The capacity of the EU agro-food sector to combine productivity, sustainability and resilience is driven by recent and ongoing structural changes, the management of natural resources, and the evolution of the EU innovation system. This chapter examines trends in agro-food production, consumption and trade, and discusses the EU economy-wide policies that impact the sector’s performance. The European Union is the world’s largest agro-food exporter and one of its largest importers. Agriculture occupies 39% of the land, but contributes only 1.7% to the European Union’s gross domestic product (GDP). Recent food system initiatives, digitalisation and data-related strategies can contribute to relevant social, economic, and environmental objectives, improving agricultural practices, empowering farmers, and addressing challenges such as the generational renewal and improving the role of women in agriculture.

Policies for the Future of Farming and Food in the European Union

2. Context and drivers

Abstract

Key messages

The European Union’s agro-food sector ensures the food security of its population while also contributing to global food security.

Agriculture production only contributes to 1.7% of the European Union’s gross domestic product (GDP) but generates significant economic gains. The European Union is the world’s largest agro-food exporter and one of its largest importers.

While agriculture occupies 39% of the land, total agricultural land has declined over the last 20 years. This decline, driven mainly by urbanisation and afforestation, has especially impacted arable land and pastureland.

European meat production and consumption have shifted from beef and veal towards poultry since the early 1990s.

There has been an increasing concentration of agricultural production on fewer but larger farms during the last two decades.

EU agricultural income continues to stay below the average income of the economy, although the gap between farm income and income in other economic sectors has been declining.

The share of the EU working population employed in agriculture fell while the average agricultural income per full-time employee increased. The outflow of local labour has been partially compensated by inflows of foreign labour, including undocumented workers, whose number is difficult to quantify.

Women are underrepresented in the EU farming sector as in many other OECD countries. Gender bias is currently a structural characteristic of agriculture in almost all Member countries.

The European Structural and Investment Funds, the main investment policy tool to support job creation and sustainable economic growth, has had mixed results regarding regional convergence since 2000: regional disparities in GDP per capita declined significantly until the global financial crisis, but much more slowly afterwards. Moreover, regional inequalities within countries have not converged, and have, in some cases, increased.

Digitalisation and data strategies are high on the EU agenda to contribute to achieving the objectives of the European Green Deal and the Common Agricultural Policy.

This chapter sets the review of EU agriculture and food-related policies in the broader economic and policy context. It presents an overview of the main features of the EU agriculture and food sector (Section 2.1), the essential drivers of the agro-food sector’s performance as defined in the OECD Agro‑Food Productivity-Sustainability-Resilience (PSR) Policy Framework (Section 2.2) and EU economy-wide policies that have an impact on the sector performance (Section 2.3). Several aspects of this overview are analysed in more depth in the three following chapters of the review: agricultural policy setting (Chapter 3), environmental sustainability (Chapter 4), and innovation for sustainability (Chapter 5).

2.1. Agriculture and food sector in context

2.1.1. The European Union is one of the world’s largest agro-food players

An important contextual development of the European Union has been its successive enlargements from the six original Member States to a total of 28 in 2020 prior to the exit of the United Kingdom. These enlargements mean that EU Member States are now a much more heterogeneous group of countries than at the outset, both in terms of their overall levels of economic development, their agricultural orientations determined in part by the different agro-ecological and climate zones, and differences in agricultural structures and the use of technologies.

The EU agro-food sector ensures the food security of its population while also contributing to global food security. Agriculture only contributes to 1.7% of the EU GDP and 4.3% of employment, but agro-food exports and imports show larger shares (Table 2.1). Although the contribution of agriculture to both EU GDP and employment has been relatively stable since 2000, the share of agriculture in the European Union’s exports has considerably increased during this period, also as a result of EU enlargement.

Crops – including cereals, oilseeds, fresh fruit and vegetables, and plants and flowers – predominate in agricultural output, accounting for 57% of total production, although this share differs significantly across Member States. Livestock products – including dairy, beef and veal, pig meat, sheep meat, and poultry and eggs – account for the remainder.

Table 2.1. European Union: Contextual indicators

|

2000 (EU15) |

2020 (EU27) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Economic context |

||

|

GDP (USD billion in PPPs) |

9 932 |

18 631 |

|

Population (million) |

378 |

447 |

|

Population density (inhabitants/km2) |

114 |

107 |

|

GDP per capita (USD in PPPs) |

26 300 |

41 584 |

|

Trade as a % of GDP |

11 |

12 |

|

Agriculture in the economy |

|

|

|

Agriculture in GDP (%) |

1.8 |

1.7 |

|

Agriculture share in employment (%) |

4.3 |

4.3 |

|

Agro-food exports (% of total exports) |

6.0 |

9.3 |

|

Agro-food imports (% of total imports) |

5.8 |

6.8 |

|

Characteristics of the agricultural sector |

|

|

|

Crop in total agricultural production (%) |

54 |

57 |

|

Livestock in total agricultural production (%) |

46 |

43 |

Note: EU: European Union; GDP: gross domestic product; USD: United States dollar; PPP: purchasing power parity.

Sources: OECD, UN Comtrade, and Eurostat and World Bank (WDI) databases, as reported in OECD (2022[1]).

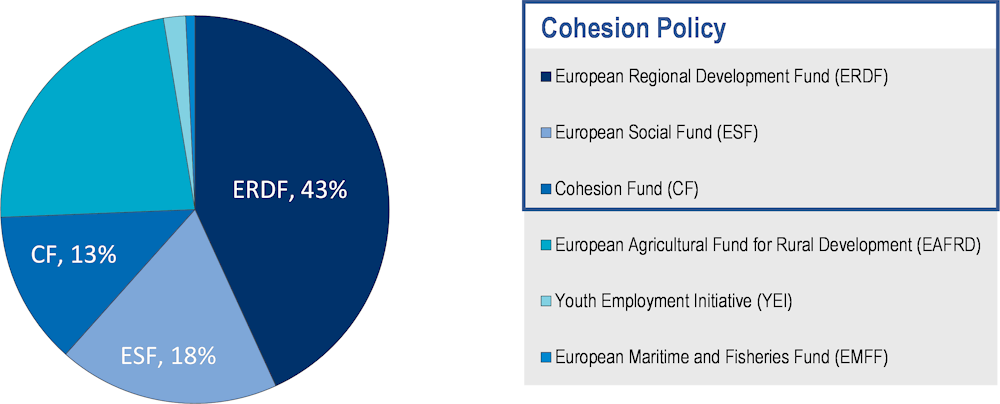

Agricultural trade is essential to ensure food security, diversification of diets and better rural incomes in many EU regions. The European Union is a net food exporter, with agro-food products accounting for 9.3% of all exports and 6.8% of all imports. The European Union has been the world’s largest agro-food exporter since 2013 and remains one of its largest importers as well. The region’s agro-food exports are overwhelmingly composed of processed goods for final consumption (61%), while imports are more evenly distributed among other categories, with processed goods for final consumption accounting for the largest share of imports (28%) (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Evolution and composition of EU agro-food trade, 2000 to 2021

Notes: Numbers may not add up to 100 due to rounding. Extra-EU trade: EU15 for 2000-03; EU25 for 2004-06; EU27 for 2007-13, EU28 for 2014-19 and EU27 (excluding the United Kingdom) from 2020.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on UN (2022[2]).

More specifically, the European Union is a net exporter in many categories of agriculture and food products (Table 2.2). In 2021, the main food groups characterising EU exports were beverages, spirits and vinegar; meat and edible meat; preparations of cereals, flour, starch or milk and pastrycooks’ products; dairy produce, birds’ eggs, natural honey and edible products of animal origin; and miscellaneous edible preparations. These categories represented about half of the total value of exports to non-EU countries (USD 106.1 billion). Net imported products, which included edible fruit and nuts; animal or vegetable fats; oil seeds and oleaginous fruits and miscellaneous grains, seeds and fruit; and coffee, tea, mate and spices, accounted for around 48% of the European Union’s total agro-food import, corresponding to USD 71.1 billion.

Table 2.2. Agro-food trade in the European Union, 2021

|

HS code |

Product description |

Exports (USD million) |

Share in agro-food exports |

Imports (USD million) |

Share in agro-food imports |

Trade balance |

Total trade (X+M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

22 |

Beverages, spirits and vinegar |

39 453 |

18.7% |

8 985 |

6.0% |

30 467 |

48 438 |

|

08 |

Edible fruit and nuts; peel of citrus fruit or melons |

6 530 |

3.1% |

24 732 |

16.6% |

‑18 202 |

31 261 |

|

15 |

Animal or vegetable fats and oils |

9 365 |

4% |

18 662 |

13% |

‑9 297 |

28 028 |

|

02 |

Meat and edible meat offal |

19 207 |

9.1% |

4 034 |

2.7% |

15 173 |

23 241 |

|

12 |

Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits; miscellaneous grains, seeds and fruit |

5 138 |

2.4% |

16 346 |

11.0% |

‑11 208 |

21 484 |

|

23 |

Residues and waste from the food industries; prepared animal fodder |

8 804 |

4.2% |

12 416 |

8.3% |

‑3 612 |

21 220 |

|

19 |

Preparations of cereals, flour, starch or milk; pastrycooks’ products |

17 023 |

8.1% |

3 091 |

2.1% |

13 931 |

20 114 |

|

21 |

Miscellaneous edible preparations |

14 339 |

6.8% |

5 710 |

3.8% |

8 629 |

20 048 |

|

04 |

Dairy produce; birds’ eggs; natural honey; edible products of animal origin |

16 585 |

7.9% |

2 053 |

1.4% |

14 531 |

18 638 |

|

10 |

Cereals |

11 525 |

5.5% |

6 427 |

4.3% |

5 097 |

17 952 |

|

20 |

Preparations of vegetables |

10 222 |

4.8% |

6 509 |

4.4% |

3 714 |

16 731 |

|

18 |

Cocoa and cocoa preparations |

8 903 |

4.2% |

7 553 |

5.1% |

1 350 |

16 456 |

|

09 |

Coffee, tea, mate and spices |

3 283 |

1.6% |

11 374 |

7.6% |

‑8 091 |

14 657 |

|

07 |

Edible vegetables and certain roots and tubers |

6 607 |

3.1% |

5 680 |

3.8% |

927 |

12 287 |

|

24 |

Tobacco and manufactured tobacco substitutes |

6 135 |

2.9% |

2 697 |

1.8% |

3 438 |

8 832 |

|

06 |

Live trees and other plants; bulbs, roots and the like; cut flowers and ornamental foliage |

5 344 |

2.5% |

2 104 |

1.4% |

3 240 |

7 448 |

|

17 |

Sugars and sugar confectionery |

3 838 |

1.8% |

2 063 |

1.4% |

1 775 |

5 900 |

|

Others |

18 540 |

8.8% |

8 414 |

5.7% |

10 126 |

26 954 |

|

|

Total agri-food trade |

210 838 |

148 850 |

61 988 |

359 689 |

|||

Notes: Agro-food trade (including fish and fish products) codes in H0: 01-24, 3301, 3501-3505, 4101-4103, 4301, 5001-5003, 5101-5103, 5201-5203, 5301, 5302, 290543/44, 380910, 382360. It does not include intra-European Union trade.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on UN (2022[2]).

