This chapter assesses the quality infrastructure systems and procedures required in the Western Balkans and Turkey to facilitate SMEs’ access to the EU Single Market. It starts by outlining the assessment framework, then presents an analysis of Dimension 7’s three sub-dimensions: 1) overall co‑ordination and general measures, which assesses the strategic documents and institutional framework for quality infrastructure co‑ordination; 2) harmonisation with the EU acquis, which analyses the capacities of quality infrastructure institutions as well as their alignment with international and European rules for technical regulations, standardisation, accreditation, metrology, conformity assessment and market surveillance; and 3) SMEs’ access to standards, which explores government initiatives to enhance and support access. Each sub-dimension makes specific recommendations for increasing the capacity and efficiency of quality infrastructure systems in the Western Balkans and Turkey.

SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2022

8. Standards and technical regulations (Dimension 7) in the Western Balkans and Turkey

Abstract

Key findings

Quality infrastructure (QI) activities are centrally co-ordinated in most economies in the Western Balkans and Turkey, but often lack updated strategies or action plans. As quality infrastructure requires the co‑operation of various institutions and ministries, it is important to have a joint strategy that covers the different dimensions of quality infrastructure, or at least to harmonise the strategies for the different institutions involved.

Regional co-operation on quality infrastructure happens at various levels and fora, but should be further deepened. There is exchange on QI within the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) as well as in regional QI programmes funded by international development partners, but deeper forms of co‑operation, such as mutual recognition of technical regulations, which could further strengthen intra-regional trade within CEFTA, are not yet complete.

Harmonisation of technical regulations and quality infrastructure legislation is continuing, albeit slowly. Western Balkans and Turkey (WBT) economies continue to harmonise legislation as foreseen in their domestic integration plans, but often legislation has not yet been harmonised with the more recent acquis, as evaluation of technical regulations and other legislation is carried out primarily on demand rather than following periodic reviews.

Governments continue to expand the international recognition of their quality infrastructure by the relevant European institutions. Recognition of the domestic accreditation and metrology institutes continues to grow through the expanded scope of the European co-operation for Accreditation (EA) Multilateral Agreement (MLA) for some economies. The share of adopted European standards also continues to rise, particularly in economies that had lower adoption rates. Kosovo and Montenegro also initiated application processes for membership in different European QI associations.

Financial support for SMEs has expanded, but there are few efforts to foster SMEs’ participation in standards development. An array of financial support schemes exist for SMEs, which also cover costs related to implementing standards. However, there are still no specific incentives in place to foster SMEs’ participation in standards development.

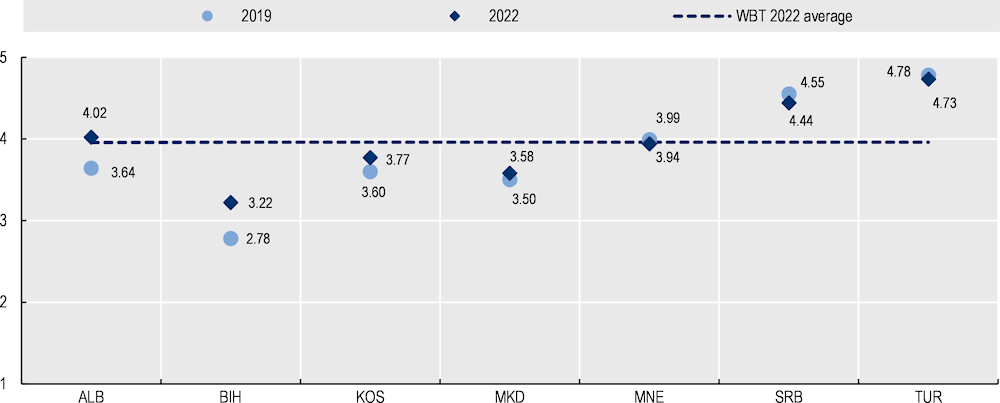

Comparison with the 2019 assessment scores

Overall, the regional average score in this dimension improved from 3.83 in 2019 to 3.96 in 2022 (Figure 8.1). Progress has been made in all three sub-dimensions, despite a slightly more comprehensive assessment. Convergence in the performance of the QI systems can be observed, as economies that had lower scores in the previous cycle made the greatest improvements. While Serbia and Turkey still have the most comprehensive QI systems, other WBT economies are increasingly meeting international requirements, continue to align their legislation with the acquis, perform awareness-raising activities, and provide technical and financial support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Figure 8.1. Overall scores for Dimension 7 (2019 and 2022)

Notes: WBT: Western Balkans and Turkey. Despite the introduction of questions and expanded questions to better gauge the actual state of play and monitor new trends in respective policy areas, scores for 2022 remain largely comparable to 2019. To have a detailed overview of policy changes and compare performance over time, the reader should focus on the narrative parts of the report. See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations

Table 8.1 summarises progress made in implementing the key recommendations for this dimension since the previous assessment. While there has been substantial progress in offering online participation in standard committee meetings and financial support programmes that cover standard-related costs for SMEs, progress on most of the other recommendations has been limited. Education on standards remains mostly limited to industry, and co-operation with universities is sporadic, without a broader strategic approach to incorporating education on standards or QI into education systems. There are signs of increasing regional co-operation on QI within CEFTA, but the recognition of technical regulations in priority sectors, one of the objectives for 2021, has not been achieved.

Table 8.1. Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations for Dimension 7 in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

Regional 2019 recommendation |

SME Policy Index 2022 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Main developments during the assessment period |

Regional progress status |

|

|

Establish a single source of tailored information for SMEs |

Most economies still do not have a single source of tailored information for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the form of single web portals or SME trade help desks. Serbia’s TEHNIS portal remains the only website that summarises quality infrastructure (QI) and export-relevant information in a user-friendly way. Albania and Turkey also have export help desks, but they lack specific (regulatory) information about QI. |

Limited |

|

Explore regional collaboration and consider taking steps to establish common use of quality infrastructure at the regional level |

Regional exchange on QI occurred as part of the German‑funded project “South‑eastern European Quality Infrastructure Fund”, which took place between 2018 and 2022 and included QI institutions from all six Western Balkan economies. In addition, CEFTA initiated a discussion on the mutual recognition of technical regulations in 2021; the discussion is ongoing. Turkey’s collaboration with the Western Balkan economies remains restricted to bilateral co‑operation, for example through accreditations undertaken by the Turkish accreditation body TURKAK. |

Moderate |

|

Scale up the revenue‑earning services of national standards bodies |

Most national standards bodies are still highly reliant on public budgets, with alternative incomes making up at most 10-15%. The Institute for Standardisation of Bosnia and Herzegovina introduced a subscription-based online reading service. The Institute for Standardisation of Serbia and the Turkish Standards Institution create alternative revenues through conformity assessment services, which may, however, lead to a conflict of interest with their standard-setting function. |

Limited |

|

Include standardisation in national secondary and tertiary curricula |

There has been very little progress on this recommendation. Most national standards bodies (NSBs) do not follow a systematic approach with respect to education and activities remain restricted to short-term trainings for industry. In Montenegro, staff from the standards body offer a course at a public university. The Institute for Standardization of Bosnia and Herzegovina is preparing a service so that students can access standards free of charge. |

Limited |

|

Complement the enforcement of regulation with measures to increase transparency and compliance |

Most market surveillance authorities publish their annual work plans, annual reports and dangerous product notifications (both national and the Rapid Alert Information System [RAPEX]). However, guidance notes to enhance self-compliance activities, as proposed in this recommendation, have not been introduced. |

Limited |

|

Disseminate successful case studies that highlight the benefits of standardisation in a local context |

No progress has been made on this recommendation. NSBs in the region are not using case studies to raise awareness. Brochures on websites are often outdated or are in English from CEN-CENELEC or ISO. |

No progress |

|

Allow SMEs to participate in standards development through digital tools or by covering their travelling costs |

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all NSBs moved their technical committee meetings on line. While there were no specific measures targeting SMEs, this lowered barriers to participation. No NSB in the region provides travel cost allowances. |

Strong |

|

Scale-up financial support programmes to help SMEs implement standards |

With the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, every economy in the region has at least one programme that offers financial support to SMEs to implement standards. The number of firms supported by these programmes has also increased in most economies. |

Strong |

Introduction

Technical regulations and standards serve to assure key policy objectives such as environmental and health protection. At the same time, they assure that goods and services traded in the global market adhere to certain minimum quality standards as well as interoperability between goods from different markets, thereby removing trade barriers. Well-harmonised technical regulations and standards can facilitate cross‑border trade by reducing uncertainty and increasing trust among market participants.

