This chapter presents a cross-cutting analysis of agriculture policy trends based on information and support estimates gathered for 54 countries covered in OECD’s Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2023. It provides an overview of recent economic and market developments that influence the context for the implementation of agricultural policies. It then outlines the implications on policies of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and of inflationary pressures more generally, with an overview of policy responses by governments to help agricultural producers and consumers cope with these challenges. The third section presents developments in other agricultural policies in 2022-23, as well as an analysis of developments in the level and structure of support to agriculture. Key recommendations for reforms to better address public objectives conclude this chapter.

Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2023

2. Developments in agricultural policy and support

Abstract

For the past several years, agricultural have been shaped by multiple crises. Policy makers were forced to respond first to the pandemic caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (henceforth referred to as the COVID-19 pandemic), which initially disrupted production and later snarled supply chains. As the effects of the pandemic faded, Russia’s1 illegal and unjustified invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 roiled markets for specific agricultural inputs and outputs.

Alongside these acute consequences of war and pandemic, the effects of climate change were felt in the increased prevalence of natural disasters such as floods, drought and storms in many of the countries in this report. African Swine Fever and Avian Flu are two reoccurring biosecurity threats that also strongly affected global markets in 2022.

All of this taken together has put the stability and resilience of the sector, the predictability of trade, food security, and the stability of markets on the top of the policy agenda. These issues added to (and competed with) existing priorities to improve the sustainability of food systems and mitigate their effects on climate change. As this chapter will describe, policymakers took action to try to help the sector absorb and recover from these events in the short run and undertook steps to address the impacts of future shocks. Temporary export bans, tariff reductions (or increases) and other measures were used with the intention of securing domestic food supplies and managing market disruptions. Overall, these and other actions taken by policy makers increased total support to producers.

Agriculture policy in 2022 was also made in the context of a global economy weighed by value chain disruptions and high energy prices. GDP growth both globally and in the OECD area dropped by close to half in 2022, as did real global trade. These rates remained above those observed prior to the pandemic, but fell short of earlier expectations after the contractions in 2020. Moreover, average inflation in the OECD area climbed to more than 9%.

This chapter first presents the general economic and market context in which agricultural policies evolved over 2022. The second section provides an overview of policies responding to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine and its consequences for agricultural input and output markets. This is complemented by a discussion of other agricultural policy developments in 2022 and early 2023, while a fourth section presents and analyses developments in agricultural support. The chapter concludes by providing an overall assessment of the use of support against the main policy objectives for the agricultural sector.

Key economic and market developments

Conditions in agricultural markets are strongly influenced by macro-economic factors such as economic growth (measured by gross domestic product, GDP), which drives demand for agricultural and food products, as well as by prices for crude oil, natural gas and other energy sources that underpin many production inputs in agriculture, notably fuel, chemicals and fertiliser. Energy prices also affect the demand for cereals, sugar crops and oilseeds through the market for biofuels produced from these feedstocks.

Global GDP, which had begun to recover from its 3% contraction following the COVID-19 pandemic and grew by almost 6% in 2021, saw its growth reduced to just over 3% in 2022 (Table 2.1). Across the OECD, deceleration was most significant in fast-growing economies, including Chile (2.5%, down from 11.9% in 2021), Estonia (-1.7% compared to +8%) and Türkiye (5.6% after 11.4%). Across the euro area, growth remained comparatively robust at 3.5%, down from 5.2% in 2021. While output exceeded pre-pandemic levels in most countries, GDP remained below 2019 levels in Spain, Japan, Mexico and the United Kingdom.

Labour markets were a bright spot in the overall economic picture. Unemployment rates that had peaked in 2020 fell over the course of 2021 and 2022 to average 5% across the OECD area, the lowest in more than 40 years. At the same time, shortages of qualified workers have sometimes dampened economic growth.

Prices rose strongly over the same period and inflation reached an average 9.3% in 2022, a level not seen for more than 30 years. Energy and food prices strongly contributed to such high inflation rates (see below).

Emerging economies were also affected. Growth in the countries covered by this report fell significantly relative to their rebounds in 2021, but in most cases remained close to or above average growth rates seen prior to the pandemic. The stark and obvious exception is Ukraine, where the war has wiped out close to 30% of its economic output.

Global trade grew by 5% year on year, a deceleration relative to the 10% growth in 2021 but still slightly higher than average pre-pandemic growth rates.

Table 2.1. Key economic indicators

|

|

Average 2010-19 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Real GDP growth1 |

|

|

|

|

|

World2 |

3.1 |

-3.1 |

6.1 |

3.3 |

|

OECD2 |

1.8 |

-4.4 |

5.7 |

3.0 |

|

United States |

2.0 |

-2.8 |

5.9 |

2.1 |

|

Euro area |

1.2 |

-6.2 |

5.2 |

3.5 |

|

Japan |

0.8 |

-4.3 |

2.2 |

1.0 |

|

Non-OECD2 |

4.3 |

-2.0 |

6.5 |

3.7 |

|

Argentina |

0.3 |

-9.9 |

10.4 |

5.2 |

|

Brazil |

0.7 |

-3.6 |

5.3 |

3.0 |

|

China |

6.6 |

2.2 |

8.4 |

3.0 |

|

India3 |

5.8 |

-5.8 |

9.1 |

7.2 |

|

Indonesia |

4.8 |

-2.1 |

3.7 |

5.3 |

|

South Africa |

1.4 |

-6.3 |

4.9 |

2.0 |

|

Ukraine |

.. |

-3.8 |

3.4 |

-29.1 |

|

OECD area |

|

|

|

|

|

Unemployment rate4 |

7.0 |

7.2 |

6.2 |

5.0 |

|

Inflation1,5 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

3.8 |

9.3 |

|

World real trade growth1 |

3.5 |

-8.0 |

10.4 |

5.0 |

1. Per cent; last three columns show the change over a year earlier.

2. Moving nominal GDP weights, using purchasing power parities.

3. Fiscal year.

4. Per cent of labour force.

5. Personal consumption expenditures deflator.

Source: OECD (2023), Economic Outlook N°113 - June 2023, OECD Statistics Database, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?lang=en&SubSessionId=943670ea-b9e0-4eb4-9447-2347c99584f5&themetreeid=4.

Inflation was driven notably by prices for energy and food. Energy prices, which had doubled already in 2021 relative to the comparatively low levels in 2020, rose by a further 64% year on year in 2022 and began to fall only in the last third of the year (Figure 2.1). Sanctions against Russia following its war against Ukraine, Russia’s decision to suspend gas deliveries to EU Member States and the continued relatively robust economic growth have contributed to lower supplies and growing demand for primary energy sources. Average prices for natural gas doubled again in 2022, after a 253% increase in 2021. Crude oil also increased by almost 50% year on year. Prices for both declined in early 2023, approaching their pre-pandemic levels.

Fertiliser prices, which had almost doubled in 2021, rose further after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and averaged 74% higher in 2022 than in 2021, peaking only in November 2022, before slowly retreating. The run-up in fertiliser prices was driven not only by higher energy prices but also by the high pre-war market share of exports from Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. Potash prices rose by 166% year on year, as Russia and Belarus alone had accounted for more than a third of global potash exports in 2018-20.

Food prices had been on the rise before the war, driven by stronger demand due to the rebounding economic activities post-COVID-19, harvest shortfalls in some major producing countries and higher input costs. On average, food prices further increased by 14% in 2022, as lower exports from Ukraine and Russia reduced supply and increased uncertainties on markets already affected by rising energy and fertiliser costs. This increase, while significant, remains lower than the increase observed in 2021 and significantly less pronounced than those for energy or fertilisers, although the extent of price increases differed by commodity (FAO, 2022[1]).

Figure 2.1. Commodity world price indices, 2007 to 2023

Note: The top part of the graph relates to the left scale, while the bottom part of the graph to the right scale.

Source: IMF (2023), Commodity Market Review, for all commodities, food and energy indices (base year: 2016), www.imf.org/external/np/res/commod/index.aspx; FAO (2023), FAO Food Price Index dataset, for meat, dairy and cereal indices (base period: 2014-16), www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en.

