Russia’s war against Ukraine has sparked a series of economic shocks around the global economy, and Eastern Partner (EaP) countries, as a result of their geographic and economic proximity to both Russia and Ukraine, are strongly affected. This chapter looks at the impact of the war on the overall macroeconomic performance in the EaP region, supply chain disruptions, commodity prices and exchange-rate volatility.

Assessing the Impact of Russia’s War against Ukraine on Eastern Partner Countries

2. Economic shocks triggered by the war

Abstract

The impact of sanctions and the contraction of Russia’s economy

While Russia is not experiencing destruction of its productive assets as a direct consequence of the war, international sanctions are affecting its ability to trade with the rest of the world and in particular to obtain critical technologies and capital goods. They are also isolating it from the global financial system. Industries such as automotive, which are heavily reliant on global value chains and foreign investment, are particularly vulnerable (Bloomberg, 2022[18]).

Since the war started, Russia’s economy appears to have contracted less than initially projected. Crude oil and gas exports propped up by high global prices and a compression of imports (down 40% in the first half) sustained a widening trade surplus, while domestic demand showed some resilience thanks to the Central Bank of Russia’s containment of the effects of sanctions on the financial sector and a milder-than-anticipated weakening of the labour market (IMF, 2022[19]). A range of command-and-control measures allowed the CBR to stabilise the ruble after its large depreciation in March. These have become less necessary over time as a result of very high export prices and restricted access to imports, which has restricted demand for dollars and euros.

In spite of these developments, Russia’s economy remains severely affected by the war, with GDP expected to contract by 3.9 percent in 2022, effectively bringing the country into a deep recession (OECD, 2022[20]).Over the medium term, moreover, and as long as sanctions remain in place, Russia’s economy will be set on a low-growth trend, as productivity is compromised by lack of access to key technological goods, new investment remains constrained by falling revenues, and a narrowing trade surplus is likely from 2023 onwards due to the EU’s embargo on Russian oil and reduced gas imports, as well as a likely decline of global energy prices. The state of Russia’s public finances is also likely to further deteriorate, as a consequence of a contracting economic base, shrinking export-duty collection on hydrocarbons exports, and the expenditures needed to prolong the war (World Bank, 2022[21]).

The devastation of Ukraine

Since the beginning of the war, the attacks on Ukraine have been unrelenting. With hospitals, train stations, ports, fields and countless buildings attacked and destroyed, the impact on Ukraine’s productive capacity will be long-lasting. As of 5 September, direct damage to physical infrastructure, housing and non-residential buildings was estimated at around USD 115 billion (KSE, 2022[22]), to which must be added the cost of lost trade and economic exchanges forgone, to say nothing of the human losses. The government itself estimated reconstruction and recovery needs, as of June 1, at about USD 349 billion, more than 1.6 times the GDP of Ukraine in 2021. Current estimates suggest it will take at least a decade for the Ukrainian economy to recover to pre-war levels (Economist Intelligence Unit, 2022[23]). Manufacturing in the East has completely stopped or been drastically reduced, and agricultural production has been severely compromised due to destruction of farmland, limited availability of fertiliser and reallocation of labour from agriculture to the war effort.

By mid-October, 7.6 million individual refugees had been recorded across Europe and another estimated 7 million people were internally displaced within Ukraine (UNHCR, 2022[24]) (IOM, 2022[25]). The economic impact on Ukraine is enormous, and will cause the largest contraction in the country’s recent history, with estimates of a drop in GDP in 2022 in the range of 30-45%, a contraction in exports by 60%, and poverty levels1 rising from around 5% to over 25% of total population in 2022 (EBRD, 2022[26]) (IMF, 2022[27]) (World Bank, 2022[28]). While some signs of resilience and adaption can be detected, such as a growing share of companies resuming operations in the summer months (EBA, 2022[29]), increasing IT services exports (IT Ukraine Association, 2022[30]), and agricultural products finding alternative export routes through the European Commission’s “solidarity lanes” initiative (European Commission, 2022[31]), the outlook for Ukraine remains highly uncertain. On the one hand, reconstruction activities may start as soon as the war ends boosting aggregate demand, but, on the other hand, forecasts for Ukraine’s economy remain prone to downside risks related to a deterioration of the war and potential energy shortages during the winter.

Large economic downturns in Russia and Ukraine will have profound, long-term repercussions for the other EaP economies, since both countries are key trading partners and important sources of investment, remittances and tourists for the EaP region.

The impact of the war on the other EaP countries

Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine threatens EaP countries’ recovery from COVID-19, lockdown measures and weak global growth. All EaP economies shrank substantially in 2020 in the wake of the pandemic, with GDP contractions ranging from 3.8% in Ukraine to 8.3% in Moldova. Following the rebound in 2021 across the region, recovery in 2022 was expected to continue at a steady pace on the back of growth in private consumption, investment and exports.

