Policy choices or external shocks, such as demographic changes or economic crises, can influence the allocation of public funds across sectors. The COVID-19 crisis has disrupted education on an unprecedented scale. Maintaining learning continuity amid school closures and ensuring schools reopened safely, all required additional financial resources beyond those budgeted for prior to the pandemic. As the sanitary crisis evolved into an economic and social crisis, governments have had to take difficult decisions about the allocation of funds across sectors.

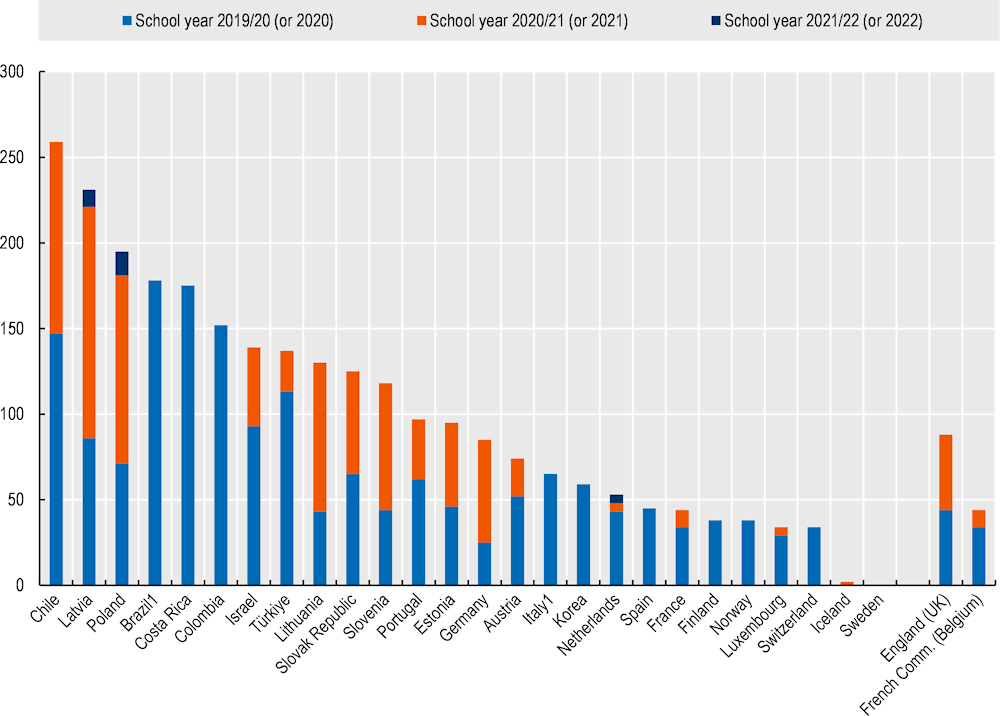

The results of previous survey (OECD, 2021[1]) showed that, during 2020, about two-thirds of OECD countries increased their education budgets in response to the pandemic, with the remaining one-third keeping spending constant. Public education spending continued to rise in 2021, which may reflect investment in measures to keep schools open. At least 75% of countries with available data increased the financial resources directed to primary, secondary and tertiary educational institutions compared to 2020 levels. The latest COVID-19 survey quantifies the amount of the budget increases, which helps to estimate whether the increases were sufficient. When the financial year 2021 is compared to the previous financial year, most countries reported moderate increases of 1-5% to their budgets for primary to upper secondary education, with only 10 out of 27 countries with available data reporting increases of 5% or more. Only Colombia reported moderate decreases to their public budgets between 2020 and 2021 (Table 1). Similar patterns exist for pre-primary and tertiary education. In some countries, these changes to public spending on education represent a break with pre-pandemic trends. In Colombia, for example, total government expenditure on education increased by 10% on average between 2015 and 2019 (Figure C4.3).

