Public service obligations are placed upon selected market actors in order to ensure to all consumers an appropriate access to essential services, which would not be provided by the market under commercial conditions. The assignment and delivery of public service obligations can, under certain circumstances, distort competition. This chapter presents a set of questions to guide the analysis, good practices and examples on how to implement the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality in public service obligations.

Competitive Neutrality Toolkit

7. Public Service Obligations

Abstract

Public service obligations (PSOs) are obligations placed upon selected market actors in order to ensure to all consumers an appropriate access to essential services, which would not be provided by the market under commercial conditions.1 The design and mechanisms for the implementation of PSOs can vary greatly amongst jurisdictions. However, such obligations are generally found in sectors such as postal services, transport, energy, and telecommunications.

The assignment and delivery of PSOs can, under certain circumstances, distort competition (Harker, Kreutzmann and Waddams, 2013[1]). For instance, when a market player is tasked with a PSO, this provision is supposed to be compensated by users and/or the state. However, how the compensation is determined, and its amount, can affect the level playing field and create challenges for competitive neutrality.

Moreover, it is a good practice that the scope of the PSO be clear, with a precise distinction between services included and excluded from it. This is particularly important when the market actor entrusted with a PSO also provides services open to competition. Once the scope is clearly defined, three aspects become of particular importance: (i) the selection of the public service provider (through an open competitive process or not); (ii) the privileges and powers attached to the public service (which may affect other providers, whether actual or potential); and (iii) how it is compensated (OECD, 2015[2]).

In line with these considerations, the Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality calls for jurisdictions to:

“Limit compensation for any public service obligation placed upon an enterprise, so that it is appropriate and proportionate to the value of the services” offered.

Identify in a transparent and specific manner the public service obligation placed upon an enterprise, and “impose high standards of transparency, account separation and disclosure” around costs and revenues, to reduce the risk of cross-subsidisation.

Establish independent oversight and monitoring, in order to “ensure that remuneration for public service obligations is calculated based on clear targets and objectives, and based on efficiently incurred costs, including capital costs”.

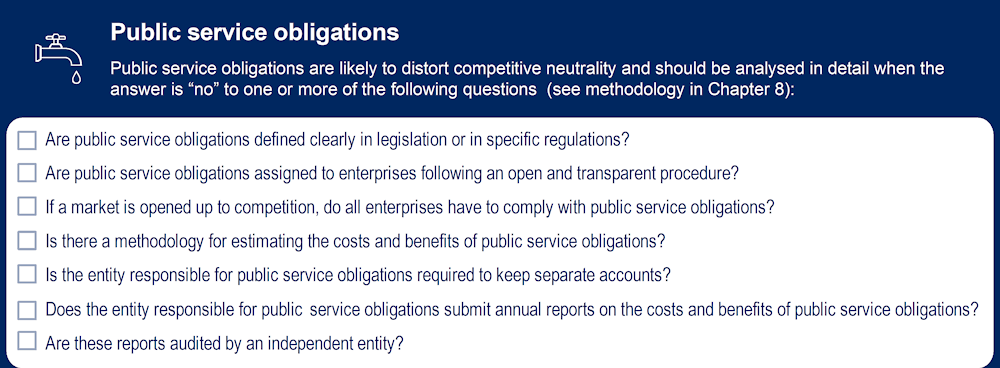

A set of questions to help identify policies that can potentially distort competitive neutrality is presented below. When a policy is not in line with at least one of the questions or good practice approaches, it has the potential to distort competition and should be analysed in detail. Chapter 8 sets out the main steps of the analysis.

Figure 7.1. Suggested questions to assess public service obligations

7.1. Public service obligations should not be automatically assigned to the incumbent (whether private or publicly owned) providing the service

This good practice approach addresses the need to ensure that no service provider is put at a competitive advantage or disadvantage due to the establishment of a PSO. Good practices across jurisdictions show that competitive neutrality is maintained also in the choice of the market player responsible for the PSO, as this comes with rights and responsibilities that can affect the level playing field. For instance, the PSO provider can benefit because its reputation/brand is enhanced by providing ubiquitous service and reaching more consumers, or it may gain economies of scope from supplying services that share some cost components (e.g. letters and small parcels if some parts of the network are shared). On the other hand, depending on its scope and design, the PSO can also represent a net cost for the provider.2

The application of effective and competitive selection rules, where interested public service operators are selected through an open, fair and transparent bidding process (OECD, 2015[3]), can safeguard the level playing field by avoiding an automatic assignation, while at the same time limit any abuse of the selection process. The PSO requirements, however, may be so onerous that competitive tenders may not attract many bidders or even any bidders at all. Recognising these difficulties, the legislation may allow the competent authorities to select award mechanisms other than open tenders, provided that they justify the underlying rationale. For instance, EU Regulation 1370/2007(Article 5) leaves open the possibility of direct awards for the provision of passenger transport services. By way of example, Box 7.1 below describes the framework for local transport in Italy.