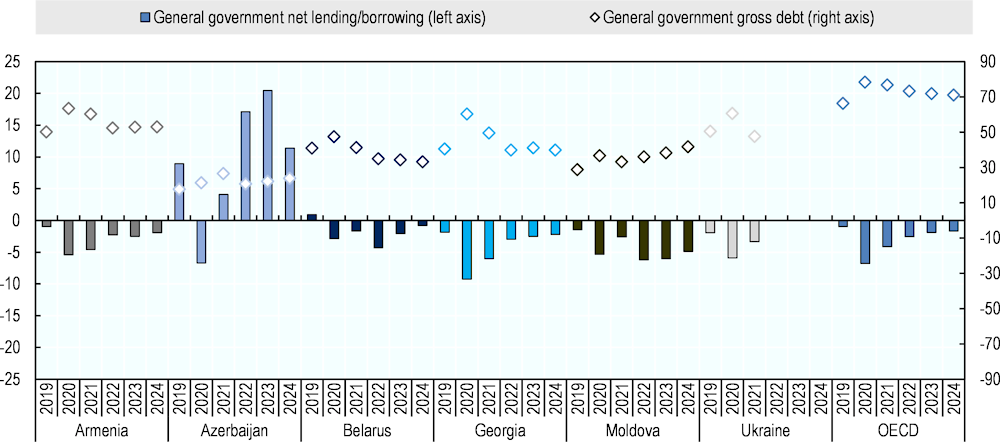

However, the war forced international organisations to considerably revise their growth projections (Figure 2.1). Ukraine’s economy is expected to contract by over 30% in 2022 and Belarus’s by over 6%. Moldova’s economy is also anticipated to contract this year, in contrast to its pre-war growth forecast.

Figure 2.1. GDP growth in EaP countries, 2019-2022

Note: actual values until 2021 (IMF), forecast values for 2022 (average of EBRD, IMF, and WB forecast)

For Armenia and Georgia, the initial downward revisions that followed the outbreak of the war should be reconsidered in light of the positive macroeconomic development observed in the first nine months of the year. Higher-than-expected private consumption and tourism revenues, driven by a significant number of Russians relocating to the two countries, have supported aggregate demand and overall economic activity. While distributional effects should also be taken into account, for instance the rising cost of housing, food and energy, the initially negative outlook for 2022 has turned positive for Armenia and Georgia, as evidenced by rapid growth in the first half of the year which resulted in updated GDP forecasts for 2022 of 7.3% and 8.6%, respectively. It should be noted, however, that these positive short-term effects may fade away beyond 2022, leaving the two countries exposed to the long-term consequences of the war described in the remainder of this paper.

Azerbaijan’s growth forecasts have been revised upward since the beginning of the war, with an initial GDP outlook strengthening by 0.8 percentage and already exceeding these expectations in the first half of the year. The war has caused commodity prices to soar, including oil and gas prices, thus bolstering the energy industry in Azerbaijan. This is forecast to sustain Azerbaijan’s growth such that the other downside risks from the war are overwhelmed by the additional revenues from oil and gas. Moreover, in the medium term Azerbaijan is well placed to capitalise on the EU’s intention to reduce energy-dependence on Russia with investment in the expansion of the Southern Gas Corridor, opening the possibility of significant gas exports to Southern Europe (Ibadoghlu, 2022[32]).

