This chapter describes trust levels by gender, education, ethnicity, migrant background, and geographical location. It also presents multivariate analysis of the drivers of trust in New Zealand in the public service, the local government and the parliament. It finds that the responsiveness of services is the most important driver of trust in the public service. In turn, openness and reliability are key drivers of trust in local government councillors. Political efficacy and reliability are key drivers of trust in the parliament. The chapter also addresses additional characteristics that help to understand levels of trust in New Zealand, such as high cultural diversity and dependence on natural resources.

Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions in New Zealand

2. Institutional trust and its drivers in New Zealand

Abstract

This chapter presents data from the Survey on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (OECD Trust Survey) implemented in New Zealand. In addition, where possible, it compares institutional trust and its drivers in New Zealand with trust levels in comparable OECD countries given their size, level of economic and social development and high baseline levels of institutional trust or with strong historical ties to New Zealand. Accordingly, New Zealand is benchmarked to other small advanced economies such as Finland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden and to other Anglophone countries that include Australia, Ireland, Canada and the United Kingdom. While this chapter relies predominantly on data compiled through the OECD Trust Survey it also makes use of secondary source when discussing factors underpinning high levels of trust in public institutions in New Zealand.

2.1. The OECD Survey on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (OECD Trust survey)

The OECD Survey on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions is a new measurement tool supporting OECD governments in reinforcing democratic processes, improving governance outcomes, It is the first cross-national investigation dedicated specifically to identifying the drivers of trust in government, across levels of government and across public institutions. Box 2.1 presents briefly some key characteristics of the OECD Trust Survey including its coverage and implementation method.

The Trust Survey in its current form has been revised and expanded based on methodological suggestions and empirical lessons reflected in the OECD Guidelines on Measuring Trust (OECD, 2017[1]), the TrustLab project (Murtin et al., 2018[2]), the consultative process “Building a New Paradigm for Public Trust” that took place through six workshops between 2020-2021, the updated conceptual Framework on Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions (Trust Framework) (Brezzi et al., 2021[3]), in-depth case studies conducted in South Korea, Finland and Norway (OECD/KDI, 2018[4]; OECD, 2021[5]; OECD, 2022[6]) and discussions held at the OECD Public Governance Committee in 2021 (GOV/PGC/RD(2021)) and at the OECD Committee for Statistics and Statistical Policy in 2020 SDD/CSSP(2020).

Box 2.1. Description of the OECD Trust Survey

The OECD Trust Survey, carried out by the OECD Directorate for Public Governance, has significant country coverage (usually 2000 respondents per country) across twenty-two countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Ireland, Iceland, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom. The large samples facilitate subgroup analysis and help ensure the reliability of the results.

These surveys were conducted online by YouGov, by national statistical offices (in the cases of Finland, Ireland, Mexico, and the United Kingdom), by national research institutes (Iceland) or by survey research firms (New Zealand and Norway). The YouGov online surveys use a non-probability sampling approach with quotas to ensure that samples are nationally representative by age, gender, large region and education. The majority of the surveys conducted by YouGov took place in November and December 2021; the other surveys went into the field within a year of (before or after) that date. Mexico conducted face-to-face interviews focused on urban areas.

The survey process and implementation has been guided by an Advisory Group comprised of public officials from OECD member countries, representatives of National Statistical Offices and international experts. The OECD intends to continue to improve and conduct the survey on a regular basis in the coming years to help governments improve the way they govern, monitor results over time, and better respond to public feedback.

For a detailed discussion of the survey method and implementation, please find an extensive methodological background paper at https://oe.cd/trust.

Source: Adapted from Building Trust to Reinforce Democracy

The OECD Trust Survey was implemented in New Zealand between February 8th and February 24th 2022. This collection period coincides with the Wellington protests, which may introduce some bias into responses. The survey was carried out by Research New Zealand and achieved an effective sample of 2211 respondents. Box 2.2 presents some additional characteristics of the survey.

Box 2.2. Key characteristics of the survey implemented in New Zealand

In order to ensure comparability across countries and guarantee standard quality criteria for all countries that participated to the OECD trust survey the following criteria have been observed for the survey implemented in New Zealand.

Survey respondents were defined as resident New Zealanders aged 18 years and over.

The survey was implemented by Research New Zealand online and was sourced from an online active panel of over 300,000 active members. An active member is someone who has completed at least one survey in the last three months.

The survey is representative of the New Zealand population by age, gender, ethnicity and regions. The achieved sample has been RIM weighted according to these criteria. The weighting parameters were sourced from Statistics New Zealand’s most recent (2018) Census of Populations and Dwellings.

The total sample of 2,211 includes 388 Māori respondents who were oversampled in order to achieve sufficient numbers for analysis purposes.

Results based on the total weighted sample of 2,211 are subject to a maximum margin of error of ±2.1% at the 95% (confidence level) and a design effect (deff) of 1.03. The sub-sample of 388 Māori is subject to a maximum margin of error of ±5.1%.

Source: Technical report provided by Research New Zealand about the implementation of the OECD Trust Survey.

In alignment with the principle of political neutrality some questions from the OECD core questionnaire were removed from the survey implemented in New Zealand. Notably, trust in the national government was not included because of the potential confusions with the political party ‘’The New Zealand National Party’’, shortened ‘’National’’. Further waves of the survey will consider ways of reformulating this question to fit the New Zealand context.

The survey implemented in New Zealand includes the following general question on institutional trust “ On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following institutions? ” accompanied by the following list of institutions (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. List of institutions measured through the OECD Trust Survey in New Zealand

|

Dimension |

Institution |

|---|---|

|

Political/administrative institutions |

Local government councilors |

|

Parliament |

|

|

Public Service (non-elected employees in central government) |

|

|

Local authority/council employees |

|

|

Law and order institutions |

Police |

|

Courts and legal system |

|

|

Non-governmental institutions |

Media |

|

International organizations (United Nations, OECD, World Bank, etc) |

Source: OECD Trust survey implemented in New Zealand.

The measurement approach on the drivers of institutional trust moves away from standard perception questions (e.g. how much confidence do you have in your national government) and instead focuses on specific situations linked to people interactions with public institutions. Typical behavioural questions, as used in psychology or sociology, investigate the subjective reaction expected from individuals when faced with a specific situation. However, the situational questions are not stereotypical behavioural questions: they do not focus on the individual behaviour but rather on the expected conduct from a third party, in this case a public institution, a civil servant or a political figure. Consequently, the questions provide, instead, a measurement on the trustworthiness of public institutions. Unlike attitudes (passive response) and behaviours (active response), trustworthiness is based on expectations of positive behaviour in alignment with the working definition of trust presented in chapter 1. The battery of situational questions for measuring the determinants of public trust in New Zealand in alignment with the OECD trust framework is presented in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2. Survey questions on each of the framework dimensions in New Zealand

|

Policy Dimension |

Questions |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Competence |

Responsiveness |

If many people complained about a government service that is working badly, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that it would be improved?

|

|

If there is an innovative idea that could improve a public service, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that it would be adopted? |

||

|

Reliability |

If a new serious contagious disease spreads, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that government institutions will be ready to act to protect people’s lives? |

|

|

How unlikely or likely do you think it is that the business conditions the government can influence (e.g. laws and regulations businesses need to comply with) will be stable and predictable?

|

||

|

Values |

Openness |

If a decision affecting your community is to be made by the local government, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that you would have an opportunity to voice your views?

|

|

If you need information about an administrative procedure (for example obtaining a passport, applying for a benefit, etc.), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the information would be easily available? |

||

|

If you need information about an administrative procedure (for example obtaining a passport, applying for a benefit, etc.), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the information would be easily available? |

||

|

Integrity |

If a court is about to make a decision that could negatively impact the government’s image, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that the court would make the decision free from political influence? |

|

|

If a government employee was offered money by a citizen or a firm for speeding up access to a public service, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that they would refuse it? |

||

|

Fairness |

If a government employee has contact with the public in the area where you live, how unlikely or likely is it that they would treat both rich and poor people equally? |

|

|

If a government employee interacts with the public in your area, how unlikely or likely do you think it is that they would treat all people equally regardless of their gender, sexual identity, ethnicity or country of origin? |

||

|

If you or a member of your family apply for a government benefit or service (e.g. unemployment benefits or other forms of income support), how unlikely or likely do you think it is that your application would be treated fairly? |

Source: OECD Trust survey implemented in New Zealand

The survey implemented in New Zealand also includes questions on the drivers of trust that were specifically included for this study. These questions were included to, on the one hand to explore additional factors influencing trust in New Zealand (e.g. how the government has treated people in a community or experience with agencies) and on the other hand to further validate the internal coherence of the OECD trust framework for New Zealand. Table 2.3 presents the additional questions included the survey implemented in New Zealand. Annex B presents a detailed description of the differences between the survey implemented in New Zealand and the core OECD questionnaire.

Table 2.3. Additional questions on the drivers of trust included in the survey implemented in New Zealand

|

Additional questions included in the survey in New Zealand |

|---|

|

How much do each of the following influence your trust in the institutions of government?

|

|

Do you agree with the following statements?

|

|

How much confidence do you have in government institutions to:

|

Source: OECD Trust survey Implemented in New Zealand

The next chapter presents the different factors that influence trust in public institutions in New Zealand. As trust is a multidimensional construct that alongside the performance of public institutions depends on a number of individual economic, cultural and socioeconomic determinants (Ananyev and Guriev, 2018[7]; Algan, 2018[8]) these are all addressed in the coming chapter. However, this case study of trust in public institutions places specific emphasis on the drivers related to public governance rather than the individual factors. These drivers are areas where public administrations could take action to influence trust in public institutions. Nonetheless, the analysis controls for individual characteristics and when relevant refers to them.

2.2. Trust varies across institutions in New Zealand

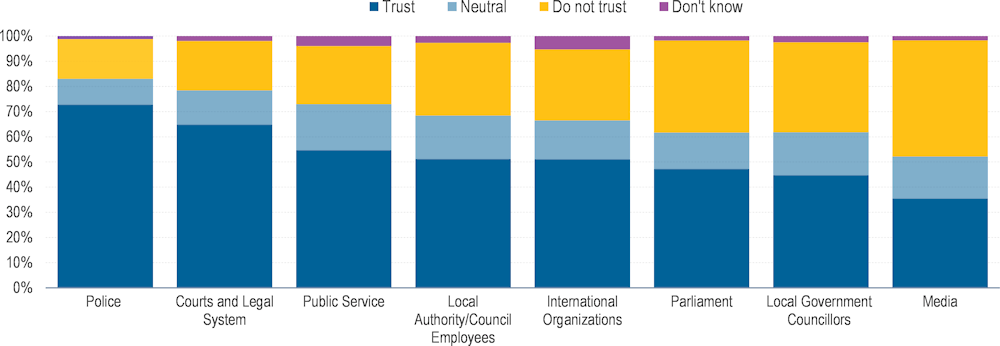

According to the OECD Trust Survey, there is a large variation on trust levels in public institutions in New Zealand (Figure 2.1). Similar to other OECD countries, respondents in New Zealand have highest trust in law and order institutions. Around 7 in 10 respondents trust the police (73%), followed by trust in the courts and legal system (65%), 6 percentage points and 8 percentage points respectively above the OECD average. The news media is the least trusted institution (35%), slightly below the OECD average (39%). Low levels of trust in the news media are consistent with findings from other sources that explain this trend by the fact that media in New Zealand is seen as increasingly opinionated, biased, and politicised (Myllylahti and Treadwell, 2021[9]; Myllylahti and Treadwell, 2022[10]).

