Competition is an integral dimension of public procurement. Establishing open, fair, non-discriminatory and transparent conditions in public procurement helps promote efficiency, ensure that goods and services offered to public entities match their preferences more closely, and lead to lower prices, better quality, more innovation and higher productivity. This chapter presents a set of questions to guide the analysis, good practices and examples on how to implement the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality in public procurement.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

5. Public Procurement

Abstract

Competition is an integral dimension of public procurement, as more competitive tenders help achieve better value for money. The Recommendation on Fighting Bid Rigging in Public Procurement [OECD/LEGAL/0396] recognises that competition in public procurement promotes efficiency, helping to ensure that goods and services offered to public entities match their preferences more closely, leading to lower prices, better quality, more innovation and higher productivity.

Therefore, the Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality provides that government procurement processes should follow open, fair, non-discriminatory (e.g. ownership, nationality or legal form) and transparent conditions, so that all potential suppliers can take part in public tenders, and all bidders are treated in an equitable manner.

Competitive neutrality is meant to be ensured in both public procurement rules and practices. Public procurement rules comprise not just public procurement legislation, but also how it is implemented in tenders and actual processes.

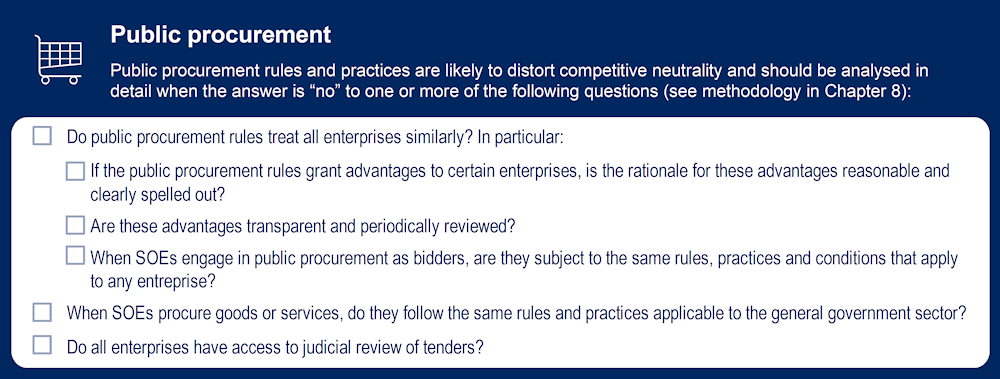

A set of questions to help identify policies that can potentially distort competitive neutrality is presented below. When a policy is not in line with at least one of the questions or good practice approaches, it has the potential to distort competition and should be analysed in detail. Chapter 8 sets out the main steps of the analysis.

Figure 5.1. Suggested questions to assess public procurement

5.1. Ensure that public-procurement rules treat all potential bidders in a similar way, without discrimination and irrespective of ownership, legal form, nationality and origin of goods

According to the Recommendation, jurisdictions should ensure that potential bidders are treated in a similar way in government procurement processes, regardless of their ownership, nationality or legal form.

In addition, competition may be distorted if government procurement processes contain a preference for domestically produced goods. Recalling that the Recommendation calls on jurisdictions to maintain competitive neutrality irrespective of enterprises’ location, bidders should also be treated equally irrespective of the origin of goods they supply.

The Recommendation intends to ensure a level playing field among all potential bidders, increasing competition and therefore leading to better value for money. In practice, public procurement legislation often favours specific types of players, such as SOEs, incumbents, domestic companies or firms providing goods that are produced largely domestically (see Box 5.1). For instance, there are jurisdictions where SOEs as bidders receive a more favoured treatment in public procurement processes. However, offering advantages to some market players over others can distort competition and ultimately lead to the selection of less suitable bidders, resulting in higher prices, lower quality and less innovation.

Box 5.1. Rules of origin

Rules of origin establish the criteria used to define where a product was made (i.e. the economic nationality or the country of origin of goods), which is particularly relevant for implementing trade policy measures, such as trade preferences and quotas. The WTO Agreement on Rules of Origin and the WCO International Convention on the Simplification and Harmonisation of Customs Procedures recognise two basic criteria for defining the origin of a product for non-preferential treatment: (i) wholly obtained or (ii) substantial transformation.

The wholly obtained criterion defines the country of origin of a good where the product has been wholly produced or (for non-manufactures goods) grown, harvested or extracted. Therefore, to be considered originally from a given jurisdiction, the product must not use any foreign components or materials.