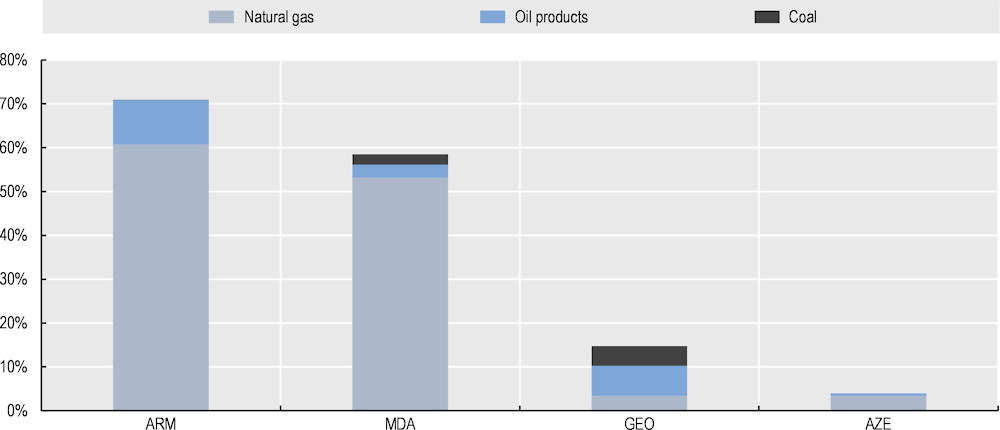

Figure 2.2. Fiscal dynamics in EaP countries

Ahead of the war, as countries started to slowly and steadily recover from COVID-19, governments were expected to withdraw pandemic-related support measures gradually and move towards fiscal consolidation. However, additional fiscal support might now be needed to protect the most vulnerable from the effects of the war. Even though available fiscal space varies considerably among them, fiscal positions have so far proved to be favorable and resilient in most EaP countries. In Armenia and Azerbaijan, during the first half of 2022, fiscal balances were in surplus, while in Georgia the fiscal deficit shrunk, overperforming the fiscal consolidation path planned for the year. In Moldova, the fiscal position proved to be resilient, with a deficit smaller than expected thanks to an increase in revenues that exceeded the increase in spending. Unsurprisingly, Ukraine was a major exception here, despite efforts to limit expenditures to critical public services and notwithstanding the agreement with external creditors for a two-year deferral in debt payments, total expenditures have been growing sharply and fiscal are expected to grow. Ukraine’s budget is heavily reliant on donor support (World Bank, 2022[34]).

While the scope for additional fiscal support may have increased for 2022 to cushion the immediate effects of the commodity and food price shocks on households and companies, downside risks remain. Negative threats include a protracted war, a slowdown in main trading partners, and monetary tightening in advanced economies. Downside risks are amplified in Moldova, due to its geographical proximity to the war (World Bank, 2022[34]; OECD, 2022[20]).

Supply chain disruptions

Global supply chains were already stressed by the COVID-19 pandemic, causing inflationary pressure, supply shortages and manufacturing delays across the world. The war made things worse, with the closure of airspaces, international sanctions and intense conflict in the Black Sea further disrupting the international flow of goods. The implications of these developments are best understood by looking at the position that Russia, Ukraine and Belarus have in global value chains.

Global trading routes

Global trade routes connecting markets, especially Europe and East Asia, have come under strain as a result of the war. In all major forms of transport (air, shipping and land-based), prices have increased, delivery times extended, and bottlenecks worsened.

Russia and Europe’s reciprocal air-space bans have made air transport much more costly. Firstly, routes between Europe and East Asia are now diverted to avoid Russian air space, making air transport both slower and more expensive. Moreover, a significant share of global air cargo volume is in Russian air cargo planes, which can no longer fly to Europe. The result is a sharp fall in capacity for air cargo transport as well as more expensive routes between Europe and East Asia (IATA, 2022[35]).

Moreover, border uncertainty and sanctions are reducing the ease of land transport through Russia. Rail and trucking through Russia is the main land corridor for trade between East Asia and Europe – known as the “northern corridor” – and a key transport route for global supply chains. Border controls have become more stringent as export bans from both the EU and Russia demand increased attention on cross-border rail freight. Moreover, many large transport companies have ceased operations involving Russia out of solidarity with Ukraine, including Maersk and HHLA, and even manufacturing companies such as Zyxel Communications Corp have stopped transit through Russia (van Leijen, 2022[36]). This is increasing pressure on alternative routes with limited overland capacity between East Asia and Europe, such as the trans-Caspian “middle corridor” (Box 5.1), causing supply shortages and delays.

Global shipping routes have not been as dramatically affected. The main impacts of the war have been a surge in demand for available shipping services as a result of the disruption to other modes of transport and an increased risk of shipping through the Black Sea, which results in higher prices for insuring cargo. There are reports of underwriters charging as much as 10% of the ship’s asset value as an additional “war-risk” premium (Koh and Nightingale, 2022[37]). Moreover, the ports of Ukraine have been damaged by Russian attacks and under blockade for months, severely limiting Ukraine’s export capacity. In an effort to stabilise spiralling world food prices, a UN-brokered deal has been signed on 27 July allowing for significant volumes of commercial food exports from three key Ukrainian ports in the Black Sea (Odesa, Chornomorsk, and Yuzhny) to be resumed (United Nations, 2022[38]). The agreement brought important results, with up to 11 new vessels a day being cleared for shipment and contributing to the observed drop in global wheat prices in August. Developments in early October, however, remind us of the fragility of this agreement, since longer inspection times create a backlog of vessels waiting for clearance, and the risk of deterioration of the war may jeopardize the stability of the deal2, with sudden repercussions on the global supply and prices of key food commodities (Financial Times, 2022[39]).