Figure 2.1. Trust in the police and courts and legal system are the highest among respondents in New Zealand

Share of respondents in New Zealand who indicate trust (on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust [institution]?” The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the response scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “do not trust” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

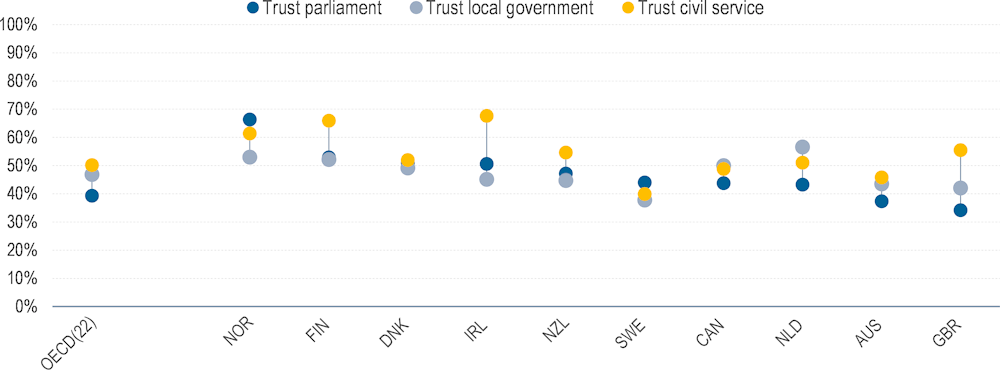

With the caveat that no question about the central government was asked in this survey wave in New Zealand, survey results show that New Zealand scores above the OECD average regarding trust in political and administrative institutions. Trust in the parliament (47%) is eight percentage points above the OECD average (39%). Over half say that they trust the public service (55%), which is higher than the OECD average (50%) but below levels in comparable OECD countries such as Norway (61%), Finland (66%) and Ireland (68%) (Figure 2.2).

Trust in local government councillors1 is on the lower end in comparison to other institutions in New Zealand (45%). Lower trust in local politicians could be linked to fewer competencies and responsibilities of local levels of government in New Zealand as also evidenced by diminishing levels of participation in local politics and a decrease in voter turnout at the local elections (local authority election voter turnout in 2019 was 42%)2.

Figure 2.2. Trust in public service is higher than in the local government and parliament in New Zealand

Share of respondents who indicate trust in various government institutions in New Zealand, selected countries and OECD average, (responses 6-10 on a 10-point scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents the share of response values 6-10 in three separate questions: "On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the [parliament / local government / civil service (public service in New Zealand)]?" The "trust" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale; "neutral" is equal to a response of 5; "Do not trust" is the aggregation of responses from 1-4; and "Don't know" was a separate answer choice. Finland's scale ranges from 1-10. OECD(22) refers to the unweighted average across respondents in 22 OECD countries.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

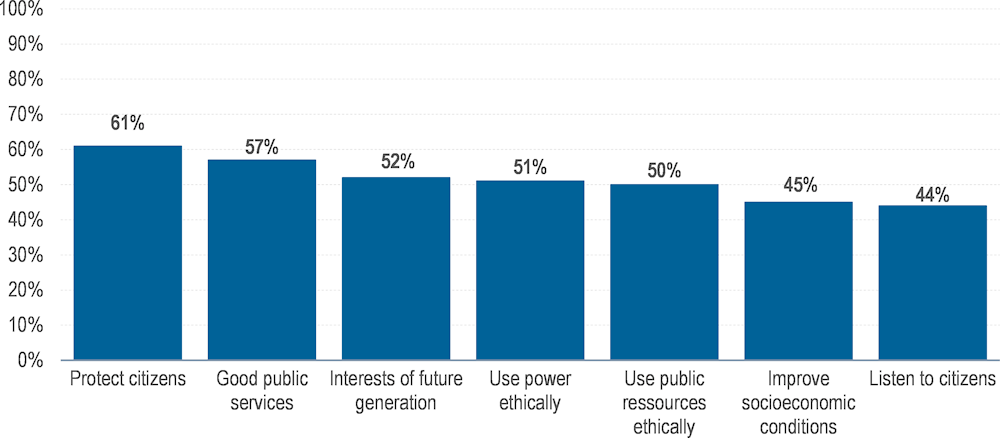

Figure 2.3. The highest confidence in government institutions is to protect citizens

Share of respondents in New Zealand with confidence in government institutions to address various issues, 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question ‘How much confidence do you have in government institutions to: [...]:’’. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that answer “confident” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale 0-10, where 0 is ‘’No confidence at all’’ and 10 ‘’full confidence’’.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

In the survey conducted in New Zealand a question to qualify reasons underlying their trust in public institutions was asked to respondents. Three fifths of the New Zealand population are confident that their institutions will protect them while 56% think they will provide good public services. Half of New Zealanders expect power and resources to be used ethically while 44% of New Zealanders expect institutions to listen to them (See Figure 2.3). Overall, public institutions are evaluated better on their competences than on their values. This is consistent with some recurrent concerns raised by interviewees for this case study who indicated raising inequalities and lack of openness and meaningful engagement as potential aspects undermining trust in public institutions.

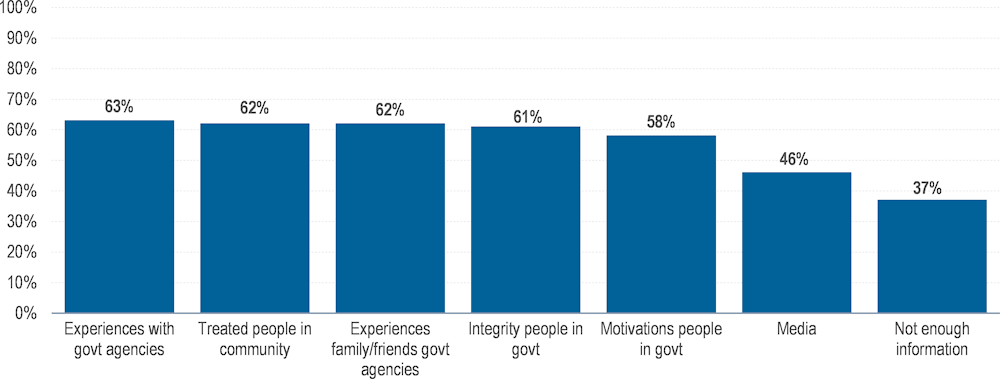

Another specific set of questions included in the survey implemented in New Zealand covers additional reasons that could influence trust in public institutions (Figure 2.4). New Zealanders recognize experience with public agencies, expressed in different forms, as the most relevant element to their trust in government agencies. Over 60% of respondents consider that their experience and those of family and friends with government agencies influences their confidence. The experience of their community and the way in which it has been treated. Reasons related to the media and missing information about the tasks of government institutions are considered as less important to build confidence levels yet some variations exist by population groups (See Box 2.3).

Figure 2.4. Experience with government agencies is the most important reason to influence trust in institutions

Share of respondents in New Zealand who report reasons that influence trust, 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question ‘’How much do each of the following influence your trust in the institutions of government?’’. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that answer “completely” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale 0-10, where 0 is ‘’Not at all’’ and 10 ‘’Completely’’.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Box 2.3. The role of experience in trust building in New Zealand

Several questions about people’s perception on a series of factors influencing trust were included for the first time in an OECD Trust Survey in New Zealand. The questions were formulated in the following way: “How much do each of the following influence your trust in the institutions of government?’’(on a 0-10 response scale ranging from 0-not at all to 10-completely):

1. How the government has treated people in my community

2. Experiences I’ve had with government agencies

3. Experiences my family and/or friends had with government agencies

4. Things I’ve seen in the media

5. The motivations of the people working in government

6. The integrity of the people working in government (e.g. political neutrality, corruption)

7. Not having enough information about what government institutions are doing to be able to trust them

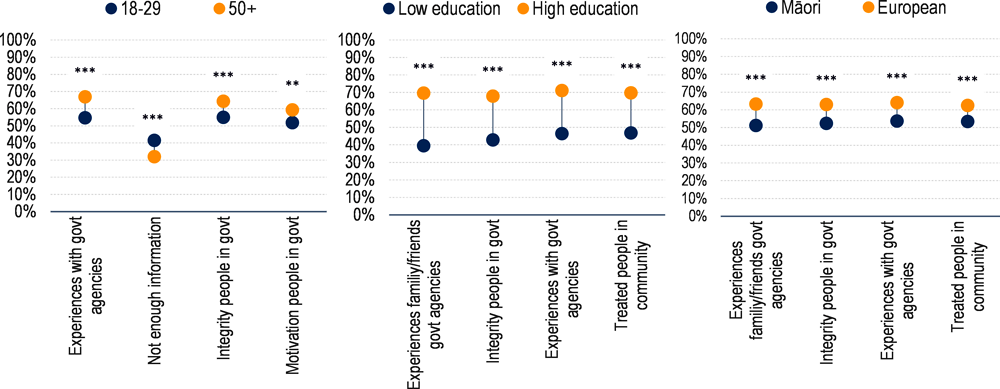

People report that experience by others shape institutional trust. There are however important differences across population groups. Experiences from family and/or friends when interacting with institutions stand as the most important features shaping trust for the highly educated. Accordingly, 70% of people with a university degree report this to be a key factor influencing trust compared to just 30% in the case of people with only secondary education. In turn, at 67% people own’s experience is the most reported feature influencing trust in the case of respondents who are 50 or over compared to 59% in the case of those between 18 and 30. Conversely, 42% of younger respondents say that the lack of information about government institutions is influencing their trust level compared to just 32% in the case of older respondents (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Important reasons to influence trust, by age, education and ethnicity

Share of respondents who report different reasons that influence their trust levels by age, education and ethnicity, 2021

Note: Figure presents the difference between 1- younger (18-29) and older (50+) respondents (left figure); 2- lower educated and higher educated respondents (middle figure); 3- European and Māori respondents (right figure) of responses to the question ‘’How much do each of the following reasons influence your trust in the institutions of government?’’. Shown here is the proportion of respondents that answer “completely” based on the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale 0-10. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The survey also incorporates a question on interpersonal trust reflecting in the link, recognized in the literature, between interpersonal and institutional trust (Lipset and Schneider, 1983[11]; Job, 2005[12]; Bäck and Kestilä, 2009[13]).On average across countries, people tend to have high trust in other people (Figure 2.6). 65% of New Zealanders consider that most people can be trusted which is close to the OECD average but on the low end of the benchmarking group only above Australia (63%) and Sweden (61%). Countries with high trust in other people are the Netherlands (83%), Norway (78%) and Ireland (78%).

