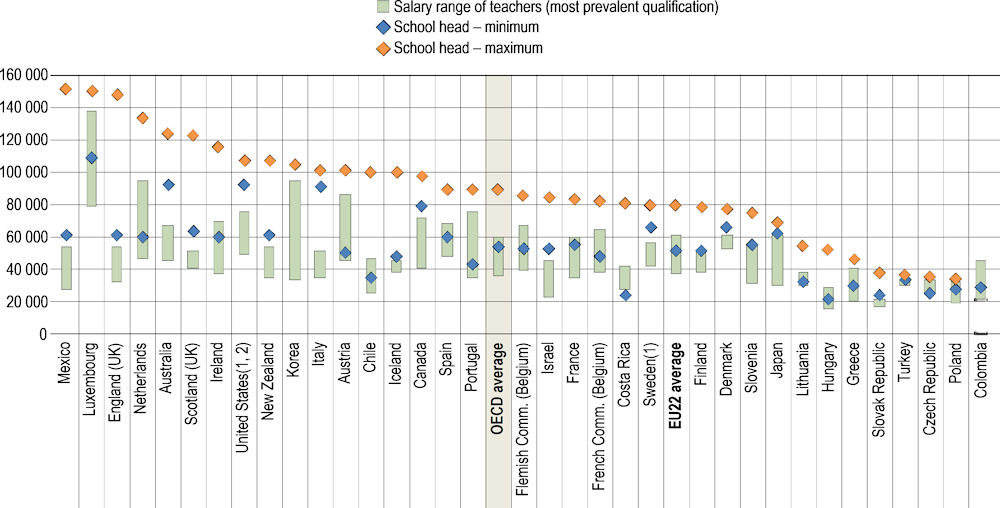

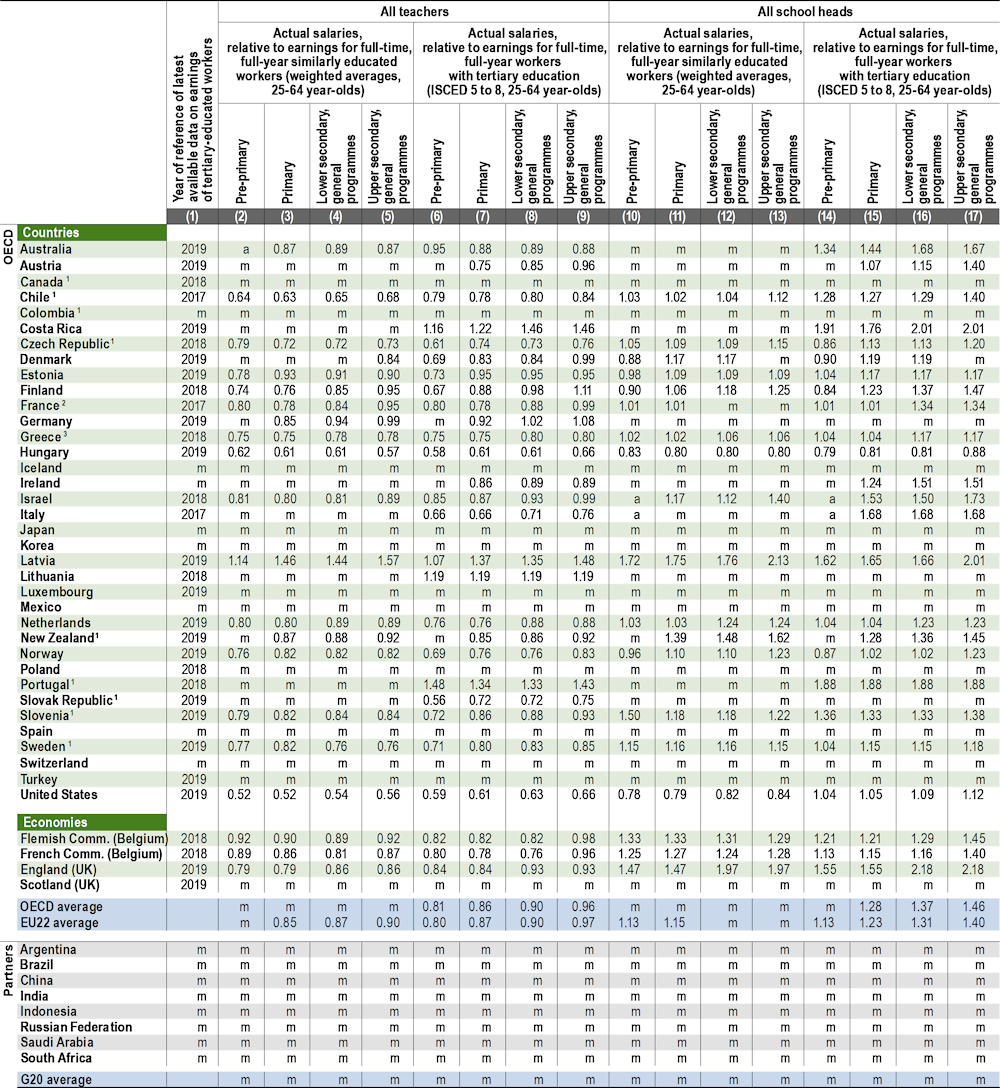

Teachers’ actual salaries at pre-primary, primary and general secondary levels of education are 81-96% of the earnings of tertiary-educated workers on average across OECD countries and economies.

The actual salaries of male and female teachers are very similar (a difference of less than 2% on average). However, male lower secondary teachers’ actual salaries are around 20% lower than the earnings of tertiary-educated male workers whereas female lower secondary teachers earn 3% more than their peers. This shows that the teaching profession may be more attractive to women than to men, compared to other professions, but it also reflects the persistent gender gap in earnings in the labour market.

On average across OECD countries and economies, primary and secondary school heads’ actual salaries are at least 28% higher than the earnings of tertiary-educated workers.

Education at a Glance 2021

Indicator D3. How much are teachers and school heads paid?

Highlights

Context

The salaries of school staff, and in particular teachers and school heads, represent the largest single cost in formal education. Teachers’ salaries have also a direct impact on the attractiveness of the teaching profession. They influence decisions to enrol in teacher education, to become a teacher after graduation, to return to the teaching profession after a career interruption and whether to remain a teacher. In general, the higher teachers’ salaries, the fewer people choose to leave the profession (OECD, 2005[1]). Salaries can also have an impact on the decision to become a school head.

The global pandemic creates new challenges for the economy and education systems, and will also put pressure on public expenditure. Compensation and working conditions are important for attracting, developing and retaining skilled and high‑quality teachers and school heads. It is important for policy makers to carefully consider the salaries and career prospects of teachers as they try to ensure both high-quality teaching and sustainable education budgets (see Indicators C6 and D2).

Statutory salaries are just one component of teachers’ and school heads’ total compensation. Other benefits, such as regional allowances for teaching in remote areas, family allowances, reduced rates on public transport and tax allowances on the purchase of instructional materials may also form part of teachers’ total remuneration. In addition, there are large differences in taxation and social benefits systems across OECD countries. This, as well as potential comparability issues related to data collected (see Box D3.1 of Education at a Glance 2019 (OECD, 2019[2]), Box D3.1 and Annex 3) and the fact that data collected only cover public educational institutions, should be kept in mind when analysing teachers’ salaries and comparing them across countries.

