On average across OECD countries, 58% of 25-34 year-old adults who have not completed upper secondary education are employed compared to 78% among those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment and 85% among those with tertiary attainment.

On average across OECD countries, the employment rate of younger women (aged 25-34) without upper secondary attainment is 43%, compared to 69% for their male peers, but the disparities narrow as educational attainment increases: 80% and 87% for tertiary-educated women and men, respectively.

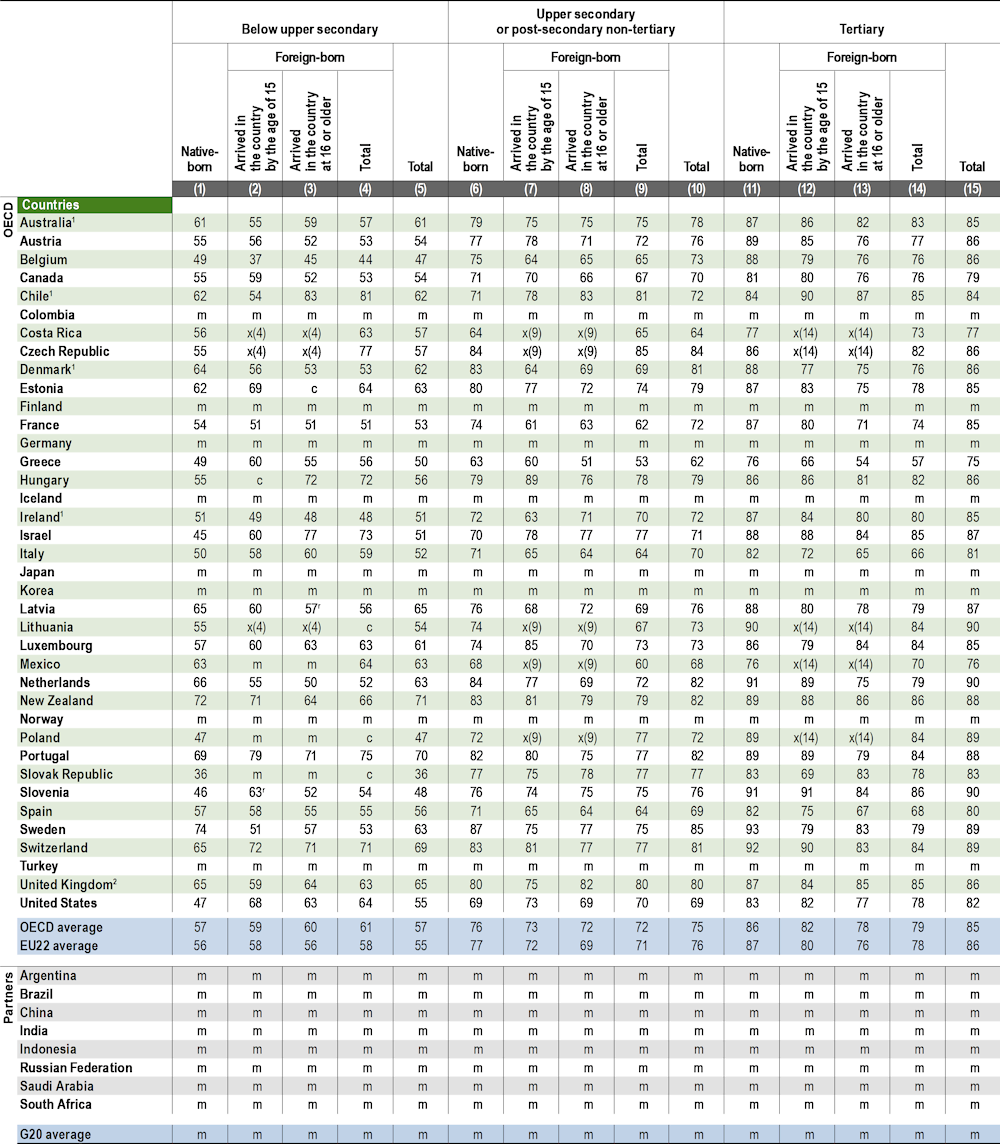

Foreign-born adults with tertiary attainment have lower employment prospects than their native-born peers in most countries with available data. However, labour-market outcomes for foreign-born adults without upper secondary attainment are mixed across OECD countries.

Education at a Glance 2021

Indicator A3. How does educational attainment affect participation in the labour market?

Highlights

Countries are ranked in ascending order of the unemployment rate of 25-34 year-olds with below upper secondary attainment in 2020.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A3.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Context

The economies of OECD countries depend upon a supply of highly skilled workers. Expanded education opportunities have increased the pool of skilled people across countries, and those with higher qualifications are more likely to find employment. In contrast, while employment opportunities still exist for those with lower qualifications, their labour-market prospects are relatively challenging. People with the lowest educational qualifications have lower earnings (see Indicator A4) and are often working in routine jobs that are at greater risk of being automated, therefore increasing their likelihood of being unemployed (Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn, 2016[1]). These disparities in labour-market outcomes can exacerbate inequalities in society. The health crisis we are experiencing linked to the spread of COVID‑19 will undoubtedly have an impact on unemployment, and those with lower educational attainment might be the most vulnerable. The impact will have to be monitored in the coming years (OECD, 2021[2]).

Comparing labour-market indicators across countries can help governments to better understand global trends and anticipate how economies may evolve in the coming years. In turn, these insights can inform the design of education policies, which aim to ensure that the students of today can be well prepared for the labour market of tomorrow.

