This chapter assesses policies in the Western Balkans and Turkey to promote the skills small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) need, from start-up throughout the different growth phases. It starts by providing an overview of the assessment framework and progress since the last assessment in 2019. It then presents an analysis of Dimension 8a’s three thematic blocks: 1) planning and design, which assesses policies in the areas of skills intelligence; 2) implementation, which focuses on training provision for SMEs, responding to the skills required of digital and green economies, and smart specialisation; and 3) monitoring and evaluation, which considers whether economies ensure their SME skills policies are working and keeping up with market needs. The chapter concludes with key recommendations to help the region’s policy makers tackle the challenges identified.

SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2022

9. Enterprise skills (Dimension 8a) in the Western Balkans and Turkey

Abstract

Key findings

The provision of skills intelligence is improving across the Western Balkans and Turkey (WBT) region. However, there is significant scope to keep making progress to ensure a robust and comprehensive evidence base to shape policy decisions across government is available in all economies.

There is an overall increase in the provision of enterprise skills training across all WBT economies. However, there is not yet sufficient focus on training to support SMEs coping with ongoing major structural transformations for key themes such as digitalisation and the green transition.

Training for the social economy sector is underdeveloped across all economies, with a lack of government-financed training or support tailored to the needs of social enterprises and co-operatives.

Skills training for the green and circular economy is not well developed; more development is needed.

All WBT economies recognise the importance of the digital economy for SMEs. However, there remains an implementation gap between policy and practical training provision and support.

Some progress can be seen in the availability of gender-disaggregated data. However, work remains to ensure comprehensive provision of gender-sensitive data in skills intelligence and analysis of government-financed enterprise skills actions.

There is lack of effective monitoring and evaluation, particularly regarding the efficacy of government programmes and the change created as a result. In most economies, there is no comprehensive evaluation of government-funded training.

SME skills need to be embedded into smart specialisation strategies; as yet, there has been no visible consideration given to gender mainstreaming as part of the smart specialisation strategies (S3) process.

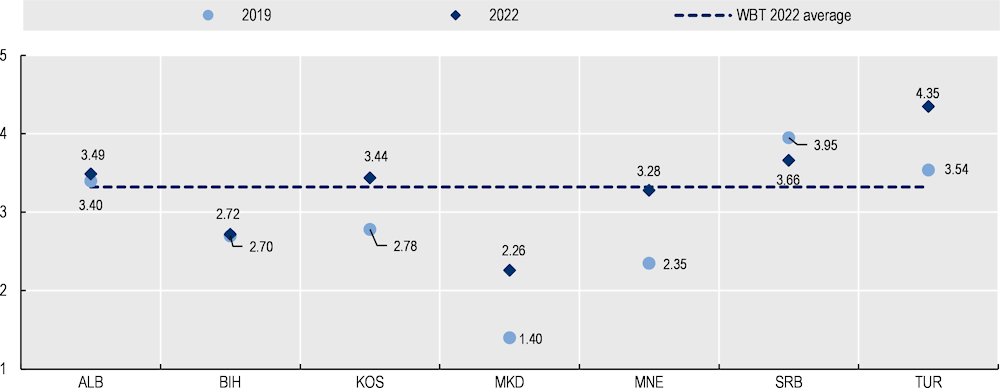

Comparison with the 2019 assessment scores

Overall, there has been good progress on the enterprise skills dimension since the 2019 assessment. Turkey is the top performer and is the only economy to improve across each thematic block. Looking at the specific scores for each economy (Figure 9.1), Montenegro has made the most progress in this assessment period, particularly for practical implementation of support and training. North Macedonia has also moved forward significantly after having launched a new SME policy that includes new actions on SME skills training during this assessment period. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo have made more modest progress. Serbia has a lower score than in 2019 due to less provision across the expanded questions linked to digitalisation, digital skills and green transition, which is intended to be addressed in the upcoming SME Strategy anticipated for 2022.

Figure 9.1. Overall scores for Dimension 8a (2019 and 2022)

Notes: WBT: Western Balkans and Turkey. Despite the introduction of questions and expanded questions to better gauge the actual state of play and monitor new trends in respective policy areas, scores for 2022 remain largely comparable to 2019. To have a detailed overview of policy changes and compare performance over time, the reader should focus on the narrative parts of the report. See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for information on the assessment methodology.

Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations

Table 9.1 summarises progress on the key recommendations for the enterprise skills dimension since the previous assessment.

Table 9.1. Implementation of the SME Policy Index’s 2019 recommendations for Dimension 8a

|

Regional 2019 recommendation |

SME Policy Index 2022 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Main developments during the assessment period |

Regional progress status |

|

|

Designate a body to strengthen SME skills intelligence |

Good progress can be seen in three economies. In Kosovo, there is now a set of three tools including the online Labour Market Barometer, the Vocational Education and Training (VET) Barometer, and the Skills Barometer. These are dynamic tools developed through funding from international development co-operation partners in Aligning Education and Training with Labour Market Needs (ALLED2). Sustainability for the Labour Market Barometer is now confirmed by the government taking ownership, with the Employment Agency managing further implementation. In Turkey, the ambitious Geleceğin Becerileri programme has been launched to lead the development of skills intelligence and solutions to reduce the skills gap. Third, Albania has recently allocated a budget to the Albanian Investment Development Agency (AIDA) to lead the creation and implementation of a national skills intelligence framework. While not yet implemented, this is a good step forward. |

