This chapter reviews the landscape of national action plans to tackle antimicrobial resistance (AMR-NAPs) developed by OECD member countries, key partners and Group of Twenty (G20) countries. First, the chapter takes stock of the global progress in the development of AMR-NAPs and provides a discussion of factors that enable and/or hinder the implementation of these documents. Then, the chapter provides a comparative assessment of AMR-NAPs from OECD, EU/EEA and G20 countries. The findings are the result of a novel application of natural language processing techniques that make use of text from action plans. In addition, the chapter examines the selected design features of these documents. The chapter concludes by discussing the implications of the findings for the implementation of AMR-NAPs by OECD, EU/EEA and G20 countries.

Embracing a One Health Framework to Fight Antimicrobial Resistance

4. Special focus: Assessing the landscape of national action plans on antimicrobial resistance

Abstract

Key findings

Taking stock of the global progress in the development of national action plans to tackle AMR

The publication of the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR-GAP) in 2015 augured well for the development of national action plans to tackle AMR (AMR-NAPs). Globally, the share of countries with an AMR-NAP more than doubled, reaching 149 in 2021‑22 from 70 in 2017. However, only around 10% (17/166) of countries globally reached the final stage of implementation, which entails including financial provisions for the implementation of AMR‑NAPs in the national action plans and budgets.

In 2021‑22, about 92% (47/51) of OECD countries and key partners, European Union (EU) or European Economic Area (EEA) members and G20 countries finished developing their action plans. However, only 20% (10/51) of these countries advanced to the final stage of the implementation of their AMR-NAPs, which involves including financial provisions for the implementation of AMR-NAPs in national action plans and budgets.

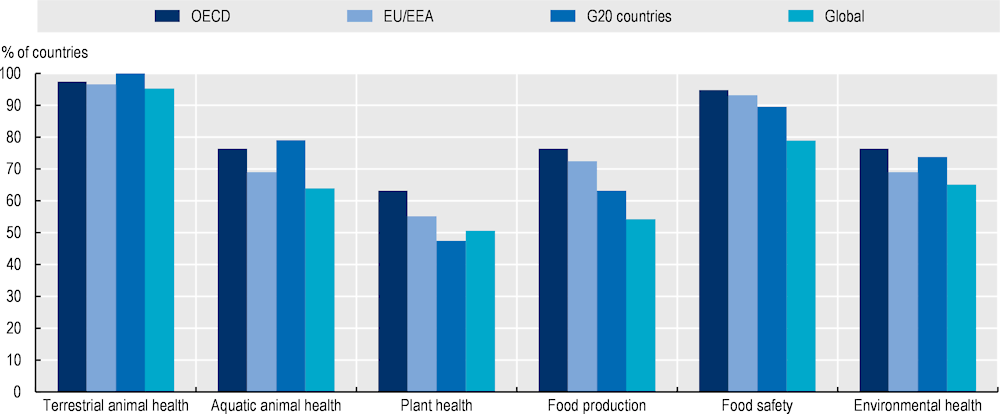

Among OECD countries, key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, there are gaps in the implementation of One Health approaches that entail the active involvement of multiple sectors in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs. In these countries, the animal sector actively contributed to the development and implementation of nearly all of the AMR-NAPs in 2021‑22. This is followed by the food safety and the environmental sectors, which played an active role in the development and implementation of 90% (46/51) and 71% (36/51) of AMR‑NAPs respectively. In comparison, the food production and the plant health sectors were actively engaged in the development and implementation of 75% (38/51) and 59% (30/51) of action plans respectively.

Nearly all OECD countries, EU/EEA and G20 countries put in place AMR-relevant multi-sectoral policies consistent with the AMR-GAP. However, there are notable gaps in the implementation of interventions relevant to: optimising antibiotic use in human and animal health; monitoring antibiotic use and AMR surveillance; scaling up infection prevention and control programmes; scaling up nationwide activities to raise AMR awareness; incorporating AMR in the training and education of human healthcare professionals; and implementing good management and hygiene practices in farms and food establishments.

In 2020, the Group of Seven (G7) and OECD countries remained the primary source of development assistance for health (DAH) allocated to AMR, provided as financial and in-kind contributions transferred through international development institutions. Nonetheless, the current levels of DAH for AMR remain at around 2% and domestic sources of financing for AMR are unlikely to fill the existing funding gaps in low-resource settings.

Assessing the content of AMR-NAPs from 21 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries

On average, AMR-NAPs from the 21 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries cover a span of five years. Many AMR-NAPs predate the publication of the AMR‑GAP in 2015, while others are nearing the end of the period that they cover.

There is little cross-country standardisation in the ways in which OECD countries assess their progress towards the goals that they state in their AMR-NAPs, making it difficult to compare cross-country performance over time.

Only 12 out of 21 AMR-NAPs from OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries discuss budgetary considerations and less than half refer to the cost-effectiveness of AMR-relevant interventions.

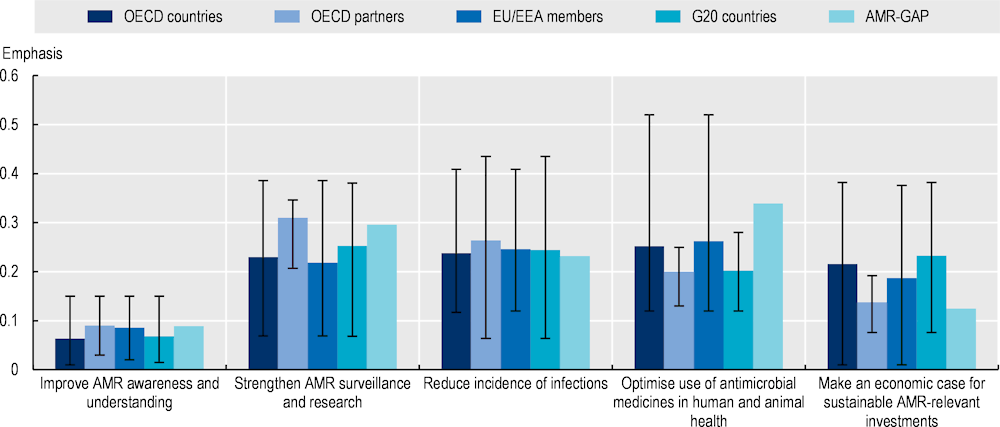

A high degree of convergence is observed between AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP in terms of their strategic objectives. Much like the AMR-GAP, optimising the use of antimicrobials in human and animal health is estimated to be the most frequently featured strategic objective in AMR‑NAPs from OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, followed by strengthening AMR surveillance, reducing the incidence of infections and making an economic case for sustainable investments. In comparison, improving awareness and understanding of AMR is the least frequently discussed strategic objective in these documents.

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries discuss a wide range of AMR-relevant interventions to achieve their strategic priorities, reflecting the broader historical, socio‑economic and health system-related factors that shape the AMR agenda in each setting.

With respect to strategies to optimise antimicrobial use in human and animal health, OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries primarily emphasise efforts to strengthen antimicrobial stewardship. Further improvements can be achieved by improving the availability of antibiotic prescribing guidelines beyond hospital and acute care settings, encouraging the use of older antimicrobials and scaling up electronic prescribing programmes.

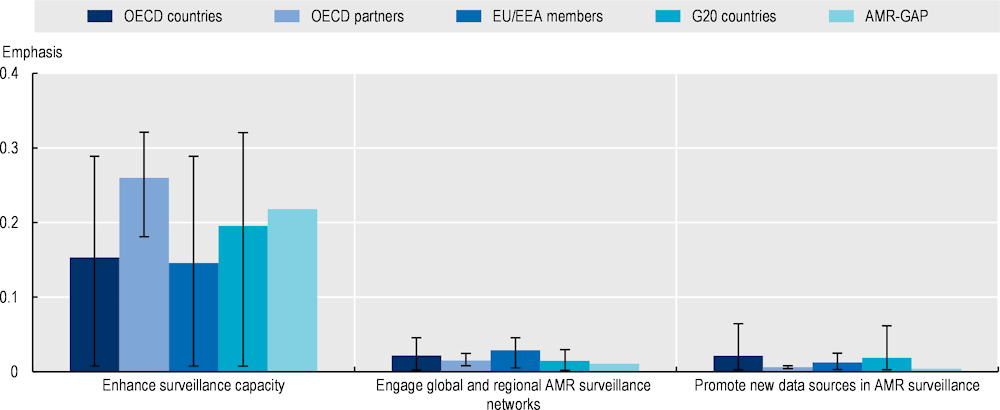

While the importance of strengthening AMR surveillance is recognised in the AMR-NAPs from 21 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, these countries will benefit from deepening their engagement with global and regional AMR surveillance networks, enhancing laboratory network capacity and integrating information from new data sources into AMR surveillance.

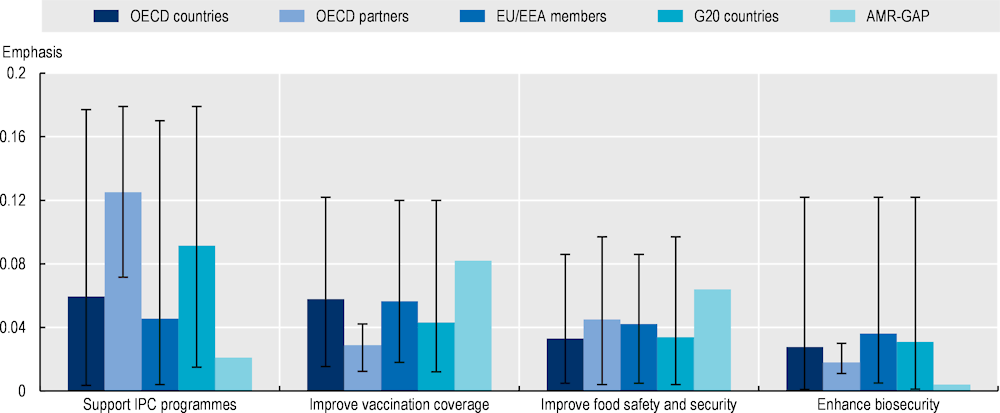

In terms of reducing the incidence of infections, the AMR-NAPs from 21 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries most frequently emphasise the importance of improving water, sanitation, hygiene and waste management practices and vaccination coverage in human health. There is a need to put more emphasis on veterinary vaccines and enhancing biosecurity.

