This chapter first describes the equity market landscape in Brazil and selected countries. It provides an overview of the main trends in the use of equity markets with respect to both initial public offerings (IPOs) and secondary public offerings (SPOs) as well as delistings from the stock market. It also presents the ownership structure of listed companies in Brazil. The chapter then presents the corporate bond market landscape including green bonds in Brazil and in selected countries. The chapter ends with a summary of existing GHG emission markets.

Sustainability Policies and Practices for Corporate Governance in Brazil

2. Capital market trends and the investor landscape

Abstract

Due to its long-term nature, equity financing contributes to innovation and long-term business dynamics, which are prerequisites for sustainable economic growth. Importantly, access to equity capital gives corporations the financial resilience that helps them overcome temporary downturns while still meeting their obligations to employees, creditors and suppliers. Additionally, the scrutiny by equity markets serves the critical function of redeploying capital from companies that have limited prospects for surviving to become long-term viable businesses. From the perspective of ordinary households, public equity markets provide an opportunity to directly or indirectly participate in corporate value creation and additional options for managing savings and plan for retirement.

The Brazilian public equity market

In 2007, the Bovespa Holding SA and the Brazilian Mercantile & Futures Exchange (BMF SA) merged and created the BM&FBOVESPA. In 2017, BM&FBOVESPA merged with CETIP and created the B3 – Brasil, Bolsa, Balcão. B3 provides trading services for securities listed on exchanges and trading on over the counter (OTC) markets. B3’s scope of activities include the creation and management of trading systems, clearing, settlement, deposit and registration for the main classes of securities, from equities and corporate fixed income securities to currency and interest rate derivatives, securitisation products and agricultural commodities. B3 also acts as a central counterparty for most of the trades carried out in its markets and offers central depository and registration services. As a public company, shares issued by B3 are traded on its own stock exchange.

Currently, there are four listing segments in the B3 with different requirements designed to serve distinct company profiles, namely Novo Mercado, Level 1, Level 2 and Basic segments. In terms of corporate governance, Novo Mercado requires differentiated standards compared to the other listing segments such as the adoption of a set of corporate rules aimed at increasing minority shareholders’ rights, as well as enhancing the disclosure of policies and the existence of monitoring and control structures. Among all segments of the B3, only Novo Mercado requires that companies establish an audit committee and disclose the following policies: (i) Compensation Policy; (ii) Nomination Policy of the Board of Directors, Advisory Committees and Executive Management Board; (iii) Risk Management Policy; (iv) Related Party Transaction Policy; and (v) Securities Trading Policy, with minimum requirements (except for the Compensation Policy).

Table 2.1. Requirements of the market segments in the B3

|

Novo Mercado |

Level 1 |

Level 2 |

Basic |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Share Capital |

Only common shares |

Common and preferred shares (as per legislation) |

Common and preferred shares (with additional rights) |

Common and preferred shares (as per legislation) |

|

Minimum percentage of outstanding share that can be traded by the general public (free float) |

25% or 15% if the average daily trading volume is above BRL 25 million |

25% |

25% |

There is no specific regulation |

|

Composition of the Board of Directors |

Minimum of 3 members, of which at least 2 or 20% (whichever is greater) must be independent with unified term of up to 2 years |

Minimum of 3 members, with unified term of up to 2 years |

Minimum of 5 members, of which at least 20% must be independent with unified term of up to 2 years |

Minimum of 3 members (pursuant to Brazilian Corporations Law) |

|

Board of Directors’ duties |

Statement on any public tender offer for the acquisition of shares issued by the company |

There is no specific regulation |

Statement on any public tender offer for the acquisition of shares issued by the company |

There is no specific regulation |

|

Audit Committee |

Mandatory setting up of an audit committee or statutory audit committee |

Optional |

Optional |

Optional |

|

Financial Statements |

As per legislation in force |

As per legislation in force |

Translated into English |

As per legislation in force |

|

Disclosure in English simultaneously with the disclosure in Portuguese |

Material information and results press releases |

There is no specific regulation |

There is no specific regulation besides the financial statements |

There is no specific regulation |

|

Annual public shareholder meeting |

Public meeting (in-person or by any other means that allow remote participation) must be hold until 5 business days after the disclosure of the quarterly and annual financial statements about the information disclosed |

Mandatory (in-person) |

Mandatory (in-person) |

Optional |

Source: B3 (2017[1]), Comparative list of segments, www.b3.com.br.

For the segments Level 1 and Level 2, companies are required to adopt specific practices. Level 1 companies largely try to improve methods of disclosure to the market participants and to increase the number of shareholders in their ownership structure. Level 2, in addition to the obligations of Level 1, requires that companies and its controlling shareholders must adopt and observe a much broader range of corporate governance practices and increase protection to minority shareholder rights (B3, 2022[2]). B3 also has the Basic segment that does not require additional corporate governance requirements beyond what is mandated by regulation.

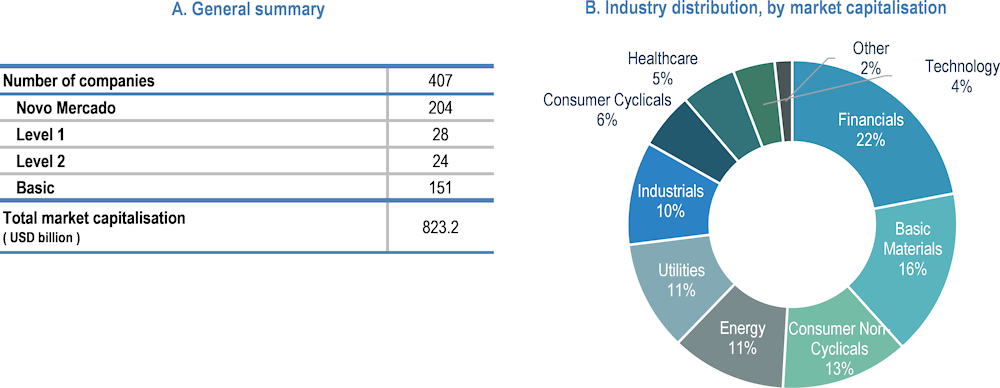

As of 2021, there were 407 listed companies in the Brazilian public equity market with a total market capitalisation of USD 823.2 billion (Figure 2.1). Almost half of the companies are listed on Novo Mercado, and Level 1 and Level 2 companies together only represent 13% of the total number companies. With respect to the industry distribution of listed companies, financials, basic materials and consumer non-cyclicals are the top three industries accounting, respectively, for 22%, 16% and 13% of the total market capitalisation.

Figure 2.1. Summary statistics of the listed companies on B3 as of 2021

Note: Excluding investment funds and REITs.

Source: B3, Refinitiv.

