This chapter assesses policies in the Western Balkans and Turkey that support efficient bankruptcy legislation for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and promote a second chance for failed entrepreneurs. It first provides an overview of the assessment framework and progress since the last assessment in 2019. It then analyses the three sub‑dimensions of Dimension 2: 1) preventive measures, which assesses tools and policies to help SMEs avoid bankruptcy; 2) survival and bankruptcy procedures, which investigates the economies’ insolvency regimes for SMEs; and 3) promoting second chance, which examines policies to help failed entrepreneurs make a fresh start in business. Each sub‑dimension makes specific recommendations for increasing the capacity and efficiency of bankruptcy and second chance in the Western Balkans and Turkey.

SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2022

2. Bankruptcy and second chance for SMEs (Dimension 2) in the Western Balkans and Turkey

Abstract

Key findings

Mechanisms to prevent bankruptcy remain underdeveloped in the region. The Western Balkans and Turkey (WBT) economies introduced interim measures to support an increased number of enterprises facing financial distress caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, insolvency prevention mechanisms that help businesses avoid bankruptcy were largely not included, undermining the economies’ overall capacities to handle an increased number of insolvencies during the pandemic.

Insolvency laws that govern formal bankruptcy liquidation and restructuring procedures are in place in all WBT economies. All governments have introduced varying forms of hybrid pre-insolvency prevention procedures, each of which provides for restructuring plans for settlement with creditors1 created by the debtor,2 after which they are formally confirmed by the courts and become binding for all parties.

Most WBT economies have a formal bankruptcy discharge procedure included in their legal frameworks. None of the governments has set a legal time limit for entrepreneurs to obtain a discharge, however.

Monitoring and evaluation of insolvency policies in the region remain weak. Most WBT economies still lack proper monitoring and evaluation systems that cover data on case duration, cost of proceedings, and share of claims recovered by creditors in bankruptcy or restructuring procedures. This is evidenced by a plateau in the measured indicators from 2019 to 2020, coupled with ineffective public insolvency registers.

Further digitalising procedures across WBT economies could optimise liquidation processes. Several economies have introduced electronic bidding options for assets sold in bankruptcy liquidation proceedings. However, administratively burdensome and financially inefficient procedural rules remain, except for North Macedonia, where the entire liquidation procedure has been fully digitalised since 2017.

Second-chance policies for failed entrepreneurs3 are still largely absent in the region. Public institutions in the region are remiss in their efforts to reduce the cultural stigma attached to business failure.

1. A creditor is a company or person that gives another entity permission to borrow money to be repaid in the future or provides supplies or services and does not demand immediate payment.

2. A debtor is a company or individual who owes money. Legally, someone who files a voluntary petition to declare bankruptcy is also considered a debtor.

3. Due to divergent approaches across different economies and for better comparability across this chapter, “entrepreneurs” is not limited to sole proprietors, the self-employed, one person companies, or micro and small enterprises. All forms of business organisations are referred to as entrepreneurs in this chapter.

Comparison with the 2019 assessment scores

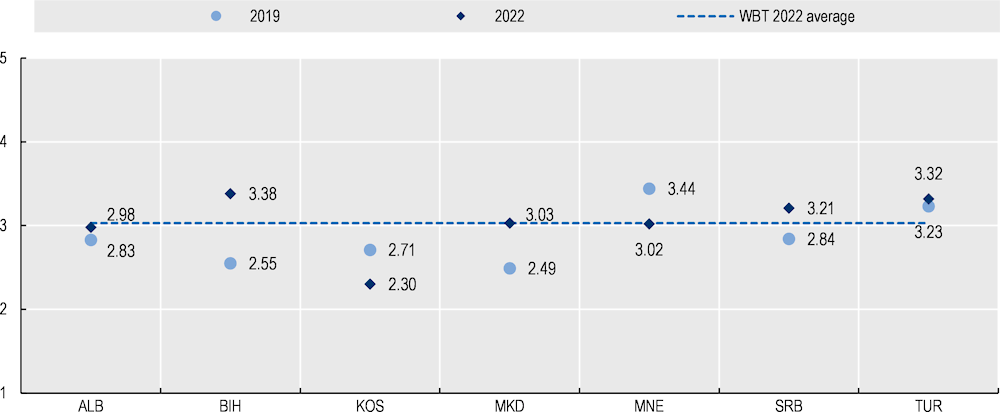

The performance of the WBT region in bankruptcy and second-chance policies has slightly improved since the last assessment. The region’s average score increased from 2.87 in 2019 to 3.02 in 2022, in part due to mitigation measures taken during the COVID‑19 pandemic (Figure 2.1).

Further, the progress achieved by some of the economies is more pronounced than the regional average suggests. Compared with the previous assessment, Bosnia and Herzegovina has made the most significant improvement, with the harmonisation of its bankruptcy policies throughout the territory and its newly introduced hybrid pre-insolvency restructuring and settlement mechanism. Moreover, Turkey has further enhanced its preventive concordat, while Albania has introduced a new pre-insolvency, preventive, out‑of-court restructuring settlement.

Figure 2.1. Overall scores for Dimension 2 (2019 and 2022)

Notes: WBT: Western Balkans and Turkey. Despite the introduction of questions and expanded questions to better gauge the actual state of play and monitor new trends in respective policy areas, scores for 2022 remain largely comparable to 2019. To have a detailed overview of policy changes and compare performance over time, the reader should focus on the narrative parts of the report. See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations

Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations on bankruptcy and second-chance policies has remained limited across the Western Balkans and Turkey. Most progress has been seen in the economies’ legal frameworks. However, as in the previous assessment, improvement has been limited. No concrete steps have been taken to establish bankruptcy prevention mechanisms, such as early warning systems, and little has been done to promote second-chance mechanisms for entrepreneurs (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations for Dimension 2

|

2019 recommendation |

SME Policy Index 2022 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Main developments during the assessment period |

Progress status |

|

|

Develop a fully fledged early warning system |

None of the economies has implemented a fully fledged early warning system, and there continues to be a lack of strategic policy thinking when it comes to insolvency prevention mechanisms. |

No progress |

|

Introduce SME and entrepreneur fast‑track bankruptcy proceedings into the law |

Some simplification measures, such as fast-track procedures and reorganisation processes, have been implemented. None, however, are tailored to small and medium-sized enterprises' (SMEs) needs. |

Limited |

|

Allow the automatic discharge of entrepreneurs after liquidation |

No improvement in debt discharge mechanisms has been observed since the previous assessment. |

No progress |

|

Create a monitoring and evaluation process for bankruptcy mechanisms |

No progress in establishing a monitoring and evaluation process for bankruptcy mechanisms has been recorded since the previous assessment. |

No progress |

|

Enhance and adapt the administrative capacities of the bodies implementing the insolvency legislation |

Some economies have introduced higher standards regarding qualifications, examinations and licensing for bankruptcy administrators. However, no special capacity-building events or trainings were organised to enhance institutional capacity. |

Limited |

|

Further reduce the average cost and duration of bankruptcy proceedings by simplifying parts of the bankruptcy legislation |

Bankruptcy procedures remain administratively burdensome and costly across the region. |

No progress |

|

Conduct awareness campaigns among entrepreneurs to promote out-of-court settlements as a less expensive alternative to filing for bankruptcy |

Under normal circumstances, promotional campaigns for using out-of-court settlement as a less expensive and less administratively burdensome proceeding would positively impact the prevention of insolvency. However, due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, this recommendation was not prioritised, as economic recovery became the priority. |

Not applicable |

|

Introduce policy measures granting a second chance for honest entrepreneurs |

No progress has been recorded on granting access to SMEs and honest1 entrepreneurs a second chance. |

No progress |

|

Improve the legal framework and develop initiatives to reduce the cultural stigma attached to entrepreneurial failure |

No progress has been recorded in reducing the cultural stigma attached to entrepreneurial failure. The insolvency laws provide clear rules for treating cases where debtors file a petition with intent to deceive, defraud or subvert the creditors. However, there is no information allowing future partners and creditors to distinguish honest from fraudulent, failed entrepreneurs. |

No progress |

1. The current international consensus on the definition of “honest” versus “dishonest” entrepreneurs presumes that an honest entrepreneur has not conducted avoidable fraudulent or preferential transactions or been penalised by tax authorities or charged by a court for criminal activities. An honest failed entrepreneur should get discharged of all possible forms of debt.