Box 7.1. Award of local transport services provision in Italy

For the purposes of choosing the mechanism for awarding local transport service (in-house providing, direct awarding, competitive tendering or any other forms of awarding according to sectoral European legislation) and definition of the contractual relationship, the competent local authority is required to make a thorough assessment to justify the chosen awarding mechanism as well as the identified public service obligations and the economic compensation (if any, including the criteria for its calculation), in light of the principles and requirements of the EU legislation. Such an assessment shall be made in a written form in ad-hoc report by the local authority before the service award procedure starts, and published on the website of the local authority and ANAC, the anti-corruption agency responsible for the compliance with the public contracts code and transparency standards of all public bodies in Italy.

In particular, the selection of the awarding mechanism shall take into account the following elements:

the technical and economic characteristics of the service to be provided, including aspects relating to quality of service and infrastructure investments;

the state of public finances and the costs to the local authority and the users;

the expected outcomes if different alternatives of awarding were to be chosen, also with reference to comparable experiences of other local authorities;

the economic performance of the same service under previous regimes in terms of the effects on public finance, the quality of the service provided, the costs for the local authority and for users and the investments made;

the data and information that emerge from the periodic monitoring exercise envisaged under Art. 30 of the legislative decree.

Source: Italian Government (2022[4]), Legislative decree n. 201 of 23 December 2022, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/12/30/22G00210/sg, Italian Competition Authority (2021[5]), Proposal for pro-competitive reforms, https://www.agcm.it/dotcmsCustom/getDominoAttach?urlStr=192.168.14.10:8080/C12563290035806C/0/914911A1FF8A4336C12586A1004C2060/$File/AS1730.pdf.

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of this good practice approach:

In the EU, the legislation3 provides that “the responsible authority, when entrusting the provision of the service to the undertaking in question, has complied or commits to comply with the applicable Union rules in the area of public procurement. This includes any requirements of transparency, equal treatment and non-discrimination”. The selection of the PSO provider through a public procurement procedure is also addressed in the fourth Altmark criterion,4 which provides two alternatives5 to ensure that the choice of the provider is conducive to a compensation limited to the strict minimum (see also (Pesaresi et al., 2012[6])).

In Norway, since 1997 the Government has established aviation routes under PSO by means of public tenders, in order to guarantee services that competitive markets would not provide (e.g. remote regions). After the introduction of the invitation to tender mechanism, it was possible to ensure the same air services at a lower cost. This was mainly due to the incumbent carrier’s decision to lower its costs to be able to outplay potential rivals and win the tender (ICAO, 2003[7]). Although tenders for the provision of air services PSOs are now founded on Regulation (EEC) No 1008/2008,6 which organises the EU internal market for air services, individual states, such as Norway (European Economic Area member), have discretion to decide upon which routes are “essential air services” and on which authority should be responsible for the tenders (Bråthen and Eriksen, 2018[8]).

In Switzerland, universal service guarantees basic telecommunications services to all citizens in the country. The universal service licence is awarded through an open and transparent tender or, when it is evident from the outset that a public tender cannot be carried out under competitive conditions or it will not attract suitable bids, through a survey of interest among telecommunications service providers, as per Article 14, items 3 and 4 of the Telecommunications Act of 30 April 1997. In 2017, the Federal Communications Commission (ComCom) awarded the universal service licence for the period from 2018 to 2022 to Swisscom, which already held the universal licence expiring in 2017. ComCom carried out a survey among providers in the Swiss market who were in principle able to provide the universal service and identified that Swisscom was the only enterprise interested in providing the universal service (ComCom, 2017[9]). In 2022, ComCom extended the universal service licence for one year in light of the ongoing amendment to the regulation on the universal service for telecommunications (ComCom, 2022[10]). Once the amendment was adopted by the Federal Council (The Federal Council, 2022[11]), ComCom launched the procedure for granting the next universal service licence. In 2023, ComCom decided to re-award the licence to Swisscom for the period from 2024 to 2031. Again, a survey of interest among the largest providers on the Swiss market potentially capable of delivering the universal service indicated that Swisscom was the only one interested in fulfilling the universal service obligation for telecommunications (ComCom, 2023[12]).