Russia, Ukraine and Belarus in global supply chains

Russia is a key ‘upstream’ producer for a number of global value chains, exporting many inputs for manufacturing processes. As such, it has one of the highest degrees of “forward participation” in global value chains in the world, with 55% of its exported value added being used as intermediate inputs embedded in partner countries’ exports (see Box 3.2).

A considerable share of this is energy exports, but Russia also exports important metals used in manufacturing. For example, Russia was the largest exporter of palladium in 2020, which is used for catalytic converters, as well as in semiconductors. With key industrial inputs now unable to leave Russia easily, firms are experiencing supply chain disruptions, higher prices and challenges to meet demand.

Ukraine and Belarus also play important, albeit lesser, roles in global supply chains, in particular with respect to agricultural production. After Canada and Russia, Belarus is the third largest exporter of potash (15.6% of the world’s internationally traded supply), a critical component for the production of potassium-based fertilisers to support plant growth, increase crop yields and improve disease resistance. The EU’s ban on Belarusian potash has resulted in supply chain disruptions in the food and agricultural sectors, adding to the upward pressure on food prices (FAO, 2022[40]) (UN Comtrade[41]).

Soaring commodity prices

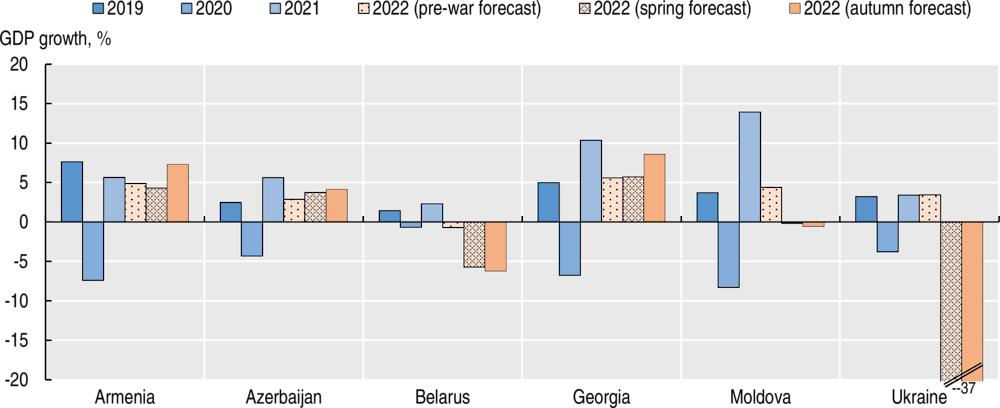

As a result of the war, sanctions and disrupted supply chains, market prices for key agricultural goods, energy and metals have been soaring. Figure 2.3 shows how selected commodities have increased in price since the beginning of the invasion. In 2020, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine together provided 24% of global exports of wheat, 17% of fertiliser, 24% of palladium and 11% of nickel. The market disruptions provoked by the war caused an immediate drop in short-term supply and high uncertainty over future availability of these key commodities (UN Comtrade[41]), which has caused prices to increase by over 50% for some of them, as well as delays in industries reliant on these commodities, such as car production. The price spikes pose significant inflationary risks and a particularly acute threat to low-income households, which spend a higher share of their income on energy and food.

Figure 2.3. Commodity price increases

Note: Fertiliser price refers to the Di-ammonium Phosphate (DAP) price, avg. Mar-Aug 2022

Source: (OECD, 2022[42]); (World Bank, 2022[43])

Energy

Globally, energy prices have increased sharply. Inflation was surging in many places even prior to the war following the re-opening of economies in mid-2020 (driven by both demand- and supply-side factors) (OECD, 2022[20]). The war reinforced price pressures: oil prices hit peaks of over USD 130 per barrel (for Brent crude) in the first weeks of the invasion, only dropping below USD 100 in early August. The persistency of this price hike is further shown by the fact that even fears of a global growth slowdown as a result of inflation, as well as OPEC+’s announcement to increase oil production over summer, have not lowered oil prices significantly below USD 100 (Slav, 2022[44]) (OPEC, 2022[45]). The price of Urals, Russia’s flagship crude oil blend, plummeted compared to Brent in the days after the start of the war and consistently traded at a discount of around USD 35 per barrel, to compensate buyers for increased costs (e.g. shipping insurance, freight rates) and risks. This price gap, however, began to shrink in early August and was at around USD 18 per barrel in early October (Investing.com, 2022[46]), possibly due to alternative buyers for Russian oil and increased purchases ahead of the EU embargo on seaborne imports of Russian crude to be imposed at the end of the year (PIIE, 2022[47]).

