Growth in Emerging Asia is showing resilience in the face of great economic uncertainty. The countries of the region – ASEAN-10 countries, the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) and India – have stood up well in the face of uncertainties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, weaker external demand, and inflationary pressures. The export sector helped boost economic growth and keep up the momentum of the region’s economies, though momentum is weakening recently. Inflation combined with interest rate differentials among countries increase the volatility of capital flows and put pressure on currencies in the region. Supply issues threaten food security and make goods and services more expensive, which can weigh on both external and domestic demand. The return of tourists will bolster economies. The reopening of China following its abandonment of zero-COVID policy will serve to counterbalance some of these challenges.

Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2023

Chapter 1. Macroeconomic assessment and economic outlook in Emerging Asia

Abstract

Introduction

Growth in Emerging Asia is showing resilience in the face of global economic uncertainty. The countries of the region – ASEAN-10 countries plus China and India – have stood up well in the face of great uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, weaker external demand, and inflationary pressures. The export sector helped boost economic growth and maintain the momentum of the region’s economies, though it has weakened recently.

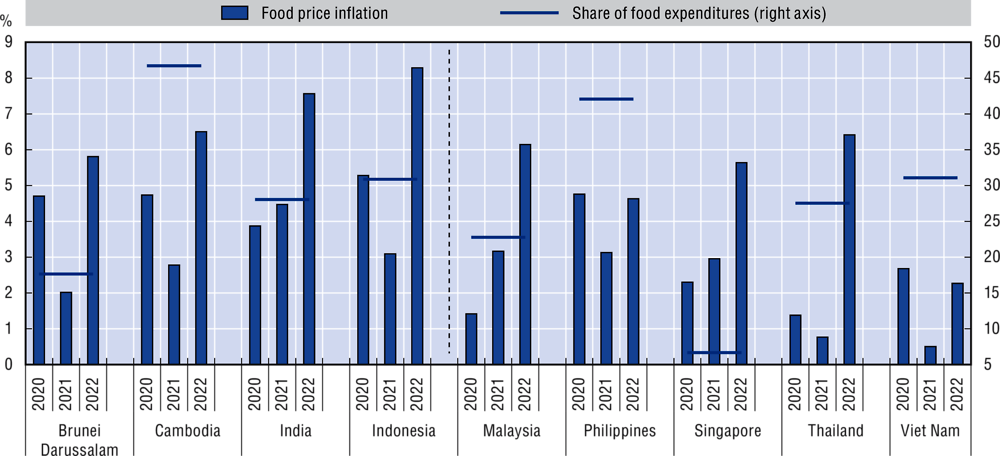

External demand for Emerging Asian goods is expected to weaken due to a global economic slowdown. Persistent inflationary pressures, including higher energy and food prices and high interest rates in advanced economies have put pressure on capital flows and local currencies in the region. Food security for specific items could also be a concern, while ongoing supply-side bottlenecks could continue to cause difficulties and lead to higher prices for goods and services.

The pandemic has also significantly impacted the service accounts of regional economies, and it will take time that the activities of sector return to pre-pandemic levels. The tourism and transport industry may face challenges to find a new strategy to cope with a surge in demand for travel.

This chapter first reviews the main findings concerning the economic outlook for Emerging Asia over the coming year. It then discusses near-term economic trends for the region’s 12 countries. Finally, it explores challenges and risks to robust growth in the region.

Overview and main findings

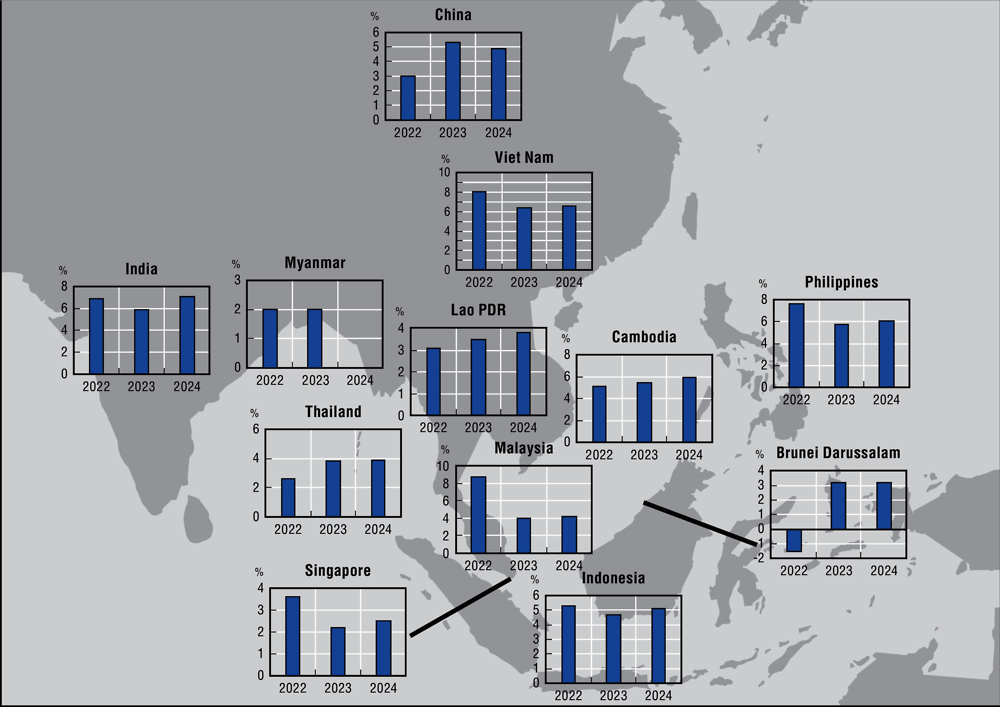

In 2022, Emerging Asia recorded GDP growth of 4.4%. This can be attributed to a combination of factors such as appropriate monetary policy reactions, strong export performance and robust domestic demand. The average GDP growth rate for Emerging Asian countries is expected to increase to 5.3% in 2023 and to 5.4% in 2024, according to the projections of the OECD Development Centre. Growth in Southeast Asian countries is expected to average 4.6% in 2023 and 4.8% in 2024, weaker than in 2022, but showing resilience. Amid slowing global growth, China’s abandonment of zero-COVID policy and subsequent border reopening is a positive development for growth in the region (Table 1.1).

The main findings of this year’s Outlook include the following:

Growth in Emerging Asian economies have shown resilience amid global economic uncertainty. Most economies in the region will keep their growth momentum in 2023, with growth expected to average 5.3% in Emerging Asia as a whole and 4.6% in Southeast Asia.

Strong trade and goods exports have supported most Emerging Asian economies in 2022. However, the current economic uncertainties and slowing global growth is expected to weaken external demand. This is expected to be offset to some extent by China’s abandonment of zero-COVID policy and reopening of its borders. FDI declined in 2022 but there are signs of recovery in 2023.

Financial markets exhibit resilience despite volatility and risks. The banking sector needs to be carefully monitored in the current high-inflation environment.

As for risks to growth, inflationary pressures are a concern for many countries in the region, though the level is moderate compared to the level in OECD countries. The long inflationary episode has also spurred capital flow volatility in the region. Currency depreciation pressures that began in Q3 2022 have since eased but should be monitored carefully. The effects on fertiliser and food threaten food security, with particular concern caused by the current volatility in grain markets.

Slowing global growth will weaken demand in Emerging Asia, although there are some positive signs in the global economy.

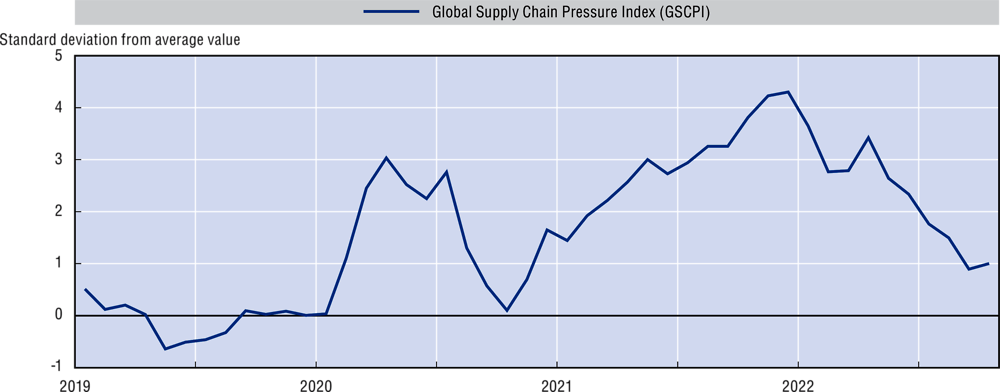

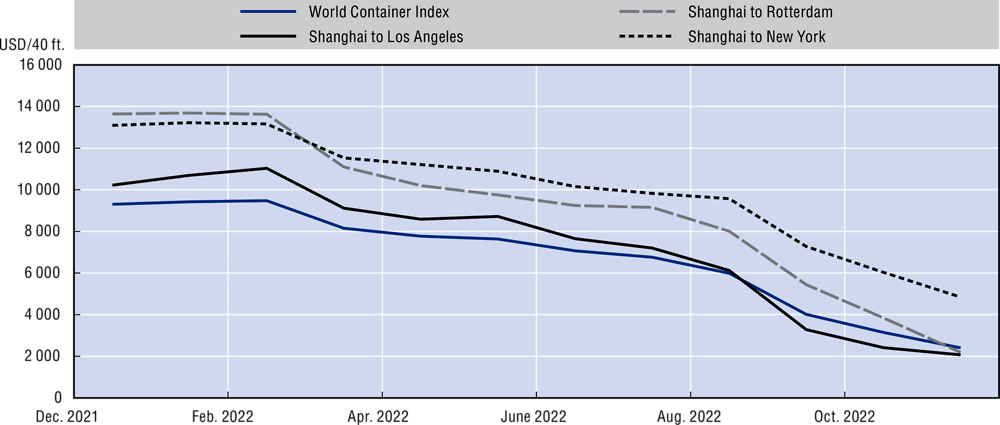

Supply-side bottlenecks developed during the COVID-19 pandemic due to restrictions and the war in Ukraine remain. Supplies of semiconductors, electronics, and transportation equipment have been most affected by both waves of bottlenecks.

Tourism will continue to recover with travel restrictions mostly gone. However, the earlier restrictions thinned the tourism workforce and tourism sector must adapt to various challenges such as diversifying inbound markets, promoting domestic tourism and stabilising labour market. Promoting sustainable tourism and effective use of digital tools is crucial.

Table 1.1. Real GDP growth in Southeast Asia, China and India, 2021-24, percentage

|

|

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ASEAN-5 |

||||

|

Indonesia |

3.7 |

5.3 |

4.7 |

5.1 |

|

Malaysia |

3.1 |

8.7 |

4.0 |

4.2 |

|

Philippines |

5.7 |

7.6 |

5.7 |

6.1 |

|

Thailand |

1.5 |

2.6 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

|

Viet Nam |

2.6 |

8.0 |

6.4 |

6.6 |

|

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore |

||||

|

Brunei Darussalam |

-1.6 |

-1.5 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

|

Singapore |

8.9 |

3.6 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

|

CLM countries |

||||

|

Cambodia |

3.1 |

5.1 |

5.4 |

5.9 |

|

Lao PDR |

3.5 |

3.1 |

3.5 |

3.8 |

|

Myanmar |

-17.9 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

- |

|

China and India |

||||

|

China |

8.1 |

3.0 |

5.3 |

4.9 |

|

India |

8.7 |

6.9 |

5.9 |

7.1 |

|

Average of ASEAN-10 |

3.2 |

5.6 |

4.6 |

4.8 |

|

Average of Emerging Asia |

7.3 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

5.4 |

Note: Data cut-off date is 20 March 2023. Data for India and Myanmar relate to fiscal years. 2024 projection for Myanmar is not available. Projections of regional averages (both ASEAN and Emerging Asia) for 2024 exclude Myanmar. The 2023 and 2024 projections for China, Indonesia and India, are based on the OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2023.

Source: OECD Development Centre.

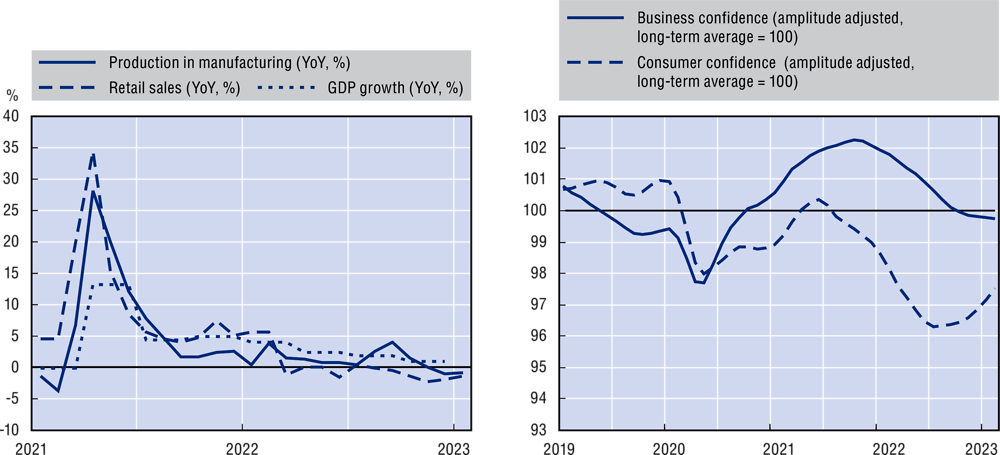

Recent developments and near-term outlook

Despite the current global economic uncertainties and slowing global economic growth, Emerging Asia is expected to experience robust growth in 2023 and 2024. Growth momentum in Southeast Asia in 2023 is expected to be weaker than in 2022, but showing resilience. (Figure 1.1). The ASEAN-5 countries, which includes Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam, experienced stable GDP growth in the last two quarters of 2022. Brunei Darussalam experienced a contraction in the first half of 2022 but rebounded in the third quarter. Singapore’s growth rate moderated in the last quarter of 2022, while China’s growth remained largely steady in the last two quarters of 2022. India’s growth rate moderated in Q4 2022 after a strong rebound in earlier quarters. All economies experienced a slowdown in the fourth quarter (Table 1.2).

Figure 1.1. Growth in real GDP in Southeast Asia, China and India: Comparison between growth rates for 2022, 2023 and 2024

Note: Data cut-off date is 20 March 2023. Data for India and Myanmar relate to fiscal years. 2024 projection for Myanmar is not available. The 2023 and 2024 projections for China, Indonesia and India are based on the OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2023.

Source: OECD Development Centre.

Table 1.2. Quarterly real GDP growth in Southeast Asia, China and India, Q1 2021 to Q4 2022

Year-on-year percentage changes

|

|

Q1 2021 |

Q2 2021 |

Q3 2021 |

Q4 2021 |

Q1 2022 |

Q2 2022 |

Q3 2022 |

Q4 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ASEAN-5 |

||||||||

|

Indonesia |

-0.7 |

7.1 |

3.5 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.5 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

|

Malaysia |

-0.5 |

15.9 |

-4.5 |

3.6 |

5.0 |

9.0 |

14.2 |

7.0 |

|

Philippines |

-3.8 |

12.1 |

7.0 |

7.8 |

8.2 |

7.5 |

7.6 |

7.2 |

|

Thailand |

-2.4 |

7.8 |

-0.2 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.5 |

4.6 |

1.4 |

|

Viet Nam |

4.7 |

6.7 |

-6.0 |

5.2 |

5.1 |

7.8 |

13.7 |

6.0 |

|

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore |

||||||||

|

Brunei Darussalam |

-1.3 |

-1.9 |

-1.8 |

-1.4 |

-4.2 |

-4.4 |

0.9 |

N/A |

|

Singapore |

3.9 |

17.3 |

8.7 |

6.6 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

2.1 |

|

China and India |

||||||||

|

China |

18.7 |

8.3 |

5.2 |

4.3 |

4.8 |

0.4 |

3.9 |

2.9 |

|

India |

3.4 |

21.6 |

9.1 |

5.2 |

4.0 |

13.2 |

6.3 |

4.4 |

Note: Data as of 20 March 2023. Data for Q4 2022 were unavailable for Brunei Darussalam. Data for India relate to fiscal years ending in March. The measurement method of real GDP growth for Viet Nam was changed as of Q1 2021.

Source: CEIC and national sources.

