Although regulation is often required to ensure that markets work well and deliver outcomes that are in line with government’s policy objectives, it is necessary to ensure that the regulatory framework and its enforcement maintain a level playing field to all enterprises, regardless of their ownership, location or legal form. This chapter presents a set of questions to guide the analysis, good practices and examples on how to implement the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality in the regulatory environment.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

4. Regulatory framework

Abstract

The Recommendation provides that jurisdictions should maintain a level playing field in the regulatory environment, for instance concerning public procurement and bankruptcy law.

The regulatory framework can distort competitive neutrality, both in substance and application. In the first case, selected market players (e.g. SOEs, domestic or foreign enterprises) may be subject to a regulatory framework that is, in substance, different from and more favourable than that applying to their competitors. In the second case, although subject to the same framework, some players may be exempted from specific provisions. This can be formally foreseen in the law or result from the decision maker’s discretion. In both circumstances, some enterprises will have preferential market access or enjoy special terms for operating in the market (OECD, 2021, p. 10[1]).

The uneven application of a regulatory framework, or provisions, on market participants can be a source of competitive advantage (or disadvantage) and it is thus likely to distort the natural selection process of the most efficient firms in the market, which may lead to higher prices, lower quality and less innovation.

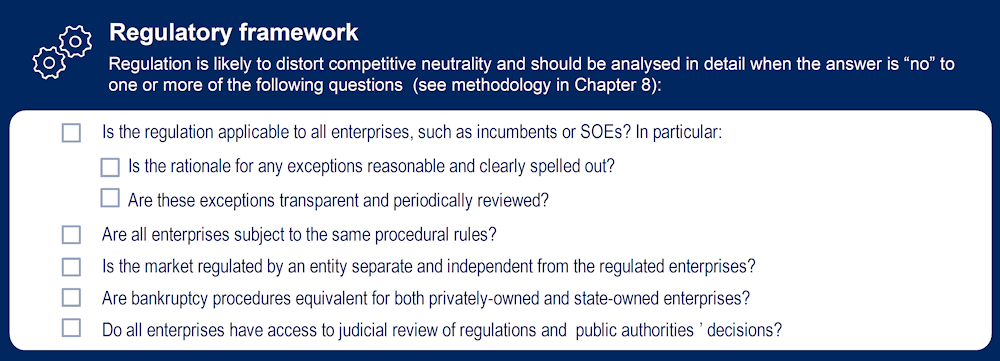

A set of questions to help identify policies that can potentially distort competitive neutrality is presented below. When a policy is not in line with at least one of the questions or good practice approaches, it has the potential to distort competition and should be analysed in detail. Chapter 8 sets out the main steps of the analysis.

Figure 4.1. Suggested questions to assess the regulatory framework

4.1. The regulatory environment should be competitively neutral and should be enforced with equal rigour, appropriate deadlines and equivalent transparency with regard to all current or potential market participants

According to the Recommendation, jurisdictions should “maintain Competitive Neutrality in the regulatory environment”. Therefore, all market players, both current and potential, should receive a uniform treatment not only in terms of the legal framework but also its enforcement. Moreover, transparency should be ensured in the enforcement of regulations, for instance by publishing regulators’ decisions, so that market participants gain a better understanding of how regulations are interpreted in practice and can monitor whether regulations are indeed being applied in a non-discriminatory way.

If the regulatory environment is not uniform or if regulations are not applied in an equal manner in a market, this risks distorting the level playing field, as some firms will enjoy the advantages of a more favourable regulatory environment.

As mentioned above, this may affect the competitive process driven by enterprises competing on the merits, unless a regulatory exception or asymmetric regulation is needed (see the good practice approaches 4.4 and 4.5). An uneven playing field may also discourage new entry, for instance if regulations set technical standards or other requirements in a prescriptive way, therefore excluding the possibility that new entrants may supply goods and services in alternative and innovative ways.

Examples

The following examples illustrate how this good practice approach is implemented in practice:

In Brazil, a “proposal for amending the rules of the SeAC (conditional access services) emerged in a public consultation conducted by the Brazilian telecommunications regulatory agency (Anatel). The proposal sought to require premium television providers to employ Direct-to-Home technology to install Integrated Receiver Decoders (i.e. hybrid set-top boxes) in subscribers’ homes. […], this obligation would only apply to Direct-to-Home service providers, not to cable TV providers who are part of SEAC, which would create a strong competitive distortion. Anatel properly decided not to make the installation mandatory” (OECD, 2021[2]).

In Czechia, a 2016 act aimed at preventing tax evasion required retailers to register sales electronically and send the corresponding payment information to the tax administration. However, e-shops did not have immediate access to payment information, which in certain cases could take place on delivery. The requirement was therefore adapted in the case of e-shops, who had to transmit the necessary information only when the payment took place and no later than the time of the delivery (OECD, 2019[3]).

