This chapter provides an overview of the developments of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) from its establishment to the most recent 2023-27 reform, together with an analysis of the evolution of support to the EU farming sector up to 2022, based on OECD Producer Support Estimate and related indicators. Successive CAP reforms have led to a significant drop in the overall level of support and the changes in its composition with greater market orientation and increasing integration of environmental and climate objectives. Despite substantial reforms, most-distorting and potentially most environmentally harmful forms of support still represent nearly a quarter of support to producers. The chapter also provides an overview of EU agricultural trade policies and a more in-depth analysis of CAP instruments and their relation to productivity and resilience objectives.

Policies for the Future of Farming and Food in the European Union

3. The agricultural policy setting

Abstract

Key messages

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), the central agricultural policy package in the European Union, is broken down into two categories of measures: Pillar 1 and Pillar 2. CAP Pillar 1 finances direct payments to farmers and market support measures, while CAP Pillar 2 co-finances rural development activities together with Member States. The budgetary process largely pre-allocates CAP amounts between Member States based on history.

Successive agricultural policy reforms in the European Union have significantly changed how support is delivered to farmers. Levels of trade protection and producer support have been reduced since the mid-1990s, and new instruments, such as payments that do not require production, have replaced price support policies. Overall support to producers significantly decreased from 38.4% of gross farm receipts in 1986-88 to 18.8% in 2019-21.

The evolution of support shows direct progress towards market orientation, which is reflected in the presence of less production and trade-distorting measures, as well increasing integration of environmental and climate objectives, reflected in the increasing scope of both mandatory and voluntary input constraints that are attached to payments.

Despite substantial reform of support for the sector, most-distorting and potentially most environmentally harmful forms of support still represent 23.1% of support to producers.

Direct payments make up the bulk of CAP spending. These are mostly decoupled from production and are an important part of farm income, but are not targeted to household income and are not the most efficient tool for achieving productivity and socio-economic objectives. They can slow structural and generational change and could weaken renewal.

Although the ongoing process of conversion of the Farm Accountancy Data Network to the Farm Sustainability Data Network (FSDN) is a positive development, the paucity of data on farm household income, as well as on the environmental and social sustainability performance of farms, may undermine the capacity to design, implement and monitor current and future EU agricultural policy to target and deliver its objectives on the ground.

The new delivery model for 2023-27 introduced a significant change in the governance of the CAP. Combined with the ambitious environmental goals of the European Green Deal (EGD), the 2023-27 CAP has the potential to ensure that the agriculture sector contributes to the European Union’s global sustainability goals, but this will ultimately depend on the individual efforts of Member States.

The CAP is one of the founding policies of the European Union and has significantly evolved over time. This chapter analyses how successive agricultural policy reforms in the European Union have progressively and significantly reduced levels of government support and changed how it is delivered to farmers. Section 3.1 provides an overview of agricultural policy reforms since the Treaty of Rome in 1957, as well as an overview of the main CAP budget mechanisms. Section 3.2 provides an analysis of the level and composition of support using OECD indicators of support, in particular the Producer Support Estimate (PSE), while Section 3.3 provides an overview of EU agricultural trade policies. Section 3.4 is dedicated to a more in-depth analysis of the past CAP instruments related to productivity and resilience objectives, while Section 3.5 examines the CAP 2023-27, highlighting what is new relative to the previous CAP, especially the new delivery model. The final section reviews policy pathways for the programming period post-2027.

3.1. Agricultural policy framework and objectives

3.1.1. Overview of CAP developments

The CAP has been the European Union’s agricultural policy framework since its institution in 1962, although the mix of policy instruments has evolved substantially over time (Table 3.1). As highlighted in Chapter 2, since its establishment, membership to the European Union has considerably enlarged, almost doubling in 20 years, from 15 countries in 1995 to 25 in 2004, 27 in 2007 and 28 in 2013. Following the United Kingdom’s exit in 2020, there are now 27 EU Member States. While the Common Market has become larger and more diversified, environmental and societal concerns around agricultural production practices and food processes have become more prominent in the policy debate.

As for many other policy areas, agricultural policy is a shared competence between the European Union and Member States under the EU Treaties. Member States exercise their own competence where the European Union does not exercise, or has decided not to exercise, its competence. However, the European Union has always intervened more extensively in agricultural policy than in other areas. Agriculture is one of the few areas where the treaties establish a Common Policy. The basic framework of rules is set down in the CAP established under Article 38 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Tracy, 1989[1]).

The Treaty of Rome that established the European Community outlined the CAP in 1957 (OECD, 2011[2]; European Parliament, 2021[3]); European Parliament, 2021[170]). Agriculture made up a much larger share of Europe’s economy at that time, and the income gap between rural and urban households was increasing. Moreover, the region was a net food importer with concerns about securing adequate food supplies during the Cold War (Grant, 2020[4]).

The founding principles of the CAP include market unity, community preference and financial solidarity. Its objectives set out in Article 39 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union are to increase agricultural productivity by promoting technical progress, and thus to ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural population; to stabilise markets; to ensure the availability of supplies; and to ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices. These objectives have not changed since the CAP was launched over 60 years ago. In practice, the CAP now addresses additional objectives such as the environment, climate change, rural development and animal welfare, but these Treaty objectives remain as the legal statement of the policy’s objectives (Chapter 1, Box 1.1). Measures targeting these objectives were originally financed by the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund.

Table 3.1. Overview of the most recent CAP reforms

|

Years |

Main milestones |

Key policy features |

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-1992 |

Market support phase CAP financed by the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund (EAGGF), European Communities with 12 members1 |

|

|

1992-1999 |

1992 (MacSharry) Reform CAP, EU Expansion 1995 (Austria, Finland, Sweden), Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture |

|

|

2000-2002 |

Agenda 2000 CAP Reform CAP divided into Pillar 1 and Pillar 2 (Rural Development) |

|

|

2003-2008 |

2003 (Fischler) Reform (also known as the “Mid‑term Review”) CAP Pillars 1 (financed by European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and 2 (financed by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development EAFRD), EU Expansion 2004 (the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia) and 2007 (Bulgaria and Romania) |

|

|

2009-2013 |

2009 (Fischer Boel) Reform (also known as “Health Check”) CAP Pillars 1 and 2 |

|

|

2014-2020 |

2013 (Ciolos) Reform CAP Pillars 1 and 2, EU Expansion 2013 (Croatia) and Contraction 2020 (United Kingdom) |

|

|

2021-2022 |

Transitional rules |

|

A key achievement of the CAP has been the creation of a free agricultural market without tariffs and other restrictions on the movement of foodstuffs within the European Union as well as the harmonisation and mutual recognition of regulations that might act as trade barriers, as part of the single market that was completed in 1992. Rules on state aid prevent distortions in competitive conditions between farmers in different Member States. Agricultural markets and practices are also influenced by environmental and health legislation.

From the CAP’s institution until the 1990s, support prices were high compared to world market prices due to tariffs and other trade measures. Combined with an unlimited buying guarantee, European farmers produced increasing surpluses. The budgetary cost of these policies became increasingly high, leading to measures to limit expenditure in the 1980s that included quantitative production restrictions in the form of quotas on milk production.

The CAP’s first major reform occurred in 1992, in conjunction with negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and following the result of the US-EU oilseeds panel. The MacSharry Reform brought about a major shift: instead of supporting production, the regime shifted to supporting producer incomes directly through area payments, avoiding surpluses and reducing overall expenditures (European Parliament, 2021[5]).

The Agenda 2000 reform further aligned EU and world prices, offsetting the reduction of price support with increased direct aid to producers (European Parliament, 2021[5]). In addition, the Rural Development Regulation was introduced as Pillar 2 of the CAP, and the first environmental cross‑compliance conditions were required. As discussed in Chapter 4 (Section 4.3.1), cross‑compliance aims at making European farming more sustainable by creating a link between the full payment of support and the EU standards for public, plant and animal health and welfare.

The 2003 Fischler Reform introduced the single payment scheme, decoupling most support from any requirement to produce (European Parliament, 2021[5]). For most of the Central and Eastern European countries that acceded to the European Union in 2004 and 2007, the decoupled payments were made under the Single Area Payment Scheme. The reform included further cross-compliance and modulation, more financial discipline, and splitting the budget into two separate funds for Pillar 1 and Pillar 2.

Measures taken under the 2009 Health Check sought to continue the direction of the 2003 reform. Decoupling of aid continued and nearly all payments (with the exception of suckler cow, sheep and goat premia) were transformed into decoupled direct payments: the single payment scheme. It further reduced market intervention for a number of products, abolished set-aside and announced the phasing out of milk quotas.

The CAP 2014-22, while in many ways the continuation of the CAP 2007-13, offered a number of novel features (OECD, 2017[6]), including a new system of decoupled payments with seven components; the introduction of safety nets in case of market disruption or price crisis; as well as a more integrated, targeted and territorial approach to rural development (Section 3.4). The main policy tools of the CAP 2014-20 are analysed throughout the study since they applied until 2022.