With continued migration flows across OECD countries, the labour-market situation of foreign-born adults stimulates the public debate. According to the International Migration Outlook 2020 (OECD, 2020[3]), 14% of the total population in OECD countries are foreign-born. The important rise in humanitarian migration has largely contributed to the growing preoccupation with reviewing migration policies. However, humanitarian migration makes up only a part of total population flows. A large share of migrants moves for work reasons, and there is evidence of positive social and economic returns to migration. Overall, foreign-born adults largely contribute to increasing the workforce, and they generally contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in benefits (OECD, 2014[4]).

Other findings

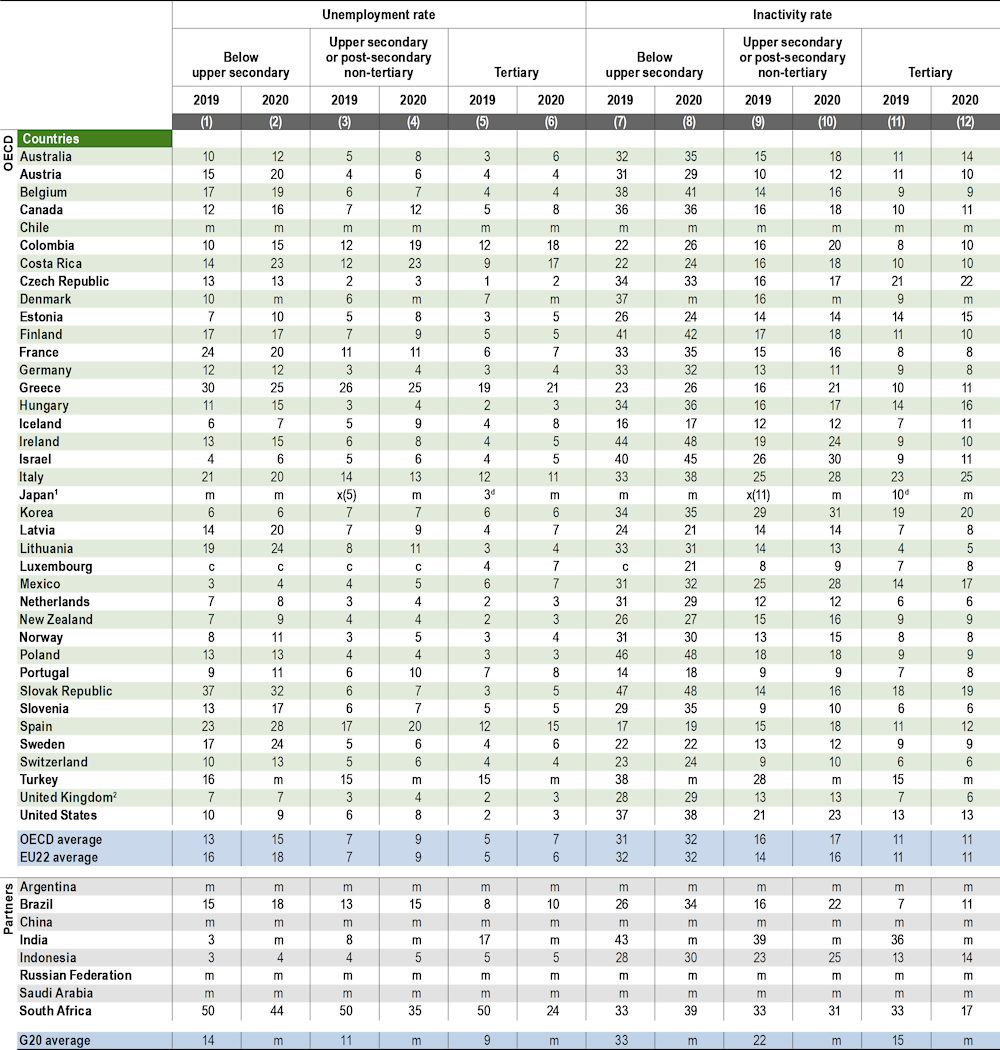

On average across OECD countries, in 2020, the unemployment rate is almost twice as high for those who have not completed upper secondary education as for those with higher qualifications: 15% of younger adults (aged 25‑34) without upper secondary attainment are unemployed, compared to around 8% for those with a higher level of education (i.e. upper secondary, post-secondary non-tertiary attainment or tertiary attainment).

In all OECD countries, unemployment rates decrease with time since graduation. In 2018, on average across OECD countries, one out of five (21%) young adults with upper secondary attainment were unemployed during the first two years after graduation. The unemployment rate decreases to 14% two to three years after graduation, and to 12% four to five years after graduation.