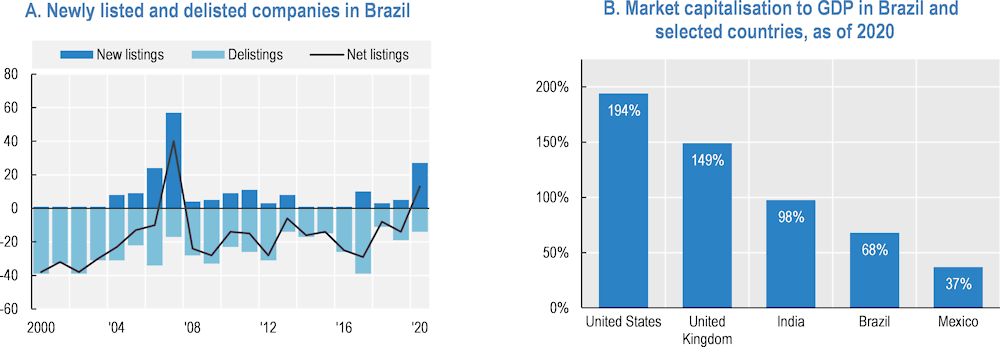

Between 2000 and 2020, 190 new listings and 542 delistings have taken place in the Brazilian public equity market (Figure 2.2, Panel A). Net listings were only positive in 2007 and in 2020 when the Brazilian equity market saw a surge in listings. Total market capitalisation to GDP in Brazil was 68% as of end 2020, which is only higher than the one in Mexico among selected jurisdictions in Figure 2.2, Panel B. In the United States and in the United Kingdom, market capitalisation surpasses GDP. India, as many other Asian emerging markets, has experienced an increase in the use of public equity markets during the last two decades (OECD, 2022[3]).

Figure 2.2. Summary statistics of public equity market in Brazil

Note: In Panel A, investment funds and REITs are excluded. Market capitalisation in Panel B covers the domestic listed companies.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, Refinitiv, World Bank, World Federation of Exchanges.

Trends in initial public offerings

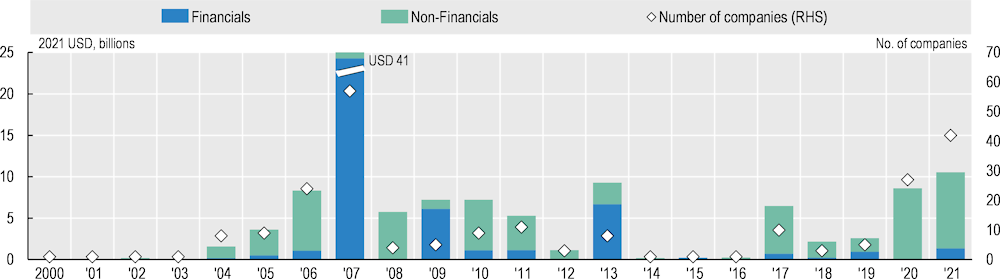

The Brazilian equity market has shown strong activity in initial public offerings (IPOs) in some periods since 2000. The annual number of companies joining the Brazilian public market together with the total amount of equity capital they raised is presented in Figure 2.3. IPO activity in Brazil reached its highest level in 2007, with a total of 57 companies raising almost USD 41 billion. Since 2008, the amount of equity raised decreased and has been on average USD 5 billion per year. However, the distribution of IPOs over time has been uneven and there was almost no activity in the market between 2014 and 2016. During the COVID‑19 pandemic there has been a significant increase both in the number of IPOs and the amount of equity raised. Total proceeds raised in 2020 and 2021 via IPOs was approximately two and three times of the previous three‑year average amount, respectively. In 2020 and 2021, a total of 69 companies raised equity capital through IPOs with a total amount of USD 19 billion.

Figure 2.3. Initial public offerings (IPOs) by companies in Brazil

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, see Annex for details.

Overall, the use of public equity markets by non-financial companies in Brazil has been lower compared to global levels. Between 2000 and 2021, the share of non-financial company IPO proceeds in Brazil was 63% of the total proceeds – including both financial and non-financial companies – while this number was 78% at the global level. Financial companies in Brazil raised the highest amount of equity in 2007 with USD 24 billion, which represents more than half of the proceeds raised between 2000 and 2021.

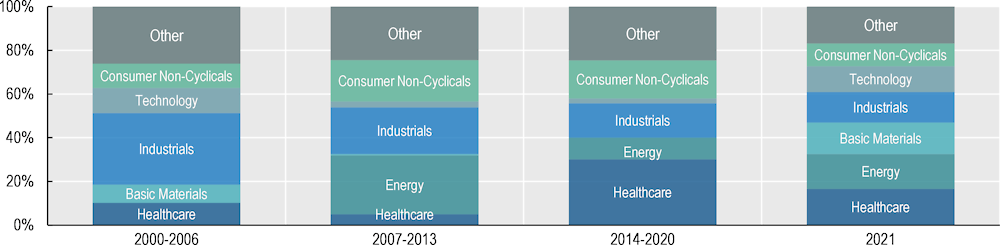

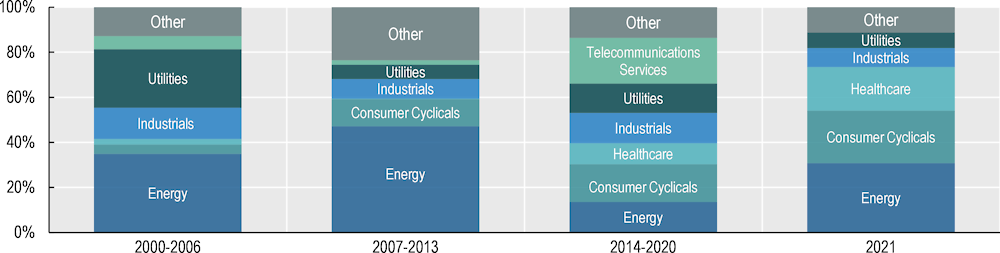

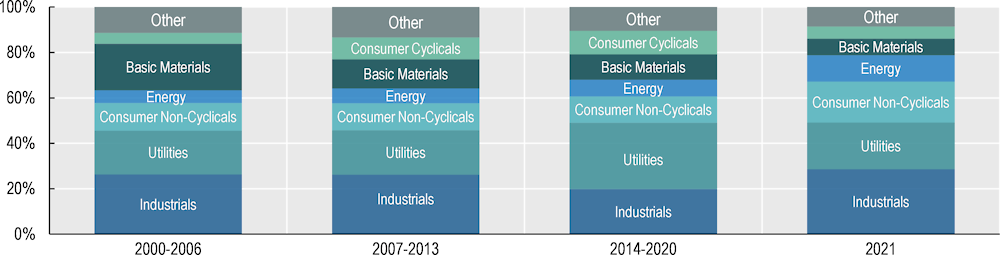

Companies in the industrials, energy and consumer-non-cyclicals industries dominated the non-financial company IPOs in Brazil between 2000 and 2021 with shares of 21%, 17% and 16% respectively (Figure 2.4). In each seven years’ period in the figure below, at least 30% of all proceeds were raised by industrial companies in the first period (2000‑06); by energy companies in the second period (2007‑13); and by health care companies in the last period (2014‑20). The high share of energy IPOs in the second period was driven by three Brazilian companies that raised almost 85% of the total energy IPO proceeds during that period. In 2021 IPOs were more evenly distributed across six industries. Overall, it is worth noting that during the periods provided in the figure below, only 5% of all equity capital raised through IPOs by non-financial companies in Brazil went to the technology industry.