2.1.2. The composition of the diet is stable, but the patterns of meat consumption are changing

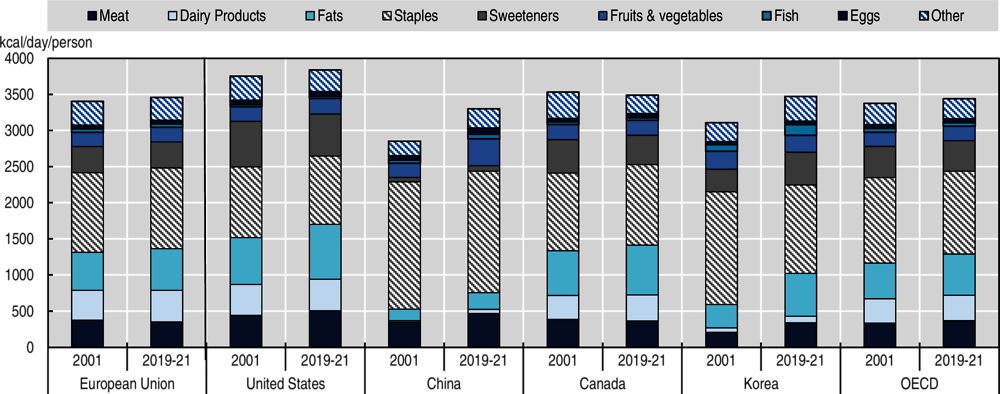

The composition of the European diet has remained stable over the last two decades. The daily caloric availability has only increased by 2% (+52 kcal/person/day) to reach an average of 3 447 kcal/person/day in 2021. Overall, staples constitute the base of the European diet and provided 32% of the daily energy intake in 2019-21, followed by fats (16.6%), dairy products (12.5%), sweeteners (10.5%), meats (10.1%), fruits and vegetables (5.8%), and eggs and fish (both accounting for 1.4% of total calorie availability) (Figure 2.2).

In the European Union, per capita meat consumption has decreased and has been shifting from red meat towards poultry, which is consistent with the trend in OECD countries (OECD/FAO, 2022[3]). This can mainly be explained by lifestyle changes towards lower meat protein consumption due to growing awareness of health, environmental and animal welfare issues and more sedentary lifestyles that limit additional protein intake (de Boer and Aiking, 2022[4]). Per capita red meat consumption has decreased by 14% in the last two decades, while per capita poultry consumption has increased by 30% over the same period. In comparison, per capita meat calorie availability has increased by 15% and 34% in the United States and China, respectively, during the last two decades (OECD/FAO, 2022[5]). In OECD countries, on average, trends reveal an increase of per capita availability of 8.7% from 2000 to 2019-20, with demand for red meat weakening and shifting to more white meat.

Per capita availability of dairy products, on the other hand, has increased since the 2000s in the European Union and other high-income countries. The daily calorie availability grew by 2.23% annually, reaching 439 kcal/person/day in 2019-21. This growth is mostly driven by an upward trend in the consumption of processed dairy products such as cheese and fresh dairy products. Per capita availability of cheese has increased annually by 1.30%, reaching 146 available kcal/cap/day in 2019‑21, while consumption of other dairy products, such as butter and skim milk powder, have remained stable. In recent years, the composition of demand has been shifting towards dairy fat such as full-fat drinking milk and cream in the European Union and the United States. Recent studies shed a more positive light on the health benefits of dairy fat consumption, contrary to the messaging of the 1990s and 2000s. This new evidence may have influenced consumers to modify their diets (OECD/FAO, 2022[5]).

During the last decade, EU countries introduced policies to encourage and promote a shift towards healthier diets. Front-of-pack labelling, dietary guidelines and sugar-sweetened beverage taxes have been used in several Member States, where diabetes and obesity trends have been worsening over time (WHO, 2019[6]). Other complementary measures, such as reformulation by the industry and reduction of children-targeted marketing, aim to reduce sugar, fat and salt consumption.

Figure 2.2. Per capita calorie availability of the main food groups in selected economies

Notes: EU27. Estimates are based on historical time series from the FAOSTAT Food Balance Sheets database. Estimates of food availability, not equivalent to actual consumption. Quantities of food available for human consumption are higher than quantities consumed, as some of the food that is potentially available to consumers is lost or wasted along the supply chain. This share is particularly high for perishable products such as dairy products and fruits and vegetables. The FAO estimates that globally, about 14% of food produced is lost before reaching the retail level. An important share of food available to consumers is also wasted; this was estimated at 17% in 2019. Staples include cereals, roots, tubers and pulses. Fats include butter and vegetable oil. Sweeteners include sugar and high-fructose corn syrup. The category “Other” refers to other crops and animal products.

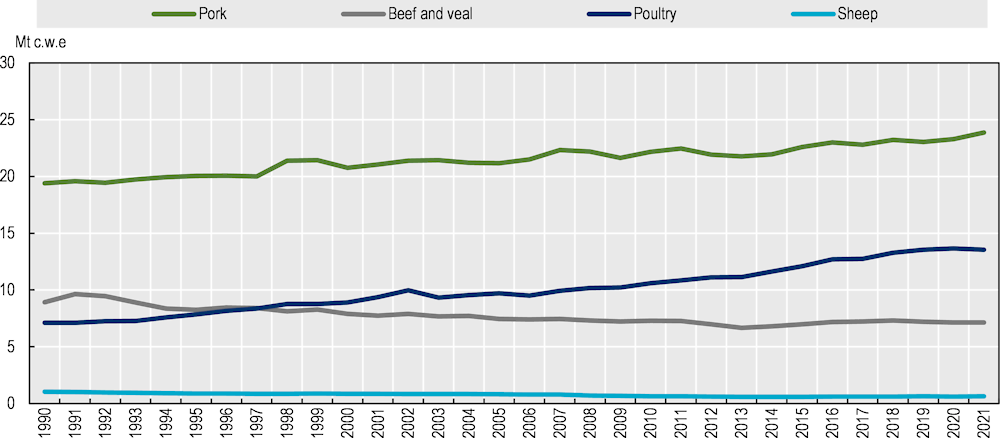

2.1.3. The patterns of meat production have also changed

Along with the shift in European meat consumption over the last decades, the patterns of meat production have also changed (Figure 2.3). From the beginning of the 1990s, beef and veal production dropped by 27%, yet has remained relatively stable since 2010. Poultry production, on the other hand, experienced a significant increase of 90% in the same period. Accordingly, while beef and veal production was higher compared to poultry in 1991, this had reversed in 2021, with amounts of 6.9 million tonnes compared to 23.9 million tonnes of carcass weight. At the same time, the production of pork also increased by 22%, reaching a high peak of 23.9 million tonnes of carcass weight. Conversely, sheep production experienced the sharpest decline, 43%, with the lowest production quantities (0.6 million tonnes of carcass weight) in 2021. These structural changes in the EU livestock sector from ruminants to monogastric (e.g. from beef or poultry production) have led to reduced methane emissions and higher efficiency gains. While there is little awareness of the link between diets and climate change, a shift in European diets towards reduced meat consumption is crucial to achieving climate change targets (Wellesley, Happer and Froggatt, 2015[8]).

