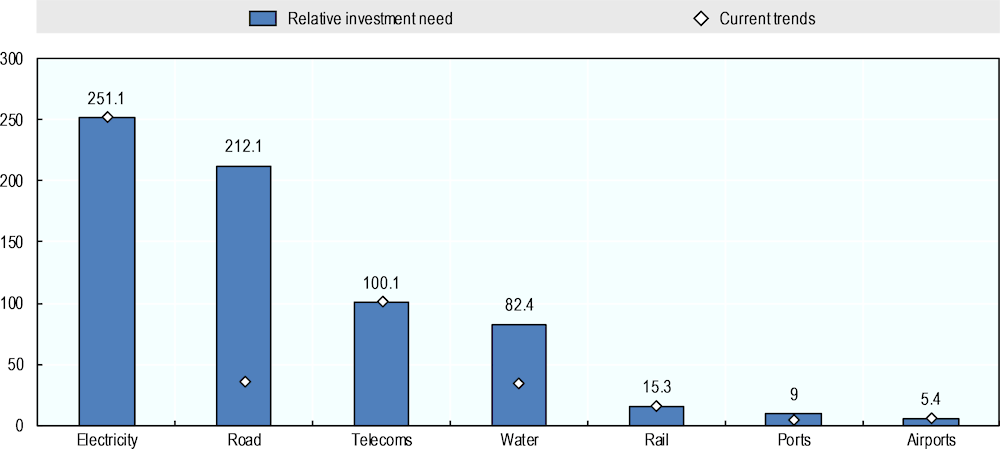

The magnitude of private investments in transport, municipal and energy infrastructure sectors has been rather limited, leading to irregular or low quality service provision. The prevalence of private ownership is still low, while foreign ownership is even more limited. It is only in recent years that Egypt has been able to attract considerable private investments in infrastructure, owing to a national policy encouraging private investments. For example, the number of infrastructure projects with private participation went from only two in 2016 to 25 in 2017. Most of these investments were in renewable energy, particularly within the Benban Solar Park (World Bank PPI, 2018). Nevertheless, there are still large gaps in terms of private investments at the sectoral level. The sectors requiring more investments by 2040 are electricity, roads, telecoms and water (Figure 8.8). The largest gaps are in the electricity and road sectors, which will require investments of around USD 251 billion and USD 212 billion respectively. Some sectors also present a large gap between the relative investment needs and current investment, particularly for road and water infrastructure, where there is an estimated gap of around USD 177 billion and USD 49 billion respectively. The government as well as private institutions will need to mobilise taxes, savings, capital markets, and private equity to finance this multibillion-dollar infrastructure gap.

Despite requiring less significant amounts of investment compared to other sectors, railways have increasingly been a high priority for investment. Egypt has been working to upgrade its railway system with some capital investments from development banks and foreign contractors. For instance, in 2017, Thalis, the French group was awarded a EUR 109 million contract to renovate a signalling system on a 208-km route between Cairo and Alexandria, and the World Bank financed more than 90% of it (Oxford Business Group, 2017). Siemens was awarded a similar contract for upgrades along the Port Said and Benha route and between Zagazig and Abu Kebir. Other similar deals include a USD 600 million contract with China Railway Construction Corporation to renovate tracks in necessary areas and a USD 125 million loan to Egypt National Railways from the EBRD to hire a private company to procure more rolling stock and for the maintenance of its fleet (ibid). This investment can help bring the much needed expertise and enhance competition and innovation.

Figure 8.8. Egypt infrastructure: current trends and relative investment needs 2016-40

Source: Global Infrastructure Hub, Global Infrastructure Outlook 2014

Establishing an enabling environment for connectivity and infrastructure investments

The government’s goal of making infrastructure networks attractive for private participation is made easier when infrastructure policy priorities are fully embedded in the country’s economic development strategies and are supported by a clear regulatory and institutional environment. This helps to secure greater policy co-ordination and alignment across levels of government and to assure investors of the long-term political commitment to infrastructure development. This section will focus on Egypt’s current strategies for developing connectivity infrastructure and the accompanying regulations to achieve such strategies.

