Total public spending on education (from primary to tertiary level) averages 10.6% of total government expenditure across OECD countries, from around 7% to 17%. The largest share of government funding is devoted to primary and secondary levels, explained by near-universal enrolment rates at those levels of education and the greater contribution of private sources at tertiary level.

Between 2015 and 2019, the proportion of government expenditure devoted to education fell slightly on average across OECD countries (about 1%). This is explained by total government expenditure increasing faster (11%) than the increase in expenditure for education (9%). Data from the Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) suggest that the gap will widen further in 2020, with the COVID-19 pandemic pushing governments to spend more to support their economies.

Spending on tertiary education is highly centralised, with 87% of final public funds coming from the central level on average across OECD countries. In contrast, only an average of 44% of final public expenditure devoted to non-tertiary education comes from the central level.

Education at a Glance 2022

Indicator C4. What is the total public spending on education?

Highlights

1. Year of reference differs from 2019. Refer to the source table for more details.

2. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

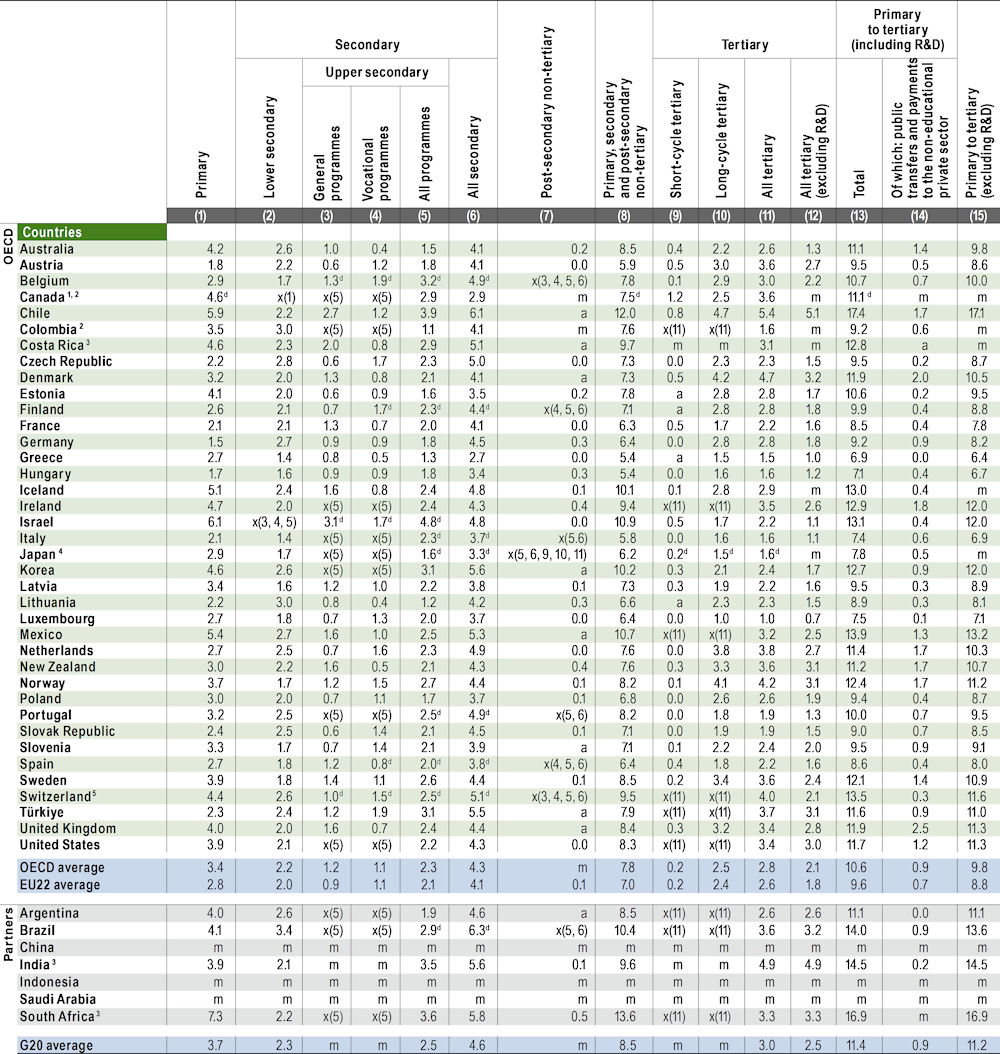

Countries are ranked in descending order of total public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C4.1. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Context

Public expenditure enables governments to serve a wide range of purposes, including providing education and health care and maintaining public order and safety. Decisions concerning budget allocations to different sectors depend on countries’ priorities and the options for private provision of these services. Education is one area in which all governments intervene to fund or direct the provision of services. As there is no guarantee that markets will provide equal access to educational opportunities, government funding of educational services is necessary to ensure that education is not beyond the reach of some members of society.