Figure 2.4. Industry distribution of non-financial IPOs in Brazil, by total proceeds

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, see Annex for details.

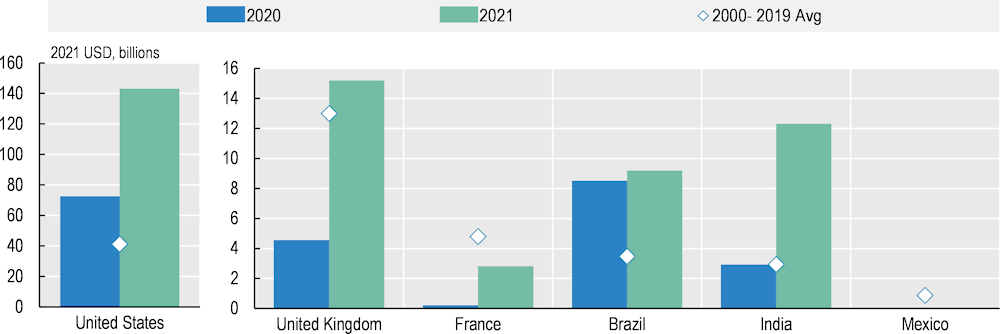

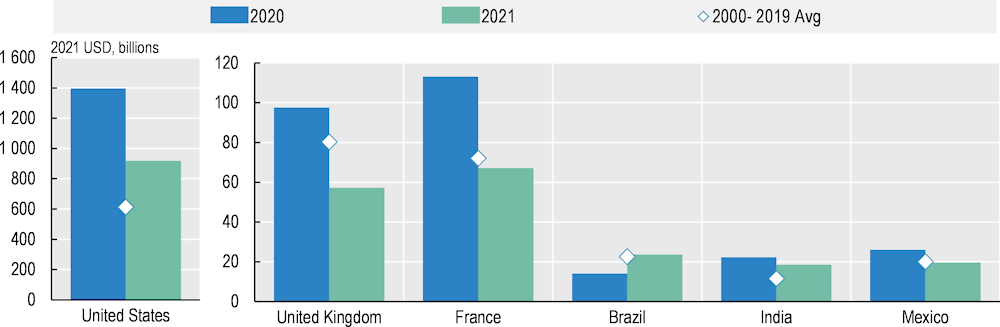

Non-financial companies from the United States represent the highest share of total global IPO proceeds between 2000 and 2021. On average, almost 30% of all global IPO proceeds over that period was raised by US non-financial companies. Importantly, this share increased to 36% in 2020 and 2021. The average yearly IPO proceeds by non-financial company IPOs in the United States was USD 41 billion between 2000 and 2019 (Figure 2.5). Annual proceeds increased during the COVID‑19 crisis, and they were significantly higher than the historical average, reaching USD 73 billion and USD 143 billion in 2020 and 2021, respectively. In the United Kingdom and France, IPO proceeds, after decreasing significantly in 2020, saw an increase in 2021. In the United Kingdom, proceeds in 2021 were 20% higher than the historical average, while in France proceeds were only around 60% of its historical average.

Total IPO proceeds in the Brazilian public equity market between 2000 and 2021 was USD 76.8 billion, which was higher than the amount in other emerging markets such as India and Mexico (USD 74 billion and USD 17.5 billion, respectively). Average yearly historical IPO proceeds in Brazil, India and Mexico between 2000 and 2019 was USD 3.5 billion, USD 2.9 billion and USD 0.9 billion, respectively. In 2020, IPO proceeds in Brazil were significantly higher than its historical average. In 2021, non‑financial companies raised a total of USD 8.5 billion in Brazil, and USD 12.3 billion in India, while there was no IPO by non-financial companies in Mexico.

Figure 2.5. IPOs by non-financial companies in Brazil and selected countries

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, see Annex for details.

Trends in secondary public offerings

Companies that are already listed on a stock exchange can raise additional equity on the primary public equity markets through secondary public offerings (“SPOs” or follow-on offerings). The proceeds from the SPOs may be used for a variety of purposes and can also help sound companies bridge a temporary downturn in economic activity. In this respect, SPOs played an important role in providing the corporate sector with capital in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and through the 2020 during the COVID‑19 crisis.

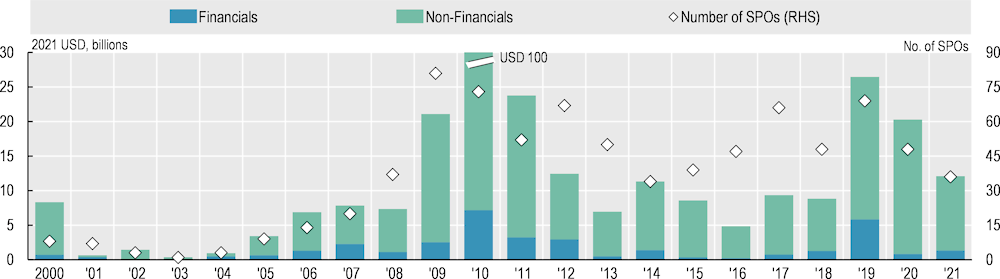

Since 2000, companies in Brazil have raised 2.5 times as much money through SPOs as they have raised through IPOs. In the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, a record number of Brazilian listed companies in 2010 turned to the public equity market to raise a total of USD 100 billion through secondary offerings. Following the COVID‑19 crisis, already listed companies in Brazil used public equity markets to a lesser extent when compared to the period following the 2008 global financial crisis. Globally, SPOs by financial companies represented an important share – almost one‑third- between 2000 and 2021 – of all the total SPO proceeds. In Brazil, SPOs by financial companies only represented 12% of all SPOs between 2000 and 2021 (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Secondary public offerings (SPOs) by companies in Brazil

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, see Annex for details.

Brazilian companies in the energy, consumer cyclicals and industrials industries were the top three industries by amount of capital raised in SPOs between 2000 and 2021 with corresponding shares of 35.7%, 13.4% and 10.4% respectively (Figure 2.7). Over the entire period, most of the energy industry SPOs took place in 2010, representing 75% of the total proceeds in 2010. During the first three periods presented in Figure 2.7the figure, health care and consumer cyclicals companies used comparatively fewer SPOs to raise capital, while in 2021 SPOs of consumer cyclicals and health care companies represented together 43% of all proceeds.

Figure 2.7. Industry distribution of SPOs in Brazil, by total proceeds

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, B3, see Annex for details.