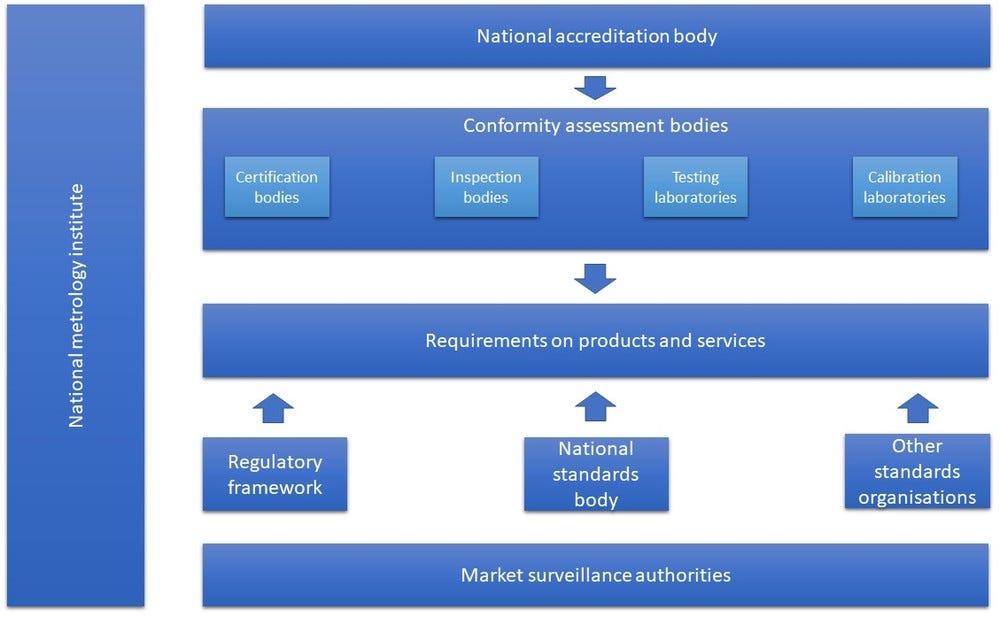

However, to assure that adopted regulations and standards are also implemented by firms, one needs an appropriate set of institutions to assess and confirm compliance. The combination of these institutions is referred to as the national QI system. One key institution is the national standards body, which is responsible for adopting and developing new standards. Once standards are adopted, compliance with them is verified by so‑called conformity assessment bodies. Through services such as certification, testing, inspection and calibration, these bodies evaluate and confirm compliance with the requirements specified in technical regulations and standards. Conformity assessment bodies must be sufficiently qualified and possess the required systems to assess firms’ conformity to the standards. The national accreditation body and the national metrology body (in calibration) are responsible for monitoring and controlling the competence of the assessment bodies. Finally, the system is complemented by market surveillance authorities, which are responsible for controlling products entering the economy and circulating in the market through inspection and removing dangerous and non‑conforming products if necessary. Figure 8.2 summarises the structure of a national QI system in which the interrelated elements build on one another to maximise impact.

Figure 8.2. A national quality infrastructure system

Against this background, WBT economies must create the necessary structures and fulfil their obligations with regard to the free movement of goods in their preparation for EU accession. When products are subject to different national regulations that are not mutually recognised or harmonised, their free movement across member states is hindered. Therefore, prior to EU accession, governments must ensure that they align their product regulations with the current acquis, transpose European standards into national regulations and repeal conflicting national standards.

Improvements in QI systems have the potential to further boost trade with the European Union as well as intra-regional trade in the WBT region. Although trade volumes have doubled over the past decade, reaching more than EUR 50 billion with the Western Balkans (European Commission, 2021[2]) and EUR 132 billion with Turkey (European Commission, 2021[3]), WBT economies’ openness to trade remains low given their size, level of development and geographic location (Sanfey and Milatovic, 2018[4]). In addition to improving trade with the European Union, adopting European QI standards can also help improve intra-regional trade, especially within the Western Balkans, where intra‑regional trade accounts for only 20% of total trade and has lost relative importance (Kaloyanchev and Kusen, 2018[5]).

Despite the great improvement in market access, SMEs in the WBT economies do not fully take advantage of the potential offered by the European Single Market. Reasons for this are the lack of information about the rules applied in the European Union, as well as insufficient language skills. For example, most WBT economies only translate the cover pages of adopted European standards, which makes it difficult for SMEs without English language skills to access this information. Another barrier are the costs of meeting the regulatory requirements.

In this context, SMEs in WBT economies must have access to reliable and efficient QI services that help them to ensure that their products are in line with EU standards and regulations and that also assist them if further efforts are required to assure this conformity. Moreover, given the globalisation of value chains, technical regulations and standards beyond the EU market are gaining in importance (Blind, Mangelsdorf and Pohlisch, 2018[6]). The ability of firms, sectors and economies to absorb, adapt and diffuse current technologies and participate in global value chains depends on investments in QI facilities and mechanisms (Doner, 2016[7]). Despite the high potential benefits, SMEs often do not have the expertise or capital to undertake these investments without external support. To reap these benefits, an entire network of interdependent national QI organisations and instruments must be created. This would be a system composed of public and private organisations with the appropriate legal and regulatory frameworks and practices needed to support and improve the quality, safety and environmental performance of goods, services and processes. When building this network, it will be extremely important to pay particular attention to the needs and challenges of SMEs (UNIDO, 2017[8]). Ultimately, a well-functioning QI system is a requirement not only for increasing and diversifying exports, but also for industrial upgrading and, ultimately, promoting sustainable economic growth (Swann, 2010[9]; Guasch et al., 2007[10]).