In Greece, travel agencies operating online and without a physical office could not offer the full range of services provided by their counterparts with a physical presence. For instance, they could not provide package holidays. An OECD competition assessment review found that the regulation limited the range of suppliers and considered that the policy maker’s objective to protect consumers was ensured by the application of consumer protection legislation to all types of travel agencies (OECD, 2014[4]). This distinction was removed from the legislation.

In the United Kingdom, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) raised concerns that some providers in the higher education sector in England were not subject to the regulation designed to ensure quality of education. One of the negative consequences identified by the CMA was that unregulated providers would not have sufficient incentives for providing quality services to students. The authority also considered that the unequal treatment could harm students, who may not realise that some of the institutions were operating outside the regulatory framework (CMA, 2015[5]). In 2017, the Higher Education and Research Act established the Office for Students, whose duties include the promotion of quality and greater choice and opportunities for students and the encouragement of competition between English higher education providers.1

4.2. When a licensing or authorisation system is in place, no exceptions should be granted to enterprises, based on criteria such as ownership, nationality or legal form

Laws and regulations may require enterprises to obtain a licence or an authorisation to operate in the market, based on well-founded objectives, such as consumer protection (OECD, 2019[6]). Nevertheless, competitive neutrality issues may arise if selected players are exempted from some or all licensing or operating requirements, or if there is discrimination in the application of requirements because of decision maker discretion. Indeed, instances where firms are fully or partially excluded from certain requirements because of their status (e.g. SOEs, previous monopolists or incumbents) can emerge, as also highlighted in section 4.3 below. Likewise, regulatory bodies may have discretion as to whether to impose certain qualification requirements or grant a licence (OECD, 2021, p. 10[1]).

Exempting certain enterprises from licensing or authorisation requirements based on criteria such as ownership, nationality or legal form may reduce entry costs, operating costs or administrative burdens of favoured firms compared to other market players. Such exceptions can distort competition in the relevant sectors, resulting in discrimination and providing advantages to selected market participants.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of pursuing competitive neutrality in the regulatory framework:

In the EU, when a licensing or authorisation framework is provided for by the legislation (e.g. air transport services2 and electricity distribution), this framework applies to all enterprises, regardless of whether they are SOEs or private-sector providers.

In Greece, state-owned marinas used to benefit from more favourable treatment in relation to licensing requirements (OECD, 2014, p. 180[4]). In particular, according to Article 166, par. 6 of Law 4070/2012, marinas managed and used by the state-owned Greek Real Estate Company were exempt from the obligation to submit operational and sustainability plans and were not subject to control for the issuance of their licence by the relevant agency. According to Paragraph 7 of the same article existing marinas with no operating licence were not subject to control by the relevant agency if they submitted the documentation provided for in this article. An OECD competition assessment review found that these provisions discriminated in favour of state-owned marinas against those that were privately-owned. In 2014, a new law removed the differential treatment.

In Mexico, licences and authorisations in the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors are required by all market players, including SOEs. For instance, in 2022, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT) examined the request of the modification of concession titles held by an SOE and considered whether this would unduly affected competition (IFT, 2022[7]).

4.3. Regulations should not exempt incumbents from new and stricter requirements

Good practices highlight that incumbent firms are not treated differently vis-à-vis new entrants, for example with regard to new and stricter requirements. For instance, this would be the case when regulations include so-called grandfather clauses, allowing incumbents to continue operations under older rules while new firms are subject to newly imposed rules and regulations. Grandfather clauses may grant temporary or permanent exceptions from the new rules to the incumbents (OECD, 2019, pp. 62-63[8]). Where such exceptions exist, they are justified with the argument that incumbents entered the market and chose to invest under the previous rules, therefore a sudden change in rules would create uncertainty and possibly jeopardise return on investment.

Even though grandfather clauses can present a legitimate economic justification in specific cases, they generally impose asymmetric standards on market participants and are likely to impose considerably greater costs on new entrants and new capital investments by incumbents. Therefore, depending on the extent of the burden imposed and the cost asymmetry, grandfathered regulations can discourage new entry, reduce new investment by incumbents, allow continuation of inefficient production by older more inefficient plants and lead to higher prices (OECD, 2019, p. 65[8]).

If grandfather clauses are inevitable, good practices show that consideration is given to reducing the duration of the adjustment period as much as possible, as well as making the period dependent on firm-specific characteristics, such as technology, vintage of capital and firm size (OECD, 2019, p. 67[8]).