In terms of strategies to spur AMR-related research and development (R&D), OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries primarily focus on a range of incentives aiming to encourage the early stage of drug development, whereas emerging evidence points to the need to supplement these incentives with those that can help improve expectations around future revenues.

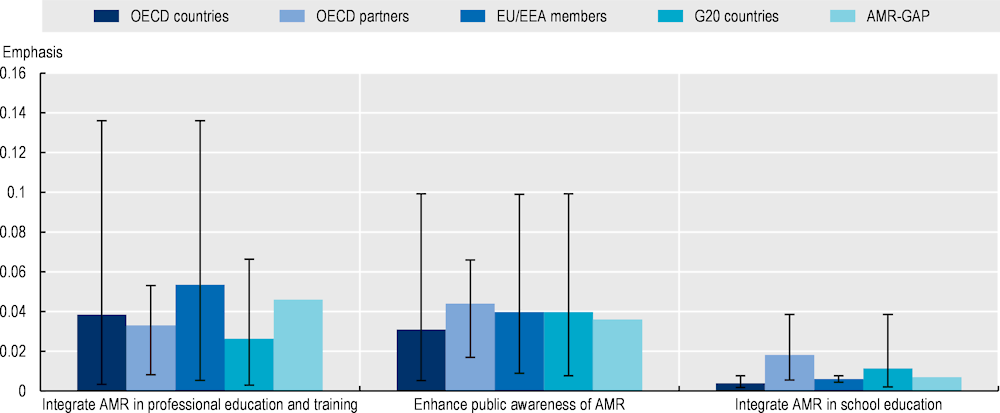

With respect to strategies to enhance AMR awareness and understanding, the selected AMR-NAPs frequently highlight interventions targeting medical professionals and the general public while less emphasis is given to interventions targeting young children.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a well-recognised global health challenge

In recent years, the global community made important strides to tackle AMR. In May 2015, all members of the World Health Organization (WHO) made a commitment to tackling AMR by adopting the Global Action Plan (AMR-GAP) (WHO, 2015[1]). The AMR-GAP articulated five strategic objectives (Box 4.1) and urged countries to develop their own AMR national action plans (AMR-NAPs) in line with these strategic objectives, as well as the standards and guidelines championed by other intergovernmental bodies like the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) and the Codex Alimentarius Commission.

Box 4.1. A multi-pronged approach to curtailing AMR highlighted in the AMR-GAP involves five strategic objectives

Source: WHO (2015[1]), Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance, https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/193736.

Following the publication of the AMR-GAP, global efforts to tackle AMR gained momentum. In 2016, the members of the United Nations (UN) reaffirmed their commitment to the vision laid out in the AMR-GAP in the UN Political Declaration on AMR (UN, 2016[2]). The following year, G20 countries endorsed the AMR‑GAP and called for the development of a global AMR R&D collaboration hub, which was launched in 2018. In 2019, the UN Ad Hoc Interagency Co‑ordination Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (ICGAR) issued an urgent call to establish a One Health Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (WHO, 2019[3]). In 2020, AMR was highlighted as one of the five priority areas for global action in the WHO Thirteenth General Program of Work (2019‑23) to improve population health and well-being (WHO, 2020[4]). This programme of work included one indicator – the proportion of bloodstream infections due to resistant organisms – as part of 46 key performance indicators to track progress by 2023 (WHO, 2020[4]). Importantly, many of these efforts have fostered collective, multi-sectoral action widely referred to as the One Health framework (Box 4.2). In 2022, the WHO, FAO, WOAH and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) published a new framework which describes the background and context of collaboration to tackle AMR and presents a theory of change associated with collaboration across agencies, including goals and objectives, desired country-level impact, intermediate outcomes, assumptions and risks, and implementation arrangements (WHO et al., 2022[5]).

Box 4.2. The COVID‑19 pandemic brought renewed attention to the One Health approach

A key principle embedded in the AMR-GAP is a collaborative, interdisciplinary, multi-sectoral action, referred to as the One Health approach. This approach recognises that many of the antimicrobial threats to human health are the same as those afflicting the health of animals and plants that share the same ecosystem (FAO and WHO, 2021[6]). It underscores the importance of pairing policies in the human health sector with those that are targeting the drivers of AMR in the animal and plant population, agricultural production, food safety and security, and environmental sectors.

Prior to the advent of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the importance of the One Health framework was demonstrated time and again, with the emergence and spread of zoonotic viruses. In 2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), caused by a novel coronavirus, spread rapidly across 29 countries in the Americas, Asia and Europe. Following the 2003 SARS epidemic, other zoonotic viruses undermined the performance of health systems across the globe, including the re‑emergence and rapid spread of the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 in 2013, the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, Zika in 2014‑17 in the Americas and the Pacific regions, and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome that emerged in 2012. Despite these experiences, the Independent Panel, which was convened at the request of the WHO World Health Assembly, concluded that the One Health framework has been overlooked in efforts to prepare for future health crises (The Independent Panel, 2021[7]).

Today, a new reality is at hand. At the writing of this chapter, the global COVID‑19 infections surpassed 770 million confirmed cases and the attributable death toll reached nearly 7 million (Our World in Data, 2023[8]). Much like past pandemics, the COVID‑19 outbreak put additional strain on health systems across the globe. Mounting evidence pointing to delays and disruptions in non-COVID19 healthcare provision (Chmielewska et al., 2021[9]; Harris et al., 2021[10]) and interruptions in the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship policies and AMR surveillance (Tomczyk et al., 2021[11]). Echoing calls from numerous international bodies, the Independent Panel strongly urged countries to embed the One Health framework as an integral part of their efforts to plan and prepare for future health emergencies (The Independent Panel, 2021[7]).

Source: Chmielewska, B. et al. (2021[9]), “Effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: A systematic review and meta‑analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(21)00079-6; Harris, R. et al. (2021[10]), “Impact of COVID‑19 on routine immunisation in South-East Asia and Western Pacific: Disruptions and solutions”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100140; The Independent Panel (2021[7]), COVID‑19: Make It the Last Pandemic, https://theindependentpanel.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/COVID-19-Make-it-the-Last-Pandemic_final.pdf; Our World in Data (2023[8]), Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID‑19), https://ourworldindata.org/COVID-deaths (accessed on 15 January 2022); Tomczyk, S. et al. (2021[11]), “Impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the surveillance, prevention and control of antimicrobial resistance: A global survey”, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkab300.

The goal of this chapter is to review the AMR-NAP landscape in OECD members, key partners and G20 countries. As the first of the two policy chapters included in this publication, it starts by documenting the global progress in the development of AMR-NAPs and describes the factors that enable or hinder the implementation of these documents. Data used for this analysis come primarily from the most recent wave of the Tripartite AMR Country Self-Assessment Surveys conducted by the WHO, WOAH and FAO in 2020‑21 (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). Next, the chapter takes a deep dive into the content of 21 AMR-NAPs selected among OECD and G20 countries. To do this, the chapter provides new evidence on the selected design features of the AMR-NAPs that may influence the effectiveness of the implementation of the vision set out in these documents. Next, the chapter assesses the level of alignment between the AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP. Complementing this analysis, Chapter 5 then provides an overview of emerging evidence on the effectiveness of selected AMR interventions.

Global progress in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs

Key messages

Globally, the number of countries with AMR-NAPs more than doubled since 2016‑17, reaching 149 countries in 2021‑22. Yet only 17 out of 166 countries indicated that they included financial provisions for the implementation of their AMR-NAPs in the national action plans and budgets.

Forty-seven out of 51 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries developed AMR-NAPs, but only 20% (10/51) of these countries indicated that they advanced to the final stage of implementation, which involves including financial provisions for the implementation of AMR-NAPs in national action plans and budgets.

In line with the One Health approach, in all OECD members, EU/EEA and G20 countries, the animal sector was actively involved in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs in 2021‑22. However, there are gaps in multi-sectoral action. In 2021‑22, the development and implementation of around 90% (46/51) of action plans from these countries involved the active participation of the food safety sector, whereas 71% (36/51) involved the environmental sector. In this period, the food production and plant health sectors actively contributed to the development and implementation of around 75% (38/51) and 59% (30/51) of the AMR-NAPs respectively.

Globally, the implementation of AMR-NAPs is marked by a socio‑economic development gradient. The current level of development assistance for health devoted to AMR is unlikely to make up for insufficient funding from domestic resources in resource‑constrained settings.

Globally, there has been notable progress in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs but gaps remain in the existing arrangements for including financial provisions for the implementation of AMR-NAPs in national action plans and budgets

The launch of the AMR-GAP in 2015 augured well for the development of AMR-NAPs across the globe, though many countries grapple with challenges in the execution of their action plans. The number of countries with AMR-NAPs more than doubled since 2016‑17, reaching 149 countries in 2021‑22 (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). Despite this, only 10% (17/166) of action plans proceeded to the most advanced stage of implementation in 2020‑21, which involves the inclusion of financial provision for AMR-NAPs in the national plans and budgets (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). These findings are consistent with a recent discussion paper by the UN ICGAR, which showed that most countries face challenges in the execution of their AMR‑NAPs rather than the development of these documents (ICGAR, 2018[13]).