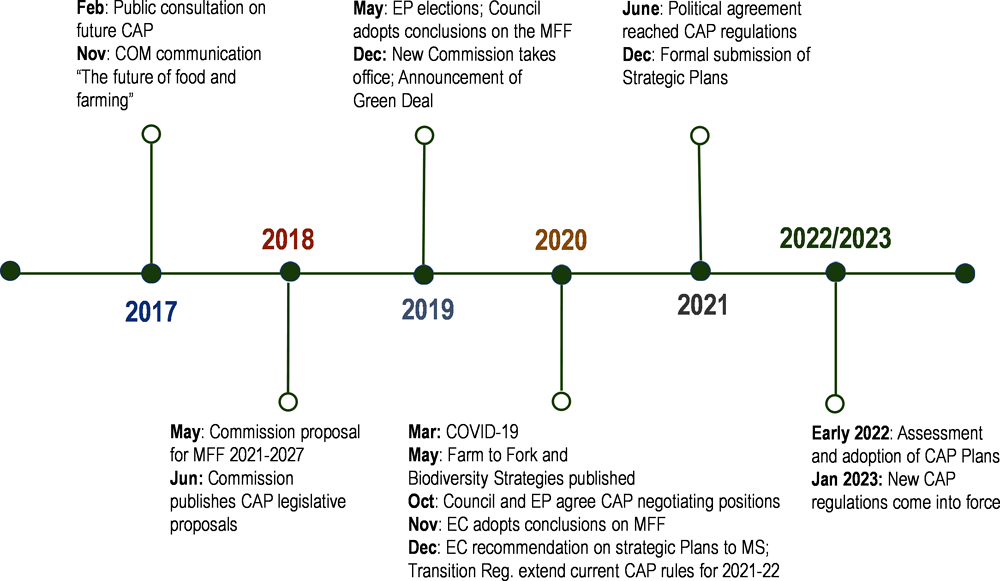

Based on a 2018 proposal from the European Commission, the political agreement on the current reform (CAP 2023-27) was formally adopted in December 2021, with new legislation covered later in the chapter. This reform entered into force in January 2023 after transitional rules that allowed the continuation of the CAP 2014-20.

3.1.2. The budget process

The CAP is organised into two pillars. Pillar 1 finances direct payments to farmers as income support as well as some market measures and is fully funded by the European Union through the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF). Pillar 2 finances rural development activities, including structural measures and agri-environment-climate schemes through the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), but requires co-financing by Member States. Member States programme EAFRD expenditures in national or regional rural development programmes that reflect their specific priorities and needs within a menu defined by the European Commission. Some principal differences in the management of the two funds include:

Expenditure under the EAFRD was programmed against specific objectives, whereas this was not the case for EAGF expenditure on direct payments.

Expenditure under the EAFRD only partially finances rural development interventions under shared management, with Member States required to make a co-financing contribution.

The EAGF operates on an annual basis and commitments to Member States must be spent within that year. The EAFRD operates on a multiannual basis, where unspent commitments in one year can be carried forward to later years within rules established in the CAP regulation.

EAGF expenditure that is recovered where the expenditure is not in conformity with Community legislation and no entitlement existed is paid back to the EAGF and becomes assigned revenue in the EU budget. In the case of the EAFRD, sums recovered or cancelled following irregularities remain available to the approved rural development programmes of the Member State concerned.

The absolute budget figure for the CAP more than doubled from 1990 to 2010 (partially related to additional Member States joining the European Union), but has remained relatively stable in absolute terms since then. At the same time, CAP expenditures as a share of the total EU budget declined sharply, from 65.5% in 1980 to 33.1% in 2021 (European Parliament, 2022[7]). The overall budget for the CAP during the years 2014-20 was EUR 408 billion (USD 465 billion), of which 76% was initially allocated to Pillar 1 and the remaining 24% to Pillar 2.

The budgetary mechanism is largely based on pre-allocated CAP amounts between Member States. The budgetary allocations are decided as part of the complex negotiation process of agreeing on the European Union’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), which is decided every seven years. Member States’ main focus during the MFF negotiation process is the net budgetary envelope. This process is characterised by the juste retour principle, where each Member State compares its financial contribution to the EU budget with the money that flows back into the country. EAGF (Pillar 1) direct payments are allocated to farmer beneficiaries on the basis of their eligible hectares, but the funds are not distributed in line with the shares in the EU-eligible area. The Member States’ shares originally reflected the relative amounts of coupled support that was received under the rules put in place after the MacSharry Reform, implicitly benefiting countries with higher levels of production intensity. Direct payment levels per hectare thus differed between Member States. These disparities were exacerbated with successive enlargements in the 2000s. Recent reforms achieved convergence and greater uniformity in payment levels between Member States, while the issue continues to be contentious in the European Union’s MFF negotiations.

The basis for distributing EAFRD (Pillar 2) funds among Member States also depends on history. There are striking differences in the relative importance of EAGF and EAFRD funds across Member States. The EAFRD has a wider range of objectives than the EAGF, including cohesion objectives, since it is part of the European Structural and Investment Funds, which seek to transfer funds to more disadvantaged EU regions. EAFRD spending is increasingly focused on environmental and climate expenditure, although modernisation expenditure remains a priority in the newer Member States. This raises the question of whether the current distribution of EAFRD funds across Member States and regions is well aligned with EU priorities. In its impact assessment for the 2013 CAP reform, the European Commission examined the implications of using different criteria for the distribution of EAFRD support (EC, 2011[8]). The analysis concluded that distribution based on objective criteria would allow for a better fit between the policy objectives and the resources made available, thus a better use of the EU budget, but pointed out that any such change would need to be phased in to avoid disruption and ensure a smooth transition.

3.2. Agricultural support policies

3.2.1. Level of support

OECD indicators of support estimate all monetary transfers associated with agricultural policy and is calculated for the European Union as a whole, not at Member State level. In addition to EU CAP expenditures, these estimates include national and regional expenditures both associated with the co-financing of CAP Pillar 2 measures and purely national measures such as research expenditure, state aid and tax rebates. They also include transfers from market price support (MPS)1 measures.

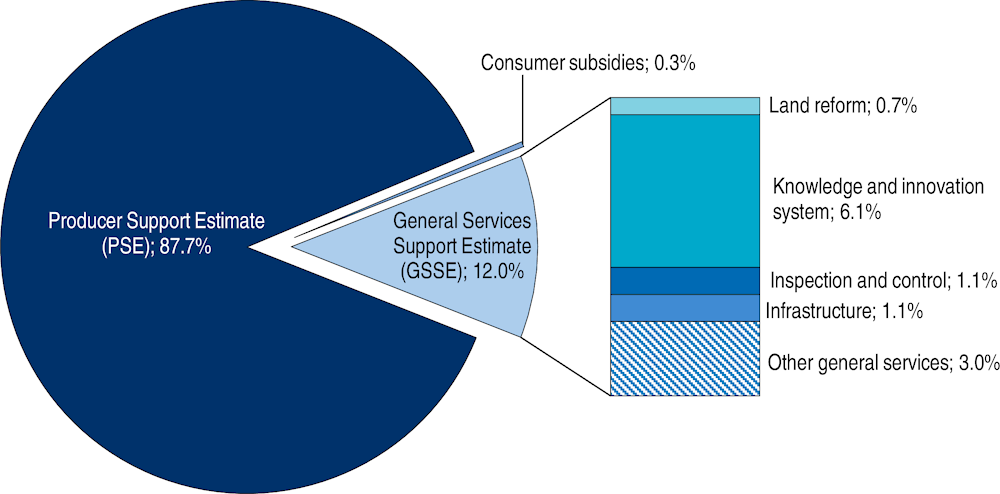

The broadest OECD indicator of support is the Total Support Estimate (TSE), which includes support to producers individually (PSE) or collectively (the General Services Support Estimate, GSSE) and direct budgetary transfers to consumers. As a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), it measures the total burden of agricultural support for the economy. The European Union’s TSE decreased from 2.5% of GDP in 1986-88 to 0.6% in 2019-21, a percentage point lower than the OECD average (OECD, 2022[9]). The vast majority of support (87.7% in 2019-21) is allocated to individual farmers and most of the remainder is designated for general services (GSSE) to the sector, which averaged 12% of total support – a decrease compared to 2000-02 and below the OECD average (Figure 3.1).

While the relative importance of the GSSE has slightly declined over the past two decades, the composition of GSSE expenditures has shifted. Expenditure on agricultural knowledge and innovation systems grew nine percentage points to 51% of total GSSE expenditures in 2019-21, equivalent to 6.1% of total support to agriculture. Expenditures on marketing and promotion also rose (now responsible for 25% of the GSSE), while support for the development and maintenance of infrastructure and public stockholding has remained static in absolute terms since 2000-02.

