This chapter examines zone-based policies in Egypt. It provides an analysis of zones’ competitiveness and sustainability as well as of their strategic objectives, their distinct regulatory frameworks, and current policies to attract investment, boost export and foster linkages with the local economy. The chapter also presents evidence on zones’ contribution to foreign investment, export, and job creation. It offers some policy options to better align the development objectives of zones in Egypt with the government sustainable development priorities.

OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Egypt 2020

Chapter 5. Zone-based policies

Abstract

Summary and policy recommendations

Zones in Egypt have become central growth locomotives and, as in other emerging economies, they are home to substantial manufacturing activities. They have succeeded in attracting foreign investment, boosting participation in global value chains (GVCs) and creating jobs. By one estimate, they are home to at least one-tenth of FDI stock, generate almost half of non-oil exports and employ nearly 2% of the workforce. The characteristics and outcomes of each type of zone are nevertheless distinct, reflecting the specific development objectives of their corresponding legal and institutional frameworks.

Egypt has a longstanding history of relying on zones for development aims. The government established the first zone in 1974 in the area of Port Said, and has since overseen a proliferation of these areas. Currently, seven types of zones co-exist in Egypt: public or private free zones (FZs), investment zones, technological zones, special economic zones (SEZs), qualified economic zones (QIZs), and industrial zones. Most are governed by specific laws, overseen by different ministries, operate under distinct regulatory and institutional frameworks, provide different types of incentives to investors and often have overlapping goals. According to the government, the different zone types are meant to meet the different needs of investors and various types of investment. Nonetheless, the complex and overlapping landscape of zones has contributed to rivalry between government institutions over new zones management and expansion.

Zones’ development objectives and legal frameworks shape to a certain extent their key features and economic outcomes, but the patchwork of policies and regulations surrounding these frameworks makes it hard to assess the benefits and costs of each zone type for investment and wider economic development. Further clarity on each zone’s development aims, governance structure and legal and regulatory framework would help policymakers in better aligning zones’ strategic objectives with Egypt’s long-term development goals.

Several facts can be highlighted when comparing four out of the seven types of zones for which there is sufficient information:

Zones differ in the size of land allocated to them (Table 5.1). Due to their regional development objectives, SEZs in Egypt are radically different from the other types of zones. They are much larger – for instance, the surface area of the Suez Canal Special Economic Zone (SCZone) is ten times larger than all the free zones put together – and include ports as an integral part of the zone.

Zones differ in their geographical focus. FZs, investment zones and QIZs are located in the most advanced regions (Cairo, Alexandria and the Suez Canal). Industrial zones are in nearly all of the 27 governorates, including the investment-scarce southern and desert areas.

Each type of zone attract firms with different features (in terms of size, export potential, foreign-ownership, etc.). Around a thousand firms operate in FZs and a similar number in QIZs. FZs contribute more than QIZs to national exports but they generate a large trade deficit. Investment zones, which have cluster-specific development goals, are substantial job creators due to the relatively larger firms they host.

Zones in Egypt have comparable investment and export outcomes with those in other emerging countries but have a mixed record in generating value-added, fostering innovation, and supporting diversification and sustainable development countrywide. More problematic, they may be impeding fair competition between firms inside and outside of zones, at the risk of creating economic enclaves. They also impose a certain cost on government revenues, as the incentives granted to firms reduce the fiscal base (IMF, 2017). In addition, while foreign-owned businesses take advantage of such tax incentives, they often limit their reliance on local providers of goods and services in order to maintain some degree of locational mobility (Azmeh and Nadvi, 2014). Ties between zones and the local economy may be even narrower in the lower value-added segments of sectors such as textiles and clothing. Linkages between multinationals in Egyptian zones and local suppliers do sometimes exist, but policymakers could support their extension to further rely on higher-skilled labour or on R&D agreements.

Table 5.1. Key features of zones in Egypt in 2018

|

Zone type |

Public and private Free zone |

Investment Zone |

Special Economic Zone |

Qualified Industrial Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year of creation |

1971 |

2008 |

2002 |

2004 |

|

Size (km2) |

48.6 |

12.7 |

9’761 |

n.a |

|

# Active zones |

9 public/208 private |

18 |

2 |

17 |

|

# of Firms |

1’091 |

300 |

n.a |

1’030 |

|

# governorates (out of 27) |

9 |

7 |

5 |

n.a |

|

# of employees |

190’035 |

59’000 |

n.a |

150’000 |

|

Avg. exports 2013-18 (% of national non-oil export)* |

34.2 |

n.a |

n.a |

5.4 |

|

Avg. imports 2013-18 (% zone trade) |

48 |

n.a |

n.a |

9.5 |

* Excluding sales on the domestic market; Data is for 2018 or last available year. Industrial zones and technology zones are not included.

Source: OECD based on Central Bank of Egypt, QIZ Unit Bulletin, GAFI, and WTO (2018).

Zones in Egypt have comparable investment and export outcomes with those in other emerging countries but have a mixed record in generating value-added, fostering innovation, and supporting diversification and sustainable development countrywide. More problematic, they may be impeding fair competition between firms inside and outside of zones, at the risk of creating economic enclaves. They also impose a certain cost on government revenues, as the incentives granted to firms reduce the fiscal base (IMF, 2017). In addition, while foreign-owned businesses take advantage of such tax incentives, they often limit their reliance on local providers of goods and services in order to maintain some degree of locational mobility (Azmeh and Nadvi, 2014). Ties between zones and the local economy may be even narrower in the lower value-added segments of sectors such as textiles and clothing. Linkages between multinationals in Egyptian zones and local suppliers do sometimes exist, but policymakers could support their extension to further rely on higher-skilled labour or on R&D agreements.

Policy recommendations

Better align the development objectives of existing zones in Egypt with national and local strategies as well as investment and trade goals. Egypt Vision 2030 calls for “achieving coherence and integration among industrial and free zones, and domestic, regional, and global value chains”. To succeed, Egypt needs to develop realistic and coherent objectives for zones that are aligned with national, governorate and sectoral development priorities, including Egypt Vision 2030, the national investment plan, the Trade and Industry Development Strategy 2016-2020, the national SME and Export Development Strategies, and forthcoming decentralisation reforms. The policy dialogue around such objectives (and the actions needed to reach them) should involve a multitude of stakeholders, including GAFI, the QIZ Unit, the Industrial Development Agency, the Export Promotion Agency, the recently created SME agency, governorates, and civil society.

Assess the longer-term benefits and costs of creating new zones, or expanding existing ones, for sustainable development and economic welfare. The proliferation of zones, created under distinct special regimes and managed by different public entities, without an ex ante assessment, may result in weak development outcomes (e.g. low shares of exports) or, more problematically, to undesired consequences (e.g. distorting competition with the inland regime). Estimating the expected impact of new zones in Egypt should take into consideration the specificities of the domestic economic environment, including the level of import protection or the complexity of customs procedures.

Balance the objective of expanding zone activities with a transparent and sequenced plan to level the playing field between the special and the inland investment regimes. The government should gradually eliminate some of the most distortive tax incentives granted in the zones, particularly the exemption from corporate income tax in FZs, in line with the recommendations of chapter 6 and the IMF Article IV. The government should consider setting up zones with a less distortive impact on the economy, i.e. with special regimes that give investors less differentiated treatment with respect to tax incentives. In parallel, Egypt should continue to improve the broader business climate by lowering import and export barriers so as to reduce the incentives gap between the inland and the special regimes.

Promote private investment in higher value-added segments of the manufacturing sector to unlock zones’ export competitiveness potential. This includes promoting investment in capital-intensive, upstream stages of the textile and clothing, food, and chemicals supply chains to modernise their production capabilities. To move towards a cluster-based strategy, the government could support investments aimed at replacing ageing technology in state-owned enterprises, from which downstream clothing firms in zones source their inputs. This would prevent an increase in production costs throughout the supply chain that affects smaller establishments the most. Furthermore, Egypt could align zone-specific and sector-specific objectives to attract investment in higher value-added segments of the logistics, food, chemicals and automotive sectors. It could leverage the advantage of QIZs related to US duty-free market access beyond textile products to also attract investors into the food and chemicals sectors.

Better use zones as a tool to bridge investment and regional development policies. It is crucial to incorporate the investment aims of the different zones into a regional/governorate development strategy that includes not only the provision of various duty exemptions and other incentives to attract investors, but also a comprehensive reform programme to boost business linkages. Cost-based incentives should be favoured over compulsory linkage requirements to strengthen linkages between foreign MNEs in special regimes and suppliers located in the inland regime. Authorities at the national and zone level could better co-ordinate their efforts to promote the different tools incentivising linkages. The government could also support strengthening local firms’ absorptive capacity through skills development training, tailored business development services and partnerships with education entities.

Clarify zones’ institutional and regulatory framework to ensure a level playing field between public and private investors. Zone authorities in Egypt often have the mandate to be both regulators and developers. The institutional framework should therefore ensure that private and public developers are eligible for the same benefits provided by zones. These benefits should be fully defined in the legislation and awarded based on clear, objective and transparent criteria. In the case of new zones, the government should examine how to clearly separate these regulatory and development roles to improve the effectiveness and transparency of zone administration.