A recent country study conducted by the OECD showed that licensing requirements for private-sector providers did not apply equally to the relevant SOEs, nor were the SOEs subject to any regulatory fees. It was observed that the difference in the regulatory treatment between SOEs and private-sector providers often derives from the fact that the SOEs were already active (often as monopolists) in the countries before licensing systems were introduced. The conclusion was that the different treatment was a clear advantage for the relevant SOEs in terms of regulatory costs and burden, and recommended levelling the playing-field between the SOEs and their private-sector competitors.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In Brazil, taxes could only be paid to the Federal Revenue Office through financial institutions. Other payment institutions, such as Fintechs, were prevented from providing such services, which compelled customers from these institutions to also have an account in a traditional bank to pay their taxes. In order to ensure a level playing field among all financial institutions, Fintechs were authorised to be part of the federal tax collection network since 2020, following an initiative by the Secretariat of Competition Advocacy and Competitiveness (SEAE) (OECD, 2021[2]).

In Iceland, the 1990 Fisheries Act introduced individual transferable quotas (ITQ) giving fishers permanent quotas that they could also lease or sell. The policy was introduced to restrict fishing given that marine resources were being irreparably depleted. Despite the regulation’s success in achieving its policy objective, the grandfathering of ITQ led to the uneven treatment of incumbents and new entrants. Subsequent amendments attempted to mitigate this impact, for instance by granting exceptions to new entrants relying on more eco-friendly fishing methods (OECD, 2017[9]).

In the Philippines, a truck age limit was enforced for new entrants but not for incumbents. In practice, this meant that new applicants wanting to use trucks over a certain age would not be granted a licence, but incumbents could renew their licence. The discrimination ended on June 2020, when the new roadworthiness rules entered into force banning trucks over 15 years old from the market for trucks for hire (OECD, 2020, pp. 65-66[10]).

In the US, alternatives to grandfathering have been adopted in environmental legislation to control pollution. As opposed to some emission trading schemes granting allowances or credits to existing polluters, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) established an auction system for all allowances. Under the RGGI, set up by ten US states, existing plants did not benefit from free allowances or less-stringent emissions standards (Damon et al., 2019[11]).

4.4. Any exceptions from regulations should be transparent, should be justified by clear policy objectives and should be narrowly applied

While the Recommendation calls for competitive neutrality in the regulatory environment, it recognises that “achieving public policy objectives will in certain circumstances require exceptions to competitive neutrality”. Exempting certain players from regulations may be necessary to achieve policy objectives that could not be accomplished through other means. For instance, as market players launch new products and services, it may take time to consider whether new regulations are needed and if so, to design them. In these cases, policy makers may grant temporary exceptions from regulation.

Good practices show that distortions are limited by ensuring that the exceptions are transparent, duly justified and narrowly applied. Transparency means ensuring that all market participants are informed about them and their rationale. When exceptions are adopted in a transparent way and are publicly known, this can allow for open discussion on the merits of the exception, and for objections and alternative proposals to be put forward and considered. Moreover, good practices highlight that exceptions adopted in order to achieve a specific public objective do not go beyond what is strictly necessary to achieve the objective, so that distortions to competition are limited to the extent possible.

For example, in many jurisdictions SOEs are exempted from regulatory requirements which private operators are required to comply with, without a clear and objective justification. In those cases, SOEs face reduced entry costs, operating costs and/or administrative burdens when compared to other market players, which unduly distorts competition.

Examples

The following examples are meant to show how exceptions can be justified by a specific policy objective, be transparent and narrowly applied:

In Korea, following the 2008 financial crisis, the government decided to delay the application of 280 regulations for two years, during the economy’s recovery from the crisis – so-called Temporary Regulatory Relief (The Republic of Korea, 2009[12]). The initiative was time-bound, had a clear policy objective and applied to all enterprises. (Malyshev et al., 2021[13]) notes that the “programme was successful in bolstering private sector investment and consumption and reducing the regulatory burden on small and medium enterprises”.

Regulatory sandboxes grant temporary waivers from certain regulations to allow companies to experiment with innovative products or services in a predictable legal environment. Sandboxes allow regulators to observe the development of new products or services and to learn how best to regulate them at the end of the temporary waiver. These tools have emerged in a wide range of sectors (notably in finance, but also in health, transport, legal services, and energy), especially when involving innovations driven by digital technologies and data (Attrey, Lesher and Lomax, 2020[14]). For instance, Singapore has launched a number of regulatory sandbox initiatives to support innovation in the areas of telemedicine, environmental technologies and agri-food innovation, among others. Innovators are given regulatory leeway in testing and implementing new business models, services and products (Leimüller and Wasserbacher-Schwarzer, 2020[15]). Box 4.1 below illustrates the UK experience with sandboxes in the financial services market.

Exempting SMEs from some requirements or making them less burdensome is often considered to promote SMEs development. A number of countries assess the impact of proposed regulations specifically on SMEs. One of the elements of these “SME Tests” is the identification of alternative or mitigating measures, including full or partial exceptions from the proposed regulation. For instance, in the UK the first step of the SME Test is to assess whether SMEs can be exempted from the proposed regulation. If an exception is not feasible, the potential impact of the draft regulation on SMEs is evaluated. When negative impacts are considered to be disproportionate, policy makers propose mitigating measures or, if these measures are not practicable, they explain why this is the case (OECD, 2021, p. 79[16]).