Figure 2.6. Trust in others in New Zealand is close to the OECD average

Share of respondents in New Zealand who indicate trust (on a 0-10 scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question in general how much do you trust most people?” “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust”. The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the response scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “do not trust” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

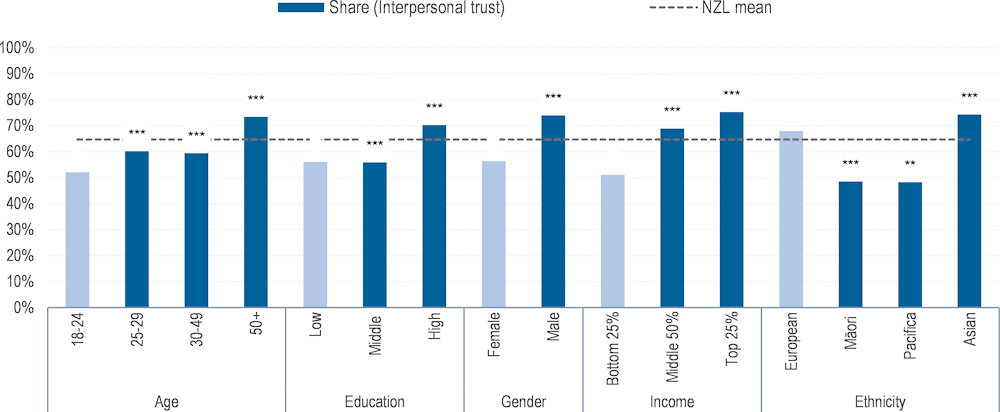

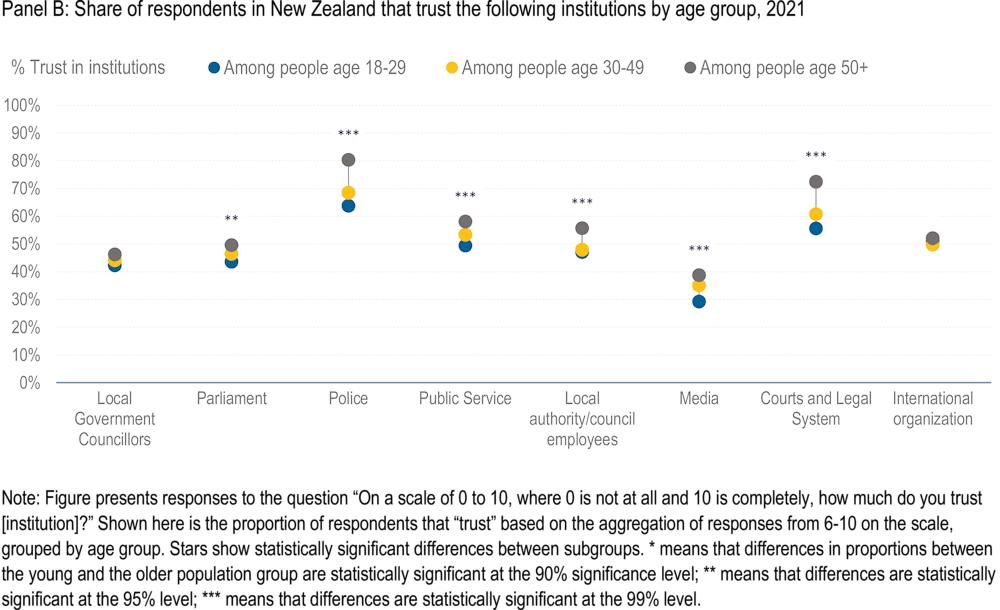

2.3. People of Asian background, older cohorts, and the more educated report higher trust levels

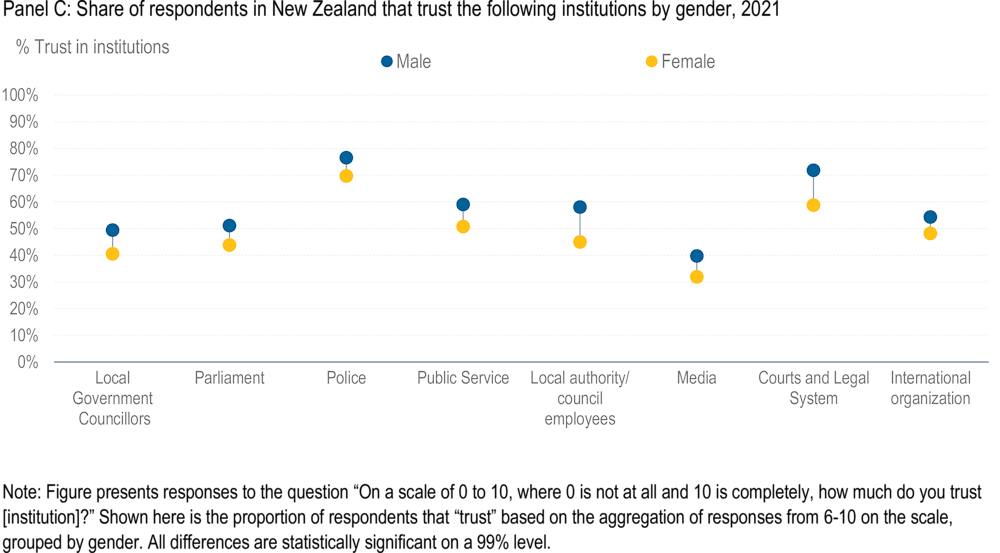

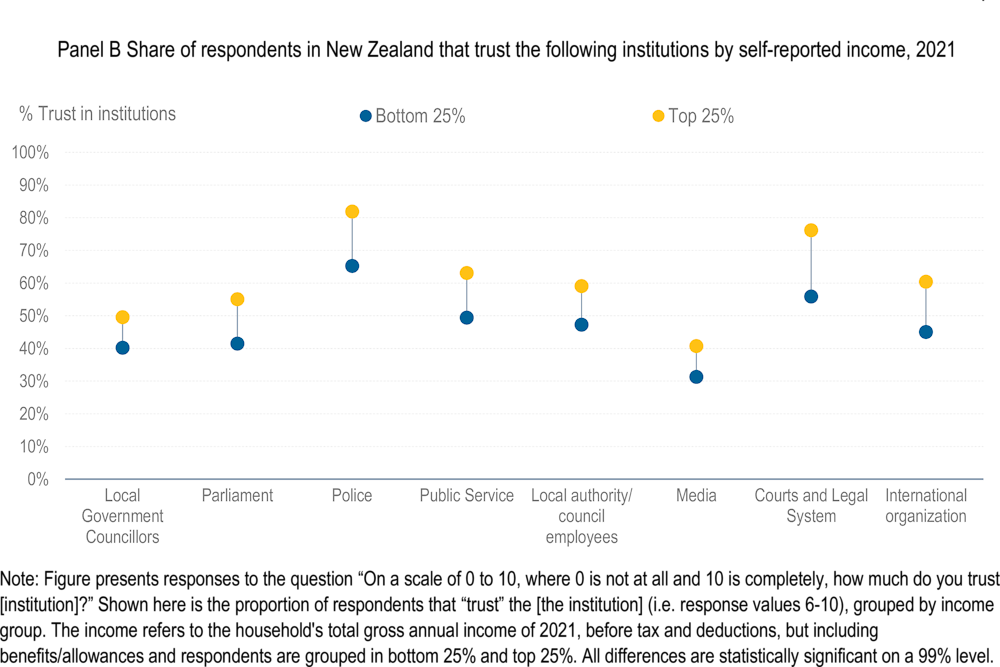

In general, and like in other surveyed OECD countries, women, younger people, as well as those with lower education and income levels tend to have lower trust in others and in public institutions (Figure 2.7 and Table 2.4). This trend is consistent with results for interpersonal trust where the youngest cohort display significantly lower levels of trust than other age groups (Figure 2.7). As discussed in chapter one, interpersonal and institutional trust tend to be correlated and mutually reinforcing (OECD, 2022[14]).

Regarding geographic and ethnic disparities, the Māori and Pacifica populations are the least trusting as well as respondents living outside urban areas such as Wellington and Auckland. This finding is consistent with trends in other countries, where people who live geographically further away from political institutions or economic centres often feel excluded from the political system and may have more limited access to high quality services, and as a result tend to have lower trust (OECD, 2022[15]; Mitsch, Lee and Ralph Morrow, 2021[16]; Wood, Daley and Chivers, n.d.[17]). In the case of New Zealand, while 61% and 57% of the population in Wellington and Auckland trust the public service, trust is down to 53% and 47% in more remote areas of the North and South islands, a trend also observed for other institutions such as the parliament and local government institutions (See Table 2.4).

Figure 2.7. There are differences in interpersonal trust across population groups in New Zealand

Share of respondents in New Zealand that trust most people by subgroup, 2021

Note: Figure presents the responses to the question “On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, in general how much do you trust most people?” The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. “NZL mean” presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. Top 25% and bottom 25% refers to the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. High education is defined as the ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, and low education refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

Respondents who identified as Māori have lower levels of trust, whereas respondents who identified as Asian have the highest trust in public institutions. For example, only 42% of Māori reported trusting the public service compared to 56% of European and 66% of Asians. As will be discussed in subsequent sections when controlling for different socioeconomic characteristics being Māori is the only one that stands as significant when it comes to trust in the public service.

Still, Māori are inherently diverse thus generalizations could be misleading. However, the fact that some Māori could feel that historically the crown has breached their trust through the different versions of the Waitangi treaty and the delay in its application as well as their marginalization from political decision-making might explain lower average trust levels for Māori. A recent report published by the office of the Auditor General on Māori perspectives of public accountability based on a series of interviews with Māori concludes that Māori perceive trust as relational, reciprocal, that Tikanga3 (Māori values) builds trust and confidence and that the power imbalance thwarts trust (Office of the Auditor General, 2022[18]).

In turn, trust in the media (the least trusted institution) is also low among respondents identifying as Māori, just over a quarter of Māori reported trusting the media compared to a third in the case of people identifying as New Zealand European (See Table 2.4). Some Māori populations are more likely to trust information provided by their Iwi and people in their community as exemplified by the COVID-19 vaccination campaign and the role played by iwi in convincing Māori to get vaccinated as opposed to general vaccination campaigns. Information provided through institutional channels may not be necessarily attuned with cultural practices of some Māori groups.

Nonetheless, despite having overall comparatively lower levels of trust, significant institutional efforts to incorporate Māori’s viewpoint into decision-making and to involve them in governance processes leading to policy development and implementation, were acknowledged by different institutional and non-institutional stakeholders interviewed for this case study, including those representing Māori communities. The necessity of investing in building long-term trust relations with Māori was recognized as a crucial step for raising trust levels between Māori and the government and is the approach being taken by many government institutions.

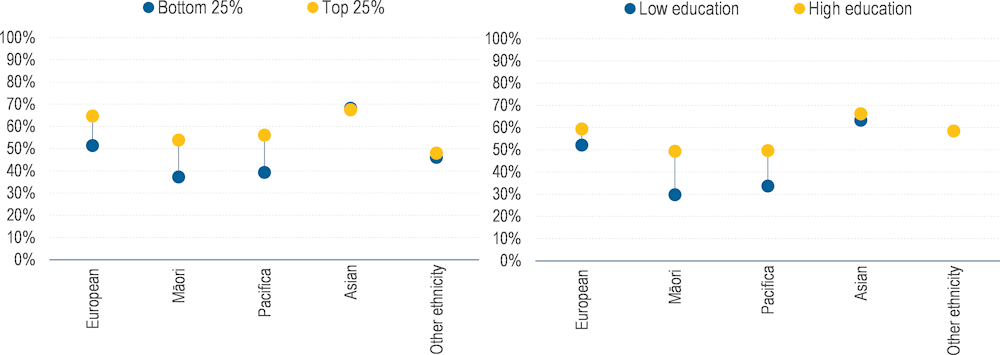

Māori are themselves a diverse group. Box 2.4 below displays trust in the public service by ethnicity considering people’s education and income levels as well. While these statistics are not significant as the sample was not designed for such purpose they are indicative of the variations in trust levels when combining different characteristics that go beyond just ethnicity. A study conducted by the Public Sector Commission and that uses data from the Kiwis Count finds that after controlling for socioeconomic variables, the size and significance of ethnicity in trust in the public sector brand or trust based in recent experience diminishes (Papadopoulous and Vance, 2019[19]).

