This chapter examines waste management and Israel's shift towards a circular economy. It looks first at its record of achieving recycling and resource productivity targets, including municipal waste generation, treatment and disposal, and material flow and resource productivity. After reviewing the division of responsibilities and the role of local authorities at the institutional level, the chapter analyses the legislative framework and regulations for waste handling and treatment. It ends with a review of Israel's planning, pricing and other policies towards a circular economy. This covers economic instruments to reduce waste production and landfilling; circular economy as a pillar of climate mitigation policy; the move towards circular procurement; and the need to engage stakeholders and increase transparency.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Israel 2023

Chapter 2. Waste management and circular economy

Abstract

2.1. Introduction

Israel is a small, densely populated and highly urbanised country. It has seen economic and population growth since 2000, which has intensified pressures on the environment, increased demand for goods and services, and produced high levels of waste. Within the last ten years, municipal solid waste (MSW) levels have continued growing, while the share of MSW destined for landfill (around 80%) has remained stable. This situation prompted the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MoEP) to prioritise waste management and a circular economy with the aspiration of “zero waste” by 2050. As part of the shift from a linear economy, the MoEP aimed to engage municipalities, raise awareness across stakeholders to reduce single-use plastics, fight illegal dumping and burning of waste, and set up economic, regulatory and governance tools for modern waste management.

The MoEP has taken a number of key steps to advance this agenda. These include developing a Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy as a basis for a circular economy strategy; establishing a tax on certain single-use items; broadening the deposit refund scheme (DRS); adopting a Packaging Law; and setting up a Cleanliness Fund to bridge the waste treatment infrastructure gap. However, a clear legislative framework for waste management and an agenda for a circular economy have yet to be set.

To date, the government has focused on improving waste management, while “circular economy” remains an incipient concept. There is room to broaden Israel’s policy vision to leverage the full potential of a circular economy. This could range from preventing waste generation and keeping materials in use for as long as possible to transforming waste into resources. Strengthening the role of municipalities will be key to achieving recycling targets and applying circular economy principles to areas such as food systems and the built environment. Fiscal policy tools, such as taxes and landfill levies and a tax on virgin construction aggregates, will be needed to set incentives and change behaviours. Education and awareness raising will also play an important role in prompting behavioural changes in citizens and businesses.

2.2. Achieving recycling and resource productivity targets

2.2.1. Municipal waste generation, treatment and disposal

Israel has one of the highest levels of municipal waste generation per capita among OECD member countries. Households produce 80% of waste with the rest generated by the commercial institutional sector.1 This level has been consistently growing for the past 20 years. In 2020, Israel generated 6 million tonnes (Mt) of MSW, approximately 0.3 Mt more than in 2018. MSW per capita amounted to 691 kg per capita in 2020, well above the OECD average of 534. Between 2010 and 2020, MSW grew at a rate of 2.6% per year, of which 1.9% can be attributed to population growth and 0.7% to increased waste production per person. In a business-as-usual scenario, MSW generation is expected to continue growing at a rate of 2.4% per year, reaching 6.6 Mt in 2025 and almost 7.5 Mt in 2030.

Construction and demolition (C&D) waste was by far the largest contributor (63%) to total waste of the five sectors with available data in 2020 (mining and quarrying; manufacturing industries; energy production; water supply, sewerage, waste management; and construction). More than one-third (68%) of total treated C&D waste was recycled in 2020, its volume more than doubling from 1 711 Mt in 2010 to 3 789 Mt in 2020. Manufacturing industries are the second largest contributor to total waste (2 522 Mt). Non-metallic mineral products are the main contributor to this waste stream (875 Mt), much of which is attributable to the manufacturing of construction materials.

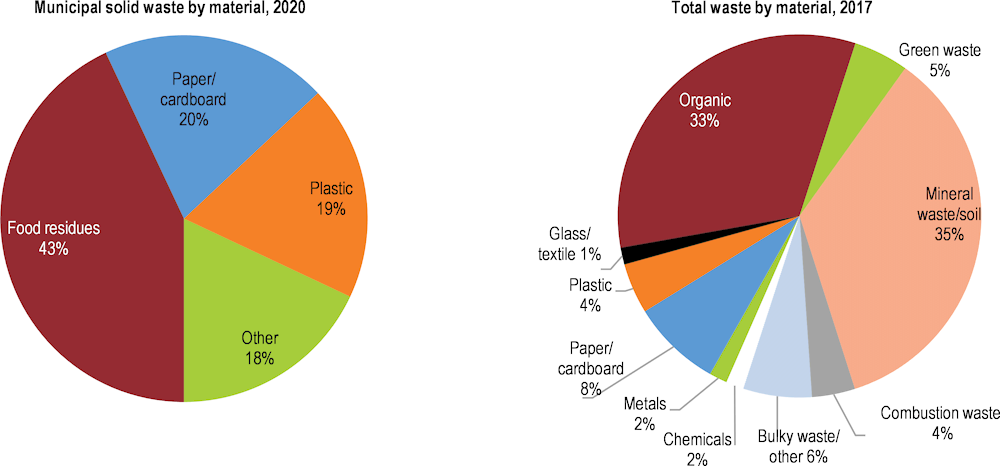

Biodegradable waste (bio-waste), in particular food waste and loss, accounts for a significant share of both MSW and total waste in Israel (Figure 2.1). An average Israeli family throws away ILS 3 600 worth of food per year. This is equivalent to 13% of average household food expenditure and 1.5 months of food consumption. Overbuying (i.e. buying more food than needed) in turn generates excessive food preparation, which is a key source of household food waste.

In 2020, Israel generated 2.5 Mt of food waste (by consumers) and loss (between harvest and retail), worth ILS 20.3 billion. The volume of food waste corresponded to about 35% of overall domestic food production (Leket Israel, 2021). This is in line with the global estimate of one-third of the food produced in the world for human consumption being lost or wasted (FAO, 2013). The total environmental cost of food waste in the country is estimated at ILS 3.4 billion. This amount breaks down further into ILS 1.4 billion from the impact on natural resources (water and land); ILS 1.27 billion from damage from emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) and air pollutants; and ILS 0.8 billion from waste treatment (Leket Israel, 2021). Food waste alone is responsible for 6% of the country’s GHG emissions.

Figure 2.1. Bio-waste is the largest contributor to total and municipal waste in Israel

Note: Total waste: data calculated in accordance with the System of Environmental Economic Accounts.

Sources: CBS (2020), Satellite Waste Accounts 2017 (database); country submission.

The separation of waste streams and their collection by households remain low, although Israel has undertaken some initiatives in response to the 2011 EPR recommendation to implement separate collection of dry and organic waste in all municipalities and develop related treatment infrastructure. In 2011, the MoEP started a separation of waste at source programme, backed by financial support to 50 local authorities to establish sorting plants for dry and organic waste. However, the programme ended in 2016.

Also in 2011, the MoEP issued two calls for proposals to local authorities and private developers for the establishment or upgrading of facilities for biodegradable waste. While ILS 350 million was allocated for 29 facilities, including sorting transfer stations and composting and anaerobic digestion facilities, this infrastructure remains incomplete. A MoEP analysis in 2018 highlighted the need to build five waste‑to‑energy facilities in the country, including three by 2030. The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030) foresees economic incentives for waste separation and reduction at source, notably through weight-based charging for households, as well as energy recovery from residual waste.