More systematically involve the private sector, local governorates and other relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process of zone authorities. This measure is necessary to build trust and ensure that there is no bias in the decisions of the boards of zones, particularly in light of the limited land available in some zones with many investors already present. The board could include representatives from all governorates within the zone (or otherwise have transparent and clear rules on how governors rotate to sit on the board), as well as private investors, private developers and business representatives, such as SME associations.

Ensure that investors in zones comply with responsible business conduct (RBC) standards. Adopt RBC policies to ensure that health, safety, labour and environmental norms in zones are in line with national and international standards. Monitor the impact of more flexible labour regulations on the local labour market in zones, particularly in SEZs as they enjoy more flexible labour and social rules. The more flexible regulations in zones should be designed for a temporary period and closely monitored through regulatory impact assessment tools. Zone authorities should put in place strong and independent institutional tools to monitor labour and environmental rights.

Provide better statistics on zones to support evidence-based policy making. More granular statistics on exports, investment and jobs in zones are needed to disentangle the contribution of each special regime. The availability of firm-level data, perhaps through annual surveys, would allow authorities to track business features and performance, measure zones’ fiscal costs and benefits and, for example, monitor smuggling operations. Such data would offer more room for designing more targeted, evidence-based policies to steer zone outcomes towards their development goals. The statistical bulletin provided by the QIZ Unit could be an initial example to build on.

Overview of the objectives and regulatory frameworks of zones

Egypt opted for the establishment of zones to meet various development objectives, from job creation and increasing export and budget earnings, to attracting investment, especially FDI. Zone-based policies are increasingly common in many developing economies. They can help partly to neutralise the effects of an otherwise less favourable business climate by offering differentiated treatment or services to investors, such as through tax or administrative incentives or better infrastructure than in the rest of the country. The creation of zones is often a reflection of the need to offset a negative impact of stringent import protection on trade or challenges in accessing secured land under the inland regime.

Aligning the objectives of each special investment regime in Egypt with national development goals is more than ever a pressing, yet challenging, policy priority. In recent years the government has based the overall development strategy on the multiplication of both the types of special investment regimes and the number of zones (Table 5.2). The Sustainable Development Strategy: Egypt 2030 Vision and other sectoral or ministerial strategies all have an objective of establishing new zones in the next decade or expanding existing ones to support industrialisation, innovation and exports.

Table 5.2. Tracking Zones in Egypt

|

Zone type |

Name/location of the zone |

|---|---|

|

Free Zones |

Alexandria; Damietta; Ismailia; Keft (Qena); Media Production City (Giza); Nasr City and Badr city (Cairo); East Port Said Public Free Zones; Port Said; Shebin El Kom (Monufia); and Suez ; Minya and Nuibaa; and South Sinai and Aswan. Private Free zones are spread around the country. |

|

Investment Zones |

CBC Egypt for Industrial Development (building materials); Giza; Polaris International Industrial Park (textiles); Giza; the Industrial Development Group (automotive-related industries); Giza; Pyramids Industrial Parks (engineering industries); Sharqiya; Al-Tajamouat Industrial Park (textiles); Sharqiya; Meet Ghamr (SME); Dakahlia; Al-Saf (SME); Giza; City of Scientific Research and Technology Applications (nanotechnology and biotechnology); Alexandria; Cairo University (higher education and scientific research); Giza; Ain Shams University (higher education and scientific research); Qalyubiya; Faiyum University (higher education and scientific research); Faiyum. |

|

Special Economic Zones |

The Suez Canal Economic Zone (SCZone); the Golden Triangle Economic Zone (GTZone). |

|

Qualified Industrial Zones |

Alexandria governorate; Dakahleya Governorate; Damietta Governorate; Gharbeya Governorat; Monofeya Governorate; Kafr El-Sheikh Governorate; Damanhour City; Kafr El-Dawar City; Ismailia Governorate; Port Said Governorate; Suez Governorate; Beni Suif Governorate; Al Minya Governorate. |

Note: Industrial Zones and Technology Zones are not covered due to limited information.

Source: OECD based on Government websites and documents.

Meanwhile, Vision 2030 calls also for “achieving coherence and integration among industrial and free zones, and domestic, regional, and global value chains” (Economic Pillar, pp. 42). This proliferation of zones, created by different institutions, without a thorough ex ante assessment, may prevent them from achieving their objectives or, even worse, lead to undesired outcomes. Evidence from other countries is not conclusive on the estimated effect of introducing such regimes. Their expected benefits in terms of economic development are not necessarily positive or automatic but are greatly contingent on the local business environment, particularly on the stringency of import barriers: zones’ export potential is higher the lower are importing costs compared to the inland regime (Davies and Mazhikeyev, 2015).

In terms of legal framework, the 2017 Investment Law defines four special investment regimes: public free zones, private free zones, investment zones and technical zones (Table 5.3). SEZs are governed by a stand-alone SEZ Law. QIZs do not on their own constitute an investment regime and can fall under the jurisdiction of the inland or special investment regimes. They are regulated through a Protocol signed in 2004 between Egypt, the United States and Israel. Industrial zones are governed exclusively by the inland investment regime and therefore do not provide firms with specific custom exemptions or treatment, unlike the special investment regimes. Other chapters of the review provide an in-depth assessment of dispute settlement mechanisms and tax incentives in special investment regimes.

Table 5.3. Differences between regulatory regimes of Zones in Egypt

|

|

Public and Private Free zones |

Investment and Tech Zones |

Special Economic Zones |

Qualified Industrial Zones |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Law |

Law No. 72/2017 on Investment |

Law No. 72/2017 on Investment |

Law No. 83/2002 “Economic Zones of Special Nature Law” Amended by Law No. 27/2015 |

Protocol between Egypt, Israel and the U.S |

|

Executive regulation |

Prime Minister decree No. 2310/2017 |

Prime Minister decree No. 2310/2017 |

Prime Minister decree No. 1625/2002 |

-- |

|

Competent authorities |

Board of the Zone Authority, GAFI |

Board of the Zone Authority, GAFI Competent Minister pursuant to the speciality of the Zone |

Board of the SEZ Authority |

QIZ Unit, Ministry of Industry and Trade |

|

Dispute settlement mechanisms |

National Courts; GAFI Dispute Settlement Centre 3 Ministerial Committees The Egyptian Arbitration and Mediation Centre Private arbitration (domestic and international) |

National Courts; GAFI Dispute Settlement Centre 3 Ministerial Committees The Egyptian Arbitration and Mediation Centre Private arbitration(domestic and international) |

Zone Dispute Settlement Centre (yet to be established) National Courts Private arbitration (domestic and international). |

National Courts Private arbitration (domestic and international) |

|

Tax incentives* |

Corporate income tax: 0% VAT: 0% |

Corporate income tax: 22.5% VAT: 14% |

Corporate tax: 22.5%** VAT: 0% |

Corporate tax: 22.5% VAT: 14% |

|

Export incentives/requirement |

No customs duties and procedures. Minimum export for public free zones projects fixed by a technical committee. Minimum of 80% of export for private free zone projects. |

Tech zone: No customs duties on intermediate inputs. |

No customs duties |

No customs duties and procedures; Duty-free access to U.S market & no quota limit; 35% local content requirement, of which a minimum of 10.5% must be Israeli inputs. |

* Goods and services exported are exempted from VAT; ** 10% if created before the 2015 amendment. Industrial Zones are not represented as they are governed exclusively by the inland investment regime.

Source: OECD based on OECD (2017), the QIZ Unit Bulletin, and WTO (2018).

The institutional landscape governing zones in Egypt consists of a plethora of public entities at both the national and local levels. Ensuring smooth and effective institutional co-ordination is therefore an essential, albeit challenging task. At the national level, FZs are regulated and overseen by GAFI. In contrast, QIZs and industrial zones fall under the authority of the Ministry of Industry and Trade and the Industrial Development Authority (IDA). In light of their wider mandate and higher level of independence, SEZs report directly to the Prime Minister. At the sub-national level, each zone type is administered by an authority, with a board of directors reporting to the national entity in charge of the zone management. Many other national and sub-national bodies are also involved in zone governance, such as specific ministries in the case of investment and technology zones, and authorities at the governorate and city level.

Box 5.1. Allocation of roles and responsibilities in zones in Southeast Asia

Administrating a zone usually requires multiple bodies at different institutional levels. In general, the government assigns regulatory responsibilities to a public authority administrating the zone. The regulator usually adopts and implements regulations within the zone, designates developers, allocates land, promotes the zone, provides business facilitation services and monitors compliance. Although some functions are distinct for different parties, in practice there is often an overlap of functions, especially at the regulatory and development levels. In some zones, the authority is also a developer, i.e. it is in charge of developing and managing the zone. Often, the authority also holds equity shares in private development companies.

According to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Guidelines for SEZ Development and Cooperation, which serve as a reference of best practices for ASEAN countries, there are several roles that should be separated in the institutional framework:

Government: Provides strategic guidance through the establishment of zones in specific areas. It adopts a legal framework for zones, creates the zone authority and appoints the zone managers. The government can also conduct initial feasibility studies in order to develop basic infrastructure. The government can participate in workers’ training in order to ensure the quality of the workforce.