Policy choices or external shocks, such as demographic changes or economic trends, can have an influence on how public funds are spent. Like the financial crisis in 2008, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affected societies economically, and education is one of the sectors hit (Box C4.1 and Box C4.2). Past economic crises have put pressure on public budgets, resulting in less public funding being allocated to education in some countries. Budget cuts can represent improved allocation of government funds and may generate gains in efficiency and economic dynamism, but they can also affect the quality of government-provided education, particularly at a time when investment in education is important to support learning acquisition and economic growth.

This indicator compares total public spending on education with total government expenditure across OECD and partner countries. This indicates the priority placed on education relative to other public areas of investment, such as health care, social security, defence and security. It also includes data on the different sources of public funding in education (central, regional and local governments) and transfers of funds between these levels of government. Finally, it also covers how public expenditure has changed over time.

Other findings

On average across OECD countries, the tertiary level accounted for 27% of total public expenditure on education. The share is the lowest in Luxembourg (14%) due to the significant share of national tertiary students who are enrolled abroad.

While public expenditure on education does not exceed 8% of gross domestic product (GDP) in any OECD country, about one in ten OECD countries with available data for 2019 reported that total government expenditure accounted for more than 50% of GDP.

Among OECD countries with available COFOG data, total government expenditure increased by an unprecedented 10.9% between 2019 and 2020 on average, even after controlling for inflation. In comparison, the increase in public expenditure on education was only 1.4%, showing that governments needed to invest more heavily in other sectors, such as the economy and the health sector.

Analysis

Public resources invested in the different levels of education

In 2019, total public expenditure on primary to tertiary education as a percentage of total government expenditure for all services averaged 10.6% in OECD countries. However, this share varies across OECD and partner countries, ranging from around 7% in Greece, Hungary and Italy to over 17% in Chile (Table C4.1 and Figure C4.1).

Overall, significant government funding was devoted to non-tertiary levels of education in 2019. In most countries, and on average across OECD countries, roughly three-quarters of total public expenditure on primary to tertiary education (about 8% of total government expenditure) was devoted to non-tertiary education (i.e. primary, secondary and post-secondary non-tertiary education) (Table C4.1 and Figure C4.1). This is largely explained by the near-universal enrolment rates at non-tertiary levels of education (see Indicator B1), the shorter duration of tertiary education relative to the combined length of primary and secondary education, and the fact that in OECD countries, on average, the funding structure of tertiary education depends more on private sources than it does at non-tertiary levels.

The share of total public expenditure devoted to tertiary education varies widely among countries. On average across OECD countries, total public expenditure on tertiary education, including expenditure on research and development, amounted to 27% of total public expenditure on primary to tertiary education. Across OECD and partner countries, the share ranges from below 14% in Luxembourg to over 37% in Austria and Denmark (Table C4.1 and Figure C4.1). In Luxembourg, over three-quarters of national tertiary students are enrolled abroad (see Indicator B6), explaining the low share of public expenditure devoted to tertiary education.

Early childhood education (ECE) is generally excluded from statistics on the total public expenditure on education because of the very diverse nature of systems across OECD countries. There are variations in the targeted age groups, the governance structures, the funding of services, the type of delivery (full-day versus part-day attendance) and the location of provision, whether in centres or schools, or at home (see Indicator B2). On average across OECD countries with data, ECE represents 1.7% of total government expenditure, ranging from 0.3% in Japan to 3.8% in Chile. The varying nature of the organisation of ECE systems can help explain this wide range. In all OECD countries with data, except in Denmark and Norway, expenditure on pre-primary education exceeds the expenditure devoted to early childhood educational development (Table C4.1, available on line).

