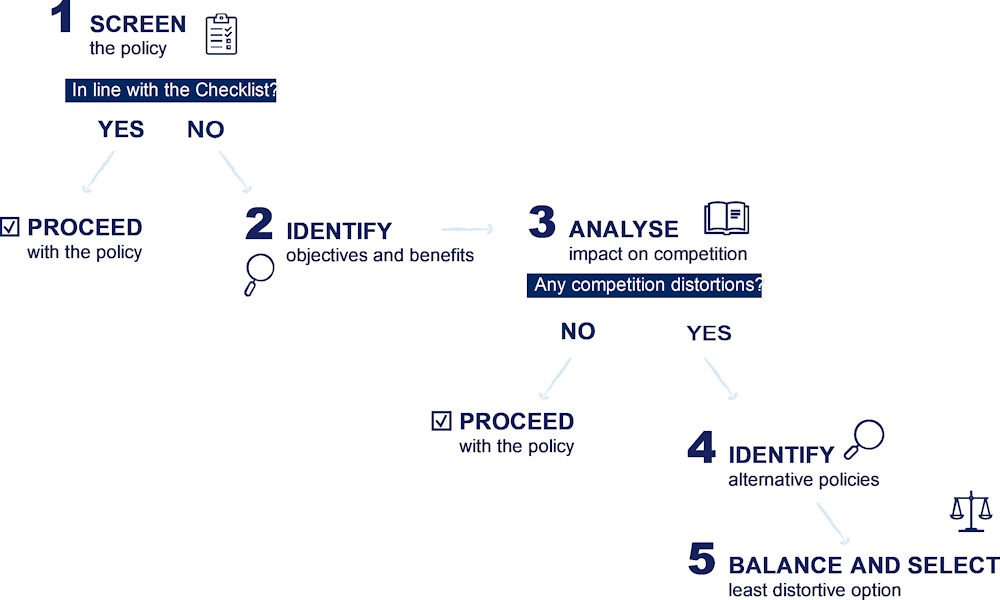

This chapter provides a framework of analysis for identifying and assessing policies that may distort competitive neutrality and for developing alternatives to avoid or reduce such distortions. It is set to be carried out in five steps: (i) screening of the policy intervention using the Competitive Neutrality Checklist; (ii) identification of the policy objective and benefits of the policy intervention; (iii) analysis of the impact of the policy intervention on competition; (iv) identification of alternative policy options; and (v) balancing of benefits and competition distortions, and selection of the most appropriate option.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

8. Framework of analysis

Abstract

The Recommendation recognises that while undue restrictions on competition can occur unintentionally, public policies may often be reformed in a way that promotes competition while achieving their objectives. While the previous chapters present good practice approaches to implement competitive neutrality principles, this chapter provides the overall framework of analysis for identifying and assessing regulations or state support measures that may distort competitive neutrality and for developing alternative policies to avoid or reduce such distortions.

The analysis described in this chapter follows the methodology developed in the OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit and is set to be carried out in five steps, as summarised below:

Figure 8.1. Steps for applying the Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

Note: Step 1 should be conducted for each relevant question of the Checklist. An in-depth analysis should be carried out if the policy intervention in question responds negatively to at least one question.

