Chapter 1 examines the importance of cities and urban areas in the development of political violence in North and West Africa since 2000. Using disaggregated data on population and conflict, the chapter shows that violence is predominantly rural across the region. However, while most violence currently occurs in rural areas, the number of violent events also decreases with distance to cities, suggesting that proximity to cities is important for armed groups and their adversaries. In the last 22 years, nearly half of all violent events occurred within just 10 kilometres of an urban area. The chapter also shows that violence tends to oscillate between urban and rural areas over time. As conflict waxes or wanes in one part of the region, so too does the importance of either rural or urban spaces. Finally, the chapter highlights the key role played by jihadist organisations in the current ruralisation of violence, particularly in the Sahel, where extremist groups exploit the resources provided by rural areas.

Urbanisation and Conflicts in North and West Africa

1. How cities shape conflict in North and West Africa

Abstract

Key messages

Violence tends to oscillate between urban and rural areas over time.

Violence is currently predominantly rural in North and West Africa.

When violence occurs in rural areas, it decreases as the distance from cities increases.

Jihadist groups contribute to the ruralisation of conflicts, particularly in the Sahel.

In recent years, the crucial importance of cities and urban areas in North and West Africa as sites of conflict has attracted increasing attention from policy makers. It is in cities that state power and military force tend to be visibly present and where the confluence of social, political and economic currents shapes daily life. Cities also bring together highly educated and politically dissatisfied youth who may potentially turn to violence. In June 2009, for example, Nigerian security forces asked a group of men affiliated with the Boko Haram sect to comply with a law mandating that motorcyclists wear helmets. The men refused to comply, and in the confrontation that followed, an estimated 800 people were killed in Maiduguri alone, including Mohammed Yusuf, the founder of Boko Haram. As the sect became increasingly violent, it shifted its activities from the urban areas around Maiduguri to rural areas, where security forces were less able to curb their activities.

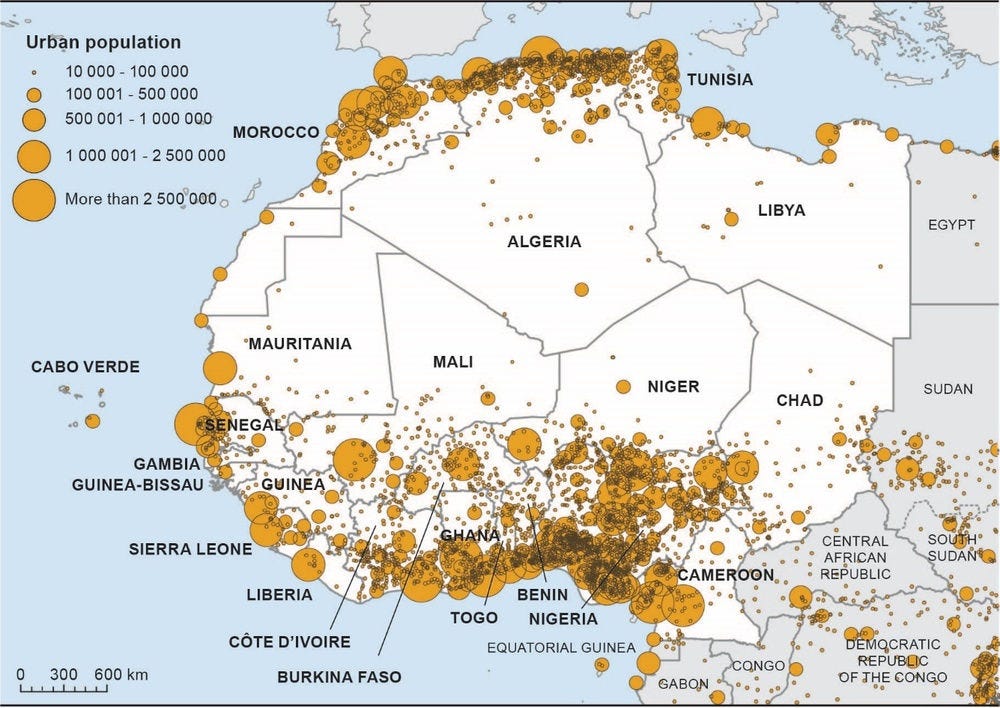

The Boko Haram uprising is an extreme example of a more general dynamic where violent extremist organisations move between urban and rural areas in reaction to the willingness and ability of government forces to counter them. The expansion of such armed groups is taking place in a region undergoing rapid urbanisation, with population shifts from rural to urban areas and accelerated growth in cities (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]), Map 1.1. The effect of this process on the distribution of armed conflict in North and West Africa has not received sustained examination (Chapter 2). While cities and urban areas have always been sites of conflict, given their political and economic importance, many insurgencies, rebellions and separatist movements have often been associated with rural hinterlands. It is still not clear whether increased urbanisation in North and West Africa has increased violent events in urban areas or whether political violence is predominantly rural in nature.