In the US, federal agencies have the flexibility to grant waivers or exceptions from regulations to individuals or entities, when those regulations may not be suitable to those individuals or entities. The Administrative Conference of the United States has issued a set of recommendations on this matter, including, for example, that “agencies should consider soliciting public comments before approving waivers or exceptions” (ACUS, 2017[17]).

Box 4.1. The UK Financial Conduct Authority’s Regulatory Sandbox

The UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) launched the Regulatory Sandbox initiative in 2016, aiming to promote more effective competition by allowing businesses in the financial services market to test innovative propositions in a live market environment, while ensuring that appropriate safeguards are in place.

The Regulatory Sandbox provides innovators, both incumbents and new players, with access to regulatory expertise, giving firms the ability to test products and services in a controlled environment; the opportunity to find out whether a business model is attractive to consumers, or how a particular technology works in the market; a reduced time to market at potentially lower cost; and support in identifying consumer protection safeguards that can be built into new products and services.

The Sandbox is dedicated to authorised firms, unauthorised firms that require authorisation and technology businesses that are looking to innovate in the UK financial services market. Firms of all sizes, at all stages of development and from all sectors of financial services are entitled to apply to the Regulatory Sandbox. Firms in the Sandbox may be provided with tools to conduct the test within the regulatory framework. These tools include restrict authorisation, signposting, informal steer, individual guidance, waivers or modifications to rules and no enforcement action letters.

In 2017, after the first year of operation of the Regulatory Sandbox, the UK FCA published a report on the lessons learned. The sandbox was considered successful in meeting its overall objectives, including reducing the time and cost of getting innovative ideas to market, helping access to finance for innovators and enabling products to be tested and introduced in the market. It has also allowed the regulator to work with innovators to build appropriate consumer protection safeguards into new products and services.

Sources: FCA (2022[18]), Regulatory Sandbox, https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox; FCA (2017[19]), Regulatory sandbox lessons learned report, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research-and-data/regulatory-sandbox-lessons-learned-report.pdf.

4.5. Enterprises should not be ultimately responsible for regulating the market(s)

The Recommendation states that "Enterprises, regardless of their ownership, location or legal form, should not be responsible for regulating the market(s) in which they currently or potentially compete, (especially regarding entry of expansion of existing players)”.

This provision is especially relevant in situations where the state both regulates a market and conducts economic activities, for example through SOEs. According to the SOE Guidelines, when SOEs undertake economic activities there should be a clear separation between the state’s ownership function and other state functions that may affect the market conditions for SOEs, particularly with regard to market regulation and policy making [OECD/LEGAL/0414], in order to ensure a level playing field.

The independence of regulators from both the regulated entities and from the government is a tenet of good governance in sectors such as network industries and the financial sector (OECD, 2016[20]). This is likely to be especially important where SOEs and privately-owned enterprises compete in the same market and are subject to regulation. (OECD, 2016, p. 36[20]) notes that independence “helps create an assurance of a ‘level playing field’, whereby market competitors will not benefit from undue advantages or preferential treatment in light of their state-owned status”.

While independent regulators have been set up in many countries, there are still certain activities where the same entity may be responsible both for the provision of services and for their regulation. According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) there are SOEs with regulatory powers in about one in five countries in the EBRD regions (European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2020, p. 55[21]).3 In addition, in some jurisdictions, sector regulators are not independent from the government. Given the role of the government as owner and as regulator, the latter may have an incentive to benefit SOEs, as promoting competitive neutrality may ultimately lower SOEs profitability.

Examples

The following are selected examples of regulatory bodies that are independent of enterprises that compete in markets:

In Czechia, the Energy Regulatory Office (ERO) is the authority responsible for regulating the energy sector and was established by the Energy Act (No. 458/2000 Coll.). ERO does not “have any economic activities, any ownership interests in domestic or foreign companies” (OECD, 2019[22]).

In Italy, the incumbent consortia in the waste and recycling sector were also involved in the accreditation process of alternative systems, which created a conflict of interests. In 2022, following the enforcement and advocacy initiatives of the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM), a new independent entity was established to monitor the authorisation process for new collection and recycling consortia in compliance with the environmental legislation (OECD, 2023[23]).

In Latvia, the SOE “Road Traffic Safety Directorate” operated simultaneously as a market participant and a market supervisor. The SOE was responsible for accrediting companies to conduct vehicles’ technical inspections as well as for monitoring their compliance with the regulation, while at the same time it was a shareholder of these firms. In 2018, the Competition Council of Latvia (CC) carried out a market study and concluded that this framework distorted competitive neutrality, restricting entry of potential new competitors in the vehicles’ technical inspection market. The CC recommended to separate monitoring regulatory compliance and commercial activities. It also proposed the liberalisation of the market, removing state participation from the commercial activities. As a result, the Latvian government decided to remove state participation from the commercial activities, by selling the SOE’s shares in the accrediting companies (OECD, 2020[24]).