In the UK, in order to implement the Broadband Universal Service Obligation (USO), Ofcom published in 2018 a request for expressions of interest in serving as Universal Service Provider for broadband.7 The call for expression of interest illustrated the process for the designation of the provider, clarifying both the objectives, the approach, and the expected compensation. In particular, Ofcom would implement an open and transparent process that would not exclude providers from participating, in line with the Universal Service Directive,8 following a direct designation approach. Once the prospective universal service providers submitted their expression of interest, Ofcom conducted an objective and transparent analysis to assess their ability to meet their obligations, as well as their plans for delivering the USO, against Ofcom’s objectives. These include ensuring that the USO is delivered as quickly as possible, that the USO specification is met, and that the cost of delivery is minimised. Ofcom then issued a public consultation on proposed designations before issuing a formal notice of designation.

7.2. Any public service obligation placed upon an enterprise should be identified in a transparent and specific manner

According to the Recommendation, the definition of the public service obligation should be specific and transparent. A clear definition of the services within the scope of the PSO helps the potential providers wishing to express their interest (see the previous good practice approach) assess the business case and, if applicable, submit a bid. In turn, meaningful bids contribute to the selection of the best placed public service provider and to keeping the necessary compensation to a minimum.

Importantly, it provides clarity to other market participants competing with the public service provider. It is sometimes the case that the definition of public service obligation overlaps with the services that, in certain markets, are provided by the incumbent under monopoly. A review of the PSO framework in the small-parcel delivery services sector in ASEAN has shown that unclear definitions and overlaps are not rare and result in regulatory uncertainty (OECD, 2021[13]). This uncertainty itself distorts the level playing field since competitors are not sure which services they can provide and they risk sanctions by the authorities, depending on how the legislation is interpreted.

Despite the benefits that clarity brings to new entrants, there is a risk that specifying the content of the PSO leads to inflexibility, especially when the PSO definition is specified in a law, which may not be amended easily or quickly. This is because what is considered PSO varies over time, responding to technological developments and to changing consumer needs. In the telecommunications sector, for example, broadband services have become part of PSO as access to the internet is now considered a basic need. At the same time, payphones used to be included in the definition of PSO but are no longer used as frequently as in the past (Harker, Kreutzmann and Waddams, 2013, p. 16[1]).

Examples

The following are meant to show selected examples of transparent and specific public service obligations:

Austria's universal postal services are defined in Section 6 of the Postal Market Act (PMA), in line with Directive 97/67/EC of 15 December 1997. The Postal Market Act also stipulates that universal services must be affordable, comply with defined quality and be available throughout the country. The Universal Service Operator (USO) may submit proposals for the further development of the definition of universal service. The PMA defines specific requirements in terms of coverage, delivery times, frequency and information to be provided to the regulator.

In Italy, the postal services included in the definition of universal service are set out in legislation.9 The definition has been amended over time. For instance, following advocacy by the Italian Competition Authority (AGCM), since 2017 the notification of fines and the transmission of judicial documents are no longer included in the universal service. An agreement between the state and the universal service provider covers more in detail the latter’s obligations, while the quality of service and the targets are defined by the sector regulator.

In Sweden, state-owned enterprises that have a public policy assignment, such as a public service obligation, have to clearly define it as well as the reason why the specific SOE performs it. Moreover, they have to set public policy targets that reflect the purpose of the assignment. As reported in (Government offices of Sweden, 2020[14]) “the assignment and its public benefit must therefore be made clear before the public policy targets are formulated”.

In the UK, legislation sets out the minimum telephony services to be provided, at an affordable price, to all citizens that request them. In 2018, the government introduced a broadband universal service obligation. The sector regulator implements these definitions through conditions imposed on the universal service providers and these conditions are publicly available.10

7.3. When a public service obligation is placed upon an enterprise, measures should be taken to avoid both over-compensation and under-compensation, in order not to unduly advantage a competitor

As for the assignment of the public service obligation, decisions regarding its compensation are also a crucial aspect to consider in order to maintain a level playing field. The Recommendation calls for jurisdictions to “ensure that compensation provided to Enterprises for fulfilling public service obligations is not used to cross-subsidise the offering of goods or services on another market” (also see good practice approach 7.5 below on ensuring accounting separation).