The infrastructure development strategy

Developing a strategy for connectivity infrastructure involves developing integrated strategies between trade, investment and infrastructure, dealing with the governance of infrastructure, and infrastructure financing. Integrated strategies should focus on including facilitation measures and multimodal infrastructure planning that can further facilitate trade and investment. At the same time, these strategies require overcoming a range of co-ordination and government capacity challenges, including: identifying infrastructure needs across sectors and regions; appropriate prioritisation of these projects; ensuring that they are affordable and represent value for money; preparing and procuring projects adequately; monitoring asset performance and properly scrutinising any necessary modification.

The Sustainable Development Strategy, Egypt Vision 2030 and the Transport Sector Master Plan

Infrastructure development is high on Egypt’s agenda. The Sustainable Development Strategy, Egypt Vision 2030 recognises infrastructure development as one of the priority areas to improve competitiveness, alongside developing human resources and skills to support the development of a modern industry and innovation, and improving governance to maximise the positive effects of reforms. In particular, the Economic Pillar of Egypt Vision 2030 incorporates infrastructure mega-projects. The most important mega-project is the expansion of the Suez Canal and the Development of the Suez Canal Economic Zone.

Other mega projects include constructing and rehabilitating 3 000 kilometres of roads; reclaiming one million acres of land; renewable energy projects; and fostering development in the Golden Triangle for touristic, industrial, commercial, and agricultural activities (Box 8.1). For transport projects, aims include achieving multi-modal transport chains and enhancing the role of the private sector in investing or participating in transport sector projects (Egypt Vision 2030, 2015).

The targets established in Egypt’s Vision 2030 are achieved through five-year sustainable development plans (2021-25 and 2026-30), where the government sets its work programme objectives, the budget expenditures as well as the economic and social reform programme priorities. The current plan, which exceptionally focuses on the period 2018-20, recognises investments in big national projects such as the national housing programme, the national road network and the expansion of subway systems as a strategic priority (Ministry of Planning, Monitoring and administrative Reform, 2017). For 2018, the government plans to spend around USD 36 billion, 60% of which would be injected into transport infrastructure, housing, public utilities, irrigation and electricity among other priority investments to achieve social and human development across the country. The budget also includes a 6% of investments in local development programmes, particularly targeting governorates of Upper Egypt, marginalised border zones, and squatter settlements (ibid).

Box 8.1. Selected Infrastructure Projects for Economic Development to 2030

The Egyptian government has introduced a list of mega projects that are expected to jumpstart the economic recovery and continue to facilitate internal and cross-border transportation and trade.

The Suez Canal Area Development Project

The Suez Canal Area Development Project stands as a high priority for Egypt. It comprises three main components aimed at reinforcing the position of the Suez Canal as a global maritime trade route, and exploiting its potential for investment attraction and export-oriented growth:

The “New Suez Canal”, involving a major expansion to increase capacity and allow ships to navigate in both directions at the same time, which will decrease waiting hours from 18 to 11 for most ships and double the capacity of the Canal from 49 to 97 ships a day. This project is expected to lead to enlarged transit capacity and increased industrial activity in the area, which will raise the international profile of Egypt as an international logistical and industrial hub.

The “East Port Said” development project, involving the construction of a 9,5-km side channel bypassing the Suez Canal entrance, port expansion works, a new industrial zone and logistics centre as well as four new East-West tunnels to increase cross-canal connectivity and link the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt’s mainland.

The “Suez Canal Economic Zone” (SCZone) established on 461 km² of land and six maritime ports strategically located along the international waterway with direct access to ports, to serve as an international logistics hub and areas for light, medium and heavy industry as well as commercial and residential developments.