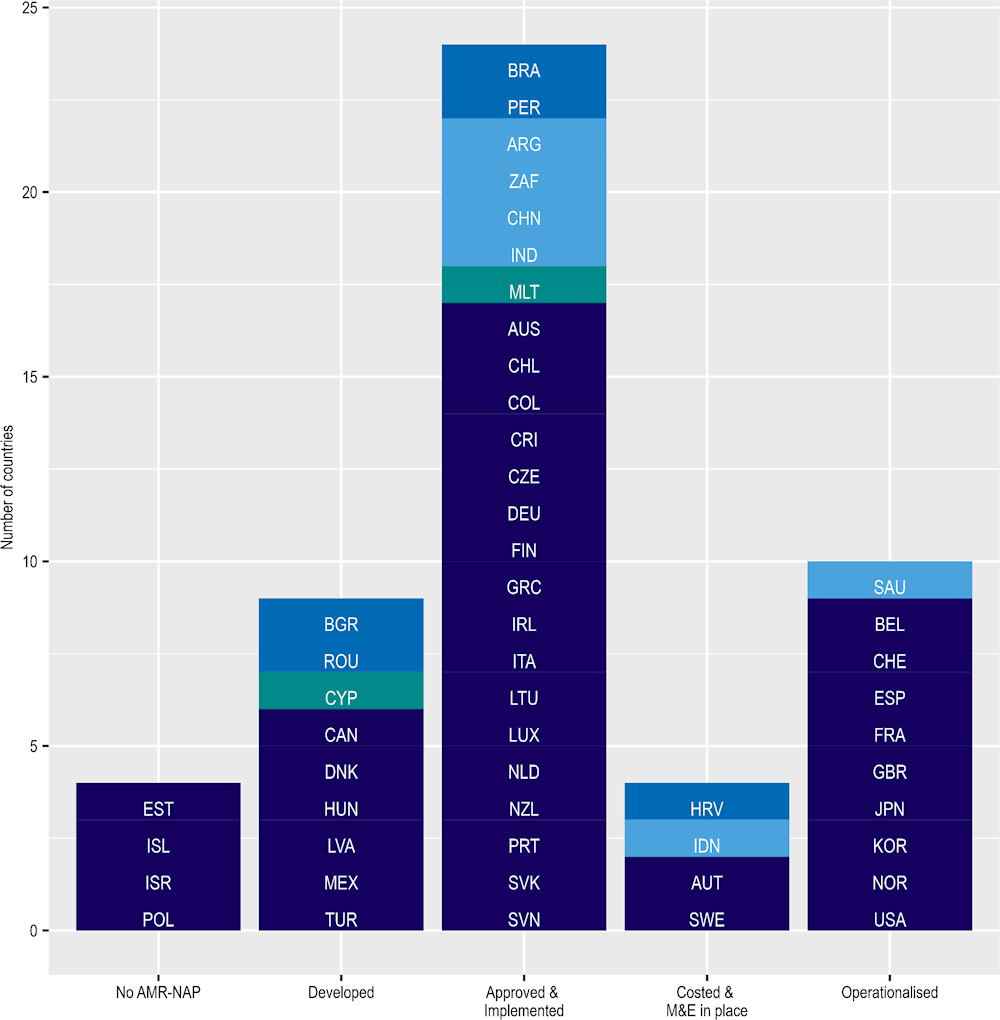

AMR remains prominent in the public health agenda in OECD , EU/EEA and G20 countries but challenges persist (Figure 4.1). In 2021‑22, about 92% (47/51) of OECD countries, key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries finished developing their AMR-NAPs. However, the majority of these countries have not yet proceeded to the most advanced stage of implementation. In 2021‑22, only around 20% (10/51) of these countries proceeded to the final stage of implementation, where financial provisions for the implementation of AMR-NAPs were included in the national plans and budgets (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). Importantly, many OECD countries reported that the AMR-relevant activities that they highlighted in their AMR-NAPs have been adversely impacted by the COVID‑19 pandemic (Box 4.3).

Figure 4.1. Most countries developed an AMR-NAP but further progress is needed to strengthen financial provisions to support implementation

Note: Dark blue = OECD countries; medium blue = OECD accession countries; light blue = non-OECD G20 countries; green = non-OECD EU/EEA countries. The figure above describes the stages of the development of AMR-NAPs in five steps: i) No AMR-NAP: No AMR-NAP action plan; ii) Developed: AMR-NAP has been developed; iii) Approved& Implemented: AMR-NAP approved by government and is being implemented; iv) Costed & M&E in place: AMR-NAP has a costed and budgeted operational plan and has monitoring mechanism in place; v) Operationalised: Financial provision for the National AMR action plan implementation is included in the national plans and budgets.

Source: WHO/FAO/WOAH (2022[12]), Tripartite AMR Country Self‑Assessment Survey (TrACSS) 2021‑2022, https://amrcountryprogress.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2022).

Box 4.3. In many OECD countries, the implementation of AMR-relevant programmes and activities has been impacted by the COVID‑19 pandemic

In many OECD countries, the implementation of many AMR-relevant initiatives featured in national action plans has been disrupted by the COVID‑19 pandemic

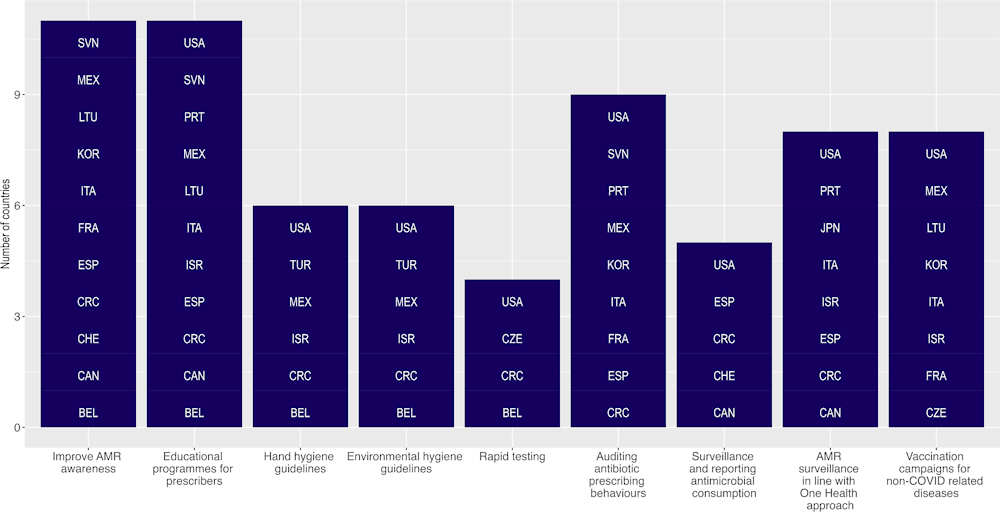

As shown in Figure 4.2, the implementation of a wide range of activities highlighted in AMR-NAPs of many OECD countries has been disrupted by the COVID‑19 pandemic. Evidence emerging from OECD countries suggests that the re‑prioritisation of resources to address the COVID‑19 pandemic may have adversely impacted the implementation of the AMR agenda. Of the 26 OECD countries that participated in the OECD Resilience of Health Systems questionnaire (OECD, 2023[14]), 11 countries indicated that activities to improve AMR awareness and understanding in the general public and educational programmes for antibiotic prescribers were disrupted due to the pandemic. Further, disruptions were reported by nine OECD countries in terms of monitoring antibiotic prescribing behaviours in healthcare facilities. In addition, eight OECD countries reported interruptions in AMR surveillance in line with the One Health framework, as well as disruptions in vaccine campaigns for non-COVID‑19 related health conditions. OECD countries also reported interruptions in the rapid testing of patients and disruptions in the compliance of health workers with the existing hand hygiene and environmental hygiene guidelines in healthcare facilities. In addition, many OECD countries indicated that they were forced to delay revising/updating their AMR-NAPs due to the COVID‑19 pandemic while others suggested that final approval and budget allocation of the full implementation of AMR-NAPs were impacted.

Figure 4.2. AMR-relevant activities and programmes were adversely impacted by COVID‑19

Source: Analysis of OECD (2023[14]), Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience, https://doi.org/10.1787/1e53cf80-en.

OECD countries have been actively pursuing approaches to limit the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the implementation of their AMR-NAPs

Many OECD countries employed strategies to limit the impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on the implementation of their AMR-NAPs. For example, in Belgium, hospitals were given extra financial resources to support their ongoing antimicrobial stewardship programmes and infection prevention and control interventions. In Portugal, regional AMR teams maintained close contact with local hospitals to avoid major disruptions in the already existing AMR measures. In Korea, online educational programmes were used to support the management of AMR policies. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one of the federal agencies leading the AMR agenda, continued to highlight AMR as a top priority by continuing investments in various prevention strategies, including early detection and containment, and infection prevention and control.

Source: Analysis of OECD (2023[14]), Ready for the Next Crisis? Investing in Health System Resilience, https://doi.org/10.1787/1e53cf80-en.

Globally, socio‑economic disparities exist in the implementation of AMR-NAPs

A socio‑economic development gradient emerges in the implementation of AMR-NAPs. In 2021‑22, among high-income countries (HICs), about 20% of AMR-NAPs advanced to the final stage of implementation, compared to 7% in upper-middle‑income countries (UMICs) and in lower-middle‑income countries (LMICs) and none of the low-income countries (LICs) (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). While the evidence base that can help explain these discrepancies remains limited, previous works from low-resource settings point to the deficits in technical capacity and staffing, institutional bottlenecks that hinder efforts to scale up local efforts (ICGAR, 2018[13]) and the differences in the governance approach to managing AMR (Birgand et al., 2018[15]).

Insufficient funding devoted to AMR is another bottleneck. A recent Wellcome Trust analysis concluded that financial limitations present a major impediment to implementing AMR-NAPs in many LMICs. Even when these countries identify funding to support the implementation of their AMR-NAPs, the level of funding may be insufficient to cover all of the intended activities (Wellcome, 2020[16]). In addition, access to high-quality drugs remains a challenge in many LMICs (Hauk et al., 2020[17]), which can exacerbate the emergence of drug-resistant pathogens. In recognition, new pooled funding mechanisms have emerged in recent years to overcome these financial constraints (Box 4.4).

Box 4.4. In the last two decades, the Global Drug Facility (GDF) of the Stop Tuberculosis (TB) Partnership contributed to improving access to quality-assured TB drugs across the globe

In 2020, an estimated 10 million people globally suffered from TB, a substantial proportion of which are multidrug resistant (WHO, 2021[18]). LMICs bear a considerable share of the TB burden worldwide (WHO, 2021[18]). Despite this, about 10% of all medicines in LMICs are considered poor-quality or counterfeit (Hauk et al., 2020[17]). Reliance on poor-quality anti-TB drugs not only decreases the likelihood of successful recovery but also promotes the emergence of drug-resistant TB pathogens. Exacerbating these challenges, many LMICs alone have limited negotiation power to reduce the price of TB drugs, even though patents for many of these drugs have already expired (Arinaminpathy et al., 2013[19]).