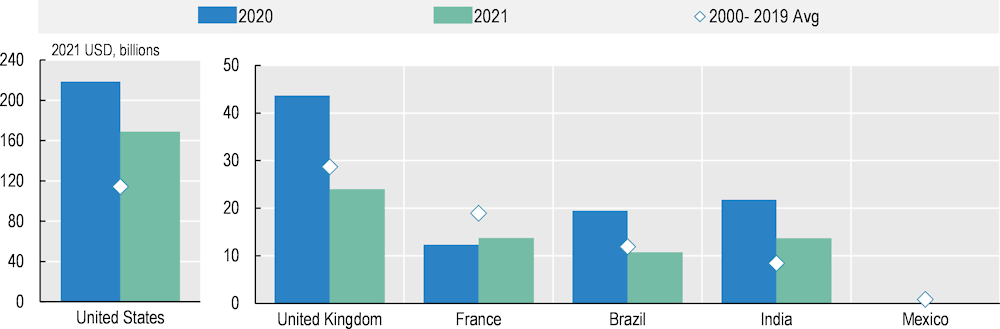

As it is the case for IPOs, non-financial companies from the United States represented the highest share of total global SPO proceeds between 2000 and 2021. On average, around 30% of all the SPO proceeds between 2000 and 2021 was raised in the United States by non-financial companies. Between 2000 and 2019, the average yearly SPO proceeds of non-financial companies in Unites States was USD 114 billion and proceeds increased significantly following the COVID‑19 pandemic (Figure 2.8). In 2020 and 2021, annual proceeds were significantly higher than their historical average between 2000 and 2019, reaching USD 219 billion and USD 169 billion respectively. In 2020 and 2021, non-financial listed companies raised less capital via SPOs in France compared to of the historical average between 2000 and 2019. In 2020, proceeds in the United Kingdom were 50% higher than its historical average. In 2021, use of SPOs in the UK by non-financial companies was slightly lower than its historical average.

Total SPO proceeds in the Brazilian public equity market between 2000 and 2021 was USD 268.5 billion, which was higher than the total in the Indian and Mexican markets (USD 203.8 billion and USD 17 billion, respectively). SPO proceeds in Brazil, India and Mexico by non-financial companies between 2000 and 2019 were on average USD 11.9 billion, USD 8.4 billion, and USD 0.9 billion, respectively. In 2020, SPO proceeds in Brazil were significantly higher than their historical average. In 2021, non-financial companies raised a total of USD 10.8 billion in Brazil, USD 14 billion in India, while use of SPOs by non-financial companies in Mexico was almost negligible.

Figure 2.8. SPOs by non-financial companies in Brazil and selected countries

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, see Annex for details.

Investors and ownership structure in the Brazilian public equity market

To provide a complete picture of the Brazilian public equity market, it is important to understand the investor landscape and the ownership structure at the company level. Globally, ownership structures of the world’s listed companies have experienced significant changes over the past two decades. One of the most important developments globally is the increase in institutional ownership (OECD, 2021[4]). However, there are important country and regional differences with respect to the different categories of investors that make up the largest shareholders at the company level.

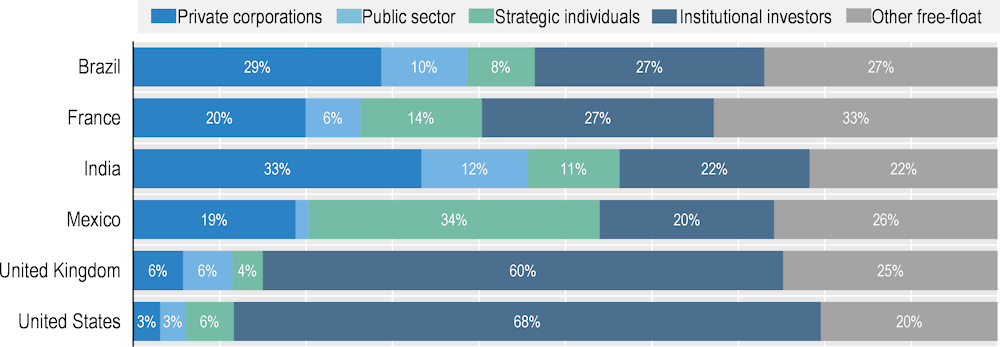

Figure 2.9 shows the ownership distribution among different categories of owners in Brazil and selected countries, using the categories in (De La Cruz, Medina and Tang, 2019[5]), is provided in Figure 2.9. In both the United States and the United Kingdom, institutional owners are, by far, the largest category of owners holding 68% and 60% of the total capital, respectively. In France, institutional investors also rank first among different categories of investors with a comparatively lower share of the market capitalisation (27%). In Brazil and India, private corporations are the largest investor category, holding, respectively, 29% and 33% of total market capitalisation. Differently, strategic individuals rank first in Mexico as owners holding 34% of the listed equity, while in Brazil strategic individuals is the lowest among all categories holding only 8% of the listed equity. Among countries included in the figure below, public sector ownership, including the central and local governments and public pension funds, is the highest in India, representing the 12% of total market capitalisation, and followed by Brazil, representing a share of 10%.

Figure 2.9. Investor holdings at country level as of end‑2020

Note: Other free‑float refers to the holdings by shareholders that do not reach the threshold for mandatory disclosure of their ownership records or retail investors that are not required to do so.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

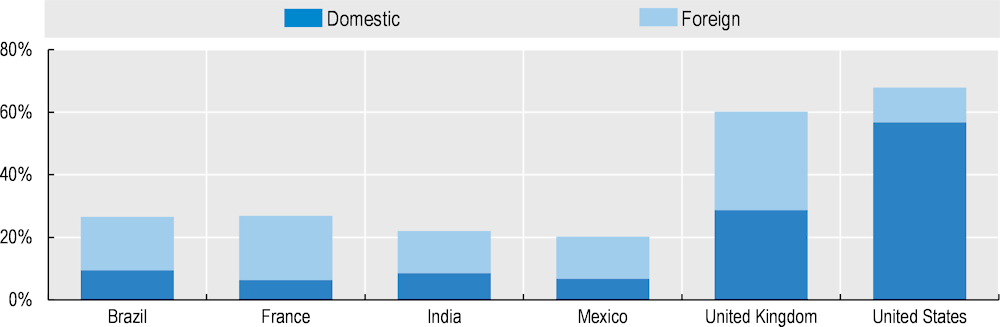

Institutional investors can include a significant share of foreign ownership having further implications for the functioning of capital markets. The relative importance of domestic and foreign institutional investors in Brazil and selected countries is provided in Figure 2.10. While domestic institutional investors account for about 83% of all institutional investors’ holdings in the United States, domestic institutional investors only account for 48% in the United Kingdom. In the US market, while domestic investors are dominant equity holders, in terms of total amount held foreign ownership is higher compared to all other markets. This is partly explained by the fact that the United States hosts many of the world’s largest asset managers that also manage funds for non-US investors (De La Cruz, Medina and Tang, 2021[6]). France has the highest share of foreign institutional investors (77%). Similarly, in Mexico, Brazil and India, the institutional investor landscape is dominated by foreign investors who hold 67%, 65% and 61% of all institutional investors, respectively.

Figure 2.10. Domestic and foreign institutional ownership in Brazil and selected countries, as of end 2020

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Refinitiv, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

Increasing ownership concentration has been documented by the OECD work as a common phenomenon across markets. However, there are important differences with respect to the categories of owners that make up the largest owners and how this could affect the design of corporate governance regulations. The degree of concentration and control by individual shareholders at the company level is notably relevant for the regulation of related party transactions, takeovers and other matters related to the relationship between controlling and non‑controlling shareholders (OECD, 2021[4]). Table 2.2 shows the average combined holdings of the largest shareholders in the listed corporate sector in Brazil and selected countries.