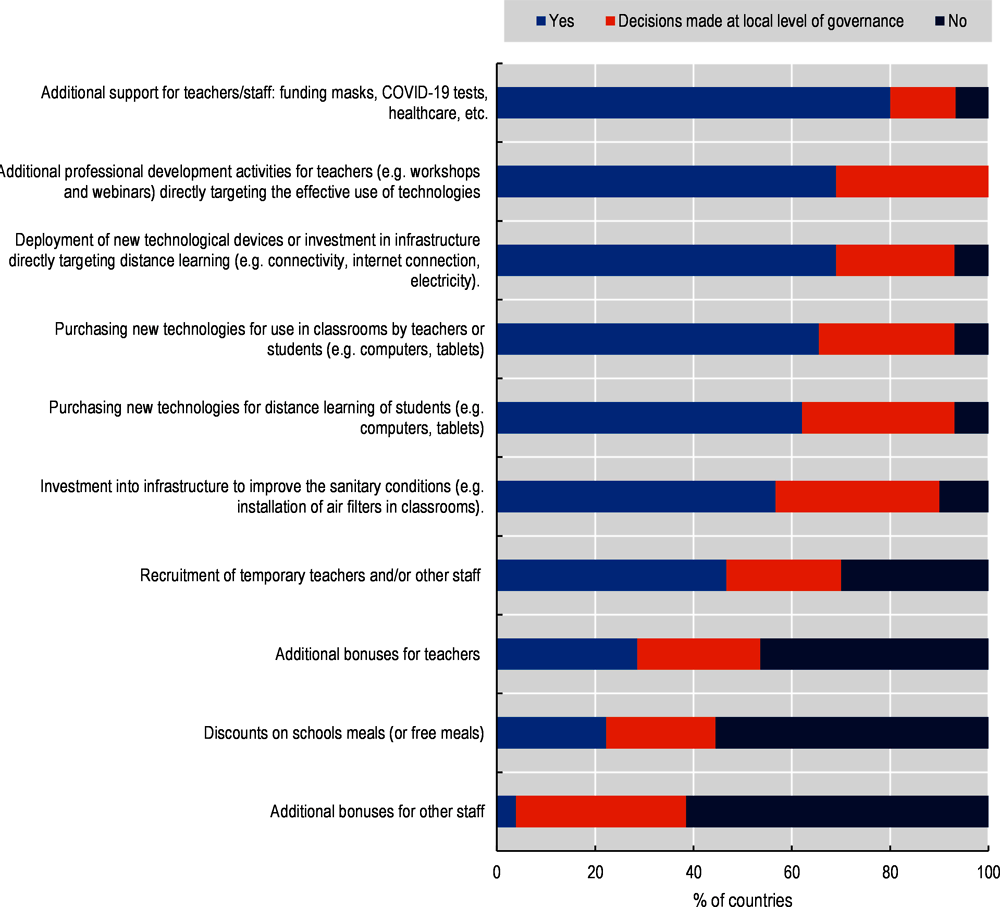

Responsibilities for spending decisions related to COVID-19 differed across levels of education in line with the general distribution of responsibilities across levels of government. At primary and secondary levels, policies were more likely to be adopted systematically for all schools, while at tertiary level, greater decentralisation meant measures might differ across institutions and universities. For example, at primary and secondary levels, 14 out of 30 countries reported hiring temporary staff at a national level in response to the pandemic for the school year 2020/21 (2021), while only 3 out of 26 countries reported having done so at the tertiary level. The decision to hire temporary staff was deferred to local authorities or schools in 7 countries at primary and secondary levels, and 10 countries at tertiary level (Table 1 and OECD COVID-19 database).

Spending to support teachers was common during the pandemic. The provision of masks, COVID-19 tests or other healthcare-related support was the most frequently adopted measure. At primary and secondary levels, 24 out of 30 countries invested in such measures in 2021, while a further 4 countries reported that these measures were left to the discretion of schools, districts or local levels of government. More than two-thirds of countries also invested in the professional development of teachers with a focus on developing digital skills in 2021. In 2022, the proportion of countries pursuing such policies on professional development of teachers had declined slightly, to 60%. Hiring temporary staff to ease the burden on teachers was less common (47% of countries in 2021 and 43% in 2022) and providing additional bonuses to teachers even less so (29% in 2021 and 28% in 2022). On the later, only 8 out of the 28 countries with data available – namely France, French Community of Belgium, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia, paid some or all teachers bonuses in 2021 to compensate for the challenges faced during the pandemic (Table 1, Figure 2 and OECD COVID-19 database).

Many children from low-income families rely on school meals to eat, but only a minority of countries reported providing discounted or free school meals during the COVID-19 crisis. Only 6 out of 27 countries with data available in 2021 reported additional expenditure on free or discounted school meals at the national level, while an additional 6 countries devolved those measures to the local level. Colombia is one of the few examples where meals were distributed to children who were not able to go to school, in some cases including nutritional support for the whole family. Along with Colombia, Chile, Latvia, Portugal, the United Kingdom and the United States were the other countries reporting additional expenditure on subsidised school meals at primary and secondary levels (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Many large countries devolved decisions on COVID-19 support measures to lower levels of authority. In Canada, Sweden and the United States most the measures implemented were at the discretion of provinces, municipalities, counties or states.