The growth rate of meat production slowed from over 4% in 2021 to 1% in 2022. Higher pig meat production in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) was a factor for continued growth, as the sector continues to recover from the African Swine Fever (ASF) disease. Production levels in North and South America remained relatively stable, while Europe and Oceania observed a decline in meat output. Rising input costs, the prevalence of animal diseases, and unfavourable weather conditions adversely affected producer margins and disrupted meat production in various parts of the world. This, together with growing import demand, has led to average meat prices rising by more than 10% in 2022, although prices started to decline in the second half of the year as import demand slowed, and in December were only slightly higher than a year earlier.

World milk production grew by just 0.6% in 2022. Output increased notably in India, Pakistan and China, offset by contractions in Ukraine due to the ongoing war, and in several other countries due to extreme weather events, shortages in labour supply and higher input costs. World dairy prices further increased and peaked in June before declining due to lower import demand. On average, dairy prices in 2022 were almost 20% higher than in 2021.

Recovering demand for vegetable oils and rising feed demand for oilseed meals notably in China were met by a 7% increase in oilseed production in 2022/23 compared to the previous season.2 Record world soybean production was driven mainly by strong output growth in Brazil, while rapeseed production growth factors included its recovery from the very low preceding harvest in Canada and increased output also in Australia and the European Union, among others. In contrast, lower global sunflower seed production is caused mainly by disrupted production in Ukraine. World oilseed prices, already high in 2021, increased sharply in early 2022, peaking at record levels in March before declining by more than 40% towards the end of the year. On average, oilseed prices in 2022 were 13% higher than in 2021 as stock-to-use ratios remained low compared to historical levels. Prices for vegetable oils and for meals and cakes rose slightly more strongly, by 14% and 15% respectively.

Global cereal production was down by almost 2% in 2022/23, as lower production of coarse grains and rice more than offset a slight increase in global wheat output. Reductions in coarse grains were mainly driven by declining maize harvests in the European Union, Ukraine and the United States, and lower sorghum production in the United States, more than offsetting higher global barley production. Production in the European Union and the United States was down also for rice, but the global decline was mainly due to weather conditions in southern Asia, while other parts of Asia and Africa saw some increased output. A 40% drop in Ukraine’s wheat output and declining production also in several other countries were more than offset by significant recovery from the previous harvest in Canada and a second record harvest in a row in Australia, among others. Overall, cereal prices increased by 18% year on year, with barley, maize and wheat prices rising particularly strongly, while rice prices on average remained largely unchanged. Prices have declined somewhat following the implementation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative,3 allowing significant amounts of grains to be exported through three key Ukrainian ports.

Sugar production increased as a result of a significant recovery in Brazil’s output, the world’s largest sugar producer and exporter, and increased production notably in Australia, China and Thailand, which more than offset declines in the European Union, India and Pakistan. Overall, global sugar production increased by more than 4% in 2022/23 and exceeded slightly increasing sugar demand, driven among others by population growth and urbanisation in Africa and growing demand from the processing industry in Asia but limited by lower economic growth. International sugar prices, which peaked in April, declined thereafter, but rebounded strongly since October 2022. On average, prices in 2022 were 5% higher than in 2021, a much less pronounced increase compared to other food commodities and dampened by the global supply surplus.

Overall, average farm receipts (including budgetary transfers from agricultural policies) across the 54 countries covered in this report, which have been rising continuously since 2016, are estimated about 5% higher4 than in 2021, mostly driven by higher international commodity prices. This increase is slightly above the average growth during the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, but lower than growth in the two years of the pandemic. This suggests that on average, farm revenues have not only proved relatively resilient vis-à-vis the COVID-19 pandemic but also against the implications of the war in Ukraine. However, farmers also faced significant increases in the prices for key production inputs such as fertilisers and fuels, meaning that production margins and incomes have likely developed less favourably than revenues.

Policy responses to the war in Ukraine and to inflationary pressures more generally

As supply chains were recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, inflationary pressures and the outbreak of war had profound impacts on global agro-food systems in 2022. World prices for grains and oilseeds rose as tensions escalated and spiked following the outbreak of war (OECD/FAO, 2023[2]). These effects were particularly important for commodities such as wheat, barley, maize and sunflower oil for which Ukraine is among the largest global exporters (more context on Ukraine’s importance to global agricultural markets is provided in Box 2.1). Input costs such as for fertiliser and energy also rose due to reduced global supply. Russian exports of natural gas declined following the outbreak of war, and supply concerns prompted some producing countries to restrict exports of fertiliser to ensure domestic availability.

Policy responses to these global challenges were introduced by most countries covered in this report in 2022. These included direct support measures to farmers, consumers, and food processors; measures dealing with fertiliser supplies and prices; measures to facilitate imports and restrict exports of critical materials. Countries also introduced measures to improve the prospects for Ukrainian agriculture.

Box 2.1. Impacts of the war on Ukraine's agricultural sector

On 24 February 2022, Russia started its large-scale invasion of Ukraine which marked the beginning of the largest military conflict in Europe since World War II. The war has caused significant damage to Ukraine’s economy which shrank by close to 30% in 2022.

Agriculture accounted for more than 10% of total GDP and almost 15% of employment in Ukraine prior to the war, but production and trade have fallen considerably since. The impacts on the sector include damage to infrastructure and material, labour shortages, loss of productive land, direct loss of production, shortage and high costs of agricultural inputs, and reduced export capacity, among others.

More than USD 6.6 billion in agriculture and land resources have been damaged or lost (Kyiv School of Economics, 2023[3]). This includes agricultural machinery and equipment on farms along with infrastructure such as elevators and grain storage. More detailed estimates as of September 2022 suggest that 6.5 million tonnes of storage capacity had been destroyed, with another 2.9 million tonnes of capacity having been partially damaged (Kyiv School of Economics, 2022[4]).

Agriculture may have lost up to 15% of its labour force1 as many former farm workers now serve in the Ukrainian military. Land use is imperilled too as agricultural land has become part of the battleground, impacted by artillery strikes and land mines that make sowing and harvesting potentially life-threatening tasks. This touches farms not only in areas close to the combat zones but in large parts of the country.2 Estimates of the area affected differ widely, ranging from just over 1% of Ukraine’s farmland3 to as much as 30% of the country’s territory, including in several highly agriculture dependent regions4, with other estimates falling in-between.5 High concentrations of toxins from munitions and fuel pose an additional threat to agricultural land. At least 10.5 million hectares of agricultural land in Ukraine could be degraded, equivalent to a quarter of its total farm land.6

Economic losses to agriculture go well beyond destroyed or damaged property and were estimated to exceed USD 34 billion as of October 2022 (Kyiv School of Economics, 2022[5]), which would correspond to one-sixth of the country’s GDP in 2021. These losses include the effects of reduced crop production in 2022 (more than USD 11 billion), expected production shortfalls in the winter crop 2023 (USD 3 billion), livestock losses, higher input costs (notably for diesel and fertilisers, close to USD 1 billion) and depressed output prices due to disruptions in logistics and export facilities (more than USD 18 billion).

Before the war, Ukraine was an important producer and exporter of agricultural products, notably grains and vegetable oil. Over the five years preceding the war, Ukraine produced 4% of the world’s wheat, 3% of its maize and 6% of its barley. However, Ukraine’s shares in global exports were multiples of those at 9%, 14% and 12%, respectively (Figure 2.2), placing the country among the top five exporters for these commodities. The country’s importance was even higher in some oilseeds, with production of sunflower seed exceeding 25% of the world total. Ukraine was the world’s largest exporter of sunflower oil, originating 43% of global sunflower oil exports. Due to the very good harvest in 2021, shares in the year just preceding the war were even higher.

Figure 2.2. Ukraine's share in global production and exports of selected agricultural commodities

The combined production of wheat, maize, barley and sunflower seed could fall by between one-fifth and one-third relative to this five-year average due to the war, and by between one-third and a half relative to the year preceding the war.7 Total agricultural production in 2022 is estimated to have been about 28% below its 2021 level.8 This, combined with the damage to infrastructure and blockage of ports, significantly hinders Ukraine’s exports of these products. While data for the full marketing year following the invasion remain incomplete, exports of agricultural commodities are estimated to have fallen significantly in the 2022 marketing year and to be lower still in 2023 (OECD/FAO, 2023[2]), with future developments strongly depending on the continuation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (Figure 2.3). Wheat and barley (the most important cereal in “other coarse grains”) exports are most strongly affected. Due to damage to infrastructure, more sunflower seed was exported rather than processed domestically in 2022, leading to some increased oilseed exports compared to historical averages.

Figure 2.3. Ukraine’s exports 2022 and 2023 of selected agricultural commodities

Source: OECD/FAO, (2023[2]).