Assessment framework

Structure

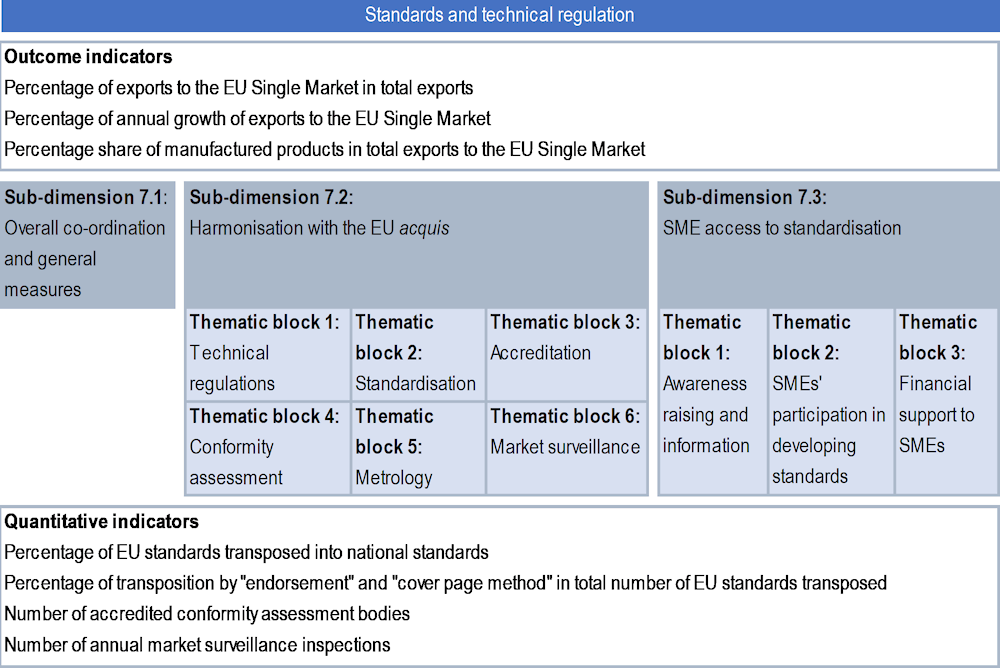

The overall objective of Dimension 7 is to analyse whether the economies have a well‑functioning QI system, how aligned it is with EU rules, and how governments are endeavouring to improve SMEs’ access to the EU Single Market.

The assessment framework for this dimension has three sub-dimensions:

Sub-dimension 7.1: Overall co-ordination and general measures looks at general policies and tools for overall policy co-ordination and strategic approaches to adopt and implement EU legislation. The assessment also evaluates if all relevant information on requirements for exporting to the European Union is accessible to SMEs.

Sub-dimension 7.2: Harmonisation with the EU acquis explores the national quality infrastructure systems by examining the main elements of their key pillars – technical regulations, standardisation, accreditation, metrology, conformity assessment and market surveillance – in six thematic blocks. More specifically, it analyses their institutional capacity, adoption and implementation of strategic documents, and integration into international structures. It also examines if the legislation and instruments are subject to regular monitoring and evaluation.

Sub-dimension 7.3: SMEs’ access to standardisation evaluates government efforts to increase SMEs’ awareness of standards, facilitate their participation in developing standards and support them in implementing standards.

Figure 8.3. Assessment framework for Dimension 7: Standards and technical regulations

Compared to the 2019 assessment, no changes were made to the number or weighting of the sub‑dimensions and thematic blocks. However, new questions were added to each of the sub-dimensions to reflect recent developments. The first set of new questions relates to plans and activities that were introduced by the different QI institutions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as remote inspections and online committee meetings as well as the introduction of contingency plans. The second set of questions relates to the introduction of digitalisation measures in the different institutions. Finally, an additional question about adaptations that were the result of evaluations was added to the six different QI pillars. Overall, these changes had only a minor impact on the scores, as the majority of the new questions did not enter the scoring framework. Nonetheless, since the additions were usually asking about more advanced functions and activities of the national QI system, it made the assessment slightly more comprehensive.

The main findings of the European Commission’s EU accession progress reports for the Western Balkans and Turkey are referred to throughout this chapter. In particular, progress made under Chapter 1 of the EU negotiations (free movement of goods) has been reflected in the analysis whenever relevant. Eurostat data were used to inform the trade performance section.

Analysis

Performance in EU trade

Exports to the European Union were chosen as an outcome indicator for this dimension, as export performance strongly correlates and partially also depends on the QI system and the alignment of technical regulations and standards in particular (Harmes-Liedtke and Oteiza Di Matteo, 2020[11]). Furthermore, one of the ultimate objectives of a QI system is harmonisation, which in turn lowers barriers to trade.

Trade is a key aspect of the integration of WBT economies into the European Union, and the European Union has gradually concluded bilateral free trade agreements with the Western Balkans and signed the Customs Union Agreement with Turkey.

The Western Balkan economies were granted autonomous trade preferences in 2000 (extended in 2020 until the end of 2025). The autonomous trade preferences allow unlimited and duty-free access for almost all Western Balkan exports to the European Union. Exceptions are wine, sugar, baby-beef and certain fishery products, which are subject to preferential tariff quotas. The main EU imports from the Western Balkans are machinery and equipment (24.9%), base metals (11.4%), and chemicals (10.0%) (European Commission, 2021[2]).

The major milestone for Turkey’s path towards closer EU trade ties was the conclusion of a Customs Union Agreement with the European Union in 1995. The agreement stipulated that Turkey must implement the acquis regarding the elimination of technical trade barriers. As a consequence, Turkey started to align its legislation and QI system relatively early, which may also partially explain why it has the most advanced QI system among all WBT economies today. In December 2016, the European Commission proposed adapting the Customs Union Agreement and extending it to areas such as services, government procurement and sustainable development. This recommendation was temporarily halted by the General Affairs Council on 26 June 2018. Discussions resumed in October 2020 after approval by the European Council, but no further progress has been made to date (European Parliament, 2020[12]).

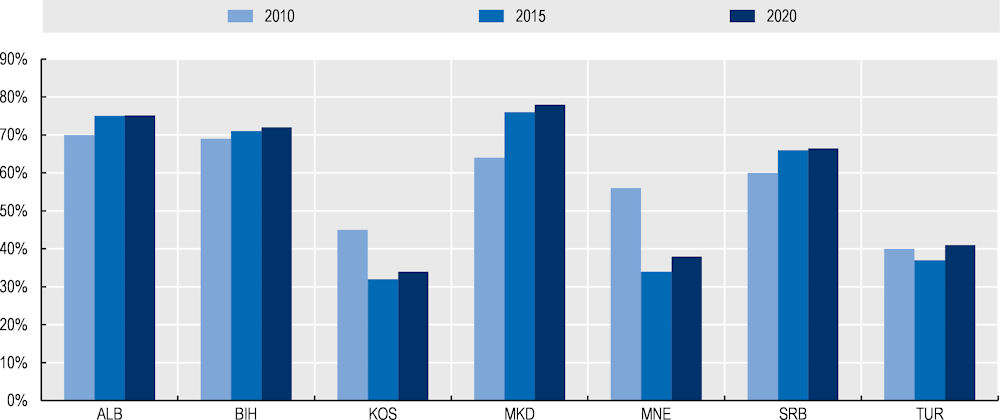

The European Union is the most important trading partner of each of the WBT economies, and four of the seven economies export more than 60% of their goods to the European Single Market (Figure 8.4). While the overall share of EU exports is lower in Kosovo and Montenegro, which also send a significant share of their exports to neighbouring CEFTA partner economies, the share of EU exports increased between 2015 and 2020 in six out of seven economies and remained stable in Albania. The European Union also remains Turkey’s largest trading partner, accounting for 41% of Turkish exports (Figure 8.4).