(OECD, 2015[15])shows that almost all countries compensate undertakings (public or private) which deliver public service obligations alongside their commercial activities. Depending on the jurisdiction, the type of public service and the entity delivering such services compensation methods may vary. These range from direct transfers, capital grants, reimbursements (ex-post and ex-ante), and budget appropriations, to state aids/subsidies.

If an enterprise, public or private, is overcompensated for the fulfilment of a PSO, this can result in an indirect subsidy for its commercial activities that are in competition with other market actors. The enterprise may be able to use the PSO compensation to cross-subsidise its commercial activities, and for instance exclude competitors by pricing below cost. This was at the centre of the EU case against Deutsche Post, which was found to have engaged in predatory pricing in the market for business parcel services, which was open to competition (OECD, 2018, p. 15[16]). Challenges for competitive neutrality can also arise due to under-compensation, as this can jeopardise the enterprise’s ability to effectively compete with rivals in commercial activities and ultimately affect its overall viability. In a review of competitive neutrality in the market for small parcel delivery services in ASEAN, the OECD found that under-compensation can be problematic for competitive neutrality and recommended the removal of this distortion (OECD, 2021[13]).

Examples

The following examples illustrate measures to avoid over-compensation and under-compensation:

The EU has a framework in place to determine adequate compensation11 for public-service obligations, embodied in the 2012 Communication from the Commission.12 The Communication builds on and aims at clarifying the 2003 Altmark judgement,13 in which the Court of Justice set four cumulative criteria to be met for a public service compensation not to constitute (unlawful) State aid:

The recipient firm must have public-service obligations and the obligations must be clearly defined.

The parameters for calculating the compensation must be objective, transparent and established in advance.

Compensation cannot exceed what is necessary to cover all or part of the costs incurred in the discharge of the public-service obligations, taking into account the relevant receipts and a reasonable profit.

Where the firm is not chosen pursuant to a public procurement procedure which would allow for the selection of the tenderer capable of providing those services at the lowest cost to the community, the level of compensation for the operator of public-service obligations must be determined on the basis of an analysis of the costs of a typical well-run company.

In cases where at least one of these “Altmark conditions” is not fulfilled, the public-service compensation will be examined under state aid rules.14

In its Decision 542/15.05.2013 the Bulgarian Commission on Protection of Competition (CPC) issued an opinion regarding the Ordinance for the transportation of passengers and the conditions for travelling by trolley bus (electric bus that draws power from overhead wires) in the town of Vratsa. The ordinance obliges the trolley bus transportation companies to offer additional discounts on season tickets for certain categories of passengers. In return for this obligation, the companies received compensation from the municipal budget, calculated on the basis of the issued tickets. The authority argued that the granting of a privilege to a company to compensate it for a legally imposed obligation is not a deviation from the principle of competitive neutrality, provided that there is no overcompensation (OECD, 2015[15]).

The Spanish National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) issued recommendations about the public tender to select the provider of the PSO maritime connection between Ceuta and Algeciras. The CNMC highlighted the need for a better design of the tender as to the value, procedure, capacity requirements and technical terms and conditions, in order to promote competition (since 2011, the same shipping company won the contract as a single bidder). Due to the lack of effective competition in the bidding process, the CNMC pointed out that the economic compensation given to the service provider should comply with the Altmark criteria (see example above) and other State aid rules (CNMC, 2018[17]).

7.4. Compensation should be based on criteria that are objective, transparent and established in advance

To avoid over or under-compensation, as outlined by the previous good practice approach, it is important to estimate the compensation based on the “correct” costs and benefits of the public service obligation. Good practices show that compensation only covers the costs incurred by the public service provider, net of any benefits it may gain from universal service provision. For instance, these benefits could include greater brand recognition because it supplies its services everywhere across the country.

Regardless of the chosen method for PSO compensation, clear and transparent parameters/rules are generally in place to ensure that compensation is overall fair and allows for services to be delivered, and to guarantee sufficient accountability of the calculation of the PSO compensation itself. As explained in (OECD, 2015[15]), standards and benchmarks for PSO compensation are generally stipulated by law or regulation but can also be further clarified by case law. This means that the public service provider cannot arbitrarily select a methodology that could potentially result in higher costs and therefore higher compensation, for instance by allocating artificially a higher share of common costs to public service provision.