The substantial transformation criterion determines the country of origin for processed goods where the last substantial transformation occurred, and this transformation can be broadly described as enough to give its essential character to a product.

Sources: WTO (2023[1]), Rules of Origin, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/roi_e/roi_e.htm; OECD (2016[2]), Participation in Global Value Chains in Latin America: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policy, Working Party of the Trade Committee, https://one.oecd.org/document/TAD/TC/WP(2015)28/FINAL/En/pdf.

This good practice approach is consistent with the Recommendation on Public Procurement [OECD/LEGAL/0411], which also calls for Adherents to “treat bidders, including foreign suppliers, in a fair, transparent and equitable manner, taking into account Adherents’ international commitments”. In this regard, the Checklist for Supporting the Implementation of the Recommendation on Public Procurement indicates that Adherents should ensure that their legal and regulatory framework eliminates any restrictions or barriers for foreign suppliers to participate in public procurement processes (OECD, 2016, p. 19[3]).

It is recognised, however, that there may be sectors that could require a specific treatment for achieving legitimate policy objectives. For example, in the field of defence procurement, governments face a trade-off between open and non-discriminatory procurement processes, on the one hand, and security concerns, on the other hand (Sigma, 2016, p. 10[4]). Defence procurement therefore tends to follow separate rules. For instance, the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) 2012, Article III (1), allows signatories to protect their national interest relating to “procurement indispensable for national security or for national defence purposes” (WTO, 2012[5]). In the EU, defence procurement falls under the Defence and Security Directive (2009/81/EC), instead of the Public Procurement Directive (2014/24/EU).

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of the principle of non-discrimination among potential bidders:

In Australia, the Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines lay out that there should be no discrimination between undertakings on the basis of government ownership. Additionally, the Australian Competitive Neutrality Guidelines clarify that all agencies conducting a tendering process must include a requirement for public sector bidders to declare that their tenders are compliant with competitive neutrality principles (OECD, 2012, p. 83[6]).

In Costa Rica, the Commission for the Promotion of Competition (COPROCOM) carried out a study on a directive issued by the National Treasury on public procurement and concluded that it favoured public enterprises. According to COPROCOM, this distorted competition as it disadvantaged private providers who could supply the same services at a lower price. The directive was later revoked following the advocacy efforts of COPROCOM (OECD, 2021, p. 29[7]).

Under the EU public procurement regime (Directive 2014/24/EU), national contracting authorities in the member states can exclude abnormally low tenders if they are a result of competitive advantages because the tenderer has obtained State aid. Where the contracting authority rejects a tender in those circumstances, it shall inform the EU Commission. The exclusion decision, however, can be challenged before a national court.

In Japan, the standards and ratings concerning the qualification of participants in public procurement tenders shall be standardised and domestic and foreign suppliers shall be treated equally, without any discrimination based on the origin of goods they supply (Enforcement of the Cabinet Order for Partial Revision of the Cabinet Order on Procedures for the Procurement of National Goods, Circular Notice of the Ministry of Finance, 1987).1

In 2020, the Competition Council of Latvia (CC) conducted a market study on the procurement of car transport number plates by the SOE “Road Traffic Safety Directorate”. The study concluded that the tender imposed qualification requirements which favoured the market player that had been providing the service for more than 10 years and which was located in the same building as the SOE on the basis of a rental agreement. For example, bidders were required to produce and deliver car plates in 30 minutes, and only the incumbent was able to comply with it. The Competition Council made several recommendations to increase competition in the bidding process, and the SOE adopted most of them in the following tender. Although the same firm won the bid, the changes created substantial competitive pressure and the price dropped by three times (OECD, 2021[8]).

In Spain, in 2014 the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) challenged an act by the Government of Catalonia, which established that certain purchases should take into consideration, as an evaluation factor, the geographic proximity of the bidder to the procurement authority. CNMC concluded that this lessened competition, as it reduced the ability of firms located further away to compete for the tender. Following the challenge, the Government of Catalonia decided to eliminate the restriction (OECD, 2021, p. 24[7]).

According to the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), “Parties to the Agreement are required to accord to the products, services and suppliers of any other Party to the Agreement treatment ‘no less favourable’ than they give to their domestic products, services and suppliers (…) Further, Parties may not discriminate among goods, services and suppliers of other Parties” The agreement currently covers 49 WTO members (WTO, 2024[9]).