Golden Triangle Project

This project entails the development of an area from the Eastern Desert between Qena, Al-Qusayr, and Safaga to the Red Sea Coast. The total land area of the Golden Triangle is 38 000 m2. The development plan would include initiating extraction activities in addition to manufacturing, trade, mining, infrastructure, ports, tourism and urban developments. The aim of the project is to attract more than USD 12.8 billion in investments and create around 400 000 job opportunities.

Damietta Logistical Centre

The project aims to transform the Damietta governorate into a global logistics centre for handling and storing grain and food commodities. This would be achieved through various works, including through (i) the establishment of two sea piers to receive ships carrying up to 150 000 tons of grain, (ii) the construction of five investment and industrial zones for grains and food commodities.

The New Capital

The project entails the construction of a new administrative city on a total area of 700 km2 between the East of Cairo and the Red Sea. The new city will host the Egyptian Parliament building, all ministries and government authorities, as well as all foreign embassies. As part of the project, 25 residential districts will also be built to house more than 25 million people, as well as an international airport, an electric train and solar farms on an area of 90 million2. With an estimated cost of USD 45 billion, the New Capital is considered the largest administrative city in the world.

National Roads Project

Launched in 2014, the National Roads Project includes 39 roads with a total length of 4 400 km at an investment of USD 2 billion. The focus is on linking remote areas to the national network, including Upper Egypt, the Sinai Peninsula and western Sahara. Through this work, the government has also placed an especially high priority on growth in associated areas such as export-oriented manufacturing and tourism.

One and a Half Million Feddan Project

This project entails the reclamation and development of one and a half million acres of undeveloped land to be used for agriculture in 11 areas in the Western Desert and Sinai. It is part of a larger scheme to reclaim a total of four million feddans to increase the agricultural land by 20% and create investment opportunities that create jobs and sustainable growth.

Major power generation projects

To increase its power generation capacity, Egypt also aims to build conventional and renewable power plants. A first project was already awarded to Germany’s Siemens to build a combined cycle power plant with a total capacity of 11 GW and install a wind-power with a capacity of 2 GW. The second project, awarded to Saudi ACWA Power Corporation and UAE Masdar Corporate, plans to build a 2.2 GW combined cycle power plant in western Damietta. Solar power stations expected to generate about 1.5 GW and 0.5 GW respectively are also in the pipeline.

Sources: Invest in Egypt, https://www.investinegypt.gov.eg/English; Country Report: On the Road to Recovery. Bank of Alexandria (2014); Suez Canal Authority Website, www.suezcanal.gov.eg; N Gage Consulting (2016), The Suez Canal Economic Zone: A Strategic Location and Modern Day Innovation

The Transport Master Plan 2027 (MINTS) is the government’s current strategy developed by the Ministry of Transportation for all transport sectors to achieve a multi-modal future with seamless connections. It aims to connect national, regional and gateway centres and create agglomerations of various activities that either generate or attract freight and passenger demands, serve as important distribution centres for hinterland activities, or provide international linkages. The required investments of around USD 15.5 billion between 2011 and 2027 would produce around USD 657 million of economic benefits by year 2027 with an economic internal rate of return of 17.8% (JICA, 2012). The MINTS is coordinated with other development plans introduced by other Ministries and entities such as the General Organization for Physical Planning, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Industry and Ministry of Tourism. The most important corridors that the MINTS aims to create are:

The Mediterranean Corridor linking Libya with Palestine via Marsa Matrouh, El Alamein, Greater Cairo (Northern segment of Cairo Outer Ring Road), Ismailia, and the Suez Canal-North Sinai Area.

The Intermodal Transport Corridor (ITC) linking the 6th of October Value Added Center with both the Alexandria-area seaports and Sokhna port. The corridor is expected to focus on the logistics of efficient freight flow. The ITC is seen as directly linking with the European Union “motorway of the sea” connecting Alexandria, Genoa and Koper ports.

The Red Sea Corridor parallels the Red Sea/Gulf of Suez between approximately Zafarana and Bernees, with a potential for strengthening the current linkage with Sudan. Key intermediate points are Gharib, Hurghada and Safaga.