Moderate |

|

Build SME skills into smart specialisation strategies |

This has been achieved through the two national smart specialisation strategies launched in the region in Montenegro and Serbia. Both strategies are seen as examples of good practice in involving small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the development process, while skills are explicit within the narrative and actions of the strategy for each economy. |

Moderate |

|

Refine and better target the training offer |

The SME training offer has been improved during this assessment period, with an increased variety of training financed by the government, and enhanced by a wider offer of training from funded by international development co-operation partners or non-government led training initiatives. More work remains to be done to consolidate training offers across all government and non-government providers. In Turkey, regional administrations are leading the way in this work. |

Moderate |

|

Make training offers relevant for local growth and competitiveness |

There is now more availability of training that targets early-stage and more established businesses, through technology or growth programmes. However, these programmes are not yet widespread and the impact is not well understood. Initiatives like Boost Me Up in Montenegro is an example of an in-depth start-up programme for innovative businesses, developed by non-governmental organisations and co-financed by the government. In Kosovo, a triple helix-based agreement was signed in 2021 between the city of Pristina, the University of Pristina and the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce, the first of its kind in the economy and an example of collaboration to support new SME and labour market skills development initiatives. However, more work needs to be done to spread the triple-helix model across the region, engage further universities and open up more engagement from VET institutions in the entrepreneurial ecosystem. |

Limited |

|

.Boost SMEs’ innovation potential by building on the digital and green economies |

While all economies now highlight the importance of training for green and digital economies, this is not yet translated into practical implementation across all economies. There remains a significant implementation gap between policy and training for green transition, with not all economies providing government funded support or training across all the key themes of sustainability, resource efficiency and the circular economy. Training for digital skills and digitalisation has seen more progress during this assessment period, though a comprehensive government-supported SME training offer remains to be developed in North Macedonia. |

Moderate |

|

Build the systems and capacity to monitor SME skills policies and policy interventions |

Monitoring and evaluation approaches remain under-developed in all WBT economies with limited progress during this assessment period. While policy commitment has progressed, for example in Albania, there is a real need for concrete progress towards comprehensive actions to collate and analyse data for SME skills to support skills and smart specialization policies, including gender disaggregated data. |

Limited |

Introduction

Enterprise skills are critical to ensuring that businesses, co-operatives and social enterprises reach their potential and positively contribute to social cohesion and sustainable economic growth. Despite the crises of past years, SMEs remain dominant in terms of number and employment in every economy. In the WBT region, they employ approximately three-quarters of the total business sector,1 which is higher than the EU average. Enterprise skills are needed more than ever following the COVID-19 crisis, which has left businesses in the WBT region severely challenged in many sectors, after a period of increasing job creation (World Bank, 2020[1]). Barriers to growth are many, notwithstanding recent research that found that there is a potential lack of awareness among SMEs that they are underperforming against their potential (World Bank, 2020[1]). Government intervention for SME skills support is vital to help overcome potential financial barriers and raise awareness of the importance of this skills development offer across key themes such as digitalisation and sustainability. In the WBT region, SMEs are more likely to remain in low value-added sectors and create lower paid jobs than large enterprises. To overcome barriers to growth, SMEs need to invest in skills, greening, digitalisation and innovation to boost productivity and create higher paid employment.

There are new business opportunities emerging in which SMEs can find their paths in different and emerging sectors such as green growth or those identified within smart specialisation entrepreneurial discovery processes. Supporting enterprises with skills development to reskill and upskill will help improve their capacity to adjust to new circumstances and opportunities. Social economy businesses, including social enterprises and co-operatives, are a growth sector in the European Union, and this is still to develop in the WBT region.

Investment in enterprise skills takes action by policy, education and training providers, and civil society and involves SMEs themselves as primary users. A first step should always be to secure adequate skills intelligence to avoid skills mismatches. This is critical to underpin and justify decisions taken to shape policy and implement specific skills development actions across an economy. In times of significant change, this process needs to be dynamic and responsive to evolving markets and opportunities.

Assessment framework

Structure

The assessment framework for the enterprise skills dimension is divided into three thematic blocks (Figure 9.2): 1) planning and design (30% of the total score); 2) implementation (50% of the total score); and 3) monitoring and evaluation (20% of the total score). See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for more information on the methodology.

Figure 9.2. Assessment framework for Dimension 8a: Enterprise skills

The assessment framework for Dimension 8a has not changed substantially since the 2019 assessment. However, some policy and implementation aspects have been expanded to better gauge the actual state of play in those areas and add new perspectives that have grown in importance since the previous assessment questionnaire.

Across all thematic blocks, there is an expanded perspective of enterprises to include social impact business models, particularly social enterprise and co-operatives, reflecting their increasing importance in recent European and regional policy. It also pays more attention to practical SME-linked engagement and implementation related to smart specialisation, based on recommendations from the 2019 assessment. More emphasis is placed on SME skills for a green and digital transition across all three thematic blocks to align with European policy priorities. Within the third thematic block on monitoring and evaluation, questions have been added to better capture how evaluation results have been used, and whether there is a publicly available database on SME skills. Finally, a question has been added on training for intellectual property as a key driver for SME innovation.