Regulator: Zones are usually governed by a regulator, appointed by the government, responsible for adopting the regulations applied within the zone. Thus, the regulator also monitors the compliance with these rules and imposes penalties in case of breach of such regulations. The regulator should provide services – such as licensing and registration – to investors. The regulating entity often selects the developers and operators in the zone but in some cases, the regulator may also act as a developer.

Developer: The developer can be a private investor – usually a real estate developer – a public company or a company established through a PPP with responsibility for building and maintaining infrastructure within the zone.

Operator: The operator is the entity responsible for managing the zone’s day-to-day operations. It manages rentals but also ensures the provision of basic utilities (gas, electricity, water, etc.), offers diverse services and is in charge of promoting the zone. Private companies often take over operation and promotion of the zone. Financed by zone user fees, operators maintain infrastructure, recruit zone tenants, enforce rules, and, in some cases, carry out administrative services.

Users or tenants: Users, or resident firms, set up operations in the zone. Some zone users are “anchor tenants”, or large firms which, in exchange for concessions, agree to operate in the zone and help attract other, smaller tenants.

Source: OECD (2017) and ASEAN (2016), Guidelines for Special Economic Zones Development and Collaboration.

The organisational prerogatives given to zone authorities vary from one zone type to another. For instance, the SEZ authority is mandated with developing internal regulations and monitoring firms’ compliance. At the same time, the authority can assign a developer (either public or private) to execute and manage the land in a delimited area of the zone and conduct promotion activities within this area. The authority can fully or partly own the developer, mainly by allocating a land parcel in return for a usufruct fee. It also has the ability to provide incentives to developers such as endowments, grants, loans and credit facilities. The overlapping mandates held by zone authorities may create confusion as well as possible conflicts of interest as the (public) developer is in charge of regulating itself. Such a framework negatively affects private investors’ perception of a transparent and competition-friendly business environment (Farole and Kweka, 2011). The multiple roles of zone authorities also cast doubts on their capacity to effectively administer the zone.

Allocating clear and transparent roles and responsibilities among the authorities administrating zones would improve their efficiency and attractiveness to investors. More specifically, organisational frameworks should as much as possible separate the roles of zone regulator from those of zone developer, owner and operator (Box 5.1). For all zones in Egypt, legislation should therefore ensure that privately-owned developers are eligible for the same full benefits as public developers and that the criteria to obtain these benefits are clear and transparent. Such mechanisms are key to guarantee that public and private developers are competing on an equal basis.

Clarifying responsibilities of zone administrators is a pressing challenge given that Egypt intends to set up in new public FZs under a public-private partnership (PPP) model. Outsourcing the development of the zone to private developers may attract higher levels of investment: private developers tend to offer better quality services because of the self-interest they have in engaging in implicit investment promotion (Moran, 2011). Beyond helping to create a competition-friendly climate, the division of roles also allows for increased efficiency, as the regulator can concentrate on strategic matters while the private developer can focus on performance and commercial outcomes. For instance, in the Mactan SEZ in Philippines, the Philippine Economic Zone Authority employed a private company to develop and operate a zone owned by the Mactan-Cebu International Airport Authority. The private company (the developer) earned fees from investors that settled in the Zone; an incentive for the company to attract new investors (Moran, 2011).

Public and private free zones

Public and private FZs are regulated by Investment Law (72/2017) and the Executive Regulations of the Prime Minister decree (2310/2017). The oldest Egyptian special regime, the public FZ regime, is to a certain extent a typical free trade zone (FTZ), whose primary goal is to support imports and exports by removing customs duties, corporate income tax and VAT (Tables 5.3 and 5.4).1 Public FZs in Egypt, as FTZs elsewhere, are delimited areas offering warehousing, storage and other services. They also host light manufacturing industries (i.e. limited transformation), producing goods mainly for foreign markets. Beyond boosting trade, Egypt also set up public FZs with the objective of increasing foreign currency reserves.

The private FZ status was removed from the Presidential Decree 17 of 2015, issued to introduce amendments to the old Investment Law No. 8 of 1997, before being restored in the 2017 revision. Private FZs grant the same fiscal incentives as public FZs, but their development objectives differ from a typical FTZ as they aim to attract export-oriented mega-projects, mostly in the manufacturing sector. Often, the mega-project is itself one private FZ that can be located in any area considered as appropriate to conduct the business. They are therefore closer in type to a single factory export processing zone (EPZ) (Table 5.4). Other countries, such as Tunisia, have comparable special regimes where incentives are granted to firms based on their export share requirements (ESR) rather than on their location in a specific fenced-in area.2

Table 5.4. General typology of zones

|

Type of zone |

Development objectives |

Description |

Markets |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Free trade zone |

Supporting trade |

Also known as commercial free zones, these are clearly delimited areas (fenced-in, duty-free), offering warehousing, storage and other services aimed at boosting import-export. |

Domestic, re-export |

|

Export processing zones (EPZs) |

Export and manufacturing |

Industrial clusters offering incentives and facilitation of manufacturing and other activities mostly export-oriented. |

Mostly export |

|

Hybrid EPZs |

Export and manufacturing |

Sub-divided zones with one part open to all industries regardless of their export orientation, and another specifically designed for export-oriented firms. |

Export and domestic market |

|

Freeport |

Integrated (regional) development |

Large territories accommodating all types of activities, providing broad incentives and benefits. Can also include residents on the site. |

Domestic, internal and export markets |

|

Enterprise zones |

Urban revitalisation |

Aimed at revitalising distressed urban and rural areas, enterprise zones mostly flourish in developed countries and are characterised by the provision of tax incentives and financial grants. |

Domestic |

|

Single factory EPZ |

Export manufacturing |

Incentives are provided to a specific enterprise, rather than to a geographic location. |

Export market |

Source: Adapted from OECD (2017) and FIAS (2008), Special Economic Zones: Performance, Lessons Learned, and Implications for Zone Development, World Bank.

The current investment law makes some significant changes to the FZ regime, limiting the scope of industries that can qualify. To put this new approach into practice, the Law lists several activities that cannot be pursued in a FZ, e.g. petroleum refining, steel, natural gas liquefaction and transport, industries that require high energy consumption, and alcoholic beverages industries (article 34). In case of an investment dispute occurring within such zones, investors can refer to national courts, Dispute Resolution Ministerial Committees, GAFI’s Dispute Settlement Centre or the Egyptian Arbitration and Mediation Centre. Investors may also choose to use private arbitration centres (Table 5.3). Investors operating in FZs therefore have as many options to access alternative dispute resolution mechanisms as investors located outside of the zones.

The criteria for establishing a project under the public and private FZ regime are defined by the investment law and corresponding executive regulations. The Investment Law indicates that projects in public FZs are mainly oriented towards exporting.3 The existing regulation does not specify the ESR but rather states that the minister of investment, in agreement with the minister of trade and industry affairs, sets project obligations in terms of export rates.4 The conditions for establishing a private FZ, as defined in the legislation, are more stringent and more specific.5 These conditions include:

No appropriate location for the project inside a public FZ;

The geographical location is a detrimental factor for the viability of the project;

Exports should be no less than 80% (this condition is excluded in the strategic projects of special importance);

Minimum capital of USD 10 million;

The local content may not be less than 30% ;

Permanent employment should not be lower than 500 workers.

The decision-making process of boards of zones could benefit from procedures that are more transparent. In the case of the FZ regime, the board is composed of the zone governor, the city mayor (as chairman of the board), three private sector representatives (investors in the zone) and two employees representatives (from the zone). The chairman has the mandate to issue approvals on projects within the zone (or within private FZs located in their geographic area), in addition to being responsible for issuing licences to authorise these projects. The Board determines the size of the land lot to be allocated to investors, a crucial decision in light of the high demand and limited space available within some zones. A technical committee for FZs affairs, located at GAFI’s headquarters, studies the applications for setting up the projects and is in charge of approving them. If dismissed, it is not clear if the rejected investor can appeal the decision.6

Investment and technology zones

Egypt introduced investment zones in 2008 and technology zones in 2017. Both are regulated by the 2017 Investment Law and Prime Minister decree No. 2310/2017. They are somewhat similar in their design to EPZs as they aim to create, in an area with defined borders, sector-specific clusters (Table 5.4). In contrast with EPZs set up elsewhere, investment zones and technology zones in Egypt are home to services projects and are intended to serve both foreign and domestic markets. For instance, projects operating within investment and technology zones are not required to export (part of) their production, as is the case under the FZ regime.

The investment law defines investment zones as a special regime that grants administrative facilitation (e.g. exemption from contracts for land registration). Technological zones are similar to the investment zones in that firms benefit from administrative facilitation, but they also qualify for additional incentives such as exemption from taxes and customs duties on the imported machinery and tools required for establishing the project. Because of their sector-specific nature, these two types of zones are established by the ministry that is overseeing the sector (e.g. the Minister of Communications, Information and Technology is the authority in charge of establishing ICT zones).

Investment zones can be established in various fields, through a decree from the prime minister. These zones cover services clusters that are not prioritised by FZs, such as education, scientific research and tourism infrastructure. For instance, Cairo University and Cairo Airport are under this regime. Technology zones in particular aim to promote activities in the fields of technology, including manufacturing and developing electronics, programming, and technological education. In contrast with the FZ regime, the establishment, management and promotion of an investment zone or technological zone are undertaken by a developer, whether public or private.