The Upper Egypt Corridor paralleling the Nile River between Greater Cairo and Aswan, with a potential extension to create a new gateway to Sudan (Khartoum).

In the long term, the government is also seeking to transform the transport system through high-speed rail going at 300-350 km/h from Alexandria to Aswan through Cairo, Asyut and Luxor for a 1087-km line (Ministry of Transport, 2012). The line is expected to be built in three Phases (Phase I: Cairo – Alexandria, Phase II: Cairo – Luxor, and Phase III: Luxor – Aswan). However, talks with investors are still ongoing and no specific plans have been finalised (Oxford Business Group, 2017).

The recent industrialisation strategy also stresses the enabling role of infrastructure

Consonant with Egypt Vision 2030 is the government’s Industry and Trade Development Strategy 2016-2020, which recognises the critical importance of economic infrastructure to industrial development where the manufacturing sector plays a leading role. The strategy aims to increase the contribution of the industrial sector to the country’s GDP by 21% in 2020 and generate 3 million jobs, as well as to integrate SMEs into local and global supply chains and link them to major economic centres (MTI, 2017). The new strategy comes with a more integrated and targeted approach than the previous one. It recognises that achieving these objectives requires, among other things, the development of infrastructure and logistics, and linkages to roads and services (UNECA, 2015). These services serve not only as inputs in production sectors but also contribute to making Egyptian industrial output competitive in domestic, regional and international consumption markets. Under this strategy, a more integrated package of reforms focusing on trade, industry and infrastructure targeting sector-level development, land and industrial clusters supply, land and industrial clusters, and attractive investment incentives attractive to local and foreign investment (MTI, 2017).

The need for improved infrastructure planning and prioritisation

Securing the necessary resources to develop infrastructure will also require careful planning and prioritisation. Currently, numerous infrastructure priorities in Egypt are laid out in different strategies. Often, the allocation of budget for the national plans are an annual exercise, despite the fact that various ministries have to prepare their investment planning estimates over different time horizons such as the 5-year plans. The request for funds could also often exceed the funds available. There needs to be a path towards more clear and more predictable medium-term planning and funding allocations to increase stability for priority infrastructure projects and programmes and facilitate the co-ordination with donors. Currently, the government plans to strengthen its fiscal planning by introducing the medium-term expenditure framework, which will set multi-year expenditure ceilings by major spending categories, including infrastructure (IMF, 2018). Such planning of current and capital expenditure within a medium-term budget framework could also ensure that infrastructure investments are sustainable and that maintenance spending is fully taken into account (IMF, 2014).

The regulatory environment needs to be improved

In order for the private sector to be able to participate more in infrastructure delivery and services, an adequate policy environment is required, which involves removing administrative bottlenecks to investment and improving the regulatory environment. In recent years, the government has boosted efforts to build a credible environment for PPPs and has passed a number of reforms to create a more competitive and transparent legal PPP regime to attract qualified international and domestic investors.

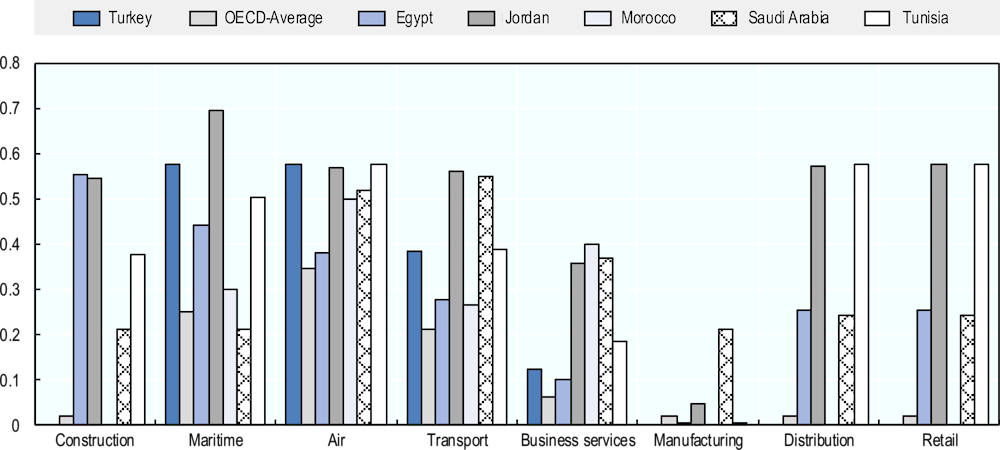

Removing regulatory barriers to investment into sectors that are relevant to connectivity