3. Forbes Ukraine as reported by (USDA, 2023[8]).

4. Ukrainian authorities as reported by (UNOCHA, 2023[9]).

5. The Yale School of Environment estimates that “some 15 percent of farmland in Ukraine has been littered with land mines” (https://e360.yale.edu/digest/russia-ukraine-war-environmental-cost-one-year), an assessment that is backed up by (GLOBSEC, 2023[10]) and by the Agrarian Committee of the Parliament, as cited by d’Istria (2023[11]), which in March 2023 spoke of about 5 million hectares of farmland that would be unusable due to landmines, explosive remnants and continued combat.

6. Ukraine’s Institute for Soil Science and Agrochemistry Research. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/soils-war-toxic-legacy-ukraines-breadbasket-2023-03-01/.

7. Estimates by USDA and the Ukrainian Grain Association (Martyshev, Nivievskyi and Bogonos, 2023[12]).

8. State Statistics Service and the Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine.

Many countries introduced or increased support for rising input costs….

The rising costs of farm inputs were a global concern for farmers and policymakers responded with a number of different types of support to assist. Some countries introduced policy support targeting specific inputs, such as the Philippines which provided fuel discount vouchers to farmers. Others provided support to specific industries. For instance, China provided three rounds of direct subsidies to grain farmers between March and August 2022. Certain provinces also provided additional area and/or production payments to encourage higher production of soybean and intercropping of maize and soybean. Japan provided payments to livestock farmers to compensate for higher feed costs.

Countries also introduced more general support to compensate for rising input costs. For instance, Canada increased the interest-free limit on loans under its Advance Payment Program for 2022 and 2023, providing interest rate relief to participating agricultural producers. Colombia provided input cost support to small-holder farms through a 20% refund on the value of purchases of agricultural inputs. Iceland increased existing payments and introduced new payments to accommodate increased production costs. Norway similarly increased the size of its annual support package to farmers by a substantial amount, including one-off exceptional payments to compensate for rising input costs. Korea provided tax relief to farmers and direct compensation for higher feed and fertiliser prices. In the United Kingdom, the government of Northern Ireland expedited the delivery of direct payments to assist farmers with cash flow.

The European Union implemented an aid framework allowing individual Member States to implement direct support to farmers and rural areas; exceptional market measures; actions to foster the overall resilience of the sector; and exceptional flexibilities in the use of CAP funding. EU Member States implemented their own suite of support measures, such as tax concessions, investment assistance, and allowances to consumers and farm households to help farmers and agro-food enterprises cope with the financial impacts.

…including support to farmers for fertiliser

Fertiliser supply was of particular concern for many countries and led to many measures to attempt to either reduce costs to farmers or dependence on fertiliser. For instance, Chile both provided fertiliser and gave per hectare payments to compensate for rising variable input costs as part of the country’s Sow for Chile (Siembra por Chile) programme. India increased its fertiliser subsidies twice during 2022 and Mexico increased its subsidy by 16-fold across 2022 and 2023. The Philippines implemented subsidies for fertiliser in the form of fertiliser discount vouchers as part of its Plant, Plant, Plant Part 2 programme. Switzerland released 20% of its strategic reserves of fertiliser in 2021 in response to early supply difficulties in international and kept the measure in place throughout 2022 to mitigate the market effects of Russia’s war of aggression, equal to roughly one third of the country’s annual needs for crop production. Japan subsidised transportation and storage costs for fertiliser manufacturers to compensate for costs associated with changing suppliers. The United States announced the new Fertiliser Production Expansion Program to increase domestic fertiliser availability.

Internationally, a group of countries announced the Global Fertiliser Challenge in 2022. The challenge seeks to both strengthen food security and reduce agricultural emissions by advancing fertiliser efficiency and alternatives in low-and middle-income countries. It hopes to achieve this challenge through innovation and knowledge sharing on fertiliser-efficient farming practices. US and European officials announced at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) that USD 135 million in funding had been raised for the effort.

Some countries suspended environmental requirements to encourage domestic production

Several countries made decisions to postpone the implementation of sustainability measures as a response to food security concerns stemming from the war in Ukraine. The European Union adopted an exceptional flexibility to allow agricultural production on fallow land while still maintaining the full level of the associated income support payments. This option was taken up by several EU Member countries, including Austria, Belgium (Wallonia), the Czech Republic, France, Germany (partly), Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg and Poland. Switzerland similarly postponed measures to fallow cropland for the promotion of biodiversity by one year.

Additional support was provided for agricultural consumers

Rising inflation and cost of living was an issue for many countries in 2022. Some countries introduced measures to specifically aid agricultural consumers. For instance, China began releasing strategic supplies of pig meat with the objective of stabilising prices. The government in the Philippines imposed price ceilings for staple foods such as milk, beef, poultry and pork in an effort to counter food price inflation. In the United States, additional food assistance was provided for children in eligible families as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act. Many more countries introduced other measures that were not agriculture-specific and increased consumer incomes. These included actions such as reducing various taxes; raising minimum wages and welfare payments for the poorest in society; energy price caps; and one-off cash payments.

Other countries implemented policies to assist processing firms who use agricultural products as inputs. For instance, Japan subsidised the costs of food producers to develop, manufacture, and source materials for new food products. Belgium introduced emergency changes to labelling regulations allowing food producers to more easily change the composition of food products and still abide by labelling requirements.

Trade restrictions were eased on some imports….

Several countries sought to make importing inputs and food easier to avoid domestic shortfalls. Brazil temporarily suspended some agricultural tariffs from non-Mercosur countries, including on maize, soybeans, soymeal and soy oil. China signed a protocol to allow imports of maize from Brazil as part of its strategy to diversify its import sources of key commodities. Colombia removed tariffs on all agricultural inputs and 163 basic household consumer products. Mexico similarly exempted tariffs on imports of 5 strategic agricultural inputs and 21 basic consumer goods. Switzerland reduced tariffs on animal feed imports from 15 March 2022. Some EU Member States made use of existing flexibility in EU legislation to make imports of animal feed easier, for example Spain relaxed maximum residue limits for pesticides in maize. Korea reduced the tariff rate to 0% for wheat and flour imports within quota to alleviate upward pressure on prices, and increased the quota for unhulled barley, wheat hull and root vegetables to secure supplies of feed.

Countries also facilitated trade as a way of providing economic support for Ukraine. Australia, Canada, Iceland, the European Union, the United Kingdom and the United States all implemented temporary exemptions from tariffs on agricultural products imported from Ukraine.

….but trade restrictions were increased on some exports

India introduced export bans, duties or permits on commodities such as rice, wheat, sugar and related products. China imposed a ban on state-owned phosphate producers from exporting phosphate starting from October 2021 until June 2022 and introduced a new requirement for inspection certificates to ship fertilisers. In addition, a quota limiting total phosphate exports to 3.16 million tonnes was introduced for the second half of 2022. Mexico introduced a 50% export tariff on white maize for human consumption.

Countries also provided support for Ukraine and Ukrainian agriculture

Along with domestic measures to assist with the fallout from the war, many countries also took steps to support Ukraine. As mentioned in Box 2.1, Ukraine was a significant exporter of grain and oilseeds before the war and exports were significantly hampered following its outbreak. To assist with the challenges, the Black Sea Grain Initiative was brokered with the assistance of Türkiye and the United Nations to allow Ukraine to resume exports of grain through the Black Sea. A Joint Coordination Center with officials from Türkiye, Russia and Ukraine and the United Nations was set up in Istanbul to oversee shipments of grain from three Ukrainian Black Sea ports. The European Union also assisted in establishing “Solidarity Lanes” to ensure Ukraine can export grain and import essential goods, such as animal feed, fertiliser, and humanitarian aid. The “Solidarity Lanes” and the Black Sea Grain Initiative allowed the export of about 25 million tonnes of Ukrainian grain, oilseeds and related products between May 2022 and the end of October 2022 (EC, 2022[13]). Despite these initiatives, logistics costs and bottlenecks have caused a larger-than-usual amount of Ukrainian grain to be marketed in neighbouring countries. In April 2023, Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, and the Slovak Republic all introduced measures to ban imports of a range of agricultural products from Ukraine as a result. An agreement was soon made following intervention from the European Commission which keeps the import bans in place but allows Ukrainian grain to transit through these countries for export elsewhere. Romania joined this agreement later in April.