Introduction

An efficient business environment depends on the stability of the businesses that comprise it. Enterprises that continuously generate debt and encounter financial distress can obviously impact a business environment’s health and prosperity. Thus, policies that ensure a seamless and timely market exit of enterprises whose further operation may negatively affect a business environment are crucial to ensuring any economy’s long-term sustainable economic growth.

Prior to the European Commission’s recommendations on the New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency in 2014, bankruptcy liquidation procedures were typically initiated by interested creditors and managers and owners of debtor companies (European Commission, 2014[1]). In a minority of cases, insolvent companies were saved through recovery and restructuring plans agreed upon by a required majority vote of creditors during insolvency procedures and later confirmed by courts, resulting in a binding judicial decision. However, many cases ended in liquidation due to late interventions to turn such businesses around. There were also inadequate legal provisions in bankruptcy laws that required companies to be over-indebted, or have a debt greater than total assets, before courts could officially open bankruptcy proceedings.

According to the World Bank’s Resolving Insolvency indicator in its Doing Business Report, 70.2% of debt was recovered by creditors in OECD member countries in 2019, but only 38.2% on average in the WBT economies, implying an approximate 60% loss of value (World Bank, 2019[2]).

Following the 2008 financial crisis and a major wave of insolvencies, there were calls to establish a universal bankruptcy regime suitable for all affected parties. As a result, the European Commission adopted a Recommendation on the New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency in 2014 (European Commission, 2014[1]), the European Insolvency Regulation Recast in 2015 (European Union, 2015[3]), and the Preventive Restructuring Directive in 2019 (European Union, 2019[4]).

The wave of new legislation aimed to refocus Europe’s policies on preventive restructuring and out‑of‑court insolvency prevention settlements between the debtor and its creditors; updating the rules on cross-border insolvency; and introducing new policies on early warning systems and second chance for failed entrepreneurs. The prevention of insolvency was recognised as a major factor in maintaining a financially healthy business environment. Meanwhile, the adoption of restructuring plans of financially distressed businesses by creditors became possible should the plan propose higher recovery for creditors than bankruptcy liquidation, thus allowing policies supporting restructuring plans to increase savings and recovery values for creditors and debtors, respectively.

The COVID‑19 pandemic and the resulting restriction of economic activity in many sectors, which caused unexpected financial crises, coincided with the introduction of preliminary insolvency prevention recommendations by the WBT economies. The region focused its mitigation efforts on reallocating insolvency prevention efforts from company‑specific cases to economy-wide prevention instruments to overcome widespread, systematic financial distress. Business support measures to help enterprises avoid current and future bankruptcy varied from temporary bans on filing insolvency of debtors and offsetting payments of debt to the rescheduling of debt payments, quasi loan subsidies, and direct financial aid and subsidies to businesses and citizens.

However, the financial measures adopted by the WBT governments only provided temporary relief to companies, after which increased insolvencies are expected. According to Allianz, a leading insurance company, the risk of debtor non-payment is expected to increase, and 7‑15% of European SMEs are at risk of insolvency in the next several years (Kuhanathan and Boata, 2021[5]). Dutch Experian, another major EU insurance company, predicts that 1 in 16 (6.25%) small businesses will default by the third quarter of 2022 (Dutch Experian, 2021[6]).

It remains crucial for WBT economies to introduce appropriate measures and legal provisions that promote the prevention of insolvency. They will also need to create positive attitudes around giving entrepreneurs a fresh start and ensure that those starting again have the same market opportunities they had the first time. Likewise, adequate attention should be given to the criteria for granting second-chance procedures to honest entrepreneurs, focusing on those who can propose viable plans. In this context, effective bankruptcy regulations will be essential to ensure a positive impact on companies’ market exits and reduce the opportunity cost of entrepreneurship by creating more welcoming conditions for the establishment of new businesses.

Assessment framework

Structure

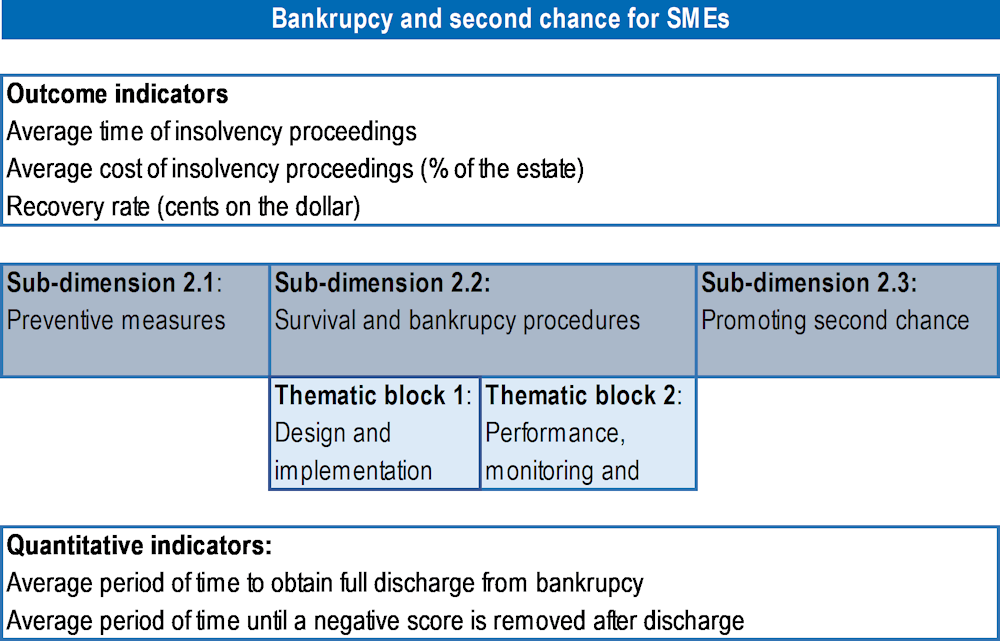

This chapter focuses on bankruptcy and second-chance policies for SMEs. The assessment framework is divided into three sub-dimensions:

Sub-dimension 2.1: Preventive measures looks at the existence of alternatives to in-court bankruptcy processes, such as the establishment of early warning systems and out-of-court settlement mechanisms that the economies use to help SMEs avoid bankruptcy.

Sub-dimension 2.2: Survival and bankruptcy procedures focuses on legislation and practice and their alignment with international standards. It looks at whether survival procedures, such as reorganisation procedures, exist and how they operate. It assesses policy performance, first in design and implementation then in performance, monitoring and evaluation.

Sub-dimension 2.3: Promoting second chance examines how the economies facilitate a second chance for failed entrepreneurs, assessing attitudes towards giving honest entrepreneurs a fresh start. It specifically looks at the existence of training, information and second-chance campaigns.

Figure 2.2 shows how the sub-dimensions and their fundamental indicators make up the assessment framework for this dimension. For more information on the methodology, see the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A.

Figure 2.2. Assessment framework for Dimension 2: Bankruptcy and second chance for SMEs

Notes: The outcome indicators serve to demonstrate the extent to which the policies implemented by the government bring about the intended results, and they have not been taken into consideration in the scoring. By contrast, quantitative indicators, as a proxy for the implementation of the policies, affect the overall scores. As for the outcome indicators, they refer to those derived from the World Bank Doing Business Report, which was discontinued in 2020. Therefore, the latest data refer to 2019, with the last published report being the 2020 edition.

Compared to the 2019 assessment, minor adjustments have been made to the framework to enhance the importance of the bankruptcy and second chance for SMEs, translated by a more in-depth analysis of Sub‑dimension 2.2. The assessment also considers COVID‑19 response measures, although no evaluation has been made in this regard. Moreover, the indicator on out-of-court settlements, previously considered under Sub-dimension 2.2, was split into: 1) out-of-court settlements without court involvement, as a preventive measure under Sub-dimension 2.1; and 2) out-of-court settlements with the involvement of the court, considered under Sub-dimension 2.2. However, it should be noted that in practice, there is no clear division, as the process is intertwined.