ASEAN-5

Indonesia

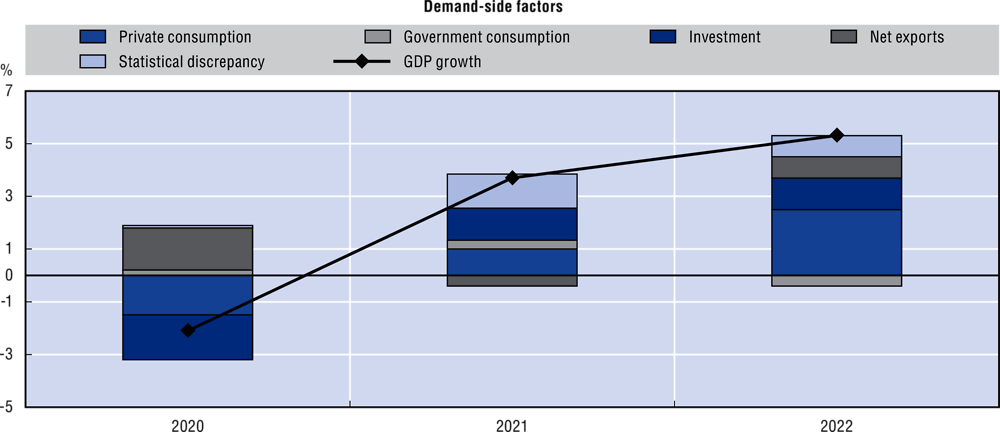

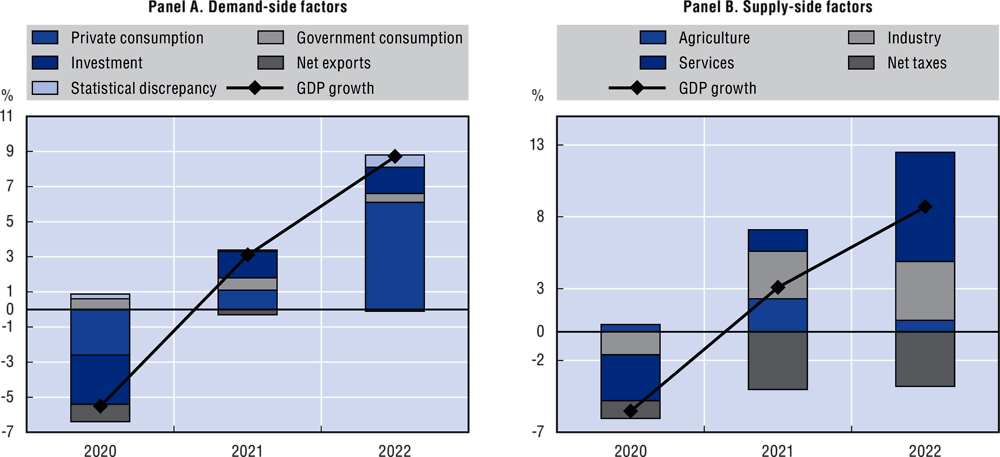

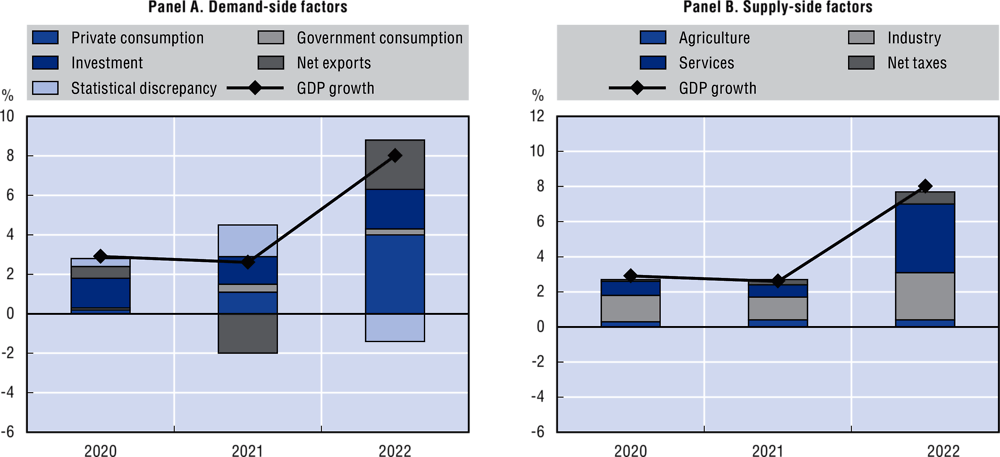

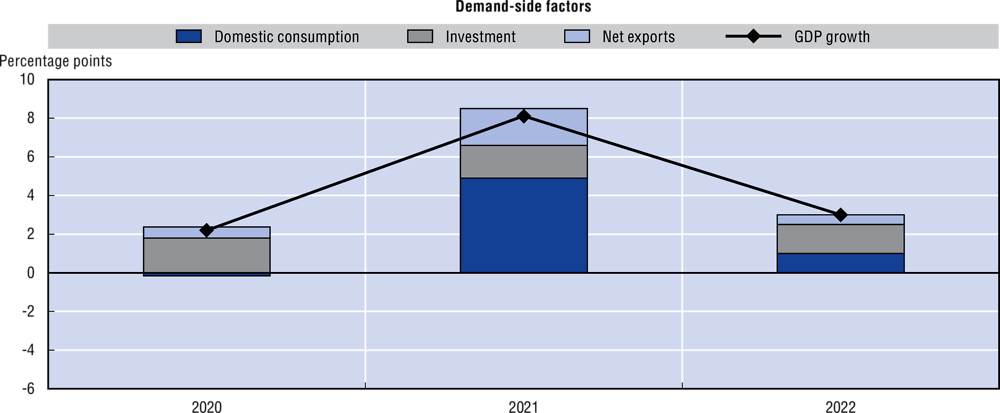

Economic activity in Indonesia rebounded in 2022 after a slowdown in 2021. By continuing to implement various reforms, Indonesia could build resilience to economic shocks. Growth in real GDP reached 5.3% in 2022 on an annual basis. The continued recovery from the recession of 2020 was mostly driven by strong domestic consumption, followed by investment and net export growth (Figure 1.2). On the supply side, growth was supported by all sectors, led by industry and followed by strong growth in services, which continued to be supported by further expansion of tourism-related activities. In 2023, Indonesia’s real GDP growth will moderate to 4.7% and is projected to reach 5.1% in 2024.

Figure 1.2. Contribution to GDP growth in Indonesia, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Higher inflation will undermine private consumption growth in Indonesia. Goods exports are projected to remain robust despite the expected global growth slowdown, thanks in part to growth in mining and metal-processing production. At the same time, as a large commodity exporter, Indonesia will benefit from rising commodity prices, to some extent.

The war in Ukraine has provoked a shortage of raw materials, notably coal, and led importing countries to seek alternative sources, resulting in higher demand for Indonesian exports. Indonesia’s non-oil and gas exports, which make up more than 80% of its total goods and services exports, grew in 2022. This increase contributed to an overall rise in exports. It is expected that service exports from Indonesia will bounce back in tandem with the recovery of the tourism sector, particularly with the expected rise in tourism demand from China now that its border has reopened. Gross capital formation increased by 5.0% in 2022, driven in part by FDI. Several policy reforms will assist the expansion of capital-intensive industries such as metals, chemicals, machine components and auto manufacturing.

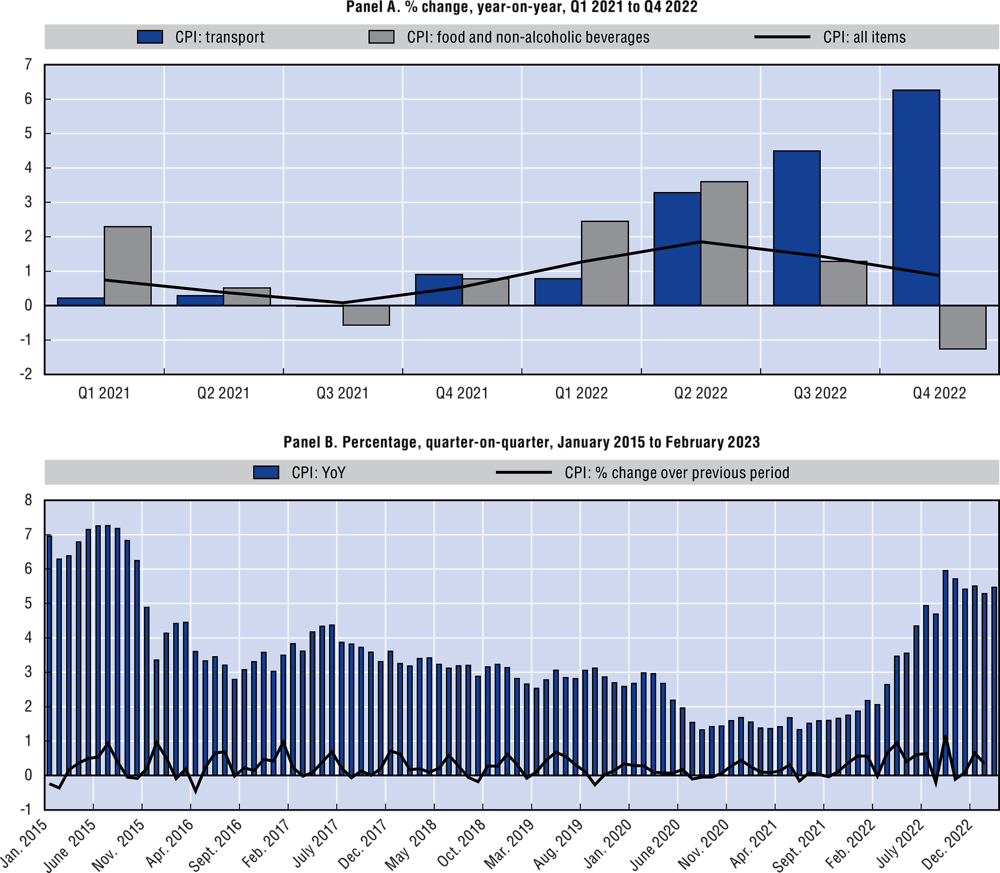

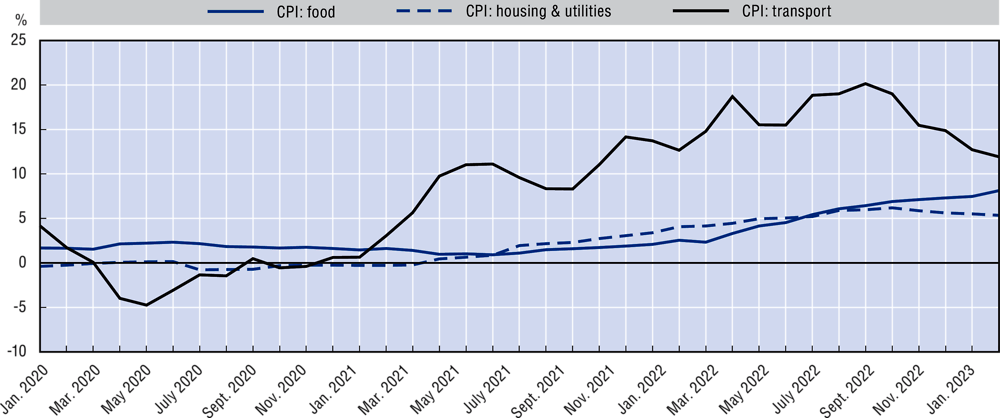

Higher food and fuel prices in Indonesia in 2022 resulted in an acceleration of inflation (Figure 1.3). The government had previously controlled inflation during the pandemic through extensive automotive fuel subsidies, but these were reduced in September 2022. Transport prices jumped by 16% year-on-year in October 2022, the highest such increase on record, but moderated to 13.6% in February 2023. In February 2023, both headline and core inflation fell slightly to 5.5% and 3.1%, respectively. Inflation will remain relatively high in the near term.

Figure 1.3. Consumer price inflation for Indonesia

In the second half of 2022, Indonesia’s central bank embarked on a series of interest rate hikes to combat inflation and stem capital outflows, which resulted mainly from monetary tightening by the US Federal Reserve. Indonesia’s central bank has been selling short-term bonds since July 2022 to absorb any excess liquidity in the financial market and support the local currency. It has also been purchasing long-term bonds to sustain low borrowing costs, despite hikes in the main policy rate.

In terms of fiscal situation, there was a deterioration in fiscal balance in 2020, due to fiscal measures related to COVID-19 pandemic but the deficit improved to 4.6% in 2021, and subsequently narrowed in 2022. Income tax adjustments were made at both ends of the scale, with increases in the minimum tax threshold and the tax rate for higher earners. In April 2022, value-added tax (VAT) was increased from 10% to 11% and the corporate tax rate was reduced from 25% to 22%.

While high inflation and interest rates will weigh on private consumption and investment in 2023, Indonesia’s mining sector will continue attracting investment and expanding. Indonesia has given significant attention to disaster resilience in recent years, developing customised response plans for different areas of the country.

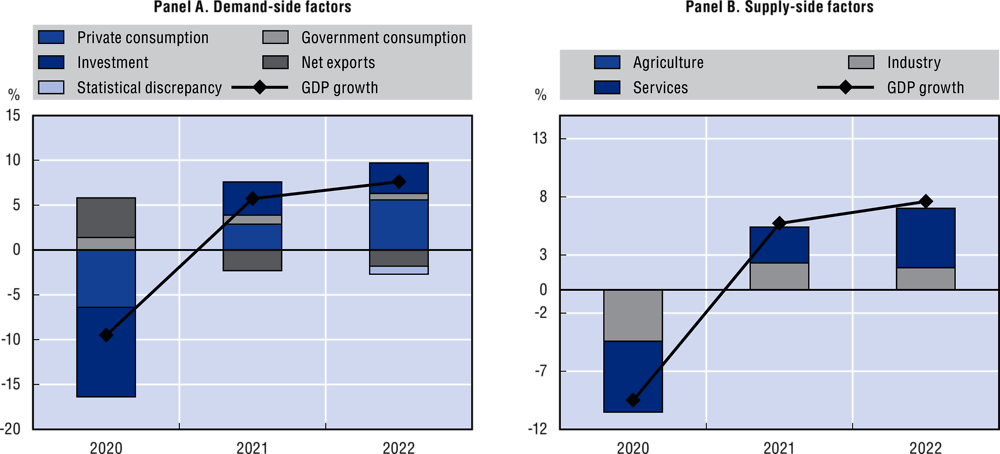

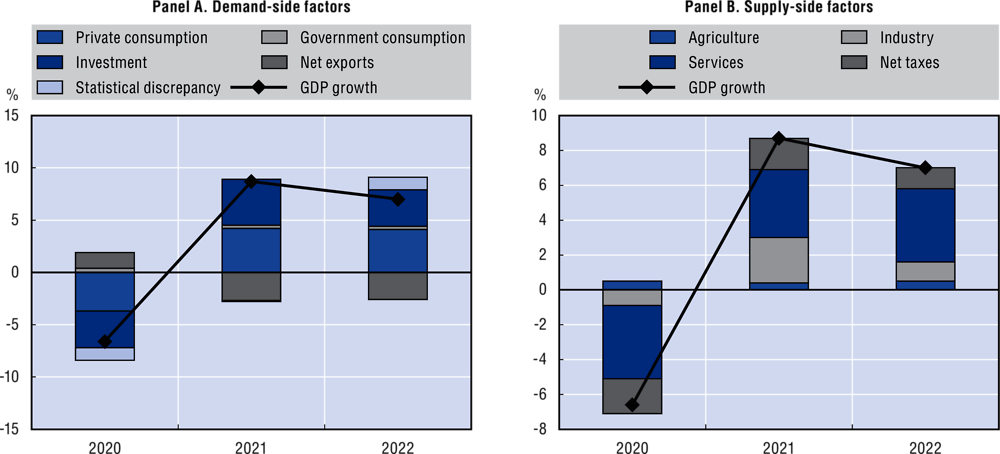

Malaysia

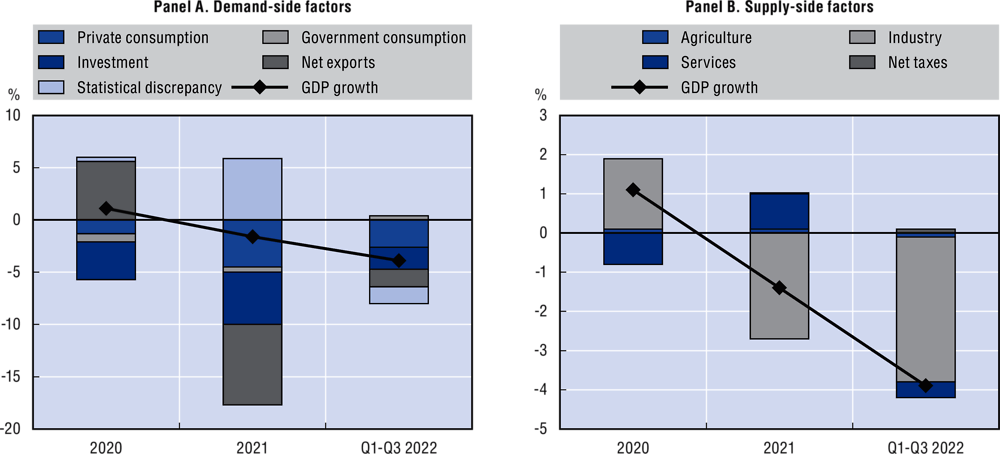

Malaysia’s real GDP grew by 8.7% in 2022, the strongest growth recorded in the region together with Viet Nam. The economy benefited from a strong increase in domestic consumption (Figure 1.4, Panel A). On the supply side, services contributed the most to economic growth in 2022 (Figure 1.4, Panel B). In 2023 and beyond, the primary driver of Malaysia’s economic growth will continue to be private consumption. Given the environment of low consumption taxes, the purchasing power of households will remain relatively strong. However, a high level of household debt is vulnerable to interest rate hikes.

Figure 1.4. Contribution to GDP growth in Malaysia, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Malaysia’s real GDP growth is forecast to slow to 4.0% in 2023. Slowing global economic growth will weigh on external demand in 2023. Similarly, local demand will be expected to decline because of monetary policy tightening and lower investment.

An anticipated return of international visitors to Malaysia in 2023 will boost service-sector activities, especially since China, Malaysia’s largest source of tourists, abandoned its zero-COVID policy in December 2022.

Malaysia is expected to benefit from higher demand for components such as semiconductors, although these are produced using imported inputs and any rise in export demand will also increase imports. Malaysia is expected to benefit from increased demand for liquefied natural gas (LNG) in 2023. In 2021, Malaysia was one of the world largest exporters of LNG, and it will remain one of the largest exporters of this commodity as it steps in to replace LNG exports from Russia.