Special economic zones

Egypt introduced special economic zones (SEZ) with the enactment of the Law No. 83/2002 “Economic Zones of Special Nature Law”, amended by Law No. 27/2015. The SEZ Law applies to the zones created by the presidency. The country’s first SEZ was developed in 2003, in the northwest Gulf of Suez. The two presidential decrees No. 330/2015 and No. 341 of 2017 declared respectively the areas adjacent to the Suez Canal and the lands located in the Golden Triangle area in Upper Egypt as SEZs (hereafter, referred to as the SCZone and GTZone).

The SEZ regime differs very significantly in its features and objectives from the other zone regimes in Egypt and most clearly resembles what the World Bank classifies as freeports: usually designed as liberalised platforms for diversified economic growth that not only could, but should spill-over into the national economy (Table 5.4). Ranging in size from single digits to thousands of square kilometres, freeports are generally large, usually located at seaports, with a broad range of permissible activities, and exemptions from customs duties for all types of merchandise. As in other SEZ regimes around the world, companies in Egyptian SEZs receive full access to the domestic market upon payment of required import duties and taxes, unlike the FZ regime or other regimes that have export-related requirements.

An important feature of freeports is that they often include residents on the site, which is the case of SEZs in Egypt, making them regional development areas. Similar to the Chinese freeports (e.g. Shenzhen), commonly cited as examples for these types of zones, Egyptian SEZs intend to serve as pilot regions or laboratories for experimentation with different policies. While freeports and similar types of SEZs generally occupy an area around a single port city or province, Egypt’s two SEZs, the SCZone and GTZone, span very wide territories covering several different governorates and major port cities. The SCZone is also home to a large population. Despite unique locational features, the sheer size and scope of the two Egyptian SEZs may constitute a challenge in itself (OECD, 2017).

Compared to the FZ regime as defined in the 2017 Investment Law, the SEZ regime is characterised by a higher degree of institutional and regulatory insularity. The Law contains provisions related to business facilitation, through the establishment of a zone authority exclusively responsible for zone regulation and management. It also addresses issues regarding privileges, exemptions and guarantees granted to investors, and provides for the internal organisation as well as, in contrast with the other special regimes, a dispute settlement centre for the SEZ, which has not yet been established (Table 5.3). In light of the multiple mechanisms for dispute settlements that already exist in the country, creating a dedicated dispute settlement centre in SEZs may be counterproductive.7

SEZs are overseen by an authority that reports directly to the prime minister. In the context of the Suez Canal area, the SEZ Authority acts as a near-autonomous entity, with the capacity to create a special regime applicable to a delimited territory and hence to introduce its own regulations, including in areas such as labour and social protection. The rationale behind the empowerment of the authority is to enable it to create a framework within the zone that provides stronger protections to investors against political and legislative instability, as well as to experiment with policies that could be extended to the national level.

A variety of other actors contribute to the wider management of the Suez Canal area, beginning with the Suez Canal Authority (SCA), the entity that manages, operates, uses, and maintains the Suez Canal. The SCA issues and enforces the rules of navigation in the Canal and other rules and regulations that provide for a well and orderly run canal. Line ministries, port authorities, state-owned companies, regulatory agencies, and governorates authorities are involved in the management and operations of the territory declared by the government as a SEZ.

The decision-making process of boards of SEZs could be reinforced by involving a wider variety of stakeholders. Strengthening the decision-making process is important in the case of the newly created SEZs. The institutional framework governing SEZs has been substantially revamped with the enactment of the 2015 SEZ Law and amending regulations, aimed at streamlining the allocation of powers and mandates for the governance of the Zone. According to the amended 2015 SEZ Law, the board shall be composed of the chairman, deputy chairmen, two ministers and one governor as well as five financial and legal experts. According to the SCZone authority, there are systematic hearings and open discussions with investors and developers but they are not mandatory (OECD, 2017). Likewise, Law No. 27/2015 and Prime Ministerial Decree No. 3300 of 2015 stipulate the presence of three representatives from development companies and investors on the boards, but it is not clear at this point which role private sector representatives play during the meetings of the boards.

The amended SEZ text also reduces the number of permanent seats allocated to representatives from governorates compared to the 2002 SEZ Law. This governance change may affect the credibility and transparency of board decisions, which has the mandate to grant specific incentives (e.g. allowed ratio of foreign workers within a company) on a discretionary basis. Greater involvement of the private sector and local partners (e.g. sub-national ministerial offices, governorates, municipalities, local business associations) in the oversight of SEZ activities is necessary to ensure that there is no bias in the decisions of the authority. For instance, in the Philippines, the Subic Bay Metropolitan Authority is composed of 15 members, including representatives of all local governments that are part of the Subic Bay Freeport and five representatives from the private sector.

Qualified Industrial Zones

Qualified industrial zones (QIZs) can be considered as a type of zone that is rather unique in both design and objectives. QIZs are regulated through a protocol signed in 2004 between Egypt, the United States and Israel. The protocol allows products jointly manufactured by Egypt and Israel duty-free access to the US market.8 Jordan signed the same protocol as Egypt in 1997. Investment in a QIZ can fall under the jurisdiction either of the inland investment regime or of a special regime, depending on where the QIZ is located. In the latter case, it combines the privileges associated with QIZ status and those offered by the special investment regime. In terms of development objectives, QIZs fit best with the definition of EPZs (Table 5.4). They are fenced-in areas, confined to boosting exports of processed manufacturing goods, essentially textiles and clothing, to the United States. Ultimately, the QIZ protocol also aims to increase trade between Egypt and Israel, thus contributing to further bilateral cooperation and stability in the region.

To be eligible for QIZ status, the protocol requires firms to source 35% of their content locally, of which a minimum of 10.5% must be Israeli inputs. Recently, Egypt negotiated with the US the possibility to lower the Israeli component to 8%, as applied in the case of Jordanian QIZs, and to expand the scope of the protocol to cover other sectors (e.g. technology companies). Firms operating within the boundaries of a QIZ are free to export within or outside the QIZ framework (i.e. to the US or elsewhere). The QIZ Unit operates under the auspices of the Ministry of Trade and Industry and serves as an executive and technical support unit, as well as an information centre for local and foreign businesses interested in investing under the terms of the QIZ protocol.

Industrial zones

Industrial zones aim to boost industrial development throughout the country by facilitating investors’ access to industrial land, including in less developed areas. Contrary to the other types of zone in Egypt, they are not governed by a special legal framework or a protocol and do not offer any tax incentives or duty-free market access. Industrial zones that are confined to the boundaries of one of the special regimes grant the investor the privileges offered by the regime. The Industrial Development Authority (IDA), created in 2005, is in charge of managing the industrial zones. It has the exclusive authority over industrial land, including the development of utilities and infrastructure and is in charge of putting the land up for bids (WTO, 2018). IDA also is responsible for delivering licences for any industrial project in the country, including in FZs or in investment zones, with the exception of SEZs.9

The central role of zones in advancing sustainable development

Zones-based policies have succeeded, to some extent, in boosting exports and attracting foreign investment and jobs to Egypt. Combined, FZs and investment zones are home to one-tenth of national FDI stock; FZs and QIZs generate around half of the country’s non-oil exports; and FZs, investment zones, and QIZs employ nearly 2% of the workforce. In Viet Nam, for instance, zones also contribute to exports and jobs in a similar proportion; although they are also home to half of the country’s FDI stock (Box 5.2).

The lack of data makes it a daunting task to gauge zones’ benefits and costs on the Egyptian economy. As in other zone-intensive emerging countries, zones tend to have a mixed record in generating value-added, fostering innovation, and supporting sustainable development more broadly. More problematic, they may be impeding fair competition between firms inside and outside of zones, and risk creating economic enclaves. They also bear a certain cost on government revenues as the incentives, particularly corporate income tax holidays, granted to firms reduce the fiscal base (IMF, 2017).

Even if foreign-owned businesses move to exploit zone-based tax incentives in Egypt, they often are poorly rooted in the local economy (with limited production sites) in order to relocate more easily their activities to another country with more lucrative conditions (Azmeh and Nadvi, 2014). Ties between zones and the local economy may be even narrower in the lower value-added segments of industries such as textiles and clothing, where profit margins are small. For instance, linkages between MNE affiliates in zones and local firms exist but they are confined to the sourcing of low-skilled intermediate inputs (with only a few contractual arrangements involving R&D or other upstream activities).

Box 5.2. Key Features of zones in Asia

In Viet Nam, SEZs play a key role in the government’s FDI attraction strategy. There are currently 295 industrial parks, 3 technology parks and 15 economic zones, which concentrate over 50% of total FDI and 80% of manufacturing FDI. A master plan approved in 2015 provides for the creation of a total of 400 industrial parks and 18 economic zones by 2020. SEZs currently contribute to 40% of GDP and 45% of export value, and employ approximately 2.5% of the workforce. SEZs are under the responsibility of provinces, with the central government only having a coordinating role. All 58 provinces have at least one zone.