In Brazil ownership concentration is also a common characteristic in listed companies. The average combined holdings of the top three investors is 56.7%, close to the levels in France, India and Mexico. This high concentration is mainly the result of significant ownership by private corporations as the top three private corporations own on average 23% of the equity in each company in Brazil. This may be seen as an indication of strong presence of company group structures. The top three strategic individual investors and institutional investors have an average combined holding of 15% and 11% respectively.

Table 2.2. Ownership concentration at company level in Brazil and selected countries, as of end 2020

|

|

Largest 1 |

Largest 3 |

Largest 5 |

Largest 20 |

Largest 50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brazil |

40.6% |

56.7% |

62.2% |

71.3% |

73.2% |

|

France |

42.3% |

55.9% |

60.7% |

68.7% |

71.0% |

|

India |

37.6% |

54.0% |

60.9% |

72.6% |

73.9% |

|

Mexico |

44.9% |

56.6% |

60.8% |

67.0% |

68.4% |

|

United Kingdom |

19.7% |

36.3% |

45.1% |

64.6% |

69.8% |

|

United States |

18.5% |

33.0% |

41.1% |

60.5% |

68.9% |

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Factset, Refinitv, Bloomberg, see Annex for details.

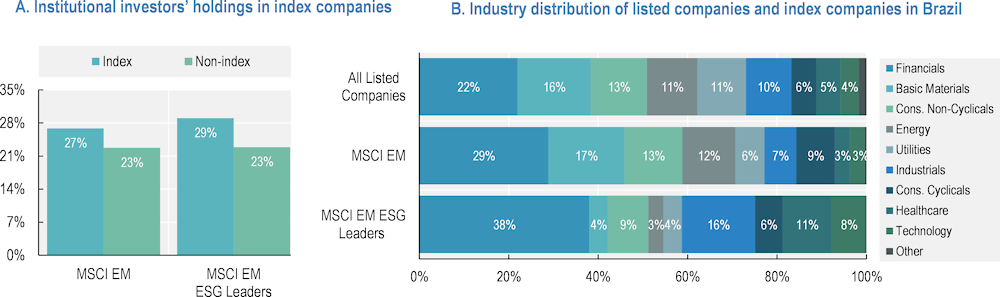

One important long-term trend in the public equity markets globally has been the growing use of index investment strategies by institutional investors. This trend has resulted in a significant difference with respect to institutional ownership between companies included in major indices and those that are not. In addition, because most indices weight companies according to their market capitalisation and free‑float levels, being a large corporation with higher free‑float, all else equal, will result in a higher weighting in the index. Against this background, companies included in the MSCI indices found to have a higher average institutional ownership than non-index companies. For instance, companies that are included in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index have on average 16% institutional holdings compared to 7% for companies that are not included (OECD, 2021[7]).

This trend also holds for the Brazilian companies that are included in the MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI Emerging Markets ESG Leaders1 indices. As of September 2021, there were, respectively, 49 and 26 Brazilian companies with total market capitalisation of USD 740 billion and USD 322 billion. Brazilian companies in MSCI EM index have on average 27% institutional holdings compared to 23% for Brazilian companies that are not included in the index (Figure 2.11, Panel A). Brazilian companies in MSCI EM ESG Leaders index have on average 29% institutional holdings compared to 23% for Brazilian companies that are not included in the index. Of special relevance, Brazilian companies correspond to a share of 4.6% of the MSCI EM index, but only to a share of 2.8% of the MSCI EM ESG Leaders index.

Comparison of industry distribution between all Brazilian listed companies and index included Brazilian companies reveal that companies from financials and industrials industries correspond more than 50% of the market capitalisation of the companies included in the MSCI EM ESG Leaders index. Financials, basic materials and consumer non-cyclicals together dominate the listed company and MSCI EM index company universe for Brazil (Figure 2.11, Panel B).

Figure 2.11. Institutional investors’ holdings in index companies versus non-index companies in Brazil (as of end‑2020)

Note: Listed companies in Brazil do not include investment funds and REITs. The information on MSCI constituents is as of end 2020.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series dataset, FactSet, Refinitiv, Bloomberg, B3, MSCI Constituents Information.

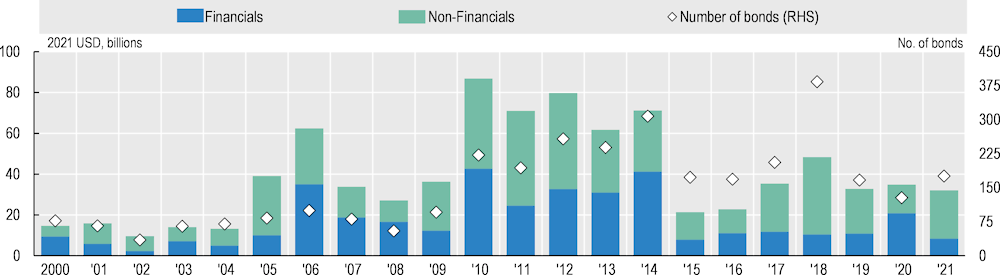

Trends in corporate bond issuances

Compared to ordinary bank loans, corporate bonds typically have longer maturities. In addition, the absence or relatively limited requirements for collateral gives corporate bond financing a special role as a source of financing compared to other types of borrowing. In the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, there has been a significant and lasting increase in corporate bond issuances worldwide. Annual corporate bond issuances by non-financial companies doubled from an average of USD 932 billion between 2000 and 2007 to an average of almost USD 2 trillion between 2008 and 2021.2 Corporate bonds have also become an increasingly important source of finance for Brazilian companies. The annual number of Brazilian companies that raised funds via corporate bonds between 2000 and 2021 together with the total amount of capital raised are presented in Figure 2.12. Overall, between 2000 and 2021, Brazilian companies raised a total of USD 864 billion in bonds, with 60% of this amount raised by non-financial companies. Corporate bond issuances reached its highest level in 2010, with a total of 168 Brazilian companies raising USD 87 billion. The activity was relatively high between 2010 and 2014, when the annual average issuances were USD 74 billion. Since 2015, annual issuances saw a decline, averaging only USD 33 billion.

Figure 2.12. Corporate bond issuances by Brazilian companies

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Refinitiv, see Annex for details.

Industrials, utilities and basic materials were the top three industries by the amount of capital raised between 2000 and 2021 in Brazil, with a share of 24%, 23% and 14%, respectively (Figure 2.13). Three industries, namely industrials, utilities, and consumer non‑cyclicals, experienced an increase in the amount raised from 58% of the total proceeds raised between 2000 and 2006, to 67% of the total proceeds in 2021.

Figure 2.13. Industry distribution of corporate bonds by Brazilian companies, by total proceeds

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Refinitiv, see Annex for details.

Non-financial companies from the United States are the largest users of corporate bonds globally. Forty-two percent of all corporate bond proceeds between 2000 and 2021 was raised by US non-financial companies. Annual proceeds of US non‑financial companies increased significantly following the start of the COVID‑19 crisis. Indeed, it was significantly higher than its historical average (2000‑19) reaching USD 1.4 trillion and USD 918 billion in 2020 and 2021, respectively (Figure 2.14). In the United Kingdom and France, 2020 proceeds surpassed their historical average. However, in 2021 the total amount raised by UK and French companies decreased. In the United Kingdom, proceeds were 71% of the historical average, while they were slightly lower than its historical average in France.