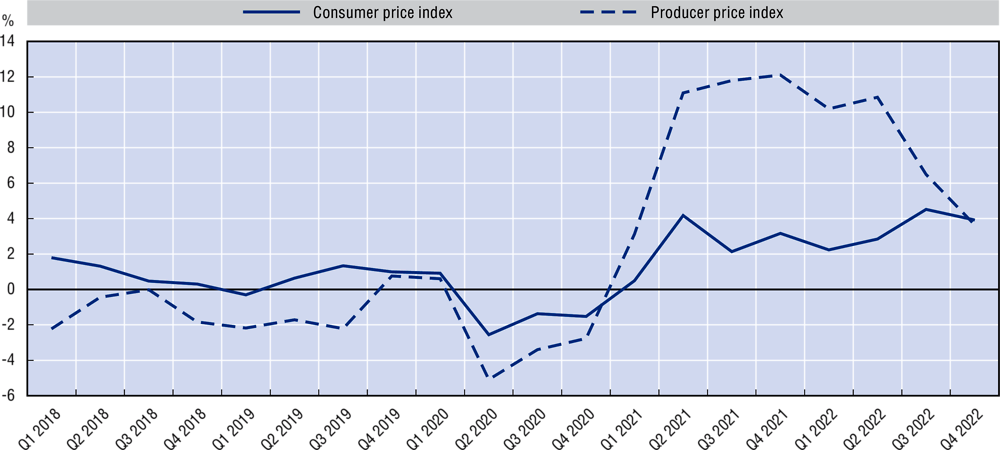

After recording a high of 4.5% in the third quarter of 2022, consumer price inflation fell to 3.9% in the third quarter. Food prices are expected to remain high throughout the year. Although global energy prices will remain high in the near term, they are expected to have a relatively minor impact on Malaysia’s consumer price index as the government subsidises fuel and electricity. Producer price inflation also showed some signs of moderation after reaching 3.6% in the last quarter of 2022 (Figure 1.5), from an average of about 10% throughout most of 2021 and 2022, with the highest level of 12.1% recorded in the fourth quarter of 2021.

Figure 1.5. Consumer price inflation and producer price inflation, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

% change, year-on-year

An interest-rate differential with the United States exerted depreciatory pressures on the Malaysian ringgit. The exchange rate between the ringgit and the US dollar approached a 24-year low in September and October 2022. Central bank interventions in the foreign exchange market provided the necessary support for the local currency.

Although restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic were lifted in Malaysia in April 2022, business sentiment was hurt by rising borrowing costs that followed soon after. The monetary policy tightening cycle in 2022 was the fastest on record, exceeding the cumulative increase of 75 basis points in 2010’s tightening cycle. The central bank began tightening monetary policy in May 2022 by raising the overnight policy rate 25 basis points to curb inflation and normalise rates after the 2020 recession. The rate stood at 2.75% in March 2023.

Labour markets should remain tight in the short term as the return of the economy to full operation creates demand for workers. The tight labour market has also kept spells of unemployment short.

Digital connectivity is improving and state-level disparities are narrowing. The Twelfth Malaysia Plan calls for the implementation of the already developed Pelan Jalinan Digital Negara (JENDELA) plan to expand full 4G coverage to populated areas and Digital Nasional Berhad (DNB), founded to develop 5G networks across Malaysia.

Philippines

Real GDP in 2022 in the Philippines grew by 7.6%. This is especially impressive given the grim outlook for the global economy and the backdrop of rising inflation and interest rates in the second half of 2022.

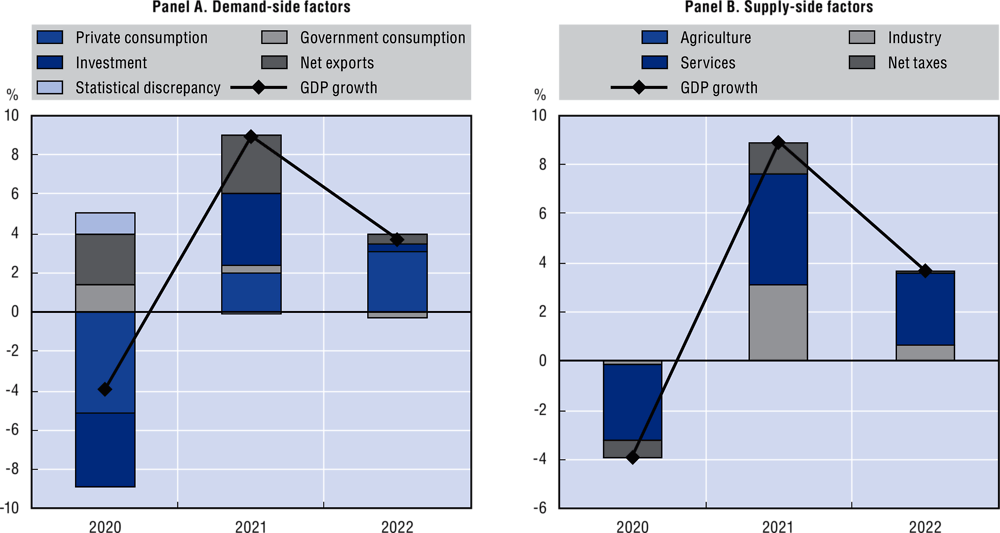

The main support for economic activity continues to come from growth in household spending amid rising employment. Investment and exports grew amid rising domestic demand (Figure 1.6, Panel A). On the supply side, the services sector made the largest contribution to growth (Figure 1.6, Panel B). However, export growth is expected to perform relatively poorly in 2023 by historical standards given the slowing global economic growth, although an increase in economic activity in China following its reopening of its borders will be beneficial. Weaker domestic demand will reduce import growth in 2023.

Figure 1.6. Contribution to GDP growth in the Philippines, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

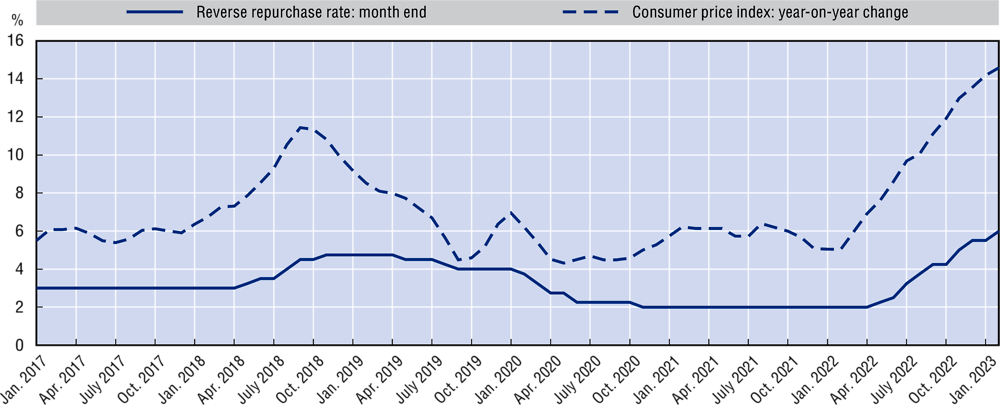

In January 2023, the Philippines experienced a further increase in inflation to 8.7%, up from 8.1% year-on-year in December 2022. This marks the highest annual inflation rate since November 2008 (Figure 1.7). The main drivers of this uptick were increases in the index of housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels, which rose to 8.5% in January 2023 from 7.0% in December 2022, followed by food inflation at the national level, which climbed to 11.2% from 10.6% in the same period. The high food inflation was due to several factors, including increased food input costs, recent typhoons that damaged crops, pressure on local currency and the war in Ukraine. The inflation rate for restaurants and accommodation services, meanwhile, rose to 7.6% in January 2023. Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, increased to 7.4% in January 2023, above the central bank’s target. In marked contrast, core inflation stood at 1.8% in January 2022.

In February 2023, the central bank increased its benchmark interest rate by 50 basis points to 6.0% to contain inflation (Figure 1.7). This is the highest key rate since August 2008 and the central bank signalled further tightening as well. Tighter monetary conditions will weigh on private consumption and investment growth. The Philippine peso is facing depreciation pressures, weighed down by inflationary pressures and an abnormally large interest rate differential with the United States that is driving severe capital outflows.

Figure 1.7. Reverse repo rate and consumer price inflation, January 2017 to February 2023

Note: %, end-period for reverse repo rate and non-seasonally-adjusted % change, year-on-year for consumer price inflation. Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Data from CEIC.

In 2023, the current-account deficit is expected to shrink, primarily due to a decrease in import demand, leading to a narrower goods trade deficit. With the easing of international travel restrictions in China, services exports are likely to surge in 2023 and 2024. Additionally, steadily rising remittance inflows will enlarge the secondary income account.

A labour market rebound was the major driver behind 2022’s economic recovery. In April 2020, unemployment exceeded 17% as many employers fired staff in fear of collapsing demand. The unemployment rate fell steadily as the government gradually lifted restrictions throughout 2022, and now stands at its pre-pandemic level at 5.5%, though underemployment remains highly concerning.

The Build! Build! Build! programme comprises more than 100 infrastructure projects in the areas of transport, water access, disaster resilience and health. The Philippines ratified the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in February 2023.

Thailand

Real GDP in Thailand grew by 2.6% in 2022, up from 1.5% in 2021. Output growth for 2022 was mainly driven by private consumption. Net exports made a significantly higher contribution than in 2021, while private investment also made modest positive contributions (Figure 1.8, Panel A). On the supply side, growth was largely supported by the services sector, while industry made marginal contribution to growth in 2022. The contribution of agriculture was modestly positive (Figure 1.8, Panel B).

Figure 1.8. Contribution to GDP growth in Thailand, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: The calculations are based on chain linked volume measure series. Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Economic growth is expected to accelerate from 2.6% in 2022 to 3.8% in 2023, mostly supported by rebounding private consumption and an increase in tourism. Foreign tourists are expected to return at a faster pace in 2023 after the full reopening of borders. The Thai government had begun working on policies to attract more high-income, long-stay tourists prior to China’s decision to abandon its zero-COVID policy. Weaker demand from major trading partners and effects of the war in Ukraine are likely to slow export growth in 2023.

Foreign investment in Thailand is expected to increase in 2023, but these efforts will be somewhat restrained by ongoing supply-chain disruptions, leading to higher manufacturing and agricultural costs. The risk of disruptions in the supply of integrated circuits would affect Thai automobile exports. Nonetheless, Thailand has a well-diversified export structure, including the electronics, automotive and agricultural sectors, which will provide necessary reinforcements to trade.

Household consumption is expected to increase in 2023. Consumer prices rose by about 6% in 2022, but a slower increase is projected for 2023. Inflation was driven mainly by external factors resulting from the impact of the war in Ukraine and supply-chain disruptions (Figure 1.9).

Figure 1.9. Consumer price index for food and transport in Thailand, January 2020 to February 2023

Percentage changes, year-on-year

Subsidies are expected to keep energy prices low in Thailand, but energy prices remain high by historical standards, while food inflation showed slight easing from January 2023. The Thai baht depreciated against the US dollar in Q4 2022 as the interest rate differential between Thailand and the United States widened, though it has been improving recently. As a consequence of inflation, nominal household wages are expected to rise. Household debt is high in Thailand, at more than 80% of GDP as of September 2022. Rates of approval for home loans have risen dramatically since late 2021 as authorities suspended some loan-to-value caps in response to weakness in the housing sector.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand has embarked on several reforms. Thailand is focusing on four industry clusters: agriculture and food; bioenergy, biomaterials and biochemicals; medical and wellness; and tourism and the creative sector. In the coming years, the government is expected to direct more of its budget towards these sectors. As the Thai government gradually withdraws pandemic-relief spending and energy subsidies, the fiscal deficit is expected to narrow in 2023.

Significant infrastructure development is on the cards for Thailand in the coming years, as the Ministry of Transport has announced 36 planned projects to improve land, sea, and air connectivity at an estimated cost of USD 45 billion. Much of this investment will be in airports to handle increased tourist flows. Thailand has also indicated that their part of a high-speed rail connection with China via Lao PDR should be finished by 2028.

Viet Nam

Viet Nam is one of the fastest growing economies in the region. It outpaced world economic growth in 2022, recording real GDP growth of 8.0%, up from 2.6% in 2021 (Figure 1.10). Viet Nam will continue this strong growth trajectory, with anticipated 6.4% real GDP growth in 2023. The weakening demand from major markets will be a concern but this would be somewhat offset by demand from China given its recent reopening. Furthermore, a trend of foreign firms relocating their manufacturing facilities to Viet Nam – especially in electronics, machinery, and footwear – will support economic activity.

Figure 1.10. Contribution to GDP growth in Viet Nam, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data on demand- and supply-side factors are unavailable for 2022. Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Investment grew in 2022 on the back of foreign investment in the export-oriented manufacturing sector, a trend that continued from 2021, when investment was a major positive contributor to real GDP growth (Figure 1.10). Investment growth is expected to slow in 2023, however, due to an environment of higher interest rates. Household spending was affected in 2022 by higher prices, especially for food and fuel. Goods exports will be affected in 2023 by weaker external demand from major exporting markets. The services deficit is expected to narrow as tourism recovers, pushing the current account back in 2023. The capital account will strengthen on the back of net inward FDI surpassing net portfolio flows.

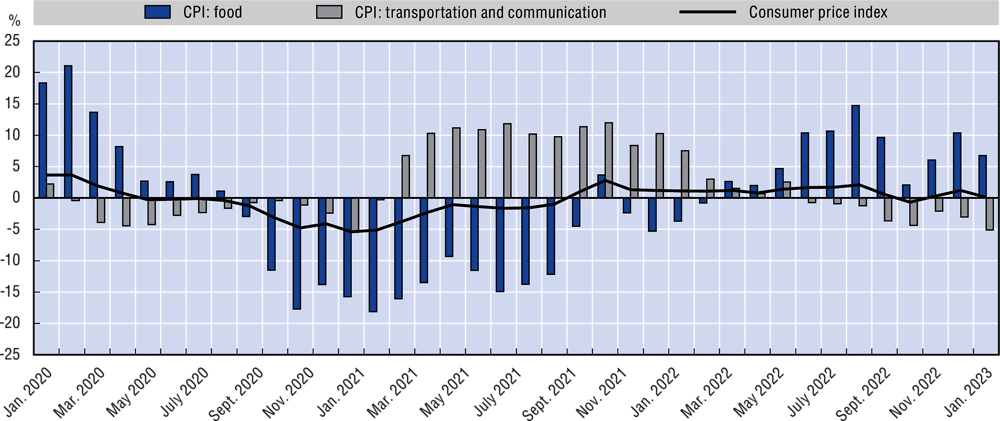

Viet Nam, like all other countries in Emerging Asia, saw a rise in consumer price inflation in 2022. The inflation rate in Viet Nam remains high, reaching 4.9% in January 2023, the highest level since 2021. This was due to inflation in housing and construction material, education and food prices. In contrast, transport prices fell by 0.16% in December.

The monetary authority increased its policy rate sharply in September and October 2022, by 100 basis points on both occasions, bringing the rate to 4.5% from a historical low of 2.5% in August 2022.

The fiscal deficit will gradually improve, mainly due to the winding down of the government’s pandemic recovery initiative. Also playing a role will be indirect tax revenue from the reintroduction of a higher VAT of 10%, after a temporary reduction to 8% in 2022. Viet Nam will also remove some tax incentives in economic zones, such as partial tax holidays for firms in specific industries.

Brunei Darussalam and Singapore

Brunei Darussalam

After experiencing seven consecutive quarters of negative growth since the third quarter of 2020, Brunei Darussalam’s GDP rebounded by 0.9% in the third quarter of 2022. The first and second quarters of 2022 recorded a year-on-year decline of 4.2% and 4.4%, respectively (Figure 1.11). The decline was due to maintenance work on oil and gas facilities and the country’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1.11. Contribution to GDP growth in Brunei Darussalam, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

In 2022, the economy contracted due to stoppages for maintenance work on ageing oil and gas facilities. The downstream petrochemicals sector and the redevelopment of the port at Muara, are expected to support overall output. The lifting of pandemic-related restrictions spurred faster growth in other sectors, especially retail and hospitality. In the food sector, agriculture and fisheries are expected to expand and further support economic activity.

GDP growth of 3.2% is anticipated in 2023. Investment in the fertiliser industry in the first quarter of 2023 will support GDP growth and exports. This comes at an opportune time for Brunei Darussalam given that global fertiliser prices are exceptionally high. The country is also benefiting from surging oil and gas prices resulting from the war in Ukraine, and this will in turn boost government revenues. The country will also benefit from rising exports of petrochemical products. In line with its historical trend as a significant oil and gas exporter, the government is expected to run a larger current account surplus in 2023. The forecast of a higher surplus reflects higher global oil and gas prices and prospects for higher petrochemical and fertiliser exports.