Figure 3.1. Composition of total support to agriculture in the European Union, 2019-21

Note: European Union refers to EU28 for 2019; EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020; and EU27 for 2021.

Source: OECD (2022[10]).

3.2.2. Changes in the composition of support

Overall, the changes in the composition of support to EU agriculture correspond to three principal axes of reform, discussed below: greater market orientation; greater integration of environmental and climate objectives; and a broader focus on structural policy and rural development. The first two axes are reflected in the evolution of the European Union’s PSE.

Greater market orientation

The original CAP heavily emphasised the role of price transfers (market price support) to achieve its policy objectives, particularly the objective of supporting farm income. In this, it reflected the national policies of the six original Member States that were in place prior to the creation of the CAP (Martiin, Pan-Montojo and Brassley, 2016[11]). However, the level of MPS for grains that emerged from the political negotiations around the launch of the CAP set the initial level at the upper end of the range. This early political decision resulted in producer prices in the early decades of the CAP that were two or even three times higher than world market prices. High internal EU market prices were maintained by variable import levies, intervention purchasing of domestic supplies when producer prices fell below the high guaranteed minimum levels, and variable export refunds that enabled the disposal of surpluses at world market prices and which became increasingly important as EU production exceeded levels of domestic consumption.

Pressures to reform this policy came from its budgetary cost and the increasing trade tensions – particularly with the United States – arising from subsidised EU exports. Attempts were made during the 1980s to control budgetary costs, notably through the introduction of a quota regime for milk production in 1984. However, the first real reform of the CAP (the MacSharry Reform) took place in 1992 during the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade Uruguay Round negotiations. This led to a lowering of the guaranteed intervention prices, which underpinned producer prices and introduced a system of coupled direct payments to compensate farmers for the anticipated loss in market income. This reform initiated a gradual movement toward greater market orientation with lower intervention support prices compensated by higher direct payments. This process was completed in 2012 following the Health Check Reform of 2009. Since then, intervention prices have been set at levels that provide a “safety net” in the case of a particularly severe drop in producer prices, but do not usually play a role in the formation of producer prices.

A further step towards greater market orientation was introduced with the Mid-Term Review/Fischler Reform in 2003, which decoupled direct payments from production. Farmers now were entitled to receive a lump-sum payment per hectare of eligible land regardless of the level of production on that land or, indeed, even whether the land was used for agricultural production at all (provided it was maintained in a state where it could be used for agricultural production).

Not all direct payments are decoupled. Member States are allowed to target aid to specific sectors facing difficulties, with a view to preventing the escalation of these difficulties that could lead to the abandonment of production. In the original Regulation (EU) 1307/2013, coupled support should only be granted to the extent necessary to create an incentive to maintain current production levels in the sectors or regions concerned. This restriction was removed in the Omnibus Regulation (EU) 2017/2393. Coupled support is still defined as a production-limiting scheme, but this only means that it should be based on either a fixed area or a fixed number of animals, not necessarily limited to the current production level. It must also respect financial ceilings intended to limit the extent of market distortion. The basic rule in the CAP 2014-22 is that coupled support should not exceed 8% of a Member State’s direct payments envelope, but this ceiling could be increased to 13% or even more with Commission approval, and by a further 2% to specifically support the production of protein crops. All EU Member States, except for Germany, decided to use voluntary coupled support during the 2014-22 programming period, with an annual monetary allocation of around EUR 4.2 billion per year. This represented 11.2% of the direct payments budget. The animal-based sectors have always been the largest beneficiaries of coupled payments: in 2022, 22 Member States decided to grant coupled support for beef and veal and 18 Member States to the milk and milk products sector (EC, 2022[12]).

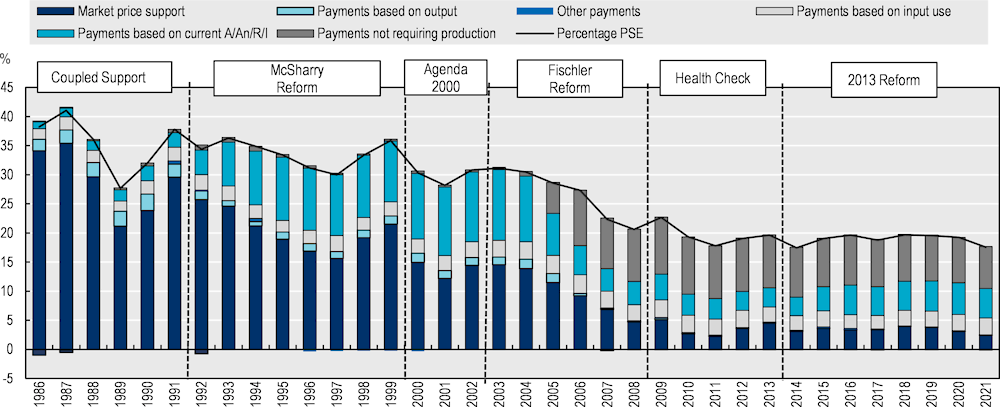

The various reform stages in the CAP are clearly visible in Figure 3.2, which shows the changing level and composition of producer support (as measured by the PSE) over time. While at the end of the 1980s most CAP expenditures financed MPS measures, in particular market interventions and export refunds, the share of those measures in total support decreased gradually as the share of direct payments increased. At the same time, these reforms have also affected the level of support. Overall, the %PSE, which relates support to producers to the value of gross farm receipts, significantly decreased over time, from 38.4% in 1986-88 to 18.8% in 2019-21. Despite these substantial reforms of support for the sector, potentially most-distorting forms of support still represent 23.1% of support (OECD, 2022[9]). Reducing the most distorting producer support measures would most likely contribute to achieving environmental policy objectives across a range of areas (Chapter 4), since often the most-distorting measures also correspond to the most environmentally harmful type of support from a nitrogen pollution perspective (Henderson and Lankoski, 2019[13]; DeBoe, 2020[14]), or for biodiversity (DeBoe, 2020[14]; Lankoski and Thiem, 2020[15]).

Figure 3.2. Level and PSE composition by support categories in the European Union, 1986 to 2021

Notes: PSE: Producer Support Estimate; A/An/R/I: Area planted/Animal numbers/Receipts/Income.

Payments not requiring production include payments based on non-current A/An/R/I (production not required) and payment based on non‑community criteria. Other payments include payments based on non-current A/An/R/I (production required) and miscellaneous payments. European Union refers to EU12 for 1986-94, EU15 for 1995-2003, EU25 for 2004-06, EU27 for 2007-13, EU28 for 2014-19, EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020, and EU27 for 2021.

Source: OECD (2022[10]).

In the mid-1980s, producer prices were maintained above world market levels by a combination of minimum intervention prices, import tariffs and export subsidies. The significance of MPS has been greatly reduced as successive CAP reforms moved agricultural policy in a more market-oriented direction, though its share has remained largely unchanged since 2010. The fall in MPS was originally compensated by coupled budget payments based on current area, animals, receipts or income (A/An/R/I) and then subsequently by decoupled payments not requiring production. However, in the recent CAP programming period, coupled payment support has again grown in importance. Payments based on input use represent only 16.5% of support, but its share has also grown over time.

From 1992, the share of MPS decreased and the share of payments based on current area and animal numbers increased following the implementation of the MacSharry Reform. This wide-ranging reform included reducing cereal intervention prices, introduced compensatory payments per hectare for cereals or per head for livestock as well as a mandatory set-aside scheme to take land out of production. In conjunction with the reform of budgetary support measures through the MacSharry package, MPS also declined thanks to EU commitments under the 1994 Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture. Namely, bound tariffs were gradually reduced and other border measures were implemented (including replacing variable import levies with ad valorem or specific tariffs and tariff rate quotas) (OECD, 2011[2]).

These movements were reinforced with the implementation of Agenda 2000, but the second substantial change to PSE composition began in the mid-2000s after the Fischler Reform decoupled most payments to farmers from production: MPS continued to decrease while a large share of payments lost their link with current factors of production and did not require any production to be granted. No further market orientation reforms have taken place in the last decade since the Health Check, in the 2013 reform or the CAP 2023-27.

Measures that support commodity markets represented 4.7% of the overall agriculture and rural development budget in 2021, but 26.6% of support. Prices paid to EU domestic producers averaged 4% above world market prices in 2019-21. The possibility for public intervention for cereals (namely common and durum wheat, barley, and maize), dairy and other products still exist. However, the last intake of cereals into public storage occurred during the 2009/10 marketing year (EC, 2013[16]) (EC, 2022[17]), the European Union may provide support to operators of private storage of products, such as olive oil, white sugar and more recently also pig meat (EC, 2022[18]).