While Egypt is an open market to foreign investments overall, some restrictions are still relatively high compared to some of its regional peers on infrastructure services and the construction sector, which could partly explain the fragmented infrastructure sector, especially for ports. According to the OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, Egypt presents higher restrictions in the construction sector, maritime, air, and transport services than the OECD average and some of its peers such as Tunisia (Figure 8.9). Egypt’s Maritime Law 1 of 1998, for instance, only allows foreign investments in the form of joint venture companies in which foreign equity does not exceed 49% (OECD, 2017). The Construction Law 104 of 1992 also restricts foreign investment to joint-ventures in which foreign equity does not exceed 49%. In addition, foreign participation in electrical wiring and other building completion and finishing services is restricted to projects valued over USD 10 million (ibid). Such restrictions on investment could affect the competition in the market as well as the quality of infrastructure services that is needed to improve connectivity.

Removing restrictions on services sectors such as maritime air and transport, could also allow Egypt to enhance investments into high-quality logistics and move into higher-value added industries. In particular, improving the maritime services and related logistics could have a significant impact on enhancing FDI and creating jobs in the Egyptian economy (Ghoneim and Helmy, 2007).

Figure 8.9. OECD FDI Restrictiveness Index, Egypt (2017), (Closed=1; Open= 0)

Source: OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index database, http://www.oecd.org/investment/fdiindex.htm

Beyond removing restrictions, appropriate market-based mechanisms are also necessary to facilitate private investments

According to a Private Sector Diagnostics carried out by the EBRD, a number of sectors, notably transport and municipal infrastructure, are characterised by the absence of market-based mechanisms for the pricing and delivery of services (EBRD, 2017). The state, often through state-owned enterprises is the main administrator of transport and municipal infrastructure, leading to insufficient client orientation, maintenance and investment and therefore efficiency losses. Often, the regulated tariffs are low and below cost recovery levels. In an attempt to respond to such challenges, the government enacted a new law (law no 182/2018), which regulates public contracts and aims at improving the efficiency of government spending. Further reforms should move beyond tariffs and focus on governance to commercialise public service provision of infrastructure, which are critical to improve the operational and financial sustainability, facilitate greater private sector participation, unlock higher investment and deliver much-needed improvements in service quality.

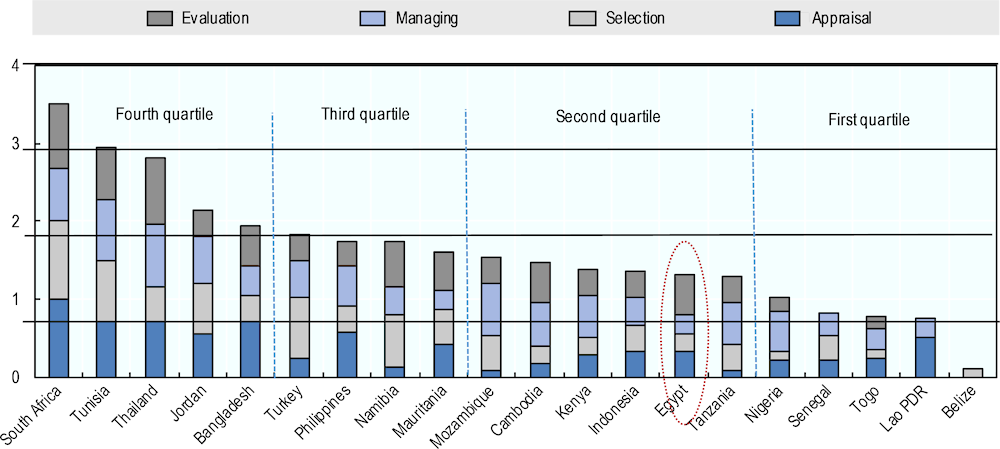

Reforms in public spending and transport regulation could also crowd in more efficient investments