Countries worked together with private companies and international organisations to aid Ukraine with seed and infrastructure investments. In February 2023, the United States (through the US Agency for International Development, USAID) and biotechnology company Bayer provided a joint donation of 13.5 tonnes of high-quality vegetable seeds to Ukrainian farmers in advance of planting season. USAID also partnered with agribusinesses Grain Alliance, Kernel and Nibulon to invest USD 44 million in storage and infrastructure expansion to help enable Ukraine to increase its grain shipping capacity. Japan partnered with the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) to provide maize and sunflower seeds to agricultural producers and small farms during the 2023 spring-summer season. The Netherlands included EUR 40 million (USD 42 million) for the purchase of seed and equipment as part of its 2023 support package for defence and recovery.

To help address the challenges related to the large-scale contamination of Ukrainian agricultural land with mines and other explosives (Box 2.1), the Netherlands provided EUR 10 million (USD 11 million) for demining as part of its 2023 support package to Ukraine. Switzerland also included CHF 7.5 million (USD 8 million) in targeted support for mine clearance in Ukraine over the next few years as part of its “Action Plan on Mine Action 2023-2026

The United States and Ukrainian agricultural ministries issued a memorandum of understanding to co-operate on areas of productivity data, shared expertise and guidance on new technologies, and enhanced co-operation on bilateral trade and post-conflict capacity building. To date, technical assistance and other initiatives have been launched in the areas of animal health, biosecurity, sanitary and phytosanitary capacity building, agricultural and trade policy, wildfire control, water management, and preventing illegal deforestation.

The European Union activated the Temporary Protection Directive, granting access to labour market, housing, education and healthcare across the European Union to over 4 million people fleeing the war. Poland extended the admissible period of employment for Ukrainian citizens involved in harvest assistance. The Czech Republic supported inclusion of Ukrainian scientists, and students in research teams, including providing CZK 6 million (USD 269 224) to subsidise salaries of Ukrainians joining certain projects in agriculture, forestry, fisheries and aquaculture.

In addition to these activities, the OECD launched its Ukraine Country Programme to support Ukraine’s agenda for reform, recovery and reconstruction, including related to agriculture (Box 2.2).

Box 2.2. OECD Ukraine Country Programme

The OECD and the government of Ukraine launched a four-year Country Programme that will support Ukraine’s agenda for reform, recovery and reconstruction and will help Ukraine advance its ambitions to join the OECD and the European Union. The programme will enable Ukraine to leverage OECD expertise and best practices, strengthen institutions, and build capacity for successful policy reforms aligned with OECD standards and best practices. It will consist of reviews and other projects resulting in policy recommendations and capacity building activities; legal instruments for Ukraine to advance alignment with the Organisation’s standards; and targets to enhance Ukraine’s participation in OECD bodies.

Together with energy, agriculture will be one of the two focus areas of sectoral policy work within the programme. The OECD has monitored developments in Ukraine’s agricultural policy and provided recommendations and analysis as part of this publication since 2004 and will continue to do so into the future. The programme intends to build upon this work as the situation in Ukraine stabilises to conduct an OECD Agricultural Policy Review. Ukraine could also consider being a potential new member of the Co-operative Research Programme: Sustainable Agricultural and Food Systems.

Note: Further information about the Ukraine Country Programme is available at https://www.oecd.org/mcm/documents/Ukraine-Country-Programme.pdf.

Other recent developments in agricultural policies

While policies for agriculture and food have been strongly influenced by the war in Ukraine, not all policy changes introduced in 2022 were related to the war situation. This section provides a summary of some other major trends in agricultural policies implemented by countries. More details on specific policies are available within the relevant country chapters.

Several countries implemented changes to their policy frameworks

A number of countries updated their policy frameworks for agriculture during the year. The EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) for 2023-27 entered into force in January 2023. This new CAP is built around ten specific objectives: ensuring fair incomes for farmers; increasing competitiveness; improving the position of farmers in the food chain; climate change action; environmental care; preserving landscapes and biodiversity; supporting generational renewal; vibrant rural areas; protection of food and health quality; and fostering knowledge and innovation. Under the new CAP, Member States play a key role in designing and implementing their CAP 2023-27 Strategic Plans to achieve EU-level objectives. Canada agreed on its new five-year agricultural policy framework for 2023-28, called the Sustainable Canadian Agriculture Partnership. The framework focuses on five priorities: climate change and environment; market development and trade; building sector capacity, growth, and competitiveness; resiliency and public trust; and science, research and innovation.

In Colombia, the new administration introduced the Towards Agriculture for Life (Hacia Una Agricultura Para La Vida) development plan for 2022-26. The plan focuses on five key strategies of comprehensive land reform; addressing inequalities facing indigenous, black, women, and young people in the sector; environmental protection and sustainability; market inclusion on agricultural value chains; and a territorial approach. In the United Kingdom, both Wales and Northern Ireland introduced new policy framework documents. The Agriculture (Wales) Bill was introduced by the Welsh parliament setting the overarching framework for future support for agriculture with a major focus on sustainable land management. The Northern Ireland ministry published the Future Agricultural Policy Decisions report along with 54 policy decisions on the future of agricultural support. The Philippines published the National Agriculture and Fisheries Modernisation Plan that serves as the directional plan for the agricultural sector for the next decade.

Argentina launched the Plan GanAr with the aim of contributing to the sustainable development of Argentine livestock. Australia drafted the National Agricultural Traceability Strategy 2023-28 and its five-year implementation plan. The strategy aims to develop connected, aligned and interoperable world-class traceability systems along supply chains to accelerate premium Australian exports and enhance biosecurity and food security. The United States introduced a new rule, Requirements for Additional Traceability Records for Certain Foods, which establishes traceability recordkeeping requirements for participants in supply chains of certain foods in an effort to facilitate rapid identification and removal of potentially contaminated food from the market.

Costa Rica reduced market price support and liberalised trade in paddy and milled rice in 2022 as part of its Rice Path strategy. In 2023, the government unveiled a new public policy governing the agricultural sector for 2023-32 aiming for greater prominence of Costa Rican products in international markets; creating decent jobs; and improving living conditions. Israel similarly underwent important sector reforms for egg, dairy and beef production, and limited tariffs on selected produce. Production quotas for eggs and dairy target price mechanisms will be progressively phased out over time, while tariffs for chilled beef were eliminated and replaced with direct payment compensation and branding investments. Tariffs were also cut on selected fruits and vegetables and agricultural inputs.

Some countries increased their climate mitigation ambitions

Countries unveiled new measures relating to climate change. Chapter 1 of this publication provides a detailed discussion of the many adaptation policies implemented by countries. However, several countries also took further steps to mitigate the contribution to climate change of their agricultural sectors. Australia invested new funds into discovering technological solutions to reduce agricultural emissions and announced knowledge transfer initiatives to encourage farmers to participate in carbon markets and integrate low-emission technologies into their operations. Canada tabled its 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan in March 2022 which outlines efforts it is undertaking across all sectors to meet its 2030 emissions target and lay the foundation for achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. New Zealand published its first Emissions Reduction Plan in May 2022. The plan contains several key actions including the introduction of an agricultural emissions pricing mechanism by 2025, among others. The United States launched its initiative Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities in 2022, providing USD 3.1 billion in funding for 141 pilot projects to expand markets for climate-smart commodities.