Analysis

Educational attainment and labour-market outcomes

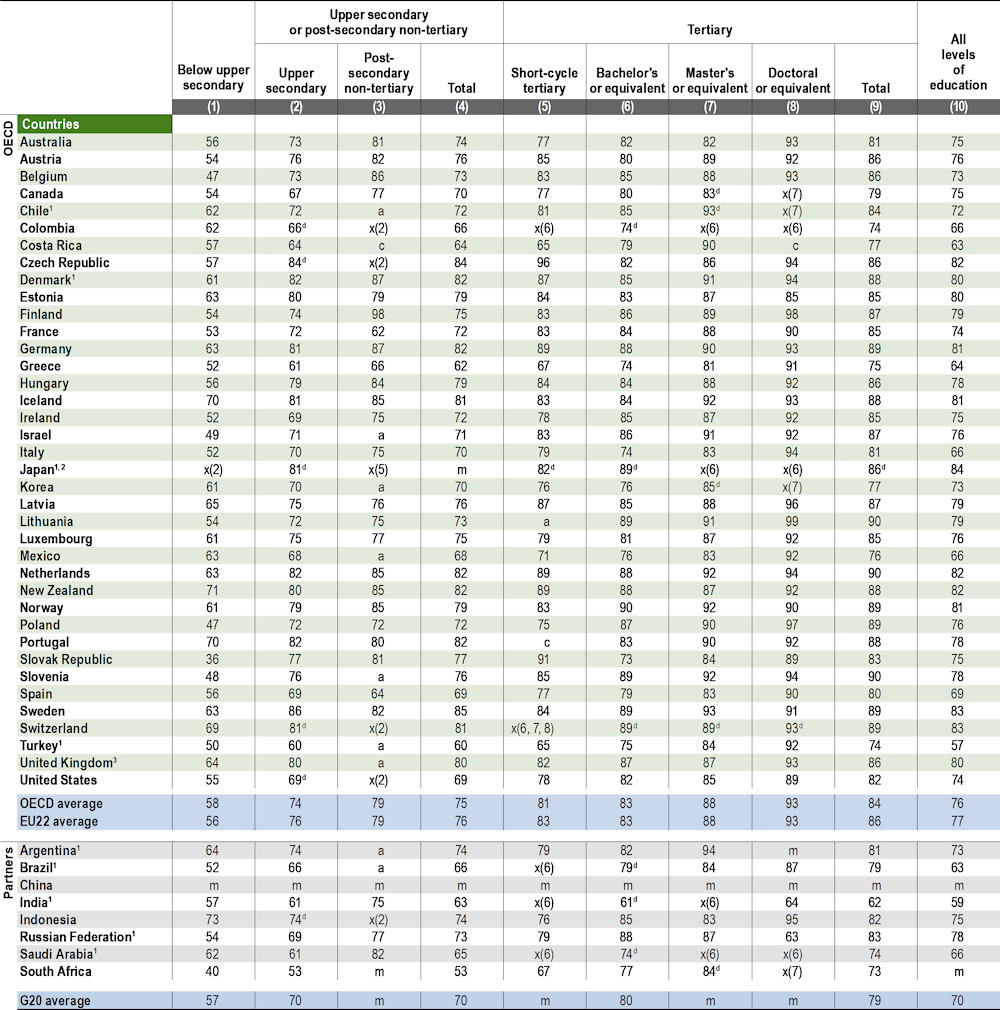

Upper secondary attainment is often considered the minimum requirement for successful labour-market integration. Adults without this level of education are less employed, regardless of their age. On average across OECD countries, the employment rate is 58% for adults (25-64 year-olds) without upper secondary education and 75% for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest attainment, i.e. 17 percentage points more. On average across OECD countries, the employment rate for tertiary-educated adults increases by a further 10 percentage points (84%) compared to those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest attainment (Table A3.1).

The employment premium of upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment compared to lower educational attainment levels is the highest and exceeds 20 percentage points in Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Israel, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and Sweden. In contrast, the employment premium is less than 5 percentage points in Colombia, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia (Table A3.1).

Inversely, unemployment rates are decreasing with higher educational attainment levels. On average across OECD countries, the unemployment rate is 10.6% for adults without upper secondary attainment, 6.6% for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment, and 4.7% for those with tertiary attainment. In Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Norway, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Sweden, the unemployment rates of adults without upper secondary attainment are more than twice as high than that of adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment (OECD, 2021[5]).

Educational attainment, unemployment and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused an unprecedented economic crisis that began in most countries in 2020. In early 2020, the quarantine or sickness of workers and lockdown measures interrupted international supply chains following the spread of the virus, leading to a severe “supply shock” which affected many countries. At the same time, the economy was affected by a “demand shock” as people in many countries were forced to lockdown and the disposable income for many workers shrank due to fewer hours worked or from having been dismissed. The massive economic shock not only affected countries where governments responded with restrictive measures (e.g. lockdown), but also countries relying more on social conformity and/or social capital rather than on enforced confinement (OECD, 2020[6]).

In the most affected countries, including those with lower levels of employment protection, unemployment rates skyrocketed within a few weeks. For instance, in the United States, the unemployment rate jumped from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.7% in April 2020, in Canada from 5.7% to 13.1% and in Colombia from 12.3% to 21.0% over the same period. In many countries, unemployment rates reversed after the peak, but remained at a higher level than they were at the beginning of the year (OECD, 2020[6]).

In many OECD countries, unemployment rates have increased between 2019 and 2020 for each level of education. Unlike the 2008 crisis, there is no clear pattern of which education levels are the most affected by the crisis in 2020 compared to 2019. In general, those with secondary or tertiary attainment are affected in often-equal proportions by the increase in unemployment rates between 2019 and 2020. However, in a few countries, such as Austria, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden, the unemployment rate for 25-34 year-old adults who have not attained upper secondary education has increased by at least five percentage points between 2019 and 2020, while it has remained stable over this period for other levels of education (the increase is no more than three percentage points). On average across OECD countries, the unemployment rate among 25‑34 year-olds with below upper secondary attainment is 15.1% in 2020, showing an increase of about 2 percentage points in one year’s time. The increase is the largest in Austria, Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden, where the unemployment rate among young adults with below upper secondary attainment has grown by at least 5 percentage points over this period. France, Greece and the Slovak Republic show the opposite pattern: in these countries, the unemployment rate among 25-34 year-olds with below upper secondary attainment has fallen by at least 4 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. However, these figures should be interpreted with caution, as these three countries have seen the inactivity rate of those who have not attained upper secondary education increase over the same period Figure A3.1. and Table A3.3).

On average across OECD countries, the unemployment rates among younger adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment have increased by 2 percentage points between 2019 and 2020, and the unemployment rates have increased by 1 percentage point among those with tertiary attainment. The increase in unemployment rates among younger adults with these levels of educational attainments has exceeded 5 percentage points in Colombia and Costa Rica. (Table A3.3).