When considering public expenditure on education as a share of total government expenditure, the relative sizes of public budgets overall should also be taken into account. The share of total government expenditure as a proportion of GDP varies greatly among countries (Table C4.1, available on line). In 2019, about one in ten countries with available data reported that their total government expenditure on all services amounted to more than 50% of GDP. A large share of total government expenditure devoted to public expenditure on education does not necessarily translate into a high share relative to a country’s GDP. For example, Ireland allocates 12.9% of its total government expenditure towards primary to tertiary education (more than the OECD average of 10.6%), but total public expenditure on education as a share of GDP is relatively low (3.1% compared to the OECD average of 4.4%). This can be explained by Ireland’s relatively low total government expenditure as a share of GDP (24.2%) (Table C4.1, available on line).

Sources of public funding invested in education

The division of responsibility for education funding across levels of government (central, regional and local) is an important element of education policy. Decisions on education funding are taken both at the level of government where the funds originate, and at the level of government where they are ultimately spent. The originating level of government decides on funding amounts and imposes conditions on the use of funds. The ultimate spending level of government has varying amounts of discretion over how funds are spent.

Education funding may be mostly centralised or decentralised with funds transferred between levels of government. High levels of centralisation can cause delays in decision making and decisions that are taken far from those affected can also fail to address the local needs. In highly decentralised systems, however, different units of government may differ in the level of educational resources they spend on students, either due to differences in priorities related to education or to differences in their ability to raise funding. Wide variations in educational standards and resources can also lead to unequal educational opportunities and insufficient attention being paid to long‑term national requirements.

Many schools have become more autonomous and decentralised, as well as more accountable to students, parents and the wider public for their outcomes. The results of the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) suggest that when autonomy and accountability are appropriately combined, they tend to be associated with better student performance (OECD, 2016[1]).