Several countries also pledged to increase the ambition of their climate mitigation targets. Australia, India, Norway and Viet Nam all updated their emissions reductions targets, and Australia, Austria, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, and the United Kingdom all joined the Global Methane Pledge in 2022. Of the 54 countries covered in this report, 19 have mitigations targets specifically for the agricultural sector. A summary of emissions reductions targets of all 54 countries is provided below (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Emissions reductions targets

|

|

Economy-wide emissions reduction targets |

Long-term strategy submitted to UNFCCC |

Agriculture-specific target (base year/level) |

Global methane pledge (reduce global anthropogenic CH4 30% from 2020 levels by 2030) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2030 target (base year/level) |

2050 target |

||||

|

Argentina |

Max 349 MtCO2eq |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

Australia |

-43% (2005) |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

Brazil |

-50% (2005) |

Net zero |

No |

None |

Yes |

|

Canada |

-40-45% (2005) |

Net zero |

Yes |

-30% fertiliser emissions by 2030 (2020) |

Yes |

|

Chile |

Max 95 MtCO2eq |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

China |

Peak CO2; -65% GDP emission intensity (2005) |

Net zero by 2060 |

Yes |

None |

No |

|

Colombia |

Max 169.4 MtCO2eq |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

Costa Rica |

Max 9.11 MtCO2eq |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

European Union |

-55% (1990) |

Net zero |

Yes |

None at EU level |

Yes |

|

EU Member States |

19 out of 27 countries (except Bulgaria, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Ireland, Italy, Poland, Romania) |

2030 Targets: Belgium -25% (1990); Denmark -55-65% (1990); Germany -31-34% (1990); Spain -18% (2005); France -18% (2015); Ireland -25% (2018); Portugal -11% (2005); Netherlands -3.5 MtCO2eq |

22 out of 27 countries (except Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania) |

||

|

Iceland |

-55% (1990) |

“Largely neutral” by 2040 |

Yes |

Carbon neutral by 2040 |

Yes |

|

India |

-45% GDP emission intensity (2005) |

Net zero by 2070 |

Yes |

None |

No |

|

Indonesia |

-32% (BAU); up to ‑43% conditional on int. support |

Net zero by 2060 |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

Israel |

-27% (2015) |

-85% from 2015 levels |

No |

None |

Yes |

|

Japan |

-46% (2013) |

Net zero |

Yes |

49.5 MtCO2eq by 2030 |

Yes |

|

Kazakhstan |

-15% (1990) |

None |

No |

None |

No |

|

Korea |

-40% (2018) |

Net zero |

Yes |

-27.1% by 2030; -37.7% by 2050 (2018) |

Yes |

|

Mexico |

-25% (BAU); up to ‑40% conditional on int. support |

None |

Yes |

-8% by 2030 (BAU) |

Yes |

|

New Zealand |

-50% (2005) |

Net zero |

Yes |

-24-47% reduction in biogenic methane by 2050 |

Yes |

|

Norway |

-55% (1990) |

-90-95% (1990) |

Yes |

Voluntary agreement with agriculture sector: -5 MtCO2eq by 2030 |

Yes |

|

Philippines |

-2.7% (2020); up to ‑72% conditional on int. support |

None |

No |

-29.4% by 2030 (BAU) conditional on int. support |

Yes |

|

Russia |

-30% (1990) |

Net zero by 2060 |

Yes |

None |

No |

|

South Africa |

350-420 MtCO2eq (BAU 398-614 MtCO2e) |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

No |

|

Switzerland |

-50% (1990) |

Net zero |

Yes |

-40% by 2050 (1990) |

Yes |

|

Türkiye |

-21% (BAU) |

Net zero by 2053 |

No |

None |

No |

|

Ukraine |

-65% (1990) |

Net zero by 2060 |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

United Kingdom |

-68% (1990) |

Net zero |

Yes |

-17-30% by 2030; -24-40% by 2035 (2019) |

Yes |

|

United States |

-50-52% (2005) |

Net zero |

Yes |

None |

Yes |

|

Viet Nam |

Reduction of 15.8% (BAU) or 146.3 MtCO2eq (unconditional distribution); 43.5% or 403.7 MtCO2eq (conditional distribution with international financing) |

Net zero |

No |

-43% (BAU) by 2030, Decision No. 888/QD-TTg |

Yes |

Several countries responded to natural disasters with assistance to their agricultural sectors

Several countries that experienced natural disasters implemented direct support to those affected within the agricultural sector. Argentina adopted exceptional measures in 2022 and 2023 to compensate territories affected by droughts, fires and frost. In October 2022, provincial governments in Canada implemented programmes to provide additional support to agricultural producers significantly affected by Hurricane Fiona. China provided disaster relief funds to 13 provinces affected by floods and droughts. Several EU Member States, such as Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Poland, Romania and the Slovak Republic provided disaster relief funding for various adverse weather events in 2022, ranging from droughts, floods, frost, hail, torrential rain, hurricanes, landslides and avalanches. New Zealand responded to a record number of weather-related adverse events, including flooding, drought and cyclones, by providing funding for psychosocial support, recovery and clean-up. The United States launched two temporary programmes in 2022 to compensate for losses incurred in prior years – the Emergency Livestock Relief Program and Emergency Relief Program.

Many worked on policies which will improve environmental sustainability

Australia launched several new measures that trial market-based approaches to incentivise landholders to improve biodiversity as part of the Agriculture Biodiversity Stewardship Package. These include the Carbon + Biodiversity Pilot, and the Enhancing Remnant Vegetation Pilot. A National Stewardship Trading Platform was also established allowing landholders to plan and evaluate carbon and biodiversity projects, and options are being explored to implement the Australian Farm Biodiversity Certification Scheme to certify farm businesses for their biodiversity management. As of 30 April 2023, the European Union completed 47 of the more than 100 actions committed to in the EU Biodiversity Strategy intended to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. Several EU Member States also adopted new regulatory measures to reduce the environmental impacts of agricultural inputs, including Austria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, France, Poland, Romania, and Spain. The EU CAP 2023-27 introduced a new “green architecture” with higher environmental ambitions, including stricter basic requirements (conditionality) in cross-compliance. Twenty-five per cent of the direct payments budget is dedicated to eco-schemes, a new policy tool that has been introduced to incentivise the adoption of farming practices with additional environmental benefits. These schemes are part of the CAP’s long-standing commitment to helping farms make necessary ecological transitions.

Japan added nine key performance indicators to its 2030 MIDORI plan, including zero CO2 emissions from fossil fuels combustion in agriculture, forestry and fisheries sectors; reductions in risk-weighted use of chemical pesticides and chemical fertiliser; and increases in organic farming. In the United Kingdom, England launched a programme on sustainable farming standards for arable and horticultural soils, improved grassland soils and the moorlands. Numerous conservation projects were introduced to restore over 40 000 hectares of land to protect and provide habitats for wildlife as part of the Landscape Recovery scheme. The United States gave a substantial funding increase of approximately USD 20 billion over ten years to various conservation programmes as part of the Inflation Reduction Act. New initiatives were also launched in 2022 to assist businesses to transition to organic farming. In 2022, Viet Nam approved the National Green Growth Action Plan for 2021-2030 which includes goals to develop a sustainable and low-emissions agricultural sector that is adaptable in the face of climate change.

Countries took steps to foster inclusion in the sector

To improve equity and inclusion, the United States undertook several actions focused on improving equity for farmers from minority groups. These include new investments in Equity Conservation Cooperative Agreements, funding various outreach and assistance programmes and releasing the USDA Equity Action Plan. Canada renewed the AgriDiversity Program which aims to reduce barriers to participation for indigenous peoples and increase economic development through capacity building activities. Most EU Member States proposed to maintain higher rates of investment support for young farmers and the vast majority include plans for additional income support and installation aid for young farmers in their Strategic Plans. Some EU Member States, such as Austria, Germany, Ireland, Italy and Spain, included specific measures supporting rural women in their CAP 2023‑27 Strategic Plans. In particular, Spain included direct payments for young female farmers who own or co-own their farm.

Countries implemented new programmes for innovation and the modernisation of agriculture

Countries introduced a number of new initiatives aimed at knowledge generation in agriculture. In the European Union, the European Commission presented four new partnership programmes as part of its Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Framework. These are designed to bring together the European Commission and a consortium of partners, structured around research funders and other public authorities, to tackle some of the European Union’s most pressing challenges in agriculture by stimulating public and private investment in research activities.

Korea announced new innovation measures to enhance smart agriculture, with goals to convert 30% of horticultural and livestock facilities into smart facilities. The Philippines approved the Coconut Farmer and Industry Development Plan, aimed at modernising the coconut industry and increasing incomes and competitiveness of farmers. India introduced new support for the use of drones in agricultural activities to modernise land records, check the state of crops and for pesticide and fertiliser application.

Other countries made changes to modernise programme delivery. Türkiye made additional efforts to advance digital transformation, including the Tarim Cebimde mobile application deployment and the new Farmer Registration System which both make it easier to register applications and receive product notifications. The application also provides some functionality for livestock farmers to monitory herd demographics. Kazakhstan introduced the Unified State Information System for Subsidies to streamline subsidy registration and remove the need for farmers to pay subscription fees to apply for subsidies.

