In addition to equity and bond portfolios, losses on other financial instruments also contributed to negative nominal returns. In a context of rising interest rates, pension plans in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom suffered losses on their interest-rate derivatives held to hedge against the risk of declining interest rates. Dutch pension funds also recorded losses on their real estate investments.4 These losses, combined with those on bonds and equities, led pension plans in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom to record the lowest nominal returns among all reporting jurisdictions (-21.1% and -18.5% respectively).

Meanwhile, pension plans in some countries benefitted from the changes in foreign exchange rates. The rapid rise in interest rates in the United States made US dollars attractive to investors, who sold other currencies to purchase them, which strengthened the US dollar against these other currencies (Alderman, Camp and Mandiak, 2023[2]). Some pension plans achieved foreign exchange gains on their investments abroad, as the domestic currency depreciated against the US dollar (e.g. the Netherlands). These gains offset some of the investment losses and even resulted in positive investment rates of return in some countries (e.g. Zambia).

The method of valuing assets can influence the investment performance results. For instance, the rise in interest rates in domestic government bonds had little effect on the value of bond holdings when pension funds value assets following an amortised cost method based on effective interest rates (e.g. Albania). Similarly, since early 2022, the Demographic Reserve Fund in Poland has also been valuing its debt securities according to the adjusted purchase price determined based on the effective interest rate, as the reserve fund intends to hold its debt securities until maturity. This valuation method does not capture the decline in the price of debt instruments following interest rate hikes in the performance results.