Recognising these challenges, the GDF was founded in 2001 as an alternative procurement model to help address issues around low-quality anti-TB drugs. The GDF was designed to ensure countries have equitable and uninterrupted access to high-quality medicines, and pools funds from donors and national governments. By consolidating demand for TB drugs from different countries, it negotiates the price of quality-assured TB medicines directly with drug suppliers (Arinaminpathy et al., 2013[19]). It also provides technical assistance, supply management tools and capacity-building tools to accelerate access to and take up of new TB products in resource‑constrained settings.

Today, the GDF is the world’s largest provider of TB-related drugs and diagnostics used in a variety of government-administered TB programmes, as well as TB programmes administered by international agencies (Hauk et al., 2020[17]). Since its launch, the GDF services were utilised by 151 countries to increase access to quality-assured TB diagnostics and treatments (Stop TB Partnership, 2021[20]). In 2020, the value of first-line and second-line medicines procured by the GDF reached USD 108 million and USD 141 million respectively, whereas the value of diagnostics reached USD 57.9 million (Stop TB Partnership, 2021[20]).

Source: Arinaminpathy, N. et al. (2013[19]), “The Global Drug Facility and its role in the market for tuberculosis drugs”, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60896-x; Hauk, C. et al. (2020[17]), “Quality assurance in anti-tuberculosis drug procurement by the Stop TB Partnership – Global Drug Facility: Procedures, costs, time requirements, and comparison of assay and dissolution results by manufacturers and by external analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243428; Stop TB Partnership (2021[20]), GDF Results, https://www.stoptb.org/mission/gdfs-results (accessed on 30 March 2022); WHO (2021[18]), Tuberculosis – Factsheet, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis (accessed on 30 March 2022).

G7 and OECD countries are committed to mobilising development assistance for health (DAH) allocated to AMR but the current level of financial assistance is unlikely to address the existing gaps in domestic funding in resource‑constrained settings

In recent years, AMR has been reframed as a public health issue with important consequences for socio‑economic development in resource‑constrained settings. In 2018, the ICGAR suggested that AMR is not perceived as a priority issue in many LMICs (2018[13]). The publication analysis indicated that this perception may limit access to development funding and projects. The following year, the World Bank highlighted the need for reframing AMR not only as a public health challenge but also as a global development issue by arguing that AMR has far-reaching implications for human capital in developing countries, and failing to curb the AMR burden may impede progress towards United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2019[21]).

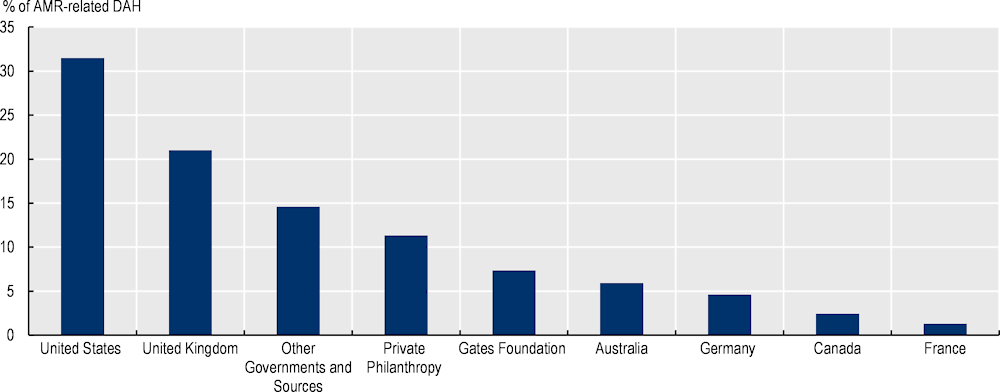

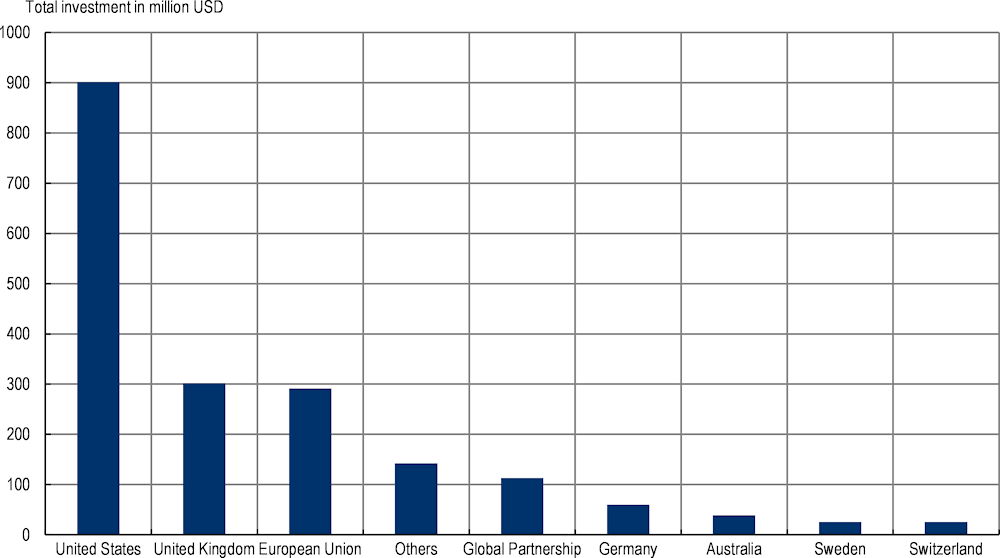

G7 and OECD countries remain steadfast in their commitment to financing AMR-related activities across the globe but the current level of development funding allocated to AMR is unlikely to fill the existing gaps in domestic funding (Figure 4.3). In 2020, G7 and OECD countries were the leading sources of DAH allocated to AMR, including Australia, France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States (IHME, 2021[22]). Yet, the current level of DAH allocated to AMR remains low, with AMR receiving close to around 2% of DAH dedicated to communicable diseases in 2019. Considering that many countries across the globe are marshalling financial resources to address the COVID‑19 pandemic, the current level of DAH for AMR is unlikely to make up for the funding gap in low-resource settings.

Figure 4.3. G7 and OECD countries are still committed to financing AMR activities across the globe, 2019

Source: IHME (2021[22]), Flows of Development Assistance for Health, https://vizhub.healthdata.org/fgh/ (accessed on 15 September 2021).

While the animal health sector is actively involved in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs in most countries, further advancements are needed to incorporate input from other sectors

The period following the publication of the AMR-GAP has seen improvements in the number of countries that sought multi-sectoral feedback while developing their AMR-NAPs. In 2021‑22, globally, more than 1 sector was actively involved in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs in about 98% (162/166) of countries (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). Similarly, in all OECD countries, EU/EEA and G20 countries, at least two sectors actively participated in the development and implementation of action plans in 2021‑22 (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). This finding is in congruence with earlier studies which showed that most countries across the globe adopted some form of multi-sectoral approach in the development and implementation of their AMR-NAPs (Munkholm et al., 2021[23]).

Yet, the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs do not always entail the active involvement of all relevant sectors (Figure 4.4). The linkages between human and animal health appears to be well recognised. In 2021‑22, in nearly all (165/166) of countries that reported data to the Tripartite AMR Country Self-Assessment Survey, the process to develop and implement AMR-NAPs actively involved the terrestrial animal health sector and, in 96% (158/166) of countries, this process involved the health of aquatic animals. Yet only a fraction of AMR-NAPs, globally, were developed and implemented with the active involvement of the other sectors. In 2021‑22, the development and implementation of about 79% (131/166) of AMR-NAPs involved the food safety sector, whereas 65% (108/166) involved the environment, 55% (90/166) food production and only 51% (84/166) reflected the active involvement of the plant health sector (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]).

Across OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, stakeholders from the animal health sector most commonly take an active role in the development and implementation of AMR‑NAPs, whereas stakeholders representing food safety and security, the transmission of AMR in the environment and plant health are less involved. In 2021‑22, animal health was nearly universally acknowledged in the AMR-NAPs by OECD members and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries. In comparison, in around 90% (46/51) of these countries, the development and implementation of action plans involved the active participation of the food safety sector (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). Similarly, the environment sector was actively involved in the development and implementation of around 71% (36/51) of action plans. In the same period, the food production and plant health sectors were actively involved in the development and implementation of 75% (38/51) and 59% (30/51) of AMR-NAPs respectively.

Figure 4.4. The animal sector is the main non-human health sector routinely involved in the development and implementation of AMR-NAPs

Note: EU: European Union; EEA : European Economic Area; G20: Group of Twenty.

Source: WHO/FAO/OEI (2022[12]), Tripartite AMR Country Self‑Assessment Survey (TrACSS) 2020‑2021, https://amrcountryprogress.org (accessed on 4 December 2022).

