In line with Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, Chapter 3 analyses necessary policy levers to bring Türkiye’s e-government closer to a matured digital government. The first section focuses on its digital government strategy and its relevance across the public sector. The second section deep dives into management tools, including business cases and agile project management, and financial mechanisms. The chapter finishes by reviewing legal and regulatory frameworks in place in Türkiye.

Digital Government Review of Türkiye

3. Policy levers to lead the digital transformation

Abstract

Introduction

Chapter 2 focused on the contextual factors and institutional models that underpin the digital transformation of Türkiye’s public sector. The institutional arrangements and leadership to co-ordinate are essential to a whole-of-government and coherent approach to digital government. Policy levers allow governments to turn strategy to implementation and delivery, enabling system-wide change to better meet the needs of citizens and businesses, and create value across the public sector.

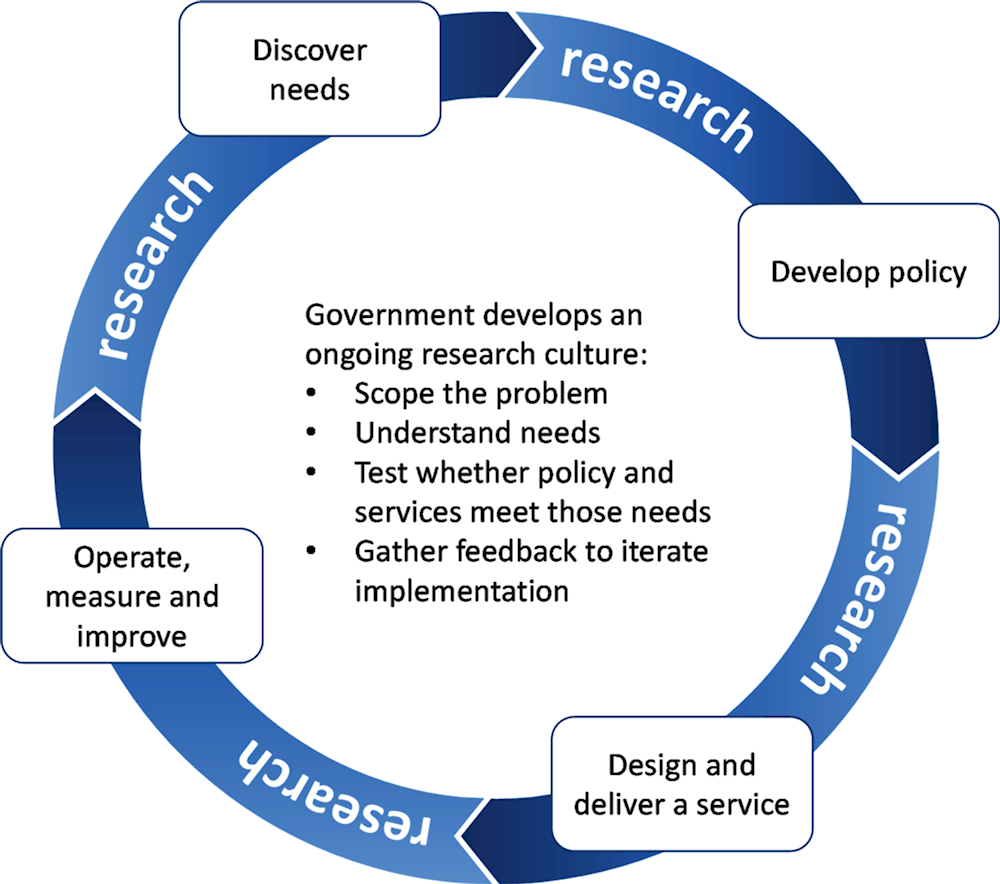

Drawing on Pillar 3 of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]), the E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government (OECD, 2021[2]) identifies policy levers, soft or hard policy instruments, as tools to support governments' digital transformation agenda (see Figure 3.1). It entails clear methods for value proposition (e.g. Business cases), management and monitoring of the implementation, assessment-based procurement of digital technologies and proper regulatory framework. These tools lay firm foundations for critical enablers for digital government and data.

Figure 3.1. The OECD Framework on the Governance of Digital Government – Policy levers

Source: OECD (2021[2]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

This chapter will examine four dimensions: strategy and plan, management tools and financial mechanisms, and regulations and standards. The first section focuses on its digital government strategy and its relevance across the public sector. The second section deep dives into management tools, including business cases and agile project management, and financial mechanisms. The chapter finishes by reviewing legal and regulatory frameworks in place in Türkiye.

Strategy and plan

A digital government strategy is indispensable to achieve digital government maturity with coherency and sustainability at the whole-of-government level. The strategy should set a strategic vision, objectives and priorities, accompanied with the structure and detailed action plans for implementation and monitoring. It should also align with broader national agenda or policy priorities (e.g. administrative reform, sustainable development, climate change and environment, education, science and technology) as well as reflecting sectoral needs and priorities.

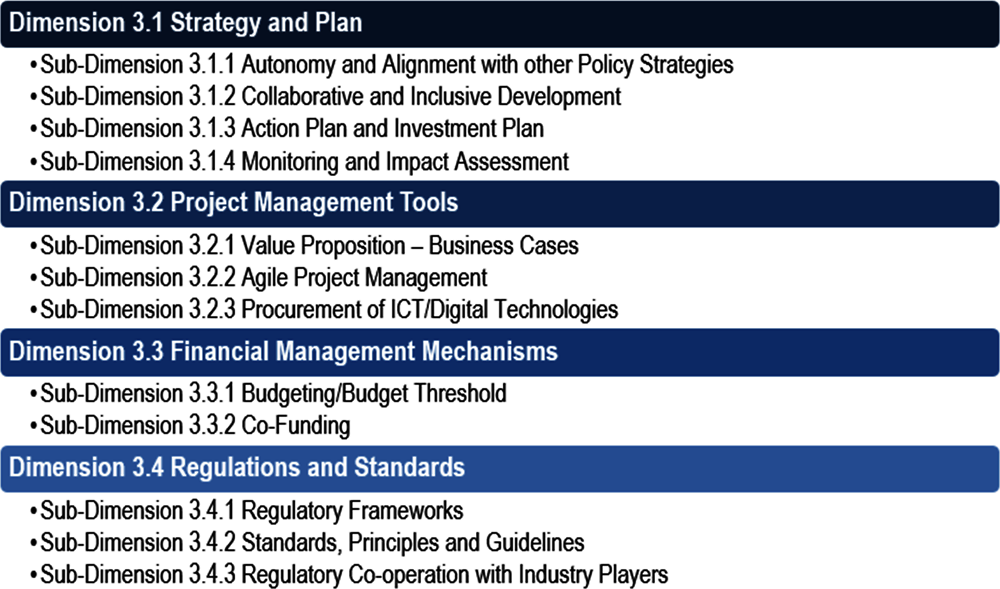

Almost all OECD member countries that participated in the OECD Digital Government Index 2019 have a digital government strategy in place with policy objectives for public sector digital transformation (see Figure 3.2). Depending on the government, these strategies might have different names or be presented in various formats. Some governments choose to have it as a standalone document, while some embed it in a broader national agenda. A key takeaway is that OECD countries recognise the importance of having a strategy to guide governments towards digital government maturity.

Figure 3.2. Existence of a national digital government strategy in OECD countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, Slovakia, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index.

Source: OECD (2020[3]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en, Q.1.