Analysis

Performance in bankruptcy and second chance

Outcome indicators play a key role in examining the effects of policies. They provide crucial information for policy makers to judge the effectiveness of existing policies and the need for new ones. Put differently, they help policy makers track whether policies are achieving the desired outcome. The outcome indicators chosen for this dimension are designed to assess the WBT economies’ performance in resolving insolvency. This section starts by drawing on the indicators to describe this performance.

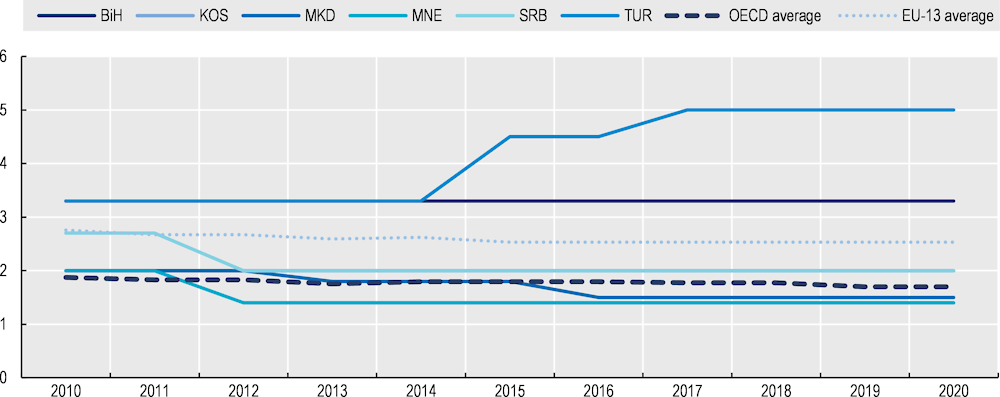

The region’s performance has, on average, remained close to the same levels as in the previous assessment. No progress has been recorded in terms of the time required to resolve insolvency. Turkey remains the lengthiest economy to resolve an insolvency case, while Montenegro remains the fastest (Figure 2.3) (World Bank, 2019[2]).

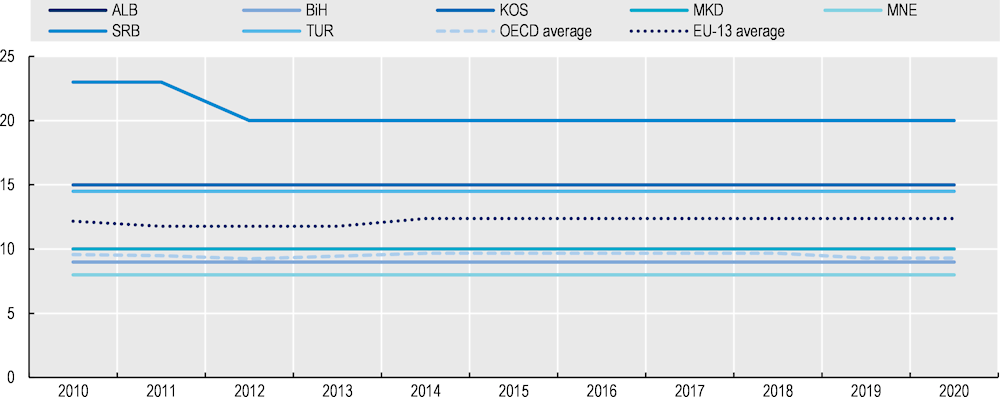

The cost of resolving insolvency has remained at the same levels as the previous assessment. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro are the only economies that outperform the OECD average, while Kosovo1 and Serbia have the highest costs for resolving insolvency (Figure 2.4) (World Bank, 2019[2]).

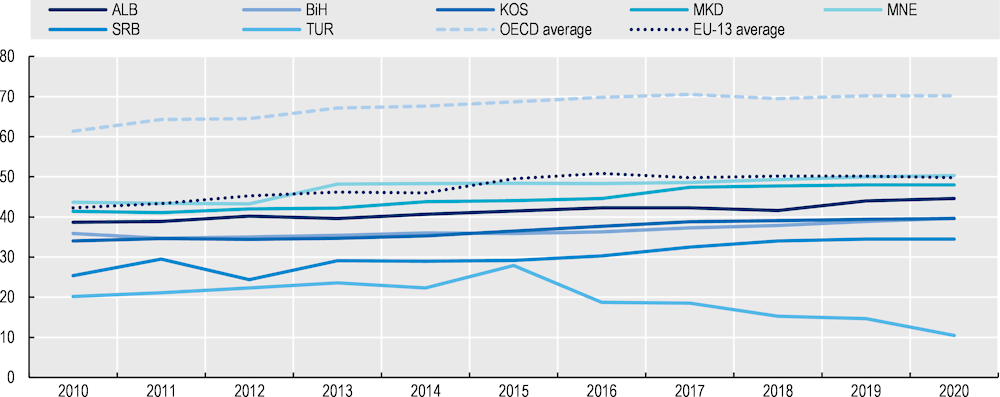

Since 2018, the recovery rate has increased for all economies in the Western Balkans. In 2020, it averaged 42.8 cents on the dollar, while in Turkey the rate continued to decrease and dropped to 10.5 cents on the dollar (Figure 2.5). All WBT economies are still performing below the OECD average (World Bank, 2019[2]).

Figure 2.3. Time taken to resolve insolvency (2010-2020) (Years)

Notes: Data for Japan, Mexico and the United States are missing for 2010‑12 when calculating the OECD average; data for Malta are missing for 2010 when calculating the EU-13 average.

EU-13 member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: Based on data from World Bank (World Bank, 2020[7])

Figure 2.4. Cost of resolving insolvency (2010-2020) (% of estate)

Notes: Data for Japan, Mexico and the United States are missing for 2010‑12 when calculating the OECD average; data for Malta are missing for 2010 when calculating the EU-13 average.

EU-13 member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: Based on data from World Bank (World Bank, 2020[7])

Figure 2.5. Recovery rate for resolving insolvency (2010-2020) (cents on the dollar)

Notes: Data for Japan, Mexico and the United States are missing for 2010‑12 when calculating the OECD average; data for Malta are missing for 2010 when calculating the EU-13 average.

EU-13 member states: Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Romania, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia.

Source: Based on data from World Bank (World Bank, 2020[7])

Preventive measures (Sub-dimension 2.1)

Swift government intervention in providing assistance to SMEs and entrepreneurs who foresee financial difficulties or failures is crucial. It hinges on timely detection of financial vulnerabilities that can impact an enterprise’s chances of survival. Therefore, initiatives such as diagnostic tools and information services form the backbone of a successful government strategy to prevent bankruptcy.

Overall, prevention mechanisms include: 1) early warning tools and systems designed to provide timely warning signals regarding financial distress, based on self-tests or other preferred methods; 2) business advisory and mentoring support services to companies in financial distress; 3) voluntary out-of-court settlements between a debtor and its creditors; and 4) hybrid or pre-insolvency prevention procedures negotiated out of court between a debtor and its creditors. The first three mechanisms are considered entirely preventive, while the fourth is a hybrid between an out-of-court settlement and a formal court rehabilitation procedure.

There continues to be a lack of strategic policy making in WBT economies when it comes to insolvency prevention mechanisms. Insolvency is only considered to the extent of formal bankruptcy legislation, limiting the scope of insolvency prevention mechanisms.

Overall, no major progress has been recorded since the previous assessment; preventive measures remain limited in the region (Table 2.2). While Albania and Turkey are the top performers when it comes to preventive measures for bankruptcy and insolvency, Bosnia and Herzegovina recorded the highest increase since the 2019 assessment.