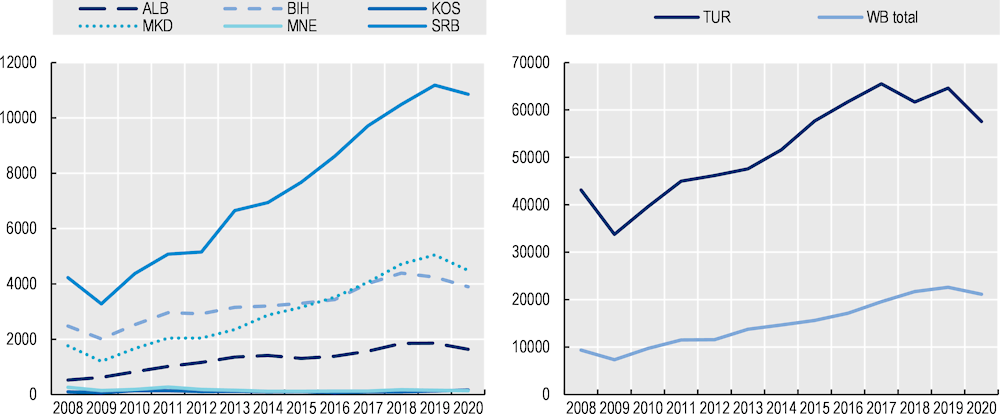

Exports from WBT economies to the European Union steadily increased from the financial crisis in 2008 to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. After some slower growth in the first half of the past decade, exports to the European Union grew very strongly between 2016 and 2018, with an average growth rate of 12.2% in the Western Balkans and 8.6% in Turkey (Figure 8.5). Export growth slowed significantly in 2019, then contracted in 2020. As can be observed in both panels of Figure 8.5, the 2020 decline in EU-destined exports was more pronounced in Turkey (‑10.9%) than in the Western Balkans (-6.4%). This trend can be attributed primarily to the slowdown in global trade due to COVID-19, as the share of European exports remained stable in all seven economies in 2020. In turn, this means that the slowdown in trade due to the pandemic did not affect EU-WBT trade disproportionally.

Trade with the European Union remains dominated by manufactured goods, which accounted for 80% of Western Balkan exports to the EU Single Market and 77% of imports in 2017 (Eurostat, 2020[13]). Since requirements for manufactured goods are more stringent than for other goods, the trade composition shows that standards and technical regulations have an above-average relevance for trade between the Western Balkans and the European Union, which also underlines the importance of facilitating SMEs’ access to relevant standards in the Western Balkan economies.

Figure 8.4. Share of EU exports in total exports (2010-2020)

Figure 8.5. Western Balkans’ and Turkey’s exports of goods to the European Union (2010-2020)

Recent studies show that despite the increase in trade over the past 20 years, there is still potential to further intensify trade flows between the WBT region and the European Union as well as to increase trade within the region itself (Kaloyanchev and Kusen, 2018[5]; Sanfey and Milatovic, 2018[4]). Greater alignment of the economies’ legal and institutional frameworks for QI with the acquis and targeted support for SMEs in complying with standards and technical regulations would help WBT governments to further increase trade volumes and diversify their exports by facilitating access for additional goods.

Overall co-ordination and general measures (Sub-dimension 7.1)

Quality infrastructure is a complex system that requires effective co-ordination of public as well as private institutions that participate in adopting as well as in implementing and controlling technical regulations and standards. Effective and efficient co-ordination of QI activities is important to assure that information is exchanged quickly between institutions and that market demands for regulation and standardisation are being met rapidly. Furthermore, information about QI needs to be provided to firms in a user-friendly way, which requires co-ordination at the subnational level to reach firms in all regions. Due to the inter-related pillars and the involvement of various institutions, it is important to have a designated body responsible for the co-ordination of quality infrastructure.

This section considers the extent to which the WBT economies have ensured the overall co-ordination of their QI systems. As in the previous assessment, Turkey and Serbia continue to be the best performers in this sub-dimension. However, all the other WBT economies have seen considerable improvements, which are also reflected in the higher WBT average.

Table 8.2. Scores for Sub-dimension 7.1: Overall co-ordination and general measures in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall co‑ordination and general measures |

3.89 |

3.77 |

4.00 |

3.00 |

3.33 |

4.33 |

5.00 |

3.90 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

All economies have a central co-ordinating body for quality infrastructure and legislative alignment is directed by national integration plans

Each of the WBT economies has a national plan for adopting the acquis, which serves as the key strategic document for regulatory alignment and contains QI-specific legislation in the chapter on the free movement of goods. However, the plans differ in their level of detail. While Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey provide all the laws and the planned adoption dates in their reports, other economies’ plans are less concrete. For example, Turkey has a concrete adoption plan that lists the related acquis, the related national legislation, the responsible institution, and the estimated date for implementation or adoption. Having such a structure improves the monitoring of the harmonisation process as well as accountability.

All WBT governments have a public body, usually a department within the Ministry of Economy, which is responsible for the co-ordination of QI activities. However, joint QI strategies that guide and monitor the activities across the different QI pillars are rare. So far, only Serbia has a joint QI strategy; the other economies operate with pillar-specific strategies in standardisation, accreditation and metrology. While this approach is also feasible, having a joint strategic document or action plan that specifies the co-operation between the different QI institutions can help to improve and monitor co-ordination.

Despite continuous growth in the number of EU-aligned regulations and applicable European standards, most economies do not have a centralised information portal that bundles information about technical regulations and conformity assessment procedures required for accessing the EU Single Market. Therefore, firms seeking this information need to collect it from various institutions and websites, which poses an information barrier, particularly for SMEs, which may not be particularly familiar with the European and national QI systems. While some economies have export help desks or export promotion agencies, they do not provide information about technical regulations, standards or conformity assessments. The exception is the Serbian Ministry of Economy’s Sector for Quality and Product Safety’s TEHNIS website, which presents technical regulations categorised by sector, key horizontal legislation and existing support programmes and links to all major QI institutions (Serbian Ministry of Economy, 2021[15]).

The way forward for overall co-ordination and general measures

Establish a centralised, single information source for SMEs and other firms interested in exporting to the European Union. As information about technical regulations, standards and conformity assessment continues to be scattered, this recommendation, which was already made in the 2019 assessment, is still valid. Such a single information source can be provided by establishing a web portal that presents key information in a user-friendly way (e.g. clustering technical regulations and listing key horizontal QI legislation) and provides links to potential support programmes and the national QI bodies. In addition, an offline information channel in the form of a help desk may also be useful.

Develop/update strategies and action plans to better monitor and evaluate the institutional performance of quality infrastructure institutions. As QI requires various institutions to co‑ordinate their activities, having a joint strategy or pillar‑specific strategies (e.g. metrology, standardisation, accreditation) that are harmonised among each other is important. While most economies have developed such a strategy at some point, many documents are outdated and need to be adapted to reflect the most recent developments in the national, European and international QI landscapes. One positive example from the region is Serbia’s Quality Infrastructure Strategy (2015-2020) (Box 8.1).

Box 8.1. A joint quality infrastructure strategy: Serbia’s Quality Infrastructure Strategy (2015‑2020)

Despite having an institution that co-ordinates the economy’s quality infrastructure (QI) activities (usually the Ministry of Economy), most economies in the Western Balkans and Turkey (WBT) lack a joint QI strategy. A joint strategy could be an important guide for identifying common as well as dimension‑specific challenges, co-ordinating the activities of the different QI institutions, and setting joint as well as dimension-specific targets.

One notable exception in the region is Serbia, which has developed a five-year Quality Infrastructure Strategy (2015-2020). The strategy begins by analysing the status quo in each of the QI pillars (technical regulations, standardisation, accreditation, conformity assessment, metrology and market surveillance). For some areas this is done through a so-called SWOT analysis. This is followed by a list of objectives per QI pillar. Finally, the strategy is accompanied by annual action plans, which operationalise the strategy’s more generic objectives into concrete measurable activities. Each activity lists the responsible entity, a timeline and the budget source from which the respective activity is financed.