Türkiye has a long-standing history of centrally organised strategies concerning digital transformation.1 Prior to the publication of the most recent digital government strategy in 2016 there has been a consistent narrative of encouraging a ‘citizen-oriented service transformation’ (State Planning Organisation, 2006[4]), ‘designed according to the needs of users’ and which is understood ‘from the design to the implementation’ (Republic of Türkiye, 2014[5]). These ideas have formed the basis for the 2016-2019 National e‑Government Strategy and Action Plan (Ministry of Transport, Maritime Affairs and Communications, 2016[6]) and the subsequent Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023) (Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2019[7]). The National e-Government Strategy, which concluded in 2019, provided a holistic approach to the structuring of e-government (see Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Türkiye’s 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan

Four strategic aims to achieve the vision of an e-government Ecosystem

Strategic aim 1: ensuring the efficiency and sustainability of the e-government ecosystem.

Strategic aim 2: implementing common systems for infrastructure and administrative services.

Strategic aim 3: realising an e-transformation in public services.

Strategic aim 4: enhancing usage, participation and transparency.

Progress made in the framework of the 2016–2019 e-Government Action Plan:

The institutions carried out the process and method transformation studies to provide all services as e-government services.

The Electronic Document Management System is used in all central institutions.

The Centralised Legal Persons Information System (MERSIS) was integrated into the e‑Government Gateway.

Data dictionary studies were started.

Services such as job search, and employment, unemployment and retirement applications are now provided via the e-Government Gateway.

The certificate of inheritance can now be obtained from the e-Government Gateway.

Many service steps for vehicle acquisition and registration are now available on the e‑Government Gateway. Efforts are being pursued to provide services in an integrated manner (more info at page 14).

Applications for the Consumer Arbitration Committee can now be made via the e-Government Gateway.

A social media guide for public institutions was prepared and published in 2019.

Source: EC (2021[8]), Digital Public Administration Factsheet 2021 - Turkey, https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/DPA_Factsheets_2021_Turkey_vFinal.pdf.

Following the change in organisational structure Türkiye published its Eleventh Development Plan which set out an ambition for ‘user-oriented service delivery and effective public administration’. It aims to improve service delivery channels with channel diversity and prioritise the needs of disadvantaged groups (Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2019[7]). In line with the development plan, and building upon the 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan, priority actions in the digital government agenda were set and implemented. The holistic and multi-dimensional national policy document aims to increase competitiveness and efficiency across the public sector (EC, 2021[8]). The implementation of these actions is monitored based on a separately established annual plan, supported by the Presidential Plan & Program Monitoring & Evaluation System. Although the plan includes certain objectives and goals related to digital transformation, they are scoped around e-government applications in public services, not digital transformation of the public sector. It is missing the whole-of-government vision and objectives, as well as clear responsibilities and roles of key relevant stakeholders to ensure successful digital transformation of the Turkish public sector with some of these elements handled in other documents.

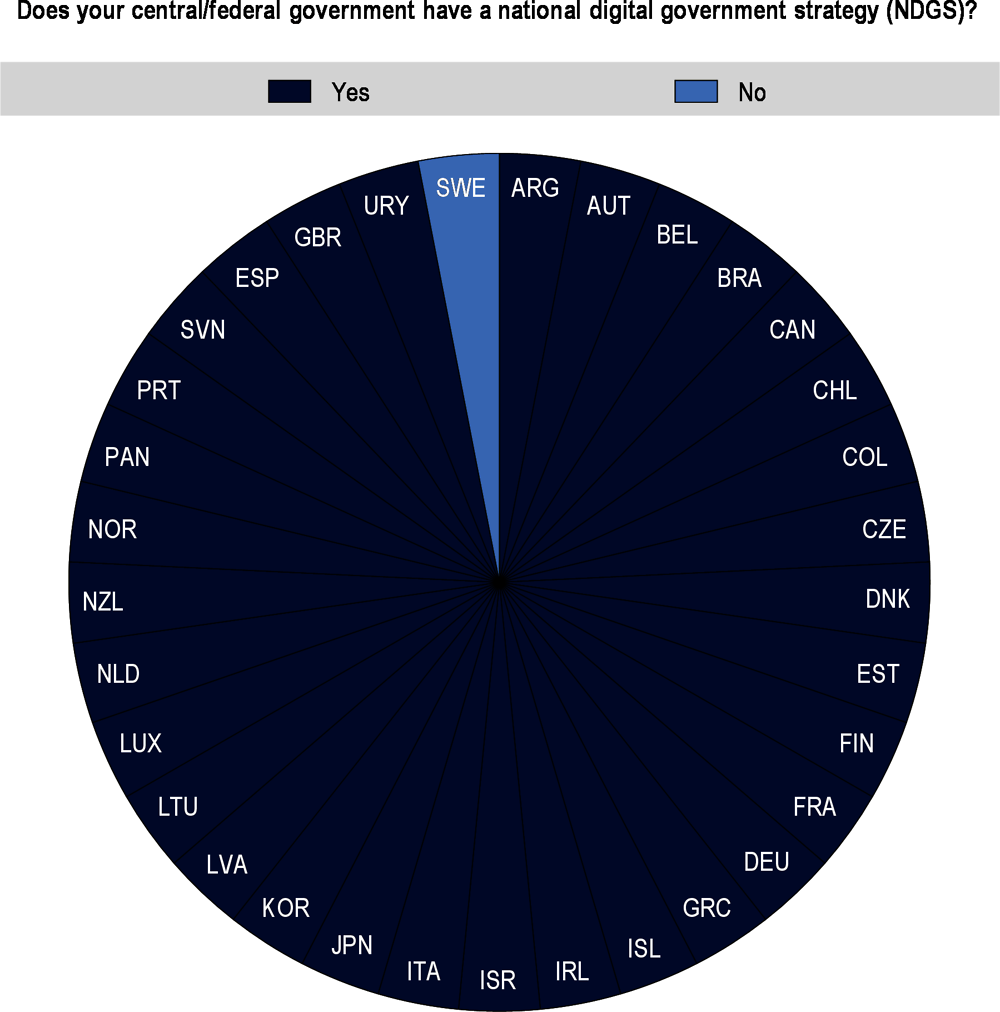

The central digital government strategy was perceived relatively well across the public sector. When questioned about the relevance of the national digital government strategy (2016-2019 National e‑Government Strategy and Action Plan), 47% of respondents rated the relevance of the national strategic approach to digital government policy to their organisation as being strong (see Figure 3.3). Nevertheless, there are opportunities for improvement in future strategies to better reflect sectoral needs and priorities. Among those respondents that rated the relevance moderate or weak, some indicated that the strategy did not include their sectoral priorities at all; and others were excluded entirely from the creation process, as they do not provide e-government services to the citizens directly.

Figure 3.3. Relevance of national digital government strategy to Türkiye public sector institutions

Note: Based on the responses of 85 institutions excluding 28 who didn’t answer.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q1.1.2.