8.1. Screening of the policy intervention using the Checklist

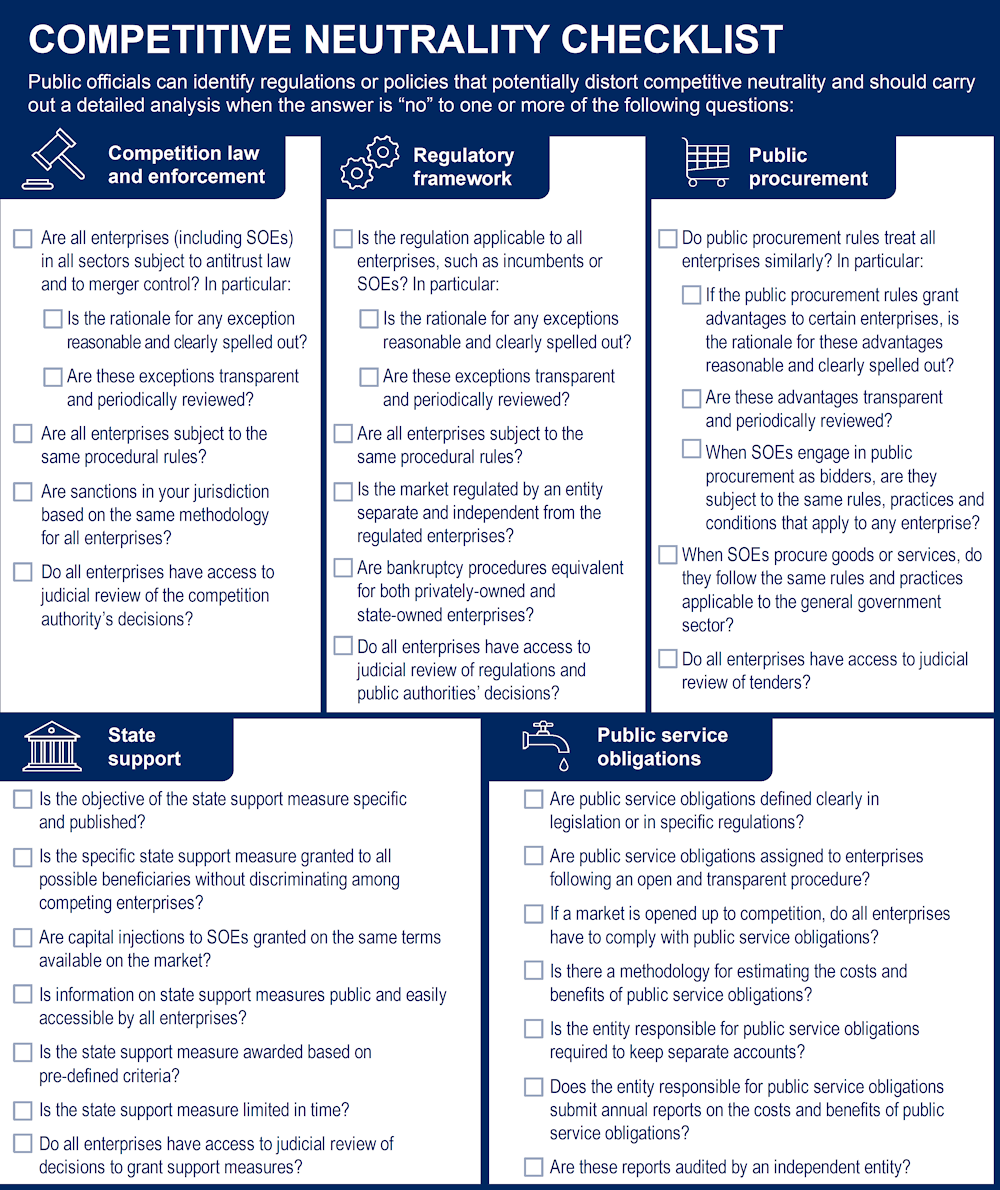

The first step is to screen the policy intervention in question by using a set of questions (Competitive Neutrality Checklist) that indicate when regulations or state support measures may have the potential to distort competitive neutrality. When the Checklist elicits a negative response, an in-depth analysis is suggested, in order to further investigate the policy intervention.

The questions within the Competitive Neutrality Checklist cover the five areas of the Recommendation and aim to identify the most problematic policies that would deserve further analysis. The questions are based on the good practice approaches described in Chapters 3 to 7.1

A few observations should be made:

As the different sections of the Checklist are intended for different types of policy interventions, not all questions are relevant for all measures to be assessed. Thus, the relevant sections of the Checklist are meant to be selected depending on the type of policy intervention to be analysed.

The questions overlap and are not mutually exclusive, which means that a given policy intervention may respond negatively to more than one question.

The Checklist questions simplify the good practice approaches, therefore they do not entirely reflect the full content of the good practice approaches. In consequence, the Checklist should be used in conjunction with the good practices in Chapters 3 to 7.