Figure 2.3. Production of meat in the European Union, 1990 to 2021

2.2. Drivers of the agriculture and food sector’s performance

2.2.1. Natural resources and climate change

Urban expansion, afforestation and farming withdrawal led to a consistent reduction of agricultural land

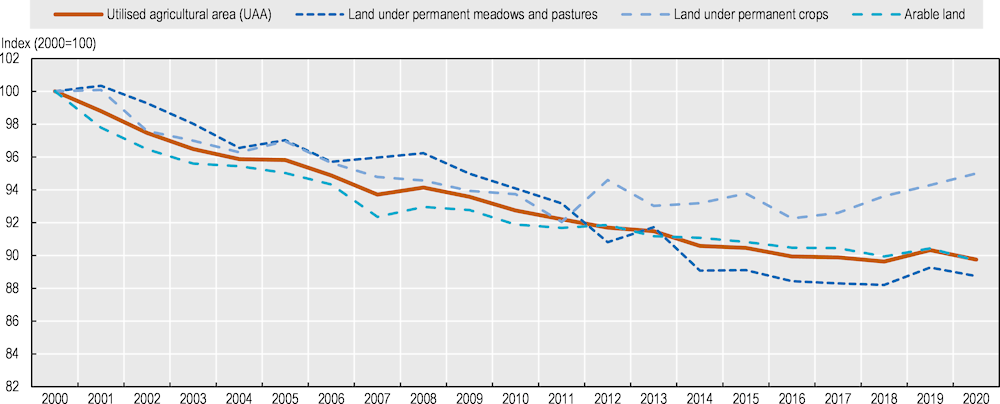

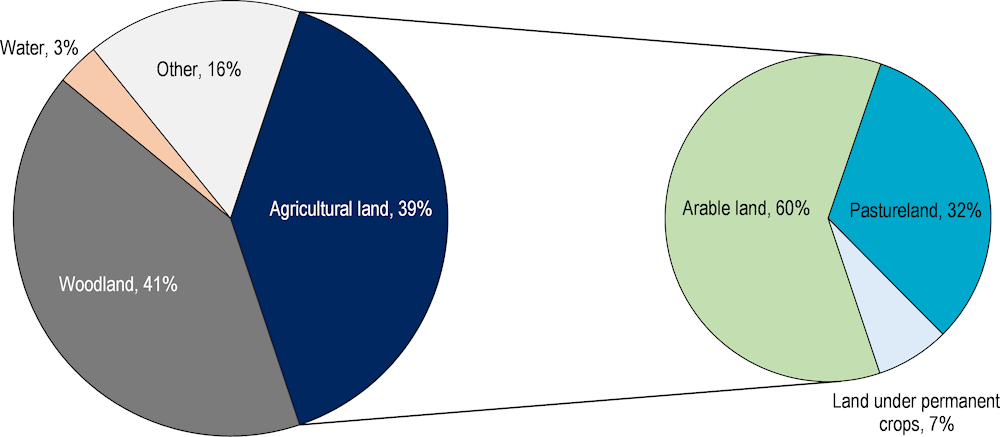

In 2018, the largest proportion of the total area of the European Union was covered by woodland (41%), followed by agriculture, which occupies 39% of the European Union’s landmass. The majority of utilised agricultural area (UAA) is arable land (60.3% in 2018), which is mainly used to produce crops for human and animal consumption. Permanent grassland accounts for a further third (32.5%) of the UAA and is mainly used to provide further fodder and forage for animals. The remaining area (7.2%) is used for permanent crops such as fruit, olives and grape production (Figure 2.4).

FAO data show that, during the last 20 years in Europe, there has been a consistent reduction – of about 10% – of agricultural land that has affected all types of land use. As shown in Figure 2.5, pastureland declined rapidly between 2008 and 2014 but has been mostly stable since. After a similar declining trend, land under permanent crops has increased since 2016. In 2020, it had returned to the 2007 level.

Agricultural land losses are mainly due to urban expansion – including transport infrastructure, afforestation and farming withdrawal. In the period 2000‑18, 14 049 km² of agricultural land was urbanised, mostly at the expense of arable lands and permanent crops (around 50% of the total urbanisation), and of pastures and mosaic farmlands (almost 30%) (EEA, 2019[9]). Overall, the urbanisation process, combined with the homogenisation of agricultural fields and intensive land use, have negative effects on biodiversity. This is particularly evident for farmland and birds using this type of habitat (EEA, 2021[10]). As discussed in Chapter 1, the latest data on European common birds shows a continued decline of European farmland birds (PECBMS, 2022[11]).

Figure 2.4. Land use in the European Union, 2018

Note: EU27. Numbers may not add up to 100 due to rounding.

Source: Eurostat (2022[12]), accessed August 2022.

Figure 2.5. Developments in land use in the European Union, 2000 to 2020

There are signs of improvements in some agri-environmental indicators of inputs in the EU27 agriculture, but the sustainable use of water is still a major challenge

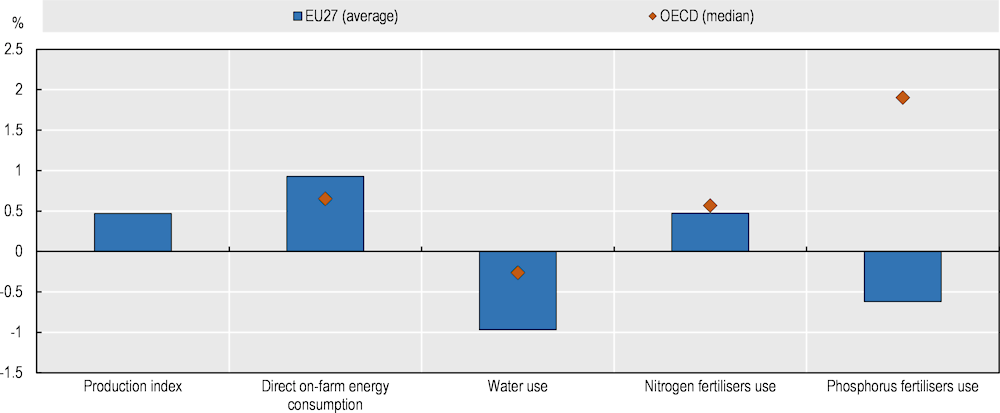

Increases in EU agricultural production observed over the last decade are combined with increases in the use of some inputs, such as direct on-farm energy consumption and nitrogen fertilisers. However, a reduction in water use was observed (-0.3% per annum) and, unlike the OECD average, a consistent reduction was also observed in the use of phosphorus fertilisers (-0.6% per annum) (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Production and input use in the European Union and the OECD

Notes: All indicators are divided by agricultural land area. Data for nitrogen fertilisers and phosphorus fertilisers refer to the periods 2007‑09 and 2012-14.

Source: OECD (2022[14]).

In 2019, energy consumption by agriculture made up 3.3% of final energy consumption in the European Union. Just over half (55%) of agriculture’s total energy consumption was from oil and petroleum products (excluding biofuels), the main fuel type in most countries. The other key types of fuel were electricity (17%), natural gas (14%), and renewables and biofuels (9%) (Eurostat, 2022[15]).

While irrigation contributes significantly to agriculture’s productivity, it exerts major pressure on freshwater resources in some regions, both by abstraction of the resource and by agricultural run-off (Gruère and Shigemitsu, 2021[16]). Trends in irrigated areas and water abstraction vary widely across Europe. Around 7-8% of the UAA in the EU27 was irrigated annually on average in the last ten years (Eurostat, 2020[17]). High shares of irrigated areas are found in southern European countries, especially Greece, Spain, Italy, and Malta, but also in France, Cyprus, Portugal, and the Netherlands (EEA, 2021[18]). Water is abstracted for use across economic sectors in the EU27. Abstraction for cooling in electricity generation remained the largest contributor to total annual water abstraction (32%) in 2019, followed by reported abstraction for agriculture (28%), public water supply (20%) and manufacturing (13%) (EEA, 2022[19]). There are considerable differences in the amounts of freshwater abstracted in each EU Member State, in part reflecting the size of each country and the resources available, but also abstraction practices, climate, and the industrial and agricultural structure of each country. However, specific regions may face problems associated with water scarcity; this is particularly the case in parts of southern Europe, where it is likely that agricultural water consumption (as well as other uses) will need to decline to prevent seasonal water shortages (Eurostat, 2022[20]). In any case, national water policies need to be adjusted to local contexts, especially in the context of a geographically and climatically diverse European Union (OECD, 2021[21]).

European agriculture is dependent on imports of fertilisers. EU farmers used 11.2 million tonnes of mineral fertilisers (nitrogen [N] and phosphorus [P]) in 2020 (Eurostat, 2022[22]), a third of which is imported. Over time, nitrogen-based fertilisers have been the most traded products with third countries. More than 3 million tonnes have been imported annually into the European Union since 2015 (EC, 2019[23]). The nitrogen-based fertiliser industry is heavily dependent on gas of Russian origin, and the Russian Federation (hereafter “Russia”) and Belarus are key players in the world production of rock-based fertilisers (phosphates and particularly potassium). The military aggression in Ukraine and the application of sanctions on Russia have led to higher fertiliser prices, which will likely impact the use of fertilisers in agriculture in the European Union and also on yields and quality (Chapter 3, Box 3.2) (Eurostat, 2022[24]) (Eurostat, 2022[24]). In November 2022, the European Commission released a communication outlining several best practices and ways forward to help farmers optimise their fertiliser use and reduce their dependencies while securing yield (EC, 2022[25]).

The effects of climate change on EU27 agriculture are expected to increase, but the impacts will depend on regional characteristics

Climate change represents one of the main environmental problems of the 21st century, which is already having several consequences on natural resources due to the increased climate variability and the increasing frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration and timing of extreme climate events (IPCC, 2022[26]). Agriculture is one of the economic sectors facing the greatest impact, and even in Europe, climate change has already influenced crop yields and livestock productivity and will continue to increase pressure on production (OECD, 2014[27]; EEA, 2019[28]). Ortiz-Bobea et al. (2021[29]) estimated that climate change has reduced global agricultural total factor productivity (TFP) by about 21% since 1961. This slowdown is equivalent to losing the last seven years of productivity growth, even though relevant regional and cross-country disparities were observed: more severe impacts (from -26% to -34%) are observed in warmer regions such as Africa and Latin America compared to cooler regions such as North America (-12.5%) and Europe and Central Asia (-7.1%). Ray et al. (2019[30]) estimated that yields for all the dominant crops in western and southern Europe have already decreased between 6.3% and 21.2% due to climate change.

Weather and climate conditions also affect the availability of water needed for irrigation, livestock watering practices, the processing of agricultural products, and transport and storage conditions. As reported by the European Environment Agency, climate change impacts on agriculture are projected to produce up to 1% average GDP loss by 2050, but with large regional differences (EEA, 2019[28]). Recent projections (EC, 2020[31]) show that climate change could further restrict the water available for irrigation and result in yields that are lower than the potential achievable under full irrigation. Under an extreme assumption of no irrigation in the future, severe declines (over 20%) in maize yield have been projected for all countries, with crop losses of up to 80% for some countries in southern Europe (Bulgaria, Greece, Portugal, and Spain). This implies that without market adjustments, maize production may no longer be viable in areas with high risk for water scarcity and significant decreases in precipitation. In contrast to grain maize, wheat is mostly a non-irrigated, rain-fed crop in Europe. Increases in yields by around 5% on average are projected for northern Europe due to changes in precipitation regime combined with an anticipated growing cycle and enhanced growth from increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Yield reductions are projected for southern Europe by 12%, on average, corroborating empirical evidence of a limited CO2 effect on wheat under limited water conditions. Limiting global warming to 1.5°C could reduce these losses by 5%.