Analysis

This dimension assesses government support for SMEs in developing enterprise skills, to illustrate the extent to which economies are providing the right skills development support aligned to economic priorities, including smart specialisation domains. For the purposes of this assessment, enterprise skills comprise business skills (e.g. sustainable business practices, greening, digital skills, marketing and finance); entrepreneurship as a key competence (e.g. creativity, sustainable thinking, planning and management, taking initiative – as defined in EntreComp) (Bacigalupo et al., 2016[2]); and vocational skills (i.e. professional skills for specific sectors). All three areas are necessary to launch and nurture sustainable and resilient businesses, co-operatives, and social enterprises during challenging social and economic conditions. The need for skills will change as an enterprise moves from start-up to growth phases and will also constantly evolve in response to new circumstances and opportunities, such as internationalisation, market change or technological advances.

Overall, Turkey performs best in this dimension, thanks to scores well above average in all three thematic blocks (Table 9.2). Serbia also performs well, reflecting the substantial resources the Serbian government is investing in SME support, including training services dedicated to specific target groups of SMEs and supporting different phases of enterprise development. Albania also scores above average in all three thematic blocks, while North Macedonia scores the lowest across the board – most of the initiatives that would increase its score are in the pipeline but not yet in place.

Table 9.2. Scores for Dimension 8a: Enterprise skills in the Western Balkans and Turkey

|

ALB |

BIH |

KOS |

MKD |

MNE |

SRB |

TUR |

WBT average |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Planning and design |

2.17 |

2.04 |

3.58 |

1.17 |

3.17 |

3.75 |

4.17 |

2.86 |

|

Implementation |

4.21 |

3.42 |

3.53 |

3.16 |

4.00 |

3.88 |

4.74 |

3.85 |

|

Monitoring and evaluation |

3.67 |

2.00 |

3.00 |

1.67 |

1.67 |

3.00 |

3.67 |

2.67 |

|

Weighted average |

3.49 |

2.72 |

3.44 |

2.26 |

3.28 |

3.66 |

4.35 |

3.32 |

Note: See the Policy Framework and Assessment Process chapter and Annex A for more information on the methodology.

Enterprise skills policy can be seen in various strategies across the region

Enterprise skills policy has cross-government links, reaching the domains of education and training, employment and those more linked to economic development including innovation, smart specialisation, entrepreneurship and the directly relevant area of SME development.

Table 9.3 shows the range of strategies highlighted in each economy. In some economies, previously relevant strategies have lapsed, such as the entrepreneurial learning strategy in North Macedonia and the National Strategy for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Turkey. In Kosovo, the new National Development Strategy is under development, while in Albania, there is a renewed vision for the development of SME skills intelligence and support programmes through the recent Business Development and Investment Strategy 2021-2027.

Table 9.3. Current strategiescovering enterprise skills

|

Economy |

Relevant strategy |

|---|---|

|

Albania |

Business Development and Investment Strategy 2021-2027 National Employment and Skills Strategy 2019-2022 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina Development Strategy 2021-2027 – Innovation Action Plan 2021-2023 Republika Srpska: SME Development Strategy 2021 – Government Work Programme 2021 |

|

Kosovo |

Private Sector Development Strategy 2019-2022 National Strategy for Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2019-2023 |

|

Montenegro |

National Strategy for Lifelong Entrepreneurial Learning 2021-2024 Smart Specialisation Strategy Operational Plan 2021-2024 |

|

North Macedonia |

SME Strategy 2018-2023 |

|

Serbia |

Industrial Policy Strategy 2021-2030 4S Smart Specialisation Strategy Serbia 2021-2027 Employment Strategy 2021-2026 |

|

Turkey |

Eleventh Development Plan 2019-2023 KOSGEB Strategic Plan 2019-2023 National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2021-2025 Ministry of Economy Strategy Plan 2018-2022 National Employment Strategy 2014-2023 Green Deal Action Plan 2021 |

Notes: The documents above highlight enterprise skills as a priority. Please note, they may not include specific actions or targets. For more insight, see the more detailed narrative for each economy.

Development of skills intelligence is still in progress and needs to move faster

Improving skills intelligence is the foundation of upskilling and reskilling for SMEs and their employees. The European Skills Agenda (European Commission, 2020[3]) identified that this process of aligning skills to the needs of the labour market must begin with the creation of strong skills intelligence frameworks embedded into national policy and in partnership with social partners. For the WBT region, the European Commission has highlighted the significant constraints to business caused by skills mismatch (European Commission, 2021[4]); national skills intelligence must form a critical part of any solution.

Skills intelligence is gathered to different extents across all economies, but good progress can be observed during this assessment period. Most economies undertake actions that develop national skills intelligence ranging from training needs analyses and sector-based studies to analysis of employment statistics. Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and Turkey stand out for their approaches. Kosovo has launched three statistical skills intelligence barometers. Developed as collaborations between international development co-operation partners’ agencies and the government, these include the Labour Market Barometer,2 the VET Barometer3 and the Skills Barometer4 (Box 9.1).

Box 9.1. Statistical barometers used to strengthen the skills agenda in Kosovo

In Kosovo, a set of statistical barometers has been developed to strengthen the skills agenda and establish a domestic approach to skills intelligence. The three barometers so far established are: 1) the Labour Market Barometer, which collates information and analysis from 12 institutional data sources1 2) the VET Barometer, which collates 200+ variables from 20 vocational education and training (VET) schools; and 3) the Skills Barometer, launched in December 2021, which will collect 3-5-year forecasts of skills needs from businesses in Kosovo to inform government and other institutions.