An in-depth analysis is suggested when a measure elicits a negative response to at least one question.

Figure 8.2. Competitive Neutrality Checklist

8.2. Identification of the objective and benefits of the policy intervention

After identifying a regulation or state support measure that is likely to distort competitive neutrality, it is suggested to identify the objective of the policy intervention and the tangible outcome that it intends to achieve. This is relevant to evaluate the benefits of the policy intervention and whether there are less restrictive alternatives that can achieve the same objective (see section 8.4). Besides the understanding of the rationale for the policy measure, an understanding of the broader regulatory environment and the technical features of the sector may also be useful, particularly to carry out the following steps.

In some cases, the policy objective can be identified in the regulation or state support measure itself. In other circumstances, this can be found in higher level legislation, in parliamentary debates or in supporting documents to the policy measure when it was enacted.2

When assessing a policy intervention, one should focus on whether and to what extent the relevant public policy is likely to result in economic benefits, such as lower production costs, better quality products or more innovative products. Nevertheless, there may be non-economic benefits from the government intervention, e.g. policies to address climate change to ensure a liveable environment, public health measures to protect the population from disease, support measures for defence purposes, etc. Each of these benefits are to be assessed at least qualitatively to determine whether they are significant, for example drawing from the Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) conducted for the policy.3

It is also suggested to determine, for each of the benefits identified, the extent to which the benefit is a public benefit as distinct from a private benefit. For example, if a grant or state support measure reduces the cost of R&D to a firm, this will be a private benefit (i.e. it saves money). However, it will also be a public benefit to the extent that the R&D successfully results in the development of new/different products or saves resources when producing existing products.

Furthermore, as public benefits may not be all equally significant, applying weights might be useful. These weights may not be precisely defined, but, for example, it is likely that more weight will be given to benefits which flow through to consumers or the broader community than to benefits which are retained by businesses themselves.

The following may be used to inform the weights that could be attached to the various types of public benefits claimed:

A public benefit would generally be given more weight the broader its impact across the community and the more numerous the beneficiaries.

Cost savings that release resources for use elsewhere in the economy attract greater weight than if there are no resource savings.

The benefit will attract greater weight if it is likely to be sustained over time.

8.3. Analysis of the impact of the policy intervention on competition

Once the objective of the regulation or state support measure is identified, its impact on competition is to be evaluated. While the screening identifies policies that may have potential to distort competitive neutrality, it does not necessarily indicate the degree of competition harm that may be produced. Therefore, it is suggested to assess whether a policy intervention that is likely to harm competitive neutrality indeed distorts competition and if so, whether that distortion is significant.

First, it is good to build a basic understanding of the economics of the sector and key market characteristics. Second, the impact of the policy intervention on the market would be assessed as regards incumbents and new entrants, prices, quality / variety and innovation. While the Toolkit methodology does not cover the definition of relevant markets, some analysts using the Toolkit may choose to engage in market definition, in line with the analysis usually conducted by competition authorities. Guidance in this respect can be found in (OECD, 2019[1]), Appendix A.

Identifying the key characteristics of the market involves analysing both the supply side and the demand side (OECD, 2018[2]).4 The characteristics of the product and whether any of them leads to market failures, such as asymmetric information or externalities, can be relevant to the process. On the supply side, the analysis includes understanding how firms compete, their production and pricing strategies, the distribution chain and the barriers to entry and exit. On the demand side, it may be useful to categorise consumers, for example based on their behaviour, the alternatives available to them and the costs associated to switching.

To assess the impact of the policy intervention, one should ask whether the policy under consideration could distort competition in the market in question or any of the related markets (OECD, 2019, pp. 19-30[1]).5 This includes determining the effect of the public policy on existing or potential market participants, which will depend on the market characteristics, such as how concentrated the market is.

Several aspects could be considered when assessing the impact of the policy intervention on the market. The level of detail of the analysis will depend on factors such the availability of granular data (for instance, through information requests to the relevant market players) and of resources, as well as how quickly the assessment should be concluded. In particular, one could assess whether the regulation or state support measure affects (OECD, 2019, pp. 97-102[1]):

Incumbent businesses, for example whether these can substantially reduce the intensity of competition in the market.