New laws and programmes on biosecurity and animal health were introduced

A number of new and ongoing disease outbreaks prompted countries to tighten biosecurity regulations. Australia passed the Biosecurity Amendment (Strengthening Biosecurity) Act 2022 to strengthen the ability to manage and respond to emerging biosecurity risks. Canada provided new funding to enhance efforts to prevent African Swine Fever (ASF) from entering the country and to prepare for a potential outbreak. Outbreaks of avian influenza led several EU Member States to adopt policies such as bans on outdoor poultry farming (the Czech Republic), vaccination programmes (France) and compensation payments for affected producers (France, Poland). In 2022, Indonesia declared an outbreak of Foot-and-Mouth disease for the first time in more than 30 years and introduced control measures including decontamination, massive vaccination, and strengthened surveillance on areas with known infections.

Measures were also introduced targeting animal welfare. New Zealand passed legislation in 2022 ending the export of livestock by sea from April 2023, although with an adjustment period for affected businesses. New Zealand also had a ban on battery cages for layer hens come into effect on 1 January 2023 following a period of adjustment since the ban was passed in 2012. In the United Kingdom, the Animals (Penalty Notices) Act 2022 gives ministers powers to impose financial penalties for a wide range of animal health and welfare offences in England and Wales. In the European Union, Austria and France ended the culling of male chicks in egg-laying hen production as of 1 January 2023, one year after Germany became the first to do so. Austria, Germany and Spain introduced new rules on the transportation of livestock.

Some COVID-19 measures were phased out while new and post-pandemic measures were implemented

Countries generally scaled back some of the support provided in previous years for the COVID-19 pandemic. In June 2022, Australia concluded its temporary emergency freight assistance support that had been introduced in response to the collapse of international airfreight capacity during the pandemic. The EU rules allowing Member States to introduce COVID-19 aid to affected sectors ended on 30 June 2022.

New Zealand lifted the annual cap on Recognised Seasonal Employee Scheme workers from 16 000 to 19 000 places to address seasonal worker shortages experienced during the pandemic. China introduced new disinfection requirements on imports of non-cold chain goods in September 2022. These and other PCR testing requirements were then later removed in December 2022.

Progress was made on several trade deals and negotiations

Countries advanced several multilateral agreements in 2022 and early 2023. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) entered into force on 1 January 2022. The agreement covers 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region including Australia, China, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, the Philippines, Korea and Viet Nam. The agreement foresees reductions to 8.4% of agricultural tariff lines, with an average tariff reduction of 12.8 percentage points. With the introduction of RCEP, around 83% of agricultural tariff lines are either subject to tariff reduction under the agreement or were already at zero (UNCTAD, 2021[14]). The agreement also provides a framework for streamlining rules of origin and border processes for perishable goods, as well as strengthening co-operation in the areas of standards, technical regulations, and conformity assessment procedures.

In other multilateral agreements, in 2022 and 2023, Chile, Malaysia and Brunei became the final three signatories to ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP eliminates 98% of tariffs in the free trade area and contains a number of provisions on agriculture. These include reduced Japanese beef tariffs; new access for dairy products into Japan, Canada and Mexico; the elimination of all tariffs on sheep meat, cotton, wool and manufactured products; and some elimination of tariffs on seafood, horticulture and wine. The United Kingdom concluded negotiations to join the CPTPP in 2023 pending ratification of their entry from all 11 signatories. South Africa also ratified the African Continental Free Trade Agreement.

Several bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) were finalised or came into effect in 2022, helping to facilitate trade in agricultural products. These include: the Australia-United Kingdom FTA, the Australia-India Economic Cooperation and Trade Agreement, the Israel-Korea FTA, the Cambodia-Korea FTA, the Indonesia-Korea FTA and the New Zealand-United Kingdom FTA. Many other FTAs are awaiting ratification, including the EU-Chile FTA, the EU-Mercosur agreement, the EU-New Zealand FTA, and the Korea-Philippines FTA. Market access and tariff reductions or phase-outs on agricultural products formed part of most trade agreements. However, products deemed domestically important continue to remain excluded from agreements, such as rice in Korea or wheat, rice and maize in India. The European Union agreements were notable for the novel inclusion of chapters on sustainable food systems, covering co‑operation on topics such as animal welfare, food waste, pesticides and fertilisers among others.

Developments in support to agriculture

This section provides an overview on developments in policy support in agriculture, building on the OECD indicators of agricultural policy support that are comparable across countries and time. These indicators show the diversity of support measures implemented across different countries and focus on different dimensions of these policies. Definitions of the indicators used in this report are shown in Annex 2.A, while Figure 2.4 illustrates the links between, and components of, the different indicators.

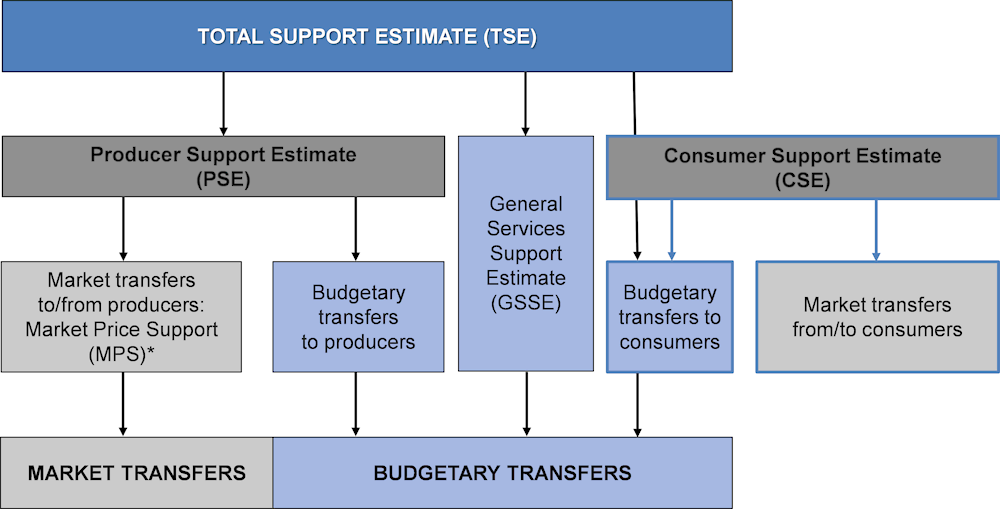

The Total Support Estimate (TSE) is the broadest of the OECD support indicators. It combines three distinct elements: a) transfers to agricultural producers individually; b) policy expenditures for the primary agricultural sector collectively; and c) budgetary support to consumers of agricultural commodities. The TSE is expressed as a net transfer indicator, including both positive and negative elements.

The Producer Support Estimate (PSE) measures all transfers to agricultural producers individually. Two major types of transfers can be distinguished: Market Price Support (MPS) represents transfers from taxpayers and consumers to agricultural producers through domestic prices that are higher than their international reference prices due to domestic and trade policies. MPS can also be negative, representing transfers from producers to consumers through domestic prices that are lower than references prices. Budgetary support is financed by taxpayers only and is further broken down into various categories distinguished by the different implementation of the underlying policies. The PSE indicator is expressed as a net transfer, including both positive and negative elements.

The General Services Support Estimate (GSSE) measures policy expenditures that benefit the primary agricultural sector as a whole, rather than going directly to individual producers. Different types of expenditures are represented in specific categories of the GSSE.

Similarly to the PSE, the Consumer Support Estimate (CES) reports support to consumers of agricultural commodities, distinguishes between market transfers that mirror the MPS, and budgetary support. To avoid double-counting, only the budgetary part of the CSE is included in the TSE.

Figure 2.4. Structure of agricultural support indicators

Note: *Market Price Support (MPS) is net of producer levies and excess feed cost.

Source: Annex 2.A.