5.2. SOEs as bidders should be subject to the same rules and practices that apply to any other bidder

According to competitive neutrality principles, when SOEs engage in public procurement as suppliers to government entities or other SOEs, they should not be given an undue advantage that distorts competition. In addition, the Recommendation provides that bidding regimes should not favour any category of bidders, including SOEs. In practice, however, SOEs are often granted advantages in public procurement processes, which prevent private players to compete with SOEs on a level playing field.

Good practices show that direct awards of public contracts to SOEs, either from government entities or from other SOEs, are accepted only exceptionally, when this is duly justified and if there are no alternative, less restrictive options, as is the case for all exceptions from open tenders in public procurement. In those cases, the conditions for direct awards are clearly defined in the law, transparent to all, proportionate and periodically reviewed.

This good practice approach is consistent with theSOE Guidelines, which highlight that “when SOEs engage in public procurement, whether as bidder or procurer, the procedures involved should be open, competitive, based on fair and objective selection criteria, promote supplier diversity and be safeguarded by appropriate standards of integrity and transparency, ensuring that SOEs and their potential suppliers or competitors are not subject to undue advantages or disadvantages” [OECD/LEGAL/0414].

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In Argentina, when SOEs act as bidders in public procurement, public ethics regulations act as safeguards to ensure that they do not benefit from undue advantages (OECD, 2018, p. 71[10]).

In Bulgaria, following EU law, SOEs as bidders for public procurement contracts are generally subject to the same requirements as private players. The Public Procurement Act applies equally to SOEs held at the central government and municipality levels. The exceptions to Bulgaria’s public procurement rules may confer an advantage to SOEs as bidders for public procurement contracts if they fulfil the conditions established in Article 12 of the EU Public Procurement Directive (2014/24/EU) (OECD, 2019, p. 102[11]).

The EU Public Procurement Directive (2014/24/EU) also applies to public contracts between entities within the public sector. Recital 31 notes that the “sole fact that both parties to an agreement are themselves public authorities does not as such rule out the application of procurement rules”. However, the Directive does not constrain the public authority’s freedom to perform the public interest tasks that have been conferred on it by using its own administrative, technical and other resources, without being obliged to organise a tendering procedure. Article 12 clarifies the circumstances in which a contract between a contracting authority and a legal person (governed by either public or private law) is not subject to EU public procurement rules. In particular, Article 12 covers the in-house exception, when a contracting authority decides to establish its own company to carry out specific activities provided that specific conditions are strictly met (related to the effective control of the contracting authority over the separate entity and the economic dependence of the separate entity on the contracting authority) (Sigma, 2016[12]).

In Spain, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) has issued a Guide on in-house procurement and horizontal co-operation agreements from a competition advocacy perspective. According to this Guide, public procurers should consider the impact on competition when opting for in-house procurement instead of a competitive tender. The Guide notes that, even if in-house procurement may offer a few advantages over public procurement (e.g. flexibility), its use can entail risks for competition and efficiency by reducing the size of the procurement market and potentially favouring certain suppliers (i.e. in-house providers, which are SOEs). The CNMC recommends that the use of in-house procurement be justified on a case-by-case basis through an ex-ante competition impact assessment. Moreover, for maintaining a level playing field between in-house suppliers and private enterprises, the CNMC recommends avoiding any undue competitive advantage when SOEs compete with other economic operators in both public procurement processes and commercial markets (CNMC, 2023[13]).

5.3. SOEs as procurers should be encouraged to use open tenders, while having a margin of appreciation on the right procurement method if they compete with private sector entities in their market segment

When SOEs engage in public procurement as procurers, they should consider following competitive, transparent and non-discriminatory procedures. Indeed, the Recommendation on Public Procurement recommends that Adherents consider implementing the Recommendation in procurements carried out by SOEs.2 However, SOEs may not necessarily follow public procurement rules, as these rules do not apply to private players that may compete with SOEs that undertake economic activities and could distort the playing field to the detriment of SOEs. Therefore, many jurisdictions provide SOEs with flexibility, while implementing measures to safeguard transparency (see Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. Application of public procurement rules to SOEs engaging as procurers

Countries can provide flexibility in procurement procedures while retaining safeguards to ensure that SOEs act responsibly. The following considerations may be applied when determining the applicability of procurement rules to SOEs:

Funding sources and legal status: the exclusion of SOEs from procurement law may be determined by the percentage of funding they receive from public funds, as well as whether they are allowed to bid as suppliers for government contracts.