Other findings

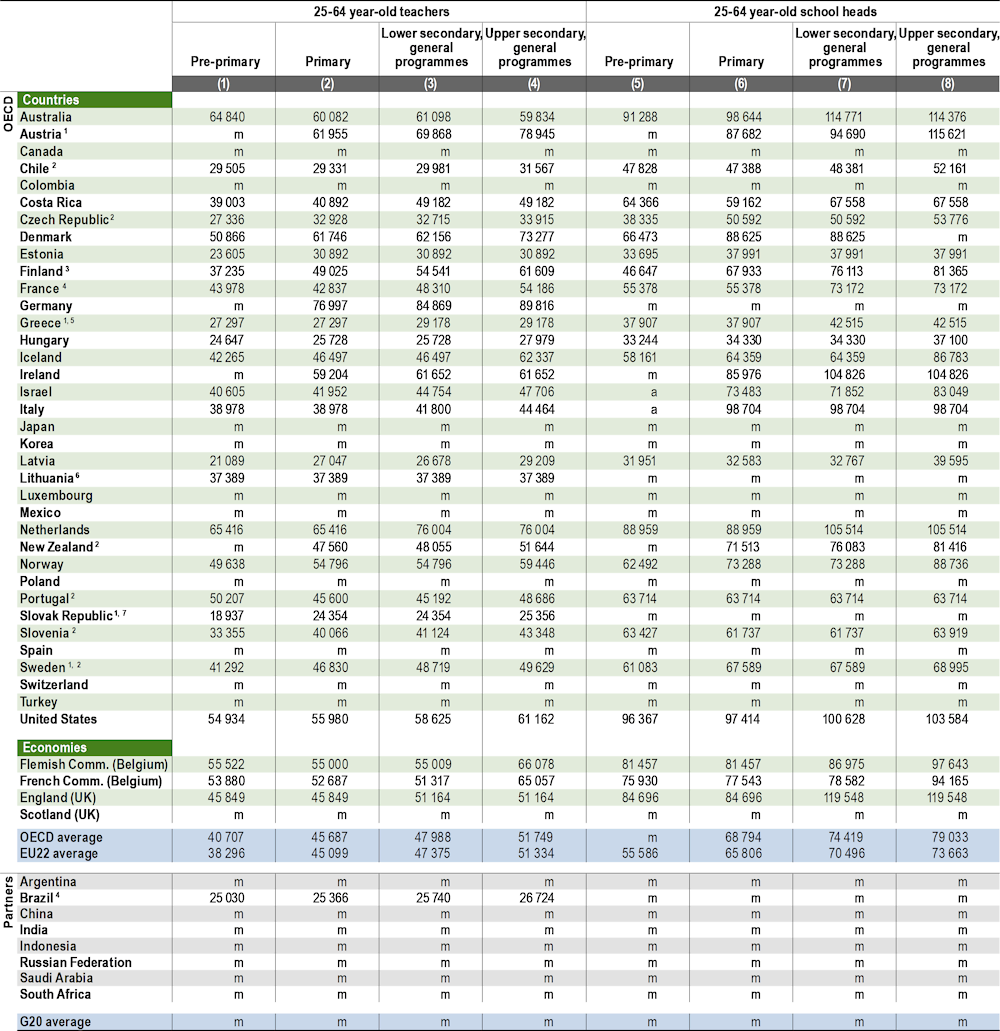

In most OECD countries and economies, the salaries of teachers and school heads increase with the level of education they teach. School heads’ actual salaries are more than 51% higher on average than those of teachers across primary and secondary education in OECD countries and economies.

Between 2005 and 2020, on average across OECD countries and economies with available data for all reference years, the statutory salaries of teachers with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications increased by 3% at primary level, 4% at lower secondary level (general programmes) and 2% at upper secondary level (general programmes).

Between 2010 and 2019, on average across OECD countries and economies with available data for all reference years, the actual salaries of 25-64 year-old teachers increased by 11% at pre-primary level, 9% at primary, 11% at lower secondary and 10% at upper secondary.

School heads are less likely than teachers to receive additional compensation for performing responsibilities over and above their regular tasks. School heads and teachers working in disadvantaged or remote areas are rewarded with additional compensation in half of the OECD countries and economies with available data.

Note: Data refer to ratio of salary, using annual average salaries (including bonuses and allowances) of teachers and school heads in public institutions relative to the earnings of workers with similar educational attainment (weighted average) and to the earnings of full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education.

1. Year of reference for salaries of teachers/school heads differs from 2020. See Table D3.3 for more information.

2. Data on earnings for full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education refer to the United Kingdom.

3. Data on earnings for full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education refer to Belgium.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of the ratio of teachers' salaries to earnings for full-time, full-year tertiary-educated workers aged 25-64.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D3.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Analysis

Salaries of teachers

Teachers’ statutory salaries can vary according to a number of factors, including the level of education taught, their qualification level, and their level of experience or the stage of their career.

Data on teachers’ salaries are available for three qualification levels: minimum, most prevalent and maximum. The salaries of teachers with the maximum qualifications can be substantialy higher than those with the minium qualfications. However, in some countries, very few teachers hold the minimum or maximum qualifications. In many countries, most teachers have the same qualification level. For these reasons, the following analysis on statutory salaries focuses on teachers who hold the most prevalent qualifiations.

Statutory salaries of teachers

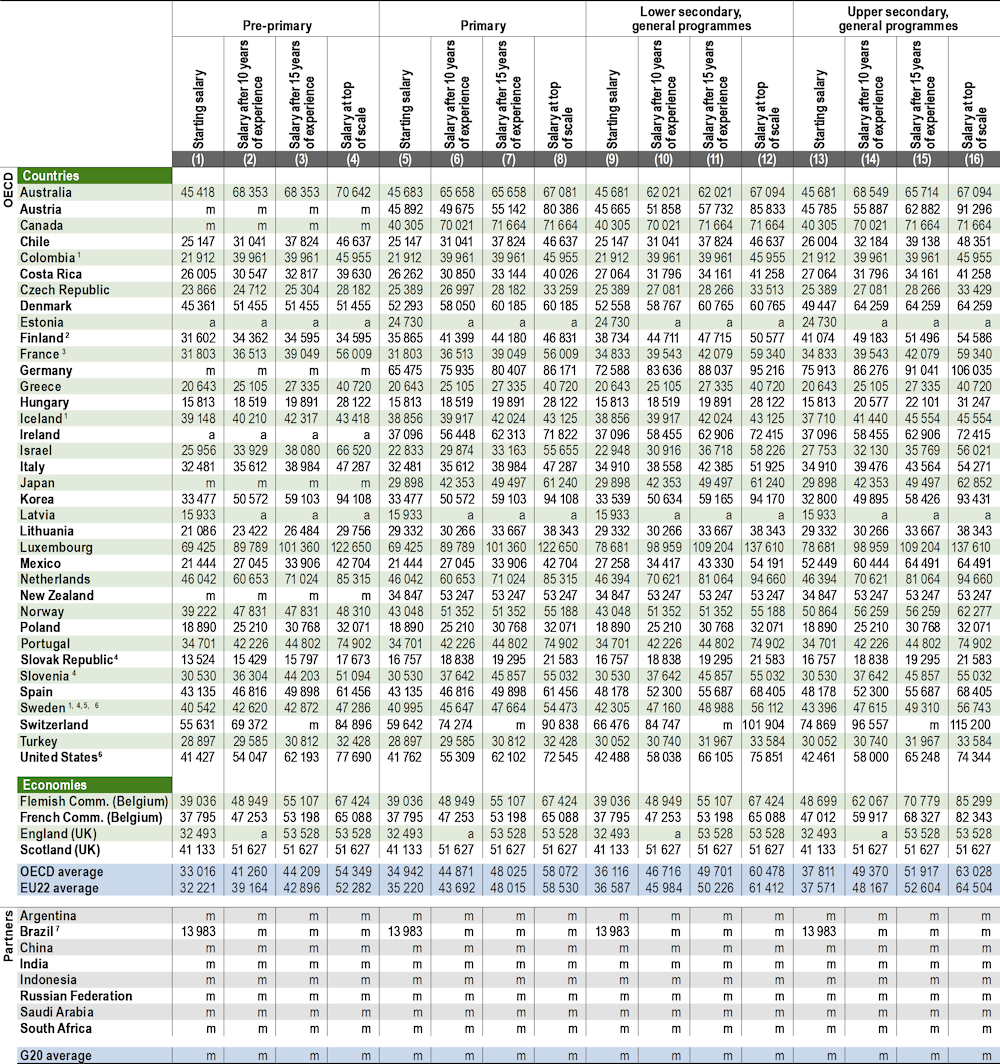

Teachers’ salaries vary widely across countries. The salaries of lower secondary school teachers with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications (a proxy for mid-career salaries of teachers) range from less than USD 20 000 in Hungary and the Slovak Republic to more than USD 70 000 in Canada, Germany and the Netherlands, and they exceed USD 100 000 in Luxembourg (Table D3.1).