Total Support

Total support to agriculture remains around record highs despite recommendations for reform

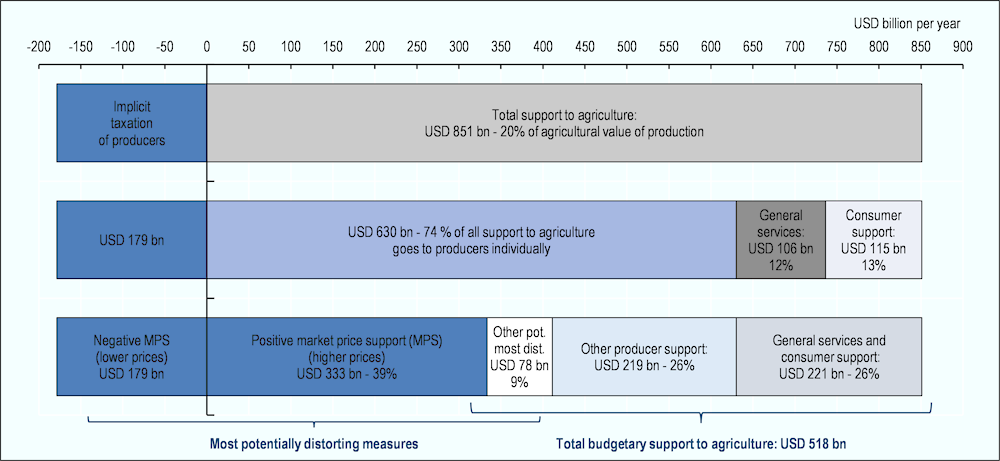

Across the 54 countries covered in this report, total support directed to the sector totalled USD 851 billion per year on average over 2020-22 (Figure 2.5). This is considerably higher than the USD 696 billion averaged in the three years preceding it from 2017 to 2019, largely reflecting policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, inflationary pressure and fallout from the war in Ukraine. Transfers to producers rose by 20% and budgetary consumer support for agriculture was nearly double in 2020-22 compared to 2017‑19. Producer support is estimated to have declined in 2022 due to falling market price support, but still remains higher than pre-pandemic levels.

Of the 2020-22 total, USD 630 billion (74% of total support) goes to producers individually either directly from government budgets or implicitly through market price support (MPS). The remainder of support was split nearly equally between support for general services (USD 106 billion, 12.5%) and budgetary transfers to consumers of agricultural products (USD 115 billion, 13.5%). At the same time, some emerging economies implicitly taxed their producers through measures such as export taxes and other actions which suppress domestic market prices. This implicit taxation was valued at USD 179 billion per year on average between 2020-22.

Figure 2.5. Breakdown of agricultural support, total of all countries, 2020-22

Notes: Data refer to the All countries total, including all OECD countries, non-OECD EU Member States, and the 11 emerging economies.

“Implicit taxation” of producers refers to negative market price support, “General services” refers to the General services support estimate, “Consumer support” is transfers to consumers from taxpayers, “Other pot. most dist.” refers to the potentially most distorting producer support measures other than market price support (i.e. support based on output payments and on the unconstrained use of variable inputs).

Source: Based on OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Support in countries covered in this report has risen consistently over the past 20 years in nominal terms (Figure 2.6). Much of this rise has been driven by emerging economies where support has increased markedly from averaging USD 68 billion per year in 2000-02 to USD 497 billion per year in 2020‑22. China and India account for the vast majority of emerging economy support, valued at USD 310 billion and USD 124 billion, respectively. Agricultural support among OECD countries has grown at a modest rate from a higher base, rising from an average of USD 278 billion per year in 2000-02 to USD 349 billion per year in 2020-22. The United States and the European Union combine for the largest share of OECD support at USD 122 billion and USD 107 billion, respectively, in 2020-22.

Despite the rise in nominal support among OECD countries, total support has been declining consistently relative to GDP. Support in the emerging economies covered in this report generally places a higher burden on their respective economies. This reflects the larger relative importance of agriculture to these economies and policy choices.

Figure 2.6. Evolution of total support to agriculture in OECD and 11 emerging economies, 2000 to 2022

Note: Negative MPS for OECD countries, mostly reflecting adjustments for higher feed costs due to positive MPS for feed commodities, averaged USD 423 million per year between 2000 and 2022, and is therefore too small to be visible on the graph.

The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States. Latvia and Lithuania are included only from 2004.

The 11 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russian Federation, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

Source: OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Expressing support as a share of the value of production adds important context to the data. For the 54 countries covered by this report, the total positive support provided in 2020-22 was equivalent to 20% of the production value generated by the sector. This represents a decline from 29% of the production value of the sector in 2000-02. Across the OECD area, support as a percentage of the value of production fell from 41% in 2000-02 to 25% in 2020-22. In contrast, this percentage rose across the 11 emerging economies from 13% to 17% over the same time frame. However, including the effects of negative MPS (that is, the extent that countries implicitly tax the sector), this percentage rose from 9% to 11%.

The situation varies considerably for individual countries.5 For example, in 2020-22 support as a percentage of production value was between 72% and 83% in Norway, Switzerland and Iceland; less than 5% in Brazil, South Africa, New Zealand and Ukraine; and negative in India, Viet Nam and Argentina (Figure 2.7). The countries that provide the highest level of support relative to the sector’s size are not always those with the highest economic burden of support. This reflects differences in levels of support, levels of economic development and agricultural sector size between countries. For example, countries such as Norway, Switzerland and Iceland have the highest levels of support based on value of production, but because agriculture is a relatively small share of GDP, the economic burden is lower than countries such as the Philippines, China and Türkiye. These latter three countries have the highest support relative to GDP at 2.3%, 1.8% and 1.6%, respectively. In Australia, South Africa, New Zealand and Ukraine, support is 0.25% or less of GDP. China and India, the world’s two most populous countries, are the largest providers of positive support to agriculture (USD 310 billion and USD 124 billion per year in 2020-22, respectively). However, the countries differ in how the support is provided. China provides almost all of its support to the sector in the form of positive market price support, while India provides high levels of producer payments for the use of variable inputs as well as budgetary support to consumers. Although gross support in India is high, its policies suppressing domestic prices result in negative net support to the agricultural sector.

Figure 2.7. Total Support Estimate by country, 2000-02 and 2020-22

Notes: Countries are ranked according to TSE relative to the value of agricultural production (left panel) and relative to GDP (right panel) in 2020-22, respectively.

1. EU15 for 2000-02, EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020, and EU27 from 2021.

2. The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States. Latvia and Lithuania are included only for 2020-22.

3. The 11 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russian Federation, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

4. The All countries total includes all OECD countries, non-OECD EU Member States, and the Emerging Economies.

Source: OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Producer Support

Reform to producer support has stalled in recent years

Preliminary estimates for 2022 across the 54 covered economies indicate that the level of support to individual producers declined for a second year when measured relative to gross farm receipts (an indicator referred to as %PSE). This decline largely reflects an estimated decline in market price support (and increase in negative market price support) due to rising world prices rather than substantial policy reforms. On a three-year average, the %PSE across the 54 countries equalled 10% of gross farm receipts in 2020‑22, relatively unchanged from 2010-12 and down from 18% in 2000-02.

Producer support among OECD countries has been in long-term decline. However, the rate of decline has slowed since the early 2010s (Figure 2.8). OECD producer support averaged 15% of gross farm receipts in 2020-22, compared to 18% in 2010-12 and 28% in 2000-02. Levels of producer support among the 11 emerging economies rose markedly starting in the 2010s before stabilising at about half the OECD average. The average %PSE in these economies averaged 7.1% in 2020-22, compared to 4.5% in 2010‑12 and 3.9% in 2000-02. However, these figures for average support to producers include the effects of negative market price support. Countries such as Argentina, India and Viet Nam employ measures such as export taxes or other programmes which implicitly tax producers by suppressing domestic prices. Excluding negative market price support, the %PSE among emerging economies was 13.0% in 2020-22, close to but still below the OECD average, while across all 54 countries, the positive producer support corresponded to 13.7% of gross farm receipts.

Figure 2.8. Evolution of the % Producer Support Estimate, 2000 to 2022

Notes: The two bars relate to the 11 Emerging Economies and represent a decomposition of PSE into its positive and negative parts.

1. The All countries total includes all OECD countries, non-OECD EU Member States, and the 11 emerging economies.

2. The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States. Latvia and Lithuania are included only from 2004.

3. The 11 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russian Federation, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

Source: OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Only four economies – China, Japan, the European Union, and the United States – account for roughly 70% of all positive producer support over the past 20 years. However, the relative shares among these economies have changed dramatically over this time (Figure 2.9). In 2000-02, the European Union6 accounted for the largest share with 30% of all positive producer support, followed by Japan (17%), the United States (17%) and China (7%). In 2020-22, China now represents just under 44% of producer support, followed by the European Union7 (15%), United States (7%) and Japan (5%). India has accounted for a majority and growing share of all implicit taxation among countries, from 61% of all negative support in 2000-02 to 76% in 2020-22.

Figure 2.9. Producer support by country, 2000 to 2022

Note: European Union refers to EU15 for 2000-03, EU25 for 2004-06, EU27 for 2007-13, EU28 for 2014-19, EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020, and EU27 from 2021.