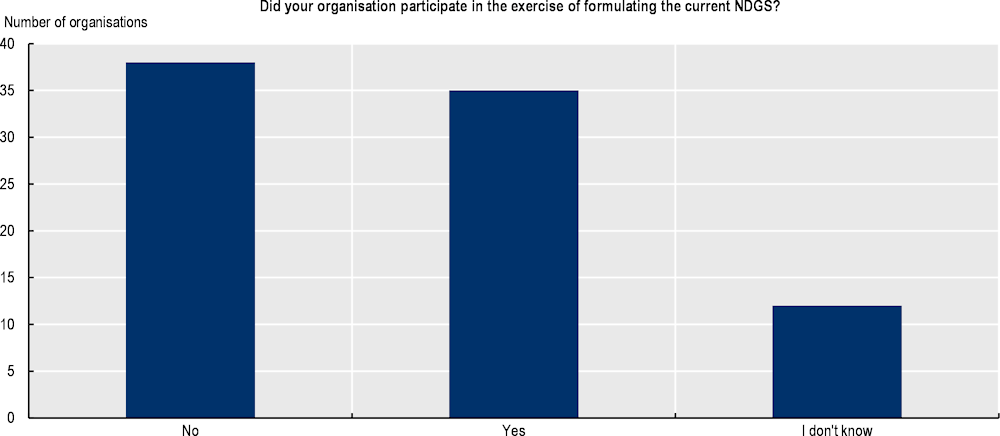

Despite the fact-finding mission surfacing very little criticism of the central leadership and a general attitude of support and compliance with directions and priorities given by the Digital Transformation Office (Dijital Dönüşüm Ofisi, DTO), the survey results indicate not only the need of a more participatory process, but also institutional memory to ensure continuity. Only 31% (35 out of 113) of institutions participated in the formulation of the 2016‑2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan (see Figure 3.4). The other 69% did not acknowledge their involvement in any formal procedure when questioned.

Despite little evidence of having in place a formal procedure to include relevant stakeholders, the former strategy was developed with the participation of stakeholders at every stage. It included face to face interviews with over 2 000 citizens, a survey of almost 500 local government units, questionnaires completed by 72 central government units and 64 universities as well as an internet survey of almost 1 000 private sector representatives. It is to be hoped that the new strategy will build on these previous efforts by responding to the feedback gathered during the Review that indicated the benefit of investing more time with organisations on a sectoral basis as well as incorporating the municipal perspective.

The absence of a digital government strategy setting a broader strategic vision and defining a comprehensive action plan to facilitate the transformation from e-government to digital government appears to be a pressing challenge from a governance perspective. The Turkish government has taken action to address this obstacle. The DTO is responsible for the country’s digital roadmap and currently preparing a new national digital government strategy for which the recommendations of this review will provide a supportive input. The DTO has an excellent opportunity to set out an ambitious vision and clear priorities that respond to specific institutional needs in order to achieve this transition fully. For instance, this review process provided multiple opportunities for public institutions to voice their concerns and priorities. One hundred and thirteen public institutions responded to the Digital Government Survey, many of whom also participated in the fact-finding interviews. In May 2022, the DTO and the OECD review team organised two full-day workshops in Ankara focusing on Service Design and Delivery and the Data-Driven Public Sector with representatives from around 50 public institutions. During the workshops, participants identified common challenges and obstacles and prioritised them.

Figure 3.4. Participation of the public sector institutions in the formulation of the National Digital Government Strategy (NDGS)

Note: Based on the responses of 85 institutions excluding 28 who didn’t answer.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q1.1.5.

The forthcoming strategy needs to align with the National Development Plan, other sectoral and thematic strategies such as the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2021-2025 to ensure coherence and support from the wider public sector (Ministry of Industry and Technology/Digital Transformation Office, 2021[10]). Furthermore, an accompanying long-term investment plan and detailed action plan will ensure continuity, effectiveness and efficiency in the implementation of such a strategy. The detailed action plan outlining responsible bodies, the timeline for the expected results and key performance indicators will also strengthen implementation efforts and impact. Most importantly, all relevant stakeholders need to be included in this process so that their vision and needs feed into the national strategy. The “Mitigation of Bureaucracy and Digital Türkiye Meeting” can be used to bring all necessary public institutions together not only at the formulation stage, but also through regular co-ordination after the development of the strategy. This will ensure monitoring of the implementation and progress made through the strategy.

Digital leadership at the institutional level

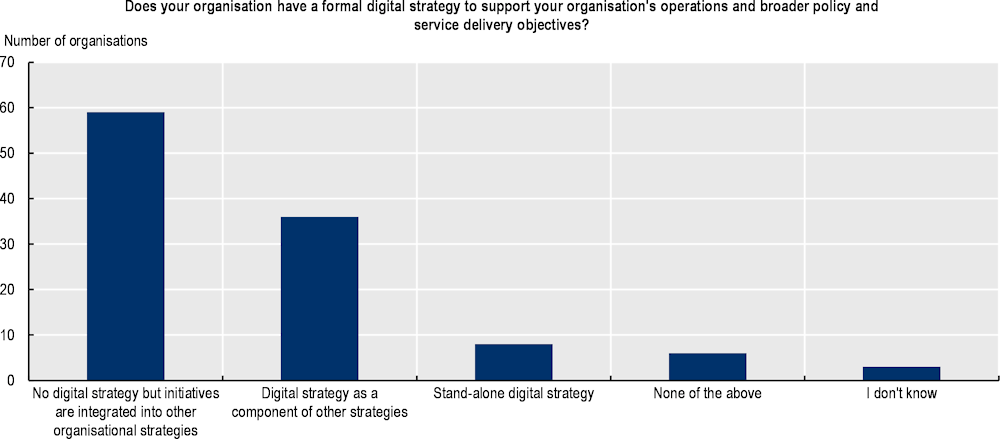

The right leadership at the institutional level can also empower organisations to be proactive in establishing a clear vision at the institutional level, in line with shared overarching strategic priorities for the whole government. Although there is felt to be a clear vision from the Presidency, this clarity has not translated into organisational strategies. Figure 3.5 shows that only 7% of organisations (8/112) have a stand-alone digital strategy and 32% (36/112) have a digital strategy integrated as a component of other strategies. However, 53% of organisations (59/112) have no digital strategy with their digital initiatives being integrated into operational planning. This means 61% (69/112) organisations do not formally have an organisational digital government strategy. The absence of such institutional leadership seems to hinder progress towards digital maturity for many organisations in the Turkish public sector.

Figure 3.5. The presence of formal digital strategies to support organisational policy and service objectives

Note: Based on the responses of 112 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q. 1.2.1.

Nevertheless, the OECD review team identified high levels of digitisation and e-government practice across the public sector. Many of the interviewed organisations clearly understand the importance of digital transformation and has necessary human resources and capacity to adopt new technologies and techniques. A strategic vision and institutional priorities will help institutions transform the underlying human resource management, working methods, culture and mindset, bringing the Turkish public sector closer to digital government maturity, and shifting from digitisation to digitalisation. It is recommended for the DTO to develop a standardised template for institutional strategies to help co-ordinate and support their alignment with the national digital government strategy and other institutions. Furthermore, strengthening digital leadership in each institution through capacity building, and the adoption of common job profiles, will allow institutions to reach their fullest potential in accelerating the public sector digital transformation.

Management tools and financial mechanisms

Governments can optimise efficiency and eliminate duplication of efforts and expenditures through coherent investment in digital technologies and the use of common management tools across the public sector. The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) highlights the importance of clear business cases, agile project management, and strategic procurement of digital technologies. These policy levers facilitate policy implementation aligned with the digital government strategy and sustainability of digital initiatives.

The OECD Digital Government Index 2019 highlighted that top performing OECD countries have developed standardised policy levers across public sector organisations. These allowed them to implement digital projects in a coherent and cohesive manner (Table 3.1). This review has found that these policy levers are missing or in need of further development in Türkiye.

Strategic and coherent investment can further ensure sustainable digital transformation. Among other policy levers, a standardised business case methodology can help the government articulate the value proposition of digital projects, and investments more broadly, and enable the use of ICT and emerging technologies in a cohesive and transparent manner across the public sector. Then, agile project management and commissioning can bring economic and social outcomes efficiently together with private sector stakeholders.