Value and scope of in-scope procurements: often, revised rules for SOEs may involve a higher threshold for procurements to qualify for compulsory use of competitive tender. Similarly, specific goods, services and works can be excluded from procurement rules if they have a particular bearing on the SOE’s need for flexibility in business operations.

Approval processes and governance: consideration should be given to the processes surrounding the approval of procurement decisions. For example, ex ante controls can include the need for deviations from procurement rules to be approved by a procurement committee.

Transparency and accountability: by ensuring that SOEs are still subject to rules on publishing contract award notices or justifications for the use of exceptions, governments can ensure that control authorities and civil society have the opportunity to hold SOEs to account.

Source: Reproduced from OECD (2019[14]), Enhancing the Use of Competitive Tendering in Costa Rica’s Public Procurement System, https://www.oecd.org/costarica/costa-rica-public-procurement-system.pdf.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In Brazil, until 2016 SOEs had to follow the same procurement rules applied to all other public bodies, which are extremely strict and comprehensive. Since 2016, SOEs are subject to the SOE Statute (Law No. 13.303/2016), with rules designed to provide simultaneously more flexibility and transparency (OECD, 2020, pp. 108-109[15]).

In Colombia, SOEs are governed by private law when they compete with the domestic or international private and/or public sector and when they operate in regulated markets. SOEs are required to have a procurement manual aligned with the principles of the administrative and procurement function established in the general state procurement statute (OECD, 2015, p. 45[16]).

In the European Union, Directive 2014/25/EU on procurement by entities operating in the water, energy, transport and postal services sectors (Utilities Directive) establishes that public procurement rules apply to the utilities sector, covering not only public entities but also the private undertakings operating on the basis of special or exclusive rights granted by a competent authority of a Member State. The rationale for this approach is that the public interest (i.e. the interest of all users of the service, particularly as regards value for money) must be protected by imposing special rules on how utilities operators (public or private) organise their purchases, in addition to other regulations that may govern their investments and operations. However, the rules on utilities are more flexible than the rules in the Directive 2014/24/EU on public procurement, as entities in the utilities sectors are operating in a more commercial market. This means that although the main principles of the public procurement rules need to be respected, it is also necessary to provide some flexibility to consider the reality of the environment in which they operate. Furthermore, the European Commission may grant an exception from the provisions of the Utilities Directive to contracting entities where, in the Member State in which it is performed, the relevant activity is directly exposed to competition and on a market to which access is not restricted (Sigma, 2016[17]).

In Spain, specific public procurement rules apply to contracts entered into by contracting authorities that are not classified as public administrations (so-called “contracts from other public entities”, such as commercial companies belonging to the public sector), in order to ensure the effectiveness of principles of equality, non-discrimination, transparency, publicity and free competition. However, this does not apply to contracts awarded to undertakings which are mutually owned or mutually-dependent in some cases: (a) if the contracts are aimed at the acquisition of goods or the provision of services that are necessary to carry out the commercial activity of the corporate purpose of the contracting entity and (b) this does not distort competition. The purpose of this exception is to allow companies belonging to the public sector that engage in purely commercial activities to compete on equal terms with the other private operators. Public procurement law envisages that the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) has to issue an opinion assessing the impact on competition arising from contracts directly awarded to affiliated enterprises belonging to the same group (OECD, 2021[18]).

5.4. Any advantages in the procedure granted to specific groups of bidders should be clearly defined in the law and justified by overriding public objectives

Although the Recommendation calls for competitive neutrality in public procurement, its preamble recognises that overriding public policy objectives may require otherwise. Nevertheless, good practices show that any advantages granted to specific groups of bidders are only adopted if necessary to achieve a public policy objective and if there are no alternative, less restrictive measures. Moreover, these advantages are often clearly defined in the law, as well as proportionate and periodically reviewed.