Efficient public governance in infrastructure can have a significant effect in mobilising further private investments. Yet, poor project selection and implementation have historically led to low returns on public investment in many developing countries, including in Egypt (Dabla-Norris et al, 2012). The country faces surprisingly low returns on connectivity infrastructure investments, which calls for deeper reforms regarding the distribution of budget resources and accountability across ministries as well as the central and local governments (Abdellatif 2012). For example, infrastructure spending in Upper Egypt has historically been much less effective than anticipated since projects have too often been focused in the past on building new roads rather than maintaining existing ones (World Bank, 2009). This would require the project selection process to be guided by technical cost-benefit analysis and public spending be routinely evaluated and monitored.

The IMF Public Investment Management Index also indicates the need for more efficient public investment management in Egypt (IMF, 2011 and 2018). The Index, which assigns scores for the four phases of public investment management – project appraisal, selection and budgeting, implementation, and ex post evaluation – places Egypt in the second quartile, behind peers (Figure 8.10). The Index calls for better public governance across all areas, but more significantly in the selection and management phases. Improving these areas has also been a priority for the World Bank in Egypt, which has incorporated institutional changes in project design, including grievance mechanisms in large transport and energy projects in order to promote institutional forms and leverage further resources, including from the private sector (World Bank, 2015). Further addressing such dimensions in Egypt could be a starting point to identify areas of reforms and more nuanced policy diagnosis.

Egypt has a tradition of public-private partnership (PPP)-type financing structures such as build-operate-transfer (BOT). In 1869, it was the first country in the region to complete the famous concession of the Suez Canal through a BOT project. More recently, the government has been favouring modern PPPs as a potential financing solution for infrastructure projects. In 2006, a dedicated PPP Central Unit (PPPCU) was established within the Ministry of Finance to create a consistent framework for PPPs that applies across all sectors including social sectors such as education and health. The principal role of the PPP unit is to support contracting authorities in preparing, implementing and monitoring PPP projects.

In 2010, the government formalised the institutional and regulatory framework for PPPs by enacting a PPP law (67/2010) entitled “Promulgating the Law Regulating Partnership with the Private Sector in Infrastructure Projects, Services, and Public Utilities” based on the PPP model of the UK. The new PPP law allows the government to enter into PPP contracts with private entities, enabling the private sector to finance, construct, and operate large infrastructure projects and public utilities for contracts of up to 30 years (World Bank, 2011).

Figure 8.10. Public Investment Management Index scores in Egypt and selected countries

Source: IMF

The new legal framework for mobilising private investments in infrastructure brings an important financing solution for infrastructure projects

The 2010 PPP Law made official the establishment of the PPPCU. It provides that the Minister of Finance stipulates the structure of the unit, while the Executive Regulations of the Law determine the administrative and financial framework for its operation. In addition to the PPPCU, the law provides that a Supreme Committee for Public Private Partnership Affairs (the “PPP Supreme Committee”) shall be formed to be chaired by the prime minister and comprising the Ministers of Finance, Investment, Economic Development, Legal Affairs, Housing and Utilities and Transportation, as well as the Head of the PPPCU.

Recognised as the best PPP Law in the world of the year 2010 by the World Bank (Ministry of Finance, 2015), such an institutional and legal element for enhancing private participation in infrastructure represents a solid foundation on which to build a PPP programme. Despite such achievements, a number of challenges with the PPP mechanism remain, including the lack of clarity in allocating land for PPP projects, the absence of a long-term vision for prioritised PPP projects, lengthy procedures for the endorsement and implementation of PPP projects, and financial and technical limitations encountered in conducting necessary feasibility studies for PPP projects (GPEDC, 2018). Nonetheless, the government has started to take steps to tackle some of the abovementioned challenges.