Table 3.1. Use of standardised policy levers at the central/federal government level

|

Business cases |

ICT procurement |

ICT project management |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Belgium |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Canada |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Chile |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

Colombia |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Czech Republic |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

Denmark |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Estonia |

■ |

□ |

□ |

|

Finland |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

France |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Germany |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Greece |

□ |

□ |

■ |

|

Iceland |

□ |

□ |

■ |

|

Ireland |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

Israel |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Italy |

□ |

■ |

□ |

|

Japan |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Korea |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Latvia |

□ |

□ |

□ |

|

Lithuania |

□ |

■ |

□ |

|

Luxembourg |

■ |

□ |

■ |

|

Netherlands |

□ |

■ |

■ |

|

New Zealand |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Norway |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Portugal |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Slovenia |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Spain |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

Sweden |

■ |

■ |

□ |

|

United Kingdom |

■ |

■ |

■ |

|

OECD Total |

|||

|

Yes ■ |

17 |

22 |

20 |

|

No □ |

11 |

6 |

8 |

Note: Data are not available for Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States.

Source: OECD (2020[3]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

As a general approach, it would be highly recommended for the Turkish government to standardise and strengthen the levers mentioned above through, but not limited to, bench learning from good practices of international peers and capacity-building activities among the Turkish public sector institutions. This would also contribute to reinforcing co-ordination and compliance. The following sub-sections touch upon each lever, across the different sectors and levels of government.

Business cases

A business case can help governments optimise the benefits of their investments in digital transformation. A business case is a mechanism used to justify and argue for a project or initiative. It captures the purpose, cost, benefits, risks and intent of a proposed investment. A business case helps government to better plan, execute and monitor digital government financing and investments to create public value and mitigate risks. The 9th principle of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies clearly states that governments should develop clear business cases to sustain the funding and focused implementation of digital technologies projects (OECD, 2014[1]). In line with the Recommendation, the OECD Working Group of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) developed a Business Case Playbook through a thematic group of several OECD member and non-member countries. The playbook introduces ten principles (called Plays) (see Box 3.2) that governments can apply to their business case model building on different governments' experience (Digital Transformation Agency, 2020[11]).

Box 3.2. The OECD Business Case Playbook

The OECD Business Case Playbook, developed with the OECD E-Leaders Thematic Group on Business Cases under the leadership of Australia’s Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), covers the following three groups of principles: 1) governance (establish a common language; make mandatory rules and guidelines; enforce the usage of the business case; ensure value of the business case); 2) costs (ensure a clear scope of the business case; identify potential risks and their consequences; include uncertainties or bandwidths in the economic estimations); and 3) benefits (be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and time-bound; distinguish between financial and non-financial benefits; distinguish between societal, public sectorial and institutional benefits).

10 Principles (plays) of the Playbook

Discovery

1. Understand the problem.

2. Explore options.

3. Engage stakeholders early and often.

Foundations

4. Scope the preliminary work.

5. Establish your team.

6. Engage your sponsors.

Test

7. Define options.

8. Select your preferred solution.

Iterate

9. Draft the business case.

10. Review and refresh.

Note: The OECD Business Case Playbook was last modified in 2020.

Source: Digital Transformation Agency (2020[11]), Business Case Playbook, https://www.dta.gov.au/resources/OECD-Business-Case-Playbook.

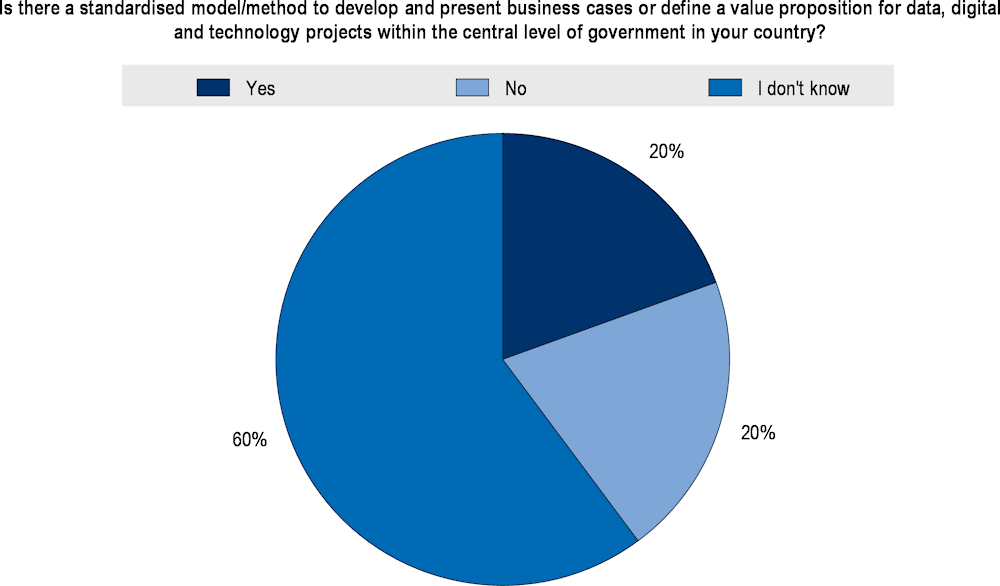

Currently, the Turkish government lacks a standardised business case model at the central government level and general understanding of it across the public sector. The survey showed that when asked about the use of a standardised model/method, an overall majority indicated no or that they are not aware (20% and 60%) (see Figure 3.6). Even among institutions that answered "yes" they indicated using various methods from different sources.

Figure 3.6. Use of a standardised business case in the Turkish public sector

Note: Based on the responses of 113 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q. 1.5.3.

The DTO is working on the development of a standardised model with basic categories (OECD, 2021[12]). A business case can be different forms with different structure depending on the country specific characteristics or even the size and nature of certain projects. Nevertheless, it should clearly describing the problem the project is trying to address, consider diverse ways to solve it and recommend the most suitable solution. It is also highly recommended for the DTO to engage key stakeholders in the process of designing the business model/methodology. Higher and active engagement will help promoting shared ownership, distributing benefits and better understanding the users’ needs.

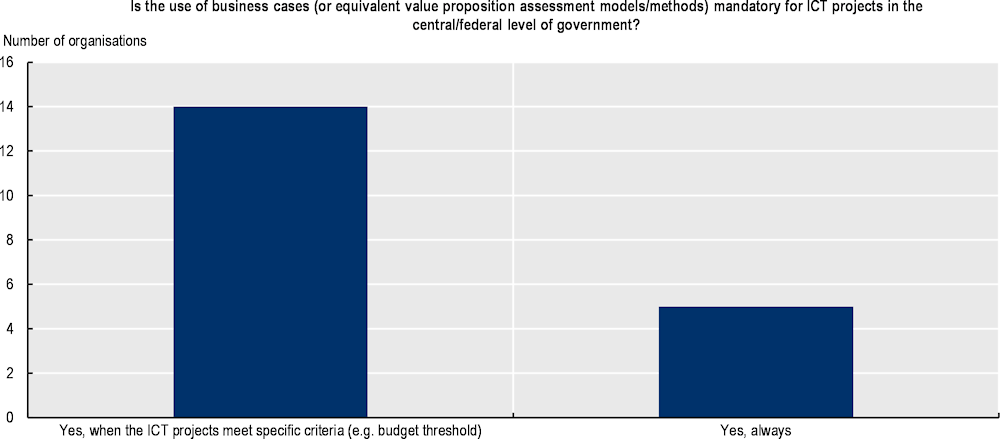

According to the OECD Digital Government Index 2019 (OECD, 2020[3]), 18 out of 33 responding governments indicated that they made the use of business cases mandatory for all ICT projects or those that meet certain criteria (see Figure 3.7). For example, in the case of Denmark, business case models are mandatory for ICT projects especially those exceeding the budget of EUR 1.35 million (European euros) to ensure project success (see Box 3.3). The governments involved different stakeholder groups in defining business case models: 1) public sector organisations, 2) public servants, 3) academia, 4) private sector organisations, 5) civil society organisations and 6) citizens.