Unemployment statistics do not capture all of the labour-market slack due to COVID-19, as some unemployed individuals may be classified as “out of the labour force” because, due to the pandemic, they are unable to actively seek employment or are not available for work. Therefore, the difficulties related to the lockdown and the whole economic context have led to an increase in inactivity rates in some countries. For instance, in Brazil, Israel, Italy, Slovenia and South Africa, inactivity rates of young adults with below upper secondary attainment have increased by at least 5 percentage points between 2019 and 2020. Women have been particularly affected: for instance, in Italy, the inactivity rate among women without upper secondary attainment has risen from 53% in 2019 to 59% in 2020 and that of men from 18% in 2019 to 22% in 2020 (Table A3.3 and OECD (2021[5])).

The availability of job retention schemes in many countries has limited the impact of the economic crisis on unemployment rates in 2020. Job retention schemes, such as the “Kurzarbeit” in Germany, the “Activité partielle” in France or the “Expediente de Regulación Temporal de Empleo” in Spain allowed preserving jobs at companies experiencing a temporary drop in business activity, while providing income support to workers whose hours have been reduced or who are temporarily laid off (OECD, 2020[6]).

1. Year of reference differs from 2020. Refer to Education at a Glance Database for details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the employment rate of 25-34 year-old women with below upper secondary attainment in 2020.

Source: OECD (2021), Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Educational attainment and unemployment, by age and gender

In many OECD and partner countries, unemployment rates are especially high among younger adults with lower educational attainment levels. On average across OECD countries, in 2020, the unemployment rate for younger adults (25-34 year-olds) lacking upper secondary attainment is 15.1%, significantly higher than that for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment (8.9%). The unemployment rate for tertiary-educated younger adults is 6.6% (Table A3.3).

The situation is especially severe for younger adults without upper secondary attainment in the Slovak Republic and South Africa, where more than 30% of younger adults are unemployed. The unemployment rate is also high in Austria, Belgium, Costa Rica, France, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Spain and Sweden, where about one in five or more younger adults are unemployed (Table A3.3).

Having attained upper secondary education or post-secondary non-tertiary education reduces the risk of unemployment in most OECD and partner countries. In Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Sweden, the unemployment rate for younger adults with below upper secondary attainment is three times higher than that of younger adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest attainment. The employment premium is the highest in Sweden, where the unemployment rate of young adults without upper secondary attainment is about four times higher than that of the higher educated adults (23.6% compared to 6.2%) (Table A3.3).

In many OECD and partner countries, younger adults with a tertiary degree are less likely to be unemployed compared to those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest attainment. The positive effect of tertiary attainment on unemployment rates is particularly high in Lithuania and the United States. In these countries, the unemployment rate among younger adults with upper secondary or post‑secondary non-tertiary attainment is at least double that of tertiary-educated younger adults (Table A3.3).

Young women without upper secondary attainment are particularly affected by high unemployment. On average across OECD countries, the unemployment rate among young women without upper secondary attainment is 17.8% compared to 13.6% among young men. In a few countries including Colombia, Costa Rica, Estonia, Greece and Spain, the gender gap in unemployment rates exceeds 10 percentage points, while in Australia, Austria, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, men and women are similarly affected by unemployment, the difference in unemployment rates for men and women is less than 2 percentage points (OECD, 2021[5]).

With higher educational attainment levels, unemployment levels tend to be not only lower, but also similar between men and women. On average across OECD countries, the difference in unemployment rates is 2.6 percentage points among young adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment and 0.6 percentage points among tertiary‑educated young adults. Nevertheless, in Colombia, Greece and Turkey, the gender gaps among tertiary-educated adults exceeds 5 percentage points (OECD, 2021[5]).