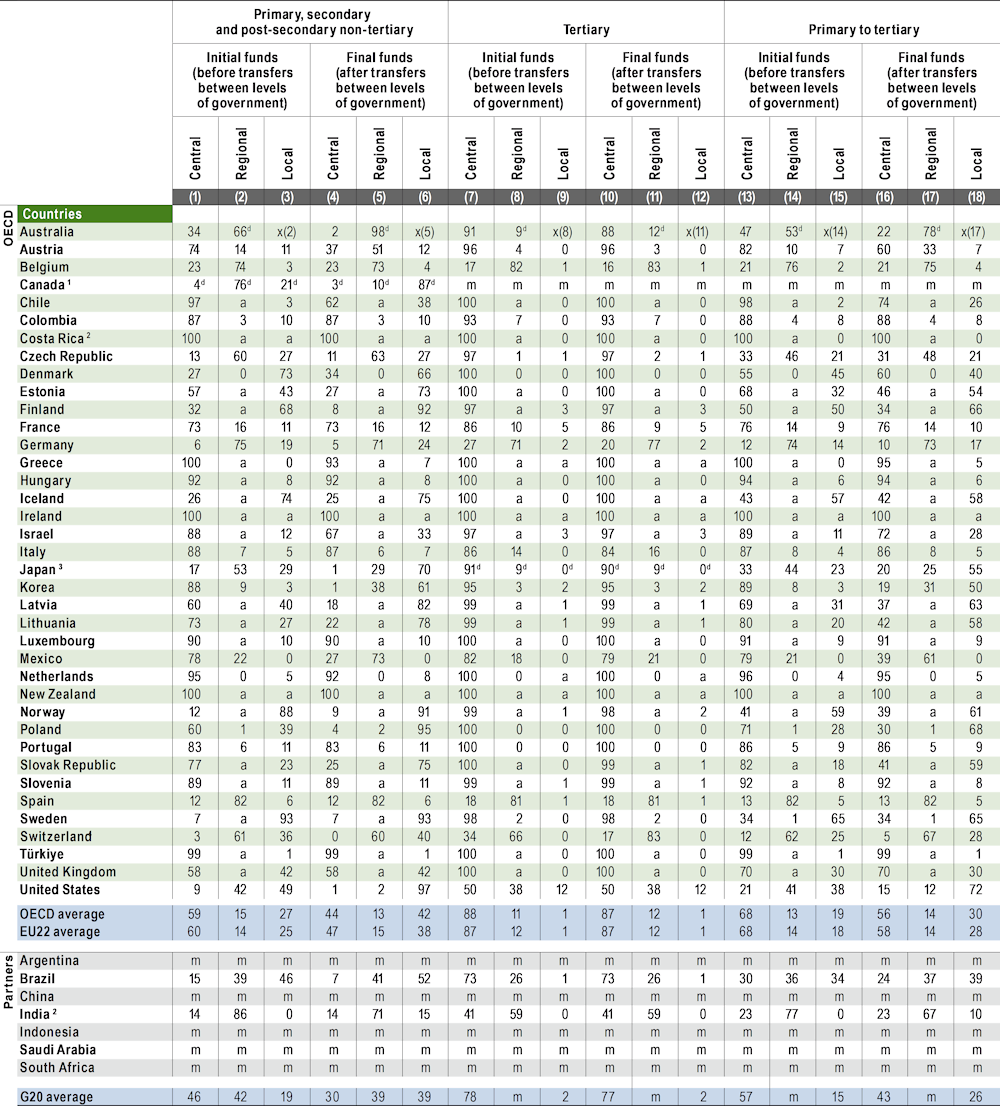

The government levels responsible for funding education differ at different levels of education. Typically, public funding is more centralised at the tertiary level than at lower levels of education. In 2019, on average across OECD countries, 59% of public funds for non-tertiary education came from the central government before transfers to the various levels of government, compared to 88% of public funds for tertiary education (Table C4.2 and Figure C4.2). While a large share of central government funds for primary and secondary education are transferred to lower levels of government, barely any funding for tertiary education is transferred in this way. In most OECD and partner countries with available data, central government directly provides more than 60% of public funds in tertiary education; in nine out of ten countries, the central government is the main source of both initial and final funding. In contrast, Spain, as well as federal countries such as Belgium, Germany and Switzerland source over 60% of tertiary-level funding from regional governments with little or nothing transferred down to local governments. Local authorities typically do not have an important role in financing tertiary education, representing only 1% of initial and final public funds on average, with the exception of the United States where local governments provide 12% of total expenditure to this level (Figure C4.2).

1. Year of reference differs from 2019. Refer to the source table for more details.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the share of initial sources of funds from the central level of government.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C4.2. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

More funds are transferred from central to regional and local levels of government for non-tertiary education. On average across OECD countries, the share of public funds for non-tertiary education provided by the central government falls from 59% to 44% after transfers to other levels of government have been accounted for, while the resulting share of local funds rises from 27% to 42%. There is a great deal of variation in how much the sources of funds change before and after transfers from central to lower levels of government. In Korea, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland and the Slovak Republic, the difference is more than 50 percentage points after transfers to regional and local governments. In Australia, Austria, Chile and Latvia, the difference is more than 30 percentage points. In Canada and the United States, where the regional level is mostly responsible for transferring funds to schools, the share of regional funding falls by 40 percentage points or more after transfers to local levels of government (Table C4.2).