In Mexico, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT) acts as an autonomous body from a functional and budgetary standpoint, free from political influence and able to provide independent regulation based on transparent processes and evidence-based decision making (OECD, 2017, pp. 27-28[25]).

4.6. Regulations may be imposed asymmetrically when necessary to promote competition

In some cases, good practices across jurisdictions show that regulations may treat incumbents and smaller competitors differently to promote greater contestability. For instance, asymmetric regulation has been common in markets where SOEs used to provide services under exclusive rights that have been liberalised. This is especially the case in network industries where the incumbent often retains substantial market power. Moreover, some jurisdictions have recently introduced ex ante regulations to supplement existing ex post competition law enforcement in the digital economy. These regulations apply only to a sub-set of players (the largest digital firms) rather than to all firms in the market (OECD, 2022[26]).

In these cases, some behaviours can be imposed on certain firms (usually those with significant market power) to promote competition, e.g. by allowing new entry and preventing small players from being excluded from the market. It is necessary, however, that asymmetric regulations are justified by clear policy objectives and are regularly reviewed, in order to prevent unnecessary restrictions on competition.

For instance, some jurisdictions have implemented liberalisation initiatives in the rail sector, aiming to allow new entrants into the market at the downstream retail level. Nevertheless, the incumbent is usually both the operator of the network and one of the retail providers of services. When the legislation does not impose any asymmetric rules on the incumbent to ensure third-party access to the existing infrastructure, in practice such initiatives have not resulted in more competition.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In network industries, vertically integrated companies that control a key infrastructure facility are often subject to asymmetric regulation. This regulation is imposed only on the companies that control the key infrastructure to address the risk that they favour their own subsidiary to the detriment of competing suppliers. For instance, under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services, national regulatory authorities are required to assess if any undertaking holds Significant Market Power (SMP) in certain markets which are considered susceptible to ex ante regulation, such as the market for wholesale local access (European Commission, 2018[27]). Wholesale local access is an input for the provision of broadband access at retail level. National regulatory authorities can impose regulatory requirements on those undertakings found to hold SMP.

In Lithuania, in the context of the liberalisation of the retail electricity supply market, the Competition Council of Lithuania recommended to policy makers that the incumbent supplier be prevented from launching marketing campaigns towards customers, using data that only it had access to, before this opportunity became available to all other potential electricity providers in the liberalised market. To ensure effective competition between all electricity suppliers after the liberalisation of the market, the Competition Council recommended the removal of the advantage that the incumbent had compared with its competitors. The recommendation of the Competition Council was followed by the policy makers (OECD, 2022[28]).

In Mexico, the Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT), which is the body enforcing competition law in the broadcasting and the telecommunications sectors, has the power to determine the existence of preponderant economic agents in the broadcasting and the telecommunications markets if they hold 50% of users, audience, traffic or use of network capacity. IFT can impose on the preponderant players measures needed to ensure fair and open competition. This comprises measures related to information, supply and quality of services, exclusive agreements, limitations on the use of terminal equipment between networks, asymmetric regulation on tariffs and network infrastructures, including the accounting, functional or structural separation of their essential elements. Every two years, based on economic and regulatory performance indicators, IFT assesses whether the asymmetric ex ante regulation imposed on the preponderant players should be eliminated or reviewed (Mexico, 2014[29]).

The UK government’s newly created Digital Markets Unit (DMU) will have powers to designate tech firms that hold “substantial and entrenched market power”. These will be required to follow a new code of conduct aimed at supporting and enhancing competition in the sector (United Kingdom, 2022[30]).4 Similarly, the EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA)5 establishes a set of criteria for qualifying a large online platform as a “gatekeeper”, which will be required to comply with obligations and prohibitions listed in the DMA.

The US President’s 2021 executive order on competition notes a deterioration of competition in the railway sector and identifies problems with access to infrastructure. To remedy this competition issue, it encourages the sector regulator to impose asymmetric regulation to “require railroad track owners to provide rights of way to passenger rail and to strengthen their obligations to treat other freight companies fairly” (The White House, 2021[31]).

4.7. Regulations should be regularly assessed, also in light of changed market circumstances, to ensure that they do not distort competition

The Recommendation provides that jurisdictions should “carry out competition assessments that identify and revise existing or proposed regulations that unduly restrict competition”. This provision is also consistent with the Recommendation on Competition Assessment [OECD/LEGAL/0455], according to which “governments should introduce an appropriate process for revision of existing or proposed public policies that unduly restrict competition and develop specific and transparent criteria for evaluating suitable alternatives.” More broadly, the provision is in line with the Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance [OECD/LEGAL/0390], which state that jurisdictions should “conduct systematic programme reviews of the stock of significant regulation against clearly defined policy goals, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations remain up to date, cost justified, cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives”.