The challenge in Kosovo has been to ensure sustainability for the work initiated through funding by external partners. The Labour Market Barometer is a portal collecting information, resources and data on current and future skills needs for the labour market and creates strong collaboration between diverse partner institutions relevant to the skills agenda. The system is now managed by the Employment Agency, after a two-stage development phase supported by the United Nations Development Programme and Aligning Education and Training with Labour Market Needs (ALLED2), a project of the Austrian Development Agency. ALLED2 developed the Skills Barometer in co‑operation with the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce, and commitment is now finalised between the Kosovo Chamber of Commerce, the Ministry of Education and the National Council for VET to conduct the barometer every three years. The VET Barometer grew from pilot research into the provision across VET schools in the economy, and now offers online information and analysis based on systematic data collection that can be transferred to relevant agencies.

This example shows a pathway to shaping a domestic skills intelligence framework at the system level based on the need to support evidence-based policy making using robust information on skills mismatch and future skills needs. The actions stemmed from initiatives funded by international development co-operation partners towards sustainable action led by a partnership of public and private sector institutions and offer a channel to bring together and present available government statistics.

1. See: https://sitp.rks-gov.net for a list of the institutional databases used to create the Labour Market Barometer.

In mid-2021, Turkey launched a high-profile Skills Gap Reduction Accelerator Programme linked to a multi‑country World Economic Forum initiative. The Geleceğin Becerileri programme5 has a cross‑government commitment from key ministries to implement a set of actions designed to significantly upgrade skills intelligence provision, anticipation and evaluation at the national and regional levels.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, there is ongoing, extensive research to collate and analyse data to provide state- and entity-level skills intelligence on a range of themes, including women, sectors and specific geographic areas. This process is resulting in a growing database of publicly available reports and is led by the EU-funded Improving Labour Market Research6 programme.

Other economies have also shown good development during this assessment period. Serbia has undertaken a comprehensive analysis within the evaluation of the previous Employment Strategy and carries out a regular training needs analysis as part of the national employment action plans. In Albania, plans are in place to implement a national skills intelligence framework led by AIDA through a new department, with a newly committed budget from the Business Development and Investment Strategy 2021‑2027.

Overall, there is a lack of evidence of how available skills intelligence has been used to inform policy development and develop new training programmes. In economic reform programmes in the region addressing broad sectors, there are rarely specific priorities or actions related to SME skills intelligence or training programmes.

Specific aspects of skills intelligence receive less focus. However, training needs analyses are carried out in all economies except North Macedonia. Skills anticipation is less visible, though actions are evidenced in Kosovo, Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey. Most economies include digital skills intelligence, as in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Serbia, and Turkey.

Gender-sensitive skills intelligence is not standard, with ongoing challenges across the region to ensure the availability of gender-disaggregated data and analysis. A recent research study by the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) made a positive link between gender equality and a well-functioning skills system.7

In economies with a current smart specialisation strategy, there remains a need to upscale the provision of skills intelligence. This will be critical for evidence-based development at both the national and regional levels to fully develop the potential of S3 priorities.

Montenegro and Serbia have taken steps toward creating a national skills intelligence framework, though the national body taking lead responsibility for this work has not yet been defined. It is important to unite these different areas of skills intelligence and combine the sources necessary to create a coherent picture of current and future skills needs. This area of work requires urgent action to underpin the wider developments in education, training, employment, SME skills and smart specialisation that would benefit from a comprehensive skills intelligence framework as a robust evidence base.

Training provision has improved, but gaps remain

The importance of SME training is well recognised in all economies. The training offer across the region has consistently increased since the last assessment across all themes, from start-up through to training provided to SMEs and their employees to support their development throughout their lifecycles.

Government-financed start-up training programmes have increased during this assessment period and are now available to different extents in all economies. Kosovo and North Macedonia offer more limited support. In North Macedonia, start-up training at the pre-start stage is provided via the employment agency, while wider support is led by the Agency for Support of Entrepreneurship. This wider support includes time‑limited access at certain times of the year to business counselling vouchers for early-stage start-ups and women entrepreneurs. In Kosovo, training is generally driven by international development co-operation partners with limited government-financed training via the Kosovo Investment and Enterprise Support Agency, which organises business plan competitions and basic training on legal issues and marketing. The offer in Albania is growing from mainly grant funding to additional SME training provision led by AIDA, newly financed by the Business Development and Investment Strategy 2021-2027. Once launched, this has the potential to become an example of training and mentoring delivered as an integral part or pre-condition of the grant programme, enhancing the potential for success for entrepreneurs and their businesses.

Every WBT economy provides an element of tailored training for women and youth entrepreneurs, while most also provide training for technology start-ups. In Montenegro, a consortium supported by finance from the Ministry of Economy has launched the Boost Me Up programme8 as a pre-accelerator for innovative start-up teams to develop their ideas through a five-month training, mentoring and grant programme. This is the first such programme in the economy, and the sector focus of the start-up ideas to be developed are required to align with the priorities of the national smart specialisation strategy.

Restart entrepreneurs are not widely supported, and where provision exists, it is through access to generic start-up programmes. This can be a lost opportunity given the increases in business closures through recent crises, such as COVID-19 and the conflict in Ukraine. Restart entrepreneurs already have business experience and are statistically more likely to grow and succeed in their second or subsequent business ventures. However, they may face different challenges, such as overcoming fear of failure and access to finance for those who may have debt or bankruptcy issues. There are no visible examples of bespoke training in the region, but EU-funded projects such as Restart+9 offer insights into relevant training and tools. There is a real need to support experienced entrepreneurs who benefit from experience and lessons learnt from their previous business activities and who are more likely to succeed as second-time entrepreneurs creating businesses that contribute to the economy and employment. For wider insights on bankruptcy and second chance for SMEs, see Chapter 2 of this volume.