In addition to further developing the centralised model associated with the Public Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) Project Preparation Guide2 (Ministry of Development, 2017[13]; Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2021[14]), the government would benefit from raising the awareness and understanding of the value of applying a common business case methodology and practice across the public sector through inter-ministerial co‑ordination, communication campaign and regular training exercises for financing and investing project managers. It would be feasible to achieve high adoption rate from the public sector once relevant stakeholders understand that a standardised business case methodology can help the government articulate the value proposition of digital projects, and enable the use of ICT and emerging technologies in a cohesive and transparent manner.

Figure 3.7. Mandatory use of business cases for ICT projects in the responding countries

Note: Based on the responses of 19 countries that use business cases.

Source: OECD (2020[3]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en, Q. 75a.

Box 3.3. Mandatory use of business case models in Denmark

Denmark’s joint-governance IT project and programme and business case models are mandatory to ensure project success especially for those with more than EUR 1.35 million budget. It is intended to justify if the IT project is a good investment, based on a calculation of the overall financial and non‑financial consequences of a potential investment in an IT project or programme. It involves an analysis and statement of change desires and the approach taken to achieve it.

Source: OECD (2021[2]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

Agile Project Management

The 10th principle of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) underlines that project management approaches are crucial in achieving digital government maturity. Project management tools reinforce institutional capacities to manage, monitor and ensure consistency in project implementation. Then added agility in project management allows governments to quickly seized opportunities, mitigate risks, and make necessary changes.

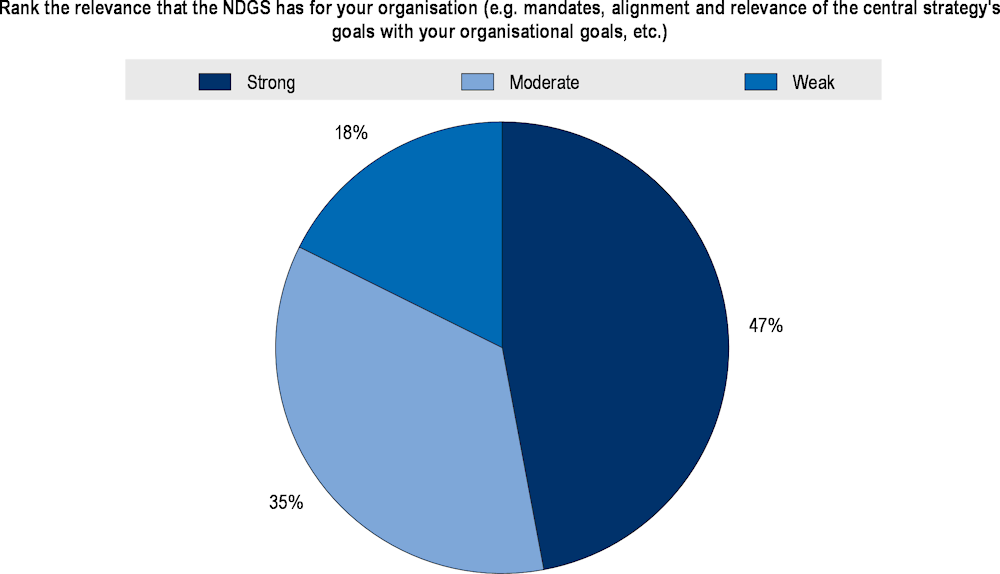

Agile project management enables efficient and effective design and implementation of digital government projects including services. The traditional “waterfall” approach sets our requirements in the initial stage and tries to manage possible future risks through planning. Until the delivery of final product, there is no opportunity to assess, intervene and feed back in the product. On the other hand, agile project management bases on a continuous cycle of diagnosis, feedback and iteration (see Figure 3.8). Through ongoing research and experiments, governments can apply insights from user experience and adjust the course of the project quickly for optimal outcomes (Welby and Hui Yan Tan, 2022[15]). Adopting a standardised agile project management approach can help governments forecast capacities across the public sector and enhance accountability and transparency in digital government implementation. The results of the OECD Digital Government Index 2019 (OECD, 2020[3]) show that governments put great emphasis on applying a standardised model for project management. Twenty-two out of 33 participating countries have a standardised model (see Box 3.4).

Figure 3.8. An Agile approach to the interaction between government and the public during policymaking, service delivery and ongoing operations

Box 3.4. Good practices of the OECD member countries

The UK’s Digital, Data and Technology Functional Standard (DDaT Functional Standard)

The United Kingdom’s Digital, Data and Technology functional standard sets out how all digital, data and technology work and activities should be conducted across government, ensuring:

The public is provided with appropriate digital services.

Those leading government organisations can provide strategic direction and governance that enable operational excellence.

Those working in government organisations can use and implement tools and infrastructure to meet their objectives.

The standard contains 7 main elements:

1. The purpose and scope of the standard.

2. Principles, covering the fundamental tenets of digital, data and technology including aligning with government policy, and meeting clearly identified user needs, delivery teams comprising multiple disciplinary teams, meeting security and privacy requirements and using open standard.

3. A definition of digital data and technology.

4. Governance which sets out governance structures and mechanisms for government, departments, teams, projects and programmes.

5. Delivering digital services and technology which outlines the stages of agile delivery, including design, implementation, maintenance and sets out in more detail how digital and technology interoperate.

6. Managing live services and technology which explains how you should look at the full life cycle of a services and/or technology, including iteration, transition and decommissioning.

7. People and skills which covers both DDaT professions and non-specialist staff.

Denmark

Denmark’s Agency of Digitalisation has a cross-governmental ICT project management model to harmonise the management of the ICT projects across the public sector from conceptualisation to realisation of benefits. This model provides a standardised way of managing ICT projects across the government. Based on the Projects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2) methodology, the Danish model provides guidelines for how to organise and manage ICT projects and delivers concrete templates for all generic products in the process. The Ministry of Finance has created a unit to establish good practice on digital government projects that covers mandatory and recommended elements. The model has enabled the establishment of a specific governance structure, for example, requiring approvals of well-developed business cases, as well as ongoing approvals (so called “stop-go” decisions) each time a project passes from one phase to the next.

Source: Welby, B. and E. Hui Yan Tan (2022[15]), “Designing and delivering public services in the digital age”, https://doi.org/10.1787/e056ef99-en; OECD (2021[2]), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en; UK Central Digital and Data Office (2020[17]), Government Functional Standard: GovS 005: Digital, Data and Technology.

The Turkish government does not have a standardised model for digital and ICT project management at the central government level (OECD, 2021[12]). However, the Public ICT Projects Preparation Guide aims to support all public institutions including local governments with the preparation of ICT investment projects. The guideline hopes to deliver cost-benefit analysis, timely completion of projects and establishing an interoperable e-government structure. The guideline also has a set of policies and principles that institutions need to follow in order to be included in the investment programme. It has four enclosed documents: assessment templates, sub-guideline for the templates, checklist, and sub‑guideline specific to investment type.