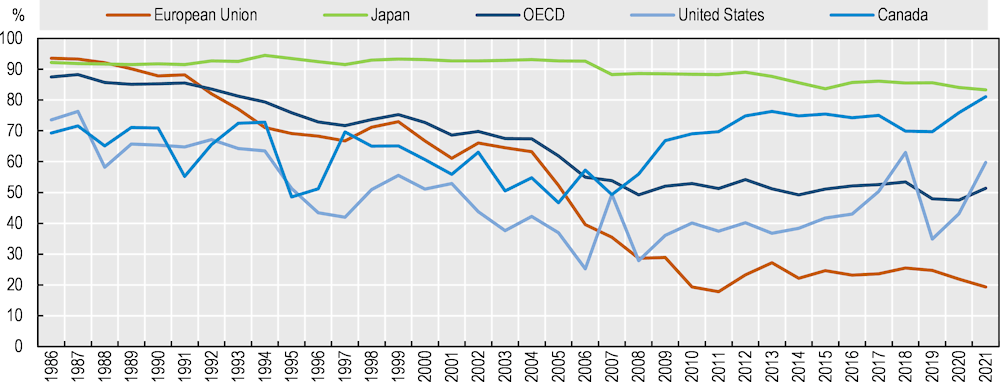

The Single Commodity Transfer is the OECD indicator used to capture product-specific support. Its evolution shows that successive CAP reforms have reduced the link between payment entitlements and commodity production (Figure 3.3) and data confirm that the 1992 MacSharry Reform can be considered the turning point. Since the early 1990s, support started to be less linked to domestic prices or animal numbers. Another important step was the introduction of the single (decoupled) payment scheme (from 2005 or 2006, depending on the country). The Single Commodity Transfer of the European Union accounted for only 21% of the total PSE in 2019-21, which is well below the OECD average (49%) and the US average (46%), and considerably lower than the averages of Canada and Japan.

Figure 3.3. Single commodity transfers in selected economies, 1986 to 2021

Notes: European Union refers to EU12 for 1986-88; EU15 for 2000-02; EU28 for 2019; EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020; and EU27 for 2021. The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States. Due to data availability, Chile only included from 1990, Colombia and Slovenia from 1992, Costa Rica and Israel from 1995, Luxembourg from 2001, and Latvia and Lithuania from 2004.

Source: OECD (2022[10]).

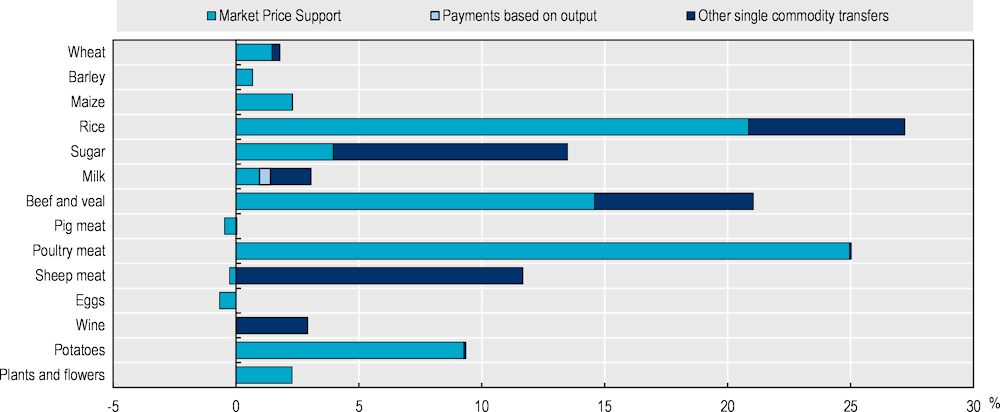

Over time, CAP payments have also become less commodity specific. Only a few commodities are characterised by non-zero transfers and for most of them, MPS is the dominant component of their single commodity transfers (Figure 3.4). Among them, the per cent of budgetary support on farm receipts is higher than the per cent of MPS only for sugar, milk, sheep meat and wine.

Figure 3.4. Commodity-specific transfers in the European Union, 2019‑21

Notes: EU28 for 2019; EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020; EU27 for 2021. Only commodities with non-zero transfers are presented.

Source: OECD (2022[10]).

Greater integration of environmental and climate objectives

During the 1980s, policy increasingly focused on the environmental impact of agriculture, both to avoid damaging negative impacts on the environment and to promote and support agricultural practices that had a positive environmental impact. The Single European Act 1987 made the environment a shared Union competence for the first time, and the Commission published its first Communication on the Environment and Agriculture in 1988 that put an emphasis particularly on the problems caused by large-scale intensive livestock rearing and intensive crop production in zones at risk of pollution of surface and ground waters by nitrates.

Agricultural pollution issues were addressed mainly by regulation. Again, the 1992 MacSharry Reform can be considered an important turning point, since the agri-environmental Regulation (ECC) No. 2078/92 that was introduced as part of the accompanying measures of this reform was more oriented towards a model of paying farmers to provide desired environmental outcomes. This regulation differed from earlier measures since it made it mandatory for all Member States to implement an agri environmental programme. It also included a wider range of measures and, above all, provided for co-financing of agri-environmental schemes from the guidance section of the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund, thus setting the agri-environmental measures on an equal footing with the CAP’s commodity programmes (Latacz-Lohmann and Hodge, 2003[19]).

The Fischler 2003 CAP Reform introduced mandatory environmental cross-compliance for those receiving CAP payments. Climate action has been an explicit objective of the CAP since the 2007-13 programming period. The CAP 2014-20 saw the introduction of a greening payment in Pillar 1, requiring farmers to follow three specific practices seen as beneficial for climate and the environment (Matthews, 2013[20]). EU Member States had to allocate 30% of their income support to this green payment. The CAP 2023-27 introduces a new delivery model with a performance and results based approach, as well as new instruments (e.g. the eco-schemes) to incentivise the adoption of specific farming practices with higher environmental benefits. See Chapter 4 for a more comprehensive analysis of the EU agri-environmental regulations and policy.

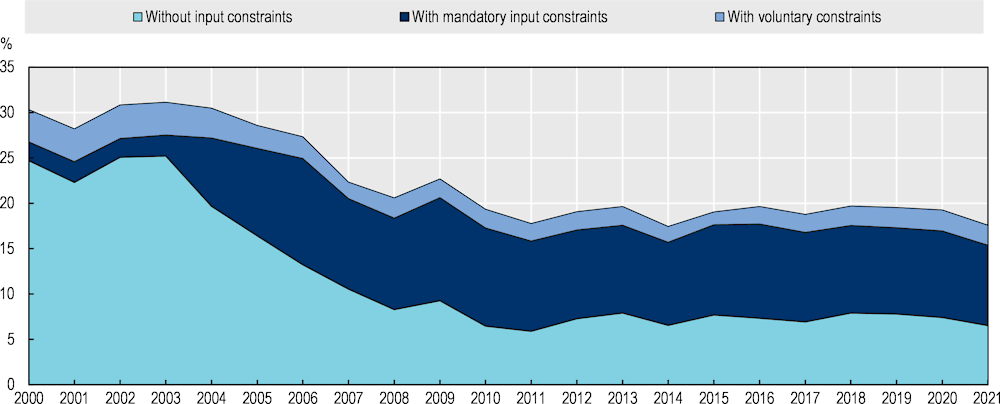

The increasing integration of environmental and climate objectives in the CAP is reflected in the increasing scope of input constraints that are attached to payments (Figure 3.5). The share of support with mandatory input constraints becomes significant with the introduction and generalisation of cross-compliance to all CAP payments after the 2003 reform, while the developments in payments with voluntary input constraints are linked to Pillar 2 and, in particular, to the agri-environmental payments that are granted on the condition that farmers change their farming practices (usually to adopt more extensive ones).

Figure 3.5. Payments conditional on the adoption of specific production practices in the European Union, 2000 to 2021

Notes: While the “with mandatory input constraints” label may generally be considered to refer to environmental cross-compliance requirements, programme descriptions often do not provide specifics on what those mandatory input constraints entail. They may or may not be related to environmental externalities or public goods. Similarly, the label “with voluntary input constraints” may describe programmes with input constraints not obviously associated with externalities or public goods.

Source: OECD (2022[10]).

Broader focus on structural policy and rural development

The modernisation of agricultural structures had been seen as a necessary complement to the market policy of the CAP. It led to the introduction of a socio-structural policy in the early 1970s, followed by various integrated development programmes, particularly for Mediterranean countries. Furthermore, a scheme of payments to farmers in less favoured areas was introduced following the United Kingdom’s accession to the European Union in 1975. These early structural policy interventions later broadened into a wider rural development policy following the publication of a Commission Communication on the Future of Rural Society in 1988 (EC, 1990[21]).