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions have implemented this good practice approach:

In Austria, most government businesses providing public services set prices to meet universal service obligations according to sector regulators’ requirements (e.g. postal and gas sectors); sector regulators are also responsible for determining compensation amounts (OECD, 2012[18]). See Box 7.3 on universal service obligations in the Austrian post services.

In the Netherlands, a price cap applies to the universal-service obligations (USO) for both letters and parcels, which is intended to limit the return on sales to a maximum of 10%. For this purpose, the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets (ACM) has defined a basic tariff, called the tariff headroom, which is updated annually, taking into account – among other considerations – the general consumer price index and USO volumes. PostNL is allowed to set its tariffs within this headroom. This price regulation ensures that PostNL is sufficiently compensated with a market-determined rate of return for its USO (OECD, 2021[13]).

In Türkiye, companies which provide public services are compensated according to duty-loss (according to Decree law no. 233) which allows the Treasury to compensate any duty losses up to 110% of losses incurred (OECD, 2012[18]).

Box 7.2. Universal service obligation compensation in Italy: the case of Poste Italiane

Italy periodically grants compensation to Poste Italiane (PI), for the fulfilment of its universal service obligation (USO). The compensation mechanism comprises the following steps, as illustrated in the 2020 EC decision approving State compensation:

Step 1: the Italian government determines the maximum amount of public financing it wants to grant to PI per year (currently laid down in Law n. 190/2014 of 23 December 2014, the “Stability Law”).

Step 2: PI calculates the net cost of the USO by using the net avoided cost (hereinafter "NAC") methodology and submits its calculations to the national regulatory authority (NRA) for verification.

Step 3: the NRA (the Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni, hereinafter "AGCOM") performs the ex-post verification (see previous step) on the net cost calculated by PI to determine the burden of the USO using the NAC methodology.

Step 4: in line with the requirements of the Postal Services Directive, AGCOM then assesses whether the net cost of the USO represents an unfair financial burden which is excessive for PI to bear.

Step 5: if the net cost of the USO is considered an unfair financial burden, the public financing can be granted to the extent that it does not exceed the net cost for USO as determined by AGCOM.

In particular, the calculation of the net cost of the USO using the NAC methodology (step 2) requires the definition of a factual scenario, and a counterfactual one, representing what PI would do without the obligation to provide the universal service. Revenues and costs in both scenarios are calculated. This allows a conservative estimation of the NAC before intangibles, which corresponds to the difference in profit between the factual and counterfactual scenario.

The NAC is then calculated after deducting the intangibles, i.e. “those benefits enjoyed by a provider due to its Universal Service Provider status, or, more generally, to the provision of other services, which entail an improvement of its profitability.1

Note: 1. These can include economies of scale and scope, brand value and demand complementarities, enhanced advertising effect, demand effects due to the VAT exemption, ubiquity and network advantages, lower transaction costs and better customer acquisition due to uniform price.

Source: European Commission (2020[19]), Decision of 1.12.2020, Case SA.55270 – State compensations granted to Poste Italiane SpA for the delivery of the universal postal service for the period 2020‑2024, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/202110/288817_2252302_118_2.pdf.

Box 7.3. Universal service obligation compensation in Austria: the case of Austrian Post

Under Article 12 of the Postal Market Act (PMA), Austrian Post is defined as a Universal Service Provider (USP), subject to review every five years.

The demonstrably accrued net costs of the universal services are those that cannot be recovered despite economic management and represent a disproportionate financial burden for the universal service operator. Such costs must be reimbursed to the universal service operator upon request within one year of the period for which the net costs were incurred.

A disproportionate financial burden in relation to universal services would exist if the net cost exceeded 2% of the total costs of the USO. The net costs above the 2% threshold must be reimbursed.

If the USO applies for such compensation, the sector regulator (PCK) must establish and administer a universal service fund to which all licensed postal services with an annual turnover of more than EUR 1 million have to contribute according to their market shares (excluding the USO's turnover from the US). Finally, PCK has to determine the shares of those who are obliged to contribute by means of a notification and inform the companies concerned of its calculation and the amount they have to contribute.

Article 15 of the PMA then describes how net costs are calculated. The estimation must be based on the costs of specific services that cannot be recovered through normal business operations and the costs to groups of users who would not receive a service in the absence of the obligation. Key elements to be considered include the costs that could be avoided by the USP in the absence of the obligations and the intangible benefits that the operator receives from the provision of the US.