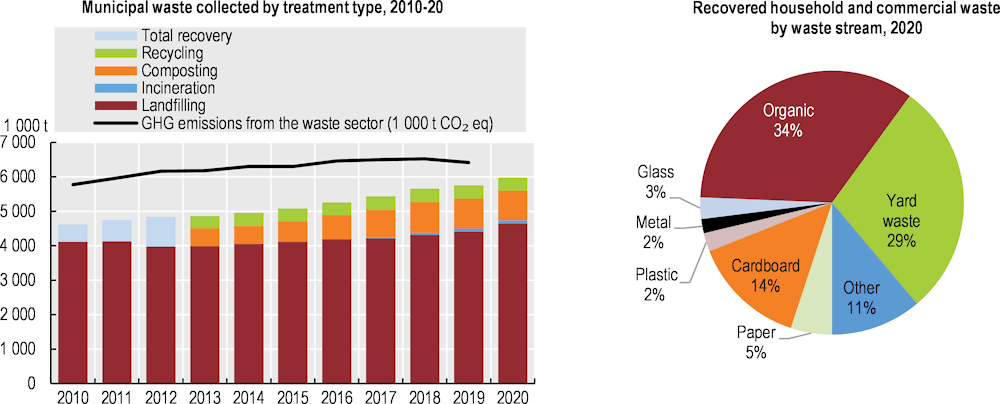

Landfilling has remained the primary form of waste treatment in Israel (MoEP, 2020b) despite the limited availability of land. In 2020, 77% of MSW was landfilled, one of the highest rates in the OECD. Each year, around 3 Mt of unsorted (mixed) waste (especially from municipalities close to a landfill and those that do not have a sorting facility nearby) and 4.5 Mt in total are sent to one of Israel’s 11 landfills. Some landfills are planned for expansion, but there are no plans for additional landfills. It is estimated that the available capacity for landfilling will drop from the current 45 Mt to 16 Mt in 2030. Waste-to-energy processes are starting to be implemented (2% in 2020), and recycling accounted in 2020 for 6.4% of collected municipal waste (excluding composting). Adding composting would bring the share of material recovery to 20.7%.

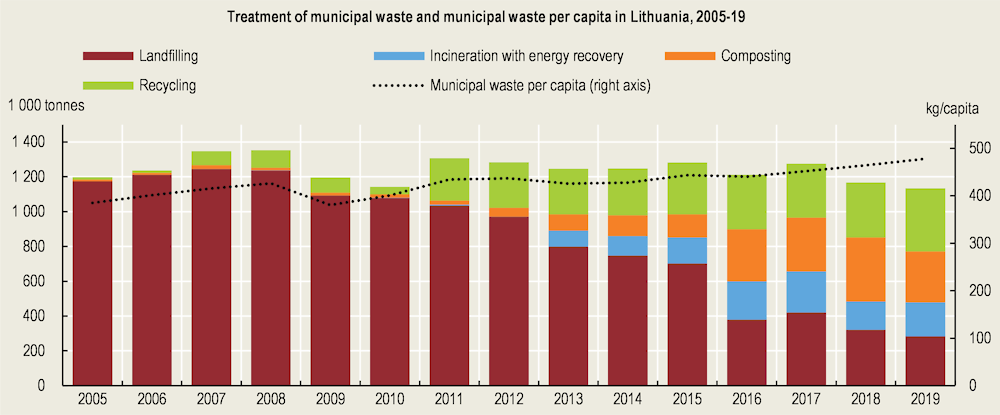

As part of the shift to a circular economy, a significant increase in recycling would help address resource scarcity and reduce the number of landfills required. As an illustration of good practice in this area, Box 2.1 explains how Lithuania has transitioned from previously landfilling almost all its waste to recycling and composting most of it in less than a decade. The experience of Lithuania, which also has the ambition to shift to a circular economy by 2050, can serve as an inspiration for Israel.

Box 2.1. Leapfrogging from landfilling to recycling and composting: The case of Lithuania

Lithuania has moved from landfilling almost all its waste to recycling and composting most of it in less than a decade. This has allowed the country to narrowly meet the targets for recycling half of household waste (paper, metal, plastic and glass) and 70% of construction waste by 2020 set by the EU Waste Framework Directive. The transformation is the result of waste management improvements, including near-total coverage of the population by municipal waste management services, separate waste collection, construction of sorting facilities, improved labelling requirements, education and awareness campaigns, and expansion of deposit refund schemes (DRSs) for beverage containers made of different materials.

The pricing of municipal waste management follows the principle of full cost recovery. Charges for waste management services include a fixed component for administrative and infrastructure costs and a variable component that can be set according to the number and size of mixed municipal waste containers used; the frequency of emptying them; or the weight of mixed municipal waste generated. The charges promote waste separation at source and reduction of waste going to landfills. Municipalities set the charges within limits defined by the central government.

Reducing biodegradable waste (bio-waste) has been and continues to be a national waste policy priority. Public awareness campaigns promote behaviour change, and the government plans to install food waste sorting and collection infrastructure for household waste. The new National Waste Management Plan (2021-2027) requires municipalities to sort bio-waste (green and food waste) and to collect it separately, in line with the EU requirement to do so from 2024. While most municipalities are still working to implement this requirement, those in the Alytus region have already started separate food waste collection (including from apartment buildings), reportedly without additional costs for municipalities.

In 2016, Lithuania introduced a DRS for primary packaging on glass, plastic or metal beverage containers. In 2019, 92% of relevant packaging was collected through the DRS. Individuals buying the covered beverage containers (marked with the deposit symbol) pay the deposit (EUR 0.10) at the point of sale. After delivering the used package to a collection point (e.g. a store or a reverse vending machine), consumers receive a refund on their deposit.

Treatment of municipal waste and municipal waste per capita in Lithuania, 2005-19

Note: Excluding marginal quantities of waste incinerated without energy recovery. Data include breaks in time series.

Source: OECD (2021a).

Bio-waste, composed of yard and food waste, accounted for almost two-thirds of the household and commercial waste recovered in 2020. However, the quality of the waste recovered is relatively poor, given most of it was recovered post-collection rather than separated at source. Meanwhile, packaging-related materials, including paper, cardboard, plastic, metal and glass, made up 26% of recovered waste (Figure 2.2). Paper and cardboard waste is separated at source in designated facilities and collected at prices set by local authorities. Approximately 260 Mt of paper and cardboard packaging is collected annually, most of which is recycled in Hadera paper mills for raw material for Israel’s paper industry. Around 12% of this waste sent for recycling is landfilled as a by-product.

The country generates an estimated 1 Mt of plastic waste annually, of which only about 7% is recycled and 11% goes to energy recovery. The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030) establishes weight‑based recycling targets for plastic packaging waste (55%) and glass containers (75%) (MoEP, 2020b). However, these targets are not anchored in legislation. The total collection rate of glass container waste was 50% in 2016, significantly lower than in many European countries. The collected glass is transferred to three processing plants for treatment and processing. An estimated 40% of the collected glass is handled in the local market at the only glass recycling site in Israel. The factory is not operating at capacity, due to issues with separation by colour. Much of the remaining glass is exported. More broadly, the National Plan for MSW Treatment aims for higher recycling rates and waste-to-energy conversion as a crucial means to reduce the amount of waste going to landfill.

Growing waste generation levels, poor segregation of organic waste and high landfilling rates make the waste sector an important contributor to Israeli GHG emissions. The waste sector is responsible for approximately 8% of GHG emissions, excluding land use, land-use change and forestry (UNFCCC, 2021). In contrast, the waste sector contributes to about 3% of total GHG emissions on average in OECD countries. In Israel, most of the direct GHG emissions from waste stem from methane emitted from biological decomposition of waste in landfills. The geographical mismatch between the regions producing most of the country’s waste in the centre and the location of landfills in the northern and southern parts of the country adds transport-related GHG emissions. GHG emissions from MSW in Israel grew on average by 0.9% per year between 2011 and 2019 (UNFCCC, 2021).

Figure 2.2. Landfilling contributes significantly to GHG emissions; bio-waste accounts for most recovered waste

Note: Municipal waste includes household waste and similar waste collected by or on behalf of municipalities. It includes bulky waste and excludes construction waste and sewage waste. Breakdown data for recycling and composting are available from 2013.

Sources: CBS (2022), Waste and Recycling (database); OECD (2022), "Waste: Municipal waste", OECD Environment Statistics (database); UNFCCC (2022), Israel National GHG Inventory 2021.

Although reduction of MSW per capita is one of three overarching aims of Israel’s Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030), it does not have a measurable target. The “best case scenario” forecast by the strategy, where all policy measures are applied to reduce MSW at the source, projects an 11.5% reduction of MSW generation. The measurable targets of the 2030 strategy relate to reducing the share of waste being landfilled (maximum 20% of MSW), the uptake of recycling for MSW (54% of which should be recycled) and packaging waste (70%), separation at source (no landfilling of untreated waste) and GHG emissions (-47% compared to 2015 levels).