While the increasingly extreme weather and climate events are expected to increase crop losses and reduce livestock productivity across all regions, climate change is projected to reduce crop productivity especially in southern Europe. In northern Europe, on the contrary, the lengthening of growing seasons and the higher temperatures will improve the suitability for growing crops. Finally, in various regions in Europe, increasing drought risk is expected to reduce livestock productivity through negative impacts on grassland productivity and animal health.

2.2.2. Structural change and socio-economic issues

The EU farming sector has undergone significant structural changes over the last decades. The following subsection provides an overview of the most apparent and policy-relevant transformations in the sector: a reduction in the number of farms along with an increase in farm size and the declining share of young farmers in the agricultural working population.

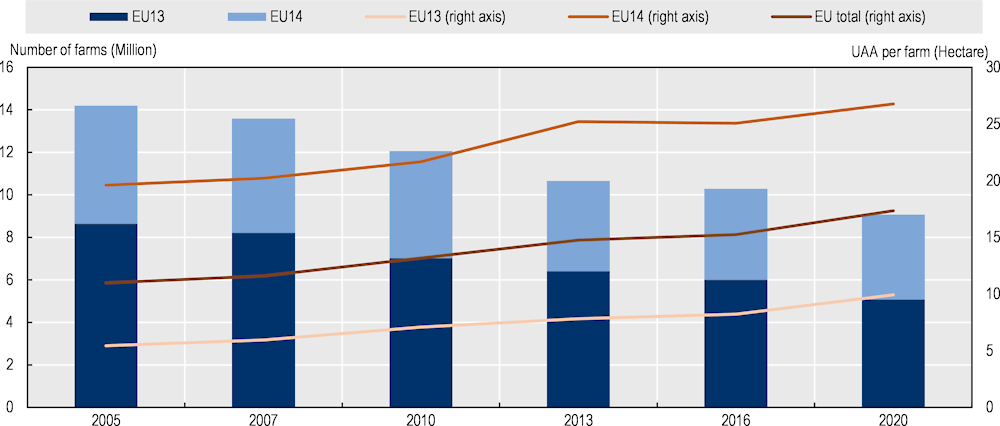

Declining number of farms and increasing average farm size

A decline in farm population and an expansion of farm size are important characteristics of structural change in the agricultural sector of OECD countries, but growth in farm size shows substantial differences across single countries and periods depending on country-specific natural, geographical, historical, social and economic conditions, as well as the policy environment (Bokusheva and Kimura, 2016[32]). Data show that the EU27 agriculture has also experienced a constant trend towards fewer but larger farms. The number of farms has been declining for several decades, dropping from 14.2 million in 2005 to 9.1 million in 2020 (Figure 2.7). In the same period, the average farm size increased from 11 hectares to 17.4 hectares. This trend applies to both EU13 and EU14 countries. There are, however, significant differences between the average farm sizes of the two groups. While UAA per farm in the EU14 was 26.8 hectares in 2020, it was only 9.9 hectares in the EU13 countries. In the EU13, the number of farms decreased by 41.3% between 2005 and 2020, while there was only a 28.1% decrease in the case of the EU14 (Eurostat, 2022[33]).

Various factors can explain those structural trends. These include the low profitability of farming and better job opportunities outside of agriculture, increased productivity (e.g. through technological progress) and an increasing degree of rationalisation due to improved farm machinery, often requiring a larger scale to be efficient. Public policies and the institutional context play a role, especially market price support and coupled payments, which in the past had contributed to encouraging intensification and scale enlargement (EC, 2019[34]; Bijttebier et al., 2018[35]). On the other hand, decoupled direct payments have a more indirect impact on farm structure changes by encouraging farmers to stay in the sector (Chapter 3).

Figure 2.7. Evolution of the number of farm holdings and their average size in the European Union, 2005 to 2020

Notes: UAA: utilised agricultural area. EU14 refers to pre-2004 Member States. EU13 refers to post-2004 Member States.

Source: Eurostat (2022[36]), accessed January 2023.

Increasing value of production and respecialisation

The decrease in the total number of agricultural holdings between 2005 and 2020 is primarily due to the disappearance of farms smaller than five hectares, which make up nine out of ten disappearing farms. At the same time, farms with more than 50 hectares are the only ones that have increased (+9.7%). In the same period, the economic size of the EU farming sector also increased continuously. The total standard output generated by all farms in the European Union increased by 32%, from EUR 267.6 billion to EUR 353.7 billion (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3. Evolution in the number of holdings and standard output according to farm size in the European Union

|

Number of holdings (in millions) |

Standard output (in EUR billions) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total |

2005 |

2020 |

% change |

2005 |

2020 |

% change |

|

Less than 10 ha |

14.2 |

9.1 |

-36.1 |

267.6 |

353.7 |

32.1 |

|

From 10 to 49.9 ha |

11.8 |

6.9 |

-41.4 |

75.8 |

71.7 |

-5.5 |

|

50 ha or more |

1.8 |

1.5 |

-16.5 |

80.1 |

96.3 |

20.1 |

|

Total |

0.6 |

0.7 |

9.7 |

111.7 |

185.7 |

66.3 |

Note: EU27.

Source: Eurostat (2022[36]), accessed January 2023.

While farms larger than 10 hectares increased their average standard outputs, smaller farms’ standard output decreased. The 6.9 million smallest farms below 10 hectares, which represented 76% of the 9.1 million farms in 2020, only accounted for 20% of the European Union’s total agricultural economic output (EUR 71.7 billion). With an average annual standard output of EUR 10 375 (in 2020), most of these farms count as (semi)-subsistence, as many consume more than half of their own production. A further 1.5 million farms with areas between 10 hectares and 49.9 hectares represented 27% of the total standard output (EUR 96.3 billion). By contrast, the largest 677 760 farms with an area of 50 hectares or more were responsible for 53% of the total economic output in the European Union, EUR 185.7 billion, while accounting for 7% of all farms. Those farms are characterised as large agricultural enterprises with an average output of EUR 273 987 per year (Eurostat, 2021[37]).

Along with the changes in farm number and average farm size, the pattern of farm specialisation also changed. Although EU farms continue to engage in diverse activities, they have increasingly moved toward specialisation. This is particularly the case for crop farms, whose share of total farms increased from 43% in 2005 to 58% in 2020. In contrast, the proportion of mixed cropping farms declined from 30% to 19%, while farms specialised in livestock experienced a relatively minor change, dropping from 24% to 22% in the same period (Eurostat, 2021[37]).

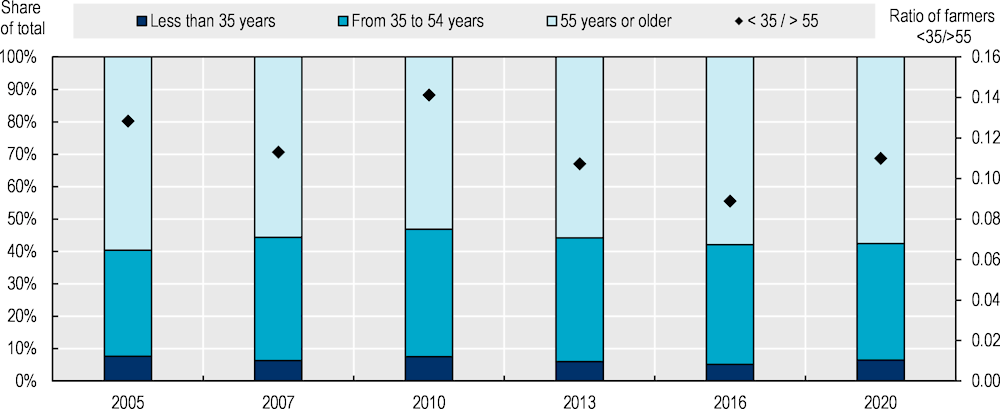

Declining number of farmers and generational renewal

Farmers and those working in the agricultural sector are also facing a structural change. The share of the EU working population employed in agriculture fell from 6.4% in 2005 to 4.2% in 2020. This is equivalent to a 36% decline in annual working units (AWU) (Eurostat, 2022[38]). This labour outflow is mainly driven by the shrinking number of farms and the strive for economies of scale through investments in machinery and technology and larger farms (Maucorps et al., 2019[39]). Nevertheless, agriculture remains an important sector for employment, with 8.2 million full-time equivalents in the sector in 2020. When including temporary or family work, the regular labour force reached 17 million people in 2020. Only 18.7% were in full-time employment on the farm; 81.3% undertook farm work as a secondary or part-time activity. Farming remains mainly a family activity, with 86.1% of those who worked regularly in agriculture being either farmers or family members; hired labour was only 13.9% (Eurostat, 2022[40]).

The proportion of young farmers is also small and diminishing (Figure 2.8), leading to the problem of generational renewal. In 2020, more than half of the farmers in the European Union were at least 55 years old, and between 2005 and 2020, the share of farm managers under the age of 35 decreased in proportion to the overall figure (from 7.3% to 6.5%). However, the latest 2020 figures show some signs of stabilisation or improvement: between 2016 and 2020, the share of farmers under 35 increased by 1.4% and the number of farmers over the age of 35 decreased (Eurostat, 2022[40]).