For the time being, no application for compensation has been submitted.

Source: Austrian Government (2024[20]), Postal Market Act, https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=20006582 and information provided by the Austrian Federal Competition Authority (BWB).

7.5. Accounting separation and reporting requirements should be established

The Recommendation recommends that jurisdictions “impose high standards of transparency, account separation and disclosure on Enterprises with public service obligations around their cost and revenue structures”. In order to calculate the optimal level of compensation for the fulfilment of public service obligations, any costs and revenues related to the fulfilment of public-service obligations are to be clearly identified and disclosed. For this purpose, accounting separation is crucial to ensure that activities reserved for the PSO provider do not provide a channel for cross-subsidisation, which may result in market distortions (OECD, 2021[13]).

When a public service provider uses cross-subsidisation practices to fund its commercial activities, thus obtaining an advantage over its competitors, it negatively affects competitive neutrality. Therefore, in order to limit this risk, and to ensure transparency regarding funds received for the PSO, good practices show that accounts for the PSO and for commercial activities are kept separate.

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions establish accounting separation and reporting requirements:

In Australia, the Australian Government Competitive Neutrality Guidelines for Managers highlight that “there needs to be organisational separation (either accounting or legal) of commercial and non-commercial activities. It is necessary to separate business activities from other government activities to ensure that Budget-funded activities do not effectively cross-subsidise commercial operations. Cross-subsidisation of these activities is undesirable, as it is not a transparent use of government funds and places private sector competitors at a disadvantage” (Australian Government, 2004[21]).

In the land transport sector in Poland, compensation for public service obligations is regulated by the Act of 16 December 2010 on Public Transport.15 If the carriers conduct other business activity in addition to providing services in the field of public transport, it is obliged to keep separate accounts for both areas of activity (OECD, 2015[15]).

In Spain, Article 26 of the Law No. 43/2010 (Postal Act) establishes the obligation of the designated postal operator to use analytical accounting that make it possible to separate universal service obligation (USO) accounts from those of other services. Moreover, the operator must submit a calculation of the net cost of the USO for validation each financial year. The National Markets and Competition Commission (CNMC) has the power to verify the correct allocation of costs and revenues in the operator’s accounts annually (OECD, 2021[13]).

Box 7.4. OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises

The OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises are recommendations to governments on how to ensure that SOEs operate efficiently, transparently, and in an accountable manner. They cover the following areas: 1) rationales for state ownership; 2) the state’s role as an owner; 3) SOEs in the marketplace; 4) equitable treatment of shareholders and other investors; 5) stakeholder relations and responsible business practices; 6) disclosure and transparency; and 7) responsibilities of SOE boards. The Guidelines underwent a new revision, finalised in May 2024, and now include a new chapter on sustainability.

Concerning public service obligations, the Guidelines recognise the important role of SOEs in pursuing public policy objectives and address situations when SOEs both engage in economic activities and pursue public policy objectives. Consistently with the OECD Recommendation on Competitive Neutrality, the Guidelines recommend “ensuring that compensation is not used for cross-subsidisation” and call for maintaining “high standards of transparency and disclosure regarding their costs and revenue”. More specifically, they note that “[i]t is important that compensation provided to SOEs be calibrated to the net costs of fulfilling well-defined public service obligations and not be used to offset any financial or operational inefficiencies. Compensation should never be used for financing SOEs’ economic activities other than public service obligations, including in other markets, or for cross-subsidisation of other SOEs or private companies”.

Source: OECD/LEGAL/0414.

7.6. Independent oversight and monitoring should be established (or maintained)

In order to ensure that competitive neutrality is maintained, it is important that the optimal level of compensation for the fulfilment of public service obligations, established and used according to a clear and transparent methodology (see good practice approaches 7.3 and 7.4), is monitored and controlled by an independent party, as indicated in the Recommendation (“Establish or maintain independent oversight and monitoring […]”).

Independent oversight is necessary to ensure that over/under compensation are avoided, and that funds for the PSO are not used to cross-subsidise services outside the scope of the PSO and distort the level playing field. In the absence of external review of the estimated net cost of PSOs, there would be a risk of the PSO provider inflating those net costs in an attempt to cross-subsidise.

In practice, this means that a designated entity has an oversight and audit role of the estimates produced by the public service provider itself. From an institutional point of view, the sector regulator may have responsibilities for reviewing the estimates and assessing if they indeed reflect efficiently incurred costs. At the same time, if the jurisdiction has in place a broader framework for the control of state support measures, the compensation may be subject to this framework too, as is the case in the European Union (see Hungary example below).