Trends in public expenditure on education, 2015-19

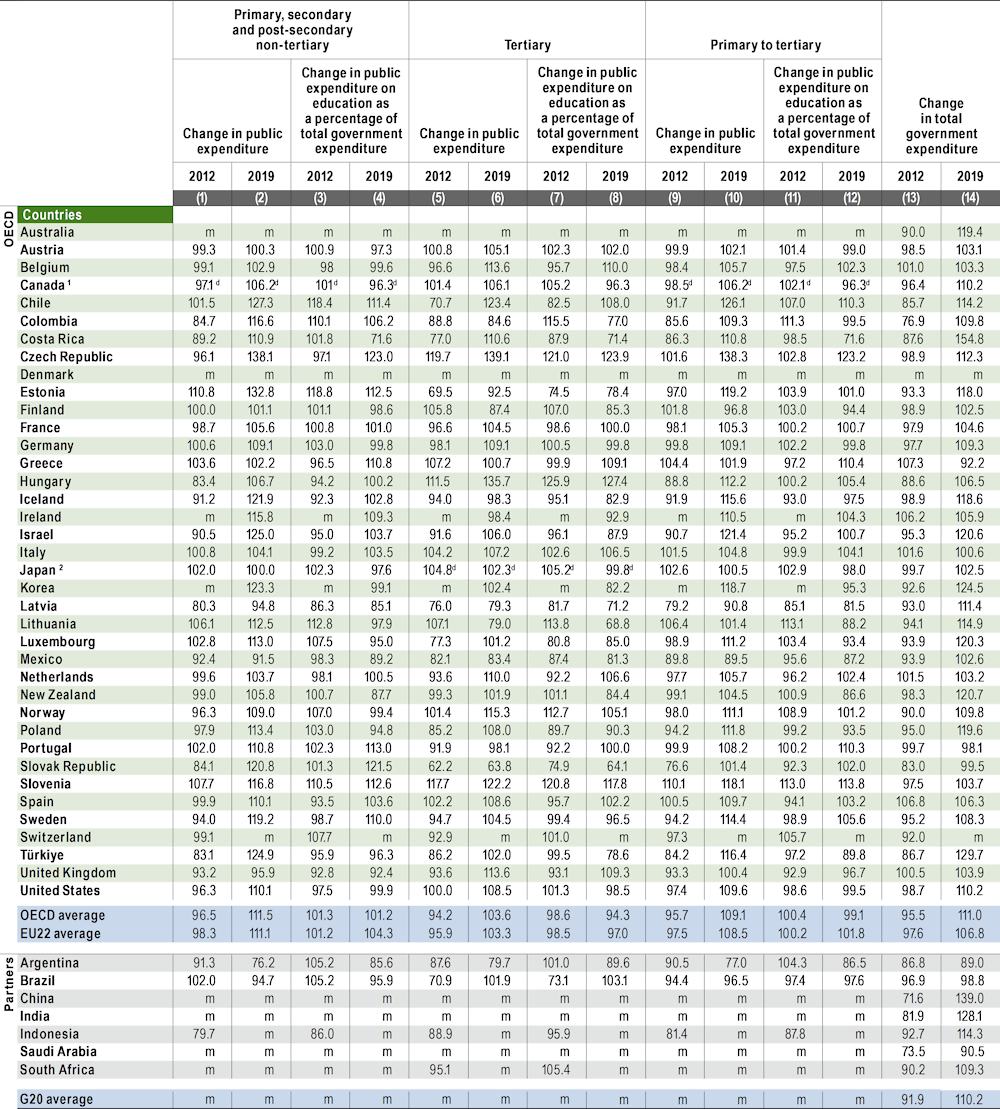

Between 2015 and 2019, total public spending on primary to tertiary education increased by 9% on average across OECD countries. In some countries, changes in expenditure were similar between non-tertiary and tertiary education levels. For example, in Canada, Costa Rica and Germany, the relative increases in expenditure for non-tertiary and tertiary levels were almost the same over that period. Although the relative increases in education expenditure mirrored changes in total government expenditure in Canada and Germany, this was not the case in Costa Rica. There, public education expenditure increased by 11% while total government expenditure increased by 55% during 2015-19. In countries such as Colombia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic, changes in expenditure diverged by level of education, with tertiary education expenditure falling by at least 8%, while expenditure on primary to post-secondary non-tertiary education rose by at least 12%. In contrast, in Chile, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovenia, public expenditure on tertiary education increased by more than 20% between 2015 and 2019, the largest increase across OECD countries (Figure C4.3).

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the change in total public expenditure on tertiary education between 2015 and 2019.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022), Table C4.3. See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

It is difficult to find a simple explanation for the different changes in expenditure over time across OECD countries. For example, in Hungary and Slovenia, demographic changes leading to a falling tertiary student population might have been expected to lead to decreases in expenditure on tertiary education, rather than these continuing large increases in expenditure. On the other hand, despite these changes, spending per full-time tertiary student in Hungary and Slovenia remain below the OECD average (see Indicator C1). In Hungary, the increases in public expenditure on tertiary education might have been driven by the government’s 2014 Higher Education Strategy which outlines several commitments to expand higher education infrastructure through transforming former colleges into universities and building higher education centres in remote areas (OECD, 2017[2]). Indeed, in 2019, Hungary had one of the highest shares of capital expenditure compared to current expenditure among OECD countries, and capital expenditure per student (USD 2 100) was higher than the OECD average (USD 1 600) (See Indicator C6). Divergence in expenditure by level of education may be influenced by both demographic trends leading to changes in student enrolment as well as funding structures between governments and educational institutions. For example, in the Slovak Republic, the mechanism through which the government allocates funding to tertiary education institutions plays a key role in the changes observed during this time period. Since school budget allocations rely on the number of students and graduates, public expenditure for tertiary institutions has declined with the falling tertiary student population as a result of both demographic changes as well as domestic students choosing to study abroad (OECD, 2021[3]).