Training for intellectual property is provided in most economies, including Montenegro, Serbia and Turkey, which are all active in smart specialisation and the highest ranked within the region on the Global Innovation Index,10 for which intellectual property and patents are an important marker. As business moves more on line and becomes ever more global, the importance of patents and ownership of intellectual property becomes more evident, with critical importance of developing innovation, particularly within smart specialisation priority domains.

In every WBT economy, government-led training is complemented by actions undertaken by private or non-governmental actors, through support, training and mentoring to entrepreneurs and SMEs, often supported by funding from international development co-operation partners or grant programmes from the government. In Albania, despite the low level of government-financed provision, the level of training and support available in the economy from actors within its entrepreneurial ecosystem is notable for its variety and amount of information available on different opportunities. The information can be accessed through the AlbaniaTech portal developed with funding by external partners through the EU for Innovation programme and now sustained through multiple private sources and those from international development co-operation partners. The case is similar in Kosovo, where limited training is detailed via the online portal at the Kosovo Investment and Enterprise Support Agency’s website, but an alternative online portal, called StartUpKosovo, details a broader offer of SME support and skills training. These examples highlight the value of a one-stop shop portal collating both government and non-government information and opportunities to open up access to wider and new audiences.

While policy acknowledges the importance of the social economy, actions to understand and support the skills development needs of this sector are still to be developed

Across Europe, there is now strong emphasis placed on developing social economy businesses11 as contributors to sustainable, green and resilient social and economic growth. This sector is now recognised within the proximity and social economy ecosystem, one of the 14 industrial ecosystems identified in the new EU Industrial Strategy (European Commission, 2020[8]). The new 2021 European Social Economy Action Plan (European Commission, 2021[9]) intends to provide a blueprint to support social economy actors, including social enterprises and co-operatives, to grow, innovate and create new employment. As a picture of the scale of this sector, 2.8 million social economy entities employ 6.2% of all workers across Europe. The new EU Social Economy Action Plan has committed to specific actions for the WBT region to boost support and access to finance for social entrepreneurs, as part of a vision to develop the sector across economies surrounding the European Union.

Through this lens, the sectors covered have been expanded to include social enterprise and co-operatives for the first time in this assessment period. The evidence across the economies shows that this is an emerging sector that is still to be developed and supported to achieve its social and economic potential. Legal forms for social enterprises do not yet exist in all economies, though this is changing,12 while co‑operatives may primarily be in agricultural or food systems related sectors (Rosandić, 2018[10]). While there is clear evidence that social economy businesses are supported through training, it is not yet included in data relating to skills intelligence in any WBT economy except Turkey, where recent research provides comprehensive data and analysis of the sector.13

However, there is a mismatch between support and training provision and national policy. Policy in most economies recognises the importance of training to develop the social economy sector, as seen in Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey and at the entity level in Bosnia and Herzegovina within Republika Srpska. In contrast, few economies provide practical actions. Training programmes that take into account the needs of social enterprises and/or co-operatives are only evidenced at the entity level in Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Start-up support is available for co-operatives in Montenegro and both entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and for social enterprises in North Macedonia, Serbia and Turkey.

Investment is needed to grow the social economy sector and benefit from the wider social impact that comes with the added social and environmental value focus of this sector, with research showing that social economy businesses are more likely to be green and sustainable businesses (Rural Development Network of North Macedonia, 2020[11]). Increasingly across Europe, new legal models allow social enterprises to access commercial opportunities and create profit that can be channelled into social impact actions. High-quality training designed for aspiring social entrepreneurs can unlock a return on investment that has the triple objective of supporting people and community, preserving the planet, and driving sustainable economic growth.

SME training for a green transition is not yet evident across all economies

Commitment to sustainable and green recovery post-COVID is at the heart of European SME policy and the Green Deal (European Commission, 2019[12]), the principles of which are made directly relevant to the Western Balkans through the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans (European Commission, 2020[13]), Turkey, for its part, has responded through the launch of the Green Deal Action Plan (Government of Turkey, 2021[14]). This becomes more imperative when considering the clean energy, infrastructure and technology challenges to be transformed in the region to achieve climate targets.

With SMEs representing 99% of the business population, they are integral to the green transition. All WBT economies recognise the importance of training to support the transition to a sustainable and green economy in their national policies. However, this is not always translated into practical training for SMEs, covering key themes of sustainability, resource efficiency and the circular economy. Most economies, except Montenegro and Serbia, provide government financial support to deliver training on sustainable business and resource efficiency. For the circular economy, four economies and the entity of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina provide training, with a gap in Kosovo, Montenegro and Serbia as well as at the entity level in Republika Srpska.