Entry of new firms, for instance whether the intervention creates barriers to entry or places new entrants at a disadvantage.

Prices of goods and services, as well as production, for example whether the intervention imposes costs on one or more suppliers that may lead to higher prices paid by consumers and lower production by the market players.

Quality and variety of goods and services, for instance whether the government measure will have a negative impact on quality and variety.

Innovation, for instance whether firms will have less incentives or resources to pursue innovative activities.

Market’s growth, for example by assessing the growth of production and sales, as well as new capital investments.

There are certain market characteristics that can make distortions of competition more or less likely. These are related to how firms competed in the market before the intervention and include the degree of market concentration, product differentiation, barriers to entry and exit and switching costs (HM Treasury; Office of Fair Trading, 2007[3]).

Concentration.6 The more firms there are in a market the less impact is likely from providing one of those firms with a competitive advantage. However, if an advantage is provided to a single large firm in that market the presence of other firms may cease to provide much of a constraint on the recipient. For instance, this could be because the intervention helps the large firm acquire a position of market power, e.g. a regulation granting exclusive rights to a firm.

Product differentiation. When products are differentiated, consumers do not consider them as easily substitutable and are less likely to modify their consumption in response to relative price changes. Therefore, the intensity of competition may be lower compared to a market where products are all nearly identical. In this situation, if a competitor receives assistance the distortion on competition may be less pronounced than if products were more similar.

Barriers to entry and exit. If barriers to entry are low, the advantage acquired as a result of a policy intervention is likely to be relatively short-lived. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consider the likelihood that entry will occur, whether the entrants will be an effective market constraint and the timeliness of entry.

In the presence of switching costs, for example when supplier-consumer relations are governed by long lasting or automatically renewed contracts, the intensity of competition may be reduced because it may be costly to convince existing customers to switch.

Besides assessing the effects on the primary market under consideration, it is also suggested to examine the impact of the government intervention on related markets, particularly upstream and downstream markets. If after a preliminary analysis it is observed that there are likely to be significant effects on competition in related markets, the assessment described in the paragraphs above could be carried out for each related market that might be affected (i.e. impact on incumbents and new entrants, prices, quality and variety, as well as innovation and market’s growth) (OECD, 2019, pp. 104-105[1]).

The box below presents some high-level assessments of the impact of policy interventions on competition.

Box 8.1. Examples of the impact of the policy intervention on competition

Example 1

There are four players in the market for production and distribution of tea in a small jurisdiction. Tea is a very popular drink and there are no substitutes.

Company A has a market share of 50%; B 20% and C and D each have a share of 15%. It is difficult to obtain approval from the Health Authorities in the jurisdiction to import tea because they are concerned about the quality and safety of imports. The following state support measures are applied:

The government grants an advantage to all market players to improve their distribution methods. No anticompetitive impact since all market participants receive the advantage.

The government grants an advantage to A aiming to create a national champion. This is likely to have an anticompetitive impact because A will have a substantial advantage over its far smaller competitors in circumstances where imports are unlikely.

The government grants advantages to the three smaller players to make their production and distribution methods more sustainable given the critical issues facing the environment. It considers that Company A is profitable enough to do this for itself. The advantage will spur innovation in these relatively small companies. While this may raise issues of fairness, the advantage is unlikely to reduce competition on the basis that it is likely to spur innovation and efficiency. If in fact there is any anticompetitive market impact, it should be examined against its likely public benefits given the purpose of the advantage, and potential less restrictive alternatives.

Example 2

The government continues to consider the position of the tea industry. It decides that it will provide a guarantee to various companies in the market:

The government guarantees a very large loan to Company A so that it can modernise its plant and produce the final product more efficiently. This is likely to have a substantially anticompetitive effect since the smaller competitors will not have the same advantage and a more efficient large competitor could price them out of the market.

The government guarantees loans to all players to make their plants more efficient. This will not reduce competition since all receive the loan and can continue to compete on their merits, albeit more efficiently.