In addition to the primary procurement objective (which according to the Recommendation on Public Procurement “refers to delivering goods and services required to accomplish the government mission in a timely, economical and efficient manner”), some jurisdictions use public procurement to achieve secondary public policy objectives, such as the development of SMEs and standards for responsible business conduct.3 In this regard, the Recommendation on Public Procurement establishes that “any use of the public procurement system to pursue secondary policy objectives should be balanced against the primary procurement objective”. For that purpose, the aforementioned Recommendation provides that it is necessary to (i) evaluate the use of public procurement as one method of pursuing secondary policy objectives in accordance with clear national priorities, balancing the potential benefits against the need to achieve value for money; (ii) develop an appropriate strategy for the integration of secondary policy objectives in public procurement systems, including appropriate planning, baseline analysis, risk assessment and target outcomes; and (iii) employ appropriate impact assessment methodology to measure the effectiveness of procurement in achieving secondary policy objectives.

For instance, some jurisdictions grant preferential measures to SMEs or historically disadvantaged individuals in order to boost their share of the public procurement market. These preferential measures include set-asides and bidding price preferences. In the case of set-asides, a certain share of public procurement contracts is set aside for a targeted category of bidders, meeting the preferential qualification criteria (OECD, 2018, p. 85[19]). Price preferences can be granted to SMEs that take part in procurements not reserved for SMEs.4

In light of the relevance of competition in achieving value for money in public procurement, good practices highlight that governments carefully consider whether measures to promote other public-policy objectives are justified. To this end, governments assess the impact of the measure on the prices paid by public purchasers and compare it with the value obtained as regards the public-policy objective pursued. In addition, they evaluate how effective is the measure in achieving the desired objective and whether there are less restrictive alternatives (OECD, 2021, p. 14[20]).

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach, in particular highlighting advantages specified in the law and addressing an overriding public objective:

Australia has an Indigenous Procurement Policy, launched in 2015, that uses a mix of targets and set asides to increase the participation of indigenous groups in public procurement in terms of volume and value, in line with Exemption 16 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. The policy requires that certain contracts be set aside for indigenous businesses and that a number of other contracts include minimum indigenous employment or supplier use requirements. This includes incentives for participation in high value contracts, or those valued at AUD 7.5 million and higher (Australian Government, 2020[21]). Consideration is given at various stages of public procurement procedures that are designed to support social outcomes and inclusion (OECD, 2019, p. 186[22]).

Canada has established a set-aside programme in 1996 for Aboriginal businesses, aiming to allow that First Nations, Inuit and Métis have a greater opportunity to share in the country in the country’s economic opportunities and prosperity. This includes mandatory set-asides for all procurements over CAD 5 000 for which Aboriginal populations are the primary recipients, and voluntary set-asides that can be used by federal departments and agencies in procuring goods, services, or construction where Aboriginal capacity exists (OECD, 2018, p. 85[19]).

In People’s Republic of China, the Law on Promotion of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises 2002 provides in Article 34 that “in government procurement, preference shall be arranged to goods or services originated from small and medium-sized enterprises”. In addition, the 2011 Interim Measure on Facilitating the Development of SMEs in Government Procurement provides that 30% of government procurement budget shall be set aside to purchase goods and services from SMEs and 60% of such reserved contracts shall be awarded to small or micro enterprises. Furthermore, small and micro enterprises participating in procurement not reserved for SMEs shall be granted a price preference in the range of 6-10% with the exact margin to be determined by the relevant procuring entity or its agent. The Interim Measure also encourages big companies to use SMEs as subcontractors, to form consortia with SMEs, and encourages financial institutions to provide credits/guarantees for SMEs to pay deposits and perform the contract (OECD, 2018, p. 88[19]).

Colombia previously employed strategies that encouraged SMEs in public procurement, which it later consolidated in Decree No. 1082 of 2015. Provisions of this decree give preference to SMEs in public procurement, as well as to undertakings hiring at least 10% disabled people. Some contracts are set aside for micro-enterprises and SMEs exclusively, such as those with a procurement process lower than USD 125 000 and those where at least three micro-enterprises or SMEs express their interest in doing so (OECD, 2018, pp. 218-219[19]).

In the European Union, Article 20 of Directive 2014/24/EU on public procurement allows Member States to “reserve the right to participate in public procurement procedures to sheltered workshops and economic operators whose aim is the social and professional integration of disabled or disadvantaged persons” (such as the unemployed, members of disadvantaged minorities or otherwise socially marginalised groups).

Japan aims to support SMEs in public procurement, as laid out in the Act on Ensuring the Receipt of Orders from the Government and Other Public Agencies by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises as well as the Basic Policy on State Contracts and Small and Medium Enterprises. The latter sets target amounts for contracts between public entities and micro-enterprises and SMEs, approved by the Cabinet (OECD, 2018, p. 180[19]).