This traditional combination of a multi-year strategy and annual action plans is a good approach to break large strategic goals down into smaller pieces and keep track of them, which is particularly useful in a policy area like QI, which has so many different institutions.

The different QI pillars (i.e. technical regulations, standards, accreditation, etc.) are usually governed by different institutions in the WBT region, which poses the risk that QI activities are not (sufficiently) based on joint overarching objectives. Having a joint strategy can remedy this. Furthermore, due to the small size of most WBT economies, it often does not make sense for each of these institutions to have their own strategy; they could rather include their actions within a larger strategic framework. A joint QI strategy could set joint and pillar-specific objectives that would then be implemented by the different institutions at the different governance levels and monitored by a central authority, thereby assuring co‑ordination of and adherence to activities over the medium and long term.

Source: Serbian Ministry of Economy (2021[15]).

Harmonisation with the EU acquis (Sub-dimension 7.2)

The harmonisation of national legislation with the acquis is an essential step in the EU accession process. Harmonising national regulations with EU product legislation ensures the free movement of goods into and across the EU Single Market. It also benefits businesses by reducing regulatory burdens, ensuring that their products also meet European requirements once they comply with the national regulations and standards. EU-compliant technical regulations and adopted European standards provide firms with the regulatory security required to make long-term investments, like expanding their sales to the European Single Market.

This section examines the extent to which QI legislation and implementation procedures in the WBT economies are harmonised with the acquis. The assessment considers all six QI pillars, from technical regulations to standardisation, accreditation, conformity assessment, metrology and market surveillance. Serbia and Turkey continue to have the highest degree of alignment followed by Montenegro and Albania. Bosnia and Herzegovina continues to have the largest gap in alignment, as important laws are still not aligned with the acquis.

Table 8.3. Scores for Sub-dimension 7.2: Harmonisation with the EU acquis in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Technical regulations |

4.64 |

3.91 |

4.27 |

3.91 |

3.91 |

5.00 |

5.00 |

4.38 |

|

Standardisation |

3.40 |

2.38 |

3.53 |

3.27 |

4.07 |

5.00 |

4.73 |

3.77 |

|

Accreditation |

4.33 |

2.67 |

2.78 |

3.89 |

4.22 |

4.33 |

5.00 |

3.89 |

|

Conformity assessment |

4.24 |

2.86 |

4.71 |

4.43 |

3.86 |

4.71 |

4.71 |

4.22 |

|

Metrology |

5.00 |

3.97 |

3.62 |

3.31 |

4.85 |

4.38 |

3.77 |

4.13 |

|

Market surveillance |

3.40 |

3.44 |

3.67 |

3.27 |

4.47 |

4.47 |

5.00 |

3.96 |

|

Weighted average |

4.17 |

3.20 |

3.76 |

3.68 |

4.23 |

4.71 |

4.70 |

4.06 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Alignment with the EU acquis continues, albeit at a slow pace

The Western Balkans and Turkey continue to adapt their technical regulations to the acquis, as defined in their national integration plans. However, progress in the area of free movement of goods has been regarded mostly as limited in the European Commission’s recent reports. While all economies report that the technical regulations are aligned in their priority sectors, there continue to be gaps in alignment in both the harmonised and non‑harmonised areas. In most economies, evaluation of technical regulations is done on demand rather than in periodic cycles. Furthermore, having a detailed adoption plan with target dates for harmonisation, as, for example, in the Serbian, Montenegrin and Turkish national integration plans for EU accession, is important and should be adopted by all WBT economies.

Adoption of European standards continues to increase, but translation remains a challenge

The adoption of European standards continues to grow in the WBT region and, with the exception of Kosovo, all economies have adopted more than 80% of the CEN-CENELEC standards (Table 8.4). In particular, Montenegro, whose Institute for Standardisation of Montenegro is not yet a full CEN-CENELEC member, substantially increased its adoption rate from 70% to 86%. Kosovo is lagging behind in adoption partially because it has to request European standards on a case-by-case basis through a license agreement formed with CEN-CENELEC. This slows down the adoption process, considering that most economies adopt several hundreds or even thousands of European standards per year. Albania’s adoption rate slightly decreased between 2019 and 2022, but remains largely above the 80% required for members. The adoption rate can drop if the frequency of newly published European standards surpasses the rate at which national standards bodies convene to adopt the new standards or due to delays in reporting of the adoption decision between the national standards body and CEN-CENELEC.

With the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina, all WBT economies have aligned their national standardisation legislation with the European Regulation on Standardisation (1025/2012). As of March 2022, North Macedonia’s, Serbia’s and Turkey’s national standards bodies are full members of CEN‑CENELEC and Albania’s, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s, and Montenegro’s bodies are affiliate members. Montenegro applied for full CEN-CENELEC membership at the end of 2021 and the peer assessment is expected to be completed within a year.

Furthermore, most national standards bodies operate under a multi-year strategy that sets high‑level targets combined with an annual work plan, as required by Regulation 1025/2012, which specifies the type and number of standards that are planned to be adopted during the year. These plans are usually available on line. One drawback remains the limited translation of standards into local languages, as most national standards bodies continue to translate only the cover page of European or international standards. For example, the Turkish Standards Institute translated only 25% of the 24 516 European standards that have so far been adopted (TSE, 2021[16]; 2020[17]). Data are not available for the other WBT economies, but it can be assumed that their share of translated standards is even lower.

Table 8.4. Adoption of European standards by the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

Adoption rate 2019 |

Adoption rate 2022 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

98% |

93% |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

87% |

93% |

|

Kosovo |

50% |

50% |

|

Montenegro |

70% |

86% |

|

North Macedonia |

95% |

95% |

|

Serbia |

98% |

99% |

|

Turkey |

98% |

99% |

Notes: Data for Kosovo are only approximations as adoption rates for Kosovo are not monitored or reported by CEN-CENELEC. For Albania, CEN-CENELEC reports a lower adoption rate of 85%, but the Albanian standards body attributes this difference to a time lag in reporting.

Sources: CEN-CENELEC (2021[18]) and national standards bodies in the Western Balkans and Turkey.

The adoption rate of 94% mentioned in the Executive summary does not take into account the data for Kosovo as adoption rates for Kosovo are not monitored or reported by CEN-CENELEC.

The recognised accreditation scope and number of conformity assessment bodies continue to grow

The number of accreditation fields where the WBT accreditation institutes obtained MLA signatory status with the EA continued to increase during the assessment period (Table 8.5). Turkey is now an EA-MLA signatory in all fields, whereas North Macedonia and Serbia are signatories in the six primary fields. Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina also expanded their EA-recognised accreditation scope. Montenegro has been a full member of the EA since 2011 and applied for EA-MLA signatory status in five fields at the end of 2020. The government expects to complete its recognition process in 2022. Serbia also applied for a scope extension for the area of proficiency testing providers. Overall, this is a very positive development, as recognition of the national accreditation services by the EA means that certification obtained from conformity assessment bodies certified by the national accreditation institute is recognised by EA members. This facilitates market access for SMEs that wish to export to the European Union, as they may no longer need to seek certification outside their own economy.