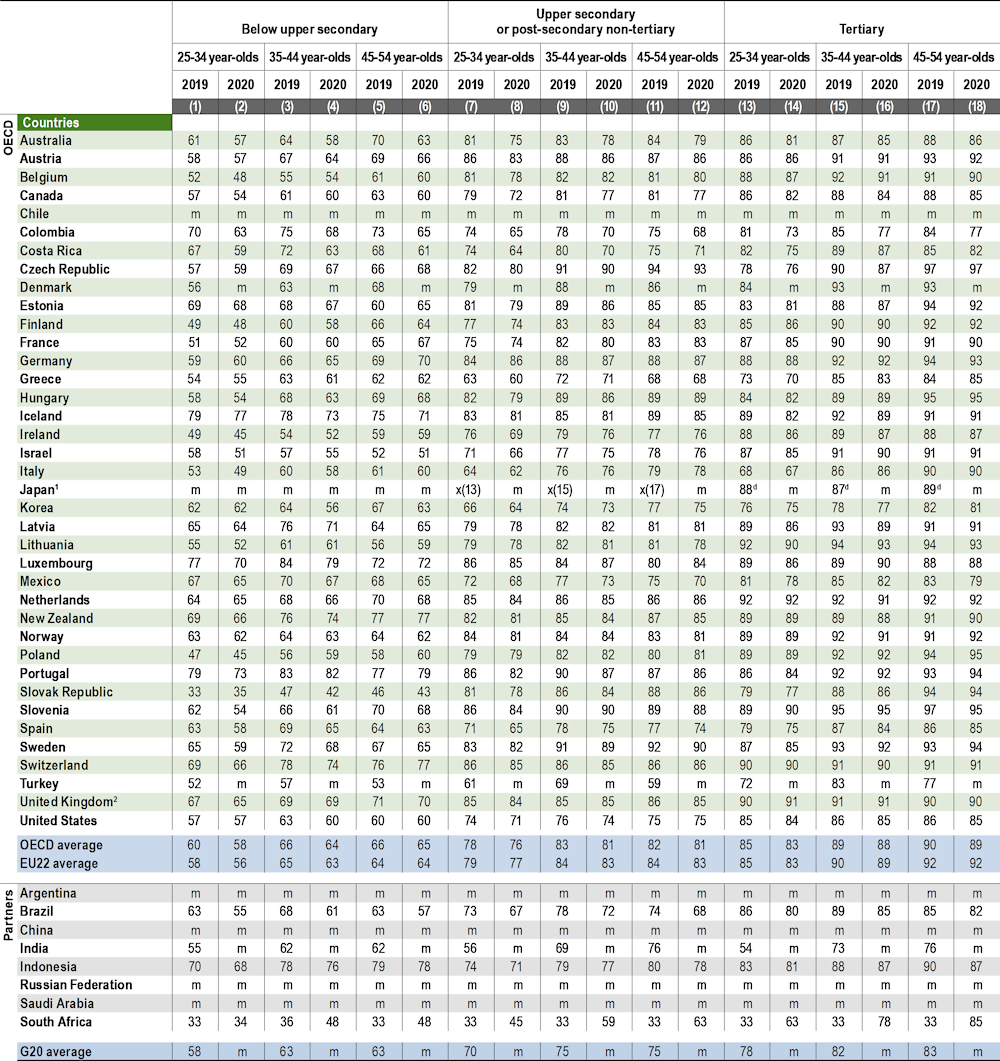

Educational attainment and employment, by age and gender

On average across OECD countries, higher educational attainment is associated with higher employment rates for each age group. Among younger adults (25-34 year-olds), the average employment rate is 58% for those with below upper secondary attainment, 76% for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment as their highest attainment, and 83% for those with a tertiary degree (Table A3.2). Compared to the other age groups, employment rates are lowest for 55‑64 year-olds, regardless of educational attainment level. This is mainly due to retirement, as a large proportion of older adults have already left the labour force (OECD, 2021[5]).

In all OECD and partner countries except Norway, women have lower employment rates than men, regardless of educational attainment, but gender disparities in employment rates narrow as educational attainment increases. On average across OECD countries, the gender difference in employment rates among 25-64 year‑olds without upper secondary attainment is 21 percentage points (68% for men and 47% for women). The difference shrinks to 15 percentage points among adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education as their highest attainment (82% for men and 67% for women), and to 8 percentage points among tertiary-educated younger adults (89% for men and 81% for women) (OECD, 2021[5]).

Employment rates are particularly low for younger women without upper secondary attainment. On average across OECD countries, the employment rate of 25-34 year-old women without upper secondary attainment is 43%, compared to 69% for their male peers, a gender gap of 26 percentage points (OECD, 2021[5]).

In most OECD and partner countries, less than half of younger women (25-34 year-olds) without upper secondary attainment are employed, but in Turkey, only one in four younger women with below upper secondary attainment are employed, compared to more than three in four younger men are. In contrast, in about half of OECD and partner countries, the employment rates of younger men without upper secondary attainment exceed 70% and reach almost full employment (around 90%) in Indonesia and Mexico. In Iceland, younger men without upper secondary attainment have relatively high employment rates (79%), with concurrent high employment rates for women (73%) (Figure A3.2.).

Disparities by gender in employment rates narrow as educational attainment increases and are the lowest among tertiary-educated adults. On average across OECD countries, the gender difference in employment rates among 25-34 year-olds with tertiary attainment is 7 percentage points among tertiary-educated men and women (87% for men and 80% for women). The lowest difference in employment rates (no more than 2 percentage points) are found in Belgium, Iceland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Norway and Slovenia. However, in some countries, the gender difference among young adults with tertiary attainment is still very large and exceeds 20 percentage points in the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and Turkey (OECD, 2021[5]).

The high employment rate of women hides a higher likelihood for women to be in part‑time or part-year employment compared to men. On average across OECD countries, women are about twice as likely as men to work part-time or part-year, regardless of educational attainment (OECD, 2021[7]).

Educational attainment and inactivity, by age and gender

The gender difference in employment rates is also reflected in the gender difference in the percentage of inactive people (i.e. individuals not employed and not looking for a job). Women have consistently higher inactivity rates than men across all educational attainment levels, but the rates are especially high among those who have not completed upper secondary education. Among younger adults with below upper secondary attainment, the difference in inactivity rates for men and women is 27 percentage points (20% for men and 48% for women), while the difference for those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment is 17 percentage points (10% for men and 27% for women), and the difference for those with tertiary attainment is 7 percentage points (7% for men and 14% for women) (OECD, 2021[5]).

The gender gap in inactivity rates of younger adults (25-34 year-olds) without upper secondary attainment is the highest in Turkey (62 percentage points), and the gap is 40 percentage points or more in Argentina, Colombia, India, Indonesia and Mexico. Even though the difference in inactivity rates of men and women decreases with higher educational attainment levels, in one-third of OECD and partner countries, the gender gap in inactivity rates of adults with tertiary attainment is still more than 10 percentage points, and it is above 20 percentage points in the Czech Republic (28 percentage points) and the Slovak Republic (23 percentage points). In only a few countries, including Iceland, Norway and Slovenia is the gender gap in inactivity rates of tertiary-educated adults almost closed (less than 2 percentage points) (OECD, 2021[5]).

Labour-market outcomes for foreign-born adults by educational attainment

The labour-market outcomes for foreign-born adults compared to outcomes for native-born adults vary widely across OECD countries. For both native-born and foreign-born adults, the likelihood of being employed increases with higher educational attainment, but it increases more steeply for native-born adults than for foreign-born adults: among adults without upper secondary attainment, 57% of native-born adults and 61% of foreign-born adults are employed, while among adults with tertiary attainment, 86% of native-born adults and 79% of foreign-born adults are employed, an increase in employment rates of 29 percentage points for native-born adults and 18 percentage points for foreign-born adults (Table A3.4).