Box 2.4. Trust in the public service by a combination of subgroups

Figure 2.8 shows the variation in trust levels by ethnicity when combined with respondents’ income and education. People who identified as European, Māori and Pacifica, who are in the highest quartile of the income distribution, have substantively higher levels of trust. Differences in trust by education and income among the Asian population and people from another ethnicity are minimal. The trust gap in the public service between people with lower and higher education is the largest among Māori. These differences shed light on the diversity within population groups and call for nuanced analyses with larger survey samples that would allow analysing these differences systematically across and within various population groups.

Figure 2.8. Trust in the Public Service is lower among people with lower income and lower education

Share of respondents who indicate trust in the Public Service in New Zealand (responses 6-10 on a 10-point scale), 2021

Note: Figure presents responses to the question “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the Public Service?” The “trust” proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the response scale; “neutral” is equal to a response of 5; “do not trust” is the aggregation of responses from 0-4; and “Don't know” was a separate answer choice. The trust levels are disaggregated by ethnicity and income levels and ethnicity and education levels. The left figure shows respondents belonging to the bottom and top 25% of the income distribution based on household's total gross annual income of 2021, before tax and deductions, but including benefits/allowances. The right figure shows respondents with “high education” referring to ISCED 2011 education levels 5-8, i.e. university-level degrees such as Bachelors, Masters or PhD, while “low education” refers to less than a completed upper secondary degree. No significance levels are reported because the sampling of the survey was not designed for testing differences across small subgroups of the population.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The consistently highest levels of institutional trust among respondents of Asian background could be explained by some socioeconomic characteristics. 88% of the respondents identifying as Asian have a university education and institutional trust is consistently higher among people with a university education (See Table 2.4). In addition, people of Asian background often represent collectivistic values emphasizing higher consideration for authority (Confucian values) and the need to fit in with others to avoid conflict in society in particular when they have lived abroad (Hempton and Komives, 2008[20]) (Zhang et al., 2018[21]). The combination of these factors might help explain respondents with Asian background rather positive assessment of public institutions and the confidence they place in them.

Table 2.4. Share of trust levels and standard errors in New Zealand, by ethnicity and region

|

|

Local Government Councilors |

Parliament |

Police |

Public Service |

Local authority/ council employees |

Media |

Courts and Legal System |

International Organization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Share |

|||||||

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

European |

43% |

45% |

76% |

56% |

51% |

33% |

67% |

51% |

|

Māori |

34%*** |

36%*** |

52%*** |

42%*** |

38%*** |

26%** |

45%*** |

32%*** |

|

Pacifica |

37% |

43% |

61%*** |

44%** |

38%*** |

26% |

49%*** |

46% |

|

Asian |

64%*** |

69%*** |

81%** |

66%*** |

68%*** |

57%*** |

78%*** |

72%*** |

|

Other |

47% |

40% |

71% |

52% |

51% |

37% |

68% |

48% |

|

Region |

||||||||

|

Auckland |

51% |

54% |

75% |

57% |

56% |

42% |

69% |

56% |

|

Wellington |

45% |

53% |

74% |

61% |

54% |

36% |

65% |

55% |

|

Canterbury |

45% |

46%* |

72% |

53%* |

51% |

35% |

63% |

54% |

|

Waikato |

50% |

54% |

78% |

64% |

56% |

35% |

71% |

52% |

|

Rest of North Island |

37%** |

37%*** |

69% |

47%*** |

43%** |

28%** |

59% |

42%*** |

|

Rest of South Island |

37%* |

40%*** |

69% |

53% |

46%* |

32% |

63% |

45%** |

Note: Figure presents the share of response values 6-10 to the question: "On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the [institution]?" * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Significant higher shares than the reference group are highlighted in blue and significant lower shares than the reference group are highlighted in red. In bold are the reference group (European and Wellington respectively).

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

The largest gap in trust by socioeconomic categories is on justice-related institutions. Law and order institutions are the most trusted institutions in New Zealand. However, there are important variations across population groups. For example, 52% of Māori and 61% of Pacific trust the police compared to 76% of people of European background, even though substantial efforts have been made towards building a police force that represents the diversity of the society and to strengthen efforts to work via partnerships with individuals, communities, businesses, and other public agencies. Still, Māori are overly represented in jail with over 50% of inmates being of Māori ethnicity and Māori are also more likely to be victims of crimes (Ministry of Justice, 2022[22]). These factors may contribute to explain comparatively low levels of trust by Māori in law-and-order institutions.

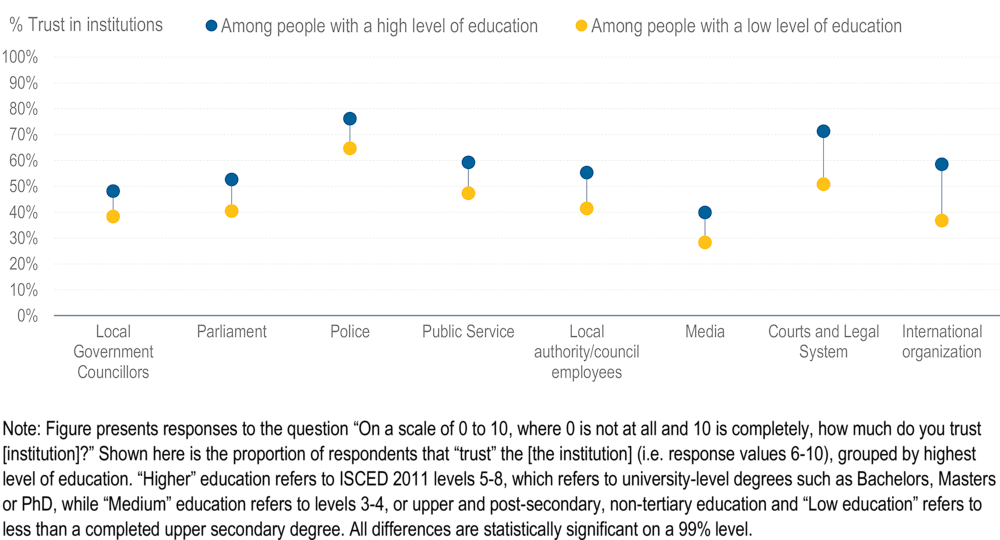

Consistent with findings from other OECD member countries, the police (80%) and the courts (72%) are most trusted by older cohorts as compared to younger or middle-aged respondents (OECD, 2022[15]) . The trust gap in courts and legal system between people with low and high levels of education is also large at 20 percentage points (See Figure 2.9 Panel A) and 16 percentage points between younger and older respondents (See Figure 2.9 Panel B). Men have 13 percentage points higher trust in courts and legal system, which is the largest gender gap across all institutions (See Figure 2.9 Panel C).

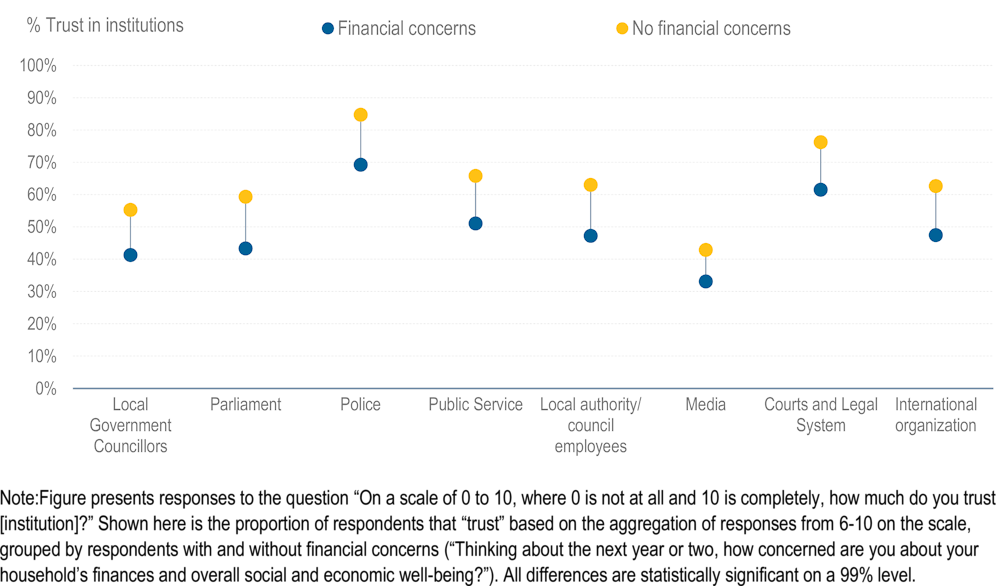

Figure 2.9. People with high level of education, older respondents and male report higher trust in public institutions

Panel A: Share of respondents in New Zealand that trust the following institutions by highest level of education, 2021

In addition to personal characteristics, perceptions of one’s own situation could also influence trust in public institutions. People who feel financially insecure, i.e. reporting concerns about their household’s finances and overall social and economic well-being, have 16 percentage points lower trust in local authority/council employees and the parliament (just below the OECD average of 17 percentage points for the parliament) compared to people with no financial concerns. For all institutions considered, the gap is higher than 10 percentage points (See Figure 2.10 Panel A).

Perceptions of socioeconomic vulnerabilities are consistent with self-reported income, a more objective measure of socioeconomic status. Respondents belonging to the bottom 25% of the income distribution in New Zealand have lower trust levels for all institutions. The income gap is large and consistent across institutions reaching up to 20 percentage points for trust in courts and legal system and 16 percentage points in the case of the police (See Figure 2.10 Panel B).

Figure 2.10. Trust in institutions is lower among people with perceived socioeconomic vulnerabilities and low self-reported income

Panel A Share of respondents in New Zealand that trust the following institutions by financial concerns, 2021

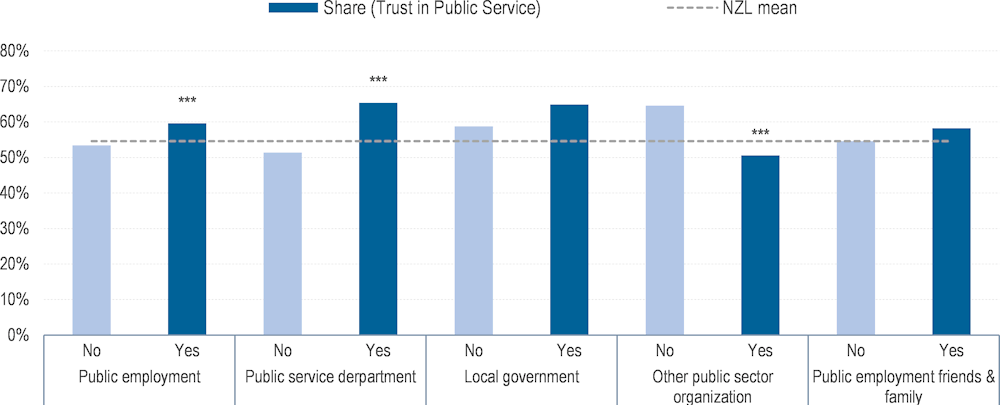

31% of the New Zealand respondents indicated that they have worked in the public sector. Figure 2.11 shows that people who have worked in the public sector have on average higher trust in the public service. The level of trust is especially higher for those that have worked in the public sector4 (comprising the public service, local government, and other public sector). There is however variation within the public sector. For those who have worked in a public sector department trust is significantly higher than for those who haven’t, yet the opposite is true for those who reported working in other type government agency. Only direct experience has an effect on trust as work by a friend or family member does not have any effect on trust in the public service.