Korea’s Public Procurement Service (PPS), the centralised purchasing body, legally prioritises SMEs in public procurement. Combined with other legislation, the Act on Facilitation of Purchase of Small and Medium Enterprise-Manufactured Produce and Support for Development of their Markets, as of 2009, allows PPS to set aside certain products to be exclusively procured from SMEs. It also gives SMEs bid preferences, by gaining additional “points” in their assessment, as well as priority to SME-developed technology products (OECD, 2018, pp. 182-183[19]).

Mexico’s Law for the Development of the Competitiveness of the Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprise, as well as the Law of Acquisitions, Leases, and Services of the Public Sector, aims to increase the participation of SMEs in the market, namely through promoting their participation in public procurement. This legal framework allows agencies to gradually increase their share of SME awarded contracts to reach 35% of their volume, to pay SMEs in advance, give extra points (where evaluation is based on points) to SMEs that employ innovation and technology, and give preference to bidders affiliated with national SMEs (OECD, 2018, pp. 189-190[19]).

In the Philippines, according to the General Appropriations Act, the government is asked to procure at least 10% of its total purchases from duly registered cooperatives and another 10% from SMEs (Gourdon, 2018, p. 27[23]).

Poland’s Public Procurement Law dictates that the contracting authority may limit competition in favour of businesses belonging to people from socially marginalised groups. These include those who are unemployed, have mental disorders, minorities, the homeless, and refugees. This follows Article 20 of the 2014 Directive, which also allows for such reserved contracts (OECD, 2019, p. 28[24]).

In Spain, the National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) has recommended to conduct an ex ante and ex post competition impact assessment when pursuing other secondary public policy objectives in public procurement. The CNMC recalls that the use of social or environmental criteria in public procurement procedures must be objective, strictly limited to the purpose of the contract and respectful of the principles of public procurement (i.e. value for money, transparency, no discrimination and free competition). The CNMC recommends achieving secondary public policy objectives through the promotion of competition and not at the expense of competition among potential bidders (CNMC, 2023[25]; 2021[26]).

In the United States, Subpart 19.7 of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) also has set-asides for small businesses under federal law. When market research concludes that small businesses are available and able to perform the work or provide the products being procured by the government, those opportunities are “set aside” exclusively for small business concerns (OECD, 2018, pp. 86-87[19]). The government also sets a contracting goal for awarding contracts to small business concerns. The government also sets additional goals for awarding contracts to women-owned small businesses, small disadvantaged businesses, service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses, and small businesses located in Historically Underutilized Business Zones.

5.5. All potential bidders should have access to the same level of information

Providing public procurement information to the general public allows all potential bidders (including firms from other countries or from other regions within the country) to have access to the same information about government procurement opportunities at the same time. This enables wider participation in public procurement processes, which can support greater competition (OECD, 2019, p. 63[27]).

According to the Recommendation on Public Procurement, jurisdictions should ensure an adequate degree of transparency of the public procurement system in all stages of the procurement cycle. In particular, they should “allow free access, thorough an online portal, for all stakeholders, including potential domestic and foreign suppliers, civil society and the general public, to public procurement information”. Likewise, the Recommendation on Fighting Bid Rigging in Public Procurement provides that Adherents should maximise participation of potential bidders by encouraging procurement agencies to use electronic bidding systems, accessible to a broader group of bidders and less expensive.

The Checklist for Supporting the Implementation of the Recommendation on Public Procurement presents several actions to support jurisdictions’ implementation of the Recommendation by ensuring free access for all stakeholders to public procurement information, including: (i) creating an integrated information system providing up-to-date information for all interested parties; (ii) presenting information in a user-friendly and easily comprehensible manner for all interested parties; (iii) using an open data format that publishes information in an open and structured machined-readable format; (iv) using the same channels and timeframe for all interested parties; and (v) publishing the public procurement information free of cost (OECD, 2016, p. 7[3])

Distorting transparency and free access for all stakeholders to public procurement information can prevent competition being effective, as some players may be favoured over others. For instance, this would be the case if tender notices were only published in local newspapers or if they were accessible subject to the payment of a fee. Under such circumstances, incumbents and other local firms would be favoured to the detriment of SMEs and companies from other regions or countries, which could ultimately reduce the number of bidders, increase prices, and lower the quality of products and services.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

Australia uses a procurement information system, AusTender, to provide centralised publication of auctions, annual procurement plans, contract awards, as well as details of certain contracts and standing offers. Individuals can look up information on specific contracts, including the procuring entity, the procurement method, the contract value and period, the description of the contract, and supplier details (OECD, 2015, p. 6[28]).