Figure 2.8. Evolution of the age distribution in farm labour force and the share of young farmers in the European Union, 2005 to 2020

The slow pace of generational renewal in agriculture is of particular concern since young farmers are key to embracing research, innovation and smart agriculture (EC, 2020[42]). They tend to be better educated than older farmers and are more likely to adapt to new production techniques. Younger and middle-aged farmers tend to reach higher economic outputs and cultivate larger areas, while old farmers manage significantly smaller farms in terms of economic output and agricultural land sector (EC, 2019[34]). Young farmers are additionally found to take up more sustainable practices (Brennan et al., 2016[43]) and are, therefore, essential for a sustainable and productive future farming.

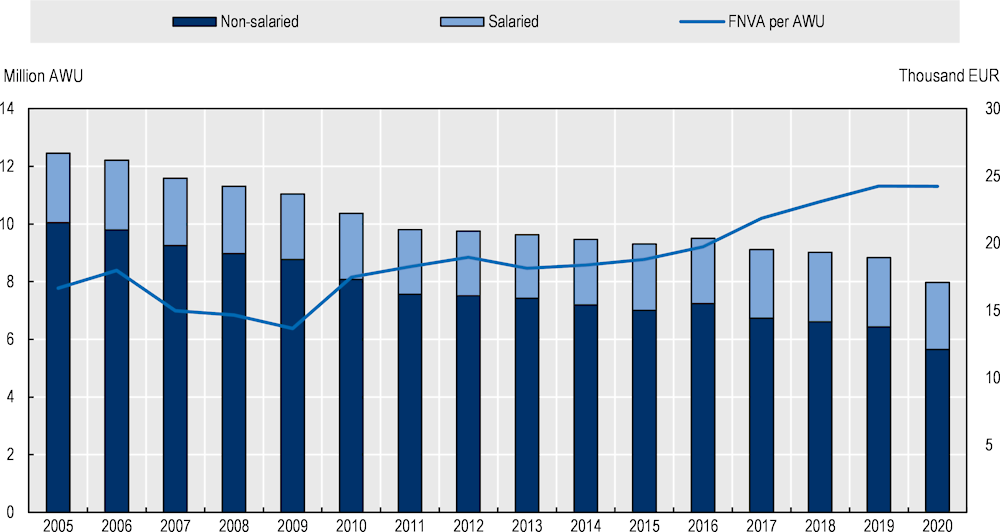

Agricultural income

Ensuring a fair standard of living for farmers is one of the main objectives of the CAP (Chapters 1 and 3). Calculations based on Eurostat data show that EU agricultural income, as measured by entrepreneurial income per family work unit, continues to stay clearly below the average income of the economy, although the gap between farm incomes and incomes in other economic sectors is closing over time (EC, 2022[44]). Nevertheless, the average agricultural income per full-time employee – expressed as average farm net value added per AWU – has been increasing in recent years. Between 2007 and 2020, the income level rose by 48%, from an initial value of EUR 15 989 to EUR 23 649, yet with significant differences among Member States. Only around one-quarter of the total labour input draws a salary, yet the discrepancy between paid and unpaid workers has been declining to a small extent in the past years (Figure 2.9).

Many farmers conduct other gainful activities related to their holdings to increase their income. In fact, almost a quarter engaged in other gainful activities within the sector in 2016, 17% of those as a main activity (Eurostat, 2021[37]). This includes, for example, activities such as agri-tourism, energy production or direct marketing. Consequently, the picture of farmers’ actual farm-related income also remains incomplete, such as the role supplementary income sources play in contributing to their overall income. Although the Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) started collecting such data in 2014, data are still incomplete and non‑representative of the economic performance of farms (ECA, 2022[45]).

The data shown in Figure 2.9 on agricultural income in farming per AWU should be considered as an indication of the income performance of farms, but they should be interpreted with caution when analysing farmers’ standard of living and making comparisons to other sectors of the economy. Many farmers or household members receive earnings from activities beyond agriculture that are not covered by this measure. Particularly, holders of smaller farms often consider farming a minor activity and rely on other income sources outside the sector to raise and stabilise their incomes (EC, 2015[46]). To get a full picture of farmers’ incomes – and thus be able to assess their living standards and make comparisons to other sectors – would require considering the whole disposable income of the farm household. This includes farm-related as well as income from other sources outside the sector (Marino, Rocchi and Severini, 2021[47]; Rocchi, Marino and Severini, 2020[48]).

Figure 2.9. Evolution of agricultural income in the European Union, 2005 to 2020

Notes: FNVA: farm net value added; AWU: annual working unit. EU27. Agricultural income can be expressed as average FNVA/AWU, equal to gross farm income minus the depreciation costs. It takes into account agricultural support on the one hand and income taxes on the other. The measure per AWU allows accounting for the different farm scales and provides a better measure on agricultural labour productivity.

Sources: Eurostat (2022[49]), accessed January 2023; FADN (2022[50]), accessed January 2023.

The most recent data suggest that farm incomes are higher than they have ever been. While COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, among other crises, have decreased EU agricultural output (-3.5%) and increased input prices (e.g. 82.8% for fertiliser) (Eurostat, 2023[51]), entrepreneurial income in EU agriculture has increased by 25% between 2021 and 2022 (Eurostat, 2023[52]), in part due to agricultural support measures implemented by the European Union and its Member States in the wake of the aforementioned crises. This raises questions regarding the extent of the support provided and whether it has exceeded the needs arising from events that have affected the agricultural sector (Matthews, 2023[53]).

As discussed in Chapter 3, one of the key challenges for future agricultural policies will be related to the increased availability of data, since only sound data allow designing effective policies aimed at maintaining farmers’ incomes and assuring a fair standard of living for farmers. Only a few Member States, for example Ireland and the Netherlands, report farm household income data. Furthermore, approaches vary widely and do not allow for comparisons across countries.

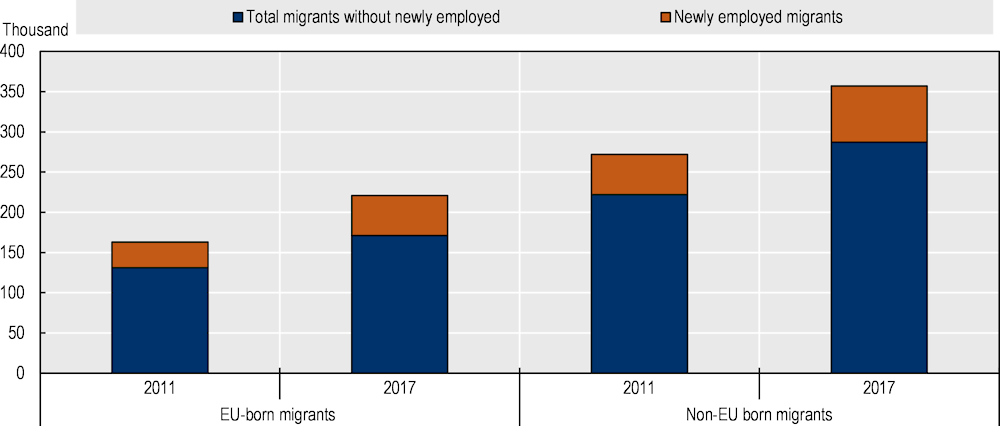

Migrant workers

Although the European Union hosts fewer migrants than other OECD countries, numbers have increased considerably in the past decades. In particular, during the 2000s, the population of foreign-born inhabitants in the European Union increased comparatively faster thanks to a robust immigration rate. Today, this population plays an essential role in the EU workforce (OECD, 2016[54]).

In the agricultural sector, foreign labour, notwithstanding undocumented workers whose number is difficult to quantify, accounts for a sizeable and increasing amount of the agricultural workforce, partially compensating for the outflow of local labour.1 The COVID-19 crisis and the related imposed mobility restrictions on foreign workers highlighted the European Union’s dependence on foreign agricultural workers and their importance to the functioning of the sector (Kalantaryan, Mazza and Scipioni, 2020[55]). Migrants, particularly non-EU born ones, take on an increasingly important role in food production and natural resource management while constituting a strategic asset in combating labour shortages and fostering the sector’s resilience (Nori, 2017[56]).

In 2017, the EU agricultural sector counted 221 000 EU-born and 357 000 non-EU-born migrants, respectively 36% and 31% more compared to 2011 (Figure 2.10). Together, they accounted for 6.4% of total agricultural employment (3.5% in 2011), with a particularly high share in Denmark, Italy and Spain. Most migrant workers in EU agriculture sustain labour-intensive crop production, particularly harvesting fruits, vegetables and horticulture. Between 2011 and 2017, the number of newly employed migrants in agriculture increased significantly, by 56% for EU-born migrants and 40% for non-EU born migrants, to inflows of 50 000 and 70 000 people in 2017 (Martin, 2016[57]; Kalantaryan et al., 2021[58]). Migration flows, however, differ widely across Member countries, as do the activities they perform. In the case of Denmark, for example, most employed migrants in agriculture are from another EU Member State, mainly working in forestry, pig farming and horticulture (Refslund, 2016[59]). Italy and Spain, in contrast, rely on higher numbers of non-EU migrants who work in crop picking on fruit and vegetable farms (Corrado, 2017[60]).

Figure 2.10. Existing and newly employed workers in the European Union, 2011 and 2017

Despite the increasing importance of migrants in EU agriculture, their working and living conditions give reasons for concern. Generally, foreign workers are more likely than locals to work in low-skilled jobs, be employed and follow temporary occupations while receiving lower incomes and facing a higher risk of poverty (Kalantaryan et al., 2021[58]). Limited rights, unsatisfactory working standards and illegality often accompany those conditions, further provoking difficulties in receiving residence permits, operational licenses and general citizenship rights (Augère-Granier, 2021[61]). As discussed in Chapter 3, social conditionality will be an important tool that potentially could raise labour standards in EU agriculture since CAP beneficiaries will have to respect elements of European social and labour laws to receive CAP funds.