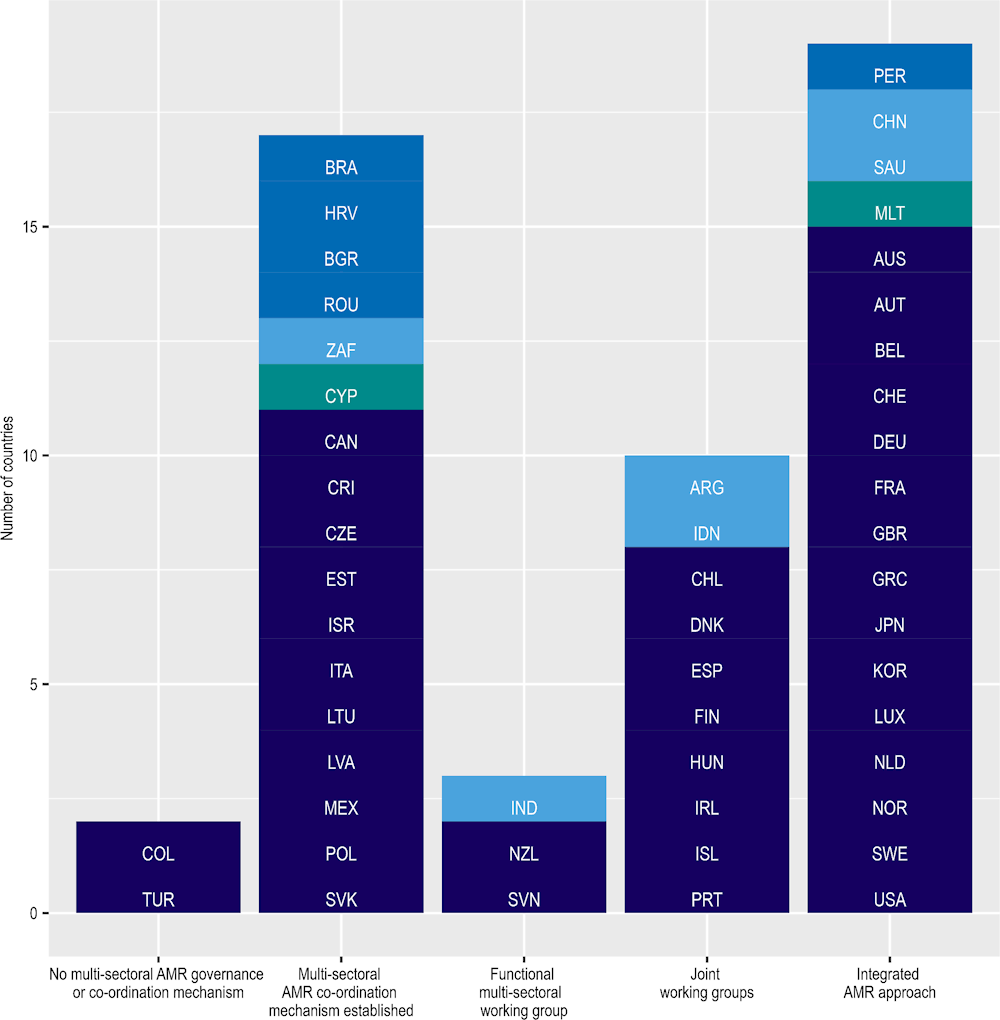

Globally, important strides have been made in building multi-sectoral co‑ordination mechanisms to support multi-sectoral approaches to tackling AMR (Figure 4.5). Establishing multi-sectoral co‑ordination mechanisms is an important first step towards facilitating multi-sectoral AMR response (Box 4.5). Globally, 87% (144/166) of countries established some form of a formal multi-sectoral governance or co‑ordination mechanism on AMR 2021‑22 (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]). In 2021‑22, nearly all OECD countries, key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries (49/51) put in place some form of multi-sectoral co‑ordination mechanism (i.e. working groups/co‑ordination committees) to promote multi-sectoral AMR‑relevant policy development and implementation. Importantly, new multinational initiatives emerged to promote multi-sectoral action across countries (Box 4.6). While relatively little is known about the factors that influence the effectiveness of multi-sectoral co‑ordination mechanisms, limited evidence suggests that various factors may influence the co‑ordination of multi-sectoral action including political will, administrative and financial support, as well as the dearth of available AMR data that can be used to facilitate dialogue and varying priorities across stakeholders (Joshi et al., 2021[24]).

Figure 4.5. Many OECD countries rely on integrated-approaches to implement their AMR-NAPs

Note: Dark blue = OECD countries; medium blue = OECD accession countries; light blue = non-OECD G20 countries; green = non-OECD EU/EEA countries. The figure above describes the stages of multi-sectoral collaboration: i) No multi-sectoral AMR governance or co‑ordination mechanism; ii) Multi-sectoral AMR co‑ordination mechanism established: Multi-sectoral AMR co‑ordination mechanisms are established with government leadership; iii) Functional multi-sectoral working group: Formalised multi-sector co‑ordination mechanism with technical working groups established with clear terms of reference, regular meetings and funding for working group(s) with activities and reporting/accountability arrangements defined; iv) Joint working groups: Joint work on issues including agreement on common objectives; v) Integrated AMR approaches: Integrated approaches are used to implement the AMR-NAP with relevant data and lessons learnt across sectors used to adapt implementation of AMR-NAP.

Source: WHO/FAO/WOAH (2022[12]), Tripartite AMR Country Self‑Assessment Survey (TrACSS) 2021‑2022, https://amrcountryprogress.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2022).

Box 4.5. Co‑ordinating multi-sectoral collaboration and co‑operation for AMR-relevant action in the United States

In the United States, the government’s Interagency Task Force for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (CARB) remains the key driver of multi-sectoral collaboration and co‑ordination and that co‑ordination enabled the development of the updated AMR-NAP, as well as the implementation of CARB work in general (CARB, 2020[25]). Established in 2015, the CARB Task Force is co-chaired by the Secretaries of the US Departments of Health and Human Services, Agriculture and Defence, as well as representatives from the Departments of the Interior, State, and Veterans Affairs, the Environmental Protection Agency, the US Agency for International Development, the National Science Foundation, as well as representatives from the Executive Office of the President (CARB, 2020[25]). The Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation is tasked with the co‑ordination of the CARB Task Force, as well as the development of annual progress reports, and led the development of the 2020 AMR-NAP (CARB, 2020[25]). The CARB Task Force meets on a quarterly basis to discuss the ongoing work and reports annually on the progress toward goals stated in the AMR‑NAP.

The CARB Task Force recruited more than 100 federal experts from multiple disciplines to work as part of cross-agency teams that helped develop the goals included in the US AMR-NAP published in 2020. Each cross-agency team was comprised of experts from multiple disciplines (e.g. experts on human health surveillance and experts on animal health surveillance). The process to develop the goals included in the 2020 AMR-NAP entailed several steps. First, reviews of the progress towards each milestone highlighted in the previous AMR-NAP dated 2015 were carried out. These reviews looked at the progress in the implementation of actions associated with each milestone, identified both the challenges that had been experienced and opportunities that had risen since 2015, and pointed out the challenges and opportunities that are anticipated in the future. Subsequently, the cross-agency teams proposed, reiterated and refined new objectives and targets included in the 2020 AMR-NAP.

Source: CARB (2020[25]), National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic‑Resistant Bacteria 2020‑25, https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/carb-national-action-plan-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2022).

Box 4.6. The EU Strategic Approach to addressing pharmaceuticals in the environment rests on multi-sectoral action

In March 2019, the EU member states adopted a common approach to addressing the presence of pharmaceuticals in the environment, including antimicrobials (European Commission, 2019[26]). The EU approach recognises that the presence of antimicrobials used in human and veterinary medicine found in water and soil systems may contribute to the development, maintenance and spread of resistant pathogens. Aligned explicitly with the objectives of the European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance, the EU approach lays out six strategic priority areas for action that cover the lifecycle of pharmaceuticals:

Increase awareness and promote prudent use of pharmaceuticals, including antimicrobials.

Support the development of pharmaceuticals intrinsically less harmful to the environment and promote greener manufacturing practices.

Improve environmental risk assessment and its review.

Reduce wastage and improve waste management.

Expand environmental monitoring.

Fill other knowledge gaps, including the links between the presence of antimicrobials in the environment and the development and spread of AMR.

Since 2019, notable progress has been made in the implementation of the EU strategic approach. For instance, ministers of health in the EU member states started considering options that can help promote the consideration of the environmental impacts of medicines in the prescription decisions of health professionals (European Commission, 2020[27]). Another initiative led by the ad hoc working group through the Pharmaceutical Committee for human medicines was an agreement towards sharing best practices among health professionals across EU member states to promote environmentally safe disposal of medicinal products and clinical waste, as well as the ways in which pharmaceutical residues can be collected in an environmentally safe manner (European Commission, 2020[27]).

Source: European Commission (2019[26]), European Union Strategic Approach to Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-dangersub/pdf/strategic_approach_pharmaceuticals_env.PDF; European Commission (2020[27]), Update on Progress and Implementation: European Union Strategic Approach to Pharmaceuticals in the Environment, https://ec.europa.eu/environment/water/water-dangersub/pdf/Progress_Overview%20PiE_KH0320727ENN.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

Gaps exist in the implementation of AMR-relevant multi-sectoral policies consistent with the AMR-GAP

Table 4.1 provides a dashboard of AMR-relevant multi-sectoral policies implemented in OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries in congruence with the AMR-GAP based on responses provided by countries in the latest round of the Tripartite AMR Country Self-Assessment Survey (2021‑22) (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2022[12]) (Annex 4.A provides more detailed information on the methodology used to develop the dashboard). Findings emerging from this dashboard point to important gaps in implementation:

In nearly all OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, there are national policies for antimicrobial governance that pertains to the community and healthcare settings. However, only eight of these countries currently have in place guidelines for optimising antibiotic use in human health for all major syndromes, with data on antibiotic use shared back with prescribers in a systematic manner.

In nearly all OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, a national policy or legislation exists to regulate the quality, safety and efficacy of antimicrobial productions used in terrestrial and aquatic animal health, as well as their distribution sale or use. But, only in 18 of these countries, enforcement and control mechanisms are reportedly in place to ensure compliance with the existing policy or legislation.

Nearly all OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries have a national plan or system for monitoring antimicrobial use in their own settings. But only 26 of these countries regularly collect and report data on antimicrobial sales and consumption at the national level for human use, and data on antibiotic prescribing and appropriate/rational antibiotic use are drawn from a representative sample of health facilities in the public and private sectors.

All OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries reported having the capacity to: i) generate data on antibiotic susceptibility testing, as well as related clinical and epidemiological data; and ii) report AMR. However, only 14 of these countries have a national AMR surveillance system that links AMR surveillance with antimicrobial consumption and/or use data in the human health sector.

23 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries reported that infection prevention and control (IPC) programmes are in place and functioning at the national and health facility levels in line with the WHO IPC core components. In these countries, compliance and effectiveness are regularly evaluated and published, and guidance is updated in accordance with monitoring.

All OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries promote AMR awareness, but only nine of these countries have in place routine targeted, nationwide, government-supported activities to raise AMR awareness to facilitate behaviour change among priority stakeholders, with regular monitoring of these activities.

All OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries provide training and professional education opportunities to raise awareness of AMR among health professionals in the human health sector, though only eleven of these countries systematically incorporate AMR in pre‑service training curricula for all relevant human health cadres, and in-service training and other professional education opportunities are taken up by relevant groups for the human health sector in public and private sectors.

All OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries reported having in place some systematic efforts to improve good animal husbandry and biosecurity practices in terrestrial animal health. But only eight of these countries monitor the implementation of their nationwide plans periodically. Similarly, 43 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries make systematic efforts to improve good practices for aquatic animals and only six of these countries monitor the implementation of their nationwide plans regularly.

Forty-eight OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries reported having in place some mechanisms to improve good practices in food processing. However, only ten of these countries monitor the implementation of their nationwide action plans periodically.

Table 4.1. Dashboard on the implementation of selected AMR-relevant policies in OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries

|

Country |

Optimising antimicrobial use in human health |

Optimising antimicrobial use in animal health |

National monitoring system for consumption and rational use of antimicrobials in human health |

National surveillance system for AMR in humans |

Strengthening IPC practices in human healthcare |

Raising AMR awareness and understanding |

Training and education on AMR in human health |

Biosecurity and good animal husbandry practices (terrestrial animal production) |

Biosecurity and good animal husbandry practices (aquatic animal production) |

Good management and hygiene practices in food processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

||||||||||

|

Austria |

||||||||||

|

Belgium |

||||||||||

|

Canada |

||||||||||

|

Chile |

||||||||||

|

Colombia |

||||||||||

|

Costa Rica |

||||||||||

|

Czech Republic |

||||||||||

|

Denmark |

||||||||||

|

Estonia |

||||||||||

|

Finland |

||||||||||

|

France |

||||||||||

|

Germany |

||||||||||

|

Greece |

||||||||||

|

Hungary |

||||||||||

|

Iceland |

||||||||||

|

Ireland |

||||||||||

|

Israel |

||||||||||

|

Italy |

||||||||||

|

Japan |

||||||||||

|

Korea |

||||||||||

|

Latvia |

||||||||||

|

Lithuania |

||||||||||

|

Luxembourg |

||||||||||

|

Mexico |

||||||||||

|

Netherlands |

||||||||||

|

New Zealand |

||||||||||

|

Norway |

||||||||||

|

Poland |

||||||||||

|

Portugal |

||||||||||

|

Slovak Republic |

||||||||||

|

Slovenia |

||||||||||

|

Spain |

||||||||||

|

Sweden |

||||||||||

|

Switzerland |

||||||||||

|

Türkiye |

||||||||||

|

United Kingdom |

||||||||||

|

United States |

||||||||||

|

Argentina |

||||||||||

|

Brazil |

||||||||||

|

Bulgaria |

||||||||||

|

China |

||||||||||

|

Croatia |

||||||||||

|

Cyprus |

||||||||||

|

India |

||||||||||

|

Indonesia |

||||||||||

|

Malta |

||||||||||

|

Peru |

||||||||||

|

Romania |

||||||||||

|

Saudi Arabia |

||||||||||

|

South Africa |

Note: The methodology used to build the dashboard is available in Annex 4.A. OECD and non-OECD countries are listed in alphabetical order.

No data

No data

No implementation

No implementation

First stage of implementation

First stage of implementation

Second stage of implementation

Second stage of implementation

Third stage of implementation

Third stage of implementation

Most advanced stage of implementation

Most advanced stage of implementation

Source: WHO/FAO/WOAH (2022[12]), Tripartite AMR Country Self‑Assessment Survey (TrACSS) 2021‑2022, https://amrcountryprogress.org/ (accessed on 4 December 2022).

Assessing the key design features of AMR-NAPs

Key messages

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries will benefit from keeping their AMR-NAPs up to date while streamlining efforts to measure performance over time.

Deepening engagement with international and regional organisations that facilitate co‑ordinated action in line with the One Health approach is needed.

Many AMR-NAPs can be further improved by incorporating budget considerations and cost‑effectiveness assessments.

The remainder of this chapter presents results from a systematic assessment of the content of AMR-NAPs from selected OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries based on a natural language processing (NLP) approach (Box 4.7). The OECD analysis first looks at the selected design features of AMR-NAPs, including performance tracking over time, engagement with international and regional bodies, and financial considerations and cost-effectiveness assessments. These features were selected because they were proposed as part of key design aspects of the AMR-NAPs that impact the effectiveness of the vision laid out in these documents (Chua et al., 2021[28]; Ogyu et al., 2020[29]; Anderson et al., 2019[30]). Next, the level of alignment between AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP is examined in terms of the strategic objectives and interventions recommended in the AMR-GAP.

Box 4.7. The OECD analysis deploys natural language processing techniques to examine the landscape of AMR-NAPs

Using text from AMR-NAPs as analysable data

The OECD analysis presented here is the first application of NLP guided methods to ascertain the level of alignment between AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP in 21 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries. Reflecting the advancement made in the application of machine learning techniques, NLP-guided techniques are increasingly being used to explore a variety of public health issues ranging from smoking behaviours (Pearson et al., 2018[31]), alcohol consumption (Rudge et al., 2021[32]) and obesity (Chou, Prestin and Kunath, 2014[33]) to public perception of policies to mitigate the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic (Petersen and Gerken, 2021[34]). The methodology used by the OECD analysis was vetted through a peer-review process in a high-impact Journal (Özçelik et al., 2022[35]) (a brief explanation of the methodology and the list of AMR-NAPs from the OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries included in the analysis are provided in the Annex 4.A).

The OECD analysis makes use of two commonly used NLP metrics to assess the level of alignment between AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP. Term frequency (TF) is the first metric used in the analysis. It is interpreted as the relative emphasis on each strategic objective/intervention in a collection of AMR‑NAPs. It is a preferable metric to assess relative emphasis because it enables an analysis that takes into account the differences between the lengths of documents. It quantifies the frequency by which each term is associated with strategic objectives and recommended interventions that occur within an AMR-NAP with respect to the total number of terms in the term dictionary developed by the OECD. The second NLP metric used in the OECD analysis is term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF). TF-IDF is calculated to enable a comparative analysis of AMR-relevant interventions that occur in a given AMR-NAP in comparison to how frequently these interventions are featured across the collection of action plans. By evaluating TF-IDF scores, interventions that are most distinctly highlighted in each AMR-NAP compared to other documents can be identified.

Source: Chou, W., A. Prestin and S. Kunath (2014[33]), “Obesity in social media: A mixed methods analysis”, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0256-1; Gentzkow, M., B. Kelly and M. Taddy (2019[36]), “Text as data”, https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20181020; Petersen, K. and J. Gerken (2021[34]), “#COVID‑19: An exploratory investigation of hashtag usage on Twitter”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.01.001; Pearson, J. et al. (2018[31]), “Exposure to positive peer sentiment about nicotine replacement therapy in an online smoking cessation community is associated with NRT use”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.022; Rudge, A. et al. (2021[32]), “How are the links between alcohol consumption and breast cancer portrayed in Australian newspapers?: A paired thematic and framing media analysis”, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147657.

Performance tracking toward the objectives stated in the AMR-NAPs can be enhanced across OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries are diverse in terms of the time period of implementation they cover in their AMR-NAPs. Typically, AMR-NAPs are forward-looking documents that set out strategic goals and objectives to be realised in a predetermined period of time. The OECD analysis shows that, on average, the AMR-NAPs from the countries included in the analysis cover a span of nearly five years. But exceptions arise. The AMR-NAP from the Slovak Republic has the narrowest time span covering the two‑year period 2019‑21, whereas the AMR-NAP from Australia sets a 20‑year vision for the years from 2020 to 2040. In addition, the OECD analysis shows that AMR-NAPs from 6 OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries predate the AMR-GAP and have not yet been updated since their initial publication, while many other AMR-NAPs are approaching the end of their coverage period.

There is a need to streamline the process to track performance relevant to the commitments made in the AMR-NAPs. Once they develop their AMR-NAPs, OECD members rely on different approaches to tracking their performance. For example, following the publication of its AMR-NAP in 2015, Germany regularly published interim reports that describe the national and subnational progress towards the goals stated in its AMR-NAP. France provides annual updates on the country’s progress towards the strategic priorities discussed in its AMR-NAP. Similarly, Australia publishes technical reports and analyses in regular intervals to continue to improve AMR awareness in hospital and community settings (ACSQHC, 2021[37]). While these efforts provide a valuable avenue to assess each country’s performance, there is little cross-country standardisation in the ways in which OECD countries examine their performance, making it difficult to compare cross-country performance over time.

Closer engagement with international organisations can help facilitate co‑ordinated action in line with the One Health approach

The OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries explicitly recognise that curtailing AMR requires building international alliances and partnerships, but the nature of engagement with international bodies is often left undiscussed. While all 21 AMR-NAPs referred to the WHO as a key partner in tackling AMR, only around 71% (15/21) directly referenced the AMR-GAP. In addition to the WHO, nearly all OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries made references to the WOAH, reflecting increasing attention to animal health as a pathway to tackle AMR. In comparison, the FAO was mentioned only by two‑thirds of AMR-NAPs (14/21) and UNEP was highlighted in less than 15% (4/21) of these documents. Importantly, even when these documents reference international bodies in their action plans, they do not often provide details on the extent of their engagement.