Among countries with available data, there are both higher and lower levels of employment rates for adults without upper secondary attainment for native-born versus foreign-born adults. For example, in Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Israel and the United States, the employment rates of foreign-born adults without upper secondary attainment are more than 10 percentage points higher than those of their native-born peers. In contrast, in Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, the employment rates of foreign-born adults with below upper secondary attainment are more than 10 percentage points lower than those of their native-born peers (Table A3.4).

Foreign-born adults have more difficulty finding a job than their native-born peers, as they face various problems, such as recognition of credentials obtained abroad and/or language difficulties ( (OECD, 2017[8])). In addition, as shown in the European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, 2017[9]), foreign-born adults also often face discrimination when looking for work, particularly foreign‑born adults from North Africa. Thus, foreign-born workers are likely to have a lower reservation wage (the lowest wage rate at which a worker would be willing to accept a particular type of job), and this implies that they are more likely to accept any job they can get. This may explain the fact that, in many countries, the employment rate for foreign-born adults with low educational attainment is higher than the rate for their native-born peers. Social policy and income support systems in a country may also play a role.

1. Year of reference differs from 2020. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the employment rate of tertiary-educated native-born adults.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A3.4. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

While labour-market outcomes for foreign-born adults without upper secondary attainment are mixed across OECD countries, foreign-born adults with tertiary attainment have lower employment prospects than their native-born peers in most countries with available data. In Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, the gap in the employment rate between tertiary‑educated native-born and foreign-born adults is more than 10 percentage points, systematically in favour of tertiary‑educated native-born adults (Table A3.4).

For foreign-born adults with a tertiary degree, the age at arrival in the country determines employment prospects. In most countries, the employment rates for foreign-born adults who arrived by the age of 15 are higher than rates for those who arrived in the country at a later age. For instance, in Austria, Estonia, France, Greece, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain, early arrival yields an employment advantage of around 10 percentage points (Figure A3.3).

Since foreign-born adults who arrived in the country at an early age have spent some years in the education system of the host country and gained credentials recognised by the host country, their labour-market outcomes are better than of those who arrived at a later age with a foreign qualification. Foreign-born adults often face problems getting their education and experience recognised in their host country. Such challenges also explain why foreign-born adults are often overqualified for their positions (OECD, 2017[8]) Therefore, in recent years, an increasing number of countries have implemented measures to facilitate the recognition of qualifications and validation of skills (OECD, 2017[10]).

1. Year of reference differs from 2020. Refer to Education at a Glance Database for details.

Countries are ranked in ascending order of the unemployment rate of 25-64 year-olds native-born adults with below upper secondary attainment.

Source: OECD (2021), refer to Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

The lower employment rates of foreign-born adults are reflected in higher inactivity and higher unemployment rates among foreign-born adults compared to their native-born peers. On average across OECD countries with available data, the unemployment rate is 12.2% for foreign-born adults without upper secondary attainment, while the respective rate is 10.3% among their native-born peers. Among those with upper secondary or post‑secondary non-tertiary attainment, the unemployment rate among foreign-born adults is 9.5%, more than 3 percentage points higher than that of native-born adults (5.9%). A similar difference is observed for those with tertiary attainment (7.5% compared to 3.9%) (Figure A3.4. ).

In Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden, the unemployment rates of foreign-born adults without upper secondary attainment exceeds that of their native-born peers by at least 5 percentage points. Hence, in a few countries, including Canada, Israel and the United States, unemployment rates of foreign-born adults with below upper secondary attainment are lower than that of those born in the country (Figure A3.4. ).

Unemployment rates of recent upper secondary graduates

The transition from education to work is a major step in people’s lives. Young adults who leave the education system often face different challenges in finding employment. The health crisis we are experiencing linked to the spread of COVID‑19 will undoubtedly have an impact on youth unemployment that will have to be monitored in the coming years. The use of data from the EU-LFS, complemented by data from administrative sources and other surveys for non-EU-LFS countries, allows a more in-depth analysis of these school-to-work transitions for recent graduates (see Indicators A2 and A3 in Education at a Glance 2020 (OECD, 2020[11]).

In all OECD countries with available data on recent upper secondary graduates, unemployment rates decrease significantly during the first years following graduation, but then tend to stabilise. In 2018, on average across OECD countries, 20.6% of young adults who had recently completed upper secondary education and were not studying any further were not able to find a job within two years of graduation. The unemployment rate among young adults with upper secondary attainment who graduated two to three years earlier is 14.3%, 6.3 percentage points lower than among those who graduated less than two years earlier. Among young adults who graduated four to five years earlier, the unemployment rate is 12.0%, which is only 2.3 percentage points lower (Figure A3.5. ).

1. Data reported under the category "Less than two years" refer to one year since completing education.

2. Year of reference 2017 and 2018 combined. Data reported under the category "Less than two years" refer to one year since completing education. The age group refers to 15-34 year-olds.

3. Data source differs from the EU-LFS.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the unemployment rate of graduates with upper secondary education less than two years after graduation.

Source: OECD (2021), Table A3.5, available on line. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

The differences in unemployment rates of recent upper secondary graduates across OECD countries are larger than the overall differences in unemployment rates among the wider population. Among adults who completed upper secondary education less than two years before, the highest unemployment rate is found in Greece (56.7%) and it is above 30% in Italy, Portugal and Spain. At the other end of the spectrum, the unemployment rate of these recent graduates is less than 10% in the Czech Republic, Germany and the Netherlands. The difference between the countries with the lowest and highest rates exceeds 50 percentage points, much larger than the differences observed across countries for adults with upper secondary attainment. The country with the highest unemployment rate for upper secondary educated 25‑64 year-olds is Costa Rica (16.9%) and Greece (17.4%) and the country with the lowest rate is the Czech Republic (2.2%), a difference of less than 20 percentage points (Figure A3.5. and OECD (2021[5])).