In Lao PDR, SEZs have been developed since the early 2000s but remain a relatively new concept. Ten zones have been created, although only two seem to be fully operational. Due to its location on the economic corridor that links Viet Nam, Lao PDR and Thailand, Savan-Seno, the first SEZ established in 2002, attracts investors from a broad range of economic sectors, thereby contributing to the diversification of the economy, currently driven by natural resource extraction. The government is preparing a new SEZ law to ensure that zones have their own regulatory framework, reflecting good international practice.

The Philippines hosts well over 300 zones administered by the 18 different investment promotion agencies which have contributed significantly both to FDI inflows and to exports. The Philippines Economic Zone Authority (PEZA) alone owns three eco-zones and administers the incentives for over 300 privately-managed zones. These include 21 agro-industrial economic zones, 216 IT parks and centres, 64 manufacturing economic zones, 19 tourism economic zones, and two medical tourism zones (as of May 2015). PEZA has a good reputation among investors for its one-stop, non-stop service.

In Cambodia, the legal framework for SEZs was established in 2005, and there are currently 34 approved SEZs, of which 14 were operational as of September 2015. Most are located along the borders with Thailand and Viet Nam and at Sihanoukville and Phnom Penh. As in the Philippines, these SEZs are often privately owned. These zones have helped to start diversifying the industrial base away from garments towards electronics and electrical products, as well as household furnishings and car parts. The zones are nevertheless relatively small and account for a low share of total investment and employment: 68 000 as of 2014 or less than 1% of total employment and 3.7% of total secondary industry employment.

Myanmar opted early on in its reform process to develop SEZs to attract foreign investment. The first SEZ in Myanmar, the Thilawa Special Economic Zone began operation in late 2015. The majority of the roughly 60 businesses to set up at Thilawa have been Japanese, although investors from China, the United States, Thailand and other countries are also present. Sectors include manufacturing of garments and toys, steel products, radiators, aluminium cans, packaging and waste management. As in other AMS, the SEZs in Myanmar could be used as effective pilot schemes for testing new approaches to boost the investment climate, such as in the area of building capacity for monitoring the environmental, social and economic impact of investments in the zones, streamlining registration and licensing procedures, effectively managing incentives, and promoting linkages.

Source: OECD Investment Policy Reviews of Cambodia (2018), Indonesia (2010), Lao PDR (2017), Malaysia (2013), Myanmar (2014), the Philippines (2016), and Viet Nam (2018)

Further efforts to improve data quality and availability would help Egypt better monitor zone outcomes. In particular, the dearth of robust, more granular, statistics makes it difficult to disentangle the contribution of each regime. For instance, according to the list of firms entitled to QIZ duty-free treatment, published by the QIZ Unit, more than a hundred have an address in GAFI’s FZs10 but GAFI reports that 56 companies located in the FZs are entitled to the QIZ treatment, of which 20 companies are in private FZs and 36 are in public FZs. Finally, anecdotal evidence suggests that some private FZs are located within the boundaries of industrial zones. Potential statistical double counting creates opaqueness with regard to the activities of zones and limits the possibility to assess their benefits and costs on the national economy.

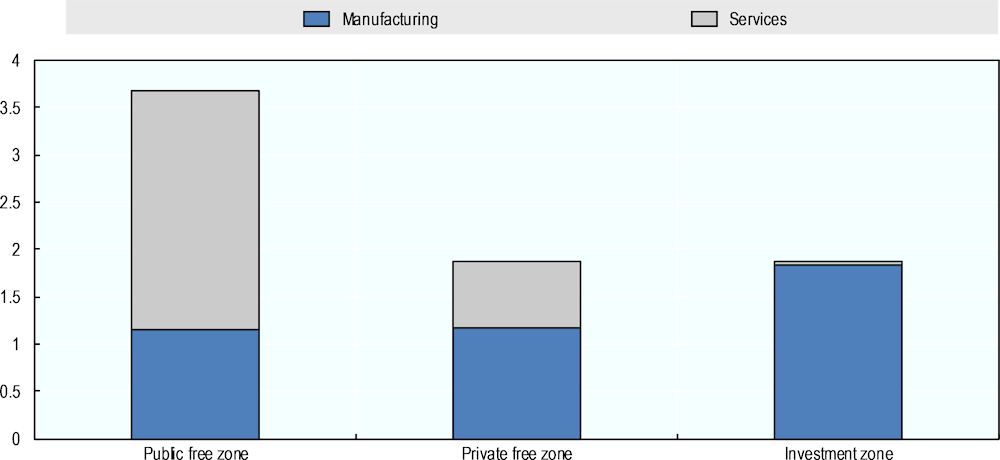

Monitor zones’ investment trends to formulate more targeted policies

Examining zones’ investment features and performance helps to assess whether objectives are on track and if readjustments in zone policies are desirable. First, it is useful to measure the contribution of all the zones to nationwide FDI. Evidence at hand indicates that around 10.5% of Egypt’s national FDI stock is concentrated in public and private FZs and investment zones. Most of this stock is located in public FZs, which have accumulated 5 billion in FDI stock since their introduction in the 1970s (Figure 5.1). Foreign participation makes up 18% of the total issued capital of businesses operating in FZs.11 Private FZs and investment zones, both introduced later, are each home to a stock of FDI of USD 1.9 billion. Foreign investors’ stake in the capital of companies operating in Egypt’s FZs has nevertheless diminished over time, partly driven by fiercer global competition for investment and the multiplication of zones worldwide (Mori, 2017; UNCTAD, 2019).

Figure 5.1. Foreign direct investment in Egyptian zones: manufacturing vs. services

Note: The figures compiled by GAFI use the IMF’ Balance of Payments Manual. They are based on actual paid in capital using the company financial statements of unlisted companies, taking into considerations the inter-company debts, equity, and reinvested earnings. Meanwhile, market valuation was used for listed companies. The stocks are compiled based on 2013 End-year exchange rate (USD 1.0 = EGP 6.9).

Source: OECD based on GAFI statistics.

Statistics on investment trends and performance in other zones types are limited. The introduction of QIZs in 2004 coincided with a period of increased FDI flows to Egypt, including in manufacturing, which ended in 2008 with the global financial crisis. Evidence also indicates that QIZs in Egypt performed less well than those in Jordan in attracting FDI (Nugent, 2010; Azmeh, 2014). With the introduction of the new SEZ law in 2015, the government expects to revive cross-border investments in a wide range of sectors. The SCZone multiplied investment deals in steel, petrochemicals and logistics while the GTZone should attract USD 18 billion in investments over 30 years, mostly in the mining sector, according to government estimates.

FDI composition by sector reflects the strategic objectives set by the central government for each zone type. Evidence suggests that there is ample room for policymakers to steer special regime outcomes in the most desired direction in term of FDI flows. In public FZs, the FDI stock is concentrated in services, mostly in shipping, logistics activities (such as storage and warehousing) and media production (Figure 5.1). This is not surprising as in general FTZs are characterised by intense import-export activities with little or no product transformation. The design of private FZs fits with their objective of attracting export-oriented industrial projects. Along with private FZs, investment zones and QIZs also attract foreign investment in manufacturing sectors such as textiles, food products, chemicals and electronics. Investment zones were created to develop both manufacturing and services clusters, such as in education, but available statistics indicate that these zones have been less successful in attracting foreign investors in services projects (Figure 5.1).