The importance of training for a digital economy is recognised in all economies’ economic policies

The COVID-19 crisis has brought digitalisation and digital skills training into sharp focus. All WBT economies recognise the importance of supporting SMEs to adapt and integrate into the digital economy. Government support is available in most economies (except at the entity level in Republika Srpska) to buy digital and information and communication technology (ICT) resources. Almost all economies provide a comprehensive set of training to help SMEs adapt, including training on the digital single market, digitalisation and digital skills training. This is often delivered by government agencies linked to SME development or employment or through government funding programmes supporting delivery by private or non-governmental organisation actors, and involvement can be seen from Enterprise Europe Network providers, especially where training is linked to internationalisation. In Turkey, a number of digitalisation initiatives feature private sector collaborations. The only exception is North Macedonia, which does not provide government support for this training. However, funding by international development co-operation partners has been active in this area in North Macedonia as part of the World Bank COVID-19 response, providing support to SMEs for rapid reorganisation and implementation of digital tools and systems, so companies could easily adjust to new market conditions.

Smart specialisation has progressed, but challenges remain, including the need for gender mainstreaming

Smart specialisation builds on the strengths and potential of an economy, matching the resources available to the opportunities for development and growth. Research and innovation are at the heart of opening up the entrepreneurial and innovation potential of specific sectors across an economy. To be successful, smart specialisation should use an inclusive approach that embraces broad and diverse stakeholders in the process of discovery, resulting in the identification of priority domains and a process of strategic actions implemented, monitored and evaluated to grow these sectors and the associated supply chains. Consideration of the enterprise skills needed to drive forward smart specialisation is vital. Smart specialisation strategies are under development in all economies, as is highlighted across policy. National strategies have already been launched in Montenegro (2019) and Serbia (2021), while Turkey has opted for a regional approach. Kosovo and North Macedonia are planning their first strategies for 2022, while Albania has initiated the process. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the S3 process is not yet initiated.

There are evident challenges in both the initial strategy development process and practical implementation at the national and regional levels, including government capacity, stakeholder engagement, adequate skills intelligence, gender-disaggregated data and the need to include relevance to the S3 priorities across existing and new policy and strategy. Serbia stands out for the effectiveness of its approach and continuous entrepreneurial discovery process, while Montenegro has been recognised for its efforts to successfully engage stakeholders, including SMEs (Bolognini, 2021[15]). The engagement of a diversity of SMEs from both national and regional levels in the entrepreneurial discovery process and subsequent stages is a vital factor in developing the relevance of S3 and overcoming scepticism and potential lack of engagement from the business community. To overcome this, a number of economies have established awareness-raising campaigns and launched national S3 portals14 to provide information and raise the profile of the process among key stakeholders. Gender-sensitive policy making should also be a consideration in S3 development. There is no visible evidence of this within currently launched national strategies in the region.15 This should be strengthened across all policy development, including S3, placing more emphasis on the need for gender-disaggregated data and embedding gender as a cross-cutting theme across all S3.

Monitoring and evaluation have improved, but there is more work needed to ensure that it supports skills intelligence

Monitoring and evaluation approaches remain underdeveloped in all WBT economies. While improvements can be seen during this assessment period, the lack of comprehensive provision of monitoring and evaluation has a negative impact on the long-term quality of both policy design and practical implementation. In Kosovo, while there is a requirement for government-funded grants to be monitored and evaluated, this information is not shared or collated at the system level. This means that there is also no mapping or sharing of proven good practices, and that performance data cannot be used to adapt or inform new funding decisions. In Serbia, where there is evidence of evaluation of training provision, there is a lack of gender-disaggregated data throughout the process and little co-ordination to collate results, limiting the economy’s capacity to provide a more rounded picture of the impact of multiple actions in the SME policy sphere. Understanding the reach, efficacy and impact of actions is vital for the ongoing development and implementation of S3, as well as the new national skills frameworks being established in Albania, Kosovo and Turkey.

The way forward for enterprise skills

Act urgently to upgrade skills intelligence. A lack of skills intelligence on current and future supply and demand makes it difficult to set priorities across education, labour market and industry policy areas to shape enterprise skills provision. Consideration should be given to harmonising national skills intelligence frameworks with the permanent online skills intelligence platform being developed as a flagship action of the European Skills Agenda16 and the European Skills Index led by Cedefop.17

Mainstream SME skills, including the gender perspective, into smart specialisation strategy development and implementation. SME skills development needs should be considered a cross-cutting action area within S3. This will support both S3 priority domains and associated value chains at national and local levels, equipping them with the skills, including reskilling and upskilling, to support the changing nature of the economy as S3 domains develop and grow. The gender impact of this discovery process should be included, with some practical steps, as illustrated in Box 9.2.

Box 9.2. Promoting gender mainstreaming through smart specialisation in Värmland, Sweden

The region of Värmland developed a regional smart specialisation strategy (S3) and took an explicit decision to design a strategy that created sustainable and inclusive growth. To achieve this, it re‑interpreted the purpose of smart specialisation to reflect its commitment. Its vision became: “Smart specialisation is a smart way to organise and develop existing regional assets in order to create value for users and society.” While the starting point was to create an innovation strategy for business, the goal evolved into a gender-mainstreamed innovation strategy for smart specialisation. Gender mainstreaming at every stage of the S3 process was included due to the nature of the industry in the region, reflecting the economic reality that the primary industries (pulp and paper, steel, and engineering) were male-dominated and thus the labour market is heavily gender-segregated. It was regarded as a positive societal benefit that could be integrated as a planned outcome of the smart specialisation process through its design and implementation.