Examples

The following examples show how different jurisdictions have implemented independent oversight and monitoring:

In Hungary, the State Aid Monitoring Office (SAMO) ensures that compensation for public service provision is adequate and according to EU rules on State Aid. If the state/municipality intends to compensate a public service provider to fulfil a public service obligation, it should notify their aid plans to SAMO (according to Government Decree 37/2011, III. 22) and SAMO will decide on a preliminary opinion. Public service providers should co-operate and facilitate the controlling procedures. Furthermore, they have to prepare a report periodically. In certain cases, beneficiaries must submit a report on the fulfilment of the goals defined in the contract and a detailed financial report that should be approved by an external auditor (OECD, 2015[15]).

In Switzerland, compensation for entities entrusted with public service obligations is determined through sector specific laws, and calculations are assessed by sector regulators (e.g. postal, telecom, transportation and health sectors) (OECD, 2015[15]). However, at national level compensation only takes place in the railway sector.

References

[21] Australian Government (2004), Competitive Neutrality Guidelines for Managers, https://www.pc.gov.au/about/core-functions/competitive-neutrality/2004-competitive-neutrality-guidelines-for-managers.pdf.

[20] Austrian Government (2024), Postal Market Act, https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=Bundesnormen&Gesetzesnummer=20006582.

[8] Bråthen and S. Eriksen (2018), “Regional aviation and the PSO system – Level of Service and social efficiency”, Journal of Air Transport Management, Vol. 69, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S096969971630223X.

[17] CNMC (2018), Assessment on PSO maritime transport services between Ceuta and Algeciras, https://www.cnmc.es/sites/default/files/2247493_8.pdf.

[12] ComCom (2023), Swisscom to retain universal service obligation, https://www.comcom.admin.ch/comcom/en/Homepage/documentation/media-information.msg-id-95118.html.

[10] ComCom (2022), ComCom extends universal service licence for one year, https://www.comcom.admin.ch/comcom/en/Homepage/documentation/media-information.msg-id-88887.html.

[9] ComCom (2017), ComCom awards telecoms universal service licence to Swisscom, https://www.bakom.admin.ch/bakom/en/homepage/ofcom/ofcom-s-information/press-releases-nsb.msg-id-66782.html.

[22] Ennis, S. (2023), The Natural Monopoly Paradox: Incumbent Inefficiency and Entry, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4364914.

[19] European Commission (2020), Decision of 1.12.2020, Case SA.55270 - State compensations granted to Poste Italiane SpA for the of the universal postal service for the period 2020-2024, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/cases1/202110/288817_2252302_118_2.pdf.

[14] Government offices of Sweden (2020), Annual report for state-owned enterprises 2020, https://www.government.se/reports/2021/09/annual-report-for-state-owned-enterprises-2020/.

[1] Harker, M., A. Kreutzmann and C. Waddams (2013), “Public service obligations and competition”, Final report for CERRE, https://cerre.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/130318_CERRE_PSOCompetition_Final_0.pdf.

[7] ICAO (2003), Operating subsidised regional routes in a liberalized market as exemplified by the Norwegian experience, https://www.icao.int/sustainability/CaseStudies/StatesReplies/Norway_En.pdf.

[5] Italian Competition Authority (2021), Proposal for pro-competitive reforms, https://www.agcm.it/dotcmsCustom/getDominoAttach?urlStr=192.168.14.10:8080/C12563290035806C/0/914911A1FF8A4336C12586A1004C2060/$File/AS1730.pdf.

[4] Italian Government (2022), Legislative decree n. 201 of 23 December 2022, https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/12/30/22G00210/sg.

[13] OECD (2021), OECD Competitive Neutrality Reviews: Small-package delivery services in ASEAN, http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/oecd-competitive-neutrality-reviews-asean-2021.pdf.

[16] OECD (2018), Competition Law and State-Owned Enterprises, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP/GF(2018)10/en/pdf.

[15] OECD (2015), Discussion on Competitive Neutrality, Note by the Secretariat, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2015)8/FINAL/en/pdf.

[3] OECD (2015), “Inventory of competitive neutrality distortions and measures”, DAF/COMP(2015)8/FINAL, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2015)8/FINAL/en/pdf.