Regarding land allocation for PPP projects, the PPPCU currently requires that any Public Authority shall have the legal documents of the land allocated for the project. The PPPCU is also performing due diligence with the assistance of the project transaction advisors before tendering process for any land proposed from any public authority to implement a PPP project. According to the Ministry of Finance, the PPPCU also engages closely with tendering authorities and governorates in order to choose the right land for PPP projects. A permanent joint committee was also formed, by virtue of a prime minister decree (605/2019), between the Ministers of Finance, Investment, Economic Development, Legal Affairs, Housing and Utilities and Transportation. The main purpose of this committee is to create a PPP pipeline of infrastructure projects for each line ministry and review available pre-feasibility studies to select projects that comply with the PPP criteria. This pipeline is then presented to the PPP Supreme Committee, which approves the initial structure of projects, timeline for feasibility studies, project preparation and tendering.

Despite government efforts, the uptake of public-private partnerships is currently low. While the current PPP framework is considered to be in line with international practices, only limited progress has been made in terms of preparing and implementing actual projects. Currently, there is a lack of track record, capacity and experience to develop PPPs (EBRD, 2017). Areas for improvement include strengthening the capacity of the PPPCU to allow it to prepare complex projects and further developing PPP financing schemes, particularly in the transport sector where they are not yet widely used. The OECD also finds that the PPPCU is understaffed and points to difficulties in securing PPP buy-in from line ministries. To address these issues, according to the Ministry of Finance, the PPPCU is currently working on hiring more staff and developing an organisational structure in line with international best practices.

Elsewhere in the region, Morocco and Jordan lack PPP units while in Tunisia both the Prime Minister’s Office and the Ministry of Finance have PPP units (OECD, 2014). In Egypt, the tendering process was disrupted by political instability during 2011-13, and only two hospitals have been built since then, but 14 projects worth over USD 4 billion are at various stages in the project cycle, including ports, roads, rail and ferries.

Moreover, the new PPP law does not replace the old laws that regulate concessions. Egypt finds itself in the position of having a general legal PPP framework coexisting with alternative channels for procuring infrastructure projects, such as the system of public economic entities, public utilities legislation and a number of sector specific or project specific laws (EBRD, 2011). As a result, administrative entities may still grant concessions, BOTs and BOOs (build-own-operate) based on the old scheme. Traditionally, these were granted under the general public utilities legislation (Law 129 of 1947 and Law 61 of 1958) or sector-specific laws (including electricity, specialised ports, airports, trains and roads) issued during 1990s when Egypt pursued economic liberalisation policies (Infitāḥ) to allow private sector provision of public services (Montaser et al, 2017). The old utilities legislation includes restrictive requirements, such as limits on the investor’s profit and setting a maximum duration for the concession of 30 years (EBRD, 2011). While these old laws may not generally apply on modern PPP projects, an assessment by the EBRD finds that the sector-specific approach may be used in the future, particularly for the power sector.

According to the Ministry of Finance, the government is in the process of addressing these issues by proposing new amendments in the PPP Law and reviewing the old sector-specific laws. Such amendments are currently being discussed in the parliament. Since the issuance of the PPP Law in 2010, the sector-specific laws were only used in tenders that cannot be tendered through the PPP programme. Most international investors have also requested to tender in infrastructure projects through the PPP Law, which is more structured, contains clear procurement procedures, and provides for investor protection.