These targets are aligned with those of the National Action Plan on Climate Change 2022-2026 (NAPCC),2 which aims for climate neutrality by 2050. However, the NAPCC expresses the target for landfilling MSW differently from the Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030). The strategy states that no more than 20% of MSW should be landfilled by 2030, while the NAPCC aims for a 71% reduction of the amount of MSW landfilled annually by 2030. The NAPCC also includes a target for the reduction of MSW at source by 2030 (-12%) that is absent from the strategy (MoEP, 2021a).

Current monitoring gaps might undermine achievement of these targets. The strategy points to discrepancies in data collection between the MoEP and local authorities. In addition, waste data are too sparse for an accurate picture of primary waste: data exist for certain categories, depending on the year, but the total level of primary waste is not computable.

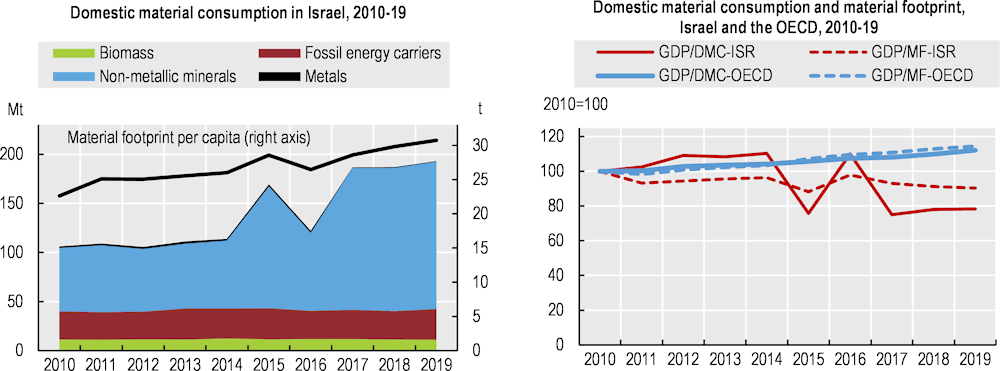

2.2.2. Material flow and resource productivity

Israel’s economy is relatively resource-intensive, as the country’s domestic material consumption (DMC) and material footprint per capita are above the OECD average. In 2019, Israel had a DMC per capita of 22.7 tonnes, above the OECD average of 17.5 tonnes per capita. With the inclusion of materials extracted abroad and embodied in imported goods, Israel’s material footprint amounts to 30.8 tonnes per capita. This rate is similar to the one in the United States, while the OECD average is 21.5 tonnes per capita.

Israel’s material productivity3 declined between 2010 and 2019, contrary to the average trend observed across OECD countries (Figure 2.3). Israel’s trend was partly driven by rising domestic fossil fuels extraction (OECD, 2019a) and a strong increase in consumption of non-metallic minerals in the construction sector. On the other hand, most OECD member countries have experienced improvements in material productivity since 2000. These improvements have occurred due to more efficient production processes; changes in the materials mix; and substitution of domestic production by imports (OECD, 2022a).

Additionally, Israel’s DMC profile is different from the OECD average in terms of materials consumed. The country’s DMC is dominated by non-metallic minerals, which accounted for 78% of DMC in 2019, the highest share among OECD member countries (OECD, 2022a). The sharp increase in non-metallic minerals in 2014 and 2016 and the sustained increase since then are attributable to increased construction activity. Fossil energy materials account for 16.2%, while biomass represents 5.8% and metallic minerals 0.4% (one of the lowest among OECD countries). The OECD material mix is also dominated by non‑metallic minerals (mostly for construction) but to a lesser extent than in Israel, at 39%. Biomass and fossil energy materials/carriers both account for 23.8% each, while metals make up less than 14% of the total on average.

Figure 2.3. DMC and material footprint per capita have grown, making material productivity decline

Note: Domestic material consumption (DMC) refers to the amount of materials directly used in an economy. Material Footprint (MF) refers to the global allocation of used raw material extracted to meet the final demand of an economy. GDP/DMC-ISR refers to the productivity of DMC in Israel; GDP/DMC-OECD refers to the average productivity of DMC in OECD countries; GDP/MF-ISR refers to the productivity of Israel’s MF; and GDP/MF-ISR refers to the average productivity of MF in OECD countries.

Source: OECD (2022), "Material resources", OECD Environment Statistics (database).

2.3. Institutional arrangements

2.3.1. Division of responsibilities

Both central and local governments have responsibilities for waste management (Table 2.1). The Ministry of Interior (MoI) regulates intra-municipal waste systems consisting of storage, collection and transport. The national government also operates national hazardous waste facilities. Municipal waste collection is mostly carried out by municipal sanitation departments: local authorities determine the deployment and configuration of collection bins based on land uses, waste streams, evacuation methods, composition of waste and quantity, and frequency of waste removal. However, private sector collection is becoming increasingly common with the rise of competitive tendering. Once collected, municipal waste is transferred to a sorting facility, then to a recycling or a landfill site. Commercial and industrial waste producers manage their own waste. Meanwhile, waste streams covered by an extended producer responsibility scheme are managed by producer responsibility organisations or local authorities (OECD, 2019a).

The MoEP is in charge of compliance assurance: its inspectors impose fines for illegal dumping or burning of waste, while the Green Police investigate criminal offences (Section 1.5). The MoEP also collects data from waste sites under its supervision (landfills, transit stations and some recycling sites) for the Waste Information System, created in 2017. According to the Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030), the MoEP should be authorised to determine thresholds and standards for storing, transporting, recycling, composting, incinerating and landfilling waste. The ministry should also be able to set targets to limit waste disposal and exports, as well as establish criteria for end-of-waste4 decisions.

Table 2.1. Waste management responsibilities are spread across levels of government and stakeholders

|

Waste type |

Responsible body |

|

Intra-municipal |

Ministry of Interior |

|

Hazardous |

Ministry of Environmental Protection |

|

Municipal |

Local authority or regional association |

|

Commercial and industrial |

Waste producer |

|

Extended producer responsibility streams |

Producer responsibility organisation or local authority |

Source: MoEP (2020b).

There is some cross-ministerial collaboration on energy efficiency and waste management but less relating to development of a circular economy. Initial dialogues are taking place between the ministries of interior; construction and housing; economy; environmental protection; and energy, as well as the anti-trust, innovation, planning and land authorities, to define how to promote circular economy principles in the built environment. Horizontal collaboration could promote circular economy principles in housing and infrastructure. In so doing, it would strengthen the Strategic Development Plan towards 2040 developed by the Israel Planning Administration under the Ministry of Interior. In addition, the ministries of agriculture, education and finance, as well as specialised government agencies, play a role in transitioning from a waste to a resource management approach, co-ordinating actions and enhancing policy coherence.

As argued by OECD (2021b), governments should mainstream the goal of resource efficiency into cross-cutting policies such as on innovation, investment and education. This would reduce pressures from major resource-consuming sectors. The shift towards a circular economy should be shared across ministries rather than a sole responsibility of environmental ministries and agencies. Sharing responsibility would permit taking advantage of economic opportunities across economic sectors. For example, Ireland’s circular economy policy, led by the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications, was born out of the country’s waste policy, which led to an initial focus on waste management (OECD, 2022b). In a positive move, the new Whole of Government Circular Economy Strategy includes setting up an inter-departmental Circular Economy Working Group with relevant ministers, government departments, state agencies and local governments.

Beyond environmental and economic ministries, the government can involve other departments in developing circular economy policies. One good practice example is the Spanish Inter-ministerial Commission for the country’s circular economy strategy (Box 2.2). In other countries, ministries of environment share the responsibility for circular economy policy with the Ministry of Industry (Colombia and Denmark), the Ministry of the Economy and Finance (Italy), or the Federal Ministry of Jobs, Economy and Consumers (Belgium). In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management and the Ministry of Economic Affairs are the main responsible authorities (OECD, 2020b). In Italy, an Observatory on the circular economy will be the implementing body of the recently approved National Strategy on the Circular Economy (June 2022).

Box 2.2. In Spain, ministries co-ordinate to implement its circular economy strategy

The Spanish Circular Economy Strategy (España Circular 2030) was jointly promoted in 2018 by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Food and the Environment and the Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness. An inter-ministerial commission formed by 14 ministries and the Economic Office of the President contributes to it, together with the autonomous communities and the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces.