The government guarantees loans to the smaller players so that they can better compete with Company A. This may or may not reduce competition but is more likely to increase it given the respective markets shares of the players in the tea market.

Example 3

The government brings in a procurement policy for its suppliers of tea to government offices in an effort to obtain tea at cheaper prices. The government buys 50% of the tea in the jurisdiction:

The first policy term requires the winning provider to supply all of the tea for government for the foreseeable future. This is likely to reduce competition in the market for the production and supply of tea, since only company A has the stock levels to satisfy this condition into the long term. There is no good reason why others should not be able to compete for market share on price in this situation, since all of the products are the same. Companies B, C and D will effectively be excluded from a large share of the tea market.

The second policy term is that the contract uses an exclusive digital ordering platform which only Company A has access to. It is new to the government and only larger companies can really afford to use it. It offers little benefit over and above the current ordering mechanism which all players can access and which works well. This is likely to reduce competition in the market for the supply of tea since not all the players can use it and there appears to be no good reason for using it.

8.4. Identification of alternative policy options

As stated in the preamble of the Recommendation, “public policies may often be reformed in a way that promotes competition while achieving their objectives”. In addition, “other things being equal, public policies with lesser harm to competition should be preferred over those with greater harm to competition, provided they achieve the identified objectives”. Therefore, when steps 1 to 3 of the methodology lead to the conclusion that a regulation or state support measure distorts competition, the next step would be to look for alternative options that may achieve the policy objective without distorting competitive neutrality or by distorting competitive neutrality to a lower extent, and that equally and efficiently fulfil the objective of the regulation or support measure.

It is therefore advisable to identify all the alternative policies that can achieve the public objective, assessing both the benefits and the impact on competition of each option. As indicated in the Competition Assessment Toolkit, identifying feasible alternatives to a public policy is a fact-specific exercise and requires a good understanding of the policy and a substantial industry expertise (OECD, 2019, p. 72[4]).

The Competition Assessment Toolkit presents some guidance that can help develop alternatives. For example, it suggests looking at the experience of other jurisdictions, as well as to consult relevant stakeholders and potential new players. It also provides some examples of less restrictive measures that may be used in a wide range of cases dealing with the regulatory framework (OECD, 2019, pp. 72-79[4]).

When more than one alternative is possible, it is a good practice to analyse each of the options in order to determine which of them is the less distortive way of achieving the policy objective (see section 8.5). However, if some of the potential alternatives are not feasible, they are not to be considered in the next step.

In some circumstances one alternative can be removing (or not introducing, depending on the situation) the regulation or state support measure in question, for example when the policy objective can be achieved without any state intervention or when the policy objective is not achieved in practice by the policy.7 In other cases, abolishing the policy in question may not be a conceivable alternative, for instance when there are relevant policy objectives that cannot be achieved without state intervention (e.g. for environmental or security reasons). In addition, addressing competitive neutrality issues may sometimes require changing the structure of the intervention (e.g. introducing tax credits may be less distortive than granting exclusive rights).

Finally, it should be noted that in some circumstances there may be no alternatives that can achieve the policy objective. As a result, the regulation or state support measure will be maintained provided they are indeed justified by clear policy objectives. As recognised in the preamble of the Recommendation, “achieving public policy objectives will in certain circumstances require exceptions to competitive neutrality”. This is part of the balancing process between the objective and benefits of the intervention and the distortions of competition (see Section 8.5). Nonetheless, as highlighted in the good practice approaches, exceptions to competitive neutrality necessary to accomplish an overriding public policy objective should be transparent, narrowly applied and periodically reviewed to determine whether they are necessary and limited to achieving their objective.

8.5. Balance of benefits and competition distortions and selection of the least distortive option

The last step of the exercise is balancing the benefits and the competition distortion for the policy intervention in question and the alternatives that were identified. This aims to determine which of the options is the least distortive way of achieving the policy objective. For that purpose, one should consider the benefits and restrictions of each of the options. The feasibility and institutional capacity for each option, as well as the unintended consequences that can arise from each of the alternatives, should also be taken into account.

The Competition Assessment Toolkit provides relevant guidance on how to compare the options, presenting several techniques of qualitative and quantitative comparison, as summarised in Box 8.2 below.