Between 2015 and 2019, the proportion of government expenditure devoted to primary to tertiary education fell by 0.9% on average across OECD countries. Although public spending on education increased, it did not keep pace with the increase in total government expenditure of 11.0%. Despite this relative decline at aggregate level, in about half of the OECD and partner countries with available data for both years, public expenditure on education as a share of total government expenditure increased between 2015 and 2019, with the Czech Republic and Slovenia showing the largest increase (over 13%). In the remaining countries, the increase in public expenditure on education was smaller than the increase in government spending overall. The most notable examples are Costa Rica, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, New Zealand and Türkiye where the relative increase in total government expenditure was at least 10 percentage points higher than the increase in public expenditure on education (Table C4.3).

Box C4.1. Evolution of the expenditure on education during the COVID-19 pandemic

The economic crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the availability of public funding for education in OECD and partner countries. While the longer-term impact on education funding is still uncertain, some countries have implemented immediate financial measures to help students and education systems to cope with the disruptions and economic impact of school and university closures. The lack of preparedness for distance learning resulted in governments needing to invest in information and communication technologies (ICT) material and ICT-related teacher training to mitigate the negative impact of the pandemic on learners (OECD, 2021[4]). When schools reopened, their facilities were often ill-equipped to enable social distancing requirements to be respected, resulting in further investment to contain the epidemiological risk and improve the safety of students and teachers.

While there was a pressing need to support the transition to a new form of learning, the economy and the health sectors also needed significant governmental support. This box analyses the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education spending between 2019 and 2020, compared to the growth in total government expenditure over the same period. Data from COFOG are available for the reference year 2020, allowing for comparison with pre-crisis expenditure levels. Future editions of Education at a Glance will be able to provide evidence on this in greater detail once data from the UNESCO, OECD and Eurostat (UOE) data collections become available for the pandemic period. The COFOG data presented in this box can only provide a first impression of trends and are not fully comparable to other data in this chapter due to some differences in the underlying statistical concepts of the COFOG and UOE data collections (Eurostat, 2019[5]). For example, COFOG covers non-formal education whereas UOE collects only formal education, so some adult education or continuing education programmes are included in COFOG, but excluded from UOE.

1. Canadian COFOG data adjusted in 2015 constant prices: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1010000501.

2. Provisional data.

Countries are ranked in descending order of the change in government expenditure devoted to education between 2019 and 2020.

Source: OECD (2022), Government expenditure by function (COFOG), https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE11.

On average, across OECD countries with available COFOG data, total government expenditure increased by 11% between 2019 and 2020, even after controlling for inflation (Figure C4.4). In comparison, the increase was only 3% between 2018 and 2019. The increase during the COVID-19 crisis is largely due to subsidies provided in the context of job retention schemes. During the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, job retention schemes supported approximately 60 million jobs across OECD countries, more than ten times as many as during the global financial crisis (OECD, 2021[6]). This explains why the increase in total government expenditure was larger than the increase in education expenditure for all OECD countries with data. For example, in Lithuania, where the increase in education expenditure was the highest (+11.7%), the increase in total government expenditure was even larger (+23.2%). Although COVID-19 dominated the public debate, changes in government expenditure between 2019 and 2020 are not solely linked to the pandemic; countries continued or even accelerated reforms in a number of sectors. The future will tell how this disruption and sudden changes in public expenditure will affect education policies and learning achievements in the long run.

Box C4.2. Education support measures affecting public budgets during the COVID-19 crisis

During the school closures and the reopening that followed, the measures taken across OECD countries to support teaching and learning varied. However, the results of the 4th wave of the Survey on Joint National Responses to COVID-19 show some common ground across many countries (see COVID chapter). The survey asked countries which of the following six measures they had taken due to COVID-19 to support education which had a direct impact on the public education budget:

recruitment of temporary teachers and/or other staff

additional bonuses for teachers

additional bonuses for other staff

additional support for teachers/staff: funding masks, COVID-19 tests, health care, etc.

discounts on schools meals (or free meals)

investment into infrastructure to improve the sanitary conditions (e.g. installation of air filters in classrooms).