In some countries, school-to-work transitions are particularly difficult and labour-market outcomes remain challenging for several years following graduation. In Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, around one out of three or more upper secondary graduates are unemployed the first two years after graduation. In all of these countries, the unemployment rates decreased four to five years after graduation, by about 20 percentage points in Greece, Italy and Portugal and by 10 percentage points in Spain. However, four to five years after graduation, unemployment rates of recent graduates are still higher than in most other OECD countries. In contrast, in other countries, including Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, the unemployment rates of recent graduates are at most 10% the first two years after graduation, which is half of the OECD average, and they reduced only slightly the following years (Figure A3.5).

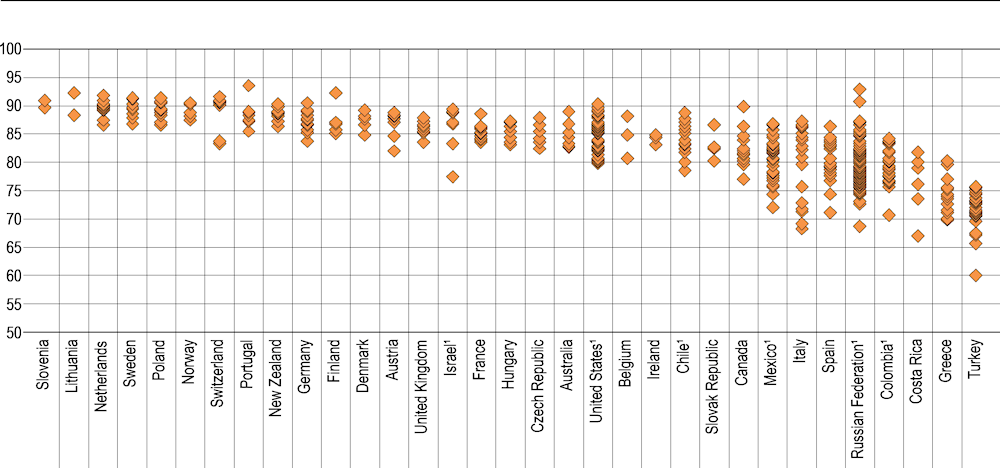

Subnational variation in employment rates

On average, across OECD and partner countries with subnational data on labour-force status, there is more regional variation in employment rates among those with lower levels of educational attainment. For example, in the United States, employment rates for 25-64 year-old adults who have not completed upper secondary education range from 41% in West Virginia to 73% in Wyoming, while the range across regions for adults with tertiary attainment is 10 percentage points, from 80% in Alaska to 90% in the District of Columbia (OECD, 2021[12]).

In a few countries, there is very little regional variation in employment rates among adults with tertiary attainment. In Denmark, France, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom, there is less than a 5 percentage-point difference in employment rates between different regions of the country. Other countries have a broader range of employment rates among regions: the widest disparities of about 20 or more percentage points are observed in Italy and the Russian Federation. For instance, in Italy, the employment rate ranges from 68% in Calabria to 87% in the Aosta Valley (Figure A3.6).

Figure A3.6. Employment rates of tertiary-educated adults, by subnational regions (2020)

Employed 25-64 year-olds among all 25-64 year-olds; in per cent

1. Year of reference differs from 2020: 2019 for Colombia and the United States; 2018 for Mexico; 2017 for Australia, Israel and Chile; 2016 for Canada and the Russian Federation.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the national employment rates for tertiary-educated adults (unweighted average of regions).

Source: OECD INES/CFE Subnational Data Collection. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Despite the concentration of economic and administrative activities in the capital city regions, in most countries, the regions with the capital cities are not those with the highest employment rates. In Austria and Lithuania, the employment rates of adults with below upper secondary attainment are the lowest in the capital city region. For instance, in Austria, the employment rates of adults with below upper secondary attainment are 64% in Vorarlberg and 46% in Vienna, the capital city. Only in 6 countries are the highest rates found in the capital city region. Similarly, in 5 countries, the employment rates of adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary attainment are the lowest in the capital city region and the highest in only 5 countries. In contrast, the employment opportunities in the capital city regions seems to be more advantageous for adults with tertiary attainment. In 9 countries (Colombia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, the United Kingdom and the United States), adults with tertiary attainment have the highest employment rates in the capital city regions. For instance, in Colombia, the employment rate ranges from 71% in Chocó to 84% in the Bogotá Capital District. In a few countries, including Austria, Belgium and Israel, the employment rates in the capital city region are the lowest across regions in the country (Figure A3.6 and OECD (2021[12])).

Definitions

Active population (labour force) is the total number of employed and unemployed persons, in accordance with the definition in the Labour Force Survey.

Age groups: Adults refer to 25-64 year-olds; younger adults refer to 25-34 year-olds.

Educational attainment refers to the highest level of education successfully completed by an individual.

Employed individuals are those who, during the survey reference week, were either working for pay or profit for at least one hour or had a job but were temporarily not at work. The employment rate refers to the number of persons in employment as a percentage of the population.

EU-LFS countries are all countries for which data on recent graduates from the European Union Labour Force Survey are used. These are the following 26 EU countries: Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey; plus the United Kingdom.

Inactive individuals are those who, during the survey reference week, were neither employed nor unemployed. Individuals enrolled in education are also considered as inactive if they are not looking for a job. The inactivity rate refers to inactive persons as a percentage of the population (i.e. the number of inactive people is divided by the number of all working-age people).