In most countries and economies with available information, teachers’ salaries increase with the level of education they teach. The salaries of teachers with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications vary from USD 44 209 at the pre-primary level to USD 48 025 at the primary level, USD 49 701 at the lower secondary level and USD 51 917 at the upper secondary level. In the Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, Denmark, and Lithuania, upper secondary teachers with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications earn between about 25% and 30% more than pre‑primary teachers with the same experience, while in Finland they earn around 50% more. In Finland, the difference is mainly explained by the gap between pre-primary and primary teachers’ salaries. In the Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, teachers’ salaries at upper secondary level are significantly higher than at other levels of education (Table D3.1).

The difference in salaries between teachers at pre-primary and upper secondary levels is less than 5% in Chile, Costa Rica, Slovenia, Turkey and the United States, and teachers earn the same salary irrespective of the level of education taught in Colombia, England (United Kingdom), Greece, Poland, Portugal and Scotland (United Kingdom) (Table D3.1).

However, in Israel, the salary of a pre-primary teacher is about 6% higher than the salary of an upper secondary teacher. This difference results from the “New Horizon” reform, begun in 2008 and almost fully implemented by 2014, which increased salaries for pre-primary, primary and lower secondary teachers. Another reform, launched in 2012 with implementation ongoing, aims to raise salaries for upper secondary teachers.

Salary structures usually define the salaries paid to teachers at different points in their careers. Deferred compensation, which rewards employees for staying in organisations or professions and for meeting established performance criteria, is also used in teachers’ salary structures. OECD data on teachers’ salaries are limited to information on statutory salaries at four points of the salary scale: starting salaries, salaries after 10 years of experience, salaries after 15 years of experience and salaries at the top of the scale. Countries that are looking to increase the supply of teachers, especially those with an ageing teacher workforce and/or a growing school-age population, might consider offering more attractive starting wages and career prospects. However, to ensure a well-qualified teaching workforce, efforts must be made not only to recruit and select, but also to retain the most competent and best-qualified teachers. Weak financial incentives may make it more difficult to retain teachers as they approach the peak of their earnings. However, there may be some benefits to compressed pay scales. For example, organisations with smaller differences in salaries among employees may enjoy more trust, freer flows of information and more collegiality among co-workers.

In OECD countries, teachers’ salaries for a given qualification level rise during the course of their career, although the rate of change differs across countries. For lower secondary teachers with the most prevalent qualifications, average statutory salaries are 29% higher than average starting salaries after 10 years of experience, and 38% higher after 15 years of experience. Average salaries at the top of the scale (reached after an average of 25 years) are 67% higher than the average starting salaries. The difference in salaries by level of experience varies largely between countries. At the lower secondary level, salaries at the top of the scale exceed starting salaries by less than 20% in Denmark, Iceland, and Turkey, whereas salaries at the top of the scale are more than 2.8 times starting salaries in Korea (after at least 37 years of experience).

Note: Actual salaries include bonuses and allowances.

1. Actual base salaries.

2. Salaries at the top of the scale and the minimum qualifications, instead of the maximum qualifications.

3. Salaries at the top of the scale and the most prevalent qualifications, instead of the maximum qualifications.

4. Includes the average of fixed bonuses for overtime hours.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of starting salaries for lower secondary teachers with the minimum qualifications.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D3.3 and Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

The range of salaries within countries also increases as different qualification levels of teachers can be associated to different salary scales. At the lower secondary level, on average across OECD countries and economies, the statutory salary of a teacher with the most prevalent qualifications and 15 years of experience is 40% higher than that of a teacher starting out with the minimum qualifications. At the top of the salary range with the maximum qualifications, the average statutory salary is 85% higher than the average starting salary with the minimum qualifications (Table D3.1 and Figure D3.2).

In terms of the maximum statutory salary range (from starting salaries with the minimum qualifications to maximum salaries with the maximum qualifications), most countries and economies with starting salaries below the OECD average also have maximum salaries that are below the OECD average. At the lower secondary level, the most notable exceptions are Colombia, England (United Kingdom), Korea and Mexico, where starting salaries are at least 5% lower (8-38% lower) than the OECD average, but maximum salaries are at least 21% higher. These differences may reflect the different career paths available to teachers with different qualifications in these countries. The opposite is true in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Scotland (United Kingdom) and Sweden, where starting salaries are between 7% and 48% higher than the OECD average, while maximum salaries are at least 5% lower than the OECD average (8-30% lower). This results from relatively flat/compressed salary scales in a number of these countries (Figure D3.2).

In contrast, for lower secondary teachers, maximum salaries (at the top of the scale, with the maximum qualifications) are at least double the starting salaries (for teachers with minimum qualifications) in Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, England (United Kingdom), France, the French and Flemish Communities of Belgium, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, and Portugal (Figure D3.2).

The salary premium for teachers with the maximum qualifications at the top of the pay scales (which may correspond to a very small proportion of teachers), and those with the most prevalent qualifications and 15 years of experience, also varies across countries. At lower secondary level, the pay gap is less than 10% in nine OECD countries and economies, while it exceeds 60% in Chile, Colombia, France, Hungary, Israel, Mexico and Portugal (Figure D3.2 and Table D3.1).

Actual salaries of teachers

In addition to statutory salaries, teachers’ actual salaries include work-related payments, such as annual bonuses, results-related bonuses, extra pay for holidays, sick-leave pay and other additional payments (see Definitions section). These bonuses and allowances can represent a significant addition to base salaries. Actual average salaries are influenced by the prevalence of bonuses and allowances in the compensation system. Differences between statutory and actual average salaries are also linked to the distribution of teachers by years of experience and qualifications, as these two factors have an impact on their salary levels.

Across OECD countries and economies, in 2020, the average actual salaries of teachers aged 25-64 were USD 40 707 at pre-primary level, USD 45 687 at primary level, USD 47 988 at lower secondary level and USD 51 749 at upper secondary level.

Note: Includes only teachers and school heads in public institutions

1. Year of reference differs from 2020. See Table D3.3 for more information.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of actual salaries of school heads.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D3.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

There are 27 OECD countries and economies with available data on both the statutory salaries of teachers with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications and the actual salaries of 25-64 year-old teachers for at least one level of education. Actual annual salaries are 10% higher than statutory salaries in six of these countries and economies at pre‑primary level and in 11 of these countries and economies at upper secondary level. This shows the effect of additional allowances (included in data for actual but not statutory salaries) and of differing levels of experience in the teaching populations of countries (Table D3.3 and Figure D3.3).

It is also possible to examine how teachers’ actual salaries compare to the minimum and maximum salaries. This gives an indication of the distribution of teachers between the minimum and maximum salary levels. At the lower secondary level, actual salaries of 25-64 year-old teachers are, on average, 35% higher than the statutory starting salary for teachers with the minimum qualification. This difference is less than 20% in Chile, Denmark, Germany, Italy and Sweden, suggesting that many teachers are being paid close to the minimum salary. On the contrary, in Brazil, Costa Rica, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Latvia and the Netherlands, the difference is over 60%, suggesting that most teachers are paid much more than the minimum salary. A similar analysis comparing actual salaries with the maximum salary shows that actual salaries of 25-64 year-old teachers are, on average, 27% lower than the statutory salary at the top of the scale for teachers with the maximum qualification. The difference is greater than 35% in Chile, England (United Kingdom), the Flemish and French Communities of Belgium, Hungary and Portugal, suggesting that few teachers are paid at or near the maximum salary level. In four countries, average actual salaries of teachers are greater than the statutory salary at the top of the scale for teachers with the maximum qualification (Costa Rica, Denmark, Finland and Iceland), which implies that allowances awarded in addition to the statutory salary have a substantial effect on teachers’ take home pay (Figure D3.2).

Education systems compete with other sectors of the economy to attract high-quality graduates as teachers. Research shows that salaries and alternative employment opportunities are important factors in the attractiveness of teaching (Johnes and Johnes, 2004[3]). Teachers’ salaries relative to other occupations with similar education requirements, and their likely growth in earnings, may have a huge influence on a graduate’s decision to become a teacher and stay in the profession.