Map 1.1. Urban population in North and West Africa, 2015

Source: Authors based on Africapolis data (OECD/SWAC, 2020[1]), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

This study’s combined use of population and conflict data allows for a close analysis of how conflicts have evolved spatially over a period of more than 20 years in the region. This opens a new window on the spatial lifecycle of conflicts, which can help to inform security policies in North and West Africa. In a region of rapidly shifting violence, understanding where violence emerges, spreads and eventually dissipates can help design place-based policies to address the roots of conflict.

Urbanisation or ruralisation of conflict?

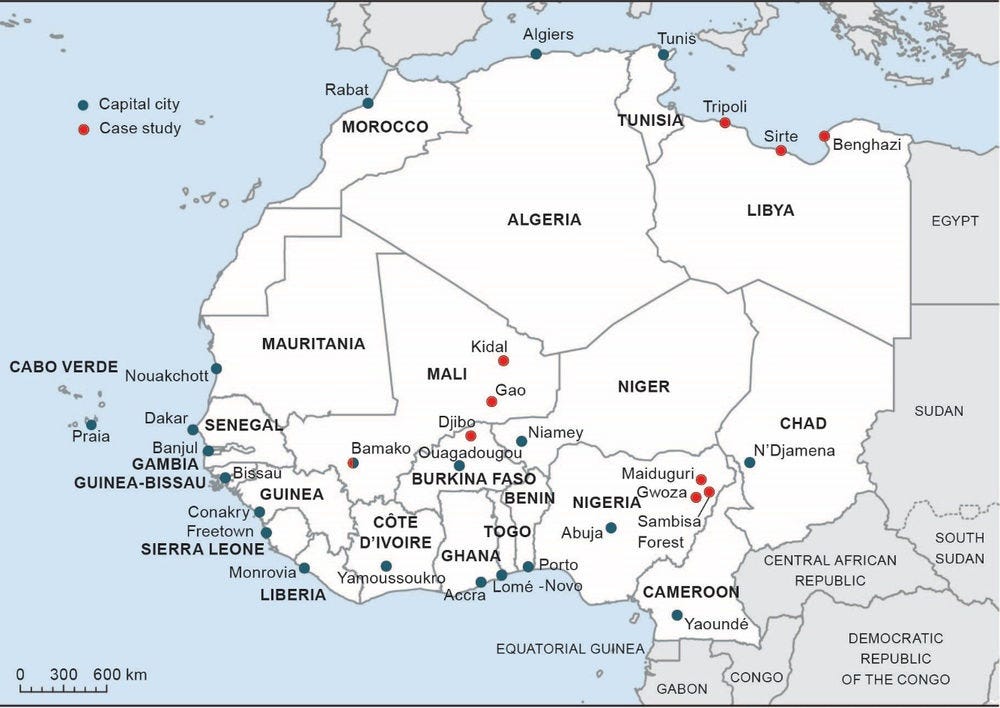

The strategic importance of cities in North and West Africa calls for spatialised approaches that can simultaneously map the long-term evolution of violence in the region and the local factors that explain why conflict tends to be concentrated in urban or rural areas (Chapter 3). This report combines a regional approach to conflict with a local analysis of cities, examining the relationship between population density and political violence in 21 North and West African countries and in ten case studies (Map 1.2).

Four fundamental questions are discussed in the report: Do conflicts affect rural hinterlands or urban areas? Have armed conflicts become increasingly focused on urban areas over time? Are larger urban areas more prone to violence than smaller ones? And in which regions and countries is political violence predominantly rural or urban? Addressing these questions helps illuminate how violent actors exploit the advantages of cities and their hinterlands to spread conflict in the region. The spatial analysis adopted in this report can also help to design policy responses that respond to different forms of localised violence, both in rural and in urban areas.

Map 1.2. Countries and case studies covered in this report

Source: Authors.