Globally, a number of regional AMR initiatives proliferated in recent years to tackle AMR (Box 4.8). In 2017, EU member states adopted the 2017 European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance, with the aim of bringing the EU to the forefront of efforts to tackle AMR (European Commission, 2017[38]). Another important regional initiative was initiated when AMR was included in the five‑year work programme of the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) from 2016 to 2020 (Yam et al., 2019[39]). ASEAN members reiterated their commitment to regional co‑operation in tackling AMR in the 2017 Joint Declaration on Action against AMR and 2018 ASEAN Plus Three Leaders’ Statement on Co‑operation against Antimicrobial Resistance. In 2018, the newly launched Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) network developed a framework for tackling AMR (Africa CDC, 2018[40]). In this framework, the members of Africa CDC committed to establishing the Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network, which will serve as a platform to foster collaboration across national public health institutions in the region.

Box 4.8. The European One Health Action Plan provides an important platform for cross-country collaboration and co‑operation to tackle AMR

Developed in 2017, the European One Health Action Plan supports the EU and its member states through a three‑pillar strategy of making the EU a best-practice region, boosting research, development and innovation, and shaping the global AMR agenda. Each pillar details actionable, interdependent steps to be pursued concurrently by the EC (European Commission, 2017[38]). The EU action plan stipulates that the member states are primarily responsible for identifying policies in alignment with their own needs and priorities, though the highlighted policies are considered to offer substantial value. Recently, the European Commission’s Directorate‑General for Health and Food Safety published a review of the policy priorities highlighted in the EU member states’ AMR-NAPs (European Commission, 2022[41]).

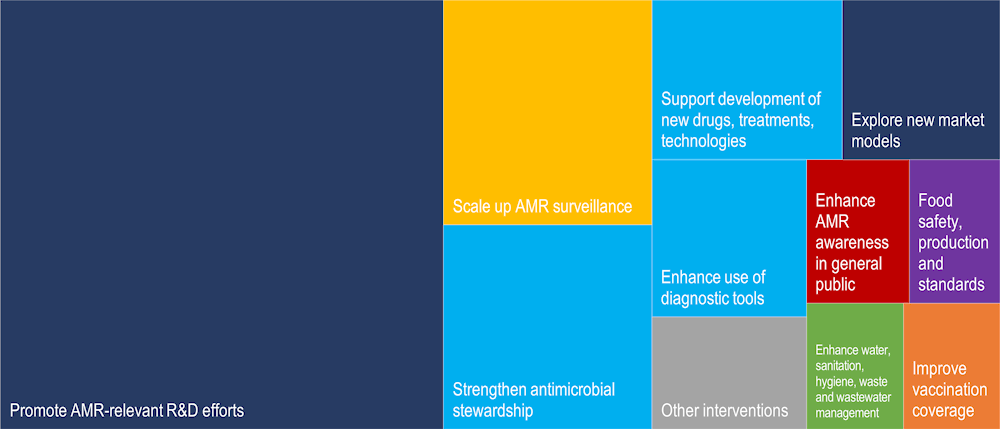

As shown in Figure 4.6, policies that receive the greatest attention in the EU action plan include supporting AMR-relevant R&D, exploring new economic models and incentives that promote AMR‑relevant innovations, scaling up AMR surveillance and stewardship interventions that promote the prudent use of antibiotics in the EU and beyond. In comparison, policies that promote improved water, sanitation, hygiene, waste and wastewater management practices are featured to a lesser extent, as well as policies to improve AMR awareness in the general public, enhancing food safety and improving food production and standards.

Figure 4.6. Top 10 interventions highlighted most frequently in the EU One Health Action Plan

Note: The colour dark blue denotes interventions that can help develop an economic case for sustainable investment; the light blue depicts interventions that aim to optimise antimicrobial use in human and animal health; the colour yellow denotes interventions to strengthen knowledge and evidence base through surveillance and research; the colour red represents interventions that can help improve awareness and understanding of AMR; orange denotes interventions to improve vaccination coverage and the colour grey denotes other interventions.

Source: OECD analysis focusing on the content of the EU One Action Plan in terms of the relative emphasis of policy interventions linked to strategic objectives highlighted in the WHO-GAP. Emphasis on each policy is measured as a function of the frequency of terms associated with that policy relative to the frequency of terms linked to all of the strategic objectives.

Source: European Commission (2017[38]), A European One Health Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-01/amr_2017_action-plan_0.pdf; European Commission (2022[41]), Overview Report: Member States’ One Health National Action Plans against Antimicrobial Resistance, https://health.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-11/amr_onehealth_naps_rep_en.pdf.

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries can further improve their action plans by integrating financial considerations and cost-effectiveness assessments in these documents

Most AMR-NAPs lack detailed discussions around financial resources allocated to supporting the AMR agenda. The AMR-GAP underscores that countries need to make financial commitments to ensure advancements towards the policy vision laid out in their action plans (WHO, 2015[1]). Further, the WHO, FAO and WOAH recommend that countries perform regular assessments and reviews of the existing financial commitments in order to ascertain whether funds are dispersed in a timely fashion and in accordance with the priorities discussed in the AMR-NAPs (WHO/FAO/WOAH, 2019[42]). Despite this, only 57% (12/21) of the AMR-NAPs from OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries discuss financial considerations and, even when financial considerations are mentioned, the level of financial resources committed to the AMR agenda often remains unclear.

Return on AMR-relevant investments can be better understood by utilising evidence generated by cost‑effectiveness assessments of interventions highlighted in AMR-NAPs. The OECD analysis shows that only around 43% (9/21) of OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries refer to the cost-effectiveness of AMR-relevant investments that they consider in their action plans. For instance, the AMR-NAP from Switzerland highlights that research efforts focusing on the development of new diagnostic products are considered to be a cost-effective measure to facilitate the rapid detection of AMR. The AMR-NAP from the United Kingdom also alludes to the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tools and suggests that evidence generated by cost-effectiveness models that demonstrate the value of diagnostic tools can be used to spur behaviour change among prescribers and health commissioners and encourage greater use of diagnostic tools. The AMR-NAP from Canada highlights that establishing a fast-track process to license antimicrobial drugs, alternatives to antimicrobials and new diagnostics is a cost-effective strategy to scale up investments in the development of pharmaceuticals. In the AMR-NAP from Malta, raising the awareness of employers on the benefits of extending options for home rest for employees who recover from mild infections is highlighted as a cost-effective strategy to interrupt the transmission of diseases in the workplace.

Assessing the alignment between AMR-NAPs and the AMR-GAP

Key messages

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries are consistent with the AMR-GAP in terms of the strategic objectives that they adopt in their action plans. There is a diversity of approaches across countries in terms of the range of interventions highlighted in AMR-NAPs to achieve these strategic objectives.

Optimising the use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health is the most prominently featured strategic priority but further improvements can be achieved:

Even though some older classes of antibiotics can still be used to treat certain indications, only about 24% of AMR-NAPs (5/21) reference older antimicrobials.

Less than half of AMR-NAPs (10/21) include discussions around AMR among the elderly populations, even though providers frequently prescribe antibiotics to their older patients as part of their treatment.

There are notable gaps in the monitoring of antibiotic consumption, with only around 19% of AMR-NAPs (4/21) referring to having at least one indicator based on a measure of defined daily doses or days of therapy.

In animal health, about one‑third of AMR-NAPs (6/21) lack any references to the antibiotics critically important to human health altogether.

While OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries well recognise the centrality of strengthening AMR surveillance, deficits exist in engagement with global and regional AMR surveillance networks, enhancing laboratory network capacity and collecting information from new data sources.

The existing infection prevention and control programmes can be further advanced by incorporating strategies that promote food security and safety, and enhance biosecurity:

In 2021‑22, 49 out of 51 OECD, EU/EEA and G20 countries had in place national and facility-level IPC programmes in line with the WHO IPC core components, but only 23 out of 51 of these countries reported having IPC programmes that operate at the national and facility levels, where compliance and effectiveness are monitored and evaluated regularly.

Only a handful of AMR-NAPs mention IPC measures like decolonisation (i.e. the eradication or the reduction in the asymptomatic carriage of bacteria) and environmental hygiene and only 12 out of 21 AMR-NAPs stress the importance of hand hygiene practices.

Only 3 out of 21 AMR-NAPs refer to biosecurity measures in farm settings.

The OECD countries remain the largest financers of AMR-related R&D but there is room for new commitments to push incentives and harness public-private partnerships.

With respect to strategies to improve AMR awareness and understanding, OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries put greater emphasis on interventions targeting medical professionals and the general community, whereas interventions targeting young children receive less attention.

The OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries are consistent with the AMR‑GAP in terms of strategic objectives that they adopt in their action plans (Figure 4.7). Much like the AMR-GAP, the most frequently emphasised strategic objective by OECD, EU/EEA and G20 countries relates to interventions aiming to optimise the use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health, followed by strengthening AMR surveillance, enhancing sanitation, hygiene and waste management practices and spurring investments in AMR technologies. In comparison, increasing AMR awareness and education is the least frequently discussed strategic priority by countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, as well as the AMR-GAP.

Figure 4.7. AMR-NAPs in most countries are well-aligned with the AMR-GAP in terms of the five strategic priorities

Note: The five strategic objectives displayed in the graph above are adapted from those discussed in the AMR-GAP. Emphasis on each strategic objective is quantified as a function of the total number of terms associated with that strategic objective relative to the total number of terms included in the term dictionary. Strategic objectives with greater term frequency are discussed more frequently in the text compared to those with lower term frequency. The whiskers represent the lowest and highest emphasis given to each strategic objective across the collection of AMR-NAPs.

Countries included in the analysis: Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Malta, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

AMR-GAP: Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; EU: European Union; EEA: European Economic Area; G20: Group of Twenty.

Source: Özçelik, E.A. et al. (2022[35]), “A comparative assessment of action plans on antimicrobial resistance from OECD and G20 countries using natural language processing”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.011.