Table 2.2. Scores for Sub-dimension 2.1: Preventive measures

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Weighted average |

3.10 |

2.80 |

2.20 |

2.80 |

2.50 |

2.80 |

3.00 |

2.74 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Fully fledged early warning systems for distressed SMEs are still lacking

Early warning systems can help prevent bankruptcy and liquidation by promptly detecting signs of financial distress so that businesses can obtain assistance to successfully restructure before irreparable damage is done. As SMEs can often underestimate their degree of financial difficulties and delay taking appropriate measures to lessen their financial burdens, governments can implement early warning systems that urge SMEs to initiate restructuring procedures quickly, helping lower the risks of bankruptcy by acting quickly.

WBT economies generally lack early warning mechanisms and have a limited notion of how to develop them or the type of best practice models most suitable to adapt and use. In all economies, except the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina enity, public institutions have established initiatives that act as early-stage warning systems, detecting indications of distress through financial tools, such as tax declarations or bank loans. However, these tools can miss signs of financial trouble, particularly when it comes to SMEs. For example, not all debtors apply for bank loans, as they often do not fulfil the conditions for institutional financing, such as collateral or credit requirements. Likewise, in cases where annual financial statements are submitted to the tax authorities, it may already be too late to resolve problems using only advisory services.

Nevertheless, some initial editions of early warning systems exist in the region. In Kosovo, for example, the tax administration monitors the performance of companies and implements basic insolvency preventive measures. It notably runs “basic” early warning tools based on companies’ annual financial statements. However, as this mechanism bases its warnings on yearly financial statements, which can lead to belated signals of distress, rendering it ineffective in preventing some bankruptcy cases, it is not considered a fully fledged early warning system.

Some banks and private credit registries have also developed their own mechanisms to assess customers’ credit performance by drawing on information from multiple sources such as tax declarations, social security declarations and balance sheets. These mechanisms have been designed to reduce the number of non-performing loans rather than avoid liquidation. In some cases, banks or private credit registries assign a risk classification. For instance, Montenegro’s Central Bank is obliged by law to collect data from different banks on entrepreneurs whose accounts are blocked and publish them on their website. While this system allows financially distressed companies to be identified before they file for bankruptcy, it still does not provide enough time, nor a solution, to reorganise the firm and the debt to prevent bankruptcy.

Out-of-court settlements and restructuring procedures remain largely underdeveloped

An out-of-court settlement is a practical tool used in situations where business advisory or mentoring services alone cannot resolve issues of financial distress for companies. It provides a softer solution to companies in pre-insolvency situations, where debt is rescheduled or refinanced based on the willingness of creditors. The debtor initiates this voluntary procedure, and the agreement is binding only to the creditors who voted for the restructuring of the debt in the presence of a public notary. The COVID‑19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of various effective out-of-court mechanisms, particularly in OECD member countries. The WBT economies could use these mechanisms as guidance for updating their own frameworks on alternative methods of insolvency resolution (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Out-of-court settlement in selected OECD member countries as a response to EU Directive 2019/1023

After adopting EU Directive 2019/2023 on preventive restructuring frameworks,1 EU member countries introduced widespread reforms to restructure their legal frameworks regarding enterprises in financial distress, focusing on precautionary rather than retroactive measures.

Much like the 2008 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic made it necessary to once again reshape how insolvency and bankruptcy procedures are carried out, putting a large emphasis on moving insolvency restructuring to out-of-court legal solutions.

For instance, in 2021, the Netherlands introduced a new Law on the Confirmation of Private Restructuring Plans (WHOA) under the Dutch Bankruptcy Act, which makes predominantly out-of-court restructuring procedures available to companies in financial distress. Much like the legal solutions set out in the US Chapter 11 procedure and EU Directive 2019/2023, the WHOA allows the debtor, creditors and shareholders2 to jointly propose a viable restructuring plan to meet the debtor’s financial obligations, which is then voted on by creditors and shareholders, requiring a two-thirds majority in both groups to be approved. Once private consensus is achieved, the new plan is subject to court confirmation, after which it becomes binding on all affected creditors and shareholders if confirmed. Under the WHOA, in special cases, the court can impose a binding cross-class cram-down,3 whereby a restructuring plan is enforced against reluctant shareholders or any class of dissenting creditors.

In 2020, the United Kingdom introduced the Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020 (CIGA 2020), a new procedure under which restructuring plan options are made available to all enterprises encountering financial distress that may affect their ability to continue operating. Under the act, the debtor must propose an arrangement to its creditors and shareholders to eliminate, reduce, prevent or mitigate the effects of financial distress undergone by the enterprise. Although CIGA 2020 was introduced with a number of temporary provisions to mitigate the strain of the pandemic on companies, the majority of the reforms included will be permanent.

Similarly, Germany adopted a new framework in 2021 that allows debtors to restructure their financial commitments outside of formal insolvency proceedings before filing for official insolvency. The procedure permits debtors to submit restructuring plans for any form of debt, as well as modifications of equity and collateral rights, including guarantees provided by associated companies, to creditors for approval. Like the WHOA, the new German procedure also allows for cross-class cram-downs that bind dissenting shareholders and creditors to restructuring plans. Additionally, the updated law allows debtors to access new options for early financial restructurings in lieu of the long‑established German insolvency procedure, giving debtors control of their businesses during restructuring procedures for the first time by allowing them the chance to restructure their debts outside of official procedures that would require a majority vote.

1. The Directive (EU) 2019/1023 of the European Parliament and of the Council on preventive restructuring frameworks, on discharge of debt and disqualifications, and on measures to increase the efficiency of procedures concerning restructuring, insolvency and discharge of debt, and amending Directive (EU) 2017/1132 (Directive on restructuring and insolvency) can be accessed at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019L1023&from=EN.

2. A shareholder is a company or person who owns shares in a company and therefore gets part of the company’s profits and the right to vote on the company’s management.

3. The term “cross-class cram-down” refers to a situation where a restructuring plan can be imposed on an entire class of dissenting creditors or members.

In the current context, out-of-court settlement procedures in the region are scarce and generally underdeveloped in cases where they do exist. In Serbia, the Law on Consensual Financial Restructuring allows the debtor to initiate an out-of-court settlement, albeit only under the condition that it is supported by at least one financial institution, usually a bank, with the aim of resolving problematic non-performing loans. While Turkey has also introduced a similar procedure for financial restructuring, as a COVID‑19 recovery measure, with the active support of the Association of Turkish Banks, the new scheme is temporary and expires in 2023. Nevertheless, approximately TRY 5 billion (around EUR 285 million) of debts have been successfully resolved through this procedure since its implementation. In February 2021, Albania introduced a new insolvency prevention regulation on accelerated extrajudicial reorganisation agreements, which is expected to enhance bankruptcy prevention, although certain deficiencies have been noted. Meanwhile, Montenegro has revoked a similar law since the last assessment and currently does not have a law regulating out-of-court settlements. The remaining economies in the WBT region do not have particular legal solutions on out-of-court settlements for financially distressed companies.

Hybrid or pre-insolvency restructuring procedures are in place in most WBT economies

Hybrid insolvency procedures combine both out-of-court and formal court elements and can be an effective solution for minimising the cost and delay associated with formal restructuring procedures. This type of process can also help circumvent long-term disagreements between debtors and creditors by overruling dissenting opinions among creditors (IMF, 1999[10]). These procedures are initiated as out-of-court settlements and are then finalised during an in-court process, binding the agreed-upon restructuring schemes for all creditors.

The insolvency frameworks of all WBT economies, with the exception of Albania and Montenegro, comprise either pre-insolvency restructuring plans, pre-packaged reorganisation plans or preventive concordat hybrid procedures. Similar to good practices implemented in OECD member countries, a debtor’s pre-insolvency plans that are not accepted by creditors and/or not confirmed by the court can be subject to superseding the court’s authority in overruling the initiation of liquidation processes. Consequently, the debtor remains in possession of its assets and manages its operations under the supervision of a bankruptcy administrator, making the process faster and cheaper than in-court reorganisation procedures.

The length of pre-insolvency proceedings varies in the region. In 2021, proceedings in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia took, on average, eight months to close a case. In Serbia, pre‑packaged, fast-track insolvency reorganisations were generally completed within three months, while preventive concordats in Turkey took approximately one year. However, there is no comparable data for the remaining economies, making it difficult to draw region-wide conclusions.

