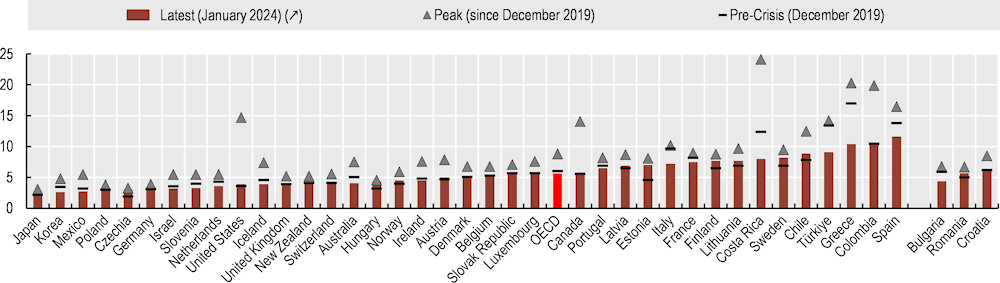

In addition to putting a strain on household and public finances, unemployment can have a demoralising effect on individuals and diminish their career prospects. The COVID‑19 pandemic of 2020/21 led to record unemployment rates across the OECD. Even if unemployment rates are below (or close to) pre‑crisis levels in many countries, over 5.5% of the active working-age population was unemployed in January 2024 on average across the OECD (Figure 5.4).

The rates in Japan, Korea, Mexico and Poland are below 3%, while many countries cluster around 4%. Unemployment is highest at two‑digit levels in Colombia, Greece and Spain. Nevertheless, these countries have seen impressive falls in unemployment since the peak in spring 2020 during the COVID‑19 crisis. The decline in unemployment has also been substantial in Canada and the United States.

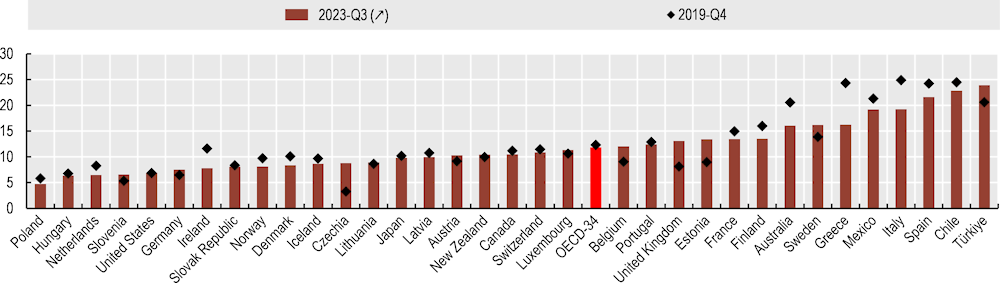

A broader measure of labour market slack is “broad labour underutilisation”, which enables quantification of the degree to which available labour resources are either not utilised (i.e. joblessness) or underutilised, such as people who wish to and are available to work more hours than they usually do and are working part-time (i.e. underemployment). On average across OECD countries, more than one in eight persons (12%) of working-age is “underutilised” (Figure 5.5). The share is lowest in Poland at below 5% and is highest in Chile, Spain and Türkiye at above 20%. Compared to the last quarter of 2019 (before the COVID‑19 crisis), 2023 rates are 4 percentage points higher in Estonia and 5 percentage points higher in Czechia and the United Kingdom in the third quarter of 2023. Over the same period, rates particularly decreased in Australia and Italy (by 4 and 5 percentage points) and Greece (8 percentage points).

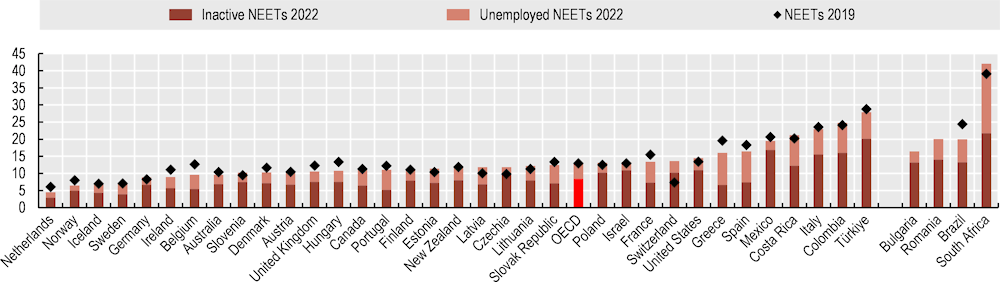

Unemployment as well as inactivity is not uncommon among young people. The share of 15‑to‑29‑year‑olds who were neither employed, nor in education or training (NEET) in 2022 reached 12.5% on average across OECD countries, almost 1 percentage point lower than in 2019 at 13.3% (Figure 5.6). A disaggregation of NEETs into those actively seeking a job (unemployed NEETs) and those who are not (inactive NEETs) shows that in most countries the majority of NEETs are not looking for work. Lower skills make young people particularly vulnerable to unemployment and inactivity, as young people with no more than lower-secondary education are three times more likely to be NEET than those with a university-level degree.