Since the 1990s, there has been increasing acknowledgement of the fact that EU agriculture is embedded in the wider fabric of rural communities with mutual synergies between them, recognising that agricultural production is no longer the main economic activity in many rural areas. Rural areas vary greatly in economic and demographic terms, and their challenges are extremely diverse. Various rural development initiatives were included in the newly created Structural Funds during the 1990s. As discussed in Chapter 2, other EU structural and investment funds, such as the European Regional Development Fund and the European Social Fund, also provide support to rural areas, while national policies relating to regional development, urban and spatial planning, and the provision of infrastructure and public services, are the dominant policy influence on rural development trends.

The importance of rural areas was fully recognised in the context of the Agenda 2000 Reform, when rural development policy was made an integral part of the CAP by designating the set of measures subsumed under this term the “second pillar”. The main innovation in the policy was that measures had to be included in a Rural Development Plan, which followed programming methods previously known from the Structural Funds programmes. Member States could choose from a set of measures set out in the governing Regulation (EC) No. 1750/1999, which included, inter alia, a scheme of investment aids, aid for young farmers, support for vocational training, an early retirement scheme, support for farms in less favoured areas, compensation for agri-environment measures, support for the processing and marketing of agricultural products, and forestry. These measures were co-financed by the CAP and by Member States, in contrast to direct payments, which were fully financed from the CAP budget. Member States were given some flexibility to transfer resources between the pillars within limits set down in the CAP legislation. Most of these funds are allocated to farmer beneficiaries, with only a very small share allocated to other rural enterprises and organisations (ADE, 2020[22]).

3.3. Agricultural trade policies

3.3.1. Despite the reduction of market price support, tariffs on agriculture double the average and negatively impact trade

Up to the mid-2000s, MPS generated by trade and other market measures was the main component or producer support in the European Union (Figure 3.2). This changed after the Fischler Reform, and since then, decisions regarding agricultural trade policies have been mostly separated from those concerning domestic policies. Decisions on overall import protection, including the European Union Common External Tariff, the opening of tariff rate quotas (TRQs), and the conclusion of multilateral and bilateral trade agreements, are mainly under the purview of the Common Commercial Policy. Nevertheless, trade policy, as reflected in the European Union’s market price support, has consequences for the productivity, sustainability and resilience of the EU’s agricultural sector.

The European Union extensively applies TRQs in agricultural trade. The Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture established TRQs to maintain market access conditions and create minimum access for products with very high bound tariffs. There are also TRQs with specific regional trade agreements. Overall, more than 15% of EU agricultural tariff lines are covered by a TRQ, and more than 20% of agricultural imports enter the European Union under a TRQ regime (Matthews, Salvatici and Scoppola, 2017[23]).

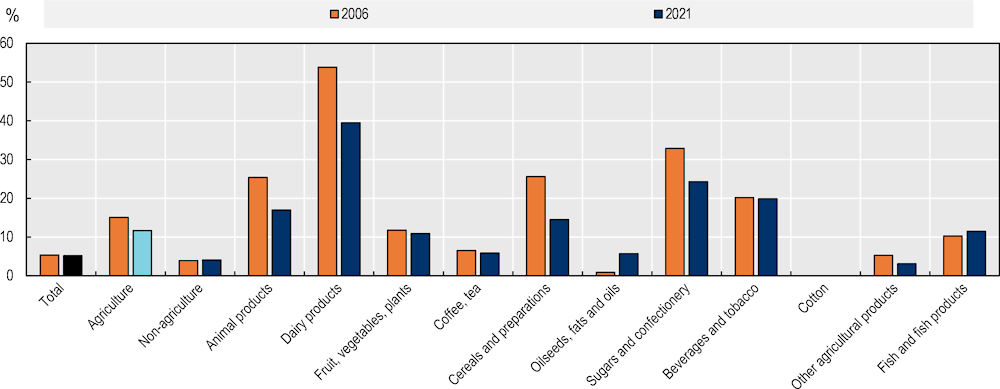

The European Union is the world’s largest agricultural importer and tariffs are still significant in this sector: the simple average most-favoured nations-applied tariff rate for agricultural products was 11.7% in 2021, down from 15.1% in 2006, showing a slow but steady decreasing trend in the last decade and a half (WTO, 2022[24]). This applied tariff rate for agricultural products remains nearly three times the average applied tariff rate for non-agricultural products, calculated at 4.1% for 2021, slightly higher than 15 years ago (3.9%). They are also higher than in other OECD countries such as the United States (5.2%) and Australia (1.2%). The products with the highest most-favoured nation-applied tariffs are sugars and meat preparations, while lower tariffs are in place for products not produced in the European Union (e.g. coffee and tea) as well as for cereals and meats (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6. Applied most-favoured nations tariffs in the European Union by product groups, 2006 and 2021

Preferential access for developing countries has only a limited impact

The European Union maintains preferential tariffs for imports from certain countries pursuant to its reciprocal and non-reciprocal preferential agreements. It is the largest trading partner for many of the world’s developing countries, and trade preferences make up one of the central policies for improving integration between the European Union and these countries.

The European Union grants unilateral trade preferences to developing countries through the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP), which has been in force since 1971. The GSP seeks to create economic opportunities in developing countries and promote sustainable development. It consists of three non‑reciprocal arrangements.

The standard GSP, which offers access to the EU market at zero or reduced tariffs on two-thirds of the EU tariff lines – currently benefiting 15 countries.

GSP+, which reduces to zero the tariffs on the goods covered by the standard GSP if the beneficiary country has ratified and implemented 27 major international conventions and meets certain criteria related to the share and diversification of its exports to the European Union – currently benefiting nine countries.

Everything but Arms (EBA), which provides access free of tariffs and quotas to all products except arms and ammunition from 48 least developed countries (LDCs) (EC, 2021[26]).

As of 2019, total EU imports under the GSP amounted to EUR 62 billion, or 39% of all imports from GSP beneficiary countries. In the case of the LDCs, imports under the EBA were EUR 25 billion, or 67% of EU imports from the LDCs. Agri-food products represent only a small share of the European Union’s imports from the LDCs: in 2020, only 12% of total imports from these countries were from the agri-food sector (including fisheries), while 57% of imports were of textiles. The GSP utilisation rates2 for LDC agri-food imports ranged between 74% for vegetable products and 95% for fats and oils (UNCTAD, 2022[27]).

EU assessments have found that the GSP has made a modest contribution to export diversification in developing countries, which partly relates to its concentration in a limited number of beneficiaries: in 2019, five developing countries (Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Viet Nam) accounted for 80% of total EU GSP imports (EC, 2021[26]). The current EU GSP regulation will expire at the end of 2023, and the system is currently undergoing a revision that seeks to address this and other identified problems and better exploit the GSP’s potential to promote sustainable development.

The proposed new GSP regulation for 2024-34 would keep the current structure of three arrangements. The modifications include adjustments of import criteria to guarantee that the system has more space for poorer developing countries relative to large, industrialised beneficiaries and that countries graduating from LDC status have a smoother transition from the EBA to the GSP+. It also enlarges the list of international conventions that must be implemented in order to benefit from GSP+ preferences to include the Paris Agreement on Climate Change (among others) and introduces an urgent procedure to withdraw preferences when a beneficiary country is found in violation of international standards (EC, 2021[28]).

A recent assessment of the impact of EU tariffs on imports to the European Union in the agricultural sector (Cipollina and Salvatici, 2020[29]) found that, on average, these tariffs have lowered agricultural imports by 14% and that the protectionist impact is larger than the trade creation due to preferential treatment, since the various agreements have increased extra-EU imports by about 10%.

The European Union applies numerous non-tariff measures, such as sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to trade, on agri-food products. As of 2016, only 0.5% of food products, 1% of vegetable products and 4% of animal products were not subject to non-tariff measures (WITS, 2018[30]). Non-tariff measures applied by the European Union include requirements on food production and safety, animal and plant health, animal welfare, alien organisms, and gene technology. A 2014 study found that the sanitary and phytosanitary measures applied by the European Union present an important burden for low-income countries, leading to a 14% reduction in their exports (Murina and Nicita, 2014[31]).

3.3.2. The EGD has significant trade implications, and the European Commission intends to use external policy to globally promote higher sustainability standards

One of the objectives of the European Green Deal is to build a more sustainable and healthier food system. Implementing the necessary measures to achieve this objective will have a significant impact on the competitiveness of EU producers as well as on international trade in food, most likely reducing EU production (Petsakos et al., 2022[32]; Beckman et al., 2020[33]; Henning and Witzke, 2021[34]). The European Union has acknowledged that this transformation includes an important external policy dimension to also support the global transition to sustainable agri-food systems (EC, 2019[35]). The Green Deal Communication included an agenda of actions covering diplomacy, trade policy, development support and other external policies to make the European Union an effective advocate focused on convincing and supporting others to take on their share of promoting more sustainable development. It proposed to use its economic weight to shape international standards in line with EU environmental and climate ambitions.