The conditions of migrant workers in the EU agricultural sector pose a clear policy need that will become increasingly acute in the coming years as foreign labour inflows increase (OECD, 2022[62]). The consideration of socio-economic conditions and the assurance of social rights compliance, particularly for migrant workers, is therefore essential for the future. However, data availability is a key first step to finding a targeted and adapted policy response.

The role of women

There are many differences in how women and men participate in the agricultural labour force, but generally women are less likely than men to own and manage an agricultural family business in OECD countries (Giner, Hobeika and Fischetti, 2022[63]). According to official statistics, in 2019 women accounted for 40.1% of the total EU27 agricultural labour force (EC, 2019[64]). As many farms are family-run, women often work as family labour that may not be registered in statistics. In addition, women are an essential backbone for EU agriculture, but they often follow seasonal or part-time activities in the lowest paid and most insecure jobs (European Institute for Gender Equality, 2016[65]; European Institute for Gender Equality, 2022[66]).

Current data show that 42% of female agricultural workers are over the age of 65, compared to 29.2% for males – creating a high risk of a widening gender gap in the future (EC, 2021[67]; Kovačićek and Franić, 2019[68]). This comparatively greater share of older women is not least because women in the farms are generally less recognised in the agricultural context than men (e.g. due to lower salaries, less land ownership or lack of farm entitlement), thus making agricultural careers unattractive to younger women.

Wide discrepancies exist between the role of women and men. While they contribute significantly to the sector, women’s role in agricultural decision making and farm and land ownership remains minor. In 2016, only 28.7% of farm managers were female, while the figure increased to 31.6% in 2020, showing a slight improvement. On average, they operate significantly smaller and more diversified farms, with female managers accounting for low shares of the more profitable specialised farming holdings (Eurostat, 2021[37]) In addition, females often undertake assisting functions in which they receive less or no income and, in many cases, are not entitled to social security.

Gender-disaggregated data are often missing, making women’s contributions difficult to acknowledge and assess. A broader range of gender-disaggregated data can contribute to increasing the visibility of women in the sector (Giner, Hobeika and Fischetti, 2022[63]). For example, a significant gender-related data gap prevails in the overarching 2021‑2027 Multiannual Financial Framework policies and programmes. Although the European Commission’s impact assessment guideline puts attention on gender equality, gender analysis is incorporated in only a few programmes with small consideration (the CAP assessment, for example, provides a brief reflection on gender) (ECA, 2021[69]). The upcoming transition from the FADN to the Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN) will include a broader range of gender-disaggregated data, but broader assessments of the role of households in EU agriculture and rural areas are needed once more information on the range of new variables is available.

2.2.3. Innovation

The Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy identifies research and innovation as key to accelerating the transition to sustainable, healthy and inclusive food systems across the European Union. Fostering knowledge and innovation is also a cross-cutting objective of the CAP 2023-27 and food, bioeconomy, natural resources, agriculture and the environment are important elements in the European Union’s research and innovation policy Horizon Europe. The innovation dynamics is a complex process involving multiple actors and policy levers, as analysed in Chapter 5. This section introduces the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System (AKIS) as an approach to better connect agricultural practice and science and boost knowledge generation, exchange and innovation.

The European Union’s AKIS is very diverse, involving numerous actors at the EU, national and regional levels

The concept of AKIS has gained increasing importance in the European Union in the past decade. It aims to benefit farmers, as well as society, in particular by empowering them to co-create and adopt innovative, sustainable agricultural practices. Farmers, as the centrepiece of the AKIS, are key to fostering modernisation, innovation and knowledge flows in the agricultural sector (EU SCAR AKIS, 2019[70]).

The complexity of the EU AKIS is partly due to the existence of 27 national AKIS and their regional AKISs, with their set of actors and initiatives operating at the EU level within a single European common knowledge and innovation area. Each EU Member State has developed an individual AKIS that corresponds to its particular situation, actors and needs and is embedded in national laws, institutions and cultures. So far, national AKIS within the European Union differ greatly from each other, for example in terms of the fragmentation and strength (invested budgets) as well as in the number of actors, the type of institutions, governance levels and systems, funding types, and the characteristics of the farming sector. The systems thus require flexible, country-adapted framework conditions offering co-ordinated arrangements, in particular in countries with a strong regional structure such as Germany, Italy and Spain, and a national-wide approach in countries with a more centralised system, e.g. Cyprus and Finland (PROAKIS, 2015[71]).

In view of these differences between national AKIS, the European Commission’s (EC) role is to foster innovation by providing an overarching regulation on Member States’ AKIS strategic approach and a number of services to generate and exchange knowledge across countries, thus allowing for cross-border spillover effects in a larger innovation geographical area (Détang-Dessendre et al., 2022[72]). The scale and interconnectedness of the AKIS affect its capacity to find solutions, exchange experiences and knowledge, and facilitate adoption. The EU common knowledge and innovation area can help enhance the knowledge flows across regions and countries. Spain provides an interesting example of a fragmented agri-food research landscape where regional research centres vary greatly in terms of research capacities and areas of interest but are well connected outside Spain through Horizon Europe and other European programmes. However, Spain added a number of national efforts to the regional initiatives to interconnect the regions, such as regular networking events, national technology platforms and national European Innovation Partnership innovation projects, national focus groups and synergies through research legislation which increase the impact in agricultural practice.

2.3. General policy environment

2.3.1. Trade policies

The European Union is the largest single market in the world, and its treaties and legal frameworks ensure a functional internal market, with full free trade and competition across all Member States. The European Union manages its trade and investment relations with non-EU countries through its common commercial policy, whose rules are set out in Article 207 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (EU, 2012[73]). Extra-EU trade is an exclusive competence of the European Union, not a shared competence with the national governments of its Member countries. This means the EU institutions make laws on trade matters and negotiate and conclude international trade agreements. The common commercial policy covers trade in goods (including agriculture) and services; the commercial aspects of intellectual property, such as patents; public procurement; and foreign direct investment and trade defence (such as anti-dumping measures). The European Union is a founding member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and promotes trade through numerous bilateral trade agreements and unilateral trade preferences to developing countries. Despite the reduction in market price support to agriculture in the last decades, the European Union’s trade policies still protect agro-food products more than other goods and services: for example, the 2021 simple average applied most favoured nation rate for agricultural goods was 11.7%, compared to 4.1% in the case of non-agricultural goods (WTO, 2022[74]) (Chapter 3 provides a more detailed discussion of agricultural trade policy).

In October 2015, in its Communication on “Trade for All”, the European Union laid out its vision for a more responsible approach to adapting EU trade policy to new economic realities, in line with its foreign policy. The top priority remains to re-energise the WTO and pursue bilateral and regional trade agreements with a high level of ambition. The Communication describes free trade agreements as a “laboratory for global trade” and commits to developing future WTO proposals to “fill the gaps in the multilateral rulebook and reduce fragmentation from solutions achieved in bilateral negotiations”. More recently, the European Union has continued to support the multilateral trading system, including through its engagement towards the adoption of a Declaration on Food Security and an Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies at the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference (June 2022), its active promotion of several initiatives on trade and the environment, and its commitment to reforming the WTO (EEAS, 2022[75]).

The European Commission monitors the progress of 42 trade agreements with 74 partners (EC, 2022[76]), which in 2021 accounted for over EUR 1 trillion in EU exports and over EUR 800 billion in imports. In 2021, over 44% of the European Union’s trade took place with partners with trade agreements in place, and an additional 3% corresponds to trade agreements that are yet to be adopted or ratified (such as the EU-MERCOSUR agreement, for which negotiations were concluded in 2019). In the agri-food sector, free trade agreements accounted for roughly 35% of EU agri-food trade with third countries – 30% and 40% of total EU agri-food exports and imports, respectively.

The United Kingdom’s decision to withdraw from the European Union has been one of the most significant disruptions to EU trade policies. After 31 December 2020, the free movement of people, goods, services and capital with the European Union ended, and EU trade agreements no longer applied to the United Kingdom. The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement – concluded on 24 December 2020 and in force since 1 May 2021 – lays down the rules governing the bilateral relation. Of relevance to agriculture, the trade component of the agreement includes duty-free and quota-free imports on all goods that comply with rules of origin provisions (EU and UK, 2020[77]). The OECD assessed the impacts of this agreement. The results of the simulations carried out with the OECD METRO CGE model show that real GDP losses in the European Union in the worst-case scenario are expected to be around 0.6% in the medium term but would vary markedly across countries (van Tongeren et al., 2021[78]). EU Member States are expected to import fewer professional services such as financial services and insurance, communication, and other business services. UK exports are estimated to fall by about 6.3% and imports by 8.1% in the medium term. The overall medium-term loss in UK real GDP could amount to 4.4%. The study also shows that agriculture is among the top sectors facing increased trade costs, especially due to non-tariff measures, such as technical barriers to trade and sanitary and phytosanitary measures, as well as costs from rules-of-origin and border-crossing costs.

In addition to the bilateral and regional trade agreements, the European Union grants unilateral trade preferences to developing countries under its Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP). The EU GSP comprises three arrangements: the “standard” GSP, which grants lower import duties to about two-thirds of tariff lines from countries classified as low- and lower middle-income countries and that do not have preferential access to the EU market through other agreements; the GSP+, which fully eliminates import duties for the same goods for countries that implement a number of international conventions on human rights, labour, governance and other sustainable development aspects; and Everything but Arms, which grants duty-free and quota-free access to all imports from least developed countries, except arms and ammunition. The current GSP Regulation will expire on 31 December 2023, and the European Union is revising its GSP to enter into force in 2024.

On 18 February 2021, the European Commission adopted the Communication “Trade Policy Review: An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy” (EC, 2021[79]). This Communication sets out a new trade strategy that takes into account the lessons learnt from the COVID-19 crisis, focusing on economic recovery, climate change, growing international tensions and greater recourse to unilateralism. The Communication includes several elements of relevance to food and agriculture, such as the proposal to add a chapter on sustainable food systems in future trade agreements and to require that imported products comply with certain production requirements through autonomous measures” (see Chapter 3 for further details).