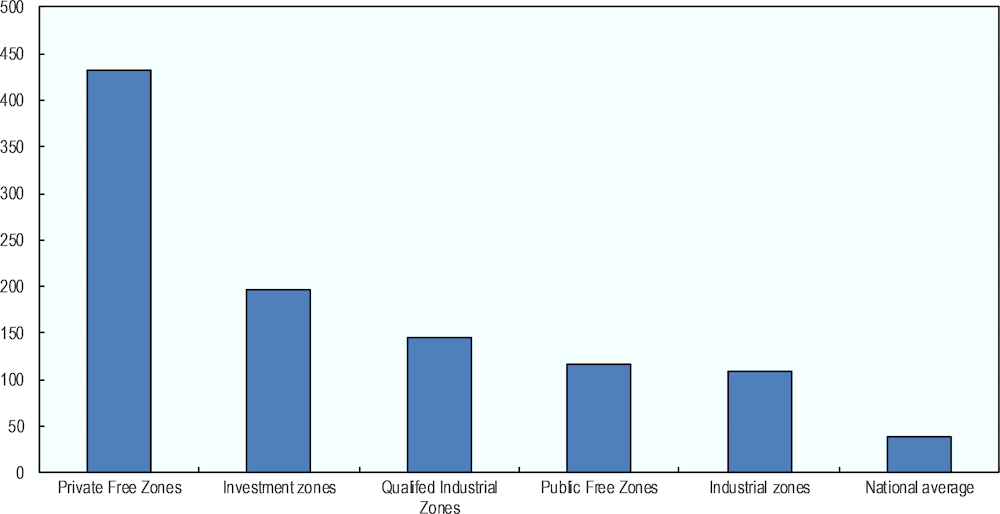

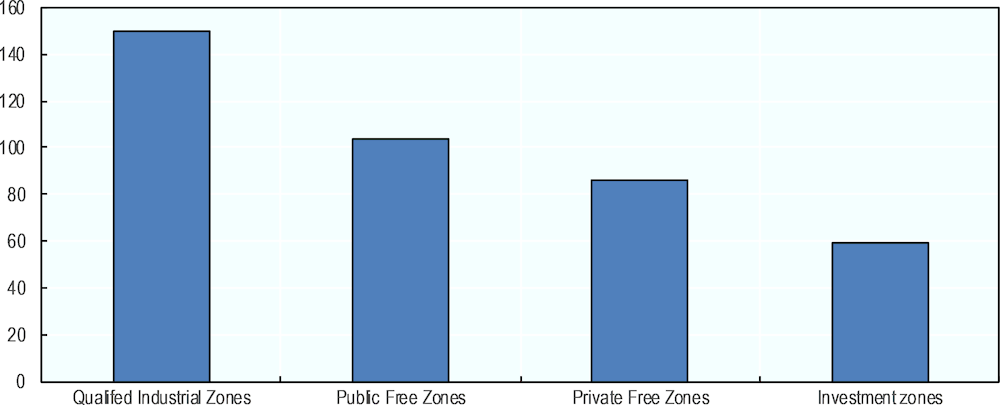

The size of investment projects, both in terms of capital and labour, vary substantially depending on the specificities and regulations of the zone type. The average project in a private FZ employs more than 400 workers, twice that of an investment zone (Figure 5.2). Often, one firm (private FZ) or a small cluster of fewer than 20 firms (investment zones) represents the entire zone.12 Public FZs, QIZs, and industrial zones attract medium-sized firms of 100-150 employees. Available statistics suggest that there is little presence of smaller establishments such as start-ups in Egyptian zones. For instance, in QIZs, only 20% of establishments had fewer than 50 employees in 2016 (QIZ Unit Bulletin). While firm-level data for the SEZ regime areas is limited, it is plausible to assume that this zone type should display greater variety in firm size due to the regime’s development objectives and wide geographical coverage.

Figure 5.2. Firm size in zones in Egypt

Note: The national average and the average firm size for industrial zones are calculated using firm-level sample weightings. Only firms that are formally registered are included.

Source: OECD based on GAFI Statistics, QIZ Unit Bulletin, and the World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt.

Beyond capital and labour size, governments expect the features of firms in zones to be different from those not benefitting from differentiated treatment. International evidence suggests that firms in zones are export-oriented, more integrated into regional and global value chains and more productive (Moran, 2011). These firm-level features are intrinsically linked to the raison d’être of zones and should reflect their entry requirements. In Egypt, firm-level data for each zone type are limited, making it difficult to compare the features and performance of firms in zones with those located outside.

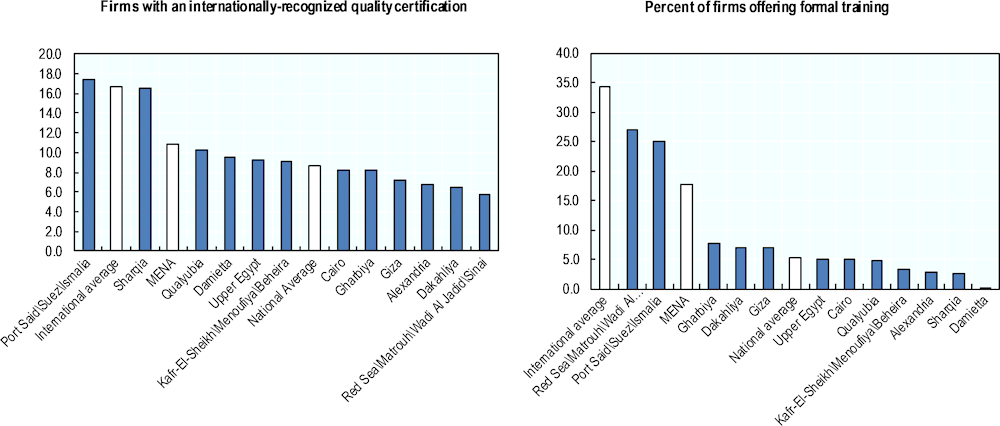

The 2016 World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt provided insights on establishments located in an industrial zone.13 These establishments tend to outperform those not located in zones in a number of criteria. They tend to be more productive and are more likely to export, hold an internationally-recognised certificate and offer more training to their staff (Table 5.5). Relatedly, their sales are more than double that of firms located outside industrial zones. Despite stronger performance, the percentage of foreign-owned businesses or of skilled workers is similar within and outside of industrial zones. It may be that foreign investors favour other zone types because of their wider incentives and higher level of protection. With respect to skills, the difference could be driven by low-skilled, labour-intensive activities in industrial zones, potentially explaining at the same time the higher share of female employees (El-Haddad, 2016).

Table 5.5. Firm characteristics in industrial zones versus the rest of the economy

|

Is the firm located in an industrial zone |

Yes |

No |

|---|---|---|

|

Firm size (average number of employees) |

101 |

39 |

|

Firm productivity (median) |

141 666 |

71 666 |

|

% of foreign-owned firms |

4.3% |

4.9% |

|

% of exporting firms |

30% |

15% |

|

% sales that are exported (average) |

48.3% |

22.7% |

|

% of foreign inputs (average) |

22.6% |

20.9% |

|

% of women employees (average) |

11% |

7% |

|

% of high-skilled employees (average) |

56% |

64% |

|

% of firms that offer training |

13.1% |

5.9% |

|

% of firms with an international certification |

25% |

7% |

Note: Variables are calculated using sample weightings provided by the World Bank Enterprise Survey.

Source: OECD based on the World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt (2016).

Several factors explain MNEs decisions to locate in Egypt’s zones

A combination of business-climate, region- and zone-specific factors drive foreign MNEs to invest in Egypt’s zones. Country-wide determinants hold for the attractiveness of the various zone types. They include Egypt’s unique position as the gateway to the EU, Africa and the Greater Arab Free Trade Area or GAFTA with both preferential trade and investment agreements with these regions, a large domestic market, and advantages in labour costs.14 The top factors do not necessarily include the granting of tax incentives, which international evidence suggests are less important for attracting FDI but can heavily affect the government’s budget.

By providing investors with a range of incentives, zones encourage them to locate in specific geographical regions, either because the areas are close to infrastructure hubs (ports, airports and railways) or markets, or because they are poorer areas that necessitate private investment. For instance, the 2017 Investment Law introduced a new incentives taxonomy to promote investment in certain geographical locations, including greater incentives for firms that locate in SEZs.

Because of the government’s location-based investment incentives (and with the exception of Cairo), governorates with zones have become home to relatively higher shares of foreign investment compared to the rest of the country. In the governorates forming the SCZone, the average proportion of foreign investment in a firm reached 19% of the total capital in 2013, well above the 5.5% national average. With the exception of Cairo, FDI is also more concentrated in governorates with larger industrial zone lands (Suez, Alexandria, Giza, and Port Said). For instance, the governorate of Giza, a top FDI recipient, hosts five out of the 13 investment zones, one public FZ and 9% of the governorate land is allocated to industrial zones (Table 5.6). Governorates with FZs also report higher levels of investment, with two-thirds of the total investment in FZs concentrated in the governorates of Alexandria and Cairo.

Table 5.6. FDI is more concentrated in governorates with larger industrial zones

|

Top 10 FDI recipients |

FDI (% total) |

Greenfield FDI (% total) |

Industrial Zone (% governorate size) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cairo |

32.42 |

63.80 |

0.90% |

|

Suez |

6.08 |

11.72 |

4.97% |

|

Alexandria |

7.16 |

5.41 |

3.99% |

|

Giza |

27.46 |

3.73 |

8.74% |

|

Port Said |

2.25 |

3.53 |

10.08% |

|

Damietta |

2.37 |

1.72 |

0.33% |

|

Behera |

0.92 |

1.49 |

0.04% |

|

Aswan |

0.81 |

1.46 |

0.00% |

|

South Sinai |

1.45 |

1.21 |

0.00% |

|

Fayoum |

0.66 |

1.08 |

0.73% |

Source: OECD based on GAFI statistics and Dealogic Analytics.

Governorates with FZs are particularly attractive to foreign, non-Arab, investors because they provide, among other services, better access to information (Hanafy, 2015). When prospecting potential investment locations, foreign firms often face information asymmetries and business uncertainties that result in high information costs (Mariotti et al. 2010). In Egypt, as in other developing countries, publicly available information about the business environment at the sub-national level is often scarce. Foreign investors end up relying on signalling effects, i.e. they mimic the location decisions of already established investors, or may choose to set up in a zone because of the quality of the information provided. Governorate, city and zone authorities could co-ordinate their investment promotion and economic development actions to further guide investors in their location decision process. Private sector development of the inland regime areas bordering FZs may encourage stronger business connections between the two regimes and contribute to the wider development of the governorate.