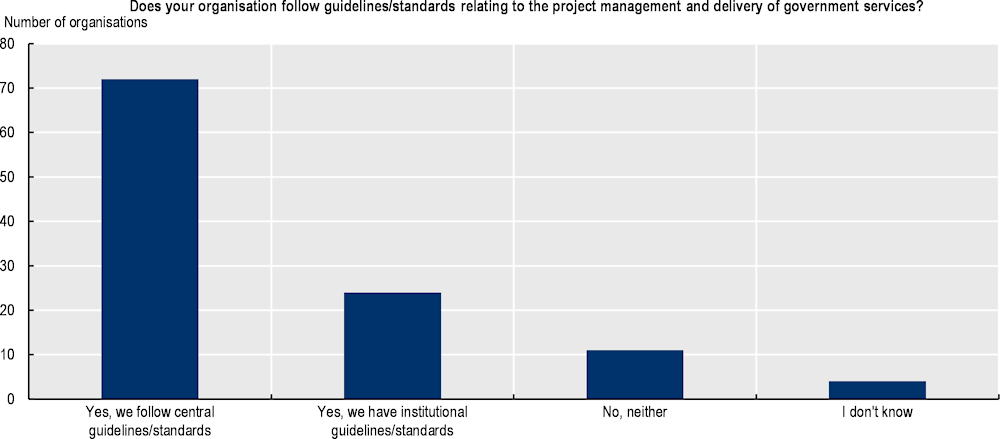

In the survey, the majority of the institutions indicated that they follow the central guidelines/standards, while one-fifth responded that they follow institutional guidelines/standards for project management and delivery of government services (see Figure 3.9). Nevertheless during the fact-finding interviews, institutions did not identify the relevance of this guideline mentioned above or their practice of using such guideline.

Figure 3.9. Guidelines/standards on the project management and delivery of government services in Türkiye

Note: Based on the responses of 111 institutions.

Source: OECD (2021[9]), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris, Q. 3.9.2.

The design of the new digital government strategy provides an important opportunity to update the guideline towards a standardised agile project management model, which can better promote the aligned, participatory and accessible development of digital government projects and services across the public sector. It would be important to involve all relevant stakeholders in the process and especially the institutions that have been applying their own project management approaches to create shared ownership of the standardised model.

Procurement of ICT/Digital Technologies

Governments with a robust procurement strategy can manage ICT/digital investments with more agility based on their digital government policy objectives. Public procurement practices should be efficient and effective in prioritising investments and resources for key policy areas such as digitalisation. Traditional public procurement follows a sequence of needs assessment, market research, tender process, payment, contract management and then the delivery of goods and services (OECD, 2015[18]). With regards to the procurement of ICT/digital technologies, governments need to take specific approaches to achieve valuable and quality acquisitions in a timely manner.

The 11th principle of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]) underlines the need for the procurement of digital technologies based on an assessment of “existing assets including digital skills, job profiles, technologies, contracts, inter-agency agreements to increase efficiency, support innovation, and best sustain objectives stated in the overall public sector modernisation agenda. Procurement and contracting rules should be updated, as appropriate, to make them compatible with modern ways of developing and deploying digital technology”. In line with the Recommendation, OECD member countries have started to consider more innovative and flexible approaches to procure ICT/digital technologies and services (OECD, 2022[19]).

The OECD Working Party of Senior Digital Government Officials (E-Leaders) worked on the development of the ICT Commissioning Playbook, building on experiences of OECD member and partner countries. The Playbook explains how governments can take an agile procurement approach. It provides eleven actions such as better understanding user needs, ensuring procurement transparency, and sharing and reusing components and good practices of others (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. The ICT Commissioning Playbook

The ICT Commissioning Playbook is focusing on ICT procurement reform and its role in the wider digital transformation of the public sector in countries around the world. Its goal is to show how traditional procurement can evolve towards agile procurement. The Playbook sets out how to address the main issues faced by governments and explores what works and what does not work, sharing real life examples. The Playbook provides a set of actionable guidelines (known as plays) that countries can follow to move towards more agile approaches for ICT procurements.

Eleven plays are:

8. Set the context.

9. Start by understanding user needs.

10. Design procurements and contracts that meet users’ needs.

11. Be agile, iterative and incremental.

12. Work as a multidisciplinary team from the beginning.

13. Make things open.

14. Build trusting and collaborative relationships, internally and external.

15. Share what you have with others and reuse what others have.

16. Move away from specifying to regulating.

17. Public procurement for public good.

18. Operate.

The plays outline ways to overcome common problems, alongside case studies that demonstrate challenges and successes. The Playbook was developed for procurement professionals in the public sector and is based on the experiences of the UK, with contributions from Australia, Canada, Chile, Finland, Mexico, New Zealand, Portugal, Uruguay and the United States.

Source: OECD (2022[19]), Towards Agile ICT Procurement in the Slovak Republic: Good Practices and Recommendations, https://doi.org/10.1787/b0a5d50f-en.

In the case of Türkiye, there is not a central strategy dedicated to public procurement of ICT goods and services; however, the Public Procurement Law No. 4734 covers ICT procurement (Government of the Republic of Türkiye, 2002[20]). In addition, on the survey question about a formal central guideline for the public procurement of ICT/digital goods and services, the DTO indicated that the Public ICT Projects Preparation Guide serves as such a document (OECD, 2021[12]). Nevertheless, the procurement law and the abovementioned guideline leave much to be desired to sufficiently govern fast-changing, complex ICT/digital procurement. Further clarity can be given to the relevant actors on the co-ordination mechanism and process specifically for ICT/digital procurement.

Similar to the assessment on two previous policy levers, Türkiye can greatly benefit from taking a number of actions. Establishing the appropriate governance framework for ICT/digital procurement best suited for its national circumstances can bring accountability, transparency and trust from public institutions. Updating the current procurement law to better reflect changes could enable the government to incorporate new and emerging technologies across the public sector strategically, safely and effectively. Last, a dedicated ICT/digital procurement strategy and process jointly developed with relevant stakeholders including the private sector and civil society will enable a procurement practice based on government-wide comprehensive priorities and user needs.

Financial measures and mechanisms

Financial management mechanisms provide governments with another set of policy tools for implementation of the digital government strategy and action plan. Governments can leverage institutional frameworks for allocation of digital investment to align and ensure implementation of digital projects across the public sector and consistently with the main overall strategic objectives of the government. It is crucial for the organisation-in-charge to take an active role in setting national budget priorities to guarantee the coherent and sustainable digital transformation across different sectors.

Governments can make use of policy tools such as budget threshold and co-funding to plan and operationalise digital investments. A budget threshold can help to manage internal processes, ensuring that major digital projects above a certain financial value are aligned with the digital government strategy and creating a transparent and clear process across the public sector. Co-funding mechanisms led by the leading organisation can support coherent and efficient policy implementation and assure the dissemination of standards and key enablers across the public sector. The mechanisms can support digital government projects that are aligned to the national digital priorities in different sectors and levels of governments. During the review process, the institutions also highlighted possible opportunities that the mechanisms can bring in securing financial and human resources in the Turkish public sector.