The European Union has identified a particular need to take greater account of sustainability issues in trade policy and to bring about greater coherence between its own agricultural policy, trade policy and Green Deal policies. The Commission’s Trade Policy Strategy emphasised the need to make supply chains more sustainable, in particular, by promoting sustainability standards across global value chains (EC, 2021[36]). Several initiatives were highlighted, including improvements in the multilateral trade framework; promoting the sustainability dimension in the European Union’s trade and investment agreements; the introduction of autonomous measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and requiring imports to comply with EU production requirements in line with WTO rules; the introduction of legislation addressing deforestation and forest degradation; and sustainable corporate governance, including mandatory environmental, human and labour rights due diligence. The Farm to Fork (F2F) Strategy (EC, 2020[37]) further underlines the importance of these initiatives.

The objectives of these upcoming trade policies are to avoid that EU consumers offshore the negative environmental consequences of their consumption through existing or increased imports and to ensure that EU producers compete with imports on a level playing field. Direct policies like regulations are likely to generate “pollution leakages” (Gruère et al., 2023[38]). These policies aim to raise global sustainability standards by leveraging access to the EU market to provide a stimulus to exporting countries to raise their standards. Its implications for market access are likely to be controversial.

The European Union has recognised the importance of multilateral initiatives to promote international standards in relevant international bodies and to encourage the production of agri-food products complying with high safety and sustainability standards. It has committed to supporting small‑scale farmers in meeting these standards and accessing markets through its development co‑operation policy. The F2F Strategy proposed to pursue the development of green alliances on sustainable food systems with all its partners in bilateral, regional and multilateral fora. One example is the Alliance on Sustainable Cocoa announced in June 2022 between the European Union, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana and the cocoa sector, which, among other objectives, will help producing countries and the cocoa sector prepare for the implementation of EU legislation on deforestation and corporate sustainability due diligence.

Sustainability is now part of all EU Free Trade Agreements, with an expanding scope of provisions and of upcoming mandatory due diligence regulations

Sustainability as an objective of EU trade policy has also been reflected in a specific chapter on trade and sustainable development in all the European Union’s bilateral free trade agreements since the EU-Korea Free Trade Agreement in 2011. The Commission has recently proposed enhancing the contribution of EU trade agreements to promoting the protection of the environment and labour rights worldwide (EC, 2022[39]). Additional potential commitments include a chapter on sustainable food systems, respect of the Paris Agreement and Nationally Determined Contributions, and a more active role of the chief trade enforcement officer in implementing the sustainability dimension of existing agreements. The revision of the GSP currently underway could also be used to promote greater respect for the environment as well as core human and labour rights.

In line with the objective to make global supply chains more sustainable, two legislative initiatives extend the scope of mandatory due diligence obligations for companies. Political agreement on a regulation to prevent trade in commodities and products associated with deforestation and forest degradation was reached in December 2022 between the Council and European Parliament. The regulation will require operators that place specific commodities on the EU market that are associated with deforestation and forest degradation – soy, beef, palm oil, timber, rubber, cocoa and coffee and some derived products such as leather, chocolate, and furniture – to ensure that only deforestation-free and legal products (according to the laws of the country of origin) are allowed on the EU market. Operators will be required to keep strict traceability to ensure that only deforestation-free products enter the EU market – and that enforcement authorities in Member States have the necessary means to control that this is the case. Although the regulation is seen as mainly preventing the import of agri-food and timber products at risk of contributing to deforestation, it will apply to both domestic and imported products, so they are measured by the same standards.

The Commission also published a proposal for a Directive on Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence on 23 February 2022, which will require Member States to adopt national legislation obliging larger companies to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence. Such companies will be required to identify actual or potential adverse impacts, prevent and mitigate these impacts, and bring these impacts to an end. To ensure compliance, companies would be liable for damages if they fail to comply with their respective obligations. A further Commission proposal in September 2022 would prohibit all products made with forced labour on the EU market.

The application of EU health and environmental standards for imported agricultural products is on the agenda and faces opposition from trading partners

Of particular importance for the agri-food aspects of the Green Deal is the commitment by the European Council, Parliament and the Commission as part of the 2021 CAP political agreement to require that imported agricultural products comply with certain production requirements to ensure the effectiveness of the health, animal welfare and environmental standards that apply to agricultural products in the European Union and to contribute to the full delivery of the European Green Deal and F2F Strategy (European Parliament, 2021[40]).3 In its communication on the Future of Food and Farming in 2017, the European Commission (2017[41]) acknowledged that in “the Union's highly diversified farming and climatic environment, neither top-down nor one-size-fits-all approaches are suitable to delivering the desired results and EU added value”.

In June 2022, the Commission published a report entitled Application of EU Health and Environmental Standards to Imported Agricultural and Agri-food Products (EC, 2022[42]). The report was informed by a public consultation, to which stakeholders from 30 countries, 17 of which were non-EU Member States, submitted their comments; the orientation debate in the Agriculture and Fisheries Council in February 2022; and the Resolution of the European Parliament on the F2F Strategy (European Parliament, 2021[43]). The report concluded that there is some scope to extend EU production standards to imported products, provided this is done in full respect of the relevant WTO rules. The report showed that before applying production standards to imports, it is always essential to make a case-by-case assessment. This report, in addition to assessing the legal and technical feasibility of doing this, and explaining the constraints that apply, also indicated a wide range of areas where the European Union has already extended its domestic production standards to imported products, be it via multilateral, bilateral or autonomous instruments. The prohibition on the import of beef produced with growth hormones is an early example of the application of reciprocity measures to imported agricultural products and, more recently, the European Union has extended its domestic regulation on veterinary medicinal products4 to the import of animals and products derived from animals where antimicrobial drugs were used for growth promotion, or antimicrobials reserved for human health were administered.

There have been debates about the application of EU health and environmental standards for imported agricultural products, particularly when EU farmers no longer have access to active substances for use as pesticides or herbicides, even if in the past there have been some derogations for some Member States. Imports produced with the aid of these substances compete with EU producers. In the F2F Strategy, the Commission stated that it would, in compliance with WTO rules and following a risk assessment, take into account environmental aspects when assessing requests for import tolerances for pesticide substances no longer approved in the European Union. In the first implementation of this principle, the Commission proposed to lower all the current maximum residue limits for two neonicotinoid insecticides, clothianidin and thiamethoxam, to the limit of determination. There has been significant opposition to this unilateral adoption of environmental criteria when setting maximum residue limits from the European Union’s trading partners.5

3.4. CAP 2014-22: Overview of selected tools to achieve PSR objectives

In many ways, the CAP 2014-22 – which includes the 2014-20 Reform and the 2021‑22 transitional rules (Table 3.1) – can be characterised as a continuation of the CAP 2007-13, since the overall funding was almost constant and the two-pillar structure maintained (OECD, 2017[6]). The three main novel features of the CAP 2014-22 can be synthesised in the following (European Parliament, 2021[5]).

Converting decoupled aid into a multifunctional support system with aid directed toward specific objectives. Accordingly, the single payment scheme was replaced by a system of decoupled payments with seven components: 1) a basic payment; 2) a greening payment for environmental public goods; 3) an additional payment for young farmers; 4) a “redistributive” payment for first hectares of farmland; 5) support for areas with specific natural constraints; 6) aid coupled to production; and 7) a simplified system for small farmers. These options also applied in countries implementing the Single Area Payment Scheme.

Consolidating Common Market Organisation tools into safety nets in case of market disruption or price crisis, and ending other supply control measures, namely the milk and sugar production quotas in 2015 and 2017, respectively.

A more integrated, targeted and territorial approach to rural development, including simplifying the range of available instruments to focus on six priority areas: 1) fostering knowledge transfer and innovation; 2) enhancing the competitiveness of all types of agriculture and the sustainable management of forests; 3) promoting food chain organisation, including processing and marketing, and risk management; 4) restoring, preserving and enhancing ecosystems; 5) promoting resource efficiency and the transition to a low-carbon economy; and 6) promoting social inclusion, poverty reduction and economic development in rural areas.

For the 2014-20 period, agricultural expenditure totalled EUR 408.3 billion: EUR 291.3 billion for direct payments (71.3% of the CAP total), EUR 99.6 billion for rural development (24.4%) and EUR 17.5 billion for market measures (Common Market Organisation) (4.3% of the total) (European Parliament, 2022[7]). Table 3.2 shows the distribution of the different types of expenditure by scheme (direct payments and market expenditure), and for priority areas (rural development expenditure).