In most OECD countries and economies, a tertiary degree is required to become a teacher, at all levels of education, meaning that the likely alternative to teacher education is a similar tertiary education programme. Thus, to interpret salary levels in different countries and reflect comparative labour-market conditions, actual salaries of teachers are compared to the earnings of other tertiary-educated professionals: 25-64 year-old full-time, full-year workers with a similar tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 to 8). Moreover, to ensure that comparisons between countries are not biased by differences in the distribution of tertiary attainment level among teachers and tertiary-educated workers more generally, teachers’ actual salaries are also compared to a weighted average of earnings of similarly educated workers (the earnings of similarly educated workers are weighted by the proportion of teachers with similar tertiary attainment; see Table X2.8 in Annex 2 for the proportion of teachers by attainment level, and Methodology section for more details).

Among the 21 countries and economies with available data (for at least one level), teachers’ actual salaries amount to 65% or less of the earnings of similarly educated workers in Chile (pre-primary, primary and lower secondary), Hungary, and the United States. Very few countries and economies have teachers’ actual salaries that reach or exceed those of similarly educated workers. However, upper secondary teachers in Germany have actual salaries that are the same as those of similarly educated workers, and actual salaries exceed by at least 14% those of similarly educated workers in Latvia (Table D3.2).

Considering how few countries have available data for this relative measure of teachers’ salaries, a second benchmark is based on the actual salaries of all teachers relative to earnings for full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education (ISCED levels 5 to 8). Against this benchmark, teachers’ actual salaries relative to other tertiary-educated workers increase with higher education levels. On average, pre-primary teachers’ salaries amount to 81% of the full-time, full-year earnings of tertiary-educated 25-64 year-olds. Primary teachers earn 86% of this benchmark salary, lower secondary teachers 90% and upper secondary teachers 96% (Table D3.2).

In almost all countries and economies with available information, and at almost all levels of education, teachers’ actual salaries are lower than those of tertiary-educated workers. The lowest relative salaries are at pre-primary level: in the Slovak Republic, pre-primary teachers’ salaries are 56% of those of tertiary-educated workers, in Hungary they are 58% and in the United States they are 59%. However, in some countries, teachers earn more than tertiary-educated adults, either at all levels of education (Costa Rica, Latvia, Lithuania and Portugal) or only at some levels (at upper secondary level in Finland and at secondary level in Germany). In Costa Rica (at the secondary level), Latvia (at primary and secondary levels) and Portugal, teachers earn at least 30% more than tertiary-educated workers (Table D3.2 and Figure D3.1).

Box D3.1. Comparability issues related to relative salaries of teachers and school heads

Meaningful international comparisons rely on the provision and implementation of rigorous definitions and a related statistical methodology. In view of the diversity across countries of both their education and their teacher compensation systems, adhering to these guidelines and methodology is not always straightforward. Some caution is therefore required when interpreting these data.

The relative salaries measure divides the salaries of teachers or school heads (numerator) by the earnings of comparable workers (denominator). Two different versions of the measure are presented in Table D3.2. The first simply divides teachers’ or school heads’ salaries by the earnings of tertiary-educated workers; the second weights the earnings of workers so that they reflect the distribution of educational attainment among teachers or school heads. This avoids potential comparability issues related to different distributions of attainment among teachers or school heads compared with tertiary-educated workers.

Both versions of the relative salaries measure are still subject to biases due to differences in the characteristics, working patterns and remuneration systems of teachers and other workers. Five potential sources of bias in the comparison of teachers’ salaries to tertiary-educated workers are described below.

Including teachers in the earnings of tertiary-educated workers

The earnings of tertiary-educated workers also include the earnings of teachers. The relative size of the teaching workforce in the labour market as a whole, as well as the level of teachers’ earnings compared to those of other tertiary-educated workers, has a potential impact on the level of earnings of tertiary-educated workers used to compute relative salaries. As a consequence, this also affects the measure of teachers’ relative salaries. However, a recent analysis among five volunteer countries with available data that allow excluding from earnings data those of teachers showed that removing teachers from the earnings of tertiary-educated workers tended to lead to only a small change in relative salaries (from 0.01 to 0.04 percentage points depending on the level of education and age group). There is then little evidence to suggest that including teachers in the earnings data significantly biases the measure of relative salaries.

Part-time work

The relative measures of salaries are based on the salaries and earnings of full-time teachers and the earnings of full-time workers. However, a share of teachers, and workers more generally, work on a part-time basis during the year. Differences in the frequency of part-time work between teachers and workers could introduce a bias into the measure of relative salaries, as it will impact in a different way on the average salaries of teachers and the average earnings of tertiary-educated workers. It is worth noting that part-time work might be more common in education than in the rest of the labour market, not least because women make up a large proportion of teachers in most OECD countries and they are more likely to work part time.

The wage penalty associated with part-time work is a well-established phenomenon and is often one of the reasons for women’s lower salaries (Matteazzi, Pailhé and Solaz, 2018[4]). However, it might be limited or even non-existent in education in some countries. For example, this is the case in the Netherlands in primary education and, to a lesser extent, in secondary education. Hourly salaries are identical for part-time and full-time teachers, due to the collective labour agreements in those sectors. This is not only true for statutory salaries (based on collective labour agreements), but also for actual salaries.

Part-year work

Not only is the measure of teachers’ relative salaries based on a comparison with full-time workers, but also with full-year workers. This measure aims to compare full-time, full-year teachers to full-time, full-year tertiary-educated workers. However, there may be a bias in the comparison due to the fact that a proportion of teachers in a few countries (such as the United States) are paid for a contract that spans less than a 12-month year, reflecting only the months of the school year. Therefore, teachers’ salaries may not be a true reflection of teachers’ earnings over a full year. In some countries, teachers may have other earnings from non-teaching jobs that are excluded from the calculation. The potential underestimation of teachers’ earnings over the year may bias the comparison with the earnings of tertiary-educated workers.

Different sources of data for teachers’ salaries and workers’ earnings

The sources of data used to report teachers’ salaries and the earnings of workers may differ, at least partly. This may result in differences in the type of data and the methodology used to report them: statutory and actual salaries for teachers, compared with actual earnings for workers. For example, in several countries, including the Netherlands and the United States, earnings data are at least partially based on the Labour Force Survey (LFS) of that country. However, the teachers’ salary data often come from regulations, collective agreements, administrative sources or sample surveys.

Differences in pension systems between teachers and other workers

In many countries, teachers in public institutions have substantial pension contributions paid by their employer, but a relatively low salary compared to the private sector. In contrast, private sector employees may have higher salaries, but they may also have to make their own pension arrangements. Differences in pension systems between the public and private sector, and between countries, may affect the comparability of salary and earnings data, and therefore the comparability of the measure of teachers’ relative salaries.

Pensions are only taken into account in data on salaries of teachers through the social contributions that are included/excluded from the amounts reported. Some countries may report data on salaries in a different way due to data limitations.

For more information on comparability issues, see Box D3.1 of Education at a Glance 2019 (OECD, 2019[2]) and the country-specific notes in Annex 3.

Salaries of school heads

The responsibilities of school heads may vary between countries and also within countries, depending on the schools they lead. School heads may exercise educational responsibilities (which may include teaching tasks, but also responsibility for the general functioning of the institution in areas such as the timetable, implementation of the curriculum, decisions about what is taught, and the materials and methods used). They may also have other administrative, staff management and financial responsibilities (see Indicator D4 for more details).

Differences in the nature of the work carried out and the hours worked by school heads (compared to teachers) are reflected in the systems of compensation used within countries (see Tables D4.2 and D4.5 for the working time of teachers and school heads).

Statutory salaries of school heads

School heads may be paid according to a specific salary range and may or may not receive a school-head allowance on top of their statutory salaries. However, they can also be paid in accordance with the salary scale(s) of teachers and receive an additional school-head allowance. The use of teachers’ salary ranges may reflect the fact that school heads are initially teachers with additional responsibilities. At lower secondary level, school heads are paid according to teachers’ salary scales with a school-head allowance in 13 out of the 33 countries and economies with available information, and according to a specific salary range in the other 20 countries and economies. Of these, 13 countries and economies have no specific school-head allowance and 7 countries have a school-head allowance included in the salary. The amounts payable to school heads (through statutory salaries and/or school-head allowances) may vary according to criteria related to the school(s) where the school head is based (for example the size of the school based on the number of students enrolled, or the number of teachers supervised). They could also vary according to the individual characteristics of the school heads themselves, such as the duties they have to perform or their years of experience (Table D3.12, available on line).