The possible answers were: yes, no, or schools/districts/the most local level of governance could decide at their own discretion.

Across the 29 countries and other participants with data for the school year 2020/21, only Mexico and the French Community of Belgium reported no additional funding for the provision of masks, COVID tests or other health-related expenses for primary and secondary education teachers or staff. Most countries reported that such support was provided on a systematic basis across schools, but in Canada, Finland, Sweden and United States, the support varied across schools or regions because the decisions were made at lower levels of authority. Most countries did not provide bonuses to teachers. France and Mexico are the only two countries that reported having a centralised policy of bonuses for teachers in tertiary education during the COVID-19 crisis. In the rest of the countries such bonuses were either non-existent at tertiary level or were at the discretion of lower levels of governance. At primary and secondary levels, France, the French Community of Belgium, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia provided bonuses for teachers. In Austria, additional bonuses were only provided to school heads and administrative staff in upper secondary schools.

Investment in infrastructure to improve sanitary conditions was widespread at primary and secondary levels across countries participating in the survey. Only Mexico, Portugal and Slovenia reported not providing additional financial support for such measures at these levels. In France, Iceland, Lithuania, Norway, Poland and the Slovak Republic, decisions about expenditure on infrastructure to improve sanitary conditions at primary and secondary levels were at the discretion of lower levels of governance, in contrast to funding for the provision of masks, COVID-19 tests or other health-related expenses, which was provided on a systematic basis. About half of countries recruited temporary teachers and/or other staff on a systematic basis to support education during COVID-19. Only 9 out of 29 countries with data did not resort to such means to support learning at primary and secondary levels. In contrast, discounted (or free) school meals was the second least widely adopted policy measure. At primary and secondary levels, only Colombia, Latvia, Portugal and England (United Kingdom) reported having provided these at the national level, while in Canada, Estonia, France, Japan, Lithuania and Sweden, the decision to provide discounts on school meals was decentralised.

In general, measures to support education during the COVID-19 pandemic were adopted much more widely at primary and secondary level than at tertiary level. For example, 79% of countries reported providing systematic support for teachers and staff to fund masks, COVID-19 tests and other healthcare expenses at primary and secondary level, compared to 44% at tertiary level. This may suggest that the additional spending engendered by the COVID-19 crisis has weighed differently on public budgets at different levels of education.

Definitions

Intergovernmental transfers are transfers of funds designated for education from one level of government to another. They are defined as net transfers from a higher to a lower level of government. Initial funds refer to the funds before transfers between levels of government, while final funds refer to the funds after such transfers.

Public expenditure on education covers expenditure on educational institutions and expenditure outside educational institutions such as support for students’ living costs and other private expenditure outside institutions, in contrast to Indicators C1, C2 and C3, which focus only on spending on educational institutions. Public expenditure on education includes expenditure by all public entities, including the education ministry and other ministries, local and regional governments, and other public agencies. OECD countries differ in the ways in which they use public money for education. Public funds may flow directly to institutions or may be channelled to institutions via government programmes or via households. Public funds may be restricted to the purchase of educational services or may be used to support students’ living costs.

All government sources of expenditure on education, apart from international sources, can be classified under three levels of government: 1) central (national) government; 2) regional government (province, state, Bundesland, etc.); and 3) local government (municipality, district, commune, etc.). The terms “regional” and “local” apply to governments with responsibilities exercised within certain geographical subdivisions of a country. They do not apply to government bodies with roles defined in terms of responsibility for particular services, functions or categories of students that are not geographically circumscribed.

Total government expenditure corresponds to non-repayable current and capital expenditure on all functions (including education) of all levels of government (central, regional and local), including non-market producers (e.g. providing goods and services free of charge, or at prices that are not economically significant) that are controlled by government units, and social security funds. It does not include expenditure derived from public corporations, such as publicly owned banks, harbours or airports. It includes direct public expenditure on educational institutions (as defined above), as well as public support to households (e.g. scholarships and loans to students for tuition fees and student living costs) and to other private entities for education (e.g. subsidies to companies or labour organisations that operate apprenticeship programmes).

Methodology

Figures for total government expenditure and GDP have been taken from the OECD National Accounts Statistics Database (see Annex 2).