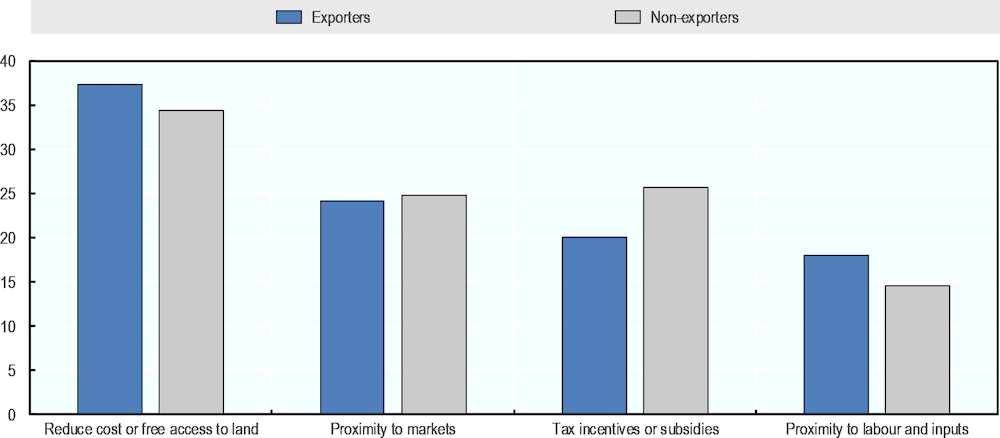

Figure 5.3. The key determinants to open a business in an industrial zone

Note: Variables are calculated using sample weightings provided by the World Bank Enterprise Survey.

Source: OECD based on the World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt (2016).

Investors in Egypt, as elsewhere, often opt for zones to benefit from a friendlier business environment than in the rest of the country. The first zone-specific determinant that pushes investors to locate in zones is land availability and access, which continue to be a severe barrier to doing business in Egypt (see Chapter 3). Evidence reveals that “access to land at a reduced or no cost” is the most important reason behind manufacturing firms’ choice to locate in an industrial zone (Figure 5.3). It is plausible to assume that the land determinant holds also for investors that decided to locate in other zone types of Egypt. Proximity to markets, particularly for exporters, followed by tax incentives (or subsidies) are the second and third most important decision factors for firms locating in an industrial zone. This evidence confirms that, while important, specific tax incentives may not be as crucial a factor to investors as Egypt’s geographical position and large market size. Agglomeration effects (proximity to inputs and labour) are driving less investors’ choice to locate in an industrial zone, suggesting that sourcing from local suppliers close to zones areas is limited.

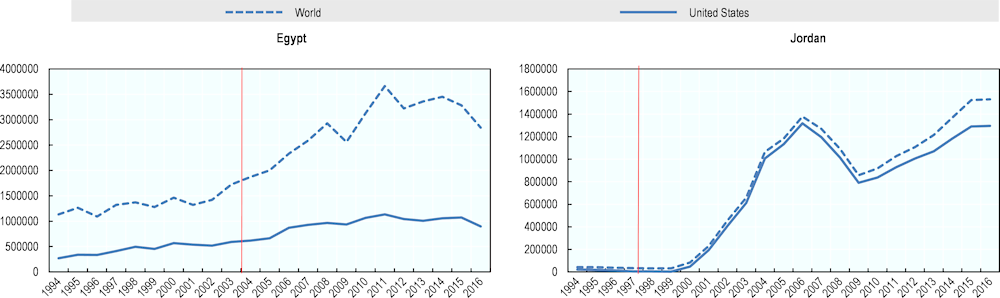

Figure 5.4. Textile and clothing exports after signing the QIZ protocol (in USD)

Source: OECD based on the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS).

Other hurdles investors face in doing business in Egypt (or in certain regions of Egypt) are not necessarily addressed by zones’ friendlier environment. These may consist of regulatory challenges such as poor intellectual property rights or of scarcity of resources such as the lack of adequate skills. QIZs are an edifying example of how zones are a second-best policy tool to attract FDI, the first-best being to reform the wider business climate. Jordan, which signed the same Protocol in 1997, attracted more foreign multinationals than Egypt in QIZs, despite higher labour and production costs (Figure 5.4). Comparative evidence indicates that the flexible Jordanian regulatory framework, particularly concerning the hiring of foreign workers, was a decisive factor for MNEs to prefer Jordan over Egypt (Box 5.3).

Box 5.3. The role of Egyptian QIZs in boosting exports: A comparative analysis with Jordan

The QIZ protocol signed by both Egypt (in 2004) and Jordan (in 1997) with the United States provides a natural laboratory for comparative policy analysis of the performance of QIZs in both countries. It sheds light more broadly on the role of special investment regimes in upgrading the manufacturing performance of the textile and clothing industry in Egypt.

The Egyptian textile and clothing sector accounts for 3% of GDP and around 30% of the manufacturing workforce. Exports of textiles and clothing represent 15-25% of non-oil exports depending on the year. QIZ exports made up 33% of exports of textiles and clothing. There are around 7 000 firms in the textile and clothing sector, 196 of which are in free zones. It is likely that these 196 firms are also entitled to QIZ provisions, benefiting from free zones incentives and US duty-free access.

No statistics are available on the amount of foreign investment in Egyptian QIZs but evidence from Azmeh (2014) suggests that MNEs played only a limited role in QIZs expansion. The positive impact of the protocol on exports was driven by an expansion of large firms exporting to the US prior to the introduction of QIZs. Larger firms expanded after the protocol, as they could save on their variable costs when purchasing Israeli products in bulk. Limited shifts in the distribution of textile exports towards SMEs occurred after the establishment of the QIZ protocol. Linkages exist between SMEs and large firms operating in QIZs but remain weak, with little evidence of sub-contracting agreements between large firms and SMEs to improve their capabilities.

In contrast, the QIZ protocol contributed to the emergence of a textile sector in Jordan, mostly through large foreign capital and labour from Asia. Foreign firms indicated that the main reason of choosing Jordan instead of Egypt as a QIZ-investment location (as most firms view them as substitutable locations) was the ability for them to build the production and labour regimes required to meet the needs of their US buyers. The Jordanian framework enabled foreign companies to rapidly bring in qualified, competitive, foreign labour from South Asia, thereby maintaining a high locational mobility.

Regulatory flexibility in zones’ framework may nevertheless come with a cost. The fast “entry-exit” GVC governance strategy of MNEs in Jordan’s QIZ led to low levels of embeddedness in the local economy. In such a context, it is less likely that there will be spillovers to the local economy as this requires MNEs making organisational and financial investments, which are not part of their governance strategy. Recent reforms in Egypt eased the restrictions on hiring foreign workers, including in the SEZ regime. Under the inland regime the foreign workers rate could be increased from a maximum 10% to 20% of the total number of workers in a company, if it is not possible to hire national manpower with the required qualifications. The impact of this reform may be limited if QIZs’ attractiveness depends only on duty-free access to the US market and low-cost labour, however.

Source: OECD based on Azmeh (2014) and Nugent and Abdel-Latif (2010)

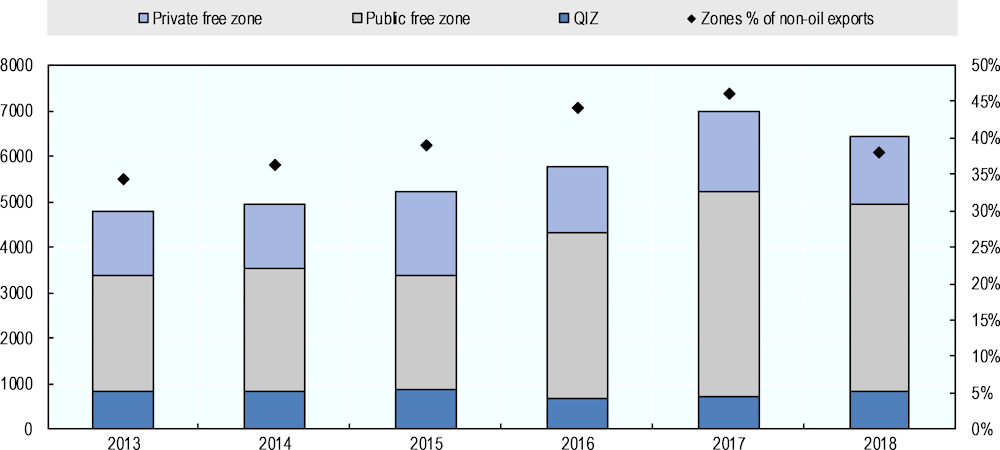

Improve zones’ attractiveness as export hubs and modernise their industrial capabilities

Zones have helped boost Egyptian manufacturing exports and integrate the economy into GVCs, despite the aforementioned competitiveness challenges. They have become increasingly central in the country’s export landscape. A decade ago, a study estimated that 23% of Egypt’s exports originated from export processing zones, similar to Morocco (25%) and several other emerging countries. During the same period, they represented half of China’s or Mexico’s exports (Degain, 2011). Ten years later, export data from public and private FZs and QIZs suggest zones represented 40% of Egypt’s non-oil exports in 2018 (Figure 5.5). Public FZs drove the increase in exports, while private FZs and QIZs witnessed a stagnation in exports, at least in the last few years.