The number of accredited conformity assessment bodies (CABs) grew on average by 30% in the WBT region between 2019 and 2022 (Table 8.6). This means that the possibilities for firms seeking to get their products, services or processes certified are growing. This lowers barriers to implementing standards, particularly for SMEs, which may not be able to seek certification abroad or in another region. However, matching the accreditation demands of this growing number of CABs with sufficient experts can be difficult, particularly for small economies such as Kosovo or Montenegro. To tackle this issue, the Accreditation Body of Montenegro has signed bilateral co-operation agreements with various Western Balkan economies, which also addresses the exchange of technical assessors and experts. In addition to the shortage of experts, many accreditation institutes in the region report administrative staff figures that are below the requested human resources. This shortage may also complicate the administration of a continuously growing number of CABs. Online registries of all accredited CABs are available in all WBT economies.

Table 8.5. Accreditation fields in which the Multilateral Agreement with European Co‑operation for Accreditation was signed with Western Balkans and Turkey economies

|

Accreditation fields |

ALB |

BIH |

MKD |

SRB |

TUR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Calibration |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Testing and medical examination |

X* |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Product certification |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Management systems certification |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Certification of persons |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Inspection |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Validation and verification |

X |

||||

|

Proficiency testing providers |

X |

* Signatory for testing laboratories only; not signatory for medical laboratories.

Notes: Scopes that were added between 2019 and 2022 are marked in green. Kosovo and Montenegro are not EA-MLA or Bilateral Agreement signatories.

Source: European Accreditation Directory of EA Members and MLA Signatories: https://european-accreditation.org/ea-members/directory-of-ea-members-and-mla-signatories.

Table 8.6. Number of accredited conformity assessment bodies in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

No. of accredited conformity assessment bodies |

2019 |

2022 |

Growth in % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Albania |

69 |

93 |

35% |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

116 |

151 |

30% |

|

Kosovo |

38 |

56 |

47% |

|

Montenegro |

33 |

43 |

30% |

|

North Macedonia |

206 |

259 |

26% |

|

Serbia |

628 |

727 |

16% |

|

Turkey |

1 580 |

1 980 |

25% |

Source: Survey responses on OECD SME Policy Index questionnaire filled out by relevant public institutions.

Metrology bodies are well-integrated in the international technical community, but lack sufficient staff capacities

With the exception of Kosovo, the metrology bodies of the WBT economies are all either full or associate members of the European Association of National Metrology Institution (EURAMET) and of the European Cooperation in Legal Metrology (WELMEC). The Kosovo Metrology Agency is currently a liaison organisation of EURAMET and applied for associate membership status in April 2021. Membership in these European and international associations is very important for WBT economies, as they get access to training and can take part in discussions and exchanges about the most recent global developments in metrology.

Various metrology bodies report a lack of sufficient staff or adequate premises. As metrology is a highly specialised field, it is not surprising that smaller economies find difficulties attracting sufficiently qualified staff. To address this, all metrology bodies in the WBT region have signed bilateral co-operation agreements with at least some of the other WBT economies. Furthermore, regional projects like the German-funded “South‑Eastern European Quality Infrastructure Fund” help bring together experts from the regions through joint training and seminars. Several WBT metrology bodies also participate in EURAMET’s inter-laboratory comparison programmes, which allow test results to be compared, thereby assuring the quality of testing services. For example, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, and North Macedonia all participate in regional volume comparisons.

Alignment with the EU Market Surveillance Regulation 2019/1020 is slow

Market surveillance was the only QI area in which the EU regulation changed during the assessment period. The new EU Regulation 2019/1020, which was adopted on 20 June 2019, added provisions on the regulation of online sales from non-EU member states that want to sell to the EU Single Market (European Commission, 2019[19]). So far, Turkey is the only economy that has already adapted its national market surveillance legislation to align with the new acquis. All WBT economies have some market surveillance legislation in place that is at least partially aligned with the old acquis 768/2008.1

Fast alignment with EU Regulation 2019/1020 is important, as the regulation will lead to intensified market surveillance activities and will restrict non-compliant products from outside the European Union more effectively (Norton Rose Fulbright, 2021[20]).

Inspection activities decreased in 2020 and 2021 compared to 2019 among most market surveillance agencies in the WBT region, due to impediments caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, three out of the seven WBT economies reported increased co‑ordination between the different public authorities on market surveillance compared to 2019. The other four reported no change in the level of co-ordination.

According to the most recent EU enlargement reports on the WBT economies, market surveillance remains the area where human resource constraints are the most pressing. Given the new demands from the adapted EU legislation, this may be an important area to strengthen staff capacities.

The way forward for harmonisation with the EU acquis

Further strengthen regional collaboration in quality infrastructure beyond bilateral co‑operation. As described above, the regional co-operation between the different QI institutions in the WBT region has improved over this assessment cycle. Co‑operation activities include the exchange of experts and assessors as well as joint training. However, most of this co-operation still happens through bilateral agreements. Truly regional co-operation at the level of CEFTA has so far been limited and should be further expanded so that all WBT economies can capitalise on the full QI expertise in the region.

Increase the frequency of evaluation of technical and horizontal quality infrastructure regulations. While most of the QI-relevant legislation is nowadays aligned with the acquis, the evaluation of regulations is mostly done on demand rather than reviewing them systematically. More frequent evaluation and comparison of national law with EU regulations can reduce the amount of unaligned legislation and reduce the time until said legislation is harmonised. As the reliance of WBT exports on the European Single Market is high, quickly aligning laws and procedures is particularly important.

SMEs’ access to standardisation (Sub-dimension 7.3)

The recently published European Standardisation Strategy (European Commission, 2022[21]) underlined the importance of SMEs as drivers and users of standards. As SMEs form the backbone of all WBT economies, both in terms of their share of economic output and in terms of employment, ensuring they have access to standards and participate in the development of standards is key.

This section gauges whether the existing policy frameworks foster SMEs’ awareness of the benefits of standards facilitate their participation in developing standards and reduce the financial burden of implementing standards.

Access to standards for SMEs in the WBT region has improved since the last assessment, particularly in the area of financial support (Table 8.7). However, there is still a lot of heterogeneity to the extent of which national standards bodies foster access and participation in the region.

Table 8.7. Scores for Sub-dimension 7.3: SMEs’ access to standardisation in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Awareness raising and information |

4.07 |

3.53 |

3.80 |

3.80 |

2.87 |

4.47 |

4.60 |

3.88 |

|

SMEs’ participation in developing standards |

3.00 |

2.50 |

3.50 |

3.00 |

2.50 |

3.50 |

4.50 |

3.21 |

|

Financial support to SMEs |

3.40 |

2.20 |

3.40 |

4.40 |

4.20 |

2.80 |

4.60 |

3.57 |

|

Weighted average |

3.49 |

2.74 |

3.57 |

3.73 |

3.19 |

3.59 |

4.57 |

3.55 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Basic awareness-raising activities are in place, but no new materials or practices have been introduced

All NSBs in the WBT region engage in basic awareness-raising activities through regularly updated news sections on their websites, social media accounts and in some cases newsletters or even magazines, as is the case of the Turkish Standards Institute. These activities are complemented by training as well as webinars, which have gained importance due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, in Serbia, Turkey and Republika Srpska, the NSBs also provide training and information seminars together with the national or local chambers of commerce. Such co-operations are very useful because the chambers of commerce usually have a much larger and decentralised network, which increases the outreach of such events well beyond the respective capitals.

Unfortunately, there has been very little progress with respect to the development of guides or case studies in the local language. The Turkish Standards Institute is the only NSB among the WBT economies that has sector-specific brochures introducing the main standards in the different business sectors. Furthermore, none of the NSBs have published a local language guide that explains the standard implementation process, from identification until completed conformity assessment. Such a step-by-step guide is particularly important for SMEs, which may not be very familiar with standard and conformity assessment procedures. The European Blue Guide is a good example of how to visualise and explain this process (see Box 8.2).