Source: OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

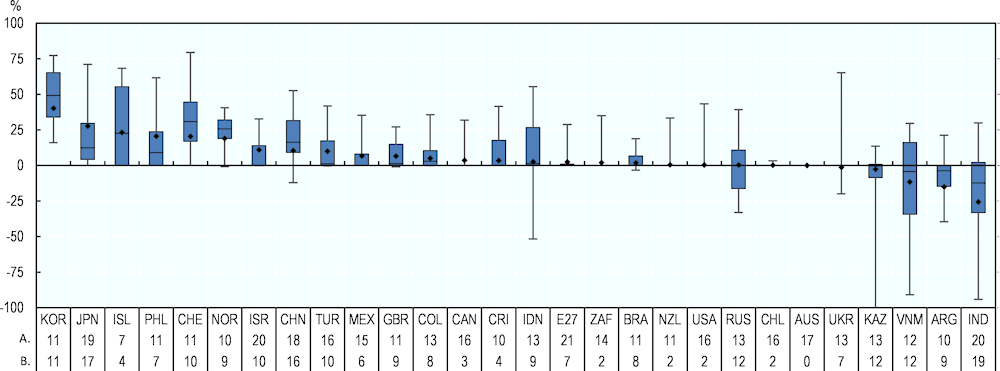

While China provides the most support in terms of value transferred, the countries with the highest levels of producer support as a share of gross farm receipts are all found in the OECD area (Figure 2.10). In Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, Korea, and Japan, the benefits arising from direct budgetary support as well as implicit support from measures such as protective tariffs on imports represent between 35% and 55% of the revenue received by farmers. Conversely, support accounts for about 15% of farm receipts in China and less than 5% in New Zealand, South Africa, Chile, Brazil, Costa Rica, Australia, and Kazakhstan (including the negative effects of implicit taxation from policies in Kazakhstan).

Figure 2.10. Producer Support Estimate by country, 2000-02 and 2020-22

Notes: Countries are ranked according to the 2020-22 levels.

1. EU15 for 2000-02, EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020, and EU27 from 2021.

2. The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States. Latvia and Lithuania are included only for 2020-22.

3. The 11 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russian Federation, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

4. The All countries total includes all OECD countries, non-OECD EU Member States, and the Emerging Economies.

Source: OECD (2023), “Producer and Consumer Support Estimates”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/agr-pcse-data-en.

Governments use a mix of different types of policies in order to achieve their objectives and support farmers, and each may emphasise different types of policies. For instance:

Market price support (MPS) arises as a result of domestic or trade policies that raise or lower domestic market prices, such as border tariffs, export taxes and price ceilings or floors. Excluding policies that depress prices, MPS accounts for the majority of positive support provided to farmers across all covered economies both in aggregate as well as within a majority of the covered economies (counting the European Union collectively as one economy).

Payments based on output are payments made to farmers per unit of production, often through measures such as strategic stabilisation funds or deficiency payments. These types of payments were between 10% and 25% of support in Iceland and Norway between 2020 and 2022.

Payments based on use of variable inputs, such as subsidies on the use of fertiliser, electricity, animal feed or credit. These types of payments were between 20% and 40% of positive support in South Africa, Viet Nam and Australia, and 70% of positive support in India in 2020-2022.

Payments made on the basis of production area or animal numbers, or to top up farmers’ receipts or incomes. This approach was the largest share of support provided to producers in the OECD in 2020-22, reflecting its prominence in the support packages provided in economies such as the European Union, the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States.

Payments made to subsidise the acquisition of fixed capital like farm equipment, land, or breeding stock. This approach accounted for over 30% of the positive support provided to producers in Australia, Chile, and Kazakhstan.

Payments are provided to individual farmers to reduce the cost of on-farm services such as technical, accounting, commercial, training and sanitary or phytosanitary assistance. This type of support made up between 10-25% of total producer transfers in New Zealand, Chile, and the United States.

Payments can be based on variable input use, but with constraints, limits or restrictions. Brazil was the only country which used this form of support for more than 10% of their transfers to producers.

Payments for non-commodity criteria, which include payments for long-term resource retirement or for non-commodity based output such as reducing pesticide or fertiliser use, or linked directly to supply of environmental public goods. This type of support was 10-20% of producer transfers in Mexico and Switzerland.

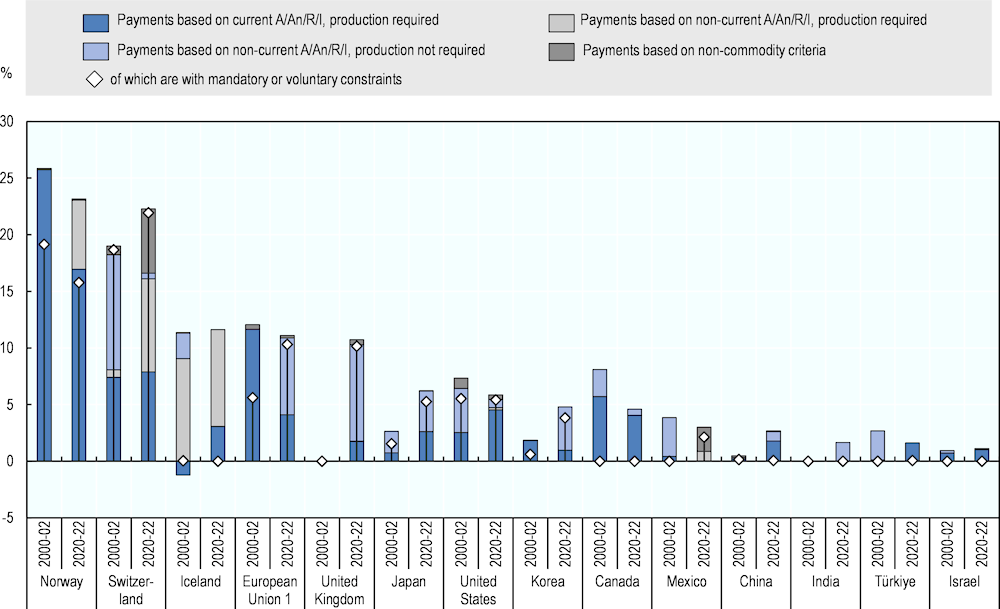

The majority of producer support still takes the form of the potentially most distorting measures

Different types of support have different impacts on producer behaviour. Producers respond to the incentives provided by support policies and adjust their production decisions accordingly. This changes the overall level of agricultural production, the mix of agricultural products produced, farm incomes and social and environmental outcomes.

In 2020-22, USD 411 billion, or two-thirds of the USD 630 billion in positive support to producers across the 54 countries covered in this report, was in forms considered to be the potentially most distorting to production and trade (9% of gross farm receipts). Across the OECD, such support amounted to USD 103 billion, while for the 11 emerging economies such transfers to producers totalled to USD 308 billion per year. Negative MPS policies additionally gave rise to USD 179 billion in implicit taxation in 2020-22 and these also have a distorting effect. The OECD has consistently recommended the phase out of potentially most distorting policies. More recent OECD work has shown that these measures also have a particularly high potential to harm the environment (Henderson and Lankoski, 2019[15]).8

Based on past and ongoing OECD work, the types of support considered to have the potential to be the most distorting are market price support, payments based on output, and payments based on the unconstrained use of variable inputs. These forms of support are also known for being both inefficient and untargeted to providing support to those households in need as a large share of the transfers are leaked in the form of higher prices for and larger use of inputs, or capitalised into land values. On average, these forms of support are much more prevalent in emerging economies than in OECD nations. In the 11 emerging economies, potentially most distorting policies generated positive support to producers equalling 10% of gross farm receipts and implicit taxation equal to 6% of gross farm receipts in 2020-22. In OECD countries, potentially most distorting policies generated positive support equalling 7% of gross farm receipts in 2020-22, but did not implicitly tax producers (Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11. Potentially most distorting transfers and other support by country, 2020-22

Notes: Countries are ranked according to the %PSE levels.

1. Support based on output payments and on the unconstrained use of variable inputs.

2. EU27 and the United Kingdom for 2020, and EU27 from 2021.

3. The OECD total does not include the non-OECD EU Member States.

4. The 11 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, the Philippines, Russian Federation, South Africa, Ukraine and Viet Nam.

5. The All countries total includes all OECD countries, non-OECD EU Member States, and the emerging economies.