Figure 2.11. People that have worked in the public sector have higher trust in the Public Service

Share of respondents in New Zealand that trust the Public Service by subgroup, 2021

Note: Figure presents the distributions of responses to the question "On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the Public Service (non-elected employees in central government)?" The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. "NZL mean" presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. ‘’Public employment’’ is based on responses to the question ‘’Have you ever worked in the public sector?’’, followed by the question: ‘’ Have you ever worked in... [A public service department or departmental agency/Local government/Other public sector organisation]’’ and ‘’Do you have any family members or friends who work or have worked in the public sector?’’. * means that differences in proportions are statistically significant at the 90% significance level; ** means that differences are statistically significant at the 95% level; *** means that differences are statistically significant at the 99% level. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

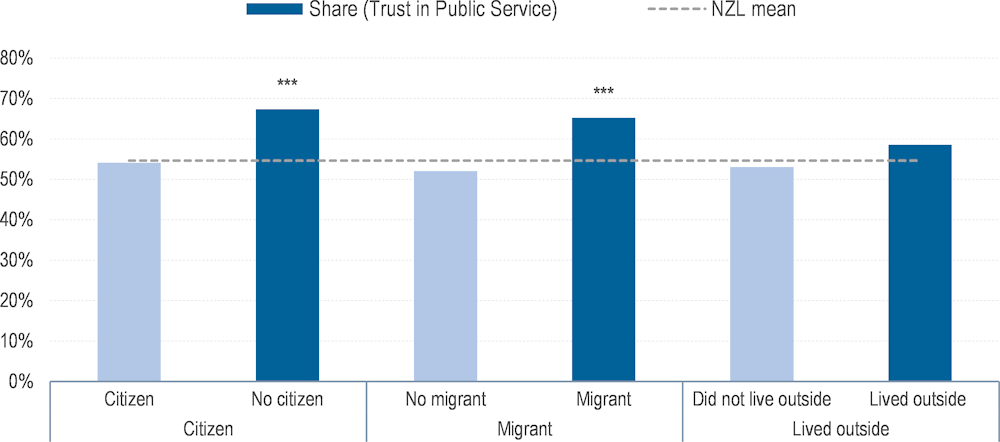

There are also variations in trust levels by migrant status (Figure 2.12). Migrants without New Zealand citizenship have higher trust levels in the public service (67%) than people who have citizenship (51%). Similar results are observed for migrants (people born in another country and who moved to New Zealand at a certain point). 65% of people born abroad express trust in the public service compared to 52% of those born in New Zealand. This likely reflects the fact that New Zealand’s migration criteria weight education very strongly and, as a result, migrants have higher average levels of education (and therefore trust) than the New Zealand born population. These results are also consistent with those found in other advanced small-developed economies such as Norway and Finland where the same pattern is observed for people with a migrant background (OECD, 2022[6]; OECD, 2021[5]).

Figure 2.12. Trust in Public Service is higher among migrants and those that have lived outside of New Zealand

Share of respondents in New Zealand that trust the Public Service by subgroup, 2021

Note: Figure presents the distributions of responses to the question "On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust the Public Service (non-elected employees in central government)? " The "likely" proportion is the aggregation of responses from 6-10 on the scale. "NZL mean" presents the weighted average across all respondents in New Zealand. ‘’Lived outside’’ is based on the responses to the questions ‘’ Have you spent time living outside of New Zealand as an adult?’’. ‘’Migrant’’ is based on responses to the question ‘’ Were you born in New Zealand?’’. Reference group in light blue.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

2.4. New Zealand has higher trust than other countries with similar levels of cultural diversity and higher cultural diversity than other countries with similar levels of trust

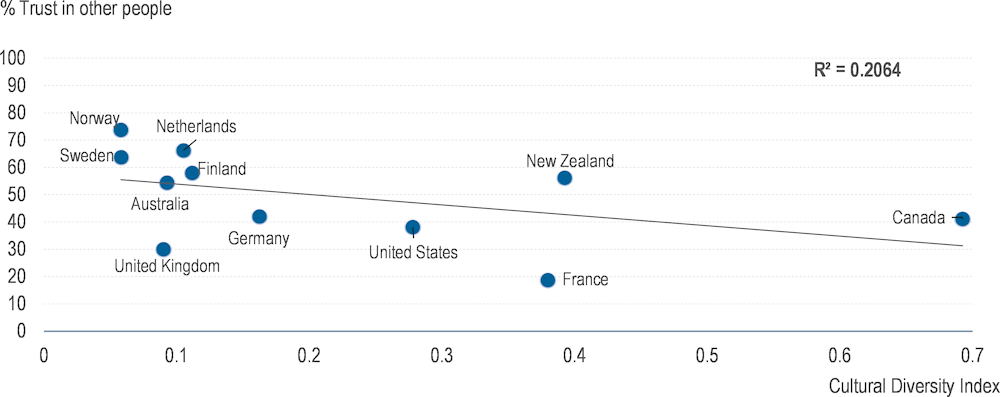

It is often argued that the high trust model of government characteristic of the Nordic and other northern European countries can be partly attributed to relatively high levels of social and ethnic homogeneity (OECD, 2022[6]; OECD, 2021[5]). It is certainly well established that social and ethnic homogeneity are associated with higher interpersonal trust (Zmerli and Van der Meer, 2017[23]) and that high levels of interpersonal trust contribute to high levels of institutional trust (Rothstein and Ulaner, 2005[24]). In this sense, New Zealand represents something of a paradox.

Figure 2.13 compares levels of interpersonal trust and levels of cultural diversity measured by the Greenburg Index of cultural diversity (Goren, 2013[25]). Compared to other countries with similar levels of trust, New Zealand has a high level of cultural diversity. However, compared to other countries with similar levels of cultural diversity New Zealand has high levels of trust. This suggests that high trust in New Zealand is not driven by cultural homogeneity (and might suggest that the importance of cultural homogeneity to high trust is lower than is sometimes suggested). Similarly, other countries with similar political traditions – such as the United Kingdom or Canada in Figure 2.13 - have lower levels of trust than New Zealand suggesting that New Zealand’s constitutional model is unlikely to be a key driver of high trust here.

Two factors may help explain New Zealand’s relative position of high trust and high cultural diversity. First, New Zealand has high levels of migration and according to the 2018 census over a quarter of the population is foreign born. Since the 1990s this migrant population has increasingly come from non-anglophone countries. This migrant population largely has higher levels of trust than the New Zealand average (Smith, 2020[26]).

A second important factor in New Zealand’s ability to sustain high levels of trust in a culturally heterogeneous society is that levels of trust are path-dependent. (Rothstein and Ulaner, 2005[24]) note that high levels of interpersonal trust are often grounded in effective and trustworthy institutions. Similarly, it is these high levels of interpersonal trust that support institutional quality. In effect, historical high or low levels of institutional trust are potentially self-sustaining leading to virtuous/vicious circles at the national level. New Zealand, with a long history of effective and trustworthy institutions may be in a high trust equilibrium. In these circumstances events that undermine public trust in institutions are of particular concern as they risk pushing New Zealand away from this equilibrium.

Few high-profile cases had occurred over the past years including key agencies5 where misfunctioning of public institutions received significant media attention. In all cases there were credible and strong arguments made in the media or review/inquiry reports regarding the managerial culture of the organisations in question (Easton, 2019[27]; Newsroom, 2020[28]). These focused on the impact of senior leadership culture on organisational competence. The second issue is that all three failures were publicly connected to trust in the relevant institutions and their ability to effectively perform their functions. While in all cases accountability mechanisms worked well, including through direct responsibility being taken by chief executives, and corrective measures were implemented, they shed light about the role that the media could play in shaping trust patterns and the importance of learning lessons in terms of strengthening a managerial culture that relies in technical knowledge and institutional memory.

Figure 2.13. Cultural diversity and interpersonal trust are negatively associated, 2013

2.5. High levels of trust underpin New Zealand economy

As previously discussed, perceived economic insecurity and income levels influence institutional trust. Preserving high levels of institutional trust is key to the functioning of the New Zealand economy. Trust is essential to a country’s economic performance. In 1972 Kenneth Arrow famously argued that “virtually every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust, certainly any transaction conducted over a period of time. It can plausibly be argued that much of the economic backwardness in the world can be explained by a lack of mutual confidence” (p.357) (Arrow, 1972[29]). Although Arrow’s argument was made before the availability of good cross-country data on trust, the emergence of such data from the early 1990s onwards has contributed to extensive empirical research on the relationship between trust and economic outcomes that largely vindicates the initial insight.

A recent systematic review of the literature on the relationship between trust and economic outcomes (Smith, 2020[26]) identifies 16 papers examining the relationship between institutional trust and the rate of economic growth. All 16 papers show a positive cross-country relationship between the rate of economic growth and institutional trust and for all but one this relationship is statistically significant at conventional levels. Looking at the relationship between trust and the level of income rather than the rate of economic growth, (Auty and Furlonge, 2019[30]; Algan and Cahuc, 2010[31]) provide convincing evidence that changing levels of institutional trust over the 20th century explain changes in levels of income and that this relationship is causal. There are also a number of studies looking at the relationship between trust and productivity (Hazeldine, 2022[32]; Coyle and Lu, 2020[33]; Smith, 2020[26]; Knack and Keefer, 1997[34]; Bjornskov and Meon, 2015[35]), which suggest that institutional trust is associated with higher multifactor productivity at the country level. In fact, it is likely that trust is a key element of multifactor productivity at the country level (Legge and Smith, 2022[36]).

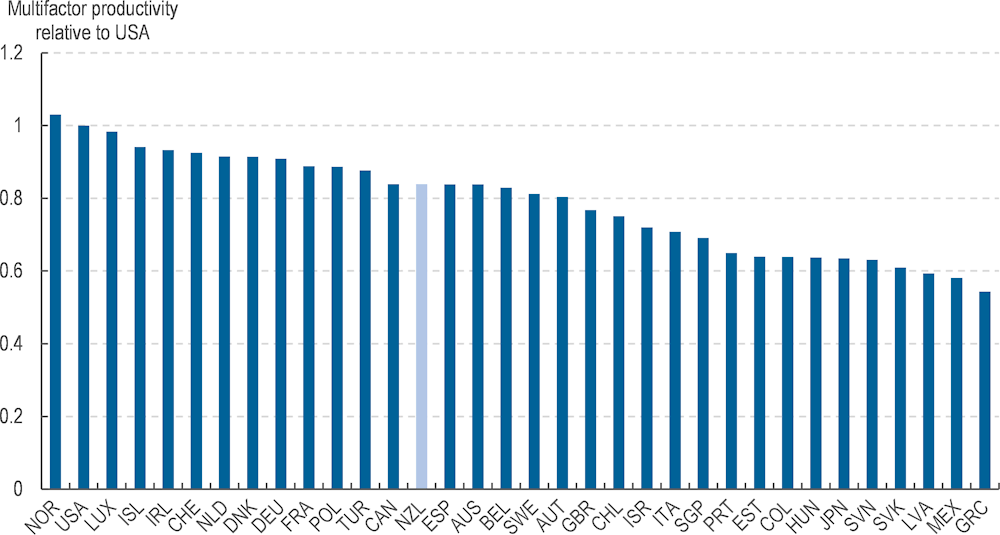

2.6. Although institutional trust levels are high, New Zealand is only a medium-productivity country

Trust is important to economic outcomes, but much of its impact is not reflected in the measures of produced capital and human capital (labour) that underpin the system of national accounts and traditional measures of inputs and outputs. As a result of this, the impact of trust on the economy is largely reflected in measured multifactor productivity (Coyle and Lu, 2020[33]; Legge and Smith, 2022[36]; Smith, 2020[26]). Although New Zealand has high levels of institutional trust, multifactor productivity is only moderate (Figure 2.14). This implies that New Zealand faces a significant downside risk from falling trust. Levels of trust in New Zealand society are high by global terms and have limited scope to increase. However, there are many countries with lower levels of trust – including a number of countries with similar cultural backgrounds and histories (e.g. Australia, the United States). Moreover, large falls in trust are possible over relatively short periods of time as has been seen in the United States since 1990 (McGrath, 2017[37]).