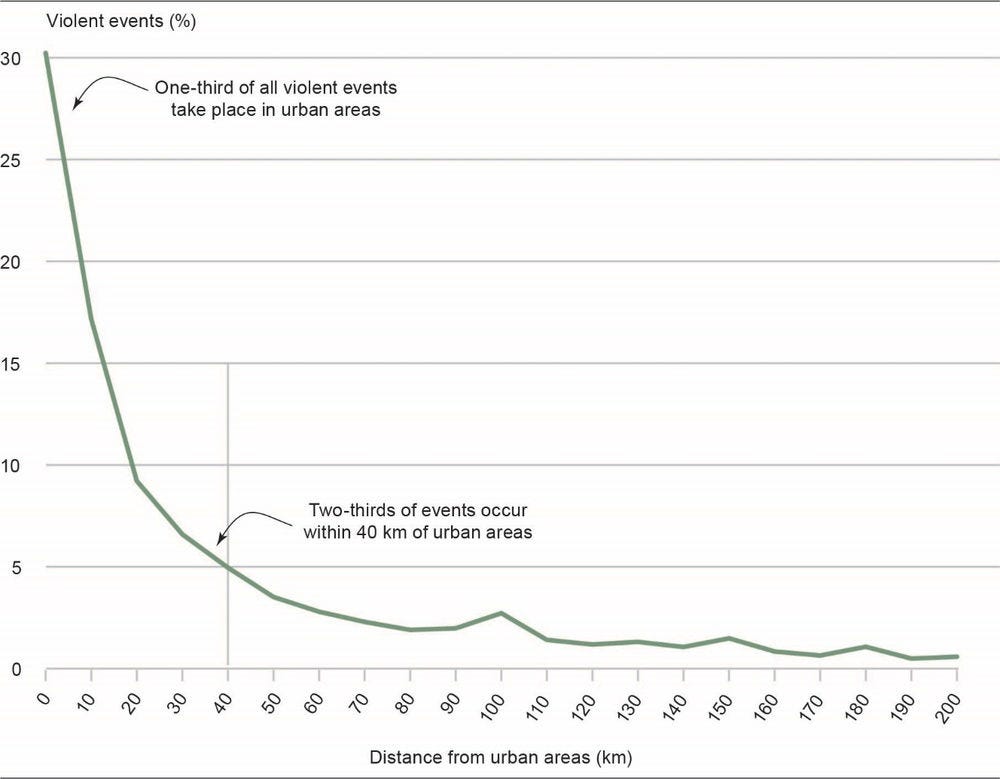

Violence tends to cluster near urban areas

First, the report examines whether political violence is predominantly rural or urban in the region (Chapter 5). The analysis of disaggregated conflict data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED, 2022[2]) and population data from WorldPop (2022[3]) suggests that, while most of the violence has occurred in areas of lower density, political violence is spatially associated with urban areas, most frequently near cities and urbanised places. In the last 22 years, 47% of all violent events occurred within just 10 km of an urban area, and 68% occurred within just 40 km. The report also shows that the relationship between urban population and violence exhibits a classic distance-decay effect: the further from an urban area, the fewer violent events are observed (Figure 1.1). The strong relationship between urban population and violence is hardly a surprise, given the importance of North and West African cities as sites of state authority, economic importance, religious education, and political control and contestation.

Figure 1.1. Violent events by distance from urban areas in North and West Africa, 2000-22