The way forward for preventive measures

Develop insolvency prevention policy measures, including a fully fledged early warning system, as SMEs tend to underestimate the importance of maintaining a sound financial status and avoiding riskier decisions. If appropriate corrective actions are not taken promptly, companies are likelier to face financial distress and later insolvency, especially in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic. One option could be to widen the scope of the existing advisory support services, including the creation of anonymous self-check tests to identify possibilities to resolve early financial distress. The selection of the right system is subject to the size of the economy, the number of registered entities, digitalisation of financial reporting and public awareness of existing preventive measures. Experience and good practices implemented in EU member states could serve as a good example for WBT economies in selecting an appropriate model of early warning systems (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Early warning systems in the European Union

Early warning tools may include different instruments: alert mechanisms when the debtor has not made certain types of payments; advisory services provided by public or private organisations; and incentives under national law for third parties with relevant information about the debtor, such as accountants and tax and social security authorities, to flag to the debtor a negative development.

In the European Union, there are two competing models for early warning systems:

1. Self-assessment tool: Creating tools for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and entrepreneurs to anonymously assess their economic situation. The self-test tool can be a simple software application on a public website. SMEs and entrepreneurs have only to enter basic financial data about their business. The application will produce a preliminary diagnostic with recommendations for remediation actions, like searching for a specific business advisory or mentoring support service. The application conducts a financial ratios diagnostic analysis. The quality of the diagnostic analysis depends on the quantity and quality of the data intake by the entrepreneur.

This model is useful as a quick financial health check and should be complemented with a business advisory support service by a public institution or access to a commercial or professional association.

2. Intervention mechanism: This includes a series of steps to remedy the distress situation under external supervision. The mechanism is based on an early warning signal triggered for the SME, identification of problematic areas causing financial distress and reporting to company management with recommendations to take remedial measures. The process to remedy the identified issues then follows through a series of interventions by different actors, aiming to avoid company insolvency. The process can include:

A company bookkeeper or external auditor spots an observation that may lead to financial distress. The early warning mechanism can be built on an obligation of the bookkeeper or auditor to inform the company’s management of the issue.

If management does not take action to remedy the situation, there may be subsequent communications with the board or even at the shareholders’ meeting.

If there is no adequate reaction of the enterprise organs, the mechanism can prompt the intervention of outside bodies, such as special mediation, or even trigger a special preventive measure court procedure.

Finally, if there is no intervention, the system may provide for creditors’ actions related to the use of alternative dispute resolution.

Public creditors can play a significant role in an early warning system as they can identify a delay in tax and social security payments, a warning that enterprises are experiencing financial difficulties. Information on late payments should be carefully used together with diagnostic analysis, as companies tend to pay only public debt to avoid early warning detection mechanisms.

Source: IMF (2021[11]).

Provide permanent advisory and mentoring services to financially distressed companies. The provision of business advisory services for companies in financial distress should be converted to permanent services in cases where such services are temporary, as a sort of a so-called “pre‑insolvency clinic” instead of a time-bound project. Consistent new market entries are accompanied by a higher proportion of companies that may potentially find themselves in financial distress and thus need support to avoid negative externalities that could spread to other operating entities in the business ecosystem. Adding early restructuring services to existing ones, such as export promotion services, partner networking, business planning or financial management, would help strengthen preventive measures.

Survival and bankruptcy procedures (Sub-dimension 2.2)

Insolvency frameworks protect a debtor’s and creditors’ rights in cases of imminent insolvency or over‑indebted insolvent companies. Such legislation offers legal protection to viable parts of businesses, allowing debtors to negotiate restructuring agreements with their creditors (OECD et al., 2019[12]). As also highlighted by the European Commission’s recommendation from March 2014, transparent and well‑defined legislation translates into efficient bankruptcy proceedings, creating less of a burden on the judiciary system and leading to a higher number of reorganisations instead of filed bankruptcies (European Commission, 2014[1]).

The WBT economies have well-established legal frameworks for survival and bankruptcy procedure regulations (Table 2.3). Future progress will depend on the streamlining of reorganisation and liquidation procedures. Overall, each economy’s performance is comparable in this assessment, with few disparities across the region.

Table 2.3. Scores for Sub-dimension 2: Survival and bankruptcy procedures

|

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Design and implementation |

3.80 |

4.00 |

2.70 |

3.30 |

3.00 |

3.50 |

3.62 |

3.42 |

|

Performance and monitoring and evaluation |

2.40 |

3.50 |

2.30 |

3.40 |

3.70 |

3.80 |

3.82 |

3.27 |

|

Weighted average |

3.24 |

3.80 |

2.54 |

3.36 |

3.28 |

3.62 |

3.74 |

3.37 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

While insolvency regimes are slowly improving, training to familiarise officials with legal reforms remains scarce

An efficiently designed insolvency regime is vital for facilitating the orderly exit of failing firms from the business environment. Ideally, an insolvency regime would prevent hasty and inefficient practices by creditors rushing to collect on individual claims that could result in lower recovered assets. Optimal insolvency policies, which equally rely on enforcement quality and judicial efficiency, should encourage debtors to address financial difficulties early on. Aspects of well-organised insolvency agreements include clear triggers to initiate insolvency proceedings, fair and strategic liquidation options that prioritise rehabilitation options for viable firms, and the inclusion of personal insolvency regimes in cases of merged personal and corporate assets (McGowan and Andrews, 2018[13]) (Box 2.3).

Box 2.3. OECD good practices on insolvency regime design

Just as a well-designed insolvency regime can positively impact the overall business environment, it can equally have adverse effects on productivity growth if poorly constructed due to high personal costs, length of discharging, low exemptions for small and medium-sized enterprises, and absence of preventative mechanisms. Although there is no consensus on the optimal design of insolvency regimes due to differing institutional settings between countries, policies should be designed to encourage early action to mitigate financial difficulties by debtors and increase the likelihood of restructuring over bankruptcy. Core features of a well-designed insolvency regime may include:

A clear trigger to initiate insolvency proceedings at the early stages of financial distress by either the debtor or creditors, thus enhancing the chances of restructuring instead of bankruptcy.

Both the option of efficient liquidation procedures and fair opportunities for rehabilitation of viable enterprises to strategically assess whether firm value is maximised by liquidation or restructuring. The option to restructure viable firms should be accompanied by mechanisms that can override dissenting parties in reorganisation proceedings that prevent progress when time is of the essence. Liquidation proceedings should facilitate a flexible and speedy exit of non‑viable firms to maximise value for all parties and preserve the overall business ecosystem.

A design that discourages malicious behaviour by creditors and debtors whereby parties can threaten to force an inefficient result in negotiations, force strategic defaults to obtain debt relief or transfer assets prior to insolvency to distinguish honest from fraudulent entrepreneurs.

In cases where personal and corporate insolvency are tied, efficient personal insolvency regimes take both the debtors’ prospects and incentives to benefit from post-insolvency second‑chance regimes into account.

Source: McGowan and Andrews (2018[13]).

All WBT economies have formal bankruptcy reorganisation and liquidation procedures in place, with some economies having introduced additional reorganisation procedures for SMEs since the previous assessment. Overall, bankruptcy reorganisation plans in the WBT region can be proposed by the debtor, some creditors or bankruptcy administrators, allowing for the submission of multiple, competing reorganisation plans. However, none of the economies has clear rules for selecting the most beneficial plan for all creditors in the case of multiple options.

The prevalence of hybrid insolvency regimes in the region, which combines judicial control in formal proceedings with out-of-court procedures, has also increased in recent years. Several economies, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia, have introduced hybrid pre-insolvency restructuring procedures. Both Serbia and Turkey have implemented hybrid schemes, with Serbia using a pre-packaged hybrid bankruptcy reorganisation procedure and Turkey introducing a hybrid preventive concordat restructuring agreement.