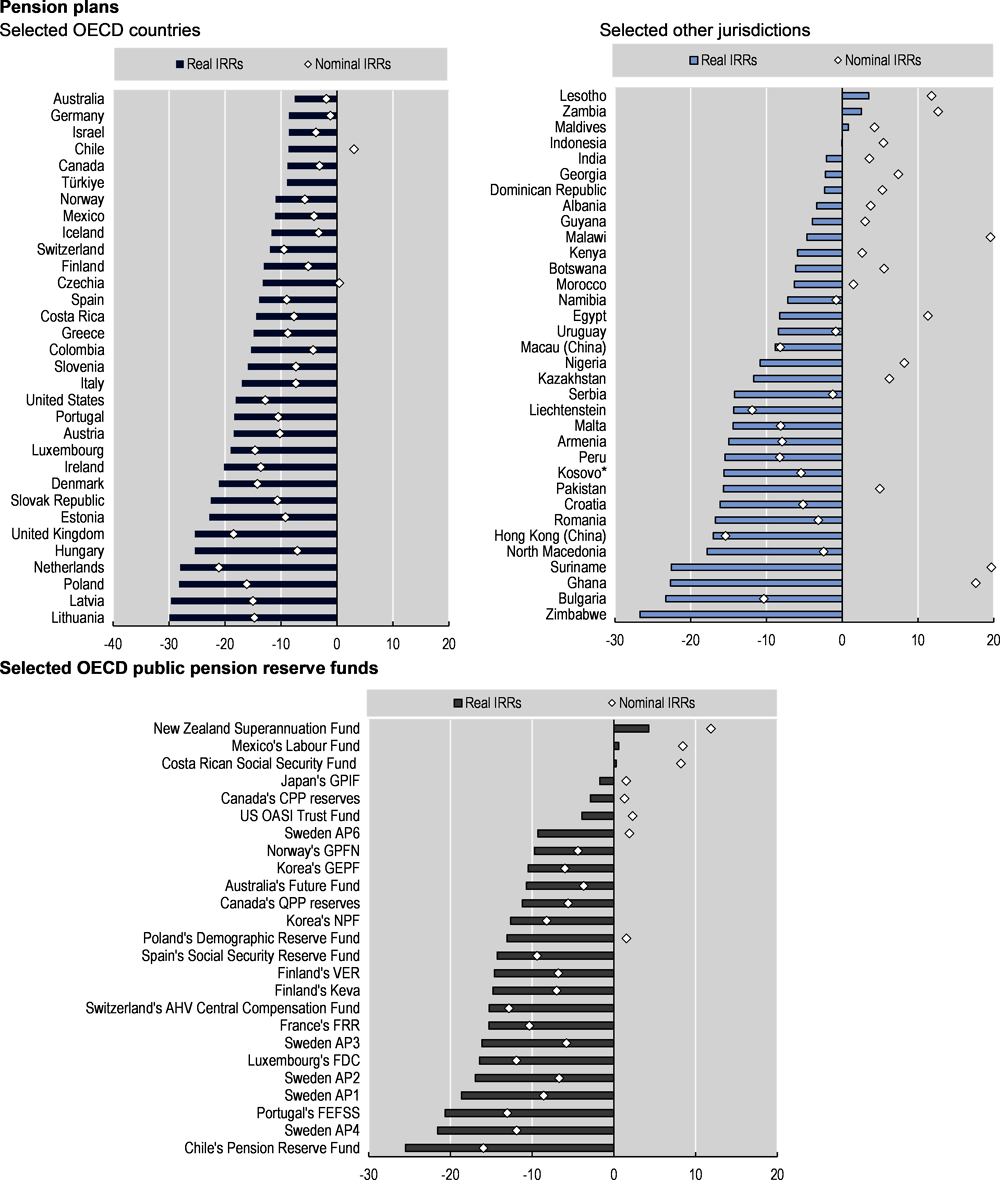

Elevated inflation turned nominal investment gains into real losses and made nominal losses much larger in real terms. Real rates of return were negative for pension plans in all OECD countries and nearly all reporting non-OECD jurisdictions. Real rates of return were the lowest in some of the countries where inflation surged the most (e.g. Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania with annual rates over 20% in December 2022 (OECD, 2023[3]) among OECD countries, and Ghana, Suriname and Zimbabwe outside the OECD, where the consumer price index rose by 52%, 55% and 111% respectively). Most public pension reserve funds also experienced real losses in 2022. Real rates of return were positive in 2022 in just a couple of African countries (Lesotho, Zambia) and the Maldives, where inflation did not offset nominal investment gains.5

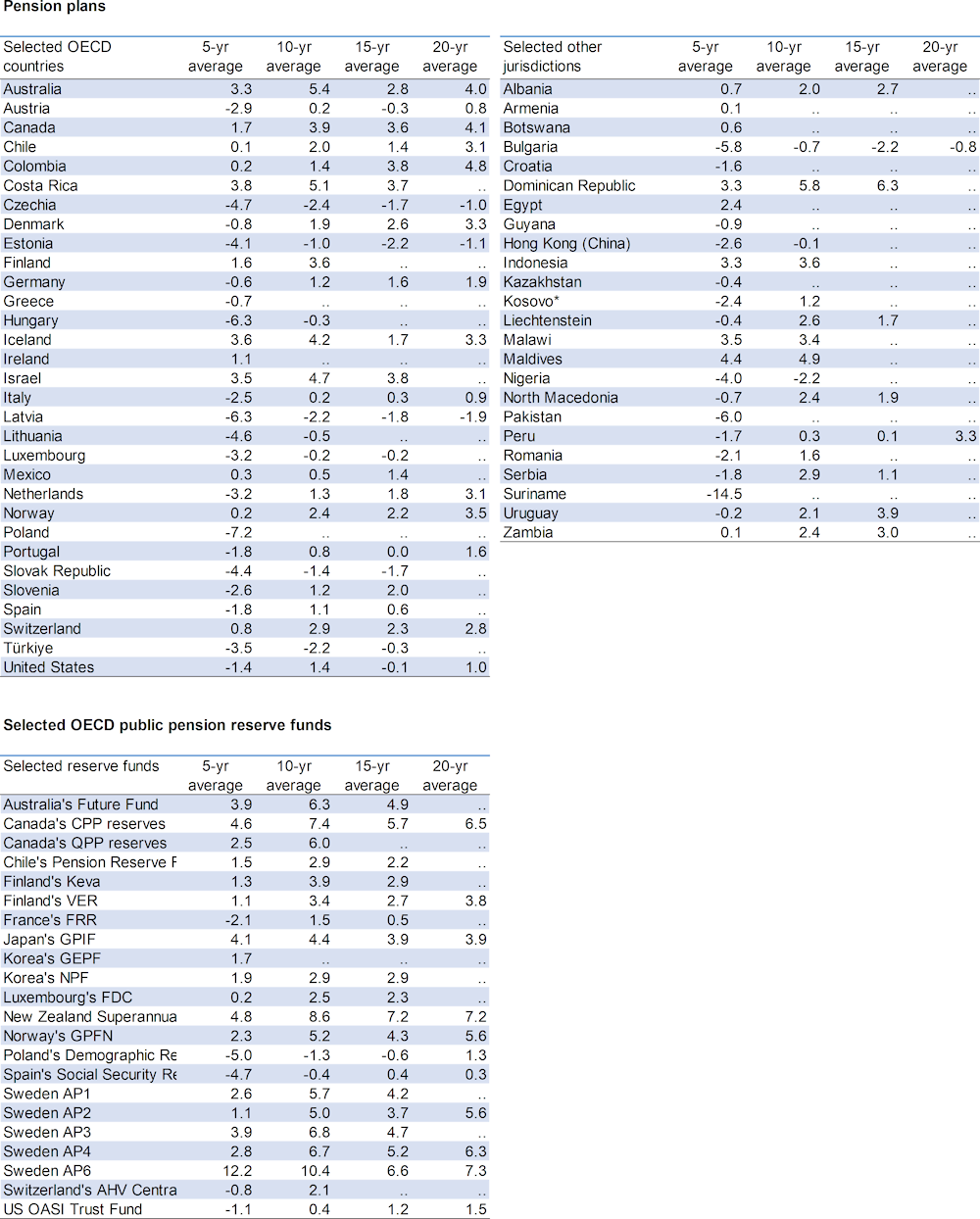

Strong investment gains in the previous years helped to compensate for the losses in 2022 in many jurisdictions. Pension plans reached an average annual return above inflation in 21 out of 55 reporting jurisdictions (i.e. in 38% of the reporting jurisdictions) over the last 5 years, 33 out of 44 (i.e. 75%) over the last 10 years, 24 out 34 (i.e. 71%) over the last 15 years, and 15 out of 19 (i.e. 79%) over the last 20 years (Table 1.1). The investment performance of public pension reserve funds was also positive in real terms over the last 15 or 20 years in all those for which data are available.