The commission meets at least once a year to evaluate and monitor implementation of the national strategy. Additionally, the commission has created a working group for autonomous regions responsible for forming other working groups to further implement the strategy. As of June 2022, the government of Spain has approved a first triennial Action Plan for the Circular Economy announced as part of the strategy and adopted a new law on waste and contaminated land for a circular economy. The law aims to reduce waste by 15% compared to 2010 by 2030 and to increase the share of waste reused rather than recycled (10% of total by 2030), among other objectives.

Sources: Government of Spain (2020); OECD (2020b).

2.3.2. Role of local authorities

The government aims to use clusters (eshkolot) as functional bodies for locating and operating waste treatment facilities that can benefit from economies of scale and reduced number of tenders. Established under the Arrangements Act in December 2016 and added to the Cities Associations Act, these clusters are groups of local authorities with executive bodies (Section 1.2). The clustering started as a voluntary and bottom-up process with the establishment of the Western Galilee Cluster in 2009 (OECD, 2019b). In 2012, the MoI, the Ministry of Finance and several civil society organisations created a pilot programme to establish voluntary regional clusters. They reached legal status in 2016. By 2022, their number had increased from 5 to 11 while the number of associated local authorities had increased from 59 to 147.5 Clusters, based on agreements across municipalities, are managed by a committee of municipality representatives and professional experts.

Further consideration should be given to the role of local governments in waste management, beyond operational aspects. Local governments’ responsibilities include delegated and own functions, such as waste collection (Section 1.2). By law, municipalities must collect packaging and electrical waste separately but can decide on sorting other types of waste. Nevertheless, due to a lack of economic incentives and recycling infrastructure, separate waste collection is not widely implemented, generating inconsistency in collection methods across the country.

Most European OECD countries favour separate, kerb-side collection of recyclable municipal waste, which can enhance waste separation and recycling levels (OECD, 2019a). Some countries (e.g. the Czech Republic) rely on voluntary deposits at containers and civic amenity sites where households can dispose of and recycle waste. Other countries (e.g. France and Ireland) rely on a mix of both (OECD, 2022b). Israel should develop a modern approach to waste management and promote separate collection and recycling to reduce landfilling, while starting to implement a materials cycle. It should also ensure that materials incorporated in products sustain a high value by fostering ecodesign, repair and reuse.

Beyond bridging the infrastructure gap across municipalities, broader capacity building programmes will be needed for more sustainable waste management. The Sviva Shava (Equal Environment) project implemented over 2014-20 recognised significant gaps in waste management practices between the minority sector local authorities and other municipalities (Section 1.8.3). The project highlighted the need to raise awareness and build capacities and knowledge across local communities to enhance separate collection and limit illegal treatment. In this context, developing platforms for city-to-city dialogues could help local authorities learn from others on project design and management, funding, sustainable management practices and circular economy principles. In addition, the national government should support local capacity building to promote the transition to a circular economy. Finally, cities could implement pilots and experiments in various sectors to test the impacts of circular-related practices. For example, it could pilot circular neighbourhoods, analysing construction techniques and resource efficiency for potential scaling up.

To build capacities, the government could establish guidelines and provide flexibility through decentralised decision making. In some OECD member countries, this happens through contracts between levels of governments, frequently used in the framework of regional development. According to the maturity of decentralisation processes and the capacity of national and subnational governments, the OECD identifies three main types of contracts between central and subnational governments: empowerment, delegation and policy sharing. Empowerment contracts can transfer responsibilities to subnational governments while gradually building capacities for policy implementation. They do this by valorising the role of local decision makers in targeting initiatives and using untapped potential. Central governments can include specific incentives as conditions of their signature, such as partnering with private actors, involving neighbour local governments, adopting specific regulations, etc. Delegation assumes that regional and local actors are better positioned to implement national policies at the local level, with more efficiency in public spending. Policy-sharing contracts allow common decision making, dialogue and sharing of financial and political risks across levels of government (Charbit and Romano, 2017).

2.4. Legislative framework and regulations for waste handling and treatment

2.4.1. Recent regulatory developments

The 2011 EPR recommended that Israel consolidate arrangements for management of waste in a comprehensive and coherent new policy or law. However, to date the country still has no national legislative framework for waste management. Waste-related requirements are scattered across different laws and regulations concerning health, hazard prevention, business, cleanliness, recycling and air pollution (MoEP, 2020b). The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030) foresees the consolidation of main policies and regulations of the waste sector in a single framework law. This law would formulate basic guiding principles of waste management (waste management hierarchy, internalisation of negative externalities and the “polluter pays” principle), provide for a licensing and registration system, set targets and better define roles and responsibilities (including for compliance assurance) (MoEP, 2020b).

Extended producer responsibility is regulated by laws on the deposit of beverage containers, tyres, packaging, electronic waste and disposable carry-on bags. The quantity of potentially recyclable waste covered by these laws represents 22% of total household and commercial waste. In line with a 2011 EPR recommendation, these developments include extended producer responsibility schemes for tyres, packaging, and waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), a DRS for beverage containers and a plastic bag law (Table 2.2).

In 2016, Israel passed the Law for Reduction of Use of Disposable Plastic Carrier Bags to ban the distribution of “very thin” (width of less than 20 microns) plastic bags in supermarkets and mandate a levy of at least ILS 0.10 for bags between 20 and 50 microns. The law does not apply to other businesses such as pharmacies and toy stores. Following the law’s entry into force in 2017, the number of plastic bags dispensed by retailers dropped from 2.8 billion (325 bags per Israeli) to 1.5 billion (171 bags per capita) in 2017. The Packaging Law provided for a ban on landfilling of packaging waste by 2020. Nevertheless, due to a lack of a dedicated infrastructure or a market for secondary material, this provision of the law has not yet been enforced. As of July 2021, the WEEE Law, which holds manufacturers and importers responsible for their products at end-of-life, also covers electric bicycles and scooters. Similarly, in December 2021, the 1999 Deposit Law was extended to large beverage containers.

Table 2.2. Waste prevention legislation has developed in the last two decades

|

Date |

Sector |

Law |

|

1999 |

Plastic, glass and aluminium |

Beverage Container Deposit Law on bottles of up to 1.5 litres |

|

2007 |

Tyres |

Tyre Disposal and Recycling Law |

|

2011 |

Packaging |

Packaging Law |

|

2012 |

Electronics |

Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Law |

|

2016 |

Plastic |

Plastic Bag Law |

|

2021 |

Plastic, glass and aluminium |

Deposit Law was extended to beverage containers of 1.5-5 litres |

Source: Country submission.

A number of laws related to waste handling and treatment are under discussion and are likely to enter into force in the coming years. In line with a 2011 EPR recommendation, progress has been made in hazardous waste regulation. The Free Export and Import Ordinances were amended in 2021 to ensure effective oversight of cross-border movements of waste, based on licences granted according to Basel Convention. The Ministry of Economy and Industry (MoEI) is drafting an internal procedure that would provide a classification of hazardous wastes, as well as definitions of end-of-waste criteria and of a by-product. The absence of a standard for compost means that composted food waste does not always meet the quality requirements for use in agriculture. Consequently, another regulation will ban the landfilling of bio-waste without pre-treatment and set requirements for the share of stabilisation and treatment of bio-waste coming from sorting facilities. The government will propose amendments to legislation (e.g. on packaging and expanding extended producer responsibility schemes) based on EU laws.

Israel’s waste management legislation must be updated, consolidated and streamlined to modernise the recycling industry and promote behavioural changes conducive to a circular economy. The patchwork waste-related regulations and the absence of harmonised definitions and procedures mean that the private sector is unable to make long-term plans and operate changes to “business as usual” with certainty.

Following a circular economy approach that extends beyond waste management, Israel should consider the perspectives of both producers and consumers (e.g. ecodesign and reuse). As part of its Sustainable Products Initiative, the European Commission (EC) intends to propose new “right to repair” legislation in the third quarter of 2022. This would strengthen consumer rights to repair products at fair prices, with the objective of extending products’ useful life (Box 2.3). Preventing waste across the entire life cycle of products could allow Israel to aim for a higher target than the 12% reduction in MSW generation levels at source by 2030.