Figure 2.14. Multifactor productivity is moderate in New Zealand

2.7. Dependence on natural resource rents places pressure on New Zealand’s high-trust model

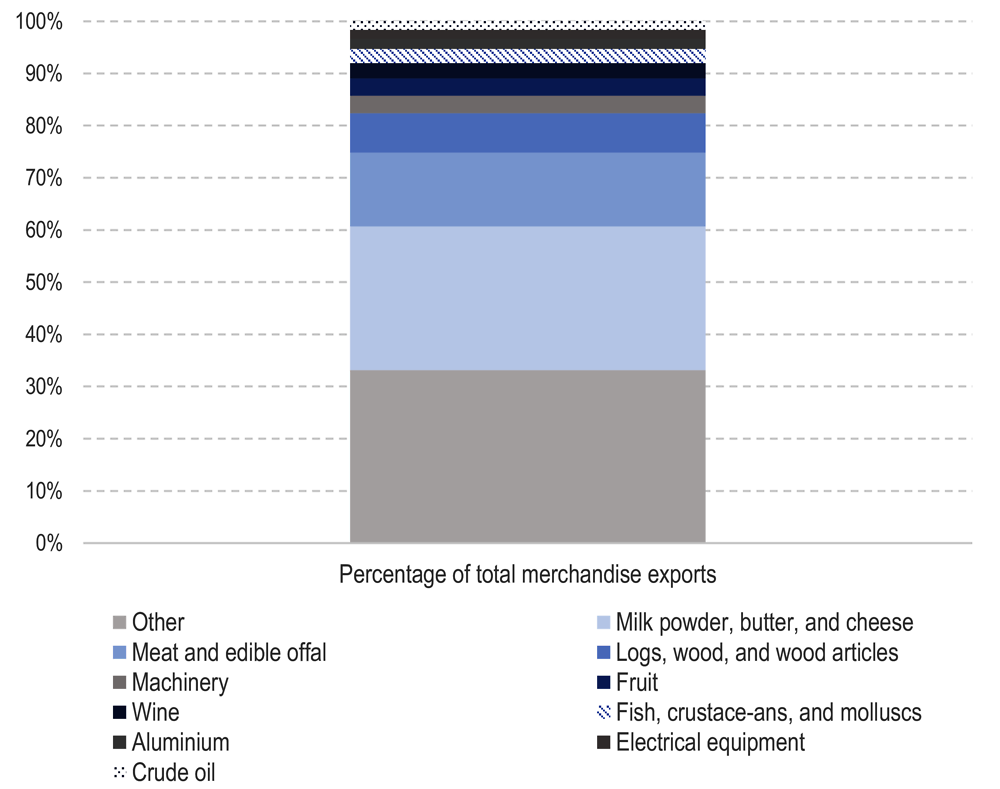

One source of risk to New Zealand’s high trust economic model lies in its dependence on natural resource rents. Under a previous heading it was discussed the degree to which New Zealand’s total wealth stock is dominated by natural capital. This dominance is reflected in the makeup of New Zealand’s exports. Figure 2.15 shows the make-up of New Zealand’s merchandise exports (i.e. exports other than services) in 2021. Of total merchandise exports, 61.8% are primary products and 58.2% are agricultural products (the difference being aluminium and crude oil exports). However, countries with high levels of trust and high dependence on natural capital are rare (Norway being the other obvious example).

The abundance of natural resources can result in a resources curse to a large extent because the ability to extract income from economic rents from natural capital reduces the need to build effective institutions. Although New Zealand is not affected by the resource curse in its traditional form, there is reason to believe that the high level of dependence on natural capital places pressure on institutional trust.

Figure 2.15. Of total merchandise exports in New Zealand, a large majority are primary products and agricultural products

Note: Commodities exported by as a percentage of total merchandise exports, 2021

Source: Overseas Merchandise trade statistics, June 2021, Statistics New Zealand

In New Zealand natural resource allocation and management decisions are decided under the ambit of the Resource Management Act 1991 (the RMA). The RMA decentralises much decision making about natural capital and places this in the hands of local government (both at the regional level through regional councils and at the more local level through territorial authorities)6. When introduced the intent of the RMA was to decentralise resource management decisions and delegate these to the level where the effects of the decisions would be most strongly felt. However, more recently there has been concern that the RMA has been working ineffectively in managing natural resources.

The RMA has been criticised from a range of different perspectives with concerns around its complexity, its lack of direction, and particularly weak support for monitoring and enforcement on the part of the local bodies tasked with implementing it in practice (Fischer, 2022[38]). One issue that is of particular concern from the perspective of institutional trust is that the organisations tasked with monitoring and enforcing environmental outcomes under the RMA are also tasked with regional economic development. In some cases, the issue goes beyond policy responsibility for economic development with local bodies actually owning assets with significant environmental impacts to be monitored under the RMA (Fischer, 2022[38]).

Concerns around conflicts of interest in resource management decisions under the RMA have created a perception among some groups that decision-making around natural capital has been captured – at least partly – by vested interests (Brown, Peart and Wright, 2016[39]). Issues with water quality and allocation of water rights to dairy interests have had a high media profile in the last decade (Gudsell, 2017[40]; Corlett, 2020[41]) both due to concerns around over-allocation of water rights in dryland areas and water quality issues associated with nitrate pollution.

This is partly supported by official enquiries. For example, while prosecution decisions should be made on technical and legal grounds, elected officials such as local councillors may be directly involved in the decision-making process (Office of the Auditor General, 2011[42]). Similar issues also exist with respect to other aspects of natural capital such as the quota system that underpins fisheries management (Heron, 2016[43]). More recently the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment has highlighted the significant gaps that exist in the data available to monitor natural capital (Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 2019[44]).

While New Zealand’s management of its natural resource stocks has not yet led to an observable impact on institutional trust, concerns about the lack of effective monitoring and enforcement and a perception of undue influence from vested interests are of concern. Significant reforms around resource management are currently underway. This includes repealing the RMA and replacing it with three acts: a climate change adaptation act, a strategic planning act, and a natural and built environment act. As these reforms are enacted they present a significant opportunity to shore up the infrastructure around institutional trust in New Zealand, particularly with regard to natural resource management.

2.8. Increases in trust have occurred under the context of stable levels of income inequality but raising housing prices are a risk

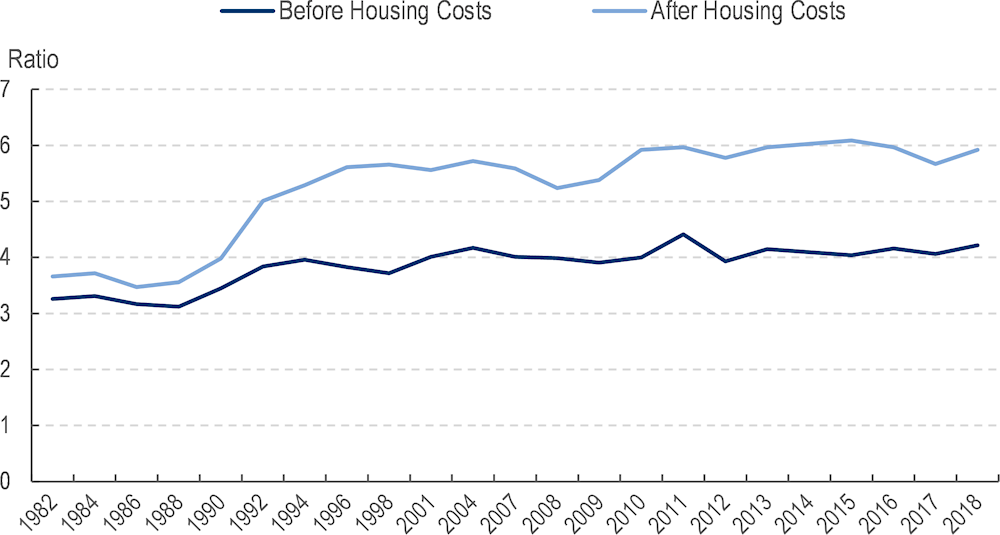

As shown by OECD data and in Chapter One levels of institutional trust in New Zealand are high and have remained stable or even increased over time. Income inequality in New Zealand rose rapidly between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s and it has subsequently remained relatively stable. Figure 2.14 below shows the ratio between the 90th percentile and the 10th percentile of incomes in New Zealand – a summary measure of income inequality – over the period from 1982 to 2019. Following the economic reforms of the late 1980s and early 1990s income inequality has been relatively stable whether measured by the 90/10 ratio as in Figure 2.16 or by other measures of income inequality such as the Gini coefficient (Perry, 2019[45]). Overall, the general rise in trust measures in New Zealand in the 2004 to 2020 period likely reflects the impact of factors unrelated to income inequality or economic performance more generally.

Figure 2.16. Income Inequality in New Zealand has been increasing

Note: Income Inequality in New Zealand: the P90:P10 ratio, 1982 to 2018, total population.

Source: Perry 2019.

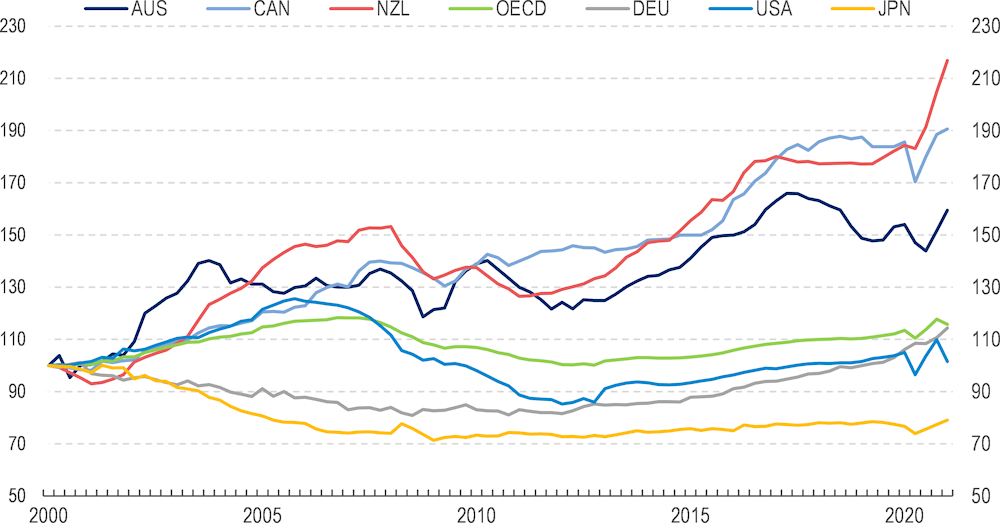

Figure 2.17 below shows the house prices to income ratios in New Zealand compared to other OECD countries from 2000 to 2022. The increase in New Zealand has been the highest amongst countries displayed. As a result of highly expansionary monetary policy, the suspension of the loan-to-value ratio (LVR) household debt increased to 169% of disposable income and house prices to levels that the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) judges to be unsustainable (OECD, 2022[46]).