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries are highly diverse in the interventions that they distinctly highlight in their action plans

Different AMR-relevant interventions receive varying levels of attention across AMR-NAPs from the OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries. For instance, with respect to interventions aiming to raise AMR awareness and understanding, Denmark and France stand out as countries that more frequently emphasise strategies to improve public awareness of AMR compared to others. Integrating AMR in professional education and training is more frequently highlighted in the action plans from Germany and the Slovak Republic. In terms of strengthening AMR knowledge and surveillance, Japan, New Zealand and the United States more frequently emphasise considerations around integrating new data sources into AMR surveillance, compared to the other countries included in the analysis. With respect to interventions to optimise antimicrobial use, Denmark, France and Norway more frequently discuss efforts to monitor antimicrobial consumption compared to other countries. Discussions around the importance of vaccines are more distinctly highlighted by Norway compared to other countries. In comparison, Finland, France and Japan more frequently discuss concerns related to enhancing biosecurity, and food safety and security. With respect to initiatives that aim to make an economic case for AMR investments, Switzerland and the United Kingdom more distinctly include discussions around exploring new market models and economic incentives, whereas Australia and France more distinctly highlight promoting public-private partnerships (PPP).

Several factors help explain the diverging patterns in interventions that countries emphasise in their AMR‑NAPs. A greater emphasis on one intervention does not imply that countries neglect other interventions. Instead, these diverging patterns may reflect the range of challenges that influence health system performance in each country at the time that policy makers develop these guiding documents. For example, India – one of the global AMR hotspots – is among the countries that explicitly highlight the importance of restricting the sale of antimicrobials without proper prescription. This pronounced emphasis may be partly due to the high prevalence of informal healthcare providers with no formal medical training in prescribing antimicrobials without prescription (Das et al., 2016[43]).

Alternatively, countries may choose to highlight strategies that they aspire to implement in the future rather than discussing strategies that they already put in place. For instance, Denmark does not provide in-depth discussions on the use of antimicrobials as growth promoters in its action plan even though this practice has been outlawed in the country in 1995. Similarly, in the United States, the AMR action plan does not specifically refer to electronic prescribing (e‑prescribing) because this practice is considered to be well-integrated into the health system. Another alternative explanation relates to the socio‑economic, historical and political factors, as well as the broader health system governance arrangements that may influence which interventions are ultimately featured in the AMR-NAPs. For instance, in Denmark and Sweden, veterinarians, farmers and regulatory authorities have a long history of co‑operation and collaboration, which has been shown to affect the ways in which the AMR agenda has developed in these countries (Björkman et al., 2021[44]; FAO, 2020[45]).

OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries highlight a wide range of interventions in their AMR-NAPs to optimise the use of antimicrobial medicines in human and animal health

Most policies that aim to optimise the use of antibiotics recognise that the choices made by individuals are an important part of antibiotic use. Health professionals’ prescription behaviours are influenced by a range of factors including their medical training, the availability of systems that support clinical decision-making, provider compensation methods, professional and social preferences, and norms. Similarly, patient knowledge, preferences and attitudes play an important role in antibiotic use. Patient behaviours such as self-medication and non-compliance with the recommended course of treatment undermine efforts to curb AMR. Interactions between healthcare providers and patients have also been shown to influence behaviours around antibiotics.

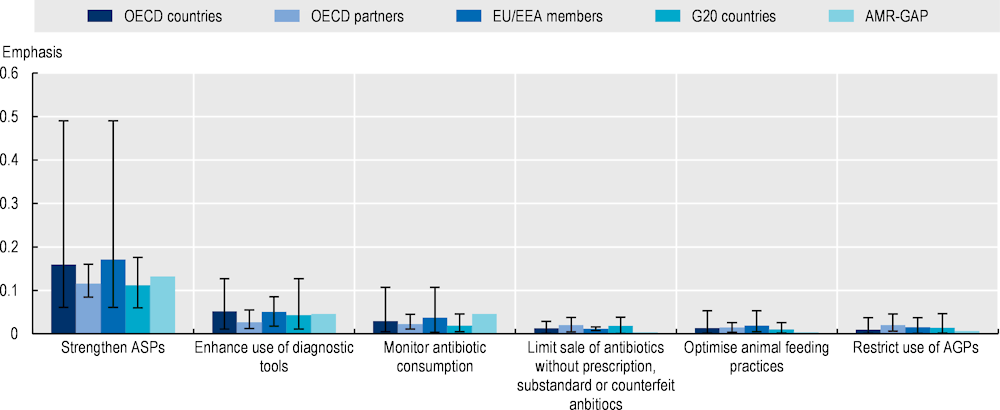

All 21 AMR-NAPs explicitly recognise the importance of optimising the use of antibiotics, though these documents lay out a wide array of approaches to achieve this goal (Figure 4.8). Much like the AMR-GAP, AMR-NAPs from OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries most frequently highlight efforts to strengthen antimicrobial stewardship programmes (ASPs) to promote the prudent use of antimicrobials. ASPs typically refer to a set of complex programmes that involve the implementation of multiple interventions designed to improve the ways in which antibiotics are prescribed by health professionals and used by patients. In addition to ASPs, enhancing the use of diagnostic tools is another frequently mentioned strategy in action plans, as well as monitoring the consumption of antimicrobials. In comparison to other interventions to optimise antibiotic use, OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries less frequently mention efforts to limit the sale of antibiotics without a prescription and counterfeit or substandard antimicrobial sales, optimise animal feeding practices and restrict the use of antibiotics as growth promoters.

Figure 4.8. Antimicrobial stewardship programmes in human and animal health are the most highlighted interventions in AMR-NAPs

Note: The graph above displays a set of interventions selected from those recommended by the WHO to optimise antimicrobial use in human and animal health. Emphasis on each AMR-relevant intervention is quantified as a function of the total number of terms associated with that intervention relative to the total number of terms included in the term dictionary. Interventions with greater term frequency are discussed more frequently compared to interventions with lower term frequency. The whiskers represent the lowest and highest emphasis given to each intervention across the collection of AMR-NAPs.

Countries included in the analysis: Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Japan, Malta, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

AGPs = antimicrobials as growth promoters; AMR-GAP: Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance; ASPs = antimicrobial stewardship programmes; EU: European Union; EEA: European Economic Area; G20: Group of Twenty.

Source: Özçelik, E.A. et al. (2022[35]), “A comparative assessment of action plans on antimicrobial resistance from OECD and G20 countries using natural language processing”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.011.

Support antimicrobial stewardship programmes in human health

OECD countries rely on ASPs with varying design features to optimise antibiotic use to reflect the needs and priorities in their own settings. For example, in its AMR-NAP, Denmark considers a range of national and local measures to reduce the overall consumption of antibiotics in primary healthcare, with a recognition that different regions may require different measures to achieve the desired reductions in antibiotic consumption. The Danish approach has an explicit focus on the treatment of specific target groups like respiratory infections in children, coughs in adults or urinary tract infections in women. In addition, the Danish AMR-NAP encourages delayed prescribing practices, co‑operation with regional consultants and promotion of tools that can provide electronic overviews and comparisons of prescribing practices. In comparison, in its AMR-NAP, Sweden aims to promote the responsible use of antibiotics rather than an overall reduction in antibiotic consumption. To achieve this goal, Sweden relies on a multi‑modal approach that includes a continued focus on antibiotics prescriptions by authorised professionals, continued measurement of data on compliance with treatment guidelines both in human healthcare and veterinary medicine, adequate access to new and older antibiotics, and an emphasis on quality assured and adequate diagnostics, as well as the management of common infections. Importantly, Sweden combines interventions focusing on prescribing behaviours in the human health sector with efforts to promote responsible antibiotic manufacturing, safe disposal of antibiotics and waste management to promote responsible use in the lifetime of the antibiotics, as well as efforts to optimise antibiotic prescribing in veterinary medicine.

Recent WHO guidance points out that course corrections may be needed in the implementation of activities carried out under the overall organisation of ASPs over time. These modifications may be introduced either by altering the ways in which the interventions are implemented on the ground or by introducing new interventions to reflect the evolving needs in a given context of care (WHO, 2019[46]). The WHO guidance notes that the ease of implementation of each type of ASP will largely correlate with the availability of resources and competencies in health facilities and recommends the prioritisation of interventions in accordance with resource availability in a given context.

The effectiveness of many ASPs can be enhanced by extending antibiotic guidance to healthcare settings beyond hospital and acute care. The OECD analysis shows that hospitals and acute care facilities constitute around 75% of different types of healthcare settings discussed in AMR-NAPs from OECD countries and key partners, EU/EEA and G20 countries, followed by primary healthcare, and community settings (14%) and long‑term care (11%). Moreover, none of the AMR-NAPs makes any references to developing guidance for telemedicine, even though this mode of healthcare delivery had already been on the rise even before the COVID‑19 pandemic (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[47]).

Only a handful of OECD countries adopt a comprehensive approach to tackling AMR in older populations. For example, Japan is considering options to incorporate materials concerning AMR, IPC and antimicrobial stewardship into the undergraduate curriculum and training guidelines for professionals deployed in nursing care. In addition, the national qualification examinations for nursing care staff will expand their focus on these topics. Japan also aims to strengthen AMR surveillance in nursing care, while conducting research to establish the current status of AMR in nursing care facilities. Complementing these efforts, Japan aims to establish clinical reference centres for AMR at the local level. These centres will be responsible for developing AMR-relevant educational materials to be used in a variety of settings, including nursing homes. These interventions will be supported by revising the IPC guidelines and manuals, which will introduce AMR and AMR screening components.

The Access, Watch and Reserve (AWaRe) framework offers another important avenue for OECD countries to support their local, national and global efforts to strengthen ASPs. The WHO developed the AWaRe framework in 2017 as part of the Essential Medicines List (EML) (WHO, 2021[48]). The AWaRe classifications provide a valuable framework for monitoring the use of antibiotics, setting targets and evaluating the effectiveness of ASPs (WHO, 2021[48]). It also provides a list of drugs that are is considered essential for the provision of basic healthcare services. In 2021, the AWaRe framework classified a total of 258 antibiotics across three groups:

Access: Broadly, Access antibiotics are comprised of lower-spectrum drugs used primarily as first- or second-line therapies. The WHO recommends that Access antibiotics constitute at least 60% of total consumption at the national level by 2023.

Watch: The Watch antibiotics contain broad-spectrum antibiotics and they pose a greater risk for AMR. The WHO recommends that Watch antibiotics are used only for treating specific indications.

Reserve: The Reserve antibiotics should be considered as a last resort, with their use being monitored closely and targeting multidrug resistant infections.