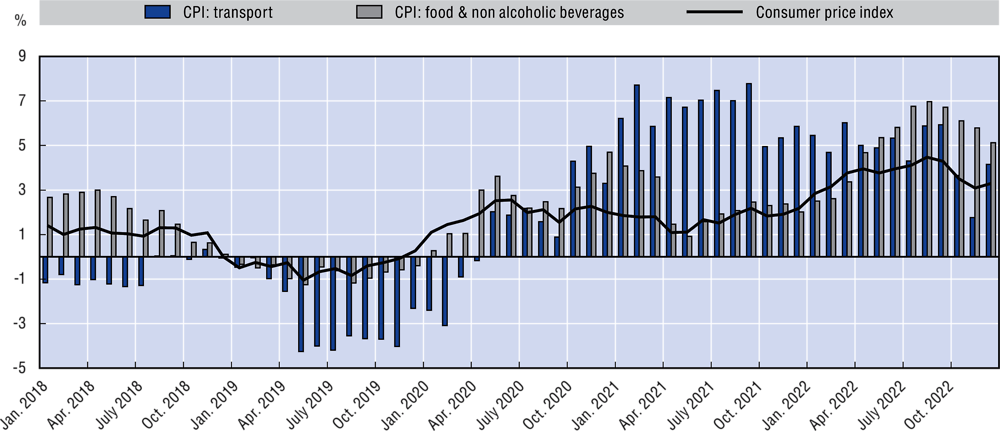

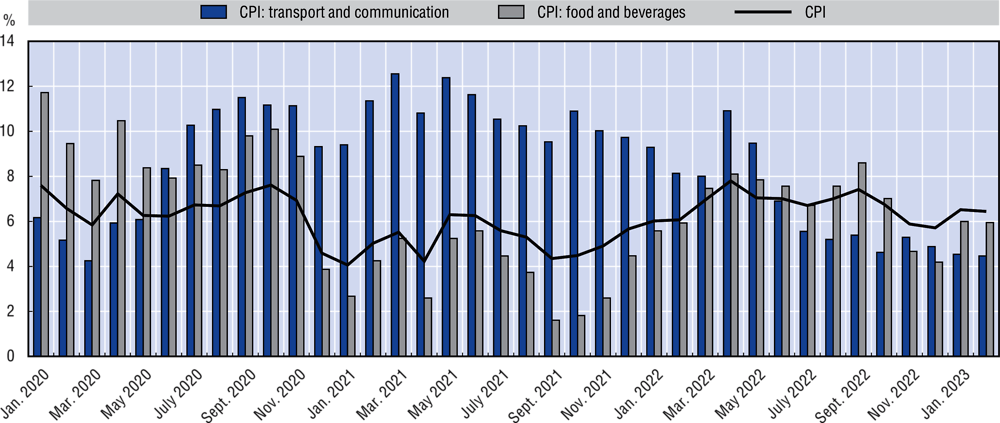

Inflationary pressures have traditionally been contained by the Brunei dollar’s peg to the Singapore dollar, along with an array of fiscal subsidies. Price caps on some essential goods have been in place for a long time (See Chapter 2). Inflation rose to 3.7% in 2022 from 1.7% in 2021, reflecting rising global food and energy prices. The main contributor was food and non-alcoholic beverage prices (Figure 1.12).

Figure 1.12. Consumer price indices for food and transport in Brunei Darussalam, January 2018 to December 2022

Percentage changes, year-on-year

As a country that depends heavily upon imported food, Brunei Darussalam seeks to develop its agriculture and fisheries sectors. Not only will such efforts reduce dependence on imported food, but if high-quality produce is emphasised, there is potential for Brunei Darussalam to become an exporter of these goods.

Singapore

Singapore’s real GDP growth moderated in 2022 and is projected to be 2.2% in 2023. Output growth over the year was mainly driven by domestic consumption and net exports, while investment also posted a positive contribution to GDP growth (Figure 1.13, Panel A). On the supply side, services provided the largest contribution to growth, driven by information and communication as well as financial services. The industry sector also posted a solid performance (Figure 1.13, Panel B).

Figure 1.13. Contribution to GDP growth in Singapore, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Domestic consumption is expected to be weak in 2023 due to higher inflation, a scheduled increase in VAT and lower capital returns, reducing the purchasing power of households. Investment is also expected to wane in 2023 owing to higher borrowing costs and dampened business sentiment.

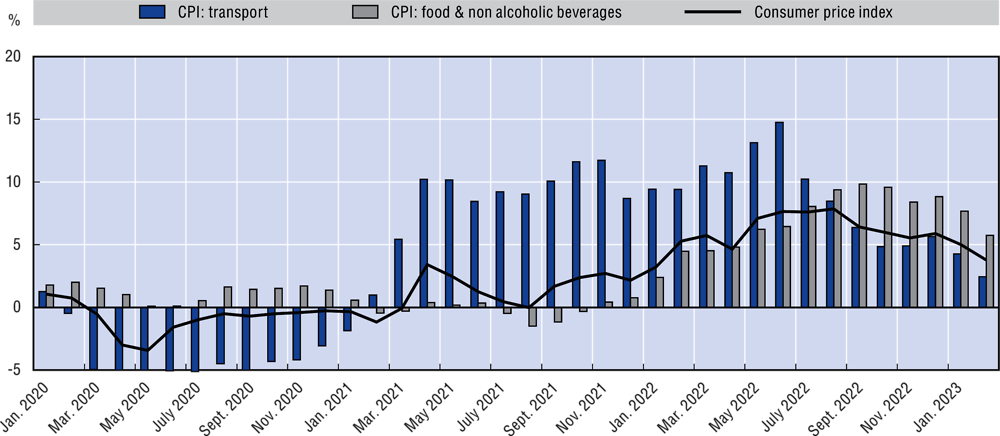

In line with global trends, consumer price inflation in Singapore was high in 2022 in comparison with historical standards, reaching 6.1%. While transport price inflation remains elevated, at 11.9% in January 2023, it has been declining since peaking at 20.2% year-on-year in August 2022. Similarly, housing price inflation eased to 5.4% in January 2023, down from a peak of 6.2% in September 2022. Food inflation remains a concern, as Singapore relies heavily on imported food. Food inflation surged to 8.2% in January 2023 (Figure 1.14).

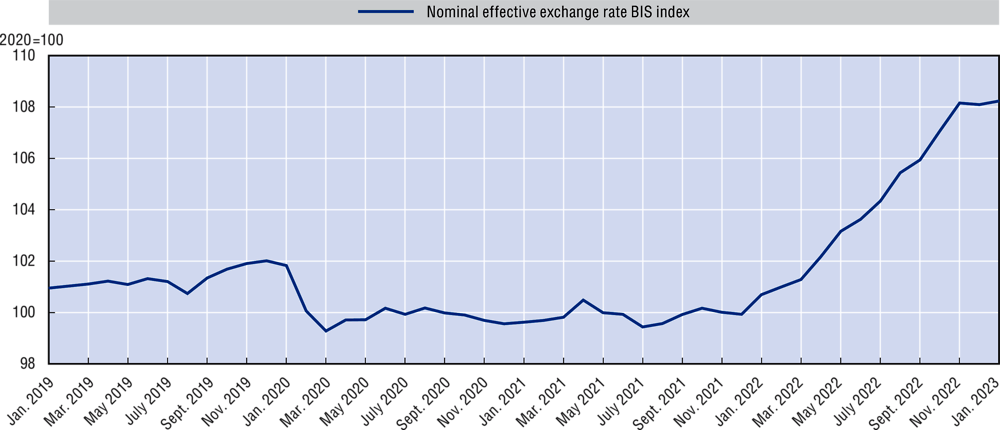

Like other regional economies, Singapore experienced depreciatory pressures on its local currency. Since Singapore conducts monetary policy by managing the exchange rate, the central bank intervened in the foreign exchange market to manage the pace of nominal depreciation of the Singapore dollar against the US dollar and keep the Singapore dollar exchange rate within the target band. (Figure 1.15). Even so, the central bank is expected to continue its monetary policy tightening.

Singapore’s current account surplus decreased in 2022. Looking ahead, Singapore is expected to maintain a large current account surplus in 2023 onwards due to its position as a global trading hub, although a decline in exports is expected due to the global economic slowdown in 2023, with a particular decline in manufactured goods such as electronics and chemicals, moderate growth is expected in the near term. There is a positive outlook for net direct investment inflows due to the optimistic views of foreign investors.

Figure 1.14. Consumer price indices for food, transport and housing in Singapore, January 2020 to January 2023

Percentage changes, year-on-year

Figure 1.15. Singapore dollar, nominal effective exchange rate, January 2019 to January 2023

Index 2020 =100

Note: An increase in the index value indicates appreciation of the Singapore dollar, while a decrease indicates depreciation. Latest data as of 27 February 2023.

Source: Data from CEIC.

The unemployment rate in Singapore is low and stood at 2.0% in December 2022, though some increase might be expected as the government withdraws pandemic-era job support schemes, coupled with the prevailing tighter economic conditions.

Singapore could position itself as an e-commerce hub for the region. Various sectoral authorities are working to boost productivity in Singapore, including through digitalisation. For instance, the Building and Construction Authority has used the longstanding Productivity Innovation Project.

Cambodia

Cambodia’s economy grew by 5.1% in 2022, up from 3.1% in 2021. Economic growth is expected to continue accelerating, reaching 5.4% in 2023. The economy is recovering from pandemic-related disruptions, with the manufacturing sector playing a key role, though net exports negatively affected real growth in 2021. On the supply side, the industry and agriculture sectors were the primary contributors to growth in 2021, while the services sector had a negative impact. The tourism sector, the main driver of Cambodia’s economic expansion prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, is expected to drive growth in 2023. China’s decision to abandon its zero-COVID policy will support the recovery of the tourism sector, leading to earlier than expected improvements in employment and income for the transport and hospitality industries as well.

High global prices of food and energy are likely to continue to impede the recovery of both private consumption and investment in Cambodia. Private consumption’s contribution to growth is anticipated to decrease in 2023, while the significance of net exports to GDP growth is expected to rise. Slowing growth in the United States, Cambodia’s largest export market, is expected to have an impact on the country’s exports and GDP growth in 2023, although the expected recovery of the tourism industry is predicted to offset some of this decline by boosting consumption and investment. The government is expected to expanding physical infrastructure and promote inward investments.

Inflation in Cambodia has been rising, reaching 5.3% in 2022. Food prices, which represent the largest share of consumer spending, will likely remain elevated due to the war in Ukraine. The riel is under depreciation pressures against the US dollar, but volatility will be milder, due to actions taken by the monetary authority. The central bank may consider transitioning to a more flexible exchange-rate system in the long term, which would also accelerate de-dollarisation.

Maintaining stable fiscal policy is recommended for the short and medium term. With the lifting of restrictive measures implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, economic recovery should help to improve the fiscal situation. Cambodia enacted a law allowing the country to issue sovereign bonds in 2020, held its first bond auction in 2022, and additional bond issuances are expected in 2023 – important developments in market-based financing.

In the medium term, the government plans to implement various international trade and capital flow liberalisation measures, such as new tax incentives for foreign investors. Service exports are projected to grow in 2023 as the tourism industry recovers. Goods exports are also expected to benefit, as Cambodia is viewed as an attractive environment for labour-intensive manufacturing. The anticipated growth slowdown in advanced economies poses a risk to Cambodia’s exports of goods.

Lao PDR

Lao PDR is projected to experience GDP growth of 3.5% in 2023 and 3.8% in 2024, accelerating from 3.1% in 2022. Growth will be driven by private consumption, which accounts for more than 60% of GDP. Exports rose by 5.5% in 2022, while import growth weakened. A railway connecting Lao PDR and China will facilitate trade by reducing costs for both imports and exports, with trade of agricultural, metal and mineral products receiving the most benefit. Exports of services are weaker, but tourism will receive a boost in 2023.

Investment is expected to increase in 2023, especially for labour-intensive manufacturing. The energy sector and infrastructure development are the main contributors to this growth. Electricity accounts for about 30% of exports and will benefit from the construction of a new hydropower plant. Lao PDR’s other main exports are copper, gold, and low-end electronics and parts. However, tighter global monetary conditions and slower growth in external demand will weigh on investment. Weaker global growth and higher borrowing costs will weigh down private investment.

Inflation has surged in Lao PDR due to rising global commodity prices linked to the war in Ukraine and sharp depreciation of the Lao kip (see Chapter 2). Consumer prices increased by 23.0% in 2022, up from an increase of 3.8% in 2021. Inflation is expected to ease to 14.8% in 2023 as energy prices decline slightly. The magnitude of inflation is a direct reflection of Lao PDR’s dependence on imported oil and its heavy reliance on foreign sources for many consumables and intermediate inputs. In response to rising energy prices, the government abolished fuel excise taxes for farmers, easing price pressure on food and related products. However, high fertiliser costs continue to elevate the production costs of agricultural goods.

Lao PDR has implemented monetary policy tightening measures since June 2022, but these efforts have had little impact due to rapid depreciation of the local currency and the highly dollarised economy. In 2022, the reserve requirement for the local currency was increased from 3% to 5%, and the base interest rate rose from 3.0% in April 2022 to 6.5% in October 2022, where it remained until February 2023 when it was raised to 7.5%. As of February 2023, the kip has continued to depreciate rapidly.

Myanmar

The ongoing political uncertainty in Myanmar has adversely affected the country’s growth outlook. Real GDP contracted sharply after February 2021. A decline in private consumption was the main reason for this development. Industrial production and the services sector suffered most on the supply side, and agriculture also posted negative contributions to growth. Nonetheless, economic growth saw a moderate recovery in 2022, and it is projected to 2.0% in 2023. The clothing manufacturing sector is expected to drive some export growth in 2023.

Fixed investment is projected to increase by 2.1% in Myanmar as construction and manufacturing return to operation. In the current environment of uncertainty, foreign investment inflows will be significantly smaller than they were prior to the coup. Foreign investors are expected to come mainly from the region and to invest predominantly in geopolitically strategic projects such as energy and mineral sectors, while moving investment away from the manufacturing sector.

Although exports are limited by global economic conditions, they will be the main driver of growth in fiscal year 2022-23. Services trade will remain low, however. Little improvement is expected in consumer sentiment as unemployment is rising.

The main drivers of inflation are high global energy and commodity prices, US monetary policy tightening and the sharp depreciation of the Myanmar kyat. Despite its sales of foreign reserves, the central bank has been unable to prevent depreciation, and the stock of foreign reserves has decreased significantly. Policy rates have remained unchanged since May 2020, while banks have been required to convert foreign currencies to the kyat at approved exchange rates.

China and India

China

Real GDP growth in China for the full year was 3.0% in 2022, below the 8.1% growth of 2021 and target growth for 2022. In the first quarter of 2022, real GDP grew at a strong rate of 4.8% year-on-year. However, the growth contracted sharply to 0.4% in the second quarter, revealing the impact of lockdowns in April and May 2022. The gradual lifting of lockdowns at the end of May resulted in a recovery in the third quarter, with growth at 3.9%. But growth then slowed to 2.9%, with headwinds from the pandemic – a broadening of lockdowns in October and November was followed by a sharp rise in COVID-19 cases and a downturn in real estate, as well as a slowdown in external demand. After ending zero-COVID policy, China is expected to experience a recovery in 2023, with economic growth projected to rise to 5.3%, driven by a rebound in private consumption and investment. At the same time, slowing global economic growth will be a negative factor.

Investment proved to be the main driver of China’s growth in 2022, supported by public-sector infrastructure spending (Figure 1.16). Private consumption continued to contribute positively to growth in 2022, although far less so than in 2021. Net exports were also an engine of growth. On the supply side, the manufacturing and services sectors, in particular in-person services, struggled in 2022 due to zero-COVID policy.

Figure 1.16. Contribution to GDP growth in China, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

The decision by China to abandon its zero-COVID policy in December 2022 and the reopening of its borders in January 2023 have led lead to a wave of COVID-19 cases in early 2023 that has suppressed economic activity. Nevertheless, overall growth in 2023 is expected to rebound sharply afterwards. China’s rapid economic growth could lead to higher demand for goods, services and commodities, especially considering the pent-up demand accumulated during lockdowns. While this growth could provide a significant boost to global economic growth in 2023 and beyond, there will be potential impacts on energy and commodity markets, inflation and interest rates. For regional economies, the overall effect of China’s border reopening is positive, and will boost tourism and merchandise trade.

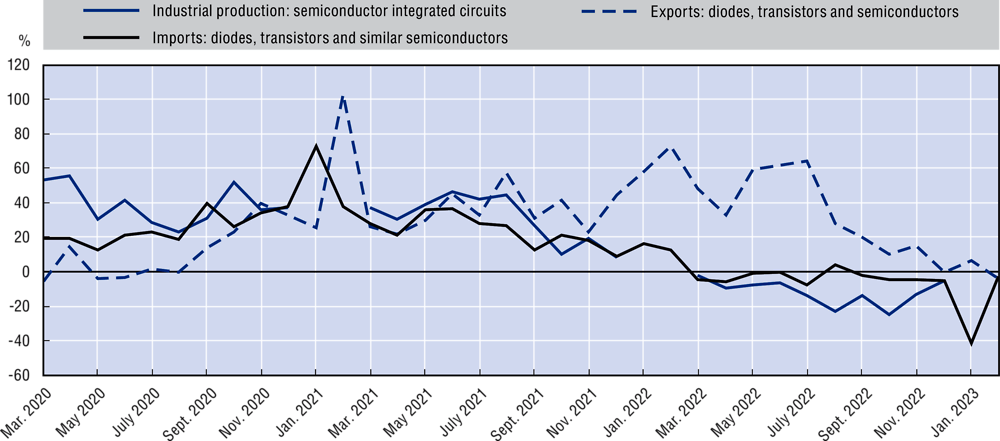

Due to China’s zero-COVID policy in place at the time, the country’s exports and imports declined in the fourth quarter of 2022, especially in the electronics sector.

China’s semiconductor industry has been particularly hard hit by supply-side disruptions related to lockdowns (Figure 1.17). Robust growth, which had continued during the outbreak of the pandemic, turned into contraction in 2022.