Public support for PPPs is also low. With a past legacy of non-transparent privatisation processes that led to corruption, there is a traditional negative perception and lack of trust in the private sector, potentially including on cooperation projects between the private and public sectors (EBRD, 2011). This may also be due to the current lack of adequate community consultation to guide project selection and secure public support for PPP projects. According to the Ministry of Finance, this is partly due to the revolutions of 2011 and 2013, which created political and economic uncertainty, and led to a mixed understanding between privatisation and PPPs. It may also be due to the lack of adequate community consultations to guide project selection and secure public support for PPP projects. Yet, since 2014, PPPs are heavily supported at the political level and promoted more actively through media, awareness campaigns and conferences. Given the complex long-term nature of PPP projects, before the decision is made to launch a PPP project, the procuring authority should perform sufficient due diligence and rigorous community consultations. Ensuring responsible business conduct (see chapter on responsible business conduct) is also an important aspect of this process and could help mobilise more public support for infrastructure projects involving the private sector.

The legal framework for public procurement also needs to be updated and strengthened to increase tender participation and supplier diversity.

A more recent challenge for private sector engagement in infrastructure projects has been the fact that some well-developed infrastructure and energy projects involving the private sector have not proceeded as planned, sending a potentially confusing message to investors. This is partly because there is minimal online access to information on procurement opportunities, information on procurement decisions and debriefing procedures for unsuccessful decisions is unavailable, and there is no review and remedies mechanism to protect private sector suppliers competing for public tenders (EBRD, 2017). Overall, the legislative framework is outdated, and the public procurement process overregulated and bureaucratic. The Egyptian public procurement regulation4 dates back to policy standards from the 1980s.

Local practitioners in Egypt have not in the past considered the national public procurement legal framework to be clear, comprehensive, and conducive to a competitive procurement environment (EBRD, 2011). While open tenders are the default procurement method, which is a positive feature, the extensive use of direct contracting has limited competition in public tenders and works against efficient public spending (ibid). The assessment also reported gaps in transparency, integrity and accountability in public procurement processes. Enhancing the institutional framework for regulating the public procurement sector in Egypt would require making it more attractive to investors and increasing transparency with respect to the review and remedies processes.

The government has shown a preference for direct awards for public sector works, which are perceived to be faster in execution and lack complexities such as public procurement processes. Following the two revolutions, the government increased its role in infrastructure investments in the economy, which led in large part to an increased role of SOEs in building roads and other infrastructure projects.

Many of the projects are awarded to the National Service Projects Organisation, General Authority for Roads & Bridges and Land Transport, and Central agency for Reconstruction, which often serve as a contractor and typically awards subcontracts to private sector entities as part of this process, including to foreign investors. The 2016 Law on Public Procurement introduces procedures to enhance transparency and reduce discretion in public procurement, but the consistent application and enforcement of the law by the involved procurement entities is lacking (EBRD, 2017). The introduction of simplified procedures for small value contracts could also encourage the participation of local SMEs in public tenders (ibid).

Assessing value-for-money is crucial to make sure that investments benefit users and society at large.

Value for money can be defined as what a government considers to be an optimal combination of quantity, quality, features and price (i.e. cost), expected over the whole of the project’s lifetime. Even when public funds are not being used to finance infrastructure directly, value for money is important so that society does not overpay for services. Choosing the wrong projects diverts scarce resources from projects with potentially higher social returns. Therefore, value for money must be assessed over the lifecycle of an infrastructure asset, encompassing the construction, operating and maintenance phases. According to the EBRD, as there is no legal requirement in Egypt for the public entities to consider the whole life cycle costing of the goods or services procured, or seeking value for money, no appraisal was undertaken in the past on any other aspect of procured goods or services (EBRD, 2013). Moreover, contracting entities are = cost conscious and the lowest price is more frequently selected in practice than best value for money evaluation.

References

Abdellatif, L. (2012). “Understanding the Role of Public sector in Deepening Spatial Inequality in Egypt.” in Reshaping Egypt’s Economic Geography, vol. 2. (Washington, DC: World Bank).

Amereller (2018). Client Alert: Liberalization of Egypt’s Railway Sector. http://amereller.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/180423-Egypt-Rail-Privatization.pdf

Bank of Alexandria (2014). Egypt Country Report: On the Road to Recovery. https://www.alexbank.com/Cms_Data/Contents/AlexBank/Media/Publication/Egypt-Country-Report-2014.pdf