Box 2.3. EU circular economy measures aim at closing loops and changing behaviours

In December 2015, the European Commission adopted a Circular Economy Package to support the EU transition to a circular economy. The package sets out 54 actions targeting the entire life cycle of products across 6 priority areas (plastics, food value chain, critical raw materials, construction and demolition, biomass and bio-based products, and innovation). The package also includes four legislative proposals amending the Waste Framework Directive, the Landfill Directive, the Packaging Waste Directive and directives on end-of-life vehicles, batteries and accumulators, and WEEE. It sets the following targets:

55% of municipal waste recycled by 2025, 60% by 2030 and 65% by 2035

reduction of landfilling to 10% of municipal waste generated in 2035

mandatory separate collection for hazardous waste (2022), organic waste (2023) and textiles (2025).

It also foresees a reform of extended producer responsibility schemes, broadening their scope and governance and setting new objectives for preventing waste, especially marine and food waste.

In January 2018, several new measures were adopted, including the EU Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy, to transform the way plastic products are designed, produced, used and recycled. By 2030, all plastic packaging should be recyclable in the European Union.

The new Circular Economy Action Plan, adopted in March 2020, is one of the building blocks of the Green Deal. It sets out 35 actions and initiatives aiming to:

make sustainable products the norm in the European Union

empower consumers and public buyers

focus on sectors that use the most resources and where the potential for circularity is high

ensure less waste

make sure circularity works for people, regions and cities

lead global efforts on the circular economy.

Under the Circular Economy Action Plan, the European Commission has several initiatives to improve the reparability and extend the useful life of products. The Sustainable Products Initiative, for example, revises the Ecodesign Directive and proposes additional legislative measures to make products more durable, reusable, repairable, recyclable and energy efficient. The initiative was adopted in March 2022, alongside a proposal for a directive on Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition. This directive would ensure that consumers have access to information on a product’s durability and reparability before they buy it.

Source: EC (2020, 2018), European Parliament (2022); OECD (2020b); Šajn (2022).

2.4.2. Implementing the packaging law

Clear communication and stakeholder engagement are key to fulfilling the obligations and targets foreseen by the Packaging Law. The law requires every producer to engage in a compliance scheme recognised by the MoEP. TAMIR, established in 2011 by major Israeli manufacturers and importers, is the only recognised packaging recovery organisation. TAMIR funds the separation and collection of packaging waste as well as ensures compliance with recycling targets set by the Packaging Law. Manufacturers and importers must pay fees to TAMIR according to the weight of the material and the type of packages they put on the market. Beyond manufacturers and importers, TAMIR foresees signing contracts with local authorities to enhance separate collection and removal of packaging waste, which represents about 74% of household waste.

As of 2021, TAMIR entered into agreements with about 1 700 Israeli producers. They reported approximately 455 000 tonnes of packaging, which represented 57% of the packaging waste marketed in Israel in 2020. This implies that many producers do not comply with their obligation to enter a recognised compliance scheme. This free riding increases the financial burden on the producers who comply with their obligations and generates an unfair competitive advantage for non-compliant producers. Israel may benefit from the experience of Spain and Italy where a similar system helps foster sustainable management of packaging (Box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Intermediary companies promote packaging recycling in Spain and Italy

In Spain, the non-profit environmental organisation Ecoembes promotes and manages the system for recycling household packaging waste across the country. The organisation gathers more than 12 000 companies that are requested by law (Law 11/1997 on Packaging and Packaging Waste) to finance a system of selective collection and recycling of household packaging. Ecoembes is financed through the “Green Point”, a fee paid by packagers and distributors placing packaging on the market for consumption. This fee ensures that packaging is recycled at the end of its useful life.

In Italy, producers and users of packaging rely on CONAI, a private not-for-profit consortium, to guarantee achievement of the objectives of recycling and recovery of packaging waste stipulated by law. Indeed, Legislative Decree No. 22/97 assigned to the consortium the task of achieving the overall target and implementing targeted management policies, including prevention through eco-innovation. The CONAI system aims to guarantee compliance through extended producer responsibility. Producers and users joining CONAI must pay the CONAI Environmental Contribution, which varies depending on the type of packaging put on the market. Municipalities cover additional charges resulting from separate collection of packaging.

Source: OECD (2020b); CONAI (2022).

2.4.3. Fighting illegal dumping

The government has made progress in fighting illegal waste dumping. These actions were in line with the 2011 EPR recommendation to strengthen national and local efforts to address remaining problems with unregulated waste disposal and safely dispose C&D waste. Since 2011, Israel has strengthened inspection and surveillance against illegal disposal of C&D waste in dumping sites and open spaces. It has also developed standards on use of recycled aggregates in infrastructure projects, and set administrative and criminal enforcement procedures. In addition, the government has provided financial and technical support to local authorities to tackle illegal waste disposal (e.g. under the Sviva Shava project).

However, illegal open burning of waste persists in certain areas of the country. Construction waste managers lack the technological expertise to produce aggregates made with recycled content of sufficient quality for infrastructure projects. This represents a significant barrier for use of recycled building waste in Israel (22% marketed, compared to 89% in the European Union). In addition, infrastructure projects have long lead times (five years from planning to implementation). Consequently, recycling entities selling construction aggregates cannot commit with certainty to providing the quantities required by the project. This poses a risk to the infrastructure developer.

In 2012, the government decided to start collecting refrigerators and cooling devices for recycling. However, high-value waste streams such as WEEE and end-of-life vehicles are still a concern for illegal dumping. A draft regulation forbidding illegal burning of waste from agriculture faces opposition. In 2018, the MoEP established a dedicated unit for fire prevention, working in co-ordination with the Green Police and the Fire Department of the Ministry of Public Security. It monitors illegal transfers of waste for open burning in areas controlled by the Palestinian Authority. The unit is endowed with the power to issue clean‑up orders and fines (ILS 600 for the illegal burning of waste by individuals and ILS 2 000 for companies). These fines are doubled if the order is not complied with by the deadline.

In addition to enforcement, the MoEP supports local authorities. For example, the Arab Society Programme (Section 1.8.3) foresees capacity building, pilots for separate collection within specific clusters with standards for waste collection and treatment, and the financing of bulky waste collection for five years.

2.5. Planning, pricing and other policies towards a circular economy

2.5.1. Planning for sustainable waste management

The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030) is part of a long-term vision of transforming Israel's linear economy to a circular one, in line with a zero-waste aspiration for 2050. Its three main objectives are to reduce landfilling (from 80% to 20% in 2030), ease pressure on natural resources and reduce GHG emissions. The 2020 National Plan for MSW Treatment to 2040 also highlights the need to increase recycling and reduce landfilling through three key measures. These comprise supporting industry and research and development to increase recycling rates; prohibiting landfilling of unsorted waste; and increasing waste-to-energy for non-recyclable waste (MoEP, 2020a). By the end of 2023, six additional sorting facilities are planned for construction and operation. The sorting facilities would separate waste for the following treatment streams: fertilisation and biological stabilisation of bio-waste; anaerobic digestive facilities for bio-waste; and recycling facilities for paper and cardboard, plastic and glass waste.

As food waste represents one-third of Israel’s household waste, the strategy foresees specific actions for this waste stream. First, similarly to EU legislation, it would mandate separation of bio-waste at source through legislation within the next five years. Second, it would establish an EU-like standard for compost. Finally, it would provide financial support for anaerobic digestion facilities and integrated mechanical and anaerobic digestive facilities. Beyond household food waste, significant efforts would be needed to address the food system as a whole, from production to consumption (Box 2.5). This approach should ensure that separated bio-waste feeds back into local food chains as animal feed, where appropriate. It could also be transformed into biogas, compost or fertiliser.

Box 2.5. Working across the value chain can reduce food waste in Israel

The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MoARD) works across the value chain to reduce food loss and waste, including by:

Developing packaging to extend shelf life and reduce food loss along the supply chain. The solutions include smart packaging for fresh agricultural produce (e.g. packages that help regulate humidity levels) and various post-harvest treatments to reduce waste (e.g. covering potatoes with menthol oil to prevent sprouting).

Operating an educational programme with the Ministry of Education to encourage smart consumption of fruits and vegetables in schools.