Figure 1.17. China’s industrial production and trade in semiconductors and related parts, January 2018 to February 2023

Percentage changes, year-on-year

Inflation is mostly driven by rising food prices, especially pork and fresh foods, though pork price inflation may have peaked in July 2022 (Figure 1.18). Sufficient grain stocks will keep prices low even as global grain prices soar.

Low inflationary pressures allowed China’s monetary policy to remain accommodative throughout 2022 and it will remain so in 2023. The policy rate is projected to remain at 2.75% throughout 2023.

Figure 1.18. Consumer price indices for food and non-alcoholic beverages and transport, January 2020 to February 2023

Percentage changes, year-on-year

India

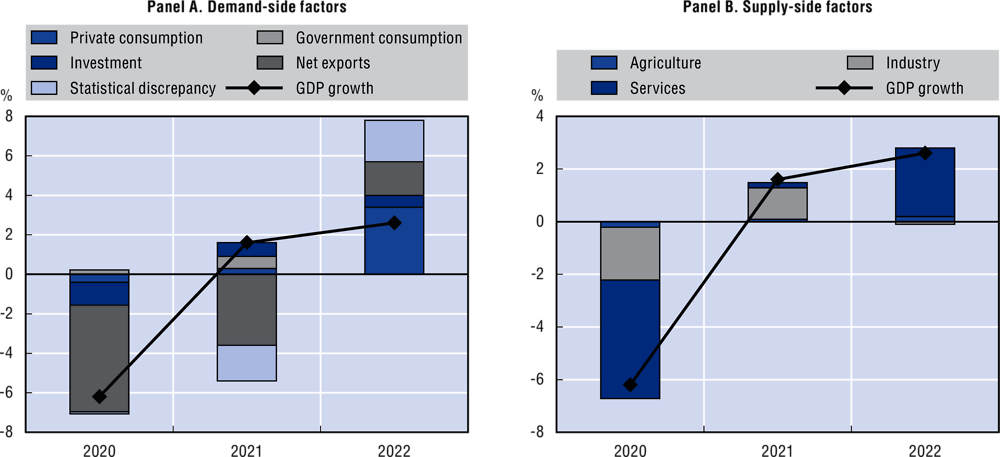

India’s real GDP growth during 2022 is 6.9%, down from 8.7% in 2021. Major contributors to growth were pent-up demand for consumer goods and government investment, while one of the factors behind the expectation of weaker economic performance in 2023 is high borrowing costs, which limit growth.

Output rebounded strongly in the beginning of 2022, with a 13.5% growth rate in annual terms. This figure is partly due to the very low base against which it was measured. In the second quarter, India’s real GDP growth was 6.3% in annual terms, followed by 4.4% in the third quarter. On the demand side, net exports, investment and private consumption made positive contributions to growth (Figure 1.19, Panel A). On the supply side, services made the largest contribution to output growth (Figure 1.19, Panel B), with a significant contribution coming from the industrial sector as well.

Labour and logistics reforms will further improve India’s competitiveness in manufacturing. The government’s focus in the coming years will be on developing infrastructure, including building and upgrading ports, roads and railway networks. While major roads and freight corridors are scheduled to be completed in 2023 and 2024, there may be challenges and delays due to land-acquisition reforms that the government has yet to undertake.

India faces the challenge of ensuring a steady supply of human capital to support the expansion of manufacturing. In addition, the benefit of FDI can vary greatly by state, as many regulations and tax laws enacted at the state level can influence the generation of linkages and spillovers. The government has also made strides in the electronics sector as part of its production-linked incentive scheme, with electronics exports reaching USD 16.7 billion from April through December 2022, a 52% year-on-year increase from exports of USD 11 billion in the same period last year.

Figure 1.19. Contribution to GDP growth in India, 2020-22

Percentage

Note: Data relate to fiscal years ending in March. The sum of contributions may not necessarily be equal to GDP growth.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

However, export growth could be dragged down by slower external demand in 2023, placing pressure on the trade deficit. At the same time, India is expected to maintain services and secondary income accounts in surplus thanks to its information technology (IT) services exports and remittances.

The agricultural sector plays a crucial role in India’s economy, providing livelihoods for almost 60% of the population and contributing 20% of GDP in 2022. Recent years have seen an increase in agricultural yields, and the continuation of minimum support prices for various products following the repeal of the Farm Bills has further boosted the sector. In 2022, almost all subsectors of agriculture witnessed value growth, with total food-grain production increasing by 1.6% in volume year-on-year. India also achieved all-time highs (by value) for rice, wheat and other cereals as well as sugar.

Tax reforms, including lower business taxes and incentivised tax reporting and compliance, are expected to enhance business confidence and attract foreign investment. In 2019, the government lowered corporate tax rate from 30% to 22% for eligible businesses. Adoption of the goods and services tax at the national level will also be important. Labour market reforms, another key element of economic performance, were initiated in 2020 with plans to improve labour market flexibility, enhance skills, and focus on worker health and well-being.

Consumer price inflation has gradually decelerated from October 2022 as food prices moderate with a fresh harvest (Figure 1.20). Given the prominence of oil in India’s consumer price index, moderation of oil prices in 2023 will assist in cooling down inflation. However, CPI remains high and a pass-through of higher input prices to consumers will continue in 2023, preventing inflation from decelerating significantly.

Figure 1.20. Consumer price indices for food and transport, January 2020 to February 2023

Percentage changes, year-on-year

To combat inflation and stabilise the Indian rupee, the central bank implemented several policy-rate increases in 2022. In May 2022, the policy rate was raised to 4.4%, followed by another increase of 50 basis points in June 2022 to bring the policy rate to 4.9%. In August and September 2022, the policy rate was further raised to 5.4% and 5.9%, respectively. In December the policy rate reached 6.25%, which remained in effect through January 2023, but was further increased to 6.5% in February 2023.

While large banks have seen declines in non-performing loan (NPL) ratios in recent years (even during the first phase of pandemic), NPL ratios at small finance banks ballooned from 1.9% in 2020 to 5.4% in 2021.

The fiscal balance will improve in 2023 due to lower spending on food and fertiliser subsidies. The pace of public capital spending will also slow in 2023. Tax reforms and increasing tax compliance will help the government to achieve further fiscal consolidation.

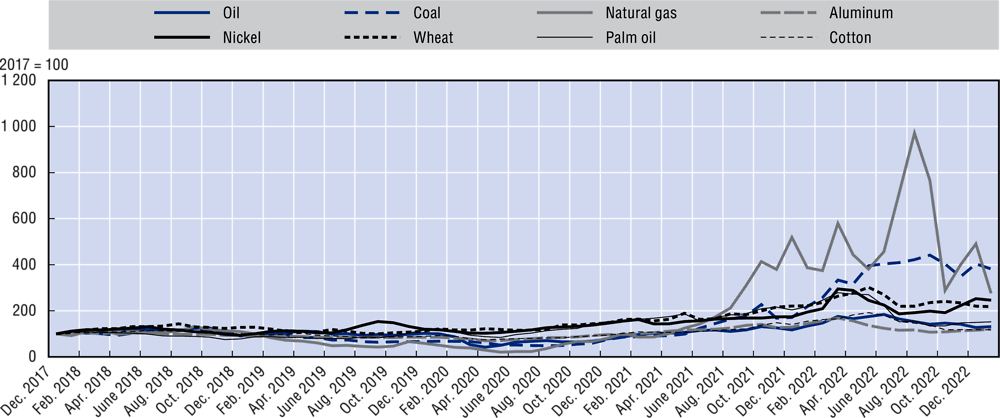

Financial markets exhibit resilience despite volatility and risks

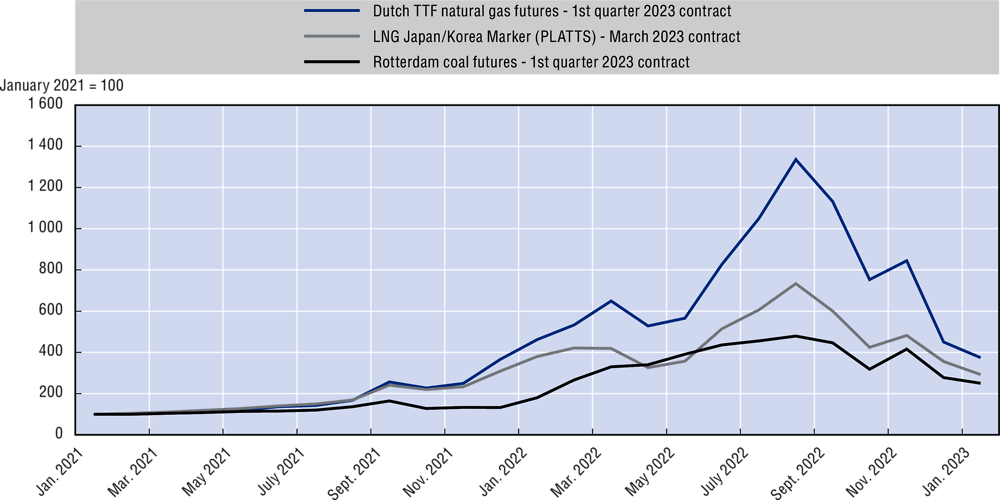

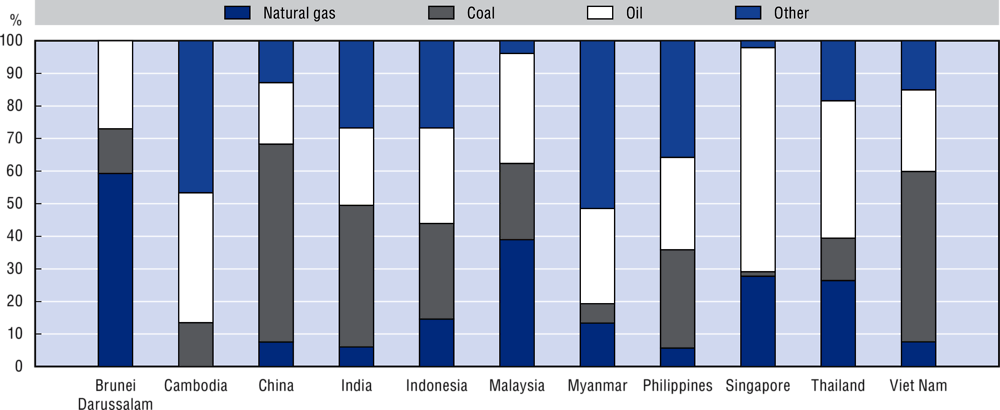

Inflationary pressures have not reached the current level since the oil market disruptions of the 1970s. Since the war in Ukraine in February 2022, global prices of crude oil and natural gas have risen to their highest levels in more than a decade, and the price of coal hit an all-time high in September 2022. Natural gas prices peaked in August 2022, increasing by 56.4% since the escalation of the war in Ukraine (Figure 1.21).

Nevertheless, consumer price inflation in Emerging Asia remains subdued relative to the rest of the world, primarily due to the broad implementation of policy measures such as price controls and tax cuts, but also because of better-contained currency depreciation. In most Emerging Asian countries, the annual growth of both overall consumer prices and core inflation is lower than OECD averages, but consumer price inflation remains persistent (for more details, please see Chapter 2).

Figure 1.21. Evolution of selected commodity prices, January 2018 to January 2023

2017 = 100

Note: Latest data as of 17 March 2023. Indices reflect market prices. “Oil” refers to benchmark Brent crude prices. “Natural gas” refers to prices for natural gas traded in the Netherlands. “Coal” refers to prices on Australian export markets.

Source: IMF (n.d. b), Primary Commodity Price System database, https://data.imf.org/?sk=471DDDF8-D8A7-499A-81BA-5B332C01F8B9&sId=1547558078595 (accessed multiple times between November 2022 and February 2023).

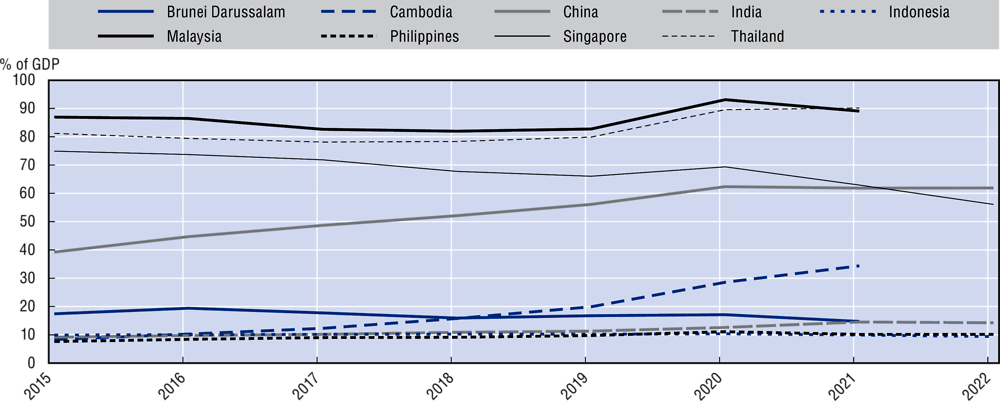

The implications of rising interest rates for households and businesses in the more advanced economies of Emerging Asia are particularly important. Rising inflation and interest rates will put additional pressure on leveraged households and businesses. Household debt is particularly high in Malaysia and Thailand, which experienced tighter monetary conditions in 2022 (Figure 1.22).