Table 3.2. Distribution of CAP expenditures, 2015-20

|

Direct payments |

Rural development |

Market expenditure |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scheme |

% |

Priority area |

% |

Scheme |

% |

|

Basic payment scheme |

40.0 |

Ecosystems |

48.0 |

Wine |

37.9 |

|

Greening |

29.1 |

Competitiveness |

23.4 |

Fruit and vegetable |

34.3 |

|

Single area payment scheme |

11.8 |

Social inclusion |

13.5 |

POSEI2 |

8.6 |

|

Voluntary coupled support |

10.8 |

Food chain organisations |

10.3 |

School schemes |

6.1 |

|

Redistributive payment |

4.3 |

Resource efficiency |

4.9 |

Promotion activities |

4.6 |

|

Other |

4.0 |

Knowledge and innovation1 |

– |

Other |

8.5 |

1. No financial allocation is shown for Priority 1 as the expenditure is distributed across other focus areas.

2. The programme of options specifically relating to remoteness and insularity (POSEI) supports the European Union’s outermost regions, which face specific challenges due to remoteness, insularity, small size, difficult topography or climate. It also supports those that are economically dependent on only a few products.

Source: EC (2022[44]).

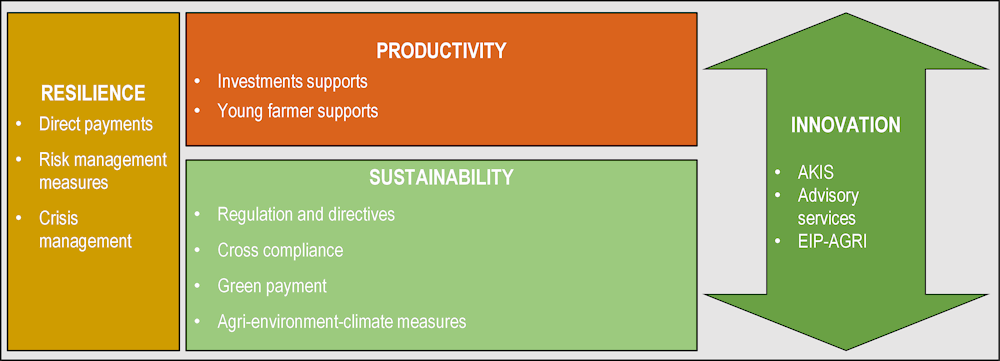

Figure 3.7 shows the selected policy instruments that are analysed in greater detail in this study amongst the broad portfolio of tools available in the CAP 2014-22, categorised according to the PSR objectives of productivity, sustainability and resilience and the overarching innovation driver. The next subsection reviews agricultural policy tools for productivity and resilience. Measures to promote sustainability and innovation are analysed in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively.

Figure 3.7. The main CAP instruments categorised according to the PSR objectives

Notes: AKIS: Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation System; EIP-AGRI: European Innovation Partnership for Agricultural Productivity and Sustainability. The categorisation was made considering the main objective of each instrument, although some instruments may also have effects on different categories (e.g. AKIS design, advisory service, investment supports, generational renewal; the EIP-AGRI may have effects on productivity and sustainability).

3.4.1. Direct payments

Direct payments make an important contribution to farm income, but their distribution is uneven and is not based on farm households’ disposable income and living standards

Originally, direct payments were introduced to compensate farmers for income losses arising from the reduction in high market support prices (with the implication that they would be transitional or temporary payments). As decoupled payments became a permanent feature of the CAP, various justifications have been advanced: to increase farm income, stabilise farm income, compensate farmers for higher regulatory standards compared to overseas competitors, compensate farmers for the delivery of public goods and ecosystem services, or ensure food security. Certainly, direct payments make an important contribution to farm income, representing 24% of agricultural income in 2015-20 and 12.2% of gross farm receipts in 2021 (OECD, 2022[9]). These percentages are higher for specific sub-sectors (e.g. beef farming) and can be higher or lower for individual countries, even if these cross-country variations cannot be analysed by the PSE database in its current form.6

The distribution of Pillar 1 aid is uneven, since the distribution of direct payments follows the distribution of land use in the European Union, which is highly skewed. Despite all the corrective measures introduced, in 2015, 20% of farms received 80% of this aid (EC, 2022[45]). Moreover, it has been found that land concentration is correlated with the level of direct payments concentration (Severini and Tantari, 2014[46]) and that a high share of direct payments goes to larger farms, where the need for income support is not obvious (Guth et al., 2020[47]; Matthews, 2016[48]; 2017[49]; Ciliberti et al., 2022[50]). Modalities envisaged so far to address this problem, such as higher payments to the first hectares or degressivity above certain thresholds, have witnessed limited take-up by Member States (OECD, 2020[51]).

While some evidence exists on the association between the CAP and the reduction of poverty at the sub-national level (World Bank Group, 2018[52]), there is not enough information or analysis of the impact of direct payments on improving income distribution among farm households, or its role in alleviating low levels of income among farmers. Indeed, direct payments are not targeted to low-income producers. A flat-rate payment per hectare inevitably benefits larger farms whose incomes are often well above the average non-farm income in the relevant country. Some steps to limit payments to very large holdings and to focus payments more on smaller farms have been taken, but their impact on the distribution of payments between farms has been limited to date. Furthermore, it is not farm income but household income that matters for policies that target equity. The untargeted nature of the income support granted by direct payments underlines the potential to make more effective use of these funds (Matthews, 2016[48]) (Marino, Rocchi and Severini, 2023[53]).

Direct payments are no longer the most efficient instrument for achieving resilience objectives

Several studies have found that direct payments stabilise farm income because their coefficient of variation is smaller than market income and smaller than farm income as a whole (Severini, Tantari and Di Tommaso, 2016[54]; Knapp and Loughrey, 2017[55]). To the extent that direct payments improve either the level or stability of farm income, they may contribute to absorption resilience capacity. The extent to which they contribute to adaptation and transformation resilience capacities is more doubtful (Sauer and Antón, 2023[56]). Direct payments may even have negative consequences on the resilience of some farming systems, especially on adaptability and transformability capacities (Buitenhuis et al., 2020[57]), by negatively affecting farm efficiency, total agricultural production and salaried employment (Žičkienė et al., 2022[58]).

However, direct payments are neither the most efficient nor the most equitable instrument to achieve resilience objectives (Matthews, 2016[48]; Matthews, 2017[49]). Leakages to unintended beneficiaries reduce the value of this support to farmers (OECD, 2003[59]; Ciliberti et al., 2022[50]). Direct payments have a short-run effect in raising farmers’ income, but ultimately, the effect of the transfer is to maintain a higher number of people working in agriculture than would otherwise be the case. In the longer run, the effect of the transfer is to slow down the structural transformation of agriculture rather than improve individual farm incomes that mainly respond to productivity trends (Matthews, 2017[49]).

The effectiveness of direct payments in stabilising farm income relative to other risk management instruments can also be questioned. They are not designed to deal with variations in income over time. Payments are made to farmers when prices are low, but when prices are high as well. Simulation analyses undertaken by the OECD found that highly decoupled payments (such as the EU single farm payment/basic farm payment) have very limited crowding-out effects on other risk management strategies, but also have a very limited effect in reducing income variability (OECD, 2011[60]). They are also not necessarily targeted to those farms and farm systems that experience the greatest income variability (Severini, Tantari and Di Tommaso, 2016[54]). To the extent that direct payments do contribute to stabilising farm income, this resilience stabilisation function could also be provided using more targeted payments (Matthews, 2017[49]).

Effects of CAP payments on agricultural employment are uncertain

The literature does not agree on the impact of CAP payments (decoupled, coupled and rural development payments) on agricultural employment. Some studies find a positive impact (though varying by type of payment), while others find a negative impact (for reviews, see Bojnec and Fertő (2022[61]) and Schuh et al. (2022[62]). However, the studies generally agree that the effects are small. One of the more recent studies that addresses some methodological deficiencies of previous studies found that CAP subsidies reduce the outflow of labour from agriculture, but the effect is almost entirely due to decoupled Pillar 1 payments (Garrone et al., 2019[63]). These authors estimated that the budgetary costs of preserving jobs in agriculture are high, putting the estimated cost at more than EUR 300 000 per year per job saved in agriculture. If the policy objective is to create jobs and maintain employment in rural areas, it would seem preferable to use a policy instrument directly aimed at preserving agricultural employment. Helming and Tabeau (2018[64]) simulated the impact of transferring 20% of the 2020 reference scenario Pillar 1 budget per Member State to finance a subsidy on agricultural labour use (independent of the type of labour – family labour, hired labour or contract work). They concluded that the social cost would be about EUR 1 400 per full-time work equivalent in agriculture (their model assumes full employment, the cost would be lower if unemployed labour exists). The lower cost per job maintained may reflect the more targeted nature of a labour subsidy rather than subsidies linked to land, production or investment.

CAP payments can be capitalised in land rents and can also deter generational renewal

In some cases, the benefits of CAP direct payments do not remain with the farmer beneficiary but leak out to benefit other stakeholders. This is particularly likely where the decoupled area-based or coupled payments are capitalised into the value of land and especially land rents, or where payments encourage additional production that decreases agricultural prices, which benefits consumers. Empirical studies agree that capitalisation takes place, although they disagree on the scale of the phenomenon (Baldoni and Ciaian, 2021[65]; Varacca et al., 2022[66]).