Box 8.2. Qualitative and quantitative techniques to compare the options

According to the OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit, comparison between different options can be based on qualitative or quantitative analysis.

Qualitative assessment mixes facts and argumentation to indicate reasoned judgments about which is the preferable option. While qualitative analyses are widely understood, require little data and are quickly and practically carried out, they are more subject to external criticism and do not identify the value of enhancing competition.

The following are examples of qualitative techniques to compare alternatives:

Argumentation (i.e. use of critical thinking or informal logic)

Comparison of pros and cons in a list

Points-based analysis

Quantitative assessment involves careful and rigorous estimation of the benefits of some options compared to others, providing numerical range of impacts. Since quantitative analyses require more technical skills, availability of data and time to be completed, they are more frequently used for significant or controversial issues.

The examples below show quantitative methods that can be used to compare options:

Price comparisons

Outcome effect in regulatory reform elsewhere

Experiments

Demonstration projects

Consumer benefits estimates

Source: OECD (2019, pp. 81-113[4]), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 3. Operational Manual, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

After comparing all the options in question, it might be possible to conclude that the existing (in case of ex post evaluations) or the proposed (in case of ex ante evaluations) measure is the least distortive alternative, meaning that the government could proceed with the policy intervention. As already mentioned, the Recommendation recognises that exceptions to competitive neutrality may be accepted if required to achieve a country’s overriding policy objectives, as long as they do not go beyond what is strictly necessary to achieve such objectives and that distortions to competition are limited to the extent possible. Additionally, the good practice approach is for any exceptions to competitive neutrality to be transparent, narrowly applied and regularly reviewed.

On the other hand, if an alternative policy is considered to be less distortive than the original measure under consideration, it would be good practice to promote that option, either through advocacy initiatives (if the exercise is conducted by the competition authority) or through actual implementation (if conducted by the policy maker itself), if both are equally efficient and adequate for achieving the goal.

References

[3] HM Treasury; Office of Fair Trading (2007), Guidance on how to assess the competition effects of subsidies, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/competition-impact-assessment-guidelines-for-policymakers.

[6] OECD (2021), “Methodologies to measure market competition”, OECD Competition Committee Issues Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/methodologies-to-measure-market-competition.htm.

[1] OECD (2019), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 2. Guidance, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

[4] OECD (2019), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 3. Operational Manual, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

[2] OECD (2018), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Argentina, https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/Argentina-SOE-Review.pdf.

[5] OECD (2017), OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Mexico 2017, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278011-en.

[7] US Office of Management and Budget (2023), Guidance on Accounting for Competition Effects when Developing and Analyzing Regulatory Actions, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/RegulatoryCompetitionGuidance.pdf.

Notes

← 1. In line with the Recommendation on Transparency and Procedural Fairness, the Competitive Neutrality Checklist also includes questions about judicial review.

← 2. The Competition Assessment Toolkit provides further guidance on how to identify the purpose of the policy (OECD, 2019, pp. 65-66[4]).

← 3. Information about the benefits expected to result from a public policy may be available because they are included as policy objectives and because governments are required to justify their public policy initiatives given that they are funded from the public purse. To this end, there is likely to be a requirement that new policy initiatives or adjustments to existing policies are justified using a Regulatory Impact Assessment, whether applied formally or informally. In this consideration, what is accepted as a benefit must be considered a realistic outcome from the policy, rather than something that is merely speculative.

← 4. More details on the process and methodologies to analyse market characteristics can be found in (OECD, 2017[5]).

← 5. The OECD Competition Assessment Toolkit (OECD, 2019, pp. 19-30[1]) provides an overview of the concepts and framework to assess competition in markets. See also (US Office of Management and Budget, 2023[7]).

← 6. Concentration is one of various measures of competition, see (OECD, 2021[6]).

← 7. In some cases, the policy objective is not specific or is not clearly related to the intervention. Under these circumstances, the real policy objective may not be the one stated explicitly. If there is no relation between the stated policy objective and the intervention, one reasonable course of action may be not to proceed with the intervention.