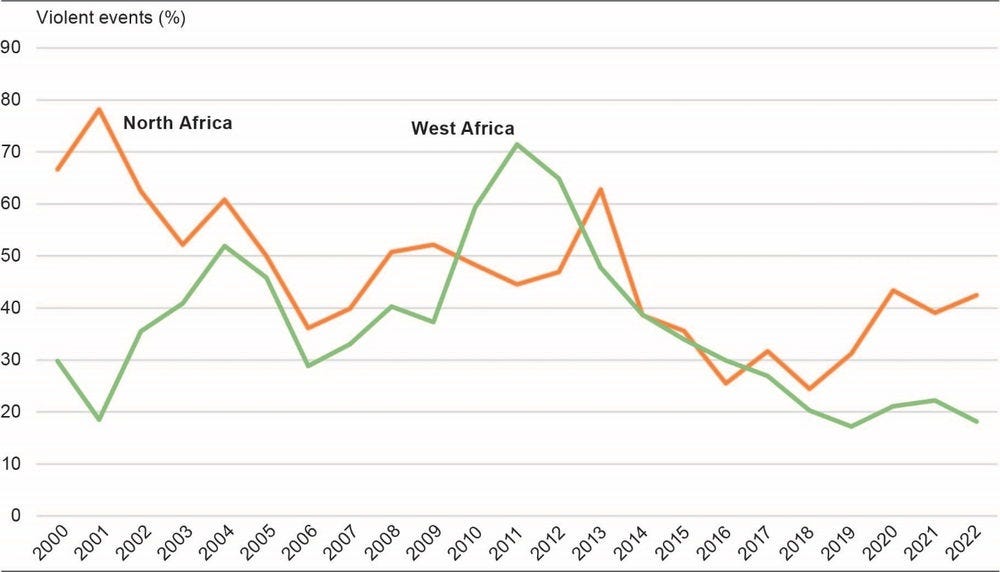

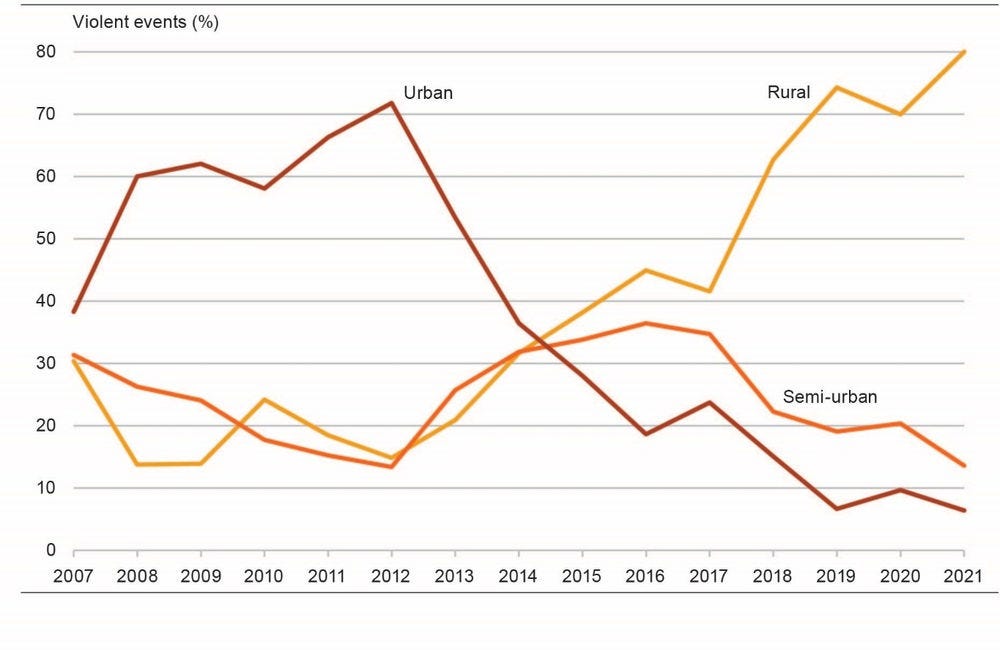

Conflicts are becoming more rural across North and West Africa

The report then examines how the rural-urban geography of armed conflicts has changed in the past two decades. It shows that the regional relationship between urban areas and violence has been highly variable over time: urban violence is predominant in only half the years in the study, with peaks occurring in 2004 and 2011-12. However, while urbanisation has accelerated, violence has become more rural in character across the region (Figure 1.2). Less than 20% of the violent events recorded in 2022 in West Africa are located in urban areas, compared to just over 70% a decade ago. A similar trend can be observed in North Africa, where urban violence now represents 40% of violent events, against a peak of nearly 80% in the early 2000s. The increase of violence in rural areas observed since the early 2010s fails to support the “urbanisation of conflict” hypothesis, which posits that the growth of cities in Africa should lead to both a decline of rural civil conflict and an increase in violent conflicts in cities.

Figure 1.2. Violent events in urban areas per sub-region, 2000-22

This temporal variability has to do with the spatial ebbs and flows of violence in the region. For instance, the Libyan civil wars correspond to the most recent peak in the proportion of violence occurring in urban areas, since Libya was already a highly urbanised country before the violence. Now that violence has dissipated there and emerged elsewhere, such as in the still largely rural Central Sahel, the overall locational trend in violence has shifted from urban to rural. This is not to say that cities and urban areas do not matter for these current conflicts. As the report shows, even in states with low levels of urbanisation, such as in the Sahel, a high propensity for conflict to cluster can be observed near small or peripheral cities and towns.