This was the first time that gender had been considered so comprehensively within S3, and the process was undertaken with support from the EU Joint Research Centre Smart Specialisation team as well as a local university with expertise in gender studies. Key areas where gender mainstreaming was applied were to:

implement statistical analysis of the gender structure of the labour market

apply a gender-equality perspective throughout the mapping process, bringing not only an awareness of gender in all aspects, but also the ambition to work towards a more gender-equal innovation and business climate in the region

assess the likely gender impacts of the decisions taken in strategy, to more fully understand the consequences that different decisions have on women, men, girls and boys, and to use this understanding to decide how best to achieve inclusive, sustainable growth

consider how to further gender equality within the priority economic domains by exploring how to shape them to attract more women employees and identify potential areas of innovation within priority sectors that can assist in gender mainstreaming as a societal benefit.

Gender inequality is prevalent and multi-faceted across all economies. To embrace gender equality at the heart of smart specialisation would advance the ambitions of all economies to decrease gender inequality. This is particularly pertinent due to of the emphasis in all economies on the development of S3. For Montenegro and Serbia, this example may provide added ideas for reflection during the next stages of S3 development and implementation.

Sources: European Commission (n.d.[16]); Thinking Smart (2015[17]); Region of Varmlands (2015[18]).

Place a priority on training for SMEs that will support the green transition, in particular opening up the relevance of the circular economy across all sectors. The current low level of training provision needs to be expanded if the opportunities for green growth are to be exploited for both social and economic impact. Inspiration can be taken from actions recommended through the European Circular Economy Action Plan (European Commission, 2020[19]), such as recycling businesses, circularity in industrial processes, digital technologies for tracking resources or working with other enterprises to develop cluster collaborations, or the selection of actions in the Eurochambres guidance (Eurochambres, 2020[20]).

Establish comprehensive monitoring and evaluation of all programmes related to SME skills, including a strong gender focus and fully gender-disaggregated data. A high-quality and co-ordinated approach to monitoring and evaluation is needed to document progress and impact. This work should be supported by consistent, gender-disaggregated data gathered from government-financed SME support and training actions. It should inform a gender impact assessment of the current approaches to enterprise skills and support. This will address and seek solutions for the current challenges faced by women across the labour market and entrepreneurship. For more information on data that WBT governments could consider collecting in this area, please see Annex C.

References

[7] ALLED2 (2019), ALLED2: VET Barometer, http://alled.eu/sr/sadasnje-stanje-u-profesionalnom-obrazovanju-i-osposobljavanju/.

[2] Bacigalupo, M. et al. (2016), EntreComp: The Entrepreneurship Competence Framework, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC101581.

[15] Bolognini, A. (2021), Montenegro: EU Support for Innovation Strategies and Policy, Economisti Associati information, Bologna, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/system/files/2021-09/20210716%20MNE%20eval%20CS%203%20Innovation.pdf.

[22] EC (2016), A New Skills Agenda for Europe: Working Together to Strenghten Human Capital, Employability and Competitiveness, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2016/EN/1-2016-381-EN-F1-1.PDF.

[25] EC (2014), Statistical Data on Women Entrepreneurs in Europe, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/growth/content/study-statistical-data-women-entrepreneurs-europe-0_en.

[21] EC (2013), Entrepreneurship 2020 Action Plan: Reigniting the Entrepreneurial Spirit in Europe, European Commission, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0795.

[20] Eurochambres (2020), Chambers for a Circular Economy, Eurochambres, https://www.eurochambres.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/9-Chambers_for_a_Circular_Economy.pdf.

[4] European Commission (2021), “2021 economic reform programmes of Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo”, European Economy Institutional Papers, No. 158, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/2021-economic-reform-programmes-albania-montenegro-north-macedonia-serbia-turkey-bosnia-and-herzegovina-and-kosovo-commissions-overview-and-country-assessments_en (accessed on 30 January 2022).

[9] European Commission (2021), “Commission presents Action Plan to boost the social economy and create jobs”, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=10117&furtherNews=yes#navItem-1 (accessed on 15 April 2022).

[29] European Commission (2021), European Pillar of Social Rights Action Plan, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/economy-works-people/jobs-growth-and-investment/european-pillar-social-rights/european-pillar-social-rights-action-plan_en (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[8] European Commission (2020), A New Industrial Strategy for Europe, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/europe-fit-digital-age/european-industrial-strategy_en (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[27] European Commission (2020), An SME Strategy for a sustainable and digital Europe, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-sme-strategy-march-2020_en.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[19] European Commission (2020), Circular Economy Action Plan, European Commission, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:9903b325-6388-11ea-b735-01aa75ed71a1.0017.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

[28] European Commission (2020), Digital Education Action Plan 2021-2027: Resetting education and training for the digital age, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0624&from=EN (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[3] European Commission (2020), European Skills Agenda for Sustainable Competitiveness, Social Fairness and Resilience, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=22832&langId=en.

[13] European Commission (2020), Green Agenda for the Western Balkans, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/system/files/2020-10/green_agenda_for_the_western_balkans_en.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2022).

[12] European Commission (2019), The European Green Deal, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-green-deal-communication_en.pdf.

[16] European Commission (n.d.), Smart Specialisation Platform, https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 17 June 2022).

[24] European Committee of the Regions (2018), Asturias (Spain), Gelderland (Netherlands) and Thessaly (Greece) win European Entrepreneurial Region Award 2019, European Committee of the Regions website, https://cor.europa.eu/en/news/Pages/Entrepreneurial-Region-Award-2019-.aspx.