Figure 1.22. Household debt, 2015-22

Percentage of GDP

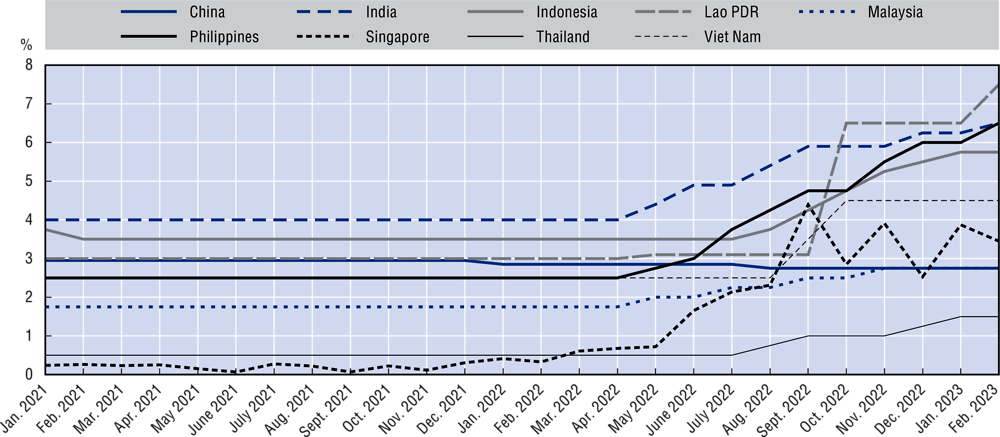

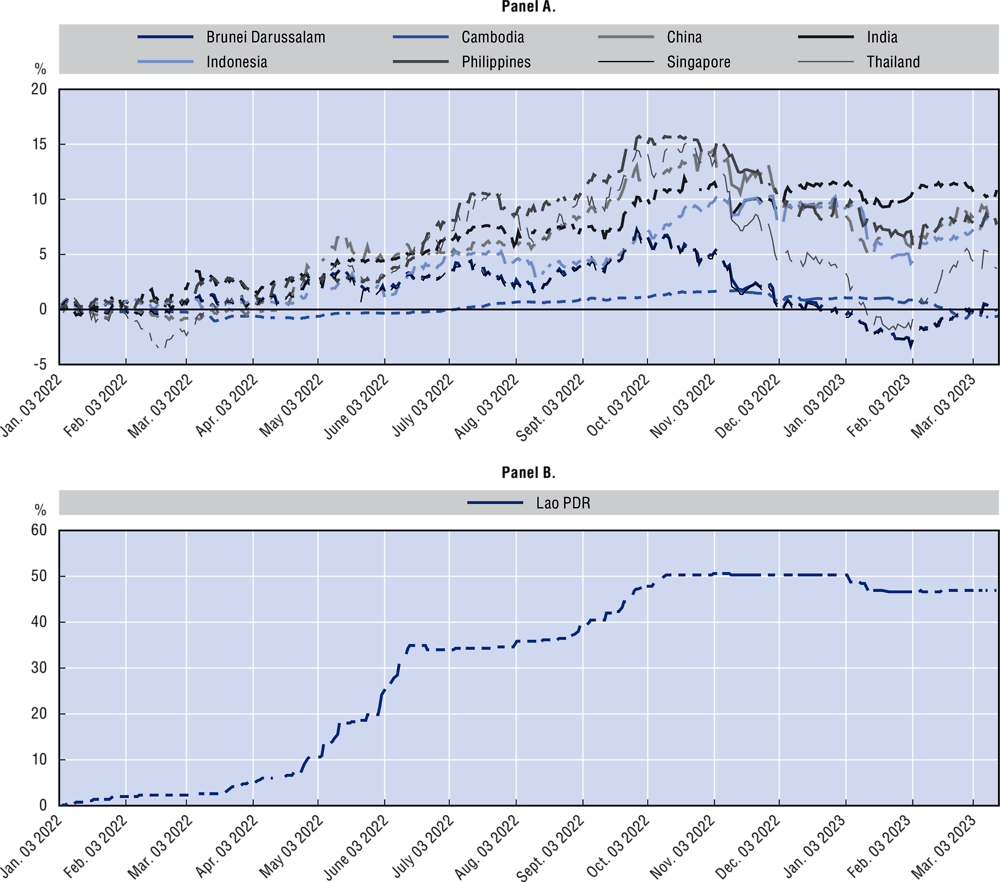

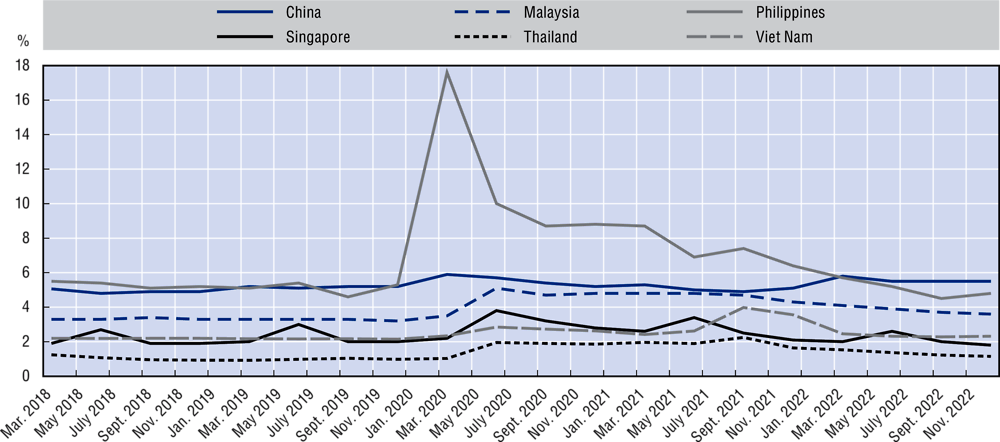

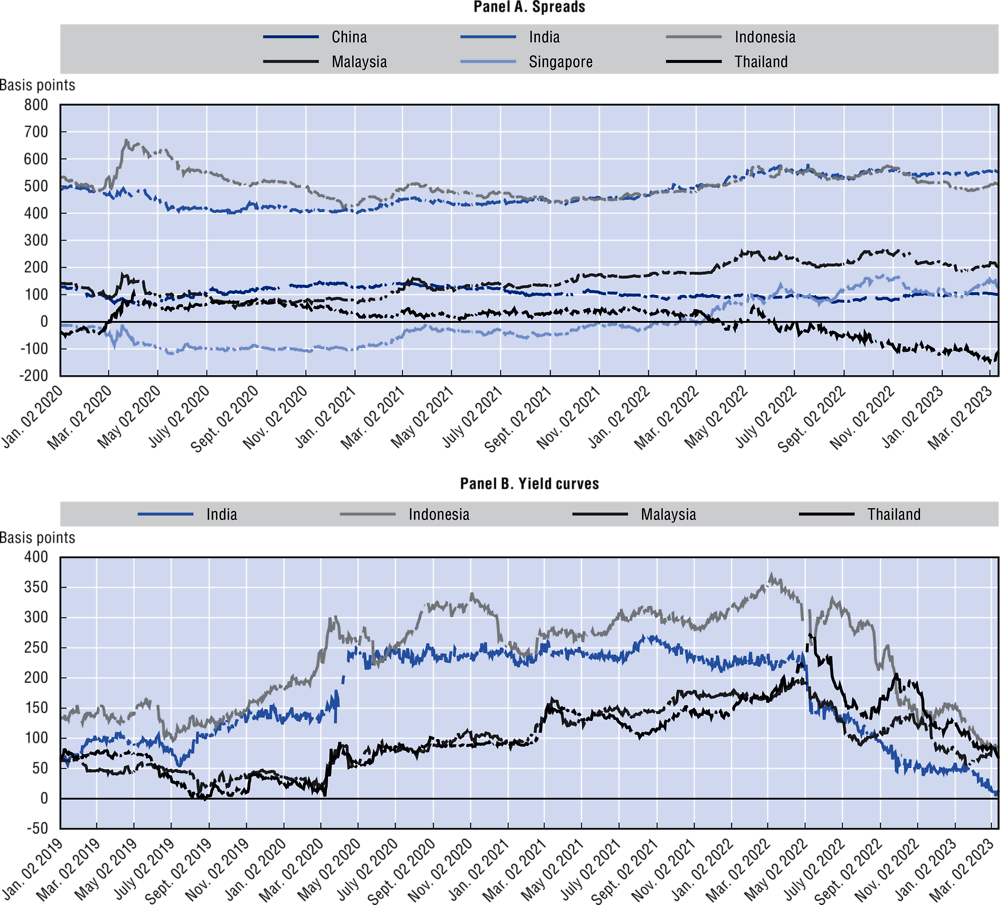

Against this background, Emerging Asian economies experienced deterioration of financial conditions and rising bond yields in the second half of 2022, mainly driven by aggressive monetary policy tightening in major advanced economies. Most of the regional central banks pursued tighter monetary policy (Figure 1.23) to combat domestic inflation, relieve depreciation pressures on local currencies (Figure 1.24), and close widening interest rate differentials with the United States.

Figure 1.23. Policy rates, January 2021-February 2023

Percentage per annum

Most of the region’s central banks hiked interest rates to address financial and price stability concerns. Government bond yields rose across Emerging Asia during the second half of 2022, owing to higher bond yields in advanced economies and continued monetary tightening in all major economies (ADB, 2022). The US two-year government bond yield rose by 355 basis points from January 2022 to February 2023 following policy rate tightening by the Fed.

The spreads between local bonds and 10-year US Treasuries rose in 2022, reflecting tighter monetary policy in the United States. An exception was Thailand, with a falling yield on its 10-year government bond (Figure 1.25, Panel A). The yield curve narrowed in many regional economies (Figure 1.25, Panel B), due to a combination of rising short-term and long-term yields.

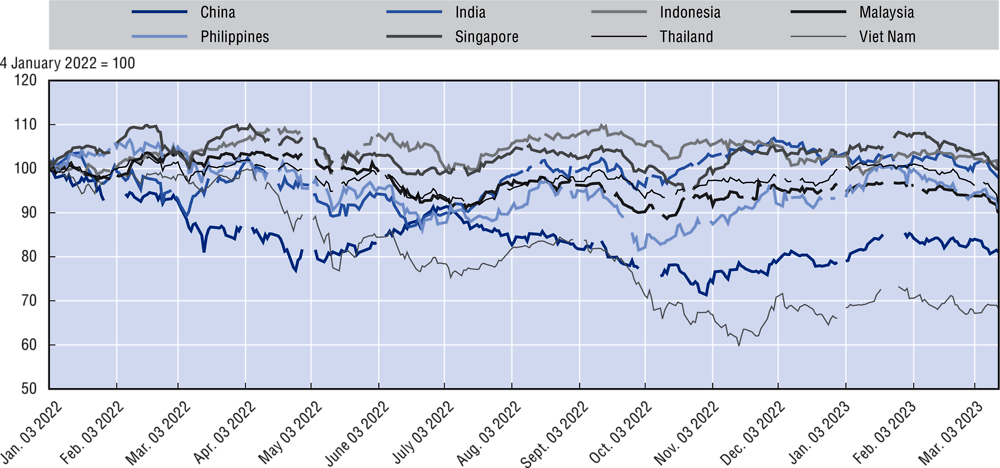

Equity markets in Emerging Asia performed better overall in 2022 than most other equity markets around the world (Figure 1.26). The performance of individual equity markets differed notably, however. India, Indonesia and Thailand emerged as better performers in the region (Figure 1.26). China’s underperformance was due to mobility restrictions under its zero-COVID policy, as well as the property crisis. At the beginning of 2023, there were some signs of an upswing in Asian equity markets.

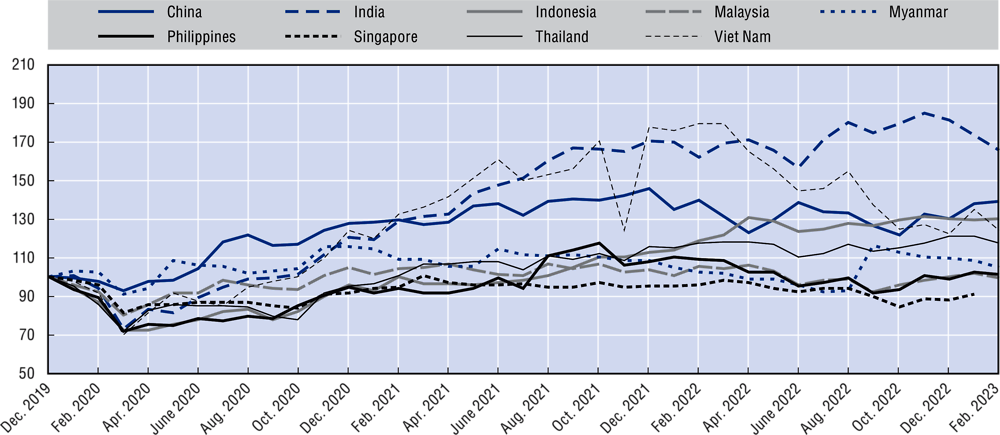

Figure 1.24. The changes in major Asian currencies against USD, January 2022-March 2023

Percentage

After a sharp decline in the first quarter of 2020 following the onset of the pandemic, stock market capitalisation remained below pre-pandemic levels throughout 2020 and 2021 and hovered above pre-pandemic levels throughout 2022. The largest increase in stock market capitalisation was recorded in India, where it rose by more than 80% from December 2019 to December 2022. Other notable performers over the same period were China and Indonesia, with increases of around 30%, Viet Nam (22.5%) and Thailand (21.2%). Energy, technology, manufacturing and financial stocks performed better over the past year. Market capitalisation is above pre-pandemic levels in Q1 2023 for most stock markets in Emerging Asia (Figure 1.27).

Figure 1.25. Spreads to 10-year US Treasuries and yield curve of selected ASEAN economies, January 2020 to March 2023

Basis points

Note: Latest data as of 17 March 2023. The yield curve is computed as the difference between yields on 10-year government bonds and yields on one-year government bonds.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CEIC and national sources.

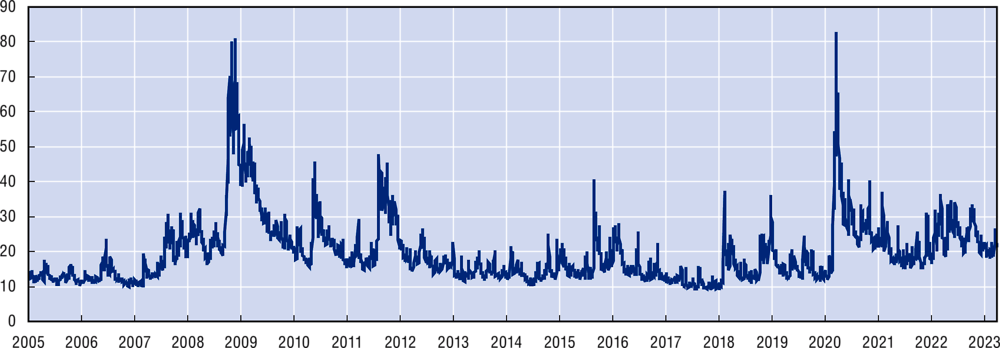

During 2022, financial markets experienced a lot of turbulence, but the level of risk was relatively subdued, reflected by the CBOE (Chicago Board Options Exchange) Volatility Index, also known as the VIX (Figure 1.28). At the beginning of 2022, the VIX started to rise steadily from mid-January, reaching its peak at 36.5 in March 2022 due to concerns over inflation, rising interest rates, and geopolitical tensions. From mid-March 2022, the VIX became stable but remained higher than at the beginning of the year, reaching 22.26 on 22 March 2023. Overall, the movement of the VIX indicates that investors were cautious but not overly concerned about market risks.

Figure 1.26. Major stock market indices of selected Emerging Asian economies, January 2022-March 2023

4 January 2022 = 100

Note: The following stock market indices are captured: Cambodia Securities Exchange Composite Index, Shanghai Shenzhen CSI 300 Index (China), BSE Sensex Index (India), Jakarta Stock Exchange Composite Index (Indonesia), Lao Securities Exchange Composite Index, FTSE Bursa Malaysia KLCI Index, PSEi Index (Philippines), Straits Times Index (Singapore), SET Index (Thailand) and Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange Index ( Viet Nam). Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CEIC.

Figure 1.27. Market capitalisation of major exchanges in selected Emerging Asian economies, January 2020 to February 2023

December 2019 = 100

Note: Market capitalisation of the following stock exchanges is depicted: Shanghai Stock Exchange (China), Bombay Stock Exchange (India), Indonesia Stock Exchange, Bursa Malaysia, Yangon Stock Exchange (Myanmar), Philippine Stock Exchange, Singapore Exchange, the Stock Exchange of Thailand, and the Ho Chi Minh City Stock Exchange ( Viet Nam). Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Figure 1.28. VIX, January 2005 to March 2023

Notes: Latest data as of 20 March 2023. The index is calculated using the prices of options on the S&P 500 index, and it reflects the market’s expectation of volatility over the next 30 days. VIX values can range from 0 to above 100, although the index typically stays within the range of 10 to 30. A value of 20 is generally considered to represent the long-term average level of the VIX. When the VIX is below 20, it is generally interpreted as a signal that the market is relatively calm, and investors are not anticipating large swings in the stock market. Conversely, when the VIX is above 20, it is generally interpreted as a signal that the market is more volatile, and investors are anticipating larger swings in the stock market. The VIX is referred to often as the «fear index,» as it tends to rise when investors are worried about market uncertainty and decline when investors are more confident about the outlook for stocks.

Source: Cboe Global Indices (n.d.), https://www.cboe.com/us/indices/dashboard/vix/ (accessed multiple times between November 2022 and March 2023).

Financial markets still need to be monitored carefully. The collapse of California’s Silicon Valley Bank on 10 March 2023 led equity markets across Asia to fall early in the next week, but they have rebounded somewhat since. However, the high-inflation environment could cause some instability in the banking system and fallout from the SVB collapse has already reached other US banks as Silvergate Bank in California and Signature Bank in New York each suffered a similar fate to SVB in the following days.

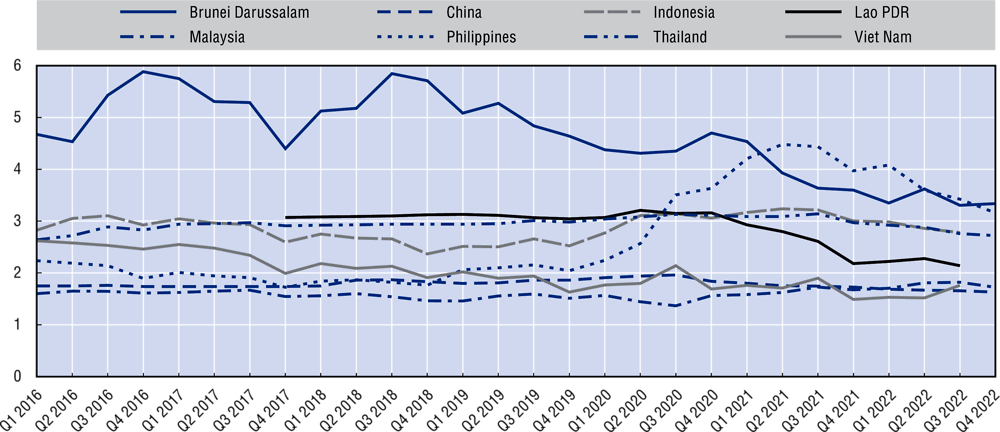

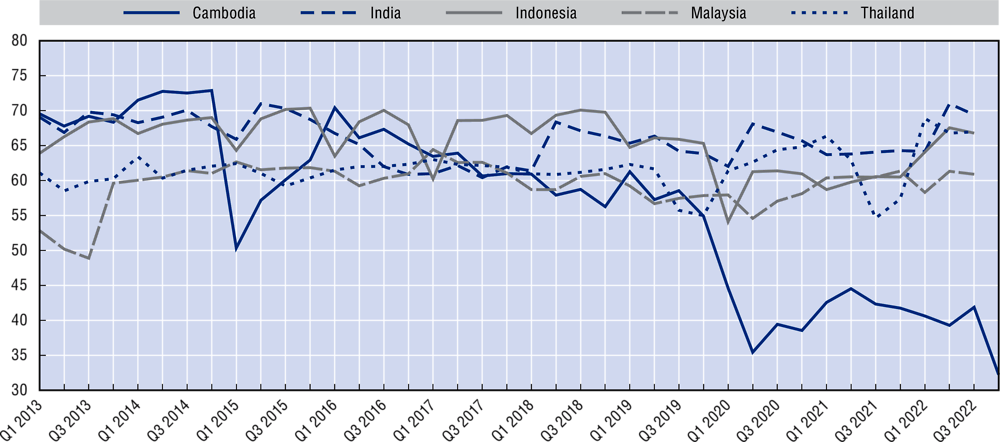

Banking sector needs careful monitoring despite showing resilience

Banking sector in Emerging Asia will also need to be carefully observed in 2023, even though Emerging Asian banks tend to hold higher loss buffers than banks in advanced Asian economies. While central banks worldwide are raising interest rates to fight inflation, the ratios of interest margin to gross income and non-performing loans (NPL) to total loans have remained relatively stable (Figure 1.29 and Figure 1.30). Overall, banking sector stability remains relatively robust in most Emerging Asian economies. This is confirmed by very high capital adequacy requirements, especially against the backdrop of what appears to be a challenging economic and financial environment. Capital adequacy remained stable at very high levels in most Emerging Asian economies for which data are available. Levels mostly remained above 15%, well above the internationally recommended 8% and national requirements. In 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, capital adequacy ratios weakened somewhat but remained higher than the recommended 8%. They subsequently recovered, reaching the highest levels of the past decade. In many countries, the capital adequacy ratios of banks are at the highest level observed since 2012. At the same time, other prudential regulations have improved in the region (OECD, 2021).