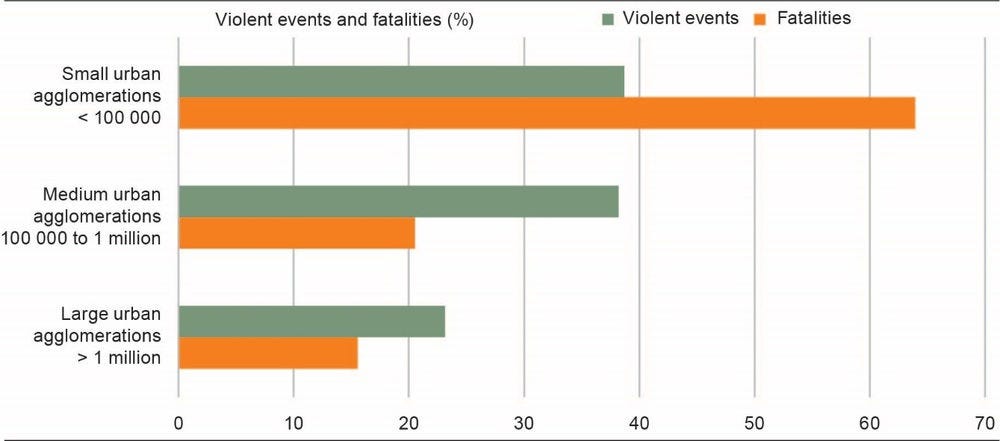

Violence predominantly affects small cities

The intensity of violence decreases with city size. Small cities are the type of urban settlement most affected by political violence in the region (Figure 1.3). The spatial proximity of these urban centres to the rural conflict areas explains why, in 2015, nearly 65% of the fatalities and 40% of the violent events recorded in North and West Africa cities occurred in urban areas of less than 100 000 inhabitants. The intensity of violence observed in these small centres is far greater than their demographic weight in the region (32%). Medium cities of between 100 000 and 1 million inhabitants record a significant proportion of violent urban events (38%) but only 20% of the urban fatalities. Large urban centres have largely been spared from the violence, including capital centres such as Bamako, Niamey, N’Djamena and Ouagadougou that are increasingly surrounded by conflict areas.

Figure 1.3. Violent events and fatalities by urban categories in North and West Africa, 2015

Note: These results build on the Africapolis database, which maps the perimeter of each urban agglomeration and calculates its population. Produced by the OECD, Africapolis is based on a spatial approach and applies a physical criteria (a continuously built-up area) and a demographic criteria (more than 10 000 inhabitants) to define an urban agglomeration. Africapolis population estimates in both North and West Africa are only available for 2015 (Chapter 3). An update should be available in 2023.

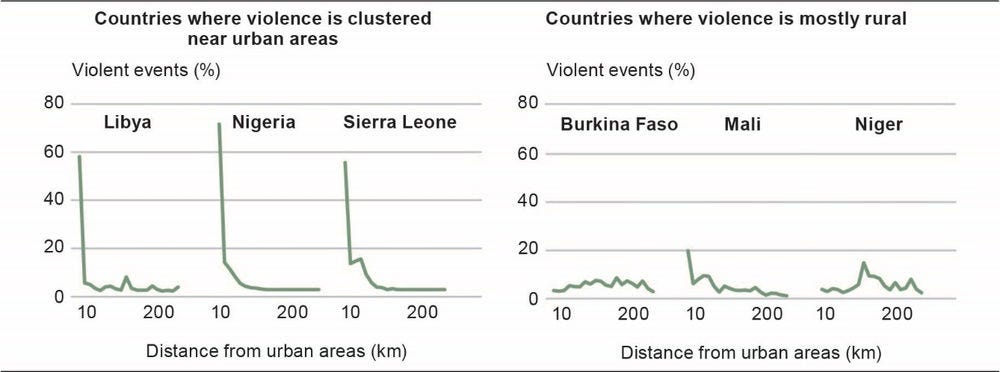

Rural violence has become dominant in the Sahel

Last, the report examines the distribution of rural and urban violence across North and West Africa. It reveals that the relationship between population density and political violence varies considerably across and within states. While at the regional level, the intensity of violence clearly decays with distance from urban areas, some states show a much stronger tendency towards rural conflict than others. For example, the civil conflicts in Libya, Nigeria and Sierra Leone have consistently been highly urban, with numerous violent events in or near urban areas, while that is not the case with the recent strife in the Sahel (Figure 1.4). In Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, most of the violent events have occurred far from urban areas, in the arid regions of the Sahara, for example, but also in peripheral regions where cities are few and far apart, such as the Seno Plain in eastern Mali. In Mali, more than 80% of violent events in 2022 were in rural areas. The fact that these three countries show a similar trend is not surprising, since they are all currently facing major jihadist insurgencies.

Figure 1.4. Violent events by distance from urban areas, selected countries, 2000-22

This ruralising trend owes much to the fact that violence affecting Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger has shifted from the Sahara to the Sahel and its southern margins in recent years (OECD/SWAC, 2022[4]), making the control of cities less important than in the early years of the insurgencies. In 2012, for example, Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Dine and the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) advanced very quickly across northern Mali to seize Timbuktu and Gao, two commercial and religious centres. At that time, most violent events occurred in or near urban areas, as violent organisations fought for control of cities and the roads connecting them. Since then, the proportion of violent events associated with jihadist organisations in urban areas has gradually declined, and it now represents less than 10% of the total seen a decade ago. Since 2014, it is these organisations that have been most frequently responsible for rural violence, accounting for as much as 80% in 2021 (Figure 1.5).