Since the previous assessment, all WBT economies, except Kosovo, have made a number of amendments to their insolvency legal frameworks. The most significant amendment was made in Bosnia and Herzegovina, whereby the Brcko District abolished its Bankruptcy Law in 2019 and introduced a new insolvency regime that is fully harmonised with Republika Srpska. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina synchronised its legislation with the Brcko District and Republika Srpska by introducing a new pre-insolvency restructuring and an electronic insolvency register. Meanwhile, North Macedonia prepared a new draft Bankruptcy Law in September 2021; however, it had not yet been submitted for parliamentary vote at the time of writing.

Table 2.4 summarises the amendments made in the region’s insolvency frameworks since 2019 and the foreseen additions, which were not yet implemented at the time of writing. However, it should be noted that following the changes in their regulatory frameworks, none of the economies provided formal training to ensure greater professional standards and high-quality services to the implementation bodies, such as the bankruptcy administrators, bankruptcy judges, appraisers and creditors’ associations.

Table 2.4. An overview of insolvency laws adopted or amended in the Western Balkans and Turkey since 2019

|

Economy |

Date |

Main changes |

Future foreseen addition |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

2021 |

Introduced new sub-law regulation (DCM65) on accelerated extrajudicial reorganisation agreements. |

Improved extrajudicial reorganisation agreements. |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

2019 (Brčko) |

Introduced a new Bankruptcy Law, featuring regular reorganisation and liquidation and pre-insolvency reorganisation. |

|

|

2021 (FBiH) |

Introduced a new section in the Bankruptcy Law on pre‑insolvency reorganisation and amendments to harmonise its regulation with Republika Srpska and Brčko. |

||

|

2021 (RS) |

Introduced a promotion programme of second chance for failed entrepreneurs and small and medium‑sized enterprises. |

||

|

Montenegro |

2019 |

The out-of-court Law on Consensual Financial Restructuring of Debts was revoked. |

|

|

2020 |

The new Law on Alternative Dispute Resolution (or Mediation Law) was introduced to support bankruptcy disputes. |

||

|

2021 |

Multiple amendments of the Bankruptcy Law were introduced, including the appointment of bankruptcy administrators, changes in the structure of the Board of Creditors, changes in insolvency test criteria, the registration of a bankruptcy estate as a legal entity, etc. |

||

|

North Macedonia |

2022 |

The proposal for the new Bankruptcy Law planned to be sent to the parliament for ratification includes new pre-insolvency proceedings, the introduction of an early warning system and many improvements to the current law. |

|

|

Serbia |

2022 |

Proposals for amendments to the Law on the Bankruptcy Supervision Agency, which define and establish qualifications for licensing of general and special administrators and criteria for delicensing, introduces a new electronic portal and the possibility for sale of assets through e‑auctions. The amendments to the Law on Bankruptcy include expedited submission of claims in 60 days instead of the current 120-day period, release of secured property to secured creditors if they are not the subject of reorganisation and other improvements. Both laws are under parliamentary discussion. |

|

|

Turkey |

2019 |

Introduction of the extrajudicial financial restructurings under Provisional Act 32 and the Banking Law. |

|

|

2020 |

Multiple amendments to the Bankruptcy Law on foreclosure liens, precautionary attachment decisions, etc. |

||

|

2021 |

Multiple amendments to the Bankruptcy Law concerning the sale of assets, the release of property not subject to concordat for sale, the continuation of contracts, property important for the continuation of the business, failure of the concordat and conversion to ordinary liquidation, etc. |

Note: FBiH: Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina; RS: Republika Srpska.

Streamlining liquidation processes are nascent in the WBT region

Digitalising the liquidation process can enhance transparency; save time and lower the costs of lengthy liquidation; anticipate potential conflicts between the creditors’ committee; and protect creditors’ rights as claims are recovered from the best market price reached at a competitive bidding procedure (OECD et al., 2019[12]). The digitalisation of liquidation processes in the region is generally underdeveloped, with a relatively low number of electronic services for liquidation processes compared to OECD member countries. However, North Macedonia stands out as a top performer in this regard, having substantially simplified its liquidation process by digitalising the sale of assets through e-auctions and automated distributions if there are no appeals from creditors (Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. The digitalisation of bankruptcy liquidation procedures in North Macedonia

The 2015 amendment of the Insolvency Act in North Macedonia introduced the option of e‑auction sales of assets from bankruptcy estates. Following seven years of implementation of e‑auction sales, evidence shows that the amount of time taken by bankruptcy liquidation procedures have decreased, reducing the procedure costs and creditors’ claims recovery at best market rates. The main sale principles are defined in Articles 98‑100 and Articles 189‑196 as follows:

The sale of the assets from the bankruptcy is done through e‑auctions with public bidding.

Parties interested in participating in e-auctions are required to pay a 10% bond/deposit of the book value of the asset. They then receive a participant ID with which to bid. The ID is anonymous.

The e-auction starts at a previously announced time and finishes 30 minutes later. All participants are automatically and electronically informed of the results of the auction.

Two additional e-auction rounds can take place for any unsold assets. The process must be completed within 90 days of the decision on the sale of assets from the bankruptcy estate.

The parties in the e-auctions have the right of appeal, which is resolved by a bankruptcy judge within three days of filing the appeal in court and is final.

The shares of publicly traded companies from the estate are sold on the stock exchange.

The initial price of an asset for bidding is not announced, and the auction starts from a price of zero.

A proposal for the partial distribution of proceeds from the sale of assets may be submitted within eight days, upon completion of the e-sale, to the Board of Creditors to approve the costs of the procedure and distribution to creditors.

There is an option for appeal on advance partial e-auctions and on final distribution to a bankruptcy judge, which is resolved by the judge within three days of filing the appeal in court and is final.

Distribution of proceeds takes place within eight days upon announcement of the final distribution plan.

Unsold assets are distributed in-kind to creditors.

Source: SCBL Project (2017[14]).

In 2021, Turkey introduced its e-auction system for liquidation proceedings via the National Judiciary Informatics System. Through this structure, both debtors and creditors can initiate the process of selling assets. However, some shortcomings, such as the lack of obligation to seek debtors’ consent to grant sales authorisations, have yet to be addressed. In addition, the appraisal costs of individual sales requests could potentially increase the length and the cost of bankruptcy and insolvency proceedings.

Simplified bankruptcy reorganisation and liquidation procedures have yet to be introduced

Simplified bankruptcy reorganisation and liquidation procedures aim to assist micro and small companies that may not have substantial assets, as the standard debt restructuring or liquidation procedure may be too costly to be practical. Ideally, a pre-packaged arrangement should be agreed upon between the debtor and creditors that requires fewer administrative steps and a lower approval threshold, unlike a traditional scheme, where the debtor should call the creditors board to negotiate and reach an agreement with the majority.

The bankruptcy and liquidation procedures in the WBT region are generally complex and difficult for small enterprises to navigate. With the exception of Kosovo and North Macedonia, WBT economies’ current legal frameworks are designed for medium‑sized and large enterprises, which have more administrative capacities than small firms.

For Kosovo and North Macedonia, expedited proceedings for micro and small enterprises are permissible under their current legislative frameworks. North Macedonia offers an accelerated out-of-court settlement procedure for “small value” enterprises with bankruptcy assets amounts up to MKD 1 million (approximately EUR 16 200) and fewer than ten employees. However, this scheme only removes a small portion of the overall process in which the Board of Creditors’ authorisation is required for liquidation, limiting the general impact of this accelerated track. Meanwhile, the Insolvency Law of Kosovo extends the option for expedited reorganisation to SMEs with an annual turnover of up to EUR 1 million or fewer than 25 employees on a voluntary basis. Under Kosovo’s framework, the court holds an accelerated hearing to determine if the debtor’s pre-filing solicitation of votes discloses all the required information and whether voting conditions were met, common impediments that typically prolong the process.

Monitoring and evaluation of bankruptcy proceedings could be improved in the region

Monitoring and evaluation of insolvency regimes is crucial for assessing the overall health of economy-specific and regional business environments. Well-developed and reliable indicators to monitor insolvency proceedings, such as the treatment of failed entrepreneurs, prevention and streamlining techniques, restructuring tools, and quantitative markers, can help support informed policy making that helps streamline access to swift and effective insolvency proceedings for small enterprises.