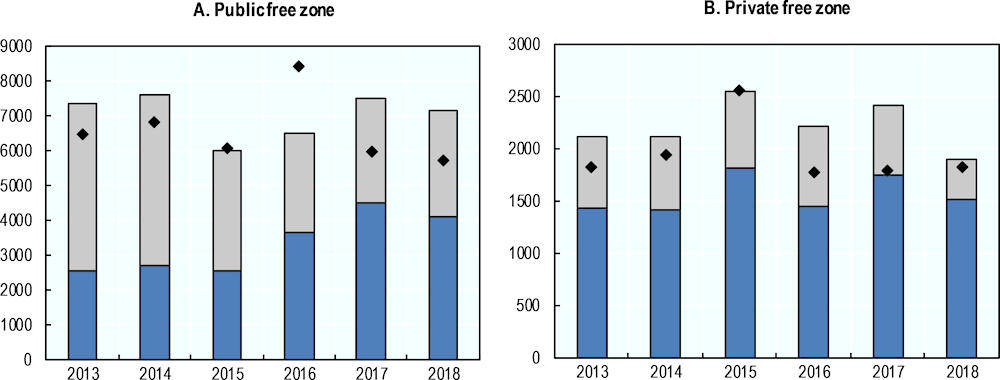

Although zones in Egypt certainly stimulated exports, the extent to which their performance has met the objectives set by the government is an open question. Public and private FZ projects, for instance, are not necessarily creating substantial value-added, as they import more than they export (Figure 5.6). FZ projects’ trade balance was positive in the last two years, but only when sales on the domestic market are categorised as exports. With such trade outcomes, FZs are falling short of reaching their strategic objectives of contributing to national trade deficit reduction. QIZ firms report higher export-to-import ratios. Only 10% of QIZ exports to the US include intermediate inputs, imported from Israel. There is no publicly available data on exports by SCZone projects.

The trade outcome of public FZs is arguably to be expected, given their design. Firms located there mostly offer transport and warehousing platform services for import-export transit and, therefore, do not necessarily create significant value-added. The causes behind private FZs’ trade deficit during this period are less straightforward since they mostly consist of large industrial establishments with, in principle, strong export potential. It is likely that the regional and national contexts in the aftermath of the 2011 events, combined with lukewarm global demand, have affected FZs exports during the last years.

Figure 5.5. Egyptian zones’ contribution to non-oil exports

Note: A possibility of double counting exists due to presence of QIZ-listed firms in public Free zones. There is no publicly available data on exports by projects in the SCZone, GTZone and investment zones.

Source: OECD based on GAFI statistics, QIZ Unit Bulletin and the Central Bank of Egypt.

Figure 5.6. Free zones’ exports, imports and sales on the domestic market

Source: OECD based on GAFI statistics.

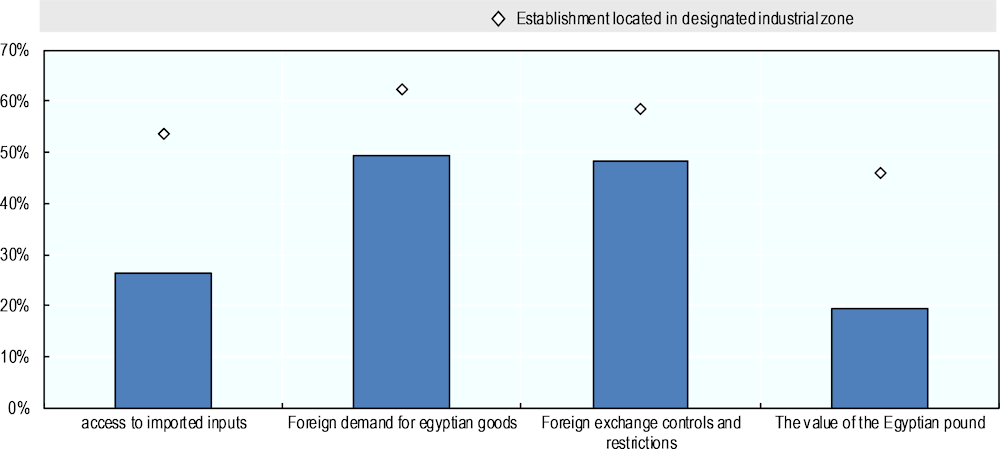

Improving zones’ attractiveness as export hubs and modernising their industrial capabilities should be among the top priorities of the Egyptian government. The main barriers to export in Egypt in 2016 were the value of the Egyptian pound and foreign exchange controls and restrictions, which affected all firms regardless of their investment regime (Figure 5.7). Despite the provision by the Egyptian authorities of generous fiscal incentives to zone investors, this could not compensate for an overvalued exchange rate, reducing the competitiveness of labour-intensive products and deterring FDI (Moran, 2011). The decision by the Central Bank of Egypt to float the exchange rate in 2016 and the new provisions of the 2017 Investment Law to facilitate the repatriation of benefits are important steps in the right direction to lower these two important barriers.

Figure 5.7. Export constraints in industrial zones versus rest of the economy

Note: Variables are calculated using sample weightings provided by the World Bank Enterprise Survey.

Source: OECD based on the World Bank Enterprise Survey of Egypt (2016).

Other constraints, such as the lack of access to imported inputs, also negatively affect Egyptian exporters, especially businesses located in industrial zones, which do not receive as much duty-free customs or facilitated import procedures as firms in special regimes. It is plausible to assume that firms under the FZ and SEZ regimes face lower constraints to accessing imports. Industrial zones’ competitiveness could be further enhanced if they had easier access to foreign inputs as it would allow them to lower production costs or fabricate better quality goods (or both).

Besides wider investment climate considerations, export capabilities of businesses in zones are also intrinsically linked to the sector in which they operate. In the textile and clothing sectors, firms in FZs and, to a greater extent, in QIZs are essential to the sector’s overall production. Firms entitled to QIZ duty-free treatment made up 4.8% of national non-oil exports and half of Egypt’s non-oil exports to the US. They also accounted for around a third of exports of textile and clothing products, although QIZ export performance has slightly deteriorated over the last decade. The government should also promote and facilitate investment in higher-value added segments of the flourishing chemicals and food sectors by aligning sectoral strategies with zones’ priorities and objectives.

Entities involved in setting the strategic objectives of zones should co-ordinate their efforts to promote private investment in the higher value-added segments of sectors’ supply chains. The limited private domestic and foreign investment in the textile and clothing upstream activities, which are capital-intensive as they require modern technologies, hinders potential productivity gains in the whole sector (Nugent and Abdel-Latif, 2010). Egyptian state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dominate the upstream stages of the textile supply chain but produce at a higher cost than competitors abroad due to, inter alia, ageing technology. As a result, firms in downstream activities in zones mostly source their inputs from more competitive markets such as China.

Investment that upgrades industrial capabilities within zones is necessary to restore the deteriorating competitiveness of the upstream textile and clothing sector. The need for such investment is even more pressing given the recent increase in electricity and gas prices, which will put pressure on production costs throughout the supply chain. SMEs located in zones will likely be more adversely affected by such cost increases than larger firms and SOEs. More private investment in upstream activities, possibly resulting in technological upgrading, would also foster longer-term business linkages as inputs sourced by downstream establishments would become less costly and of better quality than those fabricated currently. The rise in gas prices also affects the competitiveness of some of the segments of the booming chemicals sector.

Government policies should aim to diversify production away from ready-made garments, which predominates manufacturing production in FZs and QIZs, particularly since the preferential treatment of Egyptian exports through the QIZ will erode over time due to the widening network effect of US FTAs. To preserve the competitive edge of the QIZ, it is crucial to widen the scope of manufacturing products exported by zones. For instance, food and other non-textile exporters such as chemicals producers have a limited interest in using QIZs as a vehicle to enhance their US exports. Despite an increase, exports of food products by firms in QIZs still only account for around 1% of total QIZ exports. Some firms are not able to export to the US because of challenges in marketing their products, expensive Israeli inputs, lack of skilled labour, and financial constraints (Ghoneim and Awad, 2010).

Mitigate zones’ adverse impacts on the domestic market

The large amount of production sold by zones, mainly public FZs, on the domestic market is another facet that reveals zones’ challenge in meeting their development objectives.15 There are several reasons behind these large domestic sales. On the one hand, the access to a large domestic market pushes firms to sell imported goods (instead of using imported inputs in the production process) or to discharge an excess of production that they cannot export. On the other hand, the lack of competitiveness and adequate knowledge of foreign markets reduces the capacity of businesses in FZs to export (Mori, 2017).

Regulatory restrictions and cumbersome import procedures in the inland regime amplify the domestic demand for imported goods transiting via FZs and the SCZone. In both zones, sales by firms in zones to the domestic market are treated as imports and are therefore subject to the general rules applicable to imports from abroad, i.e. they are subject to taxes and customs (Table 5.7). According to consultations with government representatives, public authorities authorise using temporarily zones with duty-free access as import entry doors in periods where the country faces severe shortages in some products.

Table 5.7. Zones’ import and export relationship with the inland regime

|

Zone |

Access to the local market |

Sourcing from the local market |

|---|---|---|

|

Free Zone |

- Products are subject to the general rules applicable to importation from abroad. - If the products contain both local and foreign components, the customs tax basis applies only to the foreign components. - A fee of 1% of the total revenues realised is charged on local sales by public Free zones industrial projects (same fee than if exported). - A fee of 2% of the total revenues realised is charged on local sales by private Free zones projects (1% if exported abroad). |