Furthermore, natural gas prices on international markets have more than doubled from before the war until end of August and have remained at much higher levels compared to 2021 (Nasdaq[48]). European consumers are trying to shift away from heavy reliance on Russian gas, but supplies are more challenging to re-route, as the transport infrastructure (pipelines) from supplying countries and the storage facilities must be in place. This can, in part, be overcome through imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG), which can be shipped and regasified with dedicated infrastructure by importing countries. To this end, European countries have accelerated their moves to upgrade their terminals to process LNG, reportedly with plans to secure 19 floating storage and regasification units (liquefied natural gas tankers with heat exchangers that use seawater to turn the supercooled fuel back into gas) in the coming years (Financial Times, 2022[49]).

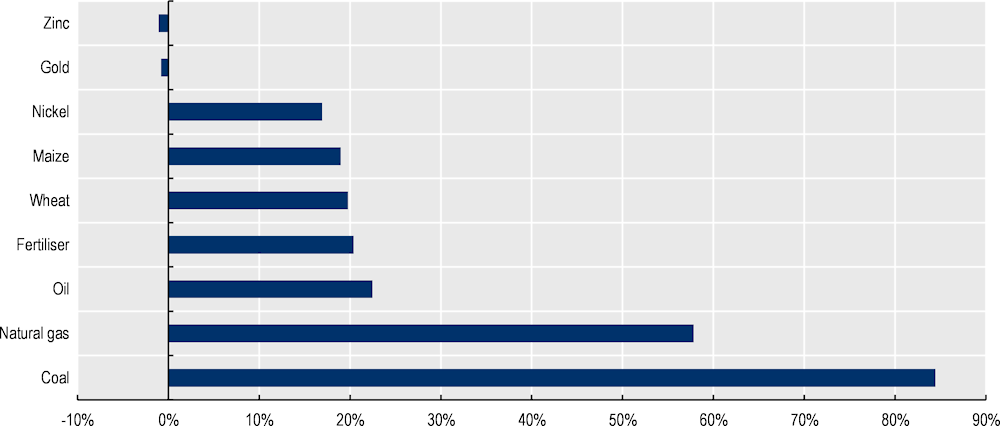

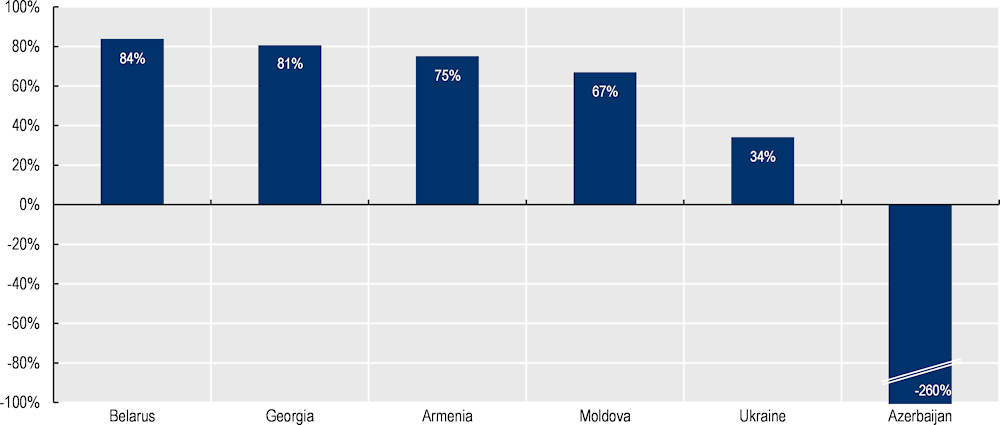

High energy prices will put strong inflationary pressure on the EaP region, especially for countries that are heavily reliant on external sources to meet their energy needs. As shown in Figure 2.4, with the exception of Azerbaijan, all EaP countries are significantly dependent on imports of energy, with their energy dependency rate ranging from 34% for Ukraine to 84% for Belarus. For all EaP countries, natural gas is the largest energy source – ranging from 28% of total energy supply in Ukraine, 47% in Georgia, 56% in Moldova, 63% in Belarus and 66% in Azerbaijan–, with some use of oil, coal, hydropower and thermal power. Armenia and Moldova import nearly all of their gas from Russia, which makes the two countries highly dependent on Russia for their energy supply (Figure 2.5), while Georgia imports the majority from Azerbaijan.

Figure 2.4. Energy dependency rate

Note: Data from 2020 except Armenia (2019)

Source: IEA (energy balance sheets); UNComtrade; Georgian National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission

Figure 2.5. Fossil fuel imports from Russia as share of Total Energy Supply (TES)

While Armenia has a long-term contract with Russia for the supply of gas which shields it from excessive price increases, in recent years Moldova is strengthening its energy security by making alternative supplies of natural gas possible through the Iasi-Ungheni-Chisinau pipeline (Box 2.1), reverse flows from the Trans-Balkan system, and the possibility to buy gas from EU markets and store it in Ukrainian underground gas storage facilities (IEA, 2022[51]).