Monitoring and evaluation systems of bankruptcy proceedings in the WBT region are primarily based on the performance of the judiciary system. The overall level of data collection varies widely among the economies. In Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia, data are collected on the number of opened and closed cases by the regional court of jurisdiction. In contrast, data in Turkey are only collected at the national level.

However, in most cases, the monitoring and evaluation of collected data remains very weak, as most WBT economies do not collect information, such as the cost of the bankruptcy proceeding as a percentage of the bankruptcy estate, the number of backlog court cases related to bankruptcy or creditors’ recovery. Moreover, none of the economies tracks the final status of the reorganisation plans, eliminating the possibility of assessing the efficiency of implemented legal frameworks.

Nevertheless, some efforts have been made to collect a handful of data indicators related to insolvency procedures in a few economies. Serbia and Turkey monitor the size of court case backlogs annually, while Albania and Turkey also measure the length of bankruptcy procedures.

The way forward for survival and bankruptcy procedures

Streamline liquidation processes by introducing digital tools. Digitalising the liquidation process would enhance transparency, save time and cost of the currently lengthy liquidation procedures, anticipate potential conflicts within the creditors’ committee, and protect creditors’ rights as claims are recovered from the best market price reached through a competitive bidding procedure. This could be achieved by introducing e-auctions and automatic e-distributions mechanisms. Moreover, information about insolvency procedures should be publicly available and contain information such as rules on data protection and privacy.

Introduce simplified bankruptcy proceedings for SMEs. As SMEs have smaller scales of business and simpler operations, short-tracking proceedings, for example, for SMEs with a maximum debt set at a given threshold, determined based on the average size of an economy’s micro and small-sized firms, at the time of filing for bankruptcy would ease the cumbersome and expensive administrative burdens for small companies. Additionally, only debtors should be able to file for bankruptcy reorganisations, and restructuring plans should be simplified to reflect the fewer resources of small businesses, e.g. there is no need for creditors’ committees (see Box 2.5for a good practice example). Simplified and fast-track procedures are particularly relevant in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic. They allow for quicker reintegration of businesses into the economy and avoid potential increases in unemployment.

Improve monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Policy making is effective when it is well‑informed and evidence-based, which requires appropriate monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. As highlighted above, WBT economies collect very little bankruptcy-related data, which does not allow for the effective and regular monitoring of the implementation of insolvency measures. Therefore, all economies should predefine a set of key performance indicators to enable monitoring and evaluation of the progress made to better determine required changes to the introduced measures and legal frameworks. For more information on data that WBT governments could consider collecting in this area, please see Annex C. Improved co-ordination between different public institutions is also recommended. It may lead to an increase in the number of relevant indicators collected and ensure an improved evaluation of the impact of insolvency policies.

Maintain the administrative capacities of the bodies implementing the insolvency framework to harmonise legislative changes among the WBT economies. Despite changes to their insolvency regimes, none of the economies provided training to bankruptcy administrators, bankruptcy judges, appraisers or creditors’ associations. Providing training would ensure that implementation bodies offer high-quality services and would help to improve administrative capacity.

Box 2.5. US Bankruptcy Code Subchapter V: Small Business Reorganisation

In 2019, the United States adopted a new subchapter of its Bankruptcy Law, which regulates the Small Business Reorganisation Act (SBRA), where “small-business debtor” is broadly defined as a “person engaged in commercial or business activities that has aggregated non-contingent liquidated secured and unsecured debts as of the date of the filing of the petition in an amount not more than USD 2 725 620; exclusion from this rule is available for businesses with aggregated debt of up to USD 7.5 million due to COVID‑19 Interim measures.”

The new legislation comes at the time of COVID-19 to strike a balance between formal Bankruptcy Liquidation (Chapter 7) and Bankruptcy Reorganisation (Chapter 11) proceedings for small business debtors. The act lowers costs and streamlines the plan confirmation process to better enable small businesses to survive bankruptcy and retain control of their operations. The US SBRA significantly simplifies the court proceeding and places a maximum of three or five years of disposable income to be paid under the confirmed plan throughout the life of the plan’s implementation. Initial statistics show that two‑thirds of all filed Chapter 11 formal court reorganisations were transferred to SBRA filings. Initial data confirm that 80% of all filed plans are confirmed in 120 days.

Main principles

No one but the debtor engaged in a non-publicly traded business activity (except if it complies with the aggregated debt level threshold defined in the law) can file a petition for small business reorganisation.

No US trustee quarterly fees are paid.

No exclusions in the proceeding: The debtor must file a plan within 90 days.

No creditor committees: Creditor committees will not be appointed in Subchapter V cases unless ordered by the Bankruptcy Court for cause.

No competing plans: The debtor has the exclusive right to file a plan, which must be filed within 90 days from the date of the bankruptcy petition unless extended for cause.

No absolute priority: The debtor need not comply with the “absolute priority rule”, which generally prohibits the owners from retaining equity unless all creditors are paid in full. A plan may be confirmed over the objection of one or more impaired classes of creditors. To obtain confirmation through a “cram-down”,1 a debtor need only demonstrate that the plan is fair and equitable, does not unfairly discriminate, and provides for the debtor’s contribution of all of its projected disposable income.

No disclosure statements: Disclosure statements are not required, although the plan must include information typically found in a disclosure statement, including a summary of historical operations, liquidation analysis and projections demonstrating an ability to make payments under the plan.

No enforcement is allowed against the implementation of a cram-down or a non‑consensual confirmed plan, until the court case file is closed (between three and five years from the plan confirmation).

The debtor is in possession of its business, and the bankruptcy administrator only assists in assessing the viability of the business and facilitates the development of a consensual plan to reorganise the business.

The appointed bankruptcy administrators have strong business qualifications and include lawyers, restructuring consultants and financial advisors with diverse backgrounds in such areas as business, law, accounting, turnaround management and mediation.

Deferral of administrative expense payments: Administrative expenses that typically must be paid upon the effective date of the plan may be deferred over the life of the plan for up to five years.

Discharge provisions: If the plan is confirmed with the consent of all affected creditors, the debtor will receive a discharge of its debts upon plan confirmation. For plans confirmed through “cram-down”, the discharge will take effect when all of the payments called for under the plan are made.

Residential mortgage modification: The SBRA authorises a small business debtor to modify a residential real estate mortgage to the extent that proceeds from the loan were used to fund the business, a form of relief previously unavailable under the Bankruptcy Code.

1. A cram-down is the imposition of a bankruptcy reorganisation plan by a court despite any objections by certain classes of creditors. A cram‑down involves the debtor changing the terms of a contract with a creditor with the help of the court. This provision reduces the amount owed to the creditor to reflect the fair market value of the collateral that was used to secure the original debt.

Source: Bonapfel (2021[15]).

Promoting second chance (Sub-dimension 2.3)

Economies are increasingly recognising the importance of giving a second chance to entrepreneurs who have experienced bankruptcy. This is vital for stimulating economic growth, creating jobs and improving the business environment, especially in the aftermath of the COVID‑19 pandemic. However, due to the stigma associated with failure and the difficulty distinguishing honest entrepreneurs from fraudulent ones, giving businesses a second chance is not always easy.

A second-chance policy allows failed honest entrepreneurs to start up fresh businesses again. Promoting second chance through public awareness campaigns for previously bankrupt entrepreneurs allows for both their quick reintegration into society and the change of cultural stigmatisation of failure into new opportunity. Studies show that entrepreneurs at risk or who have failed and are willing to make a fresh start based on lessons learnt can bring more benefits to an economy than start-ups. Such benefits can include additional new job openings and growth (Startup Genome, 2021[16]).

In this context, the discharge of debt and personal responsibility and liability is extremely important for failed entrepreneurs as it allows them to reintegrate into the economy. As discharge duration can be lengthy and imposed sanctions for failed entrepreneurs are relatively strict, bankruptcy can effectively prevent these companies from making a new start. Even when this is not the case, tailor-made support to restart a business is often limited.