In Türkiye, the Ministry of Treasury and Finance (Hazine ve Maliye Bakanlığı) annually prepares the Medium Term Programme (MTP) each year together with the Presidency of Strategy and Budget. The MTP, a main budgetary policy document, sets the objectives and priorities. Based on this document along with the yearly Presidential Annual Programme, the annual budget is allocated to each organisation. All public sector organisations need to fully comply with the objectives and priorities stated in the MTP when preparing their budgets and making policy decisions (Ministry of Treasury and Finance, 2022[21]). This process is supported by the Public Investment Information System (Kamu Yatırımları Bilgi Sistemi, KaYa). Although the DTO is the leading public sector organisation mandated to develop Türkiye's digital roadmap, the DTO does not play an active role in shaping the MTP or hold formal decision-making power over the budgeting for digital projects at the central level. In the case of Portugal, the Administrative Modernisation Agency (AMA) has the approval power for ICT and digital projects with a budget of EUR 10 000 or more. The AMA tries to ensure the best value for money by reviewing compliance with guidelines and the non‑duplication of efforts (OECD, 2021[2]).

In general, Türkiye needs to institutionalise financial measures and mechanisms to better forecast digital investment and strategically allocate them with a holistic point-of-view. The budgetary process, implemented by the Ministry of Treasury and Finance and supported by the ministry’s Integrated Public Financial Management Information System of Türkiye, can use more clarity and transparency. Moreover, Türkiye seems to be missing budget threshold and co-funding mechanism for digital projects. The government can consider devising a formal financial management mechanism along with an investment plan to support the implementation of the forthcoming national digital government strategy in co-ordination with relevant stakeholders including the Ministry of Treasury and Finance. Such investment plan could help the government to prioritise projects, estimate the spending and execute accordingly. Additionally, it would be worthwhile to consider a funding model that can empower the DTO to co-fund or delegate funds to key priority projects that are cross-sectoral to ensure timely and efficient implementation of such projects.

Regulations and standards

The legal and regulatory framework underpins governance arrangements, mechanisms, policy actions and measures for digital government. These binding and non-binding tools guide the planning, implementation and monitoring of digital government strategies. The importance of the legal and regulatory framework is highlighted in the 12th principle of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies (OECD, 2014[1]). It calls for “general and sector-specific legal and regulatory frameworks [that] allow digital opportunities to be seized by reviewing them as appropriate; and including assessment of the implications of new legislations on governments’ digital needs as part of the regulatory impact assessment process”. In today's fast-changing digital age, governments need to have in place the legal and regulatory framework that harnesses digital opportunities and addresses potential risks while circumventing bureaucratic resistance to digital transformation.

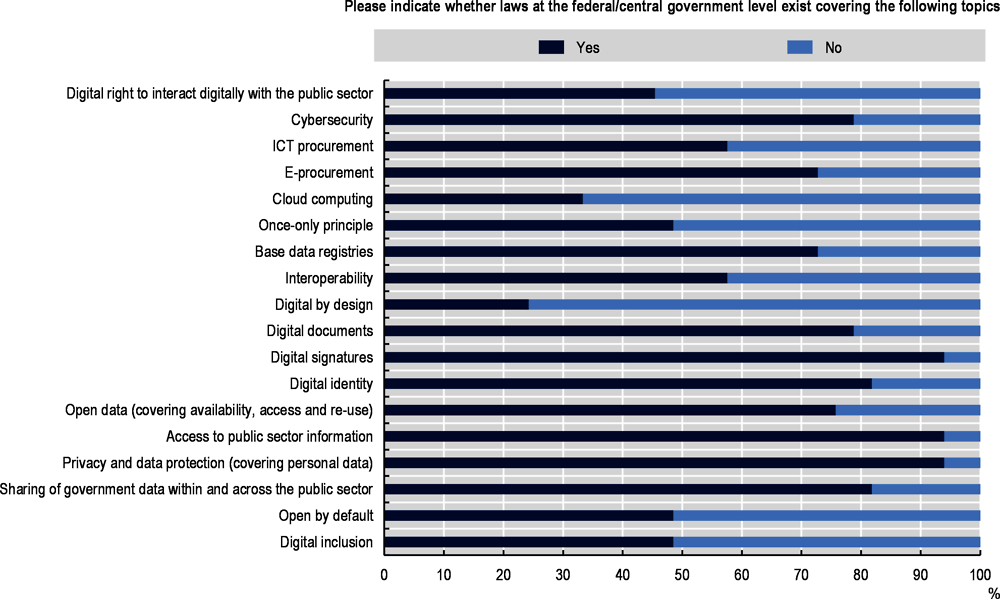

The OECD Digital Government Index 2019 paints a good overview of the existing legal and regulatory framework for digital government in the OECD member and partner countries (OECD, 2020[3]). Most of the participating countries have legislation on key enablers such as digital signatures (93%), digital identity (82%), digital documents (79%), and open government data (76%). On the other hand, legislation on emerging areas like cloud computing or digital by design are still not commonly in place (see Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10. Overview of the existing legal and regulatory framework for digital government in the OECD member and partner countries

Note: The OECD countries that did not take part in the Digital Government Index are: Australia, Hungary, Mexico, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Switzerland, Türkiye and the United States. A total of 29 OECD countries and 19 European Union countries participated in the Digital Government Index. Information on data for Israel is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932315602.

Source: OECD (2020[3]), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en, Q. 92.

In Türkiye, several specific pieces of legislation and regulation support various aspects of digital transformation of the public sector at different capacities. Most notably, two presidential decrees (No.1 and No.48) cover the governance responsibilities and role of relevant government bodies (Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2018[22]; Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, 2019[23]). In addition, a series of legal and regulatory documents (see Box 3.6) provide legal basis in areas such as interoperability, key enablers (access to public information, electronic identification (eID) and trust services, security, interconnection of base registries, e‑procurement), and emerging technologies (EC, 2021[8]). However, the regulatory frameworks in Türkiye can be further updated and aligned to cover all digital government areas comprehensively. The survey to support this review indicated that 96% of organisations (108/113) believe there to be potential for improving the legal and regulatory framework.3 The rationales included the necessity to update or adjust the current legal and regulatory framework to reflect a concrete mandate for each institution, facilitate the use of new technologies and risk mitigation; and to equip the public sector adequately for a constantly transforming environment. The government has started strengthening the legal and regulatory framework in certain areas. For instance, the recent amendment to the Public Procurement Law would provide a stronger legal foundation for digitalisation of procurement process.

Box 3.6. Key Digital Public Administration Legislation of Türkiye

1. Specific legislation on digital public administration

eGovernment Legislation

Regulation on the Procedures and Principles Regarding the Execution of e-Government Services.

2. Interoperability

Circular No. 2009/4 on Interoperability Principles in Public Information Systems.

3. Key enablers

4. Access to public information

Freedom of Information Legislation: Right to Information Act (Law No. 4982)

Regulation on Principles and Procedures Regarding the Implementation of the Right to Information Law.

5. Electronic identification (eID) and Trust Services

Regulation on the Turkish National Identity Card

Regulation on Remote Identification Methods to be Used by Banks and Establishment of Contractual Relationship in Electronic Environment

By-Law on the Procedures and Principles Pertaining to the Implementation of the Electronic Signature Law

Regulation on Electronic Identity Verification System for Republic of Türkiye Identity Card

Law No. 5070 on Electronic Signatures

Law No. 5809 on Electronic Communications

Regulation Regarding Electronic Notification.

6. Security aspects

Law No. 6698 on Personal Data Protection Law

Law No. 5809 on Electronic Communications

Presidential Circular on Information Security Measures 2019/12

By-Law on Network and Information Security in the Electronic Communications Sector

Sector-specific Regulations for Cyber Security in Critical Infrastructure Sectors

Adaptation of Information Security and Cyber Security Standards.