Over the 2000‑21 period, Brazilian non-financial companies raised more funds via corporate bonds than Indian and Mexican non-financial companies. The total amount of capital raised via corporate bonds by Brazilian, Mexican and Indian non-financial companies was USD 489 billion, USD 444 billion and USD 260 billion respectively. In 2020, corporate bond issuances by Brazilian companies decreased and was lower than the historical average. In 2021, however, total amount raised was in line with the historical average. Indian and Mexican non-financial companies increased their use of corporate bonds in 2020 compared to their historical averages. In 2021, corporate bond issuances by Indian and Mexican companies were still above historical averages.

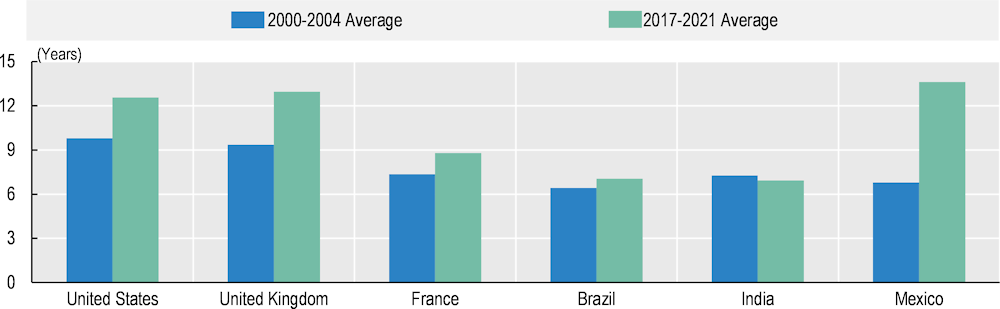

Bonds issued at longer maturities may be particularly helpful for companies in times of financial distress as they help extending the debt obligations of the company. In this respect, the average maturity of corporate bonds at origination indicates, on average, for how long a company with liquidity problems can sustain the pressure of refinancing its debt. Globally, there has been an increase in average maturities of corporate bonds issued by non-financial companies, with the increase being most pronounced for investment grade companies that extended maturities from eight years in 2000 to 13.4 years in 2021. However, across countries and regions, average maturities for corporate bonds issued by non-financial companies vary widely.

Figure 2.14. Bond issuance by non-financial companies from Brazil and selected countries

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Refinitiv, see Annex for details.

Average maturities for corporate bonds by non-financial companies from Brazil and selected countries for the 5‑year periods of 2000‑04 and 2017‑21 are presented in Figure 2.15. Over the periods provided in the figure below, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Mexico have seen substantial increases in average maturities. While the increase in average maturities for Brazilian non-financial corporate bonds were comparatively low, average maturities in India experienced a slight decline. Among the six countries shown in the figure, Brazil had the lowest average maturity for corporate bonds in 2021 (6.6 years) while the United Kingdom had the highest maturity (14 years).

Figure 2.15. Average maturities for corporate bonds by non-financial companies from Brazil and selected countries

Note: Maturity is the average of the original maturity equally weighted proceeds. Over the period 2017‑21, total number of corporate bonds issued by Mexican companies is the lowest by number, however, Mexcio has a higher share of corporate bonds having maturity more than 15 years to total corpoate bonds compared to other countries. This leads to higher average maturity for Mexico during this period.

Source: OECD Capital Market Series Dataset, Refinitiv, see Annex for details.

Green bonds and other ESG bonds

According to one estimate, a USD 6.9 trillion investment between 2015 and 2030 would be needed to meet climate objectives in the infrastructure industry only in line with the Paris Agreement (OECD, 2017[8]). Another estimate related to the energy industry claims that annual clean energy investment worldwide will need to more than triple by 2030 to around USD 4 trillion to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 (IEA, 2021[9]). At the regional level, for example, financing the net-zero GHG emissions target of the EU by 2050 is estimated to cost an annual investment of 2% of GDP (Darvas and Wolff, 2021[10]).

Public resources alone will not be enough to cover the trillions of dollars needed to fulfil the goals of the Paris Agreement, and to adapt infrastructure and industrial systems to climate change. Private financing sources such as institutional investors will also have a key role to play in financing the climate transition. Recently, green bonds have been issued as an alternative financing instruments in relation to the climate change. The criteria for determining whether an activity financed by the issuance of a corporate bond is environmentally sustainable, however, can vary. In order to protect the buyers of corporate bonds and other financial instruments, some jurisdictions have been developing a taxonomy to classify which economic activities could be considered environmentally sustainable (allowing, for instance, a company to name a bond it issues as “green”).3

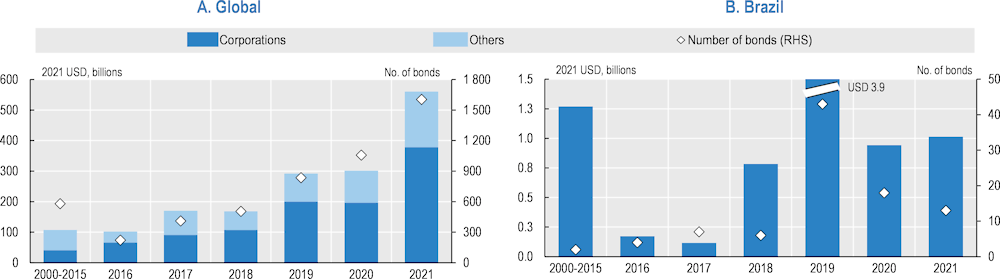

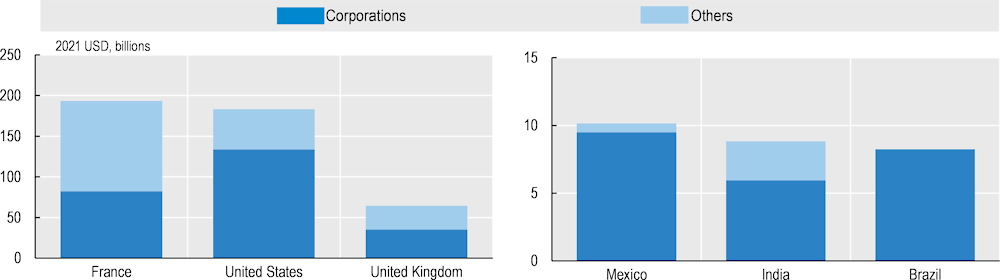

There has been a gradual increase in the amount of funds raised via green bonds, reaching almost USD 560.4 billion in 2021 (Figure 2.16, Panel A), with 67% of this amount (USD 378.1 billion) issued by corporations, and the rest is issued by others, including agencies, governments, central banks, supranational institutions and municipalities. Still these amounts are modest compared to the USD 19.1 trillion of government borrowing by OECD countries (OECD, 2022[11]) as well as the USD 5.8 trillion in corporate bond borrowing for the same year.4

Overall, between 2000 and 2021, there were 35 issuers of green bonds in Brazil, among which 23 are either listed or subsidiaries of listed companies. In 2019, issuances in Brazil saw a surge, when 43 green corporate bonds were issued with total proceeds of USD 3.9 billion (Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16. Green bond issuances, by issuer type and number

Note: Others include agencies, governments, treasuries, central banks, supranational, and non-US municipalities.