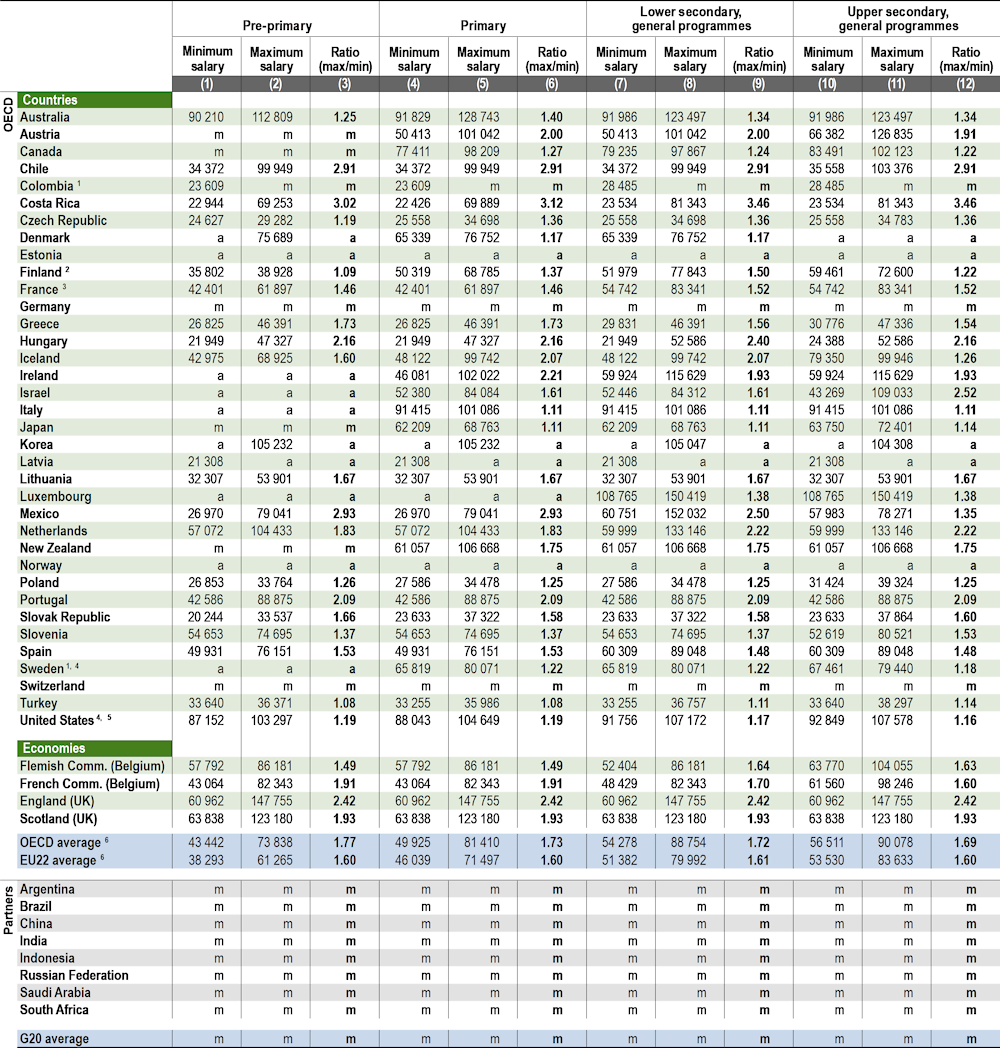

Considering the large number of criteria involved in the calculation of school heads’ statutory salaries, the statutory salary data for school heads focus on the minimum qualification requirements to become a school head, and Table D3.4 shows only the minimum and maximum values. Caution is necessary when interpreting these values because salaries often depend on many criteria and as a result, few school heads may earn these amounts.

At lower secondary level, the minimum salary for school heads is USD 54 278 on average across OECD countries and economies, ranging from USD 21 308 in Latvia to USD 108 765 in Luxembourg. The maximum salary is USD 88 754 on average across OECD countries and economies, ranging from USD 34 478 in Poland to USD 152 032 in Mexico. These values should be interpreted with caution, as minimum and maximum statutory salaries refer to school heads in different types of schools. About half of OECD countries and economies have similar pay ranges for primary and lower secondary school heads, while upper secondary school heads benefit from higher statutory salaries on average (Table D3.4).

On average across OECD countries and economies, the maximum statutory salary of a school head with the minimum qualifications is 73% higher than the minimum statutory salary at primary level, 72% higher than the minimum in lower secondary and 69% higher in upper secondary. There are only ten countries or economies where school heads at the top of the scale can expect to earn twice the statutory starting salary in at least one of these levels of education; in Costa Rica, they can even expect to earn more than three times the starting salary (Table D3.4).

Figure D3.4. Minimum and maximum statutory salaries for lower secondary teachers and school heads (2020)

Annual statutory salaries of teachers and school heads, in equivalent USD converted using PPPs

Note: salaries in public institutions, for teachers with the most prevalent qualifications at a given level of education and for school heads with minimum qualifications.

1. Actual base salaries.

2. Minimum salary refers to the most prevalent qualification (master’s degree or equivalent) and maximum salary refers to the highest qualification (education specialist or doctoral degree or equivalent).

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of maximum salaries of school heads.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D3.4. and Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

The minimum statutory salaries for school heads with the minimum qualifications are higher than the starting salaries of teachers, except in Costa Rica. The difference between minimum salaries for school heads (with the minimum qualifications) and starting salaries for teachers (with the most prevalent qualifications) increases with level of education: they are 32% higher on average across OECD countries and economies at pre-primary level, 42% at primary level, 49% at lower secondary level and 49% at upper secondary level. In a number of countries, the minimum statutory salary for school heads is higher even than the maximum salary for teachers. This is the case at lower secondary level in Australia, Denmark, England (United Kingdom), Finland, Iceland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Scotland (United Kingdom), the Slovak Republic, Sweden and the United States (Figure D3.4).

Similarly, the maximum statutory salaries for school heads are higher than the maximum salaries for teachers for all OECD countries and economies with available data. At lower secondary level, the maximum statutory salary of a school head is 48% higher than the salary of teachers at the top of the scale (with the most prevalent qualifications), on average across OECD countries and economies. The maximum statutory salaries of school heads in Chile, England (United Kingdom), Iceland, Mexico, New Zealand and Scotland (United Kingdom) are more than twice statutory teachers’ salaries at the top of the scale (Figure D3.4).

Actual salaries of school heads

Average actual salaries for school heads aged 25-64 ranged from USD 68 794 at primary level to USD 74 419 at lower secondary level and USD 79 033 at upper secondary level (Table D3.3, see Box D3.1 for variations at subnational level).

The actual salaries of school heads are higher than those of teachers, and the premium increases with levels of education. On average across OECD countries and economies, school heads’ actual salaries in 2020 were 51% higher than those of teachers at primary level. The premium is 55% at lower secondary level and 53% at upper secondary level. The difference between the actual salaries of school heads and teachers varies widely between countries and between levels of education. The countries and economies with the highest premium for school heads over teachers are England (United Kingdom) (secondary levels) and Italy (primary and secondary levels), where school heads’ actual salaries are more than twice those of teachers. The lowest premiums, of less than 25%, are in Estonia (at primary and secondary) and Latvia (primary and lower secondary). Other countries show a steep rise in salaries of school heads compared to teachers at the secondary level, while there is a more moderate difference at primary level. For example, in the Czech Republic, school heads’ actual salaries are 40% higher than teachers’ at pre-primary level, but the difference is 55% at lower secondary and 59% at upper secondary level. In Costa Rica, Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia, the difference is much larger at pre-primary level than at primary and lower secondary levels (Table D3.3).

The career prospects of school heads and their relative salaries are also a signal of the career progression pathways available to teachers and the compensation they can expect in the longer term. School heads earn more than teachers and, unlike teachers, typically earn more than similarly educated workers at all of the levels of education considered. This difference tends to increase with the level of education. Among the 19 OECD countries and economies with available data (for at least one level), it is only school heads in Hungary and the United States and pre-primary school heads in Denmark whose actual salaries are at least 5% lower than the earnings of similarly educated workers. In contrast, school heads’ salaries are at least 40% higher than those of similarly educated workers in England (United Kingdom) and New Zealand (secondary) (Table D3.2).