Levels of education: See the Reader’s Guide at the beginning of this publication for a presentation of all ISCED 2011 levels.

Unemployed individuals are those who, during the survey reference week, were without work, actively seeking employment and currently available to start work. The unemployment rate refers to unemployed persons as a percentage of the labour force (i.e. the number of unemployed people is divided by the sum of employed and unemployed people).

Methodology

For information on methodology, see Indicator A1.

Data on the education and labour-force status of recent graduates by years since graduation are from the EU-LFS for all countries participating in this survey. Different graduation cohorts have been combined (cross-cohort analysis) for the retrospective analysis of the school-to-work transitions over a period of five years following their graduation. The most important drawback of the data source is that it does not allow the changes in the education and labour-force status to be tracked between the assessment points in time. The data from the EU-LFS have been complemented by data from administrative source and graduate or non-graduate surveys for non-EU-LFS countries. The recent graduate cohorts have been restricted to adults who were 15-34 years old at the time of graduation.

When interpreting the results on subnational entities, readers should take into account that the population size of subnational entities can vary widely within countries.

Please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics (OECD, 2018[13]) for more information and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Source

For information on sources, see Indicator A1.

Data on subnational regions for selected indicators are available in the OECD Regional Statistics (database) (OECD, 2021[12]).

References

[1] Arntz, M., T. Gregory and U. Zierahn (2016), “The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries: A comparative analysis”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 189, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jlz9h56dvq7-en.

[9] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2017), Second European Union Minorities and Discrimination Survey: Main Results, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, http://dx.doi.org/10.2811/268615.

[7] OECD (2021), “Education and earnings”, Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_EARNINGS.

[5] OECD (2021), “Educational attainment and labour-force status”, Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?datasetcode=EAG_NEAC.

[12] OECD (2021), “Regional education”, OECD Regional Statistics (database), https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/213e806c-en (accessed on 25 June 2021).

[2] OECD (2021), The state of global education - 18 months into the pandemic, OECD Publishing Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1a23bb23-en.

[11] OECD (2020), Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/69096873-en.

[3] OECD (2020), International Migration Outlook 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ec98f531-en.

[6] OECD (2020), OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1686c758-en.

[13] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[8] OECD (2017), International Migration Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2017-en.

[10] OECD (2017), International Migration Outlook 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2017-en.

[4] OECD (2014), Is migration good for the economy?, No. 2, OECD, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/migration/OECD%20Migration%20Policy%20Debates%20Numero%202.pdf.

Indicator A3 tables

Tables Indicator A3. How does educational attainment affect participation in the labour market?

|

Table A3.1 |

Employment rates of 25-64 year-olds, by educational attainment (2020) |

|

Table A3.2 |

Trends in employment rates, by educational attainment and age group (2019 and 2020) |

|

Table A3.3 |

Trends in unemployment and inactivity rates of 25-34 year-olds (2019 and 2020) |

|

Table A3.4 |

Employment rates of native- and foreign-born 25-64 year-olds, by age at arrival in the country and educational attainment (2020) |

|

WEB Table A3.5 |

Unemployment rates of young adults who have recently completed education, by educational attainment and years since graduation (2018) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2021. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table A3.1. Employment rates of 25-64 year-olds, by educational attainment (2020)

Percentage of employed 25-64 year-olds among all 25-64 year-olds

Note: In most countries, data refer to ISCED 2011. For India and Saudi Arabia, data refer to ISCED-97. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns are available at: http://stats.oecd.org/, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Year of reference differs from 2020: 2019 for Denmark, India, Japan and Turkey; 2018 for Argentina and the Russian Federation; 2017 for Chile; 2016 for Saudi Arabia.

2. Data for tertiary education include upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary programmes (less than 5% of adults are in this group).

3. Data for upper secondary attainment include completion of a sufficient volume and standard of programmes that would be classified individually as completion of intermediate upper secondary programmes (12% of adults aged 25-64 are in this group).

Source: OECD/ILO (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A3.2. Trends in employment rates, by educational attainment and age group (2019 and 2020)

Percentage of employed adults among all adults in a given age group

1. Data for tertiary education include upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary programmes (less than 5% of the adults are in this group).

2. Data for upper secondary attainment by programme orientation include completion of a sufficient volume and standard of programmes that would be classified individually as completion of intermediate upper secondary programmes (12% of adults aged 25-64 are in this group).

Source: OECD/ILO (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A3.3. Trends in unemployment and inactivity rates of 25-34 year-olds (2019 and 2020)

Inactivity rates are measured as a percentage of all 25-34 year-olds; unemployment rates as a percentage of 25-34 year-olds in the labour force

1. Data for tertiary education include upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary programmes (less than 5% of the adults are in this group).

2. Data for upper secondary attainment by programme orientation include completion of a sufficient volume and standard of programmes that would be classified individually as completion of intermediate upper secondary programmes (12% of adults aged 25-64 are in this group).

Source: OECD/ILO (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table A3.4. Employment rates of native- and foreign-born 25-64 year-olds, by age at arrival in the country and educational attainment (2020)

Percentage of employed 25-64 year-olds among all 25-64 year-olds

Note: In most countries data refer to ISCED 2011. For Indonesia and Saudi Arabia data refer to ISCED-97. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns are available at http://stats.oecd.org/, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Year of reference differs from 2020: 2019 for Australia; 2017 for Denmark, Germany and Ireland; 2015 for Chile.

2. Data for upper secondary attainment include completion of a sufficient volume and standard of programmes that would be classified individually as completion of intermediate upper secondary programmes (12% of adults aged 25-64 are in this group).

Source: OECD/ILO (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterA.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.