Higher land prices and rents can make entry for younger farmers more difficult and thus slow the rate of generational renewal. However, a more important impact may be to delay the exit of older farmers who would otherwise lose their direct payment if they handed over the farm (Schuh et al., 2022[62]). Some Member States required (Austria, Germany, Poland) or still require (France) to cease farming if they wish to receive the state pension (or at least the non-contributory part), which can encourage the transfer of land to the next generation where the state pension is attractive. But in many Member States, the state pension is low. Farmers would suffer an income loss if they ceased farming and lost their entitlement to direct payments, so extending this national legislation may have a limited effect. It may also run into constitutional objections, as was the case in Germany in 2018. However, the effect of CAP payments being used as a social payment to elderly farmers would be to slow down generational renewal.

3.4.2. Other measures to promote resilience

Risk management measures are underused

The European Union has progressively introduced subsidised agricultural risk management measures. Progressive liberalisation of the CAP, via the reduction of price support measures, increased EU farmers’ exposure to market volatility. This led to greater interest in the development of risk management measures, particularly insurance and mutual fund schemes. EU schemes were originally designed with the strict conditions set out in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture to be classified as “green box” payments. These conditions have been gradually relaxed over time to encourage greater uptake. The Commission’s conditions for a national government to subsidise risk management instruments have also been relaxed.

The EU framework to support risk management includes both CAP instruments and state aid rules (Bardají et al., 2016[67]). The first step was taken in 2007 with the reform of sectoral regulations for fruit and vegetables, as well as the wine sector, which allowed introducing prevention and crisis management mechanisms, including support to crop insurance or setting up mutual funds. In the 2014-22 programming period, a risk management toolkit was included in the menu of rural development programmes financed by Pillar 2. Support could be given through financial contributions to insurance premiums; mutual funds compensating production losses due to climatic, sanitary and environmental risks, or an income stabilisation tool which de facto operates as a mutual fund compensating income losses due to production and/or price risks. Additionally, Member States provide ex post natural disaster aid under state aid provisions. It is not clear the extent to which these programmes compete with each other and overlook the recommendation that government support for risk management is best concentrated on addressing market failures, with subsidies limited to covering programme administrative costs and, at most, losses from catastrophic risks (Glauber et al., 2021[68]).

Giving Member States the option to fund insurance schemes and mutual funds in rural development programmes (RDPs) and state aids means that there is no harmonised EU-wide agricultural risk management scheme. While the use of funded risk management presents intra-EU challenges and could have other unintended consequences depending upon programme design, its use remains limited due, at least in part, to the effect of direct payments. Farmers’ access to these instruments varies widely across Member States. Finally, evidence suggests that the expectation of free assistance is important for decisions about risk management measures: if producers believe that the government will bail them out in the event of a disaster, they may be willing to forego participation in existing insurance programmes or to engage in other risk-reducing and managing practices (Glauber et al., 2021[68]; Deryugina and Kirwan, 2017[69]).

There is also a risk that public subsidy of risk management instruments could discourage farmers from adapting to new climate conditions and from increasing self-reliance and preparedness (OECD, 2019[70]). Still, less than 2% of RDP funds were programmed for risk management in RDPs in the 2014-22 period. More generally, the EU risk management toolkit has remained largely underused (Cordier and Santeramo, 2020[71]). Even if improvements are made to increase the availability of risk management options for farmers, there may be limited interest among farmers, given the important role of direct payments in stabilising farm incomes. Additionally, excessive governmental support might crowd out private and market-based risk management solutions by overcompensating for normal business risks and incentivising risky and unsustainable farming practices (OECD, 2019[70]).

Crisis management

The CAP includes several measures that can be activated in the context of market and economic crises. While there is no definition of what such crises are, and therefore no clear threshold exists, the scope of these measures has grown since 2013. In particular, the traditional instruments of public intervention and support for private storage were augmented by provisions for exceptional measures in the event of a market disturbance in Articles 219-222 of Regulation (EU) No. 1308/2013 for all products. These articles provide considerable discretion to the European Commission to handle market crises, including the use of voluntary supply controls and financial support packages. In addition, Member States can be authorised to provide national assistance to their farmers under state aid rules. In recent years, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Box 3.1) and the energy price hike induced by the Ukraine war (Box 3.2), a broad range of exceptional crisis management measures and aid packages have been adopted both at the Member State and EU level.

The Commission can use public procurement interventions and aids for private storage for a selected number of commodities such as wheat, rice and beef for public buying interventions, and white sugar, olive oil, and pig meat in the case of private storage. Removing products from the market can give a more sustained boost to prices but is a more costly option. Producer organisations in the fruit and vegetables and wine sectors have long been able to institute market withdrawals, green harvesting7 and non-harvesting8 in crisis periods. The Commission was recently given the power to authorise market withdrawals by producer organisations and recognised interbranch organisations for other products (Article 222 of the Common Market Organisation Regulation), and by co-operatives (Omnibus Regulation (EU) No. 2017/2393). This implies that these measures are no longer considered measures of last resort.

The Commission can also grant financial support packages to producers affected by a sudden market crisis. Advance payments can be made from the CAP budget to improve farmers’ liquidity. Funding for additional aid may be available within the financial ceilings for the CAP budget laid down in the MFF (particularly in the past when assigned revenue from fines and disallowances on Member States boosted budget revenue). The CAP 2014-22 also created a special crisis reserve by withholding an amount of direct payments (EUR 400 million in 2011 prices) to fund emergency measures. If the crisis reserve funding was not used in a particular year, it was returned to farmers the following year and a further cycle of withholding was initiated. However, even in a crisis, Member States in the Council were reluctant to activate this mechanism because it implies the redistribution of funds from one group of farmers to another. The mechanism was activated for the first time in 2022 to make up for a shortfall in available funding elsewhere in the CAP budget to fund the EUR 500 million package to support farmers in light of rising input costs, such as energy and fertilisers, further accelerated by Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

An evaluation of crisis measures in the CAP noted that public intervention and private storage measures have become less effective over time as EU producer prices have become increasingly aligned with world market prices (Wageningen Economic Research and Ecorys, 2019[72]). It also pointed to weaknesses in the supply management measures, partly because they are voluntary (giving rise to a free rider problem [see also Mahé and Bureau (2016[73])] and partly because the entities authorised to engage in co-ordination measures may be too small to influence market prices under increasingly open markets.

On the other hand, state aid was seen as flexible and effective, albeit raising issues of fairness between farmers in different Member States and a lack of transparency on risks covered by this ad hoc assistance. The evaluation concluded that there is no need for additional instruments, neither for crisis prevention, preparation or crisis response and recovery.

Mahé and Bureau (2016[73]) were more critical, noting that the European Union lacks financial resources in times of crisis. They proposed legal changes to budgetary rules to allow the crisis reserve to build up to a sizeable war chest. They also suggested the eligibility for particular emergency aid programmes should be conditional on producer participation in risk mitigation schemes and better defined thresholds.

Box 3.1. European and Member States’ policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic plunged the European Union into its worst-ever recession and raised multiple challenges that often compounded the European Union’s existing weaknesses (OECD, 2021[74]). The COVID-19 emergency also caused huge disruptions in food and agricultural markets, but the European food and agricultural systems proved resilient in ensuring that consumers could access food. This is also the result of the broad range of measures that have been adopted on this front at the EU level, including flexibility under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), exceptional market measures, and direct support to farmers and rural areas.

In this framework, Member States responded with their own policy packages, targeting the most affected sectors. In particular, spending on state aid initiatives under the Temporary State Aid Framework soared in 2020 and early 2021, with 22 countries implementing sector-specific aid packages totalling nearly EUR 6.2 billion (USD 7.1 billion), equivalent to more than 11% of CAP expenditure in 2020 (OECD, 2021[75]). Member States also put in place their own regulatory flexibilities, tax concessions and social contribution measures, investment assistance, and allowances to farm households to help farmers and agro-food enterprises cope with the financial impacts of the COVID-19 emergency. Response measures also responded to labour concerns within the sector, ensured minimal interruptions to food supply chains and helped to ensure that affected consumers had adequate access to food.

The European Union also put in place some trade measures in response to COVID-19, but most were unrelated to agriculture. One measure that did impact agricultural supply chains was the designation of Green Lanes to ensure that trans-European trade in goods under a functioning single market could continue even in the presence of internal border controls erected to protect public health (EC, 2020[76]).

Finally, some policies were implemented to facilitate longer term recovery and sector transformation, such as the Recovery Plan for Europe, a long-term recovery initiative from the COVID-19 emergency. In particular, the Next Generation EU initiative under this plan funds some activities for the agricultural sector to support Member States in recovering, repairing and emerging stronger from the crisis.