As with teachers, there are only a few countries with available data for this relative measure of school heads’ salaries. Hence, a second benchmark is based on the actual salaries of all school heads, relative to earnings for full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education. Using this measure, on average across OECD countries and economies, school heads earn 28% more than tertiary-educated adults at primary level, 37% more at lower secondary level and 46% more at upper secondary level. School heads earn less than tertiary‑educated adults only in the Czech Republic (pre-primary), Denmark (pre-primary), Finland (pre-primary), Hungary and Norway (pre‑primary) (Table D3.2).

Box D3.2. Subnational variations in teachers' and school heads’ salaries at pre-primary, primary and secondary levels

In each country, teachers’ statutory salaries can vary according to the level of education and their level of experience. Salaries can also vary significantly across subnational entities within each country, especially in federal countries where salary requirements may be defined at the subnational level. Subnational data provided by four countries (Belgium, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States) illustrate these variations at the subnational level.

In these four countries, statutory salaries vary to a differing extent between subnational entities, depending on the stage teachers have reached in their careers. In 2020 in Belgium, for example, the annual starting salary of a primary school teacher varied by only 3% (USD 1 231), from USD 37 795 in the French Community to USD 39 036 in the Flemish Community. In comparison, subnational variation was the largest in the United States, where the starting salary of a primary school teacher varied by 81% (USD 27 438) across subnational entities, ranging from USD 33 968 in Oklahoma to USD 61 406 in New York. Starting salaries for lower secondary and upper secondary teachers varied the least in Belgium (by 3-4%) and the most in Canada (by 77%).

In Belgium, the variation in statutory salaries between subnational entities remains relatively consistent across all levels of education and stages of teachers’ careers. In contrast, in both Canada and the United Kingdom, the variation across subnational entities is similar at different levels of education, but greater for starting salaries than for salaries at the top of the scale. For example, at the upper secondary level, starting salaries in the United Kingdom varied by 38% (USD 11 345) between subnational entities (from USD 29 789 to USD 41 133), while salaries at the top of the salary scale varied by only 6% (USD 2 811, from USD 50 717 to USD 53 528). In the United States, there was no clear pattern in the extent of the variation of statutory salaries across subnational entities at different levels of education and stages of teachers’ careers. At the lower secondary level, the variation was the smallest for starting salaries, ranging from USD 35 334 to USD 59 114 (a difference of 67%, or USD 23 780) and the largest for salaries at the top of the salary scale, ranging from USD 44 337 to USD 111 425 (a difference of 151%, or USD 67 088).

There are also large subnational variations in actual salaries of teachers and school heads across the three countries (Belgium, the United Kingdom and the United States) with available data in 2020. In the United Kingdom, the subnational variation in actual salaries was greater for school heads than for teachers. For example, at the upper secondary level, teachers’ salaries in the United Kingdom (for the three subnational entities with available data) ranged from USD 48 099 in Wales to USD 53 826 in Northern Ireland, a difference of 12% or USD 5 727. In comparison, school heads’ salaries ranged from USD 97 249 in Northern Ireland to USD 119 548 in England, a difference of 23% or USD 22 299. Subnational variation in actual salaries was much smaller for both teachers and school heads in Belgium. For example, the salaries of upper secondary school heads ranged from USD 94 165 in the French Community to USD 97 643 in the Flemish Community, a difference of 4%, or USD 3 478. In the United States, subnational variation in actual salaries is similar for both teachers and school heads, but much larger than in Belgium. For example, the salaries of upper secondary school heads ranged from USD 75 354 in South Dakota to USD 145 482 in New Jersey, a difference of 93%, or USD 70 128.

The extent of the subnational variation in actual salaries (for teachers and school heads) also varies according to level of education. In the United Kingdom (for subnational entities with available data), the subnational variation in school heads’ salaries is largest at lower and upper secondary levels, while subnational variation in teachers’ salaries is similar across levels of education. In the United States, subnational variation in the actual salaries of teachers and school heads was greater at the primary level than at lower and upper secondary levels.

Source: Education at a Glance Database, http://stats.oecd.org.

Salary trends of teachers since 2000

Trends in statutory salaries

Teachers’ statutory salaries increased overall in real terms in most of the countries for which data are available between 2000 and 2020. However, only one in three OECD countries have the relevant data available (the statutory salaries of teachers with the most prevalent qualifications and 15 years of experience) for the whole period with no break in the time series. Among these countries, around two-thirds show an increase over this period and one-third show a decrease.

The biggest decreass in statutory salaries in real terms between 2000 and 2020 were in Greece, where statutory salaries fell by up to 14%. There were also smaller declines in teachers’ statutory salaries in real terms in England (United Kingdom) (1%), France (by about 6%), Italy (less than 0.5%) and Japan (by nearly 10%). Statutory salaries increased by more than 40% for primary and secondary teachers in Ireland and Israel (pre-primary and secondary levels). However, in some countries, an overall increase in teachers’ statutory salaries between 2000 and 2020 includes periods when statutory salaries fell in real terms, particularly from 2010 to 2013 (Table D3.6, available on line).

Over the period 2005 to 2020, for which half of OECD countries and economies have comparable trend data for at least one level of education, around two-thirds of these countries showed an increase in real terms in the statutory salaries of teachers (with 15 years of experience and the most prevalent qualifications). On average across OECD countries and economies with available data for the reference years of 2005 and 2020, statutory salaries increased by about 3% at primary level, 4% at lower secondary level and 2% at upper secondary level. The increase exceeded 20% in Poland at pre-primary, primary and secondary levels (the result of a 2007 government programme that aimed to increase teachers’ statutory salaries successively between 2008 and 2013, and also since 2017, and to improve the quality of education by providing financial incentives to attract high-quality teachers) and also in Australia (pre-primary), Germany (primary and lower secondary), Iceland (pre-primary), Israel, and Norway (at pre-primary) (Table D3.6, available on line).

In most countries, the salary increases were similar across primary, lower secondary and upper secondary levels between 2005 and 2020. However, this is not the case in Israel, where statutory salaries increased by more than 50% at pre‑primary level, 28% at primary level, 42% at lower secondary level and 46% at upper secondary level. This is largely the result of the gradual implementation of the “New Horizon” reform in primary and lower secondary schools, which began in 2008 following an agreement between the education authorities and the Israeli Teachers Union (for primary and lower secondary education). This reform included raising teachers’ pay in exchange for longer working hours (see Indicator D4).

In contrast, statutory salaries have decreased slightly since 2005 in a few countries and economies including France, Hungary (primary and secondary), Italy, Portugal, Spain (secondary) and the United States (primary). They decreased by 9% in Japan and by more than 25% in Greece as the result of reductions in remuneration, the implementation of new wage grids and salary freezes since 2011 (Table D3.6, available on line).

Trends in actual salaries

Teachers’ actual salaries increased overall in real terms in most countries for which data are available between 2010 and 2019. Among countries with available trend data, around three-quarters of countries show an increase over this period and one-quarter show a decrease. However, only one in three OECD countries have available data on actual salaries of teachers aged 25-64 for the whole period with no break in the time series (Table D3.6, available on line).

For the countries with available data (and no breaks in the time series), actual salaries increased between 2010 and 2019 by 11% at pre-primary level, 9% at primary, 11% at lower secondary and 10% at upper secondary. The increase in salaries was over 25% at all levels of education in the Czech Republic, Hungary and Israel. In Sweden, actual salaries increased by 18% at pre-primary level but by over 21% at primary and secondary levels. Actual salaries decreased in six countries and economies in at least one level of education. They fell by more than 8% in real terms in England (United Kingdom) and by 15% in the Flemish Community of Belgium (Table D3.7, available on line).

Note: Data refer to averages computed for OECD countries with available data for all reference years. Statutory salaries refer to teachers with 15 years of experience and the minimum qualification. Actual salaries refer to teachers aged 25-64. OECD averages for statutory salaries and actual salaries are not necessarily computed for the same group of countries.