Figure 1.29. Interest margin to gross income, Q1 2013-Q4 2022

Note: Data as of 17 March 2023. The interest margin to gross income refers to the banking institutions classified as deposit takers.

Figure 1.30. Non-performing loans to total gross loans ratio, Q1 2016-Q4 2022

However, a high-inflation, high-interest environment can be challenging for banks, in terms of stability. The global banking sector experienced significant turmoil in March 2023. Two US banks, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, failed - these events were the second and third largest bank failures in US history. The United States Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) then established bridge banks and promised to make depositors whole, even if their deposits exceeded the FDIC coverage limit of USD 250 000. Silicon Valley Bank served many start-ups worldwide, and some accounts were unable to access their funds for a short time. Stock markets fell worldwide in response to the collapses, though they have been recovering. Credit Suisse became distressed on 15 March and the bank was sold to UBS on 19 March in a transaction mediated by the Swiss government and Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA).

While the risk of contagion occurring immediately is small, policy makers in the region must monitor banking conditions diligently. Monetary authorities are facing the challenge of balancing between control of inflationary pressures and maintaining financial stability.

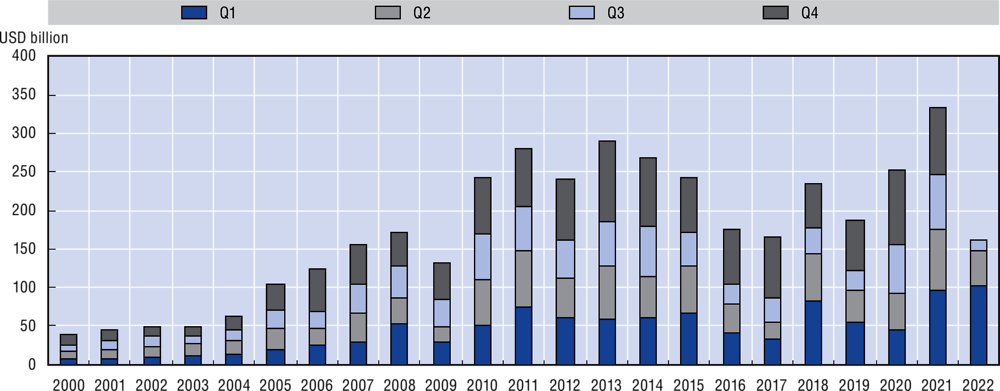

FDI declined in 2022 but there are signs of recovery in 2023

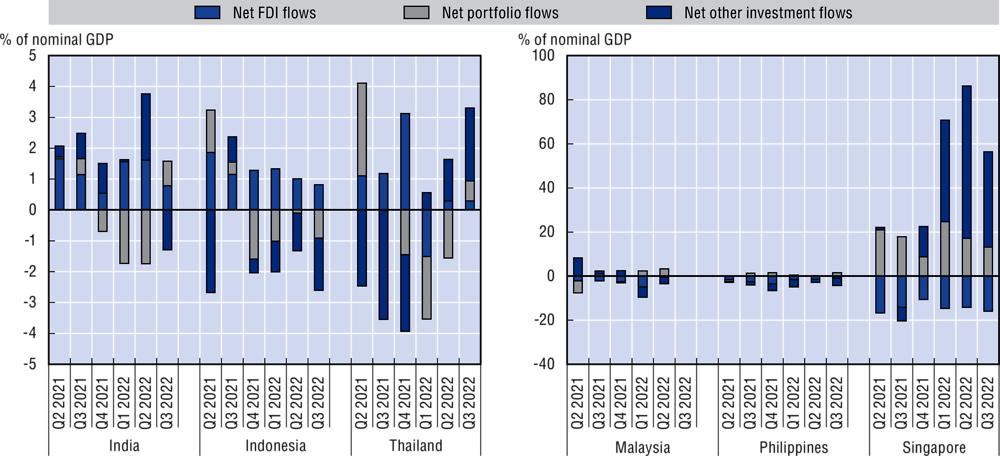

Tighter global credit conditions have affected Emerging Asian economies. Data indicate that net other investment and portfolio flows were more affected than FDI from the beginning of 2022, when the major economies started to hike their interest rates. This is particularly evident in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and India, where net other investment flows turned negative, especially during the first two quarters of 2022. But in most cases there were signs of stabilisation by the third quarter of 2022, pointing to the temporary nature of these capital outflows (Figure 1.31). In contrast, Singapore experienced net FDI outflows that continued even into the third quarter of 2022.

Figure 1.31. Direct investment, portfolio investment and other investment net flows in selected Emerging Asian economies, Q2 2021 to Q3 2022

Percentage of GDP

Note: Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Emerging Asian economies have been an attractive destination for foreign direct investment. An increase in both inward and outward FDI signals the region’s resilience as it continues to attract investment even during economically difficult times with heightened global and regional pressures, rising inflation, interest rate hikes and the economic implications of the war in Ukraine. Investors are attracted to Southeast Asian countries by the region’s competitive wages, improvements in business regulations and infrastructure, and increasing domestic demand due to population expansion and improving economic conditions. In 2022, China experienced its sharpest decline in foreign direct investment in relative terms, from USD 101.9 billion in the first quarter to USD 45.9 billion in the second quarter, a drop of 55% (Figure 1.32). A further decline was registered in the third quarter. The steep decline was due mainly to China’s zero-COVID policy, which fed into investors’ fear and uncertainty. Despite this large decline, the sheer size of the Chinese economy and the recent reopening of borders will continue to attract foreign investors.

Figure 1.32. Inward FDI flows into China, Q1 2003 to Q4 2023

USD billion

Greenfield foreign investment inflows into the Southeast Asia fell from USD 48 billion to USD 29 billion in the first three quarters of 2022, a decline of 39% year-on-year. The largest declines were in Indonesia and Malaysia, but were also significant in Viet Nam and Thailand. The highest growth rates in relative terms were registered in the Philippines and Cambodia, where investment rose by 53% and 747%, respectively. In absolute terms, Singapore continues to be the region’s largest recipient of foreign investment, although investment grew by only 6% year-on-year in 2022 (ESCAP, 2022). Greenfield investment outflows increased marginally in Southeast Asia in 2022, from USD 17 billion to USD 18 billion, a 4% increase over 2021 levels. However, the gross figure masks large diversity in the outflow movements. The largest declines in FDI outflows were recorded in Malaysia (79%) and Thailand (63%), Singapore had the region’s largest fall in outflows in absolute terms, from USD 14.5 billion to USD 12.3 billion, a decline of 15%. The declines in outflow from Singapore, Thailand, and Malaysia were offset by large outbound investment recorded by Viet Nam and Indonesia. Investment outflows from Viet Nam increased by 1 265% (USD 4.3 billion) and from Indonesia by 225% (USD 9.07 billion). The particularly large decline in foreign investment in China was offset by major investments in India. Over 2022, greenfield inward FDI in India grew by 382%, from USD 12 billion to USD 60 billion. This exceptionally large growth was due to the number of investment projects, including investments of USD 19.5 billion to build a semiconductor plant and USD 5 billion to set up a new hydrogen ecosystem.

The general trend over the last decade in the region has been a decline of the primary sector share in inward FDI, a stable share in the manufacturing sector and a growing share in the services sector. This trend was reflected in the manufacturing and services sector in 2022, but investment in the primary sector grew.

The investment trends described above reflect longer-term trends and are not expected to be interrupted by the global economy weakening in 2023. FDI in Emerging Asia is expected to continue rising, especially in Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and Viet Nam. China’s abandonment of zero-COVID policy is a positive element in the region. Multinational enterprises will take advantage of investment incentives in these countries and demand for electric vehicle components and other electronics crucial to developing the digital economy (Box 1.1). However, competition for FDI among regional economies is expected to increase due to the tighter economic conditions and while projections indicate that FDI inflows will increase in 2023, this is expected to take place at a slower pace than in 2022.

Box 1.1. Electric vehicles and electronics drive FDI in Southeast Asia

Measures implemented by countries in Southeast Asia to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) include tax incentives, investment promotion policies and infrastructure development programmes (Dugar and Jun, 2022). For example, Viet Nam has implemented a range of incentives to attract FDI, including corporate income tax exemptions, land rent reductions and import duty exemptions for certain projects. Indonesia has simplified regulations and procedures, provided tax incentives and improved infrastructure. Other factors that will help to sustain a robust inflow of investment include regional integration, adjustment or strengthening of supply-chain capacity and regional corporate expansion strategies.

The growth of FDI in Southeast Asia is expected to be fuelled by international interest in electric vehicles, electronics and the digital economy (ADB, 2023). These industries are likely to experience significant advancement, including the emergence of new investor categories, new value-chain segments, capacity expansion and an increase in regional production networks. To position the region as a significant player in the global electric vehicle market, several ASEAN countries are offering incentives. The region has the potential to become a major manufacturing hub by attracting foreign investment in the electric vehicle value chain, which includes nickel mining and smelting, battery production, vehicle manufacturing and related research and development.

A robust local market is fundamental for nurturing a new industry and ASEAN economies have experienced rapid growth over the past decade. Several international firms have relocated from China to ASEAN countries, leading to a rise in purchasing power and an increase in FDI. On the supply side, ASEAN has all the necessary components for intelligent electric vehicle production, including software and AI expertise, batteries, electric vehicle control units (ECUs) and manufacturing capabilities. Singapore has become a hub for software and AI talent thanks to its superior universities and research and development systems. Indonesia and the Philippines, with their vast reserves of nickel and cobalt, are strong competitors in the battery industry (Raharyo, Mertawan and Baskoro, 2022). Malaysia is a leading semiconductor producer in the global supply chain, particularly in the automotive ECU sector.

The region’s electronics industry has also seen a significant increase in FDI in the wake of global semiconductor shortages and supply-chain disruptions that developed during the pandemic. Multinational enterprises are expanding their operations in ASEAN countries, particularly Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. In Viet Nam, for example, Samsung and Intel have made significant investments in manufacturing plants. Samsung invested USD 17.3 billion over a little more than a decade, while Intel invested USD 1.5 billion. From 2010 to 2020, Viet Nam’s exports of electronics, computers and components grew at an average annual rate of 28.6%, with double-digit growth even before the US-China trade tensions and COVID-19 lockdowns. As an exporter of electronics, Viet Nam has moved up to the tenth position globally and represents 1.8% of the global value of electronics exports (Leung, 2022). Across ASEAN, investments in electronics and electrical equipment quadrupled in 2021 to USD 32.9 billion, making up 52% of all greenfield investments compared to just 12% in 2020 (ASEAN, 2022).

Exports supported growth in 2022, but show some signs of weakening

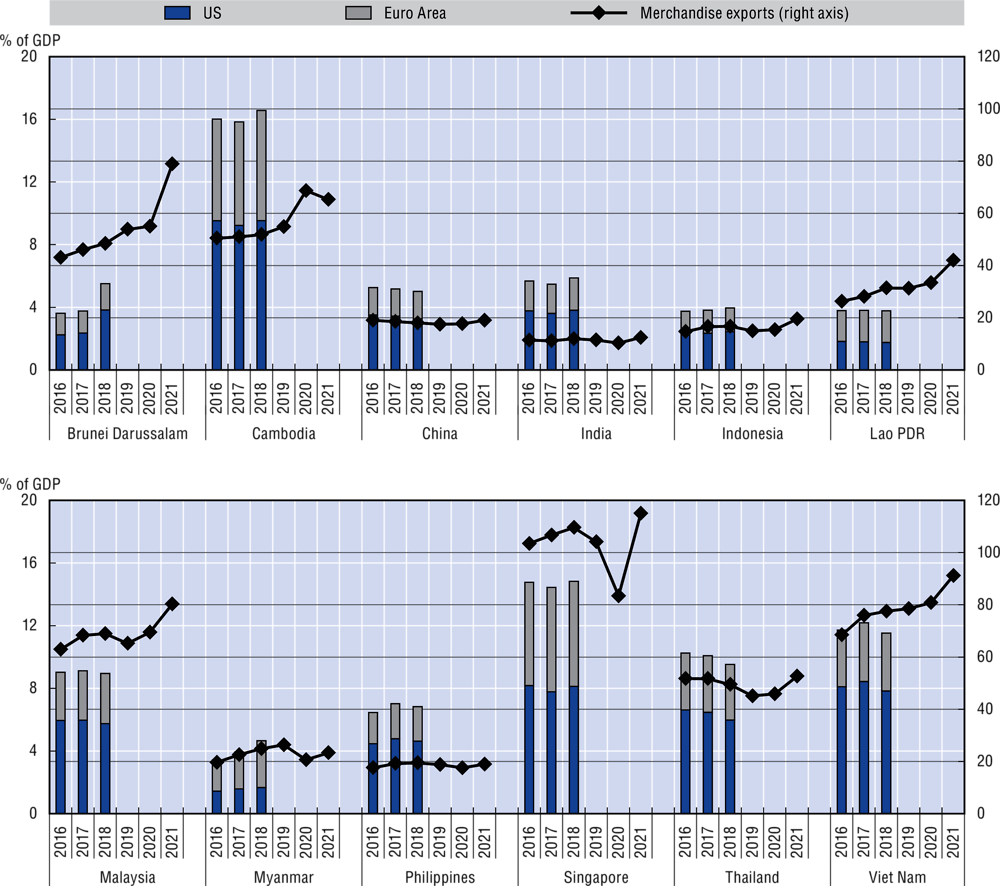

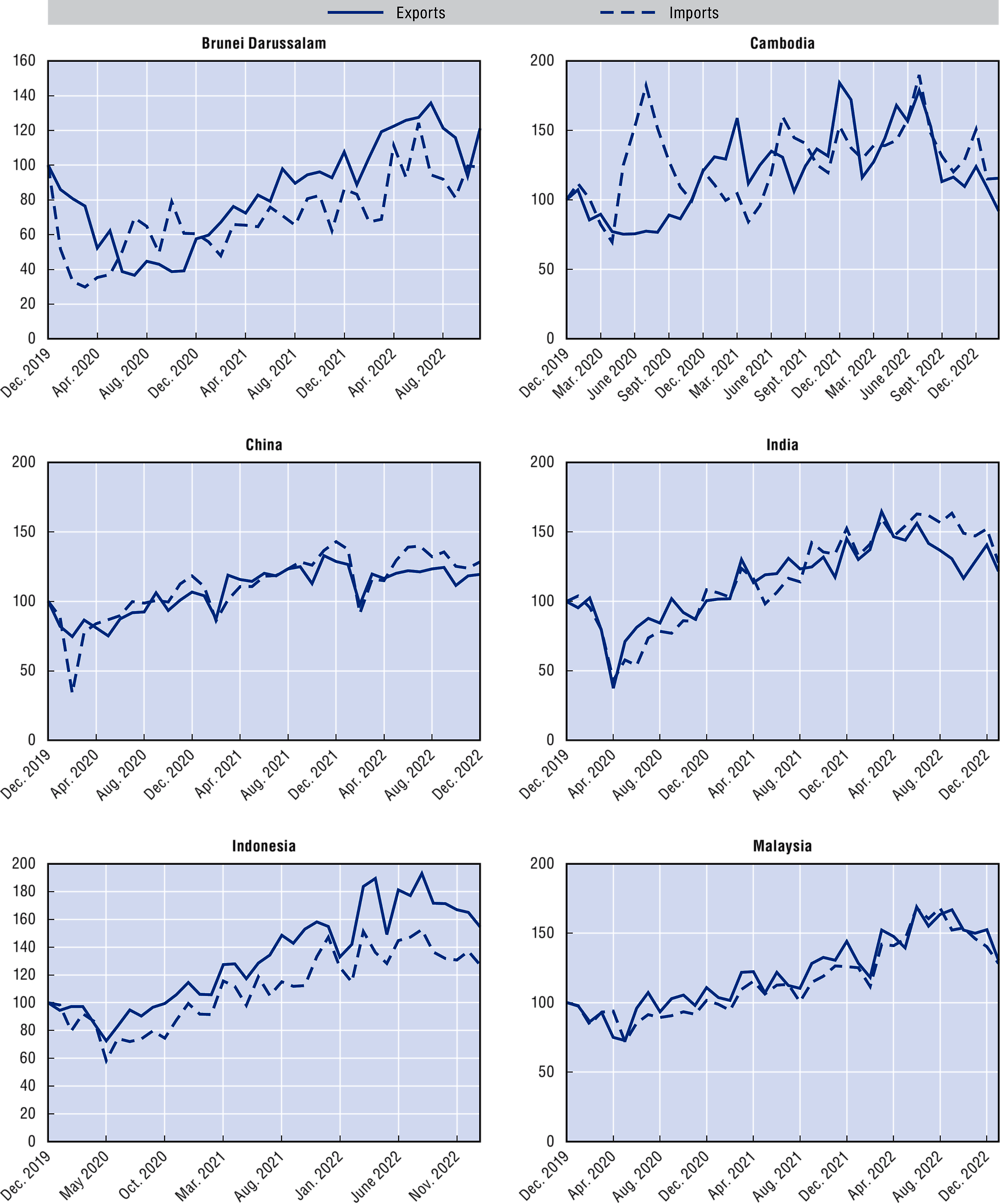

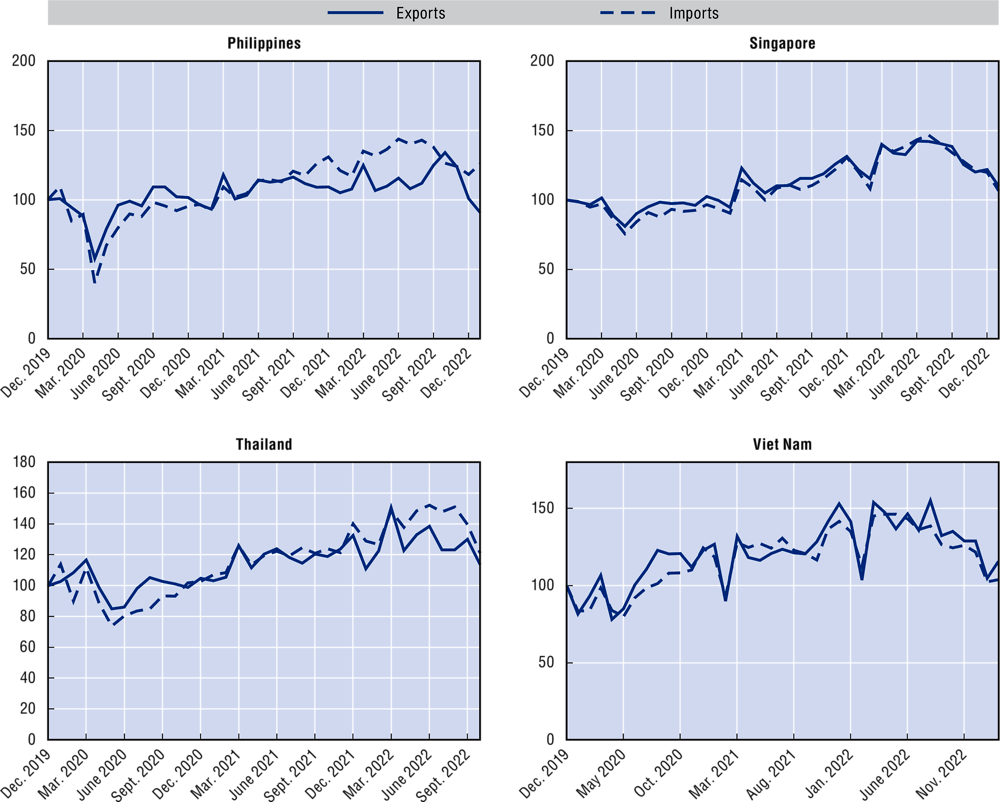

Strong trade and goods exports have supported most Emerging Asian economies amid global uncertainty in 2022, though slowing global growth is expected to weaken these supports in 2023 (Figure 1.33).