In addition, there have been recent efforts from the EU to help Moldova and Ukraine transition away from Russian energy and strengthen their energy security. For example, both countries’ electricity grid systems have been synchronised with the EU power grid, allowing them to use EU sources for electricity supply (European Commission, 2022[52]). Moreover, EU members agreed to set up a platform for common purchases of gas, LNG and hydrogen, which will also be open to Moldova, Ukraine and Georgia allowing these countries to benefit from cheaper energy prices (European Commission, 2022[53]).

EaP countries have also an opportunity to scale up renewable energy generation capacity to reduce fossil fuel dependency and advance their green transition. The rise in prices and price uncertainty for energy create major implications for countries’ energy and climate policy, especially for those heavily dependent on energy imports (Box 2.1). The domestic use of fossil fuels is disincentivised by the expectation or risk of higher prices, which can push countries towards saving fossil fuels and investing in energy efficiency and/or increasing the share of renewables in their energy mix (OECD, 2022[50]). Increasing FDI in renewable energy could help advance this transition, particularly in Georgia and Ukraine which are already attracting significant greenfield investments in renewable energy.

Box 2.1. EaP countries’ climate and energy policies

Armenia’s short-, mid- and long-term climate policy will depend heavily on energy security, and its relations with Russia and regional neighbours. In late March, the government approved the energy efficiency and renewable energy programme for 2022-2030, which highlights energy security as a key driver for change, including setting a target of 15% solar of energy generation by 2030. This corresponds to 1000 MW of solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity and 300 MW of battery storage to be built. Initial plans exist for the first stage of implementation, which would see the tendering of five 120 MW solar PV projects. In mid-April a programme was also approved to support energy efficient renovations of apartments and residential buildings.

In Moldova, the main objectives of the Energy Strategy until 2030 include improving energy security, developing competitive energy markets, European integration, and climate change mitigation. According to upcoming renewable tenders from the government and the regulator, the capacity of wind, solar, biogas and hydropower plants is to be increased by 521 MW. In the gas sector, Moldova is striving to reduce its dependence on Russian gas, for instance through the extension of the Iasi-Ungheni gas pipeline to Chisinau, allowing Moldova’s capital to receive gas from Romania, which in the medium term should replace Russia as its main source of natural gas. Due to high energy intensity in the country, increasing energy efficiency is another important pillar to enhance its energy security.

In Georgia, natural gas prices are mainly dependent on undisclosed long-term contracts with Azerbaijan. Thus, Georgia is expected not to be immediately affected by increased global natural gas prices. The cost of diesel fuel, which makes up a significant share of household expenditure, was up 45% y-o-y in August 2022. The government has announced its intention to build new large hydropower plants including in Khudoni, Nenskra, and Namakhvani, although the latter project has recently been abandoned in the wake of prolonged protests against its construction. New proposals for support schemes and revenue sharing arrangements between central and local authorities are currently being developed to attract private investors and mitigate local resistance. Overall, the short-term effects of the war are moderately increasing incentives to reduce consumption of road fuels and pursue additional investments in domestic renewable electricity generation capacities, which could positively impact emissions and climate policy.

For Azerbaijan, higher oil and gas prices will increase net income in the country. Government revenues for 2022 alone have been revised upward, affording Azerbaijan an expected budget surplus of 20% of GDP in 2022 (12% in 2023). As the EU looks to increase capacity in the Southern Gas Corridor, Azerbaijan’s efforts to increase gas exports to Europe are bolstered by the crisis. In mid-July, the European Commission agreed with Azerbaijan to double its imports of natural gas to at least 20 billion cubic metres a year by 2027, having already increased imports from 8.1 in 2021 to 12 bcm in 2022 (European Commission, 2022[54]).