7. Interconnection of base registries

Regulation regarding the Principles of Implementation of the Integrated Public Financial Management Information System

Regulation regarding the Data Sharing of the Land Registry and Cadastre (Tapu ve Kadastro Genel Müdürlüğü, TKGM)

By-Law on the Procedures for the Provision of Public Services

By-Law on the Identity Registry System Sharing.

8. eProcurement

Regulation on Electronic Procurement Implementation

Public Procurement Law No. 4734

By-Law on Competency of Contractors for Government IT Projects.

9. Emerging technologies

By-Law on the Internet of Things Security.

Source: EC (2021[8]), Digital Public Administration Factsheet 2021 - Turkey, https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/DPA_Factsheets_2021_Turkey_vFinal.pdf; Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2022[24]), Regulatory Information System, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

The Turkish government can consider consolidating several existing legislations to streamline and make the legal and regulatory framework more comprehensive in covering all areas of digital government. In addition, it can also conduct mapping exercises to identify areas that can be included, updated or further advanced within the framework, so that the framework does not hinder the transformation efforts of the country. This process should include all relevant users to ensure that the framework reflects users’ needs.

A similar recommendation can be applied to strengthening common approaches or standards for services, data, quality or performance (as will be discussed further in Chapters 5, 6 and 7). Despite the institutional competencies and effectiveness detected during the fact-finding mission and two-day workshop, the lack of common enablers limits the effectiveness of the administration in terms of achieving a coherent and sustainable transformation of the public sector as a whole. Building a broad consensus and appetite to see the further development of such policy levers among institutions, the government can identify priority areas for standardisation in the forthcoming strategy along with a detailed action plan. The DTO can take into consideration challenges and solutions identified and prioritised by the public sector institutions that participate in the workshops in the process.

References

[11] Digital Transformation Agency (2020), Business Case Playbook, Australian Government, https://www.dta.gov.au/resources/OECD-Business-Case-Playbook.

[8] EC (2021), Digital Public Administration Factsheet 2021 - Turkey, European Commission, https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/inline-files/DPA_Factsheets_2021_Turkey_vFinal.pdf.

[20] Government of the Republic of Türkiye (2002), Public Procurement Law, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/mevzuat?MevzuatNo=4734&MevzuatTur=1&MevzuatTertip=5.

[29] High Planning Council (2005), e-Transformation Türkiye Project 2005 Action Plan, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/Eskiler/2005/04/20050401-12.htm (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[30] KamuNet (PublicNet) Technical Council (2002), Transition to e-Government Action Plan.

[13] Ministry of Development (2017), Kamu Bilgi ve Iletişim Teknolojileri (BIT) Projeleri Hazirlama Rehberi, Republic of Türkiye.

[27] Ministry of Development (2015), 2015-2018 Information Society Strategy and Action Plan, Republic of Türkiye, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2015/03/20150306M1-2.htm (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[10] Ministry of Industry and Technology/Digital Transformation Office (2021), National Artificial Intelligence Strategy (2021-2025), Republic of Türkiye/Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye, https://cbddo.gov.tr/SharedFolderServer/Genel/File/TRNationalAIStrategy2021-2025.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2022).

[6] Ministry of Transport, Maritime Affairs and Communications (2016), 2016-2019 National e-Government Strategy and Action Plan, Republic of Türkiye, http://www.edevlet.gov.tr (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[21] Ministry of Treasury and Finance (2022), Medium Term Programme 2022-2024, Republic of Türkiye, https://www.sbb.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Medium_Term_Programme_2022-2024.pdf.

[19] OECD (2022), Towards Agile ICT Procurement in the Slovak Republic: Good Practices and Recommendations, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b0a5d50f-en.

[12] OECD (2021), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye Lead/Co-ordinating Government Organisation Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[9] OECD (2021), “Digital Government Survey of Türkiye, Public Sector Organisations Version”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[2] OECD (2021), The E-Leaders Handbook on the Governance of Digital Government, OECD Digital Government Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ac7f2531-en.

[3] OECD (2020), “Digital Government Index: 2019 results”, OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, No. 3, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4de9f5bb-en.

[16] OECD (2020), “The conceptual framework”, in Digital Government in Chile – Improving Public Service Design and Delivery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d4498e23-en.

[18] OECD (2015), Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD/LEGAL/0411, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0411.

[1] OECD (2014), Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies, OECD/LEGAL/0406, OECD, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0406.

[14] Presidency of Strategy and Budget (2021), Kamu Bilgi ve Iletişim Teknolojileri (BIT) Projeleri Hazirlama Rehberi (in Turkish).

[7] Presidency of Strategy and Budget (2019), Eleventh Development Plan (2019-2023), Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye.

[24] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2022), Regulatory Information System, General Directorate of Law and Legislation, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/ (accessed on 12 June 2022).

[23] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2019), Presidential Decree No. 48, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2019/10/20191024-1.pdf.

[22] Presidency of the Republic of Türkiye (2018), Presidential Decree No. 1, https://www.mevzuat.gov.tr/MevzuatMetin/19.5.1.pdf.

[28] Prime Minister of Türkiye (2003), e-Transformation Türkiye Project 2003-2004 Short Term Action Plan, Circular of Prime Ministry no. 2003/48, https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2003/12/20031204.htm#3 (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[25] Prime Minister of Türkiye (2002), e-Türkiye Initiative Action Plan.

[5] Republic of Türkiye (2014), The Tenth Development Plan (2014-2018), https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2013/07/20130706M1-1.htm (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[4] State Planning Organisation (2006), Information Society Strategy and Action Plan (2006-2010).

[26] Türkiye National Information Infrastructure Project Office (1999), Türkiye National Information Infrastructure Master Plan Final Report, http://www.bilgitoplumu.gov.tr/Documents/1/Yayinlar/991000_TuenaRapor.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2022).

[17] UK Central Digital and Data Office (2020), Government Functional Standard GovS 005: Digital, Data and Technology, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/digital-data-and-technology-functional-standard-version-1 (accessed on 30 January 2023).

[15] Welby, B. and E. Hui Yan Tan (2022), “Designing and delivering public services in the digital age”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit Notes, No. 22, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e056ef99-en.

[31] World Bank (1993), Türkiye: Informatics and Economic Modernization, World Bank, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.1596/0-8213-2376-8.

Notes

← 1. Informatics and Economic Modernisation Report (World Bank, 1993[31]), Türkiye National Information Infrastructure Master Plan Final Report (Türkiye National Information Infrastructure Project Office, 1999[26]), Action Plan for Transition to e-Government (KamuNet (PublicNet) Technical Council, 2002[30]), e-Türkiye Initiative Action Plan (Prime Minister of Türkiye, 2002[25]), e-Transformation Türkiye Project 2003‑2004 Short-Term Action Plan, Circular of Prime Ministry no 2003/48 (Prime Minister of Türkiye, 2003[28]), e-Transformation Türkiye Project Action Plan (High Planning Council, 2005[29]), Information Society Strategy and Action Plan (2006-2010) (State Planning Organisation, 2006[4]), Tenth Development Plan (2014-2018) (Republic of Türkiye, 2014[5]), and the 2015-2018 Information Society Strategy and Action Plan (Ministry of Development, 2015[27]).

← 2. The Guide was developed by the Ministry of Development in 2017 (Ministry of Development, 2017[13]). Since the dissolution of the ministry, the Presidency of Strategy and Budget has taken up the responsibility for enforcing the guideline and published a revised version in 2021 (Presidency of Strategy and Budget, 2021[14]).