In Costa Rica, the public procurement regulatory framework requires contracting authorities to use SICOP (Sistema Integrado de Compras Públicas, Integrated System of Public Procurement), which is the main source of information on public procurement. Since 2016, it is mandatory for all contracting authorities and bidders to publish relevant information on their procurement activities not only on their website but also through the e-procurement platform SICOP (OECD, 2020, p. 63[29]).

In the European Union, Section 2 of Chapter III of Title I of Directive 2014/24/EU on public procurement provides rules to ensure transparency and access to public procurement documents. For instance, the Tenders Electronic Daily (TED) provides free access to business opportunities from the EU, the European Economic Area and beyond in the 24 official EU languages. Procurement notices can be searched and sorted by country, region, and business sector (EU, 2023[30]).

Since 2009, Mexican public bodies use Compranet, a procurement information system built for publishing annual procurement programmes, tender procedures (including minutes of clarification meetings), contract awards history, and formal complaints. Individuals can also use the system to file complaints (OECD, 2016[31]).

In the United Kingdom, the Crown Commercial Service (responsible for managing the procurement of common goods and services for customer organisations in the public sector), developed a website to increase information on available low-value contract opportunities.5 This website enables suppliers to search for information about contracts worth over GBP 12 000 with the government and its agencies. Suppliers can use Contracts Finder to search for contract opportunities in different sectors, find out what is coming up in the future and look up details of previous tenders and contracts (OECD, 2018, p. 75[19]). There is also a dedicated website to find information on high value contracts, usually above GBP 138 760 including VAT.6

References

[32] ADB (2012), SME Development - Government Procurement and Inclusive Growth, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/30070/sme-development.pdf.

[21] Australian Government (2020), Indigenous Procurement Policy - December 2020, https://www.niaa.gov.au/resource-centre/indigenous-procurement-policy.

[25] CNMC (2023), CNMC Report on Draft Law to promote the social economy sector, https://www.cnmc.es/expedientes/ipncnmc01123.

[13] CNMC (2023), Guide on Public Procurement and Competition, In-house Procurement and Horizontal Cooperation, https://www.cnmc.es/expedientes/g-2020-01.

[26] CNMC (2021), Recommendations to the public authorities for an intervention in favour of market competition and an inclusive economic recovery, https://www.cnmc.es/sites/default/files/3812928_0.pdf.

[30] EU (2023), TED home, https://ted.europa.eu/TED/main/HomePage.do.

[23] Gourdon, J. (2018), “Mapping the OECD Government Procurement Taxonomy with International Best Practices: An Implementation to ASEAN Countries”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 216, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1bd4d59a-en.

[8] OECD (2021), OECD Roundtable on the Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities - Note by Latvia, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)22/en/pdf.

[18] OECD (2021), Roundtable on The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Note by Spain, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF/WD(2021)39/en/pdf.

[7] OECD (2021), “The promotion of competitive neutrality by competition authorities”, OECD Global Forum on Competition Background Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-promotion-of-competitive-neutrality-by-competition-authorities.htm.

[20] OECD (2021), The Promotion of Competitive Neutrality by Competition Authorities, Discussion Paper, https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/the-promotion-of-competitive-neutrality-by-competition-authorities-2021.pdf.

[15] OECD (2020), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Brazil, http://www.oecd.org/corporate/soe-review-brazil.htm.

[29] OECD (2020), Towards a new vision for Costa Rica’s Public Procurement System: Assessment of key challenges for the establishment of an action plan, https://www.oecd.org/costarica/Towards-a-new-vision-for-Costa-Rica's-public-procurement-system.pdf.

[14] OECD (2019), Enhancing the Use of Competitive Tendering in Costa Rica’s Public Procurement System, https://www.oecd.org/costarica/costa-rica-public-procurement-system.pdf.

[22] OECD (2019), Linking Indigenous Communities with Regional Development, OECD Rural Policy Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3203c082-en.