Source: (OECD, 2022[50])

Food

Food price increases can have disastrous effects on food security, poverty and global hunger. In the EaP region, as in the rest of the world, food prices are rising sharply as a result of the war. Known as the “breadbasket of Europe”, the region encompassing Ukraine and Southern Russia was responsible for 26% of global exports of wheat in 2020 (UN Comtrade[41]). War in this region caused prices of key grains to increase dramatically since the start of the war – wheat by as much as 90% and maize by over 20% in May 2022 (Markets Insider, 2022[55]). Much of this rise was driven by market panic about grain availability more than actual lack of grain (OECD, 2022[56]), as well as the blockade of Ukrainian seaports for export by Russia. These concerns were exacerbated by Russia’s announcement of a temporary halt to all exports of grain to the Eurasian Economic Union, of which Armenia is a member, until August 2022. The Black Sea Grain Initiative, a recent deal between Russia, Ukraine and Türkiye allowing for the export of large volumes of commercial food cargo from the Ukrainian ports of Odessa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny, has significantly reduced pressure on grain supply and resulted in wheat prices returning to pre-war levels (United Nations, 2022[38]). More generally, global food prices had almost returned to pre-crisis levels by October 2022 (OECD, 2022[20]), a phenomenon explained in part by lower demand (e.g., for cereals, dairy and meat) and improved production prospects in the case of sugar (FAO, 2022[57]),

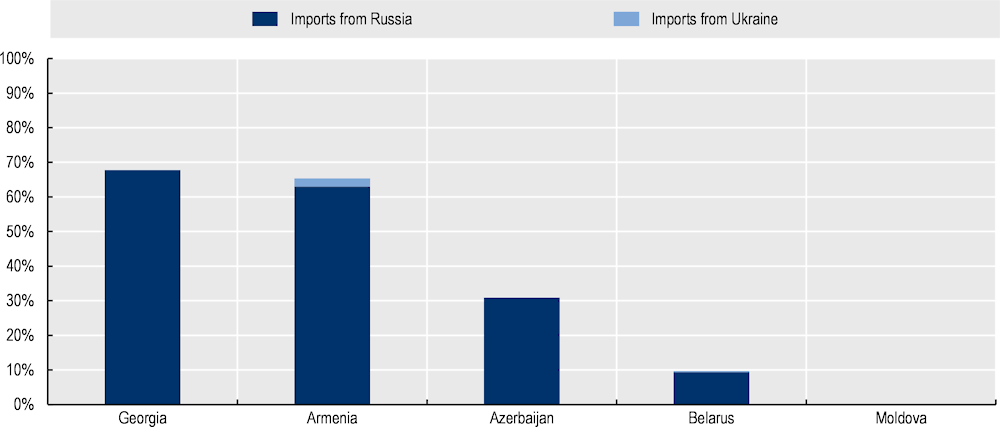

Beyond price increases, supply uncertainties from Russia also pose a food security risk in EaP countries. As shown in Figure 2.6, all EaP countries except Moldova are heavily dependent on wheat imports from Russia, with Georgia and Armenia exposed for more than half of their total domestic consumption. Such reliance on Russia poses a risk since the country has previously used export controls of key commodities as political tools to put pressure on trading partners. Russia has also shown concerns about internal food security that has led to protectionist policies and, as the war continues, it may wish to further limit exports of wheat thus increasing risks of food security for EaP countries.

Figure 2.6. Dependence on wheat imports from Russia and Ukraine

Note: data for Armenia covers only 2019 and 2020

Source: National Statistical Offices of EaP countries and FAO (food balance sheets)

Moldova is effectively self-sufficient in wheat, as it shares the same fertile geographic conditions as Ukraine. None of the EaP countries have a significant level of wheat imports from Ukraine, but the destruction of Ukrainian agricultural capacity and exports is a major factor in the increase in global prices, which still poses risks of food security for low-income households everywhere.

The risk of long-term supply shortages has prompted discussion of increasing domestic agricultural production in EaP countries. For example, in Armenia 50% of arable land is uncultivated which, given the greater incentives of farming in this high-price environment, could be used for wheat production (JAM News, 2022[58]). However, these efforts will take time and do not address the short-term pain-points of the high food prices and risk of shortages. Given their reliance on food imports, some EaP countries are introducing a variety of measures to secure supply of basic food items. For example, in an effort to simplify procedures for replacing products previously imported from Russia and Ukraine, the government of Moldova introduced a time-bound exemption from the certification procedure for food and staple products imported from the EU (bne IntelliNews, 2022[59]). Azerbaijan, on the other hand, is diversifying its sources of food imports, and as a result the share of cereals imported from Kazakhstan has increased tenfold in the first six months of 2022 compared to the previous year (Trend news agency, 2022[60]).

