Despite national efforts to improve care integration, health systems remain fragmented when providing care across settings and providers. These failures have been magnified by the COVID‑19 pandemic, where poor co‑ordination between hospitals and community settings led to challenges in maintaining safe care (OECD, 2020[1]).

Policies for integrated care can improve patient outcomes and experiences. They also have the potential to increase value‑for-money by reducing duplicative and unnecessary care. Key mechanisms for improving integrated care rely on strengthening governance of care delivery, developing interoperable information systems, and aligning financial incentives across providers (OECD, 2017[2]). Indicators such as mortality, readmissions and medication prescriptions after hospitalisation provide insight into how well care is co‑ordinated across hospital and community care (Barrenho et al., 2022[3]).

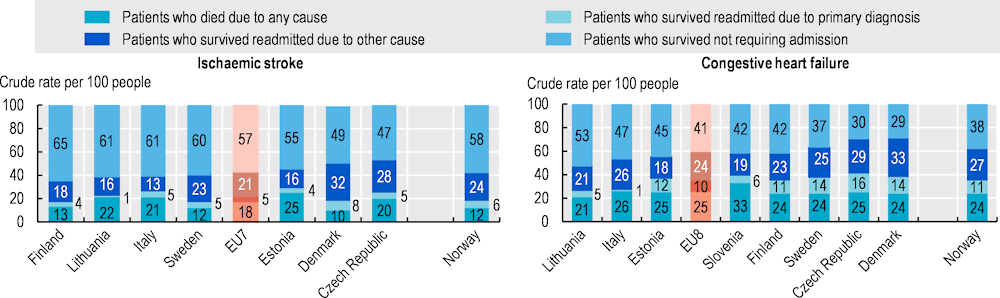

Figure 6.11 shows mortality and readmission outcomes in the year after discharge following hospitalisation for ischaemic stroke or chronic heart failure (CHF). On average, among patients who were admitted with ischaemic stroke in 2018, during one year after discharge 57% had survived and were not hospitalised, 26% had survived and were readmitted to hospital (5% for stroke‑related and 21% for other reasons) and 18% had died. For CHF patients, 41% who survived were not hospitalised, while 34% survived but were readmitted, and 25% died.

For stroke patients, one‑year mortality ranged from below 12% in Denmark, Sweden and Norway to above 22% in Estonia and Lithuania. Thirty-day mortality was also low in Denmark, Sweden and Norway and high in Estonia and Lithuania (see indicator “Mortality following stroke”). For CHF patients, one‑year mortality varied from 21% in Lithuania to 33% in Slovenia.

Hospital readmissions within one year of stroke ranged from 1% in Lithuania to 8% in Denmark for stroke‑related reasons, and from 13% in Italy to 28% in the Czech Republic for other causes. For CHF patients, one‑year readmission rates varied from 1% in Italy to 16% in the Czech Republic for CHF-related causes and from 18% in Estonia to 33% in Denmark for other causes.

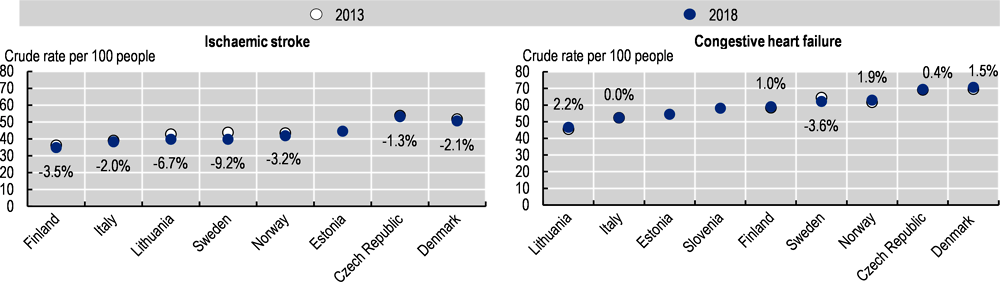

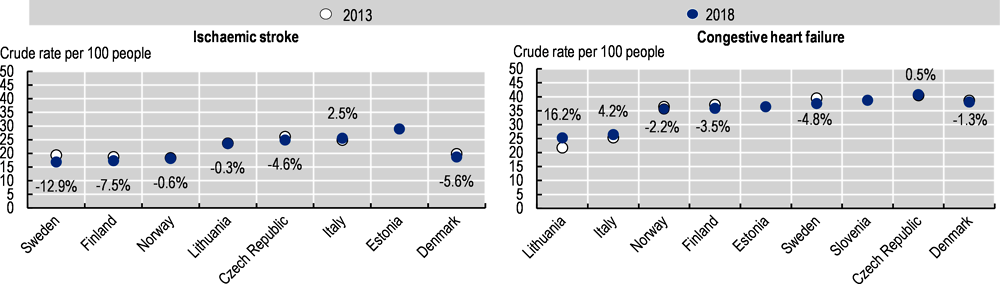

Most countries achieved small improvements between 2013 and 2018 for all-cause mortality and readmission rates for those discharged with stroke and CHF (Figure 6.12) and mortality and readmission rates related to the primary diagnosis (Figure 6.13). Sweden demonstrated the largest improvements in reducing readmissions and mortality following an ischaemic stroke and CHF. However, some countries reported worsening rates, including Lithuania, Norway and Finland.

Countries have continued to adopt and refine reforms to improve integrated care, for example, Estonia adopted a new person-centred care network model in 2018. Finland will adopt in 2023 a new health care reform to drive integration of health and social care. Sweden is reforming care delivery closer to patients with a focus on the most vulnerable populations. Ongoing OECD analytical work is gaining understanding on the extent to which variation in outcomes across countries can be explained by reforms targeting reorganisation of care delivery, provider payment mechanisms and health data systems.