Public expenditure on education is expressed as a percentage of a country’s total government expenditure. The statistical concept of total government expenditure by function is defined by the National Accounts’ Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG). There are strong links between the COFOG classification and the UNESCO, OECD and Eurostat (UOE) data collection, although the underlying statistical concepts differ to some extent (Eurostat, 2019[5]).

Expenditure on debt servicing (e.g. interest payments) is included in total government expenditure, but it is excluded from public expenditure on education, because some countries cannot separate interest payments for education from those for other services. This means that public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure may be underestimated in countries in which interest payments represent a large proportion of total government expenditure on all services.

For more information, please see the OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018 (OECD, 2018[7]) and Annex 3 for country-specific notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Source

Data refer to the financial year 2019 (unless otherwise specified) and are based on the UNESCO, OECD and Eurostat (UOE) data collection on education statistics administered by the OECD in 2021 (for details see Annex 3 at: (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf). Data from Argentina, China, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and South Africa are from the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS).

The data on expenditure for 2012-19 were updated based on a survey in 2021-22, and expenditure figures for 2015-19 were adjusted to the methods and definitions used in the current UOE data collection.

References

[5] Eurostat (2019), Manual on Sources and Methods for the Compilation of COFOG Statistics: Classification of the Functions of Government, European Commission, Luxembourg, https://doi.org/10.2785/498446.

[3] OECD (2021), Improving Higher Education in the Slovak Republic, Higher Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/259e23ba-en.

[6] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[4] OECD (2021), The State of School Education: One Year into the COVID Pandemic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/201dde84-en.

[7] OECD (2018), OECD Handbook for Internationally Comparative Education Statistics 2018: Concepts, Standards, Definitions and Classifications, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264304444-en.

[2] OECD (2017), “Overview of the Hungarian higher education system”, in Supporting Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Higher Education in Hungary, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264273344-6-en.

[1] OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

Indicator C4 tables

Tables Indicator C4. What is the total public spending on education?

|

Table C4.1 |

Total public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure (2019) |

|

Table C4.2 |

Distribution of sources of total public funds devoted to education, by level of government (2019) |

|

Table C4.3 |

Index of change in total public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure (2012 and 2019 |

Cut-off date for the data: 17 June 2022. Any updates on data can be found on line at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-data-en. More breakdowns can also be found at http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

Table C4.1. Total public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure (2019)

Initial sources of funds, by level of education

Note: The public expenditure presented in this table includes both public transfers and payments to the non-educational private sector which are attributable to educational institutions, and those to households for living costs, which are not spent in educational institutions. Therefore, the figures presented here (before transfers) exceed those for public spending on institutions found in Indicators C1, C2 and C3. Data on public expenditure on early childhood education (Columns 16 to 18) and on public expenditure as a share of GDP (Columns 19 to 22) are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2. Post-secondary non-tertiary figures are treated as negligible.

3. Year of reference 2020.

4. Data do not cover day care centres and integrated centres for early childhood education.

5. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader’s Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table C4.2. Distribution of sources of total public funds devoted to education, by level of government (2019)

Percentage of total government expenditure, before and after transfers, by level of education

Note: Some levels of education are included with others. Refer to "x" code in Table C4.1 for details. Data on early childhood education (Columns 19 to 36) are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2. Year of reference 2020.

3. Data do not cover care centres and integrated centres for early childhood education.

4. Year of reference 2018.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader’s Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.

Table C4.3. Index of change in total public expenditure on education as a percentage of total government expenditure (2012 and 2019)

Initial sources of funds, by level of education and year; reference year 2015 = 100, constant prices

Note: The public expenditure presented in this table includes both public transfers and payments to the non-educational private sector which are attributable to educational institutions, and those to households for living costs, which are not spent in educational institutions. Therefore, the figures presented here (before transfers) exceed those for public spending on institutions found in Indicators C1, C2 and C3. Data on early childhood education (Columns 15 to 26) are available for consultation on line (see StatLink below). See Definitions and Methodology sections for more information. Data and more breakdowns available at: http://stats.oecd.org, Education at a Glance Database.

1. Primary education includes pre-primary programmes.

2. Data do not cover day care centres and integrated centres for early childhood education.

Source: OECD/UIS/Eurostat (2022). See Source section for more information and Annex 3 for notes (https://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/EAG2022_X3-C.pdf).

Please refer to the Reader’s Guide for information concerning symbols for missing data and abbreviations.