Source: OECD (2021), Tables D3.6 and D3.7, available on line. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Formation of base salary and additional payments: Incentives and allowances

Statutory salaries, based on pay scales, are only one component of the total compensation of teachers and school heads. School systems also offer additional payments to teachers and school heads, such as allowances, bonuses or other rewards. These may take the form of financial remuneration and/or reductions in the number of teaching hours, and decisions on the criteria used for the formation of the base salary are taken at different decision-making levels (Tables D3.10 and D3.11, available on line).

Criteria for additional payments vary across countries. In the large majority of countries and economies, teachers’ core tasks (teaching, planning or preparing lessons, marking students’ work, general administrative work, communicating with parents, supervising students, and working with colleagues) are rarely compensated through specific bonuses or additional payments (Table D3.8, available on line). Teachers may also be required to have some responsibilities or perform some tasks without additional compensation (see Indicator D4 for the tasks and responsibilities of teachers). Taking on other responsibilities, however, often entails some sort of extra compensation.

At lower secondary level, teachers who participate in school management activities in addition to their teaching duties received extra compensation in three-fifths of the countries and economies with available information.

It is also common to award additional payments, either annual or occasional, when teachers teach more classes or hours than required by their full-time contract, have responsibility as a class or form teacher, or perform special tasks, such as training student teachers (Table D3.8, available on line).

Additional compensation, either in the form of occasional additional or annual payments or through increases in basic salary, is also awarded for outstanding performance to lower secondary teachers in about half of the OECD countries and economies with available data. Additional payments can also include bonuses for special teaching conditions, such as teaching students with special needs in regular schools or teaching in disadvantaged, remote or high-cost areas (Table D3.8, available on line).

There are also criteria for additional payments for school heads, but fewer tasks or responsibilities lead to additional payments compared to teachers. At lower secondary level, only a few countries do not offer any type of additional compensation to their school heads: Australia, Austria, the French Community of Belgium, Hungary and Portugal (Table D3.9, available on line).

Among the 30 countries and economies with available data, around one-quarter provide additional compensation to school heads for participating in management tasks above and beyond their usual responsibilities as school heads or for working overtime. At lower secondary level, about half of the countries and economies (Australia, Austria, Chile, England [United Kingdom], Finland, France, the French Community of Belgium, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Korea, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Switzerland) provide additional compensation for teachers when they take on extra responsibilities, but do not provide any additional payments to school heads (Tables D3.8 and D3.9, available on line). The extent to which teachers receive additional compensation for taking on extra responsibilities and the activities for which teachers are compensated vary across these countries. As with teachers (see above), in some countries, such as Greece, a number of these responsibilities and tasks are considered part of school heads’ duties and so they are not compensated with any extra allowances.

At lower secondary level, school heads are awarded additional compensation for outstanding performance in more than one-third of the countries and economies with available data, just as teachers are. However, Austria, Chile, England (United Kingdom), Israel, Portugal and Turkey award teachers additional compensation for outstanding performance, but not school heads. The opposite is observed in Colombia and Spain, where school heads are rewarded for high performance, but teachers are not. In Spain, this allowance is fixed at the end of their term of office after a positive performance evaluation and can be kept for the rest of their working life. In France, part of the school-head allowance is awarded according to the results of a professional interview and is paid every three years (Tables D3.8 and D3.9, available on line).

Teachers and school heads are also likely to receive additional payments for working in disadvantaged, remote or high-cost areas in half of the countries and economies with available data, with the exception of Australia, where such incentives are only provided to teachers (Tables D3.8 and D3.9, available on line).

Box D3.3. Actual average salaries of teachers, by age group and gender (2020)

Statutory salaries of teachers increase with the number of years of experience as teachers and this results in an increase in the actual salaries of teachers by age. At primary and secondary levels, actual salaries of older teachers (aged 55-64) are, on average, 35% to 37% higher than those of younger teachers (aged 25-34), but this difference between age groups varies considerably between countries and economies. The difference is less than 20% at all levels of education in Australia, Latvia, Norway and Sweden, while it is 60% or more in Austria, Greece, Israel and Portugal (OECD.stat).

Despite the higher teachers’ salaries for older age groups, the comparison of teachers’ salaries with the earnings of tertiary-educated workers seems to show that teachers’ salaries may evolve at a slower rate than the earnings of other tertiary-educated workers and that the teaching profession is less attractive as the workforce ages. On average across OECD countries and economies, teachers’ actual salaries relative to the earnings of tertiary‑educated workers are about 9 to 10 percentage points higher among the youngest adults (aged 25-34) than among the older age groups (aged 55-64) at the primary and lower secondary levels. However, there are large differences between countries. In Chile, Greece, Hungary and Israel, teachers’ actual salaries relative to the earnings of tertiary-educated workers are higher for older age groups at pre-primary, primary and secondary levels. These are also countries where actual salaries of teachers increase the most with age among OECD countries.

Note: Data refer to ratio of average actual salary (including bonuses and allowances) of teachers in public institutions, relative to the earnings of full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education.

1. Year of reference is 2019 for teachers' salaries.

2. Year of reference is 2018 for teachers' salaries.

Countries and economies are ranked in descending order of relative actual salaries of women teachers.

Source: OECD (2021), Table D3.5, available on line. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

In public educational institutions, the differences between actual salaries for male and female teachers are small. On average across OECD countries, actual salaries of female teachers are less than 2% lower than those of male teachers at primary and secondary levels. However, there are differences across countries and levels of education that may result from differences in the distribution of teachers by qualification level or experience. For example, at the lower secondary level, actual salaries of female teachers are 4% lower than those of male teachers in France, but 4% higher in Israel.

There are larger gender differences in the ratio of teachers’ actual salaries to the earnings of tertiary-educated workers aged 25‑64. On average across OECD countries and economies, actual salaries of male teachers (aged 25-64) are 76% to 85% (at primary and lower secondary levels) of the earnings of a tertiary-educated 25‑64 year-old full-time, full-year male worker. Teachers’ actual salaries relative to the earnings of tertiary-educated workers are between 22 and 24 percentage points higher among women than among men at these levels. The gender difference also varies greatly between countries. At the lower secondary level, relative salaries of female teachers are 2 percentage points higher than those of male teachers in Costa Rica, but the difference exceeds 30 percentage points in Chile, Ireland, Israel, Latvia and Portugal (Figure D3.6).

This higher ratio among female teachers shows that the teaching profession may be more attractive to women than to men, compared to other professions, but it also reflects the persistent gender gap in earnings (in favour of men) in the labour market (Table D3.5, available on line).

Definitions

Teachers refer to professional personnel directly involved in teaching students. The classification includes classroom teachers, special education teachers and other teachers who work with a whole class of students in a classroom, in small groups in a resource room, or in one-to-one teaching situations inside or outside a regular class.

School head refers to any person whose primary or major function is heading a school or a group of schools, alone or within an administrative body such as a board or council. The school head is the primary leader responsible for the leadership, management and administration of a school.

Actual salaries for teachers/school heads aged 25-64 refer to the annual average earnings received by full-time teachers/school heads aged 25-64, before taxes. It is the gross salary from the employee’s point of view, since it includes the part of social security contributions and pension-scheme contributions that are paid by the employees (even if deducted automatically from the employees’ gross salary by the employer). However, the employers’ premium for social security and pension is excluded. Actual salaries also include work-related payments, such as school-head allowance, annual bonuses, results-related bonuses, extra pay for holidays and sick-leave pay. Income from other sources, such as government social transfers, investment income and any other income that is not directly related to their profession are not included.

Earnings for workers with tertiary education are average earnings for full-time, full-year workers aged 25-64 with an education at ISCED level 5, 6, 7 or 8.

Salary at the top of the scale refers to the maximum scheduled annual salary (top of the salary range) for a full‑time classroom teacher (for a given level of qualification of teachers recognised by the compensation system).

Salary after 15 years of experience refers to the scheduled annual salary of a full-time classroom teacher. Statutory salaries may refer to the salaries of teachers with a given level of qualification recognised by the compensation system (the minimum training necessary to be fully qualified, the most prevalent qualifications or the maximum qualification), plus 15 years of experience.

Starting salary refers to the average scheduled gross salary per year for a full-time classroom teacher with a given level of qualification recognised by the compensation system (the minimum training necessary to be fully qualified or the most prevalent qualifications) at the beginning of the teaching career.