[30] European Parliament (2019), Women’s Rights in Western Balkans, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/608852/IPOL_STU(2019)608852_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[23] European Parliament (2013), “Women’s entrepreneurship in the EU”, Library Briefing, Library of the European Parliament, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/bibliotheque/briefing/2013/130517/LDM_BRI(2013)130517_REV1_EN.pdf.

[5] Government of Kosovo (n.d.), Kosovo Labour Market Barometer, https://sitp.rks-gov.net/.

[14] Government of Turkey (2021), Green Deal Action Plan, https://storage.googleapis.com/cclow-staging/ex22dd26gvlqapd56dr32qnzs28w?GoogleAccessId=laws-and-pathways-staging%40soy-truth-247515.iam.gserviceaccount.com&Expires=1650489369&Signature=mCz8sB%2F4mhuEyEUAJRmhA8y2Hf5dKskEK0hmIMOaRk1JJ2aNM2%2FkZka6zOP8Ecce (accessed on 19 April 2022).

[34] Gribben, A. (2018), “Tackling policy frustrations to youth entrepreneurship in the Western Balkans”, Small Enterprise Research, Vol. 25/2, pp. 183-191, https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2018.1479294.

[6] Institute for Entrepreneurship and Small Business (2021), Alled EU: Kosovo Skills Barometer, http://alled.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Kosovo-Skill-Barometer.pdf.

[26] OECD (2016), “Policy Brief on Women’s Entrepreneurship”, https://doi.org/10.2767/50209.

[35] OECD et al. (2016), SME Policy Index: Western Balkans and Turkey 2016: Assessing the Implementation of the Small Business Act for Europe, SME Policy Index, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264254473-en.

[18] Region of Varmlands (2015), Background Varmlands RIS3, https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/documents/20125/302041/b1fcc5c0-1e61-41c0-bb1c-9f8ebca868dd.pdf/da731b93-2e06-b969-ede4-ec44519325cd?version=1.1&t=1619530325095 (accessed on 17 June 2022).

[10] Rosandić, A. (2018), European Commission DG Near Synthesis Report: Social Economy in Eastern Neighbourhood and in the Western Balkans, https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/29642/attachments/15/translations/en/renditions/native (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[11] Rural Development Network of North Macedonia (2020), The Green Economy in the Western Balkans, http://brd-network.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-Green-Economy-in-the-Western-Balkans-Analysis-best-practices-and-recommendations_.pdf.

[17] Thinking Smart (2015), Promoting Gender Mainstreaming through Smart Specialisation, https://thinkingsmart.utad.pt/content/promoting-gender-mainstreaming-through-smart-specialisation (accessed on 17 June 2022).

[31] United Nations (2020), Achieving SDG Indicator 5.a.2 in the Western Balkans and beyond, https://www.giz.de/en/downloads_els/ORF%20Legal%20Reform%20-%20%20FAO%20-%20Achieving%20SDG%20Indicator%205.a.2%20in%20the%20Western%20Balkans%20and%20Beyond.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

[33] World Bank (2021), Western Balkans Regular Economic Report: Greening the Recovery, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/36402/Greening-the-Recovery.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 30 January 2022).

[1] World Bank (2020), Western Balkans Labor Market Trends 2020, World Bank Washington, DC, https://wiiw.ac.at/western-balkans-labor-market-trends-2020-dlp-5300.pdf.

[32] World Bank (2018), Promoting women’s access to economic opportunities in the Western Balkans: building the evidence, https://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/862651521147002998/PPT-Gender-TF-final.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2022).

Notes

← 1. See: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:d32825b0-08ad-11eb-a511-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

← 2. See: https://sitp.rks-gov.net. The Labour Market Barometer automatically collates real-time data from the following statistical sources:

1. Employment Agency of the Republic of Kosovo

2. Kosovo Agency of Statistics

3. Tax Administration of Kosovo

4. Civil Registration Agency

5. Ministry of Education and Science

6. Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare

7. Ministry of Internal Affairs

8. Business Registration Agency

9. Agency for Vocational Education and Training and Adult Education

10. University of Pristina

11. Kosovo Accreditation Agency

12. National Qualification Authority

← 6. For more information, see: https://trzisterada.ba.

← 7. For more insight, see: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/cedefop-links-gender-equality-better-skills-systems.

← 8. See: https://boostmeup.me.

← 9. For more information, see: www.restart.how.

← 10. For more information on the Global Innovation Index 2021 see: https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2021.pdf.

← 11. For the European Commission definition and description of social economy businesses, see: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/proximity-and-social-economy/social-economy-eu_en#:~:text=The%20social%20economy%20encompasses%20a,and%20pursuing%20a%20social%20cause.

← 12. For more insights and access to European Commission research and economy reports, see: https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=8274 and https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/29642/attachments/15/translations/en/renditions/native.

← 13. For more information on this research led by the British Council, see: https://www.britishcouncil.org.tr/en/programmes/education/social-enterprise-research

← 14. The current S3 platforms can be accessed at:

Kosovo: https://smartkosova.rks-gov.net

Montenegro: https://www.s3.me/en

Serbia: https://pametnaspecijalizacija.mpn.gov.rs/s3-u-srbiji

← 15. There is no evidence of gender-sensitive approaches within smart specialisation strategies that are already established in Montenegro and Serbia.

← 16. See action 2 of the European Skills Agenda (European Commission, 2020[3]).

← 17. For more information regarding the European Skills Index see: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/projects/european-skills-index-esi.