As China has reopened its borders, its imports are expected to increase significantly in 2023. Services trade is expected to receive a big boost from China’s rebound (see the next section for more details). At the same time, over the last few years, ASEAN economies have made a considerable effort to create an economic environment conducive to business activity. Measures include streamlined tax policies and regulations, improvement in skill and the expansion and upgrade of communication and transport infrastructure. The region also benefited from further trade integration with economies outside the bloc via a new trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), effective from January 2022. These developments have allowed for increased diversification of exports, which stabilises export revenue and can promote export growth (Box 1.2).

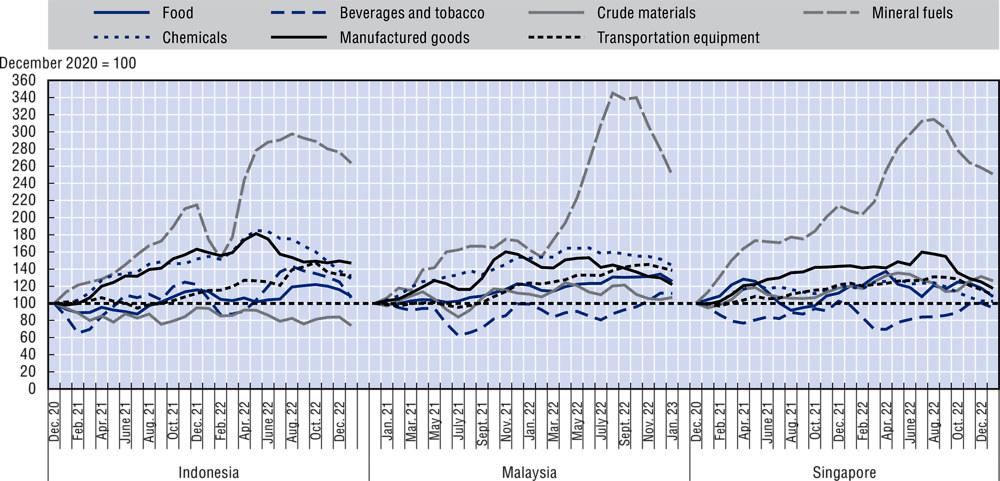

It is notable that, following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Emerging Asian economies experienced striking changes in the composition of trade flows even as exports performed strongly throughout 2022. For example, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore witnessed a huge surge in demand for manufactured goods, mineral fuel and chemicals (Figure 1.34).

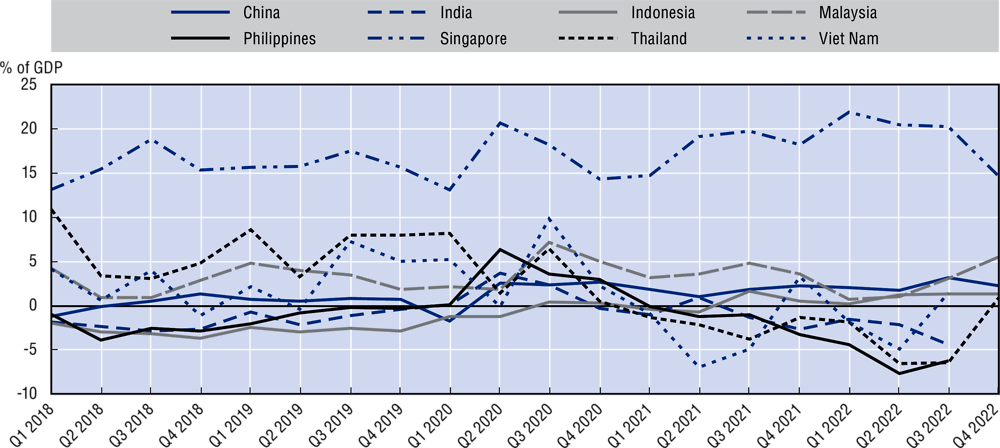

The current account balances (CABs) of Emerging Asian economies as a proportion of GDP have mostly deteriorated after the pandemic (Figure 1.35). Although exports remained strong across most of Emerging Asia, services income accounts continued to suffer from pandemic-related restrictions. This particularly affected countries that are reliant on tourism. On a positive note, the reopening of China and an expected increase in its outbound tourism will generate sufficient recovery in services income accounts to improve CABs in the region overall.

Figure 1.33. Evolution of exports and imports of goods for selected Emerging Asian economies, December 2019 to February 2023

December 2019 = 100

Note: Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Box 1.2. ASEAN’s exports show increasing diversification

Export diversification is good for the region as it helps to stabilise export revenues and leads to higher export growth (Villafuerte et al., 2018; Markakkaran and Sridharan, 2022). Most importantly, it makes exports less susceptible to external shocks (Hong, 2021). An adverse external shock typically leads to losses in export earnings, with the size of the losses depending on the country’s export composition and key trading partners. When a country concentrates its exports in only few commodities, especially primary commodities, and has only a few trading partners, it is more vulnerable to economic shocks. Export earnings over 2009-19 were highly volatile for countries with concentrated exports, such as Lao PDR and Myanmar, and less so for countries with higher diversification, such as Viet Nam (Hong, 2021).

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is commonly used to measure export concentration or diversification. The index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher concentration and lower values indicating greater product diversification. The index shows that diversification of exports is increasing in the region (Villafuerte et al., 2018). Exports from ASEAN economies are highly diversified in both products and trading partners, with an HHI of 0.027 and 0.08, respectively, over the period 1995-2019 (Hong, 2021). The pattern shows that export diversification in ASEAN has been continuous over the last couple of decades (Noureen and Mahmood, 2016; Villafuerte et al. (2018), although the pace varies. Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand have shown consistently higher degrees of export diversification in products and trading partners since 1995. In contrast, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Philippines and Viet Nam have only recently started export diversification, with increasing participation in regional value chains (Villafuerte et al., 2018). The changing composition of both gross and value-added exports confirms export diversification, with most economies experiencing shifts in the ranking of top industries and their export share (Villafuerte et al., 2018). In Thailand, for example, machinery and transport equipment represented the top share of exports in 2016, having risen from fourth place in 2000, with electric and electronic products slipping to second. Analysis of the determinants suggests that foreign direct investment, domestic investment, competitiveness, real depreciation of domestic currency, financial sector development and institutional strength are significantly and positively related to export product diversification (Noureen and Mahmood, 2016).

Strengthened inter-regional trade ties and diversification of export products and partners have increased the robustness and resilience of ASEAN’s exports and supply chains, even amid all the uncertainties that have characterised the global economy in recent years (Floristella and Chen, 2022).

Figure 1.34. Exports of goods by selected sectors in selected ASEAN economies, January 2021 to January 2023

December 2020 = 100, 3-month moving average

Note: Latest data as of 17 March 2023.

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on data from CEIC and national sources.

Figure 1.35. Current account balances of Southeast Asia, China and India, Q1 2018 to Q4 2022

Percentage of GDP

The current account balances (CABs) of Emerging Asian economies as a proportion of GDP have mostly deteriorated after the pandemic (Figure 1.35). Although exports remained strong across most of Emerging Asia, services income accounts continued to suffer from pandemic-related restrictions. This particularly affected countries that are reliant on tourism. On a positive note, the reopening of China and an expected increase in its outbound tourism will generate sufficient recovery in services income accounts to improve CABs in the region overall.

China ending zero-COVID policy will have a major impact on the region

China is a major trading partner for most of Southeast Asia as well as the largest consumer of various commodities globally. Accordingly, its decision to abandon its zero-COVID policy has important ramifications for other economies in the region. Furceri, Jalles and Zdzienicka (2017) show that the economic impact of a slowdown in China on other economies has increased significantly since the beginning of the 2000s, and that a 1% negative shock to China’s GDP has a 0.2% spillover effect to other economies, with the effect more pronounced for neighbouring Asian economies.

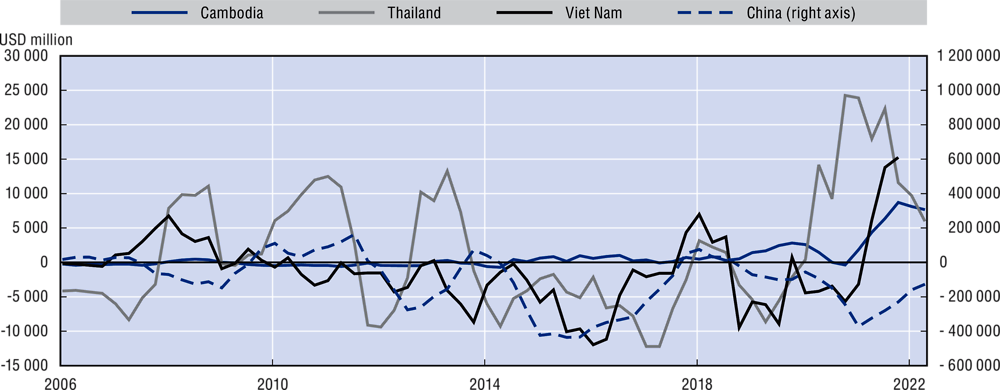

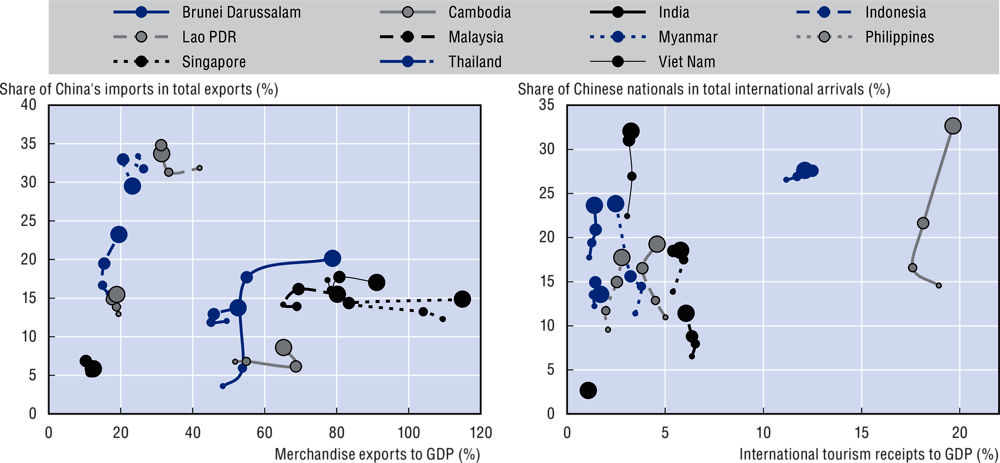

In terms of trade, Lao PDR and Myanmar have the region’s highest export dependence on China, with total merchandise exports between 2018 and 2021 averaging 32.9% and 31.9%, respectively (Figure 1.36). The share of exports from Indonesia and Brunei Darussalam to China has risen steadily over time and stands at 23.2% and 20.1%, respectively, leaving these economies set to benefit from China’s reopening.

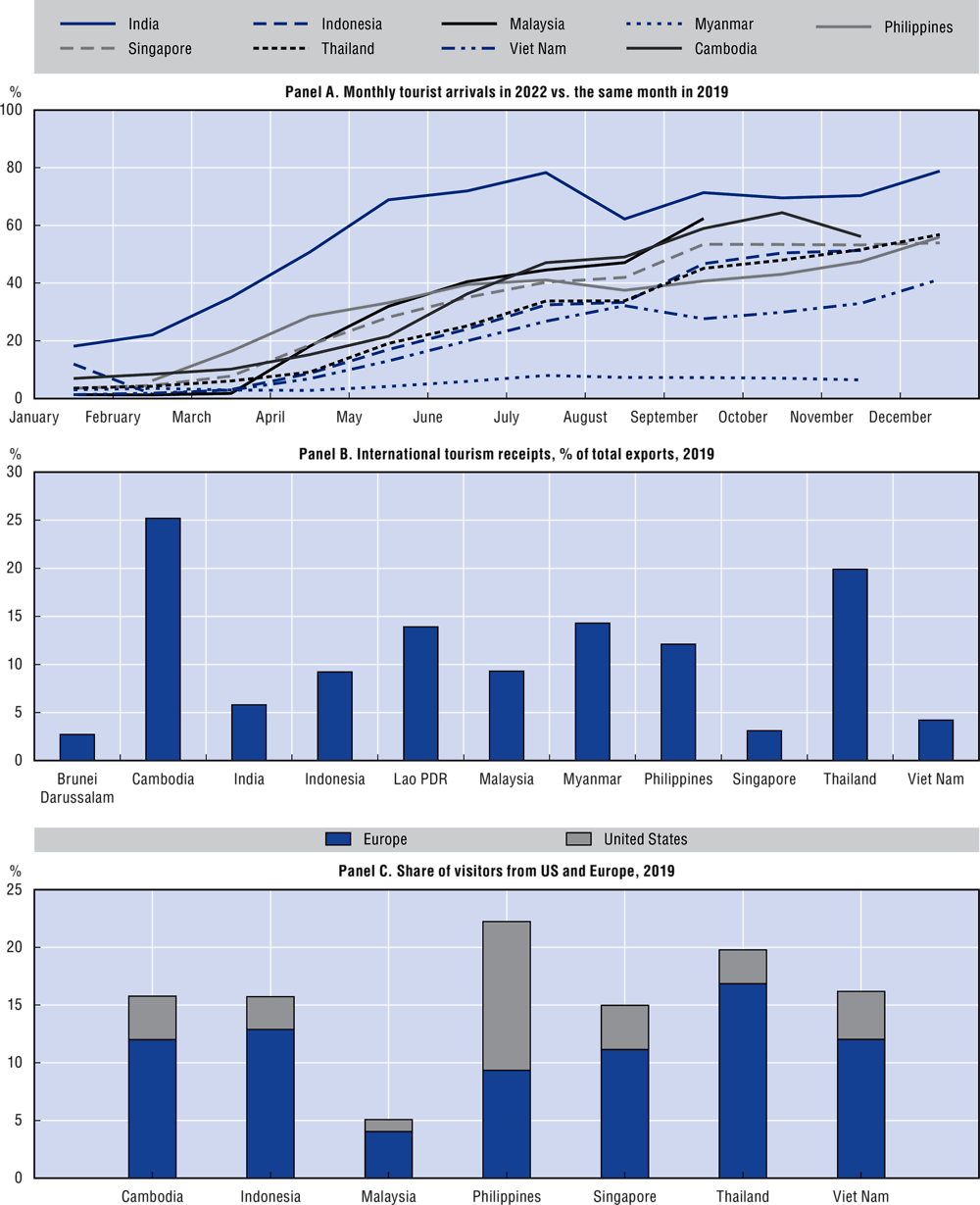

As for tourism, the removal of China’s zero-COVID policy should boost Chinese tourist arrivals in the region. Prior to implementation of the policy, China was the primary source of tourists for many Southeast Asian countries, which suffered a sharp drop in tourism during the pandemic. According to the World Tourism Organization, international tourist arrivals to Southeast Asia were 85% lower from January through July 2022 than over the same span in 2019, though the figures improved steadily each month.

Figure 1.36. Dependence of selected Asian countries’ merchandise exports (2018-21) and international tourism receipts (2015-18) on China

Note: Bubble size indicates the year of observation; larger bubbles indicate more recent data.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on the data of the IMF, WB and National Sources.