Today, jihadist groups do not have to physically control cities to control civilians and gain access to natural, mineral and agricultural resources. In the Inner Niger Delta, for example, they impose embargoes on rural communities that refuse to let them rule or are protected by the military, and threaten to kill traders, politicians and civil society leaders who live in cities but own property in rural areas. This strategy of intimidation has enabled groups like Katibat Macina to gain control over rural areas, impose local taxes on trade and steal cattle on a large scale, which has made the Central Sahel the area where rural violence is most prevalent. Similar dynamics can be observed in the Lake Chad region, which has recorded the highest number of violent events and fatalities since the late 2000s in West Africa. In northern Nigeria, especially, Boko Haram and its splinter group the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) have exploited the human, financial and agricultural resources of both urban and rural areas, depending on the response of the four countries surrounding Lake Chad.

Figure 1.5. Violent events involving select jihadist organisations, 2007-21

Note: The following organisations are considered: Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Dine, Ansaroul Islam, Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), Group for Supporting Islam and Muslims (JNIM), Katibat Macina. Under the United Nations (2020) definition, cells of 1 500 or more people per square km are classified as urban, those between 300 and 1 499 as semi-urban, and those below 300 as rural.

More generally, the evolution of the last two decades suggests that violence tends to shift between urban or rural areas depending on two opposing forces: the local strategies of non-state actors, and the military responses of government forces and their allies. The balance of power between these two forces is what eventually determines the life cycle of an armed conflict, from its emergence to its resolution. Both state and non-state actors are likely to make use of spatial features, such as distance, borders and cities, to gain access to localised resources, control the civilian population and ultimately defeat their opponents. None of them should be considered in isolation. In Nigeria, for example, the military’s decision to gather its troops inside garrison towns such as Bama or Monguno has allowed Boko Haram and ISWAP to fill the void left by government forces in the countryside. In Mali, violence against civilians has increased since Western troops were replaced by Russian mercenaries in December 2021, particularly in rural areas of the Inner Delta and Dogon country.

A spatial approach to conflict and cities

The spatial analysis adopted in this report expands previous efforts by the OECD Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC) to document the changing geography and conflict dynamics of North and West Africa since the end of the 1990s (OECD/SWAC, 2020[5]; 2021[6]; 2022[4]). Two complementary approaches are used to understand how cities shape conflicts in the region, whether violence is becoming more urban, whether larger or smaller cities are more violence-prone, and which areas are the most affected by violent events (Chapter 3).

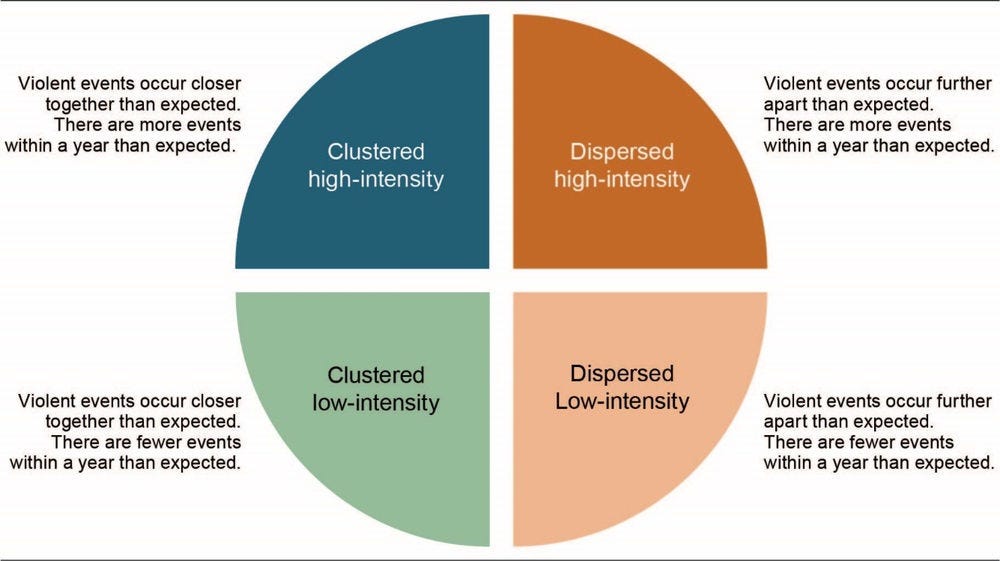

First, the report uses the Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator (SCDi) to map recent shifts in the intensity and distribution of violence across North and West Africa. The SCDi is an innovative tool developed by the OECD/SWAC (2021[6]) to capture rapid changes in the geography of conflict (Figure 1.6). Using a grid of 6 540 “cells” of 50 km by 50 km from Dakar to N’Djamena and from Algiers to Yaoundé, the indicator measures whether politically motivated violence tends to intensify, decrease, spread or relocate to neighbouring regions (Walther et al., 2021[7]). The report shows that political violence has increased steadily since the mid-2010s, and that large transnational areas are prone to high-intensity and clustered violence (Chapter 4).