Statutory salaries refer to scheduled salaries according to official pay scales. The salaries reported are gross (total sum paid by the employer) less the employer’s contribution to social security and pension, according to existing salary scales. Salaries are “before tax” (i.e. before deductions for income tax).

Methodology

Data on teachers’ salaries at lower and upper secondary level refer only to general programmes.

Salaries were converted using purchasing power parities (PPPs) for private consumption from the OECD National Accounts Statistics database. The period of reference for teachers’ salaries is from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019. The reference date for PPPs is 2018/19, except for some southern hemisphere countries (e.g. Australia and New Zealand), where the academic year runs from January to December. In these countries, the reference year is the calendar year (i.e. 2019). Tables with salaries in national currency are included in Annex 2. To calculate changes in teachers’ salaries (Tables D3.14 and D3.15, available on line), the deflator for private consumption is used to convert salaries to 2005 prices.

In most countries, the criteria to determine the most prevalent qualifications of teachers are based on a principle of relative majority (i.e. the level of qualifications of the largest proportion of teachers).

In Table D3.2, the ratios of salaries to earnings for full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education aged 25‑64 are calculated based on weighted averages of earnings of tertiary-educated workers (Columns 2 to 5 for teachers and Columns 10 to 13 for school heads). The weights, collected for every country individually, are based on the percentage of teachers or school heads by ISCED level of tertiary attainment (see Tables X2.9 and X2.10 in Annex 2). The ratios have been calculated for countries for which these data are available. When data on earnings of workers referred to a different reference year than the 2019 reference year used for salaries of teachers or school heads, a deflator has been used to adjust earnings data to 2019. For all other ratios in Table D3.2 and those in Table D3.8 (available on line), information on all tertiary-educated workers was used instead of weighted averages. Data on the earnings of workers take account of earnings from work for all individuals during the reference period, including salaries of teachers. In most countries, the population of teachers is large and may impact on the average earnings of workers. The same procedure was used in Table D3.7 (available on line), but the ratios are calculated using the statutory salaries of teachers with 15 years of experience instead of their actual salaries.

For more information, please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018 (OECD, 2018[5]) and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Source

Data on salaries and bonuses for teachers and school heads are derived from the 2019 joint OECD/Eurydice data collection on salaries of teachers and school heads. Data refer to the 2018/19 school year and are reported in accordance with formal policies for public institutions. Data on earnings of workers are based on the regular data collection by the OECD Labour Market and Social Outcomes of Learning Network.

References

[3] Johnes, G. and J. Johnes (2004), International Handbook on the Economics of Education, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA.

[4] Matteazzi, E., A. Pailhé and A. Solaz (2018), “Part-time employment, the gender wage gap and the role of wage-setting institutions: Evidence from 11 European countries”, European Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 24/3, pp. 221-241, http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0959680117738857.

[2] OECD (2019), Education at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f8d7880d-en.

[5] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[1] OECD (2005), Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers, Education and Training Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264018044-en.

Indicator D3 tables

Tables Indicator D3. How much are teachers and school heads paid?

|

Table D3.1 |

Teachers’ statutory salaries based on the most prevalent qualifications at different points in teachers’ careers (2020) |

|

Table D3.2 |

Teachers' and school heads' actual salaries relative to earnings of tertiary-educated workers (2020) |

|

Table D3.3 |

Teachers' and school heads' average actual salaries (2020) |

|

Table D3.4 |

School heads' minimum and maximum statutory salaries, based on minimum qualifications (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.5 |

Teachers' actual salaries relative to earnings of tertiary-educated workers, by age group and gender (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.6 |

Trends in teachers’ statutory salaries, based on the most prevalent qualifications after 15 years of experience (2000 and 2005 to 2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.7 |

Trends in average teachers’ actual salaries (2000, 2005 and 2010 to 2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.8 |

Criteria used for base salaries and additional payments awarded to teachers in public institutions, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.9 |

Criteria used for base salaries and additional payments awarded to school heads in public institutions, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.10 |

Decision-making level for criteria used for determining teachers’ base salaries and additional payments, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.11 |

Decision-making level for criteria used for determining school heads’ base salaries and additional payments, by level of education (2020) |

|

WEB Table D3.12 |

Structure of compensation system for school heads (2020) |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 July 2021. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table D3.1. Teachers' statutory salaries, based on the most prevalent qualifications at different points in teachers' careers (2020)

Annual teachers' salaries, in public institutions, in equivalent USD converted using PPPs for private consumption

Note: The definition of teachers' most prevalent qualifications is based on a broad concept, including the typical ISCED level of attainment and other criteria. The most prevalent qualification is defined for each of the four career stages included in this table. In many cases, the minimum qualification is the same as the most prevalent qualification, see Table X3.D3.2 in Annex 3. Please see Annex 2 and Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Year of reference 2019.

2. Data on pre-primary teachers include the salaries of kindergarten teachers who are the majority.

3. Includes the average of fixed bonuses for overtime hours for lower and upper secondary teachers.

4. At the upper secondary level includes teachers working in vocational programmes (in Slovenia and Sweden, includes only those teachers teaching general subjects within vocational programmes).

5. Excludes the social security contributions and pension-scheme contributions paid by the employees.

6. Actual base salaries.

7. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D3.2. Teachers' and school heads' actual salaries relative to earnings of tertiary-educated workers (2020)

Ratio of salary, using annual average salaries (including bonuses and allowances) of full-time teachers and school heads in public institutions relative to the earnings of workers with similar educational attainment (weighted average) and to the earnings of full-time, full-year workers with tertiary education

Note: Where the year of reference for the earnings of tertiary-educated workers and the salaries of teachers differ the earnings of tertiary-educated workers have been adjusted to the reference year used for salaries of teachers using deflators for private final consumption expenditure. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Year of reference 2019 for salaries of teachers and school heads.

2. Year of reference 2018 for salaries of teachers and school heads.

3. At pre-primary and primary levels actual salaries refer to all teachers/school heads in those levels of education combined including special needs education. At lower and upper secondary levels, actual salaries refer to all teachers/school heads in those levels of education combined, including vocational and special needs education.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D3.3. Teachers' and school heads' average actual salaries (2020)

Annual average salaries (including bonuses and allowances) of teachers and school heads in public institutions, in equivalent USD converted using PPPs for private consumption

Note: Where the year of reference for the earnings of tertiary-educated workers and the salaries of teacher differ, the earnings of tertiary-educated workers have been adjusted using deflators for private final consumption expenditure. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Includes teachers working in vocational programmes at the upper secondary level (in Sweden, includes only those teachers teaching general subjects within vocational programmes).

2. Year of reference 2019.

3. Includes data on the majority, i.e. kindergarten teachers only for pre-primary education.

4. Year of reference 2018.

5. At pre-primary and primary levels actual salaries refer to all teachers/school heads in those levels of education combined, including special needs education. At lower and upper secondary levels, actual salaries refer to all teachers/school heads in those levels of education combined, including vocational and special needs education.

6. Includes unqualified teachers.

7. Includes salaries of school heads and teachers.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table D3.4. School heads' minimum and maximum statutory salaries, based on minimum qualifications (2020)

Annual school heads' salaries, in public institutions, in equivalent USD converted using PPPs for private consumption (by level of education)

Note: The definition of school heads' minimum qualifications is based on a broad concept, including the typical ISCED level of attainment and other criteria. See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Year of reference 2019.

2. Includes data on the majority, i.e. kindergarten school heads only for pre-primary education.

3. For 2018/19, the methodology was revised, The new data apply to school heads (ISCED 02 and 1) in charge of schools with ten classes or more, i.e with teaching responsibilities accounting for 50% or less of their working time, in line with the international guidelines.

4. Actual base salaries.

5. Minimum salary refers to the most prevalent qualification (master’s degree or equivalent) and maximum salary refers to the highest qualification (education specialist or doctoral degree or equivalent).

6. Excludes countries for which either the starting salary (with minimum qualifications) or the salary at top of scale (with maximum qualifications) is not available. It refers to the average value for the ratio, and is then different from the ratio of the average maximum salary to the average minimum salary.

Source: OECD (2021). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2021_Annex3_ChapterD.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader's Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.