Formulating marketing strategies encouraging the sale and buying of “ugly” fruits and vegetables.

Publishing fruit and vegetable conservation guidelines to consumers, wholesalers and retailers.

The MoEP developed Israel’s Food Donation Act in 2018 to protect those in the food donation chain from liability. Everyone from food donors to non-profit organisation employees and volunteers must meet food safety standards. The Act protects them from liability for damages that might be caused by their food donations. MoEP-led initiatives on food waste target households, students and businesses include the following:

In 2011, the MoEP launched a household campaign (“Let's Think Green”) to change public perceptions and behaviour regarding the environment, including responsible food shopping and over-consumption; since 2019, it has also led workshops nationwide on reducing food waste in households.

Since 2016, a new topic dealing with food waste reduction has been added to the co-operative sustainability education programme. This programme, which reaches about 100 000 students a year, is run by the MoEP and the Ministry of Education.

To address food waste in businesses, the standard for labelling food packages was re‑examined, and several options were planned for improving it. Additionally, in 2016, the MoEP, the city of Tel Aviv-Jaffa and the Israel Standards Institute launched a “Green Label” for cafes and restaurants. One of the requirements for getting the badge includes efforts at reducing food waste.

The MoEP, the MoARD and other ministries have also been collaborating with TNS Israel on reducing food waste. In March 2017, the MoARD, TNS and the Manna Center Program for Food Safety & Security at Tel Aviv University held a “hackathon” on reducing food loss and waste, following which two projects received support for further development.

Source: Country submission; MoEP (2020b).

Given the country’s high level of wastewater treatment, nutrients recovered from wastewater can also become part of the solution to enrich soils and make agriculture more resilient to climate change. This can be done by strengthening urban-rural partnerships. Israel could also consider adopting a regulation similar to one in France that bans disposal of food waste from outlets such as supermarkets and large catering services (Box 2.6).

Box 2.6. The fight against food waste in France starts with legislation here

Two recent laws made France the first country in the world to ban supermarkets from throwing away or destroying unsold products. The 2015 Energy Transition for Green Growth Law covers “the fight against waste and the promotion of the circular economy from product design to recycling”. A year later, France adopted the Law on Combating Food Waste. These are the two main instruments to reduce food waste in the country.

The 2020 anti-waste law for a circular economy strengthens the fight against food waste by setting ambitious targets. For instance, by 2025, the food distribution and catering sectors (supermarkets, canteens, etc.) will have to cut food waste in half compared to 2015 levels. Moreover, retailers are obliged to donate their unsold food products to charities, and the law prohibits the disposal or spoiling of unsold food. The new law reinforces penalties for the destruction of unsold but edible food. It also introduces a national anti-food waste label that promotes initiatives to reduce food waste and guide consumer choices.

Source: ADEME (2019), Ministry of Ecological Transition (2020).

The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy is a first step in the direction of a circular economy as it recognises the need to implement sustainable waste management and improve resource efficiency. However, a detailed and ambitious roadmap that would identify key sectors, actors and actions is still missing. Defining such a roadmap would enable a clear vision of the steps to achieve defined targets. It could also bolster support from businesses and other actors for its implementation (Box 2.7).

Box 2.7. Circular economy strategies go beyond waste management

In the European Union, more than 60 strategic circular economy frameworks and roadmaps have been developed at the national and subnational levels. They tend to be built around eight key blocks:

a vision of the desired future state

qualitative goals the transition aims to achieve

links to other policies and strategies

an indication of interest groups involved

a selection of priority areas

quantitative targets

implementation measures and monitoring

evaluation and communication plans.

There is a great diversity of approaches for developing these strategic frameworks. These largely depend on local context, challenges and potential benefits, as well as underlying drivers and stakeholder involvement. The following are some examples of national and subnational circular economy strategies in OECD countries:

The Circular Economy in the Netherlands by 2050 strategy is based on five priorities: biomass and food; plastics; manufacturing industry; construction sector; and consumer goods.

Colombia has six lines of action in its 2019 National Strategy for the Circular Economy: flow of industrial materials and mass consumption products; flow of packaging materials; flow of biomass; energy sources and flows; flow of water; and flow of construction materials.

For the city of Paris (France), the first roadmap adopted in 2017 included 15 actions for planning and construction; reduction, reuse, repair; support for actors; public procurement and responsible consumption. The second roadmap, adopted in 2018, defined 15 actions organised in five new themes: exemplary administration; culture; events; sustainable consumption; and education.

Source: OECD (2021c; 2020a).

More broadly, Israel’s policies lack a life-cycle perspective. In particular, the uptake of policies and standards towards ecodesign and reuse is very low. Additionally, although standards exist in the form of green labels, they are voluntary and thus rarely used. Israel should start to develop higher-value material loops, whereby materials are recovered, reclaimed, recycled or biodegraded through natural or technological processes. It should also foster ecodesign, repair and reuse.

There is a need to bridge the data gaps in terms of total waste, material flows, resource efficiency, and material exports and imports (Section 2.2). The lack of information and data on waste streams is a barrier for new players in the market, preventing them from estimating the market for secondary material. Moreover, this information would help identify the most resource-intensive sectors and enable key actors to prevent waste and keep resources in use for as long as possible. To build knowledge and evidence on resource inputs and outputs, Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and the MoEP are developing material flow accounts (MFAs). As part of developing the strategy for green growth indicators, the CBS, the MoEP and the MoEI are establishing an infrastructure of environmental accounting that will include waste, expenditure and MFAs. Selected input and outcome indicators could be used to evaluate the status and progress of the strategy’s roadmap (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Measuring results of circular economy strategies helps improve policies

|

Phase |

Type of indicator |

Indicators for the circular economy strategy: Inputs, process and outputs |

|

Setting the strategy |

Process |

Number of public administrations/departments involved |

|

Process |

Number of stakeholders involved |

|

|

Input/process |

Number of actions identified to achieve the objectives |

|

|

Input/process |

Number of projects to implement the actions |

|

|

Process |

Number of projects financed by the government/Total number of projects |

|

|

Process |

Number of projects financed by the private sector/Total number of projects |

|

|

Process |

Number of staff employed for the circular economy initiative and implementation within the administration |

|

|

Implementing the strategy |

Environmental output |

Waste diverted from landfill (t/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

Environmental output |

By-product or waste reused as material (t/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

|

Environmental output |

CO2 emissions saved (t CO2/capita or %) |

|

|

Environmental output |

Virgin material use avoided (t/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

|

Environmental output |

Use of recovered material (t/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

|

Environmental output |

Energy savings (Kgoe/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

|

Environmental output |

Water savings (million litres/inhabitant/year or %) |

|

|

Socio-economic output |

Number of new circular business |

|

|

Socio-economic output |

Number of businesses adopting circular economy principles |

|

|

Socio-economic output |

Economic benefits (e.g. additional revenue and costs saving) (EUR/year) |

|

|

Socio-economic output |

Number of employees in new circular businesses |

|

|

Socio-economic output |

Number of jobs created in the circular economy |

|

|

Governance output |

Number of procurement contracts, including circular criteria (no. of contracts per year/expenditure per year (%) |

|

|

Governance output |

Number of companies or employees trained to adopt circular economy principles |

|

|

Governance output |

Number of contracts awarded that include a circular economy criterion/Total number of contracts |

|

|

Governance output |

Share of public investment dedicated to the circular economy policy in total public investment (%) |

Source: OECD (2020a).

2.5.2. Economic instruments to reduce waste production and landfilling

Property owners in Israel pay for waste collection and treatment services along with other municipal services as part of the Israeli property tax. This gives households a limited economic incentive to reduce waste or separate waste streams. No real progress has been made in relation to the 2011 EPR recommendations to increase the level of the waste collection component of the municipal property tax to reflect the real costs of the service, and to introduce volume- or weight-based waste disposal fees for mixed waste payable by households. Waste collection and treatment fees are included in municipal property taxes and set according to the size of a household or business (OECD, 2019a). In 2016, the ministries of finance and environmental protection began supervising the prices of MSW collection and treatment to prevent increases due to lack of competition. This, in turn, was intended to reduce the cost of living.