Source: Refinitiv, B3, see Annex for details.

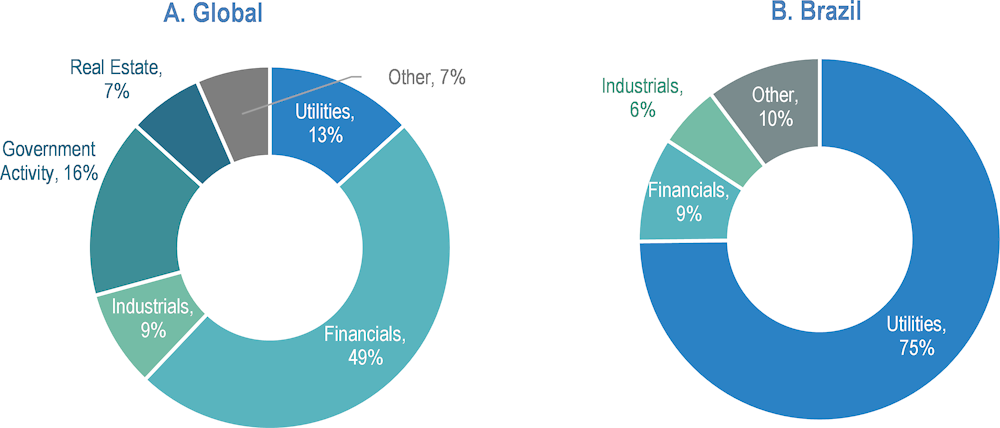

Global industry distribution of green bonds’ issuers reveals that the financial industry accounts for half of the total funds raised between 2000 and 2021 (Figure 2.17, Panel A). Government activity, utilities, and industrials followed financials with shares of 16%, 13% and 9% of the total proceeds. In Brazil, the utilities industry dominates the green bond issuances with 75% of all the green bond issuances (Figure 2.17, Panel B). Different from the global picture, in Brazil the financial industry represents a modest share of green bonds (9%).

Figure 2.17. Industry composition of green bonds between 2000 and 2021

Note: This figure includes information on bonds issued by corporations, agencies, governments, central banks, supranational institutions and municipalities.

Source: Refinitiv, B3, see Annex for details.

As seen in Figure 2.18, issuers domiciled in France and in the United States raised USD 193.4 billion and USD 183.3 of funds, respectively, via green bonds between 2000 and 2021. Corporations in the United States represented a higher share of the total green bonds issued by both corporations and governments when compared to the share of corporations in France. The total amount of funds raised via green bonds by issuers in the United Kingdom was USD 64.4 billion between 2000 and 2021, and 55% of the funds were raised by corporations. Green bond issuances in Mexico, India and Brazil were modest compared to the United States, France and the United Kingdom. Issuers were mostly corporations in those three emerging markets, and total funds raised in Mexico, India, and Brazil were USD 10.1 billion, USD 8.8 billion, and USD 8.2 billion, respectively, between 2000 and 2021.

Figure 2.18. Green bond issuances from Brazil and selected countries between 2000-21

Note: Others include agencies, governments, treasuries, central banks, supranational, and municipalities.

Source: Refinitiv, B3, see Annex for details.

Green bonds are usually defined as bonds whose proceeds are used to invest in a portfolio of projects with positive environmental results. There are two other similar bonds, which are named “social bonds” if their proceeds should be directed to projects with positive social results and “sustainability bonds” in case the portfolio of projects aims at both environmental and social positive impacts. There is, however, another category called “sustainability-linked bonds” (SLB) whose proceeds may be used for general corporate purpose, and not specifically for a portfolio of projects (ICMA, 2020[12]). In SLBs, the characteristics of the bonds (usually the interest rate paid to the bond) vary according to the sustainability performance of the company. Typically, the company needs to pay a higher coupon if it did not reach a predefined sustainability performance target.

Globally, the amount of funds raised via sustainability, social and sustainability-linked bonds increased significantly to USD 472 billion in 2021 from USD 81 billion in 2019 and USD 28 billion in 2018.5 The share of corporations in total amount of funds raised between 2018 and 2021 was on average one‑third of the yearly issued funds. In Brazil, first sustainability-linked bond issued in 2020,6 and then there have been five social bonds and two more sustainability-linked bonds issued during the last two years. Total amount of funds raised of these bonds was USD 3.7 billion.

GHG emissions markets

Limiting global warming to 1.5ºC above pre‑industrial levels would effectively require CO2 emissions to decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero emissions around 2050 (IPCC, 2018[13]). So far, 165 jurisdictions have presented a national plan (named as nationally determined contribution) on how they will reduce GHG emissions in line with the Paris Agreement (so-called “national determined contributions”). However, total global GHG emissions level in the existing nationally determined contributions of Parties to the Paris Agreement by 2030 is still projected to be 15.9% higher than in 2010 and 4.7% higher than in 2019 (UN, 2021[14]). In this respect, with a view to increase the efforts towards net zero emissions, during COP26 in November 2021, governments agreed on the Glasgow Climate Pact to accelerate action on coal, deforestation, electric vehicles and methane, and they finalised the outstanding elements of the Paris Agreement, including the establishment of a new mechanism and standards for international carbon markets (UN, 2021[15]).

Table 2.3. Summary of national and regional emission trading systems

|

EU ETS |

NZ ETS |

RGGI |

WCI |

SK ETS |

China ETS |

UK ETS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Start date |

2005 |

2008 |

2009 |

2013 |

2015 |

2021 |

2021 |

|

Percent economy-wide emissions covered by ETS |

~40% |

~50% |

~10% |

California: 75% Quebec: 78% |

~75% |

~40%(*) |

~10% |

|

2030 reduction target |

At least 55% |

30% |

30% |

California: 40%. Quebec: 37.5% |

24.4% |

65% |

68% |

|

Reduction target on |

GHG Levels |

GHG Levels |

GHG Levels |

GHG Levels |

GHG Levels |

CO2 emissions per unit of GDP |

GHG Levels |

|

Base year for reduction target |

1990 |

2005 |

2020 |

1990 |

2017 |

2005 |

1990 |

|

Total market value of ETS in 2021 (EUR million) |

682 501 |

2 505 |

49 260 |

798 |

1 289 |

22 847 |

|

Note: (*) For power sector only, gradually expanding to 75% during 2021‑25 of sectors including petrochemical, chemical, building materials, steel, nonferrous metals, paper, and domestic aviation.

Source: Refinitiv.