[2] OECD (2015), “Roundtable on competition neutrality - Issues paper”, DAF/COMP(2015)5, https://one.oecd.org/document/DAF/COMP(2015)5/En/pdf.

[18] OECD (2012), Competitive Neutrality: Maintaining a Level Playing Field between Public and Private Business, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264178953-en.

[6] Pesaresi et al. (2012), The SGEI Communication, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/publications/cpn/2012_1_10_en.pdf.

[11] The Federal Council (2022), Faster internet for universal service, https://www.bakom.admin.ch/bakom/en/homepage/ofcom/ofcom-s-information/press-releases-nsb.msg-id-92207.html.

Notes

← 1. Some countries may not need to require the provision of universal service, if market forces are sufficient to ensure delivery at affordable prices. For instance, France does not designate any longer a universal service provider in the telecommunications market. See www.arcep.fr/la-regulation/grands-dossiers-reseaux-fixes/le-service-universel-des-communications-electroniques.html (accessed on 14 April 2023).

← 2. There may be unintended consequences from placing a PSO on an undertaking and compensating it for its provision. For instance, the residual market demand may not be sufficient for a competitor to be commercially viable. Moreover, as noted by (Ennis, 2023[22]), under certain conditions the entry of a competitor reduces the total costs of delivering services in certain infrastructure and delivery products. This result has implications for public policy and the PSO: “those postal incumbents that have the lowest volumes and that are increasingly facing the most serious financial challenges may be exactly the postal services where subsidies are inappropriate and competition would have the most beneficial effects.” (p. 34).

← 3. 2011 Communication from the Commission on the EU framework for State aid in the form of public service compensation, 2012/C 8/03 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012XC0111(03)&from=EN. Under EU legislation, public service compensation is assessed under the State Aid framework and it “will be considered compatible with the internal market on the basis of Article 106(2) of the Treaty only” when assigned following public procurement rules.

← 4. Case C-280/00, Judgment of 24 July 2003, Altmark Trans GmbH and Regierungspräsidium Magdeburg v Nahverkehrsgesellschaft Altmark GmbH, and Oberbundesanwalt beim Bundesverwaltungsgericht, https://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?language=en&num=C-280/00.

← 5. The two alternatives are: (i) selection of the public service provider by a public procurement procedure and (ii) if there is no public procurement procedure, a benchmarking exercise with an efficient undertaking (details of how this exercise is performed are provided in the 2012 Communication from the Commission on the application of the European Union State aid rules to compensation granted for the provision of services of general economic interest, para. 69 et seq., https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012XC0111(02)).

← 6. The Regulation is applicable to third countries where it has been incorporated into agreements concluded with the EU. At present, this is the case of the EEA Agreement (as regards Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein) and the EU-Switzerland Air Transport Agreement (OJ L 114, of 30.4.2002).

← 8. Directive 2002/22/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 March 2002 on universal service and users' rights relating to electronic communications networks and services, as amended by Directive 2009/136/EC. This legislation has been subsequently replaced by Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 establishing the European Electronic Communications Code (Recast).

← 9. The definition is provided by Art. 2 of Legislative Decree 22 July 1999 n.261, as amended. Law 4 August 2017 n. 124 removed the notification of sanctions and of judicial documents from the scope of universal service. The agreement between the state and the universal service provider is available at www.mise.gov.it/images/stories/documenti/Contratto_di_programma_firmato_digitalmente-2020.pdf.

← 10. See the relevant legislation and conditions imposed on BT and KCOM at www.ofcom.org.uk/phones-telecoms-and-internet/information-for-industry/telecoms-competition-regulation/general-conditions-of-entitlement/universal-service-obligation (accessed on 14 April 2023).

← 11. Within the EU State Aid framework, in the context of the assessment to determine if a public service compensation constitutes State aid or not.

← 12. Communication from the Commission — European Union framework for State aid in the form of public service compensation, 11/01/2012, 2012/C 8/03.

← 13. Case C-280/00, Judgment of 24 July 2003, Altmark Trans GmbH and Regierungspräsidium Magdeburg v Nahverkehrsgesellschaft Altmark GmbH, and Oberbundesanwalt beim Bundesverwaltungsgericht, ECLI:EU:C:2003:415.

← 14. The measure will be subject to the standard EU state aid procedures in order to determine if it constitutes unlawful aid. For more details see https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-04/state_aid_procedures_factsheet_en.pdf.

← 15. Journal of Laws of 2011 No. 5, item 13.