A charge on disposable plastic utensils below a designated thickness threshold (making their reuse unlikely) has been levied since November 2021. Figures from the MoEP show that over the past decade the consumption of disposable plastic in Israel has been steadily rising. It reached an estimated 13 billion items per year (MoEP, 2020b). At ILS 11 per kg, the charge doubles the price of single-use plastic utensils for the consumer. The charge aims to significantly curb Israel’s high use of these items (7.5 kg per person per year compared to the EU average of 1.5 kg per person per year). Data from November 2021 showed a 65% decline in sales compared to the previous month (MoEP, 2021b). The charge is accompanied by an extensive bilingual communication campaign. The campaign, targeting several population segments, is supported by university studies in behavioural economics. In addition to this charge, the DRS for beverage containers was recently expanded to large-volume (1.5-5 litres) aluminium, glass and PET beverage containers.

The Sustainable Waste Economy Strategy (2021-2030) recommends incentivised charging with save-as-you-throw or pay-as-you-throw mechanisms, where consumers pay for waste disposal based on weight and waste stream. The MoEP supports pilot projects to implement economic incentives via “recycle and save” mechanisms in households to examine various methods of implementation and their impacts (MoEP, 2020b). Separating waste management income and expenses from local property taxes would allow local authorities to improve monitoring of the efficiency and effectiveness of waste collection and treatment services. Moreover, it would make waste management costs visible to households, incentivising them to reduce waste generation at source. In implementing the strategy, Israel can draw on the experience of European countries with a number of price-based tools of waste management (Box 2.8).

Box 2.8. European countries use a range of different price-based tools for waste management

A few countries have introduced volume-based pricing (pay-as-you-throw). For example, almost all municipalities in the Netherlands impose a municipal solid waste (MSW) fee on households. The fee can be variable based on the volume of waste (40% of municipalities), fixed according to the size of the household (53% of municipalities) or a flat rate (7% of municipalities). The volume-based approach was shown to be more efficient and environmentally effective. Indeed, separate collection was much higher in areas with volume-based approaches (60%) compared to other fee-setting approaches (as low as 7%). Municipalities in the Czech Republic have three options for setting fees: pay-as-you-throw, an annual fee based on household size or a contractual fee. Around 15% of municipalities use the pay-as-you-throw option.

With deposit refund schemes, the customer makes an initial payment (deposit) at the point of purchase and gets refunded if the product or packaging is returned to the collection scheme. This approach is used for beverage containers in several European countries and North American states or provinces. Such policies specify the product category (e.g. beverage containers) and detail exemptions for particular types of this product category.

Ensuring an effective policy mix is a key determinant in the success of waste management policies. Public awareness and support are crucial for changing behaviour and generating acceptance of new measures (e.g. for pay-as-you-throw charging). In Ireland, the Circular Economy Programme led by the Environmental Protection Agency has been instrumental in raising awareness and improving household knowledge on waste prevention and separation through engagement with a wide range of stakeholders.

Source: OECD (forthcoming, 2022b, 2019a).

The landfill levy, in place since 2007, continues to be the main economic instrument for internalising the cost of landfilling in Israel (Table 2.4). The rate of the landfill levy depends on the type of waste. Rates are lower for sorted or pre-treated waste than for unsorted MSW. They are very low for construction waste to discourage its illegal disposal. In addition to the landfill levy, landfill sites charge handling fees (estimated at an average of ILS 70 per tonne). Transport costs per landfill are estimated at ILS 42 per tonne (calculated at ILS 0.7 per tonne per km, assuming 60 km on average) (MoEP, 2020b). The total direct cost of landfilling, i.e. the sum of the landfill levy and gate fees, is around ILS 240 per tonne (EUR 67). This is relatively low in comparison to many EU countries (e.g. EUR 107 in Denmark and EUR 132 in the Netherlands) and insufficient to discourage this practice. The cost of landfilling is lower than that of incineration with energy recovery (estimated at ILS 300 per tonne) and of organic waste treatment (ILS 250-300 per tonne). This makes landfilling the cheapest and thus most incentivised option.

Table 2.4. Landfill levy rates have remained stable since 2018

Landfill levy rates in Israel, 2018-22 (ILS/tonne)

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MSW, organic waste, dry household waste in MSW landfill, waste sorting residues |

107.76 |

109.05 |

109.38 |

108.73 |

111.34 |

|

Dry household waste in dry waste landfill |

71.84 |

72.70 |

72.49 |

72.49 |

74.23 |

|

Sludge in MSW landfill |

143.38 |

145.40 |

145.84 |

144.97 |

148.45 |

|

Stabilised industrial sludge |

47.89 |

48.47 |

48.61 |

48.32 |

49.48 |

|

Construction waste |

4.79 |

4.85 |

4.86 |

4.83 |

4.95 |

Source: Country submission.

In the OECD area, most countries use landfill or incineration taxes, which have been key to promote recycling of MSW. For example, in Estonia, the waste disposal tax made other treatment options more competitive and resulted in a significant decline in landfilling (OECD, 2019a). Incineration taxes for MSW are less common and tend to be lower than landfill taxes. The Netherlands has the highest incineration tax at EUR 13 per tonne (OECD, 2021d). In Denmark, the incineration tax is based on energy and CO2 content. This aims to incentivise recycling the most energy-intensive waste, such as plastics. However, incineration taxes can lead to emission leakage. For example, Norway’s incineration tax led to increased exports of waste to Sweden, which did not have such a tax. Norway’s tax, introduced in 1999, was abolished in 2010.

Taxes on raw materials, particularly for construction aggregates, could limit resource extraction and prevent waste upstream while fostering reuse and uptake of recycled aggregates downstream. Construction aggregates accounted for 78% of Israel’s DMC of non-metallic minerals in 2019. Taxes on virgin materials incentivise efficient resource use by increasing the cost of extracting and using natural resources and raw materials (OECD, 2021b). One of the few examples of such taxes in OECD member countries is Denmark’s virgin material taxes on sand, gravel, stones, peat, clay and limestone. They were introduced in 1990 and, in combination with waste taxes, increased the demand for recycled substitutes. Between 1985 and 2004, demand for recycled substitutes grew from only 12% of C&D waste being recycled to 94% (Söderholm, 2011). Although aggregate taxes have reduced natural resource use and promoted substitute materials to some extent, greater incentives for recycling are needed along with other waste management instruments (e.g. waste sorting).

2.5.3. Circular economy as a pillar of the climate mitigation policy

Within Israeli climate mitigation policy, a circular economy is seen as a pillar for reducing GHG emissions from industry. The NAPCC aims to improve resource efficiency of industry by 5% in 2030 and by 16% in 2050 relative to 2020. It presents a series of actions clustered in four main steps, one of which relates to a circular economy (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5. Circular economy is part of Israel’s climate change mitigation action plan

|

Key actions |

Beginning of implementation |

|---|---|

|

Support for energy efficiency, GHG emissions reduction and transition to clean energy sources |

2022 |

|

Support for integration of new technologies based on zero-emission energy, such as hydrogen |

2022 |

|

Support for industrial symbiosis projects |

2021 |

|

Support for the Israel Resource Efficiency Center, which advises on improving efficiency in the use of resources and raw materials |

2020 |

|

Establish a community to advance circular economy through marketing, relevant expertise and managing platforms |

2022 |

|

Adopt standards to allow use of recycled raw materials in products |

2023 |

|

Support for the recycling industry to upgrade infrastructure and increase demand |

2022 |

|

Support for pilot projects and integration of technologies for reduction at source and circular economy |

2022 |

Source: MoEP (2021a).

The National Programme for a Circular Economy in Industry aims to decouple growth and raw material consumption and prevent environmental damage from mining virgin raw materials, as well as emissions from landfilling. The programme, started in 2019, is an initiative by the Industries Administration in the MoEI. Other partners comprise the MoEP, the Manufacturers Association, the Israeli Green Building Council, the Heschel Center for Sustainability and the Innovation Authority. In 2020, the MoEP and the MoEI funded the Israel Resource Efficiency Center, which helps manufacturers increase their economic and environmental efficiency. It provides free consulting services to selected manufacturing businesses, professional guides, newsletters and training, as well as sectoral case studies offering solutions (e.g. on identifying and handling excessive energy consumption).