Figure 2.16 shows that there is a higher level of income inequality after housing costs have been deducted from income than before. In addition, there is evidence that income inequality after housing costs increased over the period since 2000, with the 90/10 ratio of after housing cost income higher following the 2008 global financial crisis when compared to the period before it (Figure 2.17). Throughout the interviews carried out for this study spiking housing prices were mentioned as a potential reason that could affect trust by deepening current and intergenerational inequalities (See Chapter 3).

Figure 2.17. House prices-to-income ratios have increased more than in other countries over the last year

Note: The price to income ratio is the nominal house price index divided by the nominal disposable income per head and can be considered as a measure of affordability.

Source: OECD Economic Outlook database.

2.9. The drivers of trust in public institutions in New Zealand

The OECD Trust Survey implemented for this case study makes it possible for the first time in New Zealand to carry out a comprehensive analysis of the determinants of trust. As presented at the beginning of this chapter the survey includes questions on trust levels of institutions Table 2.1 and 12 questions on the perception of trustworthiness of public institutions in New Zealand according to the five dimensions of the OECD Framework on the determinants of public trust presented in Table 2.2 (i.e. responsiveness, reliability, openness, integrity, fairness). The survey in New Zealand included a question about people’s confidence in government institutions to perform different tasks associated with the dimensions of the OECD framework. Figure 2.3 shows that while slightly more than 60% of the population are confident that public institutions will protect them, just 44% expect to be listened to. All in all, components pertaining to competences (i.e. responsiveness and reliability) are better assessed than those associated with values (i.e. integrity, openness and fairness).

Respondents were asked how likely or unlikely certain events or conditions were in the case of public institutions in New Zealand. The analysis links overall levels of trust with the drivers of trust for three institutions: the public service; local government as represented by local government councillors; and the parliament. The logistic regressions use as dependent variables people who trust or do not trust (the three institutions) and as explanatory variables questions on the determinants of trust as well as controls for socioeconomic characteristics (See Box 2.5).

Box 2.5. Specification of the model on the drivers of trust in public institutions implemented in New Zealand

The empirical analysis of the drivers of trust is based on logistic regressions. Institutional trust is separately measured using three different variables: trust in the public service, trust in parliament and trust in local government councillors. The survey question is phrased as follows: “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is not at all and 10 is completely, how much do you trust each of the following?”. The dependent variable is recoded as a dummy. It takes value 0 for responses 0-4 on the original 11-points scale, and value 1 for responses 6-10. Response 5, "Don't know" and people who didn’t answer are excluded. Stepwise regressions are used as a data reduction method that allows identifying variables that will feed into the final logistic regression.

Based on the OECD framework, trust is expected to be mainly driven by respondents’ perceptions of responsiveness, reliability, openness, integrity, and fairness of government and public institutions. These five dimensions are operationalized utilizing 12 variables, originally measured on a 0-10 scale that were then standardized. In addition to these, the main set of predictors includes 5 variables measuring respectively: internal and external efficacy (both on an 11-points scale), satisfaction with administrative services (same scale), and confidence in one’s country’s ability to respond to tackle environmental challenges.

All models include the following control variables: socio-demographics (age, gender, education, interpersonal trust, perception of economic insecurity and ethnicity) they are all estimated using survey weights. Missing data are excluded using listwise deletion.

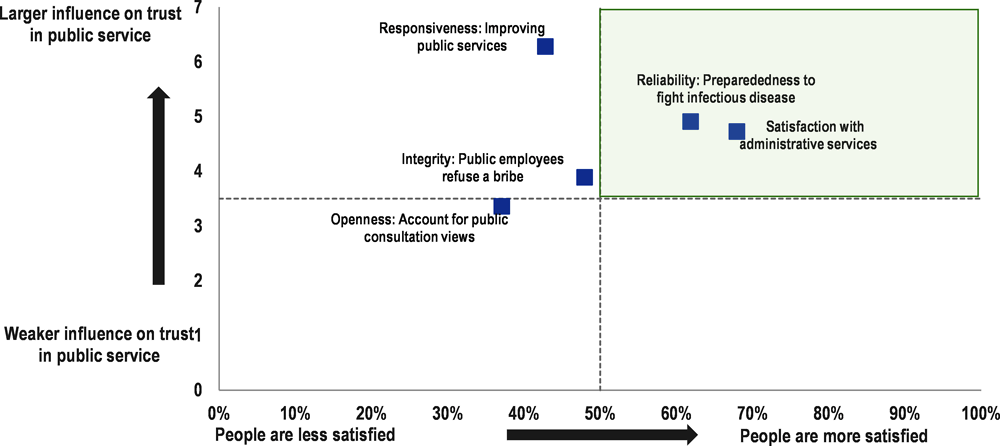

2.9.1. Trust in the public service

Figure 2.18 shows the main drivers of trust in the public service in New Zealand. Responsiveness, as the extent to which public institutions will address people’s concerns about services, has the highest potential impact on trust in the public service. According to the survey, 42.7% of respondents expect that if a service is working badly and people complain about it, it will be improved. Moving from the typical New Zealander to one with slightly higher confidence (one standard deviation increase) could lead to an increase in trust in the public service by 6.3 percentage points (see Figure 2.18).

The driver with the second highest explanatory power for trust in the public service is government preparedness to protect people's lives in a future pandemic. Trust in the public service could increase by almost 5 percentage points if moving from the typical respondent to one with a slightly higher perception of government preparedness. As discussed in Chapter One, New Zealand’s response to the pandemic has been praised internationally and led to one of the lowest mortality rates around the globe. Not surprisingly – bearing in mind the COVID-19 experience – 61.8% of respondents in New Zealand consider the government to be prepared to cope with a future pandemic. Still, New Zealand remains confronted with a wide variety of risks including those deriving from climate change that call for strengthened reliability and effective disaster management plans (See Chapter 3).

Satisfaction with administrative services is the factor with the third highest explanatory power for trust in the public service in New Zealand. At a comparatively high level of 68% satisfaction with administrative services, it remains an important lever to preserve and strengthen trust in the public service. Shifting from the typical respondent on this variable to one with slightly higher confidence could lead to an increase in trust of 4.7 percentage points in trust in the public service.

While elements of competence remain the strongest predictors of trust in the public service some indicators associated with government values have additional explanatory power. Less than half (48.4%) of the New Zealand population expects that public servants will refuse a bribe to speed up access to an administrative service. Improvements on this variable from the typical respondent to one with a higher perception that bribes are refused will result in an increase in trust of about 3.9 percentage points. Elements of openness, related to the incorporation of public feedback received in public consultations, is also statistically significant, and improvements in this dimension could lead to positive changes in trust of about 3.4 percentage points (See Figure 2.18).

Figure 2.18 Service responsiveness has the highest explanatory power for trust in the public service

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in public service in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics and self-reported levels of interpersonal trust. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%, except responsiveness which is statistically significant at 95%. Only questions derived from the OECD Trust Framework are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, which also may be statistically significant, are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

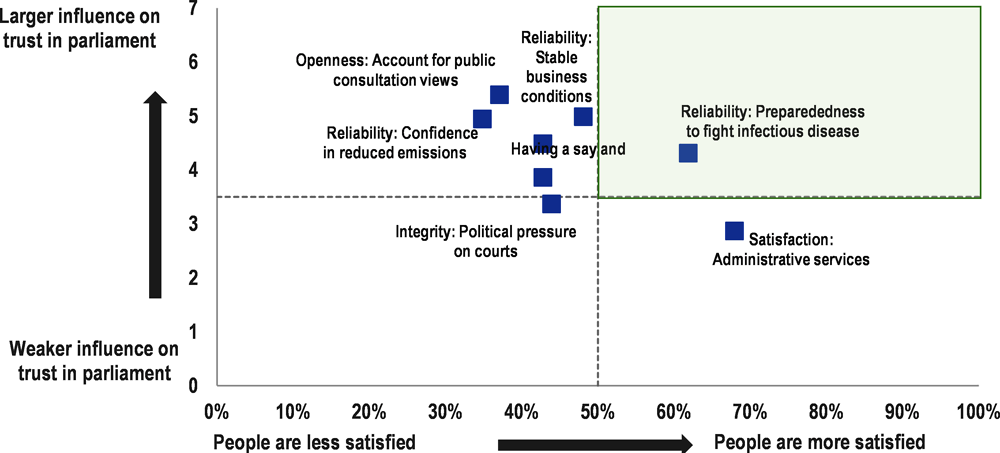

2.9.2. Trust in the parliament

The second institution for which the analysis on the drivers of trust was carried out is the New Zealand Parliament. Figure 2.19 shows factors that turned out significant for levels of trust in the national parliament. The factors with the highest relative weight relate to whether or not people think their voices will be heard. People's expectations that their opinions expressed in public consultations has the highest potential impact on trust in the national parliament. Political efficacy, or the extent to which people think they have a say in what the government does, also has a relatively high potential impact on trust in the parliament. Improving external political efficacy from the typical respondent to one with a slightly higher level on this variable could lead to improvements in trust of about 4.5 percentage points, keeping all other things equal.

The second group of variables with a relatively high explanatory power on trust in parliament are related to reliability. Increasing people’s confidence on public institutions’ ability to deliver on climate change targets could increase trust levels by about 5 percentage points, keeping everything else equal. Another dimension of reliability with the potential of increasing public trust substantially refers to the stability of business conditions. Improvements on this component could result in a potential increase in trust of about 5 percentage points. Other components of reliability such as the extent to which institutions are prepared to fight future crises or satisfaction with administrative services are also significant. Yet, the starting point, i.e. the current level of these components, is much higher, 61.8% and 67.9% respectively (See Figure 2.19).

Figure 2.19. Political efficacy and reliability are key determinants of trust in the parliament

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in parliament in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics and self-reported levels of interpersonal trust. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%. Integrity is statistically significant at 95%. Only questions derived from the OECD Trust Framework are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, which also may be statistically significant, are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

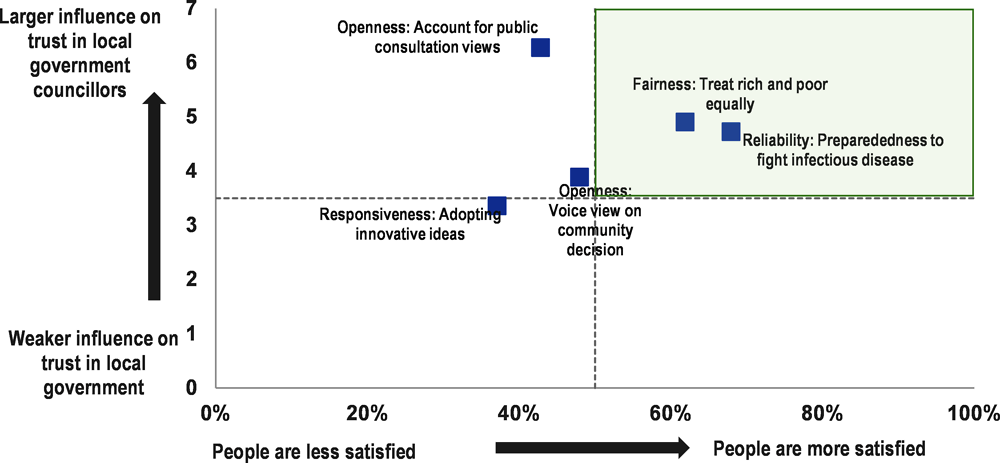

2.9.3. Trust in local government councillors

Figure 2.20 presents significant factors explaining trust in local government councillors. Elements of openness, such as having the opportunity to voice concerns on local issues and expecting that opinions expressed in public consultations will be considered, are significant. The latter is the factor with the highest relative impact, moving from the average respondent to one with a slightly higher score on this question could improve trust in local government councillors by 6.6 percentage points. Improvements in the expectations of fair treatment of people from different income levels has the potential to influence trust in local government councillors by 5.4 percentage points, the second highest relative contribution for trust in local government councillors.