As in the previous assessment, second-chance promotion remains underdeveloped in the region (Table 2.5). Although second-chance policies form part of the SME-related strategic documents in almost all WBT economies, no concrete support measures in this context have been envisaged. However, Bosnia and Herzegovina is slightly ahead of its regional peers, thanks to its project-based support for second chance, provided through business advisory services in Republika Srpska.

Table 2.5. Scores for Sub-dimension 2.3: Promoting second chance

|

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Promoting second chance |

2.00 |

2.20 |

1.50 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

2.00 |

1.96 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Debt discharge procedures as the key to granting second chance are part of the insolvency frameworks in the region

Debt discharge procedures relieve debtors from remaining debt in bankruptcy procedures, including personal liabilities. In reorganisation procedures, debt discharge is granted by court decision following confirmation of the restructuring plan, which explicitly states that only the debt foreseen in the proposal approved by creditors has to be paid. In bankruptcy liquidation, on the other hand, the debt discharge depends on whether the liquidation is caused by the negligence of the debtor’s management or an ordinary or fraudulent bankruptcy.

All WBT economies have automatic debt discharge subject to confirmation of the restructuring plan under the bankruptcy reorganisation procedures. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, and Turkey have formal discharge procedures for entrepreneurs. In Serbia, the law only regulates discharge for legal entities and does not provide any reinstatement of rights for natural persons upon liquidation. Similarly, in North Macedonia, there is no discharge from debt except for natural persons registered as a legal person or an incorporated (one-person) company. However, this procedure should be initiated separately upon the closing of bankruptcy liquidation procedures by the court.

Second-chance programmes are largely non-existent in WBT economies

The negative effects of failure on honest entrepreneurs, such as sanctions or the loss of civic rights, should be limited in order to provide them with the opportunity for a second chance at building a business. Thus, legal frameworks should be formulated in a way that avoids barriers to the regeneration of businesses and endows second-time entrepreneurs with services to avoid repeating mistakes that previously resulted in failure. Governments should also be active in supporting unsuccessful entrepreneurs through second‑chance schemes as the cultural stigma of business failure may have negative impacts, for example when failed entrepreneurs apply for bank loans.

Like in the previous assessment, second-chance promotion is underdeveloped in the region. However, on a positive note, WBT economies do not envisage sanctions or civic consequences for failed honest entrepreneurs following bankruptcy, which lifts barriers to entry for entrepreneurs returning to the economy.

None of the WBT economies promotes second-chance programmes among entrepreneurs at risk of failing or those who have already failed. Public awareness campaigns and action plans on second-chance opportunities for failed businesses are also lacking. On a positive note, Republika Srpska has been supporting second-chance opportunities through business advisory services as part of the DanubeChance2.0 EU Interreg project. In particular, it established an annual budget line for its second‑chance programme of BAM 100 000 (around EUR 50 000). While almost all of the remaining economies in the region highlight the importance of second-chance policies in their SME strategies, none of them provide details on concrete plans/measures to be implemented.

The way forward for promoting second chance

Promote second chance to honest entrepreneurs. All WBT economies should promote second chance as an option to honest entrepreneurs to have a fresh start and to reduce the cultural stigma related to business failure. Table 2.6 provides an overview of potential policy options that economies could implement at different stages of their bankruptcy processes.

Introduce amendments to legislation to support second chance. The WBT economies should adjust their legislation to provide second-chance support for entrepreneurs at risk of failing or who have already failed. Potential options include: 1) free business advisory services; and 2) interest‑free financial support in the form of short-term loans to finance ongoing operations.

Table 2.6. Second-chance policy support for entrepreneurs at risk or who have failed

|

Insolvency phase |

Second-chance programme |

Legal intervention |

|---|---|---|

|

1. Early warning |

Permanent business advisory and mentoring support services for entrepreneurs at risk of financial distress |

Amendment of bankruptcy law providing for access of enterprises to early warning systems and regulation on the provision of early warning systems. Allocation of funds for financing services. |

|

2. Out-of-court restructuring |

Permanent business advisory, turnaround restructuring and financing services for entrepreneurs at risk of financial distress |

Law on out-of-court restructuring arrangement regulating automatic stay and voting of creditors. Allocation of funds for financing restructurings based on recycling financial means or credit guarantee schemes. |

|

3. Hybrid pre-insolvency restructuring or formal bankruptcy reorganisation |

Insolvency restructuring, permanent business advisory and financing services for entrepreneurs at risk of imminent insolvency |

Allocation of funds for financing restructurings based on recycling financial means or credit guarantee schemes. |

|

4. Bankruptcy liquidation |

Debt discharge, reinstatement of rights, legal services |

Amendments of bankruptcy law allowing for debt discharge and reinstatement of rights. |

Source: Commission of the European Communities (2007[17]).

References

[7] Allen & Overy (2020), “WHOA: The new Dutch scheme”, web page, https://www.allenovery.com/en-gb/global/news-and-insights/publications/whoa--the-new-dutch-scheme.

[15] Bonapfel, P. (2021), A Guide to the Small Business Reorganization Act of 2019, https://www.ganb.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/sbra_guide_pwb.pdf.

[9] CMS Germany (2021), The Stabilisation and Restructuring Framework from the Perspective of Financing Creditors, CMS Germany, https://cms.law/en/media/local/cms-hs/files/publications/publications/starug-financing-creditors-04-2021.

[17] Commission of the European Communities (2007), Overcoming the Stigma of Business Failure – For a Second Chance Policy: Implementing the Lisbon Partnership for Growth and Jobs, Commission of the European Communities, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2007:0584:FIN:en:PDF.

[6] Dutch Experian (2021), “SMEs in the Netherlands risk delayed bankruptcies and declining credit scores as COVID-19 situation continues”, web page, https://www.experian.nl/over-experian/2021/02/18/smes-in-the-netherlands-risk-delayed-bankruptcies-and-declining-credit-scores-as-covid-19-situation-continues.

[1] European Commission (2014), Commission Recommendation of 12 March 2014 on a New Approach to Business Failure and Insolvency, Official Journal of the European Union, L 74/65, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014H0135&from=EN.

[4] European Union (2019), Directive (EU) 2019/1023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on Preventive Restructuring Frameworks, on Discharge of Debt and Disqualifications, and on Measures to Increase the Efficiency of Procedures Concerning Restructuring, Official Journal of the European Union, L 172/18, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32019L1023.

[3] European Union (2015), Regulation (EU) 2015/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 2015 on Insolvency Proceedings, Official Journal of the European Union, L 141/19, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32015R0848.

[11] IMF (2021), Restructuring and Insolvency in Europe: Policy Options in the Implementation of the EU Directive, International Monetary Fund, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2021/152/001.2021.issue-152-en.xml.

[10] IMF (1999), Orderly & Effective Insolvency Procedures, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/orderly.

[5] Kuhanathan, A. and A. Boata (2021), European SMEs: 7-15% at Risk of Insolvency in the Next Four Years, Allianz SE, https://www.allianz.com/en/economic_research/publications/specials_fmo/2021_09_01_EuropeanSMEs.html.

[13] McGowan, M. and D. Andrews (2018), “Design of insolvency regimes across countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1504, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d44dc56f-en.

[12] OECD et al. (2019), SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2019: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/g2g9fa9a-en.

[14] SCBL Project (2017), Compilation of Laws and Regulations: Bankruptcy and Liquidation, https://economy.gov.mk/Upload/Editor_Upload/Projekti/ENG%20-cocompilations%20of%20laws.pdf.

[16] Startup Genome (2021), The Global Startup Ecosystem Report: Agtech & New Food Edition, Startup Genome, https://startupgenome.com.

[8] UK Government (2020), Corporate Insolvency and Governance Act 2020, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2020/12/contents/enacted.

[2] World Bank (2019), “Resolving insolvency”, Doing Business, https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/resolving-insolvency.

Note

← 1. This designation is without prejudice to positions on status and is in line with United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244/99 and the Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice on Kosovo’s declaration of independence.