Laws and regulations may distort competition in the marketplace, for instance when new and stricter standards do not apply to incumbents. By regularly reviewing existing laws and regulations, governments may identify distortions of competition and develop alternative, less restrictive policies that still achieve government objectives. Moreover, regular review ensures that the level playing field is maintained over time as the regulatory environment evolves to address new market and technology developments. Box 4.2 describes the wide-ranging programme implemented by Australia in the 1990s.

However, ex post reviews of regulations (including as regards competition) are still limited in practice, even among OECD Members. For instance, in 2021 only one quarter of OECD Members had systematic requirements to carry out ex post evaluations, with numbers essentially unchanged since 2014 (OECD, 2021, p. 87[16]).

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of assessment of regulations in practice:

In Italy, there is an obligation to consult the competition authority on new regulatory proposals. In addition, the authority can submit to the government comprehensive proposals to amend laws and regulations to remove distortions and restrictions of competition. In 2021 the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM) issued a number of proposals on limiting the extension of concessions to incumbents and on improving competition for public contracts. The authority also identified some competitive distortions in the electricity market (Autorita' Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato, 2021[32]).

In Korea, the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) has the power to conduct ex-ante and ex-post reviews of regulation. According to the latest data available, in 2022 the KFTC reviewed ex ante 941 new and amended regulations within 546 laws and made recommendations to revise 30 existing anti-competitive regulations which it assessed ex post (OECD, 2023[33]).

In Latvia, legislation proposals should be accompanied by ex-ante impact assessment, which includes their effect on competition. In addition, the opinion of the Competition Council (CC) is required on draft regulations related to matters of competition protection and development. The CC can also provide opinions on draft regulations, when they have a potential effect on competition, even in instances when the competent ministry has not requested its opinion (OECD, 2021[34]).

In Mexico, competition authorities Federal Economic Competition Commission (COFECE) and Federal Telecommunications Institute (IFT, with competition powers on the telecommunications and broadcasting sectors) have the power to issue non-binding recommendations on laws and regulations that can have a negative impact on competition (OECD, 2022[35]).

In Peru, the National Institute of the Defence of Competition and Intellectual Property Protection (Indecopi) can “engage in the ex-post review of regulations of secondary legislation issued by any other public entities such as municipalities and ministries (secondary legislation, such as decrees, municipal ordinances, agreements and resolutions) in relation to their illegality or unreasonableness” (OECD - IDB, 2018[36]). Indecopi has the power to order their removal and impose fines of up to USD 25 000 for non-compliance.

In the United Kingdom, the Enterprise Act 2002 gives the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) extensive powers to review sector regulations and make recommendations to the government and/or impose remedies where competition issues are identified. For instance, the CMA used this power to advocate for pro-competitive reforms regarding regulations on airport slot allocation (CMA, 2018[37]) and legal services (CMA, 2016[38]).

Box 4.2. Australia’s National Competition Policy Programme

One of the most successful examples of pro-competitive reform occurred when Australia implemented broad, pro-competitive reforms at both national and state level in the mid-1990s. Australian federal, state and municipal governments implemented the National Competition Policy (NCP), a decade-long process to systematically review regulation to remove anti-competitive provisions and strengthen pro-competitive regulation and institutions.

The NCP included measures such as improving governance and introducing structural reforms to government business to make them more commercially focused and expose them to competitive pressure; regulatory arrangements to secure third-party access to essential infrastructure services and, more generally, to guard against overcharging by monopoly service providers; review and amend of a wide range of legislation which restricted competition.

The NCP has delivered substantial benefits to Australia, including higher economic growth and associated strong growth in household incomes, reduced prices of goods and services, as well as stimulation of business innovation, customer responsiveness and choice.

Sources: OECD (2019[39]), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 1. Principles, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm; Australian Government Productivity Commission (2005[40]), Review of National Competition Policy Reforms - Productivity Commission Inquiry Report, No. 33, 28 February 2005, http://ncp.ncc.gov.au/docs/PC%20report%202005.pdf; Corden (2009[41]), Australia’s National Competition Policy: Possible Implications for Mexico, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/45048033.pdf.

4.8. Competitive Neutrality should be maintained in the enforcement of bankruptcy law

According to the Recommendation, competitive neutrality should be maintained in the enforcement of bankruptcy law, “so that competing Enterprises are subject to equivalent […] bankruptcy rules, irrespective of their ownership, location or legal form, and that the enforcement of those laws does not discriminate between State-Owned Enterprises and their private competitors, or between different types of privately-owned Enterprises”. This good practice approach is consistent with the SOE Guidelines, according to which SOEs should be subject to bankruptcy and insolvency rules equivalent to those for comparable competing private enterprises [OECD/LEGAL/0414].