With support from the SwitchMed programme, the MoEP and the MoEI have defined Specifications for the Design of Sustainable Industrial Zones as guidelines for planning and developing new industrial zones in Israel. They contain measures on energy (e.g. efficiency and renewables), water and wastewater (e.g. use of constructed wetlands), transport (e.g. infrastructure for joint travel), biodiversity conservation and sustainable management. The specifications manual contains both non-binding suggestions and binding measures for planning or developing a new industrial zone.

The industrial symbiosis programme promotes productivity and reduction of waste through ecodesign. The MoEI supports the use of secondary materials in industry. It has identified a need to build 130 recycling plants to produce such materials. The ministry helps companies improve their facilities, access the international market and export their products.

A number of funding options are available for companies of all sizes that apply circular business models. The 2018 National Resource Efficiency and Environmental Innovation Programme supported companies by investing EUR 143 million in circular economy projects out of a total annual investment of EUR 756 million for environmental projects (Flanders Investment & Trade, 2019). In July 2022, the government allocated ILS 400 million for recycling and collaboration across the supply chain to help plan, design and manufacture recycled products.

The MoEP and the Israel Innovation Authority support technology start-ups at an advanced stage by offering financial and regulatory support for pilot projects, some of which are circular. Of 120 applications, 40 projects were approved (over six rounds) for a total of ILS 37 million, representing half of the project cost on average. The seventh round is now open for 2022; the start-ups will receive ILS 5.3 million. One project example relates to materials for wall coverage made of agricultural and municipal yard waste.

Finally, the MoEP is planning a fund to invest in circular economy projects, modelled on other funds that support small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Such funds include government-backed loan funds and Jewish Agency funds. This support is based on the recognition that the circular transition can be particularly slow for SMEs, many of which are family businesses with relatively conservative attitudes and limited resources. However, the size of SMEs can also be an advantage, as they can adapt more easily and integrate changes faster than larger corporations.

2.5.4. Towards a circular procurement process

Environment-related criteria have been progressively introduced into government procurement tenders, but there is no obligation to use them. In recent years, the MoEP set a target of 20% of government spending for green public procurement (GPP). To that end, it co-operates with the Purchasing Administration, Housing and Construction Administration, and Vehicles Administration under the auspices of the Ministry of Finance. In addition, the Government Procurement Administration has developed a life‑cycle costing tool. Dedicated training courses and a green procurement process forum have been set up to support public officials in the use of GPP. The government recognises a need for dialogue between suppliers and buyers, as well as with local authorities.

Procurement of single-use plastics in government offices was banned from November 2022. The MoEP identified furniture as one of the priority sectors for applying criteria related to a circular economy. However, conservative habits and poor knowledge of purchasing practices have delayed tenders and led to purchasing through exemption from tenders. Additionally, despite being a fertile territory for innovation, start-ups in environmental technology (“cleantech”) face challenges in scaling up and thus in responding to green tenders in Israel (MoEP, 2020b). While hundreds of companies operate in this sector in Israel, 75% are specialised in energy and water, not waste resources management and industrial efficiency.

Circular criteria should become an integral part of GPP in Israel. This can also support the scaling up of circular start-ups. For example, purchasing entities can consider circular business models (e.g. product as a service) rather than systematically opting for ownership (e.g. leasing vehicle fleets for public transport) (OECD, 2020b). Further efforts should also be deployed to train purchasing entities and to provide guidance to businesses participating in tenders, especially start-ups. International examples are provided in Box 2.9. OECD (2021e) identifies the following actions for the effective implementation of GPP with circular economy criteria:

Establish targets with regard to the circular economy, e.g. second-hand furniture.

Co‑ordinate across departments to analyse the potential of the circular economy, e.g. education, spatial planning, etc.

Incorporate different business models (e.g. rental, product-as-a-service models) into tenders.

Create demand in the market based on the need of the administration and allow market development: a circular solution can be developed during the duration of the contract. In other words, the company may not offer a certain service at the beginning of the contract but could work with the supplier to achieve a target (e.g. refurbish/remanufacture furniture).

Build capacity in contract management, not only in tender definition.

Develop metrics and environmental data to analyse the results.

Expand the existing public procurement regulation to assess the full life cycle of products, from design to end-of-life.

Making public procurement accessible to new entrants and SMEs carrying out circular economy activities is also important. Per the OECD Recommendation on Public Procurement (OECD, 2015), this requires providing “clear guidance to inform buyers’ expectations (including specifications and contract as well as payment terms) and binding information about evaluation and award criteria and their weights (whether they are focused specifically on price, include elements of price/quality ratio or support secondary policy objectives)”.

Box 2.9. Green public procurement can accelerate the circular economy transition

Almost all OECD countries have developed strategies or policies to support green public procurement (GPP). In the European Union, the impact of public procurement on the transition to a circular economy is worth around EUR 2 trillion, representing around 14% of gross domestic product. Some examples of GPP include circular criteria:

In its 2018 circular economy strategy, Denmark aims to develop a partnership for GPP and a forum on sustainable procurement. A task force on green procurement is planned to focus on a circular economy. It will be expanded to aim – in addition to public institutions – at private enterprises, with the additional creation of an online portal called “The responsible procurer”.

Portugal’s circular economy action plan recognises the need to implement a support structure for collaborative development of solutions that adopt circularity principles, especially in priority sectors such as construction. This support structure would entail an analysis of the integration of criteria promoting resource circularity in the list of priority goods and services established by the working groups of the National Strategy for Green Public Procurement.

Flanders, Belgium, implemented the Green Deal Circular Procurement (GDCP) between 2017 and 2019. The deal was signed by 162 companies and organisations. In total, 108 purchasing organisations, local authorities, companies, financial institutions and 54 facilitators have been involved. Throughout the initiative, GDCP signatories conducted more than 100 pilot projects on circular procurement.

In the United Kingdom, the Scottish government promoted sustainable procurement tools for life-cycle impact mapping. They considered criteria such as impacts of raw materials extraction and the reuse, recycling and remanufacture of materials.

Source: OECD (2022c, 2020b).

2.5.5. Engaging stakeholders and increasing transparency

Ensuring sustainable waste management and a transition towards a circular economy requires engaging stakeholders. To that end, stakeholders need timely information and opportunities to be involved in decision making. One example of an initiative aimed at creating a fertile environment for circular companies is the AMCHAM Circular Economy Forum launched in 2020 by the Israel-America Chamber of Commerce, Circular Economy IL and the Afeka Institute of Circular Engineering and Economy, in partnership with the MoEP and MoEI. The Forum aims to identify needs and opportunities for members to implement circular principles in their activities. It will also create and promote pilots for different types of circular solutions.

The Manufacturers Association of Israel is involved in capacity building, consulting services and information sharing. It builds capacity through circular economy workshops and training. It provides services to businesses and also directs them to relevant government initiatives. Finally, to promote industrial symbiosis among members, it shares information through a database on wastes that can be reused and/or recycled. The association has also proposed circular practices in sectors such as vehicle scrapping and helped formulate requirements and criteria for sustainable industrial zones. Beyond industry and the private sector, civil society, community-based organisations and knowledge institutions should be further engaged in decision-making processes. The combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches can foster the circular transition. The government could map relevant stakeholders groups (e.g. civil society, social enterprises, community-based organisations, knowledge institutions, local authorities, architects and designers). Armed with this list, it could establish a formal engagement mechanism, such as an advisory group, to inform circular economy policy.

Israeli consumers do not tend to attach a positive value to green products. For example, Israeli consumers are 50-60% less likely than the global average to say they would pay more for sustainable products. Regarding products as a service, Israeli consumers are also 50-60% less likely than the global average to say they would rather sign up for a membership to a product or service than pay extra to own it (Kavanagh, 2019). This indicates a need to raise awareness on the environmental consequences of consumption. The government can take inspiration from MyWaste.ie, Ireland’s information-sharing platform for waste management and circular economy for households. The platform consists of a website, a mobile phone application and social media pages. It aims to advise citizens and businesses on options for reusing, recovering and disposing of a wide range of materials. It also shares information about initiatives by local authorities and waste management stakeholders, as well as news and updates on the circular economy, resource efficiency and waste management topics.