There are very few activities to foster SMEs’ participation in standards development

Fostering the participation of SMEs remains the most challenging area for standard-setting institutions, not only in the WBT region, but also in the European Union, which is why it was named one of the priorities in the European Union’s recent Standardisation Strategy (European Commission, 2022[21]). While moving technical committee meetings on line in response to the COVID-19 pandemic may have slightly lowered the barriers of participation for SMEs, little else has been done in the region to further incentivise SMEs to participate in the development of standards. However, during the research done for this report, it was noted that some NSBs are currently preparing more SME-related activities, meaning more developments may be seen in this area in the near future.

The NSBs in the region report having standard participation approaches like public enquiries on draft standards or public calls to receive feedback, but none of them are tailored to SMEs. With the exception of North Macedonia, which offers seminar discounts for SMEs that are members of the Standardization Institute of North Macedonia, no economy offers SME-specific financial support to incentivise participation in committee meetings or other standards meetings. While some economies offer discounts to technical committee members for the purchase of standards, this does not resolve the barrier to participation in the first place.

Two established approaches to foster SMEs’ participation are travel costs or meeting allowances as well as representation through SME associations (see Box 8.3). While allowances may be difficult to implement for most NSBs in the region due to budgetary constraints, closer collaboration with national SME associations may increase the representation of SME interests in the development of standards.

Projects that support standard-related costs for SMEs are expanding

A very positive finding of this report is that all WBT economies have at least one financial support programme that covers costs related to implementing standards for SMEs. However, it has to be noted that the programmes, either government- or international partner-funded, vary widely in their size and therefore in the number of firms they support.

A widely employed modality are government support programmes that cover costs up to a certain maximum share of total cost combined with a cap on the maximum amount per firm. For example, the Albanian Investment Development Agency’s Competitiveness Fund provides grants of up to EUR 10 000 per firm that cover up to 70% of the firm’s project costs. The fund supported 15 companies in 2018 and 30 in 2019 (Albanian Investment Development Agency, 2019[22]). Similarly, in North Macedonia, the Ministry of Economy’s Programme for Competitiveness, Innovation and Entrepreneurship co-finances up to 60% of certification-related costs for SMEs and supported 12 firms in 2019 and 11 in 2021 (APPRM, 2021[23]); it was paused in 2020. Montenegro and Serbia have similar programmes implemented by the Ministry of Economy (Box 8.2) and the Serbian Development Agency, respectively.

A second support channel are programmes offered by the chamber of commerce or other business association that also cover standard-related costs. The North Macedonia Agency for Promotion of Entrepreneurship has a voucher scheme that firms can use to get consulting services and small grants to cover standards-related costs (APPRM, 2022[24]). The Turkish SME development organisation KOSGEB also offers research, development and innovation support that covers up to 80% of costs related to certification for standards (KOSGEB, 2021[25]).

Box 8.2. Montenegro’s two-sided support programme for the introduction of international standards

The implementation of international standards continues to be a challenge for many small and medium‑sized enterprises (SMEs) in the Western Balkans and Turkey region. Two widely stated problems are:

the lack of conformity assessment bodies (CAB) in the region or economy for the specific sector or technology, which is particularly a problem in smaller economies,

high implementation costs to get certified.

Montenegro’s programme line for the introduction of international standards, introduced in 2018, is a very positive example, as it addresses both these challenges. The programme line is part of a larger competitiveness programme of the Ministry of Economic Development that encompasses a total of 17 support lines. Two of the programme’s components address both the supply of conformity assessment services as well as its demand:

1. The first component provides financial support to CABs by reimbursing up to 70% of the accreditation costs incurred. The support is limited to costs related to accreditation services for a series of international and European standards (ISO/IEC 17020, ISO/IEC 17025, ISO/IEC 17029, ISO/IEC 17021 -1, ISO/IEC 17024, ISO/IEC 17043, CEN/TS 15675, EN ISO 15189) and is only provided if the CAB successfully earned the accreditation certificate from the national accreditation body, the ATCG.

2. The second component provides financial support to SMEs by reimbursing up to 70% of the certification and recertification costs of management system standards (i.e. ISO 9001, ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001). The funds can be used for hiring consultants to help the company prepare the technical documentation required for the certification as well as for staff training.

Funding is capped at EUR 5 000 per firm on both components. To promote female entrepreneurship in particular, this programme is reimbursing up to 80% of the costs for female-led firms (compared to 70% for other firms). While being comparatively small, with total funding of EUR 765 000 between 2018 and 2000, a total of 217 SMEs benefited from the programme during that period. In 2021, the programme lines yielded EUR 250 000.

Overall, this programme can be regarded as a best practice because it simultaneously applies to the supply and the demand of conformity assessment services, thereby addressing the two main bottlenecks of small economies, namely insufficient local CABs and funding constraints for SMEs.

Source: Ministry of Economic Development of Montenegro (2018[26]).

A third support channel are support programmes funded by international development partners, as in the case in Kosovo, where SMEs can receive support via the World Bank’s Competitiveness and Export Readiness Program. The programme provides matching grants that cover up to 90% of the activity costs or up to EUR 40 000 per firm. These grants can be used to cover inspection-related costs that may arise in the certification process and to buy small equipment. In the first round of applications (2018-20), 28 SMEs received financial support (World Bank, 2021[27]). The second round of applications was held in mid-2021 and 139 firms were selected for support (World Bank, 2021[27]).

Overall, there are a wide range of SME support programmes available in the WBT region that also cover costs related to the implementation of standards. While the total number of firms supported by these programmes remains low, the number of beneficiaries has been growing over time in all economies, which is a positive sign.

The way forward for SMEs’ access to standards

Incentivise SMEs’ participation in technical standards committees through specific measures, such as travel support, online participation or representation by associations. SMEs form an integral part of the economy in many WBT economies, and it is therefore important to incorporate their knowledge and experience when developing new or adapting existing standards. As SMEs have more limited resources, national standards bodies need to provide specific incentives to increase their participation. The European Small Business Standards (SBS) has an interesting approach in this regard (Box 8.3).

Box 8.3. Representing SMEs in technical committees via associations: Small Business Standards’ representation at European and international technical committees

As CEN-CENELEC alone has 364 working groups and publishes more than 1 000 standards per year, it is hard for firms to keep track of which technical committees might be worth their time. Furthermore, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often lack the financial or human resources or time to take part in technical committee meetings, be it at the national, European or international level. To assure that SMEs’ interests are nonetheless being heard and taken into account at technical committee meetings, the European non-governmental organisation Small Business Standards (SBS) represents SMEs in technical committees. The SBS works with national SME associations to periodically select the technical committees that are of the most relevance for SMEs, then appoints experts to represent the SMEs in the technical committee meetings.

This approach assures that SMEs’ interests are being represented in the most relevant and impactful technical committees by designated experts. Due to the periodic review of the relevance of technical committees, national SME associations can articulate which technical committees are of particular relevance for firms in their economies. The SBS also keeps its members informed about the progress of the technical committees and the impact of new standardisation on SMEs, thereby assuring that the information is also relayed to the SMEs.

As economies in the Western Balkans and Turkey are also highly reliant on SMEs, introducing a representation mechanism to assure that their ideas and interests are being discussed in technical committees would be beneficial for both the economy and the firms. SMEs will benefit, as their demands, needs and feedback on standards will be incorporated into the standard development process without them needing to be present and they stay informed about the process. At the same time, the economy benefits from incorporating SMEs’ interests and knowledge into new or updated standards, as they will be better adapted to the needs of SMEs, which should increase their competitiveness in the future. Finally, incentivising participation through representation is also financially less burdensome than providing direct allowances for firms.