In terms of carbon trading, the finalisation of the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 during COP26 text was an important outcome that sets the rules for how countries may use trading to help achieve their national climate targets and affects how firms will seek to achieve corporate carbon reduction targets. The final rules include safeguards to prevent “double counting” of emission reductions. Article 6 creates a unit called an Internationally Traded Mitigation Outcome (ITMO) representing an amount of reduced or avoided emissions, which by definition requires the seller country to deduct that amount of emission reduction in terms of reaching its declared national climate target. These accounting requirements, which are called “corresponding adjustments”, ensure that each unit of emission reduction is only considered as a credit by the party that paid for it.

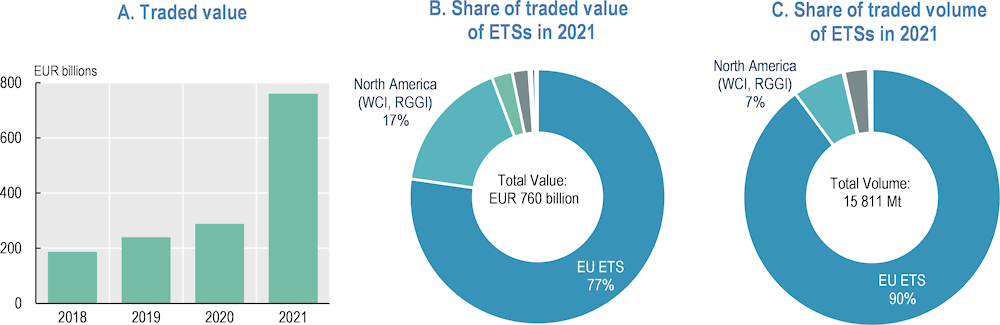

There has been a gradual increase in the traded value of the emission trading systems (ETSs) with a significant expansion in 2021. The traded value in 2021 reached EUR 760 billion, which was 2.5 times the value traded in the previous year (Figure 2.19, Panel A). In 2021, the European ETS had the highest share traded value and volume among the seven major ETSs provided in Table 2.3 (see Figure 2.19, Panels B and C). Introduced in July 2021, the People’s Republic of China (China)’s national ETS had a market value at around EUR 1.3 billion as of end 2021. Brazil does not currently have an emissions trading system, but a bill of law that would regulate such a market (“Projeto de Lei n. 528/21”) has been approved by all relevant commissions in Congress’ Lower Chamber.

Figure 2.19. Summary statistics of emission trading systems

Notes:

1: Amounts include the EU ETS, the UK ETS, from North America the WCI, RGGI, and the emerging market in Mexico, in China the regional pilot ETS, offset trading (CCERs) and the national China ETS, from Korea (SK ETS), from New Zealand, NZ ETS, and an assessment of what is left of global offset transactions from the old Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) market.

2: For the EU ETS, traded volume and value include spot, auctions and futures, but option positions are not included. For China, traded volume includes allowance units for pilot ETS, national ETS (for 2021), and CCER transactions, and traded value includes only allowances.

Source: Refinitiv.

Voluntary carbon credit markets allow entities not covered by ETS to manage their carbon footprint or to raise private financing for projects with positive contributions for the climate transition (TSVCM, 2021[16]). In the case when a company with a self-imposed target of net-zero emissions, it can acquire carbon credits sold in these markets. For a system of carbon credits or permits to work efficiently, however, the certification of emissions reduction and carbon captured must be credible (just like external auditors and custodians are needed for a stock market to flourish) and flows of negotiation should be as free as feasible (so that carbon emission’s reductions are achieved for the smallest possible costs). Standardisation of carbon credits is especially important to facilitate trading flows, cross-border negotiations and price‑discovery.

The voluntary carbon markets are still evolving. In general, transactions of offsets in the voluntary carbon markets take place “over the counter” (OTC) on a bilateral basis. Since only a limited share of total voluntary carbon market transactions takes place on exchanges, there is no source for aggregated traded volumes and prices. However, during 2021, companies increasingly preferred centralised marketplaces than the OTC (Refinitiv, 2021[17]). Total traded value in centralised voluntary carbon markets reached its annual peak value in early November 2021 with USD 1 billion. Total traded volume between January and November 2021 also reached to almost 300 million tonnes, which represents a significant increase from 188 million tonnes in 2020 and 104 million tonnes in 2019. This has been reflected by the increase in the average volume‑weighted price of offsets: from USD 2.5 per tonne in 2020 to USD 3.5 per tonne in 2021 (Refinitiv, 2021[17]).

References

[2] B3 (2022), Listing segments, https://www.b3.com.br/en_us/products-and-services/solutions-for-issuers/listing-segments/nivel2/.

[1] B3 (2017), Comparative list of segments.

[10] Darvas, Z. and G. Wolff (2021), A green fiscal pact: climate investment in times of budget consolidation.

[6] De La Cruz, A., A. Medina and Y. Tang (2021), “Institutional ownership in today’s equity markets”, (Forthcoming).

[5] De La Cruz, A., A. Medina and Y. Tang (2019), “Owners of the World’s Listed Companies”, OECD Capital Market Series, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/Owners-of-the-Worlds-Listed-Companies.htm.

[12] ICMA (2020), Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles, https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Regulatory/Green-Bonds/June-2020/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-June-2020-171120.pdf.

[9] IEA (2021), Net Zero 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/beceb956-0dcf-4d73-89fe-1310e3046d68/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf.

[13] IPCC, I. (2018), Global warming of 1.5°C: Summary for Policymakers, https://www.ipcc.ch/.

[3] OECD (2022), “Corporate Finance in Asia and the COVID-19 Crisis”, OECD Capital Market Series, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/asia/corporate-finance-in-asia-and-the-covid-19-crisis.htm.

[11] OECD (2022), OECD Sovereign Borrowing Outlook 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2d85ea7-en.

[7] OECD (2021), Background Note on Institutional Investor Ownership in Latin American Equity Markets, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/ca/Institutional-investors-background-note-Latin%20America-2021.pdf.

[4] OECD (2021), The Future of Corporate Governance in Capital Markets Following the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/efb2013c-en.

[8] OECD (2017), Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273528-en.

[17] Refinitiv (2021), Carbon Market Year in Review 2021.

[16] TSVCM (2021), Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets - Final Report, https://www.iif.com/tsvcm.

[14] UN (2021), Nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/nationally-determined-contributions-ndcs/ndc-synthesis-report#eq-5 (accessed on 20 December 2021).

[15] UN (2021), The Glasgow Climate Pact – Key Outcomes from COP26, https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf.

Notes

← 1. The MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) ESG Leaders Index is a capitalisation weighted index that provides exposure to companies with high ESG performance relative to their sector peers. MSCI EM ESG Leaders Index consists of large and mid-cap companies across 24 EM economies.

← 2. OECD Capital Market Series Dataset.

← 3. See, for instance, Regulation EU 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment.

← 4. OECD Capital Market Series Dataset.

← 5. Refinitiv, see Annex for details

← 6. In September and November 2020, Suzano Austria issued a sustainability-linked bond in Brazil raising two separate proceeds of USD 750 million and USD 500 million, respectively. The bonds have KPIs aimed to reduce GHG emissions of the company by 2025 and if the company does not fulfil this sustainability performance target, the interest rate payable on the bonds will increase by 25 basis points from 2026 until the maturity of the bond in 2031.