Figure 1.6. The Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator (SDCi)

Notes: The SCDi measures two essential geographic dimensions of political violence within a defined region over a year: i) the locations of violent events relative to each other (clustering/dispersion), and ii) the number of events over a given time period compared to a long-term regional average (high or low intensity). A region that experiences two or more violent events within a year can then be classified along both dimensions and mapped.

Source: Authors.

Second, the report combines population and conflict data to examine long-term trends in urban violence from January 2000 to June 2022 across the entire region. This approach aligns with previous work on the geography of violence in the region (OECD/SWAC, 2014[8]) that tends to see the northern and southern “shores” of the Sahara as two related battlefields for states and non-state organisations. It captures two of the continent’s major spatial concentrations of urban agglomerations: a North African cluster that extends along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts and a West African cluster along the Gulf of Guinea (OECD/SWAC, 2020[5]).

To study how cities and urbanisation are related to political violence, the report uses WorldPop (2022[3]), a global gridded population dataset used to generate population density since 2000 (Chapter 5). The population densities provided by WorldPop are classified according to the recent “degree of urbanisation” categories established by the United Nations (2020[9]): urban, semi-urban and rural. The population data are then combined with disaggregated conflict data provided by ACLED (2022[2]) to study the spatial and temporal distribution of violence in North and West Africa. The analysis focuses on three types of event representative of the armed conflicts in the region: battles between armed groups and/or state forces, explosions and remote violence, and violence against civilians. The resulting data involve nearly 51 000 violent events and 193 000 fatalities from January 1997 to June 2022.

The quantitative approach adopted in this report is complemented by a historical analysis of a selection of cities and zones that have particularly suffered from armed conflict and terrorism in North and West Africa. From Bamako to Maiduguri, and from Kidal to Tripoli, the ten case studies selected for this analysis highlight the many factors that explain why politically motivated violence emerges in certain cities, how insurgents mobilise urban populations to achieve their political objectives, and how state forces respond to the spread of violent extremist organisations in urban and rural areas.

Perspectives

The last two decades have been characterised by an unprecedented intensification and spread of political violence in North and West Africa. While violence has largely subsided in recent years north of the Sahara, since the end of the Second Libyan Civil War, several clusters of violence are now coalescing across the Sahel and its southern periphery, a situation that has had few equivalents in recent history. An increasing proportion of the violent activities observed in the last 20 years occurs near borders (OECD/SWAC, 2022[4]) and, as this report shows, in rural areas, in small cities of less than 100 000 inhabitants and around the peripheries of larger cities. The report shows that the processes that lead to this pattern of violence are anchored in the efforts of states to manage sovereignty within their own borders and in the actions of various groups that seek to challenge, supplant or somehow reconfigure the state.

The intensification and diffusion of violence in rural areas tends to cut off major cities from their hinterlands. Since the mid-2010s, major urban centres such as Niamey, Ouagadougou or Bamako have been surrounded by ever-expanding areas of conflict. Largely unaffected by political violence, these centres form a shrinking archipelago in which communication and movement between secure areas become increasingly difficult. The fragmentation of national territories that results from this evolution reinforces the gap between the largest cities, the focus of most of the political institutions and economic activity, and the rest of the country. In Mali, for example, the diffusion of the conflict to large expanses of the countryside has alienated a growing proportion of the rural population from the Greater Bamako region, where more than 90% of formal businesses were located before the crisis (OECD/SWAC, 2019[10]).

The fact that government forces are only able to ensure security in a few large urban areas is not simply detrimental to national cohesion; it can potentially threaten the survival of the state, if the capital city is conquered by rebels or jihadist movements. So far, military attempts to break the encirclement of the main cities and to restore the continuity of the state’s presence have met with limited success. In northern Burkina Faso and Nigeria, for example, government forces have had little success in maintaining the necessary lines of communication and mobility between urban areas, let alone providing security in rural areas. Convoys organised to resupply besieged towns are regularly attacked by jihadist groups, whose mobility in rural areas is vastly superior to government forces’. In September 2022, for example, JNIM militants ambushed a civilian convoy escorted by the Burkinabè army travelling to Djibo, killing 27 soldiers and 10 civilians and destroying 95 trucks.