2.3.2. Competition policy

The European Union plays a determinant role in the competition policy in the internal market. Competition policy aims to encourage companies to offer consumers goods and services on the most favourable terms. It encourages efficiency and innovation and reduces prices. Beyond regulation of exclusionary practices such as anti-trust, EU competition policy seeks fairness as a factor in determining what is anti-competitive, for example through regulation of unfair trading practices and exemptions.

The disparity in the number and size of farmers compared to inputs of suppliers, food retailers and other food chain actors has long created tensions between the CAP’s objectives and EU competition policy. For decades CAP regulations have provided for derogations from EU competition rules for some sectors (e.g. dairy, pork, sugar, fruit and vegetables, wine) to allow farmers to co-operate through producer organisations, their associations and interbranch organisations. The Omnibus Regulation (EU) No. 2017/2393 extended to all production sectors the possibility for producer organisations and associations of producer organisations to collectively negotiate contracts for the supply of agricultural products, including price contracts.

The two major impacts of competition policy on the EU agri-food sector relate to the external competitiveness of the sector and the well-functioning of the EU internal market and its links with global food systems. A Commission-funded report in 2016 on “The competitive position of the European food and drink industry” (ECSIP, 2016[80]) provided an assessment of the competitive position of the food and drink industry, taking into account the 2008-10 economic crisis. The study also investigated how the food and drink industry could strengthen its position in the coming years. The European Union showed a positive development on the trade-related indicators (relative trade advantage and world market share) in the light of the weakening of the other indicators like value added and labour productivity. The likely explanation was the ability of EU industry to differentiate itself from other regions by offering a higher quality next to differentiated products, meaning that the impact of developments in the cost base, like labour productivity, had less of an impact on the international competitive position. The report commented that the focus on high-quality products is supported by the EU regulations and the high food safety requirements set by EU food law, thereby conferring a comparative advantage for EU manufacturers.

In June 2015, the European Commission established the High-Level Forum for a Better Functioning Food Supply Chain, which led to various initiatives regarding unfair trading practices in the food chain and retail sectors. In 2019, the forum adopted its final document (HLF, 2019[81]), which provides two sets of policy recommendations: 1) a list of barriers affecting the single market of food and concrete ways to address them; and 2) an assessment on the proportionality of cases of compositional differentiation of identically branded food products.

To improve the position of both farmers and small and medium-sized businesses in the food supply chain, the European Union has adopted legislation that bans 16 unfair trading practices. EU Directive 2019/633 distinguishes between “black” and “grey” practices. Whereas black unfair trading practices (e.g. short-notice cancellations of perishable agri-food products, unilateral contract changes by the buyer, risk of loss and deterioration transferred to the supplier, misuse of trade secrets by the buyer) are prohibited, no matter the circumstances, grey practices (e.g. return of unsold products; payment of the supplier for stocking, display and listing; payment of the supplier for promotion, marketing and advertising) are allowed if the supplier and the buyer agree on them beforehand in a clear and unambiguous manner. The Directive also protects weaker suppliers against stronger buyers, which includes any supplier of agricultural and food products with a turnover of up to EUR 350 million with differentiated levels of protection provided below that threshold. This covers farmers, producer organisations and distributors below the threshold. It also applies to suppliers and buyers located outside the European Union, provided one of the parties is located within the European Union.

2.3.3. Cohesion policy

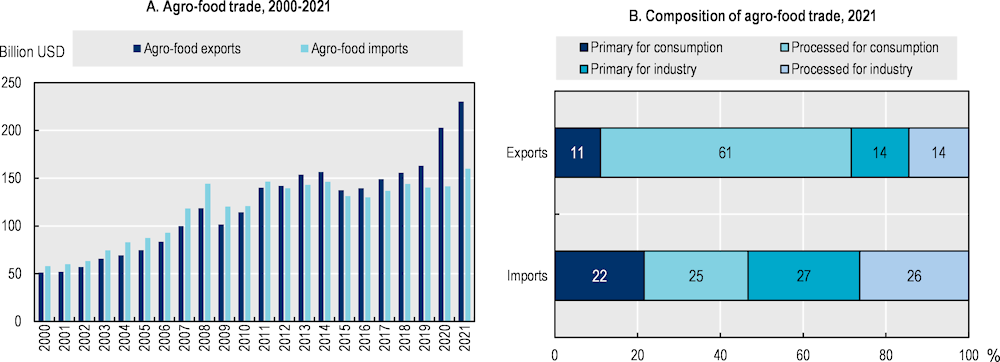

European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) are the European Union’s main investment policy tool to support job creation and sustainable economic growth. In particular, Cohesion Policy – funded through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), the European Social Fund (ESF) and the Cohesion Fund – accounts for a substantial portion of public investment in the European Union and plays a critical role in achieving EU and EU-Member State development objectives.

In the 2014-20 programming period, EUR 461 billion, or over half of the total EU budget, was allocated to the ESIF, which supports over 500 programmes (EC, 2023[82]). This allocation represents a 4.4% increase over the previous programming period in which the planned amount for the ESIF was EUR 441 billion (EC, 2022[83]).

The funds make it possible to advance national- and subnational-level investment in competitiveness, growth and jobs in EU Member States. The majority of the ESIF – EUR 351.8 billion – is dedicated to funding EU Cohesion Policy through the ERDF, the ESF and the Cohesion Fund (Figure 2.11). In particular, this policy aims to support balanced economic, social and territorial development and cohesion across its Member States. Administrative capacity has been identified as a fundamental factor behind the performance of this policy (OECD, 2020[84]). All these funds should work together to support economic development across all EU countries, but while every EU region may benefit from the ERDF and the ESF, only the less developed regions may receive support from the Cohesion Fund. ESIF funds also include the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, which focuses on resolving the particular challenges facing rural areas (Chapter 3).

As for the 2021-27 programming period, the European Commission has proposed an allocation of EUR 373 billion to fund the Cohesion Policy, channelled through the ERDF, the European Social Fund Plus (ESF+) and the Cohesion Fund (ECA, 2019[85]).

Figure 2.11. Overview of the European Structural and Investment Funds for 2014-20

The investment financing provided through the ESIF is significant for a number of reasons. First, while it aims to reduce inequalities between EU countries, it can also help reduce disparities within countries through targeted and, ideally, place-based investment. Second, encouraging productivity growth is critical to ensuring greater well-being, as it can have a positive impact on income and jobs, health, and access to services. As reported in the latest OECD Economic Survey for the European Union (OECD, 2021[86]), since 2000, achievements on regional convergence have been mixed: regional disparities in GDP per capita declined significantly until the global financial crisis, but much more slowly afterwards. Moreover, regional inequalities within countries have remained broadly flat, even increasing somewhat. This may be explained by the different performance of rural areas, small cities or metropolises: the proportion of regions that are among the 25% richest is much higher among metropolitan regions than among non-metropolitan or remote ones.

Different sets of rules at EU level and different managing agencies and responsible political authorities at national or regional levels have often led to poor co-ordination between Cohesion Policy and rural development programmes (Kah, Georgieva and Fonseca, 2020[87]). However, since many lagging regions still have a large agricultural sector, exploiting the complementarities between the two policies and strengthening their co-ordination could lead to efficiency gains and administrative simplification (OECD, 2021[86]).

2.3.4. ICT and new technology policies and regulations

Digitalisation, and the twin digital and green transitions in particular, are high on the EU agenda, including in the field of agriculture and rural areas, as it is well reflected in multiple strategic documents under the European Green Deal (EC, 2019[88]) and in the European Commission priority “A Europe fit for the digital age” (EC, 2022[89]). This includes, for instance, the F2F Strategy (EC, 2020[90]), the Organic Action Plan Plan (EC, 2021[91]), the European Strategy for Data (EC, 2020[92]), and the Long-term Vision for Rural Areas, which includes a flagship on ”rural digital futures” and actions to continue suppor ting digitalisation of agriculture in its action plan (EC, 2021[93]).

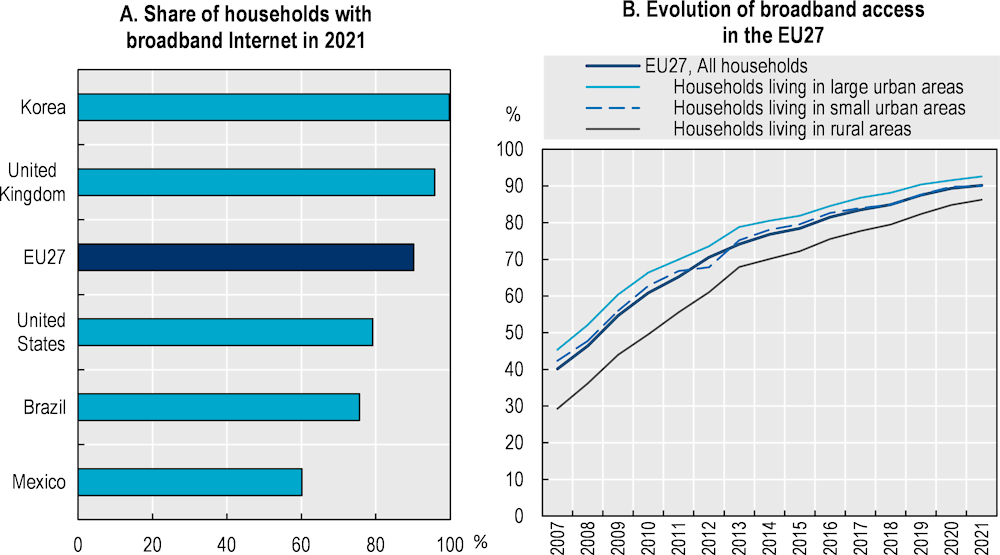

The European Union currently reaches 90.2% of households with broadband Internet access at home: this is less than 10% below the most advanced country, Korea, where almost 100% have broadband access, but is significantly higher than in the United States (79.2%) (Figure 2.12, Panel A). The share of households with such access more than doubled during the decade 2007-17 (from 40.2% to 83.5%) and continued to grow, albeit at a slower pace, to reach around 90% of households in 2021. Although the gap between urban and rural areas has been gradually closing, in 2021, 86.3% of rural households had broadband Internet access at home, 6.3 percentage points less compared to households living in large urban areas (Figure 2.12, Panel B). However, rural areas are lagging behind in coverage with very high-capacity network (EC, 2022[94]).