[11] OECD (2019), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Bulgaria, https://www.oecd.org/corporate/ca/Corporate-Governance-of-SOEs-in-Bulgaria.pdf.

[24] OECD (2019), Reforming Public Procurement: Progress in Implementing the 2015 OECD Recommendation, https://doi.org/10.1787/1de41738-en.

[27] OECD (2019), Reforming Public Procurement: Progress in Implementing the 2015 OECD Recommendation, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1de41738-en.

[10] OECD (2018), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Argentina, https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/Argentina-SOE-Review.pdf.

[19] OECD (2018), SMEs in Public Procurement: Practices and Strategies for Shared Benefits, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307476-en.

[3] OECD (2016), Checklist for Supporting the Implementation of the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement, OECD Publishing, https://www.oecd.org/governance/procurement/toolbox/search/checklist-implementation-oecd-recommendation.pdf.

[31] OECD (2016), Country case: Disclosure of information through the central procurement system Compranet in Mexico, https://www.oecd.org/governance/procurement/toolbox/search/disclosure-information-central-procurement-system-compranet.pdf.

[2] OECD (2016), Participation in Global Value Chains in Latin America: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policy, Working Party of the Trade Committee, https://one.oecd.org/document/TAD/TC/WP(2015)28/FINAL/En/pdf.

[28] OECD (2015), Compendium of Good Practices for Integrity in Public Procurement, https://one.oecd.org/document/GOV/PGC/ETH(2014)2/REV1/En/pdf.

[16] OECD (2015), OECD Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Colombia, https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/Colombia_SOE_Review.pdf.

[6] OECD (2012), Competitive Neutrality: National Practices, https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/50250966.pdf.

[4] Sigma (2016), “Defence Procurement”, Public Procurement Brief 23, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Public-Procurement-Policy-Brief-23-200117.pdf.

[12] Sigma (2016), In-house Procurement and Public/Public Co-operation, Public Procurement Brief 39, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Public-Procurement-Policy-Brief-39-200117.pdf.

[17] Sigma (2016), Procurement by Utilities, Public Procurement Brief 16, https://www.sigmaweb.org/publications/Public-Procurement-Policy-Brief-16-200117.pdf.

[9] WTO (2024), Overview of the Agreement on Government Procurement, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/gproc_e/gpa_overview_e.htm.

[1] WTO (2023), Rules of Origin, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/roi_e/roi_e.htm.

[5] WTO (2012), Agreement on Government Procurement (as amended on 30 March 2012), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/rev-gpr-94_01_e.htm.

Notes

← 1. https://www.mof.go.jp/about_mof/act/kokuji_tsuutatsu/tsuutatsu/TU-19871225-3015-11.htm (accessed on 18 April 2024).

← 2. According to the SOE Guidelines, “when SOEs engage in public procurement, whether as bidder or procurer, the procedures involved should be transparent, competitive and based on fair and objective selection criteria, promote supplier diversity and be safeguarded by appropriate standards of transparency. Generally, the activities of SOEs can be divided into two parts: activities that are for commercial sale or resale; and activities to fulfil a governmental purpose. In cases where an SOE is fulfilling a governmental purpose, or to the extent that a particular activity allows an SOE to fulfil such a purpose, the SOE should adopt government procurement procedures in line with best practices. Monopolies administered by SOEs should follow the same procurement rules applicable to the general government sector. SOEs as procurers should be encouraged to use open tenders, but be allowed a margin of appreciation on the right procurement method for their commercial activities if they compete with private sector companies in their market segment to ensure they are not subject to undue disadvantage” [OECD/LEGAL/0414].

← 3. According to the Recommendation on Public Procurement, “secondary policy objectives refers to any of a variety of objectives such as sustainable green growth, the development of small and medium-sized enterprises, innovation, standards for responsible business conduct or broader industrial policy objectives, which governments increasingly pursue through use of procurement as a policy lever, in addition to the primary procurement objective”.

← 4. Such preferences usually take one of the following forms: (i) bids from SMEs are discounted by a given margin (e.g. 5%) and the SME wins the bid if its offer is the lowest one; or (ii) the lowest offer from a non-SMEs bidder is handicapped by a given margin (e.g. 10%) and the competing SME win the bid if its offer is the lowest one (ADB, 2012[32]).

← 5. www.contractsfinder.service.gov.uk/Search (accessed on 29 September 2023).

← 6. https://www.gov.uk/find-tender (accessed on 29 September 2023).