The current ruralisation of violence in the Sahel does not mean that large cities have lost their strategic importance, as they will ultimately remain key locations and goals for state forces, rebels and other non-state actors. The report suggests that the growing concentration of violence in rural areas corresponds to one of the many stages conflicts pass through in their life cycle. As conflicts emerge, develop and eventually end in one part of the region, the importance for the belligerents of rural or urban spaces shifts. In the long term, urban areas are likely to remain important focal points for violent activities.

The historical analysis presented in Chapter 5 demonstrates that cities function as a battleground both for the state and for its enemies, in their struggle to redefine societies around secular or religious bases. For the state and its elites, (capital) cities are places of utmost importance, as the seat of political power from which sovereignty can be exerted on the international stage. With border regions, major cities are also vital economic sites where the formal economy can be taxed, and the profits of informal economies can be accumulated.

For the enemies of the state, and especially the jihadist groups, cities are important for similar reasons, but they also represent both a source of mass recruitment and funding opportunities, and a source of perceived moral corruption. In the Central Sahel and the Lake Chad region, reformist movements have entertained an ambivalent relationship to cities in general, considering them as laboratories that propagate new social norms, prohibitions and dress codes, and as a threat to their political agenda, due to their openness to imported values such as democratisation, women’s empowerment or “Western” education.

The report has demonstrated that urbanisation across the region has not automatically led to an increase in urban violence, and cities have not necessarily become the central battlegrounds between state forces and those that challenge them. Instead, as shown by the cases of Nigeria and the Central Sahel, violence has surrounded cities and their peripheries, and rural areas adjacent to cities have become zones of profound insecurity.

Given the trajectories identified by this and previous reports (OECD/SWAC, 2020[5]; 2021[6]; 2022[4]), it is unlikely that the region’s conflicts will subside in the near future. Instead, large urban agglomerations are likely to continue to be islands of state power, while rural areas and smaller cities bear the brunt of insecurity and violence. In the short to medium run, this probably means that major cities and large urban areas are likely to continue to be heavily fortified and securitised by states and their foreign partners, while rural areas are largely left in the hands of opposing forces. However, in the longer term, such cities remain clear targets of ambition for those who are challenging states. The fact that violence is not yet endemic in these cities could change quickly.

A significant part of the reason for this is the profound fragility of many states in the region, of which a lack of military capacity is only one feature. As demonstrated in previous reports, military-led solutions to state challengers in the region have repeatedly failed (OECD/SWAC, 2020[5]; 2021[6]). Individual state forces, foreign powers, multinational interventions and international peacekeeping missions have all been unable to defeat an expanding set of rebels and other challengers on the battlefield. In short, the region’s status quo is the result of political crises and states’ difficulties in developing the institutional capacity to withstand challenges. Political solutions are thus required to change the status quo. Until that process is launched, the region is likely to remain the world’s leading example of transnational instability.

In the meantime, cities and their inhabitants in the region should be supported and protected where possible, given the circumstances. This is not simply because their population can potentially be radicalised, but because they are places of innovation, dynamism, connection with the wider world and political engagement. If the collective will to push for political solutions to the region’s political challenges is to emerge, cities are the sites where such movements are likely to originate.

References

[2] ACLED (2022), Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, https://acleddata.com.

[4] OECD/SWAC (2022), Borders and Conflicts in North and West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6da6d21e-en.

[6] OECD/SWAC (2021), Conflict Networks in North and West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/896e3eca-en.

[1] OECD/SWAC (2020), Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b6bccb81-en.

[5] OECD/SWAC (2020), The Geography of Conflict in North and West Africa, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/02181039-en.

[10] OECD/SWAC (2019), “Businesses and Health in Border Cities”, West African Papers, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6721f08d-en.

[8] OECD/SWAC (2014), An Atlas of the Sahara-Sahel: Geography, Economics and Security, West African Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264222359-en.

[9] United Nations (2020), Report of the Secretary-General on Implementation of the 2020 World Population and Housing Census Programme and the methodology for delineation of urban and rural areas for international statistical comparison purposes: Report of the Secretary-General, United Nations Statistical Commission, New York, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3847372.

[7] Walther, O. et al. (2021), “Introducing the Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator of political violence”, Terrorism and Political Violence, pp. 1-20, https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2021.1957846.

[3] WorldPop (2022), WorldPop (database), University of Southampton, https://www.worldpop.org.