Although many jurisdictions’ bankruptcy rules apply to both SOEs and privately-owned enterprises, in some cases there are exceptions due to SOEs’ specific legal status (OECD, 2021[1]) . In addition, in some jurisdictions even though SOEs are formally subject to bankruptcy law, their creditors cannot initiate bankruptcy or administration procedures. In others, legislation exempts SOEs from liability to execution, which means that their assets cannot be taken away, either by execution of a judgement, debt or insolvency.

Moreover, even when SOEs may not be formally exempt from insolvency legislation, they may effectively be shielded from insolvency procedures due to soft budget constraints, that is limited financial discipline imposed by the state on SOEs. Bankruptcy risks are also mitigated by other forms of support received by financially troubled SOEs, such as bail outs and debits being frozen, restructured, eliminated, or transferred to other SOEs.

Providing some firms with more favourable bankruptcy rules may create barriers to exit and prevent the dynamic competitive process from selecting the most efficient players, as less efficient firms may remain in the market because of the different treatment provided by the legislation or its enforcement (OECD, 2019[42]).

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of competitive neutrality in bankruptcy law:

In Latvia, SOEs are not exempt from any laws and regulations that apply to private enterprises. This includes insolvency or bankruptcy procedures which are equally applicable to commercially and non-commercially oriented SOEs (OECD, 2015[43]).

In Norway, SOEs may go into bankruptcy, regardless of their legal form of incorporation, as they are subject to the same legislation as privately-owned companies (Norway Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries, 2019[44]).

In Spain, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) published an opinion on the 2019 draft bill to reform the Consolidated Text of the Bankruptcy Law, noting that the new bankruptcy law leaves open the possibility of derogations from the application of the insolvency rules to public bodies. The CNMC underlined how tensions may arise in the application of bankruptcy rules to public operators active on the market which, in light of the principle of competitive neutrality expressed in the OECD Recommendation, should be treated in the same way as private operators (CNMC, 2021[45]).

References

[17] ACUS (2017), Administrative Conference Recommendation 2017-7, Regulatory Waivers and Exemptions, Adopted December 15, 2017, https://www.acus.gov/recommendation/regulatory-waivers-and-exemptions.

[14] Attrey, A., M. Lesher and C. Lomax (2020), The role of sandboxes in promoting flexibility and innovation in the digital age, OECD Going Digital Toolkit Notes, No. 2, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/cdf5ed45-en.

[40] Australian Government Productivity Commission (2005), Review of National Competition Policy Reforms - Productivity Commission Inquiry Report, No. 33, 28 February 2005, http://ncp.ncc.gov.au/docs/PC%20report%202005.pdf.

[32] Autorita’ Garante della Concorrenza e del Mercato (2021), Proposal for pro-competitive reforms, https://www.agcm.it/dotcmsCustom/getDominoAttach?urlStr=192.168.14.10:8080/C12563290035806C/0/914911A1FF8A4336C12586A1004C2060/$File/AS1730.pdf.

[37] CMA (2018), Advice for the Department for Transport on competition impacts of airport slot allocation, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/888765/CMA_advice_on_DfT_on_competition_impacts_of_airport_slot_allocation.pdf.

[38] CMA (2016), Legal services market study - Final report, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5887374d40f0b6593700001a/legal-services-market-study-final-report.pdf.

[5] CMA (2015), “An effective regulatory framework for higher education”, A policy paper, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/550bf3c740f0b61404000001/Policy_paper_on_higher_education.pdf.

[45] CNMC (2021), IPN/CNMC/035/21: APL de Reforma del Texto Refundido de la Ley Concursal, https://www.cnmc.es/expedientes/ipncnmc03521.

[41] Corden, S. (2009), Australia’s National Competition Policy: Possible Implications for Mexico, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/45048033.pdf.

[11] Damon, M. et al. (2019), “Grandfathering: Environmental Uses and Impacts”, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, Vol. 13/1, pp. 23-42, https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rey017.

[21] European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (2020), Transition Report 2020-21, https://www.ebrd.com/news/publications/transition-report/transition-report-202021.html.

[27] European Commission (2018), “Guidelines on market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services”, Communication from the Commission, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018XC0507(01)&rid=7.

[18] FCA (2022), Regulatory Sandbox, https://www.fca.org.uk/firms/innovation/regulatory-sandbox.

[19] FCA (2017), Regulatory sandbox lessons learned report, https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research-and-data/regulatory-sandbox-lessons-learned-report.pdf.

[7] IFT (2022), El Pleno del IFT autoriza concentración en Altán y emite opinión en competencia económica para modificar el contrato APP de la Red Compartida Mayorista. (Comunicado 60/2022) 21 de junio, https://www.ift.org.mx/comunicacion-y-medios/comunicados-ift/es/el-pleno-del-ift-autoriza-concentracion-en-altan-y-emite-opinion-en-competencia-economica-para.