Source: Small Business Standards (2021[28]).

Develop guides that explain the conformity assessment process and standards development in the local language. Many SMEs that want to certify that their products, processes or services comply with international or national standards have little knowledge about the different steps and requirements. Most NSBs in the region only present basic information of the potential benefits of standards on their web page and more comprehensive guides from ISO, CEN-CENELEC or SBS are usually not available in the local language. Developing informational material in the local language is, therefore, crucial to facilitate SMEs’ access to quality infrastructure. One example for presenting the different steps of the certification process is the European Union’s Blue Guide (Box 8.4).

Box 8.4. Providing concise and clear information about product regulations and conformity assessment procedures: The European Union’s Blue Guide

To create a better understanding of its product rules and their application, the European Union created the so-called Blue Guide. This comprehensive guidebook is structured along actors and the different quality infrastructure pillars (e.g. conformity assessment, market surveillance), which allows the reader to quickly find the required information. The chapter on conformity assessment describes the certification process in a user-friendly way using a flowchart depicting the different steps required, from the technical documentation to the market placement of the product.

Through graphical means, the rather complex process of conformity assessment is explained and depicted in a clear, concise manner, which is particularly useful for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) which, contrary to large firms, may not have specialised staff familiar with quality infrastructure processes.

Economies in the Western Balkans and Turkey often lack such information materials and firms are therefore left with the legislative text or other material in complex, technical language, which may represent an information barrier for SMEs. Having process flowcharts and guides like the one described above available in the local language is one way to overcome such barriers for SMEs aiming to get their products or processes assessed and certified.

Source: Source: European Commission (2016[29]), Section 5.1.3. Actors in Conformity Assessment, and Flowchart 2.

References

[22] Albanian Investment Development Agency (2019), Annual Report 2019, Albanian Investment Development Agency, https://aida.gov.al/images/PDF/Raport-vjetor-2019.pdf.

[24] APPRM (2022), Voucher Manual, Agency for Promotion of Entrepreneuship of the Republic of North Macedonia, Skopje, http://www.apprm.gov.mk/WowerManual.

[23] APPRM (2021), Voucher, http://www.apprm.gov.mk/Voucher.

[1] Blind, K. and C. Koch (2020), “Introduction to quality infrastructure management”, lecture at Technische Universität Berlin.

[6] Blind, K., A. Mangelsdorf and J. Pohlisch (2018), “The effects of cooperation in accreditation on international trade: Empirical evidence on ISO 9000 certifications”, Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 198, pp. 50-59, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.01.033.

[18] CEN-CENELEC (2021), “CEN-CENELEC in figures Q4 2021”, https://www.cencenelec.eu/stats/CEN_CENELEC_in_figures_quarter.htm.

[7] Doner, R. (2016), “The politics of productivity improvement: Quality infrastructure and the middle-income trap”, Thammasat Economic Journal, Vol. 34/1.

[21] European Commission (2022), An EU Strategy on Standardisation-Setting Global Standards in Support of a Resilient, Green and Digital EU Single Market, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/48598.

[3] European Commission (2021), “Turkey trade picture”, web page, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/turkey.

[2] European Commission (2021), “Western Balkans trade picture”, web page, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/western-balkans.

[19] European Commission (2019), Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 of the European Parliament and of the Council, L 169/1, Official Journal of the European Union, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32019R1020&from=EN.

[29] European Commission (2016), The “Blue Guide” on the Implementation of EU Products Rules 2016, Official Journal of the European Union, C 272/1, Vol. 59, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/18027/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/native.

[12] European Parliament (2020), “EU-Turkey customs union: Modernisation or suspension?”, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2020)659411.

[14] Eurostat (2021), “International trade of EFTA and enlargement countries”, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/EXT_LT_INTERCC__custom_1877851/default/table?lang=en.

[13] Eurostat (2020), Western Balkan Countries-EU: International Trade in Goods Statistics, European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Western_Balkans-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics&oldid=526493#:~:text=The%20EU%20was%20the%20main,(58%20%25)%20in%202021.&text=In%202021%2C%20manufactured%20goods%20made,import (accessed on 5 September 2018).

[10] Guasch, J. et al. (2007), Quality Systems and Standards for a Competitive Edge, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-6894-7.

[11] Harmes-Liedtke, U. and J. Oteiza Di Matteo (2020), Global Quality Infrastructure Index Report 2020, Global Quality Infrastructure Index, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.27782.50249.

[5] Kaloyanchev, P. and I. Kusen (2018), Untapped Potential: Intra-Regional Trade in the Western Balkans, Discussion Paper 080, European Union, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/economy-finance/dp080_western_balkans.pdf.

[25] KOSGEB (2021), SME Development and Support Administration, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Organisation of Turkey, Istanbul, https://webdosya.kosgeb.gov.tr/Content/Upload/Dosya/AR-GE%20UR-GE/UE-02-02_(01)_Ar-Ge_U%CC%88r-Ge_ve_I%CC%87novasyon_Destek_Program%C4%B1_Uygulama_Esaslar%C4%B1--.pdf.

[26] Ministry of Economic Development of Montenegro (2018), Program: Introduction of International Business Standards 2018, Ministry of Economic Development, https://www.gov.me/dokumenta/b1986ce0-f999-4c8c-b052-e874b5269998.

[20] Norton Rose Fulbright (2021), “Update on product compliance: The EU Market Surveillance Regulation applies from 16 July 2021”, web page, https://www.nortonrosefulbright.com/en-fr/knowledge/publications/59c9fd8d/update-on-product-compliance.

[4] Sanfey, P. and J. Milatovic (2018), The Western Balkans in Transition: Diagnosing the Constraints on the Path to a Sustainable Market Economy, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, https://www.ebrd.com/documents/eapa/western-balkans-summit-2018-diagnostic-paper.pdf.

[15] Serbian Ministry of Economy (2021), TEHNIS website, https://tehnis.privreda.gov.rs/en.html.

[28] Small Business Standards (2021), “SMEs representation in drafting standards”, web page, https://www.sbs-sme.eu/sme-involvement/policy/representing-smes-standardisation.

[9] Swann, G. (2010), “International standards and trade: A review of the empirical literature”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 97, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5kmdbg9xktwg-en.

[16] TSE (2021), Annual Report 2019, Turkish Standards Institute, https://statik.tse.org.tr/upload/tr/dosya/dokumanyonetimi/107/12032020142734-1.pdf.

[17] TSE (2020), Annual Report 2020, Turkish Standards Institute, https://statik.tse.org.tr//upload/tr/dosya/dokumanyonetimi/107/28072021163835-1.pdf.

[8] UNIDO (2017), “UNIDO partners with technical institutions on quality infrastructure to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)”, United Nations Industrial Development Organization, https://www.unido.org/news/unido-partners-technical-institutions-quality-infrastructure-achieve-sustainable-development-goals-sdgs.

[27] World Bank (2021), “Kosovo: Competitiveness and Export Readiness Project – P152881”, web page, https://projects.worldbank.org/en/projects-operations/project-detail/P152881.

Note

← 1. In the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the degree of alignment with the EU acquis may depend on the entity, as most laws referring to quality infrastructure are made at the entity level. While the market surveillance legislation at the central government level in Bosnia and Herzegovina is not aligned with 768/2008 (i.e. the old acquis), Republika Sprska claims that its more recent legislation from 2013 is partially aligned with this EU legislation.