Exchange-rate movements

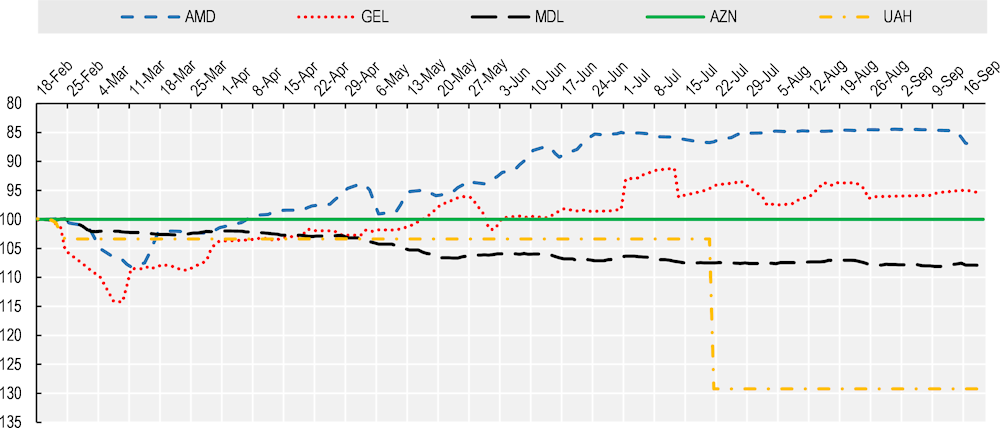

Since the beginning of the war, exchange rates of EaP currencies against both the dollar and the ruble have been highly volatile. As can be seen in Figure 2.7, markets’ initial response to the war was an intense weakening of EaP currencies against the dollar, following the collapse of the Russian ruble during this period. However, since then, not only has the ruble significantly recovered as a result of strong forex and capital controls and high energy prices, but many EaP currencies have also re-appreciated, with the Armenian dram and the Georgian lari even exceeding their pre-war levels. In the weeks after the beginning of the war the dram and the lari lost up to 8% and 14% of their value against the dollar, respectively, but as of mid-June the dram was up 12%, and the lari by 1.5% (after peaking at +3.8%). Moldova’s currency has not experienced a similar trend reversal, reflecting the country’s weak economic performance and outlook. In July, the National Bank of Ukraine devalued the hryvnia by 25% against the USD, with the objective of supporting the competitiveness of Ukrainian producers and maintaining control over inflation dynamics (Reuters, 2022[61]).

Figure 2.7. Exchange rates dynamics

Note: AMD = Armenian Dram, GEL = Georgian Lari, MDL = Moldovan Lei, AZN = Azerbaijani Manat, UAH = Ukrainian Hryvnia. Values below/above 100 correspond to an appreciation/depreciation against the USD.

Source: OECD calculations based on data from Central Banks of EaP countries

Several factors have contributed to the observed exchange-rate dynamics across EaP countries. On the one hand, the broad and steady pace of monetary tightening via interest rate hikes introduced by national banks across the region in response to accelerating inflation has increased the attractiveness of national currencies, pushing up their value. On the other hand, short-term changes in aggregate demand (both domestic and external) may have further increased demand for national currencies.

In Armenia and Georgia, the influx of Russian citizens (see below) is putting upward pressure on the dram and lari, respectively. Since the beginning of the war, Russians moving to the two countries are opening bank accounts3 and exchanging a significant amount of foreign currency for the local ones, thereby increasing their demand and contributing to their appreciation. In the case of Georgia, a growth in remittances and a rise in tourism and export revenues are also responsible for the strengthening of the national currency. For Armenia, the decision to start paying for natural gas imports from Russia in rubles instead of dollars may also have helped to push up the value of the dram, as the demand for dollars falls (Finport, 2022[62]).

While the initial shock contributed to the accelerating price increase observed in March and April by making imports more expensive, the upward trend that followed, especially in Armenia and Georgia, is seen by some exporters as potentially making their products less competitive on international markets. This appreciation, however, is not being treated as a concern by the Armenian Central Bank, as it helps counter the many inflationary pressures arising from the war (Armenews, 2022[63]).

Nevertheless, the high volatility observed since the beginning of the war may reverse the recent upward trend and cause renewed depreciation of EaP currencies against the dollar, which would increase inflationary pressure by making imports more expensive. Imports are equivalent to between 36-66% of GDP across the region and thus an increase in the price of these goods will have a significant effect on the general price level and cost of living in the Eastern Partnership (World Bank[64]). An exception to this trend is Azerbaijan, which has a pegged exchange rate system with the US dollar and thus has not experienced any exchange rate volatility or ‘imported’ inflation.

Notes

← 1. Based on the global line for upper middle-income countries of US$6.85 a day (2017 PPP)

← 2. On 29 October, Russia announced its withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative, and then re-entered it on 2 November after the U.N. and Türkiye secured assurances from Ukraine that shipping corridors would not be used for military purposes. Yet, the announcement caused a spike in global wheat prices and raised new concerns over international food shortages. (NPR, 2022[196])

← 3. An estimated 27 000 foreigners, mostly Russians, have opened bank accounts in Armenia from 24 February to 22 March 2022 (RFERL, 2022[181])