[15] Leimüller, G. and S. Wasserbacher-Schwarzer (2020), Regulatory Sandboxes - Analytical paper for BusinessEurope, https://www.businesseurope.eu/sites/buseur/files/media/other_docs/regulatory_sandboxes_-_winnovation_analytical_paper_may_2020.pdf.

[13] Malyshev, N. et al. (2021), “Regulatory quality and competition policy in Korea”, 12 ways Korea is changing the world, http://www.oecd.org/country/korea/thematic-focus/regulatory-quality-and-competition-policy-in-korea-e5b4137d/.

[29] Mexico (2014), Ley Federal de Telecomunicaciones y Radiodifusión, https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/346846/LEY_FEDERAL_DE_TELECOMUNICACIONES_Y_RADIODIFUSION.pdf.

[44] Norway Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries (2019), The state’s direct ownership of companies, https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/44ee372146f44a3eb70fc0872a5e395c/en-gb/pdfs/stm201920200008000engpdfs.pdf.

[33] OECD (2023), Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Korea - 2022, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/AR(2023)21/en/pdf.

[23] OECD (2023), Competition in the Circular Economy – Note by Italy, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WD(2023)37/en/pdf.

[26] OECD (2022), Analytical note on the G7 inventory of new rules for digital markets, https://www.oecd.org/competition/analytical-note-on-the-g7-inventory-of-new-rules-for-digital-markets.pdf.

[35] OECD (2022), Annual Report on Competition Policy Developments in Mexico - 2021, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/AR(2022)25/en/pdf.

[28] OECD (2022), Competition in Energy Markets – Note by Lithuania, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2022)19/en/pdf.

[16] OECD (2021), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en.

[34] OECD (2021), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities - Note by Latvia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)22/en/pdf.

[2] OECD (2021), Roundtable on The promotion of competitive neutrality by competition authorities - Note by Brazil, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)36/en/pdf.

[1] OECD (2021), The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Discussion Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-promotion-of-competitive-neutrality-by-competition-authorities-2021.pdf.

[10] OECD (2020), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Logistics Sector in the Philippines, https://doi.org/10.1787/28843772-en.

[24] OECD (2020), OECD Roundtable on Using Market Studies to Tackle Emerging Competition Issues - Note by Latvia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2020)9/en/pdf.

[42] OECD (2019), “Barriers to Exit”, OECD Competition Policy Roundtable Background Note, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2019)15/en/pdf.

[39] OECD (2019), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 1. Principles, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

[8] OECD (2019), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 2. Guidance, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

[6] OECD (2019), Competition Assessment Toolkit: Volume 3. Operational Manual, https://www.oecd.org/competition/assessment-toolkit.htm.

[22] OECD (2019), OECD Roundtable on Independent Sector Regulators - Note by Czechia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP2/WD(2019)14/en/pdf.

[3] OECD (2019), Survey of regulations affecting competition in light of digitalisation, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/WP2(2019)1/en/pdf.

[25] OECD (2017), OECD Telecommunication and Broadcasting Review of Mexico 2017, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264278011-en.

[9] OECD (2017), Sustaining Iceland’s fisheries through tradeable quotas, OECD Environment Policy Paper No. 9, https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Policy-Paper-Sustaining-Iceland-fisheries-through-tradeable-quotas.pdf.

[20] OECD (2016), Being an Independent Regulator, The Governance of Regulators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264255401-en.

[43] OECD (2015), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Latvia, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/ca/OECD-Review-Corporate-Governance-SOE-Latvia.pdf.

[4] OECD (2014), OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Greece, OECD Competition Assessment Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264206090-en.

[36] OECD - IDB (2018), OECD-IDB Peer Reviews of competition law and policy: Peru, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-idb-peer-reviews-of-competition-law-and-policy-peru-2018.htm.

[12] The Republic of Korea (2009), Temporary Regulatory Relief - A New Experiment in Regulatory Reform in Korea, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/45347546.pdf.

[31] The White House (2021), Fact Sheet: Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/07/09/fact-sheet-executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/.

[30] United Kingdom (2022), A new pro-competition regime for digital markets - Consultation document, https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/a-new-pro-competition-regime-for-digital-markets/consultation-document-html-version.

Notes

← 1. Another CMA proposal concerned a more flexible fee cap on accelerated courses, that is degrees where the number of weeks of teaching of a standard degree are condensed over a shorter and more intensive timespan. See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/accelerated-degrees-approved-by-mps (accessed on 29 September 2023).

← 2. Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 September 2008 on common rules for the operation of air services in the Community (Recast).

← 3. The regions are Central Europe, the Baltics, South-eastern Europe, Eastern Europe and the Caucus, Southern and Eastern Mediterranean, and Central Asia.

← 4. The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act was passed in May 2024 but at the time of writing the relevant provisions have not yet commenced, see https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3453.

← 5. Regulation (EU) 2022/1925 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 September 2022.