Figure 2.20. Openness and fairness are also key determinants of trust in the local government councillors

Note: The figure shows the most robust determinants of self-reported trust in local government councillors in a logistic estimation that controls for individual characteristics and self-reported levels of interpersonal trust. All variables depicted are statistically significant at 99%. Responsiveness is statistically significant at 95%. Only questions derived from the OECD Trust Framework are depicted on the x-axis, while individual characteristics such as age, gender, education, which also may be statistically significant, are not shown.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

2.9.4. Comparative analysis on the drivers of trust in public institutions in New Zealand

Table 2.5 shows the determinants of trust in the public service, parliament and local government councillors and highlights these determinants that are significant across the three studied institutions. The positive sign within brackets indicates the institution for which the coefficient is largest when compared to the other two institutions. Improving service responsiveness and satisfaction with administrative services have a higher relative effect for trust in the public service. Preparedness to fight a future pandemic has a slightly larger coefficient for trust in local government councillors, although differences are not very large. Aspects related to openness, specifically expectations about people’s voices being heard, are significant for the three institutions analysed and has a relatively higher effect for trust in the public service.

Several control variables are included in the regressions and only interpersonal trust is consistently significant across all institutions. Feelings of economic insecurity expressed by financial concerns have also a significant effect on trust in the parliament. This is not surprising as the parliament can directly influence people’s lives through policies and choices and is sought after for responses on societal and economic issues. While there is diversity within groups, ethnicity and specifically being Māori has a weakly significant effect in trust in the public service in turn being Asian weakly influences trust in the parliament. Qualitative survey responses signal aspects related to economic insecurity and vulnerabilities as an additional lever of trust in public institutions (See Box 2.4).

Table 2.5. Comparison of the drivers of trust in public institutions in New Zealand

|

|

Trust in the public service |

Trust in the parliament |

Trust in local government councillors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Personal characteristics |

|||

|

Age |

|||

|

Gender |

|||

|

Education |

|||

|

Financial concerns |

|||

|

Interpersonal trust |

|||

|

Ethnicity (Māori) |

|||

|

Ethnicity (Asian) |

|||

|

Drivers of trust in public institutions |

|||

|

Courts independence (integrity) |

|||

|

Refusing bribes (integrity) |

|||

|

Improving services (responsiveness) |

(+) |

||

|

Adopting innovative ideas (responsiveness) |

|||

|

Preparedness to fight a new disease (reliability) |

(+) |

||

|

Stability of regulatory conditions (reliability) |

|||

|

Confidence reduce emissions (reliability) |

|||

|

Voicing views local issues (openness) |

|||

|

Opinions in public consultations considered (openness) |

(+) |

||

|

Equal treatment income (fairness) |

|||

|

Satisfaction administrative services (reliability) |

(+) |

||

|

Political efficacy (having a say) |

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

This chapter presented the results of the survey on the drivers of trust in public institutions in New Zealand and discussed additional factors that can influence trust in years to come. Based on these and other quantitative results as well as the analysis of the interviews carried out with over 50 representatives from public institutions, civil society, ethnic communities and academia in New Zealand, the following chapter will discuss the type of actions that can be undertaken to preserve and strengthen trust in public institutions in New Zealand.

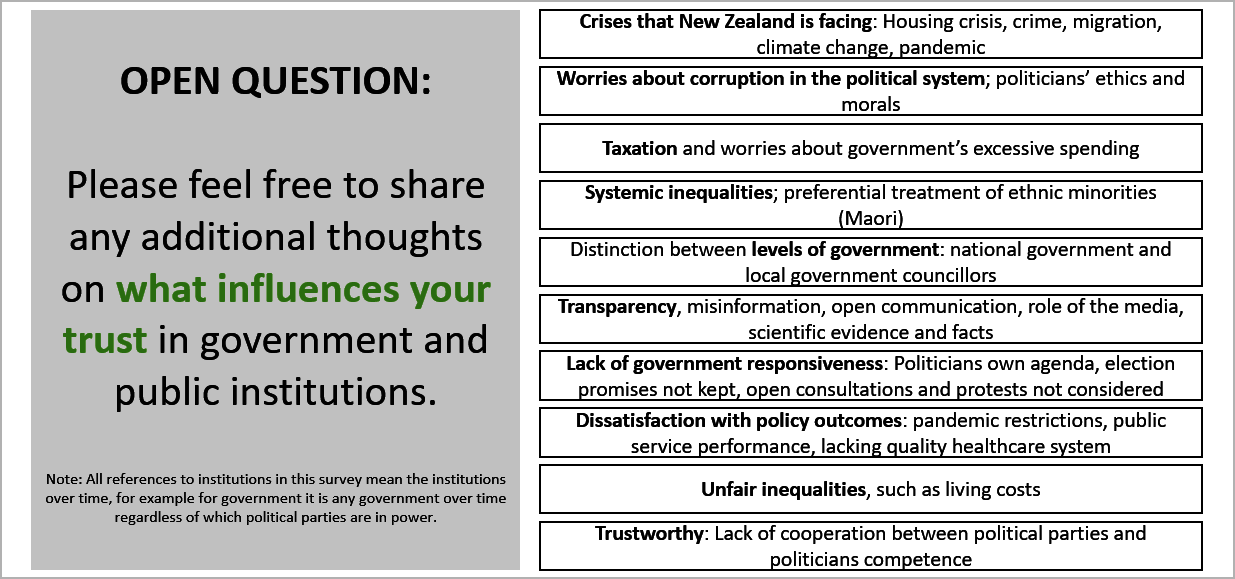

Box 2.6. Drivers of Trust: Open-Ended Survey Responses in New Zealand

The OECD Trust Survey included an open-ended survey question asking about influences in people’s trust in public institutions: ’’Please feel free to share any additional thoughts on what influences your trust in government and public institutions.’’ The answer to the open-ended survey question was voluntary and respondents could elaborate in a text box on their ideas and perceptions of influencing factors in trust. The open-ended survey question was added to the survey questionnaire in 17 out of 22 OECD countries that participated in the OECD Trust Survey to build on quantitative measurements of drivers of trust in public institutions and to add qualitative evidence about trust in the government and public institutions. 23% of respondents in New Zealand answered the open-ended survey question with valuable survey responses, slightly fewer respondents compared to the other OECD average (29% of respondents across surveyed OECD countries answered the open-ended survey question).

The open-ended survey answers were grouped in topics based on respondents’ use of similar words in the survey response. In a cross-country comparison, the housing crisis and increasing crime were issues that were more frequently mentioned in New Zealand, whereas corruption was much less frequently named to influence trust than in other surveyed countries. Systemic inequalities and the preferential treatment of ethnic minorities were specific concerns of respondents in New Zealand. Regarding international issues, many people expressed concerns with New Zealand’s role in international collaboration and climate change and were sceptical that a small country like New Zealand could contribute to both in a sufficient manner, which respondents from other smaller sized countries mentioned as well.

Source: OECD Trust Survey (http://oe.cd/trust)

2.10. Opportunities to upgrade measures of trust to build a robust evidence base

The Kiwis Count Survey is one of the primary ways by which the PSC monitors levels of confidence in public sector agencies (See Box 1.1). The survey is a commendable effort to measure customer satisfaction with services on a regular basis and report on trust in government. Nonetheless, questions on trust included in the Kiwis Count are based on the respondent’s trust in the public service brand or on most recent personal interaction with a Public Service agency. This inevitably excludes many of the most important drivers of trust. It is recommended that the Public Service Commission revises the Kiwis Count Survey to improve the relevance and comparability of the data that it collects. Key priorities in the revisions should be preserving valuable time series, improving comparability of data collected, improving the relevance and usefulness of the data collected, and minimising respondent burden. Measures of the expected responsiveness of services, the reliability of long-term policies, engagement opportunities and perceived integrity and fairness can allow monitoring the effects of different policies and actions over time as well as their relationship to trust levels. Accordingly, questions included in the Kiwis Count Survey can be complemented with measures that align with the OECD Survey on the Drivers of Trust in Public Institutions. In turn, building a time series on questions on the drivers will allow monitoring the effects of different policies and actions over time.

There are recurrent trust gaps between several societal groups: Māori, younger people, people outside the large urban areas, the less educated and those with lower income have consistently lower levels of trust in institutions. Indicative evidence suggests that there is important variation when looking jointly at socioeconomic characteristics within populations groups (e.g. ethnicity and education or income levels). Having samples that are sufficiently large to combine different socioeconomic characteristics (e.g. ethnicity and education level) may contribute to give visibility to wells of distrust and better target actions to engage with them.

References

[8] Algan, Y. (2018), The rise of populism and the collapse of the left-right paradigm: Lessons from the 2017 French presidential election.

[31] Algan, Y. and P. Cahuc (2010), “Inherited Trust and Growth”, American Economic Review, Vol. 100/5, pp. 2060-2092, https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.5.2060.

[7] Ananyev, M. and S. Guriev (2018), “Effect of Income on Trust: Evidence from the 2009 Economic Crisis in Russia”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 129/619, pp. 1082-1118, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12612.

[29] Arrow, K. (1972), “Gifts and Exchanges”, Philosophy and Public Affairs, pp. 343-362.

[30] Auty, R. and H. Furlonge (2019), “The Rent Curse: Natural Resources, Policy Choice, and Economic Development”, Oxford University Oress.

[13] Bäck, M. and E. Kestilä (2009), “Social Capital and Political Trust in Finland: An Individual-level Assessment”, Scandinavian Political Studies, Vol. 32/2, pp. 171-194, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2008.00218.x.

[35] Bjornskov, C. and P. Meon (2015), “The Productivity of Trust”, World Development, Vol. 70, pp. 317-331.

[3] Brezzi, M. et al. (2021), “An updated OECD framework on drivers of trust in public institutions to meet current and future challenges”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 48, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6c5478c-en.

[39] Brown, M., R. Peart and M. Wright (2016), Evaluating the environmental outcomes of the RMA, Environmental Defence Society.

[41] Corlett, E. (2020), Fresh Water Scientist Dr. Mike Joy concerned about Agriculture Minister’s Water Comments, https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/410118/fresh-water-scientist-dr-mike-joy-concerned-about-agriculture-minister-s-water-comments.

[33] Coyle, D. and S. Lu (2020), “Trust and Productivity Growth - An Empirical Analysis”, Working Paper.

[27] Easton, B. (2019), What can we learn from the 2018 Census debacle?, https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/396968/what-can-we-learn-from-the-2018-census-debacle.

[38] Fischer, S. (2022), “A Review of Current Regional-Level Environmental Monitoring: Reporting and Enforcement in Aotearoa New Zealand”, Policy Quarterly, pp. 28-35.

[25] Goren, E. (2013), “Economic effects of domestic and neighbouring countries’ cultural diversity”, Oldenburg Discussion Papers in Economics.

[40] Gudsell, K. (2017), Water Fools? - Greening of the McKenzie Country, https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/water-fools/story/201840679/water-fools-greening-of-mackenzie.