Several policy instruments at different governance levels support the promotion of and the uptake and effective deployment of digital technologies in agriculture and rural areas. As discussed in Chapter 5, the CAP includes many tools aimed at the “enabling potential” of digital technologies to contribute to sustainability, competitiveness and enhanced quality of life. This is reflected in the so-called cross-cutting objective of “Modernising the sector by fostering and sharing knowledge, innovation and digitalisation in agriculture and rural areas, and encouraging their uptake”.

Figure 2.12. Share of households with broadband Internet access at home

Other EU programmes supporting digitalisation in agriculture and rural areas include the Digital Europe Programme (DIGITAL), a new EU funding programme focused on bringing digital technology to businesses, citizens and public administrations. In March 2021, the European Commission also presented a vision and avenues for Europe’s digital transformation by 2030 (EC, 2021[96]). In addition to the focus on skills, digital transformation of businesses, and secure and sustainable digital infrastructures, the Digital Compass for the European Union’s digital decade also includes the digitalisation of public services.

As shown in the next section, following a cross-sectoral approach, the digital transformation in the European Union is also supported by legal initiatives to increase the better use and reuse of data, as announced in the European Strategy for Data, including the EU Data Governance Act. Trust is crucial for the adoption of these technologies (McFadden, Casalini and Antón, 2022[97]). Privately held data supplemented by publicly held data will present new opportunities for monitoring and evaluation and will contribute to achieving the objectives of the EGD and CAP.

2.3.5. Data-related initiatives

The European Commission has presented a number of initiatives to support the achievement of data-related goals. The Communication on “A European Strategy for Data” calls for accelerated action due to the growing volumes of data, the importance of data for the economy and society, and transformative practices data could fuel (EC, 2020[98]). The strategy aims to unlock data from their silos to increase their use and re-use, thereby creating a single market for data so that it can flow freely within the European Union and across sectors to the benefit of citizens, business and public administrations. The realisation of the vision for a “genuine single market for data” includes actions pursuing a cross-sectoral governance framework for data access and use and calls for both the Data Governance Act, adopted by the parliament and Council in May 2022, and the Data Act (proposed regulation) (EC, 2022[99]). Furthermore, in the European Strategy for Data, the European Commission announced the creation of a common European agricultural data space,2 which could induce an innovative data-driven ecosystem by establishing a neutral platform to pool agricultural data.

While the Open Data Directive regulates the public sector-held data that fall under the open data category (EC, 2019[100]), the Data Governance Act extends its scope to both personal and non-personal non-open data and aims to increase data availability by fostering data sharing through regulating data intermediaries and data sharing for altruistic purposes. The initiative intends to increase confidence in data sharing by establishing safeguards and reducing technical barriers to use the data in a variety of sectors, including agriculture (EC, 2022[101]). The Data Governance Act, which will be applicable from September 2023, will also benefit the use of data for research. It has been identified as a positive development for researchers, which helps to overcome the challenges of sharing sensitive data between researchers induced by the EU General Data Protection Regulation3 (Shabani, 2021[102]).

The Data Governance Act proposes a set of rules to determine who can use and access data generated by the use connected devices, with the goal of making more data available. The European Commission’s intention is that the Data Governance Act stimulates competition and innovation, new opportunities to use services relying on data access and better access to devices’ data (EC, 2022[103]). This should strengthen users’ rights concerning the digital data they generate by handling objects or devices and facilitate digitisation and value creation by allowing users to take full advantage of data. The Data Governance Act also has an implication for the EU farming sector since it aims to address the information asymmetry resulting from the transfer of data generated by farm machinery to the manufacturer, who could use information about the farm’s performance to their advantage (EC, 2022[104]).

Many EU policies and research projects draw on agricultural statistics, e.g. CAP, including cross-compliance, agri-environmental measures, and rural development programmes (handled mainly by the European Commission’s Directorate-General [DG] for Agriculture and Rural Development); air quality-related directives, including national emissions ceiling and integrated pollution and prevention control (handled mainly by the DG for Environment); or food safety, plant protection, animal health and animal welfare regulations (handled mainly by the DG for Health and Food Safety) (EC, 2015[105]).

Eurostat provides a broad range of data and statistics on Europe and co-ordinates statistical activities within the European Union and the European Commission. Under the European Statistical System, Eurostat co-operates with national statistical institutes and other statistical authorities of Member States for statistics to be reliable and comparable. This partnership not only extends to EU Members, but encompasses the entire European Free Trade Association and candidate countries. The European Statistical System provides the framework for harmonising statistics and co-operation with national statistical authorities, and its work has extended from main EU policy areas to a near to complete coverage of all statistical fields.

Eurostat’s agricultural statistics include more than 50 different data sets covering thematical areas such as farm structure, crop and animal production, economic accounts for agriculture, agricultural prices, organic farming or agri-environmental characteristics. The data collection architecture is based on the Agricultural Census and Farm Structure Surveys. While the Agricultural Census is carried out once every ten years (most recently in 2020), the Farm Structure Surveys, a large-sample survey, take place every three or four years. Regulation (EU) 2018/1091 on integrated farm statistics (European Parliament and European Council, 2018[106]) established the legal framework for agricultural statistics in the European Union. Subsequent regulations offer possibilities to define the list of variables and their description for the following reference periods. For instance, Regulation (EU) 2021/2286 introduces several questions on the use of precision technology on farms (EC, 2021[107]).

Other data-related initiatives relevant to the farming and food sector include the stakeholder code of conduct on agricultural data sharing, which provides guidance on agricultural data use and defines roles and processes in agricultural data sharing, to which Copa-Cogeca, the umbrella organisation for European farmers and co-operatives, adheres. It not only addresses questions of data ownership, but also establishes principles on privacy, security and liability (Copa-Cogeca, 2018[108]). Additionally, European data-relevant policies in the agricultural sector may benefit from the joint declaration of co-operation “A smart and sustainable digital future for European agriculture and rural areas”. Signed by 26 EU Member States, it aims to strengthen research, innovation and data infrastructure in the field of agriculture. The signatories express their support for initiatives encompassing the CAP’s transition towards a result-based policy, the promotion of EIP-AGRI, increasing uptake of digital technologies and driving efforts to strengthen AKIS (EC, 2019[109]).

Horizon Europe may also support data-related initiatives. Work under Cluster 4 “Digital, Industry and Space”, which pursues a cross-sectoral approach, is relevant for developing digital technologies which can later be capitalised in a sector-specific context under Cluster 6 “Food, Bioeconomy, Natural Resources, Agriculture and Environment”. The key issues addressed in the first work programme 2021/22 concern the support of sustainable agricultural production and the development of data-based solutions for the sector. In addition, Horizon Europe refers to many specific challenges, such as the use of digital tools on small farms, the application of blockchain or the assessment of the performance of digital technologies. Furthermore, the Commission has also proposed a new large-scale European Partnership “Agriculture of Data” to be set up under Horizon Europe. It is to support the development of solutions for the sustainability of agricultural production and strengthen the capacity to monitor and evaluate policies. For this purpose, the partnership will generate EU-wide data sets and information by harnessing the potential of digital technologies combined with Earth observation and other environmental and agricultural data (EC, 2022[110]).

The European Commission approaches both data and digital tools in agriculture in parallel, highlighting that the former relies on the latter. To draw on this, further development and implementation of digital tools in agriculture rely on enhanced data collection, harmonisation and management. Strengthening digital components within AKIS could lead to gains in farmers’ abilities to analyse business models and performance through digital tools, and increase farmers’ willingness to supply the data needed to maximise the technologies’ effectiveness.

2.3.6. Food system initiatives

As discussed in Chapter 1, with the primary objective of meeting the EGD’s “healthy and affordable food” goal, the F2F Strategy aims to pave the way to formulating a more sustainable, holistic food policy through which the European food system would accelerate its transition to sustainability. The F2F was accompanied by the Biodiversity Strategy, another key component of the EGD with direct implications for the CAP, and on its future role of ensuring a competitive as well as socially and environmentally sustainable farming sector.

The food system-driven approach to policy making is structured towards the interaction between the multiple policy areas, such as agriculture, the environment and health, that share links to food systems (OECD, 2021[111]). The F2F Strategy sets out an action plan with actions for the food chain actors “between the farm and the fork” and beyond. The nature of those actions is diverse, both legislative and non-legislative, and includes voluntary measures. Trade policy will also be used to support and be part of this transition. The European Union will seek to ensure that there is an ambitious sustainability chapter in all EU bilateral trade agreements (EC, 2021[79]).

The F2F Strategy underlines the importance of consumer behaviour change in food system transformation and climate change mitigation. Among the measures advocated are empowering consumers by better front-of-pack nutrition labelling; strengthening educational messages in schools around sustainable eating; promoting food-based dietary guidelines that incorporate sustainability aspects and encourage Member States to use fiscal policy tools to promote healthy and sustainable diets; an active change in food environments in institutions, including minimum mandatory criteria for sustainable food procurement by schools, hospitals and other public institutions; and setting a legally binding target to reduce food waste.

Furthermore, the strategy recognises the importance of complementing domestic actions with an external dimension designed to promote global action, to avoid externalising the negative environmental impacts of EU consumption and to use access to the EU market as leverage to raise global standards (Chapter 3, Section 3.3.2).